- 1Department of English, University of Zanjan, Zanjan, Iran

- 2Language Teaching Group, Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences (IASBS), Zanjan, Iran

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between Iranian EFL Learners’ perfectionism and writing anxiety and their performance in the IELTS Writing Module. To this end, sixty-eight Iranian EFL learners were selected via convenience sampling. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale developed and validated by Hewitt and Flett (1991) and Second Language Writing Anxiety Inventory devised by Cheng (2004) were administered to the participants. The participants were then asked to write on an assigned topic from IELTS Writing Task 2. The findings of the study indicated that of the three dimensions of perfectionism (i.e., self-oriented, other-oriented and socially prescribed), none were associated with the learners’ writing performance, while a significant negative relationship was found between the learners’ writing anxiety consisting of somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety, and avoidance behavior and their writing performance. The results of multiple regression analysis suggested that somatic anxiety, and avoidance behavior were significant predictors of writing performance. The implications highlight the strategies that should be deployed by educational policy-makers, practitioners, and examiners to alleviate anxiety in L2 classrooms, promoting a safe and stress-free educational environment.

Introduction

Writing remains a cognitive and emotional challenge even to greatest authors of all times. As a complex process, it demands managing an array of skills–as writers are often required to orchestrate their knowledge of the subject and linguistic prowess on the one hand, and almost inevitably, overcome a sense of utter apprehension on the other. According to Sokolic (2003), writing has both physical and mental aspects, including the physical act of committing ideas to some medium and the mental work of inventing ideas, thinking about ways of expressing them, and organizing them into sentences and paragraphs. As far as L2 writers are concerned, writing is simultaneously a requirement and an obstacle for academic success. L2 writing may prove a particular challenge for EFL learners as they are yet in the process of language acquisition. The writing performance of some highly apprehensive learners, on the other hand, may be adversely affected as they struggle with anxiety issues or aspects of perfectionism.

As elaborated below, there exists conflicting literature within the Iranian context (and beyond) on whether or not perfectionism or anxiety significantly predict EFL learners’ writing performance. With a special focus on L2 writing as a challenging productive skill, this study aims to investigate the relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ perfectionism and writing anxiety and their performance in the IELTS writing module. In particular, it surveys the multidimensional aspects of both perfectionism (i.e., self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed) and writing anxiety (i.e., somatic, cognitive, and behavioral).

Literature review

A multidimensional perspective on perfectionism

Perfectionism is defined as “holding standards that are beyond reach, striving to reach these impossible goals, and defining one’s own worth by the accomplishment of these standards” (Patcht, 1984, p. 386). Perfectionists are in pursuit of perfection, set unrealistic goals for themselves, and assume mistakes as a sign of disgrace (Hewitt and Flett, 1991). Some studies have demonstrated meaningful links between perfectionism and psychopathological issues (Patcht, 1984; Saboonchi and Lundh, 1997; Flett et al., 2016). Patcht (1984) asserts that perfectionism is debilitating in nature and associated with physical disorders such as depression, eating disorder (anorexia), and alcoholism. His perspective is in line with Hewitt and Flett (1991) and Hewitt and Flett (2002), according to whom maladjustments originate from the perfectionists’ attempts to set unrealistic goals, exaggerate one’s failure, and have excessive self-evaluation. According to Hamacheck (1978) perfectionism has both adaptive and maladaptive aspects: “normal” and “neurotic.” Normal perfectionism is setting high standards while being flexible; it is associated with striving for perfection without annoying oneself. Neurotic perfectionism, on the other hand, is setting high standards with a special concern over mistakes; it is accompanied by negative feelings of self-criticism or self-blame. Similarly, Slade and Owens (1998) regard positive perfectionism as predominantly normal/healthy with positive benefits for the individual, while negative perfectionism would be pathological, unhealthy, and disadvantageous.

There are several multidimensional conceptualizations of perfectionism. Frost et al. (1990) devised a Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS)–a self-report, 35-item measure that identified such dimensions as, concern over mistakes, excessive concern with parents’ expectations and evaluation, excessively high personal standards, concern with precision, order and organization, and doubts about the quality of actions. The present study utilized the MPS developed by Hewitt and Flett (1991). The model rates three aspects of perfectionistic self-presentation: self-oriented perfectionism refers to having unrealistic expectations for oneself, which may lead to depression when individuals find themselves unable to meet such high standards. It is accompanied by “self-criticism, intense self-scrutiny, and inability to accept any mistake” (Gould, 2012, p. 16). Socially prescribed perfectionism refers to developing perfectionistic standards due to real or perceived high expectations from significant others; this may result in depression, anxiety, or anger if individuals are faced with negative evaluation. Other-oriented perfectionism is having high standards for others and expecting them to behave impeccably; this may have negative consequences such as anger, inflexibility, and intolerance (Gould, 2012) beside losing trust and feeling a sense of loneliness and resentment (Hewitt and Flett, 1991).

Perfectionism and language learning anxiety

As indicated above, one of the negative outcomes of perfectionism is anxiety. Anxiety, in general, is the negative emotion associated with feelings of anger, sadness, and disgust. It is also future-oriented, as the person suffering from anxiety anticipates unpleasant events to occur in the future and encompasses both mental and physical manifestations: “nervousness and unpleasant thoughts” are the mental symptoms of anxiety, while “pounding heart, perspiration and gastric disturbance” are its physical manifestations (Zeidner and Matthews, 2011, p. 2).

Within the educational context, Dobson (2012) suggests that some academic tasks may be anxiety-provoking and teachers should be sensitive to symptoms of anxiety in learners so as to help them cope with their negative feelings. Thus students with high levels of anxiety are more prone to poor academic performance or self-efficacy. Several studies have been conducted to investigate the role of language anxiety in learning (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1991, 1993, 1994; Young, 1991). Young (1991) argued that creating a low-anxiety classroom is the current challenge of language teaching. Similarly, MacIntyre and Gardner (1991) suggested that anxiety poses several problems for learners since it may “interfere with acquisition, retention, and production of the new language” (p. 2). Thus various studies have explored the impact of foreign language anxiety on specific language skills (i.e., speaking, listening, reading, and writing) and found a negative connection between them.

