- 1LiberatED, Oakland, CA, United States

- 2Institute for Racial Justice, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3College of Public Health and Human Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, United States

- 4Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, and Special Education, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Introduction: Social and emotional learning (SEL) has been identified as one approach to promote positive mental health outcomes while alleviating the stressors of systemic racism and a global pandemic. As the United States turns to SEL as a remedy for mental health challenges and the current civil unrest, it becomes increasingly relevant to understand what SEL means to those who use it the most to strengthen the implementation of current programs as well as to inform the development of new programs to fill existing gaps.

Methods: This abductive qualitative study expands prior research by exploring how in-service educators define SEL (N = 427).

Results: Our findings highlight that educators perceive SEL as more expansive than current competency-based models. Educators describe SEL as a praxis that can be responsive to student and community needs, facilitate healing, and center humanity along with racial and social justice.

Discussion: We discuss implications that highlight the potential risks and harm that can be perpetuated by the current practice of SEL and, like the educators in our study, advocate for dismantling white supremacy structures in education through the co-creation of a humanizing SEL approach.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a sense of urgency for the nation to address existing and new mental health needs. The lives of many young people were upended with school closures and reopenings (Youth Truth, 2021), inconsistent messages about pandemic protocols, and, for some, illness or loss of loved ones. As a result, many youth experienced heightened stress, anxiety, and depression (Fair Health, 2021; Mott, 2021; Varma et al., 2021). Alongside the pandemic, there was increased focus on racist violence (Curtis et al., 2021), which contributed to additional anxiety, fear, and angst. The coronavirus pandemic and civil unrest contributed to more pronounced racial tension (Barret, 2022). Youth who already experienced systemic marginalization [e.g., Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), youth in poverty, students with disabilities, or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth] were particularly vulnerable to mental health challenges and pandemic-related stressors (OECD, 2020; Reliefweb, 2020; Vasquez Reyes, 2020). It is worth noting that some young people did better in the face of these challenges. For instance, youth who were removed from oppressive school contexts no longer experienced daily exposure to hostility, discrimination, and microaggressions to the same degree (Miller, 2021). Youth in supportive homes developed a stronger sense of identity and critical consciousness during the periods of remote learning (Miller, 2021). For youth to thrive, during a pandemic or otherwise, they need to learn in environments that support their whole selves, promote their well-being, and are free from harm.

To respond to the challenges of both the pandemic and civil unrest, there were calls for schools to bolster commitments to mental health and diversity, equity, and belonging (Jones et al., 2022; Rutgers Center for Effective School Practices, 2022). Many school districts and policymakers advocated for social and emotional learning (SEL) programming, which aims to foster life skills that support people in experiencing, managing, and expressing emotions meaningfully, making sound decisions, and fostering rewarding interpersonal relationships (Modan, 2020; Sanders, 2020). The Office of Child Care Initiative to Improve Social–Emotional Wellness of Children published a guide recommending SEL as a strategy to help meet the needs of students (Childcare Technical Assistance Network, 2021). Thirty-eight states referenced SEL in their response plans to the pandemic (Yoder et al., 2020). With an uptick of attention to SEL, many prominent SEL organizations and programs including the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) and the Social and Emotional Learning Alliance for the United States (SEL4US) responded by producing webinars, online courses, and resources for educators. CASEL produced a roadmap to infuse SEL and mental health promotion as schools reopened amidst COVID-19 [Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), 2020a,b].

Although the pandemic heightened awareness of SEL’s importance, SEL had already been gaining traction among school communities for decades because of growing evidence of its short- and long-term benefits for students including enhanced relational skills and attitudes, improved academic achievement, and reduced anxiety, stress, and depression (Durlak et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2017). Generally, SEL programs are designed to be implemented as a complement to other school curricula by teachers trained in their use. Schools can choose from many SEL programs, most of which generally share the goal of enhancing a range of social and emotional skills (e.g., understanding one’s own and other’s emotions). Many SEL programs follow a widely-adopted SEL framework proposed by CASEL, which categorizes SEL into five competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social-awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (Lawson et al., 2019; Frye et al., 2022).

Founded in 1994, CASEL published the first major book on school-based SEL programming in which they identified a research-based framework for implementing effective programs for building SEL (ASCD, 1997). The framework eventually evolved into the CASEL 5 SEL Competencies Framework (hereafter referred to as the CASEL 5) and has been widely adopted across the SEL field and schools across the nation. For example, 20 large school districts, serving 1.7 million students, have used the CASEL 5 to establish preschool to high school SEL standards that articulate what students should know and be able to do [Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), 2021]. The CASEL 5 has also been used to guide the development and evaluation of many school-based SEL approaches and research, thus shaping educational practice [Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), 2013a,b].

Although the evidence supporting the effectiveness of SEL programs continues to grow, there has been some critique that SEL alone is not enough to address the current educational and societal climate without a commitment to confront and eradicate racist practices, policies, and curricula (Simmons, 2021). Some argue that SEL without a racial justice lens could contribute to the continued harm and dehumanization of our nation’s BIPOC students, who continue to be systemically and institutionally oppressed (Camangian and Cariaga, 2021; Simmons, 2021). As SEL programs have been identified as falling short in addressing social and racial justice, scholars have criticized SEL for perpetuating and upholding systems of oppression and contributing to harmful narratives about the need to “fix” BIPOC youth (e.g., DeMartino et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2022). Given the education system in the United States (U.S.) is based on tenets of white supremacy (Brooks and Theoharis, 2018) and that our nation’s schools serve mostly BIPOC students (Riser-Kositsky, 2019), SEL faces the risk of becoming “white supremacy with a hug” (Madda, 2019; Simmons, 2021) without dedicated efforts to combat racial and social injustice (Simmons, 2019b). There is an urgent need for antiracist, culturally affirming, and responsive SEL that centers educator and student voices (Abolitionist Teaching Network, 2022; DeMartino et al., 2022). Calls for fearless SEL (Simmons, 2019b) and transformative SEL (Jagers et al., 2019) have pushed the SEL field to be more equity-responsive.

While SEL holds promise for improving mental health outcomes among youth (e.g., Weare, 2017; Grové and Laletas, 2020), SEL programs may not always be implemented effectively for all students in the current sociopolitical context of the United States (Forman et al., 2022; Leonard and Woodland, 2022). Many SEL programs have small to moderate effects with effectiveness varying widely across contexts and populations (Durlak et al., 2011; Boncu et al., 2017). Even the use of the same program can lead to variability in outcomes depending on the fidelity of implementation as well as the unique needs of the students and educators (e.g., Hunter et al., 2022). Few programs have collected data on what is working, for whom, and in what contexts. Fewer still have explored in-depth fidelity data to understand differential effects although research in this area is growing (Thayer et al., 2019). As the nation turns to SEL to support young people’s mental health in the midst of a pandemic and social unrest, it is imperative to understand what SEL means to those who use it most to strengthen its implementation and to inform the development of new programs and practices that aim to fill existing gaps.

Educators and other school personnel have often been left out of the creation of widely-used SEL approaches. Thus, exploring how educators and other school staff define and practice SEL is an important step toward understanding how best to support students in a way that honors their lived experiences and identities while recognizing their needs. This qualitative study fills this gap and expands prior research by exploring how educators define SEL. We believe that educators are important partners in the creation of curricula, student learning experiences, and the classroom environment, and that their perspectives are vital not only to their students, but also to the education field. This study provides an opportunity to understand how educators’ perspectives of SEL align with predominant SEL conceptualizations and program implementation.

Research design

We approached this research based on the insight of Indigenous scholars, who argue for centering and honoring the wisdom of communities of study and for relational accountability between researchers and study participants (Tuck and Yang, 2012; Wilson, 2020). Relational accountability requires that researchers engage in respectful and mutually beneficial relationships with study participants (Wilson, 2020). Thus, we employed a community-based research design both to honor and respect our study participants and to gain a grassroots perspective of learning environments, where SEL facilitates belonging, healing, care, and justice. The goal of community-based research is to educate, improve practices, and bring about social change (Atalay, 2010; Tremblay et al., 2018). In the context of community-based research, “community” is not a geographic location but rather a community of interest or a collective identity with shared goals, interests, or problems (Alinsky, 1971; Israel et al., 2005). Within education, the historical roots of community-based research can be traced to critical pedagogy (Boyd, 2020). Two major proponents of critical pedagogy, John Dewey and Paolo Freire, argued that meaningful learning may lead to social change through repeated critical analysis, reflections, and actions (Freire, 1970; Peterson 2009). The work of Michel Foucault and Thomas Kuhn further informed the development of community-based research by challenging the “hierarchization of knowledge” (Ritzer, 1996, p. 463). Specifically, they raised questions of how we know what we know and what it is that we value as knowledge (Wicks et al., 2008). Their work shaped the development of community-based research to reflect “a democratization of the research process and a validation of multiple forms of knowledge, expertise, methodologies” (Boyd, 2020, p. 750).

