- Endicott College, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a focus on reforming teaching, learning models and strategies, particularly in online teaching and learning tools. Based on the social cognitive career theory and the constructivist learning theory, the purpose of this study was to understand and explore the learning preference and experience of students’ online courses during the COVID-19 pandemic and the management after the COVID-19 pandemic from the students’ perspective. The study was guided by the following two research questions: (1) After the COVID-19 pandemic, why do the students want to continue their foreign language courses via an online platform and model? What are the motivations and reasons? (2) How would the students describe their experience of a foreign language course via an online platform and model? With the general inductive approach and sharing from 80 participants, the participants indicated that flexibilities and convenience, same outcomes and learning rigorousness, and interactive experiences with classmates from different parts of the world were the three main key points. The results of this study may provide recommendations to university leaders, department heads, and teachers to reform and upgrade their online teaching curriculum and course delivery options after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Background

Due to the development of technologically assisted teaching and learning tools, flexible enrolment management, and delivery options, many traditional-age students and non-traditional students may enjoy university education. A recent report by the State of Oregon Employment Department (Wallis, 2020) predicted that from 2015 to 2026, enrolment of non-traditional students (25 years and older) could increase by 8.2% or 664,000, while the youth population (from 14 to 25 years old) could increase by 16.8% or 1,991,000. By 2026, the non-traditional student population could comprise nearly 40% of the university student population, while just over 60% will be youths.

Distance learning is one of the current international education trends in university environments, in both credit and non-credit courses. Many universities have established a proportion of courses and academic programs for students who cannot attend the traditional face-to-face courses that have been the norm over the past decades. Recent statistics from the National Centre for Education Statistics (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020) indicate that 19,637,499 students enrolled in any undergraduate and postgraduate educational institutions in 2019. In total, 12,323,876 (about 62.8%) students studied as on-campus students without any distance learning options. Also, 7,313,623 (about 37.2%) students enrolled in any online courses at degree-granted postsecondary institutions in the United States. Of these students (37.2%), 3,863,498 students took at least one, but not all, of students; courses are distance education courses, 3,450,125 students took distance learning courses exclusively. These education trends may continue due to the flexibility and convenience of online courses, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose of the study

First, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a focus on reforming teaching as well as learning models and strategies, particularly in online teaching and learning tools. Recent statistics (Wallis, 2020) indicate that many university students have experienced at least one online course due to the COVID-19 pandemic and government social distancing recommendations. Although many courses will eventually return to traditional face-to-face teaching models and strategies to increase learning and on-campus experience, online teaching and learning have become options for students to complete their courses online, particularly in foreign language courses.

Second, many foreign language courses and instructions tend to focus on face-to-face and physical interactions with students, teachers, and peers in the classroom environment. Although a few literature courses may be delivered online, many language-based courses are physically delivered. Therefore, it is important to understand the voices and comments of foreign language students to upgrade and polish the online-based foreign language courses during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The result of this study will provide recommendations to school leaders, department heads, curriculum designers, and policymakers about the developments of online teaching and learning courses, particularly for foreign language learners at the college and university level.

Based on the social cognitive career theory and the constructivist learning theory, this study aimed to understand and explore the learning preference and experience of students’ online courses during the COVID-19 pandemic and the management after the COVID-19 pandemic from the students’ perspective. The study was guided by the following two research questions:

(1) After the COVID-19 pandemic, why do the students want to continue their foreign language courses via an online platform and model? What are the motivations and reasons?

(2) How would the students describe their experience of a foreign language course via an online platform and model?

Theoretical frameworks and literature review

The researcher employed two theoretical frameworks – the social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996) and the constructivist learning theory (Bruner, 1973, 1996) to examine online teaching and learning issues during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The social cognitive career theory indicates that individuals’ behaviors and motivations can be impacted by both internal and external factors, which can direct the goals and achievements of individuals and groups. For details, please refer to the following section. Therefore, based on the application of the social cognitive career theory, the employment of the theory is useful because the theory may seek the motivation and decision-making processes of the individuals and groups.

Second, the constructivist learning theory (Bruner, 1973, 1996) is useful for investigating this study. In fact, previous experience, learning style, and understanding could significantly impact individuals’ and groups’ understanding, learning styles, language learning acquisition, and expectations from the classes. In this case, the researcher wanted to understand how the online learning platform and learning style could impact the experiences and expectations of the participants. Therefore, the employment of the constructivist learning theory would be appropriate.

Social cognitive career theory

The social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996) advocates that individuals’ self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and goals build decision-making and sense-making processes. Self-efficacy is an individual’s personal understanding and belief of their capacity and ability to exercise targeted behavior and a series of actions. Outcome expectation refers to the targeted and potential consequences of their decisions. Personal goals refer to intentions during the procedure and the potential aftermath of decisions. Single or multiple factors based on the social cognitive career theory may influence an individual’s decision-making and sense-making process.

Motivation and reason of online learning

COVID-19 pandemic offers the opportunities for students to take courses and complete their programs via the online platform without any physical attendance. A recent study (Dos Santos, 2021a) indicated that online student enrolment has increased from 30 to 70% during the COVID-19 pandemic. One hundred international students joined the study and shared positive feedback of online learning based on the social cognitive career theory. Another recent study (Dos Santos, 2021d) also indicated that domestic and international students enjoyed the online learning environment as many could continue their education, particularly during the lockdown and COVID-19 pandemic. The participants indicated that the online learning options should be continued to meet the needs of students from different background (Atmojo and Nugroho, 2020; AbuSa’aleek and Alotaibi, 2022; Chen and Du, 2022).

Online courses and lack of on-campus services and experiences

A recent report (Wallis, 2020) indicates that 78% of online students consider the online classroom environment to be as good as or better than traditional face-to-face methods, while nearly 80% of these students agreed or strongly agreed that online courses and degrees were worth the tuition fees. Student satisfaction and learning outcomes have become significant considerations for teachers, school leaders, and students. Another recent report (Hess, 2021) indicated some students might argue the online courses may not completely satisfy their needs, particularly the facilities and on-campus services that they cannot use as online students. The study further indicated that over 90% of American students wanted the university to reduce a part of the tuition fee as the students could not enjoy the on-campus facilities. Based on the statistics, although many students agreed that the online courses might have similar outcomes and achievements, they would like to pay fewer tuition fees due to the on-campus services (i.e., cannot enjoy the services) (Zvalo-Martyn, 2020).

