- 1Department of Learning and Instructional Sciences, Faculty of Education, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

- 2The Unit of English Studies, The Max Stern Yezreel Valley College, Emek Yezreel, Jezreel Valley, Israel

Introduction: Given the predominant psycholinguistic approach to language education, little is known about the epistemic beliefs of language teachers and how they shape the enactment of reformed language curricula. These beliefs are mostly researched in science education but less in language education. To fill this gap, we investigated the epistemic beliefs of Arabic-speaking teachers of English in Israel and how they converge with or diverge from the epistemic underpinnings of the national English curriculum.

Methods: We collected data from 44 teachers primarily via personal and group interviews in 11 school settings. We also observed staff meetings and collected artifacts from teachers. We asked how teachers understand the notion of academic literacy, and how their understanding of literacy (mis)aligns with the epistemic orientation of the English curriculum in Israel. We used interpretative phenomenological analysis to uncover teachers’ implicit epistemic beliefs by probing into their interpretations of the curriculum’s teaching goals and learning principles.

Results: Thematic analysis revealed three major misalignments relating to the function of literacy in the lives of language learners, the features of literacy, and the fields of responsibility of teachers and learners. These misalignments were found even though teachers drew on the same terminology of the reformed curriculum when talking about their practice.

Conclusion: Findings indicate that teachers employ a different sense of literacy than intended in the curriculum. Theoretically, insights about teachers’ epistemic beliefs, which are mostly implicit, helped us explain the explicit pedagogical and instructional beliefs that are widely held by language teachers across language teaching contexts. Practically, the study suggests that policymakers, curriculum designers, and teacher educators need to be aware of the implicit epistemic beliefs of language teachers and the way these beliefs can shape how teachers enact language reforms.

1 Introduction

Consider the following excerpt from a group interview with Hani, who teaches English as a foreign language (EFL) at a public middle school and is required to implement Israel’s reformed English curriculum:

We must not give up the constituents of language (vocabulary and grammar) because if learners…want to become scientists or get a master’s degree or conduct research such as the one you’re doing, if they do not know how to write in English and if their language is not good, they will curse their teachers. And I think it’s important we save ourselves the curse by giving them the right thing so that when they grow up and need these things, they’ll say “We did learn all these things.” And this is our job, to cover all these skills in addition to all the new elements in the curriculum—for example, Bloom’s taxonomy for the questions we ask in class, such as lower-order thinking skills and higher-order thinking skills.

Like all teachers in our study, Hani draws a direct link between linguistic competence (vocabulary and grammar, or “how to write in English”) and academic practice (“to become a scientist,” “get a master’s degree,” and “conduct research”) while drawing on the terminology of the reformed curriculum (“Bloom’s taxonomy”). This link is evident in relatively recent literacy initiatives, such as the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2020). Referred to as academic literacy (Street and Leung, 2010), the language use foregrounded in these programs caters to knowledge-generation demands, where language learners should be prepared “to take their place in 21st-century society as literate generators, as well as consumers of knowledge” (Goldman and Scardamalia, 2013, p. 2). As such, academic literacy is conceptualized as having two intertwined dimensions: Content (reflected in linguistic resources) and argumentation processes (reflected in higher-order thinking skills; Goldman et al., 2016).

Although curricular reforms unpack both the content and thinking processes of the subject matter, research has shown that reforms frequently are only partially implemented to the point of being compromised (Bryan, 2012). Scholars discuss the inequitable access to high epistemic quality of what students come to know of the subject matter (Hudson, 2019) and the lack of deep learning in which the epistemic structure of the area of study should be made visible to learners (McPhail, 2021). Norris and Phillips (2003) have long called for a shift in focus from a derived sense of literacy that is “centered on the outcomes or products of inquiry” to a fundamental sense, which highlights engagement with “the fundamental processes of science, that is, on the ways in which knowledge is generated” (Weiss et al., 2022, p. 16).

To uncover which sense of literacy Hani is employing, we investigated how Arabic-speaking English teachers understand the notion of academic literacy underlying Israel’s reformed English curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2018) through the prism of their epistemic beliefs (Fives and Buehl, 2012). By employing interpretative phenomenological analysis (Smith et al., 2009), we explored teachers’ beliefs about knowledge of language and knowing a language. This investigation helped us determine where teachers’ understanding of their practice aligns or misaligns with the epistemic orientation underlying the teaching goals and learning principles of the curriculum. It also helped explain teachers’ instructional and pedagogical practices. Insights from this study can be relevant across EFL teaching contexts where the CEFR has recently been widely enacted.

