- Science Division, Fish Program, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, WA, United States

Streams supporting low abundance salmon populations are often targeted for restoration, yet evidence for population-scale increases in fish abundance following stream habitat treatments are rare. In order to characterize the influence of density dependence on the fish responses to restoration, we fit a series of Ricker stock-recruit models to coho salmon life cycle monitoring data from seven streams within two Intensively Monitored Watersheds (IMWs). We found strong evidence for density dependence overall, but the strength of density dependence varied considerably among locations and across life stages. In particular, we observed a strong contrast in patterns of density dependence in the Lower Columbia IMW (WA) compared to the Hood Canal IMW (WA). We observed consistently strong density dependence in the Lower Columbia IMW, and an increase in abundance following restoration in Abernathy Creek appeared to result from release from density dependent constraints on productivity at the parr to smolt stage. By contrast, we did not detect a fish response to restoration in either Big Beef or Little Anderson creeks in the Hood Canal IMW, both characterized by weak density dependence. Furthermore, a modelling exercise indicated large spawner abundances probing habitat capacity limitations increased the likelihood of detecting a fish response to stream restoration, compared to smaller spawner abundances. Taken together, these results suggest that management strategies that test juvenile capacity limits by saturating the spawning grounds with adults give the greatest opportunity to observe the increases in salmon population abundance that motivate stream restoration efforts in the Pacific Northwest.

1 Introduction

Stream restoration is a foundational component of salmon recovery efforts, and significant resources are dedicated towards improving salmon habitat throughout the Pacific Northwest (Katz et al., 2007). Frequently, low abundance populations are targeted for restoration, in large part because agencies often prioritize funding opportunities for population segments listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (Barnas et al., 2015). A better understanding of how biological baselines, such as initial population abundance, influence fish responses to restoration would aid in planning, prioritizing and implementing habitat actions targeting salmon recovery (Bilby et al., 2023).

Research on stream restoration intended to benefit salmon populations has focused on developing techniques that restore habitat-forming processes and build resilience into river ecosystems (Beechie et al., 2013). In practical terms, this work has yielded prioritization of different restoration techniques (Roni et al., 2002) and models to identify habitat factors limiting salmon populations (Jorgensen et al., 2021; Scheuerell et al., 2006). Monitoring studies have demonstrated that restoration can produce desired habitat outcomes and benefit fish, though most examples of fish response are at the reach, not population, scale (Roni et al., 2015, 2008). Yet restoration practitioners face significant constraints in funding and land ownership (i.e., access to potential restoration sites). As a result, there is a need to validate stream restoration as an effective approach to salmon recovery, as broad-scale assessments have shown little response by salmon (Bilby et al., 2023; Jaeger and Scheuerell, 2023).

Density dependence, the ecological process by which population abundance influences rates of productivity (e.g., smolts per spawner), may affect how salmon respond to restoration, or whether they respond at all (ISAB, 2015). Under strong density dependence, abundance exceeds the total habitat capacity for spawning or rearing, and limitations on territorial space or food availability reduce productivity. Under weak density dependence, the total available habitat exceeds the abundance of fish that can occupy it, and there are minimal or weak limitations on productivity. Depending on the technique and implementation, effective stream restoration might increase total habitat capacity and hence alleviate density dependence (Copeland et al., 2020; Greene et al., 2025). By contrast, density independent approaches to population recovery often focus on migratory survival (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2024).

In this paper, we examine how initial density dependent processes affect the fish response to stream restoration. Using coho salmon life cycle monitoring data from the Hood Canal and Lower Columbia Intensively Monitored Watersheds (IMWs), we fit a series of stock-recruit models to describe variation in the strength of density dependence over time, between locations, and among life stages. We test for differences in productivity and density dependence before versus after restoration, albeit with few annual observations after restoration. Finally, we present a series of hypothetical restoration response models that assess our ability to detect changes in fish productivity when density dependence is strong compared to when density dependence is weak.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study watersheds

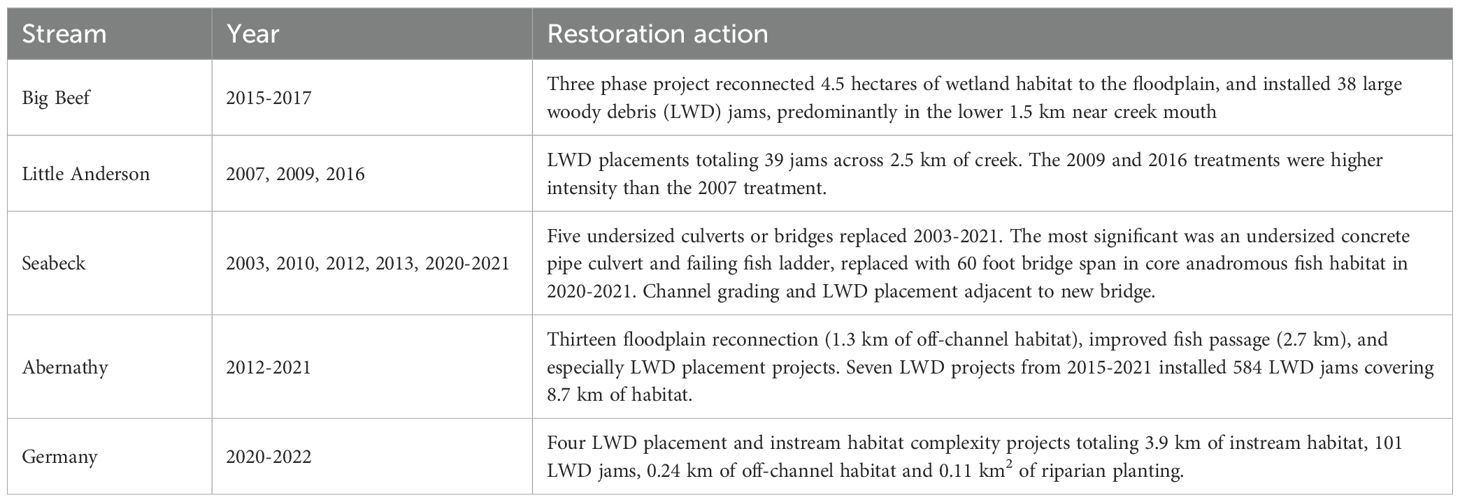

Our study consisted of two IMWS, one in the Lower Columbia region and one located in Hood Canal, both located in Washington State (Figure 1). Both IMWs included creeks designated as treatment streams targeted for stream restoration and a reference stream intended to account for natural environmental variation unrelated to restoration (Table 1). In both IMWs, restoration aimed to improve lateral connectivity with the floodplain, longitudinal connectivity (passage for fish, wood and sediment), and channel complexity through actions such as culvert replacement, dike removal, and large woody debris (LWD) addition (Table 2).

