- Department of Health, Physical Education and Exercise Science, Norfolk State University, Norfolk, VA, United States

With the large increase in international doctorates at higher education institutions in the United States, little attention is being paid to former doctoral students’ cross-cultural experiences during their reentry to their home countries. Based on the re-acculturation theory as a conceptual framework, this qualitative inquiry aimed to explore how study participants perceive their reentry. The findings were explained using six subthemes: (a) the renewal process, (b) ambivalence of reentry, (c) homing instinct, (d) environmental context, (e) midpoint of repatriation, and (f) different research atmospheres. The findings reveal the importance of doctorates’ flexibility to cope with each country’s academic atmosphere and respect academic cultural differences. The findings provide insight into the challenges that international kinesiology professionals face during their reentry and how they resolve these difficulties for readjustment to the academic atmosphere of their home countries.

1. Introduction

From 2019 to 2020, it is estimated that 6% of students in higher education institutions in the U.S. were international students (Dennis, 2020; Institute of International Education, 2020). Approximately 20% of international students choose their major in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields or business and management schools. There has been an increase in international students choosing other areas of study too. It is estimated that approximately 8% of international students are in the areas of social, physical, or life sciences (Institute of International Education, 2020). Among them, it is estimated that over 60% came from Asian countries (China: 35%; India: 18%; Republic of Korea: 4%; Taiwan: 2%; Vietnam: 2%; Japan: 2%; Institute of International Education, 2020). With the globalization of the field of kinesiology, there are a significant number of doctoral students in the U.S. After earning a doctoral degree, international kinesiology professionals either continue their careers in the U.S. or return to their home countries. There are diverse reasons for going back to their home countries, such as career development, job opportunities, family issues, a sense of belonging, and homesickness (Shen and Herr, 2004; Lee and Kim, 2010; Bozionelos et al., 2015).

There is a plethora of research focusing on international students and their cross-cultural adjustments in the U.S. The findings commonly indicate that international students are likely to encounter multifaceted challenges in their social relations, cultural atmosphere, language barriers, and academic burdens (Gebhard, 2012; Rienties et al., 2012; Mesidor and Sly, 2016). While several international doctorates return to their home country for periods during their career development as professionals in the academic field, there is limited research regarding the readjustment of these doctoral degree holders. Through doctoral training at graduate school, international doctorates gain their research skillset and expertise in their specialization. While contributing to the area of expertise, they are likely to face difficulties in a tight job market. In the same context, during their reentry, kinesiology professionals are likely to encounter inter-cultural experiences relating to the academic atmosphere embedded in the culture of their home country. Readjustment is at the top of the agenda to attain better job opportunities and socialization with colleagues (Andrianto et al., 2018).

The literature has described diverse factors that impact reentry. Depending on the length of stay abroad, age, and gender, the sojourner’s satisfaction and reentry experience will be differently perceived (Spencer-Rodgers, 2000; Szkudlarek, 2010). For an amicable reentry, the readiness and situational understanding of the returnee are regarded as important qualities (MacDonald and Arthur, 2003). A literature review by Szkudlarek (2010) that described reentry and adjustment noted: (1) older individuals show lower levels of psychological depression and social difficulties upon reentry (Cox, 2004; Hyder and Lövblad, 2007); (2) personality traits such as self-efficacy are regarded as important factors influencing reentry adjustment (Martin and Harrell, 2004; Eugenia Sánchez Vidal et al., 2007); (3) depending on the individual’s working condition and family environment, the years spent abroad could be a significant variable on adjustment during possible reentry (Szkudlarek, 2010); and (4) there were inconsistent results in previous studies between gender and reentry (Brabant et al., 1990; Sussman, 2001; MacDonald and Arthur, 2003).

Both the adjustment and re-entry of international student sojourners face diverse challenges. There are unique characteristics in the reentry of doctoral degree holders, with issues that hang upon achieving the degree by staying abroad. This study sought to examine the reentry of the study participants more closely. Many kinesiology professionals have returned to their home countries to develop their careers in academia. Kinesiology professionals could conciliate themselves with their intercultural academic experiences of both countries. However, no known previous studies on kinesiology professionals and their processes of reentry have been conducted. Thus, the aim of this phenomenological study was to explore the reentry of Asian kinesiology faculty professionals after obtaining a doctoral degree at public research-intensive universities in the U.S. It focused on understanding the common experience (challenges and strategies) of Asian kinesiology professionals during their transition period.

