- 1School of Education & Social Policy, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, United States

- 3Office of the Provost, Purdue University Global, West Lafayette, IN, United States

Many postsecondary education institutions in the United States struggle to effectively support high levels of academic achievement and college completion among their students. This is especially true at less selective and online colleges and universities that are understudied but serve an increasing number of students. Psychological factors may play an important role in promoting positive student outcomes during the college years. Two randomized controlled experiments including online university students focused on the potential influence of opportunities for students to reflect upon their future identities or ideas about their lives in the years to come. In Study 1 (N = 1,042), a course activity designed to engage students’ future identities showed positive effects on course grades and persistence in college during the next semester. In Study 2 (N = 2,515), a more rigorous design demonstrated the effects of activating future identities on specific motivational processes with positive consequences for academic outcomes. Together, the experiments suggest that educators and advisors should engage with how students imagine their futures in order to help support student success.

Introduction

Increased access to a college education is inherently limited without an emphasis on college success and completion (Titus, 2006; Goldrick-Rab et al., 2016; Long, 2018; Allensworth and Clark, 2020). Millions of students pursue postsecondary education and 4-year college degrees every year (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021). At the same time, in 2018, over 40% of students who enrolled in a postsecondary degree program in the United States had not earned a degree after 6 years (Shapiro et al., 2018). In a context of high college costs, these students often find themselves in financial debt or economic insecurity as they approach the labor market without the college degree they aimed to obtain (Elliott and Lewis, 2015). The current studies test whether a specific form of psychological support that is developed from identity-based motivation theory can effectively reinforce students’ specific motivational processes, improve achievement, and increase persistence in a college context with especially low rates of completion.

Identity-Based Motivation and Academic Achievement

Identity-based motivation theory provides a guiding framework to understand how people navigate challenges and opportunities as they develop and pursue their goals (Oyserman and Destin, 2010; Oyserman, 2015). The theory describes identities as dynamic and shaped by the everyday influences that people encounter in their environment. Further, these dynamic ways that people understand themselves guide their goal-related behaviors, including their responses to difficulty and persistence over time. Future identity is a particularly relevant part of identity-based motivation that refers to how a person imagines who they might be in the years to come and how they might reach that image (Nurra and Oyserman, 2018). Future identities can provide a powerful and genuine source of motivation to persist when facing obstacles during the pursuit of valued goals, which are likely to be particularly important as students pursue a college degree (Oyserman et al., 2015).

Components and Processes of Motivating Future Identities

Studies demonstrate that when students of various ages are randomly assigned to develop or bring to mind certain types of future identities, they experience stronger motivation and show higher achievement than students randomly assigned to comparison groups (Oyserman et al., 2006, 2015). Among middle school and high school students, the future identities that young people articulate predict positive academic outcomes when they include tangible strategies for success and a balance between positive futures to reach and negative futures to avoid (Oyserman et al., 2004). This foundation of theory and relevant evidence provides guidance for how future identities could be cultivated in a college environment to promote motivation and success.

In addition to showing the types of future identities that support positive student outcomes, identity-based motivation theory has also suggested that specific forms of motivation or motivational processes are likely to result from the activation of future identities. Perhaps most notably, when motivating future identities are activated, it can shape how students respond to experiences of academic difficulty. Specifically, they should become more likely to interpret challenges in completing academic tasks as a sign that a task is important and less likely to interpret challenges as a sign that an academic task is not possible for them (Smith and Oyserman, 2015; Fisher and Oyserman, 2017). As students bring to mind rich images of how their current tasks are connected to who they aim to become, difficult tasks gain a greater sense of meaning (Destin and Williams, 2020).