Figure 1. Map of Hood Canal and Lower Columbia Intensively Monitored Watersheds. Gray shading denotes watershed boundaries, see Table 1 for two letter watershed abbreviations.

Table 2. Summary of restoration treatments intended to boost salmon populations during the 2003 to 2022 study period.

Restoration treatments occurred over multiple years. For the purpose of analysis, we defined the start of the restoration period as the year in which substantial cumulative restoration had occurred, potentially of sufficient magnitude to elicit a response in fish abundance or productivity (Table 1). We acknowledge that some restoration treatments occurred after this date and some restoration projects may take years to alter habitat in a manner that benefits fish populations. For example, periods of high stream discharge may be required for LWD placements to increase complexity of stream channels, and such events may not occur immediately following restoration. Thus, our before-after approach to examining responses to restoration effects simplified a potentially extended period of changing habitat.

2.2 Population monitoring

We estimated the abundance of coho salmon at three distinct life stages. Adult abundance in both IMWs was estimated by enumerating salmon redds via spawner surveys conducted throughout the anadromous zone. Surveys covered the known spawning distribution approximately weekly.

For the sake of consistency and simplicity, we used the total annual count of unique redds as our index of spawning abundance. In the Lower Columbia streams, these redd counts correlated very closely with estimates of total spawners (Pearson r: Abernathy = 0.98, Germany = 0.98, Mill = 0.92) accounting for sex ratio (estimated at 48%) and observable redds per female (0.43, 95% confidence interval 0.39-0.48) calculated by Buehrens (2024). In Big Beef Creek, we used a census count of female abundance obtained from a channel spanning weir. In Little Anderson Creek, the smallest watershed in our study, our surveys detected zero redds in 2008, 2018, 2020, and 2022. In these years, we modified redd counts to one, thereby allowing the stock-recruit analysis (avoided divide by zero).

No coho salmon hatchery programs were located in any the seven study streams. Buehrens (2024) estimated the 2010 – 2022 annual median proportion hatchery-origin spawners (i.e., strays) in the Lower Columbia streams at 12%. Representative of the Hood Canal streams, in Big Beef Creek, hatchery-origin strays composed 5% (annual median, 2003 - 2022) of the age-3 adults returning to the channel spanning weir. Hatchery-origin strays were removed from the Big Beef population at the weir, but we had no such means to remove strays from the other creeks in the study.

Summer juvenile parr abundance was estimated by mark-recapture. In each stream, coho salmon parr were captured at 10 to 25 spatially balanced sites sampled by electrofishing or seining in late July to early August (Hood Canal) or August to September (Lower Columbia). Juvenile coho salmon were marked with either an adipose fin clip (Hood Canal) or PIT tag (Lower Columbia). Marks were interrogated at smolt traps the following spring. To estimate the population abundance of parr at the time of sampling (), Equation 1 used a Petersen estimator with a Chapman modification (Seber, 1982):

where m is the number of marked parr, s is the number of smolts examined for marks, r is the number of marked smolts. We were unable to make parr estimates in Little Anderson Creek for the coho salmon cohorts spawned in 2018, 2020 and 2021 due to insufficient recaptures.

In Hood Canal, smolts were captured by channel spanning weirs, providing a census count of smolt abundance. In Lower Columbia, smolts were captured by rotary screw trap, and mark-recapture techniques estimated smolt abundance (Volkhardt et al., 2007). Additional details on monitoring methods are available in study plans and prior reports from both IMW complexes (Anderson et al., 2015; Kinsel et al., 2009; Zimmerman M. et al., 2015).