Our research aim was to understand what SEL means to in-service educators by exploring our overarching research question: “how do educators conceptualize SEL?” In the context of this study, we aimed to address the research question through recognizing the collective voices and knowledge of educators. In line with community-based research, we conducted reflexivity practices to acknowledge how our identities, values, experiences, and attitudes influence our research (Reinharz, 1992; Israel et al., 1998). Our research team included individuals with intersectional racial, cultural, and sexual identities. Our lived experiences as students, teachers, and researchers shape our research. We practiced self- and group-reflexivity to recognize the complexities that our identities, values, and lenses posed in relation to this study. As a research team, we routinely challenged one another around the beliefs and interpretations we ascribed to the educators participating in this study.

For this study, we chose an abductive qualitative methodology, ensuring that educators’ voices were at the forefront of our research while also acknowledging the prevalence of an existing definition of SEL. Qualitative analysis enables researchers to construct understanding entirely from the data without any preconceived ideas of what they may find (Creswell and Poth, 2016). An abductive approach involves the systematic combination of both inductive and deductive methodologies (Dubois and Gadde, 2002). In this study, though we used the CASEL 5 as the foundation to build our initial codebook, we did not influence or force the data to fit into it or other preconceived conceptualizations.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

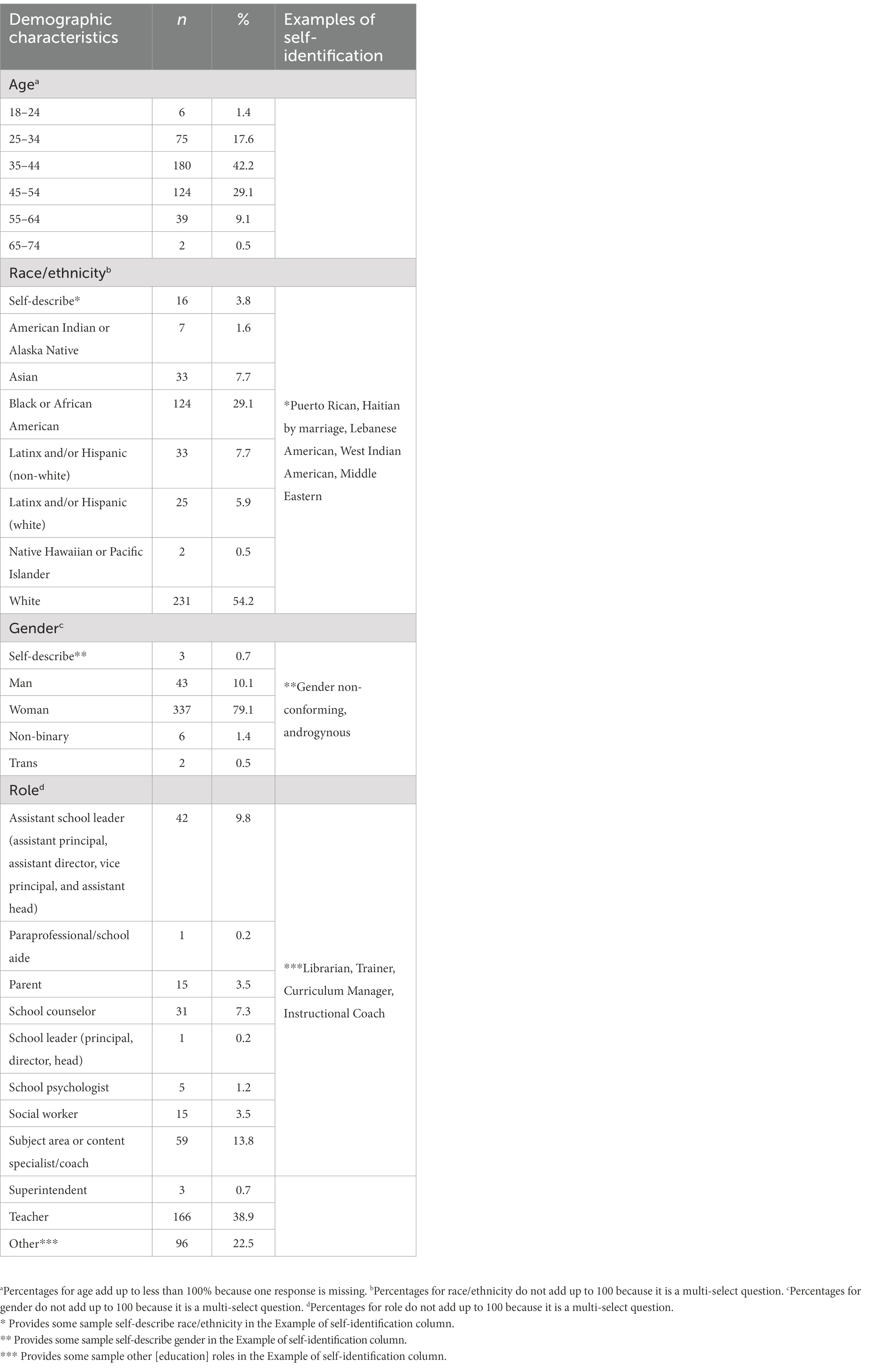

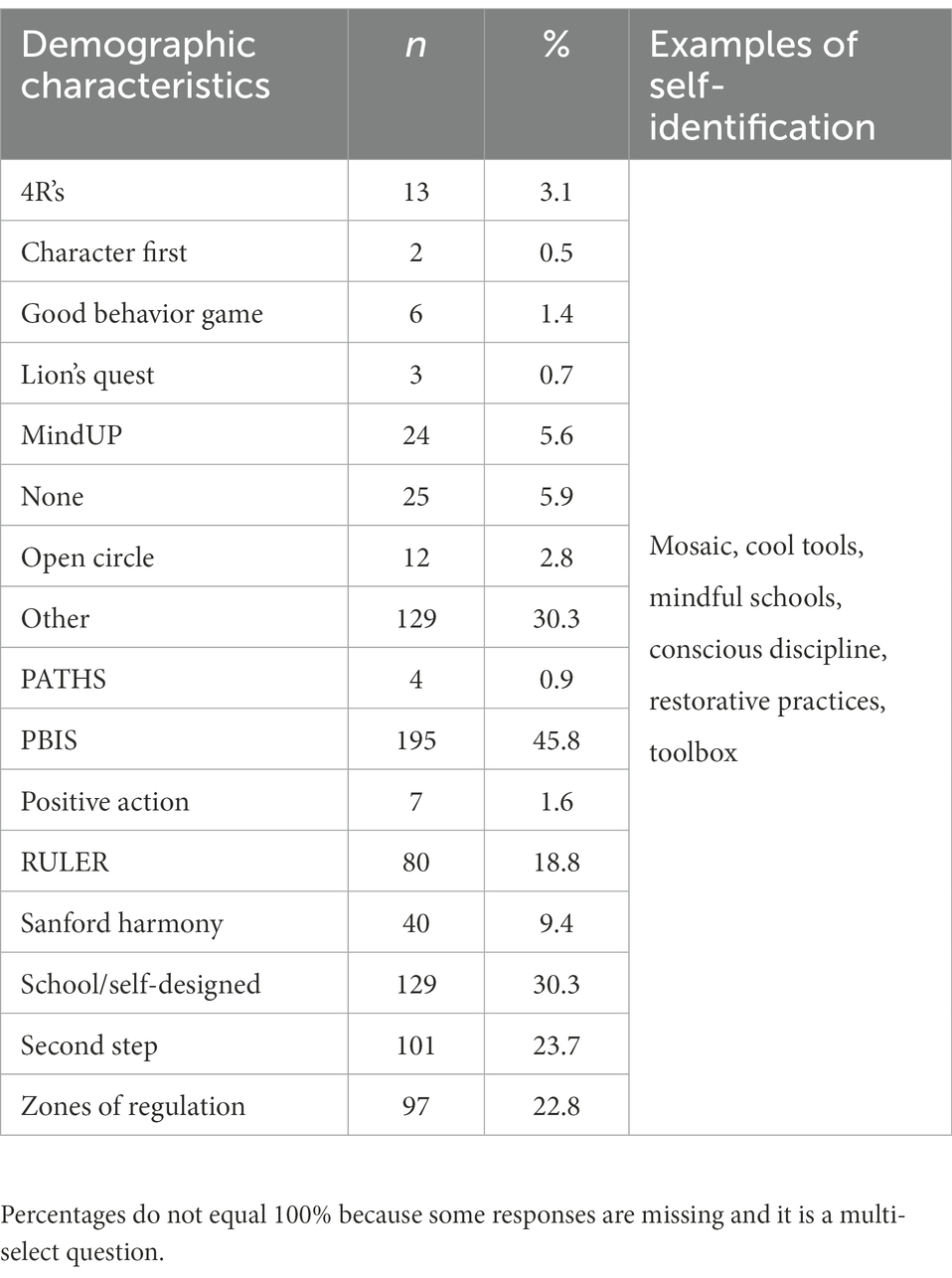

We collected data at a free virtual event in the summer of 2021 that was focused on the intersection of SEL, racial justice, and healing in educational settings. We chose participants at this event for our study because they likely shared a dedication to learning about and/or implementing and centering these topics in their educational practice. To register for the event, participants completed an online survey comprising structured-response and open-ended questions. Participants were 918 registrants who completed the registration survey. The survey took approximately 10–20 min to complete and comprised 12 structured-response questions (e.g., demographics, SEL curriculum implemented at their school) and 7 open-ended questions (e.g., participants’ perceptions of SEL). We limited our sample to only include participants who had responded to the one open-ended question related to SEL, “What does SEL mean to you?” We additionally limited our sample to those who were currently working in a pre-K to 12th-grade school setting [e.g., classroom teachers, school psychologists, school administrators, etc. (see Table 1 for a complete list) referred to as ‘educators’ hereafter] in the United States (N = 427). As illustrated in Table 1, participants’ racial backgrounds included white (54%), Black/African American (29%), Latinx (14%), and Asian (8%). The majority of respondents were female (79%), followed by male (10%), and transgender, nonbinary, gender non-conforming, or androgynous (3%). Most respondents were 35–44 years old (range: 18–74). Ninety-two percent of participants reported they implemented an SEL curriculum at their school (see Table 2).

Analyses

Two coders who are authors of this manuscript conducted the analyses for this study. To promote and attain researcher reflexivity, we wrote personal reflexivity statements about how our lived experiences and social positioning might influence how we understood and interpreted survey responses before coding (Birks et al., 2008; Creswell and Poth, 2016). The first coder is a Chinese-Canadian, cisgender, straight woman who previously taught at preschools in Taiwan and Japan. The second coder is a white, cisgender, queer woman with experience working with immigrant and refugee families and living in Spain, the Dominican Republic, and Australia. Both coders previously held research positions in an academic research center focused on social and emotional learning in educational settings.

