- Animal Evolutionary Ecology, Institute of Evolution and Ecology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Background: Using controlled illumination to improve vision was believed to be limited to bioluminescent organisms in dark environments. Recent findings suggest that in shallow water, triplefins redirect sunlight to induce luminance contrast in the retroreflective pupils of nearby predators. At greater depths this mechanism becomes less effective. Triplefins, however, also possess red fluorescent irises. These may serve as an alternative light source to detect predator pupils in deeper waters by inducing a colour contrast. We tested whether triplefin iris fluorescence enhances the detection of predators.

Methods: In the first experiment, triplefins were exposed to a scorpionfish (predator) or a stone (control) under conditions that either allowed or prevented their iris fluorescence from illuminating the target. In the second experiment, triplefins were exposed to dummy scorpionfish with (1) retroreflective eyes, (2) non-retroreflective eyes, or (3) a live scorpionfish (control). In both experiments head bobbing was quantified as a known measure of caution.

Results: Triplefins bobbed more to live scorpionfish under all conditions, but significantly more when fluorescence could be used to illuminate the scorpionfish. Neither was the case for stones or (non-)retroreflective models. A weak fluorescence effect was found when comparing retroreflective versus non-retroreflective models.

Conclusions: Fluorescent irises may facilitate detection of retroreflective scorpionfish pupils. However, the weak response to the models suggests more than just retroreflection plays a role.

1 Introduction

Predation exerts one of strongest selection pressures on prey populations, as failure to evade predators can result in mortality, physical harm or stress-related fitness costs (Kerfoot and Sih, 1987; Preisser et al., 2005). Successful evasion requires prey to detect predators reliably and assess the risk they pose. To achieve this, prey integrate information from a variety of sensory modalities, including visual (Coates, 1980; Gerlai, 1993; Wisenden and Harter, 2001), chemical (Kats and Dill, 1998; Bronmark and Hansson, 2000; Hettyey et al., 2015), acoustic (Blumstein et al., 2008; Radford et al., 2012; Hettena et al., 2014), and mechanical cues (Janssen, 2004; Yack, 2016).

Aquatic vertebrates mostly rely on chemical (Chivers and Smith, 1998; Wisenden, 2000; Brown, 2003; McCormick and Manassa, 2008) and visual cues (Helfman, 1989; Smith and Belk, 2001; Murphy and Pitcher, 2005; McCormick and Manassa, 2008) for predator detection. Recent research revealed that fish mostly use chemical cues to indicate the presence of a predator and use visual cues to modify their response to the predator (Hartman and Abrahams, 2000; Chivers et al., 2001). Visual cues are often considered to be part of passive sensing systems since they rely on external conditions that are not controllable by the organism. One exception to this are cases where fish improve their vision by means of controlled illumination (Nelson and MacIver, 2006). Controlled illumination was previously believed to be limited to bioluminescent organisms (Hellinger et al., 2017; Howland et al., 1992; Kenaley et al., 2014; Sutton, 2005). However, recent findings suggest that diurnal fish such as the triplefin, Tripterygion delaisi, are also capable of using active illumination. As is the case for many fishes, triplefins use the spherical lens that protrudes from their pupil to focus downwelling light on a bright patch located on the iris below the pupil. This is called an “ocular spark” and can be turned on or off at will (Michiels et al., 2018). It is proposed that they can use their ocular sparks to generate perceptible reflections in the retroreflective eyes of nearby prey or cryptic predators, and defined this process as ‘Diurnal Active Photolocation (DAP)’ (Bitton et al., 2019; Santon et al., 2020). For DAP to be effective, three conditions must be met:

1. The target must possess strong retroreflective eyes, and the observer must possess a light source located nearly coaxial to its gaze, e.g. very close to the pupil (Greene and Filko, 2010; Jack, 2014; Michiels et al., 2018; Santon et al., 2018). The latter is required because retroreflectors reflect the incoming light in a narrow angle back to the light source. If the observer’s light source is in line with its gaze, the light that is reflected back from the target’s retroreflective eye will enter the observer’s pupil.

2. The distance between observer and target is less than 10 cm (Bitton et al., 2019; Santon et al., 2020), making it more likely in small fishes that detect their predators (or prey) over short distances.

3. The ocular-spark-based variant of DAP requires strong directional downwelling sunlight, conditions usually found in waters shallower than 10 meters.

At increasing depths, clear marine light fields undergo a fundamental shift: Illumination changes from direct downwelling to bluish, scattered light (Warrant and Johnsen, 2013). This change in both the angular distribution and spectral quality significantly reduces the efficacy of ocular-spark-based light redirection. Clear deep water, however, provides excellent conditions for red fluorescence to stand out (Neumeyer et al., 2002; Harant et al., 2016, 2018; Wilkins et al., 2016; Bitton et al., 2017). This is not the case in shallow water: Although there is more excitation light available here, any red fluorescence is flooded by the overwhelmingly strong red component of the shallow light spectrum.

Triplefins, along with many other small benthic fish species (2–5 cm), possess strong red fluorescent irises (Figure 1) (Anthes et al., 2016; Michiels et al., 2018). In T. delaisi, fluorescence peaks at 609 nm with a broad excitation spectrum peaking in the green range (530 nm) (Bitton et al., 2017). Triplefins regulate their fluorescence in response to ambient light conditions and show significantly stronger fluorescence in waters deeper than 20 meters. This, combined with the fact that they can perceive their own fluorescence, suggest that it serves a visual function (Michiels et al., 2008, 2018; Wucherer and Michiels, 2012, 2014; Kalb et al., 2015; Harant et al., 2016). Because of this we hypothesize that a red fluorescent iris can function as a light source for DAP in deeper water, e.g. below 20 m.

Figure 1. The triplefin Tripterygion delaisi in a blue-green environment at 29 m depth as seen by a human SCUBA diver (Nikon D500, natural light, manual white balance, LEE Sunset-Red colour correction filter) (N.K. Michiels). Inset: A triplefin under a broad light spectrum in 5 m depth, where fluorescence is overwhelmed by the strong red component of sunlight.

In this study, we test whether the red fluorescent iris of T. delaisi improves its ability to visually detect a nearby black scorpionfish (Scorpaena porcus), a cryptic sit-and-wait predator with strong retroreflective eyes (Schwab et al., 2002; Fritsch et al., 2017; Santon et al., 2018, 2020). To test this, we performed two experiments. First, we tested if red fluorescence affected the behavioural response of a triplefin to a nearby scorpionfish. To do so we placed different filters that blocked specific wavelengths between the triplefin and the scorpionfish to control whether the triplefin’s red fluorescence was allowed to contribute to the illumination of the scorpionfish or not. In the second, triplefins were confronted with a 3D-printed model of a scorpionfish with either a retroreflective or a non-retroreflective eye. A third group was tested with live scorpionfish as a positive control.

2 Methods

2.1 Location

Data collection took place at STARESO (Station de Recherches Sous Marines et Océanographiques, Calvi, France). Fish were collected and returned to the field under the general research permit of the station.

