- 1State Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Water Security in River Basin, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Water Safety for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region of Ministry of Water Resources, Beijing, China

- 3Yellow River Conservancy Technical University, Kaifeng, China

- 4Department of Water Ecology and Environment, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, China

- 5Hebei Water Conservancy Engineering Bureau Group Limited, Shijiazhuang, China

Understanding how biological traits and functional diversity of riverine communities respond to environmental factors across different ecoregions is vital for biodiversity conservation and river restoration. This study investigated macroinvertebrates from mountain and lowland rivers in Beijing to compare 33 biological trait categories and six functional diversity indices between these ecoregions. We applied an integrated approach combining environmental variable matrix (R), species community matrix (L), and biological trait matrix (Q) (RLQ) and fourth-corner analyses to link macroinvertebrate traits with hydrological, physical, and chemical factors. Furthermore, generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to compare the responses of traits and functional diversity to multiscale environmental variables and to identify sensitive indicators for ecosystem assessment. Our results showed that 28 of the 33 biological traits differed significantly between the two ecoregions. The mountain ecoregion was characterized by macroinvertebrates with traits such as semivoltine, small and medium size individuals, strong swimming ability, abundant drift, and clinger, shredder, and predator preferred habitats. In contrast, the lowland ecoregion, which experiences greater human impact, was associated with traits such as bi- or multivoltine, large-sized individuals, depositional substrate, warm eurythermal, weak swimming ability, rare drift, and collector–gatherer. All functional diversity indices except Functional Divergence were significantly higher in the mountain ecoregion, demonstrating that environmental stressors in the lowlands substantially reduced functional diversity. The RLQ and fourth-corner analyses confirmed that these biological traits exhibited predictable responses along environmental gradients. The GLM indicated that trait distribution and functional diversity in the two ecoregions were driven by different environmental variables across spatial scales. Hydrological and physical factors explained most of the variations in the mountains, whereas reach-scale chemical factors were the primary drivers of functional diversity loss in the lowlands. This study demonstrates that macroinvertebrate traits and functional diversity serve as effective indicators for river ecosystem health assessment, providing a scientific basis for targeted ecological restoration and sustainable river management.

1 Introduction

River ecosystems exhibit a typical hierarchical dendritic structure, in which the composition and function of biological communities are jointly regulated by multiscale environmental factors (Poff, 1997). Across different ecoregions, the influences of natural factors (e.g., topography, hydrology) and anthropogenic disturbance (e.g., urbanization, water conservancy projects) on macroinvertebrate communities vary significantly. Such differences often stem from heterogeneous characteristics among ecoregions (Allan, 2004). However, current river management practices often overlook ecoregion specificity, resulting in management measures that lack targeted effectiveness. This not only makes it difficult to effectively maintain or restore the unique structure and function of biological communities in different ecoregions but may even exacerbate ecosystem degradation by neglecting inter-ecoregion differences (Zhang et al., 2025; Ao et al., 2022; Maasri et al., 2021). Therefore, the response mechanisms of biological communities to environmental gradients across different ecoregions should be explored in depth. Through this, the causes of adaptive differentiation in communities can be revealed, and the reasons for the degradation of ecosystem functions can be elucidated. Subsequently, precision management strategies for river ecosystems can be advanced, which are based on ecoregional classification.

The functional traits of macroinvertebrates represent survival strategies formed through long-term adaptation to environmental pressures and can sensitively reflect both the functional diversity of communities and their response trends to environmental changes (Elliott and Quintino, 2007; Poff et al., 2006). Since ecosystems are often shaped more by the functional attributes of species than by taxonomic identity alone, quantifying functional diversity, which integrates species traits and abundances based on interspecific trait dissimilarity, provides a powerful metric for understanding ecosystem processes (Loreau et al., 2001; Pfisterer and Schmid, 2002). Compared with traditional taxonomic diversity metrics, functional traits are more capable of revealing the functional potential and stability mechanisms of ecosystems (Loreau et al., 2001; Pfisterer and Schmid, 2002; Chalcraft et al., 2004). Consequently, trait-based functional diversity not only quantifies the roles and functions of organisms in ecosystems but also provides mechanistic insights into the patterns of biodiversity (Statzner et al., 2001).

However, there remains considerable disagreement in the literature regarding the relationship between the functional traits of macroinvertebrates and environmental factors across spatial scales (Brown et al., 2018; Benítez et al., 2018). On one hand, the habitat filtering theory emphasizes that environmental conditions shape community structure by selecting for suitable traits, with particularly strong trait–environment correlations observed at the microhabitat scales. For example, a study by Lamouroux et al. (2004) at the microhabitat scale demonstrated significant correlations between the biological traits of macroinvertebrates and local environmental variables (such as flow velocity and substrate), supporting the dominant role of local environmental filtering. Furthermore, research by Brown et al. (2018) in glacial retreat streams showed that reductions in glacial coverage systematically filtered trait groups with specific cold tolerance and dispersal capacities by altering water temperature and hydrological regimes, illustrating a strong filtering effect of large-scale environmental gradients on community trait composition. In contrast, the niche complementarity hypothesis posits that communities with higher functional diversity can utilize resources more efficiently, and that the resulting community assembly patterns may be consistent across spatial scales. For instance, a study by Dolédec et al. (2011) in New Zealand rivers found relatively low variation in trait composition of macroinvertebrates among large-scale ecoregions, with changes primarily driven by broad-scale factors such as regional climate and land use, suggesting that large-scale processes may attenuate the effects of local habitat filtering. Conversely, Zuellig and Schmidt (2012), in a study of wadeable streams across the continental United States, observed that despite differences among ecoregions, the impact of land use types on functional trait composition showed remarkable consistency across ecoregions. This indicates that anthropogenic disturbances can transcend natural geographical boundaries, producing universal trait filtering patterns. These discrepancies may arise from inconsistent definitions of spatial scales, variations in the type and intensity of disturbances, and the influence of factors such as topography and geomorphology. Therefore, investigating the differential responses of macroinvertebrate functional traits to environmental gradients across different ecoregions is crucial for elucidating the scale dependency of trait–environment relationships and revealing the intrinsic mechanisms of functional degradation in biological communities under multiple stressors.

As a highly urbanized region, Beijing possesses river systems that exhibit both natural and artificial attributes. The marked differences in hydrological regimes, physical habitat structure, and human disturbance intensity between its mountainous and plain ecoregions make this area an ideal setting for investigating how multiscale environmental factors drive the functional trait differentiation of benthic macroinvertebrates (Zhang et al., 2023). Based on this context, the present study proposes the following core hypotheses: (1) Systematic differences exist in the functional trait composition and functional diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates between mountainous and plain rivers, with mountain communities expected to exhibit higher functional diversity. (2) The key environmental factors driving functional trait differentiation are ecoregion-specific, with hydromorphological factors predominating in mountainous areas and chemical pollution factors being more influential in the plains. (3) Specific functional trait sets will show predictable responses along environmental gradients—for instance, traits adapted to high flow velocities will correlate positively with mountainous conditions, while pollution-tolerant traits will associate more strongly with plain environments. To test these hypotheses, this study analyzes the functional trait composition and diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates in the region, employing statistical approaches such as combining environmental variable matrix (R), species community matrix (L), and biological trait matrix (Q) (RLQ) and fourth-corner analysis, with the objectives of (1) quantifying differences in functional traits and functional diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates among different ecoregions, (2) identifying key environmental variables influencing trait composition and functional diversity, and (3) revealing ecoregion-specific effects of environmental variables on functional traits. The findings will not only provide a scientific basis for ecological conservation and restoration of rivers in Beijing but also offer theoretical insights and methodological support for biological monitoring and ecosystem management in similar ecological regions, such as urban rivers in semi-arid areas and mountain–plain transition zones.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study area