Our first step to analysis was to create a priori codes based on the CASEL 5. We then randomly selected and reviewed 10 responses to familiarize ourselves with the type of data and develop a preliminary codebook (Miles and Huberman, 1994). We separately coded these 10 responses using the a priori codes and inductively generated new codes as they arose in the data. We wrote memos noting which a priori codes we applied, any new codes we generated, and questions or comments that arose during the review process. We then met to discuss our processes, reconcile discrepancies in our coding, and come to a consensus on an updated codebook. Once we completed this stage, we compiled the ten responses that we used for review with all other data so that these responses would also be coded during analysis.

Afterward, we conducted a thematic analysis, a process of identifying, analyzing, organizing, and reporting patterns within data resulting in emergent themes that are then refined and interpreted (Creswell and Poth, 2016). We began our thematic analysis of all data using Atlas.ti (Version 22) following the steps identified by Braun and Clarke (2006). We open-coded all data, conducting line-by-line analysis of all responses to create codes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). We derived codes from key ideas, quotes, and words that reflected participants’ perceptions. Codes were broad, multiple, and overlapping. To substantiate the reliability of the coding process, we double-coded 20 % of the data in four rounds (Seale, 1997; Bauer and Gaskell, 2000; Yardley, 2000; O’Brien et al., 2014); the primary coder coded approximately 100 responses per round and the secondary coder coded approximately 20 responses per round.

Following recommendations from Birks et al. (2008), we independently wrote memos after each coding round to note any difficult coding decisions, new codes, potential themes, and any biases that we may have brought into the process. Memos are self-reflections of a researcher’s thoughts and insights that explicitly acknowledge the subjective influences of the researcher and promote and attain researcher reflexivity (Birks et al., 2008; Creswell and Poth, 2016). We met after each round of coding. In these meetings, we merged double-coded responses in Atlas.ti, reconciled any coding discrepancies to reach 100% consensus, and identified any updates to the codebook. Before reconciling, our average Krippendorf’s alpha was 0.76 with all but the first coding round at or above 0.80, the cutoff threshold for representing good intercoder reliability (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020). We wrote memos during reconciliation to create an audit trail recording how we made decisions and reached conclusions throughout the research process (Birks et al., 2008; Speziale et al., 2011).

After our final reconciliation meeting, we went back through all previously coded data to account for changes in the codebook resulting from previous reconciliation meetings. In the final stage of coding, we clustered codes and identified groups of codes representing similar underlying constructs. These clusters became emerging themes, which we compared within and across responses, reviewing and refining themes in an iterative process to ensure they accurately represented coded material. We then shared our emergent themes with another author on this study whose expertise and lived experience as a Black, queer, cisgender woman, former middle school teacher, and current teacher educator and SEL practitioner and researcher provided important insight into refining our themes. We discussed and further clarified our themes based on this researcher’s feedback.

Findings

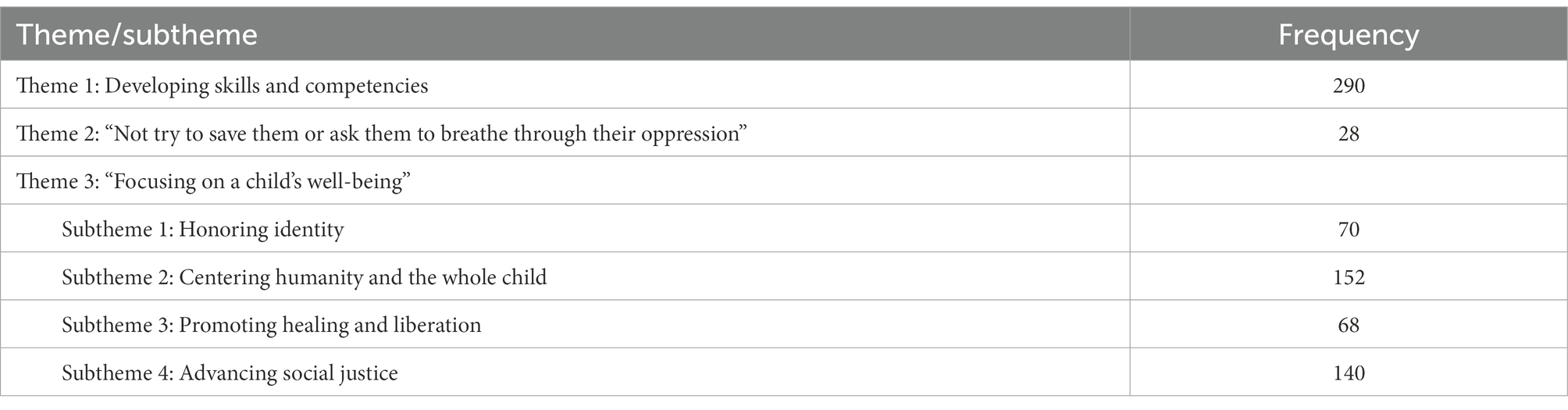

Three themes emerged related to how educators define SEL. Educators described SEL as “developing skills and competencies” (Theme 1), which aligns with existing SEL definitions. In addition, however, educators conceptualized SEL in ways that are not part of current SEL definitions. Some educators mentioned how SEL, as it is currently taught, can be harmful to BIPOC students and a superficial solution to deeper problems such as racism and other social injustices. Educators expressed that SEL should “not try to save them [students] or ask them to breathe through their oppression” (Theme 2). Educators also highlighted “focusing on a child’s well-being” as part of SEL (Theme 3). This theme encompassed several subthemes related to how SEL could be taught and implemented. Subthemes included honoring identity, centering humanity and the whole child, promoting healing and liberation, and advancing social justice. We present the frequency of codes for each theme in Appendix A.

