- 1Department of Research Methods in Education, Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Department of Business and Economics Education, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

- 3Stanford Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States

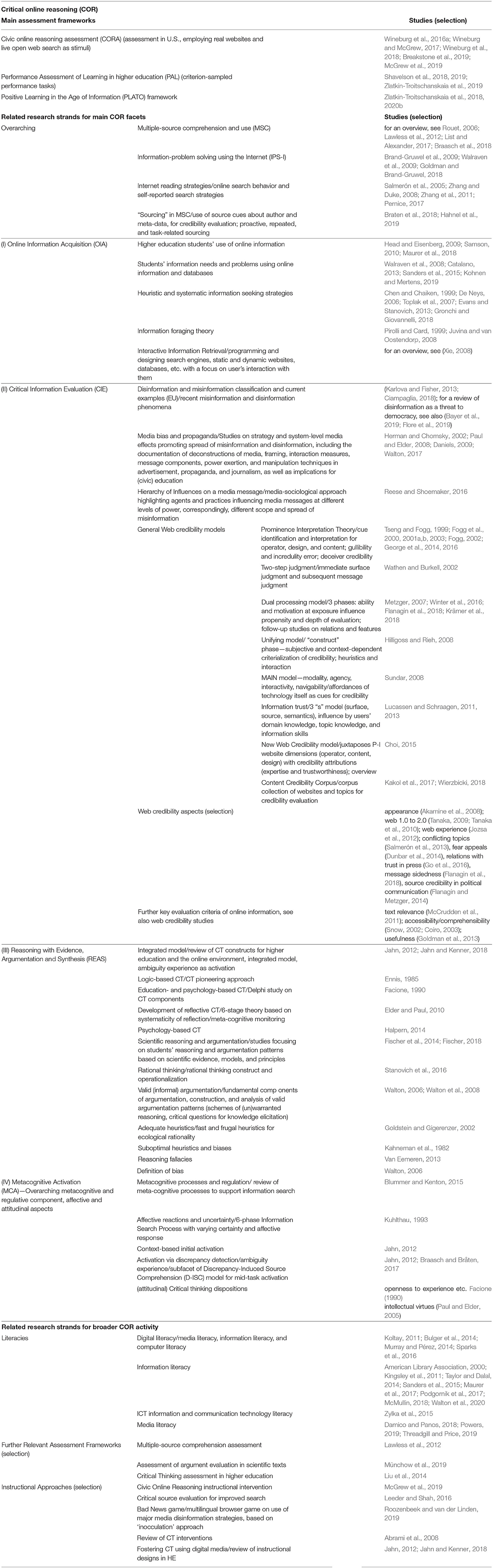

Critical evaluation skills when using online information are considered important in many research and education frameworks; critical thinking and information literacy are cited as key twenty-first century skills for students. Higher education may play a special role in promoting students' skills in critically evaluating (online) sources. Today, higher education students are more likely to use the Internet instead of offline sources such as textbooks when studying for exams. However, far from being a value-neutral, curated learning environment, the Internet poses various challenges, including a large amount of incomplete, contradictory, erroneous, and biased information. With low barriers to online publication, the responsibility to access, select, process, and use suitable relevant and trustworthy information rests with the (self-directed) learner. Despite the central importance of critically evaluating online information, its assessment in higher education is still an emerging field. In this paper, we present a newly developed theoretical-conceptual framework for Critical Online Reasoning (COR), situated in relation to prior approaches (“information problem-solving,” “multiple-source comprehension,” “web credibility,” “informal argumentation,” “critical thinking”), along with an evidence-centered assessment framework and its preliminary validation. In 2016, the Stanford History Education Group developed and validated the assessment of Civic Online Reasoning for the United States. At the college level, this assessment holistically measures students' web searches and evaluation of online information using open Internet searches and real websites. Our initial adaptation and validation indicated a need to further develop the construct and assessment framework for evaluating higher education students in Germany across disciplines over their course of studies. Based on our literature review and prior analyses, we classified COR abilities into three uniquely combined facets: (i) online information acquisition, (ii) critical information evaluation, and (iii) reasoning based on evidence, argumentation, and synthesis. We modeled COR ability from a behavior, content, process, and development perspective, specifying scoring rubrics in an evidence-centered design. Preliminary validation results from expert interviews and content analysis indicated that the assessment covers typical online media and challenges for higher education students in Germany and contains cues to tap modeled COR abilities. We close with a discussion of ongoing research and potentials for future development.

Introduction

Relevance and Research Background

Today, higher education students use the Internet to access information and sources for learning much more frequently than offline sources such as textbooks (Gasser et al., 2012; Maurer et al., 2020). However, there have been warnings about the harmful effects of online media use on students' learning (Maurer et al., 2018), with misinformation and the acquisition of (domain-specific) misconceptions and erroneous knowledge being prominent examples (Bayer et al., 2019; Center for Humane Technology, 2019). While Internet users are generally concerned about their ability to distinguish warranted, fact-based knowledge from misinformation1 (Newman et al., 2019), research on web credibility suggests that Internet users pay little attention to cues indicating erroneous information and a lack of trustworthiness; similar findings were determined across a variety of online information environments and learner groups (Fogg et al., 2003; Metzger and Flanagin, 2013, 2015).

For learning in higher education, the Internet may have both a positive and a negative impact (Maurer et al., 2018, 2020). Positive affordances for collaboration, organization, aggregation, presentation, and the ubiquitous accessibility of information have been discussed in research on online and multimedia learning (Mayer, 2009). However, problems such as addictive gratification mechanisms, filter bubbles and algorithm-amplified polarization, political and commercial targeting based on online behavior profiles, censorship, and misinformation (Bayer et al., 2019; Center for Humane Technology, 2019) have recently been critically discussed as well. The potential of online applications and social media for purposes of persuasion has been known for some time (Fogg, 2003), though the impact of online information on knowledge acquisition is still under-researched to date.

As recent research indicates, the multitude of information and sources available online may lead to information overload (Batista and Marques, 2017; Hahnel et al., 2019). Lower barriers to publication and the lack of requirements for quality assurance, fewer gatekeepers, and faster distribution result in a highly diverse online media landscape and varying information quality (Shao et al., 2017). Students are confronted with quality shortcomings such as incomplete, contradictory, or erroneous information when obtaining and integrating new information from multiple online sources (List and Alexander, 2017; Braasch et al., 2018). Hence, whenever Internet users are acquiring knowledge based on online information or performing online search queries in a way that can be framed as solving an information problem (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2005), they are faced with the challenge of finding, selecting, accessing, and using suitable information. In addition, online learners need to avoid distractions (e.g., advertisements, clickbait) and misinformation as well as evaluate the information they choose with regard to possible biases and specific narrative framing of information (Walton, 2017; Banerjee et al., 2020). To successfully distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy online information, students need to judge its relevance to their inquiry and, in particular, evaluate its credibility (Flanagin et al., 2010; Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018). The ability to find suitable information online, distinguish trustworthy from untrustworthy information, and reason based on this information is examined under the term of “critical online reasoning.” These abilities are crucial for (self-)regulated (unsupervised) acquisition of warranted (domain-specific) knowledge based on online information.2 In this context, current studies are focusing on the development of (domain-specific) misconceptions and the acquisition of erroneous knowledge over the course of higher education studies, specifically among students who report that they predominantly use Internet sources when studying (Maurer et al., 2018, 2020).

University Students' Critical Online Reasoning Assessment (CORA): Study Context

To acquire reliable and warranted (domain-specific) knowledge, students need to access, evaluate, select, and ultimately reason based on relevant and trustworthy information from online sources. At the same time, they need to recognize erroneous or (intentionally) misleading information and possible corresponding bias, for instance, due to underlying framing or unwarranted perspectives, to avoid being misled and acquiring erroneous knowledge. To properly handle online sources featuring incorrect, incomplete, and contradictory information, students need to recognize patterns in the information indicating its trustworthiness or lack thereof (cues for credibility or misinformation) based on self-selected criteria such as perceived expertise or communicative intentions to acquire reliable, warranted (domain-specific) knowledge using the Internet.

Students' critical evaluation skills when dealing with online information are considered important in many research frameworks in a multitude of disciplines that address the online learning-and-teaching environment (Section Theoretical and Conceptual Framework; Table 1). Like critical thinking and information literacy, they are considered to be among the key twenty-first century skills, and are considered key skills for “Education in the Digital World” (National Research Council, 2012; KMK, 2016). Skills related to the critical-reflective use of online information are more important than ever, which becomes evident especially with regard to the internet-savvy younger generations (Wineburg et al., 2018). Higher education can play a special role in promoting students' critical thinking skills and their skills in evaluating (online) sources (Moore, 2013) due to the evidence-based, research-focused orientation of most academic disciplines (Pellegrino, 2017). For instance, graduate students were found to have advanced critical thinking skills, which has been attributed to the fact that they wrote a bachelor thesis as part of their undergraduate studies (Shavelson et al., 2019; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019).

