- School of Education, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Objective: Transition from primary school to secondary school is an important point in a young person's development. Children's experiences at transition have been found to have an enduring impact on their social and academic performance and potentially their success or failure at secondary school. This primary-secondary transition frequently presents challenges for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), resulting in uncertainty and anxiety. The objective of this study was to explore the perceptions of children with ASD, on the topic of which features of school environment fit more or less well with their needs, as they transferred from primary to secondary schools.

Method: Semi-structured interviews were used to gather the experiences of 6 students with ASD, and their parents, before and after the transition to secondary school. A thematic analysis of these data identified common themes that captured the fits and misfits between the children's needs and their primary and secondary school environments.

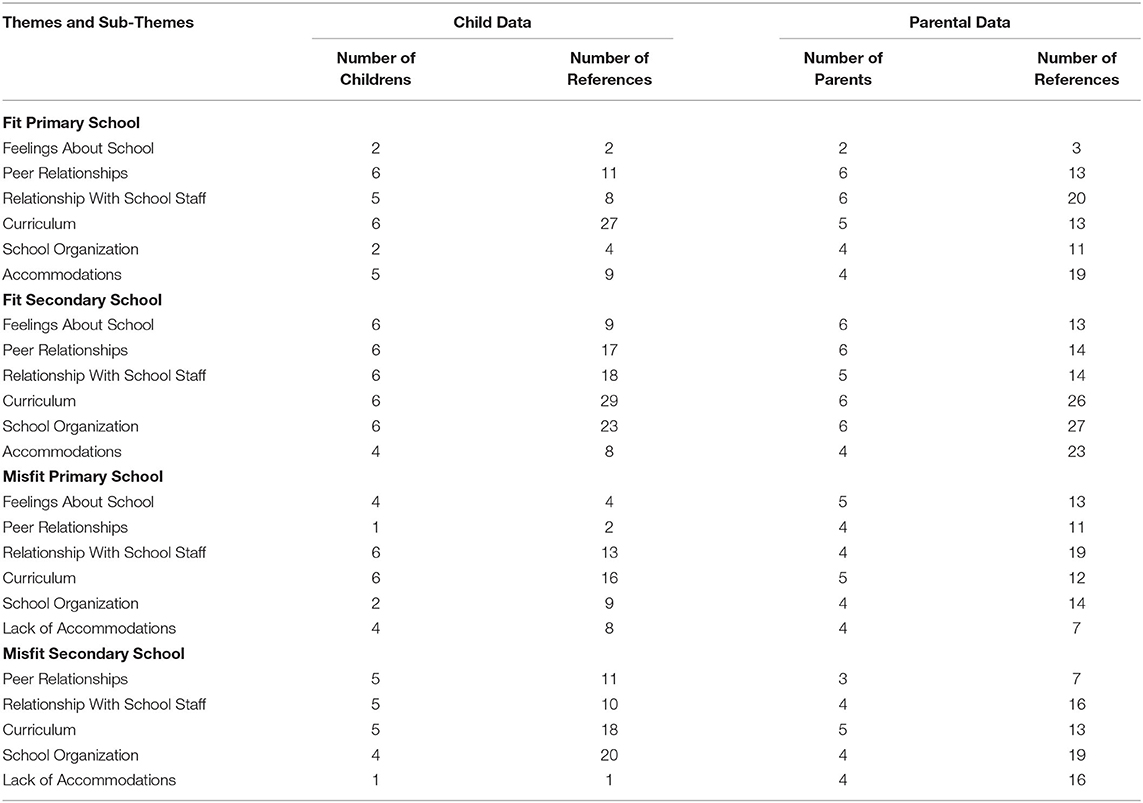

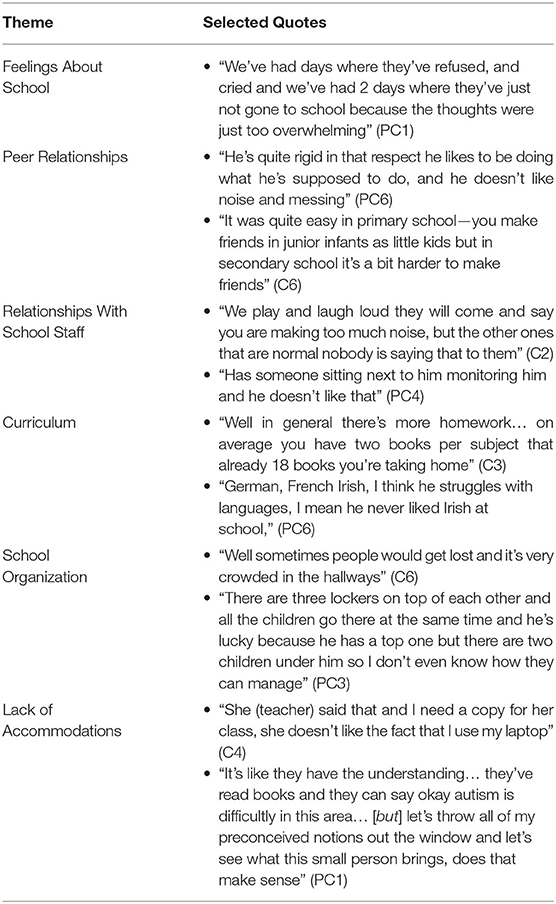

Result: Overall, participants voiced more positive perspectives of secondary school than primary school. Data analysis identified themes of feelings about school, peer relationships, relationship with school staff, curriculum, school organization, and accommodations.

Conclusion: Inclusion and integration of students with ASD in mainstream secondary schools at transition can be a positive experience when the school environments are a good fit with the individual needs of each child with ASD. The transition can be challenging for children when a one size fits all approach is taken.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by enduring deficits in social communication and social interaction in addition to patterns of restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities across multiple contexts (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). ASD is a spectrum condition, and the wide-ranging presentations of ASD result in significant disparities in functional characteristics from one individual to another and variable levels of performance across domains (Powell et al., 2018).

Transition from primary to secondary school represents a significant milestone in a child's educational career. As a group, children with ASD have been identified as particularly vulnerable sto difficulties at this period, given their identified challenges with managing transitions (Makin et al., 2017). There is a dearth of research in an Irish context regarding the transition experience of Irish students with ASD. Previous research in other countries concerning ASD and the primary-secondary transition has focused on the perspectives and experiences of pupils and stakeholders on the transition process, and corresponding supports available to students (Hoy et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2019b). Relatively few studies have considered the change that students experience in the specific features of school environments, and the suitability of the school environments to meet the needs of the individual students with ASD at school transition. Information about the characteristics of school environments that favor or support students with ASD could help inform decisions regarding school placement. Additionally, this information could help inform school practices regarding supporting students with ASD around transitions.

This study aimed to expand on previous knowledge regarding the primary-secondary transition for children with ASD by evoking parents' and children's views of the features of school environment before and after school transition, that were considered to be a fit or misfit with the children's psychosocial needs.

Primary-Secondary Transition

A large volume of research has examined issues relating to transition from primary school to secondary school for all students (Bloyce and Frederickson, 2012; Jindal-Snape, 2016). A consistent finding is a decline in students' educational outcomes, motivation and engagement (Jindal-Snape et al., 2019). Another common theme is how relationships with peers and teachers positively or negatively impact students' adaptation after transition (Jindal-Snape et al., 2019). Perceived teacher support is associated with students' motivation and perceptions of a positive school climate after transition (Hanewald, 2013). Support from peers at transition is a protective factor, and peers have considerable influence in shaping children's attitudes about transition before the move (Waters et al., 2014).