Theme 1: “Developing skills and competencies”

Many educators in our study defined SEL as competency-based. Specifically, several educators mentioned that, for them, SEL was synonymous with the CASEL 5. In fact, CASEL was the only SEL framework educators referenced by name. One educator wrote that thinking of SEL “evokes [the] CASEL framework.” Educators found the competency-based definition of SEL helpful and were appreciative of it. They perceived that a framework such as CASEL’s outlines “[the] key skills and competencies that lead all human beings to know themselves,” and that SEL skills are important in “developing one’s understanding of oneself.”

Some educators did not refer to the CASEL 5 framework in its entirety but still defined SEL using one or more of the CASEL 5 competencies. For example, educators conceptualized SEL as skills that help them “identify, recognize, and control their emotions” (CASEL’s self-awareness competency), or described SEL as skills that “establish and maintain supportive relationships” (CASEL’s relationship skills competency), and “make responsible and caring decisions” (CASEL’s responsible decision-making competency). Educators also spoke about SEL’s pivotal role in helping students “develop skills and apply strategies for understanding and managing their emotions” (CASEL’s self-management competency). One educator described SEL as “learning how my awareness, emotional management, relationship skills, decision making, and social awareness impact the people I work with or teach.”

Theme 2: “Not try to save them or ask them to breathe through their oppression”

The second theme revealed that SEL, as it is currently practiced and taught in schools, can cause harm, especially to BIPOC students. Educators quoted scholar Dena Simmons (Madda, 2019) saying that SEL can be “white supremacy with a hug” and noted instances in which SEL programs involved “white teachers retraumatizing Black, Brown, and Queer youth.” One warned that a heavily-scripted SEL curriculum “would further white supremacy and institutional racism.” Another cautioned that educators may “unknowingly strip our students of their culture and language and identity in the name of SEL.” Similarly, one educator described their experience of “SEL practices which actually were meant to colonize, pacify, and/or make some sort of example of me, my background, my community, and my experiences.”

Educators also stressed “what SEL should not be” (emphasis added) to avoid inflicting further harm on students. One educator, in writing about their students, said that SEL should “not try to save them or ask them to breathe through their oppression.” Another expressed that SEL should be about “providing support and modeling SEL, not policing.” Relatedly, another educator highlighted that “SEL is not a way to control.” To avoid inflicting harm to students, one educator mentioned that SEL must be “culturally and historically responsive, …authentic, and leave no one behind to be managed by practices of white supremacy.”

Theme 3: “Focusing on a child’s well-being”

In contrast to educators who described SEL as a set of competencies and those who described SEL as harmful to BIPOC students, many educators focused on how SEL could be implemented to promote overall well-being. This theme comprises four subthemes, each addressing a different aspect of well-being: (1) honoring identity, (2) centering humanity and the whole child, (3) promoting healing and liberation, and (4) advancing social justice.

Subtheme 3.1: Honoring identity

Educators described how SEL could be used to honor and support students’ identities in co-created spaces. Educators discussed how this involved intentional action, both to create safe spaces and to facilitate youth exploration of their identities. In fact, educators defined SEL as “a dynamic process of learning about and sharing one’s identity,” and “…the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities.” One respondent wrote that “[SEL] means understanding who you are and how you show up in the world and understanding who those around you are and how they experience life because of their identities.”

Some educators described SEL as a means to connect identity with social justice, creating opportunities for students to learn “…about their identity and emotional lives along with each other for collective social justice” and to “show up in our full identities - learning about our identities, understanding our identities in the context of our community and society.” Additionally, educators stated that SEL skills must be taught “within a context that is applicable to the cultural, linguistic, racial, and gender identities of my students.” Educators stated that creating this context involved developing spaces and facilitating one’s identity exploration. One educator wrote:

SEL means ensuring that we make space for children and adults to explore their own identities, honor each other’s identities, learn how to listen to their bodies, understand how to regulate when they become dysregulated, learn how to build authentic relationships and partnerships to reach personal and collective goals for the good of all of us.

Others echoed this sentiment: “Social Emotional Learning means creating an environment where children are able to have important conversations related to their identity.” They noted that SEL includes creating “authentic opportunities for adults and youth to learn about each other, about oneself/one’s identities.”

In addition to providing spaces and opportunities, educators mentioned that “SEL means knowing students’ identities and who they aspire to be,” “helping students understand their identities and themselves,” “taking [students’] personal experiences and identities into account,” and “honoring students’ identities and lives before anything else.” One wrote that SEL, “celebrates [students’] identity while affirming their social and emotional selves.” Educators considered how “teachers can facilitate this learning when honoring a learner’s full identity and lived experience” and identified themselves as facilitators in ensuring “students are encouraged to explore all aspects of their identities.”

Subtheme 3.2: Centering humanity and the whole child

Educators also described getting to know students as whole people and honoring their humanity as key elements of SEL. When done well, educators reflected that SEL “means understanding students as individual people with complex emotions, past experiences, and lives outside of the classroom.” One educator wrote that SEL should be about “educating our children while taking into account the whole child and their life experiences that influence the way they think and learn and how they view the world and their place in it.” Another expressed that “SEL is the vehicle through which people learn to embrace their own humanity and the humanity of others.”

A component of this subtheme was “centering students’ humanity above their productivity.” Suggestions for this included addressing “… the needs of students and teachers beyond content and pedagogy to include learning and teaching for the whole person” and “giving youth the opportunity to simply exist in the K-12 space and be humans, not test scores.” One person simply stated that, “[SEL] is radical humanity wrapped in love and care.” Another educator summed up this concept by explaining SEL as “taking care of kids as people, not academics.”

Descriptions of humanizing practices extended beyond the individual to building community with others and, by doing so, building a better society overall. A respondent shared, “[SEL] means deeply connecting to students and giving them space to deeply connect with themselves and others. It means acknowledging humanity and creating space to build community.” Others echoed this sentiment, describing key elements of SEL as “recognizing and supporting the humanity of individuals and the community you build together in a learning space.” Some educators described how SEL could “help individuals learn how they process and interpret emotions in order to learn how they can better engage with their community and society,” thereby “contribut[ing] to safe, healthy, and just communities.”

Subtheme 3.3: Promoting healing and liberation

Educators described promoting healing and liberation as facets of SEL. Some described “SEL [as] a way of healing” and how SEL involved “making the classroom a place of safety and healing for all students.” One respondent reflected on “the equal need for addressing trauma and healing through culturally rich spaces that are welcoming and responsive.” Some educators also regarded SEL as a way to equip students with skills that would promote well-being later in life. Related descriptions of SEL included, “learning how to heal and strengthen our hearts and minds” and “work grounded in healing and justice to support the well-being of our students and families.” One educator reported that SEL could “hopefully equip students to disrupt the causes of stress, anxiety, and trauma.” Another succinctly wrote, “SEL is proactive mental health care.”

Moreover, to the educators, not only was healing considered an important outcome of SEL, it was also regarded as a mechanism for liberation. Many educators spoke about healing and liberation as parallel goals or about healing as a step toward liberation. This was present in responses such as, “…I would define SEL as collective and community wellness, healing, and liberation” and “[SEL] means healing, collaboration, collective care, and freedom.” One person wrote that SEL means “creating healing, dignifying, liberating, and transformative spaces.” Another shared that SEL was an opportunity to “heal together and work towards our shared liberation.”

Subtheme 3.4: Advancing social justice

Tying into the previous subthemes of humanizing and healing, educators identified dismantling inequitable systems as an aspirational component of SEL that promotes liberation. For instance, one educator said “[SEL] means to develop self-awareness and emotional intelligence to interrogate systems of oppression and work towards individual and collective liberation.” Another described SEL as “educating the whole child in a way that names and confronts oppressive lies while helping students build their own, liberated, proud sense of self in the world.” To one educator, SEL “…means being able to feel deeply, then using those feelings to emancipate you and your community.”

Educators communicated that SEL was a tool to “dismantle inequitable narratives in schools and society” and to “advocate/take part in breaking down systems that dehumanize everyone.” Educators believed that “SEL advances educational equity” through “help[ing] address various forms of inequity.” Some stated that SEL could be used “to recognize and confront injustice and inequity,” “address historic imbalances in power,” and “reduce suffering and create a more just and equitable world.” Other educators regarded SEL as “a relationship-driven approach and a social justice orientation” including “things like self-awareness, communication, social justice.” Specifically, educators stated that in order for SEL to be implemented well, programs need to address social and racial justice. For example, one educator stated, “SEL, when done effectively, addresses social and racial injustices with the goal of producing healing and solution-based learning experiences,” while another said, “if done well, SEL creates an environment where all can feel seen and heard.” Some mentioned justice more broadly in their definitions, reflecting that “SEL includes justice…and reflection” and that “SEL are the skills we need to be justice-oriented change makers.” One educator considered SEL to include “recognizing injustices and teaching about standing up for justice and many different ways to take action;” another identified “learning how to promote and advocate effectively for justice of all peoples” as a key component of SEL.