Despite being of central importance for studying using the Internet, the assessment of students' skills related to critical online reasoning (COR) is an emerging field with conceptual and theoretical frameworks building on a large number of prior research strands (Section Theoretical and Conceptual Framework; Table 1). For instance, computer skills, digital and information literacy, and critical thinking approaches have described and examined (bundles of) related facets. To our knowledge, there is no conceptual and assessment framework to date that describes and operationalizes COR as an interrelated triad of its key facets (i) information acquisition in the online environment, (ii) critical information evaluation, and (iii) reasoning using evidence, argumentation, and synthesis.

In this context, pioneering work has been done by Wineburg et al. (2018) from the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), who developed an assessment for measuring Civic Online Reasoning at the middle school, high school, and college level. At the college level, this holistic assessment of how students evaluate online information and sources comprises short evaluation prompts, real websites, and an open Internet search (Wineburg and McGrew, 2016; Wineburg et al., 2016a,b). The assessment was validated in a nationwide study in the U.S. (Wineburg et al., 2018), which indicated substantial deficits in these skills among higher education students.

Based on this U.S. research, we adapted the assessment framework for higher education in Germany. The preliminary validation of the U.S. assessment for Germany indicated that an adaption and validation in terms of the recommendations by the international Test Adaptation Guidelines [TAGs, International Test Commission (ITC), 2017] was not possible. It became evident that, in addition to the practical difficulties of adapting the U.S. assessment web stimuli for assessing the critical evaluation of online information for learning in the German higher education context, expert interviews (Section Content Analysis: CORA Task Components as Coverage of the Construct) indicated that due to the differences in terms of historical and socio-cultural traditions between the two countries, in German higher education, the concept of “civic education” is less prominent than “academic education” (for a comparison of the concept of education/ “Bildung” in Germany and in the U.S., see (Beck, 2020); for a model of critical thinking, see Oser and Biedermann, 2020). Moreover, experts noted that students learn from information from a variety of sources not necessarily related to civic issues (e.g., commercial websites), in addition to scientific publications and textbooks, and it remains unclear how new knowledge based on these multiple sources is integrated, which requires further differentiation and specification.

Based on the results of this preliminary validation, we modified the theoretical framework by expanding our focus beyond civic reasoning to include further purposes of online information acquisition, and situated the construct in relation to a number of theories, models, and adjacent fields, focusing on the research traditions of critical thinking (Facione, 1990), which are more applicable to Germany (than civic reasoning), as well as in relation to additional relevant constructs such as “web credibility,” “multiple source comprehension,” “multiple-source use,” and “information problem-solving” using the Internet (Metzger, 2007; Braasch et al., 2018; Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018). Based on a combination of converging aspects from these research strands, we developed a new conceptual framework to describe and operationalize the abovementioned triad of key facets underlying the resulting skill of Critical Online Reasoning (COR): (i) online information acquisition, (ii) critical information evaluation, and (iii) reasoning using evidence, argumentation, and synthesis.

Research Objectives and Questions

The first objective of this paper is to present this newly developed conceptual and assessment framework, and to locate this conceptualization and operationalization approach in the context of prior and current research while critically reflecting on its scope and limitations. The methodological framework is based on an evidence-centered assessment design (ECD) (Mislevy, 2017). According to ECD, alignment of a student model, a task model, and an interpretive model are needed to design assessments with validity in mind. The student model covers the abilities that students are to develop and exhibit (RQ1); the task model details how abilities are tapped by assessment tasks (RQ2); and the interpretive model describes the way in which scores are considered to relate to student abilities (RQ3). The following research questions (RQ) are examined in this context.

RQ1: What student abilities and mental processes does the CORA cover? How can the COR ability be described and operationalized in terms of its construct definition?

RQ2: What kinds of situations (task prompts), with which psychological stimuli (i.e., test definition), are required to validly measure students' abilities and mental processes in accordance with the construct definition?

As a second objective of this paper, we focus on the preliminary validation of the COR assessment (hereinafter referred to as CORA). The validation framework for CORA is based on approaches by Messick (1989) and Kane (2012). A qualitative evaluation of the CORA yielded preliminary validity evidence based on a content analysis of the CORA tasks, and interviews with experts in media science, linguistics, and test development (Section Content Analysis: CORA Task Components as Coverage of the Construct). Based on the results of content validation studies conducted according to the Standards for Pedagogical and Psychological Testing (AERA et al., 2014; hereinafter referred to as AERA Standards), the following RQ was investigated:

RQ3: To what extent does the preliminary evidence support the validity claim that CORA measures the participants' personal construct-relevant abilities in the sense of the defined construct definition?

In Section Theoretical and Conceptual Framework, we first present the theoretical and conceptual COR framework, also in terms of related research approaches. In Section Assessment Framework of Critical Online Reasoning, we describe the U.S. assessment of civic online reasoning and present our work toward adapting and further developing this approach into an expanded assessment framework and scoring scheme for measuring COR in German higher education. In Section Preliminary Validation, we report on initial results from the preliminary validation studies. In Section Research Perspectives, we close with implications for refining CORA tasks and rubrics and give an outlook on ongoing further validation studies and analyses using CORA in large-scale assessments.

Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

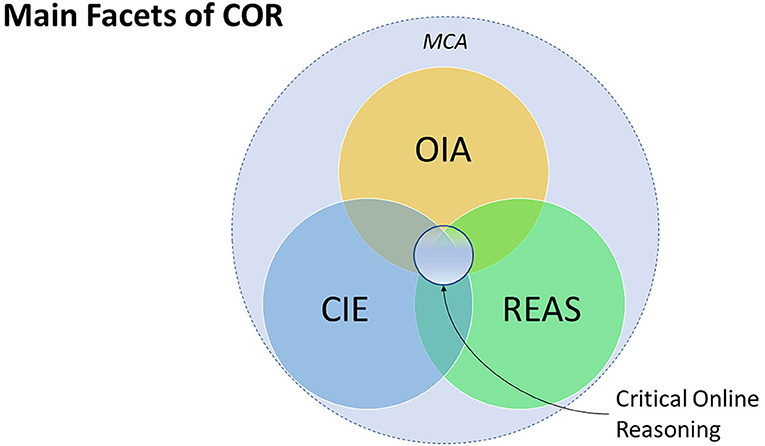

In this section, we outline the working construct definition for Critical Online Reasoning (COR) as a basis for the CORA framework. We explain the theoretical components and key considerations used to derive this COR construct definition from related prior approaches and frameworks. COR is modeled from a process, content, domain, and development perspective. For brevity, we only describe the key facets and central components and list the most relevant references categorized by (sub)facets in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The COR construct with its main facets: MCA, metacognitive activation; OIA, online information acquisition; CIE, critical information evaluation; REAS, reasoning with evidence, argumentation and synthesis.

Construct Definition of Critical Online Reasoning

The working construct definition of COR (RQ1) describes the personal abilities of searching, selecting, accessing, processing, and using online information to solve a given problem or build knowledge while critically distinguishing trustworthy from untrustworthy information and reasoning argumentatively based on trustworthy and relevant information from the online environment.

This construct definition focuses on a combination of three overlapping facets: (i) Online Information Acquisition (OIA) abilities (for inquiry-based learning and information problem-solving), (ii) Critical Information Evaluation (CIE) abilities to analyze online information particularly in terms of its credibility and trustworthiness, and (iii) abilities to use the information for Reasoning based on Evidence, Argumentation, and Synthesis (REAS), weighting (contradictory) arguments and (covert) perspectives, while accounting for possible misinformation and biases. In addition, we assume that the activation of these COR facets requires metacognitive skills, described in the Metacognitive Activation (MCA) (Figure 1).

Theoretical Components of COR

Process Perspective

Online Information Acquisition (OIA) focuses on the searching and accessing of online information, for example by using general and specialized search engines and databases, specifying search queries, opening specific websites. Beyond these more technical aspects, COR focuses in particular on searching for specific platform entries and passages and terms on a website in as far as they contribute to an (efficient) accessing of relevant and trustworthy information and avoidance of untrustworthy information (Braten et al., 2018; the Information Search Process model, Kuhlthau et al., 2008).

Critical Information Evaluation (CIE) is crucial for self-directed, cross-sectional learning based on online information. This facet focuses on students' selection of information sources and evaluation of information and sources based on website features or specific cues (e.g., text, graphics, audio-visuals). Following comprehension-oriented reception and processing, CIE is used to differentiate and select high- instead of low-quality information (relative to one's subjective standards and interpretation of task requirements). A cue can be any meaningful pattern in the online environment interpreted as an indicator of (trustworthy or untrustworthy) online media or communicative means. Examples of cues may be a URL, title or keyword on the search engine results page, a layout or design element, media properties, an article title, information about author, publisher or founder, publication date, certain phrasings, legal or technical information. Trustworthiness “evaluations” typically include targeted verification behavior, which results in a (defeasible) “judgment” about a web medium or piece of information, which may be based on an initial heuristic appraisal without further (re-)evaluation. However, CIE as “evaluation” can require a more systematic analytical, criteria-based judgment process for students, possibly using multiple searches to establish reliable and warranted knowledge (for an overview on related multiple document comprehension frameworks, see Braten et al., 2018; e.g., the Discrepancy-Induced Source Comprehension (D-ISC) model, Braasch and Bråten, 2017).

