- 1California Sea Grant, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 2Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

- 3Environmental Resources Division, Sonoma County Water Agency, Santa Rosa, CA, United States

In California’s Russian River watershed, home to imperiled salmon and steelhead populations, an intensive long-term monitoring program plays an integral role in supporting species recovery. The program conducts life cycle and basinwide monitoring of natural- and hatchery-origin coho salmon using PIT antenna arrays, downstream migrant traps, snorkel counts, electrofishing, and spawner surveys paired with environmental monitoring. The program has also served as a foundation for targeted research by providing baseline data and monitoring infrastructure. Long-term and consistent tracking of population metrics has indicated modest but meaningful positive trends in abundance, but has also revealed unanticipated bottlenecks to population recovery, many of which are related to low streamflow. Monitoring has also revealed complex movement patterns of juveniles and adults throughout the watershed that have broadened our understanding of salmon life history diversity and the importance of managing for diversity as a key strategy for recovering salmon. Minor adaptations to the monitoring program have enabled evaluation of specific recovery actions, including genetic intervention, flow augmentation from off-channel storage, fish passage remediation, and physical habitat restoration projects. Critical to the effectiveness of the Russian River’s monitoring program has been the ability to manage and share data through a centralized database. This has facilitated development of data dashboards that are used for management decision-making and long-term recovery planning and prioritization. We reflect on the evolution of the Russian River monitoring program, including benefits and challenges of long-term and spatially-distributed monitoring in a hatchery-supplemented population and lessons learned that have relevance for salmon recovery efforts across their range.

Introduction

Long-term ecological monitoring serves many roles that are critical for imperiled species’ recovery, including tracking status over time and identifying limiting factors (Maxwell and Jennings, 2005; Schmeller et al., 2017). It is often the only means of isolating trends or responses from background environmental noise and is essential for accurate predictive modeling. Furthermore, it creates a foundation for addressing research questions and evaluating the impact of management interventions, including those that may not be anticipated at the time monitoring is initiated. It can also serve as a nexus for collaboration, education, and training. Given the extent of environmental degradation and global biodiversity declines, the need for effective and stable monitoring programs has never been greater (Radinger et al., 2019).

Monitoring is particularly important for the management and recovery of anadromous salmon, an ecologically, culturally, and economically important fish that has undergone severe declines (Nehlsen et al., 1991; Gustafson et al., 2007). With a life cycle characterized by complex life history strategies that span freshwater, estuarine, and marine environments, salmon can have highly variable population dynamics that are difficult to estimate and interpret, especially for at-risk populations with low abundance. Long-term and widespread monitoring at multiple scales is therefore essential for distilling meaningful patterns from noise and evaluating whether management interventions are supporting population recovery goals (Fausch et al., 2002).

While the value of long-term monitoring in salmonid recovery is well-recognized (Tarzwell, 1937; Reeves et al., 1991; Roni et al., 2002; Lovett et al., 2007), most monitoring programs struggle to maintain consistency over prolonged periods for many reasons, including funding instability, inadequate coordination, and lack of standardized methodologies and database centralization (Bennett et al., 2016; Bilby et al., 2024). Such programs are expensive to sustain and, because their benefits may not be immediately apparent, their value can be difficult to communicate to funders and the general public. Coordinated, long-term monitoring also brings with it unique and complex data management challenges, which require expertise and resources that can be difficult to secure and sustain.

Nevertheless, a growing appreciation for long-term monitoring has led to programs such as the Intensively Monitored Watershed (IMW) effort (Bennett et al., 2016; Bisson et al., 2024) which have demonstrated their value in assessing population status and trends and evaluating the effectiveness of recovery actions. Here we present a case study describing the evolution of an integrated, long-term salmon monitoring program in California’s Russian River watershed. Although not strictly an IMW, the program has documented modest but meaningful growth in coho salmon abundance, revealed unanticipated bottlenecks to population recovery, broadened our understanding of the importance of salmon life history diversity in coho salmon recovery, and spurred development of standardized methods and a centralized database that has been essential to informing management actions and communicating findings to stakeholders and the general public. We describe how lessons learned, including challenges of sustaining this more than 20-year effort, hold broad relevance for salmon recovery efforts and monitoring programs in other watersheds.

Background

Russian River watershed

The Russian River in Northern California drains approximately 3,800 km2 and flows 177 km from its headwaters to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean (Figure 1) and there are over 200 tributaries that provide habitat for a diverse community of fish species. The watershed has a rainfall-dominated hydrologic regime with nearly all of the precipitation falling between November and April. The lower mainstem has an annual flood recurrence interval of approximately 680 m3s-1 during the winter that slowly recedes in spring, reaching a low or intermittent state during the summer dry season (July–October). A long, narrow, bar-built estuary extends from the mouth of the Russian River upstream approximately 11.5 km and is intermittently closed during the summer dry season. Land use in the watershed consists primarily of urban, rural residential, and agricultural uses, with wine grapes being the predominant agricultural product. Approximately 93% of streamside property is privately owned and urban development has resulted in the loss of the majority of historical wetland and off-channel area. In some subwatersheds more than 90% of the forested land area has been cut for timber and grazing (SEC, 1996).

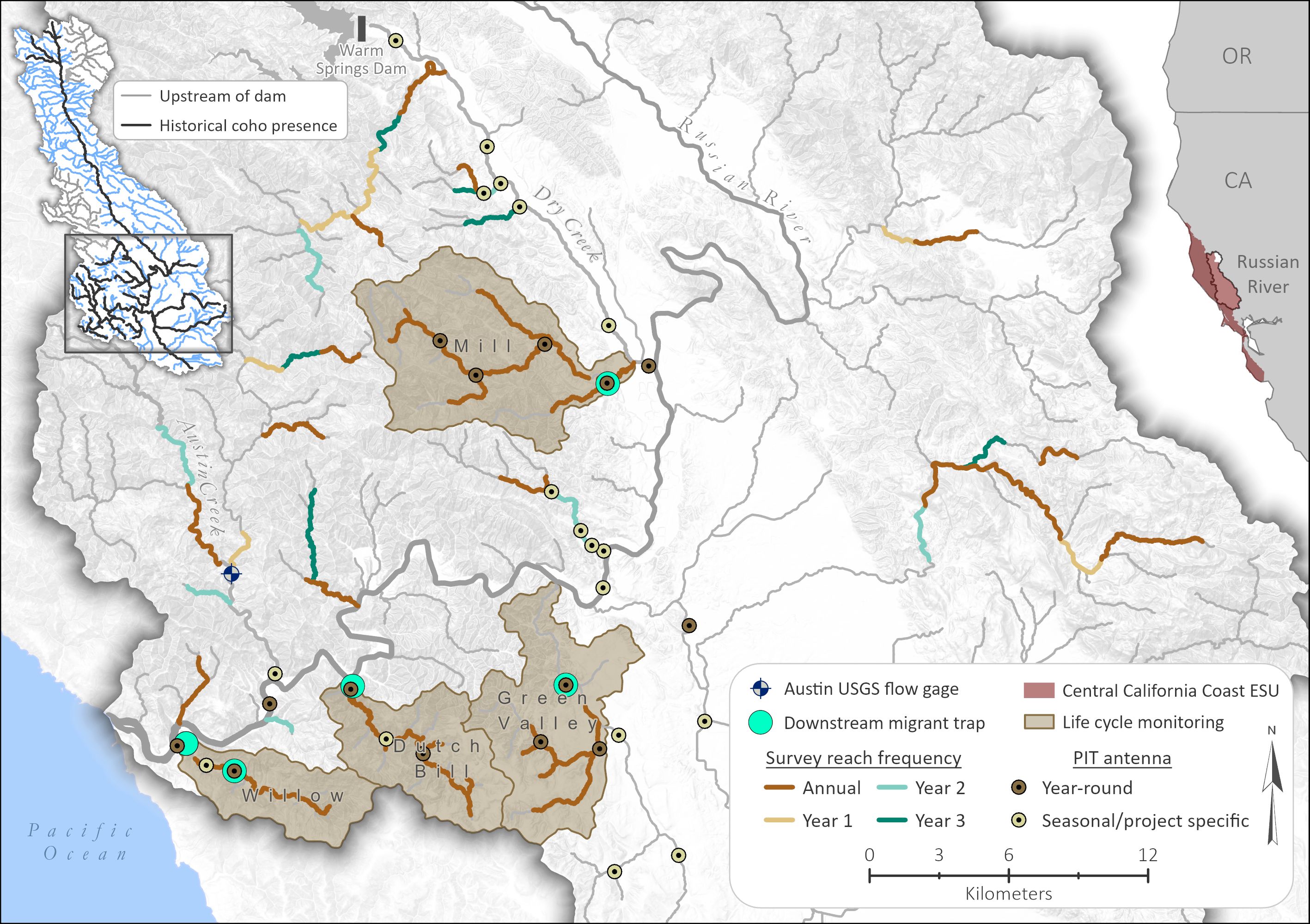

Figure 1. Fish monitoring sites (PIT antennas and downstream migrant traps) and Generalized Random Tessellation Stratified (GRTS) survey reaches in the Russian River watershed (only adult coho salmon spawning reaches shown). Annual surveys are conducted in all coho salmon spawning habitat in the four life cycle monitoring subwatersheds and all other reaches are surveyed according to a rotating panel (annual in some reaches and every third year in other reaches). Reach color indicates redd survey frequency.