Flett et al. (2016) proposed a model of perfectionism and language learning which explained the factors that lead to the learners’ anxiety. It was composed of “trait perfectionism,” “perfectionist cognitions,” “perfectionist self-representation,” “self-efficacy,” “concern over mistakes,” and “anxiety.” Thus “trait perfectionism” is attributed to three dimensions of perfectionism which include self-oriented perfectionism (demanding perfection for oneself), other-oriented perfectionism (emphasizing on others’ capabilities), and socially prescribed perfectionism (assuming that others have unrealistic expectations form oneself). “Perfectionist cognitions” refer to the automatic thoughts that stem from over-emphasizing on achieving the best outcomes. The individuals who are preoccupied with perfectionistic thoughts are in danger of psychopathological issues such as anxiety or depression. “Perfectionistic self-representation” refers to the tendency of an individual to show oneself as impeccable while trying to hide one’s imperfections at the same time. According to Flett et al. (2016), some individuals spend considerable time to seem flawless in public; but no matter how hard they try, they still seems far from perfect to themselves. “Reduced self-efficacy” is characterized by certain adverse effects such as self-criticism or pessimism. Based on this model, Flett et al. (2016) suggested that striving for excellence, reduced self-efficacy, and concern over mistakes are among the factors that lead to language anxiety.

Writing anxiety and its multiple dimensions

Cheng (2004) defined writing anxiety as a language-skill-specific anxiety and distinguished it from general second language classroom anxiety. Language anxiety is “the apprehension experienced when a situation requires the use of a second language with which the individual is not fully proficient” (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1993, p. 5); in effect, this is “the feeling of tension and apprehension specifically associated with second language contexts including speaking, listening and learning” (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1994, p. 2). Foreign language writing apprehension, on the other hand, is a term that was coined by Daly (1978) to describe an individual’s tendency to approach or avoid situations perceived to potentially require writing. The highly apprehensive individual finds the experience of writing more punishing than rewarding (Daly and Miller, 1975). Richards and Schmidt (2010) set forth this comprehensive account of the issues in language anxiety:

Issues in the study of language anxiety include whether anxiety is a cause or an effect of poor achievement, anxiety under specific instructional conditions, and the relationship of general language anxiety to more specific kinds of anxiety associated with speaking, reading, or examinations (p. 313).

In his endeavor to develop a measure of writing anxiety, Cheng (2004) concluded that the construct is multidimensional and mentioned the plethora of studies on anxiety that took a multidimensional approach to its conceptualization. His measure of second language writing anxiety, which is the framework adopted for the current study, was comprised of three dimensions: Cognitive Anxiety, Somatic Anxiety¸ and Avoidance Behavior. Cognitive Anxiety, which is a mental element, is marked by negative judgments on one’s own behavior, negative self-talk, and inability to concentrate (Martens et al., 1990; Jarvis, 2002). According to Cheng (2004), cognitive anxiety is the mental aspect of the anxiety experience that is characterized by “negative expectations, preoccupation with performance, and concern about other’s perceptions” (p. 316). Somatic Anxiety is in effect the physiological element which is accompanied by autonomic arousals and negative symptoms such as nervousness, high blood pressure, dry throat, and sweaty palms (Martens et al., 1990; Jarvis, 2002). Morris et al. (1990), define somatic anxiety as “one’s perception of the physiological effects of the anxiety experience, as reflected in increase in ‘automatic arousal of unpleasant feelings, such as nervousness and tension’” (quoted in Cheng, 2004, p. 541). Avoidance Behavior refers to the behavioral aspect in avoidance of writing, which can manifest in attempting to avoid failing in an exam, ignoring the presence of an unfavorable person, etc. (Nussinson et al., 2012). Avoidance Behavior is stimulated by unfavorable or unwanted events or possibilities. It seems that individuals endeavor to maximize the distance between themselves and the intimidating objective or goal.

Writing anxiety and writing performance

Anxiety and performance are interwoven in academic writing as an arduous task which demands “the development of a design idea, the capture of mental representations of knowledge, and of experience with subjects” (Ĵosef, 2001, p. 16). Daly (1978) confirmed that individuals with low levels of writing apprehension outperform individuals with high levels of writing apprehension, as they scored significantly better on grammar, mechanics, and larger concerns in writing skills. Highly apprehensive learners, on the other hand, wrote with lower quality and failed to demonstrate a strong knowledge of writing skills. By the same token, Hanna (2010) demonstrated that students with a higher level of writing apprehension produced a lower quality paper as compared to their low apprehensive counterparts.

In Iran, Saedpanah and Mahmoodi (2020) investigated the relationships among critical thinking, writing strategy use, L2 writing anxiety, and L2 writing performance. Their findings revealed a significant negative relationship between L2 writing performance and L2 writing anxiety, and suggested that L2 writing anxiety was a stronger predictor of L2 writing performance. In the same context, Jebreil et al. (2015) explored the relationship between anxiety and learners’ performance in writing. The results indicated that cognitive anxiety was the most common type of anxiety, followed by somatic anxiety, and avoidance behavior. Moreover, elementary level EFL learners experienced higher level of writing anxiety than intermediate and advanced levels.

Kim (2006) investigated the relationship between Korean college students’ writing anxiety and their writing achievement. The results indicated that the students suffered from negative self-perception about writing, apprehension of evaluation, and negative feelings toward writing, and that there were significant correlations between writing apprehension and the students’ final course grades. Further, female students were more apprehensive than males.

Erkan and Saban (2011) sought to identify whether writing performance in students of English as a foreign language is related to writing apprehension. The results showed that among these tertiary-level EFL students, writing apprehension and writing performance are negatively correlated. Ayodele and Akinlana (2012) examined the relationship between writing apprehension and undergraduates’ interest in dissertation writing on the one hand, and the moderating roles of self-efficacy, emotional intelligence and academic optimism on the other. Their findings demonstrated a lack of association between writing anxiety and the undergraduates’ interest in writing their final project.

Tadesse (2013) studied the impact of writing anxiety on students’ writing. In this regard, in addition to administration of SLWAI (Second Language Writing Anxiety Inventory) to students, interviews were designed for English teachers. Among 69 students, only 18 were reported to be non-anxious. On the other hand, the teachers’ exclusive focus on grammatical mistakes had seemingly demotivated the students. Limiting the amount of error correction, appreciating novel ideas, and providing adequate feedback were among the recommended strategies to alleviate students’ anxiety. In a recent study, Rabadi and Rabadi (2020) probed the levels, types, and causes of foreign language writing anxiety and observed a high level of writing anxiety, especially cognitive, among medical students. They attributed this to language-related problems, inadequate practice in writing, low self-confidence in writing, and fear of writing tests.