Constructivist learning theory

In terms of the constructivist learning theory, Bruner (1973, 1996) argued that learning, particularly language learning, is a model in which learners build new knowledge and language acquisition based on their previous experiences. The cognitive structure is the mental and psychological actions and behavior that provide the performance, understanding, and background from which learners organize the experience, learning expectation, and sense-making process of their new knowledge. As learning is not a standalone process but a procedure combining previous experience and current situations, learners compare the current situation with their previous experience to build up new and appropriate experiences. Bruner (1973, 1996) identified four important factors of the constructivist learning theory: (1) teaching and learning models and strategies should focus on the connections and sense-making process between previous experience and the current situation; (2) teaching and learning models and strategies should motivate and activate learning interests and new areas of knowledge; (3) learners should be able to handle complex knowledge with no difficulties; (4) teaching and learning models, strategies, and goals should go beyond previous experience in building a new ground.

In short, the social cognitive career theory explored the motivations and reasons why individuals decide to do, continue, conduct, or discontinue a set of behavior before, during, and after some events and issues. And then, the employment of the constructivist learning theory explored the relationships and connections between the previous and current experiences and how these experiences make sense and build up the understanding and knowledge of the individuals and groups. Based on the directions of these two theoretical frameworks, the researcher advocated that the employments were useful to explore the two research questions of this study. As for the research questions, please refer to the following sub-section.

Appropriate online curriculum and activities with positive experiences

As for the feedback and opinions about the teaching and learning experiences and environments, some scholars (Tratnik et al., 2019) argue that students have benefited from foreign language courses in face-to-face environments due to peer interactions and exchanges. However, other scholars (Wei and Chou, 2020) have indicated that students learn actively and are satisfied with the online learning environment. Another recent report (Zvalo-Martyn, 2020) by the Association of American Colleges and Universities further indicated that the sample group (i.e., 24 university students) expressed positive learning experiences from their online university courses as many could use the digital education platform as the learning tools, particularly the online learning can establish the connections between the faculty and peers without borders. Two other studies (Brown et al., 2013; Kwee and Dos Santos, 2021) also indicated that vocational and hands-on experience courses might be delivered online as long as the university arrangements, curriculum designs, and student-centered activities may meet the needs and expectations for the achievements; students tended to express positive comments for their final evaluation.

Interactive experiences for online courses: Foreign language learning

Online teaching and learning are not new topics in university education. In 2006, scholars (Levy and Stockwell, 2006) showed that due to the rapid development of technology and upgrading of the classroom environment, many schools and universities had developed computer labs and rooms as essential facilities for many subjects, such as science, technology, and foreign languages. The relationship between online classroom interaction and outcome has received special attention over the decades due to the rapid development of distance learning education (Gok et al., 2021). An earlier study (Lantolf and Thorne, 2007) argued that sociocultural background is key in foreign language learning as students need to absorb knowledge from social and cultural backgrounds. Another newer study (Lin et al., 2017) indicated that provided the teaching and learning strategy and model were effective, the motivation of learners and the outcomes of foreign language courses remained the same. For example, a previous study (Kurucay and Inan, 2017) indicated that online-based groups worked well as many students were used to the online environment and technologically assisted teaching and learning from their previous experiences. In the online classroom environment of foreign language courses, some students expressed anxiety about not receiving immediate feedback from teachers and classmates. However, the participants indicated that effective corrective feedback could meet their learning outcome expectations (Martin and Alvarez Valdivia, 2017).

Concerns for the online foreign language courses

In foreign language and cultural learning, some scholars (O’Dowd, 2011) argue that the sense of internationalism and sociocultural understanding are some important factors. Although textbooks and printed materials provide excellent teaching and learning models, individuals cannot gain knowledge and language acquisition beyond the classroom environment. A study (Ozudogru and Hismanoglu, 2016) surveyed the understanding and beliefs of 478 university freshmen students about their online foreign language learning experience. Although some students shared negative experiences, this study outlined improvements in online foreign language courses. Another study (VanPatten et al., 2015) indicated no preference among 244 university students for either online or on-campus learning in their foreign language courses as both techniques delivered their expectations and goals. Although online foreign language courses may offer the flexibilities, some scholars believed that the interactions, activities, internationalism, and sociocultural experiences may not be gained via the online learning classroom environment. Currently, only a few studies focused on the cases in the United States. It is important to investigate the problems in the United States and the American foreign language classroom environments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the turning point for online teaching for almost all universities internationally, particularly in foreign language learning (Maican and Cocoradã, 2021). Although there are no contemporary statistics concerning the numbers of students affected by the global health crisis, almost all college and university students have had to attend online or blended courses due to government lockdown policies, particularly in the United States (Atmojo and Nugroho, 2020; Dhawan, 2020; Alqarni, 2021; Lau et al., 2021). As foreign language courses do not require lab or internship experience, most tuition has been delivered online (Maican and Cocoradã, 2021). A further study (Atmojo and Nugroho, 2020) indicated that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, English language courses should be conducted online to control the risk of infection. Although teachers and students could not attend foreign language courses in person, the virtual experiences did not necessarily limit the learning experiences and outcomes.

Materials and methods

Research design

The current study employed the general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006; Dos Santos, 2020b,2021c) with the interpretivism social paradigm (Burrell and Morgan, 1979). The general inductive approach is useful in this study because the general inductive approach allows the researcher to categorize the massive data into meaningful themes and groups. Based on the themes and groups, the researcher can further categorized the themes as the results.

First, technologically assisted teaching and learning tools and approaches have become popular methods in foreign language teaching and learning. The direction does not limit to a single or small group of schools and universities. In other words, teaching with technologically assisted tools and approaches is widely employed in the current foreign language teaching and learning arena. Therefore, the employment of the general inductive approach covered the wider situation in the current society.

Second, the COVID-19 pandemic provides opportunities for technologically assisted teaching and learning turning point(s). The teaching trends with technology may become one of the main themes in the current education systems, including foreign language subjects. Therefore, the wider perspectives and data collection procedures may be useful in this case.

Recruitment and participants

The purposive and snowball sampling strategies were employed (Merriam, 2009). First of all, based on a personal network, the researcher orally invited three participants to the study. Once three participants agreed with the study, the researcher formally sent the consent form, research protocol, interview questions, focus group activity questions, data collection procedure, risk statement, and related materials to the participants. In order to expand the population, the participants were told that after the first interview session, they should try their best to refer at least one participant for this study. After several rounds of discussions, 80 participants (N = 80) agreed to join the study. As this study was a small-scale study that only focused on the west coast states in the United States, the researcher tended to establish some limitations to upgrade the focus and aim of this study. In this case, the participants should meet all of the following points:

(1) Currently enrolled at a postsecondary education institution in the United States;

(2) Completed at least one semester of foreign language course via online method;

(3) Currently located in one of the west coast states in the United States (e.g., Oregon, California, Washington, Alaska, and Hawaii).