Estimates of historical salmonid abundance suggest that tens of thousands of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), and steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) inhabited the Russian River in the early to mid-20th century (NMFS, 2012). As in many watersheds along the Pacific Coast, salmonid populations in the Russian River declined dramatically following Westward expansion of European settlers and displacement of Indigenous peoples and stewardship systems. Along with overharvest, land and water use practices such as urban development, logging, agriculture, dam construction, gravel mining, and water extraction led to extensive loss of habitat and connectivity that have collectively contributed towards the decline of salmon populations (SEC, 1996). Two large dams were constructed in the mid- to late-1900s on the upper mainstem and a major tributary of the Russian River for the purpose of regulating river flows for flood control and water supply. These dams cut off access to approximately 272 km of salmonid habitat (SEC, 1996) and had the effect of altering the natural hydrologic regime, trapping sediment, and causing a multitude of geomorphological changes such as channel incision and disconnection from the historic floodplain (ISRP, 2016). Throughout the watershed, there are also 283 non-natural total or partial barriers and an additional 575 unconfirmed or unassessed potential barriers (CDFW, 2025) that reduce connectivity and limit access to habitat in headwater streams.

The Central California Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit of coho salmon was nearly extirpated from the Russian River watershed by the late 1900s, prompting state and federal listing as endangered in the early 2000s (CDFG, 2002; 70 FR 37160, 2005). Recognition of the precarious state of coho salmon populations led to recovery actions that included restoration of freshwater habitat in small- to mid-size tributaries (e.g., wood placement, grade control structures, road culvert replacement) beginning in the 1980s and 1990s. Despite these actions, fewer than 10 adult coho salmon were found to return to the Russian River each year by the early 2000s. To avoid complete extirpation, multiple agencies initiated the Russian River Coho Salmon Captive Broodstock Program that has the goal of reestablishing self-sustaining coho salmon runs by reintroducing hatchery-raised fish to historically occupied streams. Under this program, broodstock are collected from local streams, reared to maturity and spawned at Don Clausen Fish Hatchery at Warm Springs Dam (conservation hatchery). Progeny are then stocked into the Russian River watershed at multiple life stages. Releases of juvenile coho began in 2004 (see details in Box 1) and since then, fish have been stocked in over 25 streams. Subsequent salmonid recovery plans expanded recovery strategies to include increasing habitat connectivity and additional enhancement of freshwater and estuarine habitats (NMFS, 2012, 2016).

Russian River Salmon and Steelhead Monitoring Program

Comprehensive salmonid monitoring in the Russian River began with the first releases of juvenile coho salmon from the conservation hatchery in 2004, with an initial goal of evaluating the success of hatchery-reared fish post-release into the wild. A life cycle monitoring (LCM) approach was adopted, but because the Russian River was too large to implement standard fish monitoring techniques, we focused our monitoring on four priority release streams with subwatershed areas ranging from 22 to 59 km2 (Figure 1). These were selected because they were core streams for physical habitat restoration and hatchery supplementation (NMFS, 2012) and/or they supported the last reported observations of wild coho salmon prior to the initiation of the conservation hatchery program. In each of the LCM subwatersheds, we established counting stations (downstream migrant traps and PIT antenna arrays, Figure 1) to track lifestage-specific abundance, growth, movement, and survival. We also initiated census redd surveys and juvenile snorkel counts to track spatial distribution and natural production. Life cycle monitoring was used to compare the success of different hatchery release strategies (e.g., release lifestage, timing, location) and to evaluate a programmatic decision to outbreed Russian River broodstock with wild fish from a neighboring watershed when the risk of inbreeding depression was deemed too high (Pregler et al., 2023). The conservation hatchery has been critical to rebuilding the Russian River coho population, but it also creates some challenges in enumerating natural-origin production (Box 1).

Box 1. Monitoring considerations for imperiled populations with conservation hatchery supplementation.

Monitoring has been an integral component of the conservation hatchery program from its inception. Initially, the program had very basic questions, such as whether hatchery fish were surviving as juveniles in the streams, migrating out as smolts, and returning as adults. There were also specific questions about the relative success of different release strategies (e.g., life stages, streams, imprinting techniques, genetic crosses) and then ultimately whether the population was increasing over time throughout the watershed. Developing a marking strategy that distinguished natural- from hatchery-origin fish as well as the ability to compare release groups of interest was challenging. For the first decade of the program, all hatchery fish received both an adipose fin clip and a coded wire tag (CWT), which provided two marks for distinguishing fish origin. Adipose fin clips were particularly useful as a visual mark during snorkel counts and spawner surveys, but this mark was abandoned in 2013 to address accidental take of coho salmon in a recreational fishery for adipose-clipped steelhead. While CWTs were useful as a batch mark, they required capture and scanning of fish to identify CWT presence and did not allow us to differentiate multiple hatchery release groups. To distinguish fish released in different locations and at different lifestages, we experimented with visual implant elastomer tags in different body locations, but these marks faded within months and were extremely time-consuming to apply. Ultimately, we decided to invest in an individual marking strategy using PIT tags which allowed us the flexibility to track survival, abundance, growth, and movement of highly-specific groups of both natural- and hatchery-origin fish.

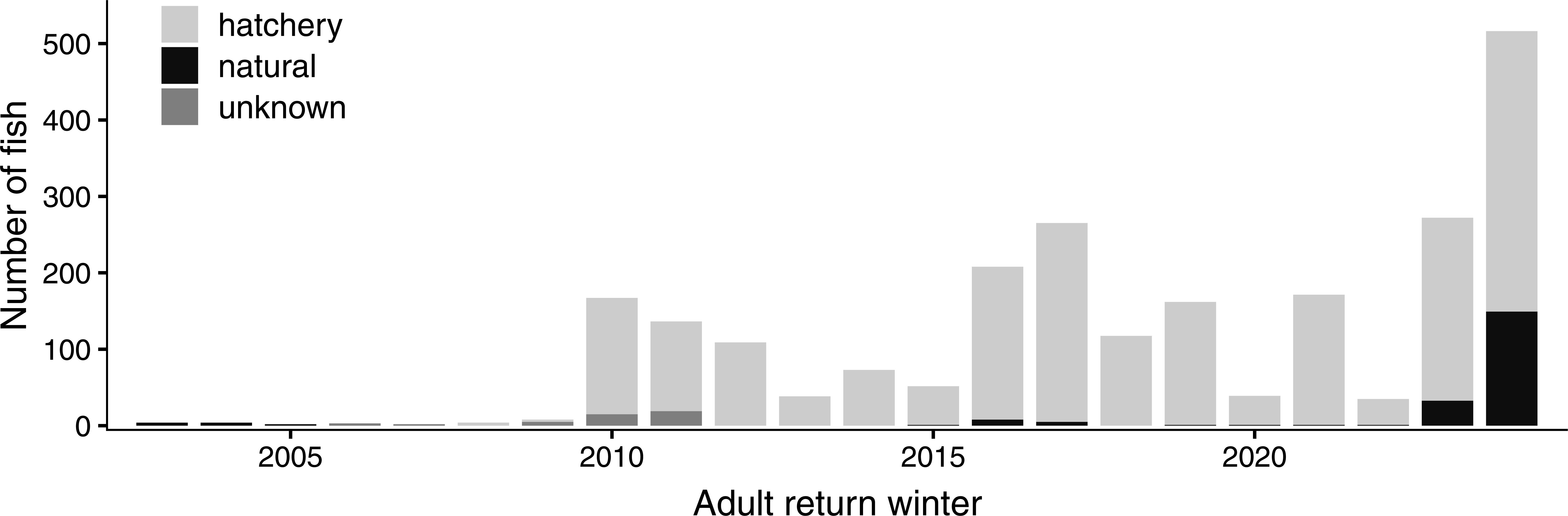

Despite the changes in marking and sampling strategies that occurred during the first decade of our monitoring program that made it more difficult to consistently track long-term trends, we have been able to document an overall increase in adult abundance in the four LCM subwatersheds, from fewer than five adult fish returning each year prior to winter 2010/11 to tens or hundreds of fish returning each winter over the last 15 years (Figure 2). However, the data also revealed that the population continued to rely almost entirely on hatchery releases. This, in turn, led to a series of focused studies to understand why natural-origin fish were only rarely able to complete their life cycle (e.g., see Lesson 1).

