- 1Department of Applied Health Science, School of Public Health, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, United States

- 2Department of Built Environment, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Greensboro, NC, United States

- 3Environmental Health and Disease Laboratory, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Greensboro, NC, United States

Background: Teaching children about healthy lifestyles in early care settings can contribute to children’s optimal health during the COVID-19 era; this is because children are vulnerable to communicable diseases in such settings. This study aimed to discover the activities that early care educators are implementing in their childcare settings to assist children become healthy in the COVID- 19 era.

Methods: An open-ended survey was sent to early care providers through anonymous links. The requirement for participation was being an adult aged 18+ years and an educator in early care settings. Responses from 45 female educators (n = 45) were received, and those of three participants were excluded because of not responding to any of the main questions. A constant comparative approach was used to categorize and organize participants’ narratives into themes.

Results: Thirty-four out of the 42 participants indicated that they did activities on hand washing and how to use hand sanitizer. Some participants indicated that hand washing increased in their childcare settings. Others did some of their instructional activities such as reading, painting, and eating snacks outside the classrooms. Participants indicated that they walked around their childcare with children several times for children to get fresh air outside. There were others who canceled extracurricular activities at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Others did not do any extra activities in their childcare settings during the COVID-19 era.

Conclusion: This study revealed teaching and related activities undertaken by the studied early care educators during COVID-19. It is recommended that higher education professors who train early care educators’ work with them to come up with health education activities that can help children obtain much-needed health knowledge and skills to ensure children’s optimal health during the COVID-19 era.

Introduction

COVID-19 and its stressors have changed the way we live and work. People made lifestyle changes to avoid catching this lethal disease. Educational settings were not excluded from these changes brought about by the viruses. Several schools were shut down, and online education became part of the teaching norm. The shutdown of schools throughout the world had a tremendous impact on families, educators, children’s schooling, mental health, learning, etc. (Huebener et al., 2021; Adams-Prassl et al., 2022).

Early childhood environment is important in children’s development as it increases young children’s exposure to imitate others’ behaviors. Children are also vulnerable to infectious diseases in such an environment, highlighting the necessary prevention efforts at an early age to protect early age children (Kendall, 1983; Haskins and Kotch, 1986; Uhari and Möttönen, 1999; Kotch et al., 2007; Grossman, 2012). Childhood is a critical phase that lays the foundation for a lifetime of health and well-being in children. What children experience during these formative years can exert a tremendous impact on their overall health and long-term growth. The early environment, including the quality of care, nutrition, and exposure to various factors, significantly shapes their physical, mental, and emotional development. Providing a nurturing and supportive environment during childhood promotes better health outcomes and sets the stage for healthy lifestyle choices and behaviors at an early age and into adulthood (Mollborn et al., 2014; Seabert et al., 2015). Indeed, a review of literature on childhood learning attest to the fact that it is early learning skills, which children receive in their early learning school environments, that are reinforced throughout their educational journey are known to be carried into adulthood (Seabert et al., 2015; Gordon and Browne, 2016). Such learning also shows that children who develop healthy lifestyle skills in childhood are more likely to avert risky behavior in their adolescent years and in adulthood (Hurrelmann and Richter, 2006; Seabert et al., 2015).

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the environment in which children learn (Masonbrink and Hurley, 2020; Obeng et al., 2022) and contributed significantly to how early care educators work in the environment (Obeng et al., 2022). Research on COVID-19 and classroom activities confirm the strong link between children imitating adults’ handwashing behavior (Obeng et al., 2022). Health skills and behaviors can be learned at an early age in children’s childcare years so that children can enter primary schools with healthy skills ready to learn.

There is a need for early educators to help children in early care to understand how their own actions and choices can help the children they teach to grow up strong and healthy. During this COVID-19 period, the need to help children understand healthful choices and actions is particularly critical for all families, especially, children in under-resourced communities where young children may be exposed to unhealthy lifestyle choices.

Indeed, the literature on children’s learning indicates that students learn better if they learn strong developmentally appropriate personal and social skills at an early age (Seabert et al., 2015; Obeng et al., 2022) and especially if such acquired knowledge is reinforced throughout childhood.