For several educators, SEL meant creating spaces with students that emphasize learning and genuine dialogue on social injustices while maintaining students’ social and emotional safety. Educators brought up their roles in creating brave spaces through SEL. One person, referring to their students, said, “it’s my role as the adult to help facilitate and support them in a way that supports inclusivity while disrupting harm.” Others said that their jobs were, “creating a teaching space in which students are encouraged to explore all aspects of their identities and address all of the ‘isms’ including, but not limited to, racism and white supremacy” and “making sure students feel safe and there is a racial and socio-economic lens to equitably approach emotional support for students.” Creating these spaces involved “being transparent and the equal need for addressing trauma and healing through culturally rich spaces that are welcoming and responsive.” Such spaces enabled students “to learn without fear of being discriminated against for being your true authentic self” and to “be seen, heard, and understood in an educational environment built on connection with a commitment to justice.”

Educators also spoke about the need for SEL to be culturally affirming and antiracist. Educators’ definitions were aspirational. One educator concluded, “…we need antiracist SEL.” Another wrote that SEL “should affirm emotions and responses to emotions that are aligned with students’ cultures- or be understood from a cultural lens (not white culture).” Others described SEL as “the foundation for racial equity” and, “culturally responsive pedagogy, antiracism, equity, inclusion, belonging, and wellness.” Several educators wrote that SEL “…includes being honest about racism, bias, and white supremacy and its role in perpetuating hurt.” Another participant, referring to SEL, said, “it is antiracist teaching that can be incorporated into every content area of the curriculum.” Concisely tying up these sentiments, one educator defined SEL as, “in a nutshell, trauma-informed and antiracist.”

Discussion

Our study demonstrated the power of listening to a community of educators and honoring their genius in shaping students’ educational experiences and fostering learning environments that honor, uplift, and support humanity while also creating educational content that centers students’ identities and confronts injustices and white supremacy. Educators are a largely untapped resource in shaping SEL programming and its implementation, research, and policy. As policymakers and education leaders aim to prepare young people for the world that they will inherit, it is critical to include educators in all aspects of the decision-making that happens too often without them.

When asked to define SEL, educators described SEL as a set of competencies using the historical understanding of SEL coined more than two decades ago by youth development professionals as part of the formation of CASEL. This definition of SEL is: “identifying and labeling feelings, expressing feelings, assessing the intensity of feelings, managing feelings, delaying gratification, controlling impulses, and reducing stress” (Consortium on the School-Based Promotion of Social Competence, 1994). This is the most used, known, and disseminated definition given CASEL’s leadership in the field (Graczyk et al., 2000; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2017). Therefore, we were not surprised that educators in this study defined SEL using CASEL’s competencies.

We found, however, that educators also perceive SEL to be more expansive than current competency-only models. Educators in our study identified limitations and potential harm that may be caused by current SEL approaches and emphasized that SEL is a praxis whose benefit to students is dependent on how it is implemented. At face value, educators acknowledged that current SEL definitions and practices are at risk of perpetuating a “one size fits all” approach that emphasizes neutrality and assumes that everyone’s emotions are perceived and welcome equally, often ignoring the impact of systemic oppression on those who have been consistently marginalized. Implementing SEL with a goal of neutrality teaches personal strategies for understanding and managing feelings without taking into account and honoring the unique and diverse cultures, backgrounds, and lived experiences across all students and especially of BIPOC and other students forced to the margins (Simmons, 2020a).

Our study participants described honoring identity as a prominent aspect of effective SEL to promote justice and student well-being. An SEL praxis that intentionally honors student identity aligns with literature and theory on culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP; Ladson-Billings, 1995). CRP is an approach infused into all aspects of teaching and learning to promote equity and dismantle harmful practices and narratives by meeting students where they are instead of imposing values and practices from the dominant culture on people who cannot relate to them (Simmons, 2019a) and who are not reflected by them. Though rarely discussed in the United States, most educational curricula, including SEL curricula, are based on a dominant white, Western, and individualistic culture (Picower, 2009; Kasun and Saavedra, 2016). Current SEL programs and frameworks, including CASEL, center whiteness in their glorification of productivity and employability (Committee for Children, 2016), which aligns with capitalism (Simmons, 2020b). This emphasis can result in teachers imposing a particular set of narrow values and beliefs on students about behavior, emotion management and expression, and conflict resolution.

Cultural differences in emotion regulation (Matsumoto et al., 2008) and emotion display rules (Safdar et al., 2009) between teachers and students can result in misunderstanding and miscommunication in addition to disproportionate rates of exclusionary discipline practices, academic failure, and school disengagement for youth who are institutionally marginalized (Gregory et al., 2010; Brown-Jeffy and Cooper, 2011; Skiba et al., 2011). In addition, research has found that when educators misidentify their students’ emotions, it leads to student disengagement (Hargreaves, 1998; Hargreaves, 2000). These are only a few examples of why SEL cannot ignore students’ cultural, social, and political realities or be race-neutral, as neutrality often translates into centering whiteness and white comfort. Rather, it is crucial for educators to recognize and confront their implicit biases, humanize their students by getting to know them as whole people, and engage in culturally affirming SEL practices. SEL must actively and deliberately be culturally responsive, antiracist, and anti-oppressive (Simmons, 2020b). Educators in this study recognized a current gap in SEL programming which is a lack of attention to the diverse values and beliefs across individuals, groups, and cultures, affirming the need for CRP to guide and inform how we approach, implement, and “live” SEL moving forward. Participants in this study clarified that SEL cannot be practiced as skills alone and must center humanity, healing and liberation, and social justice, thus honoring students’ identities, realities, and lives in our ever-complex world.

When students do not experience any reflection of themselves in curricula, this can result in the trauma of erasure (Simmons, 2020a). Traditionally, SEL programming has not been intentionally culturally responsive, contributing to this erasure, which can lead to student disengagement and other adverse social, emotional, and academic outcomes (Bottiani et al., 2020). For example, a white, straight, cisgender, female teacher, who lacks self-awareness about her positionality and who has no exposure to culturally responsive pedagogy, may teach SEL through her worldview without consideration of how her lens does not reflect the reality of her students, especially those who have been systemically marginalized. She might include content relevant to her lived experiences but fail to add content that is relevant to her students’ lives, contributing to students’ feeling like they do not belong. She might even teach a particular skill that is inconsistent with students’ cultures such as demanding eye contact as a sign of respect when, in many Asian, Latinx, and African cultures, eye contact could be regarded as a sign of defiance and disrespect (Wages, 2015). That is, culture plays a role in how SEL competencies are developed and expressed (Hecht and Shin, 2015) and thus needs specific attention. In contrast, that same teacher can build awareness of how to implement SEL in ways that honors students for their identities and experiences rather than restricting them to a narrow view of what is “acceptable” or “appropriate.” She would welcome and teach multiple expressions of respect (and other emotions) instead of ostracizing students, who lower and avert their eyes as a sign of respect. Through practicing self-reflection and self-awareness, developing cultural humility, and gaining exposure to culturally responsive pedagogy, educators can expand their knowledge of how to use SEL to humanize and honor all students.

Educators in our study regarded humanizing others as an important piece of SEL implementation. In particular, many described SEL in its ideal form as a praxis that can be responsive to student and community needs, facilitate healing, and center humanity and racial and social justice. In fact, humanization is a process that educators and scholars of education have identified as a key component of education. Philosopher and educator Paulo Freire, whose practices aimed to liberate students, wrote that humanizing students promotes freedom and justice (Freire, 1970). Similarly, scholar and writer bell hooks deemed education as a practice of freedom, where students transgress against racial, sexual, and class boundaries to achieve freedom (Hooks, 1994). Respecting the humanity of others promotes educational, social, and cultural justice and can benefit students’ social and emotional health and well-being (Paris and Winn 2013). Humanizing others as part of an SEL practice allows educators to get to know students as complete beings with cultures, languages, and histories, including the intersecting systems of privilege or oppression that may shape their lives. By centering humanity in their instruction, educators can place people first over productivity and academic achievement. When school communities feel valued through humanization, they can engage more respectfully and harmoniously with each other and have the necessary room and safety for collective healing and liberation.