1.1. Theoretical framework and purpose

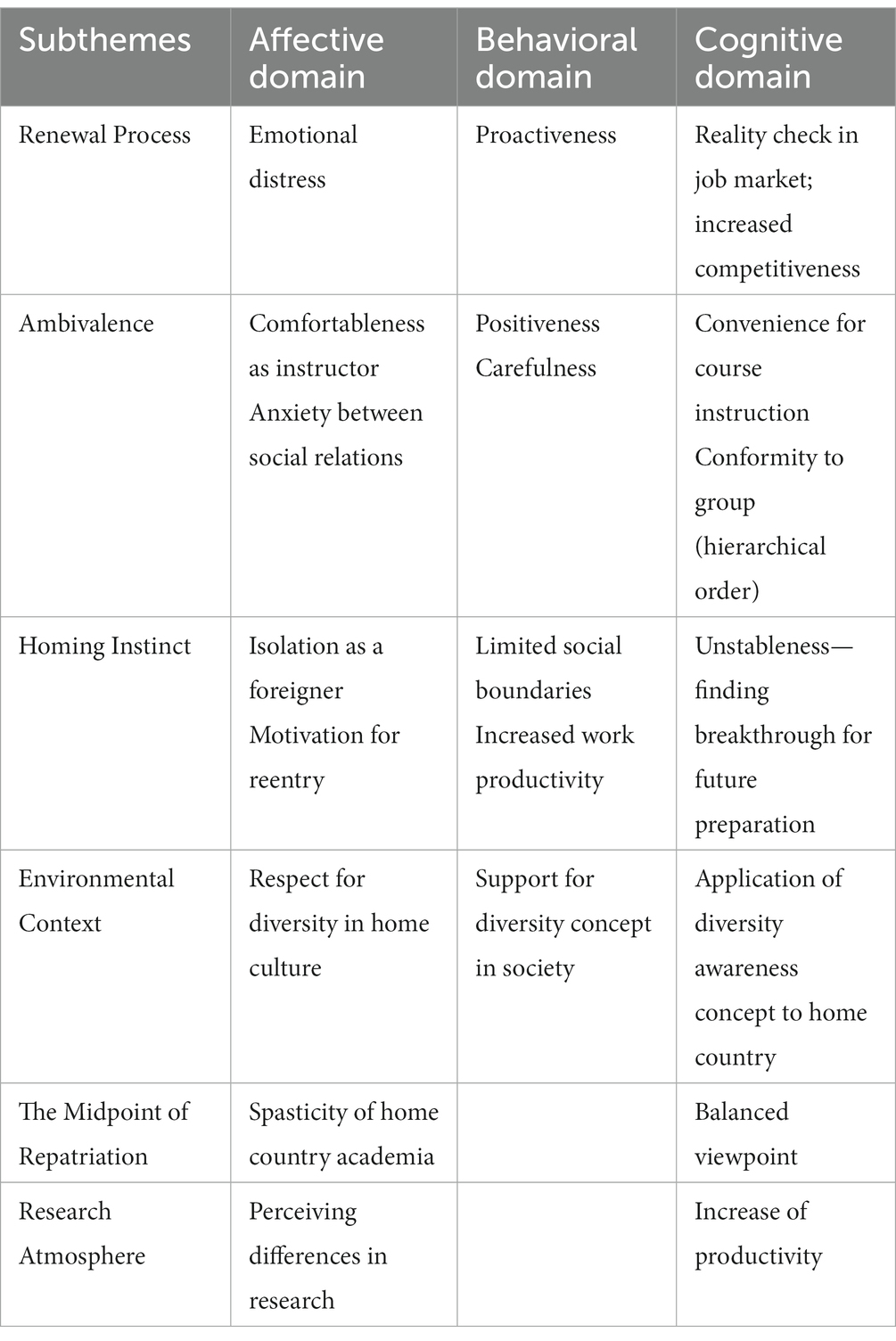

Employing “re-acculturation” as a theoretical framework, the present study explored the reentry of Asian kinesiology professionals who returned to their home country. “Re-acculturation” is rooted in the theoretical framework of “acculturation.” “Acculturation” refers to “the process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between cultural groups and their individual members” (Berry, 2017, p 15) [20]. As noted by Szkudlarek (2010), empirical studies on acculturation have been addressed in “affective,” “behavioral,” and “cognitive” aspects—this approach is beneficial to examine “reverse culture shock” and “re-adjustment” during reentry (Zhou, 2015). Critics have stated that previous acculturation research explored “culture shock” based on the medical perspective; thus, the experience of international students tended to focus on pessimistic viewpoints as a victim of pathology (Zhou, 2015). However, the current study has extended the previous research of acculturation by exploring the two-way process. It explored acculturation into a new culture (i.e., from the home country to the U.S. for the completion of a doctoral degree) and re-acculturation (i.e., the cross-cultural experience of those who came back to their home country after staying for a certain period in the U.S. for their doctoral degree and/or professional career). To summarize, using the “re-acculturation” framework, the reentry of the study participants was explored for more comprehensive and extended periods: the participants were introduced into a new culture for their doctoral degree and then reintroduced into their home culture for their professional career. The aim of the current study was to explore the common experience of the reentry of these Asian kinesiology faculty professionals. The followings are sub-questions: “What are the difficulties (e.g., cross-cultural experiences) experienced by Asian kinesiology professionals during their reentry?,” “How can Asian kinesiology professionals resolve these difficulties during their reentry?,” and “Which contextual factors can be explained for the reentry experience of Asian kinesiology professionals during their transition?”