In view of the fact that past literature on children learning did not incorporate COVID-19 era issues into children’s classroom activities, it is crucial to find out the activities that early educators are implementing in their classrooms during this era.

Therefore, this study aimed to find out the activities that early care educators are implementing in their childcare settings to assist children in becoming healthy in the COVID-19 era.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study participants comprised a diverse group of early childhood educators actively working with children aged 5 years or younger. This research welcomed teachers from all demographic backgrounds, ensuring a broad representation of perspectives and experiences. As part of the study, we gathered valuable information about each teacher’s individual experiences, allowing us to understand the unique challenges and opportunities they faced while instructing the children. Additionally, we sought to grasp the dynamics of their classrooms by inquiring about the number of students under their care, enabling us to gain deeper insights into the learning environments and the individualized approaches employed by these dedicated educators. The rich diversity and range of experiences among the study’s participants provided comprehensive data of early childhood education during the critical phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The primary focus of the study was to examine the activities implemented by educators during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically emphasizing preventative measures in the classroom to mitigate the spread of the illness.

This research was approved by the author’s institutional Human Subject office on January 18, 2022. The study is framed within Bandura’s Theory (Bandura, 1986), the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT).

The theory indicates that people can acquire knowledge by imitating and observing others. Specifically, Bandura as notes, “most human behavior is learned observationally through modeling: from observing others one forms an idea of how new behaviors are performed, and on later occasions, this coded information serves as a guide for action” (Bandura, 1977, pp. 65). Via the above words, Bandura is proposing that observation, imitation and replication or emulation of the behaviors, emotional reactions and attitudes, and of other people in one’s environment, play principal and fundamental roles in why people learn and the way and manner in which they learn. Such models (the people from whom others learn, imitate, etc.) may include family members (parents, siblings) and caregivers, friends, school/class mates, teachers, among others. We framed our study within Bandura’s theory given our study’s amenability to the theory, and most importantly, the theory’s usefulness as a tool in helping us to conceptualize and formulate our research questions. By employing the theory (the Social Cognitive Theory), we were able to identify the health activities educators were doing in their group-care during the COVID-19 pandemic and the observations, modeling, and imitations that took place in the children’s behavior and learning experience during the pandemic period.

We used the above theory to conceptualize and formulate the research questions to help us identify what health activities educators are doing in their group care during the COVID-19 era, in particular, the observations, and imitations that have taken place in the children’s behavior during this period (Bandura, 1986).

Research questions for the study were developed by two experienced researchers with several years of doing qualitative and preschool classroom research. The questions were also informed by findings from previous scholarship on preschool health education (Hendricks, 1984; Hendricks et al., 1988; English and Hendricks, 1997; Wiley and Hendricks, 1998; Seabert et al., 2015; Obeng et al., 2022).

This qualitative study data was collected between January 2022 to January, 2023. Semi-structured open-ended questions were used for flexibility (Magaldi and Berler, 2020). We used open-ended surveys given how efficient such surveys are in reaching several potential participants without researchers finding a convenient time and place to interview them.

This technique also helped researchers uncover several activities that educators were doing in their childcare environment. No incentives were given to participants. The informed consent containing the purpose, the number of people taking part, risks and benefits of the study and how confidentiality was guaranteed was attached for participants to read before participating in the research.

The researchers developed links and sent them to three educators to distribute via an anonymous link to early care educators. They also distributed the links to educators who qualified to be participants based on the criteria for the research; being an educator who teaches children, 5 years and below, in an educational group setting.

The survey questionnaire was in two parts. Part one dealt with participant demographics, whereas part two, the main survey, contained open-ended questions that asked about educators’ activities in their childcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, part two contained questions related to handwashing (especially time devoted for handwashing for children in their classrooms during the COVID-19 era), children’s mask wearing in school and public, and advice that participants would give to their fellow educators during this COVID-19 period.

Researchers stopped at 45 because they reached saturation, in qualitative research, saturation is where researchers are not receiving new information from new participants to their study. In our case, educators were listing the same activities in their childcare settings after the researchers received 40 surveys.