Another motivational process that is likely to be catalyzed by future identities is how people imagine their own financial and economic prospects. Specifically, a person’s motivating future identities may facilitate the expression of a more positive socioeconomic outlook, where they have a stronger belief that people can rise the socioeconomic hierarchy (Browman et al., 2022). This belief is consequential and especially predictive of the academic behaviors and outcomes for students who are likely to view education as a route to improve their financial security (Browman et al., 2017). Research has not, however, tested whether the controlled activation of future identities on a large scale affects these motivational processes and leads to increases in college success, particularly in a context where students face many challenges and a significant risk of failing to complete their degree.

Institutional Characteristics and the Current Studies

The vast majority of studies of psychological factors that can support college student success have been conducted at selective to highly selective colleges and universities (see Harackiewicz and Priniski, 2018). However, only a fraction of college students in the United States attend these types of institutions (Espinosa et al., 2019). Furthermore, issues of student success and retention are much more pronounced at less selective and open enrollment colleges and universities (Long, 2018; Shapiro et al., 2018). These institutions are likely to have fewer resources to invest in student support services than more selective institutions, and they are more likely to serve students who face a wider range of life challenges like working to support themselves and often their children (Espinosa et al., 2019). All of these characteristics are particularly pronounced at online universities. As a growing sector, over five million students were enrolled in some sort of online postsecondary course in the United States in 2014 (Allen and Seaman, 2016). Furthermore, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional colleges and universities have overwhelmingly relied on various forms of virtual learning. Online degree programs face significant political and academic criticism in part due to the historically low completion rates and high student loan default rates of students who attend for-profit online colleges (Cottom, 2017). Despite the challenges faced by the large number of students engaged in online education, very little research has investigated the types of supports and institutional practices that can help students to successfully complete their programs.

In the current paper, two preregistered, randomized-controlled experiments including over 3,500 participants tested whether the activation of students’ future identities is an effective strategy to support student success at a predominantly online university serving adult learners. We developed an exercise that encouraged students to think, write, and elaborate about their own motivating future identities that was embedded within existing course activities. We then evaluated the effects of carefully activating motivating future identities on relevant motivational processes, academic achievement, and degree persistence.

Based on identity-based motivation theory, our main research question was whether students randomly assigned to complete the future identity activity would show more productive responses to academic difficulty and a more positive socioeconomic outlook. We also planned to test whether the future identity activation has any positive effects on students’ grades and rates of persistence toward college completion, potentially as an indirect effect of the experimental treatment’s influence on students’ motivational processes. The online university disproportionately serves students from lower income backgrounds and racial-ethnic groups that are historically underrepresented in higher education meaning that the experiment has potential implications for broader issues of equity in education. Study hypotheses, procedures, measures, and analyses were preregistered1.

Study 1

Methods

Participants and Procedure

We developed an experimental online activity and writing exercise to incorporate within courses that undergraduate students were taking at an online university. The activity and writing exercise were designed to build from prior research and activate students’ identities in ways that support academic motivation, course success, and persistence toward college completion.

Students enrolled in several sections of two large introductory math classes participated in the study (Mean age = 32.21, SD = 8.72; 59% women, 41% men; 0.32% American Indian or Alaska Native, 2.12% Asian, 25.95% Black or African American, 0.42% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 3.81% Two or More Races, 67.37% White). Each section was randomly assigned to the treatment or control condition. During the first week of the course, students in sections randomly assigned to the treatment condition (N = 429) engaged with the experimental online module. They watched a 1-min video of a recent graduation ceremony featuring students from their university in order to provide them with an image of future academic success. Then, they responded to the following prompt designed to activate future identities. As intended, student responses to the prompt were specific and multifaceted.

“Now that you have watched a video of the University students receiving their diplomas, take a moment to actually imagine yourself on the stage at the moment when you receive your own diploma. Think about what you will have learned, the new opportunities that will be available to you, and how your life will change.

Please describe in detail the positive future that you have reached after graduating and a negative future that you avoided. Please be as specific as you can to make these futures realistic.”