This study attends to two gaps in the literature on language teachers’ epistemic beliefs. Despite the propagation of studies on language teachers’ beliefs, most of these studies focus on self-reported beliefs of teachers who are English native speakers teaching in English-as-a-second-language (ESL) contexts (Borg, 2015). This study foregrounds the epistemic beliefs of teachers who are non-native speakers of English teaching in EFL contexts. Furthermore, although teachers’ epistemic beliefs are recognized as central to the implementation of science curricular reforms (Barzilai and Chinn, 2018; Lammert et al., 2022), very few studies have focused on the epistemic beliefs of language teachers (e.g., Goldman, 2015) and how teachers socialize learners in reading scientific texts (Oliveira and Barnes, 2019).

1.1 Epistemic beliefs of language teachers: an undermined research construct

Although language teachers’ cognition has been acknowledged as a significant factor in language curriculum enactment (Borg, 2015), little emphasis has been put on teachers’ epistemic beliefs—that is, their beliefs about knowledge of a language and knowing a language (Fives and Buehl, 2012). This lack of emphasis can be attributed to the psycholinguistic approach to language acquisition that has long influenced the research and practice of curriculum design for more than half a century. At its basis, this approach considers language a mental faculty, the acquisition of which takes place in learners’ minds. Such a premise renders the process of language learning a universal enterprise that is conceived to be similar across language teaching contexts (Street and Leung, 2010). It is worth mentioning that this perspective on language learning and teaching does not fully encompass the diverse contexts of language teaching today.

This universal stance on language learning has been reflected in curriculum design that foregrounded pragmatic language use while backgrounding its epistemic underpinnings. Drawing on Schwab’s (1964) structure of the curriculum, the deep structure of curriculum design centered on the notion of communicative competence (Hymes, 1971) as the bedrock of language learning and teaching. This sociolinguistic theoretical framework for curriculum design foregrounded the communicative functions of linguistic resources, both academic and non-academic. Accordingly, the surface structure of curriculum design involved linguistic and discursive resources and their acceptable use. This linguistic functional focus has been reflected in the communicative language teaching approach that is composed of grammar, discourse, and pragmatic competencies (e.g., Celce-Mercia and Olshtain, 2014).

Despite its sociolinguistic roots, this functionally communicative focus in curriculum research and design seems to have foregrounded linguistic input and output (Swain, 2005) as a universal construct while backgrounding the social and cultural situatedness of academic language use. Such a language-based, universalist conceptualization of literacy is believed to have reduced the teaching of academic language use to the teaching of “language as structure and literacy as a set of generic skills and fixed genres” (Street and Leung, 2010, p. 291). This generic and fixed view of literacy has shaped research on teachers’ thinking in ways that emphasize the feasibility of the communicative teaching approach rather than what underlies the notion of literacy.

Specifically, research on teachers’ cognition has focused on a multitude of teachers’ self-reported explicit beliefs regarding factors that shape the enactment of communicative language teaching in their local contexts. Predominant research constructs have been teachers’ pedagogical and instructional beliefs regarding contextual imperatives, such as learners’ aptitude and motivation, parents’ expectations, and policy imperatives (for a comprehensive review, see Borg, 2015). Less attention has been given to teachers’ hidden beliefs about what does and does not constitute linguistic knowledge and the process of knowing a language. However, when approaching language acquisition from a sociocultural perspective, teachers’ epistemic beliefs take precedence. Therefore, the construct of epistemic beliefs constitutes the conceptual underpinning of this study.

1.2 The primary nature of epistemic beliefs

Epistemic beliefs have long been considered vital to teachers’ approach to educational reform (Stromso and Braten, 2011), the effective mediation of the structure of the discipline to learners (Marsh and Willis, 2007), the cultivation of learners’ epistemic beliefs (Hofer, 2010), and consequently, their academic achievements (Bråten et al., 2014). Teachers’ epistemic beliefs have been found to shape classroom processes by filtering information and experiences, framing problems, and guiding teachers’ actions (Fives and Buehl, 2012). These have been defined as primary beliefs in the sense that other beliefs (e.g., pedagogic) derive from them (Cross, 2009). For an educational reform to succeed, teachers need to share the view of the content and principles of teaching advocated by reform initiatives (National Research Council, 1996). When “teachers” beliefs are not in line with the philosophical underpinnings of the reform,’ reform initiatives can be compromised (Bryan, 2012, pp. 483–484).

