- San Francisco Waldorf School, San Francisco, CA, United States

This paper describes a moral education arising from artistic choices and problem solving from out of one’s soul, which lead to a way of taking interest in the world and to being flexible in one’s views. Making choices creatively, imaginatively becomes a habit through a truly artistic education. So does maintaining an inner confidence Through Waldorf education, students choose to nourish their soul; to hold themselves accountable; to have the freedom to realize knowledge from risk and failure; and to experience thinking not just in their heads, but also in their hands or bodies, depending on the medium. To be able to accomplish all this integration of experiences through the creative process and offer something beautiful back to the world is proof enough of their innate wisdom. This paper examines the role of imagination and the arts that rely on imagination as catalysts for moral intelligence. From there, a discussion on the place of morality in educating for a democratic people and as a goal of Waldorf education in general is examined.

About Waldorf education

Waldorf education is based upon the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner. It focuses on an imaginative approach to learning and aims to develop holistic thinking that includes creative as well as analytic thought. The arts are central to the curriculum, instruction and school design. In the words of Henry Barnes, founding teacher of the first Waldorf school in America (New York, 1929), Waldorf Education aims to develop “head, heart, and hand.” The ultimate goal is to provide young people with the basis to develop into free, moral and balanced individuals (Oberman, 2007).

In Waldorf education’s origins, the seed of moral education

Michelle Fine, a speaker at the American Educational Research Association’s Annual Conference in 1996, was asked how she viewed Waldorf education. She declared it to be a “special philosophy for special children.” Afterwards, she presented on imagination and social action, not realizing that she was echoing the thoughts of Waldorf education’s founder, Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), who determined that thought, imagination and social action were the vehicle and goal of Waldorf education. Steiner never thought of Waldorf as special, but as a needed reform. He created it for the children of the Waldorf tobacco factory’s workers, hoping to produce a “Volks” pedagogy, a schooling of the people for the people, bridging classes that had been separated by industrialization (Oberman, 2007).

After the millions of deaths in World War I, many pondered what could be done to prevent such a tragedy from ever happening again. At the Waldorf-Astoria company in Germany, visionary director Emil Molt enlisted the help of philosopher and natural scientist Rudolf Steiner. Molt asked him to come up with a new way of educating children—preparing them for life in a changing world while also enabling them to develop their own strong sense of moral values, along with the capacity to think for themselves. He reasoned that the only way to stop history from repeating itself was for young people to develop a conscience and become true individuals with the capacity to judge independently.

Rudolf Steiner developed a holistic approach. He reasoned that children are not small adults, as was the customary view at the time, but suggested that the curriculum should tie into the natural development of the child’s body, mind, and spirit. Steiner created an arts-integrated, developmentally appropriate curriculum, putting his ideas to the test at the factory school, and honed and refined the curriculum over the next few years. In the 100 years since, Waldorf schools around the world have used and further developed this curriculum.

The arts and moral education

Recently, representatives of our high school participated in a high school fair to introduce public and parochial school students to the independent high schools in the city. One of the 8th grade parents there told me that “the word on the street is that graduates of Waldorf are all artists.” Not sure in the din of the room how to hear and understand that comment, I spoke about the breadth of the curriculum and how the students not only learn art, but learn through art. She was satisfied, but I continued to think about her words.

When parents visit their child’s Waldorf school, they cannot help but note how pervasive art is in the school. Beautiful blackboard drawings in every class stand out at once. Then there are the carefully illustrated main lesson books for each subject, and the colorful paintings and drawings adorning the walls. The profusion of beauty might beg the question: How does this “artistic education” actually work? How does learning occur through this art? What, exactly is it that the students learn?

Imagine a child seated before an empty paper. Holding a paintbrush, she confronts a kind of question given by the outside world: What shall she do with the colors, the page, the brush? It is an extrinsic “problem” that requires an interior search to solve. The young artist is asked, simply by her desire to produce something and by the materials in front of her, to recognize her emotions, often without full consciousness of them, and to pay attention while choosing what to do next on her painting. In the act of choosing how to proceed, whether that be in painting, clay modeling, or writing poetry, the artist creates, not only the piece of art, but also a certain harmony between self and world. Through the inner courage to plunge in and create, through concentrated effort and the joy of being lost in the process of creation, the young artist has opened herself to discovery and to satisfaction in her personal strength and ability to opt for just the right color (or word or movement or structural form) to make things right in her world, even if only for a moment.

In the Waldorf school, we recognize this moment—in its many iterations—as a kind of moral education. Because the students must confront myriad possibilities and find their own artistic choice, while solving the problem of what and how to create from out of their soul, they begin to take an interest in the world and to become ever more flexible in their views. In an artistically-based education, the practice of making choices, artistic and otherwise, becomes a way of life, as does maintaining the inner confidence to do so. The grade school years bear witness to the growth of these capacities while in the high school they develop into a direct correlation between the students’ knowledge of themselves and their search for their place in the world. Our students know that finding meaning in their lives is as important, if not more important, than their academic advancement. In other words, they learn through their inner explorations, in the arts as elsewhere, what is necessary for them to nourish their souls. Here we come to the true gift of the arts as they are experienced within the school context: the exercise of inner freedom and its flip sides, responsibility and accountability.