Perfectionism and academic performance

Gilman and Ashby (2003) examined middle school students’ perfectionism and noticed that adaptive perfectionists reported significantly higher scores on various academic, intrapersonal, and interpersonal variables while maladaptive perfectionism was significantly linked to negative attitudes toward school and family relationships, and high intrapersonal distress. In a recent study by Wang and Wu (2022) the associations between maladaptive perfectionism and life satisfaction was examined and the former was found to be significantly and negatively related to the latter among medical students. Furthermore, academic burnout was confirmed as playing a mediating role in such association especially for students with high self-esteem. Huang et al. (2022) focused their attention on maladaptive perfectionism (MP) and its impact on academic procrastination along with resilience and coping style. They identified a positive effect of MP on academic procrastination which was partially mediated by resilience. This mediation was subject to change due to the levels of positive coping style in the students. Tóth et al. (2022) investigated the role of irrational beliefs and both adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism on the competitive anxiety of sport professionals and noticed that both forms of perfectionism were positively associated with cognitive and somatic competitive anxiety. Perfectionism also mediated the influence of irrational beliefs on the competitive anxiety.

Rice and Dellwo (2002) assessed the implications of perfectionism and self-development for college adjustment. The results showed that while adaptive perfectionists and nonperfectionists demonstrated comparable aspects of emotional adjustment and academic integration, maladaptive perfectionists demonstrated the poorest adjustment.

Comerchero and Fortugno (2013) examined the correlational relationship between adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism and statistics anxiety in graduate psychology students. The findings of the study indicated that students who had higher scores on the APS-R Discrepancy scale also had greater levels of statistics anxiety on several STARS scales. That is, there was a clear relationship between discrepant (maladaptive) perfectionism and statistics anxiety. In a similar vein, Wu et al. (2022) explored the impact of perfectionism and statistics anxiety on academic performance (AP) in statistics courses. Among the dimensions of perfectionism, personal standards had a direct positive effect on AP in statistics courses and parental expectations were identified as having an indirect negative effect on AP.

Inglés et al. (2016) examined a different kind of anxiety, i.e., school anxiety, and observed that non-perfectionist students generally have lower levels of anxiety than students with high levels of personal standards and low levels of evaluative concerns. It was also revealed that the combination of high levels in both dimensions (Self-Oriented Perfectionism and Socially Prescribed Perfectionism) would have the most adverse effect on school anxiety. Hewitt et al. (2002) examined the association between perfectionism and anxiety among children. The results suggested that whereas self-oriented perfectionism has a positive correlation with depression and anxiety, socially prescribed perfectionism is positively associated with anxiety and social stress. Furthermore, in comparison to self-oriented perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism was more connected to psychological problems.

Ogurlu (2020) investigated the relationship between perfectionism and giftedness. The findings suggested that dimensions of perfectionism were a significant moderator and that gifted students performed better than their non-gifted peers on perfectionistic strivings – yet they rated lower when it came to perfectionistic concerns.

Various empirical studies in the Iranian context are in fact a correlational study of perfectionism and issues in language education. Roohafza et al. (2010) examined the relationship between perfectionism, anxiety, and achievement. The results indicated that negative perfectionism was a positive and significant predictor of depression and anxiety, while positive perfectionism predicted anxiety and depression significantly and negatively. Results also suggested that age can potentially increase anxiety and depression as well as decrease the learners’ achievement. Pishghadam and Akhondpoor (2011) examined the relationship between learners’ perfectionism, academic achievement, and anxiety and identified a negative relationship between the learners’ reading, listening, speaking skills and perfectionism. Their observation suggested that more perfectionist students gain lower scores. Also, higher scores in perfectionism were associated with higher scores in trait anxiety, suggesting that more perfectionist students would experience higher levels of trait anxiety. Chasetareh et al. (2023) investigated the relationship between perfectionism and EFL learners’ achievement, considering motivation and self-regulated learning as possible mediators. Their findings revealed that “higher levels of rigid perfectionism were positively related to deep learning and persistence that, in turn, were related to higher L2 achievement.” On the other hand, “self-critical perfectionism was negatively related to deep learning and persistence that, in turn, were related to lower L2 achievement.” Ghorbandordinejad (2014) examined the relationship between perfectionism and learners’ achievement, but the results did not show any significant correlation between the two variables. Moradan et al. (2013) investigated the relationship between perfectionism and Iranian EFL learners’ listening comprehension. The results were indicative of a strong negative relationship between the two variables, suggesting that perfectionists exhibit more deficiency in performing listening tests. Deficiency was seemingly caused by over-emphasis on details or trying to understand every single word.

While some studies in Iran proposed that there is a link between perfectionism and language performance (Pishghadam and Akhondpoor, 2011; Moradan et al., 2013), some others did not find such a relationship (Ghorbandordinejad and Farjad Nasab, 2013). Also, while Stoeber (2012) observed that aspiring for excellence may encourage individuals to set wiser goals for the future, Flett et al. (2016) suggested that perfectionism is a personality trait that contributes to language anxiety and deficiency (2016). In several studies on perfectionism, anxiety has been identified as a concomitant condition (e.g., Hewitt and Flett, 1991). Again, while Ayodele and Akinlana (2012) did not find a direct relationship between writing apprehension and learners’ interest in writing, Saedpanah and Mahmoodi (2020) identified writing anxiety as a stronger predictor of writing performance. Thanks to such lack of consensus in the EFL educational context with regard to the roles of perfectionism and anxiety in L2 performance, as well as scarcity of literature on their role in writing as a productive skill, this study aimed to investigate the role of these variables on the writing performance of Iranian EFL learners. In particular, it incorporates a multidimensional perspectives on both perfectionism (i.e., self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed) and writing anxiety (i.e., somatic, cognitive, and behavioral).

Research questions

This study aims to investigate the relationship between perfectionism and writing anxiety on one hand and learners’ writing performance on the other in the Iranian context. It also aims to find out whether the components of perfectionism and writing anxiety can predict learners’ writing performance. To this end, the following questions are addressed:

1. Is there any significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ level of perfectionism (Self-oriented, Other-oriented, Socially Prescribed) and their performance in IELTS writing module?