Transition preparation has been identified as an essential factor in determining the success of the transition. While cooperation between schools is important, the role of the secondary school in the preparation process is emphasized (Evangelou et al., 2008). Additional notable influences include continuity of the curriculum in secondary school and adjusting to the demands of social relationships (Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). The importance of including and enabling students at the transition has also been emphasized (Hebron, 2017a). Relational and academic supports in schools (e.g., positive teacher-student relationships, and the curriculum taught by subject specialists) have been identified as a protective factor for children's mental and emotional well-being at transition (Lester and Cross, 2015). Criticism of existing transition research is the tendency to focus on the negative aspects of the process as opposed to providing a more balanced outlook (Topping, 2011). In outlining the primary-secondary transition as an ongoing process, the lack of formal training for primary and secondary teachers in supporting children during transition has been highlighted (Jindal-Snape and Cantali, 2019).

Transition and School Fit

School fit has been described as the match between a student's school, and their psychosocial needs (e.g., for emotional support, self-esteem, competence, and autonomy) (Bahena et al., 2016). Stage environment fit (SEF) theory (Eccles and Midgley, 1989) drew from person-environment interaction (PEI) theory (Hunt, 1975) to explore the impact of transitions on adolescent development (Eccles and Roeser, 2009). SEF theory suggests that change in students' attitudes to school following transition is not necessarily a feature of the move itself, but is the result of a mismatch between the emotional, cognitive and social needs of the individual student and the environment of the school to which they transition (Eccles and Roeser, 2009). A systematic review of adolescent psychological development at school transition identified several of these key person-environment interactions that influence children's psychosocial functioning and well-being (Symonds and Galton, 2014). These interactions included the fit or misfit between the child's needs for safety, relatedness, autonomy, competency, enjoyment and identity development, and their experiences of teachers and peers, school environment, curriculum, and pedagogy.

Primary—Secondary Transition for Children With ASD

Considering the key characteristics of ASD such as difficulties with change, rigid thinking styles, social interaction difficulties, and sensory challenges, it is not unusual that students with ASD can be particularly vulnerable transferring to a new school (Richter et al., 2019b). Given the variability in the presentation of ASD (Fletcher-Watson and Happé, 2019), previous research has found considerable heterogeneity within the transition requirements of students with ASD (Dillon and Underwood, 2012; Fortuna, 2014; Richter et al., 2019a). Although such students are at considerably higher risk of complications during the primary-secondary transition, these risks can be mitigated by environmental or familial protective factors (Hannah and Topping, 2013).

Accordingly, the psychosocial outcomes of school transition for students with ASD are mixed in the literature. Some of these students have reported experiences of transition that were positive and better than anticipated (Hannah and Topping, 2013; Fortuna, 2014), and in line with their typically developing counterparts (Zeedyk et al., 2003). Differences have been observed between the positive experiences of those transferring to a specialist ASD provision, or to a supportive mainstream setting, compared to the negative experiences of those moving to mainstream with no support (Dann, 2011). However, others have reported a fundamentally negative experience of transition regardless of the type of provision to which a student was transferring (Makin et al., 2017).

A systematic review applying Evangelou et al.'s (2008) criteria for transition success found that, while transition concerns for students with ASD were equivalent to their typically developing peers, their ASD diagnosis added a layer of complexity to the transition (Richter et al., 2019b). This research identified that, in addition to typical transition concerns, specific issues related to the transition of students with ASD, such as transition planning, student-teacher relationships, and teacher well-being (Richter et al., 2019b). The importance of transition planning cannot be understated with a personalized approach unique to each individual student with ASD being a necessity (Hebron, 2017b). Because of the importance of systems-level factors, such as delays in identifying placement, and poor transition planning at primary level, on students' positive adaptation after school transition, it is essential to ensure a good fit between the student with ASD and their school environment both before, during and after the transition (Makin et al., 2017).

Parent and Child Perspectives

Although parents have been identified as playing a pivotal role in supporting a child's transition (Stoner et al., 2007), there is limited research on parents' perspectives of their children's transition from primary to secondary (Dillon and Underwood, 2012). Similarly, parents' perceptions of school fit at transition within existing research literature is sparse, which is surprising given they are uniquely placed to offer valuable insight into their child's needs, given their knowledge of their children across various environments and developmental stages (Bahena et al., 2016). Additionally, including children's first-person accounts of transferring between schools with ASD is important for building the evidence base. This is critical because these children are the experts on ASD and are less likely than non-autistic people to view ASD through a deficit defined lens (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2017). Including the perspectives of children on their transition experiences can help inform practitioners of the appropriate supports required at transition (Hannah and Topping, 2013).

Educational Provision for Students With ASD in Ireland

Similar to the United Kingdom, most children in Ireland enter secondary school at age 12 after attending primary school for 8 years. This timing roughly equates to the transfer to from middle school to high school in the United States. Secondary school (or post-primary school) finishes at around age 18/19 years in Ireland. The Irish school system is not differentiated by ability (there are no tracked schools) and children with mild to moderate special needs are often educated in mainstream schools alongside children without identified special needs.

In Ireland, one in 65 students in schools has been diagnosed with ASD representing 1.55 per cent of the student population (National Council for Special Education, 2016). This calculation is based on school-aged children with ASD in state-funded schools. Government policy and legislation have moved toward a policy of inclusion resulting in an increasing number of students with ASD accessing mainstream education with specialist teaching support or special ASD classes (Parsons et al., 2011).

Within mainstream schools, students are placed in either a special class for ASD or they remain in mainstream classes and generally receive supplementary teaching based of their level of need (McCoy et al., 2020). In Ireland, a special class generally serves the function of a “home room” that children go to when they are not attending subject specialist classes throughout the day. Additionally, children can be assigned access to a Special Needs Assistant where they are deemed to have specific additional needs that require extra support. The department defines these as additional and significant care needs and proposes that SNA support is necessary to enable the pupil to attend school, to integrate successfully with their peers, and to minimize the impact of the behavior of students with SEN on other in the class (McCoy et al., 2014). Currently in Ireland, special ASD classes comprise a staffing ratio of one teacher and a minimum of two special needs assistants (SNAs) for every six children (Daly et al., 2016). ASD classes are in operation at primary and secondary level for students with ASD diagnoses. Students in these classes often have Individual Education Plans (IEPs) and structured timetabled school days with integration in mainstream (where possible) (Daly et al., 2016). In primary school, a considerable discrepancy exists in how the curriculum is delivered within ASD classes (Finlay et al., 2019).

There is no formalized transition to secondary school programme for students with ASD, and transition practices vary from school to school (Daly et al., 2016). While school have been found to engage appropriately with the transition process regarding students with ASD, a need for more evidenced based practice has been identified (Deacy et al., 2015).

The Current Study

This research aimed to explore the perspectives of students with ASD and their parents on their transition from primary to secondary school using the lens of school fit. It is hoped that this comprehensive examination of the interactions between the pupils' needs and the school environment across school transition will help identify environmental adaptations or practices that can better support students with ASD. By considering how the needs of pupils with ASD fit with their environment before and after transition, it could emerge that there are features of the school environment that work better for pupils with ASD at either primary or secondary levels. This knowledge could be used to inform practice at the alternative level (primary or secondary). Additionally, given that previous research has identified the importance of planning for students with ASD, this research will explore parents' and children's perspectives on their transition planning. Finally, it is hoped that a review of the transition experiences from the perspectives of two of the key stakeholders will identify any unnecessary challenges existing within the school environment, which could help inform future policy and procedures for supporting school transitions for students with ASD. The current study is the first study on the lived experiences of Irish children with ASD as they transfer from primary to secondary school, and the following five research questions guided the research:

1. What were the perceived fits between the school environment and the individual child's needs in the last term of primary school?