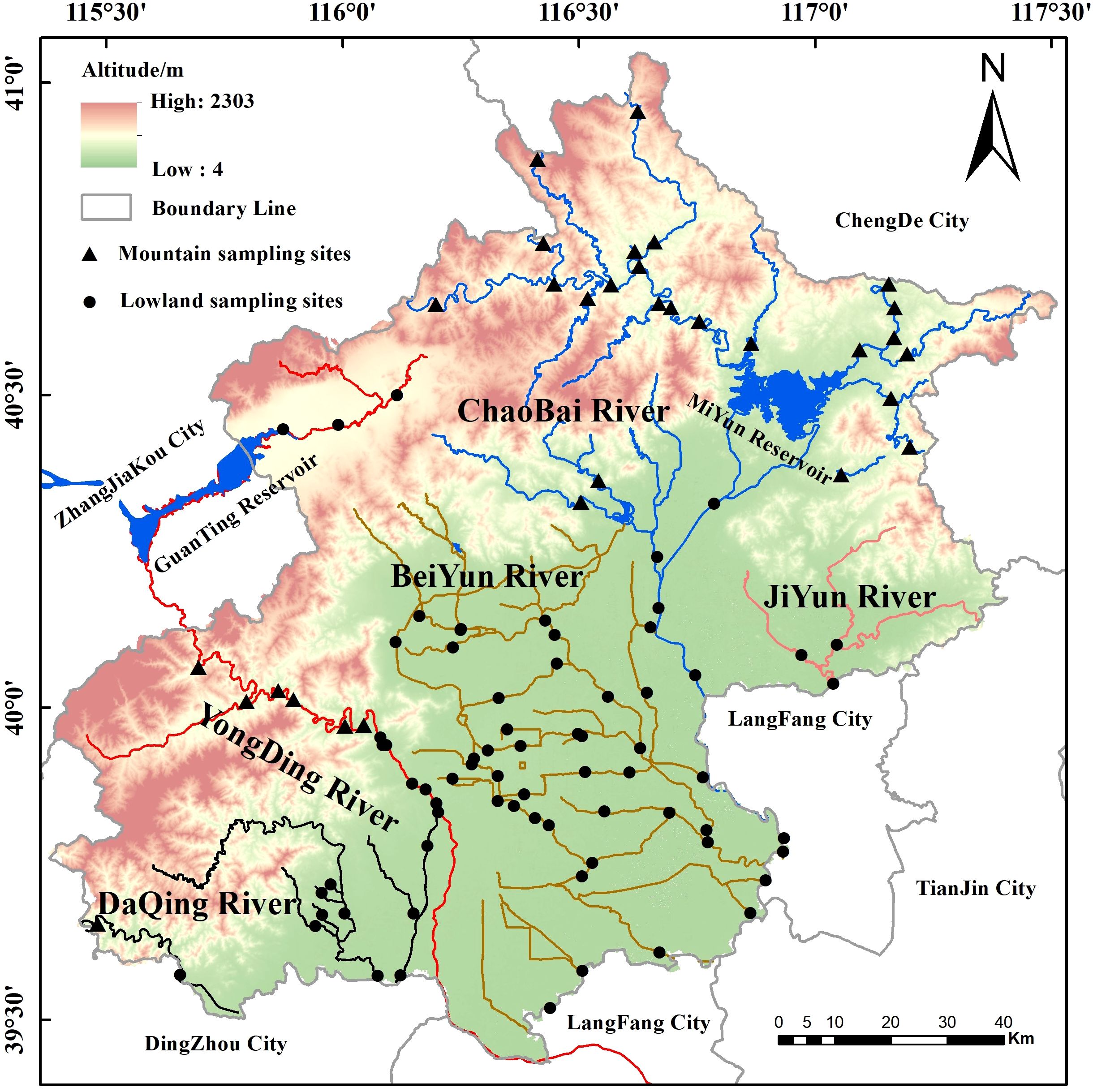

The river systems of Beijing (39.4°N–41.6°N, 115.7°E–117.4°E) comprise five major basins: the Yongding, Daqing, Chaobai, Beiyun, and Jiyun Rivers, which together form an integrated drainage network (Figure 1). The northwestern part of the municipality constitutes the mountainous ecoregion, covering an area of 9,973.4 km² (60.8% of the total area) with elevations ranging from 1,000 to 1,500 m. In contrast, the southeastern area comprises the lowland ecoregion, covering 6,342.3 km² (39.2%) at elevations of 20–60 m (Zhang et al., 2023). These lowlands slope gently from northwest to southeast, forming a gradual topographic descent. This topographical gradient causes most rivers to converge in the southeast before exiting the municipality. The Beiyun River is primarily situated within the central, highly urbanized lowlands. In contrast, the upper reaches of the other river systems are largely located in the mountainous region, with their middle and lower reaches flowing through the lowlands. The region experiences a typical semi-humid continental monsoon climate, characterized by hot, rainy summers and cold, dry winters, with a multiyear average rainfall of 576.4 mm (Zhang et al., 2018).

2.2 Field sampling

Between September 2020 and July 2021, we conducted four seasonal field surveys (spring, summer, autumn, and winter) at 101 river monitoring sites in Beijing, selected based on river system length, density, and logistical accessibility. Macroinvertebrates were collected using a Surber sampler (30 × 30 cm, 500 μm mesh). At each site, three replicate quantitative samples were collected from the three most representative benthic microhabitat types, including riffles, pools, and macrophyte-covered or other areas, to ensure a comprehensive representation of local biodiversity. The three replicates from each site were combined into a single composite sample and preserved in a 500-ml jar filled with 70% ethanol immediately upon collection. Laboratory identifications of all specimens to the genus level or lower were based on standard taxonomic references (Wiggins, 1996; Morse et al., 1984; Zhou, 2002; Environmental Protection Administration of China, 1993).

At each sampling site, we measured a suite of environmental variables encompassing hydrological, physical habitat, and water chemistry parameters. Water depth (WD, m) and flow velocity (Vel, m/s) were measured in triplicate using a digital velocity meter (Global Water flow probe FP201). Water temperature (WT, °C) and dissolved oxygen (DO, mg/L) were recorded with a multiparameter water quality probe (YSI Pro Plus).

Water samples were collected using a 1-L plexiglass water sampler, following standard protocols (The State Environmental Protection Administration, 2002). These samples were analyzed for the following parameters: permanganate index (CODMn, mg/L), chemical oxygen demand (COD, mg/L), 5-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5, mg/L), ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N, mg/L), total phosphorus (TP, mg/L), copper (Cu, mg/L), zinc (Zn, mg/L), fluoride (F-, mg/L), and mercury (Hg, mg/L).

Substrate particle size distribution was determined using a set of stainless-steel sieves according to a modified Wentworth classification system. Substrate types were categorized into seven classes based on particle diameter: boulder (>256 mm), large cobble (128–256 mm), cobble (64–128 mm), large pebble (32–64 mm), pebble (16–32 mm), large gravel (8–16 mm), and fine sediments (<8 mm, comprising small gravel, sand, and silt).

The physical habitat quality of each river was assessed using a habitat quality index (HQ) following the methodology of Zheng et al. (2007). This index comprises 10 metrics: substrate composition, stream habitat complexity, range of combined water depth and velocity, bank stability, channel sinuosity, water quantity, water cleanliness, riparian plant biodiversity, habitat environmental stress, and land use types. Each metric was scored on a scale from 0 (low quality) to 20 (high quality).

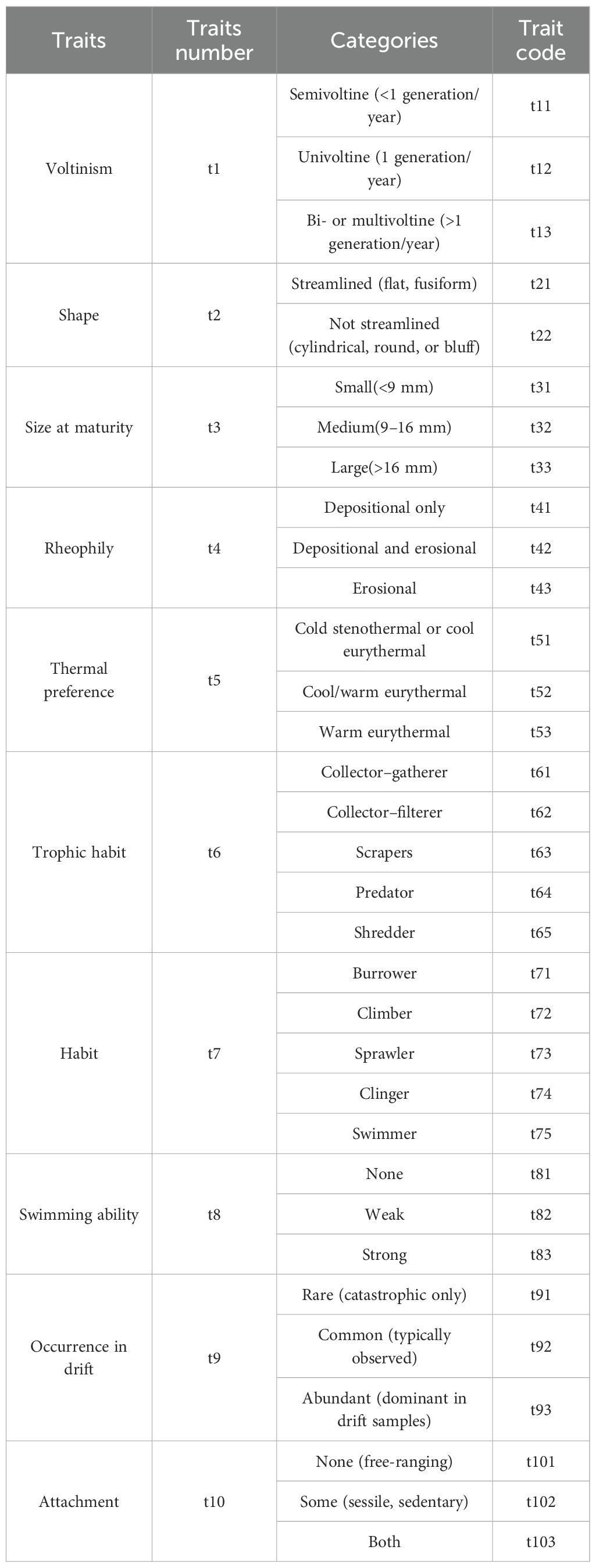

2.3 Traits and functional diversity

Ten functional traits were selected for analysis: voltinism, occurrence in drift, swimming ability, attachment ability, body shape, size at maturity, rheophily, thermal preference, habit, and trophic habit (Table 1). These traits are well established as responsive to key environmental drivers, including hydrological disturbance (e.g., flow velocity, discharge), physical habitat structure (e.g., substrate composition, habitat quality), and water quality parameters (e.g., nutrient levels, organic pollution) (Poff et al., 2006; Usseglio-Polatera et al., 2000; Brinkhurst, 1986). For instance, swimming ability and rheophily are directly associated with species adaptations to hydraulic conditions; voltinism and body size reflect life-history strategies; and trophic habits indicate pathways of material cycling and energy flow within ecosystems (Poff et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2018; Brinkhurst, 1986). Consequently, this suite of traits provides a comprehensive framework to capture the adaptive differentiation strategies of macroinvertebrate communities under distinct environmental pressures in mountainous versus lowland river systems.

Functional trait data for each taxon were primarily obtained from published regional monographs, taxonomic guides, and internationally recognized trait databases (Poff et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2018; Usseglio-Polatera et al., 2000; Tachet et al., 2002; Epler, 2001; Brinkhurst, 1986). We employed a fuzzy coding system to score the affinity of each taxon for the various categories within a trait. Each category was assigned an integer value from 0 (no affinity) to 3 (high affinity), reflecting the degree of affiliation. These raw scores for all categories under a given trait were then normalized to sum to 1, forming a probability distribution (Poff et al., 2006; Usseglio-Polatera et al., 2000; Tachet et al., 2002). For traits with ambiguous documentation or significant ontogenetic variation, a species was allowed to hold affinity for multiple categories simultaneously, with the normalized probabilities summing to 1 (Usseglio-Polatera et al., 2000; Dray and Legendre, 2008). This procedure resulted in a functional trait matrix for the macroinvertebrate community, ensuring a robust and reproducible basis for subsequent statistical analysis.

Trait and functional diversity indices were calculated based on the relative abundance of species within each trait category. Trait diversity indices included trait richness (TR) and trait diversity (TD). Functional diversity indices included functional richness (FRic), functional evenness (FEve), functional divergence (FDiv), and Rao’s quadratic entropy (RaoQ). TR represents the total number of distinct biological trait categories present at each site (Bêche and Statzner, 2009). TD quantifies the diversity of biological traits by integrating both trait category richness and their relative abundances (Larsen et al., 2011). FRic reflects the range of functional trait space filled by the macroinvertebrate community. A larger FRic value indicates occupation of a broader range of ecological niches (Cornwell et al., 2006). FEve measures the evenness of species abundance distribution within the occupied trait space. A lower FEve value suggests suboptimal utilization of available ecological niches (Mason et al., 2005). FDiv describes the degree to which species abundances are distributed toward the extremes of the trait space. A higher FDiv value indicates greater niche differentiation and reduced resource competition among species (Laliberté and Legendre, 2010). RaoQ combines species’ relative abundances with their pairwise functional differences to represent the expected functional distance between two randomly selected individuals in the community (Mouchet et al., 2010; Botta-Dukát, 2005).