Reasoning with Evidence, Argumentation, and Synthesis (REAS) is probably the most important facet of COR, which distinguishes this construct from “literacy” constructs (e.g., digital, information or media literacy). This facet focuses on uniting the initially appraised information, weighting it against further indications and perspectives, and using it as evidence to construct a convincing argument that accounts for uncertainty (Walton, 2006). Argumentation is a well-suited discourse format for deliberating whether to accept a proposition (e.g., to trust or distrust). Evidence-based argumentation imposes certain quality standards for a well-founded judgment (e.g., rationality) and requires minimal components of a claim, reasons, evidence (and data) and conventional inferential connections between them (e.g., Argumentation Schemes, Walton, 2006; Walton et al., 2008; Fischer et al., 2014; Fischer, 2018).

These three main facets, OIA, CIE, and REAS, are primarily considered cognitive abilities. Each of them can also take on a metacognitive quality within the COR process, for example as reasoners (internally) comment on their ongoing search, evaluation or argument construction (e.g., “I would not trust this website”), or (self-)reflect on previously acquired knowledge to identify incorrectness or inconsistencies (e.g., “This sentence here contradicts that other source/what I know about the subject”). The latter reflection can become epistemic if it turns to the method of information acquisition and reasoning itself (e.g., “How did I end up believing this scam?”).

These main facets are accompanied by an overarching, self-regulative, metacognitive COR component that activates deliberate COR behavior and coordinates (transitions) between the COR facets in the progression of COR activity, particularly for activating a critical evaluation and deciding when to terminate it, in relation to other events (e.g., during a learning experience, social communication)3. Self-regulation can be applied to monitor and maintain focus (noticing unfocused processing, returning to task) and handle environmental signals (identifying and minimizing distracting information features) (Blummer and Kenton, 2015). As reasoners may have affective responses (Kuhlthau, 1993) to their task progress and to specific information (particularly on controversial topics), affective self-regulation can not only support them in staying on task and keeping an open mind, but they can use it meta-cognitively for COR to gain an insight into unconsciously processed information (e.g., identifying and coping with triggered avoidance reactions or anxiety induced by ambiguity or manipulation attempts) and can critically reflect on triggers in the source cues.

Thus, Metacognitive Activation (MCA) is assumed to be an ability required to activate COR in relevant contexts. (Epistemic) metacognition can be characterized by gradations of self-awareness regarding information acquisition, evaluation and reasoning processes, which may activate a “vigilance state” in students and lead to certain (subconscious) reactions (and a habitual affective response, e.g., anxiety, excitement), or can also be interpreted as an indicator of a potential problem with processed information (“am I being lied to/at risk after misjudging the information?”) at the metacognitive level (on uncertainty and emotions when searching for information, see Kuhlthau, 1993; on ambiguity experience as the first stage in a general critical reasoning process, see Jahn and Kenner, 2018), which may lead to the activation of an evaluative COR process.

The main facets of COR and the overarching metacognitive self-regulative component are understood to determine COR performance (and are the focus of the CORA, Section Test Definition and Operationalization of COR: Design and Characteristics of CORA Tasks). The main COR facets are assumed to rely on “secondary” sub-facets that provide support in cases where related specific problems occur, including self-regulation for minimizing distractions and on-task focus, as well as diverse knowledge sub-facets.

Knowledge sub-facets may include, for OIA, knowledge of resources and techniques for credibility verification; for CIE, knowledge of credibility indicators and potentially misleading contexts and framings, manipulative genres and communication strategies; for REAS, knowledge of reasoning standards as well as fallacies, heuristics, and perceptual, reasoning and memory biases as well as of epistemic limitations for trustworthiness assertions. The list is non-exhaustive, and the knowledge and skills are problem-dependent (e.g., checking for media bias will yield conclusive results only if there is in fact a bias in the stimulus material); they can be expected to impact COR in related cases. Hence, controlling for corresponding stimuli encompassed in the task is recommended.

Attitudinal dispositions for critical reasoning and thinking, such as open-mindedness, fairness, and intellectual autonomy (Facione, 1990; Paul and Elder, 2005) are equally likely candidates for COR influences. These secondary facets are not examined in the current conceptualization.

Content Perspective

For acquiring information online in a warranted way, students need to successfully identify and use trustworthy sources and information and avoid untrustworthy ones. In contrast, unsuccessful performance is marked by trusting untrustworthy information, a gullibility error, or refusing to accept trustworthy sources, an incredulity error (Tseng and Fogg, 1999). To decide which information to trust and use, students need to judge information in regard to several criteria, including at least the following: usefulness, accessibility, relevance, and trustworthiness. Information may be judged as useful if it advances the inquiry, for instance by supporting the construction of an argument; usefulness may also be understood as a holistic appraisal based on all other criteria. Lack of accessibility (or comprehensibility) limits students to the parts of the information landscape that they can confidently access and process (e.g., students may ignore a search result in a foreign language or leave a website with a paywall, but also abandon a text they deem too difficult to locate or understand in the given task time). In an open information environment, successfully judging relevance as relatedness or specificity to the topic of inquiry and trustworthiness or quality of information enables students to select and spend more time on high-quality sources and avoid untrustworthy sources. Assuming students will attempt to ignore information they judge as untrustworthy, any decision in this regard affects their available information pool for reasoning and learning.

The judgment of trustworthiness as an (inter-)subjective judgment of the objectively verifiable quality of an online media product against an evidential or epistemic standard is central to COR. In more descriptively oriented “web credibility” research, a credibility judgment is understood as a subjective attribution of trust to an online media product; trustworthiness in COR is closely related, but presupposes that the judgment can be based on valid or invalid reasoning (acceptable or unacceptable based on a normative standard) and hence can be evaluated as a skill. Trustworthiness in COR can be considered a warranted credibility judgment. Consequently, COR enables students to distinguish trustworthy from untrustworthy information and, more specifically, various sub-types based on assumed expertise and communicative intent, for example: accidental misinformation due to error, open or hidden bias, deliberate disinformation, and (non-epistemic) “bullshitting.” A more fine-grained judgment is assumed to afford higher certainty, a more precise information selection, and more adequate response to an information problem. To successfully infer the type of information, reasoners may evaluate cues from at least three major strands of evidence about an online medium, including cues on content, logic, and evidence; cues on design, surface structure, and other representational factors; and cues on author, source, funding, and other media production and publication-related factors. Reasoners may evaluate these themselves (using their own judgment), trust the judgment of experts (external judgment), or a combination of the two; when accepting external judgment, instead of the information itself, reasoners need to judge at least their chosen expert's topic-related expertise and truth-oriented intent.

Domain-Specificity and Generality

Based on the CORA framework, COR is modeled for generic critical online reasoning (GEN-COR) on tasks and websites that do not require specialized domain knowledge and are suited for young adults after secondary education. The construct can be specified for study domains (DOM-COR), for instance by defining domain standards of evidence for distinguishing trustworthy from untrustworthy information and typical domain problems regarding the judgment of online information.

Development Perspective

Different gradations can be derived based on task difficulty, complexity, time, and aspired specificity of reasoning (Sections Test Definition and Operationalization of COR: Design and Characteristics of CORA Tasks and Scoring Rubrics). COR ability levels were distinguished to fit the main construct facets depending on students' performance in (sub-)tasks tapping OIA, CIE, and REAS (see rubrics in Section Scoring Rubrics; Table 1).

Assessment Framework of Critical Online Reasoning

Civic Online Reasoning

Wineburg and McGrew (2016) developed an assessment to measure civic online reasoning, which they defined as students' skills in interpreting online news sources and social media posts. The assessment includes real, multimodal websites as information sources (and distractors) as well as open web searches. The construct of civic online reasoning was developed from the construct of news media literacy (Wineburg et al., 2016a). It was conceptualized as a key sub-component of analytic thinking while using online media. The assessment aims to measure whether students are able to competently navigate information online and to distinguish reliable, trustworthy sources and information from biased and manipulative information (Wineburg et al., 2016a).

The students' skills required to solve the tasks were assessed under realistic conditions for learning using the Internet, i.e., while students performed website evaluations and self-directed open web searches (Wineburg and McGrew, 2017). The computer-based assessment presents students with short tasks containing links to websites with, for instance news articles or social media text and video posts, which students are asked to evaluate. The task prompts require the test-takers to evaluate the credibility of information, and to justify their decision, also citing web sources as evidence. The topics focus on various political and social issues of most US-centric civic interest, typically with conflicting constellations of sources.