(4) At least 18 years old.

Data collection

Three data collection tools were employed, including virtual-based, semi-structured and one-on-one interview session, focus group activity, and member checking interview session. First, the virtual-based, semi-structured, and one-on-one interview sessions were useful. Creswell (2012) indicated that interview session is one of the common qualitative data collection tools in social sciences. Merriam (2009) advocated that the individual-based interview allows the individual(s) to share their stories and ideas in a private setting. Some individuals tend not to share their personal backgrounds in front of a group of people. Therefore, the current arrangement for interview sessions might allow the individual(s) to share their understanding and experiences with the researcher. In this case, the interview sessions were appropriate to collect rich data from the participants about their understanding and perspective of online courses in foreign language learning. Based on the theoretical frameworks and some previous studies (Bruner, 1973, 1996; Lent and Brown, 1996; Dos Santos, 2020a,2021b,2021c), the researcher developed the interview questions. The interview session mainly concerned the experiences, learning expectations, and intentions for future online courses after the COVID-19 pandemic. The interview sessions lasted from 90 to 112 min.

After completing all interview sessions, the researcher arranged the virtual-based focus group activities with the participants. The focus group activities mainly concerned the experiences, personal stories sharing, understanding of online courses, and their intention of online courses after the COVID-19 pandemic. Both Morgan (1998) and Merriam (2009) advocated that qualitative researchers may employ more than one data collection tool, such as interview and focus group activity, to increase the participants’ data. Focus group activity is useful because a group of individuals may share similar ideas within a similar background and situation. In this case, the motivation and experiences from the online learning platform and experience. As for the focus group activities, the researcher took the role of the listener as the researcher wanted to observe and collect the in-depth understanding and lived stories of the participants (who shared similar backgrounds and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic). The researcher developed the focus group questions based on the theoretical frameworks and some previous studies (Bruner, 1973, 1996; Lent and Brown, 1996; Dos Santos, 2020a,2021a,b). Eight participants formed an individual focus group activity. Therefore, ten focus group activities were established. The focus group activities lasted from 113 to 132 min.

After the researcher collected and categorized the data based on each participant, the researcher returned the data to the participant via email for confirmation. A follow-up member-checking interview session was hosted for each participant via virtual-based interview. During the member-checking interview sessions, all participants agreed with their materials. Each member checking interview session lasted from 34 to 41 min. All the data collection procedures were digitally recorded. All participants agreed with this arrangement and accepted the sessions were recorded.

Data analysis

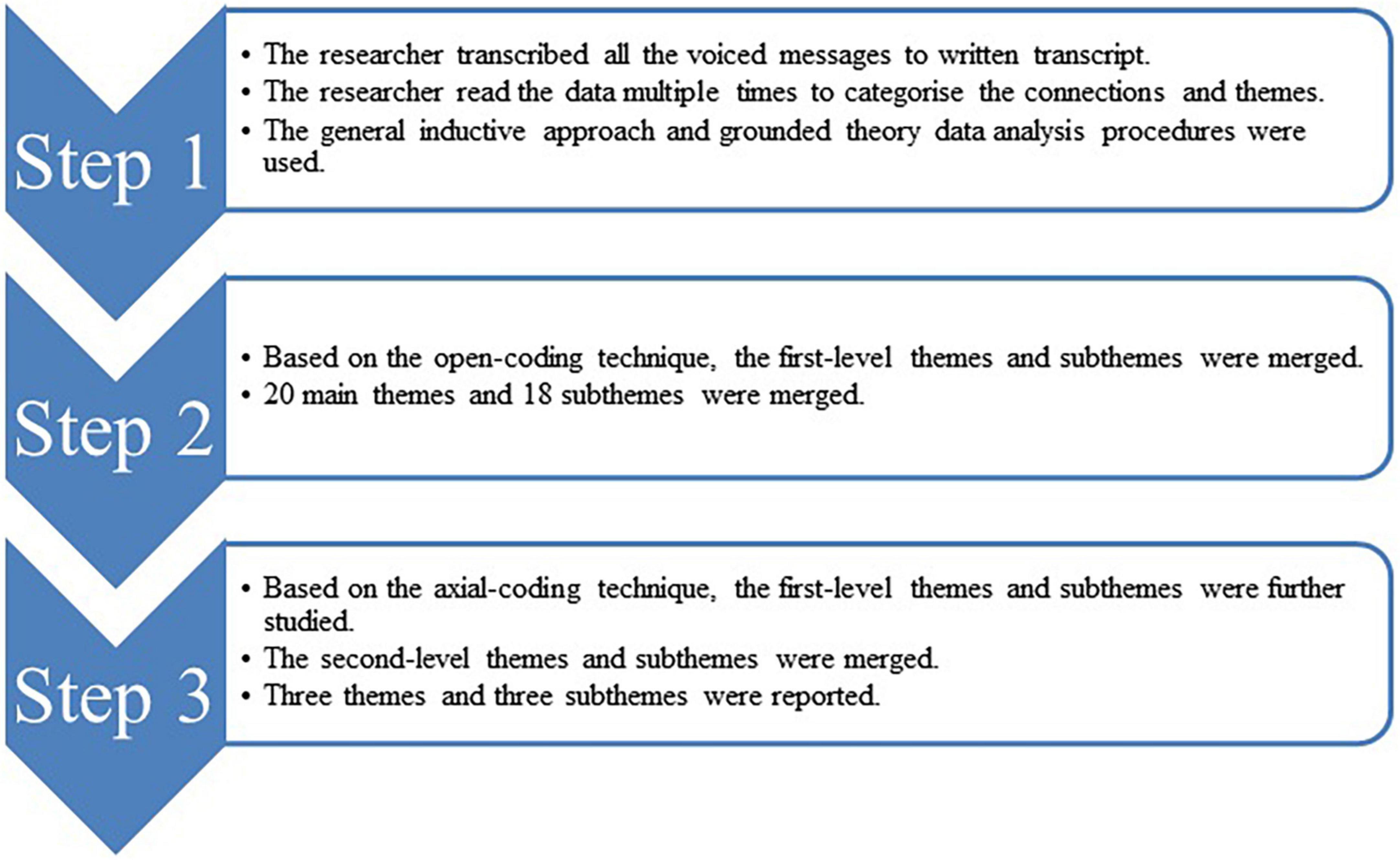

The researcher (i.e., worked as the sole researcher) transcribed all the voiced messages into written transcripts. The researcher read the data multiple times to categorize the connections and themes. Therefore, the researcher employed two data analysis procedures and tools in this study, including the general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006) and the grounded theory approach (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) for data analysis.