2.4 Statistical analysis

The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the differences in environmental variables, trait category and species occurrence frequencies, and trait and functional diversity indices between mountain and lowland ecoregions. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) and analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) test were used to analyze the spatiotemporal distribution differences of macroinvertebrate communities. Comprehensive RLQ (R: environmental variables matrix, L: species community matrix, Q: biological trait matrix) and fourth-corner methods analyze the relationship between environmental stress, species composition, and biological traits (Dray and Legendre, 2008). The comprehensive RLQ and fourth-corner analysis helps address the limitations of each individual method. It not only considers the co-variation effects of biological traits or environmental variables but also determines the main environmental variables that affect changes in biological traits. First, permutation tests (999 permutations) were performed on fourth-corner Model 2 and Model 4. The results from both models were combined, and their p-values were re-calculated using a combined permutation procedure to control the overall Type I error rate. In the RLQ framework, the R (environment) and Q (traits) matrices are linked through the L (species abundance) matrix. Model 2 tests the null hypothesis (H1) of no association between environment (R) and species composition (L), whereas Model 4 tests the null hypothesis (H2) of no association between species composition (L) and traits (Q). The global null hypothesis (H0) for the R–Q relationship posits that there is no association between environmental variables and functional traits, which is rejected only if both H1 (Model 2) and H2 (Model 4) can be rejected. The alternative hypothesis is that a significant R–Q relationship exists. Specifically, H0 is rejected in favor of the alternative only when both Model 2 and Model 4 are simultaneously significant, with the combined significance level determined as α0=α1×α2 (Dray and Legendre, 2008).

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to fit the effects of environmental variables at different spatial scales on traits and functional diversity indices, to compare the relative importance of environmental variables in mountain and lowland ecoregions, and to use the adjusted R² to determine the combination of environmental variables with the highest explanatory power. Due to the over-dispersion present in the TR, which violates the assumptions of a normal distribution, a negative binomial distribution was used to fit the count-based variable TR, while a Gaussian distribution was applied to the remaining trait and functional diversity indices.

To address potential collinearity when assessing biological assemblage–environment relationships, we performed Pearson correlation screening (|r| ≥ 0.6) among hydrological, physical, and chemical variables. Variables with high loadings on the first two principal component analysis (PCA) axes (|scores| ≥ 0.6) were selected to represent key environmental gradients. Inter-variable correlations were further verified using supplementary Pearson tests (Wu et al., 2014; Ferreira et al., 2015). Prior to statistical analysis, species relative abundance data and all environmental variables (except pH) were log(x+1)-transformed, and all variables were standardized to eliminate scale differences. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.1.3). The “dbFD” function in the FD package was used to calculate trait and functional diversity indices; the ade4 package was employed for RLQ and fourth-corner analyses; and the vegan package was used for NMDS, ANOSIM, PCA, and Pearson correlation analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Environment variable

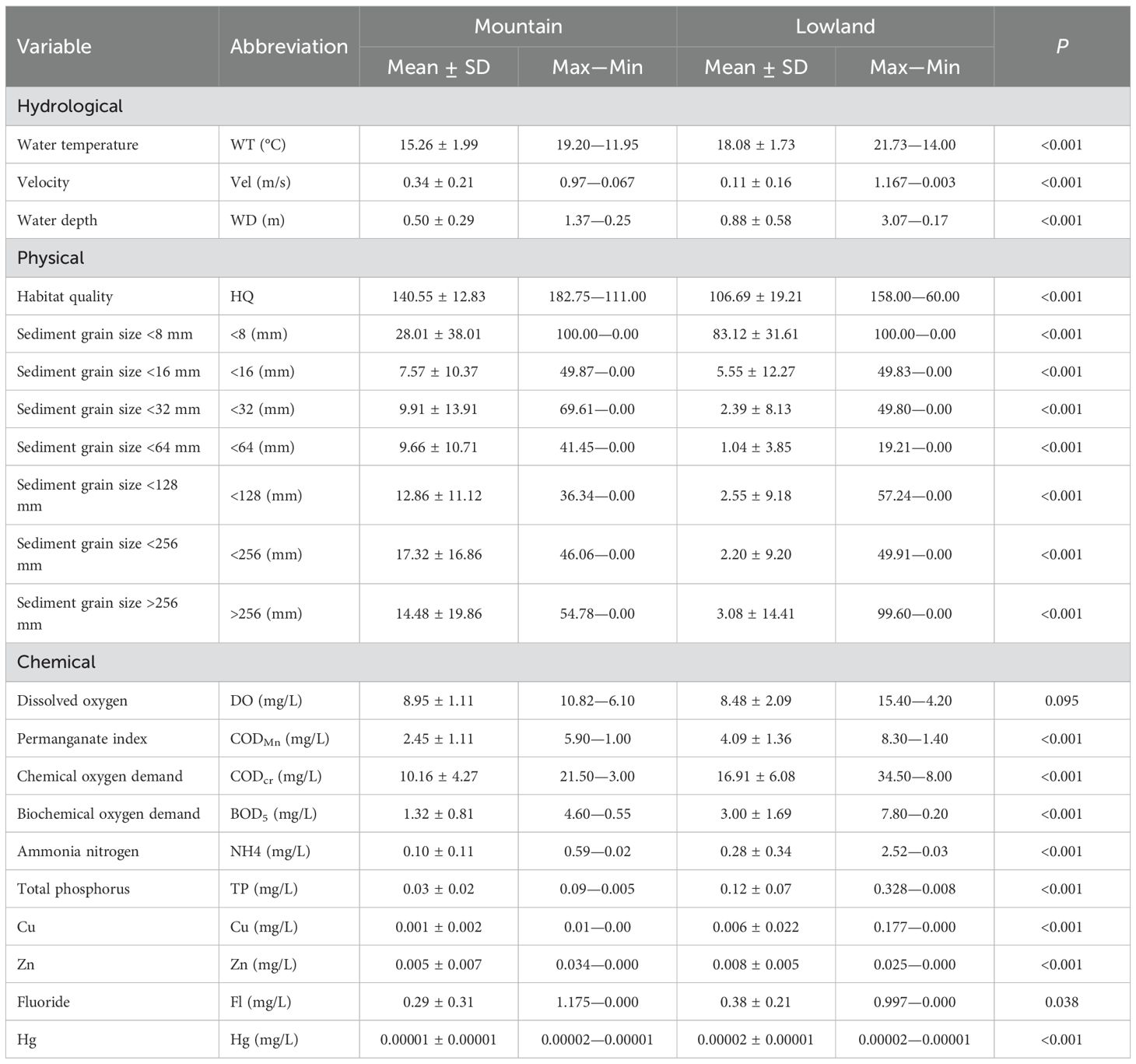

Significant differences were found in 20 environmental variables between the mountain and lowland ecoregions rivers of Beijing (P<0.05, Table 2). Among hydrological factors, the flow velocity in mountain ecoregions is significantly higher than that of lowland ecoregions, and the water temperature and water depth in lowland ecoregions are significantly higher than that of mountain ecoregions. Among the physical factors, except for the sediment particle size <8 mm in mountain ecoregions, which is significantly lower than that of lowland ecoregions, other variables are significantly higher than that of lowland ecoregions. Among chemical factors, DO has no significant difference between mountain and lowland ecoregions, and other variables are significantly higher in lowland than in mountain ecoregions.

Table 2. Summary of environmental variables among sampling sites at mountain and lowland ecoregions.