2.2 Model species

2.2.1 Triplefin (Tripterygion delaisi)

Triplefins (3–6 cm, Figure 1) are cryptobenthic micro-predators inhabiting rocky substrates between 5 and 50 m depth in the Mediterranean Sea and Eastern Atlantic Ocean. They use a saltatory movement pattern, consisting of short forward hops interspersed with pauses, during which they assess their surroundings with independently moving eyes. While exploring an environment, a triplefin often shows bobbing, which involves raising and lowering its anterior body in a “push-up” motion which takes one second to complete (Wirtz, 1978). Bobbing increases in frequency in the presence of a scorpionfish (Wirtz, 1978; Santon et al., 2021). Bobbing is not unique to triplefins, it has also been linked to threat perception in other taxa including: different gobies (Smith, 1989; McCormick and Manassa, 2008), harvestmen (Calhoun et al., 2025), jumping spiders (Geiger et al., 2025) and meerkats (Graw and Manser, 2007). We collected triplefins using hand nets at 20–30 m depth while SCUBA diving. Individuals from these depths fluoresce more strongly than those from shallower waters (Michiels et al., 2008; Wucherer and Michiels, 2012, 2014; Harant et al., 2016). After collection, fish were transported in perforated Falcon tubes and housed in flow-through tanks with natural substrates. To prevent downregulation of fluorescence, tanks were lit with dim blue-green light simulating 25 m depth, using RGB-LEDs (Cameo Q-SPOT 40 RGBW WH) with setting: red = 0, green and blue = 255 and covered with a double layer of “LEE 172 Lagoon Blue” filters. Spectrometry confirmed that no light > 570 nm was emitted under these settings (see electronic Supplementary Material, Supplementary Figures S1, S2).

2.2.2 Scorpionfish (Scorpaena porcus)

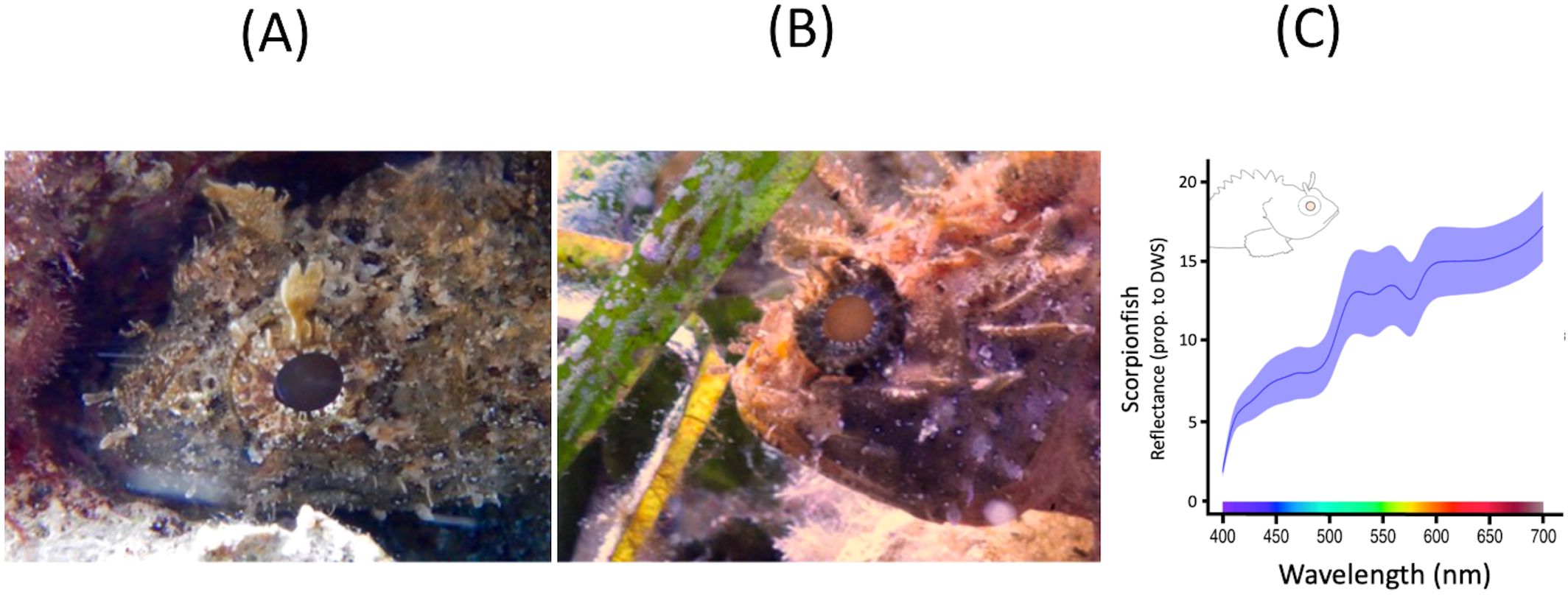

Scorpionfish are cryptobenthic, sit-and-wait macropredators common on hard substrates and seagrass beds across the Mediterranean Sea and Northeast Atlantic Ocean (Louisy, 2015). They prey on small cryptobenthic fishes, including triplefins (Compaire et al., 2018; Santon et al., 2018). Interestingly scorpionfish can produce acoustic signals that may be perceivable by triplefins (Kobayashi et al., 2004; Radford et al., 2012). Scorpionfish have large pupils with strong retroreflective properties, especially in the red spectrum (Figure 2) (Santon et al., 2018). This improves their camouflage but, as a trade-off, makes them prone to detection by observers possessing a light source, especially a red one, near their pupils. The rest of their body only fluoresces very weakly in the red range of the visual spectrum (John et al., 2023) (see electronic Supplementary Material, Supplementary Figure S3). We collected scorpionfish using hand nets at 2–10 m depth after sunset and housed them in large, shaded flow-through tanks with rocky shelters.

Figure 2. Scorpaena porcus in the field. (A) Shaded at 3 m depth, with dark pupil (weak eyeshine). (B) Exposed in 7 m depth, with strong eyeshine, caused by a mix of transmission-based and retroreflective eyeshine. (C) Pupil reflectance expressed as a proportion of the pupil photon radiance relative to a PTFE white diffuse reflectance standard (y-axis). A value of 15 means that pupil radiance is 15 times brighter than a 99% white reflectance standard when measured under the same conditions. Blue area: SE of mean curve (Santon et al., 2018).

2.3 Experiment 1: Scorpionfish detection with and without fluorescence (Summer 2022)

We tested each triplefin individually in a white polyethylene tray (52 x 31 x 21 cm, Figure 3) featuring a central lane with glued on black sand (11.5 x 30 cm) that encouraged linear movement. At the end of the track, we placed a stimulus box with two compartments, both with a glass front. One compartment contained a scorpionfish (predator), the other a size-matched stone (control). Only one compartment was visible to the triplefins at any time. The box’s perforated opaque side panels allowed olfactory cues to pass.

Figure 3. Schematic of the setup used in Experiment 1 and 2, built into a rectangular PE tray and filmed from above. (A) 3D view showing key elements. (B) Detailed top view. Triplefins are set free from a plexiglass cylinder (5) on a strip of glued black sand (4), which they prefer over the bright surface of the arena. Within 10 minutes, most individuals will gradually hop towards the stimulus box for close inspection. The box contains two compartments for two visual stimuli. Only one is visible to a triplefin through glass and a filter (3) at any time. The box can be rotated 180° or replaced by another box between runs. The top part of the black panels of the box are perforated for water exchange, allowing the transfer of chemical and acoustic cues between the scorpionfish and triplefin. They also prevent that the scorpionfish falls dry when taking the box out.