While hatchery fish complicate monitoring of wild fish, they also provide unique opportunities for controlled natural experiments that would be impossible to conduct on imperiled remnant populations. In the Russian River, hatchery coho salmon have served as a source of fish for tagging studies that have helped identify recovery bottlenecks and evaluate management interventions (e.g., Box 2). PIT tag studies using thousands of hatchery fish have helped to identify passage barriers and flow-related survival bottlenecks as well as evaluate responses to restoration projects. By stocking PIT-tagged fish from similar family groups into multiple tributaries and tracking their emigration timing, we have also been able to control for genetics and attribute diversity in movement patterns to environmental conditions (Kastl et al., 2022; Obedzinski et al. in review)1. Similarly, we are using acoustic-tagged hatchery fish to identify bottlenecks in survival as fish migrate through the mainstem Russian River to the ocean (Rossi et al., 2025). None of these studies would have been possible using natural-origin coho salmon which currently have low abundance and heightened protections as ESA-listed species.

While hatchery-origin fish have allowed for controlled studies with high sample sizes, we recognize they may not always be good surrogates for wild fish (Chen et al., 2025). It is important to consider potential differences when making inferences about the combined population. As the natural-origin population continues to grow in the Russian River (Figure 2), we will be able to conduct studies allowing us to not only evaluate and account for these differences but also explore relationships between natural-origin and hatchery-origin fish that may help advance recovery.

Figure 2. Estimated number of adult coho salmon returning annually to the four LCM subwatersheds, combined. Between winters 2003 and 2011, methodology for counting adults was inconsistent among years and annual returns were estimated in an ad hoc manner using data from spawner surveys, juvenile snorkel counts, and trapping efforts. Beginning in 2013, with the completion of year-round PIT antenna arrays and PIT tagging of both hatchery- and natural-origin fish in all four LCM streams, annual adult detections were expanded based on antenna efficiency and known tag ratios of juveniles. Adult return winter 2006 was the first winter in which age-3, adult coho salmon were expected to return as a result of hatchery releases.

Over the course of a decade, monitoring continued to focus on coho salmon but grew to include tracking the status and trends of all three salmonid species at a basinwide scale. Because basinwide census surveys were not feasible, we developed a sample frame comprised of 2–4 km survey reaches using a Generalized Random Tessellation Stratified (GRTS) sampling approach with a rotating panel design as outlined in the California Monitoring Plan (Adams et al., 2011). Each year, winter redd counts followed by summer juvenile snorkel counts are conducted in a sample of coho salmon reaches to estimate annual basinwide redd abundance and juvenile occupancy. Between 2007 and 2012, we also installed an extensive network of PIT antennas (Figure 1) to increase our understanding of how individuals and populations are using the Russian River watershed over the course of their life cycle. PIT detection systems are used to track the movements and fates of PIT-tagged hatchery fish (approximately 15–25% of fish released) as well as natural-origin fish that are captured and tagged at downstream migrant traps and during electrofishing surveys.

The combination of life cycle and basinwide monitoring in conjunction with the PIT antenna network and conservation hatchery program has served as a means of tracking long-term status and trends, but also serves as foundation for targeted research by providing baseline data, monitoring infrastructure, and a source of tagged fish that can be used to evaluate management interventions. Minor adaptations, such as strategic placement of new antenna arrays, additional PIT tagging of specific groups of fish, customized surveys, and environmental monitoring have enabled numerous research studies and supported modeling efforts and evaluation of specific recovery actions. Although the primary goal of the Russian River Salmon and Steelhead Monitoring Program (RRSSMP) was not specifically aimed at assessing the impacts of habitat restoration (i.e., not an IMW as defined by Bennett et al., 2016), it has permitted us to evaluate fish responses to habitat enhancement projects in some cases (e.g., Box 2, Figure 3). The program has now existed for over 20 years and, in addition to tracking long-term population trends, has led to several lessons learned about bottlenecks to salmon recovery, a broadened understanding of salmon life history diversity for coho salmon recovery, recognition of the importance of data management, and an enhanced ability to share data with partners to advance salmon recovery in the basin.

Box 2. Integrated monitoring informs habitat restoration in Mill Creek.

In depleted Pacific Coast salmon populations, lack of comprehensive monitoring has limited our ability to adequately evaluate recovery actions and make informed choices regarding how to allocate limited resources. Moreover, Bennett et al. (2016) highlight that few monitoring efforts focus on assessing responses to restoration at the population-level, suggesting a mismatch between overall management goals and the scale at which effectiveness monitoring data are collected (Radinger et al., 2019). Minor adjustments to the RRSSMP have enabled such evaluations and guided habitat restoration.

Mill Creek is a historical coho salmon tributary that was one of the original recipients of conservation hatchery supplementation and a focus stream for LCM. Like many Russian River tributaries, high quality fish habitat in the Mill subwatershed has been compromised by deforestation, sedimentation, and water extraction resulting from logging, road networks, rural residential development, and agriculture, as well as secondary effects from dam construction and gravel mining at downstream locations that has led to channel incision. In addition, remnant flashboard dam structures and other physical blockages (e.g., road crossings and culverts) have created partial fish passage barriers. Multiyear monitoring datasets collected by the RRSSMP in Mill Creek have helped reveal specific obstacles to coho salmon recovery and guide restoration and recovery efforts.

For example, at the time of initial coho salmon reintroduction into Mill Creek in 2004, resource managers were aware of an artificial partial barrier in the lower Mill Creek watershed (river km 5.48), but it was not thought to impede upstream migrating adult salmonids during winter flow conditions. However, RRSSMP spawner surveys in Mill Creek demonstrated that the barrier did restrict adult passage in most years, with the majority of redds consistently observed downstream of the structure (Figure 3). PIT antenna detection data confirmed the impact of the barrier. During the winter of 2010/11, nine PIT-tagged adult coho salmon that were detected entering Mill Creek, traveled upstream to an antenna site that was located downstream of the barrier and then quickly moved back out of Mill Creek and were later detected in a neighboring tributary. Summer snorkel counts showed high densities of juvenile coho salmon in the lowest reaches of Mill Creek and this was problematic because late-summer wet/dry mapping data indicated that more than half of the habitat downstream of the barrier was prone to stream drying (mean of 52% over 13 years compared to 22% above the barrier site). Fish inhabiting the lower reaches were frequently observed perishing in isolated pools during the summer and natural-origin juveniles were only rarely observed in the upper perennial reaches where oversummer survival was higher. This collective monitoring data was shared with restoration practitioners and resource managers who used the information to justify and fund remediation of the barrier. Remediation was completed in summer 2016, after which increased densities of redds and juveniles were observed in the upper perennial reaches of Mill Creek and its tributaries (Figure 3). This example highlights the importance of our monitoring for identifying a fish passage issue, providing justification for addressing it, and evaluating the effect of addressing it on coho salmon spawning distribution.

While the barrier removal project opened habitat for adults and juveniles in upper Mill Creek, it did not solve all of the issues. Continued years of monitoring show that some adults are still observed spawning in the lower reaches where progeny are subject to high mortality from stream drying, suggesting the need for flow restoration actions. The program is currently evaluating a suite of actions designed to increase surface flow in Mill Creek, and our monitoring is continuing to play a role in helping guide the next steps of restoration.

Figure 3. Number and distribution of coho salmon redds counted during spawner surveys on Mill Creek above and below the site of a partial fish passage barrier before and after remediation which occurred during the summer of 2016 (dashed line in plot). During the winters of 2006 through 2009, surveys were conducted but no coho salmon redds were observed.

Lesson 1. Revealing unanticipated bottlenecks to population recovery: the role of streamflow

In the early years of the conservation hatchery program, managers prioritized spring (May–June) releases of young-of-year, hatchery-reared fish on or near spawning habitat in tributary streams. The rationale behind releasing fish at this young lifestage was to maximize the time that fish experienced natural selection and to increase the likelihood that they would imprint and return to their release stream in subsequent years as adults. During the spring months, Russian River tributaries generally have steady flows at temperatures that are ideal for coho salmon. However, post-release monitoring of the planted fish, which initially included snorkeling, habitat assessment, and electrofishing surveys, revealed that flow in many of the streams became intermittent over the course of the summer (July–October) and many of the planted fish perished from stranding, predation, or poor water quality (e.g., high temperatures and/or low dissolved oxygen).

At the time, managers considered degraded physical habitat to be a primary limiting factor to salmon recovery. The active removal of large woody debris from stream channels by private landowners, construction of impassable culverts and diversion dams, and elevated fine sediment loads from logging, agricultural land use conversion, and road construction, were all recognized as major factors contributing to salmon declines (NMFS, 2012). While water quantity and quality were also recognized as issues of concern, from the 1980s to the early 2000s restoration funding was almost exclusively oriented towards physical habitat improvements such as culvert replacement, riparian bank stabilization, and addition of in-stream wood structures (Christian-Smith and Merenlender, 2010).