Although the construct of epistemic beliefs is predominant in research on the cognition of science teachers, it is lacking in the field of language education given the predominant psycholinguistic approach. However, to account for the struggle of English learners to achieve competence in academic language use in ESL contexts, researchers initiated the new literacy studies framework (Cazden et al., 1996). Within this research framework, researchers rethought the notion of academic literacy by acknowledging the social and cultural underpinnings of academic language use. This sociocultural approach draws on Vygotsky’s (1978) conceptualization of language as a social construct first acquired in social interactions (at the interpsychological level) and later represented mentally in learners’ minds (at the intrapsychological level). It also draws on Halliday’s (2004) sociolinguistic framework of meaning-making in which competence in using a language involves not only linguistic resources and discursive rules but also an epistemological orientation toward the nature of knowledge and the role of language in the social lives of a given speech community.

Recent language curricular reforms (e.g., CEFR) highlight the epistemological orientation underlying academic language use. The fundamental sense of literacy (Weiss et al., 2022) and the epistemic structure of the subject matter (McPhail, 2021) are reflected in the stated teaching goals and learning principles of the curriculum. Literacy curricular reforms today have moved from the generic goal of learning to read toward the academic goal of reading to learn, emphasizing reading for meaning (Oliveira and Barnes, 2019). This philosophical shift highlights the academic function and thinking skills embedded in academic language use —namely, the evaluation of existing knowledge and the generation of new knowledge about the physical and social world learners inhabit. This epistemic orientation toward generating new, contentious knowledge is not a universal practice. It is socially and culturally situated (Street, 1995).

Cultural groups vary in their epistemological orientations concerning the nature of knowledge (Heath, 2004). Epistemological orientations span a continuum (Kuhn and Weinstock, 2002). A speech community can hold onto an epistemological orientation that values the individual’s right to investigate social and scientific phenomena. This value embeds an evaluativist epistemic cognition, wherein knowledge is constructed, tentative, evidence-based, and evaluated in context. This epistemology relies mostly on higher-order thinking skills, such as critical thinking (Forehand, 2010), and is based on the underpinnings of the constructivist theory of learning (Yang et al., 2008). Another speech community can hold onto an epistemological orientation that values the community’s obligation to preserve knowledge about the world. This value embeds an absolutist epistemic cognition, where knowledge is relatively fixed and unchangeable across contexts. This epistemology relies mostly on lower-order thinking skills, such as remembering facts and applying them in different situations (Forehand, 2010), and is based on the underpinnings of behaviorist theories of cognition (Yang et al., 2008).

These epistemological orientations are contended to underlie how language is used and taught across speech communities. Drawing on Triandis’ (2018) constructs of cultural tendencies, which are potentially dynamic and changeable, language teaching in individualist communities tends to nurture an evaluativist epistemological orientation whereas collectivist communities tend to foster an absolutist epistemological orientation (Heath, 2004; Scollon, 1999; Takahashi, 2021). As such, investigating English teachers’ epistemic beliefs is vital for the effective enactment of curricular reforms—namely, for fostering the fundamental sense of literacy (Norris and Phillips, 2003) where both the content and argumentation processes of academic language use are equally highlighted (Maggioni et al., 2015). This is especially relevant to EFL contexts where English is primarily taught for academic purposes.

1.3 Arabic-speaking teachers of English in Israel: a case of competing epistemological orientations

The convergence of the curriculum and Arabic-speaking teachers of English in Israel is intriguing and hence potentially informative, given the different epistemological orientations at play in the enactment stage. The reformed English curriculum in Israel, in both its earlier standard-based version (Ministry of Education, 2018) and more recent CEFR-aligned version (Ministry of Education, 2020), rests on the notion of academic literacy which advocates an evaluativist orientation to language use. Based on the understanding that English in Israel is the “second language of the academy” (Spolsky, 1998) and a gatekeeper of higher education (Inbar-Lourie, 2005), curriculum designers recognized the need for Israeli learners “to be able to use both spoken and written English (to) progress in their professional, business, or academic careers” (Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 7). To achieve this, the curriculum advocates the evaluation of existing knowledge and the creation of new knowledge by cultivating higher-order thinking skills in teaching English “at all levels and all domains (to) enhance learners understanding and critical thinking” [Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 8]. Reflected in the benchmarks of its teaching goals, the curriculum foregrounds the academic functions English can serve, such as sustaining evidence-based arguments. Specifically, learners are expected to:

interact for a wide variety of purposes, such as persuading, discussing, and group decision-making; independently find and integrate information from multiple sources for a specific purpose; design different means for collecting information, such as surveys and interviews, and report on the results and conclusions; and analyze and interpret literary texts using higher-order thinking skills [Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 62].