2. What were the perceived fits between the school environment and the individual child's needs in the first term of secondary school?

3. What were the perceived misfits between the school environment and the individual child's needs in the last term of primary school?

4. What were the perceived misfits between the school environment and the individual child's needs in the first term of secondary school?

5. Which transition planning experiences did the children and parents perceive as being helpful?

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the university to which the researchers are attached. The research complied with ethical guidelines from the Psychological Society of Ireland's (PSI) Code of Professional Ethics (Psychological Society of Ireland, 2019), and the PSI's Guidelines on Confidentiality and Record-Keeping in Practice (Psychological Society of Ireland, 2011). Written informed consent was obtained from adult participants and assent was obtained from child participants. The children's assent form was presented in an accessible format, posted in advance of interviews, and administered again before the start of the interview to ensure comprehension and agreement. Given the debate in the ASD literature concerning person-first language vs. identity-first language, the participants indicated how they would like to be described in the research through a questionnaire administered immediately before the second interview.

Six children (one girl, five boys) with ASD and their parents were recruited from a service providing diagnostic and intervention services to children with ASD attending mainstream schools. Participant inclusion criteria were that children had to (1) be transferring from a mainstream primary school to a mainstream secondary school within the service's locality; (2) have received a clinical diagnosis from a multidisciplinary team of an autistic spectrum disorder (including autistic disorder and Asperger Syndrome), according to international classification instruments; and (3) not have a diagnosed intellectual disability.

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling. A single local multidisciplinary service was chosen to recruit participants from, because of an existing working relationship between the service and the first author. This relationship allowed the first author to seek additional guidance and resources from the service, if so required, when researching with the vulnerable children. Information about the study was distributed by the service clinicians to all parents of children with a diagnosis of ASD within the service who were attending the last year of a mainstream primary school. A total of six mothers self-selected for their children to participate in the study.

The six children had a diagnosis of ASD according to ICD-10 criteria: three with Asperger's Syndrome and three with Childhood Autism. Two children had a history of school refusal; one had changed primary schools, and the other had a reduced school day. No child attended the same school as another child in the study. The schools were in both rural and urban locations. Three children were transferring from mainstream primary to mainstream secondary school, two were transferring from a mainstream special class in primary school to a special class in mainstream secondary school, and one was transferring from a mainstream primary class to a special class in mainstream secondary school. All the children had IQ scores reported in the Average Range or higher in their most recent cognitive assessments. None of the children were accessing supports for Speech and Language difficulties beyond the communication difficulties associated with ASD. See Table 1 for a detailed profile of each young person.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author in the final term of primary school, and again 8 weeks into the first term of secondary school. The interviews were conducted in quiet environments, at either the multidisciplinary service (n = 2) or at the participants' homes (n = 4) and were of 20 to 30 min duration. The first author followed recommendations on conducting semi-structured interviews with families living with ASD (Cridland et al., 2015). Interviews were audio recorded and all audio recordings were transcribed by the first author.

Many considerations were considered within the interview process given the vulnerable nature of young people with ASD in an attempt to ensure the validity of the data. Participants were given the option of having a familiar adult present to reduce anxiety (Fayette and Bond, 2018). Only one child requested a parent to be present for one interview. The researcher asked open-ended, non-leading questions, and reassured the child from the outset that there were no right or wrong answers (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2015). To ensure reliability in the research, the same interview schedule and interviewer were utilized throughout the study.

Interview Schedules

Semi-structured interviews were chosen given their ability to elicit rich information through discourse, flexible structure, and assistance in developing rapport with the participants (Martin et al., 2019). Interview questions were structured around the notions of fit and misfit between features of the school environment and the developing child, before and after transition (Eccles and Midgley, 1989). The questions asked children and parents their views on which features of school elicited positive emotions in the child (e.g., liking and interest) and negative emotions in the child (e.g., disliking and boredom), and on which features of school fit well or misfit with the child as a person. The same question topics were repeated for children and parents, before and after transition. Additional questions on how well the child had settled into secondary school were included in the post-transition interview schedule.

To ensure that the questions worked well for the participants, they were reviewed by experts in ASD (a first-year college student with ASD and members of a multidisciplinary services team). This resulted in each question being presented separately on a card to the child participant, as well as the questions being asked aloud to help reduce anxiety and enable the child to remember each question. Draft interview schedules were piloted with one child with ASD and his mother, in his first year of secondary school.

Analysis Plan

A total of 24 interviews were conducted: with the six children before, and after transition (n = 12), and with the six mothers before and after transition (n = 12). NVivo version 12 was used to analyse the interview transcripts. The data from parents and children were pooled into sets representing views on fit and misfit before and after transition, and each set was analyzed separately using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2012). Data were firstly coded as fit or misfit based on positive or negative comments or observations, then the data were coded inductively within these frameworks. For the purposes of anonymity all participants will be referred to as “hey” in the analysis.

Results

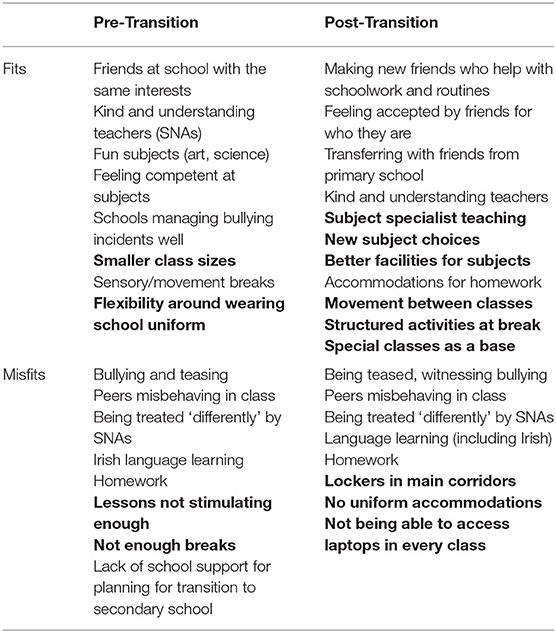

The results section is organized by fits and misfits at primary and secondary school. Within each section we have summarized the main results by theme. Tables 2–5 contain quotes from participants to illustrate these findings with the voices of parents and children. We have also summarized the main fits and misfits in Table 6, with attention paid to the discontinuities (identified differences in experience) between primary and secondary schooling.

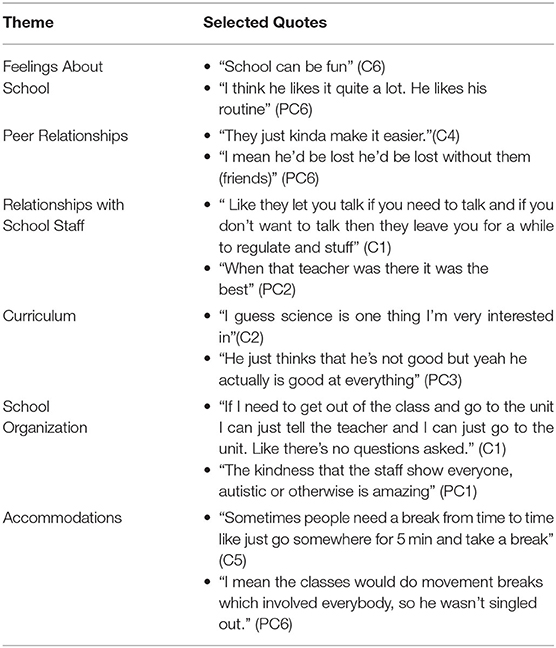

Perceived Fits in Primary School

Across the parent and child interviews, six themes emerged that suggested a fit between the child and their primary school environment. See Table 1 on page 19 outlining the number of participants and number of participant references per theme at each time point.