2. Is there any significant relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ writing anxiety (Somatic Anxiety, Cognitive Anxiety, Behavioral Anxiety) and their performance in IELTS writing module?

3. Which dimension(s) of perfectionism and writing anxiety more significantly predict(s) the writing performance of Iranian EFL learners in IELTS writing module?

Methodology

The design of the study

This study adopted a post facto design and focused on finding the relationship between explanatory variables of perfectionism (i.e., self-oriented, other-oriented and socially prescribed) and writing anxiety (i.e., somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety, avoidance behavior) and the response variable (writing performance). The secondary purpose of the study was to investigate which variables can better predict EFL students’ writing scores.

Participants

The sample of the current study included N = 68 students, selected via convenience sampling, from 150 students majoring in English Translation at the University of Zanjan. The participants included both male (N = 24) and female (N = 44) EFL learners and the age range was 18–25. This sample is fairly representative of the population of students in the English Department in terms of gender and age, as most of the students are young adult females. The majority of the students at the Department have an intermediate to early advanced proficiency in English depending on the years they have been studying. Regarding the adequacy of sample size for the regression analysis, Larson-Hall (2015) suggests the sample size needed for an effect sizes of R2 = 0.20, R2 = 0.30, and R2 = 0.50 with 80% power in regression and six predictors is at least 58, 36, and 19, respectively. In addition, with three predictors, a sample size of 58 is needed for an effect size of R2 = 0.15 with 80% power in regression. Therefore, the sample size of N = 68 can be considered adequate for the purposes of this research.

Instruments

Three instruments were used in this study: (a) Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (developed by Hewitt and Flett, 1991), (b) Second Language Writing Anxiety Inventory (developed by Cheng, 2004), and (c) IELTS Writing Task 2 assigned to the participants to assess their writing performance.

Multidimensional perfectionism scale

MPS scale for perfectionism was developed by Hewitt and Flett (1991) in order to demonstrate the multidimensionality of the concept and show its associations with psychopathology. It entails three subscales aiming to assess self-oriented (e.g., one of my goals is to be perfect in everything I do), other-oriented (e.g., I have high expectations from the people who are important to me) and socially prescribed (e.g., my family expects me to be perfect). The scale is in Likert format with items ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. Each dimension of perfectionism has 15 items with a total number of 45 items; however, a number of items are negatively worded and hence need reverse scoring in SPSS. Therefore, items 8,12,34,36 (self-oriented subscale), items 2,3,4,10,19,38,43,45 (other-oriented subscale), and items 9,11,21,30,37,44 (socially prescribed subscale) are reversely scored. According to Hewitt and Flett (1991), the scale enjoys acceptable reliability and validity. Specifically, the test–retest reliability of the subscales was: 0.88 for self-oriented, 0.85 for other-oriented, and 0.75 for socially prescribed perfectionism. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the overall scale to ensure the reliability of the questionnaire. The obtained index was 0.831, which is satisfactory.

Second language writing anxiety inventory

Essentially a self-report writing anxiety scale for EFL and ESL learners, this was developed by Cheng (2004). The rationale behind its development was the shortcoming of earlier scales that assumed anxiety as a unidimensional concept. In SLWAI anxiety is perceived as a multidimensional construct, which may have differential effect on various aspects of human behavior. The original inventory developed by Cheng consisted of 27 items; however, analyzes showed that items 5,11,16,20,25 suffered from lack of face validity and consistency. Hence only 22 items–which belong to the three subscales of avoidance behavior (items 4,6,12,14,19,12), somatic anxiety (items 2,7,9,13,15,18), and cognitive anxiety (items 1,3,8,10,17,21,24). Furthermore, since items 1,4,7,17,18,21,22 were negatively worded, they needed reversed scoring in SPSS prior to the data analysis. The evidence for reliability of the scale was established by Cheng (2004): the test–retest reliability estimates of three subscales were reported as 0.91 for the whole scale, 0.82 for somatic anxiety subscale, 0.83 for the avoidance behavior subscale, and 0.81 for the cognitive anxiety subscale. To ensure the reliability of the instrument, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated in this study and was found to be satisfactory (α = 0.825).

IELTS writing task 2

In order to investigate the students’ performance in writing, IELTS Writing Task 2 was administered. The topic was chosen from Improve Your Writing Skills: Writing for IELTS by Dimond-Bayir (2014) which is a self-guide book for candidates who are preparing for the IELTS exam. The students were instructed to write at least 250 words in about 40 min. The writing samples were assessed by two anonymous raters who were well-experienced in teaching IELTS writing courses. In order to assess the inter-rater reliability of writing scores, Cohen’s Kappa was run. According to Riazi (2016), Cohen’s Kappa was developed to assess the agreement between two or more raters (observers) and the range of 0.42–0.60 indicates a moderate agreement between the raters. In this study, there was a moderate agreement between two raters (k = 0.428, p < 0.0005). The average of the scores given by the two raters demonstrated each students’ writing score. The writings of students were analyzed in terms of task achievement, coherence and cohesion, lexical resource and grammatical range and accuracy based on IELTS band calculator. The scores ranged from 2 to 9. However, as expected the majority of students scored 4–7, which indicates intermediate to early advanced levels of proficiency not only in writing but also in general English.

Procedure

The questionnaires of perfectionism scale (MPS) and writing anxiety scale (SLWAI), which comprised of 45 and 22 items, respectively, were administered. Meanwhile, the participants were asked to take a glance at the items and see if they were comprehensible. The learners were encouraged to seek clarification in case there were any difficulties and the researcher was responsible for responding to their enquiries. Finally, the learners were asked to write an essay. They were given 40 min to write at least 250 words on a selected topic; the samples were then gathered and scored by two IELTS examiners according to four band descriptors. Having collected the data, they were analyzed using the latest version of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Bootstraping was used to calculate the correlation and regression statistics. This method is a nonparametric resampling technique independent of normal sampling distribution that generates an approximation of the sampling distribution (Larson-Hall, 2015). As a robust statistical technique, boostraping is recommended when variables are not normally distributed (Larson-Hall, 2015). The bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) were based on 1,000 bootstrap samples with 95% confidence interval and with bias correction and acceleration (BCa). CIs containing a zero are insignificant. To investigate the correlation between the learners’ performance on the writing task and their perfectionism and writing anxiety Pearson correlation was used. In order to observe which of the variables produced the strongest effects and best explained the writing performance of the EFL students, a standard multiple regression was run.