In accord with this epistemological standpoint, the benchmarks of the curriculum learning principles strive toward achieving mastery goals (Braten and Stromso, 2004) which necessitate learners’ personal involvement and active engagement in the learning process. The principle of “meaningful learning” is believed to enable students to “not only advance in the acquisition of language but also progress in overall knowledge (and) clarification of values” (Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 10). Thus, activities should “enable learners to be involved cognitively and affectively in the learning process (through) thought-provoking opportunities (to) promote effective language learning” [Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 10]. Cognitive and affective involvement in the learning process are core elements of the intrinsic motivation necessary for the acquisition of academic literacy (Braten and Stromso, 2004).

That said, Israeli Arabic-speaking teachers of English have arguably been exposed to several conflicting epistemological orientations, given their membership in different speech communities. Educated in a largely conservative system (Orland-Barak et al., 2013) that highlights rote learning (Amara, 2006), these teachers presumably have been socialized into an absolutist epistemic orientation toward knowledge and knowing. During their tertiary academic education, however, they most likely have been socialized into an evaluativist epistemic orientation, given the Western academic orientation of Israel’s higher education institutions (Troen, 1992). Add to this conflicting reality the fact that English teachers in Israel are exposed in language education programs to the communicative language teaching methodology, with its psycholinguistic approach toward language acquisition (Orland-Barak and Yinon, 2005). Its universal premises concerning how communicative competence can be acquired seem to background the evaluativist aspect of academic language use.

Given the largely conservative orientation of the Arab educational system, teachers can also be presumed to have been socialized into an educational system that emphasized performance goals (Braten and Stromso, 2004) which encourage surface learning and rely on extrinsic motivation. During their tertiary academic education, however, they most likely have been socialized into an academic orientation that values mastery goals as befits the evaluativist epistemic orientation of the Israeli academy.

To investigate how these conflicting epistemic beliefs might affect teachers’ enactment of the curriculum, we explored the following research questions.

(1) How do teachers understand the notion of academic literacy as reflected in the teaching goals and learning principles of the English curriculum in Israel?

(2) How does their understanding of literacy align or misalign with the epistemic orientation of the curriculum?

2 Methodology

2.1 Conceptual and analytic framework

This study used interpretative phenomenological analysis (Smith et al., 2009) to better understand the phenomenon of implementing a language curriculum reform from teachers’ perspective. This approach allowed us to probe experiences of the curriculum “as they are lived by an embodied socio-historical situated person” who inhabits a world that is “socially and historically contingent and contextually bounded” (Eatough and Smith, 2017, p. 195). Given its interpretative focus, this approach can uncover teachers’ epistemic beliefs that are mostly hidden from their awareness (Kagan, 1992). This can be useful on two grounds. First, teachers can become aware of the possibly competing epistemologies shaping their cognition and practice. Second, teachers can better understand how their explicit derivative beliefs (e.g., pedagogic) originate from their implicit primary beliefs (i.e., epistemic).

2.2 Research context and participants

This study was conducted in Arab schools in northern Israel where most of the Arab population resides. This demographic concentration features a web of social and cultural orientations, manifested in three major ethnic communities (Christian, Druze, and Muslim), that can offer a rich and informative context for exploring curriculum enactment.