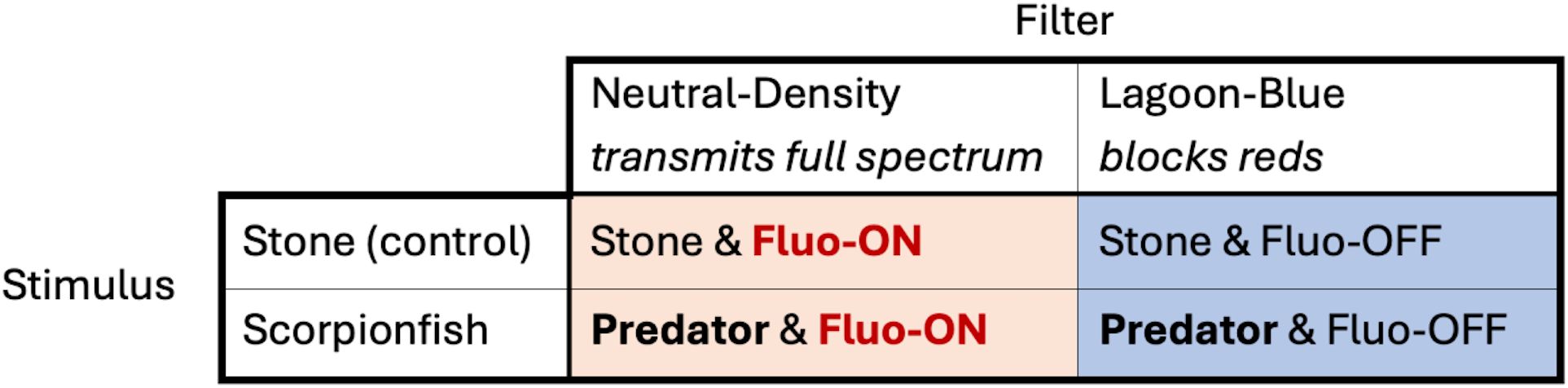

To control the contribution of red fluorescence to the visual perception of the stimulus by the triplefin we attached different filters to the glass fronts of the stimulus box. A “LEE 172 Lagoon Blue” (LB) filter, blocking the red part of the spectrum, was used in runs in which the contribution of fluorescence to visual assessment of the stimulus was blocked. A “LEE 209 0.3 Neutral Density” (ND) filter was used in control runs to correct for the reduced brightness caused by the LB filter, while leaving the spectral shape of the light illuminating the stimulus unaffected. The Neutral Density filter allowed triplefins to also perceive longer wavelengths, including their own (reflected) red fluorescence. Spectrometry confirmed that both filters allowed about the same amount of light to pass under the experimental light conditions (LB: 1.451*1017 photons/s/sr/m/nm; ND: 1.276*1017 photons/s/sr/m/nm – measured by aiming at a diffuse white PTFE reflectance standard). Filters were replaced every 20 runs. This resulted in four treatments in a 2 x 2 design (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Table of possible treatment combinations of Experiment 1. Two stimuli, a stone and a scorpionfish, together with two different filters resulted in four different treatments. Fluo-ON refers to treatments with a Neutral-Density filter and Fluo-OFF refers to treatments with a Lagoon-Blue filter.

We exposed each triplefin to all four treatments (4 “runs”) in one of four fixed treatment sequences. Since our main interest was to reveal the difference between the scorpionfish with a Neutral-Density filter (Fluo-ON) versus the scorpionfish with a Lagoon-Blue filter (Fluo-OFF), a scorpionfish treatment always followed a scorpionfish treatment, and a stone treatment always followed a stone treatment (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Table of each possible treatment sequences that a triplefin could encounter during Experiment 1. Each triplefin was tested 4 times (4 runs) and represents a single “treatment sequence”. A scorpionfish treatment always followed a scorpionfish treatment, and a stone treatment always followed a stone treatment to ensure a balanced design.

Before each run, we placed the triplefin in an opaque holding container outside the setup for 2 minutes. Each run started with a 2-minute acclimation in a see-through plexiglass cylinder at one end of the setup (Figure 3, object 5) after which fish were released and recorded from above for 10 minutes using a GoPro (Hero black 7). To minimize stress and effects caused by individual differences between scorpionfish, we replaced scorpionfish repeatedly during the whole experiment (n = 35 S. porcus).

2.3.1 Video analyses experiment 1

During video analysis, we counted triplefin bobbing frequency, a measure of recognition of potential danger (Santon et al., 2021), using BORIS (Friard and Gamba, 2016). We also measured the minimum distance to the stimulus box (± 1 cm), the latency until triplefins reached this minimum distance (in seconds) and the average distance to the stimulus box during the 10-minute run. The average minimum distance of the triplefins to the display compartment across all treatments was 7 cm. However, with a median of 0 cm this indicates a heavily skewed distribution (Figure 6A). This also applies to the average distance (Figure 6B) and latency (not shown). Since only bobbing frequency showed significant treatment effects, the other measurements are not addressed in detail.

Figure 6. Heavily skewed distributions of the (A) Minimum distance (mean:7, median:0) and (B) Average Distance (mean:11, median:5) of Experiment 1.

We tested a total of 127 triplefins, balanced across all treatment sequences, but excluded five triplefins due to technical problems. The final analyses include 122 triplefins. Data exploration indicated that bobbing became less frequent during the four consecutive runs, indicating strong habituation to the set-up. Some triplefins did not perform a single “bob” during all runs. We therefore chose to only include the first two runs of each triplefin that bobbed at least once during one of these two runs. This still allowed us to compare a visual stimulus with both fluorescent treatments within each triplefin (n = 52 and n = 51 for stone and scorpionfish respectively).

2.4 Experiment 2: Isolating eye-retroreflection (Summer 2023)

The first experiment did not allow us to distinguish whether triplefins responded specifically to the retroreflective eyes of the scorpionfish or to other visual features. To address this, we conducted a second experiment that isolated the retroreflective-eye effect using 3D printed scorpionfish models. We created realistic scorpionfish models by 3D-printing them with matt grey PLA filament (1.75 mm, FormFutura, Nijmegen, the Netherlands) using a Prusa i3 MK3s printer (Prusa Research, Czech Republic). After hand-painting the models with commercial acrylic paints and a matte varnish, we soaked them in saltwater for several days before use (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Photos of 3D-printed scorpionfish models used in Experiment 2. In all photos the left model is a model with retroreflective eye-insert and the right model is a model with non-retroreflective eye-insert. Both models are fitted with a Sunset Red filter in the eye to simulate the natural reddish retroreflection of a scorpionfish’s eye. (A) Photo taken under ambient white light, no-coaxial light. (B) Photo taken under ambient white light, with added coaxial white light. (C) Photo taken under the blue-green light conditions of the set-up, no-coaxial light. (D) Photo taken under the blue-green light conditions of the set-up, with added coaxial red light.