Finally, participants in the treatment condition responded to the following prompt asking them to write a brief letter to their current self from the perspective of their future self describing strategies that they used to reach their future. This procedure was developed based on prior research and theory on identity-based motivation suggesting the importance of future identities that are vivid, balanced, and linked to behavioral strategies (see Oyserman et al., 2004). The prompt stated:

“In the space below, please take the perspective of this future ‘you’ and write a short letter that provides some advice to your current self as you begin your studies at University. This letter will be from the ‘you’ that is graduating in the future to the ‘you’ right now. Tell your present self about how you got to this future. Write about the challenges that you encountered as you worked through your studies, how you overcame them, and what you did to stay focused during challenging times.

Tell your current self specific things you could be doing now, during your first week at University, to help reach graduation specifically.

For example, you might write about these topics:

– Making specific times to do schoolwork.

– Balancing school and home/family responsibilities.

– Prioritizing school over other less important things.

– Using a system to keep track of deadlines.”

In the control condition (N = 613), students did not complete the experimental module during the first week of the course. Students in both conditions completed a survey containing the dependent measures during the second week of the course. We also collected important course outcomes at the end of the term.

Measures

Interpretation of Difficulty

Participants indicated their level of agreement with eight statements describing aspects of how they interpret and respond to experiences of academic difficulty that are central to identity-based motivation theory (for scale validation, see Fisher and Oyserman, 2017). Four items captured how likely students are to interpret difficulty as a sign that a task is important (sample item, “When I am working on a school task that feels difficult, it means that the task is important”; 1 = Strongly disagree, 6 = Strongly agree; M = 3.93, SD = 1.19, α = 0.88). The other four items captured how likely they are to interpret difficulty as a sign that a task is impossible (sample item, “If working on a school task feels very difficult, that type of task may not be possible for me”; M = 2.13, SD = 1.05, α = 0.86). Higher scores on the importance measure and lower scores on the impossibility measure were both indicative of stronger academic motivation. The impossibility measure in particular has been connected to future identity and is predictive of academic achievement (Destin et al., 2018).

Socioeconomic Outlook

Participants indicated their level of agreement with eight statements capturing their beliefs about the ability to change your status in society [“People can substantially change their status in society”, 1 = Strongly disagree, 6 = Strongly agree; M = 4.80, SD = 0.90 α = 0.86; for scale validation see Browman et al. (2017)]. A stronger belief in socioeconomic mobility or a more positive socioeconomic outlook has also been connected to both future identity and academic achievement (Browman et al., 2022).

Course Outcomes

At the end of the term, we collected administrative data including students’ final grades in the course (M = 72.56, SD = 32.39) and whether they successfully completed the course and enrolled in the following term (i.e., 72.46% persisted, 27.54% did not persist).

Results and Discussion

Due to the nested structure of data in Study 1 (i.e., students nested within two courses), we conducted multilevel linear and logistic regressions including a random intercept for the course students were enrolled in to test whether random assignment to the treatment group affected students’ psychological outcomes, academic achievement, and degree persistence. We did not conduct secondary analyses including covariates or analyses of possible interactions due to limited individual student demographic data availability. We also did not code qualitative data for analysis for this report. We used the lmerTest package in the statistical software R v3.6.2, which uses the Satterthwaite approximation (Kuznetsova et al., 2017). There were no significant differences between students randomly assigned to the treatment condition and the control condition on any psychological measures (ps > 0.291). Therefore, we were not able to test for indirect effects on course outcomes through student motivation.

