Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate both the hypothetical study strategy (preferences) and actual study (practices) of Saudi EFL undergraduate students regarding rereading versus retrieval practice. A total of 202 EFL students were presented with a scenario where they had studied a textbook chapter once and then asked to choose the learning strategy that best reflected their typical approach during different stages of the learning process: the beginning, middle, and end. Then they read a text and responded to both open-ended and forced report questionnaires to explore their actual study behaviors when studying the text. Results showed a consistent preference for restudying throughout all stages of the learning process (36.5, 39.8, 53.6% respectively). Across the learning processes, retesting strategy has been chosen increasingly as the learning process proceeds (16–18.2 - 28.2%) while rereading is decreasing (35.9–23.8 - 13.3%). In the actual study behaviors, the majority of participants reported tendency to rely excessively on restudying and rereading strategies (55.6 and 24.6% respectively) rather than more effective testing strategies (19.8%). Teachers need to educate students that retrieval practice strategies aid in monitoring their learning progress, enhancing learning, strengthening memory recall, and promoting long-term retention.

1 Introduction

Numerous empirical memory research in laboratories and then in classrooms highlights the effectiveness of retrieval practice as a learning strategy compared to mere repetition and demonstrate its advantage for long-term learning (for meta-analytical evidence see, e.g., Adesope et al., 2017; Moreira et al., 2019; Rowland, 2014; Yang et al., 2021). Retrieval practice involves using multiple tests to enhance knowledge retention. The research on the retrieval-practice effect sheds light on the phenomenon that learners often struggle to employ effective study strategies or may make suboptimal choices in their study methods. This discrepancy between what learners believe to be effective study practices and what research indicates as effective has prompted investigation into students’ understanding of effective studying. Studies exploring students’ knowledge about effective studying typically employ two main methods which are (1) examining metacognitive judgments or learners’ study behaviors in laboratory experiments, and (2) surveying learners about their study habits (Rinella and Putnam, 2022). In the first method, researchers observe how learners approach studying tasks and make judgments about their own learning processes. For example, researchers might ask participants to predict how well they will remember information after employing different study strategies, such as re-reading versus self-testing. By comparing participants’ predictions with their actual performance, researchers can assess the accuracy of learners’ metacognitive judgments and the effectiveness of their study behaviors. In the second method, researchers also gather data on students’ study habits and beliefs through surveys and questionnaires. These surveys may inquire about the study techniques students commonly use, their perceived effectiveness of different strategies, and their understanding of principles such as the testing effect. By analyzing survey responses, researchers gain insights into students’ awareness of effective study practices and any misconceptions they may hold.

Existing academic literature has extensively studied how students engage with retrieval practice strategies. However, there remains a noticeable gap regarding comprehensive investigations into students’ preferences for and actual usage of testing and rereading as effective learning tools. Moreover, to the best of my knowledge, no prior research has specifically explored this issue within the context of Saudi English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students. To address this gap in the literature, the primary objective of this study is to thoroughly examine both the stated preferences and real-world behaviors of Saudi undergraduate EFL students concerning their choice and implementation of testing and rereading strategies in their learning processes. This research aims to provide valuable insights that contribute to a deeper understanding of how Saudi EFL students approach and engage with these learning techniques, thereby offering practical implications for enhancing their academic performance and learning outcomes.

2 Literature review

The study conducted by Karpicke et al. (2009) investigated undergraduate students’ study habits and preferences through a survey with two main parts. In the first part, students freely reported and ranked their study strategies based on frequency of use. The second part involved a forced-choice questionnaire where students selected between repeated reading, self-testing (retrieval practice), or another study activity for exam preparation. Findings revealed that 84% of students utilized repeated reading as a study strategy, with 55% favoring it. In contrast, only 11% practiced retrieval (self-testing), and merely 1% favored this method. When given the option between repeated reading and self-testing, 57% chose repeated reading, while only 18% preferred self-testing. The series of experiments conducted by Karpicke (2009) and subsequent studies provide robust evidence that students often fail to engage in retrieval practice as early or as frequently as needed for optimal learning outcomes. This failure to practice retrieval was evident in subsequent studies, indicating a consistent pattern across different experimental settings. Studies by McCabe (2011), Blasiman et al. (2017), Anthenien et al. (2018) and others investigated students’ preferences for study strategies through open-ended free report or forced report questions. Results consistently showed that students reported a meta-cognitive preference for rereading over testing in hypothetical learning scenarios. Students tended to give higher efficacy ratings to rereading notes compared to practice testing for exam preparation. The findings align with a meta-analysis conducted by Miyatsu et al. (2018), which revealed that rereading is the most frequently used study strategy among students, with 78% of students employing this method.

In a review of 16 studies investigating learners’ beliefs regarding test-enhanced learning conducted by Rivers (2020), it was discovered that, on average, 62% of participants reported utilizing rereading or reviewing materials, while 57% reported using self-testing. Additionally, approximately 43% considered rereading their primary and most frequently employed strategy, whereas only about 8% of participants reported self-testing as their primary and most frequently used strategy.

When analyzing studies that demonstrated high reports of testing usage (e.g., Geller et al., 2017; Hartwig and Dunlosky, 2012; Rinella and Putnam, 2022), it became apparent that participants were typically presented with a list of strategies to choose from. In contrast, studies that utilized free report questions about strategy use often yielded different results. This discrepancy suggests that the method of inquiry—whether participants are prompted to select from a predetermined list or provide their responses freely—can influence the reported prevalence of testing as a study strategy. Another possible reason for this is that while college students may engage in self-testing or practice tests, they may primarily view these activities as diagnostic tools to assess their current level of understanding rather than as active learning strategies aimed at enhancing their knowledge (Weissgerber and Rummer, 2023). Another possible reason is that learners might group testing under a broader category like “restudying,” leading to potential confusion or misinterpretation of study behaviors (Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger, 2019).

Research by Karpicke and Blunt (2011) and Roediger and Karpicke (2006) shows that students often misjudge the effectiveness of study strategies, particularly favoring rereading over testing for long-term learning. Despite contrary evidence, they tend to overestimate the value of rereading and underestimate retrieval practice. The preference for rereading may stem from its lower effort and familiarity, even though students rate flashcards as effective but still view highlighting as more beneficial (Blasiman et al., 2017). This gap in perceived versus actual effectiveness highlights a disconnect in understanding effective study methods.