The models had a 15° tilt to orient their gaze to a point on the substrate at 10–12 cm from the model’s eye. All models shared an identical pupil area of 50.27 mm². We produced the pupil inserts separately from PVC cylinders, allowing us to fit either a retroreflective or a non-retroreflective artificial eye.

For the retroreflective eye treatment, we used Orafol (“ORALITE Commercial Grade 5410”) which generates strong white retroreflection. We overlaid the retroreflector with a LEE 025 Sunset Red filter (Lee Filters) to mimic the warm reddish glow observed in natural scorpionfish eyes under coaxial illumination with white light. The filter also suppressed any bluish reflection caused by environmental blue-green light (< 550 nm). Spectrometry confirmed that the artificial eye’s retroreflection was 5–10 times stronger than that of a real scorpionfish’s eye in the long-wavelength range (Figure 8). It was a deliberate choice to use a “super-stimulus”. For the non-retroreflective eye treatment, we inserted a piece of diffuse white underwater paper (Weatherproof transparencies, Avery Zwerckform GmbH), also covered with a LEE 025 Sunset Red filter (Lee Filters). It ensured that both eye types appeared similar under ambient light without coaxial illumination. We refrained from using a glass lens in the models since previous trials showed that they produce reflection artifacts on their outer surface which are virtually absent in the cornea of real scorpionfish. As a third visual stimulus we included a live scorpionfish in the experiment to validate the findings from the first experiment.

Figure 8. Wavelength-dependent retroreflective eyeshine in Scorpaena porcus. (A) Pupil reflectance expressed as a proportion of the pupil photon radiance relative to a PTFE white diffuse reflectance standard (y axis). A value of 15 means that pupil radiance is 15 times brighter than a 99% white reflectance standard when measured under the same conditions. Blue area: SE of mean curve (modified from: Santon et al., 2018). (B) Retroreflector reflectance expressed as a proportion of the pupil photon radiance relative to a PTFE white diffuse reflectance standard (y axis). (C) Retroreflector covered by a LEE 025 Sunset Red filter, as used in Experiment 2, expressed relatively to a scorpionfish pupil.

In all three treatments, the contribution of red fluorescence was controlled by using filters attached to the glass front of the stimulus box as in experiment 1 (LEE 172 Lagoon Blue and LEE 209 0.3 Neutral Density for Fluo-OFF and Fluo-ON), resulting in 6 treatments (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Table showing the possible treatment combination of Experiment 2. Three different visual stimuli (Model without retroreflective eyes, Model with retroreflective eyes and a Scorpionfish) together with two fluorescent treatments (Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF) result in the six different treatments.

We presented a single stimulus (retroreflective model, non-retroreflective model or scorpionfish) to each triplefin under both fluorescent treatments (Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF). This design limited the number of runs per triplefin to two. To address potential effects of olfactory, chemical and acoustic cues, a live scorpionfish was always present in a perforated opaque box within the arena while running the model treatments. This opaque box was empty in runs with a live scorpionfish stimulus. The testing procedure and data collection were identical to experiment 1.

2.4.1 Video analyses experiment 2

We filmed all runs using GoPros (Hero 7 Black) and quantified bobbing frequency, using BORIS (Friard and Gamba, 2016). To ensure that scorpionfish behavior did not confound the results, we also recorded their movement during each run. We quantified total movement duration per run using BORIS and used these data to test whether Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF treatments differentially affected scorpionfish activity, potentially offering an alternative explanation for the patterns observed in Experiment 1.

2.5 Statistical analyses

We conducted all statistical analyses in R (R Core Team, 2024), using the glmmTMB package (Brooks et al., 2017), following the framework established in Santon et al. (2023). In the following, we explain our data analyses for each experiment in detail.

2.5.1 Experiment 1

2.5.1.1 Scorpionfish detection with and without fluorescence

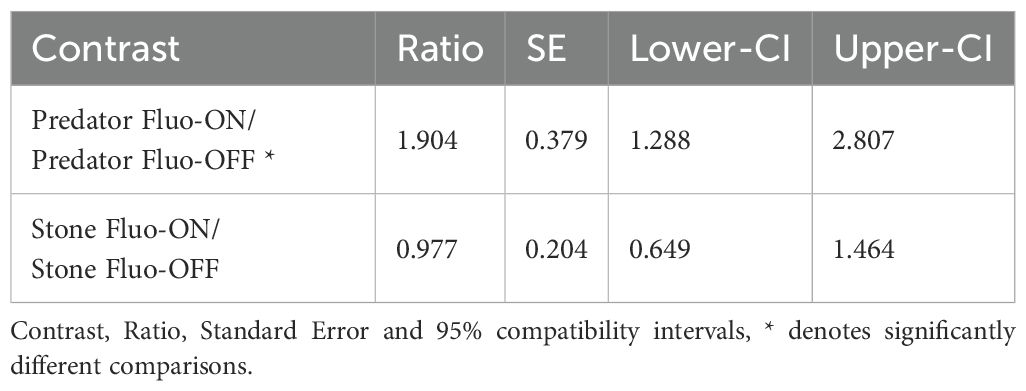

To evaluate whether red fluorescence influenced scorpionfish detection, we analyzed bobbing frequency across treatments during the first two runs for each triplefin, which were either exposed to a stone under Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF conditions or a live scorpionfish under Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF.

The model used a negative binomial distribution (linear parameterization with log-link) (Hardin and Hilbe, 2012) with three fixed components: (1) stimulus (stone or scorpionfish), (2) filter (Fluo-ON or Fluo-OFF), and (3) the interaction term between stimulus and filter. To account for repeated measures, we included Triplefin ID as a random effect (Schielzeth and Forstmeier, 2009). Additionally, we incorporated a zero-inflation formula following a constant (= 1) to address potential excess zeros in the count data (Campbell, 2021). To verify that the model did not violate key assumptions, we checked residual distribution, residuals against predictors (split by random factor levels), dispersion, zero inflation, data distribution and autocorrelation. We also confirmed that there were no order, time, or date effects.

2.5.2 Experiment 2

2.5.2.1 Scorpionfish movement

To check for possible correlation between the movement of a scorpionfish and the bobbing frequency of triplefins, a model was made based on a negative binomial distribution with a linear parameterization and a log-link function (Hardin and Hilbe, 2012). The model contained the bobbing frequency of triplefins as response variable and scorpionfish movement as a fixed component. A zero-inflation formula following a constant (= 1), was added (Campbell, 2021). To verify that the model did not violate key assumptions, we checked residual distribution, residuals against predictors (split by random factor levels), dispersion, zero inflation, data distribution and autocorrelation. We also confirmed that there were no order, time, or date effects.

2.5.2.2 Isolating eye-retroreflection

To examine whether eye retroreflection influenced bobbing behaviour, we constructed a model using a negative binomial distribution with log-link function and linear parameterization (Hardin and Hilbe, 2012) with three fixed components: (1) stimulus (retroreflective model, non-retroreflective model, or scorpionfish), (2) filter (Fluo-ON or Fluo-OFF), and (3) the interaction between stimulus and filter. Triplefin-ID was added as a random term to account for the two repeated measurements of each triplefin (Schielzeth and Forstmeier, 2009). A zero-inflation formula following the filter component and a dispersion formula following the stimulus and filter components was added (Campbell, 2021). To verify that the model did not violate key assumptions, we checked residual distribution, residuals against predictors (split by random factor levels), dispersion, zero inflation, data distribution and autocorrelation. We also confirmed that there were no order, time, or date effects.