Results

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the obtained data from the questionnaires and the writing task.

Descriptive statistics

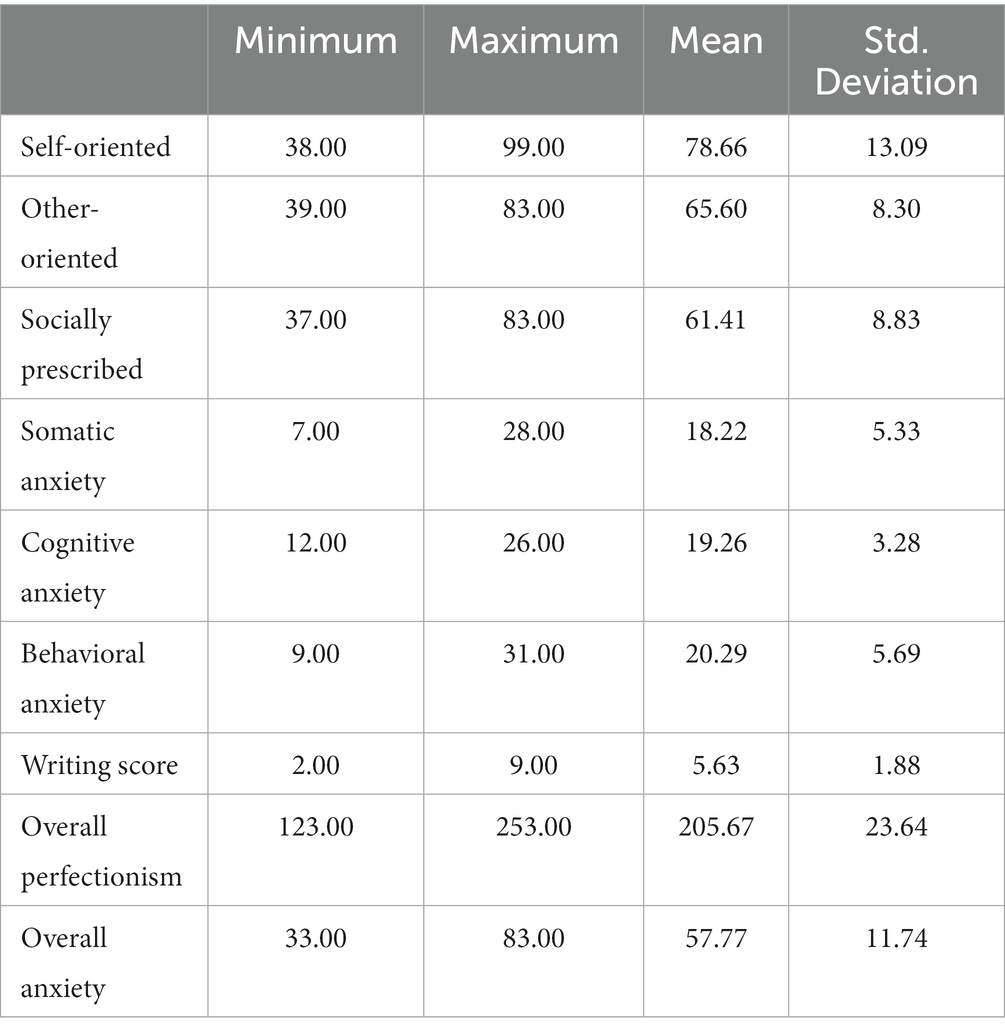

Descriptive statistics of each variable were first calculated for subsequent analyzes. In Table 1, the mean scores of the components of perfectionism and writing anxiety plus writing scores are reported. As for the Self-oriented, Other-oriented, and Socially Prescribed, the mean scores are 78.66, 65.60, and 61.41, respectively. Furthermore, Somatic Anxiety, Cognitive Anxiety and Behavioral Anxiety mean scores emerged to be 18.22, 19.26, and 20.29, respectively. The total mean score of writing is 5.63.

Inferential statistics

The relation between dimensions of perfectionism, writing anxiety and writing performance