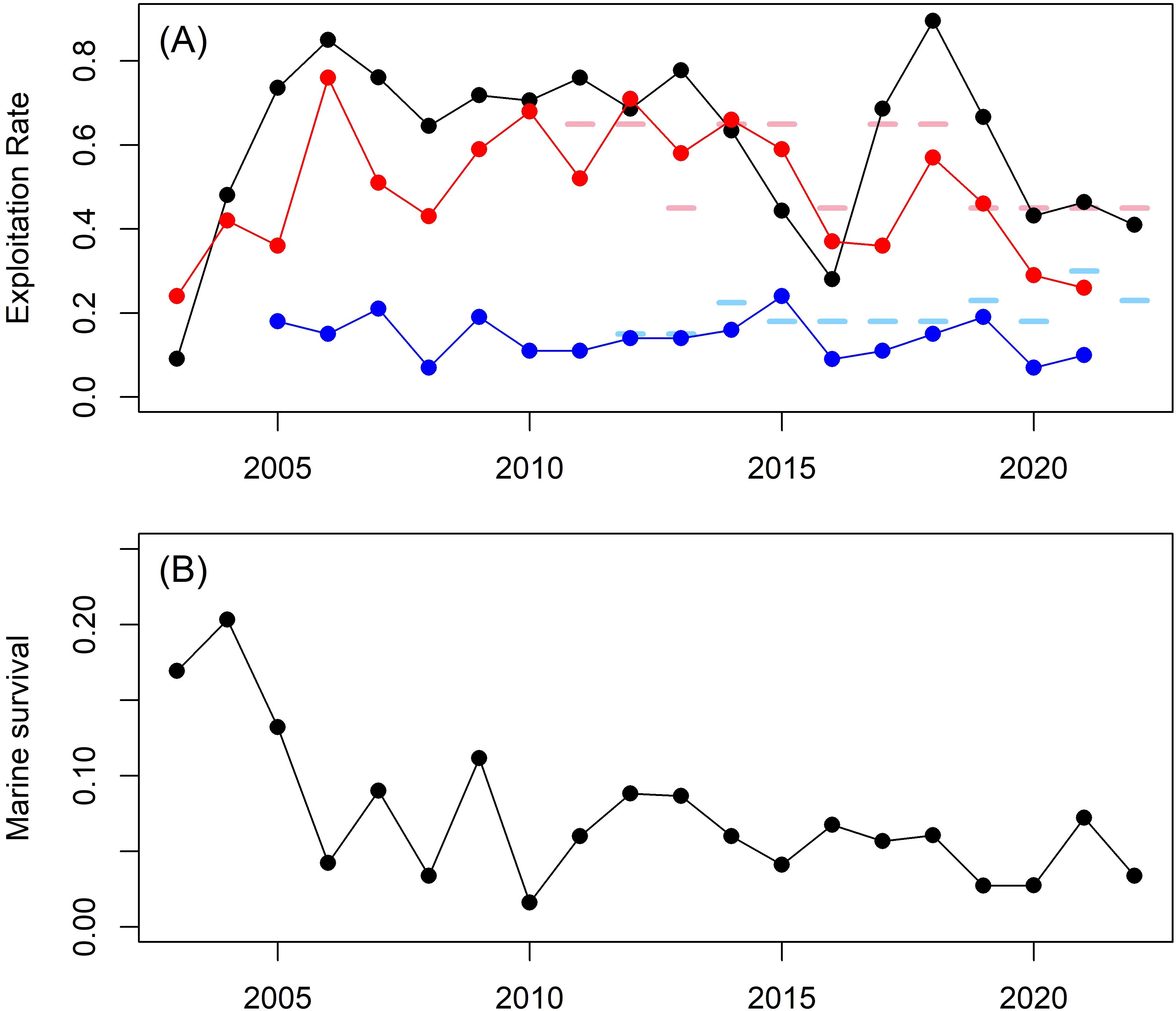

Our study populations were exposed to coho salmon fisheries managed at the spatial scale of the Hood Canal and Lower Columbia regions, respectively. We obtained estimates of wild coho salmon total exploitation rates in these management aggregates from the Pacific Salmon Commission Coho Technical Committee’s post-season Backward Fishery Regulatory Assessment Model (FRAM) analysis (PFMC, 2025; M. Litz, unpublished Feb 14 2023). FRAM uses estimated catch from mixed stock fisheries, coded wire tag (CWT) recoveries, and escapements across multiple years to evaluate fishery impacts for populations spanning the west coast of North America. We also obtained pre-season harvest management ceilings, or maximum target total exploitation rates, from annual pre-season Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) planning reports (e.g., PFMC, 2021).

At a much finer spatial scale, we also estimated annual fishery exploitation rates and marine survival of coho salmon in Big Beef Creek by implanting CWTs in smolts as they entered Hood Canal. Adults were subsequently sampled for CWT in coastwide fisheries and at the Big Beef adult weir. Big Beef CWT data are publicly accessible at www.rmpc.org. Precocial, age-2 male jacks, which represented 6% (annual median) of aggregated recoveries from fisheries and escapement across the 2002-2021 smolt cohorts, were excluded from analysis. Marine survival (Equation 2) was calcluated as:

where E is the age-3 escapement (number of CWT counted at the Big Beef Creek weir), H is the number of age-3 tags estimated from all fisheries, and T is the total number of smolts tagged from a given cohort. Exploitation rate (Equation 3) was calculated as:

2.3 Stock-recruit analysis

We examined patterns of density dependence using the Ricker model, a stock-recruit model commonly used to assess fish productivity. This approach compares the abundance at one life stage (S, stock) to abundance at a subsequent life stage (R, recruit). In its simplest form, the base Ricker model (Equation 4) estimates both intrinsic productivity (b0, ratio of recruit abundance to stock abundance) under a scenario of no density dependence, and the rate at which productivity declines with increasing stock size (b1, density dependence):

We fit all Ricker models using ordinary least squares linear regression. Our analysis had three components.

2.3.1 Test for density dependence and estimate its strength

First, to test for overall patterns of density dependent productivity, within each stream, we compared the Ricker model (Equation 4) to a density independent model (Equation 5):

Model comparisons were made using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), with ΔAIC > 2 for the density independent model providing strong support for density dependence in a given stream-life stage combination (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). Additionally, for each year t, we calculated the predicted annual strength of density dependence (Equation 6) as the proportional deviation from the intrinsic productivity line accounting for density dependence, as predicted by the Ricker model (Equation 4) at the observed stock abundance St (Figure 2A):

Figure 2. Conceptual diagram of stock-recruit curve, demonstrating (A) method for estimating the strength of density dependence (DD), where the dashed line represents intrinsic productivity parameter b0 and (B) areas of weak and strong density dependence, where the dotted line represents RMAX.

This calculation was performed separately for each watershed using the best fit Ricker model (Equation 4), yielding a time series vector of estimates, with each value corresponding to a single year. Visual inspection of the resulting Ricker stock-recruit curves provided an additional means of assessing the annual variation in the strength of density dependence. Observations on the linear portion of the curve near the origin indicate weak density dependence, whereas observations at or near the maximum number of recruits (RMAX) indicate stronger density dependence (Figure 2B).

2.3.2 Restoration effect

Second, we tested for response to restoration by examining whether there was evidence for changes in intrinsic productivity and density dependence before versus after restoration. In order to control for regionally shared environmental factors affecting interannual variation in freshwater productivity, we added residuals from the base Ricker fit in the reference watershed (C) as a control predictor (Equation 7). This model, assuming no restoration effect (Equation 7), was compared to three models that described restoration treatment (T) effects A) on intrinsic productivity (Equation 8), B) on the strength of density dependence (Equation 9); or C) on both intrinsic productivity and the strength of density dependence (Equation 10):