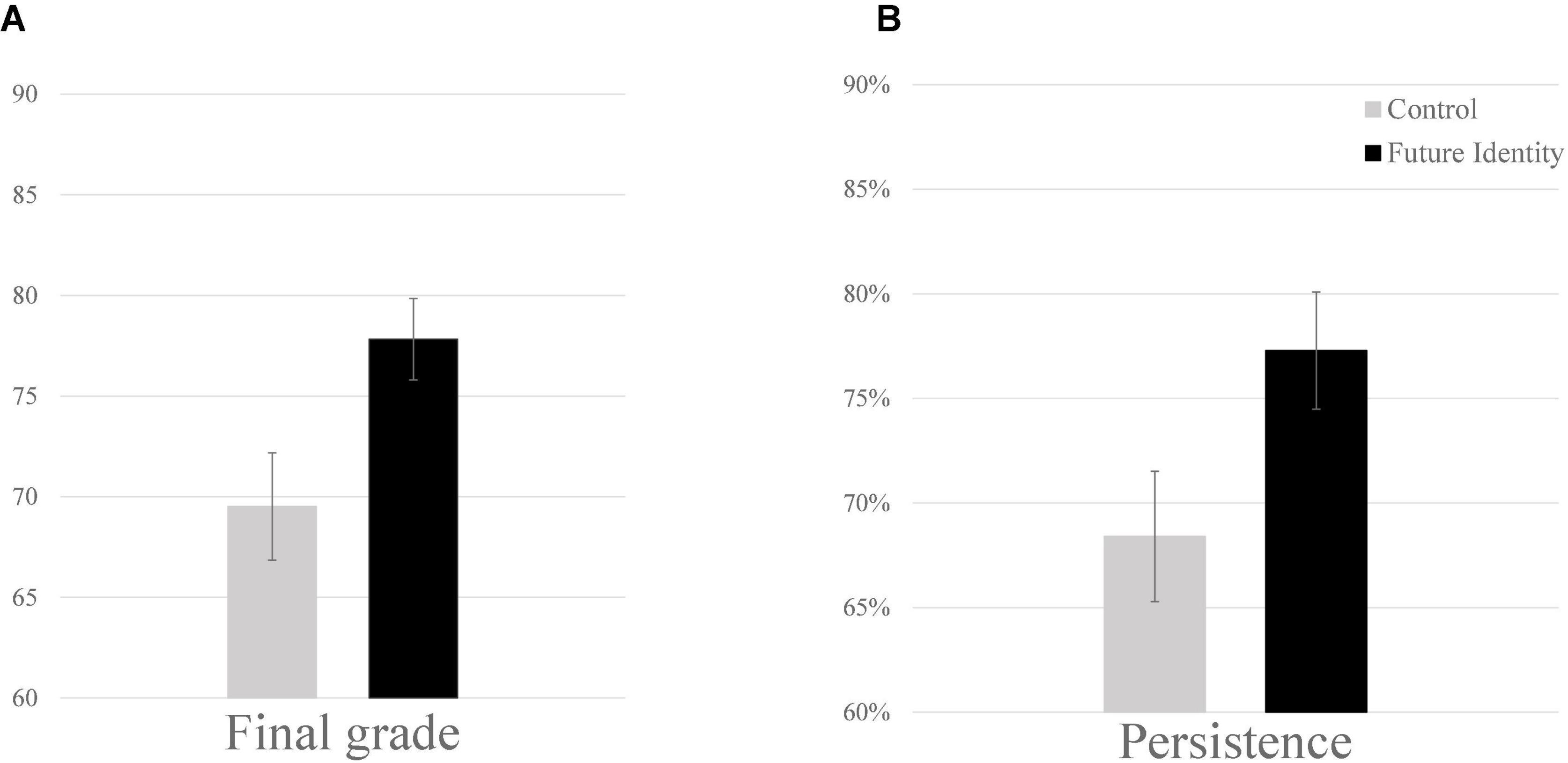

We did, however, explore direct effects of the experimental treatment on course outcomes to find a significant effect on students’ grades at the end of the course, β = 0.13, 95% CI [0.07, 0.19], SE = 0.03, t(1040) = 4.11, p < 0.001, marginal R2 = 0.02. Students randomly assigned to the future identity treatment earned final grades that were an average of eight percentage points higher (M = 77.83, SE = 2.02) than students randomly assigned to the control group (M = 69.51, SE = 2.67; see Figure 1A). There was also a significant treatment effect on students’ persistence or likelihood of completing the course and enrolling in subsequent courses toward degree completion, β = 0.10, OR = 1.59, 95% CI [1.19, 2.11], SE = 0.03, t(1040) = 3.17, p = 0.002, marginal R2 = 0.01. Students randomly assigned to the treatment condition were nine percent more likely to successfully complete the course and enroll in a subsequent course toward their degree completion (M = 77.29%, SE = 0.03) than students in the control condition (M = 68.40%, SE = 0.03; see Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Effect of future identity treatment condition on final course grades (A) and persistence toward degree completion (B) in Study 1. Figure includes predicted means and standard error bars.

The experimental online module activating students’ motivating future identities did not demonstrate the primary expected effects on student measures of motivation. There were instead significant direct effects on important course outcomes. However, in Study 1 students were randomly assigned as entire sections, which somewhat weakens the conclusions that can be drawn from the findings taken alone. Further, we expected the brief experimental activity to more directly affect specific psychological processes with potential indirect consequences for achievement and persistence. Another study is necessary to more rigorously test the experimental effects and to more carefully measure the hypothesized shift in students’ psychological processes.

Study 2

Methods

Participants and Procedure

In a second experiment, we replicated and extended the method of Study 1 with a larger sample of students from a more diverse pool of introductory courses and a stronger design to test for psychological effects of activating a future identity (mean age 31.85, SD = 8.88; 8.72; 76% women, 24% men; 1.78% American Indian or Alaska Native, 2.17% Asian, 32.97% Black or African American, 10.89% Latinx, 52.18% White). Specifically, Study 2 participants completed an initial baseline survey of the