In our high school, we observe that as students make choices, they also begin to hold themselves accountable. They learn through the freedom offered by the artistic challenges they face, to realize knowledge by taking risks and by handling failure and they experience thinking not just in their heads, but also in their hands or bodies, depending on the medium. Because they accomplish a fulfilling integration of experiences through the creative process and in the end are potentially able to offer something beautiful back to the world, the students are given the possibility to experience their innate wisdom. By valuing that wisdom and understanding the enormous significance of the arts for their future, the faculty has a simple role in this process: to advise in practical matters of creation and to remove obstacles that might inhibit the students’ creative process.

Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Waldorf education, noted that one of its fundamental goals is to educate students “who are able, of themselves, to give purpose and direction to their lives.” To do this requires a pedagogy that allows for the greatest freedom of thought. Central to that pedagogy is the Steinerian conception of human development, which is based on a holistic view of the human being as composed of body, soul, and spirit, all of which need to be considered in the educational process. Further, the three basic soul capacities of thinking, feeling, and willing must all be enlivened, even educated, in order for the students to be fully in charge of their lives as adults. Within the context of these three capacities lies the imagination, which can be seen as a mediator between each of the three capacities. It is the place, as Douglas Sloan of Columbia Teachers College puts it, where the realms of thinking and willing are joined and unified (1983). This view corresponds to that of Dewey (1934), who wrote, “…imagination is the medium of appreciation in every field. Were it not for the accompanying play of imagination, there would be no road from a direct activity to representative knowledge; for it is by imagination that symbols are translated over into a direct meaning and integrated with a narrower activity so as to expand and enrich it.”

On cultivation of imagination in the Waldorf school

There are many methods employed in Waldorf education that are not exclusive to its practice, but can be found in one way or another in other educational settings. But one that is relied upon by all grade school teachers, and even into the high school, has as its goal to help students toward developing the faculty of free imagination. So, for example, teachers generally tell stories without also showing printed pictures; their words, deeply imagined by the teachers are built in the ineffable space between teller and listener, provide raw materials for the work of the children’s own imaginations. Each child enlivens the story with his or her own internally-created images.

Their imaginations fired, the students produce their own artistic workbooks, called main lesson books, which are their self-created textbooks and records of each course. Playfulness is encouraged in them, because Waldorf teachers believe that imaginative wonderings can often be just as educational as objective facts and conclusions, if not more so (Oppenheimer, 1999).

The use of “unfinished” playthings in the kindergarten, such as dolls with no expressions or tree stumps and pinecones for building, allow the youngest children to exercise their imaginations in order not only to bring the objects to life but also to imbue them with feelings in the case of the dolls or with whatever function is need in the case of the nature-objects.

It is important to note that not only is imagination cultivated within the students, but also the method of teaching itself is fundamentally imaginative. Teachers are trained in a transformative way through immersion in the arts and continue to practice artistic work with their colleagues during weekly faculty meetings (Lutzker, 2022a). Teachers employ artistic methods in the construction of their lessons and in the delivery, utilizing storytelling, drama, and carefully chosen verbal images in lectures and explanations in order to awaken the imaginations of the students in age-appropriate ways from the earliest years through high school.

Educating the imagination through the arts

When something is defined through its wholeness, it is not always easy to find the best perspective to present it. Maybe it is enough as a beginning to see the students happily at work: first graders singing their counting song in the rosy glow of their first classroom; fifth graders eagerly raising their hands, fully engaged in their Spanish lesson; sixth graders repeating the eurythmy form, however self-consciously, because they are challenged to get it right; kindergarteners digging all together, marveling at how deep they can go as a team. Then I remember that at whatever stage—the active physical learning stage of the youngest children, the feeling and imagination-centered learning of the grade school classes, the search for both inner and outer truth as the thinking matures in the high school—at each stage, the teachers aim to build the capacities of their students, helping them to love to learn, even as they practice skills and guide the discovery of knowledge. This is a sacred task, and its importance leads to constant examination of the work.

Teaching as an art means that teachers provide a life-filled context for learning by creating an aesthetic environment that appeals to children’s sense of beauty and order. Within the classroom, in an age-appropriate manner and throughout the day, the rhythms of sound and movement are coordinated in stories, songs, and poetry, so that the children’s imaginations are engaged, and subject matter is made more vivid (see Lutzker, 2022b). At the same time, teachers help their students become more fully involved in the educational process by synchronizing their methods with the rhythms of the children’s unfolding capacities (Easton, 1995).

At every stage in the development of the whole person, the arts play a critical role. Waldorf educators, knowing the importance, encourage artistic activity, which demands disciplined coordination of the students’ ability to think, feel, and do. Specific arts such as choral singing, group recitation of poetry, orchestral music, dance, drama, and eurythmy also develop the ability to collaborate with others. Children learn to experience the world more keenly as they strive to express themselves through various artistic disciplines. Their perception, imagination, insight, and creative thinking are cultivated by the demands of artistic work (Easton, 1995). The arts are seen as a vehicle for awakening moral thought and action, even though the relationship between art and morality remains a vexed one. Is there value in speaking of art and morality together in the educational context?

The Waldorf philosophy: based on an in-depth understanding of human development

Waldorf education places human development at the center of its work and curriculum. The teachers view each student as an evolving human being composed of body, soul, and spirit, all of which their pedagogical practices nurture. Teachers engage the children in the context of their own stage of development, with the understanding that subjects must be brought to them in different ways at different ages. While tailoring the curriculum and methodology to the age of their students, Waldorf teachers address the three “soul capacities” of thinking, feeling, and willing, essential components in Waldorf education, holistically in every lesson. These capacities are also highlighted sequentially as the children grow and develop, with willing dominating learning through imitation in the first 7 years. Feeling is particularly prominent in the grade school years, ages 7–14, approximately, and thinking and developing one’s capabilities of judgment play a central role in the high school, ages 14–18. It can be noted that there is no strict dividing line between “stages” of development. For example, in the overlapping middle school years, thinking becomes increasingly important.