First, the researcher employed the open-coding technique (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) to narrow down the massive data to themes and subthemes as the first-level themes. At this point, 20 themes (e.g., flexibility, online courses with schedule, family responsibilities, the same outcomes and learning achievements, domestic learning, international learning, etc.) and 18 subthemes (e.g., skill upgrading, the online platform options, students from different states and cities, peer-to-peer exchanging, etc.) were merged.

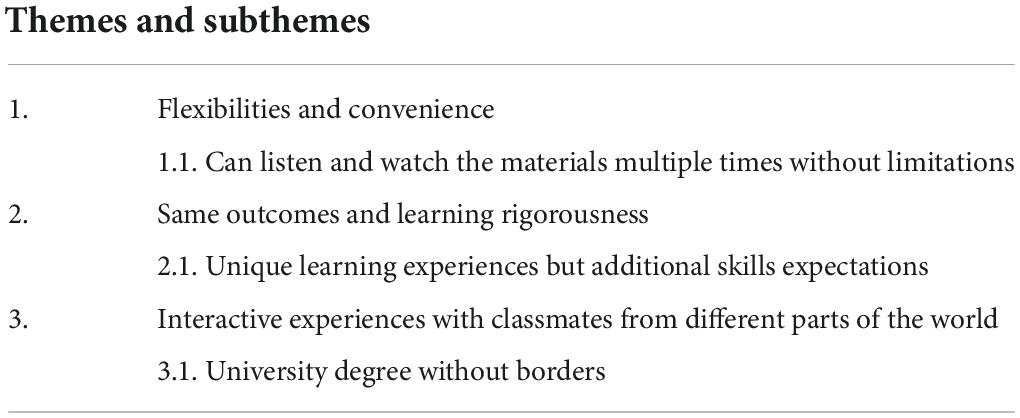

However, researchers (Merriam, 2009) suggested that further data analysis procedures should be conducted. Therefore, the axial-coding technique (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) was employed. As a result, three themes (i.e., flexibilities and convenience, same outcomes and learning rigorousness, and interactive experiences with classmates from different parts of the world) and three subthemes (i.e., can listen and watch the materials multiple times without limitations, unique learning experiences but additional skills expectations, and university degree without borders) were yielded as the second-level themes. Figure 1 outlines the data analysis procedure.

Human subject protection/ethical consideration

Privacy is the most important idea in this study. Therefore, the signed consent forms, personal information, contact information, school information, grades, locations, address, email address, voiced messages, written transcripts, computer, and related information were locked in a password-protected cabinet. Only the researcher could read the information. More importantly, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was supported by the Woosong University Academic Research Funding. After the researcher completed the study, all the related materials were deleted and destroyed in order to protect the information of all parties. Please note no payments were given to any parties. The study was supported by the Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2021/2022 (2021-01-01-07).

Results and findings

Although many students take their courses in different global communities, many shared similar lived stories and experiences, particularly in their foreign language learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The researcher categorized three themes and subthemes based on the qualitative data. Table 1 outlines the themes and subthemes. Please note, to provide a comprehensive comparison, the researcher combined the results chapter and discussion chapter for immediate comparison.

Flexibilities and convenience

…I can learn my Spanish courses in my free time…I am not a traditional student and have to work for my family…I can listen to and read my lessons and lecture notes during my break time at work…my way back home…before sleep…I can still learn the same knowledge and vocabulary without my physical attendance…I submit my assignments and projects on time as other students are…excellent learning option for us…(Participant #60, Focus Group)

All participants expressed flexibility and convenience as the strongest preferences in their online foreign language courses. A group of non-traditional, returning, adult, and evening class students indicated that the traditional face-to-face courses had always limited their selections and learning preferences as they had to work and take care of their families during the daytime (Dos Santos, 2020a). Although weekend and night courses are sometimes available, the options are limited. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the online learning options offered them the same opportunities as traditional on-campus students. The researcher captured the following stories based on this preference:

…we cannot find any foreign language courses other than Spanish and French in the evening…I want to learn Chinese and Japanese…but they were only available during the morning and in the afternoon…but the online option, many evening students could take Chinese and Japanese…I hope the university can continue this online option for us…(Participant #34, Interview)

…I want to study Spanish popular literature and children’s literature as my elective courses…traditionally, based on the previous course catalog, only one professor teaches these courses…usually in the morning time…but because of the COVID…these two courses were offered online with recorded video sessions…I registered for these two courses immediately…it is a really good chance for us…to enjoy the courses as evening and part-time students…(Participant #10, Focus Group)

For example, some minority and less popular foreign language courses had only one session during each academic year. Students facing time conflicts with other courses would not be able to take either the foreign language course or their subject courses in the academic year. However, online courses provide greater flexibility. The researcher captured two stories:

…I am a double major student in Mathematics and Japanese…I have to take the Japanese literature course for my major…but only one session is there every year…if I miss it, I have to wait for another year…but at the same time, I have to take the math course for my math major…it was the advanced level course so only one course was available…this happened last year…but this year because we can take the online courses…the problem solved…(Participant #41, Interview)

The flexibility of online courses solved schedule conflicts between courses and university departments. Students who needed to take multiple foreign languages as their major requirement also expressed interest in online delivery, for example:

…in the translation studies department, we have to take at least two foreign languages beyond our native language…my native language is English…and I have to take Spanish and Italian as the second and third…but many of the translation, Spanish and Italian courses…were overlapped together before the pandemic…I am glad that the online courses…provide me with the chance…so I can finish my degree in 4 years…(Participant #3, Interview)

Can listen and watch the materials multiple times without limitations

In most online foreign language courses, instructors upload teaching and learning materials and exercises online before each lesson so that the students can read the materials before and after the lessons. All participants saw this as a positive experience because they could download and re-read the materials during their leisure time after the lesson. During driving time and breaks, they could play the audio and videos of language exercises. One said:

…in fact, commuting and travel jam waste my time…but if I could listen to the exercises in my car, I could save some time at home…and I do not have to sit in the classroom for the audio and to listen, I can sit in my car and practice the exercise…I learnt a lot because I can listen to the previous chapters and the new chapter…I connected all the vocab and sentences …(Participant #14, Interview)