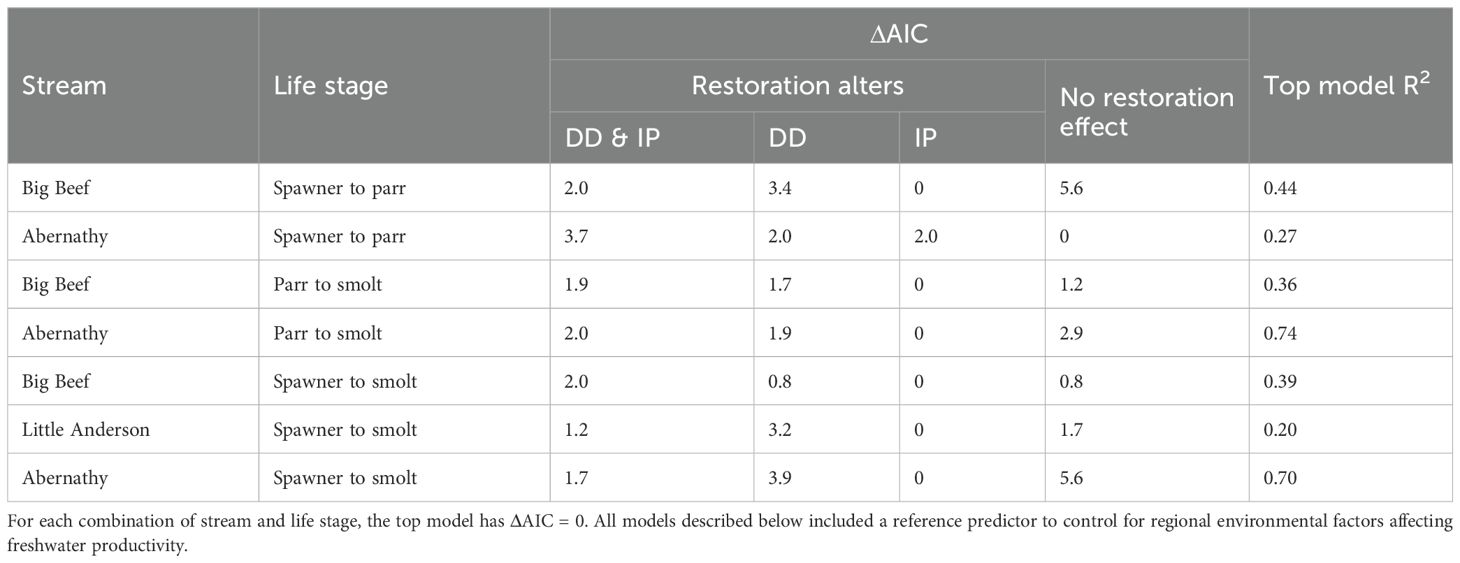

where T is a time series dummy variable that changes from 0 to 1 in the first year of the period after restoration (Table 1). To avoid overfitting, we only tested for a restoration effect in watershed-life stage combinations with at least six years of “after restoration” observations. Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was used to rank models and to infer the importance of intrinsic productivity, density dependence, and restoration treatment effect on stock-recruit relationships. We considered AIC score differences (Δ AIC)<2.0 among models to suggest equal informational value, or similar support (Burnham and Anderson, 2002).

2.3.3 Visualize ability to detect changes following restoration

Finally, in order to visualize our ability to detect changes in the stock-recruit curve attributable to restoration, we compared base Ricker fits from the before restoration period to two different hypothetical curves. The first hypothetical scenario was a 30% increase in density independent intrinsic productivity, but the maximum number of recruits (RMAX) was held constant. The second scenario was a 30% increase in RMAX but intrinsic productivity was held constant, indicative of an increase in habitat capacity following restoration. We calculated 90% confidence intervals from the standard error of the base Ricker fits to the observed data prior to restoration, and then applied the same standard error estimates to create 90% confidence intervals around the hypothetical curves. This approach assumed similar process and observation error before vs. after restoration. We inferred that comparisons with more separation between the confidence bands of the before vs. hypothetical after restoration curves presented a greater opportunity to detect a response to restoration than curves with more overlap. Under this approach, cases where either A) the Ricker model did not fit the observed recruit data well (lots of noise), or B) ranges of stock (x-axis) abundance with few observations, would tend to produce wider confidence bands, and hence reduce the ability to detect a restoration response.

3 Results

Overall, there was strong support for the Ricker density dependent model over the density independent model. Of the 21 combinations of stream and life stage, the Ricker model outperformed the density independent model in 19 comparisons with a ΔAIC of ≥ 2.0 (Table 3). Furthermore, the relatively simple Ricker models often explained a large portion of the variation in smolt abundance, with many R2 values exceeding 0.4 (N = 12, Table 3) or 0.3 (N = 14, Table 3).

Table 3. Tests for density dependence, via comparison of Ricker stock-recruit models across all years to a density independent model assuming constant productivity.

However, we also observed great variation in the patterns of density dependence according to location, year, and life stage. Most notable was a strong contrast in density dependence between the Hood Canal and Lower Columbia streams. In the Hood Canal streams, at all life stages, the majority of annual observations were located along the portion of the base Ricker model characterized by weak density dependence (Figures 3–5, panels A–D). The Big Beef, Seabeck, and Stavis spawner to parr (Figures 3A, C, D) and spawner to smolt (Figures 5A, C, D) curves had only one or two observations anchoring the density dependent portion of the stock-recruit curves. The Big Beef parr to smolt curve was nearly linear in appearance (Figure 4A).

Figure 3. Spawner to parr stock-recruit from Hood Canal (top row) and Lower Columbia (bottom row), within (A) Big Beef, (B) Seabeck, (C) Little Anderson, (D) Stavis, (E) Abernathy, (F) Germany, and (G) Mill creeks. The solid black line represents the base Ricker model fit to all years. Filled symbols represent years before restoration, open symbols represent years after restoration. Solid gray (before restoration) and dashed gray (after restoration) shown for those streams where a restoration effect model was supported based on AIC (see Table 4). Spawner values represent females counted at the weir in Big Beef Creek, and total annual redd count in all other streams.

Figure 4. Parr to smolt stock-recruit from Hood Canal (top row) and Lower Columbia (bottom row), within (A) Big Beef, (B) Seabeck, (C) Little Anderson, (D) Stavis, (E) Abernathy, (F) Germany, and (G) Mill creeks. The solid black line represents the base Ricker model fit to all years. Filled symbols represent years before restoration, open symbols represent years after restoration. Solid gray (before restoration) and dashed gray (after restoration) shown for those streams where a restoration effect model was supported based on AIC (see Table 4).

Figure 5. Spawner to smolt stock- from Hood Canal (top row) and Lower Columbia (bottom row), within (A) Big Beef, (B) Seabeck, (C) Little Anderson, (D) Stavis, (E) Abernathy, (F) Germany, and (G) Mill creeks. The solid black line represents the base Ricker model fit to all years. Filled symbols represent years before restoration, open symbols represent years after restoration. Solid gray (before restoration) and dashed gray (after restoration) shown for those streams where a restoration effect model was supported based on AIC (see Table 4). Spawner values represent females counted at the weir in Big Beef Creek, and total annual redd count in all other streams.

By contrast, observations in the Lower Columbia watersheds were more often located along the curvilinear portion of the Ricker model characterized by density-dependent reductions in productivity (Figures 3–5, panels E–G). As a result, the annual predictions of the strength of density dependence were greater in Lower Columbia than Hood Canal at all three life stage transitions (Figure 6). The exception was the Little Anderson parr to smolt estimates in the Hood Canal, which were comparable in strength to the Lower Columbia estimates.

Figure 6. Predicted annual strength of density dependence (according to Figure 2A), in the (A) spawner to parr, (B) parr to smolt, and (C) spawner to smolt life stages.

In the Lower Columbia complex, we found evidence for increases in coho salmon productivity after restoration in Abernathy Creek, which appeared to be related to density dependence during the parr to smolt stage. In Abernathy Creek, at both the spawner to smolt and parr to smolt life stages, the top model included a restoration effect for intrinsic productivity, and fit the data better than the base Ricker model assuming no restoration effect (ΔAIC > 2, Figures 4E, 5E; Table 4). By contrast, at the spawner to parr life stage, the top model did not include a restoration effect (Table 4), and the observations after restoration spanned the range of total parr abundance (Figure 3E, y-axis). Furthermore, the Abernathy parr to smolt Ricker models performed much better than the Abernathy spawner to parr models based on R2 (Tables 3; Figures 3E, 4E). The same appeared to be true in Germany Creek (Table 3; Figures 3F, 4F), though we were unable to test for a restoration effect due to the short duration of the post-treatment period.

