Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic is a social and economic crisis and a health issue, which stresses young minds and impacts their academics. Therefore, education during COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 has become a concern. Through this study, we intended to comprehend and explore the academic crisis of high school students and teachers during the pandemic and examine the learning loss after the reopening of schools.

Methods:

This research utilized the conservation of resources theory (CoR) as the conceptual framework to explore the internal and external resources involved in the school sector during the COVID-19 outbreak. Researchers employed inductive qualitative study based on the naturalistic approach. The focused group discussions aided in formulating the research design and conducting interviews with 25 teachers and 50 students. These interviews were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results:

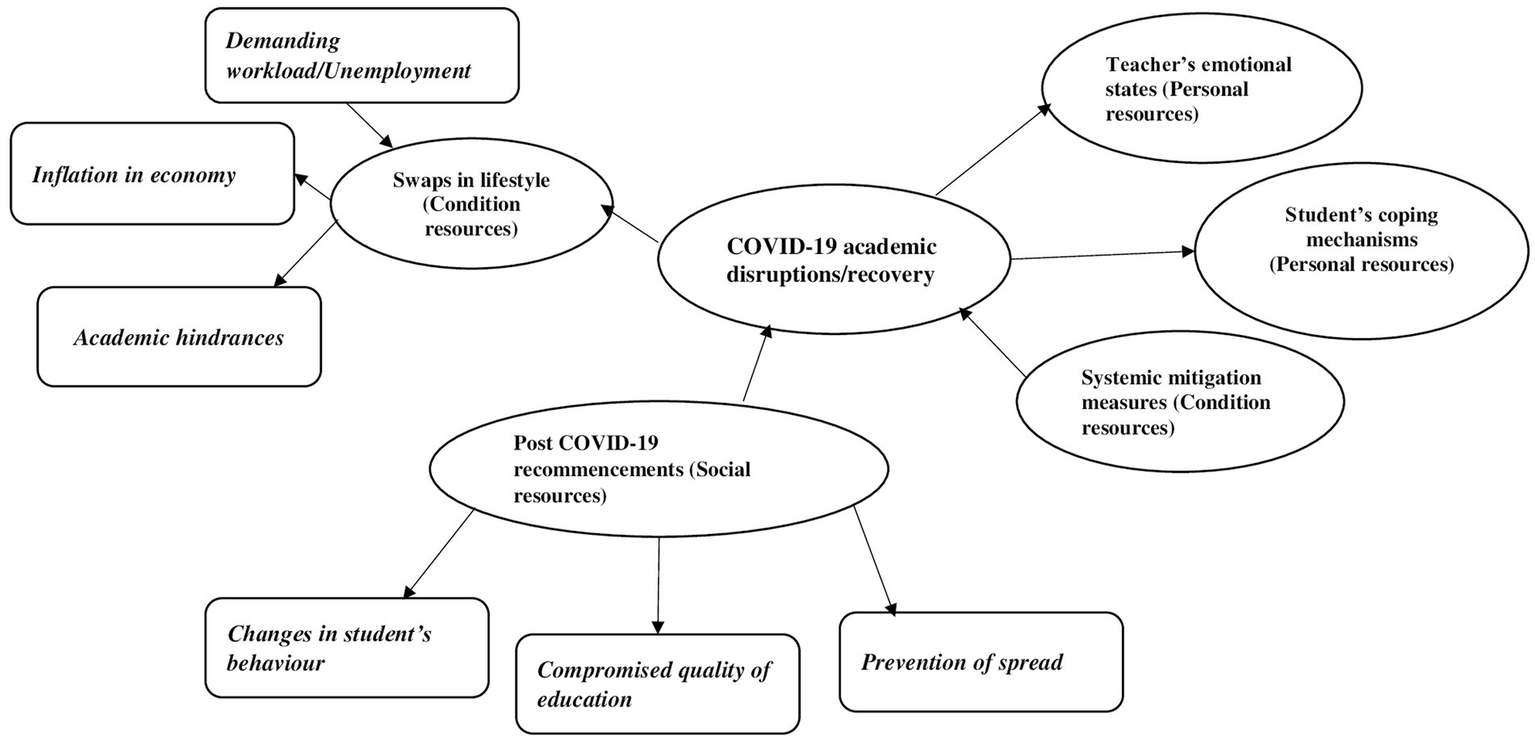

Researchers have extracted six themes, namely COVID-19 academic disruptions/recovery, swaps in lifestyles, teachers’ emotional states, students’ coping mechanisms, systematic mitigation measures and post-COVID-19 recommencements. Among these themes, the swaps in lifestyles theme have sub themes like demanding workload/unemployment, inflation in the economy and academic hindrances. Post COVID-19 recommencement theme consists of three sub-themes: changes in student behavior, compromised education quality, and prevention of spread.

Conclusion:

These themes show the impact caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on academics and the physical, mental, social and economic health of Nellore's government school students and teachers. Though this qualitative research cannot be generalized, the need for more recovery measures, strategies, policies, programs and funds from the government to deal with the instability resulting from the pandemic needs addressing.

Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 virus in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in late December 2019 was initially pneumonia characterized by fever, cold, cough, fatigue, and rare gastrointestinal symptoms, leading to a dramatic loss of human life and disruption of everything (Wu et al., 2020). The rapid spread of the virus affected numerous people during the months of its existence (World Health Organization, 2020). Most countries enacted lockdowns and social distancing measures to prevent the spread, resulting in the closure of schools, training institutes, and other education facilities (Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021). The Chinese government initiated a “Suspending Classes without Stopping Learning” 9strategy shifting to online teaching, which also became a hit in other countries (Sangeeta and Tandon, 2021).

Lockdowns have significantly impacted the global economy, affecting macroeconomic factors such as economic growth, unemployment, international trade, consumption, public expenditure, healthcare costs, and savings and investments. The rapid spread of the virus caused economic consequences worldwide owing to trade, travel and restrictions on tourism (Rathnayaka et al., 2022). Countries faced COVID-19 impact on their mobility, economy, and healthcare system directly, which indirectly affected the country’s education system (Shrestha et al., 2020). According to International Institute for Education Planning (IIEP) specialists, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant economic impact on education as a result of cut in educational spending, additional costs, and a reduction in future financial resources for the sector. In developed countries, school closures mainly disrupted the academic calendar and teaching-learning in future financial resources for the sector (Feyisa, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic forced educational institutions around the world to remote and online learning, presenting countless number of challenges for both students and teachers. This caused a huge negative effect on the educational development of secondary school students in Nigeria. This caused for the government to provide educational resources to low-income families as a recommendation (Omang and Angioha, 2021). Similarly, in India, there was a noticeable gap in teaching-learning opportunities between government and private schools. Students from urban areas had more access to online education than those in rural areas (Sarkar et al., 2023). This sudden shift caused difficulties for those with limited access to technology and internet connectivity. (Asher, 2021).

Students and teachers in low-resource areas faced issues like lack of access to technological infrastructure and devices for effective online learning (Abou Khalil et al., 2021). Unreliable internet connectivity and unstable power supply hindered students’ ability to participate in real-time online classes and access educational materials. This created barriers to the learning experiences of students. (Onyema et al., 2020, Abou Khalil et al., 2021).

The transition to online learning highlighted the digital literacy gap among both students and teachers (Cullinan et al., 2021). Many individuals, especially those from underserved communities lack the skills required to navigate and utilize digital learning platforms. This caused them to face more challenges in engaging with remote education (Asher, 2021, Cullinan et al., 2021).