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Methods and participants

The aim of this study was to understand the common experience (e.g., challenges and strategies) of Asian kinesiology professionals during their transition period upon reentry. The participants were five kinesiology professionals who completed their doctoral degrees in the U.S. and then reentered the Republic of Korea. There are differences between the participants regarding their length of stay at their home country and the U.S.; however, they all finished their schooling, including an undergraduate program, in the field of kinesiology in their home countries. The length of stay in the U.S. (ranging from 8 to 17 years) and the number of years since reentry to Korea (ranging from 4 to 15 years) varied depending on the participant. The study participants were limited to faculties in higher education institutions in Korea, as this study explored their academic roles for research and teaching roles. To achieve a balanced view, this study recruited both men (n = 3) and women (n = 3). Specifically, it sought to explore their cross-cultural and doctoral degree experience in U.S. higher education institutions, how they made the transition, and their readjustment to the academic field in their home country.

2.2. Sampling method

The current study used the purposive sampling method. This strategy is non-random. By intentionally choosing study participants based on their qualifications for research aims, purposive sampling methods allow researchers to recruit study participants (Robinson, 2014). For this study, the research participants were recruited through a professional network.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

Prior to the interviews, the participants were required to complete and then submit consent forms directly or by email. After the study obtained approval from the IRB office, interviews were set up by arranging a specific time and day for the video conference or in-person interviews. Prior to the interviews, a demographic questionnaire was completed by the study participants, which took approximately 15 min. Each participant had three sessions of interviews lasting from 45 min to 1 h. They had up to 2 h for the interview (3 sessions x 40 min) in semi-structured interviews, 10 min for demographic questionnaires, and 30 min for the member checking of written documents from the interview data.

Thematic analysis allowed the researcher to identify the common themes from the interview dataset of the multiple participants. Common themes were identified by reviewing the responses of all the study participants (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Using thematic analysis, the researcher explored the common reentry and cross-cultural experience of the kinesiology faculty who returned to their home country after achieving a doctoral degree at U.S. higher education institutions.

2.4. Trustworthiness

For rigor of the research process, multiple strategies were used in this study: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Lincoln et al., 1985). For credibility, video-clipped interviews based on online meetings and written transcripts were used. The data analysis and interpretations were checked through member checking on written scripts. The researcher reviewed the data to prevent any disagreement. For peer debriefing, a qualified researcher who specialized in our topic area provided corrective feedback and critical information as an external check. The researcher described comprehensive factors connected to the background and environment for transferability. By clearly describing the research procedures and focusing on original data, the researcher tried to assure dependability and confirmability (Patton, 2015).

3. Results

This phenomenological inquiry explored the common experience of the reentry of kinesiology faculty professionals to the Republic of Korea. The participants had common features, and the findings have been explained through six subthemes that are inter-related: (a) the renewal process, (b) ambivalence of reentry, (c) homing instinct, (d) environmental context, (e) midpoint of repatriation, and (f) different research atmospheres.

3.1. Theme 1: renewal process

Instead of building networks and interpersonal relationships, time elapsed and the participants’ roles changed to that of professionals in academia. Due to being absent for several years, they made efforts to re-establish their professional careers after repatriation, for they had already had their own networks in the field. However, after reentry from studying abroad, they needed to be proactive in gaining stable job positions at universities. Kara explained that she obtained support for data collection for research work through her connections, which was useful for finding public schools and contacting professionals. However, she was active in seeking to achieve instructor positions at multiple institutions before she was hired for a tenured faculty position. Kara explained this as follows:

The network was helpful, but I needed to be active to find places to work as an instructor. Nobody could help me with this. Ok, maybe others can be benefitted more throughout their networks. But what I am feeling was that it was very competitive for significant upside. I mean the most ever-important thing was whether I was qualified and enough competitive for any positions.

Another participant, Bitna, described a xenophobic culture of academia during the reentry. For instance, she described that this was because of her absences for a certain time when studying abroad, and it was a natural result of other professionals who had worked and stayed in the same place for a long time being at an advantage. Moreover, due to fierce competition in the job market, requesting help for work was a sensitive issue. The topic of work projects and research must be conducted as a reciprocal arrangement in advance:

There were not many available jobs in a year. Only there were three positions when I searched universities to apply for tenure track positions. And it is a small academic world. Everyone knows each other. I needed to be careful whenever I met people in the same field except for very close few friends. Everything was competition based, I felt.

All the participants described that they were required to apply to many institutions to gain tenured faculty positions for several years. Regardless of their length of stay in the U.S. or job status, several years were consumed by tenured positions in Korea. Not only did the participants (Kara, Meta, and Choo) return to Korea after achieving a doctoral degree in the U.S., but two participants (Baemin and Bitna) who were former assistant professors in the U.S. before coming to Korea explained that it took several attempts over years before they were hired in Korea.