Between birth and age seven, children learn mainly through imitation, which is a phenomenon every parent observes with delight in their young children. Because of the openness, one might even say porousness of the youngest children’s inner beings, the atmosphere surrounding them is most health-giving if filled with beauty, morality, and role models worthy of imitation. At this age the children need warmth and protection to develop their capacities in a natural, supportive, non-competitive and free atmosphere for their creative play and practical work, which consists of archetypal life activities, such as sweeping, bread-making, and cleaning.

Once ready for learning as such, children between the ages of 7 and 14 learn best from teachers striving to reach the ideal of loving and consistent authorities who embrace the world with interest. At this age, teachers present an array of subjects in an artistic way, as in the imaginative storytelling described earlier, in order to engage the children’s feelings so that they will value the world and want to master the basic academic, artistic, practical, and physical skills they will need for life.

For the high school students, the curriculum is grounded in the classics and engaged in the modern world, with academic courses that expose students to the great ideas of humankind, the events that shaped civilizations, the beauty of mathematics, the power of the arts, and the phenomena of the natural world. Through a variety of subjects and disciplines, Waldorf students have the opportunity to discover their own unique strengths and talents, giving them the self-confidence to succeed in all areas of their education.

With an emphasis on ethical values and social responsibility, Waldorf education has the goal of helping students to become a force for transformation in the world. The entire Waldorf approach emphasizes experiential learning. For example, by using primary sources instead of textbooks, students become independent thinkers with strong critical reasoning skills. Scientific study, based on the experience of the phenomena the students are faced with, includes hands-on exploration of chemistry, biology, and physics, giving students a comprehensive understanding of the scientific processes at work in the world,

True education is transformative, and the Waldorf curriculum is designed to support the students in accomplishing this, each in their own way. Through their 4 years of the high school experience, students undertake a journey of discovering themselves and the world around them that allows for authenticity and creativity and results in joyful accomplishment. Students learn that understanding and success come from what they make of each new situation and environment; they see how it changes them, and how they in turn can act in the world out of their ideals. The goal is for young people to connect with their interests and passions, acting out of inner conviction, guided by their moral compasses, toward their own fulfillment and the world’s benefit.

The arts and practical work are the bedrock from which Waldorf education nourishes creativity, thinking, the feeling life, self-discipline, moral judgment, and health in its students.

Premises on art and morality

Plato wrote often about art, sometimes in a curmudgeonly, censorious way, but ultimately with the greatest respect for the virtues of art. In the Republic, Plato put forward a reverential feeling toward art that persists even today despite the sometimes-cynical outlook of postmodernism. Indeed, throughout Plato’s artistically envisioned philosophy runs the moral, educational, and political significance of art (Allen, 2002).

Many modern thinkers, including the late novelist Gardner (1977), who claimed that art is essentially and primarily moral, life-giving, both in its process and in what it says (p. 15):

True art is by its nature moral. We recognize true art by its careful, thoroughly honest search for and analysis of values. It is not didactic because, instead of teaching by authority and force, it explores, open-mindedly, to learn what it should teach. It clarifies, like an experiment in a chemistry lab, and confirms…moral art tests values and rouses trustworthy feelings about the better and the worse in human action (Gardner, 1977, p. 19).

Here Gardner echoes Dewey and foreshadows both Eliot Eisner and David Swanger, who agree on the open-ended form of artistic endeavor and its place in education. Swanger (1985) offers an elegant and convincing argument for the necessity of both aesthetic and moral education as means of fulfilling our nation’s ideals of liberal education. He begins by deconstructing the long-held notion that art and morality are inseparable and posits instead that both share certain characteristics that make them essential to human life and understanding. He reframes the debate, based on the “principle of ambiguity” to be not about the inextricability of morality and art but rather about the confusion between perception, learning to see aesthetically, and morality. Swanger notes that although the criteria of the two realms are distinct—justice in the case of morality and aesthetics in the case of art—there are parallels in the process of judging each, specifically “open form” and “reciprocity.” These terms can also be understood as “ambiguity” and “empathy.” In the case of solving a moral dilemma or of aesthetic judging the process is not tied to the subject or substance under consideration, but it is, rather, engaged in understanding, judging, and valuing. In terms of education the fundamental nature of these processes can be seen through the value our society places on both art and justice, but even more importantly, on the process of judgment intrinsic to each.

Rethorst (1997) quotes Iris Murdoch, who says that “teaching art is teaching morals,” as he builds a case that both art and morals are “good for the soul,” and, furthermore, that both are fundamentally enterprises of the imagination. Rethorst finds support for these contentions in the work of Mark Johnson, who demonstrates in Moral Imagination: Implications of Cognitive Science for Ethics, that intensive and comprehensive imagining is essential to a person’s goodness. Citing poets like Shelley and Coleridge and theorists like Kant and Dewey, Rethorst broadens the definition of aesthetic experience to include many educational opportunities and contexts; imagination can be freed in any and every classroom and outside of the classroom as well. However, students must be fully engaged, their imaginations active, in order to realize the best of moral education. They are the ones who take an active role in developing their own understanding, which is how a moral sense becomes one’s own, and pedagogical approaches that call for or impose morally correct interpretations are to be avoided in Rethorst’s view.