As observations of stream drying became more frequent, the RRSSMP initiated focused monitoring and research to better understand the scope and nature of flow-limitations on salmonid survival and recovery. This was principally done in two ways. First, new stream survey methods were developed to rapidly assess the habitat available to support coho salmon over the summer. This involved repeated surveys conducted on foot by personnel carrying GPS units to map the presence of flowing water, isolated pools, and dry channel reaches (i.e., “wet/dry mapping”). These surveys were initially carried out on five flow-impaired high-priority coho salmon streams and with support from interns, AmeriCorps members, and VetCorps members, eventually grew to include over 40 streams. Findings from the surveys revealed that stream drying was a widespread occurrence in the basin (Figure 4), particularly in dry water years such as 2021, the driest water year between 2000 and 2024 (U.S. Drought Monitor, 2025). Second, to quantify the consequences of stream drying on summer-rearing coho salmon, intensive survival studies were integrated into the monitoring program. Using PIT-tagged fish, portable PIT detection systems, and mark-recapture methods, researchers were able to evaluate the influence of flow-related metrics on survival of juvenile coho salmon over the course of the summer. Studies confirmed that low and disconnected flow conditions are strongly associated with low survival of juvenile coho salmon rearing in natal stream habitat and that low dissolved oxygen also negatively influences survival (Obedzinski et al., 2018; Vander Vorste et al., 2020). Unpublished data from the RRSSMP has also documented unsuitably high water temperatures as an additional stressor in some streams. Subsequent research relying on data from the monitoring program has further shown that low flows pose a risk to outmigrating smolts in the spring (Kastl et al., 2022, 2025) and can delay or prevent adult salmon from migrating to spawning habitats in dry winters (Carlson et al., 2025).

Figure 4. (Left) Annual hydrographs for Austin Creek (USGS 11467200), a tributary to the Russian River (Figure 1), in a dry water year (2021) and wet water year (2017), with gray shading indicating the seasonal period of low flow (<0.05 m3 s-1). (Middle) Proportion of surveyed stream that was wet and dry in 2021 (top) and 2017 (bottom). (Right) Spatial extent of wet and dry stream reaches surveyed in 2021 (dry year). For reference, between 2000 and 2024, water year 2021 ranked as the driest and 2017 ranked as the 18th driest (U.S. Drought Monitor, 2025).

As evidence of the importance of flow as a bottleneck to recovery grew, managers and multidisciplinary partnerships began exploring new restoration strategies. These included programs focused on water conservation, with the goal of improving flows in tributary streams throughout the dry season by reducing or shifting the timing of surface water diversions by agricultural and residential water users. Pilot projects were also conducted to augment flow with water releases from storage ponds and tanks. Staff and resources from the RRSSMP were leveraged to conduct a controlled experiment to quantify the response of salmon to flow augmentation in the dry season (Rossi et al., 2023). They found that augmenting a flow-impaired stream with additional water in the dry season improved rearing habitat conditions for coho salmon and steelhead and enhanced over-summer survival, underscoring not only the importance of flow during the summer rearing period but also the effectiveness of flow-augmentation as a restoration tool. Monitoring data were also used to inform models that predict the spatial extent of stream drying (Moidu et al., 2021) and the effectiveness of different streamflow enhancement strategies at increasing flows during critical rearing and migration windows (Kobor et al., 2025), as well as decision support tools for prioritizing streamflow enhancement projects. In addition, managers relied on wetted habitat and snorkel count data from the RRSSMP to inform emergency fish relocations during drought years.

These examples highlight the importance of integrated monitoring programs in drawing attention to overlooked or underappreciated factors affecting salmon populations. Observations of drying streams and stranded fish challenged prevailing assumptions that physical habitat was the primary limiting factor to salmon populations and required that focus be broadened to include water quantity and the human activities that affect surface flows in streams. These insights, in turn, catalyzed new studies and novel management strategies designed to understand and mitigate the adverse effects of flow depletion on salmon.

Lesson 2. Importance of juvenile life history diversity in coho salmon recovery

The RRSSMP initially focused on life cycle monitoring (LCM) in four subwatersheds of the Russian River: Mill, Green Valley, Dutch Bill, and Willow (Figure 1). Between 2004 and 2025, nearly 1.2 million fish were released into the four LCM streams, including, on average, approximately 42,000 in each of the last 5 years. A fraction of all hatchery fish released into these streams are PIT-tagged (approximately 15–25%) along with modest numbers of natural-origin fish encountered during field surveys (3,682 natural-origin fish tagged between 2007 and 2024). These tagging efforts, in conjunction with our network of PIT antennas operated throughout the watershed, have facilitated multiple studies investigating movement patterns and life history expression of PIT-tagged fish.

When the RRSSMP began, the prevailing view in the region was that successful coho salmon were natal rearing fish, remaining in habitats in the vicinity of where they emerged from their redds (or were released, in the case of hatchery fish) until the time of emigration as yearling smolts in spring. However, a growing number of studies in Pacific Northwest streams documented that a portion of juveniles emigrated from natal stream habitat prior to their yearling spring and reared in off-channel, estuarine, and non-natal stream habitat (Peterson, 1982; Bramblett et al., 2002; Ebersole et al., 2006; Koski, 2009). We were interested in learning whether this was occurring in the Russian River population and whether fish expressing alternate rearing strategies could be contributing to adult returns. However, our use of seasonal migrant traps to monitor downstream movement of smolts between March and June precluded detection of migrating fish outside of this time period. To address this limitation, we installed year-round PIT antenna arrays in our LCM streams. We immediately began detecting tagged fish leaving the streams outside of the typical spring outmigration period, including in the fall and winter of their first year of life. Moreover, some of the early migrants were subsequently detected at antenna arrays in other tributaries and, later, as returning adults.

Observations of fish movement within and among tributaries prior to emigrating to the ocean have led to more focused studies examining patterns, drivers, and success of non-natal rearing coho salmon in the Russian River. For example, Obedzinski et al. (in review)1 documented a bimodal emigration pattern of juvenile hatchery coho salmon, with a subset of fish departing their tributary of origin in the fall or winter, whereas others emigrated later during the typical smolt emigration season. Early emigration was more common from higher gradient streams (≥ 1%), particularly in wetter years and when densities were higher, whereas streams with more low-gradient, floodplain habitat tended to retain fish (i.e., early emigration was rare). Similarly, an investigation of juvenile coho movement and rearing within Willow Creek demonstrated that a subset of fish depart the natal habitat early in life and rear in the alluvial valley bottom and tidal wetland habitat in the lower portion of the creek prior to emigrating to the Russian River during the spring outmigration season (Baker et al., 2025). In both studies, the authors found that non-natal rearers survived to contribute to the adult breeding population, and, though rare, in some years were the only adults that returned to particular streams. Similar to studies in other streams that documented the contribution of non-natal rearers to adult populations (Jones et al., 2014; Bennett et al., 2015), our work suggests that non-natal life histories are an important component of the Russian River coho salmon portfolio, contributing to the abundance of adult returns and to stability of the population complex by sustaining life history strategies that may be more successful in some years.

Fish movement data collected through the RRSSMP further suggests that early emigrants and smolt migrants move from their natal tributaries through the Russian River mainstem and into other (i.e., non-natal) tributaries prior to ocean entry (Baker et al. in prep)2. Systems with considerable low-gradient, floodplain habitat appear to receive the majority of such immigrants, especially Willow Creek, which enters the Russian River Estuary just 4.3 km upstream of the ocean. Juvenile fish from higher gradient systems, such as Dutch Bill Creek, have been detected moving through the Russian River mainstem in winter to access non-natal habitat in Green Valley, Mark West, and Willow creeks, in some cases more than 26 km upstream (Figure 5). Our interpretation is that such movement patterns reflect the ability of fish to exploit a mosaic of non-natal habitats available in the watershed which is likely critical to their resilience in the face of highly variable hydrologic conditions characteristic of California’s Mediterranean climate (Dettinger, 2011). However, we also recognize that the success of fish exhibiting non-natal movements is reduced by the loss and degradation of low-gradient floodplain habitat throughout the watershed as well as reduced connectivity between those habitats through migratory corridors such as the mainstem river. For example, recent work by Rossi et al. (2025) indicated that survival of acoustically tagged juvenile coho salmon migrating through the mainstem Russian River is variable and can be extremely low (0.14–0.61 across 4 years of study). Although the study took place in the spring season only, it suggests that the mainstem corridor could impose high risk to juvenile salmon trying to access non-natal habitats. These results also suggest that restoring non-natal habitats such as floodplain, wetland, and estuarine habitats, as well as the connectivity to access those habitats, would help to preserve diverse life history strategies of coho salmon in the Russian River watershed.

Figure 5. Natal and non-natal rearing strategies of juvenile coho salmon emigrating from Dutch Bill Creek. Different colored fish represent different juvenile rearing strategies. Lines indicate movement pathways during their first winter (upper panel) followed by their second spring when they migrate to the ocean as age-1 smolts (lower panel). For each line, the fish symbol(s) indicate the starting point(s) and the arrows indicate the end point(s) of the movement.

Contemporary salmon science suggests that a diversity of life histories is a critical ingredient for abundant and resilient salmon populations (Hilborn et al., 2003; Schindler et al., 2010). Results from the Russian River highlight that important dimensions of life history diversity persist in this endangered coho salmon complex, namely the presence of non-natal rearing strategies, but that habitat loss and degradation limit their success. These insights have supported the prioritization of projects to restore and reconnect floodplain, wetland, and off-channel habitat, and have motivated new studies aimed at evaluating different management strategies designed to support diverse life history pathways to rebuild salmon populations in the Russian River.