Data coding and analysis

This study used Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) steps in coding and analyzing our date. In following QCA steps, the coders (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Wildemuth, 2016; Kibiswa, 2019):

1. Put the written narratives into one big document.

2. We used each individual teachers health activities they are doing in their early care environment for the analysis

3. We used the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) to develop categories of the activities that the educators do the most in their childcare environment

4. Each coder put the educators activities into categories

5. In the data coding process, we checked constantly and added new themes and after all the samples were coded, inter-coder agreement were done

6. The coders assess all the themes and agree on them

7. The coders came to conclusions on four major themes identified by the two coders;

8. And reported them as the study findings

The ‘demographic information’ part of the analysis involved reporting the educator’s number of years they had taught and the classes that they currently teach.

As stated above, we used Constant Comparative Method and the narrative approach to sort and organize our raw data into groups. This was done by identifying frequently occurring words and phrases in the data. We used a thematic approach because it allows flexibility in interpreting data. It also made it possible to analyze the large set of data (the narratives) into broad themes. We also looked at subthemes (where necessary) in the participants’ responses to our main questions.

Working within the narrative analysis approach meant that attention was focused on what participants actually wrote in the survey. Focusing on participants’ real responses gives the public (readers of this work) an opportunity to follow through the rationale behind our interpretations thereby giving authenticity and credence to our analysis (Riessman, 2008). Results of educator’s answers are detailed below.