3 Results

3.1 Experiment 1: Scorpionfish detection with and without fluorescence

In experiment 1, we confronted a triplefin with either a scorpionfish or a stone under both Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF conditions. The absolute number of bobs per run differed across the treatments (Figure 10, Table 1): Triplefins bobbed 50 times (95% compatibility interval: 35.4-69.8) when confronted with a scorpionfish under the Fluo-ON treatment. This was significantly decreased when confronted with a scorpionfish with Fluo-OFF (26.3 times, 95% CI: 18.2-37.7). In contrast, they only bobbed 12.7 times (95% CI: 8.8-18.0) when seeing a stone under Fluo-ON, which was similar to seeing a stone under Fluo-OFF (12.9 times, 95% CI: 8.9-18.9).

Figure 10. Experiment 1, Stone vs Scorpionfish. Absolute bobbing frequency in a 10-minute run as a function of visual stimulus (Stone or Predator) and filter treatment (Fluo-ON or Fluo-OFF). T. delaisi individuals were tested in a paired design per visual stimulus, and therefore either saw a stone or a Predator, under both Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF treatments in varying and balanced order. Predicted means and 95% compatibility intervals (CI), based on a negative binomial distribution with a log-link. n.s. denotes a non-significant difference, *** denotes a significant difference.

3.2 Experiment 2: Scorpionfish movement

When comparing the movements of the scorpionfish between the Fluo-OFF and Fluo-ON treatments, we found no effect of filter type on the movement of the scorpionfish (see electronic Supplementary Material, Supplementary Figure S4). We further analyzed if scorpionfish movement, expressed as movement in seconds during a run, was related to the bobbing frequency of a triplefin. We found no correlation between the movement durations of a scorpionfish and the bobbing frequency of a triplefin (see electronic Supplementary Material, Supplementary Figure S5). Since we can assume that scorpionfish do not behave differently depending on the treatment, and that scorpionfish movement does not influence the bobbing frequency of a triplefin, it is safe to assume that the main results cannot be explained by a confounding effect caused by scorpionfish movement.