Using this assessment, the SHEG surveyed a sample of 7,804 higher education students across the U.S. (Wineburg et al., 2016a), and compared the students' performance to that of history professors and professional fact checkers. Based on the findings, the search engine results pages designed and implemented an intervention to improve students' civic online reasoning in higher education (Wineburg and McGrew, 2016; McGrew et al., 2019).

Critical Online Reasoning Assessment (CORA)

In our project4, the initial goal was to adapt this instrument to assess the civic online reasoning of students in higher education in Germany and to explore the possibility of using this assessment in cross-national comparisons. The assessment of civic online reasoning features realistic judgment and decision-making scenarios with strong socio-cultural roots, which may engage and tap both the (meta)cognition and the emotional responses of test-takers, as well as their critical evaluation skills. While cultural specificity may present advantages in a within-country assessment, these can become idiosyncratic challenges in cross-national adaptations (e.g., Arffman, 2007; Solano-Flores et al., 2009). Even though we followed the state-of-the-art TAGs by the ITC International Test Commission (2017) and the best-practice approach of (Double-)Translation, Reconciliation, Adjudication, Pretesting, and Documentation (TRAPD, Harkness, 2003) in assessment adaptation research (as recommended in the TAGs), after the initial adaptation process (Molerov et al., 2019), both the (construct) definition of civic online reasoning and the adapted assessment of civic online reasoning showed limitations when applied to the context of learning based on online information in German academic education. The translation team faced several major practical challenges while adapting the real website stimuli, and the results were less favorably evaluated by adaptation experts. This was a key finding from the adaptation attempts and preliminary construct validation by means of curricular analyses and interviews with experts for German higher education. Both analyses indicated the significant differences in terms of historical and socio-cultural traditions between the higher education systems in the two countries (for details, Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2018b). Regarding construct limitations, curricular analysis indicated differences in the relevance of “civic education” within German higher education, highlighting problems for the (longitudinal and cross-disciplinary) assessment of generic abilities in learning based on online information. Expert interviews conducted in the context of adaptation attempts and the preliminary validation of the U.S. conceptual and assessment framework of “civic online reasoning” (for details, Molerov et al., 2019) indicated that the concept of “civic education” is related to a specific research strand of political education and is less important in German higher education than “academic education,” which is more strongly related to research traditions focusing on critical thinking (for a comparison of the concept of education in Germany and in the U.S., see Beck, 2020; Oser and Biedermann, 2020).

Based on this preliminary validation of the U.S. assessment in Germany, we modified the conceptual framework (Section Theoretical Components of COR) to accommodate for the close relationship between COR and generic critical thinking, multiple-source comprehension, scientific reasoning and informal argumentation approaches (Walton, 2006; Fischer et al., 2014, 2018; Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018; Jahn and Kenner, 2018), and expanded the U.S. assessment framework to cover all online sources that students use for learning. We developed the scoring rubrics accordingly to validly measure the critical online reasoning (COR) ability of higher education students of all degree programs in Germany in accordance with our construct definition (Section Construct Definition of Critical Online Reasoning). Thus, new CORA tasks with new scenarios were created to cover the (German) online media landscape used for learning and topics including culturally relevant issues and problems. The assessment framework was expanded to comprise tasks stimulating web searches, the critical evaluation of online information, and students' use of this information in reasoning based on evidence, argumentation and synthesis to obtain warranted knowledge and solve the given information problems, and to develop coherent and conclusive arguments for their decision (e.g., draft a short essay or evaluative short report). We also developed and validated the scoring scheme to rate the students' responses to the CORA tasks (Section Scoring Rubrics).

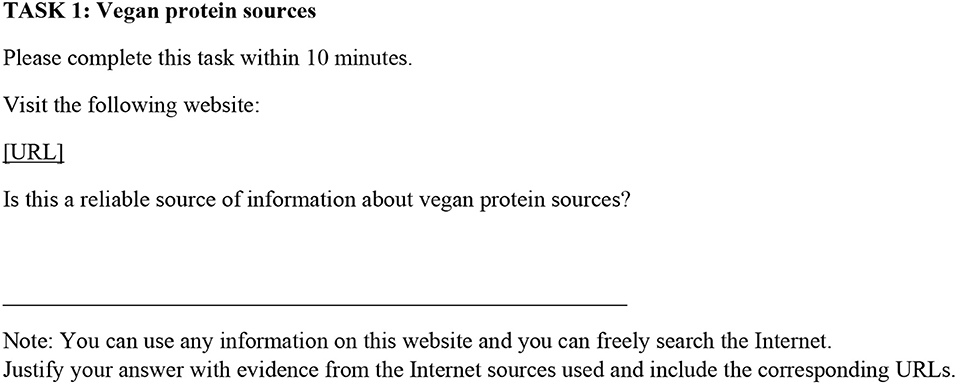

Test Definition and Operationalization of COR: Design and Characteristics of CORA Tasks

The German CORA project developed a holistic, performance assessment that uses criterion-sampled situations to tap students' real-world decision-making and judgment skills. The tasks/situations merit critical evaluation. Students may encounter such tasks when studying and working in academic and professional domains, as well as in their public and private lives (Davey et al., 2015; Shavelson et al., 2018, 2019). CORA comprises six tasks of 10 min each. CORA is characterized by the use of realistic tasks in a natural online environment (for an example, see Figure 2). As tasks are carried out on the Internet, students have an unlimited pool of information from which to search and select suitable sources to verify or refute a claim, while judging and documenting the evidence. Five CORA tasks contain links to websites that may have been published with (covert) commercial or ideological intent, and may, for instance aim to sell products or to convince their audience of a particular point of view by offering low-quality information. The characteristics of the low-quality information offered on websites linked in the CORA tasks included, for instance a selection of information while (intentionally) omitting other perspectives, incorrect or imprecise information, irrelevant and distracting information, and biased framing. The tasks feature snippets of information in online media, such as websites, twitter messages, YouTube videos, put forward by political, financial, religious, media or other groups, some cloaked with covert agendas, others more transparent.

A specific characteristic of the CORA tasks is that only the stimuli and distractors included in the task prompt and the websites linked in the tasks can be manipulated and controlled for by the test developers. Since the task prompt asks the students to evaluate the credibility and trustworthiness of the linked website through a free web search, realistic distractors include, for instance vividly presented information, a large amount of highly detailed information, (unreferenced) technical, numerical, statistical and graphical data, and alleged (e.g., scientific or political) authority. Depending on the search terms used and the research behavior of the participants, they are confronted with different stimuli and distractors in a free web search, i.e., stimuli and distractors may likely vary significantly from person to person. Thus, while we can control the quality of the websites linked in the CORA tasks, the quality of all other websites that students are confronted with during their Internet research depends solely on their search behavior and can be controlled in the assessment only to a limited extent.

Stimuli and Distractors of the Linked Websites

Low-quality information on the linked websites can be caused by a lack of expertise of the author(s), belief-related bias, or accidental errors when drawing inferences or citing from other sources. Moreover, the linked sources offer contradictory information or inconsistencies between multiple online texts, which learners need to resolve in the process of acquiring consistent knowledge. In our example (Figure 2), the provided link leads to a website that offers information about vegan protein sources. At first glance, the website seems to provide accurate and scientifically sound information about vegan nutrition and protein sources, but upon closer inspection, the information turns out to be biased in favor of vegan protein sources. The article is shaped by a commercial interest, since specific products are advertised. This bias can be noticed by reading the content of the website carefully and critically. The existence of an online shop is another indication of a commercial interest motivating the article. In contrast, the references to scientific studies give a false sense of reliability.

As the construct definition of COR states (Section Construct Definition of Critical Online Reasoning), if students wonder about the trustworthiness of certain online information during the inquiry, this should be a sufficient initial stimulus to activate their COR abilities. Thus, we explicitly include the stimulus at the beginning of an inquiry task prompt of all CORA tasks. The in-task cues can tap these activation routes even if the students did not respond to the initial prompt at the beginning of the task (Figure 2). In the example, the participants are also asked whether the website is reliable to stimulate the COR process and a web search.

Following the ECD (Mislevy, 2017), we describe the task model and the student model of the CORA in more detail.

Task Model

Task difficulty in terms of the cognitive requirements of the construct dimensions of COR varies through the task properties and the prompt (i.e., difficulty of deciding on a specific solution by considering pros/cons or both). For instance, in the dimension of OIA, task difficulty varies in terms of whether students are required to evaluate a website and related online sources or only a claim and related online sources. The quality of the websites found in the free web searches is likely to significantly vary between test participants, which is not explicitly controlled for in the task and in the scoring of the task performance. This information is only examined in additional process analyses using the recorded log files (Section Analyses of Response Processes and Longitudinal Studies).