Thus, we have encountered clear and cogent arguments for the correlation of art and morality and for their dual presence in education. Moreover, imagination repeatedly emerges as the vehicle, indeed the sine qua non of artistic work and of the appreciation of art. Art is characterized by open-ended processes and a certain unavoidable ambiguity. These aspects of aesthetic experience make possible what Swanger terms the parallel understanding of morality, with its basic component, justice. All of which point back to the holistic impulse of an education centered in the full dimensionality of the arts and artistic expression (cf. Camus, 1995; Lutzker, 2022a,b,c).

Arts and social justice

Justice is a major motivation behind the passionate writing of the activist actress Brawley (2009) who declares that “arts education is a matter of social justice” and that “It will save the world.” Brawley calls for more studies to help prove her point that arts education can be a determining factor in rescuing young people from the desperation of poverty, but also cites some recent work from the Maine Alliance for Arts Education that demonstrates arts education helping students succeed while at the same time reducing juvenile crime.

The Maine Alliance for Arts Education’s Advocacy Handbook, which also cites Shirley Brice Heath’s work, goes on to mention two studies—one from UCLA and one a collaboration between the U.S. Department of Justice, National Endowment for the Arts and the advocacy group, Americans for the Arts. Both studies support the social value of arts education:

The facts are that arts education…

[1] makes a tremendous impact on the developmental growth of every child and has proven to help level the “learning field” across socioeconomic boundaries (Involvement in the Arts and Success in Secondary School, James S. Catterall, The UCLA Imagination Project, Graduate School of Education & Information Studies, UCLA, Americans for the Arts Monograph, January 1998).

[2] has a measurable impact on youth at risk in deterring delinquent behavior and truancy problems while also increasing overall academic performance among those youth engaged in after school and summer arts programs targeted toward delinquency prevention (YouthARTS Development Project, 1996, U.S. Department of Justice, National Endowment for the Arts, and Americans for the Arts).

Education toward freedom: a moral choice?

Dewey offers what he calls a superficial explanation for democracy’s devotion to education, that is, that education is necessary for the success of a government that relies upon popular suffrage. Because democracy is not imposed upon individuals by external authority, but rather is dependent upon the people’s inner resources, these must be cultivated through education (Dewey, 1916, p. 83). These thoughts seem to be irrefutable. But he also suggests something even more compelling:

But there is a deeper explanation. A democracy is more than a form of government; it is the extension in space of the number of individuals who participate in an interest so that each has to refer his own action to that of others, and to consider the action of others to give point and direction to his own, is equivalent to the breaking down of those barriers of class, race, and national territory which kept men from perceiving the full import of their activity (Dewey, 1916, p. 83).

In the work of educators like Deborah Meier, education reformer, can be seen a modern implementation of the essence of Dewey’s thought. Meir is the founder of the successful alternative Central Park Elementary School in Harlem based in large part on involving the students in decision-making in a democratic way. To Ms. Meier, there are two basic purposes of schools: to do no harm to children or their families, and to “inspire a generation of Americans to take on our collective task of preserving and nourishing the habits of heart and mind essential for a democracy, and, as we now see, the future of the planet itself.” As far as she is concerned, “The purpose of education is not: (1) to produce a small ‘leadership’ political elite to lead us to the Promised Land or (2) to produce employees to fit into some particular niche determined by others, and surely, (3) it is not to produce higher test scores and give out more diplomas—which is not even a very good way to do the previous two things!” (Meier, 2009).

In asking what must be changed in our schools in order to encourage a “democracy-friendly education,” Meier does not emphasize curriculum, although there may be ways in which it would have to change. Rather, she insists on a fundamental change in the way people relate to each other in schools, and most particularly in the way “their voices are heard and taken into account” (Meier, 2009). For Meier, then, educating for a democratic people means educating democratically, and I would add, morally. Here, if the previous discussion is taken into consideration, might be a place to insert the arts as ground for cultivating that moral education.

Two other notions about 21st century education that support Meier’s perspective can be found in Education Week, where Prakash Nair writes of schools that we should not just rebuild them, but rethink, indeed reinvent them:

In the 21st century, education is about project-based learning, connections with peers around the world, service learning, independent research, design and creativity, and, more than anything else, critical thinking and challenges to old assumptions (Nair, 2009).

And in Larsen:

Those of us concerned about the future of education, and more importantly, the future of this planet, must express our desire for a purpose of education that goes beyond global economic competition. We must envision an education system that affords students the opportunity to grapple with the complex social, ecological, and economic issues we are facing as humans on this planet in comprehensive and creative ways that go far beyond tests (Larsen, 2009).