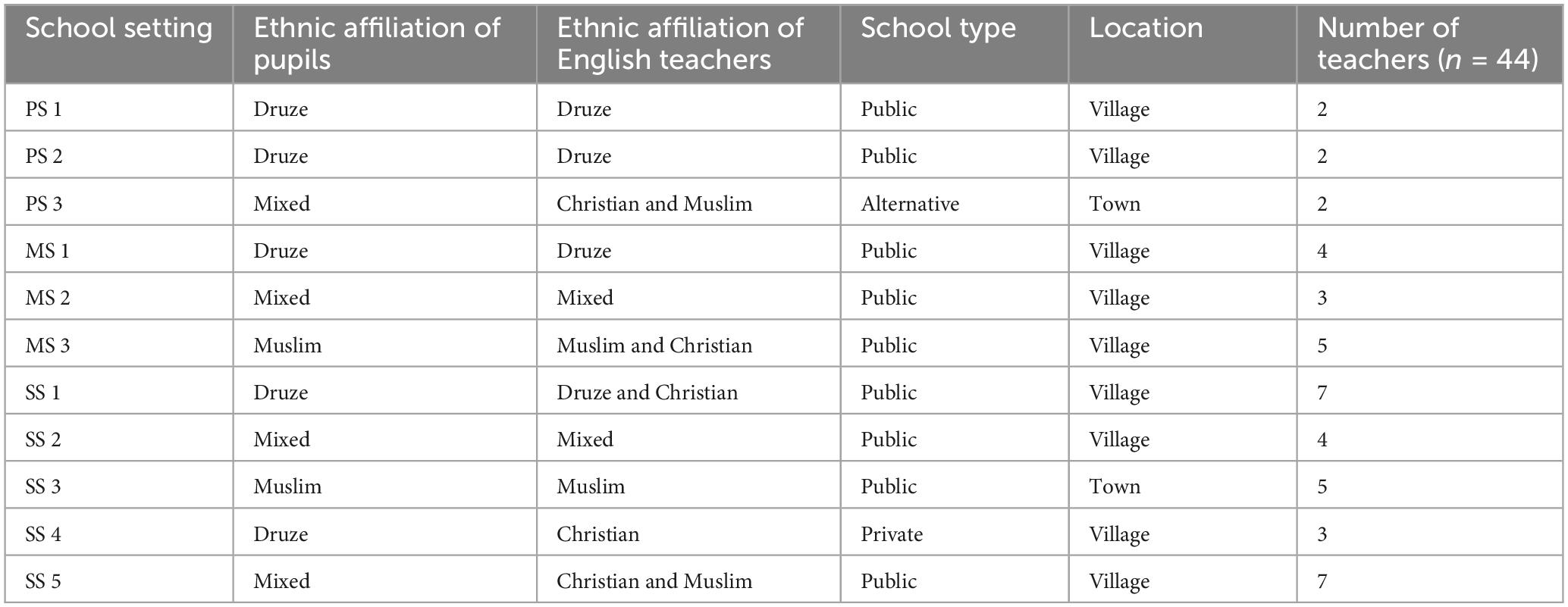

In this study, 44 teachers from 11 Arab schools were recruited using homogeneous purposive and maximum variation sampling methods (Patton, 1990). The former aims to examine the lived experience of a group in depth (Eatough and Smith, 2017). The latter aims to uncover shared patterns that cut across participant variation and derive significance from emerging out of heterogeneity. Specifically, we sought representation of the diverse ethnic composition of Arab schools (Christian, Druze, and Muslim) and school settings in which the English curriculum is implemented: primary schools (PS), middle schools (MS), secondary schools (SS), public, private, and alternative schools (see Table 1).

All teachers have the accreditation and experience required for enacting the national English curriculum. To begin with, all teachers have a bachelor’s degree in English language and literature. Five teachers have a master’s degree in TEFL. Two teachers have doctorates in English linguistics. All teachers have teaching certificates from accredited universities or colleges in Israel. Furthermore, teachers’ expertise in enacting the curriculum comes from their initial teacher preparation programs, ongoing professional development courses provided by the English Inspectorate of the Ministry of Education, and through ministry-approved textbooks that are based on the curriculum standards. Finally, all teachers have at least five years of seniority to make sure they are well immersed in the enactment of the curriculum.

Teachers were approached after receiving approval from the ethics committee of the Education Faculty at Haifa University, the chief science officer of the Ministry of Education, and school principals. During one of the English staff meetings at each school setting, we presented the goals of the study and invited the teachers to participate in it. The purpose of the study was explained orally and in writing. We assured them that their anonymity will be protected through pseudonyms and the removal of identifying details. For the second phase of the study (the personal interviews), we sent all teachers regular messages rather than WhatsApp messages, allowing them to decline discreetly without feeling any social pressure to participate. Before collecting data, we collected teachers’ signed consents.

2.3 Data collection and research tools

We used semi-structured interviews as the primary data collection tool because “the real-time interaction with the participant gives major flexibility for the researcher in facilitating the participant in exploring their lived experience” (Eatough and Smith, 2017, p. 208). Given the implicit nature of teachers’ epistemological beliefs (Kagan, 1992), they tend to develop in the absence of a formal process of theory construction, and teachers are rarely invited to make them explicit (Borg, 2015). In-depth interviews are contended to encourage teachers’ reflection on and disclosure of personal beliefs and epistemologies (Mangubhai et al., 2004).

We used two types of semi-structured interviews. First, we conducted group interviews (GI) at the outset of the study (44 English teachers from 11 schools). The duration of these interviews was 90 min. We aimed to assess the group’s level of meaning (Denzin, 1989) by providing teachers with a platform through which major themes in curriculum enactment could surface. This technique served the principle of triangulation by lending methodological rigor to the one-on-one interpretive nature of field interviews. Second, we conducted personal interviews (PI) with teachers who consented to participate in the second phase of the study (35 of the 44 teachers) to gain a deep understanding of their perspectives (Spradley, 1979). The duration of these interviews ranged between 45 and 90 min.