3.2 Macroinvertebrates communities, traits, and functional diversity

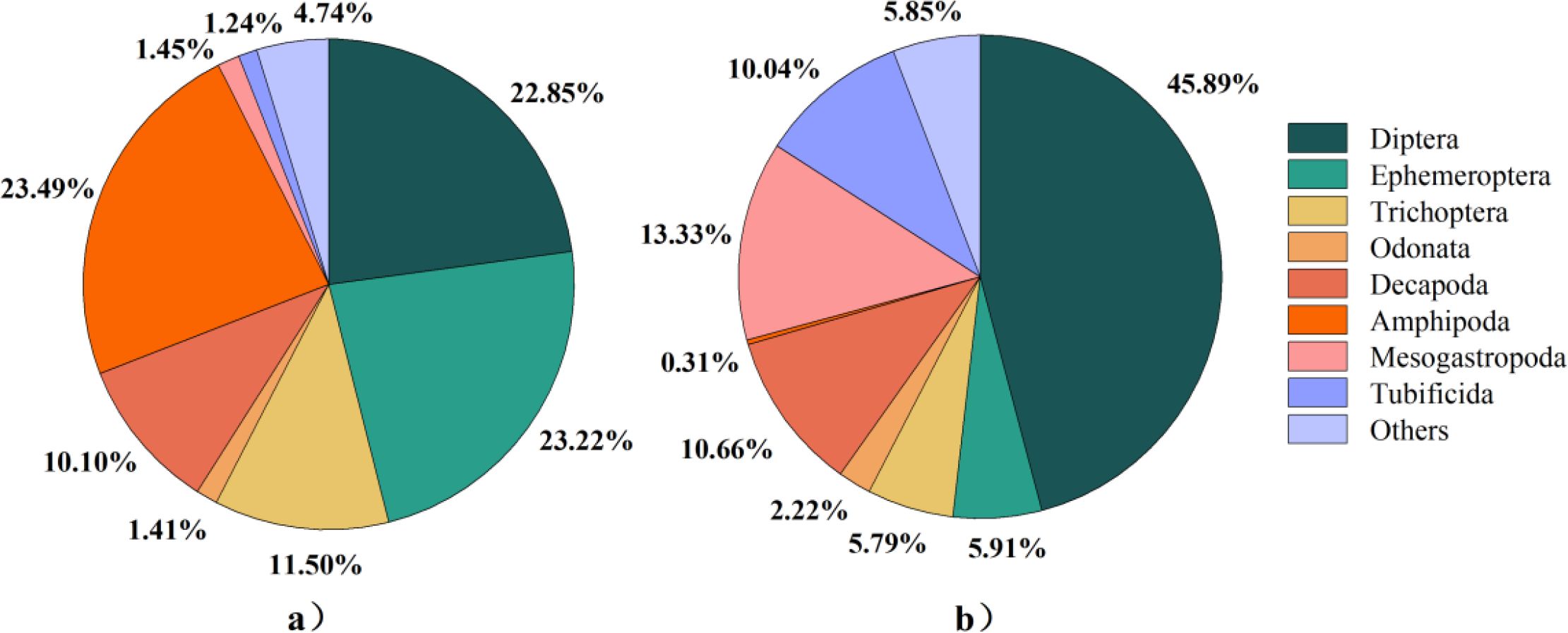

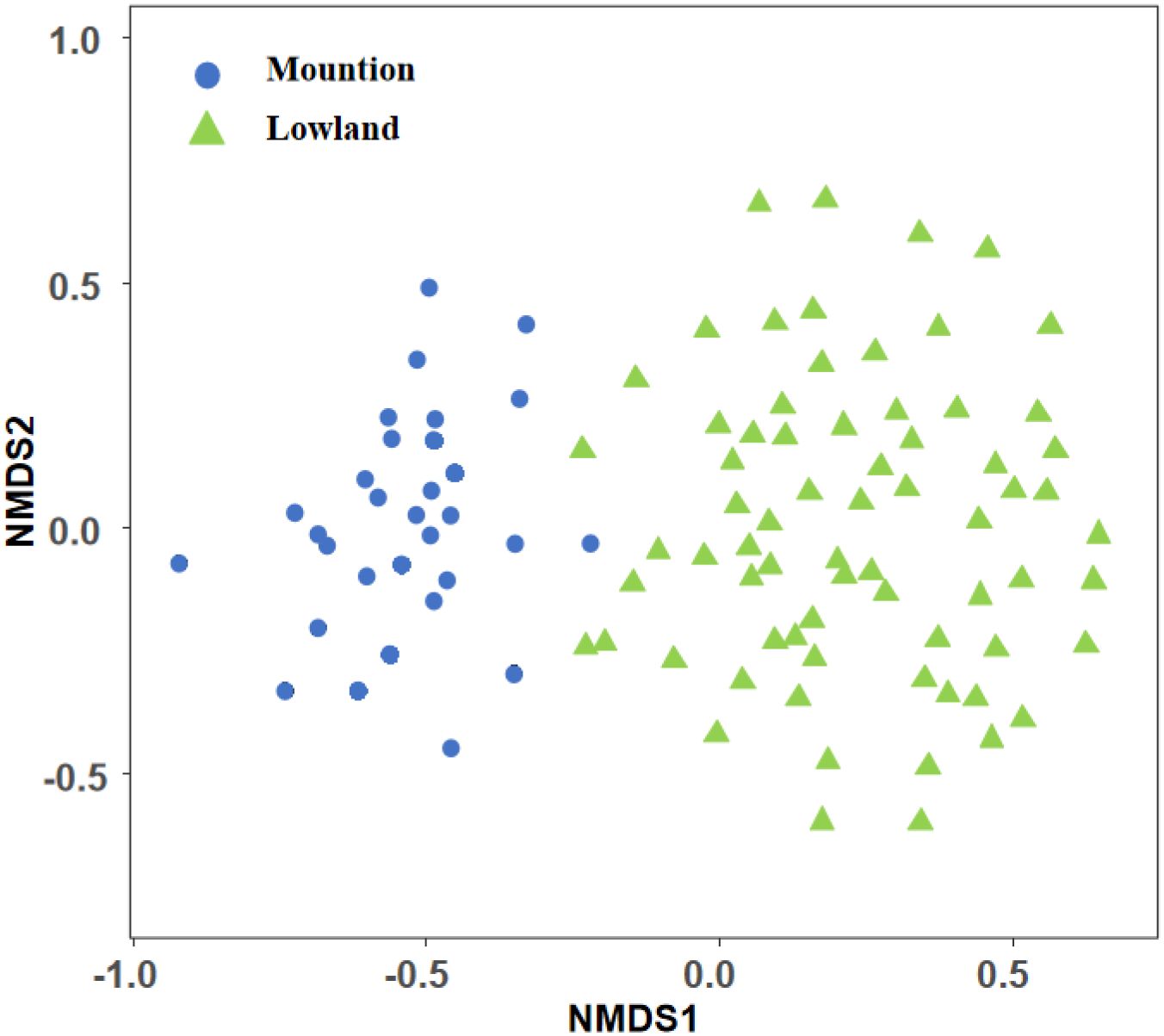

NMDS analysis showed that there was an obvious spatial distribution pattern between mountain and lowland ecoregions for macroinvertebrates in Beijing’s rivers (Figure 2). ANOSIM analysis showed that there were significant differences in the community structure of macroinvertebrates in mountain and lowland ecoregions (R = 0.73, P<0.05). A total of 271 species of macroinvertebrates were identified in Beijing’s rivers, of which 196 species were collected from mountain ecoregions, and the community was composed of Amphipoda (23.49%), Ephemeroptera (23.22%), Diptera (22.85%), and Trichoptera (11.50%) (Figure 3a), and the dominant species are Gammarus sp. (23.49%), Baetis sp. (11.01%), Macrobrachium sp. (10.01%), Hydropsyche sp. (6.66%), and Ephemera sp. (5.67%). A total of 203 species were collected from lowland ecoregions, and the community composition was dominated by Diptera (45.89%), followed by Mesogastropoda (13.33%), Decapoda (10.66%), and Tubificida (10.04%) (Figure 3b), and the dominant species are Cricotopus trifasciatus (16.01%), Macrobrachium sp. (10.21%), Bellamya purificata (7.68%), Chironomus flaviplumosus (7.09%), Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri (6.85%), and Hydropsyche sp. (5.50%).

Figure 2. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis of macroinvertebrate communities across mountain and lowland ecoregions.