3.2. Theme 2: ambivalence of reentry

The participants explained that there were two sides to their readjustment to their home country. They felt more comfortable instructing students in their classes at universities after reentry. Both the cultural aspects (e.g., the hierarchical order between faculty and students) and educational system of the home country were already ingrained in their psyche. Baemin explained that “it was more comfortable to manage classes, and I felt more comfortable to find places for practical experience of students for my APE course. You know, we are all interrelated, knowing each other, where I should contact in our country. I needed to contact just once to find a disability sport event and its approval for my students.” Other participants (Bitna and Jyfi) said that they tried to get professional work. However, they got more chances in professional development careers such as advisory committees for conferences or organizations compared to when they were in the U.S. They shared difficult experiences during their readjustment after reentry. Several respondents described the hierarchical nature and community sentiment of their academic atmosphere. For professional reentry and adjustment, the participants kept proactive and positive attitudes toward social relations and networking. They tried not to draw attention to themselves and to mind their personal behavior. Baemin explained this as follows:

Participation in academic conferences to serve the specific role was so important. I could meet many colleagues and have many conversations. I recognized that this was as important as writing manuscripts or teaching classes. The get-togethers were a part of my job. I tried not to be absent from going to dinner after the conference. We cannot ignore social interactions by attending both formal and informal meetings and gatherings. Even I could hear many interesting topics about our field, and this satisfied my curiosity sometimes.

The full-time, tenured, assistant professor position was one of the most mentioned terms by the interview participants. Their foremost priority was getting a stable position at a university for their entire duration during the reentry. By engaging in diverse settings such as formal and informal meetings through a professional conference, the reentry professionals sought to advise many unspecified persons in the same field. Some of them had connections with their previous advisors and professors, which allowed them to recognize what was occurring in the field. The participants pointed out both the perks and challenges during their reentry. The returnees were required to search for the best alternatives to dealing with many challenges during their reentry. Difficulties were unavoidable aspects they had to face, and they showed positivity in trying to find a breakthrough.

3.3. Theme 3: the homing instinct

There were different reasons to return home after earning a doctorate in the U.S. It depended on the study participants’ situations. They explained that they pondered continuously on whether to settle down in the U.S and develop their careers or return to their homeland. Bitna and Kara both expressed that getting a stable job position was tough and required many qualifications. Even if they were hired in the U.S. first, the tenure system and visa status (such as being a green card holder) created numerous challenges for the international faculty. During those processes, they perceived that they did not have job security and prepared for many scenarios. Beyond their working or job status in the U.S., there were diverse factors to consider, such as family or friends, cultural dissonance, and language difficulties that were important considerations when deciding on their reentry. Staying away from their home country made participants feel homesick, but they adjusted over time. However, they occasionally returned to square one, going back and forth. Meta expressed what he felt between his adjustment in the U.S. and homesickness:

I felt lonely and isolated for the first time. It was stressful, but I could adjust over the years and thought that I was ok. But I felt a sudden surge of homesickness sometimes. There’s no help for it. Anyways, it is tough to live in a foreign country. Of course, it is not easy and stressful to live in my home country, but maybe I would not feel like I am too isolated living in a different country. Also, I judged that I could find many nice concepts about my field if I come back.

Some participants explained that they had few social relationships. Tara described such pros and cons as follows:

Living in the U.S. will be advantageous if I marry and have children. Especially, the educational system is the best than any other country, I believe. Also, I could focus on my life more. You know, there are lots of things to care about if I live in my home country. But whenever I ate my meal alone, I worried about my future. I get back from school and home only usually. I always come and do this. I burst out laughing at my own things, sometimes, like, feeling what am I doing. I think deciding on reentry depends on the matter of choice and personal situation.

Other participants indicated their concern about their research productivity at an international academic faculty role, such as Baemin:

Ok, I focused on my own works without any social relations for a long time. Nevertheless, research productivity was the same. I knew it takes time to publish articles for my research works. Moreover, English as a second language, this was a headache. It was getting better, but also international students in academia should not blame this. Sometimes, it made me somewhat skeptical and pessimistic, though.

The participants showed competence and enthusiasm about their careers. They were interested in making contributions to their academic field, and their reentry was preceded by months or years of speculation. Furthermore, until the participants were hired as full-time faculty members, they went through thorny paths. They expressed that working as kinesiology professionals in their home country created great motivation and personal satisfaction. Two participants expressed that when their close colleagues in their home country seemed to conduct meaningful work for their field and society, they envied them and were motivated to think about reentry more deeply.

3.4. Theme 4: environmental context

Bitna, Kara, and Jyfi indicated that learning with respect to diversity awareness was somewhat important for their roles as faculty members at higher education institutions in their home country. Defining diversity would be different due to all the differences between the U.S. and Korea. However, they explained that it is worth discovering how this definition of diversity awareness matched the home country and kinesiology field. Jyfi explained that Korea is becoming more diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, minorities, and sexual orientations:

Society is changing, but people in the society is somewhat biased and conservative to discuss about differences still. I strongly believe we need to transfer diversity awareness in some ways; this would be more important as time goes by. We could take the diversity awareness concept more deeply and discuss it more seriously.