Online learning also brought to light the imbalance in the home learning environments of students (Cullinan et al., 2021). Learners from disadvantaged backgrounds may not have access to a quiet, dedicated space for studying. They might also lack suitable devices or a stable internet connection. This would make it difficult for them to fully participate and engage in online classes (Asher, 2021, Cullinan et al., 2021). There are also reports of psychological issues among students in distance learning, such as anxiety, stress, and depression, as observed in Sumedang (Lindasari et al., 2021). In Pakistan, the pandemic has led to learning loss and school dropouts with girls being more affected than the boys (Khan and Ahmed, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic had a more profound impact on government high school students in India. The pandemic caused schools to close and shift to online education, which resulted in learning losses and inconsistency in access to education (Agarwal and Behera, 2023; Sarkar et al., 2023). Disparities in access to online education was observed among students from rural areas and those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds (Sarkar et al., 2023; Yadav, 2021). While some districts show improvements in learning outcomes, the overall effect weakened students’ learning at the district level, particularly in low- and middle-income regions (Agarwal and Behera, 2023). Although the transition to e-learning platforms was beneficial, it also presented challenges for institutions, teachers, and students, with government initiatives attempting to mitigate these issues (Kamal and Illiyan, 2021).

Interestingly, while the pandemic posed significant challenges, it also provided an opportunity to explore and adopt mobile learning (m-learning), which showed a positive impact on students’ learning satisfaction in some cases (Qamar et al., 2023). However, the negative effects were more pronounced in primary education, with a significant gap between government and private schools’ access to online education, especially in rural areas (Sarkar et al., 2023). The shift to distance education also impacted students’ social literacy skills, prompting a need for expanded distance education platforms (Alsubaie, 2022).

The pandemic has been a catalyst for educational institutions to adopt digital methods, with government measures providing smooth education. However, the negative impacts included disruptions to learning, reduced access to education, and increased student debts (Gupta and Gupta, 2020). The pandemic’s impact on socio-economically vulnerable children was particularly concerning, highlighting the limitations of policy interventions and the need for future strategies (Paik and Samuel, 2022).

Theoretical background

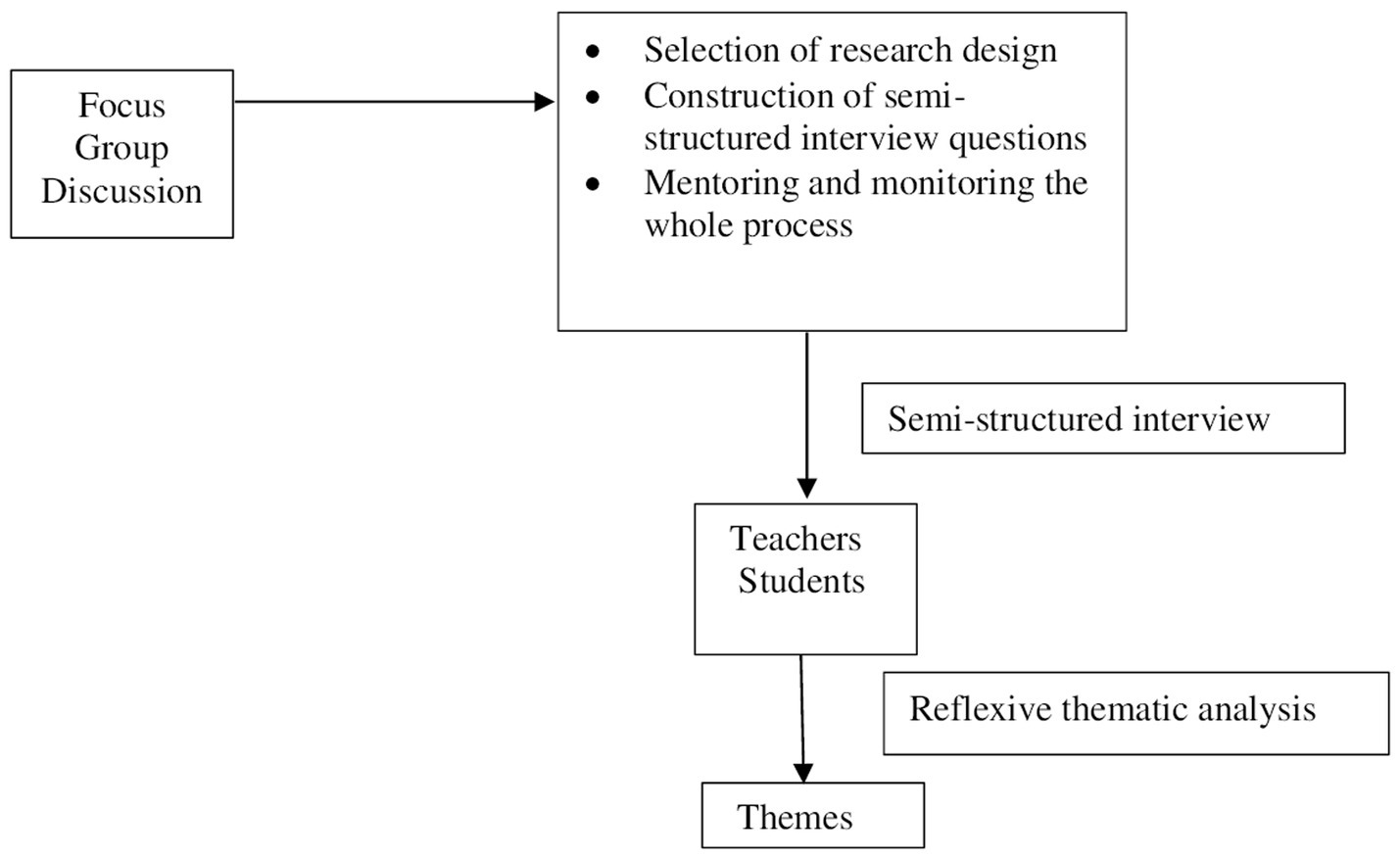

The Conservation of Resources (CoR) theory is a theoretical framework that support a loss of resources specific to the crisis and its impact on individuals or groups (Yu et al., 2023). The loss of resources may lead to a cascade of stress reactions or the issue of ability to cope with the losses. Cyberbullying, online learning anxiety, time management pressure, and academic distraction are potential stressors that resulted from the lockdown. Use of resources such as technology and family support may be associated with positive or negative reactions to online learning. The CoR theory recognizes that resource loss and resource gain are not equal since resource losses exert a greater impact than resource gains. This comprehensive perspective helps ensure that resource loss, resource investment, and resource gain are investigated when considering the impacts of online learning on students. Educational policy devising, public health, and welfare assessment typically fail to capture the heterogeneous impacts of social phenomena on individuals. The CoR theory may offer a perspective that aids the exploration of heterogeneous impacts. School closures were universal in many countries, though their consequences were heterogeneous across different schools, classes, genders, regions, and socio-economic backgrounds. Resources protect individuals from resource loss, aid in coping with resource loss and help recover from resource loss (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart depicting the workflow.

the principles of CoR theory, which focus on the stress associated with the loss of resources, can be extrapolated to hypothesize potential impacts on education. For instance, educators and students may have experienced resource loss in terms of disrupted routines, diminished social support, and increased workload, potentially leading to stress and emotional exhaustion (Phungsoonthorn and Charoensukmongkol, 2022).

Interestingly, while the context does not explicitly discuss education, it does highlight the broader psychological impacts of the pandemic, such as emotional exhaustion, depression, and stress, which could indirectly affect educational outcomes (Lee et al., 2021; Phungsoonthorn and Charoensukmongkol, 2022; Chen et al., 2023). For example, the emotional exhaustion of educators could impair their teaching effectiveness, while the stress experienced by students could hinder their learning and academic performance.

Job demands resource model would have been better fit for this research study, if the research focus is only on the workplace stress (Hsieh et al., 2022; Hsieh et al., 2024). Sense of coherence model emphasis on psychological resilience and does not incorporate the dynamics of the loss of resources and gaining which is the crucial factor in COVID -19 crisis (Sumathi and Elavarasi, 2024). Disruptive innovation theory is of systemic orientation than on the individual’s disruption (Jackson and Szombathelyi, 2022).