Fit 1: Feelings About Primary School

Two of the six children and their parents identified that the children liked their primary school. The parents acknowledged that while there were “stressors” for their children in school, the children were happy at school and generally liked going there. The two children discussed how they liked school and that it was “fun” sometimes.

Fit 2: Peer Relationships at Primary School

All six children and five parents discussed positive aspects of the child's relationships with their peers in primary school. Children spoke about how they had friends in school they could relate to with the same interests, with some identifying their friends as being the best thing about school. For some of the children who found school difficult, peers were a source of comfort in the yard or for helping understand the teachers' instructions. One parent disclosed that contact with peers was the thing that encouraged their child to go to school most days.

Fit 3 Relationships With Primary School Staff

Five parents and three children spoke about the importance of having teachers who understood the children and their needs. Most of these children and parents referred to support teachers or Special Needs Assistants (SNAs) rather than class teachers in this regard. Children explained the importance of having someone to help them solve problems and talk things through. Three parents reported that when their child had a positive relationship with the class teacher, the stress levels at home decreased. Parents explained that when teachers or staff took the time to understand the child and their needs, it preempted issues before they arose. Parents did not generally describe the teachers in terms of how well they understood ASD; instead they represented the teachers as being “kind” and “supportive.” One parent whose child was having a particularly difficult time in school acknowledged that having one person in the school who was seen as a “safety person” by the child made life easier for both her and her child. Another parent described the difficulties in getting their child to school every day, and how when they were late, they would meet the principal. He would greet them with small talk and chat, as opposed to berating the child for being late, which he understood would only exacerbate the problem.

Fit 4: Primary School Curriculum

All students and five parents were able to identify at least one subject that the child was good at in primary school. Three parents referred to their children as being good academically, and four students described themselves as being “good at maths.” Three students liked Art, PE, and Science, describing Science as “interesting” and Art and PE as “fun.” Two students found English interesting.

Fit 5: Primary School Organization

Parents described the importance of issues such as bullying being dealt with as they arose, as they felt this had the effect of making the child feel safe in school. One student who had changed schools following a period of school refusal described “feeling safe” in the new primary school as they navigated the school day between the mainstream and special class. Another student outlined how they were happy that there were three final year classes in their school, as this meant the class sizes were smaller at around 20 per class. Two parents spoke about how all children were treated equally in the school regardless of diagnosis.

Fit 6: Accommodations at Primary School

Five children identified that access to sensory or movement breaks greatly helped them engage with learning and school generally. Students described how movement or a break from the class helped them “concentrate” and described themselves as “refreshed” after this break. Four parents also emphasized the importance of these breaks, and spoke about how teachers incorporated these breaks into the class routine. Three parents talked about the value of having a space for their child to access when they needed it. Three parents outlined how the school had accommodated their child with the provision of either a physical space or by having an identified person they could approach. Finally, two parents described sensory difficulties their child had concerning the school uniform and acknowledged that their school had been very accommodating in allowing them flexibility with the wearing of the uniform.

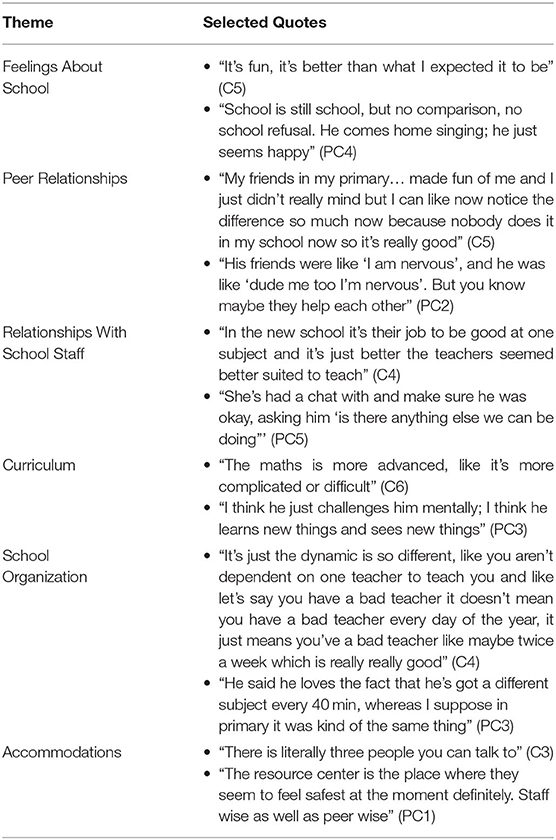

Perceived Fits in Secondary School

The post-transition data fit well into the same broad pattern of themes as the pre-transition data, regarding fits between the children and the school environment.

Fit 1: Feelings About Secondary School

All parents and children reported positive experiences of secondary schooling post-transition. Most parents and children explained that secondary school was better than primary school and had exceeded expectations in some cases. One child reported that they liked secondary school but was also struggling with aspects of the school day, and therefore admitted that they had mixed feelings overall. All the parents were assured that their children had adapted to the new schools, with some admitting that, although the child had been initially more enamored, and the “novelty had worn off,” the child still liked school and was happy to attend.

Fit 2: Peer Relationships at Secondary School

All of the children and most of the parents spoke about the importance of peers in secondary school. Five parents talked about the new friends their children had made in their new schools. Parents also communicated about how the friends appeared to be supporting each other in terms of reassuring each other, understanding homework and understanding teacher instructions. Children and some parents highlighted that the children felt a level of acceptance from their new friends that had not been present in primary school. Some children spoke about the reassurance of having understanding friends or peers who had transferred with them from primary school.

Fit 3 Relationship With Secondary School Staff

This theme was much more salient for the children than their parents. All of the children identified teachers that they found “funny,” “kind,” “genuine,” and “interesting.” Some children remarked how teachers had more in-depth knowledge of their subjects in secondary and in some cases reported a shared interest with their teachers. Three children felt that their teachers gave explicit instructions which they found reassuring. Parents felt that the staff were “kind and caring” and two parents noted that teachers appeared to be “checking in” with their child throughout the day to preempt difficulties before they arose.

Fit 4: Secondary School Curriculum

For nearly all parents and children, the introduction of new subject choices at secondary school was a positive feature. All the children who had the option of the technical subjects (i.e., woodwork and metalwork) reported enjoying them. Parents and students acknowledged that subjects seemed to have more depth in secondary school which made them more appealing. For parents, this contributed to their child being more challenged than they had been in primary school. Two students identified PE as being much better, with one remarking that access to gym equipment facilitated more meaningful movement breaks than primary school. In terms of competency, all students and parents identified at least one subject the children were good at in secondary school. Parents were a little less sure than their children as they felt it is still “early days” and many had not had results from the school yet. Some children acknowledged that, in some subjects, they were revising work already covered at primary, but they were reassured by this. Some of the children accessed support classes during their school day to help complete some of their homework. Other children remarked that they liked that homework did not always have to be completed the day it was assigned in secondary. These children identified these accommodations for doing homework as a big positive to secondary school.

Fit 5: Secondary School Organization

For the children, there appeared to be many aspects of the secondary school environment that were more favorable than at primary school. Children outlined that they liked the opportunities for additional movement when moving between classes and having different teachers. For some children, the rules at secondary appeared more reasonable than primary. For many of the children, the experience of break time was significantly improved; children could attend structured lunchtime activities such as camera club, or the library or find a quieter space away from the crowds if they wished. The children in the sample felt this provided them with a “freedom” they did not have in primary school. Parents commented that they thought their child felt safer in school and that generally, the ethos of their child's secondary school was well-matched with their needs.