Two participants explained the safe environment of their home country; Bitna said, “there is at least no gun violence in Korea. Of course, we all need to be careful, especially at late night, but I felt more comfortable when I fished my works at late night and came home.” Jyfi shared a story about the invisible violence of racism in Korea. Racism is a sensitive social issue in the U.S, but as much as it is sensitive, it is quite common and frequently occurs in U.S. society:

Well, I experienced some invisible discrimination, which made me to guess it was some sort of racism. After coming back to my home country, at least I did not experience this kind of issues. Free for it. Ironically, I came to think about racism issues in Korea society in reverse ways, contrarian. There are a lot and even much more severe, I think. I never thought of racism issues of Korea before. I know this is very broad category; I think our profession need to establish and discuss about this topic more seriously in more sophisticated manners…I mean, kind of respect about others.

Similarly, Baemin shared what he recognized about social change in terms of diversity awareness:

We are transforming into a multicultural community in terms of ethnicity, race, and LGBTQ. For instance, you will see a lot of international people in the city than before. Even if you go to suburban areas, there are much more than before. There is a greater number of people who have married foreign women from other Asian countries. This means that you are related to this phenomenon if you will get a job in a suburban area, as an instance. All aspects are inter-related, and this should not be underestimated.

Korea is a homogeneous country, and citizens predominantly belong to one ethnic race and use one language, which frequently leads to the stigmatization of individual differences. Based on their intercultural experiences, the participants were aware of the importance of diversity and the need to establish the concept. Another participant, Choo, shared his experience of his home culture regarding gender differences, as there were many more men in academia. The gender ratios of the faculty in the universities are heavily biased in the kinesiology field. The participants (Choo, Meta, Kara, and Tara) believed that this is not due to gender advantages or disadvantages; however, it was a surprising experience to them at first. One participant (Baemin) described that the gender imbalance in academia reduced variety in terms of diversity awareness, so he claimed that the role of women faculty members in academia is crucial.

3.5. Midpoint of repatriation

It was critical for the study participants to strike the right balance and gain desirable outcomes. The participants described that they were in the midst of familiarization with academia in their home country and the new environment, which enabled them to learn two different perspectives. They all experienced their home culture before studying higher degrees in the U.S., meaning they changed, whether consciously or not, in terms of their professional identity in academia as researchers and educators. For instance, they were familiar with the prescriptive methods of teaching in their home culture. However, the participants described that they became more interactive with individuals in their classes and professional conferences, having slightly altered their method of communication throughout their doctoral training in the U.S. Meta described this as follows:

It is changing, but still, academia is conservative and authoritative. I was careful to make my voice during professional meetings in conference. Sometimes, even I judged that I needed to be quiet and follow implicit consent. I think this is more about cultural atmosphere.

The participants shared that they were careful to avoid any conflicting values, attitudes, and behavioral norms. For instance, they hoped to make the academic atmosphere of their home country a place for more sound discussions. Baemin expressed that it was not the same atmosphere, in terms of the culture of discussion, when he had classes and instructed students at university or attended a conference for research projects. He indicated that he came to change this atmosphere to a more active role after experiencing doctoral training in the U.S:

When I reminded, first time it was somewhat hard for me to engage in discussions during doctoral program courses or any conference and forum time. Of course, I had language difficulty as an international doctoral student, but I felt it was more about culture sometimes. I mean, I was not used to have chances to debate some topic. Doctoral program experience made me to do for this so many times, and then I get used to it little by little.

Moreover, several participants explained that participating in the conferences of their home country was somewhat different compared to the academic experience of doctoral training in the U.S. One participant, Jyfi, described it as follows:

These days, many procedures for research, academic works have strict rules and criteria at both countries. Just I felt the whole atmosphere is basically different in terms of culture. Academia culture is a part of culture. So, when I go to a conference, I need to think about the hierarchical order between professors. Everyone know who you are and what you do.

Other participants shared that outward appearances such as formal attire and extreme politeness were important as implicit consent among people in their home country. Thus, the presentation style of academic works in a conference setting made them somewhat uncomfortable and feel slightly nervous. Meta shared one episode regarding such outwards appearances:

There was a dress code for the conference. I needed to wear a lounge suit. One of my close colleagues he is my alumni who completed all the higher degrees in Korea explained to me that the conference is a dignified place to present research works and its findings. I argued with my friend and said to him to wear a lounge suit that I wear] when I collect and analyze data in the lab to go to that dignified place to report the findings of research. We just laugh about it though.