The way students approach self-testing also influences its success. If they view practice tests merely as assessments of their knowledge, they may not engage deeply with the material or use feedback to enhance learning, focusing instead on scoring. Additionally, students often struggle to see the advantages of practice tests compared to re-reading, as the benefits of retrieval practice become clearer over time, particularly after a delay (Tullis and Maddox, 2020). While practice tests actively strengthen memory retention, their benefits may not be immediately apparent, making re-reading seems more comfortable and familiar in the short term.

Very few studies investigated both the students’ preferences and actual use of testing and rereading as learning tools at the undergraduate level. Blasiman et al.'s (2017) study provides valuable insights into both students’ intended and actual study behaviors, as well as their beliefs about the effectiveness of different strategies over the course of a semester. The study surveyed 268 undergraduate participants, assessing their intended study strategies and beliefs about effectiveness on a 1–10 Likert scale. Participants were surveyed at the beginning of the semester and six times throughout the semester to track changes in study behaviors and beliefs over time. Participants ranked rereading notes and rereading the textbook as the most reported study strategies. In contrast, taking practice tests and using flashcards were among the least used strategies and were perceived as less effective by participants. The study revealed a discrepancy between participants’ intended study strategies and their actual utilization. Despite ranking rereading highly in terms of intention, other strategies such as practice tests and flashcards were less frequently used in practice. Participants’ beliefs about the effectiveness of different strategies may have influenced their study choices. Despite evidence supporting the effectiveness of practice tests and flashcards, participants perceived these strategies as less effective compared to rereading. Blasiman et al.'s (2017) study highlights the gap between students’ beliefs about effective study strategies and the actual utilization of those strategies. Despite acknowledging the effectiveness of certain active learning techniques like practice tests and flashcards, students may still gravitate toward more passive methods like rereading.

The study conducted by Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger (2019) provides additional insights into the study behavior of undergraduate students, particularly regarding the preference for rereading versus testing at different stages of the learning process. 76 undergraduate students were surveyed to identify the hypothetical and real study behavior when restudying the text. Results of open ended free report revealed that rereading was preferred in the early learning process, while testing became more preferred during the late learning process. This suggests a shift in study strategies over time, with students initially relying on rereading and later transitioning to testing as they progress in their learning. The forced report questionnaire showed that a significant majority (89.7%) of participants reported using rereading for not understood parts of the text. Additionally, 34.5% of participants reported rereading the entire text, while only 13.8% reported testing themselves. These findings are consistent with the patterns observed in Karpicke et al.'s (2009) study, indicating a common preference for rereading over testing, particularly in the early stages of learning.

Research on retrieval practice in the context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) has primarily focused on several key areas. Studies have mainly examined how retrieval practice affects the retention of language skills and overall learning outcomes (Estagi and Khosravi, 2015; Makarchuk, 2018; Terai et al., 2021; Tajalli et al., 2022; Çalik-Uzun and Çelik-Demirci, 2023; Chiu and Hawkins, 2023; Aljabri, 2024a). Others have significantly investigated students’ perceptions of retrieval practice (Chandra, 2024) and the effects of collaborative retrieval practice (Aljabri, 2024b). Furthermore, to my knowledge, there are no prior studies that have investigated Saudi EFL students’ preferences and actual use of retrieval practice and rereading strategies as learning tools at the undergraduate level. To address this gap and contribute to the existing literature on study strategies favored by EFL students, the primary objective of the initial study is to explore the hypothetical study preferences of Saudi undergraduate EFL students. By asking participants to envision their study methods in a given scenario, the researcher aims to uncover students’ initial preferences and choices regarding different learning strategies. This research seeks to deepen the understanding of how EFL students perceive and prioritize various study approaches, providing valuable insights for educators and researchers working to refine educational practices in EFL contexts. Additionally, the study examines the actual study behaviors of EFL students as they engage with textual material. This study aims to answer the following research questions:

What study strategy preferences do Saudi EFL students have (Repeated reading versus testing) throughout all stages of the learning process?

What are the actual study practices of Saudi EFL students when studying a text?

Were the preferences and practices of Saudi EFL students the same when studying a text?

3 Method

3.1 Participants

Two hundred and two undergraduate students enrolled in the Department of English at UmmAl-Qura University in Saudi Arabia participated in this study. They were chosen randomly and took part in the survey in exchange for course credit. The participants consisted of 63 male students, accounting for 31.5% of the sample, and 139 female students, making up 68.5% of the sample. The average age of the participants was 21.3 years, with a standard deviation of 1.7 years (Mage = 21.3, SD = 1.7). They were studying two courses from Year 3 and 4. This choice is intentional because students in their first and second years take courses in reading comprehension, which equips them with diverse learning strategies for handling EFL texts. All have studied English for 8 years before joining the English Department.