Lesson 3. Standardized methods and a centralized database are essential for data integration, analysis, and sharing

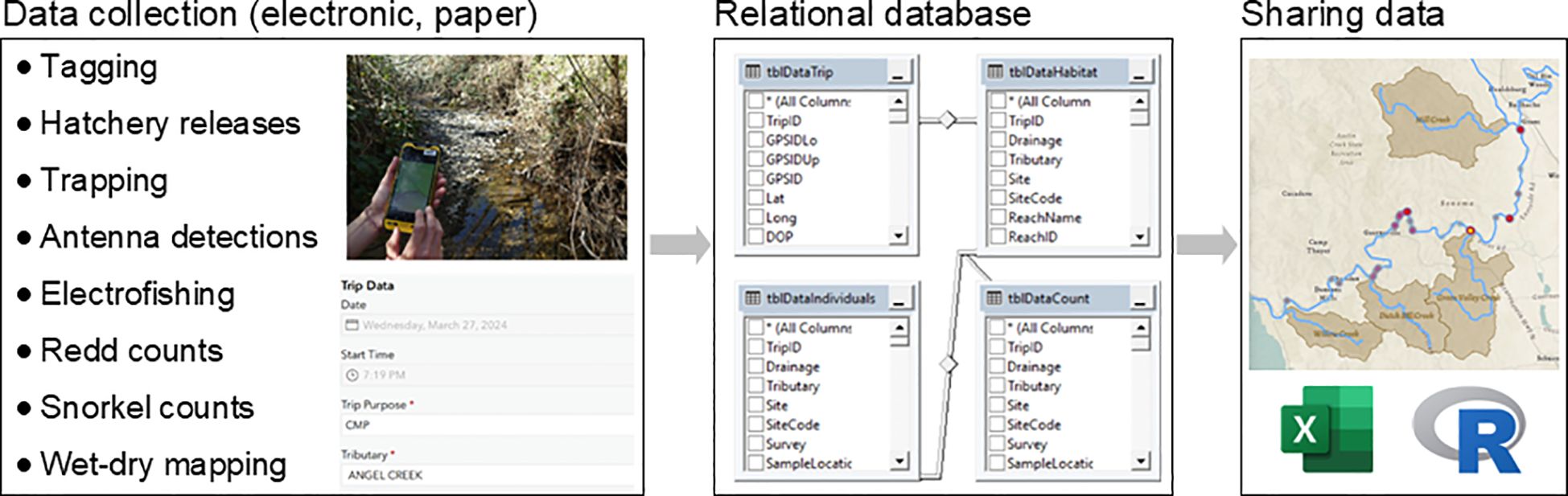

Fish monitoring programs are often initiated and maintained through relatively short-term (2–3 year) grant-funded projects that are designed to evaluate specific objectives linked to management interventions or regulatory requirements. In rare cases when there are opportunities to extend or establish longer-term monitoring programs, funding for field data collection is typically prioritized, with little thought towards data management and the design and maintenance of centralized databases. This, in part, reflects the desire of funders to direct resources towards on-the-ground projects and monitoring activities, but it also highlights how data management in monitoring programs is underappreciated (Bennett et al., 2016). In our experience, developing standardized data collection and management methods, including creation of a centralized database, is essential to any long-term monitoring program and has played a pivotal role in the success of the RRSSMP.

The early years of fish monitoring in the Russian River suffered from a lack of resources dedicated to data management. Our monitoring efforts initially focused on methods to effectively capture and count fish and we gave limited consideration to how best to organize the data once collected, or how the data might be ultimately used to assess progress towards achieving broader program goals. The result was a proliferation of data collected with different methods, in different formats, and stored in different locations that were difficult or impossible to relate to one another in space or time. Inconsistent QAQC procedures also led to variable data quality, further complicating data integration efforts. Managing the high volume of data produced by our monitoring programs was another challenge. As the number of tagged fish, stationary PIT antenna arrays, and project partners contributing data grew, it became necessary to develop a shared database capable of storing and relating information from different sources.

Over the last decade, we have made great strides in implementing standardized data collection protocols, QAQC procedures, and a centralized database that facilitates efficient data sharing and summarization of millions of records. The hub of our current data management system is a Structured Query Language (SQL) relational database which accommodates large quantities of tabular and spatial data. The system is particularly well suited for relating “trip-level” data containing time and location information (i.e., parent data) to hierarchical levels of habitat, count and/or individual fish data (i.e., child data). Using this database structure, there is flexibility in data collection methods (e.g., paper datasheets, various electronic data collection devices and applications; Figure 6). Once uploaded to our database, data can be queried for summarization and analysis using various front-end programs, such as R, Microsoft Excel, and ArcGIS Pro. This has allowed us to more efficiently and immediately inform contemporary questions while providing the structure to accommodate future unanticipated data that may become relevant to salmon recovery actions. It has also been particularly useful in facilitating data collection by multiple entities and sharing data in different formats to communicate findings to diverse audiences (Box 3; Figure 7). The current process of data collection, QAQC, and curation has now matured to the point where monitoring data can be shared with partners on the same day it is collected thus supporting real-time decision-making, public outreach, and educational programming.

Figure 6. General structure of the Russian River monitoring data flow from data collection (left) to upload into to a relational database (center) to examples of different front-end programs used to share results (right).

Box 3. Russian River monitoring data dashboards.

Adopting standardized methods and development of a centralized database has facilitated new and valuable ways of interacting with Russian River monitoring data. To support a diverse audience of stakeholders (e.g., resource managers, restoration practitioners, scientists, conservationists, modelers, students, streamside residents, the general public), we found that it is beneficial to share data in a variety of formats. Traditional dissemination through reports, presentations, technical meetings, and publications continue to offer value, but geospatial representation in mapping dashboards has been an especially useful means of displaying both in-season and historical datasets such as redd counts, juvenile snorkel counts, stocking locations, and dry season surface flow connection (e.g., Figure 7; Russian River Salmon and Steelhead Monitoring Program) (https://arcg.is/1DaDHD). Such public-facing dashboards are helpful for decision making by resource managers and restoration practitioners and also allow streamside residents to view monitoring results and learn what we are observing on their property. Other applications include more tailored dashboards that are used in-season by resource managers to identify locations for broodstock collection and fish rescues as well as when and where to initiate flow augmentations for the benefit of summer-rearing fish. Project-specific dashboards can help project teams coordinate monitoring and restoration activities (e.g., Willow Creek Dashboard (https://arcg.is/0riGbW)) or identify and prioritize flow enhancement projects (e.g., Pena Creek Flow Enhancement Decision Support Tool (https://arcg.is/1DnaLS2)). Spatial data from our centralized SQL database is integrated with ArcGIS Enterprise, allowing seamless integration with web GIS while supporting field data collection using applications such as S123 and Field Maps. While in the field, survey crews can easily collect data on phones or tablets, and view maps to locate survey reaches and monitoring sites, understand landowner access limitations, and reference previously-collected data. Overall, this has exponentially increased the value and utility of our monitoring data by making it accessible to diverse audiences in meaningful timeframes.

Figure 7. Example of interactive dashboard displaying distribution and density of juvenile salmonids observed during annual snorkel surveys in the Russian River watershed. The dashboard is used by resource managers, restoration practitioners, biologists, streamside residents, and the general public to view in-season results in relation to previous years of data.