For example, some participants mentioned that their instructors asked them to listen and watch earlier chapters to connect with their current grammatical structure. In this way, the learners could connect and refresh their previous work to their current materials:

…we were in chapter 34 last week, but our professor asked us to re-listen and re-watch the materials from chapter 22…we didn’t understand why. Still, when we read the old materials again, they learnt some new ideas…the grammatical structures or the slang from the videos…great practices to refresh our knowledge with some old stuff…(Participant #45, Focus Group)

Last but not least, almost all participants indicated that their instructors might release some self-made materials, speaking exercises, personal videos, and materials from the instructors’ personal library from the face-to-face lessons. However, all these materials beyond the textbook were not given to them (i.e., could only be listened to and watched inside the classroom). In this case, many indicated that their instructors uploaded these materials (i.e., materials from instructors’ personal library) on the online platform. Therefore, they could enjoy some materials with their instructors’ comments and perspectives, a story was captured:

…in contemporary literature and pop culture courses…we have to read a lot of reviewers and comments from the real speakers of the languages…but the grammatical structure and vocab…I did not understand it…they just don’t follow the textbook structures…in my intermediate courses on campus 2 years ago, my professor wrote them on the blackboard…I could download, read, listen, and watch it multiple times as it is online…(Participant #49, Focus Group)

In conclusion, the flexibility of the delivery options, flexible time for the lessons, and re-readable materials beyond the textbook were three of the main key terms under this theme and subtheme. Based on some previous studies (Lee and Choi, 2011; VanPatten et al., 2015; Mozelius and Hettiarachchi, 2017), some scholars believe that students tend to take online courses due to their flexibility and busy working schedules. The results from these studies further echoed the situation before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Same outcomes and learning rigorousness

A group of participants said that online and on-campus foreign language courses allowed them to improve their reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills with their classmates and teachers during the live online lessons. The learning outcomes and expectations were the same as they all watched the live lesson requiring virtual face-to-face interaction with others. A story was captured:

…some people told me that they could not speak in front of the computer…so they don’t want to speak…but if you don’t want to speak…in front of the computer or in front of the classroom…you are not going to speak too…this is just an exercise…I see many people speaking in their TikTok videos…just don’t give yourselves any excuses…(Participants #21, Focus Group)

In this case, all considered the role of critical thinking and time management training to be essential in university study. The current COVID-19 pandemic and the online teaching and learning arrangements provided effective training and opportunities. As one said:

…I do not think traditional on-campus courses are better than online courses…we are all here to learn the same courses and the same skills…the delivery options and models are just the models…if you want to learn the knowledge…even if you just read the textbooks without a teacher…people can still learn the greatest knowledge from the textbooks and materials…I don’t want to discriminate between these two methods…(Participant #38, Interview)

Unique learning experiences but additional skills expectations

Although current statistics (Wallis, 2020) indicate that more than half of the student population has experienced the tools of distance learning and online courses, many still are new to this area. Regarding time management, almost all participants indicated that they have set up their personal goals and time schedules for each unit and exercise as they are not required to join the physical classroom environment. A participant shared the following story:

…we used to have to go to the class for the language course in the evening…but we don’t have to for now…but we still have to do the same homework, exam, project, and exercise…my professor told us that we are all adults…he would not force us to read the materials…we have to be responsible…I have learnt some skills to set up weekly goals and schedules…very good opportunities because we gained something new from the school…(Participants #58, Focus Group)

Another participant shared her story of balancing the work between family, school, and workplace as a mother with multiple responsibilities:

1…being a student, a mother, and a full-time worker is very hard…but at least for this semester, many working students could release the stress from attending all physical courses on campus in the evening…we only need to upload the materials on time…but we learn the same knowledge and complete the same exercises and exams…many of us enjoyed this online learning experiences…although a few complained about the interactions and oral communication…I don’t see there are any differences…(Participant #19, Interview)

Echoing the reflection of some scholars (Gorbunovs et al., 2016), a large group of participants indicated that self-regulation and self-discipline are key to online learning experiences, regardless of age and background. The researcher captured a story:

…because we do not have to go to class and some of my courses in Spanish do not need us to attend the live lessons…I have to learn how to balance my time…also, set up goals to complete my assignment on time…my son only attended his lessons online…he also needs to complete his assignment on time and online…I have to teach my son to finish his work appropriately…and I have to be the right model…if I cannot complete mine appropriately, how can I tell my son to do so?… (Participant #7, Interview)

Interactive experiences with classmates from different parts of the world

The online courses connected domestic and international students worldwide through the online platform. All participants indicated they had at least one international student and a group of domestic students not living in their home state but connected via the online platform. This unique experience could not be acquired through on-campus experience as all are required to be on campus for physical lessons. The researcher captured two interesting stories:

…I have several students from the New England region, one from Hawaii, and one from Alaska in my French course…they should come back there on-campus…but the lockdown allowed us to connect online…we have to do homework…introduce our home city in French…I could see the view in Alaska and Hawaii…in the same 90-min lesson in life…not from the recorded videos or so…unique experiences from online learning…(Participant #27, Focus Group)

Another story was about the global connection with international students:

…we had many students from China, South Korea, Singapore, India, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, and the Middle East in our Spanish language courses over two semesters…I didn’t realize that we had many international students in my school…who are interested in the Spanish language…we exchanged a lot of knowledge and ideas from the online platforms and forums…I grouped with a Chinese student for the speaking project…I am very happy with this unique experience…(Participant #51, Interview)

University degree without borders

Besides learning experiences with students from different global communities, all expressed satisfaction with the unique experiences of non-traditional, returning, adult, and evening class students who had extensive working experience before joining university. From the perspective of the traditional age students, there was an expression of satisfaction in the experience of these less traditional classmates in the online classroom environment. Two stories were captured:

…I am so happy that I could chat with many experienced classmates who have many years of working experience in the field…although many of them learnt Spanish due to the general education requirement…they shared a lot of lived experiences in their subject courses and vocational skills to us…we could not have these chats during the daytime courses…I wish I can have these conversations in the future…(Participant #80, Focus Group)

Another participant shared ideas on the connection between foreign language and vocational knowledge from some of the experienced students in the online classroom environment:

…one of the projects was to use Spanish to do the role-play exercises based on our academic major…my major is nursing so I was paired with another public health classmate…my classmate was an evening student…she was a mother with 20 years of working experiences in a big chained hospital…I learnt a lot of speaking skills from her in English and Spanish…I am glad that we could connect because of this online course…(Participant #71, Focus Group)