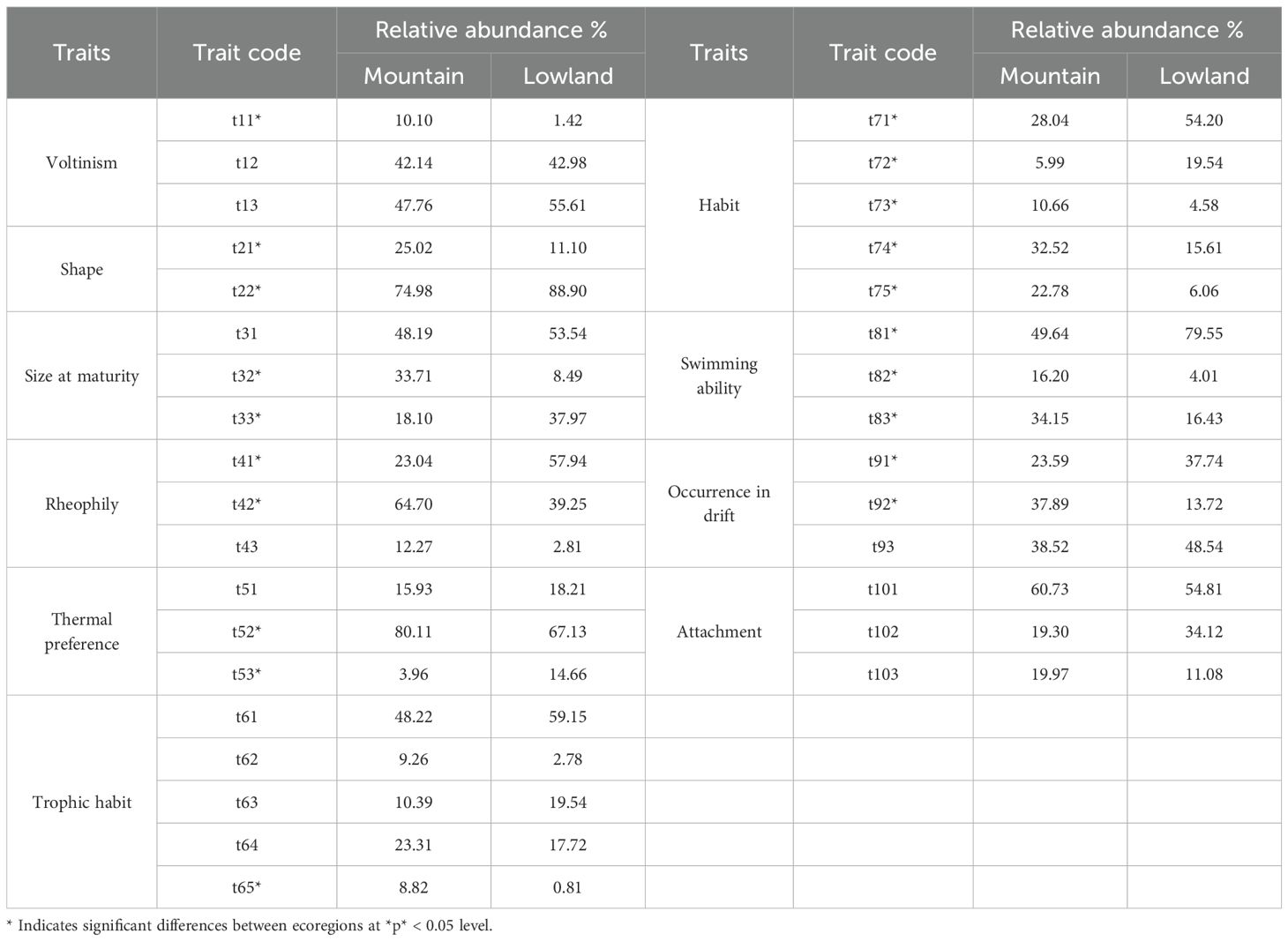

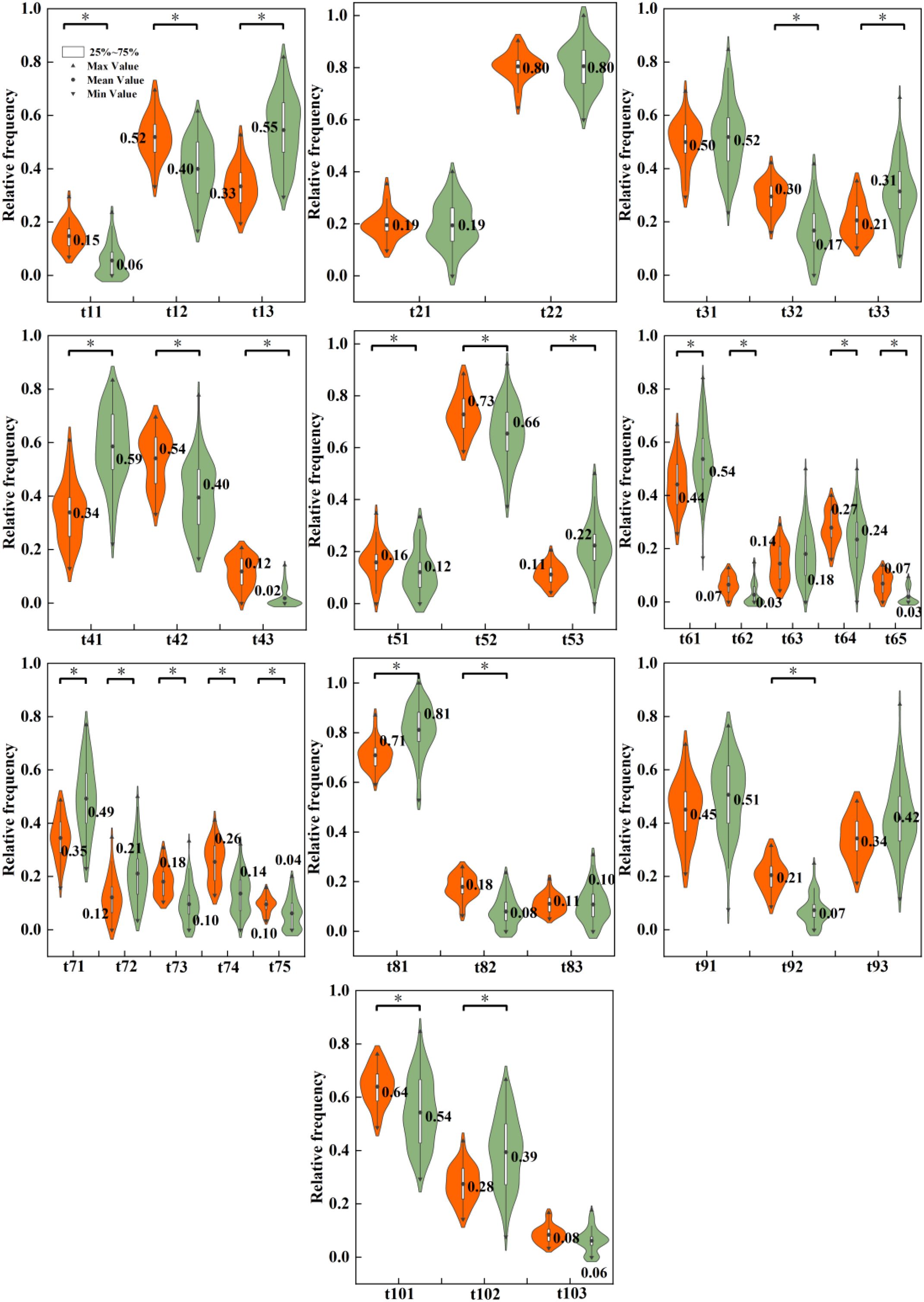

The composition of biological traits exhibited significant spatial differences between the two ecoregions (Table 3). Regarding mobility, the proportions of macroinvertebrates with strong swimming ability (t83, 34.15%), weak swimming ability (t82, 16.20%), and common drift ability (t92, 37.89%) were significantly higher in the mountain ecoregions than in the lowlands. Conversely, the proportions of those with no swimming ability (t81, 49.64%) and rare drift ability (t91, 23.59%) were significantly lower in the mountains. This pattern suggests that the higher flow velocities in mountain rivers selectively favor trait combinations associated with greater mobility, enabling organisms to maintain their position or actively migrate in swift currents. In contrast, the sluggish-flowing and lentic habitats of the lowlands are more conducive to the survival of taxa with weak mobility, which often rely on strategies like burrowing to withstand sedimentation.

In terms of habit, the proportions of clinger (t74, 32.52%), swimmer (t75, 22.78%), and sprawler (t73, 10.66%) were significantly higher in mountain ecoregions than in the lowlands. In contrast, the proportions of burrower (t71, 28.04%) and climber (t72, 5.99%) were significantly lower in the mountains. Regarding rheophily preference, the proportion of taxa preferring depositional–erosional substrates (t42, 64.70%) was significantly higher in mountain ecoregions, while the proportion of those preferring depositional substrates only (t41, 23.04%) was significantly lower compared to the lowlands. This distribution pattern results from the combined effects of hydrological conditions and substrate types. The coarse substrates in mountain rivers provide firm attachment surfaces for clingers and sprawlers, whereas the soft, sedimentary substrates in the lowlands are more suitable for burrowers. Additionally, the abundant aquatic macrophytes in the lowlands likely offer more habitat space for climbers.

In terms of size at maturity, the proportion of medium-sized individuals (t32, 33.71%) was significantly higher in the mountain ecoregions than in the lowlands, whereas the proportion of large-sized individuals (t33, 18.10%) was significantly lower. For other traits, the proportions of semivoltine (t11, 10.10%), cool/warm eurythermal (t52, 80.11%), streamlined (t21, 25.02%), and shredder (t65, 8.82%) taxa were significantly higher in the mountain ecoregions. Conversely, the proportions of non-streamlined (t22, 25.02%) and warm eurythermal (t53, 8.82%) taxa were significantly higher in the lowland ecoregions. This pattern aligns with the theory of life-history strategies under environmental stress. The unstable hydrological regime in mountains favors r-strategists, which are typically small- to medium-sized organisms with short life cycles and rapid reproductive rates. These traits facilitate rapid population recovery after disturbances. In contrast, the relatively stable conditions of the lowlands permit the survival of K-strategists, such as certain snail species, which are characterized by longer life cycles and larger body sizes.

Differential analysis of the occurrence frequency of macroinvertebrate traits between ecoregions revealed that 28 trait categories differed significantly between mountain and lowland rivers (P<0.05; Figure 4). The macroinvertebrate communities in mountain rivers were significantly enriched with trait combinations adapted to high-energy aquatic environments. These were characterized by shorter life cycles [e.g., semivoltine (t11), univoltine (t12)], medium-sized individuals (t32), a preference for depositional-erosional substrates (t42) or erosional substrate (t43), and strong mobility and attachment capabilities [e.g., clinger (t74), swimmer (t75), and common drift (t92)]. In contrast, the communities in lowland rivers were dominated by taxa with bi- or multivoltine (t13), large-sized individuals (t33), a preference for depositional substrates (t41), warm eurythermal (t53), and weak mobility [e.g., burrower (t71) and no swimming ability (t81)]. Furthermore, the relative frequency of the collector–gatherer (t61) was significantly higher in the lowlands, while the frequency of predators (t64) and shredders (t65) was significantly lower compared to the mountain regions.

Figure 4. Box plots of the relative frequency of macroinvertebrate traits at mountain and lowland sites.

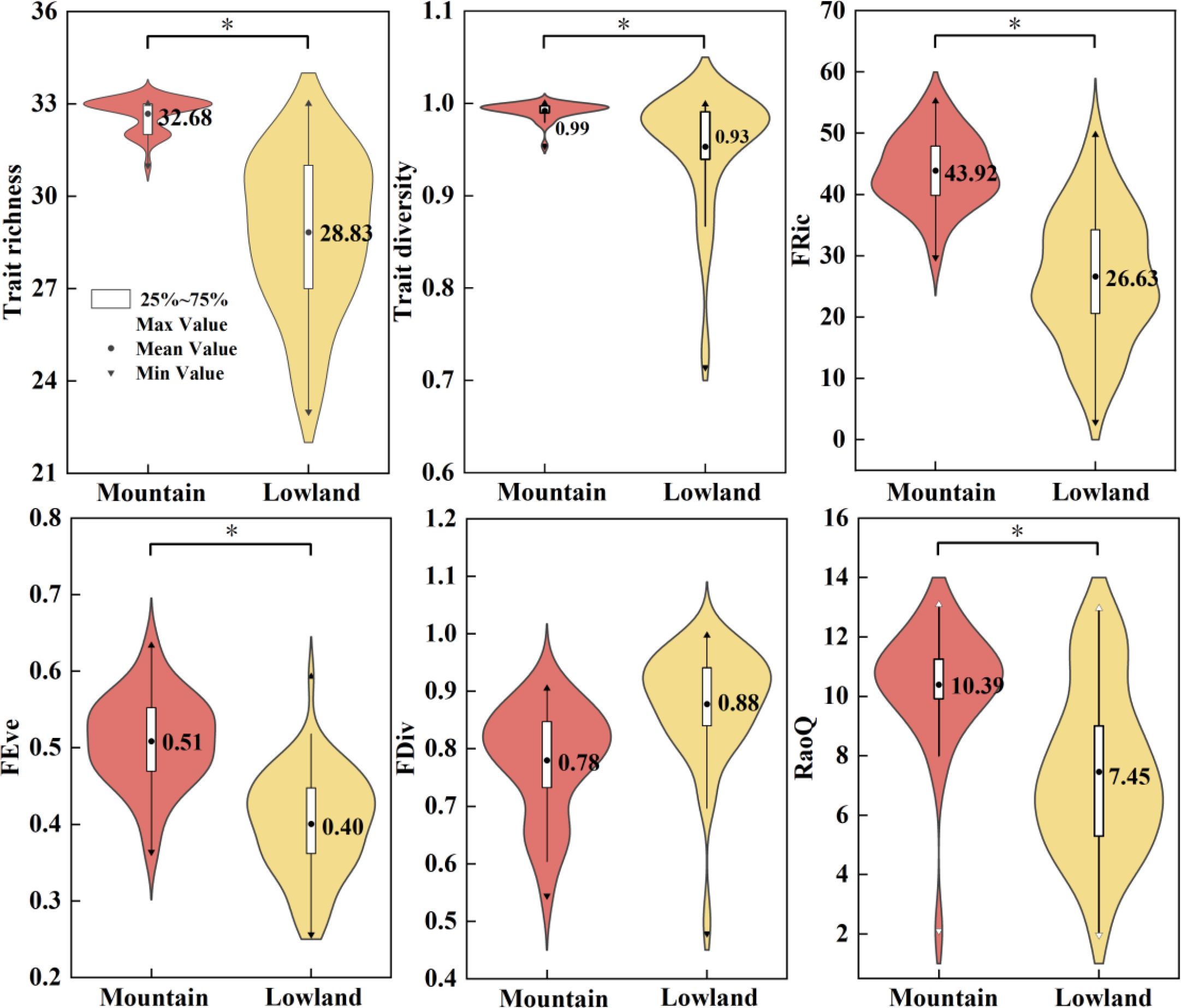

With the exception of FDiv, all other trait and functional diversity indices differed significantly between the mountain and lowland ecoregions (P < 0.05; Figure 5). Specifically, TR, TD, FRic, FEve, and RaoQ were significantly higher in the mountain ecoregions than in the lowlands. This pattern indicates that anthropogenic disturbances in the lowlands act as strong environmental filters, leading to functional homogenization and a reduction in overall community functional diversity. The lower FRic and FEve values suggest that the lowland communities have access to a narrower range of ecological niches and utilize them less evenly, implying that their ecosystem functions are more vulnerable. In contrast, the higher functional diversity in the mountains signifies more stable and resilient ecosystem functioning.

Figure 5. Box plots of trait and functional diversity distributed between mountain and lowland ecoregions.