Summary and discussion

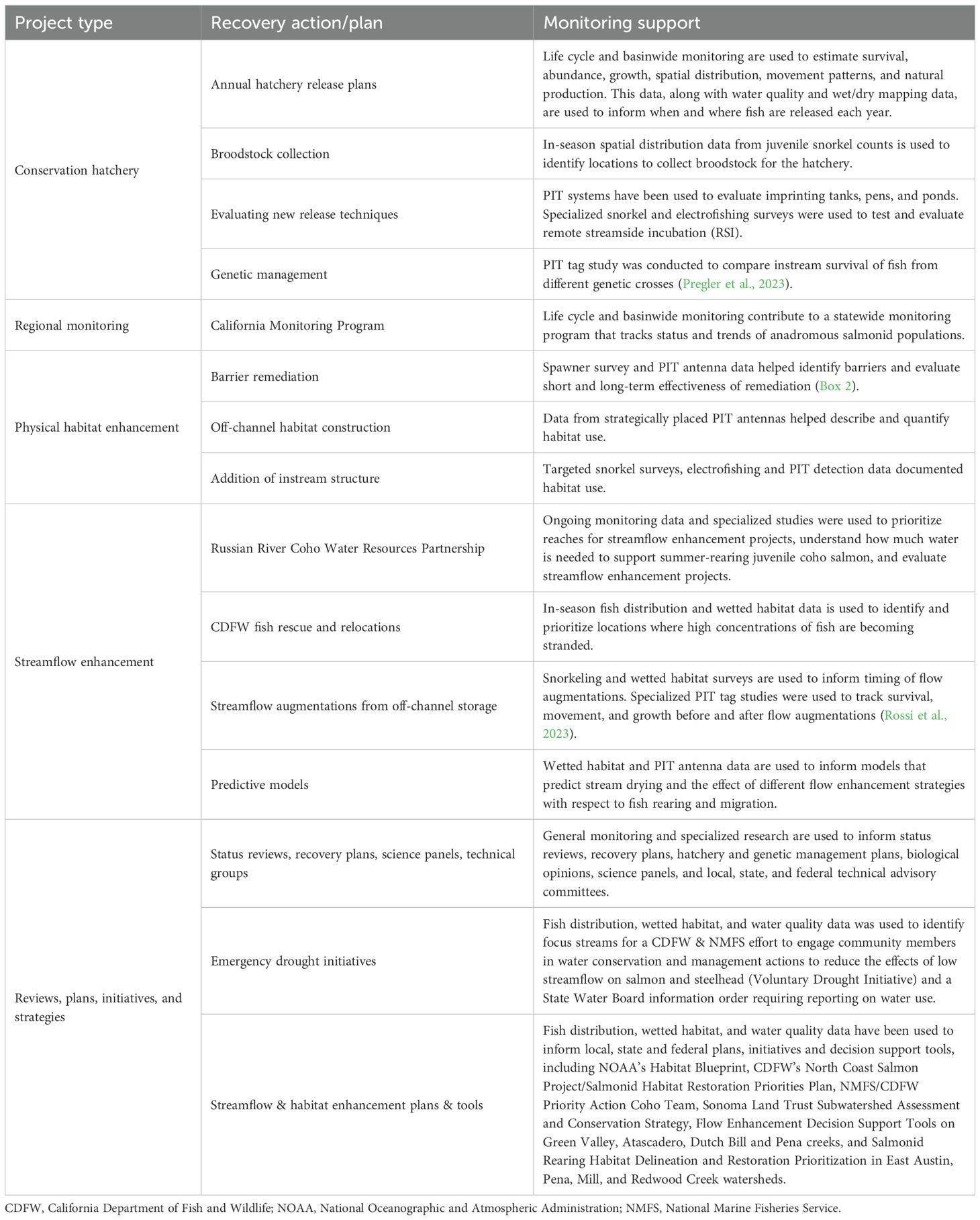

Monitoring in the Russian River evolved from a series of disconnected efforts evaluating individual projects to a watershed-wide program that tracks complex salmon population dynamics at multiple spatiotemporal scales and provides the necessary context to interpret biological responses to a variety of management interventions and environmental stressors (Table 1). By adopting multiscale monitoring approaches using a range of tools, the RRSSMP has effectively tracked an increasing abundance of coho salmon over time, but has also revealed critical bottlenecks to population recovery, including the role of streamflow. Our program has also increased understanding of juvenile emigration phenology and has drawn attention to the important role of life history diversity in promoting population stability and recovery. Standardized data collection, a centralized database, and new spatially explicit methods of interacting with data have allowed us to share results with a diversity of partners at timeframes relevant for management actions. The underlying structure of the monitoring program also serves as a platform for student projects and training opportunities for the next generation of scientists and resource managers.

Table 1. Coho salmon recovery efforts that have been informed by the Russian River Salmon and Steelhead Monitoring Program.

Importance of multiscale approaches

Fausch et al. (2002) highlight the importance of multiscale approaches to monitoring, including overlooked intermediate spatiotemporal scales (e.g., 1–100 km and 5–50 years) that are particularly critical for understanding and conserving stream fish populations. Adopting a multiscale monitoring approach in the Russian River helped us to identify and contextualize surface flow disconnection as a factor limiting juvenile oversummer survival by coupling direct observations of fish mortality from high-resolution pool-scale PIT tag studies with reach and watershed scale snorkel counts and wet dry mapping. Our nested spatiotemporal monitoring program also helped draw our attention to underappreciated forms of juvenile life history diversity, particularly the prevalence of non-natal rearing fish that are moving to low-gradient habitats located in different parts of the watershed in fall and winter. Monitoring at longer temporal scales (e.g., decades) also provides unique opportunities to learn about the effects of infrequent disturbance events, such as extreme drought, floods, and wildfire on fish population dynamics. For example, long-term data from the Russian River contributed to a regional study that showed the consequences of an extreme drought year that caused a flow-phenology mismatch during the breeding season of three salmonid species along the coast of California (Carlson et al., 2025). Such studies are particularly important for helping to understand and predict how extreme events can influence at-risk populations.

Expanding the monitoring toolbox

The RRSSMP uses a combination of physical capture methods (trapping, electrofishing, seining), visual observations (redd and snorkel surveys), and passive detection systems (PIT and acoustic systems, video) that, when used in combination, have greatly increased our understanding of fish population dynamics in the watershed. For example, running year-round PIT antennas in conjunction with seasonally-operated downstream migrant traps allows us to estimate emigration timing, abundance, size, and survival of juveniles in the LCM streams. To extend estimates of survival through the mainstem river and estuary (where trapping and PIT antenna operation are not feasible), we have tracked fish using acoustic telemetry. Studies in other watersheds have paired capture methods (e.g., carcass surveys or downstream migrant trapping) with otolith analysis to characterize life history diversity across watersheds (Brennan et al., 2019; Ryan, 2024; Chen et al., 2025) and remote sensing is increasingly used to relate watershed-scale fish distribution to environmental conditions (Torgersen et al., 1999; Clawson et al., 2022). As new technologies continue to unfold and we incorporate them into our monitoring programs, our ability to provide managers with information and tools at scales appropriate for conservation and management actions will also improve (Fausch et al., 2002). However, the value of consistent and comparable long-term data must be carefully balanced against any advantages that new methods may confer. Changing methods midway through a long-term monitoring program can come with costs if legacy methods are not comparable or relatable to new ones. For example, we have found that many of our earlier datasets that include information about abundance and distribution are often dismissed because they were collected using different approaches (e.g., documenting redd locations hand-drawn on maps versus using GPS). Incorporating these older datasets into our time series is important because they demonstrate the lack of spawning (and presumably adult returns) in years prior to implementation of the conservation hatchery program.

We view the RRSSMP database as yet another monitoring tool that in its general form could serve as a template for long-term monitoring programs in other watersheds. There is an increasing need to make data comparable at regional levels (e.g., to facilitate comparison of status and trends in salmon and steelhead populations, it is important that monitoring data are collected using consistent survey and estimation methods among watersheds). In 2013, we began implementing California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s California Monitoring Plan (CMP) in the Russian River watershed. The guiding CMP document (Adams et al., 2011) outlines monitoring approaches needed to maintain that consistency. Although this is an important first step, transforming the data we collect into information that managers, planners, and recovery practitioners can apply is also critical. Some of the tools we have developed for the Russian River could be used for this purpose. We also see new opportunities to streamline and lower barriers to building and maintaining centralized databases for long-term monitoring programs. For example, the rise of data science as a field, including training opportunities at the intersection of data science and environmental science, is now creating a pipeline of skilled individuals who are well-poised to contribute to the evolution of environmental monitoring programs in service of conservation and recovery efforts.

Monitoring challenges

Building and maintaining the RRSSMP over the past 20 years has not been easy. Securing access to streams on private land and communicating with landowners is a constant substantial effort that we did not adequately build into our workflow in the early stages of monitoring. Funding is a consistent concern and developing staff to have both database skills and ecological knowledge has required significant investments in time and training. Our funding has been pieced together from inconsistent sources, resulting in unexpected gaps filled by last-minute funding from various sources and/or transfer of field activities to other organizations working in the watershed. There was also skepticism by some in adopting new approaches that were unfamiliar. For example, in the early stages of our program, there was substantial resistance to PIT tagging, and many questioned the value of individual-based approaches for monitoring fish populations. Further, even after we demonstrated the utility of PIT monitoring to estimate population metrics, long-held assumptions about the prevalence of natal juvenile rearing delayed acceptance of the notable diversity of non-natal and inter-tributary movement that was revealed by PIT tag detections.

We also encountered challenges related to monitoring in a watershed the size of the Russian River (3,800 km2). From the beginning, we recognized that it would be impractical to construct and operate a single LCM station that counts all smolts leaving and all adults returning to the watershed. Instead, we chose to track populations in multiple, smaller subwatersheds (Figure 1), but this came with tradeoffs. The most obvious is that fish could be produced from and return to places in the watershed that we are not monitoring. This means that our adult abundance estimates are likely a biased representation of the true population size, although our network of PIT antenna arrays, including those outside of the LCMs, helps offset this issue somewhat. Documentation of inter-tributary movements, while extremely valuable in describing life history diversity and habitat-use, exposes additional biases in estimating natural-to-hatchery origin, smolt-to-adult, and spawner-to-redd ratios. Despite these issues, PIT antenna arrays in the four LCMs have been extremely useful for estimating overwinter survival and abundance of natally-reared coho salmon smolts in a way that minimizes fish handling and improves the value of our data for informing progress toward population recovery.