measures of psychological processes during the first week of class, which was not included in Study 1 (MImportance = 4.05, SDImportance = 1.17; MImpossibility = 2.03, SDImpossibility = 0.95; MSocio economic Outlook = 4.90, SDSoco economic Outlook = 0.81). This allowed for a more precise measurement of individual shifts in motivation that students may experience after the experimental treatment compared to their baseline. Also, in this study students were each randomly assigned at the individual rather than class level to either the same treatment condition as Study 1 during the second week of class (N = 1,167) or a control condition where they were asked to write about their previous day (N = 1,348). They then completed a questionnaire of the same motivational processes as Study 1 (MImportance = 4.03, SDImportance = 1.22; MImpossibility = 1.99, SDImpossibility = 0.92; MSocio economic Outlook = 4.86, SDSoco economic Outlook = 0.87). They also completed similar writing tasks halfway through the course. Finally, the same outcome data on course grades (M = 76.91, SD = 22.31) and persistence (57.30% persisted, 42.70% did not persist) were collected at the end of the term.

Results and Discussion

As in Study 1, based on the nested structure of the data (i.e., students nested within six courses), we conducted multilevel regressions including a random intercept for course to test the effects of random assignment on the outcomes of interest. Because Study 2 included baseline measures of motivational processes, we conducted regression analyses testing for the experimental effect of random assignment to the treatment condition on each of the motivational processes when including the baseline measure as a covariate. As in Study 1, there was no significant effect of the experimental treatment on the extent to which students interpret difficulty as importance, p = 0.403. There was, however, a significant effect of the future identity treatment on students’ interpretation of difficulty as impossibility, β = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.07, −0.01], SE = 0.02, t(2440) = −2.31, p = 0.021, marginal R2 = 0.42. There was also a significant treatment effect on students’ socioeconomic outlook, β = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.07], SE = 0.01, t(2417) = 2.73, p = 0.006, marginal R2 = 0.48. Students who were randomly assigned to the future identity condition showed significant decreases in their interpretation of difficulty as impossibility and significantly more positive trajectories of their socioeconomic outlook compared to students in the control group.