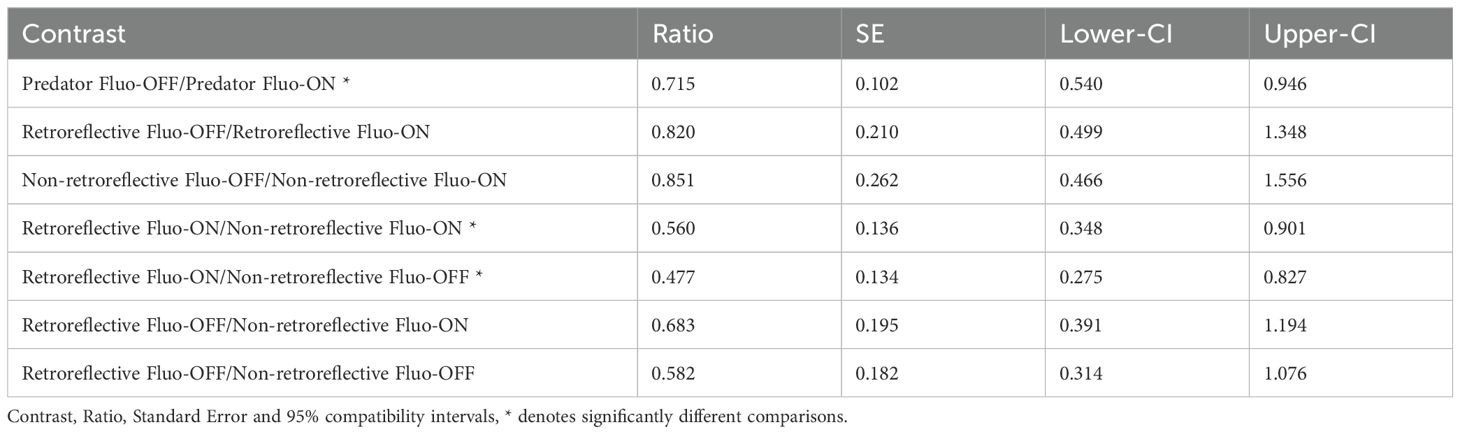

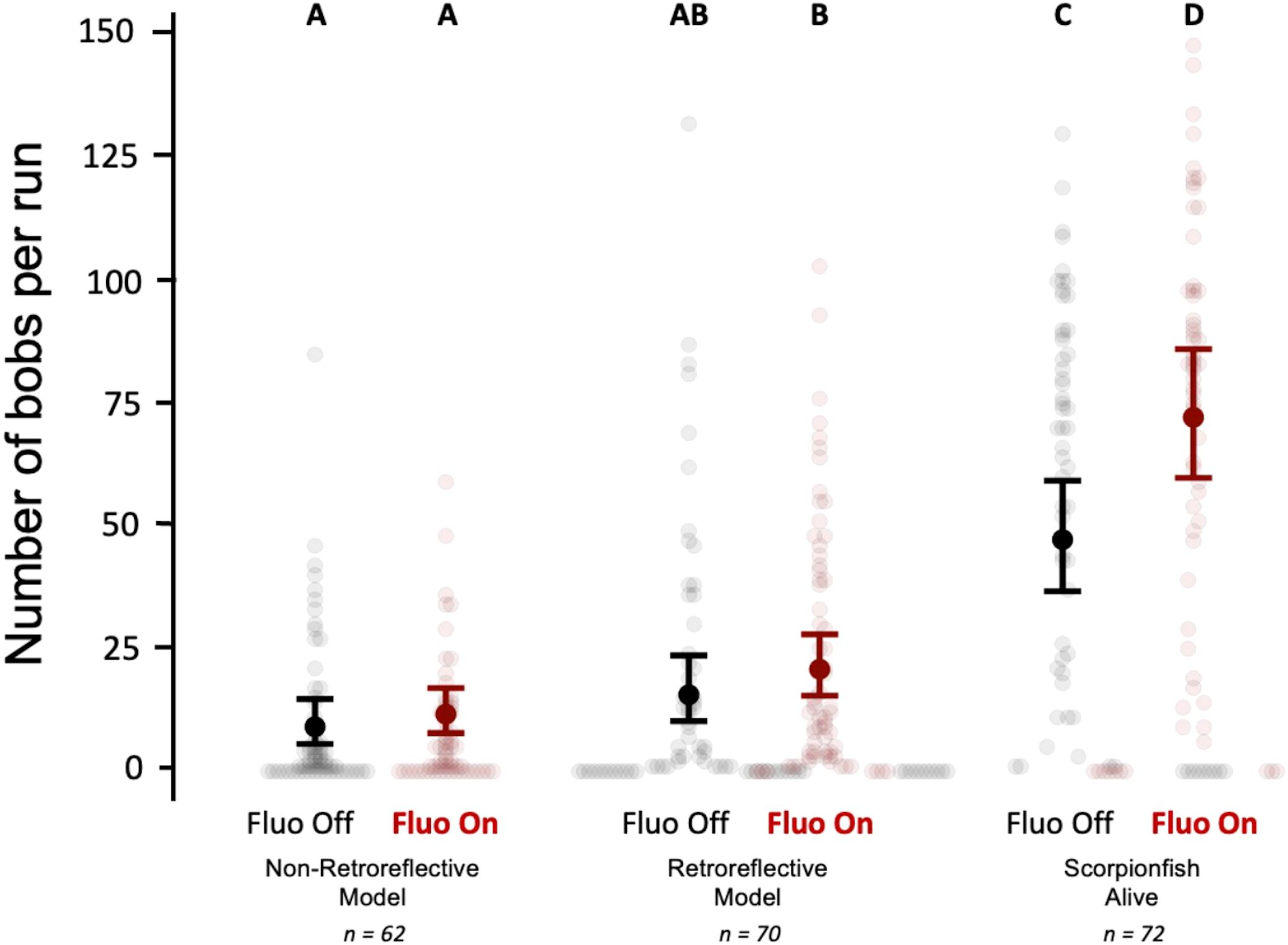

3.3 Experiment 2: 3D printed scorpionfish model retroreflection present or absent

In experiment 2, we confronted a triplefin with either a non-retroreflective model, a retroreflective model or a live scorpionfish (predator) under both Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF conditions. Triplefins showed more bobbing when confronted with a predator under Fluo-ON conditions 71.8 times (95% compatibility interval: 59.8-86.1) compared to a predator under Fluo-OFF conditions 46.9 times (95% compatibility interval: 36.7.8-59.3). This confirms the results from experiment 1. When comparing fluorescent conditions (Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF) within the two model treatments, we found no difference in bobbing frequency (Figure 11, Table 2). However, triplefins bobbed more often when confronted with the retroreflective model under Fluo-ON conditions 20.8 times (95% compatibility interval: 15.4-27.9) in comparison with the non-retroreflective model under both the Fluo-ON 11.6 times (95% compatibility interval: 7.8-17.0) and Fluo-OFF 9.0 times (95% compatibility interval: 5.6-14.7) conditions. This difference is absent when comparing the Fluo-OFF condition of the retroreflective model with the Fluo-ON and the Fluo-OFF condition of the non-retroreflective model (Figure 11, Table 2).

Figure 11. Experiment 2, 3D models vs Predator. Absolute bobbing frequency in a 10-minute run as a function of visual stimulus (Non-retroreflective model, Retroreflective model or Predator) and filter treatment (Fluo-ON or Fluo-OFF). T. delaisi individuals were tested in a paired design per visual stimulus, and therefore either saw a Retroreflective model, a Non-retroreflective model, or a Scorpionfish, under both Fluo-ON and Fluo-OFF treatments in varying and balanced order. Predicted means and 95% compatibility intervals (CI), based on a negative binomial distribution with a log-link. Different letters indicate a significant difference between the treatments.

4 Discussion

We tested whether the red light emitted by a triplefin’s fluorescent iris enhances its ability to detect a nearby scorpionfish (Experiment 1), and whether this can be explained by inducing and detecting fluorescence-induced eyeshine in the scorpionfish (Experiment 2).

Experiment 1 shows that bobbing, an indicator of seeing something “potentially dangerous” in triplefins (Santon et al., 2021), was particularly high in response to a scorpionfish relative to a stone, regardless of the FLUO treatment. This confirmed that bobbing in triplefins can be considered a reliable indicator of perceived danger, whereas a lack of it is associated with a safe visual scene (Smith, 1989; Graw and Manser, 2007; McCormick and Manassa, 2008; Calhoun et al., 2025; Geiger et al., 2025). Moreover, in the presence of a scorpionfish, bobbing was observed significantly more when fluorescence was “ON” relative to the “OFF” situation. This suggests that red fluorescent irises may indeed contribute to early detection of a scorpionfish.

However, these results cannot demonstrate that fluorescence was used to induce and detect retroreflective eyeshine in scorpionfish. Moreover, we did not check whether the scorpionfish moved more under the Fluo-ON than under the Fluo-OFF treatment. These issues were addressed during experiment 2. Here we showed that live scorpionfish did not move more in the Fluo-ON treatment and that there was no correlation between scorpionfish movement and triplefin bobbing frequency. Bobbing in triplefins is not exclusively associated with perceived threats, as triplefins also exhibited this behaviour when confronted with a stone. The comparatively low number of bobs observed in this context may be explained by motion parallax, a depth perception mechanism in which objects at varying distances appear to move at different speeds as the observer moves its head (Gibson et al., 1959; Kral, 2003; Bruckstein et al., 2005).

Experiment 2 confirmed a strong bobbing response toward live scorpionfish, with a significant difference between the fluorescence ON and OFF conditions, consistent with the results of Experiment 1. In contrast, responses to the retroreflective models were considerably weaker. Although the fluorescence ON/OFF comparison for these models showed only a subtle trend in the predicted direction, triplefins displayed more frequent bobbing toward retroreflective models with fluorescence ON than toward both non-retroreflective model treatments. This difference was not present when comparing the retroreflective model with fluorescence OFF against both non-retroreflective models. This suggests that models lacking retroreflective eyes are perceived as neutral objects, similar to stones, whereas retroreflective models elicit a response indicative of fluorescence-based retroreflection. The weak trend observed here might become more pronounced if the models were more lifelike (Brown and Warburton, 1997). Overall, these findings reinforce the idea that fish integrate multiple sensory modalities when detecting potential predators (Chivers and Smith, 1998; Blumstein et al., 2008; Radford et al., 2012; Hettena et al., 2014; Hettyey et al., 2015).

Research on active photolocation has mainly focused on two different light sources: redirected downwelling light (Bitton et al., 2019; Neiße et al., 2020; Santon et al., 2020) and bioluminescent organs (Howland et al., 1992; Hellinger et al., 2017) as the main light sources. Although it has been proposed that fluorescence could function as a light source for active photolocation (Jack, 2014), most of the studies on fluorescence focused on alternative function such as camouflage, photo-enhancement, intraspecific communication, prey attraction, photoprotection, or stress mitigation (Haddock and Dunn, 2015; Ben-Zvi et al., 2022; Poding et al., 2024). The use of red fluorescence for active photolocation can be expected to be limited to short-ranged interactions due to the low amounts of light involved. This aligns well with the observation that small benthic fishes in particular evolved red fluorescent irises, which may facilitate short-range visual predator detection (Anthes et al., 2016; Michiels et al., 2018).

Our findings highlight the potential for red fluorescence to serve as an alternative light source for diurnal active photolocation in blue-green environments at depth or in permanent shade, where bluish, scattered light is the dominant illuminant.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The general scientific permit of the STARESO Marine Station includes a general permission to collect animals for scientific purposes.

Author contributions

BS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Nico K. Michiels was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant number: MI 482/18-1).