Table 4. Tests for restoration effect, based on support for models that alter intrinsic productivity (IP) and density dependent (DD) parameters of the Ricker stock-recruit curve.

In Hood Canal, neither Big Beef nor Little Anderson creeks provided support for a restoration effect. Although the Big Beef spawner to parr model with a restoration effect performed better than the base Ricker model (ΔAIC > 2, Table 4), it contradicted the expected direction of a restoration effect, with lower productivity predicted after restoration (Figure 3A). Notably, all of the spawner to parr observations after restoration occurred at low spawner values, near the origin of the Ricker curve (Figure 3A). For the Big Beef parr to smolt, Big Beef spawner to smolt, and Little Anderson spawner to smolt analyses, the no restoration effect model yielded ΔAIC< 2 relative to the top model including a restoration effect. However, for Big Beef parr to smolt, all of the observations after restoration were on or above the base Ricker curve, suggesting increases in parr to smolt survival following floodplain reconnection and LWD placement not yet detectable by our analytical method (Figure 4A).

For each stream, the hypothetical scenario depicting a 30% increase in RMAX showed a greater separation from the pre-restoration base Ricker curve than the scenario depicting a 30% increase in intrinsic productivity (Figure 7). Furthermore, this separation was most apparent at spawner values that approached or exceeded those yielding RMAX. Among streams, Abernathy and Germany creeks appeared to show the best potential for detecting a response to restoration, as the predicted curve for the 30% RMAX increase scenario exceeded the 90% confidence interval for the pre-restoration base Ricker near values of RMAX (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Hypothetical spawner to smolt restoration stock-recruit curves in Big Beef (A, B), Little Anderson (C, D), Seabeck (E, F), Abernathy (G, H), and Germany (I, J) creeks. The black solid line with gray 90% confidence bands represents the base Ricker fit from the before restoration period. The red dashed line with red 90% confidence bands represents a hypothetical 30% increase in intrinsic productivity (left column, A, C, E, G, I). The blue dashed lines with blue 90% confidence bands represents or a 30% increase in the maximum number of recruits (right column, B, D, F, H, J). Values along the x-axis represent females counted at the weir in Big Beef Creek, and total annual redd count in all other streams.

The abundance of spawners was affected by factors occurring during the marine phase of the life cycle. In all years, coho salmon in Hood Canal experienced higher exploitation rates (median = 51%) than the Lower Columbia region (median = 14%, Figure 8A). However, in most years, these exploitation rates were less than the target, pre-season management ceilings in both Hood Canal (7 of 11 years) and Lower Columbia (9 of 10 years, Figure 8A). Of note, our estimates of exploitation rates experienced by Big Beef coho salmon (median = 68%) were higher than those for the entire Hood Canal management unit in 14 of 19 years (Figure 8A). Estimates of coho salmon marine survival from Big Beef Creek were higher earlier in the time series (2003 – 2009 median = 11.2%) than later in the time series (2010 – 2022 median = 6.0%), with three highest values observed from 2003-2005 at the outset of the IMW study (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Estimates of wild coho salmon exploitation rate (A) from the Hood Canal region (red), the Lower Columbia region (blue) and Big Beef Creek (black). The horizontal bars represent pre-season exploitation rate management target ceilings for Hood Canal (pink) and Lower Columbia (light blue). Estimated marine survival of Big Beef Creek coho salmon (B).

4 Discussion

In this paper, we explored how initial population abundance affected our ability to observe a measurable increase in salmon abundance following restoration. In particular, we examined the strength of density dependence as a factor influencing restoration response. Our evaluation of stock-recruit curves in the Hood Canal and Lower Columbia IMWs revealed strong support for density dependent processes in the freshwater phase of the life cycle, similar to previous assessments (ISAB, 2015; Walters et al., 2013). However, the strength of density dependence exhibited substantial variation across streams, through time, and to a lesser extent, across life stages.

These results argue for evaluating the response to restoration in a density dependent context by comparing stock-recruit curves across restoration scenarios. In some years and locations, populations were limited by adult abundance such that restoration might improve freshwater survival, but increases in smolt abundance were unlikely. Conversely, in other years and locations, populations were capacity limited such that restoration might increase smolt abundance, but freshwater survival would be most closely dictated by adult abundance. As a result, considering only abundance at a single life stage, irrespective of the relationship between abundance at consecutive life stages, may conflate biological processes limiting abundance across years, such as the relative influence of variation in marine survival (Welch et al., 2020; Zimmerman M. S. et al., 2015) compared to freshwater habitat factors (Sharma and Hilborn, 2001; Solazzi et al., 2000). This uncertainty, in turn, would impede an ability to detect a response to restoration.

Furthermore, a combination of observed data and examination of hypothetical increases in productivity indicated that detecting a response to restoration is more likely when density dependence is consistently strong than when it is weak. The comparison of the Hood Canal and Lower Columbia IMWs highlighted this conclusion. These two locations had a roughly similar restoration timeline and utilized similar restoration techniques but experienced strikingly different patterns of density dependence. In Hood Canal, we observed many years with relatively weak density dependence, and only a few years with strong density dependence. In Lower Columbia, most years had stronger density dependence than Hood Canal, and spawner values were in the range of those needed to produce RMAX.

Abernathy Creek in the Lower Columbia IMW revealed evidence for increases in productivity and capacity soon after restoration, whereas Big Beef and Little Anderson creeks in Hood Canal did not. Differences in the magnitude and extent of restoration between the two IMWs may have contributed to these results. Notably, LWD placements in Abernathy Creek covered a larger spatial extent and included more than ten times as many log jams as either Big Beef or Little Anderson creeks (Table 2). In other words, the comparison of Hood Canal and Lower Columbia was not a perfectly controlled experiment, owing to the watershed-level spatial scale of the study. However, the difference in abundance relative to density dependent constraints was striking. Furthermore, the strong density dependence common to the Lower Columbia IMW appeared to improve the likelihood of observing a response to restoration in the hypothetical curves.

We therefore infer that the potential response of salmon to habitat restoration will be higher in magnitude, and hence detectable on shorter time scales, when density dependence is consistently strong than when it is weak. For cases such as the Big Beef Creek, if restoration has improved salmon habitat conditions, additional years of monitoring may be needed to detect increases in either abundance or productivity. Additional observations will better estimate natural variation, reducing the minimum detectable difference from a power analysis perspective. Furthermore, additional years of data may increase the range of observed spawner values after restoration, providing important information on the relationship between abundance and productivity at higher spawner values.