Though the CoR theory has been widely applied to understand the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on various aspects of life, including mental distress, chronic illness management, health risk behaviors, and the healthcare system, no effort has been made to look at its associations with the educational experiences of high school students. Hence, there is a need to analyze the impact of this pandemic on the education of government high school students in Nellore, India using the CoR theory. The present study attempts to fulfill this gap through a qualitative exploratory research approach employing interviews and focus group discussions, and data analysis employing deductive thematic analysis, and the CoR theory (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Thematic representation of the impact and recovery measures of COVID-19 in government schools.

Methods

Study design

This was an inductive qualitative study based on the naturalistic approach, which seeks to understand the perspectives and experiences of participants without manipulating their real setting and carrying forward with observations, interviews or case studies (Sharaievska et al., 2022). The investigation started with focus groups, followed by semi-structured interviews, and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Byrne, 2021). The focus group consisted of researchers, psychologists, counselors, and academicians, and their operational guidance and suggestions contributed to the core of this study. Their collaborative efforts ensured a systematic structure by providing more theoretical and practical suggestions. Their guidance and support played a major role to gain permission from IRB and conduct the study with all ethical considerations fulfilled. During pilot testing, their expertise aided in reframing the questions and introducing reflexive thematic analysis in the picture. Focus group members also served as raters to ensure the validity of the codes and themes derived. Overall, they served as the guiding pillars of this study (Table 1).

Table 1

| Phases | Description | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Data familiarization | Understanding and analyzing data in depth. Examining and forming patterns and meanings. | Transcribed the audio data collected by reading and revisiting the notes taken. |

| Initial code generation | Creating initial codes to organize the data, keeping a close eye on each data item. | Labeled and categorized data into meaningful groups. |

| Generating themes | Organizing codes into initial themes. Identifying the meaning of initial codes and their relationships. | Defined the properties of themes and mapped them. |

| Reviewing themes | Detecting coherent patterns in coded data and examining the entire data set. | Omitted data overlapping and ensured that collected data was sufficient. Themes are reworked and refined. |

| Defining and naming theme | Determining the story behind each of the identified themes, fitting the larger story of the data set to the research | Links between the themes are formed as a cycle to organize the data. |

| Report production | Presenting the whole story of data in a concise and presentable way. | Creating a persuasive argument that addresses the research questions extends the writing beyond simply describing the themes. |

Table depicting the process of reflexive thematic analysis.

Settings

The researchers conducted the study after the second wave of COVID-19 and during the reopening phase of the lockdown (Aug 2021- Feb 2022). During this time, the government had just reopened schools after the second wave, and all students, teachers, and management were still struggling to settle entirely due to the change in the learning atmosphere. The researchers collected data from three cooperative schools in Andhra Pradesh, Nellore district, during mid of August 2021, using purposive sampling because of the COVID-19 spread and the strict regulations that existed at that time. The researcher secured permission to conduct research on their premises. Participants, cognizant of the researcher’s familial and educational background, expressed appreciation for the investigator’s earnest pursuit of comprehending the ramifications of COVID-19 on their academic milieu. Eager to articulate the challenges endured, participants actively sought to share their experiences, with the primary aim of garnering support to address the hardships faced during this period. This made researchers joyful as all the participants exhibited sustained interest throughout the study with no instances of dropout (Table 2).

Table 2

| Codes | COR theory | Theme | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 precautions Pedagogical alterations Students’ behavioral changes |

Disruptions in both internal and external resources | COVID-19 academic disruptions/recovery | COVID-19 created a depletion and disruption in both internal and external resources and how the whole education system functions to mitigate the gaps |

| Unemployment Scarcity of raw materials High tech utilization Workload School dropouts |

Upheaval in internal resources | Swaps in lifestyle | Participants were pushed to reshuffle their regular behaviors and embrace a new lifestyle to survive COVID-19 |

| Burnout Stress Fear Depression |

Distortion mainly in the internal energy resources | Teachers emotional state | Due to the lack of resources both in personal and profession spaces, teachers faced a plethora of emotions affecting both their physical and mental health |

| Hike in internet pastime Enrolling in courses Addictive behaviors |

Fluctuations in usual personal resources led to both positive and negative adaptation of resources | Students coping mechanisms | Students tried different personal resources to structure their ample free time resulted by COVID-19 |

| Online classes Challenging concerns on internet availability Delayed resource supply from the government |

External conditional resources got distorted and led to a systemic change | Systemic mitigation measures | Government created plan, strategies, activities and budgets to balance the vacuum caused by COVID-19 |

| COVID-19 safeguard measures Teaching/ learning alterations Drop in quality of education |

Mix of influences in the supply of external social resources noted | Post-COVID-19 recommencements | Though recommencement measures were in place post-COVID-19, decline in quality of education and health factors were well-pronounced |

Matrix connecting codes, themes and CoR theory.

The author provided the research questions only after pilot testing. Based on the focus group’s recommendation, authors carried out a pilot testing interview with three students and two teachers. This pilot testing helped to understand the practical problems based by the participants and authors reframed the interview questions based on it. For instance, authors came to know about the delay in the government resources to the schools through this pilot study which later got converted into a question like, “How did the government support during the pandemic toward continuity of education?” This pilot testing also assisted in removing questions which are not that relevant to the study which enhanced the focus and quality of the process. This testing gave an opportunity to understand the requirement of a robust thematic analysis which led to the incorporation of reflexive thematic analysis. No repeat interview was carried out and data saturation was taken into account as the research was conducted during the lockdown. The transcripts were reviewed by the participants and expressed immense satisfaction with the accurate representation of their hardships (Table 3).

Table 3

| Theme | Description | Sub themes |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 academic disruptions/recovery | Portrays how the pandemic disrupted the education sector from the point of view of students and teachers | |

| Swaps in lifestyle | Explains how the pandemic has impacted various sectors and how it has indirectly changed the lifestyle of students and the teachers | Demanding workload/unemployment Inflation in the economy Academic hindrances |

| Teachers emotional state | Illustrates the challenges the teachers faced and the emotions resulting from it. | |

| Students coping mechanisms | Picturizes what the students did to manage the impact of COVID-19 on them | |

| Systemic mitigation measures | Emphasis on how the education system and government as a whole took measures to mitigate the downfall | |

| Post-COVID-19 recommencements | Summarizes what were the concerns after the pandemic and how they got solved in the field | Changes in student behavior Compromised quality of education Prevention of the spread |

Themes and their description.

Participants

A total of 75 participants were interviewed, of whom 25 were teachers and 50 were students. Researchers recruited teachers using purposive sampling because of shifts in their personal lives and health issues triggered by COVID-19. Apart from individual problems, the government allocated the same teachers to different schools to compensate for the deficiencies of teachers. All teachers were Bachelor of Science (B. Sc) or Bachelor of Education (B. Ed) graduates aged 22–62 years. Of the 25 teachers who participated, seven were female and 18 were male. High school students from 6th to 10th standard, ages 11–16 years, also participated in the interviews. However, there were many absentees and school dropouts due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the 50 students who participated, 30 were female, and 20 were male. Researchers focused more on the 10th standard as it is the game changer in students’ lives and obtained the maximum number of participants from that class compared to others.

Procedure

Considering their availability and requests, the researchers conducted interviews on the school premises, recorded them, and gathered field notes. The interviewees took 30–45 min to complete their sessions, and most spoke their native language, Telugu. The researchers recorded the interviews with each participant separately and gathered field notes. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and taken adequate care to remove any identifying information that could compromise participants’ privacy. The result was a complete transcript that allowed coding and finalizing of themes (Braun and Clarke, 2019).

Data management

Two peer researchers and one co-author who knew Telugu listened to the audio recordings from the interviews, transcribed them, performed the coding, and extracted themes. Later, researchers submitted the extracted themes to the focus group to analyze and generate the final themes. Collaboration during coding and theme development helped ensure a holistic outlook, making the results significant.