In the easy CORA tasks, the web authors were aware that they may be biased and alerted their audience to this fact, for instance by stating their stance directly or by acknowledging their affiliation to a certain position or perspective—the students then had to take these statements into account in their evaluation. In the difficult CORA tasks, the web authors actively tried to conceal the manipulative or biased nature of their published content—and the students had to recognize the techniques these authors employed. In addition, they had to identify the severity of this manipulation and to autonomously decide which information was untrustworthy and should therefore not be taken into consideration. This untrustworthy information can comprise a single word or paragraph, an entire document, all content by a specific author or organization, or even entire platforms (e.g., if their publication guidelines, practices, and filters allow for low-quality information) or entire geographical areas (e.g., due to biased national discourse).

For each CORA task, we developed a rubric scheme that describes the aforementioned specific features of the websites linked in the task, for instance in terms of credibility and trustworthiness of the information they contained (for details, see Section Scoring Rubrics). To develop the psychological stimuli encountered in CORA tasks (in accordance with the construct definition; Section Construct Definition of Critical Online Reasoning), we based our approach on a specific classification of misinformation by Karlova and Fisher (2013) and on classifications of evaluative criteria of information quality (e.g., topicality, accuracy, trustworthiness, completeness, precision, objectivity) by Arazy and Kopak (2011), Rieh (2010, 2014), and Paul and Elder (2005).

Cues indicating trustworthiness or lack thereof were systematized in evidence strands according to the Information Trust model (Lucassen and Schraagen, 2011, 2013). The model distinguishes evidence on author, content, and presentation, which are aligned with classical routes of persuasion in rhetoric; each requires a different evaluation process. We expand this model by a distinction of personal evaluation vs. trust in a secondary source of information (Table 1).

The task difficulty level was gauged in particular by the scope and extent of misinformation based on an adaptation of the Hierarchy of Influences model by Shoemaker and Reese (2014), which assesses agents in the media production process and their relative power to shape the media message—and hence introduce error or manipulation, which need to be judged by students to discern the limits of warranted trust (e.g., at the bottom end are obvious deceptions and errors by the author such as SPAM emails or simple transcription mistakes in a paragraph, while at the top end are high-level secret service operations or a society-wide cultural misconception).

Task difficulty in terms of required argumentative reasoning in CORA was varied in three ways: (1) Scaffolding was added to the task prompts by asking students only for part of the argument (e.g., only pro side, con side, or only specific sub-criteria) to reduce the necessary reasoning steps. (2) The stimuli websites were selected by controlling for (i) scope and (ii) order of bias or misinformation, and for how difficult it is to detect it. Scope refers to the comprehensiveness of biases or misinformation based on the adapted Hierarchy of Influences model by Shoemaker and Reese (2014). The order is the level of meta-cognition that needs to be assumed in relation to a bias or misinformation. (3) The composition of sources that can be consulted for information (i.e., number of supporting and opposing, or high-quality and low-quality sources) can again be modified only in a closed Internet-like environment (Shavelson et al., 2019; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019), but it can hardly be controlled for on the open Internet.

The natural online environment used in this assessment constitutes a crucial aspect of the CORA task difficulty (that is also related to the reliable scoring of task performance; Section Scoring Rubrics). In a closed information environment with a finite number of sources, a comprehensive evaluation of all sources is possible. On the Internet, an indefinitely large number of sources are available. Hence, when solving the CORA tasks, students also need to constantly decide whether to continue examining a selected source to extract more information (and how deeply to process this information, e.g., reading vs. scanning) or whether to attempt to find a more suitable source, and a sample of search hits on a search engine results page, and whether they should use different search terms or even switch to a more specialized search engine or a specific database that might yield more useful information. This aspect is related to the student model and the primary aim of students in the context of inquiry-based learning based on online information, which is to gather information to “fill” their knowledge gaps while carrying out a task. Learning in an online environment requires students' initial (and later updated) understanding of the problem in relation to a specific generic or domain-specific task, and recognition of the types of information that are needed to solve a given problem, and then carrying out the steps to locate, access, use, and reason based on information, and finally formulate an evidence-based solution to the problem.

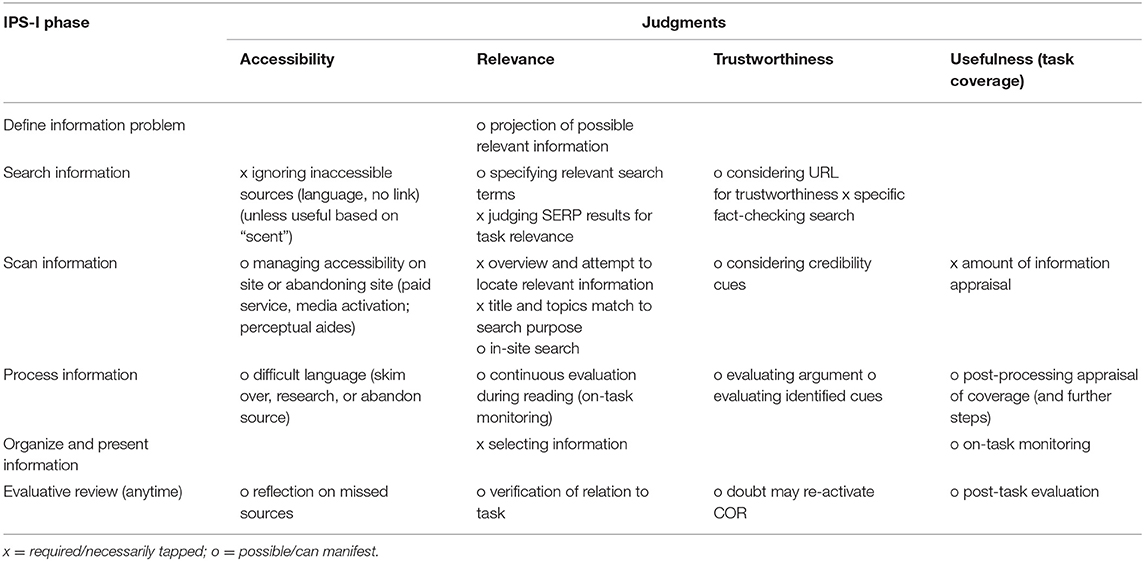

Student Model

The expected response processes while solving the CORA tasks can be described with a focus on their basic phases based on the abovementioned Information Problem-Solving using the Internet (IPS-I) model (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009): (1) Defining the information problem, (2) Searching information, (3) Scanning information, (4) Processing Information, (5) Organizing and presenting information. These phases are quite common in many other models and categorizations of information search and also media and digital literacy (e.g., Eisenberg and Berkowitz, 1990; Fisher et al., 2005). For a multi-source information problem, we expect that the processes will be iterated for each new source. An additional meta-cognitive Regulation component guides orientation, steering, and evaluation, and can be active throughout interacting at each phase (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009). Required judgments of information trustworthiness can be situated in the meta-cognitive component of evaluation. Within the evaluative process, trustworthiness judgments might be juxtaposed with judgments of accessibility, relevance and/or usefulness at several points in addition to the ongoing collection of information for the inquiry. Based on these categorizations, we developed a fine-grained description of the (sub)processes the students are expected to perform while solving the CORA tasks (Table 2).

Table 2. Possible and necessary processes contributing to quality criterion judgments, with web content considered, attributed to IPS-I phase (on evaluative review, see CORA-MCA and IPS).

In the following, we describe the student model with regard to the four main COR facets in more detail.

In CORA, the test takers are required to produce an argumentative conclusive written response based on the consulted and critically evaluated online sources. In line with the older IPS model (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2005), we have added a reflective metacognitive review as an expected process, which may occur at any moment but possibly upon response verification, to highlight that COR may be activated even after an iteration of the IPS-I process or after the whole CORA task has been completed without critical consideration.

Judgments of usefulness, accessibility, relevance, and trustworthiness of online information can be attributed to the COR facet CIE that is represented as a (meta-)cognitive evaluating component in the IPS-I model. A judgment may require a more elaborate evaluation based on additional information searches. Hence, we assume that a spontaneous trustworthiness judgment can occur at any stage in the IPS-I model. Additionally, a more deliberate, likely criterion-based, reflective evaluation of information, for instance in terms of its trustworthiness, can be performed as a specific (scheduled) sub-stage—if the student is aware of the need to evaluate the information.

The sections in the IPS-I process for evaluations of trustworthiness and other judgments also indicate that they can be interwoven with comprehension and reasoning activities and with each other (Section Construct Definition of Critical Online Reasoning, Figure 1). However, they are also likely to be distributed across several stages and differ in the content of partial evaluations and possible inferences drawn. The more detailed view of judgments and evaluations by search phase indicate that several judgments are likely to occur per phase and judgments of accessibility, relevance, trustworthiness, and usefulness are differentially important across phases and touch upon different sub-questions per phase. For instance, trustworthiness evaluations can be both fast, if an exclusion criterion is found, or gradual over one or several stages, including the collection of multiple cues. We assume this to be the case for information and sources that students evaluate as part of the CORA task. For other additional sources found during web searches, it is likely the student will evaluate trustworthiness just once and with little effort, i.e., heuristically, if they know they can go back to searching a more trustworthy source faster. (i.e., it is not the student's intention to find and determine every untrustworthy source on the Internet, but find one that is not untrustworthy and meets their needs). We therefore expect that the CORA tasks tap a judgment of trustworthiness, including either a systematic criterion-based evaluation (to the extent to which the test-taker is aware of criteria for trustworthy or untrustworthy information) and/or a vigilant recognition of the specific information features that may help the participants identify bias and misinformation.