Results

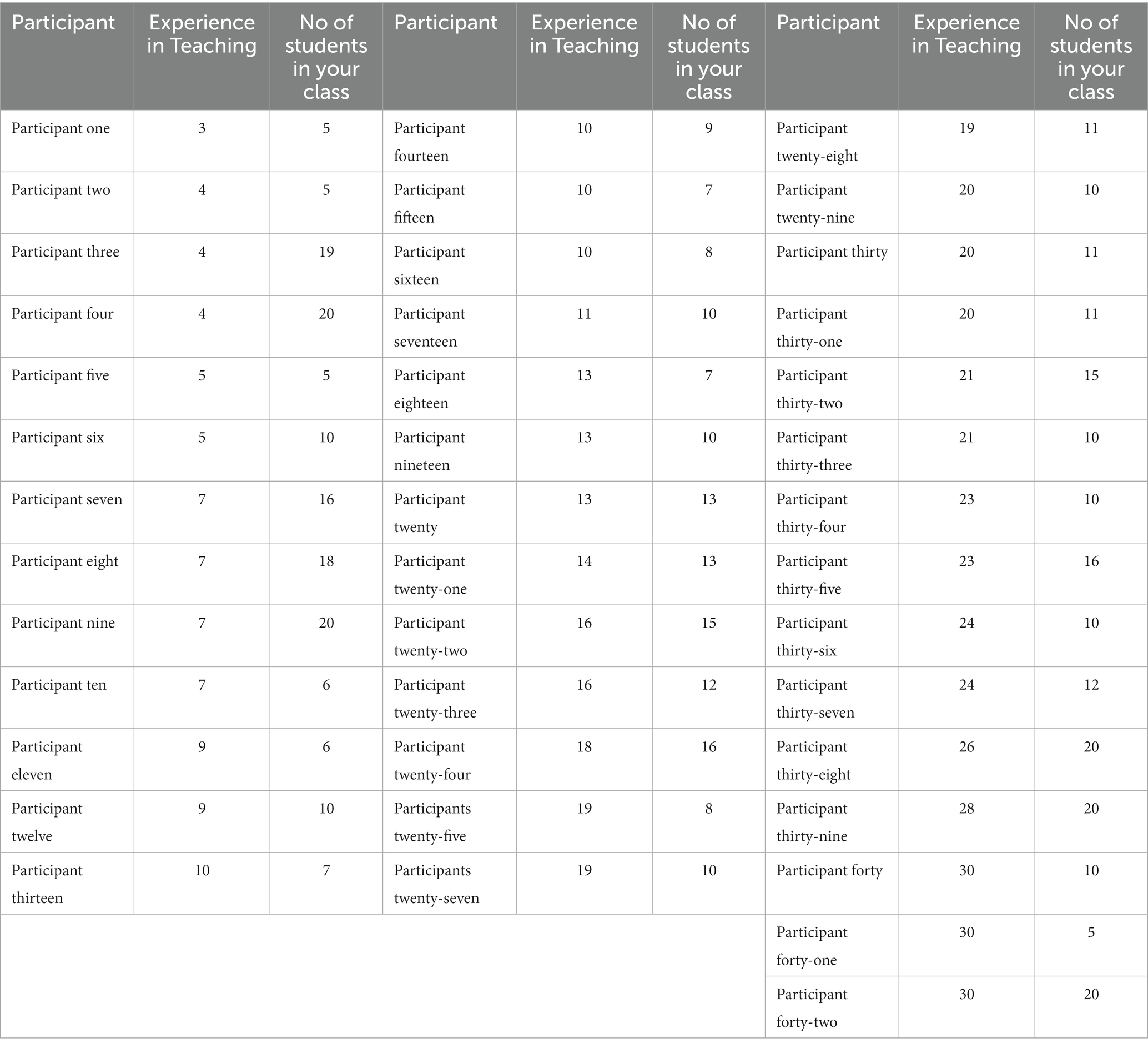

The demographic information about participants are in Table 1.

Four themes came out of the participant’s narrative; these are handwashing; cleaning of classrooms and toys; instructional planning; and advice for fellow educators. These themes can be found in Table 2.

Discussion

The narratives shared by the educators highlight their proactive measures in preventing the spread of the COVID-19 virus within their childcare environments. They actively engaged in activities aimed at maintaining a safe and healthy atmosphere.

Participants also provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of handwashing practices and the impact of repeated instruction by instructors. It was observed that students not only gained knowledge about proper handwashing techniques but also felt comfortable applying this knowledge in real-life situations. This accomplishment speaks volumes about the pedagogical competence exhibited by the teachers.

These findings align with Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory, which emphasizes the significance of social interactions, environmental factors, and individual behavior within the context of learning. The positive outcomes observed in this study reinforce the theory’s assertion that learning is facilitated through dynamic and reciprocal interactions among individuals, their environment, and their behaviors within the social domain.

Specifically, the teachers’ proactive implementation of various activities and best practices within the classroom setting aligns with Bandura’s theory of observational learning, where children tend to imitate behaviors they observe in their surroundings. Notably, the policies promoting and encouraging handwashing, coupled with careful monitoring of handwashing directives, established a positive classroom ecosystem that fostered behaviors worth emulating. By creating such an environment, the teachers effectively nurtured a culture of health and hygiene among the children, influencing them to adopt and practice essential handwashing habits.

The study sheds light on the instructors’ stringent implementation of hand sanitizer usage requirements within their classrooms. Specifically, a strong emphasis on hygiene is evident in practices such as requiring parents to use hand sanitizer when signing in or out their children, as well as when volunteering in the classroom. The use of the phrase “supposed to” underscores the non-negotiable nature of this hygienic protocol, leaving no room for non-compliance.

Furthermore, participants’ responses indicate a prioritization of handwashing with soap and water over the use of hand sanitizer. This aligns with the guidance provided by healthcare professionals, as emphasized by Scripps Health (2020).

According to their recommendations, proper and regular handwashing remains the most effective method for eliminating various viruses, including the flu and COVID-19 (Prather et al., 2020; Salido et al., 2020).

By highlighting the consensus among healthcare professionals, this study supports the notion that handwashing should be the preferred hygiene practice while acknowledging the role of hand sanitizer as an additional measure in specific situation (Scripps Health, 2020).

In the study, a participant provides information regarding the time period and activities whose performance required handwashing. The expression, first thing in the morning, presupposes the seriousness attached to handwashing itself and to the time frame of its enactment, prior to the commencement of any other class activity. The individual activities mentioned, lunch, playing, outside or in the sensory area, and with the dough, are all group activities that are potential virus spreader acts. The fact that handwashing is done before and after these activities signify the seriousness that the teacher attaches to COVID-19 prevention and her desire to ensure that the children stay healthy.

In Excerpt 4, the word definitely suggests absoluteness with regard to the hygienic method observed in the participant’s classroom. Like in Excerpt 3, the participant in Excerpt 4 lists activities (restroom usage, lunch, and snack time) whose performance is corporate and for whose enactment handwashing is required. The teacher also indicates availability of space (bathroom) and an item (sink) needed to make handwashing possible.