Ethical clearance

Researchers gained clearance from the Ethics Committee, Amrita Vishwa Vidhyapeetham, Coimbatore, India on 1st of Jan 2023 (File no: AMRITA/SOE/ADMN/DOE/01/2023/01), and also received special permission from the school administration by promising to follow the COVID 19 protocol throughout the interviews. The researchers announced confidentiality, and informed consent was obtained from all participants before the process. The school authorities suggested the researchers that verbal consent from parents would be appropriate as it was COVID 19 time and informed parents of participants about the research and obtained verbal consent gathered with the help of the school pupil leader and the class teachers noted and documented. This approach aligns with established ethical standards for research involving human.

Braun and Clarke (2019) reflexive thematic analysis was used in this study by applying their six-step guide mentioned below to the collected interviews as follows:

-

Familiarity with the data is an essential step in conducting the study; therefore, the transcribed data were read and reviewed multiple times with the noted initial idea. The researchers included field notes with the ideas, essential specifications of the participants, and the participants’ general feelings during the pandemic for analysis.

-

Codes were formed from accurate data collection and identification of the critical chunks in the data related to the research questions. The codes generated are referred to multiple times, whereas only a few significantly affect the data.

-

By examining and clustering, the code developed into broader categories and initial themes reflecting the pattern of meanings. The primary goal of this stage was to identify potential themes and reflect on participants’ emotions and experiences.

-

Back-and-forth process of reviewing and refining themes was necessary to check the connection with the data. Specific themes were segmented into themes, and a few were omitted.

-

The reflexive thematic analysis continued by assigning clear definitions and names to the themes that evolved, and this stage helped to validate the methods used and their results.

-

The themes got finalized while incorporating analysis, evidence, and context.

Focus group members oversaw the reflexive thematic analysis process. Among the members, two of them were well versed in the native language of Nellore-Telugu and they served as inter-raters and assisted the authors in coding and theme extraction process. Their suggestion from inter-rater validity enhances the reliability of the derived results by reducing the individual bias and connectivity of CoR theory and the study. After reviewing the data in focus group discussions, researchers agreed upon the following: Theme 1: COVID-19 academic disruptions/recovery, Theme 2: Swaps in lifestyle (Sub theme 1: Demanding workload/unemployment, Sub theme 2: Inflation in the economy, and Sub theme 3: Academic hindrances), Theme 3: Teachers’ emotional states, Theme 4: Students’ coping mechanisms, Theme 5: Systemic mitigation measures, and Theme 6: Post-COVID-19 recommendations (Sub theme 4: Changes in student behavior, Sub theme 5: Compromised quality of education, and Sub theme 6: Prevention of spread). The sub themes derived here adds vigour, clarity and transparency to the concerned main themes like 2 and 6. Additionally these sub themes bring out specific variations with logic intact to it. As a result of the amalgamation of diverse viewpoints and expertise, this study’s contribution to the current literature and its research outcomes may be validated.

Results

Theme 1: COVID-19 academic disruptions/recovery

This study focuses on the massive implications of the COVID-19 outbreak on students and teachers’ academic environments. The participants expressed variations in their functional routines due to the pandemic and their consequences.

Teacher:

Male: “Going to school, teaching students, spending time with colleagues, all these were our daily routine. However, the pandemic disrupted it and made us exhausted by learning and adapting to new technologies. Nevertheless, we now wish that all our comradeship will return soon.”

Female: “I never thought we would be in a scenario where everyone is cooped up in their houses and barely interacts with the outside world. The pandemic experience became more frightening because we belong to the middle class; we went through health and financial issues then; however, support from the close ones made the struggle bearable.”

The emergence of COVID-19 has caused significant upheaval in educators’ lives, resulting in formidable personal and academic obstacles. The pandemic has had many adverse repercussions, ranging from the threat of unemployment and emotional turmoil to financial ruins, illnesses, and educational breakdown. The imposition of lockdown measures exacerbated the situation by preventing teachers from performing their duties and attending school.

The students articulate their apprehension by imparting their experiential knowledge.

Girl: “Pandemic scared me; I was more concerned about my academics and many daily routines. My parents did not have money to pay the rent and bills and afford groceries. I did not have a mobile to attend online classes too.”

Boy: “First wave of the pandemic just went by. Nonetheless, the second wave came with deaths, hospitalization, lockdowns, and financial crisis. Fear of COVID-19’s spread made my parents strict and prohibited me from playing. I could not focus on online classes and was academically behind my friends.”

The pandemic impeded students’ academic lifestyles, with schools closing and students being confined to their homes. Studies like (Lee et al., 2021) coupled these restrictions with decreased academic performance during the pandemic. This shift can be due to various factors, including learning difficulties during the pandemic, social isolation, and limited student-teacher relationships. They reveal that COVID-19 has significantly hindered individuals’ academic activities and other tasks during this period.

Theme 2: Swaps in lifestyle (Condition resources)

Participants’ accounts included many unprecedented personal experiences that hindered their daily routines. This theme related to the first identified theme and comprehended the challenges of employment loss, economic uncertainty, and academic difficulties due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sub theme: Demanding workload/ unemployment

Teachers faced significant work pressure during the pandemic because they had to handle the challenges of their professional responsibilities and personal and professional instabilities caused by the crisis. When asked about their work during the period when students were not present in the school, teachers reported that:

Female: “Though I did not know to use new technologies, I somehow managed to learn and conduct online classes. It was difficult for me to get help; finally, my son helped me create WhatsApp groups for all my sections. I shared resources and references and even evaluated students through online submissions.”

Female: "Our working schedule completely changed; it was tough to report to school amidst the lack of buses and ever-rising COVID-19 spread. The government did not bother about our concerns and made us work during even non-working hours.”

Before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was common for teachers to work eight hours per day and dedicate two hours to planning. In reaction to the pandemic, however, educators worked tirelessly, both on-site and remotely, devoting a substantial amount of time to lesson planning, assessment creation, reference checking, and progress reporting to the Headmaster and Chief Educational Officer. Notably, the additional responsibility of managing household obligations with family members in the home amplified the burden for female teachers. Because of these challenging circumstances, educators prefer traditional learning models to hybrid ones.

Online learning is a novel pedagogical approach in which students face enormous workloads. Furthermore, online learning is not readily accessible to everyone, culminating in double work for many students and teachers. When asked about their work pressure, a boy stated.

“I love my school and enjoy most classes, but the pandemic changed everything. I could not access or buy smartphones or computers, and many like me did not attend class. However, some of our friends helped in group studies and lending their notes, but it was insufficient.”

The abrupt evolution of remote learning poses enormous challenges to learning and adaptation for students. Longer study hours and deep concentration of mentally and physically was taxing for the students. Furthermore, students discovered that factors such as limited access to resources, unsuitable study environments, and more distractions at home harmed their academic performance. All these are the result of facing parental unemployment.

Student:

Boy: "In the first phase of the pandemic, my father lost his job, and he used to work under a contractor. He experienced much emotional distress at home, leading to several fights.”

During the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people, including educators and parents, were unemployed or experienced a lack of compensation.

Sub theme: Inflation in economy

The COVID-19 epidemic has had a significant negative impact on India’s economy. This affects all sectors, leading to family economic inflation. This theme focuses on students’ and teachers’ financial experience.

When asked about their financial situation during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their academic pursuits, the student participants shared various stories, including a significant disruption in their financial stability, resulting in inflationary pressure within their households. One boy student said:

“I lost my father during COVID-19, and I have a mother and an elder sister. My mother works as a servant in a few houses, but recently she fell ill and cannot work much, so I help her with all the household work, and to support the family financially, I work in a mechanic shop post-school hour.”

According to the data gathered about their financial circumstances during the COVID-19 pandemic, most participants reported enduring inflationary pressures in their homes. When asked about the impact of the pandemic on their financial stability, teachers said:

Male: “I found it hard to manage finances during the pandemic due to the irregularity or delay in getting our salary. One of my friends went to manual labor to pay his EMI. In my case, there were days when my family and I could not access the basic raw materials, provisions and vegetables, which led to food scarcity.”

The education industry is a vital contributor to India’s economy, because it assists in maintaining human capital, boosting productivity, and fostering creativity, reducing poverty, and empowering women. However, the pandemic has had a detrimental effect on all these factors.