In addition to identifying the need for SEL to be conceptualized as a humanizing praxis, educators in our study identified healing as a crucial outcome of SEL and a way to promote liberation. For us, liberation is defined as living, learning, and thriving in the comfort of one’s own skin (LiberatED SEL, 2022). This could happen through fostering belonging by inviting, welcoming, and centering students’ lived experiences in instruction and interactions and incorporating healing opportunities in classrooms by ensuring all aspects of students are invited and welcomed, for example. We define healing as a regenerative process with the goal of restoring collective and individual wellbeing at the emotional, spiritual, social, psychic, and physical levels (Chavez-Diaz and Lee, 2015). The fact that nearly all educators who spoke of healing also spoke of liberation is meaningful and indicates the need for schools to be more liberating spaces.

Current SEL frameworks and practices focus more on “remaining neutral” than on building awareness, critical consciousness, and actions that address racialized stress and trauma among BIPOC students (Ginwright, 2015). For healing to happen, SEL practitioners, scholars, and educators must acknowledge and confront the racial harm and social injustice as a result of society’s oppressive policies and practices as well as their own individual and institutional practices. Likewise, there needs to be an intentional and explicit practice of healing too. One method of beginning the healing process in schools is through healing-centered engagement (Ginwright, 2018), a holistic approach to trauma that involves a focus on culture, identity, and collective healing. This approach is strengths-based and focuses on human possibility and potential. Healing-centered engagement identifies healing as a collective effort rather than an individual one, and it strives to address the systemic and pervasive root causes of trauma (Ginwright, 2018). This is needed now more than ever given the coronavirus pandemic and an increase in hate crimes (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2021). Another approach to healing is through storytelling which challenges the validity of accepted premises or myths held by majority groups, who are often in positions of power (Delgado and Stefancic, 2001). In a classroom, students and teachers can tell personal stories or write personal narratives about what life is like for them and invite others into their worlds as they feel comfortable sharing (Solorzano and Yosso, 2002).

Collectively, healing and working toward shared liberation means taking explicit actions to dismantle oppressive social forces (Ginwright, 2018). Healing work is political, as it involves shifting the blame for harm or well-being from the individual and onto systemic and historical inequities and injustices. Educators in this study noted the importance of creating spaces to identify and actively work toward dismantling oppressive social forces, teaching about social justice, equity, and antiracism, and using culturally-affirming practices as important steps towards liberation. Educators expressed a need for SEL that includes opportunities for promoting social justice and eradicating practices and policies that contribute to inequity. Their comments echoed what SEL scholar and co-author of this manuscript, Dena Simmons, has stated about the need for SEL to address our sociopolitical reality and combat racial and social injustice (Simmons, 2019b). It is our nation’s imperative to center social justice in our SEL programming, instruction, and practice so that it can live up to its full promise and facilitate connection across differences, truly reflecting the aspirational definitions of SEL that educators shared in their responses. Simply, SEL alone cannot solve racism or other forms of oppression without deliberately confronting and combating injustice (Simmons, 2020a).

A critical finding from our study was that educators highlighted how SEL, as it is currently conceptualized and thus how it may be implemented, can be weaponized against BIPOC students. This perpetuates racial harm and has been called out in recent literature (e.g., DeMartino et al., 2022). We observed this in educators’ responses about how SEL can be presented as a savior for BIPOC students as well as a way to manage and control student behavior. SEL practitioners and scholars have warned about exactly what we found in our study in their descriptions of SEL as a tool that reinforces compliance and control (Simmons, 2019c; Kaler-Jones, 2020) and a way to save BIPOC students (Simmons, 2017). Regarding SEL as the savior of BIPOC students implicitly creates a power imbalance between the “savior” and those in need of saving, disempowering BIPOC youth and perpetuating racial hierarchy with white people atop. This also positions BIPOC students as a problem to solve (Simmons, 2017). When SEL is presented as a behavioral intervention for BIPOC students, it sends the message that BIPOC students behave in unacceptable ways and need to be corrected and taught to conform and comply. Thus, it is imperative that the SEL field be mindful of the social, political, and historical context in which SEL is implemented (Simmons, 2019d). Failing to do so can further marginalize and oppress BIPOC students.

Moreover, it is important to note that the education field continues to be a profession that is predominantly white while our student body is primarily BIPOC (U.S. Department of Education, 2016; Riser-Kositsky, 2019). This racial and cultural mismatch between teachers and students can have deleterious academic, behavioral, social, and emotional outcomes, especially if teachers regard SEL as a behavioral intervention and savior. On top of the disproportionate disciplinary practices that contribute to the school-to-prison nexus for BIPOC students (U.S. Department of Education, 2018), the hyper-surveillance that BIPOC students experience at school contributes to trauma and negative social and emotional health outcomes (Camangian and Cariaga, 2021), thus diminishing the promise of SEL.

Our education system must evolve to meet the unique needs of educators, students, and their families given our current sociopolitical context, shifting demographics, and technological advances. The same is true for SEL. How SEL is defined, implemented, and researched must change to meet the pressing needs of our country. Through the educators in the study, we have the beginning of a redefinition of SEL that centers identity, humanity, healing, and justice. Currently, these areas are not explicit components of most SEL definitions, models, and programs even though studies suggest that attention to them can significantly contribute to improving the quality of SEL programs and policies at schools (e.g., Davis et al., 2022; Forman et al., 2022). This study is a critical step toward understanding, redefining, and transforming SEL through the voices and perspectives of educators with the aim of SEL implementation that ensures all students can live, learn, and thrive at school in the comfort of their own skin.

As currently written, the CASEL 5 is limited, as it suggests that SEL is a set of skills that are the same for everyone and can be taught in the same way to all students. It does not yet address the shifting demographics of our nation’s more racially and ethnically diverse student body (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). Yet, years of research suggest that students learn differently and benefit from both differentiated instruction (Tomlinson and McTighe, 2006) as well as culturally responsive pedagogy (Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 2021), that meets students’ individual learning needs. Supporting the optimal social, emotional, and academic development of youth requires that educators and educational leaders effectively apply SEL in ways that are meaningful, relevant, and affirming to the identities and lived experiences of youth. This work requires flexibility, adaptability, representation, attention to racial and social justice, and creativity (e.g., Tan et al., 2021).

CASEL’s response to calls for equity-responsive SEL has been to add “equity elaborations” to each competency as part of their enhanced SEL called “transformative SEL” (Jagers et al., 2019). Though a potential step in the right direction, these calibrations are add-ons to existing competencies, which contrast with how educators in our study described honoring identity, humanizing students, promoting healing and liberation, and advancing social justice as foundational components of SEL praxis, not as afterthoughts. Given its institutional power, CASEL is well-positioned to shift SEL from a competency framework to a model that prioritizes a human-centered, culturally affirming, and historically responsive praxis. Doing so could help ensure that all students–and especially those who have been historically and systematically marginalized–obtain the benefits of SEL, feel a sense of belonging at school, and can flourish in their full personhood, thereby improving their mental health and well-being.

Educators’ more expansive definitions of SEL in this study align with models of culturally responsive pedagogy, healing-centered education, and social and racial justice. Our findings demonstrate that SEL is not “value-neutral and independent from practices, histories and the contexts of its production” (Stetsenko, 2014, p. 181). SEL programming and professional development must evolve to ensure instruction, policies, and practices are culturally and contextually relevant and honor student experiences. Educators play a critical role in SEL’s necessary evolution. With the rise in attention toward promoting mental health in schools resulting from the pandemic and civil unrest comes an opportunity to promote a holistic, culturally-affirming, and liberatory approach to SEL that supports all students. Schools are turning to SEL as a solution to the numerous challenges students are facing, but our education system must guarantee that SEL is not harmful or oppressive despite good intentions. Now is the time to reassess and redefine SEL and to move away from SEL solely as a set of competencies that may not be reflective or useful for all (and may, in fact, cause harm to some), and toward a future in which SEL honors identity for all, centers humanity and the whole child, promotes healing and liberation, and advances social and racial justice.