Not, only do some participants educate us about handwashing in general, they also take us through their instructional and/or pedagogical strategies undertaken to ensure the children’s safety and theirs. Thus, we learn about prevention and protection against COVID-19 as they relate to participants’ school’s environment, including the classroom, playground, restroom, etc. ecologies. We also observe the above-mentioned activities blending into a web of constellation whose purpose is school (including classroom) safety with the view to ensuring that children obtain optimal health.

Important health concepts learned from this study are the importance teachers attached to cleanliness, who was responsible for cleaning, which items were cleaned and the anticipated health benefits of the cleaning (Obeng-Gyasi et al., 2018). The fact that the teachers themselves took charge of the cleaning, especially, cleaning up immediately after students’ sneezed, and most importantly, cleaning the cribs and students’ cups points to competence in the management of the COVID-19 by the teachers. They took the children’s welfare and health needs seriously and made every effort to prevent the occurrence of the disease in their childcare settings.

A methodical observation of the activities done outside the classroom–reading to the children in a small group, doing painting activities, exercising with the children by walking around their childcare’s premises several times with them, and sometimes eating snacks outside–point to major educational activities being done outside the classroom. What one learns from the above activities is the rationale for doing them in the stated context. By performing the activities, the teachers sought to create an environment whereby there would be social distancing and the children receiving fresh air. Thus, the process employed by the teachers was healthful and boded well for the attainment of optimal health.

Only eight educators indicated they neither did any extra activities in their classroom nor planned any activities in health education for their students during this COVID-19 era.

From the majority of the educator’s responses, we gather that the teachers looked at their job as rewarding, something that points to job satisfaction and/or love of and for their jobs. They admitted that the pandemic made their job difficult given the age of the children, and children’s sharing nature. Specifically, the conditions obtaining in their classrooms made efficiency a challenge and yet they noted that they gave off their best to ensure optimal educational output as well as optimal health for the children. Two things they did to ensure optimal output and optimum health in the classrooms; they did these by effectively assessing the level of children’s retaining handwashing knowledge skills, and then aiding the children when necessary. It was also noted that educators were effectively assessing the children’s level of retaining the health education knowledge and skills in their early care environment.

This is in line with developers of early care setting activities/curricula. They noted that health education curricula and associated activities development would be effective if children understood the activities and were able to use the knowledge and skills (Hendricks, 1984; National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2003; Seabert et al., 2015). From the educators’ narratives, the activities planned were age appropriate and they had the appropriate resources for the implementation in their childcare settings.

Scholarship on children’s classroom activities provides a solid insight into preschool health and a foundation for research in early care classroom setting activities (Hendricks, 1984; English and Hendricks, 1997; Wiley and Hendricks, 1998; Seabert et al., 2015; Obeng et al., 2022). The surveyed educators work confirm that planned instructional activities (such as those in the current study), implemented with the right tools and qualified personnel, has a strong potential to motivate children to increase their health knowledge and skills. However, this study also discovered that some of the educators who completed the COVID -19 research surveys about health activities in their early care classroom/settings did not do and did not have planned activities on health education for their students and were not encouraging hand washing as much as is needed. Given this dearth of planned health education activities in some of the educator’s classroom settings, it is anticipated that building appropriate planned curriculum activities for children and developing efficient evaluation and assessment strategies to measure the impact of such activities will benefit the children’s learning and increase their health knowledge and skills. In addition, planning the appropriate classroom activities and putting in place assessment models will help improve teachers’ professional competence, which will in turn help improve the children’s health.

There was a notable trend observed among teachers, where those with less experience tended to engage in fewer activities related to pandemic prevention. This pattern may have been influenced by their relative lack of expertise in dealing with such extraordinary circumstances and catastrophes. In contrast, more experienced teachers appeared to be better equipped to address the challenges posed by pandemic, likely due to their prior encounters with viral outbreaks and other health exposures before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their previous experiences likely played a significant role in shaping their preparedness and response strategies during the unprecedented times of COVID-19.

In all, obtained results in this study are influenced by various factors, creating a multifaceted picture. One crucial aspect we believe has contributed significantly is their training on COVID-19 pandemic and health education, combined with valuable classroom experiences that have enriched their background knowledge and skill set. Consequently, these results can be seen as a testament to the ongoing educational efforts at their institutions, as well as the information provided through government and local media sources.