In Abernathy Creek, the restoration effect and release from density dependence appeared stronger at the parr to smolt stage than the spawner to parr stage. Furthermore, the notably better fits of the Abernathy parr to smolt, compared to spawner to parr, models suggested stronger density dependent controls on productivity at the parr to smolt stage. By contrast, research on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) has shown strong density dependence controls on population abundance at younger life stages owing to the limited mobility of recently emerged fry (Finstad et al., 2010). Factors external to our population-scale abundance models, such as reach-scale density dependence (Atlas et al., 2015) or interannual variation in stream flow (Smoker, 1955), may have imparted greater influence on spawner to parr survival than parr to smolt survival. Regardless of the precise mechanism, comparing our results to Finstad et al. (2010) suggests that the specific life stage and ecological mechanisms controlling juvenile or smolt abundance are likely to be context (e.g., stream, species) dependent.

We hypothesize that Abernathy smolt abundance was limited by overwinter rearing habitat. Indeed, overwinter habitat features were targeted in the Abernathy restoration plan based on fish monitoring results from the initial years of study. Additional rearing capacity afforded by restoration may have increased parr to smolt survival, or allowed more parr to overwinter within Abernathy Creek, rather than emigrate in the summer or fall at age-0. Juvenile coho salmon frequently move into tributaries, ponds, alcoves and other seasonal, off-channel habitats for rearing during winter, which may confer survival advantages and ultimately govern total smolt abundance (Ebersole et al., 2006; Nickelson et al., 1992; Peterson, 1982; Solazzi et al., 2000).

Tests for restoration response in Big Beef and Little Anderson highlighted potential pitfalls of examining restoration response in low abundance populations. In Big Beef, all years after restoration experienced weak density dependence, and as a result, there was little information to guide model fitting on the strength of density dependence and shape of the curve at higher spawner values. In Little Anderson, low abundance increased both observation and process error. Parr abundance was so low we could not estimate it in three of the seven years after restoration. Furthermore, chance events imparted a large impact on abundance estimates in Little Anderson Creek (e.g., Routledge and Irvine, 1999), as a combination of low water conditions, roadway constrictions on the floodplain, and beaver activity appeared to limit access to upper reaches of the watershed in recent years.

4.1 Management applications

Our study both reinforces emerging messages from IMW research and provides some new insights into planning, managing and monitoring habitat restoration actions designed to improve salmon population status.

These results emphasize the critical importance of a multi-faceted, “all-H” approach to salmon recovery (sensu HSRG, 2014). Recovery plans often emphasize the need to coordinate actions addressing four primary factors affecting salmon population viability – harvest, hatcheries, habitat and hydropower (NMFS, 2006, 2013). Indeed, restoration cannot be effective if it does not address the primary constraints on abundance (Bisson et al., 2024). A significant difference in harvest rates between the two IMWs contributed to observed differences in the strength of density dependence. In Hood Canal, reducing harvest would be a more direct route to increasing smolt abundance in our study streams than restoring freshwater habitat. Our results also highlight issues of spatial scale in planning salmon recovery actions (Good et al., 2007). At the watershed scale, our study goal was to validate restoration as a tool towards increasing coho salmon abundance. However, in a broader context, there was no coordinated regional effort beyond our study streams to increase coho salmon abundance, at least in part because the species was not listed under the U.S. ESA. Indeed, Hood Canal harvest managers were actually quite successful at achieving pre-season target exploitation rates.

Our results imply a potential conflict between traditional fisheries management approaches that aim to optimize population productivity versus observing a response to restoration. Maximum sustainable yield concepts are common throughout Pacific salmon management (Pacific Fishery Management Council, 2024), including coho salmon fisheries in Hood Canal and Puget Sound (Bowhay and Patillo, 2009; PSTT and WDFW, 1998). In targeting maximum sustainable yield benchmarks, fisheries managers use harvest to reduce abundance to a level that maximizes the harvestable surplus, defined as the number of spawners in excess of those needed for population replacement (Ricker, 1975). This approach prioritizes productivity (recruits per spawner) over maximum total recruitment by weakening density dependence. However, our results suggest that large spawner abundances that maximize smolt abundance, to the point of habitat inefficiency and hence lowering productivity, increase the likelihood of detecting a salmon response to restoration.

Our study provides an empirical example for managing expectations regarding the response of salmon to habitat restoration projects. Bilby et al. (2023) emphasized the difficulty of identifying limiting factors, and suggested restoration often fails to address the factors constraining salmon abundance. Our study puts a finer nuance on that point by showing that factors limiting abundance can change over time, even within the same watershed. In Hood Canal, even a set of watersheds identified for restoration proved to be rarely limited by habitat capacity. In cases where spawner abundances rarely reach capacity constraints, observing changes in productivity may require much larger magnitude restoration than occurred in Big Beef or Little Anderson creeks. Furthermore, despite an initial positive response to culvert replacement in Little Anderson Creek (Anderson et al., 2019), the increased smolt abundance was not sustained in subsequent years.

We emphasized freshwater capacity in evaluating restoration effectiveness, yet this is not the only means by which restoration can benefit salmon populations. Improving other population attributes such as growth, spatial distribution, or life history diversity may confer increased resilience or higher survival in the marine phase (Atlas et al., 2015; Bennett et al., 2015; Holtby et al., 1990), but were outside the scope of our analysis. Furthermore, even if increased survival under weak density dependence is more difficult to detect than higher smolt capacity (c.f., Big Beef parr to smolt, Abernathy parr to smolt), higher productivity at low abundance may ultimately provide equally important benefits, such as higher fishery yields under MSY management and resilience to periods of low marine survival.

We suggest a better understanding of how specific restoration techniques affect density dependent capacity limits versus density independent intrinsic productivity would aid the return on investment in restoration. In other words, does a proposed restoration project increase the total number of juvenile salmon that can rear in a stream? Or does it increase the survival prospects of juvenile salmon, regardless of their total abundance? Or both? Even density independent events affecting survival may have a density dependent component, adding to the difficulty of separating these two hypotheses. For example, displacement and mortality due to flooding is a density independent event, but limitations on off-channel habitats providing refugia from high discharge (e.g., Solazzi et al., 2000) may create a negative relationship between abundance and survival.