3.2 Material

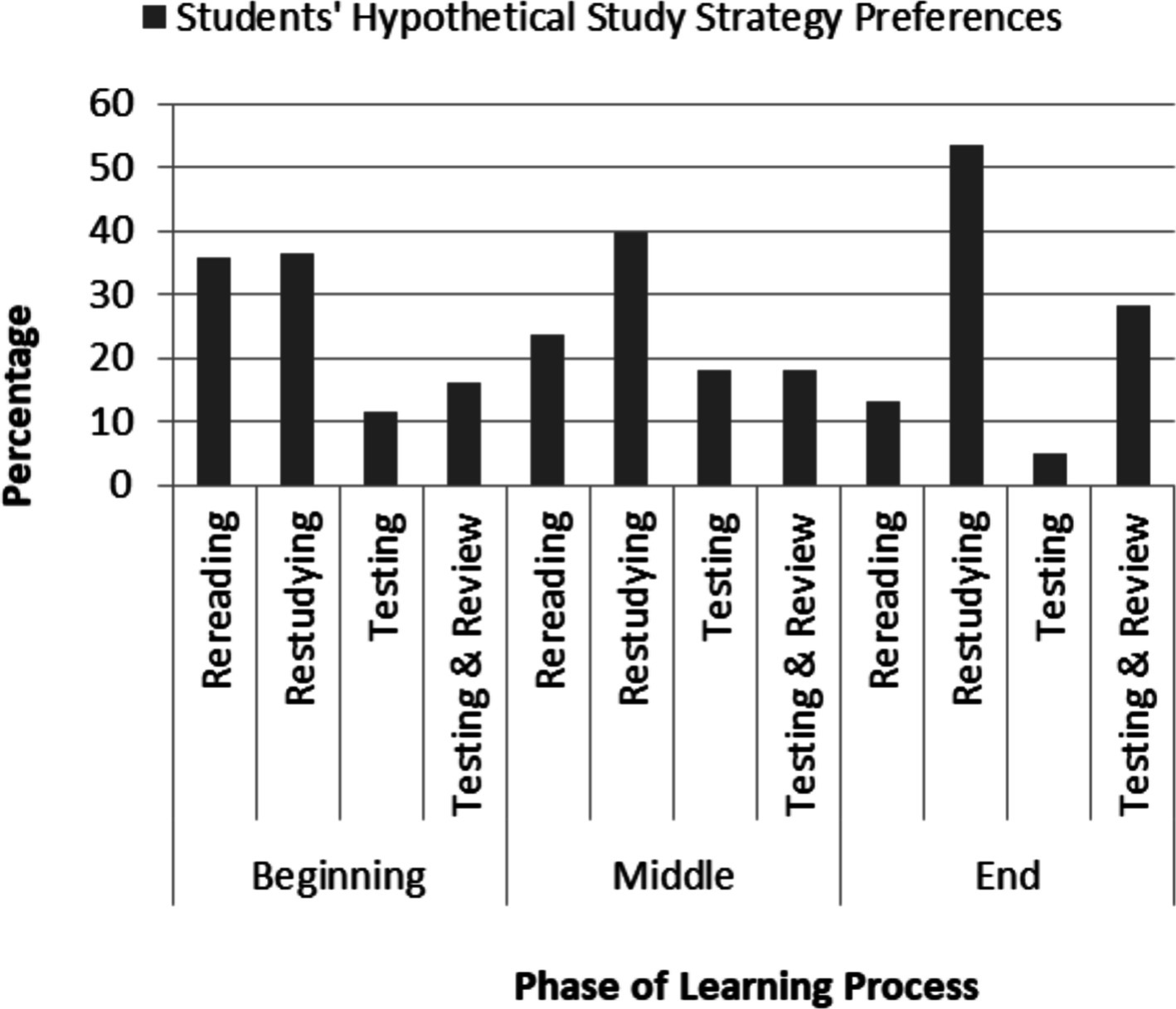

For the hypothetical study preferences, three questions were formulated based on Question 2 of Karpicke et al. (2009) and Study 1 of Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger's (2019) research. These questions prompt students to imagine having studied a textbook chapter once and then select the learning strategy that most closely resembles their usual approach from four options: repeated rereading, restudying, self-testing without reviewing the text afterward, or self-testing followed by text review. Each question is designed to reflect a different stage of the learning process: the beginning, middle, and end. An online survey was created, consisting of these three questions tailored to each stage of learning. Participants received a link to access the survey and were instructed to respond to all three questions sequentially.