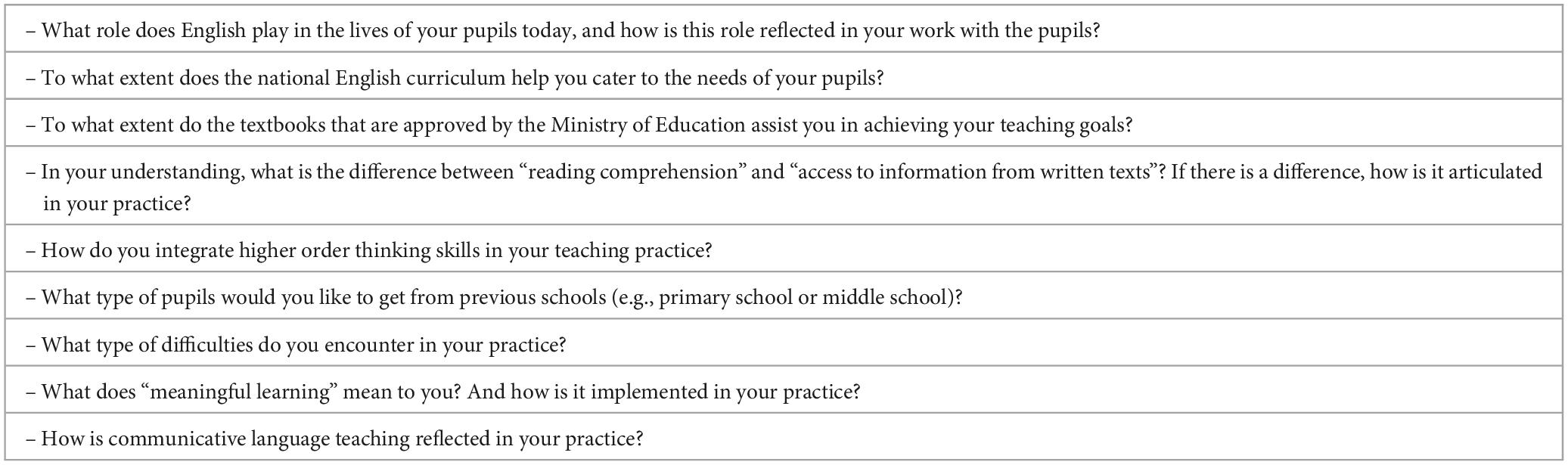

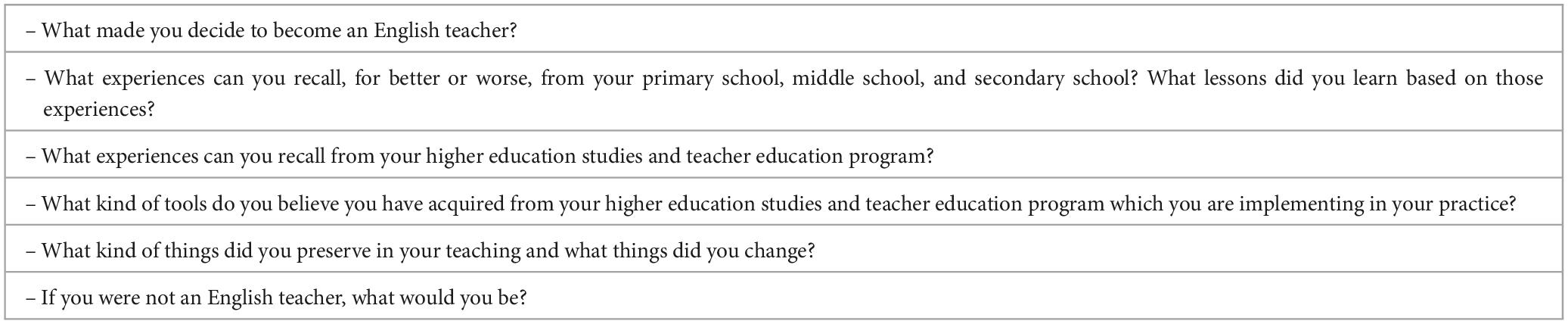

The GI protocol addressed teachers’ knowledge of the four commonplaces of curriculum making: knowledge of the subject matter, learners’ needs and attributes, teachers’ role and knowledge, and characteristics of the social milieu (Schwab, 1973) (see Table 2 for question prompts). Questions included concepts from the curriculum (e.g., meaningful learning) because clarification of concepts is essential to the effective process of curriculum enactment (Craig and Ross, 2008). Because teachers can translate terms idiosyncratically (Schwab, 1970), their interpretations could uncover their epistemic orientations regarding language learning and teaching. The PI protocol drew on Borg’s (2015) model of teachers’ sources of knowledge: teachers’ schooling experiences as language learners, professional education, teaching practice, and contextual factors in their practice (see Table 3 for question prompts). All group and personal interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Secondary data collection (Shkedi, 2005) involved observations of one weekly staff meeting at school (when not feasible, staff meeting protocols were collected) and teaching artifacts volunteered by teachers (e.g., worksheets). These two sources of data served the principle of triangulation (Patton, 1990) by reflecting teachers’ understanding of academic literacy through different manifestations.