Many non-traditional, returning, adult and evening class students enjoyed pairing up with traditional-age students because of their fresh ideas and similarities with their children. Many non-traditional, returning, adult, and evening class students are in their early 40s or 50s and are at school simultaneously as their college-aged children. When the researcher asked about their experience and learning motivation, many expressed a strong satisfaction and motivation in online learning. One story was given:

…my son and I did not go to the same university…but we learnt the same level of Spanish course in the same semester…I chatted with my son about the Spanish lesson…and I introduced my classmates to my son too…we all three talked together and shared some ideas …my classmate’s mother is going to school for a nursing degree, too…the online course connected two families together…(Participant #65, Focus Group)

Discussion

With a reflection on a previous study about distance learning and online learning (VanPatten et al., 2015), both traditional-age and non-traditional students indicated that the online-based courses allowed them to study their courses and requirements during their free time. More importantly, as some courses (e.g., elective courses) could only be offered once per year during the daytime (e.g., 9 AM), some part-time and working students could not complete the courses. Therefore, the current online arrangement met the expectations of both parties (Jaggars, 2014; Tratnik et al., 2019). A group of non-traditional, returning, adult, and evening class students indicated that the traditional face-to-face courses had always limited their selections and learning preferences as they had to work and take care of their families during the daytime (Dos Santos, 2020a). However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the online learning options offered them the same opportunities as traditional on-campus students.

Besides the input from the non-traditional, returning, adult, and evening class students, many full-time students also expressed an interest in the online delivery option for their foreign language courses, particularly the flexibilities (Dos Santos, 2020a; Kwee, 2021; Maican and Cocoradã, 2021). However, online courses provide greater flexibility.

Many previous studies (Pitarch, 2018; Liu and Li, 2019) have indicated that re-assessment and re-evaluation after lessons could upgrade and connect learners’ previous knowledge with their current learning materials. For example, with the reflection of a previous study (Atmojo and Nugroho, 2020), all participants said they could download the audio and videos from the online learning platform to their cellphones and iPads. Based on the reflection of a previous study (Damayanti and Rachmah, 2020), nearly all said that if they listened to the whole series of audios and videos at home, they could connect early chapters and exercises from previous semesters for better understanding and practice.

Based on some previous studies (Lee and Choi, 2011; VanPatten et al., 2015; Mozelius and Hettiarachchi, 2017), some scholars believe that students tend to take online courses due to their flexibility and busy working schedules. The results from these studies further echoed the situation before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although some students may return to traditional face-to-face classroom environments after the COVID-19 pandemic, online teaching and learning options should remain active, as both traditional and non-traditional students may benefit the delivery. In the aspect of online teaching and learning, participants and previous studies (O’Dowd, 2011; Chan et al., 2021; Iqbal and Sohail, 2021)also argued that the online learning platform and environment should not have any significant differences in terms of outcomes and students’ achievements. In this case, many participants believed that online learning and online learning platform offered them the convenience and opportunities to gain new knowledge under the new technology.

Following social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996) and constructivist learning theory (Bruner, 1973, 1996), participants expressed their motivation for online courses due to the greater flexibility and freedom of learning. Such flexibility was unavailable under the traditional system because many courses had overlapped. Also, the online experiences further encouraged their learning experiences, motivations, and opportunities during and potentially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although some students may return to traditional face-to-face classroom environments after the COVID-19 pandemic, online teaching and learning options should remain active, as both traditional and non-traditional students may benefit the delivery. In the aspect of online teaching and learning, participants and previous studies (O’Dowd, 2011; Chan et al., 2021; Iqbal and Sohail, 2021) also argued that the online learning platform and environment should not have any significant differences in terms of outcomes and students’ achievements. In this case, many participants believed that online learning and online learning platform offered them the convenience and opportunities to gain new knowledge under the new technology.

Following social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996) and constructivist learning theory (Bruner, 1973, 1996), participants expressed their motivation for online courses due to the greater flexibility and freedom of learning. Such flexibility was unavailable under the traditional system because many courses had overlapped. Also, the online experiences further encouraged their learning experiences, motivations, and opportunities during and potentially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some previous studies and researchers (Al-Kumaim et al., 2021) have argued that online teaching and learning strategies cannot provide the same outcomes, experiences, performances, and learning rigorousness to the learners. A recent study (Meşe and Sevilen, 2021) further argued that the lack of social interaction between peers and teachers could result in foreign language learners’ negative motivation and learning performance at university. However, in this case, all participants felt that the learning outcomes and expectations had been met in their online foreign language courses.

Furthermore, reflecting on a study from Güntaş et al. (2021), almost all participants agreed that university education and experience train individuals in critical thinking skills and effective time management. All university students believed that the online foreign language courses provided them with excellent opportunities to organize their time management between their major courses and foreign language exercises (Biletska et al., 2021).

Reflecting on previous studies on online and distance learning education (Sykes and Roy, 2017; Gok et al., 2021), many participants considered the rigorous learning of both traditional and online courses equal, without any significant differences. Online courses require additional effectiveness, self-regulation, and self-motivation for their outcomes and achievements. As all completed the same exercises, exams, and homework by the deadline, all participants argued that the learning outcomes were as strong as the on-campus courses.

Many students still need time to adjust their learning expectations and personal beliefs to online courses, such as time management, self-regulation, and self-discipline (Brown et al., 2015; Mozelius and Hettiarachchi, 2017).

The flexibility provided excellent possibilities for students to access and read the materials in their leisure time. However, the flexibility also led to some students dropping out as some could not organize and arrange their time schedules effectively (Brown et al., 2015). However, the online learning achievements and outcomes do not differ based on the participants. In other words, many participants believed they could gain new knowledge and ideas in both on-campus and online classroom environments (Yukselturk et al., 2014; Wright, 2017; Rasheed, 2020). More importantly, many believed the online teaching and learning environment could enhance their time management skills and interdisciplinary studies beyond the on-campus classroom environments (Brown et al., 2013).

Based on the social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996), the researcher confirmed that many participants decided to learn and potentially continue their studies with online courses, motivated by the flexibility and self-arranged time schedules that fitted with their other responsibilities. Also, with a reflection on the constructivist learning theory (Bruner, 1973, 1996), participants indicated that their previous time management experience had established their current responsibilities and expectations of the online courses.

Many previous studies (Lee and Rice, 2007; Choudaha, 2016) have highlighted the United States as a well-known destination for international students, including students in community colleges, universities, and graduate schools. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many international students could not return to the United States for on-campus lessons and experiences.