In this context, the Information Search Process model (Kuhlthau, 1993) links behavior, cognition, and affective responses, with cognition being characterized by gradations of self-awareness regarding information search process (Figure 1). Here, again, we assume multifold interrelations with the metacognitive facet of COR. Therefore, we expect that recognizing a cue in the linked information in the CORA task (i.e., stimuli), indicating possible bias or misinformation, may activate a “vigilance state” in the students and lead to certain (subconscious) reactions (and a habitual affective response, e.g., anxiety, excitement) or can also be interpreted as an indicator of a potential problem (“am I being lied to?/at risk after misjudging the information?”) at the metacognitive level, which may lead to the activation of the facet of COR, i.e., (meta)cognition for critical reasoning activation (on the role of uncertainty and emotions when searching for information, see Kuhlthau, 1993). In this regard, we consider the ambiguity experience as the initial stage in a general critical reasoning and evaluation process, i.e., a cognitive appraisal marked by uncertainty about the validity of one's interpretation of the current situation that leads to a need for more clarity (or to avoid the problem-solving situation, e.g., in case of a low self-efficacy), which may prompt an expected response behavior during the CORA tasks, i.e., critical reflection and evaluation.

In terms of the task model, this ambiguity is tapped by the CORA task description and the prompt, which explicitly asks students to judge the trustworthiness of a given website or claim. Thus, the task prompt is the initial stimulus for students to activate their trustworthiness evaluation since the question of whether or not information is trustworthy is explicitly given by the task prompt; the second are the cues offered by the stimulus materials embedded in the CORA tasks; the third is the reminder in the response field of the CORA task to formulate a short statement to the task questions and to list the consulted online sources (Section Scoring Rubrics). The CORA task prompts explicitly require students to formulate a response, justify it with reasons and arguments, and back these up by citing URLs of sources used to reach their decision. Thus, students' responses comprise the fundamental components of argumentative reasoning (Section Theoretical Components of COR). In CORA, we framed the trustworthiness evaluation through an argumentative model, and modeled (possible) stances on a (trustworthiness) issue and their supporting reasons and evidence (cues). Alternatively, students might not reason deeply about it, but apply cognitive heuristics (Kahneman et al., 1982; Metzger and Flanagin, 2013). However, given that it is explicitly prompted in the task, we expect students to apply argumentative reasoning and to be able to identify cognitive heuristics (e.g., authority biases) within their argumentation.

In this context, one aspect is particular important in terms of the interpretative model (Section Scoring Rubrics). Assuming that cognitive biases (e.g., confirmation bias), and motivated reasoning can be tapped by controversial topics as presented in the CORA tasks, an opposing stance toward a given topic (i.e., skeptical) affords more stimuli to be critical and motivates the student to find evidence of misinformation. This is why a balanced selection of various topics was established in CORA. We assume students' initial personal stance on the task and its topic will depend on a number of influences, controlled for in CORA (e.g., prior domain knowledge, attitude toward the task topic). This aspect is crucial since students may pass different credibility judgments and follow diverse reasoning approaches depending on their initial stance (Kahneman et al., 1982; Flanagin et al., 2018). At a later, longitudinal research stage (e.g., in the context of formative assessments; Section Analyses of Response Processes and Longitudinal Studies), attitude-dependent tasks can be administered to assess COR levels among students for topics they explicitly support or oppose. Not solving the task in a way that accounts for both perspectives would therefore yield a lower CORA test score (Section Scoring Rubrics). This in turn would strengthen the high ecological validity of CORA.

Whichever stance the students choose, they will not be awarded points unless they provide warrant through reasons and arguments, and back them up with evidence from the evaluated website and further consulted online sources (Section Scoring Rubrics). Thus, an evaluation supported by reason and evidence (such as a link to an authoritative website), judged by raters as acceptable against a generic or domain-specific quality standard, is used to infer the extent to which students' have critically reasoned with and about online information. The call to justify is explicitly prompted in the task (“provide a justification”) and the backing with evidence is required in a separate field, asking for the URLs of consulted further websites. Providing citations is a common form of evidence in academic writing, and copying a URL does not require an elaborate evidential standard. The reasons and arguments students cite in their written responses are scored for plausibility and validity based on a few rules (e.g., “trusting only the source's own claims about itself is not sufficient reason”). The indicated URLs are also evaluated in terms of their trustworthiness (Nagel et al., 2020). We assume that students with advanced COR abilities cite only the best sources they found and used to back up their argument. Conversely, indicating many relevant and trustworthy sources as well as irrelevant and untrustworthy ones was considered an indicator of reasoning that was not fully sufficient (see scoring rubrics in Section Scoring Rubrics).

According to the fundamentals of argumentation, the main claim, reasons, and backing (e.g., evidence) are the basic elements of a reasonable argument (Toulmin, 2003; Walton, 2006). Hence, we considered indications of these, which are also explicitly prompted in the CORA task, in a somewhat aligned manner in the students' responses as evidence that students performed argumentative reasoning. Some argumentation frameworks include further basic components, such as rebuttal and undercut as types of opposing reasons or inclusion of consequences (Toulmin, 2003). These components can be included in further CORA tasks (Section Refining and Expanding CORA), but were not required for the short online evaluation tasks. Moreover, in terms of metacognitive evaluation, students are expected to engage the evaluative critical reflection, i.e., “self-reflective review” of their task solution after formulating their response to the task.

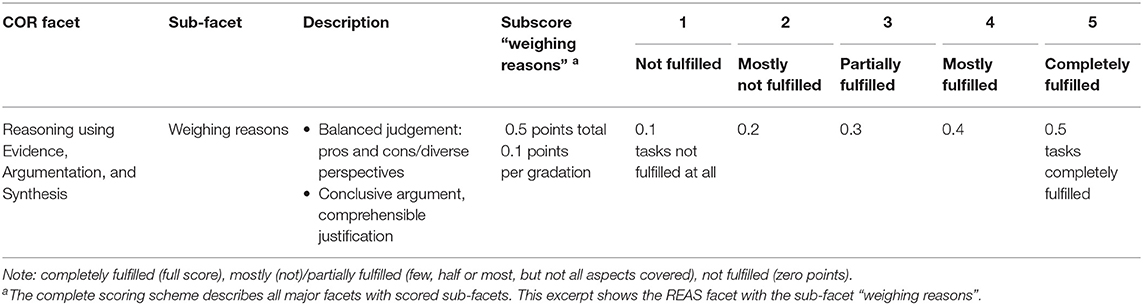

Scoring Rubrics

According to the task and the student models, CORA tasks measure whether students employ critical evaluation of trustworthiness and critically reason based on arguments from the online information they used. Based on our prior research on performance assessments of learning (e.g., for the international Performance Assessment of Learning (iPAL) project, see Shavelson et al., 2019) and the developed scoring approach, we created and applied new scoring rubrics focusing on the main facets of COR and on fine-grained differentiations of scoring subcategories in accordance with our construct definition (Section Construct Definition of Critical Online Reasoning; for an excerpt of the facet “weighting arguments,” see Table 3).

Each task is scored with a maximum of 2 points, with to 0.5 points awarded if the response mentions a major bias or credibility cue, for instance noticing a (covert) advertising purpose, and if its implications for the interpretation of information are identified. Up to 0.5 points are awarded if the students support their claim (no matter which stance) with one or two valid reasons that are weighted in relation to each other, and a maximum of 0.5 points if students refer to one or two credible external sources (that are aligned with their overall argumentation). Furthermore, students can achieve 0.5 points if their response is coherent, clearly related to the task prompt, and covers all sub-parts.

In contrast to a simple trustworthiness judgment, which could be performed without further reflection using heuristics, the underlying analytical reasoning requirements of the tasks are more demanding. It is also possible for participants to take the evidence for their criticism of a website from the website itself as long as the argument is warranted and conclusive. Consequently, the scoring rubrics also consider to what extent the students recognize the specific characteristics for or against the trustworthiness of certain websites, cues, and strands of evidence, and whether they consider them in their reasoning and decision-making processes. A student may identify manipulative techniques “X” and “Y” being used by the linked website, which make it untrustworthy, and cite them from the website. In this case, students can receive points for correctly judging the website as unreliable and for identifying a bias, even if they have not accessed external websites. In a follow-up study, in addition to this holistic score per task, further sub-scores can be awarded at different levels of granularity in accordance with the COR construct definition (Section Development of Scoring Modular Rubrics).