Acknowledgments

We thank STARESO and its staff for their kind support and hosting us, and Leonie John, Mario Schädel, Lena Wesenberg, and Patrick Weygoldt for assistance in the field.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2025.1728992/full#supplementary-material

References

Anthes N., Theobald J., Gerlach T., Meadows M. G., and Michiels N. K. (2016). Diversity and ecological correlates of red fluorescence in marine fishes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 4. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00126

Ben-Zvi O., Lindemann Y., Eyal G., and Loya Y. (2022). Coral fluorescence: a prey-lure in deep habitats. Commun. Biol. 5, 537. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03460-3

Bitton P. P., Harant U. K., Fritsch R., Champ C. M., Temple S. E., and Michiels N. K. (2017). Red fluorescence of the triplefin Tripterygion delaisi is increasingly visible against background light with increasing depth. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 4161009. doi: 10.1098/rsos.161009

Bitton P. P., Yun Christmann S. A., Santon M., Harant U. K., and Michiels N. K. (2019). Visual modelling supports the potential for prey detection by means of diurnal active photolocation in a small cryptobenthic fish. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44529-0

Blumstein D. T., Cooley L., Winternitz J., and Daniel J. C. (2008). Do yellow-bellied marmots respond to predator vocalizations? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiology 62, 457–468. doi: 10.1007/s00265-007-0473-4

Bronmark C. and Hansson L. (2000). Chemical communication in aquatic systems : an introduction. Oikos 88, 103–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880112.x

Brooks M., Kristensen K., van Benthem K., Magnusson A., Berg C., Nielsen A., et al. (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 9, 378–400. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066

Brown C. and Warburton K. (1997). Predator recognition and anti-predator responses in the rainbowfish Melanotaenia eachamensis. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiology 41, 61–68. doi: 10.1007/s002650050364

Brown G. E. (2003). Learning about danger: chemical alarm cues and local risk assessment in prey fishes. Fish Fisheries 4, 227–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2979.2003.00132.x

Bruckstein A., Holt R. J., Katsman I., and Rivlin E. (2005). Head movements for depth perception: praying mantis versus pigeon. Autonomous Robots 18, 21–42. doi: 10.1023/B:AURO.0000047302.46654.e3

Calhoun A. C., Tobin K. B., Poorboy D. M., Bowden R. M., and Sadd B. M. (2025). To bob or not to bob: Context-dependence of an antipredator response in neotropical harvestmen. Behav. Ecol. 36, 2. doi: 10.1093/beheco/araf004

Campbell H. (2021). The consequences of checking for zero-inflation and overdispersion in the analysis of count data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 665–680. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13559

Chivers D. P., Mirza R. S., Bryer P. J., and Kiesecker J. M. (2001). Threat-sensitive predator avoidance by slimy sculpins: understanding the importance of visual versus chemical information. Can. J. Zoology 079, 867–873. doi: 10.1139/z01-049

Chivers D. P. and Smith R. J. F. (1998). Chemical alarm signalling in aquatic predator-prey systems: A review and prospectus. Ecoscience 5, 315–321. doi: 10.1080/11956860.1998.11682471

Coates D. (1980). The Discrimination of and Reactions towards Predatory and Non-predatory Species of Fish by Humbug Damselfish, Dascyllus aruanus (Pisces, Pomacentridae). Z. für Tierpsychologie 52, 347–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1980.tb00722.x

Compaire J. C., Casademont P., Cabrera R., Gómez-Cama C., and Soriguer M. C. (2018). Feeding of Scorpaena porcus (Scorpaenidae) in intertidal rock pools in the Gulf of Cadiz (NE Atlantic). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 98, 845–853. doi: 10.1017/S0025315417000030

Friard O. and Gamba M. (2016). BORIS: a free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1325–1330. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12584

Fritsch R., Ullmann J. F. P., Bitton P. P., Collin S. P., and Michiels N. K. (2017). Optic-nerve-transmitted eyeshine, A new type of light emission from fish eyes. Front. Zoology 14, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12983-017-0198-9

Geiger N., Hirschkorn C., Herberstein M. E., Roald-Arbol M., and Rößler D. C. (2025). Context-dependent abdomen bobbing in a jumping spider: a dynamic visual signal. doi: 10.1101/2025.10.01.679781

Gerlai R. (1993). Can paradise fish (Macropodus opercularis, anabantidae) recognize a natural predator? An ethological analysis. Ethology 94, 127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1993.tb00553.x

Gibson E. J., Gibson J. J., Smith O. W., and Flock H. (1959). Motion parallax as a determinant of perceived depth. J. Exp. Psychol. 58, 40–51. doi: 10.1037/h0043883

Graw B. and Manser M. B. (2007). The function of mobbing in cooperative meerkats. Anim. Behav. 74, 507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.11.021

Greene N. R. and Filko B. J. (2010). Animal-eyeball vs. road-sign retroreflectors. Ophthalmic Physiol. Optics 30, 76–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2009.00688.x

Haddock S. H. D. and Dunn C. W. (2015). Fluorescent proteins function as a prey attractant: Experimental evidence from the hydromedusa OlIndias formosus and other marine organisms. Biol. Open 4, 1094–1104. doi: 10.1242/bio.012138

Harant U. K., Michiels N. K., Anthes N., and Meadows M. G. (2016). The consistent difference in red fluorescence in fishes across a 15 m depth gradient is triggered by ambient brightness, not by ambient spectrum. BMC Res. Notes 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1911-z

Harant U. K., Santon M., Bitton P. P., Wehrberger F., Griessler T., and Meadows M. G. (2018). Do the fluorescent red eyes of the marine fish Tripterygion delaisi stand out? In situ and in vivo measurements at two depths. Ecol. Evol. 8, 4685–4694. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4025

Hardin J. W. and Hilbe J. (2012). Generalized Linear Models and Extensions, 3rd Edition. (StataCorp LP). Available online at: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:tsj:spbook:glmext (Accessed December 04, 2022).

Hartman E. J. and Abrahams M. V. (2000). Sensory compensation and the detection of predators: The interaction between chemical and visual information. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 267, 571–575. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1039

Helfman G. S. (1989). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Threat-sensitive predator avoidance in damselfish-trumpetfish interactions. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol 24, 47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00300117

Hellinger J., Jägers P., Donner M., Sutt F., Mark M. D., and Senen B. (2017). The flashlight fish anomalops katoptron uses bioluminescent light to detect prey in the dark. PloS One 12, 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170489

Hettena A. M., Munoz N., and Blumstein D. T. (2014). Prey responses to predator’s sounds: A review and empirical study. Ethology 120, 427–452. doi: 10.1111/eth.12219

Hettyey A., Tóth Z., Thonhauser K. E., Frommen J. G., Penn D. J., and Van Buskirk J. (2015). The relative importance of prey-borne and predator-borne chemical cues for inducible antipredator responses in tadpoles. Oecologia 179, 699–710. doi: 10.1007/s00442-015-3382-7

Howland H. C., Murphy C. J., and Mccosker J. E. (1992). Detection of eyeshine by flashlight fishes of the family anomalopidae. Vision Res. 32, 765–769. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90191-K

Janssen J. (2004). “Lateral line sensory ecology,” in The Senses of Fish: Adaptations for the Reception of Natural Stimuli. (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht), 231–264. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-1060-3_11

John L., Santon M., and Michiels N. K. (2023). Scorpionfish rapidly change colour in response to their background. Front. Zoology 20, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12983-023-00488-x

Kalb N., Schneider R. F., Sprenger D., and Michiels N. K. (2015). The Red-Fluorescing Marine Fish Tripterygion delaisi can Perceive its Own Red Fluorescent Colour. Ethology 121, 566–576. doi: 10.1111/eth.12367

Kats L. B. and Dill L. M. (1998). The scent of death: chemosensory assessment of predation risk by prey animals. Ecoscience 5, 361–394. doi: 10.1080/11956860.1998.11682468

Kenaley C. P., Devaney S. C., and Fjeran T. T. (2014). The complex evolutionary history of seeing red: Molecular phylogeny and the evolution of an adaptive visual system in deep-sea dragonfishes (stomiiformes: Stomiidae). Evolution 68, 996–1013. doi: 10.1111/evo.12322

Kerfoot W. C. and Sih A. (1987). Predation : direct and indirect impacts on aquatic communities (University Press of New England). Available online at: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1971149384740911811.bib?lang=en (Accessed October 14, 2025).