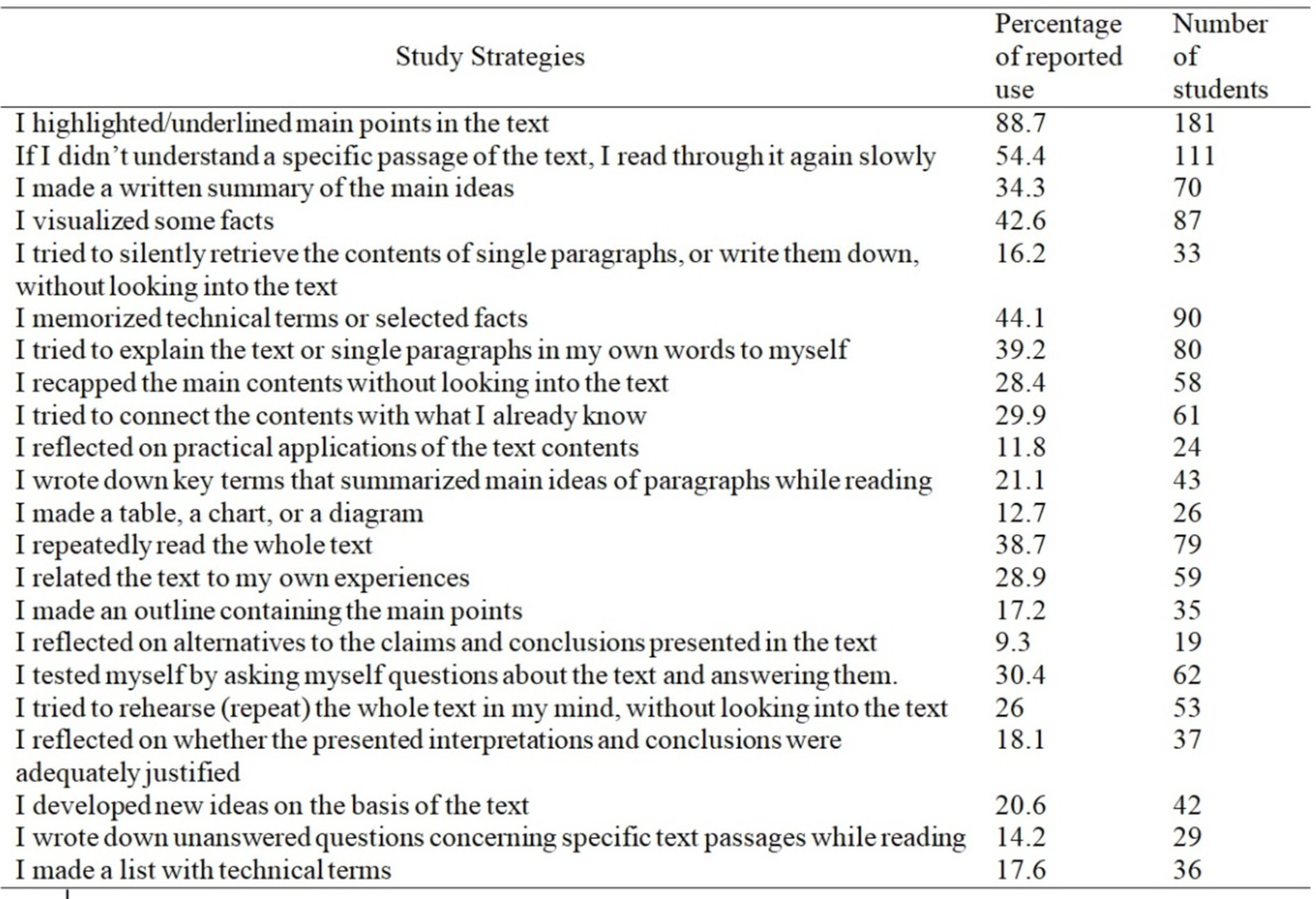

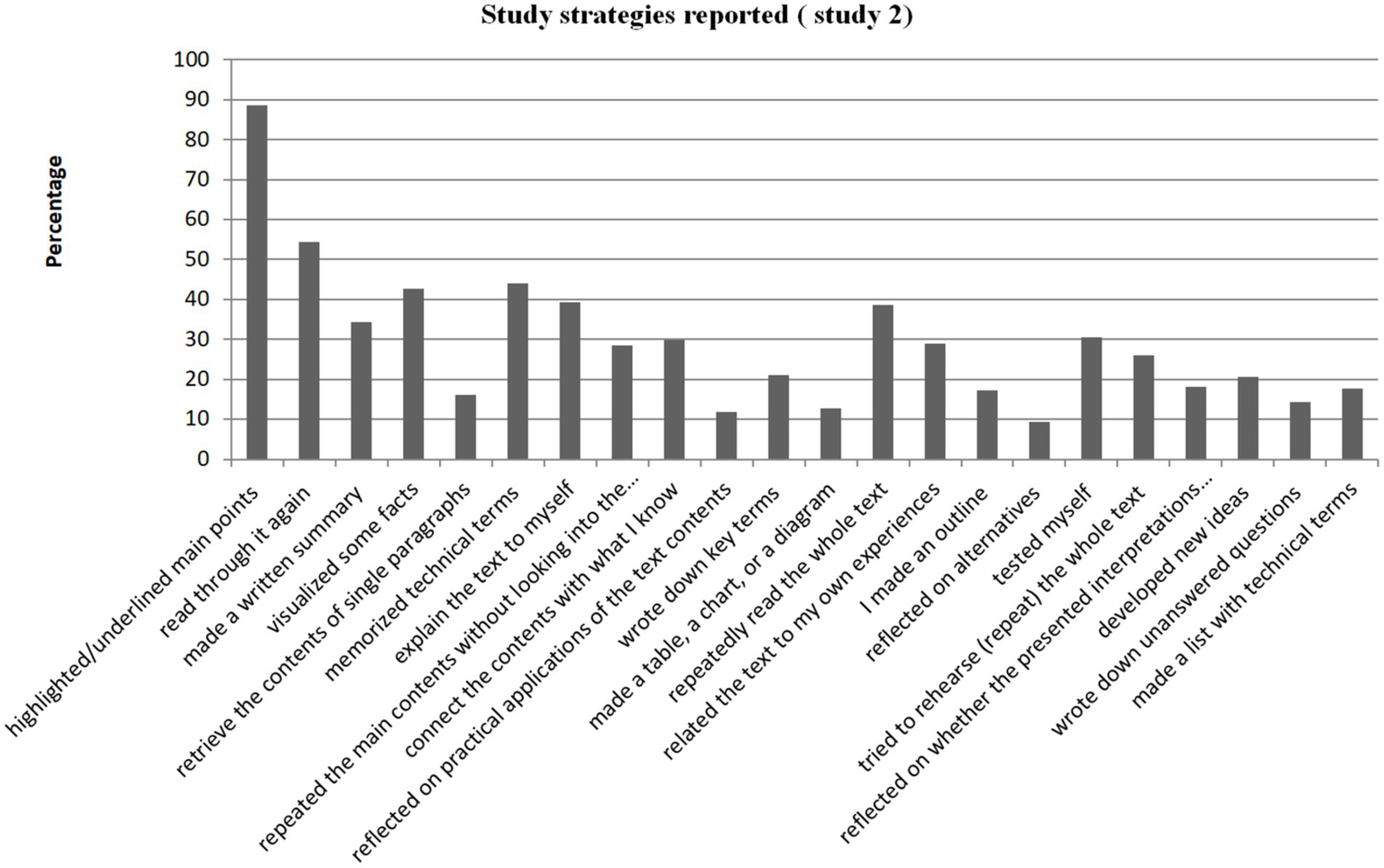

For the actual study behaviors, a 451-word text on “The Teenage Brain” was carefully selected from “Reading Explorer 2” by Macintyre and Bohlke (2020). It was selected by two experienced English teachers to ensure its relevance and appropriateness to students. This text served as the learning material for the study. To evaluate students’ study behaviors when restudying the text, two instruments were developed: an open-ended free report question and a forced report questionnaire. The open-ended question prompted students to describe their study behaviors during restudying, encouraging responses in Arabic or English. The forced report questionnaire, adapted from study strategy checklists used by Hartwig and Dunlosky (2012) and Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger (2019), comprised 22 study strategies (see Figure 1). The rationale for employing both instruments stems from previous research indicating that the effectiveness of retrieval practice varies across studies (Rivers, 2020). For instance, studies where students select from a list of strategies (e.g., Hartwig and Dunlosky, 2012; McAndrew et al., 2016) demonstrated an increased use of retrieval practice. In contrast, studies requiring students to freely report their strategies showed a decrease (e.g., Karpicke et al., 2009). This discrepancy was highlighted in the study by Tullis and Maddox (2020). Therefore, utilizing both an open-ended free report question and a forced-choice questionnaire is essential.

Figure 1

Study strategies reported in the forced report questionnaire.