Regarding information trust strands of evidence, before scoring this aspect of students' responses, we evaluate the stimuli in the CORA tasks in terms of type, number, and location of cues for/against the credibility of a website (Section Test Definition and Operationalization of COR: Design and Characteristics of CORA). In addition to evaluating the stimuli individually, we mark their valence and importance for main argumentative claims (e.g., supporting or contradicting the trustworthiness of the linked website). Given the large number of possible cues, we make some systematic limitations: the collection of cues is mainly restricted to the stimulus materials to be evaluated by all participants. These cues are listed and scored depending on how frequently they are mentioned in the students' argumentative responses (i.e., focus on cues that students selected). In terms of possible verification of plausibility of reasons, we distinguish first-order reasons (e.g., “the website has an imprint”), which may lead to a successful judgment in certain cases and guard against some deceptions if only cues regarding credibility are used, to second-order reasons (e.g., “any website can have an imprint nowadays, but the indicated organization cannot be found online”).

Further, the cues were systematized following three strands of evidence in accordance with the 3′S Information Trust model (Lucassen and Schraagen, 2011) and Prominence Interpretation Theory (Tseng and Fogg, 1999), including surface/design, semantics/content, and source/operator. Each of these strands can make a specific contribution to an argument about whether to trust information or not. Moreover, they address different reasoning approaches from “aesthetic” appraisal and consideration of mediated presentation, to content and argumentative appraisal as well as to consideration of authorship reputation, intent and expertise (and other cues of the production/publication process).

In addition to the described strands of evidence, the model was expanded by distinguishing a primary- and a secondary sources perspective for each strand. Usually, both perspectives will be used to some extent for an evaluation of trustworthiness, i.e., when verifying a cue oneself, evidence standards (standards related to the information itself) are used than when relying on other persons' judgments (here, one rather uses standards related to the probability of successful judgment of the other person). For example, when judging trustworthiness of the author, a student may complete their own research on relevant aspects from a variety of biographic sources or they may follow a journalist's understanding of this author. Verifying every aspect oneself marks a fully autonomous learner, though we acknowledge that this may not be feasible for all aspects in the short test-taking time. For each task, strands containing important cues were listed. Moreover, major distractors supporting a competing assumption were marked.

The rating was carried out by at least two trained scorers per task. For the overall CORA test score, i.e., the average scores of two or three raters for each participant and for each task, a sufficient interrater agreement was determined, with Cohen's kappa >0.80 (p = 0.000).

Preliminary Validation

The validation of the CORA was integrated with the ECD and follows the AERA Standards (Section Research Objectives and Questions). Starting from the holistic nature of the CORA (see section Task Model), the construct specification, and the modular extensions of the scoring in this paper (see Interpretative Model), we present preliminary validity evidence related to the content of the construct. After the COR construct specification and the assessment design, the newly developed CORA tasks underwent content analyses and were submitted to expert evaluation during interviews. The aims were to examine the coverage of the theoretically derived COR construct facets by the holistic tasks and to obtain expert judgment regarding the suitability of the content and requirements for higher education in Germany. Below, we outline the methodology (Sections Content Analysis: CORA Task Components as Coverage of the Construct and Expert Interviews) and discuss the results for both analyses (Section Findings From the Expert Interviews and Content Analysis).

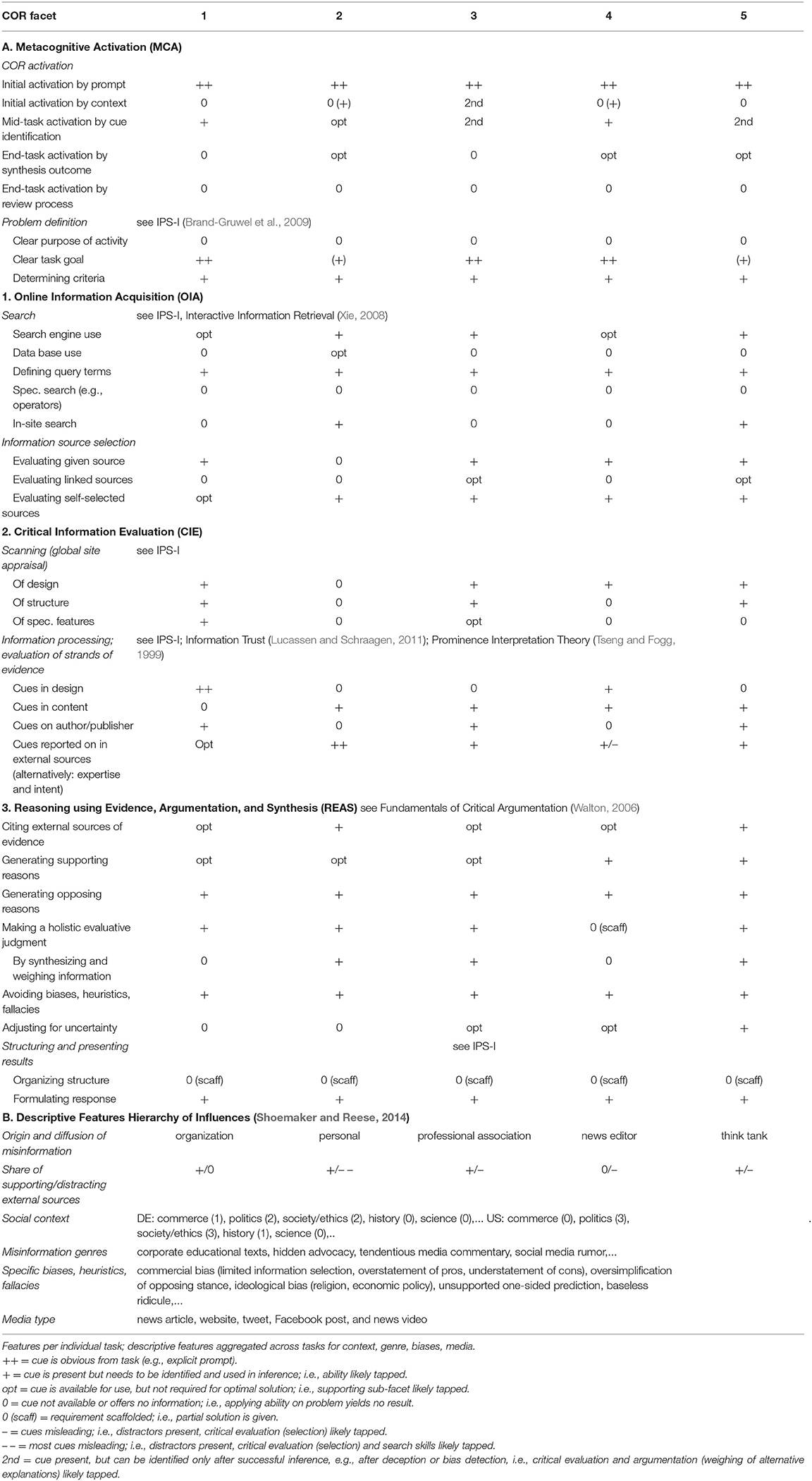

Content Analysis: CORA Task Components as Coverage of the Construct

A qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2014) of the CORA tasks was carried out by the CORA research team members who participated in the construct specification but not the selection of task stimuli. Task prompts and the encompassed stimuli were examined to determine the presence or absence of features that would allow test-takers to draw inferences and generate responses worth partial or full credit according to the scoring rubric (Section Scoring Rubrics). The six higher education CORA tasks that resulted from the design process (Section Test Definition and Operationalization of COR: Design and Characteristics of CORA) were coded according the following features and underlying (theoretical) frameworks:

(1) As part of the meta-cognitive facet, activation of COR was coded to gather evidence on whether the tasks tap students' overall COR ability, i.e., whether they convey a need for critical evaluation and argumentative reasoning and at which point: at the beginning, middle or end of the task. We coded for activation by prompt or by context, by specific cues that would highlight the need for COR during task processing, and for end-of-task activation by required (metacognitive) review steps or invited by a contradictory or uncertain preliminary conclusion. The expectation was that at least some tasks would have a cue for COR activation at the beginning of the task, whereas others may only have a mid-task activation to tap students' ability to identify situations when it is needed to activate their COR.

Moreover, the aspect of problem definition (in the sense of the IPS-I model, Table 2) was examined. We coded whether the task was embedded in a broader activity context to support judgment based on purpose and increase ecological validity (e.g., judging information trustworthiness for use in a term paper); in a pretest during task design, students had claimed to apply more or less rigorous evidence standards depending on purpose. We also coded whether the task goal was clearly stated in the prompt and whether solution criteria were given or if they needed to be inferred.

Other MCA subfacets regarding regulation, affective response, or attitudinal aspects were not coded due to the difficulty of assigning them to specific task features (in the online assessment); these could be elicited more efficiently in a future coglabs study (Section Analyses of Response Processes and Longitudinal Studies).