2.4 Data analysis and interpretation

We conducted thematic analysis manually using open coding with four stages of analysis (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). In the first stage, we assigned codes to units of meaning in the data, then grouped codes into primary categories. By drawing links between primary categories, we reorganized them both horizontally (creating an array of categories) and vertically (creating subcategories). In the second stage, we grouped primary categories into thematic categories and finalized the labels of categories. In the third stage, we determined the core categories of analysis based on an organizing concept. These core categories assumed both descriptive and explanatory functions that significantly contributed to the general explanation of the researched phenomenon. Finally, we translated the core and thematic categories into theoretical concepts, arriving at theoretical descriptions and explanations of the researched phenomenon.

To ensure the validity of the data analysis, two secondary researchers not involved in the study were asked to analyze several interviews. This step ensured validity in the first three stages of analysis (coding and thematizing, mapping, and categorizing). In the GIs, head nodding and verbal consent among teachers were noted to capture recurring themes among teachers and across school settings. When patterns were detected, quotes were compiled, and illustrative excerpts were chosen.

3 Findings

3.1 The function of literacy: an act of empowerment

The first theme concerning how teachers understand academic literacy relates to the goal of literacy—i.e., the empowering function of displaying linguistic competence. Teachers offered three reasons why it is important to become literate in English from their past perspective as language learners and present perspective as teachers. One reason involved social empowerment. For example, Ihab echoed his colleagues regarding the status of English among pupils: “Knowing English is a matter of privilege and prestige with which pupils feel very proud” (SS5-GI). Hala said her linguistic competence distinguished her from others: “English is a foreign language. Not many people go and study English. People keep telling me that we English teachers are different, we stand out” (PS1-PI).

The second reason related to ideological empowerment. For example, Noor talked about how linguistic competence empowers women: “It is my weapon as a woman to study, earn academic degrees, not being a liability, being economically, socially, and politically independent” (SS5-GI). She said her linguistic competence in English served her well in the Israeli public sphere. When calling certain companies in Israel, she chose to speak in English. Compared to Hebrew, she felt she could express herself fluently in English without mistakes. Had she spoken in Hebrew, she might have felt she could fail, and it would be “possible that they would use this against me to pass any deal they wanted.” By conducting phone conversations in English, she felt “power over them as they couldn’t grasp that I am an Arab. Not only that, but they would also try really hard to make their service better so they avoid making scandals” (SS5-PI). Accordingly, she said her mission “is to prepare my pupils to go to the outside world feeling superior to others by knowing English” (SS5-PI).

The third reason involved financial empowerment. For example, Nisreen said that knowledge of English is eventually a means to an end: “Let’s be honest. It all comes down to earning high grades at the matriculation exam. They need this to be accepted later to prestigious majors at Israeli universities” (SS4-GI). To access profitable white-collar professions, students need to not only do well on the matriculation exam but also independently handle their academic studies. Amani said earning a high grade on the university admission exam can “exempt (one) from the mandatory English remedial courses at Israeli universities. I always tell them that this effort can save you a lot of money for these remedial courses” (SS3-GI).

3.2 The features of literacy: Competence at low cognitive demand tasks

The second theme that surfaced concerning how teachers understand academic literacy related to its features—i.e., the type of thinking skills embedded in linguistic competence. Teachers were definitive about the thinking skills that do and do not constitute knowledge of English.

3.2.1 Advocating lower-order thinking skills

Teachers advocated linguistic competence in tasks that have low cognitive demand. Secondary school teachers referred mostly to students’ ability to access academic articles at Israeli universities to accumulate and transmit knowledge. For instance, Ihab wanted to ensure pupils can handle “the bibliography lists they have to read” (SS5-GI), with the understanding that “most articles are written in English, even articles about Arabic language and literature” (Amani, SS3-GI). To access an academic article, teachers said learners need to understand what is written in English “on their own without resorting to expensive translation services” (Nawal, SS2-GI) so they can “find the main idea in an article and summarize it in their own words” (Moza, SS5-GI).

Teachers across all school levels talked about the two pillars of literacy—vocabulary and grammar—with a focus on rich lexical knowledge and accurate use of language:

Vocabulary is a key for approaching and understanding a text. I work…mostly on vocabulary…because…it was proved in research that if you know 97% of the words in the text, then you can deal with a text easily (Nisreen, SS4-GI).