In conclusion, we provide evidence for increased smolt abundance following restoration in a watershed characterized by consistently strong density dependence. We argue that the strongest, fastest response to restoration will occur when restoration alleviates density-dependent constraints on populations that regularly reach spawning levels required to maximize smolt abundance. Our study also highlights the influence of factors occurring outside the watershed, such as harvest. Overall, to the extent practicable, management strategies that test juvenile capacity limits by saturating the spawning grounds with adults give the greatest opportunity to observe the increases in salmon abundance that motivate stream restoration efforts throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. All fish capture and handling activities were permitted by NOAA Fisheries under section 4d of the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA). The permitting process included an annual review of detailed protocols and adherence to NOAA Fisheries guidelines. Regarding authority within Washington State, Revised Code of Washington 77.12.071 permits WDFW employees to capture fish from state waters during work activities.

Author contributions

JA: Supervision, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. JL: Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. CK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. ML: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Financial support for this study was provided by the Washington State Salmon Recovery Funding Board and the Washington State General Fund.

Acknowledgments

We remember three technicians that made substantial contributions to the Hood Canal IMW but passed away during the course of the study. Mathew Gillum was the backbone of fish monitoring at Big Beef Creek for 28 years, providing consistency, solving the inevitable problems and adding an infectious passion for fish to our team. Bret Steck’s positive attitude and enthusiasm for smolt and habitat monitoring helped make long field days fun. Mary Valentine spent the summer of 2023 conducting habitat surveys in the Big Beef, Little Anderson, Seabeck, and Stavis creeks, and lost her life working a fish trap on the Duckabush River January 23, 2024. Robert Bilby, William Ehinger, Timothy Quinn, Greg Volkhardt, Mara Zimmerman, Kirk Krueger, Mike McHenry and George Pess had an instrumental role in development of the IMW concept and study plan. We thank Mendy Harlow, Sarah Heerhartz, Gus Johnson and others at the Hood Canal Salmon Enhancement Group for sponsoring, implementing and describing restoration in the Hood Canal streams. Steve Manlow, Steve West, and Amelia Johnson at the Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board provided substantial support for the Lower Columbia IMW study. Eli Asher, formerly Cowlitz Indian Tribe, led implementation of restoration work in the Lower Columbia IMW, with additional help from the Cowlitz County Conservation District. Parr surveys would not have been possible without Jason Walter, Rene Tarosky and Travis Schill (Weyerhaeuser Company), with additional support from WDFW and WA Department of Ecology technicians. Eric Kummerow, Morgan Kroeger, Andrew Simmons and numerous additional WDFW technicians spent long hours counting fish in the Hood Canal streams, often in inclement weather. Similarly, we thank Pat Hanratty, Trevor Johnson, Brad Allen, Jacob Hearron, Drew Nielsen, and numerous additional WDFW staff for monitoring fish populations in the Lower Columbia IMW.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson J. H., Krueger K. L., Kinsel C., Ehinger W. J., Quinn T., and Bilby R. (2019). Coho salmon and habitat response to restoration in a small stream. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 148, 1024–1038. doi: 10.1002/tafs.10196

Anderson J., Kruger K., Ehinger W., Heerhartz S., Kinsel C., Quinn T., et al. (2015). Hood Canal Intensively Monitored Watershed Study Plan. (Olympia, WA: Report submitted to Washington State Salmon Recovery Funding Board Monitoring Panel).

Atlas W. I., Buehrens T. W., McCubbing D. J. F., Bison R., and Moore J. W. (2015). Implications of spatial contraction for density dependence and conservation in a depressed population of anadromous fish. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 72, 1682–1693. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2014-0532

Barnas K. A., Katz S. L., Hamm D. E., Diaz M. C., and Jordan C. E. (2015). Is habitat restoration targeting relevant ecological needs for endangered species? Using Pacific Salmon as a case study. Ecosphere 6, 110. doi: 10.1890/ES14-00466.1

Beechie T., Imaki H., Greene J., Wade A., Wu H., Pess G., et al. (2013). Restoring salmon habitat for a changing climate. River Res. Appl. 29, 939–960. doi: 10.1002/rra.2590

Bennett T. R., Roni P., Denton K., McHenry M., and Moses R. (2015). Nomads no more: early juvenile coho salmon migrants contribute to the adult return. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 24, 264–275. doi: 10.1111/eff.12144

Bilby R. E., Currens K. P., Fresh K. L., Booth D. B., Fuerstenberg R. R., and Lucchetti G. L. (2023). Why aren't salmon responding to habitat restoration in the Pacific Northwest? Fisheries 49, 16–27. doi: 10.1002/fsh.10991

Bisson P., Hillman T., Beechie T., and Pess G. (2024). Managing expectations from Intensively Monitored Watershed studies. Fisheries 49, 8–15. doi: 10.1002/fsh.10992

Bowhay C. and Patillo P. (2009). Letter to Chuck Tracy, Staff Officer for Pacific Fishery Management Council. (Portland, OR: Pacific Fishery Management Council Briefing Books).

Buehrens T. W. (2024). Using integrated models to improve management of imperiled salmon and steelhead (Seattle, WA: University of Washington).

Burnham K. P. and Anderson D. R. (2002). Model selection multi-model inference: a practical information-theoretic approach (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag).

Copeland T., Blythe D., Schoby W., Felts E., and Murphy P. (2020). Population effect of a large-scale stream restoration effort on Chinook salmon in the Pahsimeroi River, Idaho. River Res. Appl. 37, 100–110. doi: 10.1002/rra.3748

Ebersole J. L., Wigington P. J., Baker J. P., Cairns M. A., Church M. R., Hansen B. P., et al. (2006). Juvenile coho salmon growth and survival across stream network seasonal habitats. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 135, 1681–1697. doi: 10.1577/T05-144.1

Finstad A. G., Einum S., Sættem L. M., and Hellen B. A. (2010). Spatial distribution of Atlantic salmon (Salmon salar) breeders: among- and within-river variation and predicted consequences for offspring habitat availability. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 67, 1993–2001. doi: 10.1139/F10-122

Good T. P., Beechie T. J., McElhany P., McClure M. M., and Ruckelshaus M. H. (2007). Recovery planning for Endangered Species Act-listed Pacific salmon: using science to inform goals and strategies. Fisheries 32, 426–440. doi: 10.1577/1548-8446(2007)32[426:RPFESL]2.0.CO;2

Greene C. M., Beamer E. M., Munsch S. H., Chamberlin J. W., LeMoine M. T., and Anderson J. H. (2025). Population responses of Chinook salmon to two decades of restoration of estuary nursery habitat. Front. Mar. Sci. 12, 1584913. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1584913

Hatchery Scientific Review Group (HSRG) (2014). On the science of hatcheries: an updated perspective on the role of hatcheries in salmon and steelhead management in the Pacific Northwest.