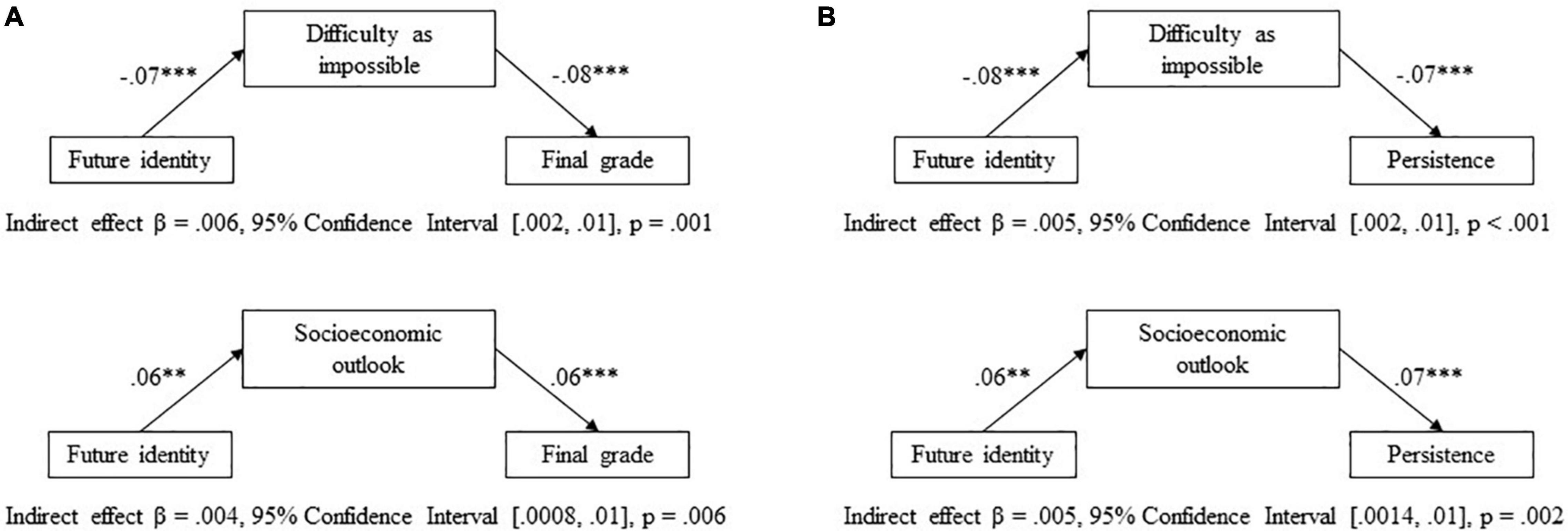

Because Study 2 did show predicted effects on motivational processes, we then conducted planned multilevel mediation tests of the potential indirect effects of the activated future identity on course outcomes through the psychological variables using 5,000 bootstrapped samples in the mediation package in R v3.6.2 (Tingley et al., 2014). The direct effects on final course outcomes were not significant, ps > 0.408. However, the multilevel mediation tests revealed that the expected indirect effects on both final grades and persistence through both motivational processes were significant (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Indirect effects of future identity treatment on final course grades (A) and persistence (B) through motivational processes in Study 2. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The more rigorous design of Study 2 provided support for the hypothesis that the experimental module activating students’ motivating future identities would affect specific motivational processes. Further the experimental effects on identity-based motivational processes were part of the specific, hypothesized indirect pathways to positive consequences for objective course outcomes over time.

General Discussion

Two studies provide evidence that a psychologically informed approach that emphasizes future identities had a range of notable positive effects on students as they pursued post-secondary education. The design of Study 1 was not able to effectively test for shifts in students’ motivational processes but did provide evidence suggesting that activating students’ future identities had positive effects on achievement and course outcomes. Study 2 provided a more refined understanding of the process by which future identities can lead to positive course outcomes. The study randomly assigned students at the individual, rather than section level, and measured changes in students’ motivation from baseline. This design revealed the positive effects of activating future identities in accordance with guidance from identity-based motivation theory on how students respond to difficulty and perceive opportunities in society. Finally, these processes showed the expected indirect, rather than direct, effects on college achievement and success in a learning environment characterized by a high risk for students of not completing their degree. The indirect pathway to positive student outcomes through motivational processes is likely to be more consistent and reliable than a direct positive effect due to its deeper connection to the established premises and existing evidence of identity-based motivation theory in addition to the stronger design of Study 2.