3.3 Relationship between environmental variables and macroinvertebrates traits and functional diversity index

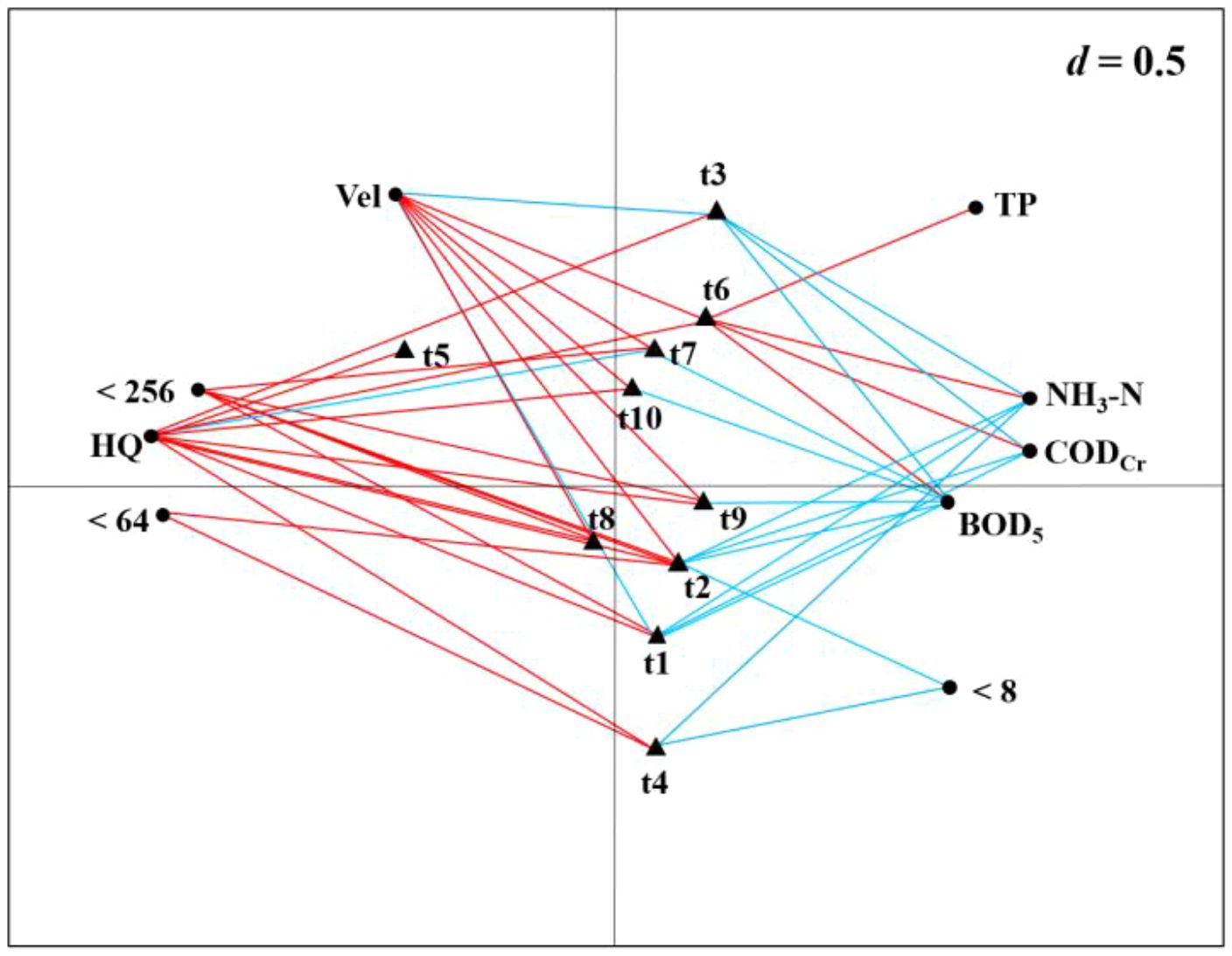

The combined RLQ and fourth-corner analyses revealed that several biological traits were significantly correlated with hydrological conditions (Figure 6). Specifically, body shape (t2), trophic habit (t6), habit (t7), swimming ability (t8), occurrence in drift (t9), and attachment ability (t10) were primarily positively correlated with flow velocity. This finding underscores the role of hydrodynamic conditions as a key habitat filter. In mountainous rapid-flow environments, these forces select for taxa possessing streamlined shapes, strong swimming capacity, high drift propensity, and effective attachment mechanisms to resist hydraulic scouring. In contrast, voltinism (t1) and size at maturity (t3) were negatively correlated with flow velocity. This confirms that unstable hydrological conditions favor r-strategist taxa, which are characterized by short life cycles and smaller body sizes. These traits enable them to rapidly recolonize habitats and recover their populations following flow disturbances.

Figure 6. Results of combining RLQ and fourth-corner analysis along the RLQ axis. R: Environmental variables; L: Species; Q: Traits. The red/blue lines represent positive/negative correlations of environmental variables and biological traits, respectively. Environmental variables and biological trait codes are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Among the physical factors, most biological traits showed a positive correlation with habitat quality, with the exception of habit (t7), which was negatively correlated. Specifically, voltinism (t1), body shape (t2), habit (t7), swimming ability (t8), occurrence in drift (t9), and a preference for sediment grain sizes <256 mm were all positively correlated with habitat quality. Furthermore, body shape (t2) and rheophily (t4) showed positive correlations with sediment grain sizes <64 mm, but negative correlations with grain sizes <8 mm. These results indicate that higher habitat quality, characterized by complex substrate composition and abundant cover, generally supports greater functional diversity. Although the negative correlation for habit (t7) may be attributed to specific taxonomic groups, the overall positive pattern strongly suggests that the complexity and stability of physical habitats form the foundation for maintaining a diverse spectrum of functional traits.

Most biological traits showed negative correlations with the measured chemical factors. Specifically, voltinism (t1), body shape (t2), size at maturity (t3), habit (t7), occurrence in drift (t9), and the water quality parameter BOD5 were all negatively correlated with overall habitat quality or other chemical variables. Furthermore, voltinism (t1), body shape (t2), and size at maturity (t3) were negatively correlated with both NH3-N and CODcr. In contrast, trophic habit (t6) showed a positive correlation with BOD5, NH3-N, CODcr, and TP. This pattern clearly illustrates the filtering effect of pollution stress: the richness of most functional traits decreases with increasing pollution, leading to functional homogenization.

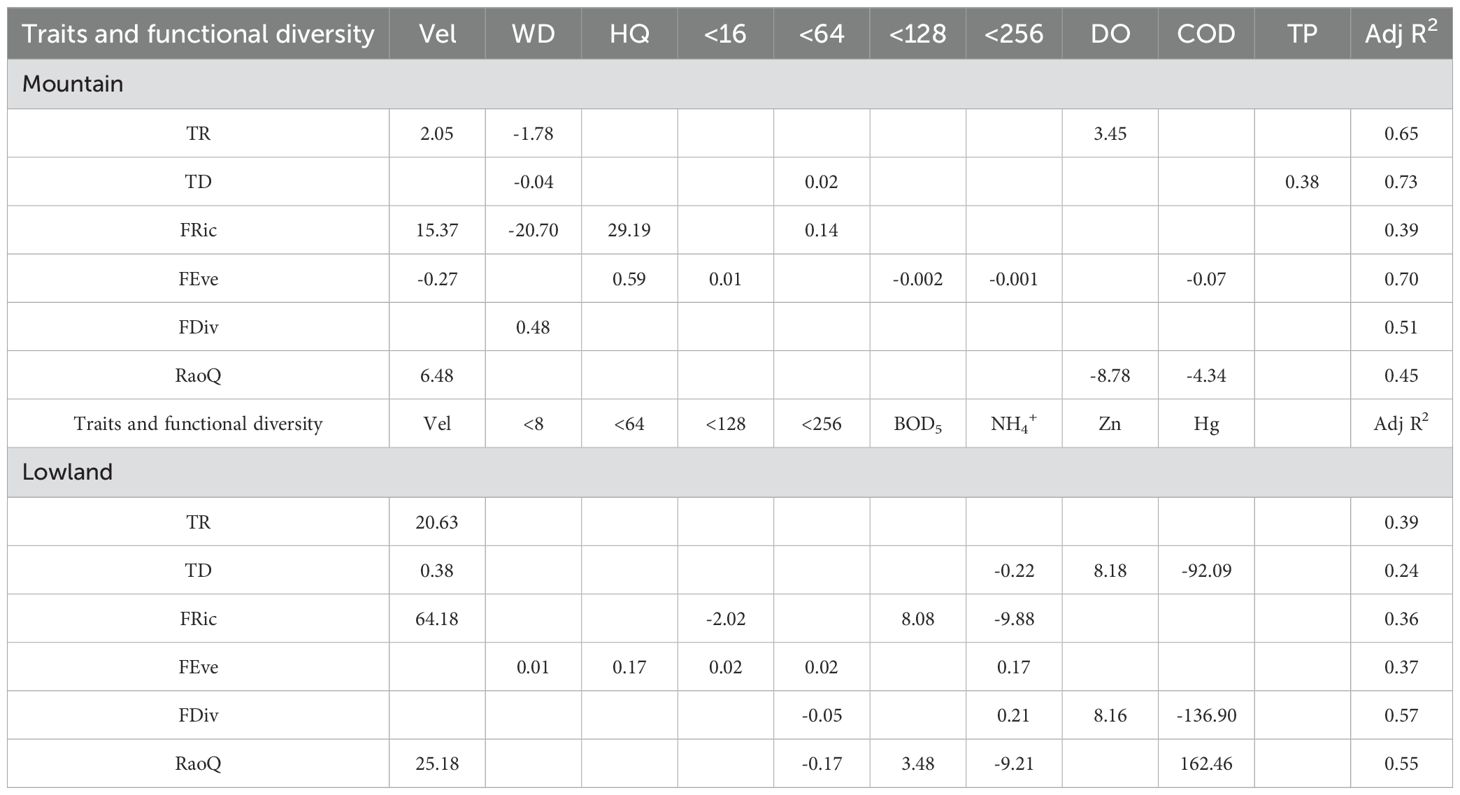

The results of the GLM (Table 4) indicated that hydrological and physical factors explained a greater proportion of the variance in trait and functional diversity indices in the mountain ecoregions than in the lowlands. In contrast, chemical factors were the most important predictors of these indices in the lowland ecoregions. This result indicates a fundamental difference in the dominant environmental drivers between the two ecoregions. In mountainous areas with minimal anthropogenic disturbance, community assembly is primarily governed by natural factors such as hydrology and physical habitat structure. Conversely, within the intensely impacted lowland regions, anthropogenic stressors, particularly water pollution, have superseded natural factors as the principal drivers shaping functional community structure. These findings underscore the necessity of implementing ecoregion-specific management strategies in river basin governance.

Table 4. Results of GLM for trait and functional diversity indices in mountain and lowland ecoregions(abbreviations are as in Table 1).

Environmental variables in the mountain ecoregions had the highest explanatory power for TD, FEve, and TR, accounting for 73.4%, 69.9%, and 64.6% of the variance, respectively. Flow velocity and water depth were the most important explanatory variables in the mountain models, each being selected in four of all the GLMs. In the lowland ecoregions, the explanatory power of environmental variables was highest for FDiv and RaoQ, yet the values were only 56.6% and 55.0%, respectively. The explained variance for TD was particularly low at only 23.8%, while for other indices, it ranged between 30% and 40%. NH3-N and flow velocity were important explanatory variables in the lowland models; NH3-N was selected in five of all GLMs, and flow velocity in four. The physical predictors, sediment grain size <8mm and <64mm, each appeared only once, specifically in the FEve model. The high explanatory power of the mountain models indicates that ecosystem functions in this region are strongly and predictably controlled by a few key natural factors. In contrast, the overall lower explanatory power of the lowland models suggests that macroinvertebrate communities in the lowlands are likely influenced by more complex and unmeasured multiple stressors. This implies that the mechanisms shaping functional patterns in the lowlands are more intricate and uncertain.