Similar to Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger’s (2019) study, the survey employed a detailed forced-report questionnaire, offering participants distinct response options such as “repeated rereading” and “rereading not understood contents,” along with a wide array of other study strategies. To address potential inconsistencies noted in prior research (Karpicke et al., 2009) between open-ended free report questions and forced-report questions, participants were first asked to respond to an open-ended free report question regarding their utilized study strategies before completing the forced-report questionnaire. If the findings replicate the pattern observed in Karpicke et al. (2009), where few participants reported using testing in response to open-ended questions despite it being selected quite frequently in forced-choice questionnaires, it would raise questions about the validity of open question formats. Such a discrepancy would suggest that students’ subjective interpretations of their study behaviors may not accurately reflect their actual study practices. This underscores the importance of employing rigorous methodologies to capture the nuances of student learning behaviors effectively. In contrast to prior studies, which primarily focused on asking students to either report their use of or compare a predetermined set of strategies (Blasiman et al., 2017; Hartwig and Dunlosky, 2012; McCabe, 2011; Morehead et al., 2015), the use of an open-ended free report question allows participants the opportunity to share any strategy they utilize when studying a text.

3.3 Procedure

Before the experiment began, participants received a brief overview that covered general learning processes and the various preferences learners might have for different methods. They were also given explanations of restudying and retesting. Participants were instructed to answer the survey questions truthfully. Data collection took place during class time, with participants directed to access the survey via a link provided by the instructor. The survey began with an introductory message explaining the study’s purpose and providing completion instructions. Participants first entered basic demographic information, including their names, ID numbers, gender, and age. Each section of the survey was introduced in sequence, with participants required to finish one section before moving on to the next, ensuring a systematic approach to answering all relevant questions.

The second part of the survey was about the hypothetical study strategy preferences. Participants were required to imagine they had studied a textbook chapter once. They then had to choose the learning strategy that best reflected their typical approach. The online questionnaire was organized into three sections, each corresponding to a different stage of the learning process: beginning, middle, and end.

The third part of the study was structured into three distinct phases: the study phase, the restudy phase, and the restudy behavior assessment phase. Participants were informed that they were part of a study investigating study strategies and would be studying a text on “The Teenage Brain” for a delayed test in 1 week. They were provided with a booklet containing the text, distractor tasks, and the text again. During the initial study phase, participants were instructed to read the text carefully and attempt to memorize its contents through reading only for a duration of 5 min, without using any other study strategies. Following a one-minute break, during which participants completed simple math distractor tasks, the restudy phase commenced. Here, participants were instructed to restudy the text in the same way in which they usually study text contents when trying to memorize them for a later test, for a duration of 12 min. In the subsequent restudy behavior assessment phase, participants were directed to an online questionnaire where they were asked to respond to an open-ended free report question regarding their study behaviors during the restudy phase. They were able to write their responses in either Arabic or English. After completing this question, participants proceeded to the forced report questionnaire which included 22 study strategies and participants were instructed to choose all the strategies they used when studying the text.

4 Results

4.1 Participants’ hypothetical study strategy preferences

Figure 2 shows the participants’ hypothetical study strategy preferences. It indicates that restudying and rereading were the most frequently chosen strategies by participants at the beginning of the learning process (36.5 and 35.9% respectively). Testing with review of the material came third with 16% of participants while testing without reviewing was the last chosen strategy with 11.6%. In the middle of the learning process, percentages of chosen strategies were almost similar to those at the beginning of the learning process. Restudying was also the most frequently chosen one with 39.8% of participants. It was followed by rereading with 23.8% of participants. Testing with and without reviewing were the last chosen strategies with 18.2%. At the end of the learning process, a dramatic change is noticed. Restudying was the most frequently chosen strategy with 53.6% of participants. It was followed by testing with reviewing the material (28.1%). Rereading came third with 13.3%. The last chosen strategy was testing without reviewing the material with only 5%. Across the learning processes, retesting and restudying strategies have been chosen increasingly as the learning process proceeds while rereading is decreasing. The least chosen strategy at the end of the learning process is testing without reviewing.

Figure 2

Participants’ hypothetical study strategy preferences.

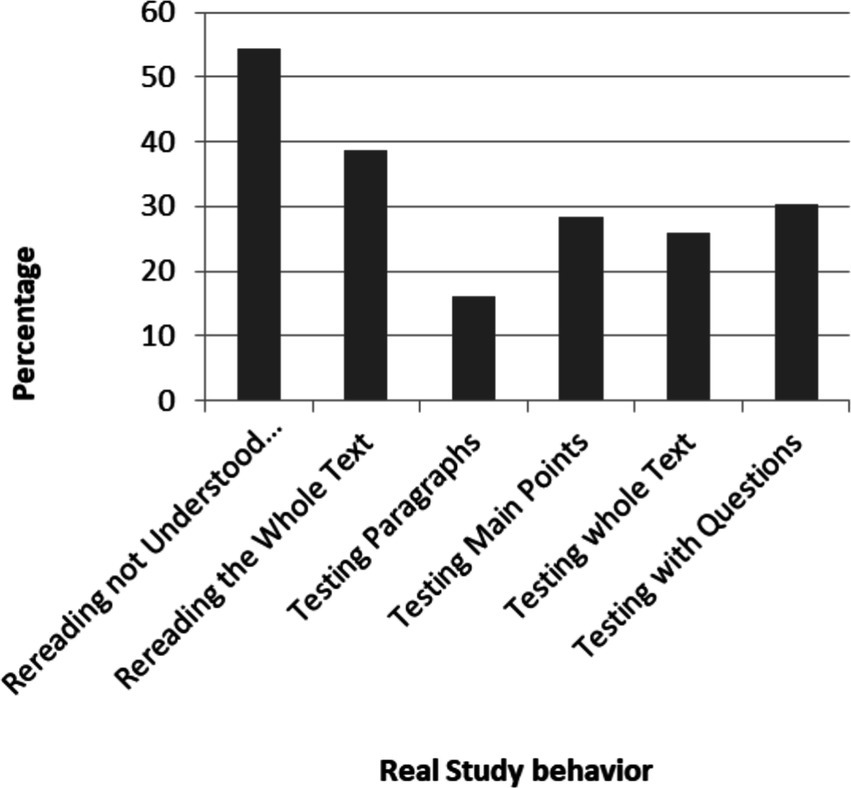

4.2 Open-ended free report question

Following a thorough examination of participants’ responses, six primary study strategies were identified by two English teachers. Within the “rereading” strategy, three subcategories were delineated, while the “self-testing” strategy was subdivided into two categories. Table 1 presents the main study strategies, their subcategories, the number of participants who used each strategy, and the percentage of participants for each category. Similar to the results of Karpicke et al. (2009) and Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger (2019), a very low number of students used self-testing when restudying the text. 10.8% of the participants reported that they use self-testing alone or with a friend as a study strategy. 6.1% of the participants reported rereading the text once, 12.8% reported that they reread the text more than once, and 5.7% reported that they reread the highlighted parts. Thus, 24.6% of the participants reported using rereading as a study strategy. Highlighting the main points was the most common reported strategy with 38.3%.