Sub theme: Academic hindrances

The prolonged closure of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a surge in school dropouts. Unemployment and economic inflation has emerged as significant factors that contribute to this trend. Although online learning is a viable alternative to ensure continued academic progress, the financial feasibility of this option remains restricted to a few selected families. Several households’ financial difficulties compelled numerous students to withdraw from private schools and join government schools. In some cases, economic hardship has forced male children to seek employment on farms or in cities to support their families, resulting in the discontinuation of their education and migration from their native place. In rural areas, the societal belief that marrying off a girl child is a burden and a significant responsibility during the pandemic has led to the early marriage of many young girls, thereby depriving them of the opportunity to pursue education (Tsolou et al., 2021).

Theme 3: Teacher’s emotional states (Personal resources)

Teachers experienced a wide range of emotional states, including but not limited to sadness, panic, worry, stress, loneliness, and depression, while navigating new circumstances during the pandemic and post-reopening period. A teacher who participated in the study reported:

Male: “As a man and head of the family, I must have a strong mental attitude to help my family during difficult circumstances. I cannot show my vulnerability directly to my wife; if so, she will become weak. However, this pandemic made me more vulnerable and incapable. At one point, I was too exhausted and depressed to manage my personal and professional life.”

Emotional fluctuations among teachers might have significantly impacted their work, hindering their planning and exploration of new things. Many teachers observed it. This raised the question, ‘How did you emerge and evolve from that phase?’ for which a participant said:

Male: “I was heartbroken due to the financial crisis, workload, and COVID-19 spread. My wife helped me remember our past struggles and how we overcame them. She told me that although it was a tough phase, we could face it; otherwise, our children would suffer. Her words reminded me and gave me strength.”

The teachers claimed that their ability to overcome adversity and develop self-assurance was due to familial bonds and responsibilities, which facilitated positive and gracious actions, implying that an individual’s vulnerability allows them to face genuine life challenges.

Theme 4: Students’ coping mechanisms (Personal resources)

Researchers inquired with students about their strategies to manage academic responsibilities at home, and the respondents indicated various coping strategies, for which they had comprehended:

Boy: "We took online courses, took notes, and enlisted the assistance of our older siblings to comprehend and finish the tasks.”

Girl: "I have created a schedule for studying and playing games. Every day I study for 3 h in the morning and play in the evening for 2 h. I have downloaded textbooks from the Diksha app and studied. I used to call my friends or teachers for clarification.”

Boy:"I did not have access to a smartphone, so I visited the tutoring point close to my house instead of the online sessions.”

Boy: “Even though I attended online classes, I did not comprehend, so I used to lend my friend notes or discuss with him daily; he lives near my house.”

Time management, assistance from external tutoring points, and support from family members and teachers have helped students manage their academics during the pandemic. However, many students experienced emotional instability, so when asked about coping mechanisms to handle them (She et al., 2021), they said:

Girl: "I felt so bored and lonely during the pandemic because I could not go out and play with friends; instead had to stay home. However, I learned cooking and tailoring from my mom. It became a hobby to stitch and experiment on clothes now.”

Boy: "I played video games at home with my friends online.”

Boy: "I am interested in coding, so, during the pandemic, I enrolled in free courses in Coursera and learned.

HTML and some basic coding.”

Despite experiencing emotional fluctuations during the pandemic, people tend to explore their interests and pursue passion while staying at home. This propensity has aided skill acquisition, emotional well-being, and stability. In thinking about the negative coping mechanisms of students, teachers enlisted a few concerns they had to learn from parents.

Teacher:

Female: “I heard from many parents that their child misused phones by saying they are attending online classes, but instead was using adultery sites.”

Male:“Parents told me that their child became addicted to online video games and on phones 24/7.”

During the pandemic, many students, particularly boys, experienced the age of adolescents and exploited the opportunity to utilize smartphones for adultery intrigue and gaming (Serra et al., 2021).

Theme 5: Systemic mitigation measures (Condition resources)

Educators have implemented novel pedagogical approaches to address the resulting learning gap in response to the pandemic’s disruption. When asked about the efficacy of the newly adopted methods, participants stated the following.

Teachers:

Female: "The Doordarshan classes were an excellent option, but it was not helpful for all the students; most always wanted to have fun. Those playful ones give us a big headache in regular classes itself.”

Students:

Girl: “The classes helped keep track of the subject content. We wrote running notes, shared them with friends, and discussed our doubts. Our faculties also helped us a lot during this period, and we shared our doubts on WhatsApp and got them clarified.”

Boy: “I have attended the broadcast classes for the first few days. It was fast, so I lost interest and needed to understand more. However, online classes later continued, and it was ok.”

The government implemented broadcast learning as an initial measure for virtual learning, with classes being conducted from 6th to 10th standard according to a released schedule. This implementation permitted students to maintain continuity while learning subjects from the comfort of their homes. Because television was available in most households, many students took advantage of it and communicated with their teachers through WhatsApp. However, students had mixed feelings about the effectiveness of broadcast learning, with some finding it difficult to keep up with the pace of instruction, and as a next step, using Zoom as a medium, virtual classes were initiated.

The government implemented online classes as a viable option to maintain academic continuity and prevent the spread of the pandemic. Nonetheless, the implications of this approach have resulted in several practical inconveniences and challenges that cannot replace traditional learning methods.

Teachers:

Female: “Zoom classes came in handy. We could take classes from the comfort of our homes. However, internet and electricity bills raised. The student’s family members’ intrusion was a nuisance. Once a granny came online and fought with me that I was not allowing her grandson to eat and kept taking classes.”

When asked students about their experience with the online classes, they reported that,

Girl:” I was very depressed and bored at home after the lockdown. Though online learning was refreshing, we missed the interpersonal connection of regular classes.”

Not all students have benefited equally from online classes, as access to the right resources is considered a crucial predictor.

Specifically, only a limited number of students had access to cell phones, textbooks, and reference books, thus limiting the availability of resources. Furthermore, teachers have identified that students’ zeal, evident during the initial phase of online classes, lasted only for a short time. Students experienced boredom and difficulty comprehending after a few lessons. Although online learning is an accurate and adaptable solution, students and teachers encounter challenges in adapting to and complying with this process (Ponce et al., 2023). The low resource accessibility and instability during the classes made us ask, ‘What were the troubles you faced, and how did you resolve the issues?’

Teachers:

Female: "Since many of my students are from poor and uneducated families, they do not have a proper atmosphere at home and have lost their mental health. Some contacted me and shared their issues. Student attendance also dropped low; I once had six out of fifty students attending.”

Male: “Our principal has arranged phone stands and network connections in school to conduct classes. We asked students to turn on their videos to make the classes more engaging and responsive.”

The primary impediment teachers encountered in conducting online classes was a need for more understanding and application of technology, which the government anticipated and remedied by providing technology training sessions to teachers, including learning about the scheduling of virtual meetings and sharing of relevant links. However, the lack of equality in resources among students is another drawback that affects their attendance.

Students:

Boy: “I did not understand much in the online classes, so I used to attend tuition near my home.”

Girl: “Teachers conducted online classes at our convenience, sometimes at night, as our parents will be at home and we can use their mobile. The teachers were amiable. The government started providing laptops for us under the ‘amma vodi’ scheme to attend classes; this is a huge help from the system.”

Students had mixed feelings regarding the effectiveness of online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. The government also helped and encouraged the students to implement new programs. Although good intentions initiate all systems, the result may sometimes be less than 100%. However, students were able to get some connections with the learning aspects, which prevented them from going wayward. The task of recovering from the two-year pandemic presents significant challenges that must be addressed after some time, necessitating the government’s implementation of well-planned and strategic mitigation measures. Furthermore, the government focused on implementing preventive measures to limit the COVID-19 spread in educational institutions.