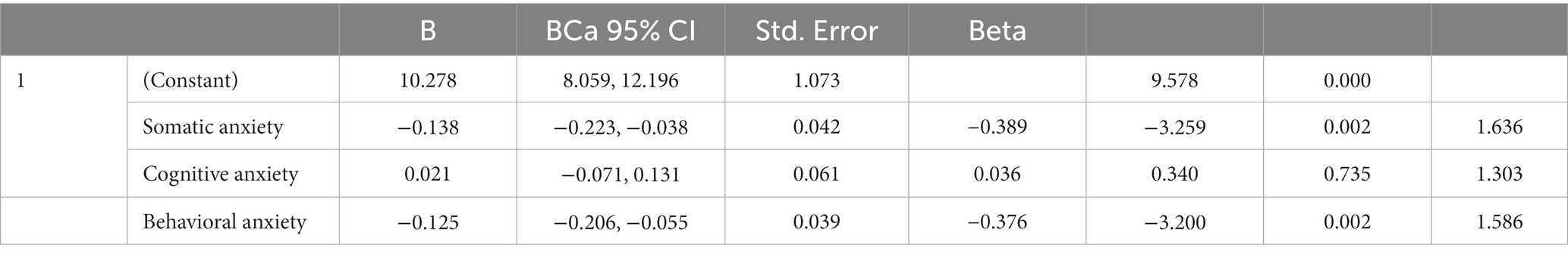

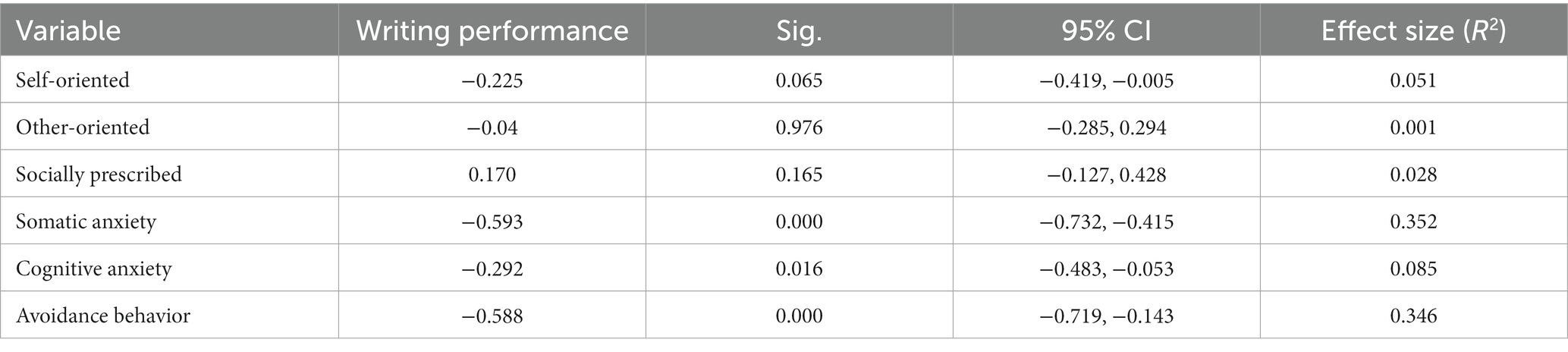

With regard to the first research question, which aims at investigating the relationship between the participants’ level of perfectionism and their performance on IELTS writing module, a Pearson correlation (r) did not find a significant relationship between perfectionism and writing performance (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation between predictors of writing perfectionism and anxiety with writing performance (N = 68).

However, with regard to the relationship between writing anxiety and performance, the results (Table 2) suggest a significant and negative relationship. In particular, the relationship between somatic anxiety and avoidance behavior and writing performance is moderate and the effect size can be argued to be fairly large (Cohen, 1992; Plonsky and Oswald, 2014). The relationship between cognitive anxiety and writing performance is smaller and the effect size can be argued to be small (Plonsky and Oswald, 2014) to medium (Cohen, 1992). Further, the intercorrelations among the predictors of writing anxiety were all significant at p < 0.01 and ranged between r = 0.41 to r = 0.59, which means these variables are not highly intercorrelated and suitable to be included in a regression analysis. In addition, as shown in Table 3, the collinearity index VIF for all the variables is less than 5 which means there is not any multicollinearity among the variables.

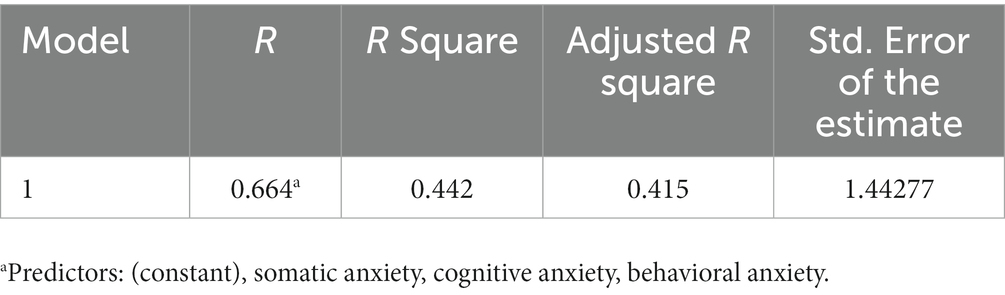

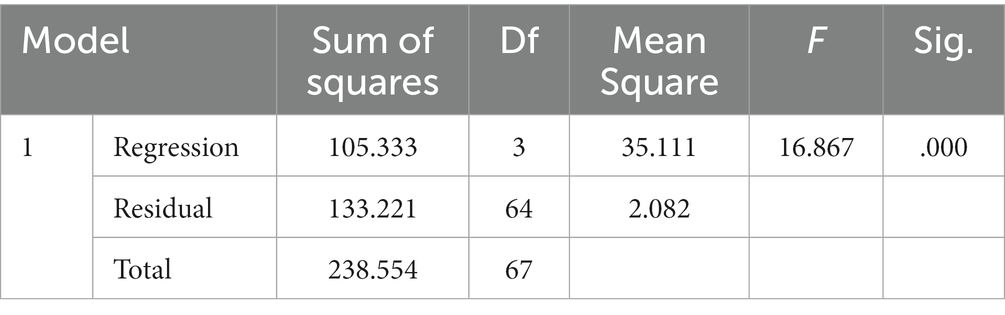

The predictive power of writing anxiety in relation to writing performance

As the relationship between the components of perfectionism and writing was not significant, a standard multiple regression analysis was performed to identify the relative contribution of writing anxiety components to the writing scores. The results of the multiple regression analysis (Table 4) suggest that among the variables of writing anxiety, only somatic anxiety and behavioral avoidance are significant (Table 5). Further, perhaps more importantly, 0.44% (R2 = 0.442) of the variation in the writing scores of the EFL students can be accounted for by the model and the model is significant (Table 3), which is considered a large effect size.

Discussion and conclusion

The results, as reported in the previous section, revealed that the components of perfectionism, are not correlated with writing performance. This was not entirely unexpected, although some studies have suggested there is a link between perfectionism and language performance (Pishghadam and Akhondpoor, 2011; Moradan et al., 2013). The results of the current study is more in line with those of Ghorbandordinejad and Farjad Nasab (2013) who did not find such a relationship. According to Dudley-Evans and St. John (2013), writing involves “having an awareness of the community’s values and expectations and an ability to resolve the tension between writers’ creative needs and the norms for writing” in a particular genre. Complicated by self-oriented learners’ inaccessible goals and the fact that they prefer to avoid tasks that cannot be accomplished faultlessly, getting low grades on the IELTS writing task is explicable. Similarly, the study by Pishghadam and Akhondpoor (2011), observed how perfectionistic tendencies are associated with low academic achievement and poor performance in language skills. However, their study did not take a multidimensional approach to the construct of perfectionism, preferring alternatively to view it as a whole. Moradan et al. (2013) also observed a strong negative relationship between perfectionism and EFL learners’ listening comprehension. On the contrary, Ghorbandordinejad (2014), as well as Ghorbandordinejad and Farjad Nasab (2013) did not find a significant correlation between perfectionism and learners’ achievement.

Lack of a significant correlation between other-oriented perfectionism and writing scores lies at the very root of the concept. This dimension of perfectionism is directed at others and deals with setting unrealistic expectations for others. It brings along feelings of dominance and the need to reduce others’ worth, thereby elevating one’s self-worth. As such, it may bear little importance to the performance of students on a writing assignment.