Limitations

As with all research, our study has limitations. For one, our question “What does SEL mean to you?” was broad. We were not always able to differentiate whether open-ended responses were reflective of an educator’s current SEL practices or their aspirations for SEL unless explicitly stated. In future studies, we would clarify our question and explore both educator aspirations and current practices to measure whether there are discrepancies between the two. Additionally, the majority of educator responses were short; many consisted of only one or a few sentences. Nonetheless, these responses offered an important glimpse into educator conceptualizations of SEL. Future studies would benefit from approaches that promote greater depth of response and allow for follow-up probes such as interviews or focus groups. Future studies would also benefit from exploring how educators’ definitions of SEL relate to the program implementation of SEL and student experiences and outcomes.

Another limitation is that our sample comprised educators who self-selected to attend an event focused on the intersection of SEL, racial justice, and healing in educational settings. Our participants most likely possessed a more advanced understanding of or a greater interest in the intersection of SEL, racial justice, and healing than other educators who did not register for such an event. It is likely that respondents were primed to think about SEL, racial justice, and healing based on the focus of the event and given their interest in attending. Though we believe that the educators in this study shared important, illuminating, and relevant information for the exploration of our topics of interest, we acknowledge that they may not be representative of the larger educator population. Future studies could use a random sample of educators to obtain more generalizable results.

Implications and future directions

Our study has practice, policy, and research implications for SEL. For one, our study highlighted identity affirmation, humanity, healing and liberation, and social justice as necessary and central components of SEL. Given our findings, the education system as well as education researchers and curriculum developers must employ practices that create opportunities to honor students’ identities, humanize students, and facilitate healing, liberation, and justice. To be effective, these efforts must be paired with access to curricula and other relevant resources, opportunities to engage in professional development and coaching for educators and school leaders, and policies supportive of these practices. After nearly two and a half years in a pandemic with corresponding movements to ban antiracist efforts, culturally relevant and responsive practices in schools, and SEL, there is an urgent need for policymakers to confront these challenges by standing firmly for collective humanity and healing and rejecting calls to ban anything (e.g., books and curricula) that has to do with SEL, race, difference, or identity. Similarly, leaders in the SEL field could more strongly advocate for culturally affirming SEL grounded in racial and social justice, healing, and liberation instead of advocating for neutrality, which further marginalizes youth who are already disenfranchised. Our education system must create opportunities to include the BIPOC student community and other youth who are institutionally marginalized when making instructional decisions and creating academic content related to SEL and beyond so that student learning is grounded meaningfully in their own lives. Our study clarified the importance of doing so.

Future research could expand upon findings from this study by probing between-person differences in conceptualizations of SEL to identify response patterns using qualitative (e.g., open-ended survey items or interviews with educators), quantitative (e.g., latent class analysis), or mixed-method approaches (e.g., a convergent parallel design exploring how educators’ responses to open-ended prompts align with responses to close-ended survey items, and if and how these represent categories of people or types of responses). Our team is already beginning to conduct this research. Additionally, because students should have a central role in their own learning and are generally more engaged when their instruction centers their lives (Byrd, 2016), an important future research direction is to gain insight directly from students about how they conceptualize and experience SEL as well as how they want to engage in SEL at school. In particular, we will continue to adopt a community-based research design for future studies. Rooted in reciprocal partnerships, community-based research design seeks to democratize knowledge, improve practices, and bring about social change by recognizing and valuing the unique strengths and perspectives of all members involved in the research process (Atalay, 2010; Tremblay et al., 2018). This approach provides a framework for using culturally responsive, constructivist, and interpretivist strategies to address injustice, and ensures that we center the voices of educators and uplift their genius so that they have a key role in shaping their profession.

Conclusion

Our current moment is marked by exacerbated mental health challenges and trauma as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as heightened racial tension and racism. While SEL has been one way our nation’s schools have selected to address the resulting mental health challenges that many students and communities are experiencing from enduring a global pandemic, it will not facilitate the atonement needed in many schools and communities without centering individual and collective healing, racial and social justice, and a commitment to dismantling white supremacy in education and beyond.

Findings from this study show that SEL has the potential to inflict harm on students if it is not intentionally implemented through a culturally responsive and racially just lens. One of the primary findings of our study was the importance of centering humanity and healing in education. While the backlash against racial and social justice initiatives in education is evidence of the necessity of centering humanity in our educational instruction and practices, research demonstrates racial justice education can be a helpful tool to combat the current divisiveness in the U.S.’ education system (Williams, 2021; Scientific American, 2022). SEL has tremendous potential to help us come together, understand one another, build relationships, manage conflict, and elicit social change if infused with an ideology and practice of humanization, healing, social justice, and identity affirmation, and if approached with the goal of collective liberation. When teaching, researching, or creating policies around SEL, we must pay attention to the sociopolitical and racial contexts and work to eradicate the inequities that students experience and navigate daily inside and outside of school (Madda, 2019). In sum, our nation’s schools must do the deliberate work to become healing and liberating spaces so that all students have the privilege of experiencing the freedom to be who they are without repercussions, punishment, or fear of harm.

This study provides a hopeful blueprint for educational practices and policies that include educator voices and lean on their resources and experiences as we dream of and cultivate liberatory educational experiences and systems for the future. The learning gained from this study will enable those who support educators and students to adapt and adjust SEL to meet their needs more responsively, effectively, and authentically. Overall, this study lays a foundation for improving SEL implementation so that current and future programs can meet the needs of all students, especially those who have been most disenfranchised. By tapping into educators’ experiences and knowledge, we honor them as co-creators of a future vision for a more humanizing and healing approach to SEL—one that centers collective liberation and examines and disrupts oppression, bias, and bigotry—so that educators and students are prepared to engage in the social change required for achieving our nation’s values of equity and justice for all.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset belongs to LiberatED. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ML, cmVzZWFyY2hAbGliZXJhdGVkc2VsLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SO and ML analyzed and interpreted all data. SO, ML, MM, DS, and ST wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jey Blodgett, Heidi Forbes, and Madeline Ruo for their help with the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abolitionist Teaching Network. (2022). Available at: http://abolitionistteachingnetwork.org/ (Accessed September 9, 2022).

Alinsky, S. (1971). Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals. New York, NY: Random House.

ASCD. (1997). Social and emotional learning. Available at: https://www.ascd.org/el/social-and-emotional-learning (Accessed September 9, 2022).

Atalay, S. (2010). “We don’t talk about Catalhoyuk, we live it”: sustainable archeological practice through community-based participatory research. Archeol. Contemp. Soc. 42, 418–429. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2010.497394

Barret, P. (2022). Social unrest is rising, adding to risks for global economy. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/05/20/social-unrest-is-rising-adding-to-risks-for-global-economy (Accessed November 23, 2022).

Bauer, M. W., and Gaskell, G. (2000). “Classical content analysis: a review” in Qualitative Researching With Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 131–151.

Birks, M., Chapman, Y., and Francis, K. (2008). Memoing in qualitative research. J. Res. Nurs. 13, 68–75. doi: 10.1177/1744987107081254

Boncu, A., Costea, I., and Minulescu, M. (2017). A meta-analytic study investigating the efficiency of socio-emotional learning programs on the development of children and adolescents. Rom. J. Psychol. 19, 35–41. doi: 10.24913/rjap.19.2.02

Bottiani, J. H., McDaniel, H. L., Henderson, L., Castillo, J. E., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2020). Buffering effects of racial discrimination on school engagement: the role of culturally responsive teachers and caring school police. J. Sch. Health 90, 1019–1029. doi: 10.1111/josh.12967

Boyd, M. R. (2020). “Community-based research: a grass-roots and social justice orientation to inquiry” in The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. ed. P. Leavy (Oxford: Oxford Academic)

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks, J. S., and Theoharis, G. (2018). Whiteucation: Privilege, Power, and Prejudice in School and Society. London: Routledge.

Brown-Jeffy, S., and Cooper, J. E. (2011). Toward a conceptual framework of culturally relevant pedagogy: an overview of the conceptual and theoretical literature. Teach. Educ. Q. 38, 65–84.

Byrd, C. M. (2016). Does culturally relevant teaching work? An examination from student perspectives. SAGE Open 6:215824401666074. doi: 10.1177/2158244016660744

Camangian, P., and Cariaga, S. (2021). Social and emotional learning is hegemonic miseducation: students deserve humanization instead. Race Ethn. Educ. 25, 901–921. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2020.1798374

Chavez-Diaz, M., and Lee, N. (2015). A Conceptual Mapping of Healing Centered Youth Organizing: Building a Case for Healing Justice. Oakland, CA: Urban Peace Movement.