Recommendations

Based on the comprehensive study results, several specific recommendations emerge to enhance health and safety measures in early childhood education settings. One crucial aspect is hand hygiene, where educators reported engaging in activities related to the use of hand sanitizers and an increase in their usage in their classrooms. To bolster these efforts, it is vital to ensure the wide availability of hand sanitizers in addition to soap and water. Moreover, providing more targeted training on infectious diseases and appropriate hand sanitizer use, including the correct amount and distribution on hands, can significantly improve hygiene practices and reduce the risk of infections.

Another critical area identified in the study pertains to classroom and toy cleaning. Educators reported maintaining the practice of frequent toy cleaning and providing instructions on proper toy usage. To maintain a safe environment, it is recommended to continue these cleaning routines and reinforce instructions for toy handling, which can effectively limit the spread of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in early childhood education settings.

Additionally, the study highlights the positive impact of outdoor activities on limiting the spread of infectious diseases like COVID-19. To promote a healthier classroom environment, it is encouraged for educators to continue incorporating outdoor learning experiences into their instructional planning. Utilizing outdoor spaces allows for better ventilation and social distancing, further reducing the risk of transmission.

Furthermore, the study underscores the value of support and advice for fellow educators during the pandemic. To foster a sense of community and improve health practices in the classroom setting, it is highly recommended for teachers to form support groups where they can openly discuss challenges, share experiences, and collaboratively develop best practices. These support networks will not only enhance educator well-being but also contribute to better safety protocols and educational outcomes for young learners.

Future work

The study followed a qualitative approach involving open-ended questions that focused on educators’ activities in childcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we inquired about practices such as hand washing, mask wearing in schools, and advice shared among fellow educators. Notably, breathing exercises and relaxation techniques with children were not mentioned by the participants during this study. However, we find these aspects intriguing and believe that a future targeted study addressing these specific practices would provide valuable insights.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations; the fact that the study used open-ended survey indicates that participant’s non-verbal actions/activities such as facial expressions, gaze and gestures could not be observed and incorporated into this study despite such non-verbal activities being an essential fabric and facets of human communication (Kendon, 1967; Craig and Washington, 1986). In addition, the snowballing approach of data collection, where recruited participants invite others, may have contributed to educators working in the same facility completing the survey. Finally, the survey was conducted online, meaning those who did not have access to computers with internet could not participate. However, this study was about educators’ teaching activities during the COVID-19 era and the results of the study captured some of such activities that could be used by other educators.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study details early care educators’ activities during the COVID-19 in their settings. The study points to the need for educators to come up with health education activities that contain efficient evaluation/assessment components as well as implementation tools that can help all young children to obtain much-needed health education knowledge and skills. It is also recommended that higher education professors who train early care educators work with them to develop health education activities that can help most children obtain much-needed health knowledge and skills during this COVID-19 time period and beyond.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were reviewed and approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol No. 13999). The studies were conducted in accordance with local and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CO: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing–original draft preparation, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. CO and EO-G: writing–review and editing and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., and Rauh, C. (2022). The impact of the coronavirus lockdown on mental health: evidence from the United States. Econ. Policy 37, 139–155. doi: 10.1093/epolic/eiac002

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 23–28.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Craig, H. K., and Washington, J. A. (1986). Children's turn-taking behaviors social-linguistic interactions. J. Pragmat. 10, 173–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(86)90086-X

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (grounded theory). 17. New Delhi: Taylor and Francis eBooks DRM Free Collection. p. 364.

Gordon, A., and Browne, K. W. (2016). Beginnings & beyond: Foundations in early childhood education. Boston, MA: Cengage learning.

Grossman, L. B. Infection control in the child care center and preschool. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; (2012).