Fit 6: Secondary School Accommodations

Interestingly, this theme was not as salient for the children as it had been in primary school, as it appears that the child's need for movement breaks were reasonably satisfied by moving classes. Three children identified the folders that their schools use to organize their books and materials as being helpful. Many parents and children emphasized the importance of having a designated place or a person available for times of stress and anxiety. Parents appeared satisfied with the level of support their children were receiving at secondary school, feeling that there was a “team of staff” supporting their child. For the children accessing a special class at secondary school, having their lockers and individual workstation in the base class was a welcome resource.

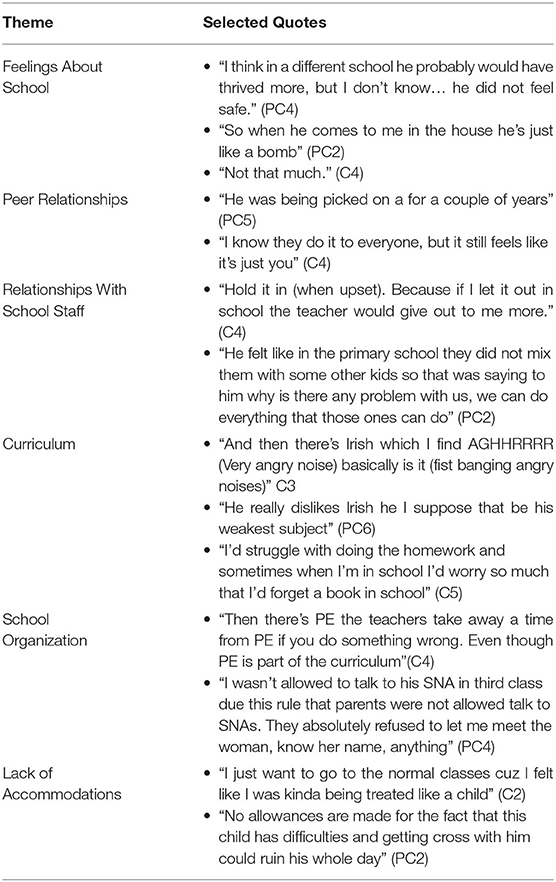

Perceived Misfits in Primary School

Regarding misfits, the data readily converged into the same six themes that were found for fits between school environment and children's needs.

Misfit 1: Feelings About Primary School

Four parents acknowledged that their child did not like school, with two describing a long history of school refusal. Three of the parents spoke about how the distress caused by school attendance permeated into their child's home life. One parent described it as “horrendous,” how her child “cried every day for years; it was horrific!”. Other parents talked about how their child needed time every evening to “decompress.” The parent of one child who stated that they liked school, spoke about how their mood started to deteriorate on Sunday afternoon in anticipation of the return to school. The children were less clear, with two describing being ambivalent toward school with their feelings changing day to day, and another two being very clear that there was nothing about school they liked at all.

Misfit 2: Peer Relationships at Primary School

The issues of peer relationships negatively impacting the child were more salient for the parents than the students. Two children described incidences of peers being “annoying” for touching their belongings or teasing. Three parents described occurrences of their child being bullied, with the bullying going unaddressed by the school for many years. Parents also spoke about the difficulties their children had in managing friends' poor behavior in the classroom and how the unpredictability of this behavior led to increased anxiety and problems negotiating the relationships.

Misfit 3: Relationship With Primary School Staff

Four out of the six children spoke about difficulties in their interactions with their teachers. Some children spoke about having difficulty understanding instructions in the classrooms. Two children and three parents emphasized how the children had been treated differently to their typically developing peers because of their diagnosis of ASD. Both parents (3) and the children (3) described ‘not feeling heard' or “believed,” and as a result often no longer reported issues to the school, as they did not expect their problems to be addressed. Children and parents highlighted the importance of “trust” for the young people with ASD in the sample. They needed to be sure that the staff member was consistent with their commitments. Parents spoke about difficulties with the relationship between their child and the SNA, with the child seeking more freedom and independence from being “followed by the SNA.”

Misfit 4: Primary School Curriculum

Irish represented the biggest challenge for all parents and children in the study, who were studying the subject (two students had exemptions from studying Irish). Children spoke about how they could not understand Irish and reported that it made no sense and how they could not understand why everyone in the class was more proficient than them with the subject. Homework was identified as another significant stressor for three children and two parents. Four children also stated that they were not interested in maths, or that most of the subjects had no meaning and were repetitive. One parent also felt that there was not enough stimulation within the academic content for their child in primary school.

Misfit 5: Primary School Organization

Children and parents expressed concern about the rigidity of some of the primary school and classroom rules, remarking how flexibility is expected from children with ASD. However, the school system does not allow for flexibility when dealing with students with additional needs. Half of the parents mentioned the sensory challenges in the school environment, such as desks seated too close to each other, students cramped together for noisy assembly and wearing an uncomfortable uniform. Since the children in the special classes had a “place” to go to when overwhelmed, these issues were more prevalent for children in the mainstream environment.

Misfit 6: Lack of Primary School Accommodations

Parents were concerned about the lack of understanding around ASD by primary school support staff, particularly regarding supporting their child's transition to secondary school. In parents' and children's descriptions, there was an inconsistency in the approach taken by primary schools in preparing the child with ASD for secondary school. Some parents also reported the school being reluctant to give the child with ASD special treatment in preparing for school transition. One child who was in the ASD class expressed regret that he was not allowed to spend more time in the mainstream class, and others spoke about the expectations being higher in the mainstream class. Finally, one child and two parents spoke about not accessing breaks from the classroom or having a break scheduled for a particular time, and the child could not access breaks outside of this time regardless of the circumstances.

Perceived Misfits in Secondary School

Across the parent and child interviews, the same dominant six themes best categorized the different types of misfits between the child and their new secondary school environment.

Misfit 1: Feelings About Secondary School

None of the students expressed any entirely negative feelings about secondary school. Only one child in the sample had mixed feelings, and their parent had concerns over whether they would be able to continue in their secondary school.

Misfit 2: Peer Relationships

Parents and children identified other children's misbehavior in class as a problem. These were mainly low-level behaviors such as talking out of turn and messing in class, but the children still reported the behaviors as “annoying.” Additionally, two parents expressed concern that, despite requests beforehand, their children had been separated from the majority of their primary school peers in their new schools. The challenges faced by children with social communication difficulties were evident in children's descriptions of situations of negotiating relationships with their class peers. No child reported experiences of bullying in their new school. However, difficulties in managing incidences of teasing, joking and witnessing other people being bullied were described by parents and children alike.

Misfit 3 Relationships With Secondary School Staff

Three of the children in the sample felt that the SNAs treated them differently from their mainstream peers, which frustrated the children and caused them to reject the support offered by the SNA. The children wanted the same independence as their mainstream peers and rejected being “followed” and “treated like a child.” Children commented that if they did not like the teacher, it impacted on their interest in the subject in question.

Misfit 4: Secondary School Curriculum

Homework remained a source of stress for many of the children, most notably the children in the mainstream classes who did not have access to homework classes in school. Children reported difficulty managing the books, writing homework down from the board and having to do homework at the weekend. While two children in the sample had secured an exemption from Irish at secondary school, languages remained the most challenging subject for many of the children who were studying them, as expressed by both parents and children. Most of the children could identify a subject they found boring.