Childcare Technical Assistance Network (2021). Resource guide for developing integrated strategies to support the social and emotional wellness of children. Available at: https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/resource/resource-guide-developing-integrated-strategies-support-social-and-emotional-wellness

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2013a). CASEL Schoolkit: A Guide for Implementing Schoolwide Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. Chicago, IL: CASEL.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2013b). 2013 CASEL Guide: Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs—Preschool and Elementary School Edition. Chicago, IL: CASEL.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2020a). An initial guide to leveraging the power of social and emotional learning as you prepare to reopen and renew your school community. Available at: https://s3.us-east2.amazonaws.com/ohiomea/covid/1589978073.pdf

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2020b). Reunite, renew, and thrive: Social and emotional learning (SEL) roadmap for reopening school. Available at: https://casel.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/RefocusOnSELRoadmapCASEL1.pdf

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2021). Collaborating district initiative. Available at: https://casel.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/RefocusOnSELRoadmapCASEL1.pdf

Committee for Children. (2016). Why social and emotional learning and employability skills should be prioritized in education. Available at: https://www.cfchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/policy-advocacy/sel-employability-brief.pdf

Consortium on the School-Based Promotion of Social Competence (1994). “The school-based promotion of social competence: theory, research, practice, and policy” in Stress, Risk, and Resilience in Children and Adolescents: Processes, Mechanisms, and Interventions. eds. R. J. Haggerty, L. R. Sherrod, N. Garmezy, and M. Rutter (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 268–316.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Curtis, D. S., Washburn, T., Lee, H., Smith, K. R., Kim, J., Martz, C. D., et al. (2021). Highly public anti-black violence is associated with poor mental health days for black Americans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118:e2019624118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019624118

Davis, S. J., Lettis, M. B., Mahfouz, J., and Vaughn, M. (2022). Deconstructing racist structures in K-12 education through SEL starts with the principal. Theory Pract. 61, 145–155. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2022.2036061

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press.

DeMartino, L., Fetman, L., Tucker-White, D., and Brown, A. (2022). From freedom dreams to realities: adopting transformative abolitionist social emotional learning (TASEL) in schools. Theory Pract. 61, 156–167. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2022.2036062

Dubois, A., and Gadde, L. E. (2002). Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. J. Bus. Res. 55, 553–560. doi: 10.1016/s0148-2963(00)00195-8

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Fair Health. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on pediatric mental health: a study of private healthcare claims. Available at: https://bit.ly/3t3b95F (Accessed September 9, 2022).

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2021). FBI Released 2020 Hate Crime Statistics. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Forman, S. R., Foster, J. L., and Rigby, J. G. (2022). School leaders’ use of social-emotional learning to disrupt whiteness. Educ. Adm. Q. 58, 351–385. doi: 10.1177/0013161X211053609

Frye, K. E., Boss, D. L., Anthony, C. J., Du, H., and Xing, W. (2022). Content analysis of the CASEL framework using K–12 state SEL standards. Sch. Psychol. Rev., 1–15. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2022.2030193

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Ginwright, S. (2018). The future of healing: Shifting from trauma informed care to healing centered engagement. Medium. Available at: https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c

Graczyk, P., Greenberg, M., Elias, M., and Zins, J. (2000). The role of the collaborative to advance social and emotional learning (CASEL) in supporting the implementation of quality school-based prevention programs. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 11, 3–6. doi: 10.1207/s1532768xjepc1101_2

Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., and Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap. Educ. Res. 39, 59–68. doi: 10.3102/0013189x09357621

Grové, C., and Laletas, S. (2020). “Promoting student wellbeing and mental health through social and emotional learning” in Inclusive Education for the 21st Century: Theory, Policy and Practice. ed. L. Graham (Oxfordshire: Taylor and Francis), 317–335.

Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 14, 835–854. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 811–826. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7

Hecht, M. L., and Shin, Y. (2015). “Culture and social and emotional competencies” in Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. eds. J. Durlak, C. Domitrovich, R. Weissberg, and T. Gullotta (New York, NY: Guilford), 50–64.

Hunter, L. J., DiPerna, J. C., Hart, S. C., Neugebauer, S., and Lei, P. (2022). Examining teacher approaches to implementation of a classwide SEL program. Sch. Psychol. Forum 37, 285–297. doi: 10.1037/spq0000502

Israel, B., Eng, E., Schulz, A., and Parker, E. (2005). Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey–Bass.

Israel, B., Schulz, A., Parker, E., and Becker, A. (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Am. Rev. Public Health 19, 173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., and Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educ. Psychol. 54, 162–184. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

Jones, S. E., Ethier, K. A., Hertz, M., DeGue, S., Le, V. D., Thornton, J., et al. (2022). Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic - adolescent behaviors and experiences survey. United States, January-June 2021. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep. Suppl. 71, 16–21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3

Kaler-Jones, C. (2020). When SEL is used as another form of policing. Communities for Just Schools Fund. Available at: https://medium.com/@justschools/when-sel-is-used-as-another-form-of-policing-fa53cf85dce4

Kasun, G. S., and Saavedra, C. M. (2016). Disrupting ELL teacher candidates’ identities: indigenizing teacher education in one study abroad program. TESOL Q. 50, 684–707. doi: 10.1002/tesq.319

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32, 465–491. doi: 10.3102/00028312032003465

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Asking a Different Question. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lawson, G. M., McKenzie, M. E., Becker, K. D., Selby, L., and Hoover, S. A. (2019). The core components of evidence-based social emotional learning programs. Prev. Sci. 20, 457–467. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0953-y

Leonard, A. M., and Woodland, R. H. (2022). Anti-racism is not an initiative: how professional learning communities may advance equity and social-emotional learning in schools. Theory Pract. 61, 212–223. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2022.2036058

LiberatED SEL. (2022). Available at: https://linktr.ee/liberated_sel (Accessed September 9, 2022).

Madda, M. J. (2019). Dena Simmons: Without Context, Social-emotional Learning Can Backfire. Burlingame, CA: EdSurge.

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., and Nakagawa, S. (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94, 925–937. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.925

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miller, E. (2021). For Some Black Students, Remote Learning has Offered a Chance to Thrive. Washington, DC: NPR.

Miller, D. W., Zyromski, B., and Brown, M. J. (2022). Reimagining SEL as a tool to deconstruct racist educational systems. Theory Pract. 61, 141–144. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2022.2043708

Modan, N. (2020). Pandemic-induced trauma, stress leading to “uptick” in SEL need. K-12 dive. Available at: https://www.k12dive.com/news/pandemic-induced-trauma-stress-leading-to-uptick-in-sel-need/576710/

Mott (2021). Mott poll report: How the pandemic has impacted teen mental health. Available at: https://mottpoll.org/sites/default/files/documents/031521_MentalHealth.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Racial/ethnic enrollment in public schools. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cge

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., and Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research. Acad. Med. 89, 1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000000388

O’Connor, C., and Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 19:160940691989922. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220

OECD. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Equity and Inclusion: Supporting Vulnerable Students During School Closures and School Re-openings. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Paris, D., and Winn, M. T. (2013). Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Inquiry With Youth and Communities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Peterson, T. H. (2009). Engaged scholarship: reflections and research on the pedagogy of social change. Teach. High. Educ. 14, 541–552. doi: 10.1080/13562510903186741

Picower, B. (2009). The unexamined whiteness of teaching: how White teachers maintain and enact dominant racial ideologies. Race Ethn. Educ. 12, 197–215. doi: 10.1080/13613320902995475

Reliefweb. (2020). COVID-19: Most marginalized children will bear the brunt of unprecedented school closures around the world. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/covid-19-most-marginalised-children-will-bear-brunt-unprecedented-school-closures

Riser-Kositsky, M. (2019). Education statistics: facts about American schools. Education Week. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/education-statistics-facts-about-american-schools/2019/01

Rutgers Center for Effective School Practices (2022). Social-emotional learning in response to COVID-19. Available at: https://cesp.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/RU.CESP_Research.Brief_Covid.SEL.RTI.pdf

Safdar, S., Friedlmeier, W., Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., Kwantes, C. T., Kakai, H., et al. (2009). Variations of emotional display rules within and across cultures: a comparison between Canada, USA, and Japan. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement. 41, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0014387

Sanders, B. (2020). The power of social and emotional learning: why SEL is more important than ever. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesnonprofitcouncil/2020/12/07/the-power-of-social-and-emotional-learning-why-sel-is-more-important-than-ever/?sh=6636e96a7a29

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Kitil, M. J., and Hanson-Peterson, J. (2017). To Reach the Students, Teach the Teachers: A National Scan of Teacher Preparation and Social and Emotional Learning. A Report Prepared for CASEL. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. Chicago, IL: CASEL.