In conclusion, internationalism and student satisfaction are important for these participants. Firstly, reflecting on the social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996), many felt that internationalism and idea exchange played important roles in foreign language learning through listening to conversations and ideas from people in different global communities. Unlike in the past decades, students can study and attend classes and courses via online teaching and learning platforms internationally. Besides international students, non-traditional, evening, returning, and adult students also enjoy the flexibility of the online teaching and learning platform due to the development of technology (Olesen-Tracey, 2010; AbuSa’aleek and Alotaibi, 2022). The current online learning experience provided this unique opportunity as the online platform connected students inside and outside the country, thus appropriately meeting students’ motivations.

Secondly, reflecting on the constructivist learning theory (Bruner, 1973, 1996), many participants expressed that they could improve their subject and foreign language knowledge with students from different backgrounds, such as non-traditional students, and that the learning experiences were rich. The findings of this study appropriately met the directions of two theoretical frameworks and answered the research questions.

Limitations and future research developments

Two limitations and future research developments were identified. Firstly, the current study collected data from 80 participants (N = 80) learning and completing their foreign language requirements in the United States. Although none of their academic majors was in a foreign language, the study covered the voices and stories of many participants who had to complete a general education requirement in a foreign language via online platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, students in other classes, university major(s), colleges, universities, and backgrounds may face similar issues and problems. Therefore, future research studies could cover the experience of other students, such as students in foreign language majors, to capture a broader understanding and perspective.

Secondly, the United States has over a million active student enrolments annually. The current study only covered students’ voices in the Pacific states and regions. In the future, scholars with greater funding and samples should expand the population to other American regions, such as the New England region, to capture a wider perspective.

Contributions to the practice and conclusion

First, the current study used foreign language courses and students to understand the motivations of learning and online learning experiences, particularly in American university environments. The findings of this study successfully filled up the gap in online learning, particularly the motivations and intentions of delivery methods after the COVID-19 pandemic from students’ perspectives. Students are the users of online courses. Instructors and university departments should create and design courses and delivery options that meet the demands and needs of their students. Online courses will become a popular trend in the university environment after the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to gather the students’ voices to upgrade the teaching and learning approaches.

Second, university leaders, department heads, and teachers may use this study as the blueprint to reform and design some online courses, particularly in foreign language teaching and learning, to help non-traditional, returning, evening, and adult students who cannot attend the physical classes. As most participants advocated that online delivery does not limit their motivations and achievements, the development of online foreign language courses are greatly needed.

Third, although the participants were foreign language course takers and students, they took different online courses in their major subjects due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on their sharing, many advocated that the online courses and virtual learning environment were enjoyable. Based on the voices and suggestions, the curriculum planners and department leaders may expand and continue the online courses and delivery options after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Woosong University Academic Research Funding Department. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2021.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AbuSa’aleek, A. O., and Alotaibi, A. N. (2022). Distance education: an investigation of tutors’ electronic feedback practices during coronavirus pandemic. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 17, 251–267. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v17i04.22563

Al-Kumaim, N. H., Mohammed, F., Gazem, N. A., Fazea, Y., Alhazmi, A. K., and Dakkak, O. (2021). Exploring the impact of transformation to fully online learning during COVID-19 on Malaysian university students’ academic life and performance. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 15:140. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v15i05.20203

Alqarni, N. (2021). Language learners’ willingness to communicate and speaking anxiety in online versus face-to-face learning contexts. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 20, 57–77. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.20.11.4

Atmojo, A. E. P., and Nugroho, A. (2020). EFL classes must go online! teaching activities and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Regist. J. 13, 49–76. doi: 10.18326/rgt.v13i1.49-76

Biletska, I. O., Paladieva, A. F., Avchinnikova, H. D., and Kazak, Y. Y. (2021). The use of modern technologies by foreign language teachers: developing digital skills. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 5, 16–27. doi: 10.37028/lingcure.v5nS2.1327

Brown, J., Mao, Z., and Chesser, J. (2013). A comparison of learning outcomes in culinary education: recorded video vs. live demonstration. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 25, 103–109. doi: 10.1080/10963758.2013.826940

Brown, M., Hughes, H., Keppell, M., Hard, N., and Smith, L. (2015). Stories from students in their first semester of distance learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 16, 1–17. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v16i4.1647

Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. doi: 10.4159/9780674251083 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burrell, G., and Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. London: Heinemann.

Chan, A. K. M., Botelho, M. G., and Lam, O. L. T. (2021). The relation of online learning analytics, approaches to learning and academic achievement in a clinical skills course. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 25, 442–450. doi: 10.1111/eje.12619

Chen, C., and Du, X. (2022). Teaching and learning Chinese as a foreign language through intercultural online collaborative projects. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 31, 123–135. doi: 10.1007/s40299-020-00543-549

Choudaha, R. (2016). Campus readiness for supporting international student success. J. Int. Students 6, I–V. doi: 10.32674/jis.v6i4.318

Creswell, J. (2012). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Damayanti, F., and Rachmah, N. (2020). Effectiveness of online vs. offline classes for EFL classroom: a case in a higher education. J. English Teach. Appl. Linguist. Lit. 3, 19–26. doi: 10.20527/jetall.v3i1.7703

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020a). I want to become a registered nurse as a non-traditional, returning, evening, and adult student in a community college: a study of career-changing nursing students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:5652. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165652

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020b). Male nursing practitioners and nursing educators: the relationship between childhood experience, social stigma, and social bias. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:4959. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144959

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021a). Completing engineering degree programmes on-line during the Covid-19 pandemic: Australian international students’ perspectives. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 23, 143–149.

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021b). Developing bilingualism in nursing students: learning foreign languages beyond the nursing curriculum. Healthcare 9:326. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9030326

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021c). I want to teach in the regional areas: a qualitative study about teachers’ career experiences and decisions in regional Australia. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 11, 32–42. doi: 10.36941/jesr-2021-2103

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021d). Motivation of taking distance-learning and online programmes: a case study in a TAFE institution in Australia. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 10, 11–22. doi: 10.36941/ajis-2021-2149

Gok, D., Bozoglan, H., and Bozoglan, B. (2021). Effects of online flipped classroom on foreign language classroom anxiety and reading anxiety. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1950191

Gorbunovs, A., Kapenieks, A., and Cakula, S. (2016). Self-discipline as a key indicator to improve learning outcomes in e-learning environment. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 231, 256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.09.100

Güntaş, S., Gökbulut, B., and Güneyli, A. (2021). Assessment of the effectiveness of blended learning in foreign language teaching: Turkish language case. Laplage Em. Rev. 7, 468–484.