Sub theme: Changes in student behavior

After a prolonged period of at-home study and exposure to novel experiences, significant alterations in students’ cognitive and behavioral patterns may have occurred. So, when asked, ‘Is there any change in student mindset before and after the pandemic?’ teachers said:

Female: “Students wanted to exercise their independence and did not follow instructions. Their concentration ability has taken a big hit during the lockdown.”

Male: "There is no punctuality and discipline in many students; after returning to school, many students are naughty and disturb the class. They became very lazy. During the pandemic, some students faced emotional problems like distress, loneliness, and laziness.”

During the interviews, we learned that the students’ motivation and productivity levels had declined, which they attributed to their perceived sense of laziness. Furthermore, several male students engaged in disruptive classroom behavior, posing a significant challenge to teachers in maintaining appropriate classroom decorum (Baysal, 2021).

Sub theme: Compromised quality of education

Due to time constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers either omitted specific concepts or accelerated their delivery to finish the academic year within the allotted timeframe. These issues have raised concerns regarding pedagogical changes after reopening. So, when asked, ‘Do you think you need new teaching methods to handle the students after the pandemic, and what are they?’

Teacher:

Female: "Regular classes are enough to bring back the academic standards. I will concentrate on the fundamentals of the subjects and conduct more assessments. I may also think of hybrid learning using Projectors and LCDs in offline classes.”

Male: “All of us, not only students, have changed into different personalities after the pandemic. I even experienced more stress and felt irritated. Sometimes, I did not want to take classes and felt sleepy most of the time. Sometimes I feel like yelling students’ genuine doubts.”

Quality of education is not only based on the content delivery of teachers but also on their mental health. Most teachers reported that they could not function to their full potential and felt like they were just passing their time. These narratives indicate the need for mental health measures. This pedagogical approach is expected to be reinforced further by the government’s allocation of technological resources and computer labs to schools, allowing students to access various online learning tools and platforms.

Sub theme: Prevention of spread

When queried, “What are the preventive measures to stop the COVID-19 spread?” participants stated the following.

Teachers:

Male: “The management is sanitizing the school premises daily after school hours and following the SMS principle even while teaching. However, sometimes, there will be one or two COVID-19 cases, and we send them back home even if anyone has a cold or fever.”

Student:

Boy: “I wear masks and sanitize my hands after every period; some friends mock me. I hope these preventions will save my family and me from COVID-19.”

Many students mentioned that following precautions hindered their learning and teacher’s teaching process. What made us ask, ‘What are the troubles faced in following the prevention measures at school?’

Teachers:

Female: “Since we wear masks while teaching, we must scream to be audible to the students. This screaming is causing us throat pain and cough. Many students are disturbing classes by making noises, and we cannot recognize them as they are wearing masks.”

Male: “Following social distancing in classrooms is tough because there are not enough classrooms to accommodate everyone. So, I conduct classes in an open area.”

Student:

Girl: “Though the mask is for good, I hate to wear it. It induces sweating and creates difficulty in breathing.”

Despite the significant challenges posed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the academic community has displayed impressive resilience and adaptability in navigating the obstacles of the crisis, ultimately forging ahead with its intellectual functioning.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the education sector worldwide by temporarily closing all educational activities (Rani and Prasad, 2022). This sudden and unexpected emergence of the COVID-19 global pandemic created significant uncertainty about the future of education, requiring teachers and students equally to adapt to a new normal to function in the new educational ecology (Bozkurt et al., 2022).

This study aimed to investigate various resource losses and recommendations for government high school students and teachers in Nellore, India. The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory serves as a framework for comprehending the effects of pandemic-related academic disruption, loss of employment, economic inflation, and emotional distress experienced by participants. This theory suggests that such events can adversely affect individuals’ mental health because of the depletion of their resources (Yu et al., 2023). Thus, this study explored the direct effects of school closures resulting from the pandemic on government school students and teachers in India.

Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, India’s education system has successfully implemented measures to ensure learning continuity, serving as a model for developing countries. This study can be used as a model for future research, allowing for a comparative analysis of digital education practices worldwide with India and providing recommendations for future progress. In the present study, we examined the academic experiences of government school students and faculties in Nellore District, Andhra Pradesh, India, during the COVID-19 pandemic and how the national lockdown impacted their educational system. The researchers conceded the gravity of academic setbacks caused by COVID-19 and devised a qualitative research design using reflexive thematic analysis. The semi-structured interviews collected from 75 participants resulted in the extraction of six themes and subthemes, namely, COVID-19 academic disruptions/recovery, swaps in lifestyle (three sub-themes: demanding workload/unemployment, inflation in the economy, and academic hindrances), teachers’ emotional states, students’ coping mechanisms, systemic mitigation measures, post COVID-19 recommencements (three sub-themes: changes in student behavior, compromised quality of education, and prevention of spread).

According to the Primacy of Loss of Principle, resource loss is asymmetric and noteworthy compared with resource gain (Hobfoll et al., 2018). The transition to remote and digital education has presented difficulties for both teachers and students, resulting in problems such as decline in learning outcomes, restrictions in teaching methods, technology-related obstacles, and worries about mental and emotional well-being. These difficulties are exacerbated by disparities in the distribution of educational resources and inequalities stemming from socioeconomic circumstances, gender, race, learning capabilities, and physical health conditions (Tang, 2023). Swaps in lifestyle (conditional resources) themes represent a sudden shift in the pedagogical approach during the pandemic, which was challenging, burdensome, and unequal. Virtual learning has rapidly expanded as an alternative mode of solid and high-quality education, considering student satisfaction as essential (Abirami and Radhika, 2022). The government and educationists can present student communities with different resources. They had difficulty adapting from social isolation to digital education, which led to low academic performance and distress. Students worried about academic hindrances (quality of classes, home study environment, examinations, college admissions), social and recreational activities (lack of socializing and sporting and leisure activities), and physical health, fitness, and safety compared their concerns with gender distinctions (Shukla et al., 2021).

A study by Hegde et al. (2022) inferred those 16 positives and 14 negative hindrances affected students’ academic and mental health during COVID-19. The second principle of the CoR theory implies that individuals must invest more resources to balance their losses (Hobfoll et al., 2018). The students’ coping mechanism (personal resources) theme explored the resources that aided them in overcoming their hindrances during the pandemic. Using a smartphone as a hinge, they intended to analyze their interests and enhance their knowledge in various fields. Mobile learning has a positive and constructive influence during the pandemic (Alturki and Aldraiweesh, 2022). Their innovative ideas, tricks, and tips connect them with their friends and family relations (Senniyappan et al., 2021). In addition to school students, undergraduate and postgraduate students also encounter learning difficulties identified by an intelligent tutoring system built by Mithun et al. (2020).

Teachers’ emotional states during the pandemic wavered due to many factors that affected their professionalism and mental health. Challenges such as a lack of digital skills, a favorable environment at home, social isolation, and stress affected their mental health. Our findings are similar to those of a study in which students’ and teachers’ low engagement during classes was due to low resources, skills, and opportunities (Singh and Meena, 2022). These conflicts caused by the lack of work-life balance decreased teachers’ productivity (Nayak et al., 2022). Family management was not attainable during the pandemic, particularly for women, making them anxious. These gender differences in work-life balance challenges were associated with higher work-related stress and COVID-19 (Leo et al., 2022). The Gain Paradox principle implies that if the focus is on the context of resource gain, the loss will lose its value, and more prominence is implied in the resource gain (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Optimism, acceptance, and emotion-oriented strategies such as humor and positive reframing help them cope with the stress caused by pandemic-induced education (Garcia and Revano Jr, 2022).