Partnerships and collaborations

In the RRSSMP, partnerships have been a necessity for many reasons. Collaborations between different monitoring entities are necessary to make the most efficient use of limited resources. Partnerships have also been key for translating the monitoring data collected through the RRSSMP into focused recovery actions. In particular, our monitoring program helped to create communication networks that enabled partners to rapidly respond to unanticipated and urgent issues as soon as they were discovered (e.g., fish strandings, passage barriers, sediment inputs, invasive species introductions, chemical spills). Partnerships supported by the RRSSMP have also become catalysts for creative new recovery actions, including projects to increase streamflow for fish while also creating water reliability and reduced fire risk for streamside residents (Table 1; Gold Ridge RCD et al., 2022). While working with different groups that each have slightly different missions and objectives can be time-consuming and difficult in some cases, over time, we have found that such collaborations have created positive feedback loops between monitoring and restoration, which ultimately helps advance species’ recovery.

Training and workforce development

An unrecognized benefit of long-term monitoring programs is the opportunities they provide for the developing workforce. Whether entering the field of resource management, conservation science, environmental policy, or academia, hands-on experience participating in a monitoring program provides individuals with fundamental knowledge and skills that cannot be learned in a classroom. By offering internships, hosting AmeriCorps members, and hiring entry-level seasonal technicians, durable monitoring programs provide students and early-career scientists and resource managers with important opportunities to learn about ongoing conservation issues and efforts to address them while gaining skills in field techniques and data processes. Individuals build their resumes and gain exposure to different organizations, career paths, and potential future employers. The RRSSMP has effectively served as a pipeline to graduate school and employment in the natural resources field.

Long-term monitoring programs also serve as a hub for student research projects. While there is increasing acknowledgment for the importance of place-based science (Able, 2016; Quinn, 2018), the 2–5 year window of a typical graduate program does not afford the time needed to develop relationships and cultivate trust with local stakeholders and communities, nor collect long-term datasets. However, this can be resolved through collaboration – monitoring programs provide long-term datasets, context, and connections while students offer new perspectives, analytical rigor, and the ability to publish results. For this reason, long-term monitoring watersheds are ideal places to link management with academia to address applied research questions that benefit both local communities and broader scientific audiences.

Conclusions

The RRSMP is an example of how essential broad-scale monitoring is to salmon recovery. In the early 2000s, Russian River coho salmon numbers were so depressed that without hatchery intervention, the population would have likely disappeared. Our work has been instrumental in guiding hatchery-based recovery strategies, but it has also provided a source of fish to uncover the overriding importance of those factors that are the greatest impediments to recovery of self-sustaining salmon populations. While the original goal of the RRSMP program was to evaluate the success of the conservation hatchery program, minor adaptations have enabled evaluation of a broader suite of interventions from barrier removal (Box 2; Figure 3) to flow augmentation (Rossi et al., 2023). Our work highlights the importance of multiscale sampling, extensive coordination, partnerships, database centralization, and new technologies that build on traditional monitoring approaches to directly advance salmon recovery. We argue that integrated, long-term monitoring adequate to capture the complexities of the organisms we are studying and the ecosystems on which they depend is not just an option but a necessity if we are serious about making meaningful progress towards salmon recovery. Resources must be invested in field data collection, but equally important is an investment in database support and communication tools to better leverage monitoring data. Given the dire state of salmon populations along the Pacific Coast and the increasing threats of human population growth and climate change, it is more important than ever that we make efficient and informed choices regarding recovery strategies and that we support the robust monitoring efforts needed to effectively guide those choices.

Author contributions

MO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SN: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AB: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NB: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. PO: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Over the last 20 years, primary funding for Russian River salmonid monitoring was provided by the US Army Corps of Engineers and California Department of Fish and Wildlife through multiple contracts and grants. Additional monitoring support was provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Sonoma County Water Agency, University of California, and California Sea Grant. Funding for specialized studies was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Wildlife Conservation Board, the Sonoma County Fish and Wildlife Commission, and Trout Unlimited.

Acknowledgments

We thank California Sea Grant and Sonoma Water field monitoring crews for many years of data collection and Conte Anadromous Fish Research Center for support with PIT antenna design. Bob Coey, Manfred Kittel, David Manning, and David Lewis were instrumental in the development of the monitoring program and providing ongoing support. We thank Ben White, Rory Taylor, Louise Conrad, Brett Wilson and the hatchery crews for their collaboration in producing, tagging, and releasing fish. We acknowledge Andrew McClary and Andrea Pecharich for database development and management and creating innovative data collection applications. Sean Gallagher offered valuable advice and served as an advisor as we began implementation of the California Monitoring Plan. Trout Unlimited, Gold Ridge and Sonoma Resource Conservation Districts, and Occidental Arts and Ecology Center provided critical insights that helped shape many of our monitoring and research questions. Finally, we thank the streamside landowners who provided field and hatchery crews access to the streams as well as two reviewers who offered insightful comments and suggestions for improving our manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Obedzinski, M., Grantham, T., Horton, G., Pess, G., and Carlson, S. Geomorphic, hydroclimatic, and biotic factors influence juvenile emigration timing in a southern coho salmon population. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. In review.

- ^ Baker, H., Obedzinski, M., Grantham, T., and Carlson, S. Watershed characteristics affect the frequency and phenology of dispersal to non-natal streams by juvenile salmon. In prep.

References

70 FR 37160 (2005). 70 FR 37160 - Endangered and Threatened Species: Final Listing Determinations for 16 ESUs of West Coast Salmon, and Final 4(d) Protective Regulations for Threatened Salmonid ESUs (Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration). Available online at: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-2005-06-28/05-12351 (Accessed July 30, 2025).

Able K. W. (2016). Natural history: An approach whose time has come, passed, and needs to be resurrected. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 2150–2155. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsw049

Adams A. B., Boydstun L. B., Gallagher S. P., Lacy M. K., McDonald T., and Shaffer K. E. (2011). California coastal salmonid population monitoring: Strategy, design, and methods (California: California Department of Fish and Game).

Baker H. K., Obedzinski M., Grantham T. E., and Carlson S. M. (2025). Variation in salmon migration phenology bolsters population stability but is threatened by drought. Ecol. Lett. 28. doi: 10.1111/ele.70081, PMID: 39988798

Bennett S., Pess G., Bouwes N., Roni P., Bilby R., Gallagher S., et al. (2016). Progress and challenges of testing the effectiveness of stream restoration in the Pacific Northwest using intensively monitored watersheds. Fisheries 41, 92–103. doi: 10.1080/03632415.2015.1127805

Bennett T., Roni P., Denton K., McHenry M., and Moses R. (2015). Nomads no more: Early juvenile coho salmon migrants contribute to the adult return. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 24, 264–275. doi: 10.1111/eff.12144

Bilby R. E., Currens K. P., Fresh K. L., Booth D. B., Fuerstenberg R. R., and Lucchetti G. L. (2024). Why aren’t salmon responding to habitat restoration in the pacific northwest?. Fisheries. 49, 16–27. doi: 10.1002/fsh.10991

Bisson P., Hillman T., Beechie T., and Pess G. (2024). Managing expectations from intensively monitored watershed studies. Fisheries. 49, 8–15. doi: 10.1002/fsh.10992

Bramblett R. G., Bryant M. D., Wright B. E., and White R. G. (2002). Seasonal use of small tributary and main-stem habitats by juvenile steelhead, coho salmon, and Dolly Varden in a southeastern Alaska drainage basin. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 131, 498–506. doi: 10.1577/1548-8659(2002)131%3C0498:SUOSTA%3E2.0.CO;2

Brennan S., Schindler D., Cline T., Walsworth T., Buck G., and Fernandez D. (2019). Shifting habitat mosaics and fish production across river basins. Science 364, 783–786. doi: 10.1126/science.aav4313, PMID: 31123135

Carlson S. M., Pregler K. C., Obedzinski M., Gallagher S. P., Rhoades S. J., Hazard C.--., et al. (2025). Anatomy of a range contraction: Flow-phenology mismatches threaten salmonid fishes near their trailing edge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 122, 2415670122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2415670122, PMID: 40163726

CDFG (2002). Status Review of California Coho Salmon North of San Francisco: Report to the California Fish and Game Commission (California Department of Fish and Game). Available online at: https://cawaterlibrary.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SAL_Coho_StatusNorth_2002.pdf (Accessed July 30, 2025).

CDFW (2025). California Fish Passage Assessment Database. Available online at: https://www.calfish.org/programsdata/habitatandbarriers/californiafishpassageassessmentdatabase.aspx (Accessed September 11, 2025).