Table 1

| Study Strategies | Percentage of reported use | Number of students |

|---|---|---|

| Highlighting / Underlying main points | 38.3 | 120 |

| Writing down main points / summary / notes | 17.3 | 54 |

| Rereading the text once | 6.1 | 19 |

| Rereading the text more than once | 12.8 | 40 |

| Rereading main points / highlighted parts | 5.7 | 18 |

| Self-testing alone | 8.6 | 27 |

| Self-testing with friends | 2.2 | 7 |

| Memorizing | 5.4 | 17 |

| Forming elaborative associations | 3.6 | 11 |

Study strategies reported in the open-ended questionnaire.

4.3 Forced report questionnaire

Results represented in Figures 1, 4 showed that 54.4% of the participants reported that they reread the text when they did not understand the passage. They also showed that 38.7% of participants reported that they reread the whole text and this is consistent with the results of the open ended free report question. When it comes to the four response options representing forms of self-testing, results showed that participants used them less than using rereading strategies. More precisely, 16.2% of the participants reported testing themselves by retrieving the contents of single paragraphs, 28.4% reported retrieving the main contents without looking into the text, 30.4% tested themselves by retrieving the whole text, and 26% reported testing themselves by asking questions. This result shows a compatible pattern between the result of Open-ended free report question and that of forced report questionnaire. The majority of participants reported using rereading strategies in the hypothetical situation and confirmed that in the real situation. Self-testing strategies were lower than rereading strategies in both situations. This conclusion contradicts the results of Karpicke et al. (2009) and Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger (2019) who found divergent pattern depending on the type of the questionnaire used. In Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger (2019), more participants reported using testing paragraphs and main points than those repeatedly reread the whole text (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Study strategies reported in the forced report questionnaire.

5 Discussion

The first research question aimed to explore which study strategies Saudi EFL undergraduate students prefer to use. Results of the students’ hypothetical study strategy behavior are consistent with results of Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger (2019) only at the beginning of the learning process. Both rereading and restudying strategies were chosen first as the preferential strategies while self-testing was the third. Furthermore, as the learning process proceeds, the percentage of participants who preferred to restudy or test themselves increased while the percentage of participants who preferred to reread decreased (76% preferred to retest and restudy while 23% preferred to reread). These results align with recent studies indicating that students in educational settings often exhibit limited use of testing strategies while increasing their reliance on restudying strategies (e.g., Blasiman et al., 2017; Hartwig and Dunlosky, 2012; Karpicke et al., 2009; Kornell and Bjork, 2007; McCabe, 2011; Morehead et al., 2015; Wissman et al., 2012). The findings underscore that EFL learners typically resort to rereading earlier in the learning process, whereas they tend to adopt testing strategies later on (Janes et al., 2018).

The first part of the study highlighted the evolving preferences of students regarding study strategies over the course of learning. Early on, restudying is favored over rereading, with a notable shift toward testing as learning progresses. However, the specific behaviors associated with terms like “rereading” and “restudying” remain ambiguous. It is important to note that in memory research, the terms ‘rereading’ and ‘restudying’ are used interchangeably to refer to the process of revisiting learning materials. For instance, it is unclear whether “rereading” implies repeated reading or revisiting incomprehensible material. Similarly, “restudying” might encompass various strategies, potentially including testing (Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger, 2019). This suggests that testing could be more prevalent in students’ actual restudy practices than indicated by the first part of the study. Additionally, since students were surveyed about hypothetical rather than actual behaviors, there might be discrepancies between reported and real study habits. Clarifying these nuances could provide deeper insights into effective learning strategies (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Actual study behavior when restudying the text.

The second and third research questions of this study aimed to investigate the actual study practices of Saudi EFL students when studying a text and whether they are similar to learners’ preferences. The results of the second part of the study reflect those of the first part, demonstrating a significant alignment between participants’ hypothetical study behaviors and their actual study practices, especially in relation to restudying. Throughout all stages of the learning process, participants consistently favored restudying as their preferred learning strategy. This preference translated into their actual study behavior, as they predominantly utilized restudying more than other strategies. However, there was a divergence between the results of the two parts of the study regarding participants’ preferences and actual behaviors concerning rereading and testing strategies. While participants expressed a preference for testing strategies as the learning process progressed in the hypothetical scenarios, their actual study behavior leaned more toward rereading strategies than testing strategies. These differences suggest that there may be a discrepancy between participants’ stated preferences and their actual study practices, particularly in the case of testing strategies. It’s possible that while participants might recognize the benefits of testing strategies in theory, they may default to familiar and perhaps less effective strategies like rereading when it comes to actual study situations.

A more nuanced examination of rereading behaviors revealed that participants primarily engaged in rereading with the specific intent of revisiting sections of text they found incomprehensible, rather than simply engaging in repeated reading of the entire text. Notably, these distinctions were only discernible through a forced-report questionnaire that specifically included these study behaviors, highlighting a discrepancy between forced-report and open-ended free report questionnaires (Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger, 2019). Participants reported using rereading more frequently for sections they did not understand or for the entire text, compared to using self-testing for main ideas. When considering these results alongside prior research (e.g., Hartwig and Dunlosky, 2012; Kuhbandner and Emmerdinger, 2019; Susser and McCabe, 2013), a consistent pattern emerges regarding the strategies participants most and least commonly employ. Specifically, participants in this study tended to overuse rereading strategies while underutilizing self-testing strategies.