Haskins, R., and Kotch, J. (1986). Day care and illness: evidence, costs, and public policy. Pediatrics 77, 951–982. doi: 10.1542/peds.77.6.951

Hendricks, C. M. (1984). Development of a comprehensive health curriculum for head start. Health Educ. 15, 28–31. doi: 10.1080/00970050.1984.10614430

Hendricks, C. M., Peterson, F., Windsor, R., Poehler, D., and Young, M. (1988). Reliability of health knowledge measurement in very young children. J. Sch. Health 58, 21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1988.tb05801.x

Huebener, M., Waights, S., Spiess, C. K., Siegel, N. A., and Wagner, G. G. (2021). Parental well-being in times of Covid-19 in Germany. Rev. Econ. Househ. 19, 91–122. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09529-4

Hurrelmann, K., and Richter, M. (2006). Risk behaviour in adolescence: the relationship between developmental and health problems. J. Public Health 14, 20–28. doi: 10.1007/s10389-005-0005-5

Kendon, A. (1967). Some functions of gaze-direction in social interaction. Acta Psychol. 26, 22–63. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(67)90005-4

Kibiswa, N. K. (2019). Directed qualitative content analysis (DQlCA): a tool for conflict analysis. Qual. Rep. 24, 2059–2079. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3778

Kotch, J. B., Isbell, P., Weber, D. J., Nguyen, V., Savage, E., Gunn, E., et al. (2007). Hand-washing and diapering equipment reduces disease among children in out-of-home child care centers. Pediatrics 120, e29–e36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0760

Magaldi, D., and Berler, M. (2020). “Semi-structured interviews” in Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. eds. V. Zeigler-Hill and T. K. Shackelford (Berlin: Springer), 4825–4830.

Masonbrink, A. R., and Hurley, E. (2020). Advocating for children during the COVID-19 school closures. Pediatrics 146:e1440. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1440

Mollborn, S., James-Hawkins, L., Lawrence, E., and Fomby, P. (2014). Health lifestyles in early childhood. J. Health Soc. Behav. 55, 386–402. doi: 10.1177/0022146514555981

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2003). Early childhood curriculum, assessment, and program evaluation: Buildingan effective, accountable system in programs for children birth through age 8. Position statement. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Obeng, C., Amissah-Essel, S., Jackson, F., and Obeng-Gyasi, E. (2022). Preschool environment: teacher experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:7286. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127286

Obeng, C., Slaughter, M., and Obeng-Gyasi, E. (2022). Childcare issues and the pandemic: working Women’s experiences in the face of COVID-19. Societies 12:103. doi: 10.3390/soc12040103

Obeng-Gyasi, E., Weinstein, M. A., Hauser, J. R., and Obeng, C. S. (2018). Teachers’ strategies in combating diseases in preschools’ environments. Children 5:117. doi: 10.3390/children5090117

Prather, K. A., Wang, C. C., and Schooley, R. T. (2020). Reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science 368, 1422–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6197

Salido, R. A., Morgan, S. C., Rojas, M. I., Magallanes, C. G., Marotz, C., DeHoff, P., et al. (2020). Handwashing and detergent treatment greatly reduce SARS-CoV-2 viral load on Halloween candy handled by COVID-19 patients. Msystems 5, e01074–e01020. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.01074-20

Scripps Health (2020). Handwashing or Hand Sanitizer? Coronavirus https://www.scripps.org/news items/6991-handwashing-or-hand-sanitizer (Accessed June 23, 2023).

Seabert, D., Pateman, B., Symons, C., and Telljohann, S. (2015). Health education: Elementary and middle school applications. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Uhari, M., and Möttönen, M. (1999). An open randomized controlled trial of infection prevention in child day-care centers. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18, 672–677. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199908000-00004

Wildemuth, B. M. (2016). Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. Santa Barbara, CA: Abc-Clio.

Keywords: health activities, COVID-19, childcare settings, educators, health education

Citation: Obeng C and Obeng-Gyasi E (2023) Activities that early care educators are implementing in their childcare environments during the COVID-19 era. Front. Educ. 8:1255172. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1255172

Edited by:

Jihea Maddamsetti, Old Dominion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Gül Kadan, Cankiri Karatekin University, TürkiyeAlessandro Porrovecchio, Université du Littoral Côte d’Opale, France

Copyright © 2023 Obeng and Obeng-Gyasi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cecilia Obeng, Y29iZW5nQGl1LmVkdQ==

Cecilia Obeng

Cecilia Obeng Emmanuel Obeng-Gyasi

Emmanuel Obeng-Gyasi