Holtby L. B., Andersen B. C., and Kadowaki R. K. (1990). Importance of smolt size and early ocean growth to interannual variability in marine survival of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 47, 2181–2194. doi: 10.1139/f90-243

Independent Scientific Advisory Board (ISAB) (2015). Density dependence and its implications for fish management and restoration programs in the Columbia River Basin. Report number 2015-1.

Jacobs G. R., Thurow R. F., Petrosky C. E., Osenberg C. W., and Wenger S. J. (2024). Life-cycle modeling reveals high recovery potential of at-risk wild Chinook salmon via improved migrant survival. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 81, 297–310. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2023-0167

Jaeger W. K. and Scheuerell M. D. (2023). Return(s) on investment: restoration spending in the Columbia River Basin and increased abundance of salmon and steelhead. PloS One 18, e0289246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289246

Jorgensen J. C., Nicol C., Fogel C., and Beechie T. J. (2021). Identifying the potential of anadromous salmonid habitat restoration with life cycle models. PloS One 16, e0256792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256792

Katz S. L., Barnas K., Hicks R., Cowen J., and Jenkinson R. (2007). Freshwater habitat restoration actions in the Pacific Northwest: a decade's investment in habitat improvement. Restor. Ecol. 15, 494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2007.00245.x

Kinsel C., Hanratty P., Zimmerman M., Glaser B., Gray S., Hillson T., et al. (2009). Intensively Monitored Watersheds: 2008 fish population studies in the Hood Canal and Lower Columbia stream complexes (Olympia, WA).

National Marine Fisheries Service (2006). Final supplement to the Shared Strategy's Puget Sound salmon recovery plan (Seattle, WA: National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Region).

National Marine Fisheries Service (2013). ESA Recovery Plan for Lower Columbia River coho salmon, Lower Columbia River, Chinook salmon, Columbia River Chum salmon, and Lower Columbia River steelhead. (National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Region).

Nickelson T. E., Rodgers J. D., Johnson S. L., and Solazzi M. F. (1992). Seasonal changes in habitat use by juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) in Oregon coastal streams. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 49, 783–789. doi: 10.1139/f92-088

Pacific Fishery Management Council (2024). Pacific Coast Salmon Fishery Managment Plan (Portland, OR).

Peterson N. P. (1982). Immigration of juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) into riverine ponds. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 39, 1308–1310. doi: 10.1139/f82-173

Puget Sound Treaty Tribes and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (1998). Comprehensive Coho Management Plan.

Ricker W. E. (1975). Computation and interpretation of biological statistics of fish populations (Ottawa, ON: Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada), 191.

Roni P., Beechie T. J., Bilby R. E., Leonetti F. E., Pollock M. M., and Pess G. R. (2002). A review of stream restoration techniques and a hierarchical strategy for prioritizing restoration in Pacific Northwest watersheds. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage 22, 1–20. doi: 10.1577/1548-8675(2002)022<0001:AROSRT>2.0.CO;2

Roni P., Beechie T., Pess G., Hanson K., and Jonsson B. (2015). Wood placement in river restoration: fact, fiction, and future direction. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 72, 466–478. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2014-0344

Roni P., Hanson K., and Beechie T. (2008). Global review of the physical and biological effectiveness of stream habitat rehabilitation techniques. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage 28, 856–890. doi: 10.1577/M06-169.1

Routledge R. D. and Irvine J. R. (1999). Chance fluctuations and the survival of small salmon stocks. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, 1512–1519. doi: 10.1139/f99-093

Scheuerell M. D., Hilborn R., Ruckelshaus M. H., Bartz K. K., Lagueux K. M., Haas A. D., et al. (2006). The Shiraz model: a tool for incorporating anthropogenic effects and fish–habitat relationships in conservation planning. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 63, 1596–1607. doi: 10.1139/f06-056

Seber J. A. F. (1982). The estimation of animal abundance and related parameters (Caldwell, NJ: The Blackburn Press).

Sharma R. and Hilborn R. (2001). Empirical relationships between watershed characteristics and coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) smolt abundance in 14 western Washington streams. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 58, 1453–1463. doi: 10.1139/f01-091

Smoker W. A. (1955). Effects of stream flow on silver salmon production in western Washington (Seattle, WA: University of Washington).

Solazzi M. F., Nickelson T. E., Johnson S. L., and Rodgers J. D. (2000). Effects of increasing winter rearing habitat on abundance of salmonids in two coastal Oregon streams. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 57, 906–914. doi: 10.1139/f00-030

Volkhardt G. C., Johnson S. L., Miller B. A., Nickelson T. E., and Seiler D. E. (2007). “Rotary screw traps and inclined plane screen traps,” in Salmonid field protocols handbook: techniques for assessing status and trends in salmon and trout populations. Eds. Johnson D. H., Shrier B. M., O'Neal J. S., Knutzen J. A., Augerot X., O'Neil T. A., and Pearsons T. N. (American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD), 235–266.

Walters A. W., Copeland T., and Venditti D. A. (2013). The density dilemma: limitations on juvenile production in threatened salmon populations. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 22, 508–519. doi: 10.1111/eff.12046

Welch D. W., Porter A. D., and Rechisky E. L. (2020). A synthesis of the coast-wide decline in survival of West Coast Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha,Salmonidae). Fish Fisheries 22, 194–211. doi: 10.1111/faf.12514

Zimmerman M. S., Irvine J. R., O’Neill M., Anderson J. H., Greene C. M., Weinheimer J., et al. (2015). Spatial and temporal patterns in smolt survival of wild and hatchery coho salmon in the Salish Sea. Mar. Coastal Fish. Dynamics Manage. Ecosystem Sci. 7, 116–134. doi: 10.1080/19425120.2015.1012246

Keywords: restoration, salmon, Endangered Species Act, streams and rivers, conservation, fisheries management

Citation: Anderson JH, Lamperth JS, Kinsel CW and Litz MNC (2025) Patterns of density dependence affect coho salmon population response to restoration. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1691164. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1691164

Received: 22 August 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025; Revised: 13 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Peter Bisson, Retired, Olympia, WA, United StatesReviewed by:

Tracy Hillman, BioAnalysts, Inc., United StatesAilene Ettinger, The Nature Conservancy, United States

Copyright © 2025 Anderson, Lamperth, Kinsel and Litz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joseph H. Anderson, am9zZXBoLmFuZGVyc29uQGRmdy53YS5nb3Y=

Joseph H. Anderson

Joseph H. Anderson James S. Lamperth

James S. Lamperth Clayton W. Kinsel

Clayton W. Kinsel Marisa N. C. Litz

Marisa N. C. Litz