Many challenges and concerns raised post-COVID-19 have impacted student education and life. The compromised quality of the education theme is due to the rush to complete the syllabus by compromising quality. The pandemic has impacted students’ academic performance, as they have become disconnected from a structured academic environment. It has several negative consequences, such as increased late submissions and lack of concentration, leaving the same impact in the early post-pandemic period (Zheng and Zheng, 2022). Under the ‘amma vodi’ scheme, the Andhra Pradesh government supplied laptops to students above class 9th in the academic year 2021–2022. A special team, ‘AP technology services (APTS),’ is appointed as the central organization for soliciting bids and buying laptops. During tough times, to maintain prevented the spread of post-reopening significant priorities and took necessary measures to implement the rules and restrict the education flow, the government, school management, teachers, and parents were the main pillars of the system. The government the spread. These measures also caused disruptions in classroom activities. It is more difficult for primary school teachers to follow COVID-19 restrictions and particularly difficult for younger students with special needs (Marchant et al., 2022).

The themes evolved from this research have portrayed the losses and recommendations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic among high school students in Nellore, India. The fourth principle of CoR theory, the Desperation principle, is that when individuals lose their resources, they will lose their psychological equilibrium and exhibit unusual behaviors. Although we could note the resources gained from internal and external areas, the question is whether the gained resources have brought the required balance. The pandemic resulted in lifestyle swaps among students and teachers, leading them to experience heavy workloads/unemployment, economic inflation, and academic interruption. Teachers experienced fluctuations in emotions, implicitly affecting their planning and professionalism. Self-efficiency, time management, and exploration helped students cope with academic hindrances and emotional instability at home. The implications of online and broadcast learning did not benefit many students and left mixed opinions due to a lack of resources and unequal resources with students. Implementing well-planned and strategic mitigation measures post-COVID-19 may result in the management of the classroom decorum, educational quality, and safety of students and teachers. As stated in the hypothesis, resource losses and recommendations resulted from COVID-19 for students and teachers of Nellore, India’s government school.

Limitations, implications and recommendations

Researchers have collected data in a major city of Andhra Pradesh and have yet to cover the interior villages of India due to the prevailing COVID-19 restrictions. India is a developing country; many rural areas are severely affected, and the number of students dropping out may increase alarmingly. Thus, we recommend that inquisitive researchers worldwide devise research strategies considering socioeconomic status, geographical location, and structure of society. The role of these factors in the academic sector should also be considered. This study has highlighted the core issues of the academic sector during a pandemic, and these data could be a rich resource for policymakers and researchers.

Reflexive thematic analysis is a flexible approach that might lead to illogical and incoherent themes affecting the entire study. Researchers consulted a focus group team to minimize this limitation of reflexive thematic analysis, and their supervision assisted in creating a coherent thematic map. Although this study has examined the experiences of teachers and students, the results cannot be generalized because we covered only a district from a single country. As the COVID-19 predicament is faced by the education sector worldwide, identifying each country’s culture-specific needs would be helpful.

Incorporating the CoR theory aids in understanding the individuals’ object, social, condition, personal and energy resources. The CoR theory highlights the essentiality of glimpsing stress through the cultural lens, giving less priority to individual factors. The key is to develop a holistic view in calculating the elements of self, others, and the environment, prioritizing culture. Introducing new resources into the lives of teachers and students is required to manage the swaps in lifestyles induced by the pandemic. Teachers’ emotional fluctuations can be addressed by providing counseling and training sessions. Although the students had temporary coping mechanisms, capacity and skill-building programs will create development in them. Since the resource supply and knowledge of how to use the resources needed are inadequate, the government may think of promoting awareness and training, and ensuring the availability of resources.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted teachers’ and students’ resources. According to the core assumption of CoR theory, individuals will persevere, retain, build, and safeguard things they value, and the pandemic has downcast those valuable resources. To achieve these resources, we, as an individual and part of the culture and society, must see this pandemic situation as not a problem but a challenge. Considering this as a challenge, the academic sector may derive motivation to pool resources and become more robust.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee, Amrita Vishwa Vidhyapeetham, Coimbatore, India. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

RS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abirami K. Radhika G. (2022). Analysis of student satisfaction on virtual learning platforms during COVID-19. Int. Conf. Innov. Comput. Commun.473, 563–574. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-2821-5_47

2

Abou Khalil V. Dabbagh N. Hanna E. (2021). Emergency online learning in low resource settings: Effective student engagement strategies. Educ. Sci.11:24. doi: 10.3390/educsci11010024

3

Agarwal S. Behera S. R. (2023). Geo-visualizing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ learning outcomes: evidence from grade 5 students. Environ. Plan B50, 2322–2325. doi: 10.1177/23998083231204125

4

Alsubaie M. A. (2022). Distance education and the social literacy of elementary school students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon8:e09811. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09811

5

Alturki U. Aldraiweesh A. (2022). Students’ perceptions of the actual use of mobile learning during COVID-19 pandemic in higher education. Sustain. For.14:1125. doi: 10.3390/su14031125

6

Asher S. (2021). COVID 19, distance learning and the digital divide: A case of higher education in the United States and Pakistan. Int. J. Multicult. Educ.23, 112–133. Available at: https://ijme-journal.org/index.php/ijme/article/view/2921

7

Baysal E. A. (2021). Teachers view on student misbehaviors during online course. Problems Educ. 21st Century79, 2538–7111. doi: 10.33225/pec/21.79.343

8

Bozkurt A. Karakaya K. Turk M. Karakaya O. Castellanos-Reyes D. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on education: A meta-narrative review. TechTrends66, 883–896. doi: 10.1007/s11528-022-00759-0

9

Braun V. Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health.11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

10

Byrne D. (2021). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Springer56, 1391–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

11

Chen H. Feng H. Liu Y. Wu S. Li H. Zhang G. et al . (2023). Anxiety, depression, insomnia, and PTSD among college students after optimizing the COVID 19 response in China. J. Affect. Disord.337, 50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.076

12

Cullinan J. Flannery D. Harold J. Lyons S. Palcic D. (2021). The disconnected: COVID 19 and disparities in access to quality broadband for higher education students. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ18:26. doi: 10.1186/s41239-021-00262-1

13

Feyisa H. L. (2020). The world economy at COVID-19 quarantine: Contemporary review. Int. J. Econom. Fin. Manag. Sci.8, 63–74. doi: 10.11648/j.ijefm.20200802.11

14

Garcia M. B. Revano T. F. Jr. (2022). “Pandemic, higher education, and a developing country: how teachers and students adapt to emergency remote education” in 2022 4th Asia Pacific information technology conference, Virtual Event (Thailand).

15

Gupta P. Gupta A. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on education sector. Ind. J. Appl. Res.10, 23–25. doi: 10.36106/ijar/7314325

16

Hegde V. Shilpa M. Pallavi M. S. (2022). Extracting attributes of students mental health, behaviour, attendance and performance in academics during COVID-19 pandemic using PCA technique. ICT Systems Sustain.321, 551–561. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-5987-4_56

17

Hobfoll S. E. Halbesleben J. Neveu J. P. Westman M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Ann. Rev. Org. Psych. Org. Behav.5, 103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

18

Hsieh C.-C. Li H.-C. Liang J.-K. (2024). Impacts of school online teaching demands and school online teaching resources on teachers’ emotional exhaustion during COVID-19: the mediating effect of family-work conflict. Contemp. Educ. Res. Quart.32, 1–25. doi: 10.53106/207380042024013201001

19

Hsieh C.-C. Liang J.-K. Li H.-C. (2022). Bi-directional work-family conflict of home-based teachers in Taiwan during COVID-19: application of job demands-resources model. J. Profess. Capital Commun.7, 273–289. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-07-2021-0045

20

Jackson K. Szombathelyi M. K. (2022). The influence of COVID-19 on sentiments of higher education students: prospects for the spread of distance learning. Econ. Soc.15, 143–158. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2022/15-3/8

21

Khan M. J. Ahmed J. (2021). Child education in the time of pandemic: Learning loss and dropout. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 127:106065. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106065

22

Kamal T. Illiyan A. (2021). School teachers' perception and challenges towards online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic in India: an econometric analysis. Asian Association Open Universities J.16, 311–325. doi: 10.1108/AAOUJ-10-2021-0122

23

Lee J. Lim H. Allen J. Choi G. (2021). Effects of learning attitudes and COVID-19 risk perception on poor academic performance among middle school students. Sustain. For.13:5541. doi: 10.3390/su13105541