Misfit 5: Secondary School Organization

The main feature of the secondary school environment reported to concern parents and children alike was the locker system. They emphasized that the lockers were too small, and the locker area was overwhelming. Lockers were noted to be an issue for the children attending mainstream classes exclusively. Unsurprisingly, given the difficulties people with ASD have in processing sensory information, many children and their parents spoke about problems managing busy corridors, locker areas and the associated noises. Transport was an area of difficulty for some children as this significantly increased the length of their school day. Getting used to wearing the new uniform was difficult for some children, particularly those who had uniform accommodations at primary school.

Misfit 6: Lack of Secondary School Accommodations

Most parents and children reported that they had been accustomed to managing the difficulties outlined in the previous section. However, parents and children expressed concern about accessing support. Notably, this was only the parents of children in the mainstream environment. One parent expressed disbelief that her son could not access any of the supports available to children in the ASD center in the school he was attending. For two of the children, difficulties concerning continuity of accessing their laptops was observed. Additionally, parents felt that while the staff in school might have had a general understanding of ASD, some had difficulty applying the information to individual children's needs. This was particularly evident for the children who “masked” their struggles or who did not appear to have overt ASD behaviors.

Helpful Transition Planning Experiences

All the parents and children in the sample reported that they accessed significant transition preparation. For the most part, this consisted of visits to the secondary school. Some children described completing worksheets and workbooks in school that supported the transition. Two children received additional support in terms of color coding books, managing books and understanding timetables. One child described how teachers from a secondary school provided workshops to all the 6th class students in the school over 3 weeks, on organization skills for secondary school. One school produced a specific booklet for all students with additional needs, with crucial information about the school and school environment, including photographs of the support staff. While the children described the workbook and worksheets as helpful, one child emphasized that they did not find them useful because they were about secondary school generally and not about their specific school. “The primary school they don't have papers for the specific school they're just off the main primary stuff about secondary school, so you won't really get much information” (C2).

Both parents and children emphasized the importance of visiting the secondary school before transfer, for reducing much of the impending anxiety around the transition. Most students visited the secondary school twice, but the majority of the students had many more visits. These visits allowed the children to meet other children, meet teachers and support staff, meet their identified contact person, tour the school and familiarize themselves with the surroundings, have their questions answered. One child summed up the importance of these visits

“I usually get anxious and stuff… for example if I were to go into first day of school and wouldn't know what the school would look like, I'd just get butterflies in my tummy and I'd just get all worked up because I wouldn't know what was going on or anything, but when I went to the school to see how it is and stuff it helped a lot because now I'm going to know what to do, so now I won't be as worked up” (C4).

Parents and children also spoke extensively about how the secondary schools delivered a gradual introduction to the school timetable and curriculum after the students started at the end of August. These first few days focused on first-year bonding, information classes on secondary school practices, and familiarization with the timetable. Children also described how the school rules were more relaxed and not fully enforced for the first few weeks until students became acclimatized to the new environment. Some schools had support teams for the incoming first year students comprised of older peers, and this was reported to be very helpful. Generally, the parents and children identified the gradual start with reduced days at the beginning of the school as the most beneficial thing to help them become accustomed to their new school.

Discussion

Six children with ASD and their parents were interviewed in the last term of primary school and again during the first term in secondary school. The interviews elicited their perceptions of the features of primary and secondary school environments that fit or misfit with the individual children's needs. Children and parents also provided their perspectives on the positive and negative aspects of the transition planning process. The results documented several examples of fit and misfit, pre- and post-transition, within the major themes of feelings about school, peer relationships, relationships with school staff, curriculum, school organization, and accommodations. In the discussion, we examine how children's and parents' perceptions of those features of schooling altered across the transition, to summarize the most supportive and problematic features of school environment at transition for children with ASD.

Feelings About School

Research has suggested that for some children with ASD, the experience of transition to secondary school is overwhelmingly positive (Dann, 2011), exceeds expectations (Hannah and Topping, 2013), and allows for optimism regarding the move (Mandy et al., 2016). Similarly, for most children and parents in this study, their feelings about school generally were more positive in secondary school than in primary school. Children reported that they liked secondary better than primary and that it was better than they expected. Encouragement can be obtained from the fact that negative experiences of primary school for many of the children in the sample were not evident in the early stages post-transition to secondary school.

Peer Relationships

Peer relationships are crucial given their impact on student engagement in learning as well as protecting from stress (Topping, 2011; Symonds and Hargreaves, 2014). Despite their difficulties with social understanding and social interactions, and similar to their typically developing peers, many children with ASD are interested in forming friendships and being involved in social groups (Dillon et al., 2016). In the current research, all the participants emphasized the importance of peer relationships before and after the primary-secondary transition. They identified peer supports as playing a significant role in their happiness in school. Similar to previous findings (Richter et al., 2019a), the students and their parents reported feeling generally accepted by peers, with parents remarking on the quality of the friendships. The larger secondary school environment often provides more significant opportunities for developing friendships (Hebron, 2017a).

Relationships With School Staff

Emotionally supportive student-teacher relationships are a protective factor in encouraging student engagement in learning at transition (Symonds and Hargreaves, 2014). They are a critical factor in influencing transition success for students with ASD, whereby difficulties in such relationships cause considerable stress to students, parents and teachers themselves (Richter et al., 2019b). In primary school, the study children and their parents spoke mostly about support staff (resource or special class teacher, SNA) in this regard, with almost none mentioning mainstream class teachers unless it was in the context of a negative experience. However, like Dann (2011), the students and parents in the current research spoke positively about the secondary school teachers describing them as “fun” and “genuine,” as well as “kind and caring.” This finding corroborates the suggestion that a good understanding of ASD is not as important as an approachable and progressive attitude by teachers (Richter et al., 2019a).

Curriculum

The participants in this study welcomed the choice of subjects available at secondary school. This variety affords children with ASD an opportunity to explore their interests that is not an option for them at primary school (Neal and Frederickson, 2016). Additionally, the interest the children displayed in their school subjects is essential given that academic interest has been recognized as suggestive of a positive transition (Peters and Brooks, 2016).

Homework emerged as a concern in previous research given the challenge people with ASD have when separate environments such as home and school intersect (Dillon and Underwood, 2012). It is not surprising, therefore, that homework represented a talking point for most participants before and after the transition. Following transition, the children in the ASD classes described the benefits of having opportunities during the day to complete their homework.

School Organization

Comparable to findings by Neal and Frederickson (2016), the results suggested that the children valued many of the changes in school environment occurring due to transition to secondary school. Participants spoke about the benefits of moving class every 40 min, not having the same teacher all day, and the benefits of clearly defined rules and structures.

As with previous research (Makin et al., 2017), the children in this research identified many supports available to the entire school population as helpful, e.g., timetables, homework journals. Many practices identified as supportive in primary school were evident within the secondary school environment. This was evident in the fact that all participants spoke about the need for movement breaks from the classroom in primary school, whereas after transferring, it was only mentioned by one parent. Following the transition, a significant issue for the children attending mainstream was the locker system. However, for children in the ASD classes, this was not an issue as their lockers were in the ASD base classes.

Parents reported that primary schools seemed reluctant to allow sufficient differential treatment for students with ASD, compared to secondary schools that appeared to acknowledge to a greater extent that some students required differential arrangements. This finding is significant given the impact of students' perceptions of school climate on their mental and emotional well-being over the transition period (Lester and Cross, 2015).

Accommodations

Participants identified a “safe place” or “alternative place” to go at break times or when they needed to regulate themselves as a feature of secondary school that appealed to them, compared to their primary school where everyone had to go to the yard at lunchtime. This is important given that unstructured times of the day, such as breaks, have been identified as challenging for students with ASD (Deacy et al., 2015). It is consistent with previous findings regarding the benefits of a designated space for children with ASD (Dann, 2011; Hoy et al., 2018).