The participants perceived a need for transferability of what they experienced during their doctoral training in the U.S. Tara explained, “I needed to critically reflect my learning from doctoral training in the U.S that is apposite to the case of Korea.” She remembered that a sense of flexibility was key to bridging what she learned from both cultures. The participants indicated that their students in Korea were more accustomed to command-style instructions. To lead potentials and improve academic learning for undergraduate students, the participants shared strategies that they used in their classes. Kara described that she provided a routine for her students, firstly through lectures and class materials and then by introducing them to practical learning of the content by assigning in-class tasks. Another participant, Baemin, explained that he could observe different class atmospheres between the home culture and U.S. doctoral training. For instance, he was familiar with teacher-directed styles when he was a former student in his home culture; however, he felt that he needed to enhance student learning through more proactive class modes, such as in-class activities and discussions:

Ok, just learning about any type of disability through contents were insufficient for my students. I wanted them to have more practical learning. Of course, I learned through both lectures and class activities when I was in undergraduate. However, I think there should be more practical learning opportunities and student-centered activities in my courses, which would differ compared to my undergraduate experience.

Another participant, Choo, described his feelings when instructing many students:

All right, mostly it was fine. But many of my students were inactive and did nothing without my guidance during class, maybe due to their previous experience at schools and our cultural atmosphere. So, often I gave a kind of leadership role for student in rotation. For instance, I made them to present about developmental disability and implications for physical activity. I made them to do more showing demonstration and instruction in front of others. I made them to survey about practitioners in the field, asking what they really want to do after graduation. So, many different ideas depicting how I fostered them. Anyhow, I mean I tried to encourage my students to advocate and express themselves. I knew those challenges because I was here, and I also experienced a different culture, which was never easy.

Both participants pointed out that they wanted to change their students to become more accountable while fostering leadership and independence for their classes. To enhance their students’ pedagogical learning in APE courses, the participants perceived that their students should overcome their cultural behavior and attitudes for better academic achievement in classes.

3.6. Different research atmosphere

Higher education institutions in Korea and the U.S. require different expectations from professionals in the field in terms of scholar work and productivity. The previous experience from both cultures were huge assets for the professional development and identity of the study participants. During their reentry, they were required to grasp the present status of academia in their home country and its expectations. As an example, several participants explained that they focused on enhancing their productivity in terms of research work. They commonly indicated that conceptual papers and/or practical writing were not as important as original research. Rather than focusing on practical teaching and learning, they needed to yield publications on research works before being hired. Meta gave an example of this:

I really focused to publish more articles based on research because there is a high expectation when applying for any tenured faculty position. I believe we all know the significance of teaching and learning for undergraduate students in universities; however, it made many job seekers heavily focusing on research productivity.

For a certain period, Choo focused highly on research productivity to be qualified to apply for a faculty position. At the same time, the quality of the journal based on its category and impact factor was an important consideration when submitting research articles. This was a particularly good or bad experience in that the study participants indicated how they enhanced their understanding and skillsets for research in diverse ways. They expressed that they were satisfied with their research productivity. Baemin said:

Over the years, various attempts with colleges have been produced research projects. Relatively, it was smooth and no blockages for my research works. For instance, we also have our own IRB system, which is simpler and easy to process, like the U.S. higher education institutions. But my IRB in the U.S. required lots of protocols as well as took a certain more time, like about one month to several months.

Tara also explained that it was beneficial to conduct her research work in her home country because there are no language difficulties, and it is easy to establish rapport based on a bond of sympathy in terms of cultural views. Other participants (Tara and Bitna) explained how many topics came into their heads based on what they experienced in Korean society and their U.S. doctoral training. Tara described this as follows:

I was born and grew up here. I worked as an instructor in an adapted physical education class. I know the school system. Just everything; I can make rapport with parents of a child with disabilities in the field. Kind of related were easily made, so I got assistance from related personnel and stakeholders for my works whether it is related to research or field-related works quickly.

The kinesiology professionals in this study indicated that academia has a high criterion for research work, requiring different qualifications. During their reentry, they needed to use different strategies to increase their productivity and were inspired by their intercultural experience of academia, allowing them to set up their research work in their home country (Table 1).

4. Discussion and limitation

To explore the reentry of academic professionals in the field of kinesiology who earned their doctoral degree at U.S. higher education institutions, this qualitative research focused on the voice of faculty members in higher education in the Republic of Korea. To interpret these findings, the authors of the current study extended the findings of previous studies. Furthermore, the findings were connected to the re-acculturation theory, which is the theoretical framework of this study. The reentry of kinesiology professionals is described predominantly in relation to academia. The findings have two main focuses: academic professional identity and cross-cultural experience. The participants in this study perceived their intercultural academia experiences and reentry in terms of having to endure the pains of short-term growth to achieve long-term gains for their faculty careers and personal development. They also indicated that there were difficulties and triumphs relating to their reentry and adjustment. With a basis of the key features of the re-acculturation theory (i.e., (a) affective, (b) cognitive, and (c) behavioral aspects), there is a need to examine the reentry of kinesiology professionals.