4 Discussion

4.1 Differences of macroinvertebrate traits in different ecological regions

Functional traits of organisms represent morphological, physiological, or behavioral characteristics that reflect adaptations to environmental conditions (Allan, 2004). The findings of this study strongly support the applicability of the habitat filtering theory in river ecosystems. This theory posits that environmental conditions shape community structure by selecting species with suitable traits based on their requirements for biotic and abiotic resources (Southwood, 1977). Our analysis identified 28 macroinvertebrate traits that differed significantly between mountain and lowland ecoregions—a direct manifestation of this filtering process. Specifically, the combination of higher flow velocity, favorable substrate conditions, and lower anthropogenic disturbance in mountainous areas functions as a selective “filter.” This filter favors the establishment of taxa with short life cycles, small to medium body sizes, strong swimming ability, high drift propensity, and adhesive habits, which represent effective adaptations to unstable hydrological environments (Poff, 1997). In contrast, the lowland areas, which are characterized by slow flow, depositional substrates, and high nutrient concentrations, select for taxa with long life cycles, large body sizes, weak swimming ability, burrowing habits, and collector–gatherer feeding strategies that rely on sedimentary organic matter. This systematic shift in trait composition clearly demonstrates the habitat filtering effect along an environmental gradient from natural to anthropogenically disturbed habitats, indicating that human activities can substantially alter the selective pressures that prevail under natural conditions.

Changes in key traits provide profound insights into disturbance ecology mechanisms. First, regarding mobility traits, the shift from strong swimming ability and high drift propensity in mountainous areas to weak swimming and rare drift in the lowlands reflects adaptations to distinct hydrological regimes. In mountainous rivers, species require strong mobility to cope with hydraulic stress and occupy suitable microhabitats. In contrast, in the lowlands, where hydrology is more stable but water quality is severely degraded, sedentary burrowers are better adapted to tolerate hypoxic and polluted conditions within sediments (Wise, 1980; Statzner et al., 2001).

Generally, as environmental stress increases, communities tend to shift from K-strategists, characterized by large body size, long life cycles, and low reproductive capacity, to r-strategists, characterized by small body size, short life cycles, and high recovery capacity. Smaller, short-lived organisms can recover more rapidly after disturbances (Menezes et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2018). Seasonal rainfall causes hydrological fluctuations in mountainous areas, while sluices and weirs maintain relatively stable hydrological conditions in the lowlands. This explains the greater abundance of short-lived and small-bodied taxa in the mountains. However, this pattern appears inconsistent with the chemical factor analysis, likely because larger-bodied, pollution-tolerant non-insect taxa (e.g., oligochaetes) dominate the lowland areas. Regarding trophic habits, the relative abundance of shredders is significantly higher in mountainous areas. Shredders play a key role in breaking down coarse organic debris, and their decline often indicates a disruption in the processing pathway for terrestrial organic matter inputs from riparian vegetation. In contrast, the overwhelming dominance of collector–gatherers in lowland rivers suggests that these ecosystems rely more heavily on internal fine particulate organic matter (Vannote et al., 1980), which is a typical characteristic of organic pollution and functional simplification.

4.2 Relationship between macroinvertebrate traits and environmental variables

The results of this study demonstrate that most macroinvertebrate biological traits exhibit clear responses to environmental stress. Locomotory habits, including swimming ability, attachment capacity, and drift propensity, are sensitive to variations in flow velocity (Jiang et al., 2018). In mountainous rivers, where current velocities are generally higher, taxa with strong mobility traits are better adapted to high-flow environments. In contrast, in lowland areas where flow is slower, groups with weak swimming ability become dominant, reflecting the influence of hydraulic filtering on community structure. The negative correlations observed for both voltinism and body size with flow velocity indicate that in the hydrologically unstable mountainous habitats, which are subject to seasonal rainfall disturbances, species with short life cycles and smaller body sizes can complete their life history more rapidly. This trait enhances community resilience (Menezes et al., 2010).

Habitat quality, a comprehensive indicator reflecting physical, chemical, and biological conditions (Zheng et al., 2007), showed significant associations with almost all traits. This finding further confirms the central role of habitat filtering in community assembly. For instance, body shape (t2) and rheophily (t4) were closely linked to substrate type. In the heavily disturbed lowland areas, fine-grained sediments dominate, thereby selecting for non-streamlined, burrowing-adapted taxa that can cope with substrate instability (Wise, 1980). In contrast, in the less disturbed mountainous areas, coarse gravel and cobble substrates prevail. These conditions favor species with streamlined body shapes that are adapted to erosional–depositional transition environments, reflecting morphological adaptations to flowing water conditions (Jiang et al., 2018).

Most traits showed negative correlations with chemical factors, indicating that water quality degradation acts as a selective filter for pollution-tolerant functional traits (Jiang et al., 2021). Notably, trophic habit (t6) was positively correlated with nutrient-related indicators, including BOD5, NH3–N, CODcr, and TP. As human disturbance intensifies, the accumulation of organic matter in rivers increases, which promotes the proliferation of collector–gatherer taxa that feed on sedimentary detritus. This shift establishes collector–gatherers as the dominant trophic group, reflecting the directional selection of feeding strategies under nutrient enrichment (Akamagwuna et al., 2019).

4.3 Differences of macroinvertebrate functional diversity in different ecological regions

The significant spatial variation in functional diversity reflects the response of biological traits to environmental changes and the associated functional trade-offs (Archaimbault et al., 2009; Ackerly and Cornwell, 2007; Jiang et al., 2018). This study demonstrates that functional and trait diversity indices are effective biological indicators for distinguishing disturbance gradients between mountain and lowland areas in Beijing. These indices also provide key insights into ecosystem resilience. The significantly lower functional richness (FRic) in the lowland macroinvertebrate communities, compared to that in mountainous rivers, indicates the presence of more unutilized resources and lower community productivity. Communities with low functional richness often contain vacant niche spaces, which can be readily colonized by invasive species (Bêche and Statzner, 2009; Jiang et al., 2018). Consequently, the resistance of macroinvertebrate communities in lowland rivers is lower than in mountainous regions.

The higher Rao’s Q and functional evenness (FEve) values in mountainous rivers suggest greater functional redundancy and more even resource utilization. This pattern implies that the loss of certain species could be compensated for by other species with similar traits, thereby buffering the impact of environmental fluctuations on ecosystem processes and enhancing stability. This mechanism is consistent with the redundancy hypothesis (Mason et al., 2005; Mouchet et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2018). In contrast, the lower functional redundancy and evenness in the lowlands imply that ecosystem functions are more vulnerable. The loss of key species is likely to lead to the collapse of specific ecosystem functions they perform, with limited functional compensation from other taxa (Naeem, 1998). Consequently, lowland river ecosystems may exhibit significantly lower stability and resilience in the face of future disturbances compared to mountainous rivers.

Compared with other studies, our findings reveal both commonalities and particularities with research conducted in temperate regions. Similar to Dolédec et al. (2011), we identified large-scale ecoregions as a primary driver of trait differentiation. However, unlike Zuellig and Schmidt (2012), who reported consistent land-use effects on traits across ecoregions in the United States, our study demonstrates that in the highly urbanized lowlands of Beijing, the influence of chemical pollution overshadows that of natural geographical variation. This observation aligns with Brown et al. (2018), who documented powerful filtering effects of strong environmental gradients in glacial retreat streams. Such comparisons underscore that under intense anthropogenic pressure, management strategies must account for region-specific combinations of driving factors. Our results indicate that river conservation in Beijing’s mountainous areas should prioritize the maintenance of natural hydrological regimes and physical habitat integrity. Conversely, for rivers in the lowlands, the primary focus must shift to mitigating water pollution, specifically nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as organic pollutants, to restore the functional diversity of macroinvertebrate communities. Furthermore, this study provides a scientific framework to support biodiversity conservation, ecosystem monitoring, and degradation diagnosis in comparable ecoregions, including semi-arid urban rivers and mountain–lowland transition zones.

While this study has identified key drivers of functional trait differentiation in macroinvertebrates between mountainous and lowland rivers, several limitations should be acknowledged. These limitations also point to directions for future research. First, the data were collected within a single year. Although different seasons were covered, this design may not fully capture the long-term effects of interannual climate variability or extreme hydrological events on community trait structure. Future studies should therefore incorporate long-term monitoring to better understand trait dynamics in response to climate change. Second, taxonomic resolution may influence trait assignment. Although organisms were identified to the finest practicable taxonomic level, some groups could only be determined to genus or family. While we applied typical genus- or family-level traits for these groups, this coarser resolution might obscure interspecific trait variation. Further refinement of the trait database should be pursued as taxonomic knowledge advances. Third, although the fuzzy coding approach offers advantages in handling trait variability, it may smooth over certain critical trait–response relationships. Incorporating continuous traits or adopting more complex modeling frameworks could help address this limitation.

Despite these constraints, this study underscores the significant potential of the functional trait approach in river health assessment. Future river restoration strategies should look beyond taxonomic diversity and place greater emphasis on recovering functional diversity. Creating conditions that facilitate the recolonization of taxa with high functional redundancy will be crucial for enhancing the overall resilience of river ecosystems.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates that macroinvertebrate communities in mountain and lowland rivers of Beijing are assembled through distinct environmental filters, leading to pronounced functional differentiation. Mountain rivers, with their high flow velocity and complex habitats, select for traits such as strong swimming ability, clinging habits, and short life cycles. In contrast, lowland rivers, impacted by sluggish flows and nutrient pollution, are dominated by burrowing, pollution-tolerant taxa with longer life cycles. This functional shift results in significantly lower functional diversity in the lowlands, confirming widespread functional homogenization due to human activity.

Critically, the dominant environmental drivers differ by ecoregion: natural hydrological and physical factors govern trait assembly in the mountains, while chemical pollution is the primary filter in the lowlands. This divergence demands ecoregion-specific management. Protection of natural flow regimes is essential in the mountains, whereas restoration of lowland rivers requires urgent mitigation of nutrient and organic pollution. Our findings underscore the power of a functional trait approach for river health assessment. Future research should prioritize long-term monitoring and refined trait databases to further advance trait-based river management.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YZ: Data curation, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MZ: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. XQ: Writing – review & editing, Project administration. HZ: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Writing – review & editing. HW: Writing – review & editing. ZL: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFC3212600) and National Science and Technology Major Project (2025ZD1202104).