Chen E. K., Lumahan K., Johnson R. C., Phillis C. C., Whitman G., Sturrock A. M., et al. (2025). Juvenile life history, migration, and habitat use of natural-versus hatchery-origin Chinook Salmon. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 154 (4), 440–455. doi: 10.1093/tafafs/vnaf021

Christian-Smith J. and Merenlender A. M. (2010). The disconnect between restoration goals and practices: A case study of watershed restoration in the Russian River basin, California. Restor. Ecol. 18, 95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2008.00428.x

Clawson C. M., Falke J. A., Bailey L. L., Rose J., Prakash A., and Martin A. E. (2022). High-resolution remote sensing and multistate occupancy estimation identify drivers of spawning site selection in fall chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) across a sub-Arctic riverscape. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 79, 380–394. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2021-0013

Dettinger M. (2011). Climate change, atmospheric rivers, and floods in California - A multimodel analysis of storm frequency and magnitude changes. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 47, 514–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2011.00546.x

Ebersole J., Wigington P., Baker J., Cairns M., Church M., Hansen B., et al. (2006). Juvenile coho salmon growth and survival across stream network seasonal habitats. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 135, 1681–1697. doi: 10.1577/T05-144.1

Fausch K., Torgersen C., Baxter C., and Li H. (2002). Landscapes to riverscapes: Bridging the gap between research and conservation of stream fishes. Bioscience 52, 483–498. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052%5B0483:LTRBTG%5D2.0.CO;2

Gold Ridge RCD, California Sea Grant, Trout Unlimited, Occidental Arts and Ecology Center, and Sonoma RCD (2022). The Russian River Coho Water Resources Partnership: Dedicated to improving water reliability for fish and people (Santa Rosa, California). Available online at: https://coho-partnership.org/ (Accessed July 30, 2025).

Gustafson R. G., Waples R. S., Myers J. M., Weitkamp L. A., Bryant G. J., Johnson O. W., et al. (2007). Pacific salmon extinctions: Quantifying lost and remaining diversity. Conserv. Biol. 21, 1009–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00693.x, PMID: 17650251

Hilborn R., Quinn T., Schindler D., and Rogers D. (2003). Biocomplexity and fisheries sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 6564–6568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037274100, PMID: 12743372

ISRP (2016). Conceptual model of watershed hydrology, surface water and groundwater interactions and stream ecology for the Russian River watershed (Napa, CA: Russian River Independent Science Review Panel).

Jones K., Cornwell T., Bottom D., Campbell L., and Stein S. (2014). The contribution of estuary-resident life histories to the return of adult Oncorhynchus kisutch. J. Fish Biol. 85, 52–80. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12380, PMID: 24766645

Kastl B., Obedzinski M., Carlson S., Boucher W., and Grantham T. (2022). Migration in drought: Receding streams contract the seaward migration window of endangered salmon. Ecosphere 13 (12), e4295. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.4295

Kastl B., Obedzinski M., Carlson S. M., Pierce S. N., van Docto M. M., Skorko K. W., et al. (2025). Navigating shallow streams: Effects of changing stream water depths on outmigration of endangered coho salmon. River Res. Appl. 41 (8), 1726–1736. doi: 10.1002/rra.4466

Kobor J., O’Connor M., and Obedzinski M. (2025). Developing effective flow enhancement strategies for salmonid recovery and climate change adaptation in central California’s coastal watersheds. River Res. Appl.. doi: 10.1002/rra.70074

Koski K. (2009). The fate of coho salmon nomads: The story of an estuarine-rearing strategy promoting resilience. Ecol. Soc. 14, 4. doi: 10.5751/ES-02625-140104

Lovett G. M., Burns D. A., Driscoll C. T., Jenkins J. C., Mitchell M. J., Rustad L., et al. (2007). Who needs environmental monitoring?. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 253–260. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5%5B253:WNEM%5D2.0.CO;2

Maxwell D. and Jennings S. (2005). Power of monitoring programmes to detect decline and recovery of rare and vulnerable fish. J. Appl. Ecol. 42, 25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01000.x

Moidu H., Obedzinski M., Carlson S., and Grantham T. (2021). Spatial patterns and sensitivity of intermittent stream drying to climate variability. Water Resour. Res. 57 (11), 1–14. doi: 10.1029/2021WR030314

Nehlsen W., Williams J., and Lichatowich J. (1991). Pacific Salmon at the crossroads - Stocks at risk from California, Oregon, Idaho, and Washington. Fisheries. 16, 4–21. doi: 10.1577/1548-8446(1991)016%3C0004:PSATCS%3E2.0.CO;2

NMFS (2012). Final recovery plan for Central California Coast coho salmon evolutionarily significant unit (Santa Rosa, California: National Marine Fisheries Service).

NMFS (2016). Final Coastal Multispecies Recovery Plan for California Coastal Chinook Salmon, Northern California Steelhead and Central California Coast Steelhead (Southwest Region, Santa Rosa, California: National Marine Fisheries Service). Available online at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/document/final-coastal-multispecies-recovery-plan-california-coastal-chinook-salmon (Accessed July 30, 2025).

Obedzinski M., Pierce S., Horton G., and Deitch M. (2018). Effects of flow-related variables on oversummer survival of juvenile coho salmon in intermittent streams. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 147, 588–605. doi: 10.1002/tafs.10057

Peterson N. (1982). Immigration of juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus-kisutch) into riverine ponds. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 39, 1308–1310. doi: 10.1139/f82-173

Pregler K., Obedzinski M., Gilbert-Horvath E., White B., Carlson S., and Garza J. (2023). Assisted gene flow from outcrossing shows the potential for genetic rescue in an endangered salmon population. Conserv. Lett. 16, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/conl.12934

Quinn T. P. (2018). From magnets to bears: Is a career studying salmon narrow or broad?. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 75, 1546–1552. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsy055

Radinger J., Britton J. R., Carlson S. M., Magurran A. E., Alcaraz-Hernández J. D., Almodóvar A., et al. (2019). Effective monitoring of freshwater fish. Fish Fish. 20, 729–747. doi: 10.1111/faf.12373

Reeves G. H., Hall J. D., Roelofs T. D., Hickman T. L., and Baker C. O. (1991). Rehabilitating and modifying stream habitats. Influences of Forest and Rangeland Management on Salmonid Fishes and Their Habitats (American Fisheries Society Special Publication 19, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland), 519–557.

Roni P., Beechie T., Bilby R., Leonetti F., Pollock M., and Pess G. (2002). A review of stream restoration techniques and a hierarchical strategy for prioritizing restoration in Pacific Northwest watersheds. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 22, 1–20. doi: 10.1577/1548-8675(2002)022%3C0001:AROSRT%3E2.0.CO;2

Rossi G. J., Obedzinski M., Pneh S., Pierce S. N., Boucher W. T., Slaughter W. M., et al. (2023). Flow augmentation from off-channel storage improves salmonid habitat and survival. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 43, 1772–1788. doi: 10.1002/nafm.10954

Rossi G., Horton G., Shaffer J., Georgakakos P., Loomis C., and Obedzinski M.. (2025). Risky mainstems are a poorly understood constraint on salmon recovery in coastal California. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. in press. doi: 10.1093/najfmt/vqaf095

Ryan R. (2024). Resilience of an Endangered Salmon Complex: Understanding the Relationships Between Habitat Heterogeneity, Environmental Variability, and Population Diversity (Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley, United States – California). Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/3111187631/abstract/19C20349BA204CA8PQ/1.

Schindler D., Hilborn R., Chasco B., Boatright C., Quinn T., Rogers L., et al. (2010). Population diversity and the portfolio effect in an exploited species. Nature 465, 609–612. doi: 10.1038/nature09060, PMID: 20520713

Schmeller D. S., Böhm M., Arvanitidis C., Barber-Meyer S., Brummitt N., Chandler M., et al. (2017). Building capacity in biodiversity monitoring at the global scale. Biodivers Conserv. 26, 2765–2790. doi: 10.1007/s10531-017-1388-7

SEC (1996). A history of the salmonid decline in the Russian River (Potter Valley: Steiner Environmental Consulting).

Tarzwell C. M. (1937). Experimental evidence on the value of trout stream improvement in Michigan. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 66, 177–187. doi: 10.1577/1548-8659(1936)66%5B177:EEOTVO%5D2.0.CO;2

Torgersen C. E., Price D. M., Li H. W., and McIntosh B. A. (1999). Multiscale thermal refugia and stream habitat associations of Chinook salmon in northeastern Oregon. Ecol. Appl. 9, 301–319. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009%5B0301:MTRASH%5D2.0.CO;2

U.S. Drought Monitor (2025). Current Map | U.S. Drought Monitor. Available online at: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap.aspx (Accessed September 12, 2025).

Keywords: intensive watershed monitoring, long-term monitoring, coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, conservation hatchery, life history diversity, freshwater fish conservation, data management

Citation: Obedzinski M, Horton GE, Nossaman Pierce S, Bartshire A, Bauer N, Olin PG, Carlson SM and Grantham TE (2025) Lessons learned from integrated long-term monitoring of a coho salmon population complex in the Russian River watershed. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1690506. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1690506

Received: 22 August 2025; Accepted: 06 October 2025;

Published: 17 December 2025.

Edited by:

Peter Bisson, Independent Researcher, Olympia, WA, United StatesReviewed by:

Joe Anderson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, United StatesMaryAnn Madej, United States Geological Survey (USGS), United States

Copyright © 2025 Obedzinski, Horton, Nossaman Pierce, Bartshire, Bauer, Olin, Carlson and Grantham. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariska Obedzinski, bW9iZWR6aW5za2lAdWNzZC5lZHU=

Mariska Obedzinski

Mariska Obedzinski Gregg E. Horton

Gregg E. Horton Sarah Nossaman Pierce1

Sarah Nossaman Pierce1 Stephanie M. Carlson

Stephanie M. Carlson Theodore E. Grantham

Theodore E. Grantham