To summarize the findings in connection to the re-acculturation theory, the priority of the participants was to secure a stable work position in academia. They perceived issues during reentry, which yielded difficulties and emotional distress. However, they had to take care of their interpersonal relations and professional career development in the field. This worked as a momentum for the participants to be proactive and positive. Thus, they tried to acclimatize themselves to the academic culture of their home country. Furthermore, they tried to increase their work productivity in terms of research, and their willingness to contribute to the field acted as a facilitator to transfer their learning and knowledge to the instruction of their students. This inspired the participants to create diverse interests for planning research in their field.

The study participants indicated that they required a new creation process for their professional career. Their work benefitted from their previous network of advisors and alumni in the field, such as for finding a research site. However, the participants pointed out that their readiness and qualifications in the job market were the most important factors. A highly competitive job market created continuous trials and fails until they gained stable tenured faculty positions. During their reentry, they felt some sort of disconnection and boundaries attributed to their years of absence when studying abroad and battling for work. There is no research on the reentry of kinesiology professionals. However, this study could extend the previous research regarding the cross-cultural experiences of reentry professionals in other areas of study. The findings were consistent with previous literature that discussed the difficulties of reentry professionals in Asian countries in terms of interpersonal relations and cultural readjustment (Hsiao, 2011; Jung et al., 2013; Ko, 2019). Particularly, the hierarchical order and cultural aspects in the field had acted as important components for the participants. They followed conformity to the academic group, of which there were many examples from their responses. For example, they would try to minimize their voices where possible during professional meetings, and though there was no implicit dress code for academia, they would nonetheless feel pressure to care about their appearance and wear formalwear. The organizational culture of Korea is embedded in Confucianism, which incorporates beliefs against the individualism that the participants experienced when studying abroad (Ko, 2019). Thus, for instance, upon their reentry, rather than employing prescriptive methods of teaching in student teaching and research work, the participants reflected on how they could lead their students’ potential through active communication and interactions. They clarified that understanding such a cultural atmosphere is important for returnees to avoid making any reckless decisions. Indeed, cross-cultural experiences in academia and living abroad allowed the participants to learn different perspectives. Regarding the concept of diversity, previous studies described a broadened worldview for reentry professionals. The participants of this study emphasized the need for adaptation regarding diversity awareness concepts in Korean higher education.

The previous research showed mixed findings on the differences between men and women and their experiences in higher education during their reentry. The participants did not explicitly reveal gender differences during their reentry; this is consistent with previous research (Sussman, 2002). However, they shared that they could observe imbalanced ratios between men and women professionals in higher education within their field. Thus, the findings of this study add more explanations to the literature. The participants did not specify any advantages or disadvantages because individual professionals experience their reentry differently, considering many other factors. Instead, they suggested that the role of women professionals and their leadership in the field are crucial when representing and advocating for themselves and society. Moreover, the study participants had to decide on their reentry by considering numerous factors, such as family issues, job factors, visas, and personal preference. Commonly, the participants described these factors as being all intertwined, impacting their unstable status as foreigners in the U.S., regardless of employment. The previous studies described a lack of preparation of individuals, which created challenges during their reentry after studying abroad (Sussman, 2002). Similarly, the findings of this study suggest that a normal amount of nervousness and awakening are helpful for reentry professionals. Reentry into one’s home country brings about lots of joy and expectation; however, it is accompanied by mental anguish and numerous challenges (Rogers and Ward, 1993; Chiu, 1995).

To summarize, learning through cross-cultural experiences (in life and academia) impacted the behavioral aspects accompanying the cognitive domain. Ambivalence is an intricate aspect that requires further research. For instance, the ambivalence in relation to the reentry decision of international faculty members in higher education institutions in the U.S., and how this influences their behavioral, affective, and cognitive aspects during readjustment, would provide another angle with which to view the reentry of professionals. Previous literature has used “reverse culture shock” and/or the “u-curve” to explain the readjustment of returnees to their home culture.

There were several limitations in this study. Although the study focused on the common features of reentry expressed in the interviews of the participants, it is difficult to generalize these findings due to the small number of participants. It would be more informative to study numerous individuals in future research. Furthermore, this study did not specify the decisions behind the reentry of the returnees. Depending on various circumstances, their affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects during their reentry could be explained differently. The study participants were limited to the field of kinesiology; however, their length of study outside their home country was not considered, although we limited the range to within 10 years. Cross-cultural experiences and readjustments to the home country in other areas of study and contexts can be described differently. Moreover, while acculturation patterns have tended to be perceived negatively, the participants in this study perceived their cross-cultural acculturation process as having two sides. This is partly because they are currently in a stable position. If the targeted professionals still had to seek secure jobs, the findings could be either more skeptical or constructive. Future studies could focus on more negative factors and on the overcoming strategies used by returnees.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board of New Mexico Highlands University (N.B. the IRB of the author’s own institution were unavailable due to COVID19-related administrative delays). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was also obtained from the participants for the publication of any potentially identifiable data included in this article. The stated names are pseudonyms.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andrianto, S., Jianhong, M., Hommey, C., Damayanti, D., and Wahyuni, H. (2018). Re-entry adjustment and job Embeddedness: the mediating role of professional identity in Indonesian returnees. Front. Psychol. 9:792. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00792

Berry, J. W. (2017). “Theories and models of acculturation”, in Oxford handbook of acculturation and health, eds. S. J. Schwartz and J. B. Unger (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 15–27.