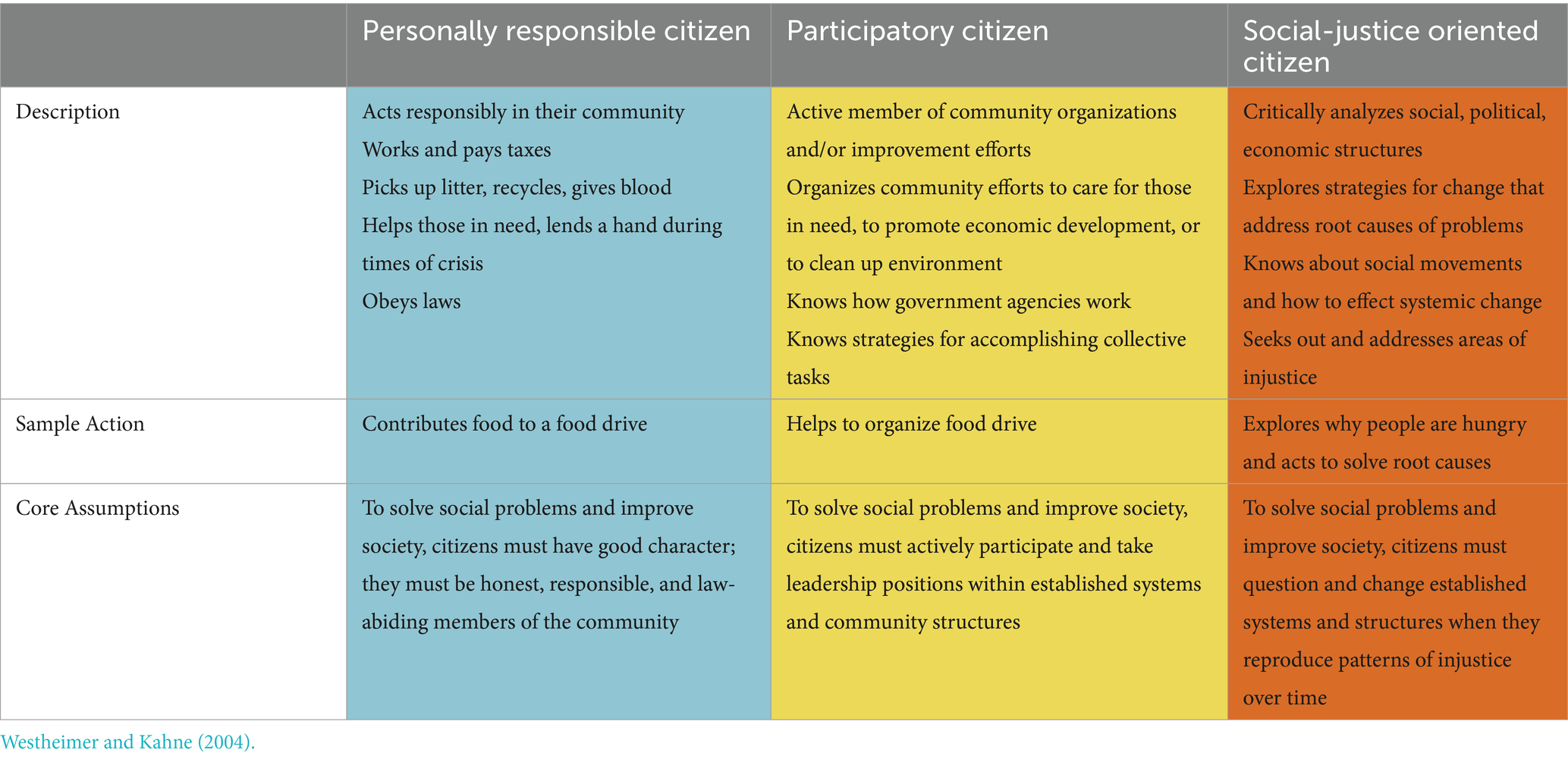

Finally, if we are to educate a citizenry that is not only responsible, and participatory, but actively engaged to ensure social justice, then our schools need to remember the goals first described by Thomas Jefferson in terms of educating for the capacity of discretion, “illuminat[ing] as far as is practicable, the minds of the people at large” (Fraser, 2001, p. 17). Educators need to keep in mind, not primarily what can be tested, but what can awaken their students’ critical thinking and ethical responsibility, so that facts and dates are not of primary importance, but rather more important is their careful interpretation and critically-acquired meaning. Researchers Westheimer and Kahne (2004) emphasize the importance of this latter quality in a study of good citizenship and what that might mean in action. They also look at what it takes to be a good citizens and how these definitions are reflected in democratic educational programs. Westheimer and Kahne isolate three conceptions of the “good” citizen, who must be personally responsible, participatory, and social-justice oriented. They also demonstrate that conservative theories of citizenship that are at the heart of many current efforts at teaching for democracy reflect political choices with political consequences. Below is the authors’ schematic depiction of the three kinds of citizens:

Though it may seem that the above schema implies a normative attitude in which yellow is better than blue and brown is better than yellow, It is possible to imagine that neither color is exclusive; one can have elements of both and there may be very good reasons why one is blue or yellow and not brown. Still, the classifications can potentially be a helpful way of differentiating between various approaches.

The above discussion has made considerable reference to educating for a democratic people, what John Goodlad calls “a non-negotiable agenda” for school reform (Goodlad et al., 2008).

A schematic interpretation of categorical features based on a tripartite view of a democratic society

How does Waldorf education’s developmental curriculum and its trust in individual growth relate to a more comprehensive picture of a democratic society, as mentioned above? The following graphic representation provides a way of looking at the intersection of Waldorf education and its anthroposophical background with educating for democracy and seems to provide a platform for further work on the aesthetic and moral aspects of Waldorf education. A brief explanation of the origins of this particular tripartite view may be helpful in elucidating the usefulness of my original take on it in terms of education.