Conflict of interest

Author ZL was employed by the company Hebei Water Conservancy Engineering Bureau Group Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer GL declared a past co-authorship with the author(s) MZ and XQ to the handling editor.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ackerly D. and Cornwell W. (2007). A trait-based approach to community assembly: partitioning of species trait values into within-and among-community components. Ecol. Lett. 10, 135–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.01006.x

Akamagwuna F. C., Mensah P. K., Nnadozie C. F., and Odume O. N. (2019). Trait-based responses of Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera to sediment stress in the Tsitsa River and its tributaries, Eastern Cape. River Res. Appl. 35, 999–1012. doi: 10.1002/rra.3458

Allan J. D. (2004). Landscapes and riverscapes, the influence of land use on stream ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 257–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.120202.110122

Ao S., Ye L., Liu X., Cai Q., and He F. (2022). Elevational patterns of trait composition and functional diversity of stream macroinvertebrates in the Hengduan Mountains region, Southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 144, 109558. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109558

Archaimbault V., Usseglio-Polatera P., Garric J., Wasson J. G., and Babut M. (2009). Assessing pollution of toxic sediment in streams using bio-ecological traits of benthic macroinvertebrates. Freshw. Biol. 55, 1430–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02281.x

Bêche L. A. and Statzner B. (2009). Richness gradients of stream invertebrates across the USA: taxonomy- and trait-based approaches. Biodivers. Conserv. 18, 3909–3930. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9688–1

Benítez A., Aragón G., González Y., and Prieto M. (2018). Functional traits of epiphytic lichens in response to forest disturbance and as predictors of total richness and diversity. Ecol. Indic. 86, 18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.12.021

Botta-Dukát Z. (2005). Rao's quadratic entropy as a measure of functional diversity based on multiple traits. J. Vegetation Science. 16, 533–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2005.tb02393.x

Brinkhurst R. O. (1986). Guide to the freshwater aquatic microdrile Oligochaetes of North America. Freshw. Sci. 6, 78–79. doi: 10.2307/1467254

Brown L. E., Khamis K., Wilkes M., Blaen P., Brittain J. E., Carrivick J. L., et al. (2018). Functional diversity and community assembly of river invertebrates show globally consistent responses to decreasing glacier cover. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 325–333. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0426-x

Chalcraft D. R., Williams J. W., Smith M. D., and Willig M. R. (2004). Scale dependence in the species-richness-productivity relationship: the role of species turnover. Ecology 85, 2701–2708. doi: 10.1890/03-0561

Cornwell W. K., Schwilk D. W., and Ackerly D. D. (2006). A trait-based test for habitat filtering: convex hull volume. Ecology 87, 1465–1471. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1465:ATTFFH]2.0.CO;2

Dolédec S., Phillips N., and Townsend C. (2011). Invertebrate community responses to land use at a broad spatial scale: trait and taxonomic measures compared in New Zealand rivers. Freshw. Biol. 56, 1670–1688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2011.02597.x

Dray S. and Legendre P. (2008). Testing the species traits-environment relationships: the fourth-corner problem revisited. Ecology 89, 3400–3412. doi: 10.1890/08-0349.1

Elliott M. and Quintino V. (2007). The estuarine quality paradox, environmental homeostasis and the difficulty of detecting anthropogenic stress in naturally stressed areas. Mar. pollut. Bull. 54, 640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.02.003

Environmental Protection Administration of China (1993). Aquatic monitoring manual (Nanjing: Southeast University Press).

Epler J. H. (2001). Identification manual for the larval Chironomidae (Diptera) of Florida. (Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Environmental Protection).

Ferreira A. S. A., Hátún H., Counillon F., Payne M. R., and Visser A. W. (2015). Synoptic-scale analysis of mechanisms driving surface chlorophyll dynamics in the north atlantic. Biogeosciences. 12 (11). doi: 10.5194/bg-12-3641-2015.12(11)

Jiang W. X., Chen J., Wang H. M., He S. S., Zhuo L. L., Chen Q., et al. (2018). Study of macroinvertebrate functional traits and diversity among typical habitats in the New Xue River. Acta Ecol. Sin. 38, 2007–2016. doi: 10.5846/stxb201703050358

Jiang W., Pan B., Jiang X., Shi P., Zhu P., Zhang L., et al. (2021). A comparative study on the indicative function of species and traits structure of stream macroinvertebrates to human disturbances. Ecol. Indic. 129, 107939. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107939

Laliberté E. and Legendre P. (2010). A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 91, 299–305. doi: 10.1890/08-2244.1

Lamouroux N., Doledec S., and Gayraud S. (2004). Biological traits of stream macroinvertebrate communities: effects of microhabitat, reach, and basin filters. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc 23, 449–466. doi: 10.1899/0887-3593(2004)023<0449:btosmc>2.0.co;2

Larsen S., Pace G., and Ormerod S. J. (2011). Experimental effects of sediment deposition on the structure and function of macroinvertebrate assemblages in temperate streams. River Res. Appl. 27, 257–267. doi: 10.1002/rra.1361

Loreau M., Naeem S., Inchausti P., Bengtsson J., Grime J. P., Hector A., et al. (2001). Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science 294, 804–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1064088

Maasri A., Thorp J. H., Kotlinski N., Kiesel J., Erdenee B., and Jähnig S. C. (2021). Variation in macroinvertebrate community structure of functional process zones along the river continuum: New elements for the interpretation of the river ecosystem synthesis. River Res. Appl. 37, 665–674. doi: 10.1002/rra.3784

Mason N. W. H., Mouillot D., Lee W. G., Wilson J. B., and Setl H. (2005). Functional richness, functional evenness and functional divergence: the primary components of functional diversity. Oikos 111, 112–118. doi: 10.2307/3548774

Menezes S., Baird D. J., and Soares A. M. V. M. (2010). Beyond taxonomy: a review of macroinvertebrate trait-based community descriptors as tools for freshwater biomonitoring. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 711–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01819.x

Morse J. C., Yang L., and Tian L. (1984). Aquatic insects of China useful for monitoring water quality (Nanjing: Hohai University Press).

Mouchet M. A., Villéger S., Mason N. W. H., and Mouillot D. (2010). Functional diversity measures: an overview of their redundancy and their ability to discriminate community assembly rules. Funct. Ecol. 24, 867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01695.x

Naeem S. (1998). Species redundancy and ecosystem reliability. Conserv. Biol. 12, 39–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1998.96379.x

Pfisterer A. B. and Schmid B. (2002). Diversity-dependent production can decrease the stability of ecosystem functioning. Nature 416, 84–86. doi: 10.1038/416084a

Poff N. L. (1997). Landscape filters and species traits: towards mechanistic understanding and prediction in stream ecology. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc 16, 391–409. doi: 10.2307/1468026

Poff N. L., Olden J. D., Vieira N. K. M., Finn D. S., Simmons M. P., and Kondratieff B. C. (2006). Functional trait niches of North American lotic insects: traits-based ecological applications in light of phylogenetic relationships. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc 25, 730–755. doi: 10.1899/0887-3593(2006)025[0730:ftnona]2.0.co;2

Southwood T. R. E. (1977). Habitat, the templet for ecological strategies. J. Anim. Ecol. 46, 336–365. doi: 10.2307/3817

Statzner B., Bis B., Dolédec S., and Usseglio-Polatera P. (2001). Perspectives for biomonitoring at large spatial scales: a unified measure for the functional composition of invertebrate communities in European running waters. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2, 73–85. doi: 10.1078/1439-1791-00039

Tachet H., Richoux P., Bournaud M., and Usseglio-Polatera P. (2002). Invertebres d’Eau Douce: Systematique, Biologie, Ecologie (Paris: CNRS editions).

The State Environmental Protection Administration (2002). Water and Wastewater Monitoring and Analysis Methods. 4th ed (Beijing: China Environmental Science Press).

Usseglio-Polatera P., Bournaud M., Richoux P., and Tachet H. (2000). Biological and ecological traits of benthic freshwater macroinvertebrates: relationships and definition of groups with similar traits. Freshw. Biol. 43, 175–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00535.x

Vannote R. L., Minshall G. W., Cummins K. W., Sedell J. R., and Cushing C. E. (1980). The river continuum concept. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 37, 130–137. doi: 10.1080/00288330.1982.9515966

Wiggins G. B. (1996). Larvae of the North American caddisfly genera (Trichoptera). 2nd ed (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Wu N., Huang J., Schmalz B., and Fohrer N. (2014). Modeling daily chlorophyll a dynamics in a german lowland river using artificial neural networks and multiple linear regression approaches. Limnology. 15 (1), 47–56. doi: 10.1007/s10201-013-0412-1

Wise E. J. (1980). Seasonal distribution and life histories of Ephemeroptera in a Northumbrian river. Freshw. Biol. 10, 101–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1980.tb01185.x

Zhang Y. H., Qu X. D., Peng W. Q., Zhang M., Zhang H. P., Du L. F., et al. (2023). Health assessment of the stream ecosystem in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. 44, 5478–5489. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.202210126

Zhang F., Tang X., Lin P., Shang K., Han Y., Liu X., et al. (2025). Taxonomic and functional diversity of macroinvertebrate community along the elevation gradient and in different seasons in the upper Jinsha River (Qinghai-Tibet Plateau). Glob. Ecol. Conserv., e03703. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03703

Zhang Y. H., Zhang M., Zhang H. P., Yu Y., Wang Y., Sun S., et al. (2018). Study on the spatial pattern of macroinvertebrate and their responses to environmental changes in Beijing rivers. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 13, 101–110. doi: 10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20171019001

Zheng B. H., Zhang Y., and Li Y. B. (2007). Study of indicators and methods for river habitat assessment of Liao River Basin. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 27, 928–936. doi: 10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2007.06.010

Zhou C. F. (2002). A taxonomic study on mayflies from mainland China (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) (Tianjin: Nankai University).

Keywords: Beijing river, biological traits, functional diversity, RLQ analysis, fourth-corner, environmental variables

Citation: Zhang Y, Zhang M, Qu X, Zhang H, Zhang B, Wang H and Liu Z (2025) Drivers of functional trait-based differentiation in macroinvertebrate communities between lowland and mountainous rivers. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1692850. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1692850

Received: 26 August 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025; Revised: 03 October 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Fernanda Michalski, Universidade Federal do Amapá, BrazilReviewed by:

Tiziana Di Lorenzo, National Research Council (CNR), ItalyGuohao Liu, University of Helsinki, Finland

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Zhang, Qu, Zhang, Zhang, Wang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Min Zhang, emhhbmdtaW5AaXdoci5jb20=

Yuhang Zhang

Yuhang Zhang Min Zhang

Min Zhang Xiaodong Qu

Xiaodong Qu Haiping Zhang1,2,4

Haiping Zhang1,2,4