As stated by Comerchero and Fortugno (2013), a large body of research has associated adaptive perfectionism with positive psychological outcomes and maladaptive perfectionism with negative correlates. The adverse effect of maladaptive perfectionism on a person’s academic performance is already well-documented in the literature (Rice and Dellwo, 2002; Gilman and Ashby, 2003). With respect to the other-oriented perfectionism and its lack of a significant connection to the dependent variable, there are studies such as Hewitt and Flett (2002) and La Rocque et al. (2016) reporting the different behavior of this dimension compared to the other two ones. Given the mixed findings in the literature and this study about the relationship between perfectionism and language performance further research with a larger and more diverse body of participants can shed more light on the issue.

The second research question dealt with writing anxiety and its correlation with writing performance. The finding, primarily, indicated an overall negative relationship between the two variables. This is consistent with Krause’s (1994) theory which postulates that those with low writing apprehension are more likely to perform better on tests of writing skills than apprehensive writers. It also corroborates the claim that apprehension often impedes performance. This claim has already been attested in earlier studies such as Daly (1978), Hanna (2010), and Kim (2006). The obtained result is also in conformity with the Erkan and Saban’s (2011) study whose focus was on EFL students at tertiary level in addition to Saedpanah and Mahmoodi (2020). The latter, in a similar way, identified L2 writing anxiety as a stronger predictor of L2 writing performance.

However, the negative correlation between writing anxiety and writing performance in the current research is in contrast with Ayodele and Akinlana’s (2012) results that found there is not a direct relationship between writing apprehension and the students’ interest in writing.

A number of suggestions and recommendations are put forward in the literature in order to overcome and alleviate students’ writing anxiety. For instance, Tadesse (2013) proposes limiting the amount of error correction, welcoming novel ideas, providing adequate feedback and attempting to establish a good rapport as being helpful. In addition, he noticed that focusing exclusively on form would lead to the students’ demotivation. Hence, it can be inferred that during writing sessions teachers’ attention should primarily be focused on meaning instead of grammatical forms.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Fariba Mobini, University of Zanjan. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RK has suggested the title of the project and guided the research as the thesis supervisor, revised the entire manuscript, and re-written parts of it. NE carried out data collection and data analysis, she has also written the original draft. EM has read and commented on data analysis as well as the discussion part. HZ has reviewed and revised the statistics, methodology, and results sections based on the reviewers’ advice. He ran some new statistical tests and improved the rigor of the findings. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ayodele, K. O., and Akinlana, T. (2012). Writing apprehension and Nigerian undergraduates’ interest in dissertation’s writing: the moderator effects of self-efficacy, emotional intelligence and academic optimism. Afr. Symp. 12, 46–56.

Chasetareh, F., Barabadi, E., Khajavy, G. H., and Flett, G. L. (2023). Perfectionism and L2 achievement: the mediating roles of motivation and self-regulated learning among Iranian high school students. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 41, 3–21. doi: 10.1177/07342829221096916

Cheng, Y. S. (2004). A measure of second language writing anxiety: scale development and preliminary validation. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 13, 313–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2004.07.001

Comerchero, V., and Fortugno, D. (2013). Adaptive perfectionism, maladaptive perfectionism and statistics anxiety in graduate psychology students. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 12, 4–11. doi: 10.2304/plat.2013.12.1.4

Daly, J. A. (1978). Writing apprehension and writing competency. J. Educ. Res. 72, 10–14. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1978.10885110

Daly, J. A., and Miller, M. D. (1975). The development of a measure of writing apprehension. Res. Teach. Engl. 9, 242–249.

Dimond-Bayir, S. (2014). Unlock level 2: Listening and speaking skills student’s book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dobson, C. (2012). Effects of anxiety on the performance of students with and without learning disabilities and how learners can cope with anxiety at schools. (Master’s thesis), Northern Michigan University, Michigan.

Dudley-Evans, T., and St John, M. (2013). Developments in English for specific purposes: A multi-disciplinary approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erkan, D. Y., and Saban, A. İ. (2011). Writing performance relative to writing apprehension, self-efficacy in writing, and attitudes towards writing: a correlational study in Turkish tertiary-level EFL. Asian EFL J. 13, 164–192.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Su, C., and Flett, K. D. (2016). Perfectionism in language learners: review, conceptualization, and recommendations for teachers and school psychologists. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 31, 75–101. doi: 10.1177/0829573516638462

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., and Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 14, 449–468. doi: 10.1007/BF01172967

Ghorbandordinejad, F. (2014). Examining the relationship between students’ levels of perfectionism and their achievements in English learning. J. Res. Engl. Lang. Pedagog. 2, 36–45.

Ghorbandordinejad, F., and Farjad Nasab, A. H. (2013). Examination of the relationship between perfectionism and English achievement as mediated by foreign language classroom anxiety. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 14, 603–614. doi: 10.1007/s12564-013-9286-5

Gilman, R., and Ashby, J. S. (2003). Multidimensional perfectionism in a sample of middle school students: an exploratory investigation. Psychol. Sch. 40, 677–689. doi: 10.1002/pits.10125

Gould, J., (2012). Overcoming perfectionism. BookBoon. Available at: http://thuvienso.bvu.edu.vn/bitstream/TVDHBRVT/15275/1/Overcoming-Perfectionism.pdf

Hanna, K. (2010). Student perceptions of teacher comments: Relationships between specific aspects of teacher comments and writing apprehension. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of North Dakota.

Hewitt, P. L., Caelian, C. F., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Collins, L., and Flynn, C. A. (2002). Perfectionism in children: associations with depression, anxiety, and anger. Personal. Individ. Differ. 32, 1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00109-X

Hewitt, P. L., and Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 456–470. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

Hewitt, P. L., and Flett, G. L. (2002). “Perfectionism and stress processes in psychopathology” in Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment. eds. G. L. Flett and P. L. Hewitt (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 255–284.