Hess, A. J. (2021). As College Students Head Back to Class, Some say Benefits of Online Learning should not be Forgotten. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: CNBC.

Iqbal, S., and Sohail, S. (2021). Challenges of learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Gandhara Med. Dent. Sci. 8:1. doi: 10.37762/jgmds.8-2.215

Jaggars, S. (2014). Choosing between online and face-to-face courses: community college student voices. Am. J. Distance Educ. 28, 27–38. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2014.867697

Kurucay, M., and Inan, F. A. (2017). Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Comput. Educ. 115, 20–37. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.010

Kwee, C. (2021). I want to teach sustainable development in my English classroom: a case study of incorporating sustainable development goals in English teaching. Sustainability 13:4195. doi: 10.3390/su13084195

Kwee, C., and Dos Santos, L. M. (2021). “Will I continue teaching sustainable development online? an international study of teachers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education, doi: 10.5220/0010396600230034 (Hong Kong: The Open University of Hong Kong), 340–359.

Lantolf, J., and Thorne, S. L. (2007). “Sociocultural theory and second language learning,” in Theories in second language acquisition, eds B. van Patten and J. Williams (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 201–224.

Lau, E. Y. H., Li, J., and Bin Lee, K. (2021). Online learning and parent satisfaction during COVID-19: child competence in independent learning as a moderator. Early Educ. Dev. 32, 830–842. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2021.1950451

Lee, J., and Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? international student perceptions of discrimination. High. Educ. 53, 381–409. doi: 10.1007/s10734-005-4508-4503

Lee, Y., and Choi, J. (2011). A review of online course dropout research: implications for practice and future research. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 59, 593–618. doi: 10.1007/s11423-010-9177-y

Lent, R., and Brown, S. (1996). Social cognitive approach to career development: an overview. Career Dev. Q. 44, 310–321. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00448.x

Lent, R., Brown, S., and Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 45, 79–122. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Levy, M., and Stockwell, G. (2006). CALL Dimensions: Options and Issues in Computer-assisted Language Learning. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203708200

Lin, C.-H., Zhang, Y., and Zheng, B. (2017). The roles of learning strategies and motivation in online language learning: a structural equation modeling analysis. Comput. Educ. 113, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.014

Liu, M., and Li, X. (2019). Changes in and effects of anxiety on English test performance in Chinese postgraduate EFL classrooms. Educ. Res. Int. 2019, 1–11. doi: 10.1155/2019/7213925

Maican, M.-A., and Cocoradã, E. (2021). Online foreign language learning in higher education and its correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13:781. doi: 10.3390/su13020781

Martin, S., and Alvarez Valdivia, I. M. (2017). Students’ feedback beliefs and anxiety in online foreign language oral tasks. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 14:18. doi: 10.1186/s41239-017-0056-z

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Meşe, E., and Sevilen, Ç (2021). Factors influencing EFL students’ motivation in online learning: a qualitative case study. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 4, 11–22. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11051-2

Morgan, D. (1998). The Focus Group Guidebook. Thousand Oaks CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, doi: 10.4135/9781483328164

Mozelius, P., and Hettiarachchi, E. (2017). Critical factors for implementing blended learning in higher education. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 6, 37–51. doi: 10.1515/ijicte-2017-2010

National Center for Education Statistics (2020). National Center for Education Statistics: Distance Learning. Washington, D.C: National center for education statistics.

O’Dowd, R. (2011). Online foreign language interaction: moving from the periphery to the core of foreign language education? Lang. Teach. 44, 368–380. doi: 10.1017/S0261444810000194

Olesen-Tracey, K. (2010). Leading online learning initiatives in adult education. J. Adult Educ. 39, 36–39.

Ozudogru, F., and Hismanoglu, M. (2016). Views of freshmen students on foreign language courses delivered via e-learning. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. 17, 31–47. doi: 10.17718/tojde.18660

Pitarch, R. C. (2018). An approach to digital game-based learning: video-games principles and applications in foreign language learning. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 9:1147. doi: 10.17507/jltr.0906.04

Rasheed, R. (2020). What’s Distance Learning?: Distance Learning lets you Study Remotely without Regular Face-to-face Contact with a Teacher in the Classroom. Available online at: https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/student-advice/what-to-study/what-is-distance-learning (accessed March 6, 2021).

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Sykes, D., and Roy, J. (2017). A review of internship opportunities in online learning: building a new conceptual framework for a self-regulated internship in hospitality. Int. J. E-Learning Distance Learn. 32, 1–17.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 27, 237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748

Tratnik, A., Urh, M., and Jereb, E. (2019). Student satisfaction with an online and a face-to-face business English course in a higher education context. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 56, 36–45. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2017.1374875

VanPatten, B., Trego, D., and Hopkins, W. P. (2015). In-class vs. online testing in university-level language courses: a research report. Foreign Lang. Ann. 48, 659–668. doi: 10.1111/flan.12160

Wallis, L. (2020). Growth in Distance Learning Outpaces Total Enrollment Growth. Available online at: https://www.qualityinfo.org/-/growth-in-distance-learning-outpaces-total-enrollment-growth (accessed January 3, 2022).

Wei, H.-C., and Chou, C. (2020). Online learning performance and satisfaction: do perceptions and readiness matter? Distance Educ. 41, 48–69. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2020.1724768

Wright, B. M. (2017). Blended learning: student perception of face-to-face and online EFL lessons. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 7:64. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v7i1.6859

Yukselturk, E., Ozekes, S., and Türel, Y. (2014). Predicting dropout student: an application of data mining methods in an online education program. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 17, 118–133. doi: 10.2478/eurodl-2014-2018

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, computer-aided language learning, distance learning, foreign language teaching, online course, online teacher, technologically assisted teaching, technology education

Citation: Dos Santos LM (2022) Online learning after the COVID-19 pandemic: Learners’ motivations. Front. Educ. 7:879091. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.879091

Received: 18 February 2022; Accepted: 05 September 2022;

Published: 20 September 2022.

Edited by:

Ana Luísa Rodrigues, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Susanto Susanto, Universitas Bandar Lampung, IndonesiaThanh-Thao Luong, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Japan

Copyright © 2022 Dos Santos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luis M. Dos Santos, bHVpc21pZ3VlbGRvc3NhbnRvc0B5YWhvby5jb20=

Luis M. Dos Santos

Luis M. Dos Santos