Findings from both laboratory research and survey investigations consistently highlight a common behavior among students: a tendency to overlook the advantages of self-testing strategies in favor of less effective study approaches. Studies conducted in controlled laboratory settings have repeatedly shown that students frequently underestimate the effectiveness of self-testing strategies when compared to passive review methods like rereading/restudying (Tullis and Maddox, 2020). Despite robust evidence supporting the efficacy of self-testing, students often express a perception of having learned less when employing these active retrieval techniques. Given the option between self-testing and simpler yet less effective strategies such as rereading / restudying, students typically lean toward the latter (Logan et al., 2012; McCabe, 2011). Survey investigations among students echo the findings from laboratory experiments, revealing that many students engage in ineffective study practices. They may neglect to utilize potent study strategies such as self-testing, despite the potential for these methods to enhance learning outcomes (Rivers, 2020). Instead, students may rely on less efficient techniques like re-reading or highlighting, which may foster a misleading sense of mastery but fail to foster long-term retention and comprehension (Blasiman et al., 2017; Hartwig and Dunlosky, 2012; Karpicke et al., 2009; Susser and McCabe, 2013; Wissman et al., 2012).

The findings of this study support previous surveys, which indicate that rereading remains one of the most commonly used study strategies. One tentative explanation for learners’ preferences for the reading strategies is proposed by Blasiman et al. (2017). They suggested that repeated reading gives students a deceptive feeling of learning, often termed as an illusion of competence (Bjork, 1999; Koriat and Bjork, 2005). When students engage in rereading their notes or textbooks, they might perceive a mastery of concepts due to a sense of familiarity, yet this familiarity can be misleading. Koriat and Bjork (2005) believe that information available to learners when studying a text affects their judgments of learning and, therefore, illusion of familiarity arise. The failure to accurately monitor one’s learning progress is a crucial aspect contributing to the illusion of competence. Metacognition, which involves awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes, is essential for effective learning. When students engage in reading strategies like highlighting main points without actively assessing their comprehension, they may indeed fall into the trap of thinking they understand the material better than they actually do (Kenney and Bailey, 2021). When students use reading techniques like highlighting key points, they often do not take the time to reflect on whether they truly understand the material. If they recognize a term, they may move on without checking their memory. This sense of familiarity can lead them to miss retrieving information accurately, thus failing to metacognitively monitor their learning.

The present findings indicate that Saudi EFL learners consider testing an ineffective study strategy throughout all learning phases. Although they increasingly utilize testing at the end of the learning process, it remains significantly less favored than rereading and restudy strategies. A crucial practical implication is that teachers should educate EFL learners about the importance of retrieval practice and its benefits for strengthening memory recall and promoting long-term retention. This does not imply disregarding the restudy strategies that learners are accustomed to using, but rather, it highlights the need to incorporate retesting strategies as well. Enhancing learners’ awareness of the significance of retrieval practice is essential. However, caution is warranted, as the texts used in this laboratory study were brief, and the intervals between reading and restudying tasks were short. This may differ from real-life learning situations.

6 Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the study habits and preferences of Saudi EFL students, both in hypothetical scenarios and actual learning environments. Furthermore, it endeavors to uncover the particular learning methods employed by EFL students, providing essential insights for educators and language learners alike. The students’ tendency to rely excessively on rereading and restudying strategies instead of more effective testing strategies should prompt teachers to emphasize the importance and efficacy of testing in the learning process. Students should be informed and made aware that retrieval practices not only aid in monitoring their learning progress but also serve as powerful tools for enhancing learning, strengthening memory recall, and promoting long-term retention. By shifting the focus toward testing, teachers can encourage students to engage in active recall and retrieval of information, rather than simply reviewing material passively.

The present study constitutes a preliminary investigation into the hypothetical and actual study strategies employed by EFL students, specifically focusing on retrieval practice and rereading techniques. It provides foundational insights that can inform future research in this domain. To further elucidate EFL students’ preferences and practices regarding retrieval practice, subsequent studies should explore its application in both controlled laboratory settings and authentic educational contexts, evaluating its effects on learning outcomes and academic performance.

Like any research, this study has some limitations that do not undermine its findings. This study focused on only third and fourth-year undergraduate students. Broader research that includes participants from various educational stages is required. The study’s cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single time point, restricts the ability to observe temporal changes in study strategies. Longitudinal research is recommended to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the evolution of students’ retrieval practices. Although data were collected through an online survey, future studies should incorporate qualitative methodologies, such as interviews, to provide a more detailed perspective on students’ attitudes and experiences with retrieval practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: the research data for this study will be accessible from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Sameer Aljabri, ssjabri@uqu.edu.sa.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee - Umm Al-Qura University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this paper, the author utilized Open AI’s Natural Language Processing system’s AI Editing System CHATGPT. This system was used to correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors, as well as to improve the clarity, coherence, and style of the research paper. After using this service, the author carefully reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the final version.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AdesopeO. O.TrevisanD. A.SundararajanN. (2017). Rethinking the use of tests: a meta-analysis of practice testing. Rev. Educ. Res.87, 659–701. doi: 10.3102/0034654316689306

2

AljabriS. (2024a). Investigating the effect of retrieval practice on EFL students' retention of prose passages: repeated testing versus studying. World J. English Lang.14, 303–312. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v14n5p303

3

AljabriS. (2024b). Engagement and preferences: EFL students' use of collaborative retrieval practice. Cogent Educ.11:2394741. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2394741

4

AnthenienA. M.DeLozierS. J.NeighborsC.RhodesM. G. (2018). College student normative misperceptions of peer study habit use. Soc. Psychol. Educ.21, 303–322. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9412-z

5

BjorkR. A. (1999). “Assessing our own competence: heuristics and illusions” in Attention and performance XVII. Cognitive regulation of performance: Interaction of theory and application. eds. GopherD.KoriatA. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 435–459.