(2) The OIA and CIE facets were assumed to be organized in order of the phases of the IPS-I process model to highlight similarities and differences among the CORA tasks, while specific features were coded based on other additional models and research foci (Section Scoring Rubrics). The phases of source selection and initial scanning of a website were listed under one facet (OIA or CIE), but are expected to be hybrid search and evaluation activities (to be further examined in coglabs; Section Analyses of Response Processes and Longitudinal Studies).

Among the search-related aspects (OIA), we coded the necessity to use different search interfaces during the process (e.g., a search engine, in-site search) to obtain reliable information. We assumed that basic search skills, but not use of advanced search operators or special databases would be required. Websites that were inaccessible and media that would not play or were too long and not searchable were excluded during the pretest. Hence, suitable information was expected to be fairly easy to locate and access (except on specific search tasks) by performing an external search.

Regarding information source selection, we generally coded the sources students had to evaluate to obtain suitable information, i.e., the given website, additional websites, and linked sources (e.g., a background article to a tweet), and/or websites which students selected themselves. We expected requirements to vary across tasks.

(3) The facet of CIE united the IPS-I phases of scanning a website and in-depth information processing. For global website appraisal and orientation, we coded to what extent it was necessary to judge the overall layout and design (or if one could ignore the context and start reading/searching immediately), to what extent students needed to get an overview first, for instance to find a suitable paragraph in time by scanning sub-headings, and determine if they had to attend to any specific cues rather than reading the main text. We expected that some websites might have obvious design cues and others might not (e.g., a popular social network could be interpreted as an obvious cue for lower credibility); some websites were expected to be more complex or longer and require initial orientation; however, we expected students to find relevant information on the given landing page and standard sub-pages (e.g., publisher and author listed in the legal notice or “about” page); we expected the task solutions to not be based solely on the identification of a single cue.

Regarding information processing, we generally assumed the required reading comprehension to be a given among higher education students and focused on evidence evaluation, classifying available cues based on the 3‘S’ Information Trust model (Lucassen and Schraagen, 2011) into cues in the design, content, or source, as well as (jointly for all three) secondary external sources indicating cue evaluations (Deferring judgment to external sources would also require an evaluation of these sources' expertise and intent). For example, if a website had aggressive popup advertisement, this would be coded as a cue in the design that might indicate lower trustworthiness. We expected that not all tasks would have cues for (un)trustworthiness in all strands, but at least in one strand of evidence. Moreover, different strands of evidence would be tapped across tasks so that no single subset of evaluation skills or strategy (e.g., only using logical critique or looking up the author's reputation) would be universally successful.

(4) Based on major components of reasoning (Walton, 2006) with evidence, argumentation and synthesizing (REAS), we coded to what extent students needed to cite sources of evidence (expected), to what extent they had to provide reasons why they trusted the information (on some tasks), or arguments against its trustworthiness (expected), to what extent they needed to make an overall evaluative judgment (expected), and to what extent they had to synthesize and weight possibly contradicting information and arguments (expected), to what extent stimulus materials contained a prominent bias, mismatched heuristic, or fallacy to be avoided (expected for most tasks), and if there was a clear-cut solution vs. an undecidable outcome so they had to account for uncertainty (only on few tasks).

In regard to presentation of results (another IPS-I phase), we coded to what extent the quality of the structure and phrasing of students' responses contributed to their score. As we focused on the quality of argumentative links and information nodes rather than their rhetorical arrangement, we expected response structures and phrasing to not matter beyond the general effort of presenting a coherent and conclusively argued response.

(5) In addition, given that domain- and topic-dependent prior knowledge (and attitudes) might influence participants' searches, evaluation, and reasoning, we collected some descriptive information on the task topics: We labeled the origin of the misinformation as an indicator of how widespread and hard to identify a deception might be (e.g., from a single author's error on a page to a newspaper editorial board's agenda-setting policy to a culturally normalized conviction), as suggested by the Hierarchy of Influences model (Shoemaker and Reese, 2014). We coded the share of supporting and opposing (in terms of the task solution: conducive or distracting) search results for the key terms in the prompt and website title (as an indicator of controversy and how easy it was to find additional online information). We labeled the broader task context in terms of societal sphere (commerce, science, history etc.), the kind of misinformation genre, specific biases, heuristics, and fallacies presented, and the type of online medium. The overall expectation was that CORA tasks would present one or two challenging aspects but not be overly difficult given the short testing time (e.g., no national scandal to be uncovered), and would be varied in their genre and contexts. Results are summarized in Table 4.

Expert Interviews

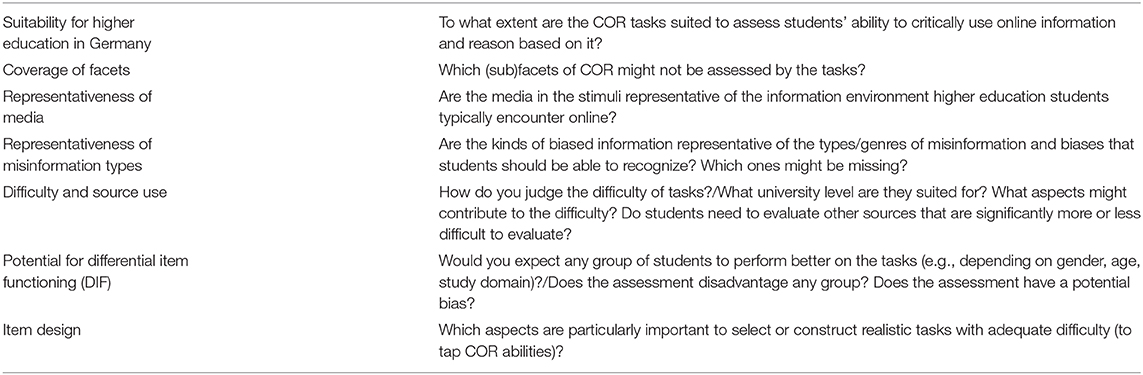

Semi-structured expert interviews (Schnell et al., 2011) provided a second source of evidence on content representativeness. In semi-structured interviews with experts, we presented examples of CORA tasks and asked experts to comment on their suitability for higher education in Germany. The interviewed experts were leading academics in their field and included two of the U.S. developers of the civic online reasoning assessment, four experts in computer-based performance assessments in higher education, and six scholars from the fields of media studies (who focus on online source evaluation or media literacy), linguistics, and cultural studies. After considering the task stimuli, prompt, and rubrics (sent to them in advance), the experts were given the opportunity to ask for clarifications and were then asked to share their first impressions of the assessment before responding to more specific questions regarding the tasks and features. The discussed topics are shown in Table 5.

The questions were asked in view of the German context and tasks specifically, since the media landscape and typical challenges with online information, including deception strategies, can be country-specific. Experts' responses were interpreted in light of their disciplinary backgrounds and convergence or divergence between experts.

Findings From the Expert Interviews and Content Analysis

In the following, we present a summary of the main findings from the expert interviews and content analysis.

Overall Experts Evaluations

Overall, with regard to the suitability and validity of the CORA tasks for higher education in Germany, most experts agreed and confirmed the content and ecological validity of the CORA tasks and recommended further expansions. For instance: “The task is clear, the instruction is also clear, and it seems obvious that they need to formulate a response.”

One expert, after pondering how to translate and adapt the U.S. tasks, and worrying about cultural suitability, considered the CORA tasks and commented: “These [German] tasks are really a hundred times better for Germany.”

Coverage of COR Facets

One question critically discussed with experts addresses the domain-specificity of the CORA tasks. Here, the experts confirmed that the six tasks cover generic COR ability. For instance: “No domain-specific knowledge is required. It's a good selection for the news/science context.”

One concern that was raised by most expects regards the suitability of the testing time to assess all facets of COR, and in particular the REAS facet. However, experts also agreed that students may not dedicate more time to the task when evaluating an information source in a real setting. As one expert notes: “There are 10 min to conduct a search. One may doubt if people would commit as much time in everyday life, unless they really took the time to carry out a more detailed search.” At the same time, the natural online environment of the assessment was praised in terms of the high ecological validity of CORA by all experts: “The mode of administration as given here is important, since it enables assessing internet search behavior.”

The new rating scheme with the subscores and evaluation categories was positively evaluated by the experts, although they stressed the high complexity of the scoring rubrics. For instance: “It is also good that you have different degrees, not only “right or wrong.” Of course, this places high demands on coders, but with training, it is doable.”

Representativeness of Media

Most experts positively evaluated the representativeness of the chosen media, i.e., media that students frequently use online. However, one expert criticized that “scientific and journalistic media were indeed covered, but the selection could include more reputable media as well as some media more on the lower quality end of the spectrum. The ones here are well chosen; one cannot immediately tell if they are fabricated or not.” Another expert proposed: “These are common media sources. However, you may include even more social media, and not only evaluate news by institutions and organizations, but also by individual users or from the “alternative” news outlets. Influencers on Instagram who present products are another option.”

Representativeness of Misinformation Types