Children were also positive about having special classes (or “units”) that they could attend when they were not being taught by mainstream subject specialist teachers. The prevalence of special classes was far greater at secondary school and provided children with a respite from the more complex social environment including that experienced at break and lunch time. Having school lockers in the special class at secondary school was also a protective factor for one child, whereas other children found this aspect of school organization stressful when their lockers were in the main corridors.

Some have argued that the concept of an ASD class goes against principles of inclusion (see Hornby, 2015 for further information). However, one child and their parent in the sample who transitioned from a mainstream primary school class to an ASD class at secondary reported feeling more included at secondary school than in primary school.

One participant was at times struggling with the transition and a lack of understanding regarding the subtle presentation of ASD was attributed to precipitating many of the ongoing challenges they faced in school. School staff need to acknowledge the heterogeneous presentation of needs regarding children with ASD (Dillon and Underwood, 2012), as there is no one defined method of supporting children with ASD at transition (Tso and Strnadová, 2017).

Preparation

The importance of transition planning has been emphasized in the literature (Evangelou et al., 2008), particularly for students with ASD (Richter et al., 2019b), whose experience of transition is more extreme than that of their typically developing peers (Dann, 2011). Participants identified pre-transition visits to their secondary school as being most helpful. This is consistent with previous findings relating both to children with ASD (Dann, 2011; Neal and Frederickson, 2016) and their typically developing peers (Zeedyk et al., 2003).

Continuities and Discontinuities in Experience

There were several continuities in the fits that children experienced when moving from primary to secondary school. These included friendships, and kind and understanding teachers. There were also continuities in the misfits they experienced, including being teased, becoming distressed by their peers' disruptive behavior in class, being treated “differently” by SNAs (who often followed the children around school), and learning foreign languages with the most difficulties reported for learning Irish.

There were also discontinuities in school organization across the transition. These generated a larger number of observed fits at secondary school: feeling more accepted by friends for being “who they are,” the move to subject specialist teaching, new subject choices, better facilities for school subjects, accommodations for homework, movement between classes, and having special classes as a base. There were also discontinuities which generated new misfits including having lockers in main corridors, no uniform accommodations, and not being able to access laptops in every class. Many of these fits at secondary school, such as enjoying the move to subject specialist teaching and being able to move around the school more frequently have been identified in other studies of children without identified needs (Symonds and Hargreaves, 2014). These findings therefore could represent fits that are adaptive for most children but have particular relevance for meeting the needs of children with ASD.

Implications for Practice

Children perceived many psychological fits in secondary school, including provision of more specialized support for ASD, making new friends, and having caring teachers. This finding implies that educational and psychological practitioners might help alleviate children's anxieties about transition by telling them “good news” stories based on this study and similar research. The increased choice of school subjects at secondary school was a positive experience for children. Schools could build on this result by ensuring that children with ASD receive a broad and balanced curriculum no matter what their level of need. Children's enjoyment of movement breaks at secondary school, including moving between classes, could inform primary schools where educators might increase the frequency of times during the day that children with ASD (and all children) can move about freely. Having a safe space, such as an ASD classroom, to retreat to at secondary school was also appreciated by several children, implying that “safe spaces” for children with ASD might also be helpful in primary schools. Finally, giving children adequate time to familiarize themselves with their new school environment before the transition was important to alleviate anxieties therefore extended pre-transition visits to secondary schools is recommended for children with ASD.

Limitations

A limitation of the current research is the small sample size and representativeness of the participants, who were a self-selected group from a relatively small geographical area. Other limitations relate to gender imbalance in the sample, that all student participants were quite high functioning, the absence of fathers' perspectives amongst the parent voices, the absence of perspectives of school personnel, and that the research was completed early in the transition process. Nevertheless, this is the first study to examine the transition to secondary school experiences of Irish children with ASD and it is an in-depth study examining the perspectives of students with ASD and their parents at two time points in the transition process. The findings provide perspectives that future research could explore.

Longitudinal research has suggested that positive attitudes experienced by children with ASD following transition decline over time (Hebron, 2017b), and also that transition to secondary is not a static process and instead exists on a continuum (Jindal-Snape and Cantali, 2019). Therefore, a longitudinal study could explore the experiences of children with ASD as they transition through each school year.

Conclusion

The transition to secondary school has been identified as a significant period in the life of students with ASD. Despite the literature concerning transition proposing mixed experiences, the sentiment surrounding transition is generally negative, adding or creating unnecessary anxiety regarding the move. As with previous studies, this research has emphasized the importance of appropriate preparation and cooperation between all the stakeholders. Overall, it appeared that the highly structured secondary school environment involved changes to the curriculum, supportive systems and structures, and overall school climate that was more effective at meeting the needs of the individual children in the sample that their primary schools. This study highlighted aspects of school climate and culture that are essential in ensuring a good fit between the individual needs of children with ASD and their chosen schools.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are from a small potentially identifiable sample. Access to the anonymised data can be requested by email to the authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the UCD Human Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

KS: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. JS: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing—review and editing. WK: conceptualization, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for giving their time generously and trusting us to share their experiences. They would also like to acknowledge the support of the management and staff in the Brothers of Charity (BOC).

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bahena, S., Schueler, B. E., McIntyre, J., and Gehlbach, H. (2016). Assessing parent perceptions of school fit: the development and measurement qualities of a survey scale. Appl. Dev. Sci. 20, 121–134. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2015.1085308

Bloyce, J., and Frederickson, N. (2012). Intervening to improve the transfer to secondary school. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 28, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2011.639345

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic Analysis,” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, eds H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, and D. Rindskopf (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association). p. 57–71.

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Caputi, P., and Magee, C. A. (2015). Qualitative research with families living with autism spectrum disorder: recommendations for conducting semistructured interviews. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 40, 78–91. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2014.964191

Daly, P., Ring, E., Egan, M., Fitzgerald, J., Griffin, C., Long, S., et al. (2016). An Evaluation of Education Provision for Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Ireland. Trim: National Council for Special Education. Retrieved from: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/5_NCSE-Education-Provision-ASD-Students-No21.pdf

Dann, R. (2011). Secondary transition experiences for pupils with Autistic Spectrum Conditions (ASCs). Educ. Psychol. Pract. 27, 293–312. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2011.603534

Deacy, E., Jennings, F., and O'Halloran, A. (2015). Transition of students with autistic spectrum disorders from primary to post-primary school: a framework for success. Support Learn. 30, 292–304. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12102

Dillon, G. V., and Underwood, J. D. (2012). Parental perspectives of students with autism spectrum disorders transferring from primary to secondary school in the United Kingdom. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disablil. 27, 111–121. doi: 10.1177/1088357612441827

Dillon, G. V., Underwood, J. D., and Freemantle, L. J. (2016). Autism and the UK secondary school experience. Focus. Autism. Other Dev. Disablil. 31, 221–230. doi: 10.1177/1088357614539833

Eccles, J., and Midgley, C. (1989). Stage-environment fit: developmentally appropriate classrooms for young adolescents. Res. Motivat. Educ. 3, 139–186.

Eccles, J., and Roeser, R. W. (2009). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit Handb. Adol. Psychol. 1, 404–434. doi: 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001013

Evangelou, M., Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., and Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2008). What Makes a Successful Transition From Primary to Secondary School? Research Report No. DCSF-RR019. Department for Children; Schools and Families; Institute of Education; University of London.