Activating future identities as a means to support student motivation and success is related to but distinct from several other psychological approaches, such as mindset, belonging, or utility-value (e.g., Walton and Cohen, 2011; Harackiewicz et al., 2014; Yeager et al., 2016). Instead of focusing directly on students’ identities, these other approaches emphasize their beliefs about ability, thoughts about the social context, or how school tasks can be useful. Future research remains necessary to determine how institutions might pair an identity-based approach with other psychological strategies and institutional resources to lead to even stronger positive effects on student outcomes. This novel evidence, however, advances the understanding of how a focus on future identity centers an aspect of students’ conceptions of themselves to cultivate an individually relevant source of motivation allowing people to derive persistence from the specific circumstances of their lives.

In addition to the implications for psychological theory, the studies also have implications for educational research and practice. The findings suggest that studies aiming to capture the array of factors contributing to college completion should consider how broader educational policies and resources affect students’ beliefs about themselves and their futures as a potential pathway to academic outcomes. At an institutional level, professional development opportunities would benefit from including guidance on how educators and other higher education professionals can effectively help students to recognize, explore, and develop meaningfully motivating future identities.

The main limitations of the research are the design flaws of Study 1, which did not allow for effective tests on psychological processes or indirect effects on student outcomes. The studies also did not evaluate how factors such as timing may play a role or the potential effects of future identities on other learning and well-being outcomes. However, it is consequential to have uncovered evidence for the hypothesized motivational processes that are activated by future identities that lead to student outcomes. The study that measured changes in individual students’ responses to academic challenges and beliefs about socioeconomic opportunity demonstrated the key role of guiding students to elaborate on their future identities.

The approach of the current experimental demonstration should not be interpreted as an intervention to uniformly apply from one educational context to another. Despite the large sample size and attention to an understudied type of university reaching large numbers of students, the materials were developed for a particular institutional context and student body. The findings suggest that educators and institutions more broadly will benefit from meaningfully engaging and supporting students’ future identities in ways that are sustained and authentic to their learning environments. Whether through advising, course materials, institutional programs, or a variety of other possible approaches, providing students with opportunities to consider the connections between their school tasks and who they might become helps them to sustain momentum through life’s many challenges.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article may be made available by the authors upon request, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Kaplan University/Purdue University Global Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MD conceptualized the research, coordinated data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. DS participated in data analysis and provided manuscript feedback. MB coordinated data collection and provided manuscript feedback. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Allen, I. E., and Seaman, J. (2016). Online report card: Tracking Online Education in the United States. Boston, MA: Babson Survey Research Group.

Allensworth, E. M., and Clark, K. (2020). High school GPAs and ACT scores as predictors of college completion: xamining assumptions about consistency across high schools. Educ. Res. 49, 198–211. doi: 10.3102/0013189X20902110

Browman, A. S., Destin, M., Carswell, K. L., and Svoboda, R. C. (2017). Perceptions of socioeconomic mobility influence academic persistence among low socioeconomic status students. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 72, 45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.03.006

Browman, A. S., Svoboda, R. C., and Destin, M. (2022). A belief in socioeconomic mobility promotes the development of academically motivating identities among low-socioeconomic status youth. Self Identity 21, 42–60. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2019.1664624

Cottom, T. M. (2017). Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of for-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. New York, NY: The New Press.