Kobayashi T., et al. (2004). Electrical and mechanical properties and mode of innervation in scorpionfish sound-producing muscle fibres. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 3757–3763. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01206

Kral K. (2003). Behavioural-analytical studies of the role of head movements in depth perception in insects, birds and mammals. Behav. Processes 64, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(03)00054-8

Louisy P. (2015). Europe and Mediterranean marine fish identification guide. (Paris, France: Ulmer).

McCormick M. I. and Manassa R. (2008). Predation risk assessment by olfactory and visual cues in a coral reef fish. Coral Reefs 27, 105–113. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0296-9

Michiels N. K., Anthes N., Hart N. S., Herler J., Meixner A. J., Schleifenbaum F., et al. (2008). Red fluorescence in reef fish: A novel signalling mechanism? BMC Ecol. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-8-16

Michiels N. K., Seeburger V. C., Kalb N., Meadows M. G., Anthes N., Mailli A. A., et al. (2018). Controlled iris radiance in a diurnal fish looking at prey. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5, 170838. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170838

Murphy K. and Pitcher T. (2005). Predator attack motivation influences the inspection behaviour of European minnows. J. Fish Biol. 50, 407–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01368.x

Neiße N., Santon M., Bitton P. P., and Michiels N. K. (2020). Small benthic fish strike at prey over distances that fall within theoretical predictions for active sensing using light. J. Fish Biol. 97, 1201–1208. doi: 10.1111/jfb.14502

Nelson M. E. and MacIver M. A. (2006). Sensory acquisition in active sensing systems. J. Comp. Physiol. A: Neuroethology Sensory Neural Behav. Physiol. 192, 573–586. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0099-4

Neumeyer C., Dörr S., Fritsch J., and Kardelky C. (2002). Colour constancy in goldfish and man: Influence of surround size and lightness. Perception 31, 171–187. doi: 10.1068/p05sp

Poding L. H., Jägers P., Herlitze S., and Huhn M. (2024). Diversity and function of fluorescent molecules in marine animals. Biol. Rev. 99, 1391–1410. doi: 10.1111/brv.13072

Preisser E. L., Bolnick D. I., and Benard M. E. (2005). Scared to Death ? The Effects of Intimidation and Consumption in Predator-Prey Interactions. Ecology 86, 501–509. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3450969.

Radford C. A., et al. (2012). Pressure and particle motion detection thresholds in fish: A re-examination of salient auditory cues in teleosts. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3429–3435. doi: 10.1242/jeb.073320

R Core Team (2024). “R: A language and environment for statistical computing.” (Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.r-project.org/ (Accessed March 12, 2025).

Santon M., Bitton P. P., Harant U. K., and Michiels N. K. (2018). Daytime eyeshine contributes to pupil camouflage in a cryptobenthic marine fish. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25599-y

Santon M., Bitton P. P., Dehm J., Fritsch R., Harant U. K., Anthes N., et al. (2020). Redirection of ambient light improves predator detection in a diurnal fish. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 287, 20192292. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2292

Santon M., Deiss F., Bitton P. P., and Michiels N. K. (2021). A context analysis of bobbing and fin-flicking in a small marine benthic fish. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1254–1263. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7116

Santon M., Korner-Nievergelt F., Michiels N. K., and Anthes N. (2023). A versatile workflow for linear modelling in R. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2023.1065273

Schielzeth H. and Forstmeier W. (2009). Conclusions beyond support: Overconfident estimates in mixed models. Behav. Ecol. 20, 416–420. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arn145

Schwab I. R., Yuen C. K., Buyukmihci N. C., Blankenship T. N., Fitzgerald P. G., Eagle R. C., et al. (2002). Evolution of the tapetum. Trans. Am. Ophthalmological Soc. 100, 187–200.

Smith R. J. F. (1989). The Response of Asterropteryx semipunctatus and Gnatholepis anjerensis (Pisces, Gobiidae) to Chemical Stimuli from Injured Conspecifics, an Alarm Response in Gobies. Ethology 81, 279–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1989.tb00774.x

Smith M. E. and Belk M. C. (2001). Risk assessment in western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis): Do multiple cues have additive effects? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiology 51, 101–107. doi: 10.1007/s002650100415

Sutton T. T. (2005). Trophic ecology of the deep-sea fish Malacosteus Niger (Pisces: Stomiidae): An enigmatic feeding ecology to facilitate a unique visual system? Deep-Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Papers 52, 2065–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2005.06.011

Warrant E. J. and Johnsen S. (2013). Vision and the light environment. Curr. Biol. 23, R990–R994. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.019

Wilkins L., Marshall N. J., Johnsen S., and Osorio D. (2016). Modelling colour constancy in fish: Implications for vision and signalling in water. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 1884–1892. doi: 10.1242/jeb.139147

Wirtz P. (1978). The behaviour of the Mediterranean ttipterygion species. Z. für Tierpsychologie 48, 142–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1978.tb00253.x

Wisenden B. D. (2000). Olfactory assessment of predation risk in the aquatic environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 355, 1205–1208. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0668

Wisenden B. D. and Harter K. R. (2001). Motion, not shape, facilitates association of predation risk with novel objects by fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas). Ethology 107, 357–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2001.00667.x

Wucherer M. F. and Michiels N. K. (2012). A fluorescent chromatophore changes the level of fluorescence in a reef fish. PLoS One 7, 6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037913

Wucherer M. F. and Michiels N. K. (2014). Regulation of red fluorescent light emission in a cryptic marine fish. Front. Zoology 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-11-1

Keywords: fluorescence, behavioural ecology, evolutionary ecology, predatory-preydynamics, active sensing

Citation: van der Schoot BKM and Michiels NK (2025) Improved predator detection through illumination with red fluorescence by a small benthic fish. Does it work? Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1728992. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1728992

Received: 20 October 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Wayne Iwan Lee Davies, Umeå University, SwedenReviewed by:

Jon Vidar Helvik, University of Bergen, NorwayJessica Kate Mountford, University of Western Australia, Australia

Copyright © 2025 van der Schoot and Michiels. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bram K. M. van der Schoot, YnJhbS5zY2hvb3RAdW5pLXR1ZWJpbmdlbi5kZQ==

Bram K. M. van der Schoot

Bram K. M. van der Schoot Nico K. Michiels

Nico K. Michiels