Huang, H., Ding, Y., Zhang, Y., Peng, Q., Liang, Y., Wan, X., et al. (2022). Resilience and positive coping style affect the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and academic procrastination among Chinese undergraduate nursing students. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1014951

Inglés, C. J., García-Fernández, J. M., Vicent, M., Gonzálvez, C., and Sanmartín, R. (2016). Profiles of perfectionism and school anxiety: a review of the 2× 2 model of dispositional perfectionism in child population. Front. Psychol. 7:1403. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01403

Jebreil, N., Azizifar, A., Gowhary, H., and Jamalinesari, A. (2015). A study on writing anxiety among Iranian EFL students. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 4, 68–72. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.2p.68

Ĵosef, H.. (2001). Advance writing in English as a foreign language: A corpus based study of process and products. Available at: http://www.geocities.com/writing-site/thesis.

Kim, K. J. (2006). Writing apprehension and writing achievement of Korean EFL college students. Engl. Teach. 73, 135–160. doi: 10.15858/engtea.73.1.201803.135

Krause, K. L. (1994). The effect of goal-setting and planning on the writing competence of secondary school students. In: Paper presented at the Annual Conference, Australian Association for Research in Education, Newcastle, NSW.

La Rocque, C. L., Lee, L., and Harkness, K. L. (2016). The role of current depression symptoms in perfectionistic stress enhancement and stress generation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 35, 64–86. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2016.35.1.64

Larson-Hall, J. (2015). A guide to doing statistics in second language research using SPSS and R. Abingdon: Routledge.

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1991). Methods and results in the study of anxiety and language learning: a review of literature. Lang. Learn. 41, 85–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1991.tb00677.x

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1993). A student’s contributions to second-language learning. Part II: affective variables. Lang. Teach. 26, 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0261444800000045

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Lang. Learn. 44, 283–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x

Martens, R., Vealey, R. S., and Burton, D. (1990). “Development and validation of the competitive state anxiety inventory-2” in Competitive anxiety in sport. eds. R. M. Vealey and D. Burton (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics), 117–190.

Moradan, A., Khazenian, E., and Niroo, Z. (2013). The relationship between perfectionism and listening comprehension among EFL students of Kerman university. Int. J. Linguist. Commun. 1, 8–16.

Morris, L., Davis, D., and Hutchings, P. C. (1990). Cognitive and emotional components of anxiety: literature review and revised worry-emotional scale. J. Educ. Psychol. 73, 541–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.73.4.541

Nussinson, R., Häfner, M., Seibt, B., Strack, F., and Trope, Y. (2012). Approach/avoidance orientations affect self-construal and identification with in-group. Self Identity 11, 255–272. doi: 10.1080/15298868

Ogurlu, U. (2020). Are gifted students perfectionistic? A meta analysis. J. Educ. Gift. 43, 227–251. doi: 10.1177/0162353220933006

Patcht, A. R. (1984). Reflections of perfection. Am. Psychol. 39, 386–390. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.386

Pishghadam, R., and Akhondpoor, F. (2011). Learner perfectionism and its role in foreign language learning success, academic achievement, and learner anxiety. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2, 432–440. doi: 10.4304/jltr.2.2.432-440

Plonsky, L., and Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Lang. Learn. 64, 878–912. doi: 10.1111/lang.12079

Rabadi, R. I., and Rabadi, A. D. (2020). Do medical students experience writing anxiety while learning english as a foreign language? Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 883–893. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S276448

Riazi, A. M. (2016). The Routledge encyclopedia of research methods in applied linguistics. Abingdon: Routledge.

Rice, K. G., and Dellwo, J. P. (2002). Perfectionism and self-development: implications for college adjustment. J. Couns. Dev. 80, 188–196. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00182.x

Richards, J. C., and Schmidt, R. W. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics 4th Edn, London: Longman, an imprint of Pearson Harlow.

Roohafza, H., Afshar, H., Sadeghi, M., Soleymani, B., Saadaty, A., Matinpour, M., et al. (2010). The relationship between perfectionism and academic achievement, depression and anxiety. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 4, 31–36.

Saboonchi, F., and Lundh, L. G. (1997). Perfectionism, self-consciousness and anxiety. Personal. Individ. Differ. 22, 921–928. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00274-7

Saedpanah, E., and Mahmoodi, M. (2020). Critical thinking, writing strategy use, L2 writing anxiety and L2 writing performance: what are the relations? J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Learn. 12, 239–267. doi: 10.22034/ELT.2020.10683

Slade, P. D., and Owens, G. R. (1998). A dual process of perfectionism based on reinforcement theory. Behav. Modif. 22, 372–390. doi: 10.1177/01454455980223010

Sokolic, M. (2003). “Writing” in Practical English language teaching. ed. D. Nunan (New York: McGraw Hill)

Stoeber, J. (2012). “Perfectionism and performance” in The Oxford handbook of sport and performance psychology. ed. S. M. Murphy (New York: Oxford University Press), 294–306.

Tadesse, D. T.. (2013). Investigating writing anxiety of grade II students and its effects on their writing skill: The case of Boditti preparatory school. (Master’s thesis), College of Social Science and Humanities. School of Graduate Studies. Haramaya University, Harmaya, Ethiopia.

Tóth, R., Turner, M. J., Kökény, T., and Tóth, L. (2022). “I must be perfect”: the role of irrational beliefs and perfectionism on the competitive anxiety of Hungarian athletes. Front. Psychol. 13:994126. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.994126

Wang, Q., and Wu, H. (2022). Associations between maladaptive perfectionism and life satisfaction among Chinese undergraduate medical students: the mediating role of academic burnout and the moderating role of self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 12:5488. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.774622

Wu, R., Chen, J., Li, Q., and Zhou, H. (2022). Reducing the influence of perfectionism and statistics anxiety on college student performance in statistics courses. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1011278

Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: what does language anxiety research suggest? Mod. Lang. J. 75, 426–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1991.tb05378.x

Keywords: perfectionism, writing anxiety, L2 writing, IELTS academic essays, EFL learners

Citation: Khosravi R, Mohammadi E, Esmaeili N and Zandi H (2023) Perfectionism and writing anxiety as predictors of Iranian EFL learners’ performance in IELTS writing module: a multi-dimensional perspective. Front. Educ. 8:1108542. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1108542

Edited by:

Reem Rabadi, German-Jordanian University, JordanCopyright © 2023 Khosravi, Mohammadi, Esmaeili and Zandi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robab Khosravi, cmtob3NyYXZpQHpudS5hYy5pcg==

Robab Khosravi

Robab Khosravi Elham Mohammadi1

Elham Mohammadi1