Destin, M., Castillo, C., and Meissner, L. (2018). A field experiment demonstrates near peer mentorship as an effective support for student persistence. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 40, 269–278. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2018.1485101

Destin, M., and Williams, J. L. (2020). The connection between student identities and outcomes related to academic persistence. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2, 437–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-040920-042107

Elliott, W., and Lewis, M. K. (2015). The Real College Debt Crisis: How Student Borrowing Threatens Financial Well-Being and Erodes the American Dream. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Espinosa, L. L., Turk, J. M., Taylor, M., and Chessman, H. M. (2019). Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Fisher, O., and Oyserman, D. (2017). Assessing interpretations of experienced ease and difficulty as motivational constructs. Motiv. Sci. 3, 133–163. doi: 10.1037/mot0000055

Goldrick-Rab, S., Kelchen, R., Harris, D. N., and Benson, J. (2016). Reducing income inequality in educational attainment: experimental evidence on the impact of financial aid on college completion. Am. J. Sociol. 121, 1762–1817. doi: 10.1086/685442

Harackiewicz, J. M., Canning, E. A., Tibbetts, Y., Giffen, C. J., Blair, S. S., Rouse, D. I., et al. (2014). Closing the social class achievement gap for first-generation students in undergraduate biology. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 375–389. doi: 10.1037/a0034679

Harackiewicz, J. M., and Priniski, S. J. (2018). Improving student outcomes in higher education: the science of targeted intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69, 409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011725

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., and Christensen, R. H. (2017). lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26.

Long, B. T. (2018). The College Completion Landscape: Trends, Challenges, and Why it Matters (Elevating College Completion). Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

National Center for Education Statistics (2021). Fall Enrollment Component (Provisional Data). The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Nurra, C., and Oyserman, D. (2018). From future self to current action: an identity-based motivation perspective. Self Identity 17, 343–364. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1375003

Oyserman, D. (2015). Pathways to Success through Identity-Based Motivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., Terry, K., and Hart-Johnson, T. (2004). Possible selves as roadmaps. J. Res. Pers. 38, 130–149. doi: 10.1016/s0092-6566(03)00057-6

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., and Terry, K. (2006). Possible selves and academic outcomes: How and when possible selves impel action. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 188–204. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.188

Oyserman, D., Destin, M., and Novin, S. (2015). The context-sensitive future self: possible selves motivate in context, not otherwise. Self Identity 14, 173–188. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2014.965733

Oyserman, D., and Destin, M. (2010). Identity-based motivation: implications for intervention. Couns. Psychol. 38, 1001–1043. doi: 10.1177/0011000010374775

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P. K., Bhimdiwala, A., and Wilson, S. E. (2018). Completing College: A National View of Student Completion Rates-Fall 2012 Cohort (Signature Report No. 16). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse.

Smith, G. C., and Oyserman, D. (2015). Just not worth my time? Experienced difficulty and time investment. Soc. Cogn. 33, 85–103. doi: 10.1521/soco.2015.33.2.1

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., and Imai, K. (2014). Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 59, 1–38. doi: 10.1111/biom.12248

Titus, M. A. (2006). No college student left behind: the influence of financial aspects of a state’s higher education policy on college completion. Rev. High. Educ. 29, 293–317. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2006.0018

Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science 331, 1447–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364

Keywords: motivation, achievement, identity, higher education, goals

Citation: Destin M, Silverman DM and Braslow MD (2022) Future Identity as a Support for College Motivation and Success. Front. Educ. 7:901897. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.901897

Received: 22 March 2022; Accepted: 04 May 2022;

Published: 24 May 2022.

Edited by:

Joseph Madaus, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Michael N. Faggella-Luby, Texas Christian University, United StatesNicholas Gelbar, University of Connecticut, United States

Copyright © 2022 Destin, Silverman and Braslow. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mesmin Destin, bS1kZXN0aW5Abm9ydGh3ZXN0ZXJuLmVkdQ==

Mesmin Destin

Mesmin Destin David M. Silverman2

David M. Silverman2