In 1917, Rudolf Steiner first articulated a transformative approach to governing society at large. He reimagined the three basic domains of daily life—culture, rights, and economics—in a way that radically altered existing structures, from education, to politics, to finance and enterprise. Steiner’s purpose was to return authority and power to individuals through spiritual and cultural practices, and through that to cultivate tools and practices to work collaboratively in political life and the economy that raised the dignity of humanity. This was a direct counterforce to the oppressive nature of government and economics that had arisen before and through World War I, one that prized capital and the power of the state over the creative and imaginative capacities each person brings into the world in service to uplifting the human spirit.

This transformative approach was further articulated by Steiner in his book Towards Social Renewal, in which he develops a conceptual approach to an understanding of social interaction, called the “Threefold Social Organism” (Steiner, 1919). What was so radical about the Threefold Social Organism was its application of the principle of freedom in the cultural domain, equality in the domain of rights, and compassionate interdependence in the sphere of economics. The application of these principles, which had their triadic origin in the ideals of the French Revolution: Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, required a maturity of consciousness not yet present in the early twentieth century (And I might note still not present in the early twenty-first century). The Threefolding Movement that Rudolf Steiner attempted to inculcate as a healing impulse had insufficient grounding to take root at the time. In his disappointment at what he hoped would bring about social transformation and thus avoid what he saw as early as 1918 as the likelihood of another World War, Steiner turned to the field of education to begin the foundational transformation of consciousness. It was this impulse for a healing of humanity and the wholeness of each human being that became one of the fundamental inspirations for the first Waldorf school and articulating a view of human development upon which a new educational curriculum could be landed.

One could look at Steiner’s threefold approach and determine that it is impossible to manage all three simultaneously. But that was what his innovation demanded of an educated citizenry. Steiner put forward a conscious approach to social processes that always left each person to determine what was right for themselves as well as their community. Self-knowledge arising from creative processes would guide each individual to exercise spiritual freedom, to come to rights and agreements out of a feeling for equality and equity, and to approach the economic domain out of a sense for others’ needs.

In recognition that it is the single “I” who must implement the ideals of democracy along with each other one, the individual is placed in the center of the diagram. Then the I, radiating through its education reaches the three primary fields (depicted as the angles)—rights ⇨ equity, spiritual/cultural ⇨ critical thinking, and economic ⇨ social responsibility—each of which in turn have their complements opposite them: relationships, civic engagement, and morality, respectively. The diagram follows:

If one sees democracy as the ground on which this three-fold educational organism evolves, then one can also see that civic engagement, relationship, and morality itself—the three mediators between the points of the realms of rights, economics, and cultural/spiritual—along with the three points, form the ground of ethical life without which democracy cannot thrive. Education is the aesthetic road upon which an individual can travel toward the goal of fully inhabiting the democratic/ethical conceived of in the foregoing formulation.

Practical altruism and the practice of the arts

Steiner’s view of the tripartite commonwealth can be referenced as a framework for understanding his educational system in that Waldorf education cultivates the three key sectors or domains with their respective principles as a basis for a spiritually-informed democratic society. Such an education encourages an understanding of economic life, that area of interdependence, based on altruism. When fully functioning it would operate independently of the political arena except in the essential agreements of safety and fairness. Such altruism could be inculcated within the students from the very way in which they are regarded within the whole of a class, something Patrice Maynard, past leader of the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America, calls “practical altruism” (Maynard, 2009). The Waldorf Schools give an example of this because only extremely rarely is a child “held back” due to academic considerations.

Because attention is given to the health of the group, the students understand that each one is important; each adds value to the whole. They help each other when necessary because all are in the venture of schooling together; there is not the feeling of one being “gifted” and another lesser, because all have a gift in some area, and are able to share that gift. This social understanding is built up organically during the grade school years when a class of students remains together as a group under the guidance primarily of their class teacher. Upon school leaving, there is, then, an attitude of gratitude for each individual; to leave anyone behind is not considered possible, so conflicts must be seen as always resolvable. When the refrain is not “me first” but “after you,” a true practical altruism can arise, along with respect that translates into true democracy (Maynard, 2009).

The cultural life is enlivened when educators work to guide children into the wholeness of their humanity in the face of a scientific rationalism that can tend to hold as a primary focus children’s cognitive learning measured by achieving the highest possible test results without viewing the whole child, within the context of technological advances that threaten to mechanize our lives. The area of critical thinking can be strengthened through envisioning a renewal of thinking that integrates imagination, inspiration, and intuition into our ways of knowing (Sloan, 1992). Moreover, integrating the arts fully into school life and curriculum underscores the vital role of artistic work in guiding students toward thinking holistically as a means of encompassing aesthetic and ethical considerations (Easton, 1997). A school system built on three-fold principles would emphasize that artistic work allows students to become aware of both inner and outer worlds, and to build upon what researchers Ellen Winner and Lois Hetland call “The 8 Studio Habits of Mind:” develop craft/expertise, engage and persist, envision, express, observe, reflect (through question and answer, evaluation of others’ work, and self-evaluation), stretch and explore, and understand the field (Winner and Hetland, 2007, more fully described below).

There is an aspect of the rights sector that is addressed in the Waldorf model insofar as it encourages the empowerment of teachers to set policy and make significant decisions about teaching, curriculum, and administration (Oberman, 1997, pp. 9–10). Teachers’ self-esteem and job satisfaction are enhanced, as is their ability to relate to students and parents in meaningful ways. Although the integration of teaching and administration frequently results in an exhausting overextension for the teachers, there is general agreement that the benefits of teacher participation in decision making about policy and curriculum outweigh the problems (Easton, 1997).