Bozionelos, N., Bozionelos, G., Kostopoulos, K., Shyong, C.-H., Baruch, Y., and Zhou, W. (2015). International graduate students’ perceptions and interest in international careers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 26, 1428–1451. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.935457

Brabant, S., Palmer, C. E., and Gramling, R. (1990). Returning home: an empirical investigation of cross-cultural reentry. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 14, 387–404. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(90)90027-T

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chiu, M. L. (1995). The influence of anticipatory fear on foreign student adjustment: an exploratory study. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 19, 1–44. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(94)00022-P

Cox, J. B. (2004). The role of communication, technology, and cultural identity in repatriation adjustment. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 28, 201–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2004.06.005

Dennis, M. J. (2020). 2019 open doors report on international educational exchange — any surprises? Enrol. Manag. Rep. 23, 1–3. doi: 10.1002/emt.30618

Eugenia Sánchez Vidal, M., Sanz Valle, R., Isabel Barba Aragón, M., and Brewster, C. (2007). Repatriation adjustment process of business employees: evidence from Spanish workers. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 31, 317–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.07.004

Gebhard, J. G. (2012). International students’ adjustment problems and behaviors. JISS 2, 184–193. doi: 10.32674/jis.v2i2.529

Hsiao, F. (2011). From the ideal to the real world: a phenomenological inquiry into student sojourners’ reentry adaptation. J. Music. Ther. 48, 420–439. doi: 10.1093/jmt/48.4.420

Hyder, A. S., and Lövblad, M. (2007). The repatriation process – a realistic approach. Career Dev. Int. 12, 264–281. doi: 10.1108/13620430710745890

Institute of International Education . (2020). Fall 2020 International Student Enrollment Snapshot. Available at: https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Open-Doors/Fall-International-Enrollments-Snapshot-Reports

Jung, A.-K., Lee, H.-S., and Morales, A. (2013). Wisdom from Korean reentry counseling professionals: a phenomenological study of the reentry process. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 35, 153–171. doi: 10.1007/s10447-012-9174-4

Ko, K. S. (2019). Reentry experiences of dance/movement therapists in East Asia after training in the United States. Arts Psychother. 66:101556. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2019.02.005

Lee, J. J., and Kim, D. (2010). Brain gain or brain circulation? U.S. doctoral recipients returning to South Korea. High. Educ. 59, 627–643. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9270-5

Lincoln, Y. S., Guba, E. G., and Pilotta, J. J. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 9, 438–439. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

MacDonald, S., and Arthur, N. (2003). Employees’ perceptions of repatriation. Can. J. Career Dev. 2, 3–11.

Martin, J. N., and Harrell, T. (2004). “Intercultural reentry of students and professionals: theory and practice” in Handbook of intercultural training (United States: SAGE Publications, Inc.), 309–336.

Mesidor, J. K., and Sly, K. F. (2016). Factors that contribute to the adjustment of international students. JISS 6, 262–282. doi: 10.32674/jis.v6i1.569

Patton, M. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 4th Edition. Sage. Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Rienties, B., Beausaert, S., Grohnert, T., Niemantsverdriet, S., and Kommers, P. (2012). Understanding academic performance of international students: the role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. High. Educ. 63, 685–700. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9468-1

Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 11, 25–41. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

Rogers, J., and Ward, C. (1993). Expectation-experience discrepancies and psychological adjustment during cross-cultural reentry. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 17, 185–196. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(93)90024-3

Shen, Y.-J., and Herr, E. L. (2004). Career placement concerns of international graduate students: a qualitative study. J. Career Dev. 31, 15–29. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCD.0000036703.83885.5d

Spencer-Rodgers, J. (2000). The vocational situation and country of orientation of international students. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 28, 32–50. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2000.tb00226.x

Sussman, N. M. (2001). Repatriation transitions: psychological preparedness, cultural identity, and attributions among American managers. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 25, 109–123. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(00)00046-8

Sussman, N. M. (2002). Testing the cultural identity model of the cultural transition cycle: sojourners return home. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 26, 391–408. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00013-5

Szkudlarek, B. (2010). Reentry—a review of the literature. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 34, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.06.006

Keywords: re-entry, international students, kinesiology doctorate, qualitative inquiry, re-acculturation

Citation: Park S (2023) The reentry of Asian kinesiology professionals after obtaining a doctorate at higher education institutions in the U.S. Front. Educ. 8:1083362. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1083362

Edited by:

Muhammad Awais Bhatti, King Faisal University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Yuho Kim, University of Massachusetts Lowell, United StatesAloysius H. Sequeira, National Institute of Technology, Karnataka, India

Copyright © 2023 Park. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seungyeon Park, cGFya3NldW5neWVvbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Seungyeon Park

Seungyeon Park