6

BlasimanR. N.DunloskyJ.RawsonK. A. (2017). The what, how much, and when of study strategies: comparing intended versus actual study behavior. Memory25, 784–792. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2016.1221974

7

Çalik-UzunS.Çelik-DemirciS. (2023). Collaborative testing as an alternative assessment technique in algebra. Int. e-Journal Educ. Stud.7, 287–309. doi: 10.31458/iejes.1240193

8

ChandraY. (2024). The effect of group-individual collaborative testing on primary students’ achievement in reading test. JEELS11, 157–184. doi: 10.30762/jeels.v11i1.2630

9

ChiuC.-H.HawkinsC. F. (2023). The effectiveness of combining the keyword mnemonic with retrieval practice on L2 vocabulary learning in Taiwanese EFL classes. J. English Foreign Lang.13, 452–474. doi: 10.23971/jefl.v13i2.6313

10

EstagiM.KhosraviF. (2015). Investigating the impact of collaborative and static assessment on the Iranian EFL students’ reading comprehension, critical thinking, and metacognitive strategies of reading. Iran. J. Appl. Lang. Stud.7, 17–44. doi: 10.22111/IJALS.2015.2384

11

GellerJ.ToftnessA.ArmstrongP.CarpenterS.ManzC.CoffmanC.et al. (2017). Study strategies and beliefs about learning as a function of academic achievement and achievement goals. Memory26, 683–690. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2017.1397175

12

HartwigM. K.DunloskyJ. (2012). Study strategies of college students: are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement?Psychon. Bull. Rev.19, 126–134. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0181-y

13

JanesJ. L.DunloskyJ.RawsonK. A. (2018). How do students use self-testing across multiple study sessions when preparing for a high-stakes exam?J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn.7, 230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.11.003

14

KarpickeJ. D. (2009). Metacognitive control and strategy selection: deciding to practice retrieval during learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen.138, 469–486. doi: 10.1037/a0017341

15

KarpickeJ. D.BluntJ. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science331, 772–775. doi: 10.1126/science.1199327

16

KarpickeJ. D.ButlerA. C.RoedigerH. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: do students practice retrieval when they study on their own?Memory17, 471–479. doi: 10.1080/09658210802647009

17

KenneyK. L.BaileyH. (2021). Low-stakes quizzes improve learning and reduce overconfidence in college students. J. Scholar. Teach. Learn.21, 79–92. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v21i2.28650

18

KoriatA.BjorkR. A. (2005). Illusions of competence in monitoring one’s knowledge during study. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn.31, 187–194. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.5.1133

19

KornellN.BjorkR. A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychon. Bull. Rev.14, 219–224. doi: 10.3758/BF03194055

20

KuhbandnerC.EmmerdingerK. (2019). Do students really prefer repeated rereading over testing when studying textbooks? A reexamination. Memory27, 952–961. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2019.1610177

21

LoganJ. M.CastelA. D.HaberS.ViehmanE. J. (2012). Metacognition and the spacing effect: the role of repetition, feedback, and instruction on judgments of learning for massed and spaced rehearsal. Metacogn. Learn.7, 175–195. doi: 10.1007/s11409-012-9090-3

22

MacintyreP.BohlkeD. (2020). Reading explorer 2. Boston, MA: National Geographic Learning.

23

MakarchukD. (2018). Recall efficacy in EFL learning. English Teach.73, 115–138. doi: 10.15858/engtea.73.2.201806.115

24

McAndrewM.MorrowC. S.AtiyehL.PierreG. C. (2016). Dental student study strategies: are self-testing and scheduling related to academic performance?J. Dent. Educ.80, 542–552. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2016.80.5.tb06114.x

25

McCabeJ. (2011). Metacognitive awareness of learning strategies in undergraduates. Mem. Cogn.39, 462–476. doi: 10.3758/s13421-010-0035-2

26

MiyatsuT.NguyenK.McDanielM. (2018). Five popular study strategies: their pitfalls and optimal implications. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.13, 390–407. doi: 10.1177/1745691617710510

27

MoreheadK.RhodesM. G.DeLozierS. (2015). Instructor and student knowledge of study strategies. Memory24, 257–271. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2014.1001992

28

MoreiraB.PintoT.StarlingD.JaegerA. (2019). Retrieval practice in classroom settings: a review of applied research. Front. Educ.4:5. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00005

29

RinellaH.PutnamA. (2022). The study strategies of small liberal arts college students before and after COVID-19. PLoS One17:e0278666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278666

30

RiversM. L. (2020). Metacognition about practice testing: a review of learners’ beliefs, monitoring, and control of test-enhanced learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev.33, 823–862. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09578-2

31

RoedigerH. L.IIIKarpickeJ. D. (2006). The power of testing memory: basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.1, 181–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x

32

RowlandC. A. (2014). The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: a meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychol. Bull.140, 1432–1463. doi: 10.1037/a0037559

33

SusserJ. A.McCabeJ. (2013). From the lab to the dorm room: metacognitive awareness and use of spaced study. Instr. Sci.41, 345–363. doi: 10.1007/s11251-012-9231-8

34

TajalliF.MoradanA.FarjamiH. (2022). Iranian EFL learners’ perceptions of collaborative versus individual testing. J. New Adv. Engl. Lang. Teach. Appl. Ling.4, 948–966. doi: 10.22034/jeltal.2022.4.2.5

35

TeraiM.YamashitaJ.PasichK. E. (2021). Effects of learning direction in retrieval practice on EFL vocabulary learning. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis.43, 1116–1137. doi: 10.1017/S0272263121000346

36

TullisJ.MaddoxG. (2020). Self-reported use of retrieval practice varies across age and domain. Metacogn. Learn.15, 129–154. doi: 10.1007/s11409-020-09223-x

37

WeissgerberS.RummerR. (2023). More accurate than assumed: learners’ metacognitive beliefs about the effectiveness of retrieval practice. Learn. Instr.83:101679. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101679

38

WissmanK.RawsonK.PycM. A. (2012). How and when do students use flashcards?Memory20, 568–579. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.687052

39

YangC.LuoL.VadilloM. A.YuR.ShanksD. R. (2021). Testing (quizzing) boots classroom learning: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull.147, 399–435. doi: 10.1037/bul0000309

Summary

Keywords

strategy use, strategy preferences, restudying, retesting strategies, rereading

Citation

Aljabri S (2024) Exploring EFL students’ preferences and practices of study strategies: repeated reading versus testing. Front. Educ. 9:1457504. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1457504

Received

30 June 2024

Accepted

05 November 2024

Published

28 November 2024

Volume

9 - 2024

Edited by

Javad Gholami, Urmia University, Iran

Reviewed by

Hariharan N. Krishnasamy, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia

Himdad Abdulqahhar Muhammad, Salahaddin University, Iraq

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Aljabri.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sameer Aljabri, ssjabri@uqu.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.