Waldorf education is one of what could take many possible forms of social education that can be developed based upon Steiner’s conception of the threefold commonwealth. The effectiveness of any education derives from the struggle of its leaders’ and teachers to envision and realize schools as cohesive learning communities that share a vision of the aims of education, a common and constantly-renewed image of the students and their development, a curriculum that respects teachers’ professionalism and autonomy, and a common method of teaching for democratic aims. The basic building-blocks of Waldorf education can become a framework for readdressing the questions and broadening the conversation among educators and parents in the wider community about how we educate children to become more fully human, that is, more morally secure, in today’s high-tech world. Waldorf education offers teachers the possibility of an integrated way of viewing themselves as well as their students, their schools, and education itself (Easton, 1997). A world that resounds with social justice requires that its citizens have the flexibility of thinking to respect the capacities and freedom of each individual, to understand that true equality is essential in governing and in the creation of policies and laws, and to see that the sustainability of the economic world will come about only when self-interested behavior is transformed into a more altruistic practice.

The arts and thinking

While these accomplishments point to a moral outcome from the study of arts, it is not necessarily so that such a quid pro quo is in the best interest of arts advocates, nor of the students they represent. According to the researchers, Lois Hetland and Ellen Winner, it is not viable to say that the arts improve academic performance. Though they came to that conclusion after an analysis conducted in 2000, Winner and Hetland later undertook another study to ascertain what the arts actually do teach. The researchers studied five visual arts teachers at two Massachusetts high schools, observing and interviewing them and their students over the course of a year. They found that the arts classes did provide broad benefits to the students, which they characterized in a framework called “Studio Thinking” (Winner et al., 2006). Winner and Hetland found that studio art teachers interact with their students in three primary ways in every class: demonstration-lecture, followed by individual student work, and frequent critique sessions.

Careful study of the student-teacher interactions in the arts classes uncovered eight “studio habits of mind,” which teachers strove to instill. They are:

• Develop Craft. Honing technique and learning to use tools, materials, and artistic conventions. Studio Practice: Learning to care for tools, materials, and space.

• Engage & Persist. Learning to embrace problems of relevance within the art world and/or of personal importance, to develop focus and other mental states conducive to working and persevering at art tasks.

• Envision. Learning to picture mentally what cannot be directly observed and to imagine possible next steps in making a piece.

• Express. Learning to create works that convey an idea, a feeling, or a personal meaning.

• Observe. Learning to attend to visual contexts more closely than ordinary “looking” requires, and thereby to see things that otherwise might not be seen.

• Reflect. Question & Explain: Learning to think and talk with others about an aspect of one’s work or working process. Evaluate: Learning to make aesthetic judgments of one’s own and one’s peers’ work and to defend them.

• Stretch & Explore. Learning to reach beyond one’s capacities, to explore playfully without a preconceived plan, and to embrace the opportunity to learn from mistakes and accidents.

• Understand the Art Community. Learning about art history and current practice as well as learning to interact as an artist with other artists—in classrooms, in local arts organizations, across the art field, and within the broader society.

What is so encouraging about this work is that the arts are seen to have intrinsic worth as subjects worthy of study by all. In fact, Winner and Hetland suggest that academic teachers take a page from the studio teachers’ book and allow their students the freedom of open-ended invention, discovery, and thinking. In short, to bring imagination and artistic sensibility to every aspect of school life, so that their students can benefit from seeing new patterns, learning from their mistakes, and envisioning solutions—just the kinds of abilities they will need to face the unknown challenges of the future. Might there also be a moral element in these lessons from the arts studio?

More lessons that education can learn from the arts

Nobel (1996), writing on the pervasiveness of artistic teaching in the Waldorf schools, states the ideal of art, as a central element not only in Waldorf education, but also in human development, is “not to train people to become artists, but to develop the artistic aptitudes inherent in each and every person. By training our sensitivity to the arts…we can introduce movement and drama and also warmth, aspiration and energy into the process of acquiring knowledge” (Nobel, 1996, p. 266). Nobel’s (1996) Educating Through Art: The Steiner School Approach presents a study that inquires as to why Waldorf teachers’ goal is to integrate artistic elements as part of practical daily realities. Nobel asks, “Why do they [Waldorf educators] attach such significance to art and artistic exercises in the teaching of children and young people, as well as in adult education?” (Nobel, 1996, p. 29). As if in dialogue with her, Elliott Eisner (2004) answers in a passionately eloquent way:

Our destination is to change the social vision of what schools can be. It will not be an easy journey but when the seas seem too treacherous to travel and the stars too distant to touch we should remember Robert Browning’s observation that “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp or what’s a heaven for”.

One could add to this dialogue the work of Maxine Greene, who—with Eisner—was the other well-known proponent of the arts. See her book “Variations on a Blue Guitar” (Lutzker, 2022c).

This is a moral message, one generated by the imagination and expressed through the poetic. And as Dewey said in the closing pages of Art as Experience, “Imagination is the chief instrument of the good.” Dewey adds “Art has been the means of keeping alive the sense of purposes that outrun evidence and of meanings that transcend indurated habit” (Dewey, 1934).