24

Leo A. Holdsworth E. A. Wilcox K. C. Khan M. I. Ávila J. A. M. Tobin J. (2022). Gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-method study of teacher stress and work-life balance. Community Work Fam.25, 682–703. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2022.2124905

25

Lindasari S. W. Nuryani R. Sukaesih N. S. (2021). The impact of distance learning on students’ psychology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nursing Care4, 130–137. doi: 10.24198/jnc.v4i2.30815

26

Marchant E. Griffiths L. Crick T. Fry R. Hollinghurst J. James M. et al . (2022). COVID-19 mitigation measures in primary schools and association with infection and school staff well-being: an observational survey linked with routine data in Wales, UK. PLoS One17:e0264023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264023

27

Mithun H. Georg G. Raghu Rudraraju R. Prema N. (2020). Predicting school performance and early risk of failure from an intelligent tutoring system. Educ. Inf. Technol.25, 3995–4013. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10144-0

28

Nayak A. Dubey A. Pandey M. (2022). Work from home issues due to Covid-19 lockdown in Indian higher education sector and its impact on employee productivity. Inf. Technol. People36, 1939–1959. doi: 10.1108/ITP-01-2021-0043

29

Omang T. A. Angioha P. U. (2021). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the educational development of secondary school students. JINAV2, 25–32. doi: 10.35877/454RI.jinav261

30

Onyema E. M. Eucheria N. C. Obafemi F. A. Sen S. Atonye F. G. Sharma A. et al . (2020). Impact of coronavirus pandemic on education. J. Educ. Pract.11, 108–121. doi: 10.7176/JEP/11-13-12

31

Paik S. Samuel R. M. (2022). “Impact of pandemic on school education in India” in COVID-19 pandemic, public policy, and institutions in India: Issues of labour, income and human development. eds. DeI.ChattopadhyayS.NathanH. S. K.SarkarK. (London: Routledge).

32

Panakaje N. Rahiman H. U. Rabbani M. R. Kulal A. Pandavarakallu M. T. Irfana S. (2022). COVID-19 and its impact on the educational environment in India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.29, 27788–27804. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15306-2

33

Phungsoonthorn T. Charoensukmongkol P. (2022). How does mindfulness help university employees cope with emotional exhaustion during the COVID 19 crisis? Scandinavian. J. Psychol.63, 449–461. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12826

34

Pietro G. D. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 on student achievement: evidence from a recent meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev.39, 100530–938X. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100530

35

Pokhrel S. Chhetri R. (2021). A literature review on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future8, 133–141. doi: 10.1177/2347631120983481

36

Ponce R. G. Alonzo D. Llanita G. Polestico R. (2023). Development of online post-COVID intervention program for students: ensuring effective reintegration in the physical learning space. Int J Qual Methods22, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/16094069231152212

37

Poudel K. Subedi P. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on socioeconomic and mental health aspects in Nepal. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry66, 748–755. doi: 10.1177/0020764020942247

38

Qamar M. T. Ajmal M. Malik A. Ahmad M. J. Yasmeen J. (2023). Mobile learning determinants that influence Indian university students’ learning satisfaction during the COVID 19 pandemic. Int. J. Contin. Eng. Educ. Life-Long. 33, 245–254. doi: 10.1504/ijceell.2023.129212

39

Rani K. V. S. Prasad C. H. V. S. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on higher education. Dogo Rang Sang Res. J.12, 2347–7180.

40

Rathnayaka I. W. Khanam R. Rahman M. M. (2022). The economics of COVID-19: a systematic literature review. J. Econ. Stud.50, 49–72. doi: 10.1108/JES-05-2022-0257

41

Sangeeta K. Tandon U. (2021). Factors influencing adoption of online teaching by school teachers: A study during COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Affairs21:e2503.

42

Sarkar B. Islam N. Das P. Miraj A. Dakua M. Debnath M. et al . (2023). Digital learning and the lopsidedness of the education in government and private primary schools during the COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. E-Learning and Digital Media20, 473–497. doi: 10.1177/20427530221117327

43

Senniyappan M. Garadi S. Deol R. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on children: Indian perspective and concerns: are we sentient?Int. J. Med. Public Health11, 179–182. doi: 10.5530/ijmedph.2021.4.33

44

Serra G. Lo Scalzo L. Giuffre M. Ferrara P. Corsello G. (2021). Smartphone use and addiction during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: cohort study on 184 Italian children and adolescents. Ital. J. Pediatr.47:150. doi: 10.1186/s13052-021-01102-8

45

Sharaievska I. McAnirlin O. Browning M. H. E. M. Reigner N. (2022). “Messy transitions”: students’ perspectives on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education. High. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00878-2

46

She R. Wong K. Lin J. Yang X. (2021). How COVID-19 stress related to schooling and online learning affects adolescent depression and internet gaming disorder: testing Conservation of Resources theory with sex difference. J. Behav. Addict.10, 1036–1047. doi: 10.1556/2006.2021.00082

47

Shrestha N. Shad M. Y. Ulvi O. Khan M. H. Karamehic-Muratovic A. Nguyen U. D. T. et al . (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on globalization. One Health11, 100180–107714. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100180

48

Shukla M. Pandey R. Singh T. Riddleston L. Hutchinson T. Kumari V. et al . (2021). The effect of COVID-19 and related lockdown phases on young people’s worries and emotions novel data from India. Front. Public Health9:645183. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.645183

49

Singh A. K. Meena M. K. (2022). Challenges of virtual classroom during COVID-19 pandemic: an empirical analysis of Indian higher education. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ.11, 207–212. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v11i1.21712

50

Sumathi G. N. Elavarasi G. N. (2024). Study on the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and psychological distress: sense of coherence as a mediator. Emerging Business Trends Manag. Practices. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-17850-6_5

51

Tang K. H. D. (2023). Impacts of COVID-19 on primary, secondary and tertiary education: a comprehensive review and recommendations for educational practices. Educ. Res. Policy Prac.22, 23–61. doi: 10.1007/s10671-022-09319-y

52

Tsolou O. Babalis T. Tsoli K. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education: social exclusion and dropping out of school. Creat. Educ.12, 529–544. doi: 10.4236/ce.2021.123036

53

WAR (2019). World Air Quality Report (2019). World Health Organization, & World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.

54

World Health Organization . (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID 19) situation report 51. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10

55

Wu Y. C. Chen C. S. Chan Y. J. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19: an overview. J. Chin. Med. Assoc.83, 217–220. doi: 10.1097/jcma.0000000000000270

56

Yadav A. K. (2021). Impact of online teaching on students’ education and health in India during the pandemic of COVID-169. Coronaviruses2, 516–520. doi: 10.2174/2666796701999201005212801

57

Yu Y. Lau J. T. F. Lau M. M. C. (2023). Development and validation of the Conservation of Resources scale for COVID-19 in the Chinese adult general population. Curr. Psychol.42, 6447–6456. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02198-7

58

Zheng Y. Zheng S . (2022). A comparison of students’ learning behaviors and performance among pre, during and post COVID-19 pandemic. SIGITE '22: Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference on Information Technology Education, Chicago, IL, USA.

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, education, high school, conservation of resources theory, reflexive thematic analysis

Citation

Sulur Anbalagan R, Gudugunta Lakshmi S, Sowndaram CS and Arumugam B (2025) Probing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on government high school students, Nellore, India. Front. Educ. 10:1442878. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1442878

Received

03 June 2024

Accepted

07 April 2025

Published

09 May 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Matthias Ziegler, Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany

Reviewed by

Cucuk Wawan Budiyanto, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

Larisa Loredana Dragolea, 1 Decembrie 1918 University, Romania

Elena Zubiaurre, Alfonso X el Sabio University, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Sulur Anbalagan, Gudugunta Lakshmi, Sowndaram and Arumugam.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rajalakshmi Sulur Anbalagan, sa_rajalakshmi@cb.amrita.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.