Fayette, R., and Bond, C. (2018). A systematic literature review of qualitative research methods for eliciting the views of young people with ASD about their educational experiences. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 349–365. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1314111

Finlay, C., Kinsella, W., and Prendeville, P. (2019). The professional development needs of primary teachers in special classes for children with autism in the republic of Ireland. Prof. Dev. Educ. 1–21. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1696872. [Epub ahead of print].

Fletcher-Watson, S., and Happé, F. (2019). Autism: A New Introduction to Psychological Theory and Current Debate, 2nd Edn. Abbingdon: Routledge.

Fortuna, R. (2014). The social and emotional functioning of students with an autistic spectrum disorder during the transition between primary and secondary schools. Support Learn. 29, 177–191. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12056

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Kapp, S. K., Brooks, P. J., Pickens, J., and Schwartzman, B. (2017). Whose expertise is it? Evidence for autistic adults as critical autism experts. Front. Psychol. 8:438. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00438

Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: why it is important and how it can be supported. Aust. J. Teacher Educ. 38:7. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2013v38n1.7

Hannah, E. F., and Topping, K. J. (2013). The transition from primary to secondary school: perspectives of students with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. Int. J. Spec. Educ, 28, 145–157. Available online at: http://www.internationalsped.com/articles.cfm?y=2013&v=28&n=1

Hebron, J. (2017a). School connectedness and the primary to secondary school transition for young people with autism spectrum conditions. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 88, 396–409. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12190

Hebron, J. (2017b). “The transition from primary to secondary school for students with autism spectrum conditions,” in Supporting Social Inclusion for Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders, ed C. A. Little (Abingdon: Routledge), 84–99.

Hornby, G. (2015). Inclusive special education: development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. Br. J. Special Educ. 42, 234–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12101

Hoy, K., Parsons, S., and Kovshoff, H. (2018). Inclusive school practices supporting the primary to secondary transition for autistic children: pupil, teacher, and parental perspectives. Adv. Autism 4, 184–196. doi: 10.1108/AIA-05-2018-0016

Hunt, D. E. (1975). Person-environment interaction: a challenge found wanting before it was tried. Rev. Educ. Res. 45, 209–230. doi: 10.3102/00346543045002209

Jindal-Snape, D., and Cantali, D. (2019). A four-stage longitudinal study exploring pupils' experiences, preparation and support systems during primary–secondary school transitions. Br. Educ. Res. J. 45, 1255–1278. doi: 10.1002/berj.3561

Jindal-Snape, D., Cantali, D., MacGillivray, S., and Hannah, E. (2019). Primary-Secondary Transitions: A Systematic Literature Review. Social Research Series. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Jindal-Snape, D., Hannah, E. F. S., Cantali, D., Barlow, W., and MacGillivray, S. (2020). Systematic literature review of primary–secondary transitions: international research. Rev. Educ. 8, 526–566. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3197

Kvale, S., and Brinkmann, S. (2015). InterViews : Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2015). The relationship between school climate and mental and emotional wellbeing over the transition from primary to secondary school. Psychol. Well Being 5:9. doi: 10.1186/s13612-015-0037-8

Makin, C., Hill, V., and Pellicano, E. (2017). The primary-to-secondary school transition for children on the autism spectrum: a multi-informant mixed-methods study. Autism Dev. Lang. Impairm. 2:1–18. doi: 10.1177/2396941516684834

Mandy, W., Murin, M., Baykaner, O., Staunton, S., Hellriegel, J., Anderson, S., et al. (2016). The transition from primary to secondary school in mainstream education for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 20, 5–13. doi: 10.1177/1362361314562616

Martin, T., Dixon, R., Verenikina, I., and Costley, D. (2019). Transitioning primary school students with autism spectrum disorder from a special education setting to a mainstream classroom: successes and difficulties. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1568597. [Epub ahead of print].

McCoy, S., Banks, J., Frawley, D., Watson, D., Shevlin, M., and Smyth, F. (2014). Understanding Special Class Provision in Ireland. Phase 1: Findings From a National Survey of Schools. Available online at: http://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Report_16_special_classes_30_04_14.pdf

McCoy, S., Shevlin, M., and Rose, R. (2020). Secondary school transition for students with special educational needs in Ireland. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 154–170. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1628338

National Council for Special Education (2016). Supporting Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Schools NCSE POLICY ADVICE NO. 5. Retrieved from: http://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/1_NCSE-Supporting-Students-ASD-Schools.pdf

Neal, S., and Frederickson, N. (2016). ASD Transition to mainstream secondary: a positive experience? Educ. Psychol. Pract. 32, 355–373. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2016.1193478

Parsons, S., Guldberg, K., MacLeod, A., Jones, G., Prunty, A., and Balfe, T. (2011). International review of the evidence on best practice in educational provision for children on the autism spectrum. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 26, 47–63. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2011.543532

Peters, R., and Brooks, R. (2016). Parental perspectives on the transition to secondary school for students with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism: a pilot survey study. Br. J. Special Educ. 43, 75–91. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12125

Powell, K. K., Heymann, P., Tsatsanis, K. D., and Chawarska, K. (2018). “Assessment and diagnosis of infants and toddlers with autism spectrum disorder,” in Assessment of Autism Spectrum Disorder, 2nd Edn, eds. S. Golstein and S. Ozonoff (The Guilford Press), p. 96–129.

Psychological Society of Ireland (2011). Guidelines on Confidentiality and Record Keeping. Available online at: https://www.psychologicalsociety.ie/source/PSI%20Guidelines%20on%20Confidentiality%20%26%20Record%20Keeping%20in%20Practice%20(final).pdf

Psychological Society of Ireland (2019). Code of Professional Ethics. Available online at: https://www.psychologicalsociety.ie/footer/Code-of-Ethics

Richter, M., Flavier, E., Popa-Roch, M., and Clément, C. (2019a). Perceptions on the primary-secondary school transition from french students with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 171–187. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1643145

Richter, M., Popa-Roch, M., and Clément, C. (2019b). Successful transition from primary to secondary school for students with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic literature review. J. Res. Childhood Educ. 33, 382–398. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2019.1630870

Stoner, J. B., Angell, M. E., House, J. J., and Bock, S. J. (2007). Transitions: perspectives from parents of young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 19, 23–39. doi: 10.1007/s10882-007-9034-z

Symonds, J., and Galton, M. (2014). Moving to the next school at age 10–14 years: an international review of psychological development at school transition. Rev. Educ. 2, 1–27. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3021

Symonds, J., and Hargreaves, L. (2014). Emotional and motivational engagement at school transition: a qualitative stage-environment fit study. J. Early Adolesc. 36, 54–85. doi: 10.1177/0272431614556348

Topping, K. (2011). Primary–secondary transition: differences between teachers' and children's perceptions. Improv. Sch. 14, 268–285. doi: 10.1177/1365480211419587

Tso, M., and Strnadová, I. (2017). Students with autism transitioning from primary to secondary schools: parents' perspectives and experiences. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 21, 389–403. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1197324

Waters, S., Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2014). How does support from peers compare with support from adults as students transition to secondary school? J. Adol. Health 54, 543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.012

Keywords: autism, transition, primary school, secondary school, ASD, school transition

Citation: Stack K, Symonds JE and Kinsella W (2020) Student and Parent Perspectives of the Transition From Primary to Secondary School for Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Educ. 5:551574. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.551574

Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020;

Published: 11 December 2020.

Edited by:

Caroline Bond, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Yini Liao, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaSiobhan O'Hagan, Halton Borough Council, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Stack, Symonds and Kinsella. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karen Stack, a2FyZW4uc3RhY2tAdWNkY29ubmVjdC5pZQ==

Karen Stack

Karen Stack Jennifer E. Symonds

Jennifer E. Symonds William Kinsella

William Kinsella