Eisner offers his own framework for what the arts teach about thinking, and, like Winner and Hinton, he suggests that education as a whole must reinvent itself along the lines of artistic thought, with its inherent moral qualities. Only if that is accomplished, says Eisner, can we be liberated from our “indurated habit.” It is fitting to conclude this survey with Dr. Eisner’s vision of a fundamentally different form of education, one dedicated to the preparation of artists (in whatever field) and based on the qualitative forms of intelligence that are developed through the practice of the arts. These forms of thinking have to do with (1) a somatic, intuitive understanding of relationships that calls for judgment in the absence of rules; (2) inviting discovery, surprise, uncertainty, and flexibility of aims so that the end may change in relation to the means of getting there; (3) feeling the equal importance of form and content, which are generally inseparable, meaning whole, so that no element can be substituted and therefore paying attention must be to the particular; (4) expressing meaning in forms beyond those we are familiar with because sometimes the need to formulate what we know destroys the very thing we wish to express; (5) learning to think with and into the material we are working with, enjoying its particular freedoms and constraints and allowing ourselves to engage in a kind of intuitive dialogue with the medium; (6) experiencing aesthetic satisfaction as a motivation for engagement, so that the experience itself can be its own reward (Eisner, 2004).

This artistic frame of mind has the potential to be a fundamentally moral one. It depends upon a deep-seated feeling for the truth, a commitment to justice, and trust in one’s inner capacities. I would add to Eisner’s inspiring list the ethical dimension, encompassing the ideals of imaginative thinking, heart-warmed feeling, and moral action, as number seven, thereby forming a more aesthetically appealing, holistic structure to his already beautiful framework. The beauty of democracy rests with the capacity of each individual to imagine a future and have the social and will capacity to engage others creatively in striving toward that future.

Author contributions

JC: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author declares that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by University of California Irvine by covering publication costs.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, J. S. (2002). Plato: the morality and immorality of art. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 104, 19–24. doi: 10.1080/10632910209605999

Brawley, L. (2009) Why arts education is a matter of social justice and why it will save the world. Part I and II. The Huffington Post. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lucia-brawley (accessed April 24, 2009)

Easton, F. (1995). The Waldorf impulse in education: Schools as communities that educate the whole child by integrating artistic and academic work. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Columbia University, New York.

Easton, F. (1997). Educating the whole child, head, heart and hands: learning from the experience. Theory Pract. 36, 87–94. doi: 10.1080/00405849709543751

Eisner, E. W. (2004) What can education learn from the arts about the practice of education? Int. J. Educ. Arts, 5. Available at: http://ijea.asu.edu/v5n4/ (accessed June 2, 2009).

Goodlad, J., Soder, R., and McDaniel, B. (Eds.) (2008). Education and the making of a democratic people. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Larsen, C. (2009). Obama and education educational policies of president Barack Obama’s administration in a neo-liberal era : Sonoma State University.

Lutzker, P. (2022a). Developing the artistry of the teacher in Steiner/Waldorf education (part I). Scenario 116, 56–67. doi: 10.33178/scenario.16.1.4

Lutzker, P. (2022b). Developing the artistry of the teacher in Steiner/Waldorf education (part II). Scenario 116, 68–88. doi: 10.33178/scenario.16.1.5

Lutzker, P. (2022c). The art of foreign language teaching: Improvisation and drama in teacher development and language learning : Gunter Narr Verlag. Front. Educ. Sec. 9:1363254. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1363254 (Accessed 26 March, 2024).

Meier, D. (2009). Reprinted from green money journal. Available at: http://ijoanjaeckel.blogspot.com/2009/01/d-e-b-o-r-a-h-m-e-i-e-r-democracy.html (accessed June 19, 2009).

Oberman, I. (1997) The mystery of Waldorf: A turn-of-the-century German experiment on today’s American soil. Paper presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, March.

Oberman, I. (2007) Learning from Rudolf Steiner: The relevance of Waldorf education for urban school reform. Self-published paper.

Rethorst, J. (1997) Art and imagination: implications of cognitive science for moral education. Philos. Educ.. Available at: http://www.ed.uiuc.edu/EPS/PES-yearbook/97_docs/rethorst.html (accessed June 10, 2009).

Steiner, R. (1919). Towards social renewal: Rethinking the basis of society. London: Rudolf Steiner Press.

Swanger, D. (1985). Parallels between moral and aesthetic judging, moral and aesthetic education. Educ. Theory 35, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5446.1985.00085.x

Westheimer, J., and Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 41, 237–269. doi: 10.3102/00028312041002237

Winner, E., and Hetland, L. (2007) Art for our sake. The Boston Globe. Globe Newspaper Company, September 2.

Winner, E., Hetland, L., Veenema, S., Sheridan, K., and Palmer, P. (2006). “Studio thinking: how visual arts teaching can promote disciplined habits of mind” in New directions in aesthetics, creativity, and the arts (189–205). eds. P. Locher, C. Martindale, L. Dorfman, and D. Leontiev (Amityville, New York: Baywood Publishing Company).

Keywords: Waldorf, Steiner, imagination, arts, morality

Citation: Caldarera J (2025) Moral education in the context of the arts. Front. Educ. 9:1419335. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1419335

Edited by:

Liane Brouillette, University of California, Irvine, United StatesReviewed by:

Sven Saar, Higher Education Funding Council for Wales, United KingdomPeter Lutzker, Freie Hochschule Stuttgart (Waldorf Teachers College), Germany

Copyright © 2025 Caldarera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joan Caldarera, amNhbGRhcmVyYUBzZndhbGRvcmYub3Jn

Joan Caldarera

Joan Caldarera