Rawi also greatly emphasized vocabulary as a pillar of literacy by sharing long lists of vocabulary that he demands his pupils learn by heart every week (MS1, collected artifacts). He also emphasized the importance of applying linguistic rules by expressing how he feels “disappointed every time I see my pupils forgetting to put an “s” at the end of the present simple verb” (MS1-GI). Rana echoed her colleague Hala in saying they aim for and succeed at ensuring they “don’t have non-readers at school” (PS1-GI), although she acknowledged facing more difficulties in getting all her pupils to write without spelling mistakes.

Using Bloom’s terminology, the ability to know the meaning of words and apply grammar rules to access a text involves three lower-order thinking skills: decoding, understanding, and transferring linguistic knowledge from one context to another. Teachers’ focus on tasks with low cognitive demand was also found to be coupled with their explicit objection to the teaching of higher-order thinking skills.

3.2.2 Objecting to higher-order thinking skills

Teachers’ fervent belief in teaching grammar and vocabulary for accurate language use in tasks with low cognitive demand was coupled with their explicit objection to the integration of higher-order thinking skills in the reformed curriculum. Most of them regarded performance in tasks with high cognitive demand as technical and unnecessary. For example, Lama insisted that teaching these skills has “nothing to do with teaching English” (SS2-GI). Teachers also related to higher-order-thinking skills as unattainable and unteachable for most pupils. When discussing the old and reformed teaching goals of the English curriculum, Maram said that before the reformed curriculum:

The questions had to do with language and not intelligence. Now questions test for intelligence. There is a lot of inference in these questions. Who said English learners need to be smart? They need to know the language. In the past, pupils knew language; now they need to be smart to know how to answer in English (SS2-GI).

Maram clearly distinguished between knowing language and being smart. To her, the ability to infer information from a text cannot be taught; rather, it is a cognitive faculty that only smart pupils seem to possess naturally. Rana questioned the integration of higher-order-thinking skills in the primary school curriculum: “It takes big kids to implement big thinking skills. Primary pupils still get lost in an English text, so why overburden them with thinking at a high level like “read between the lines”?”(PS1-GI).

In objecting to adding higher-order thinking skills to the reformed curriculum, some teachers seemed to misconceive this element. In her attempt to prove that teaching higher-order thinking skills is a technical matter, Noor said that she taught these skills before their formal addition to the curriculum. According to her, solid linguistic knowledge and the ability to manipulate that knowledge are embedded in higher-order thinking skills:

Back then, when we had cloze and rewrite exercises, we had to think. We had to squeeze our minds. They would give you a sentence and at the end of the sentence they would put a word. This is not merely a grammar test. You must draw all your higher-order thinking abilities and know how to knead this sentence and come up with a grammatically correct new sentence (SS5-GI).

Noor seemed to have an idiosyncratic understanding of the notion of higher-order thinking skills. Drawing on Bloom’ taxonomy, rewriting a sentence with a new word does not require higher-order thinking skills. Noor seemed to mix higher-order thinking skills and lower-order thinking skills. Rewriting a sentence based on a new word involves three lower-order thinking skills: remembering the word and its grammatical position in the sentence, understanding its meaning in context, and applying that knowledge to a new context. Teachers’ interpretation of higher-order thinking skills seemed to omit abilities such as analyzing statements while inferring hidden meaning, evaluating others’ opinions, and creating new, original ideas (Forehand, 2010).

3.3 Fields of responsibility: prerequisite conditions to language learning

The third theme that surfaced in teachers’ discussions about their implementation of the English curriculum related to their beliefs about the language learning process and their related role.

3.3.1 Teachers’ responsibilities – linguistic modeling and emotional support

The first role teachers perceived to be part of their job description was linguistic role models for their pupils:

I am their role model…because sometimes they want to be like you. Sometimes they ask me how you got your English. I tell them to start to do what I did (as a language learner). I tell them, “You can be like me. You can be even better than me” (Nisreen, SS4-PI).

Nisreen said she views herself as a role model of linguistic competence for her pupils (“how you got your English”) and a mentor concerning how to achieve that competence (“start to do what I did”). Like other teachers, she cultivated her vocabulary and grammar by “doing dictation, copying words and sentences. We used to copy twice.”

The second role teachers perceived to be part of their job description was emotional supporters of their pupils upon displaying their linguistic abilities. In contrast to their former teachers, they talked about the importance of creating a positive classroom atmosphere where their pupils can make mistakes. Rana vividly recalled how her teacher’s negative feedback about her mistakes as a Hebrew learner harmed her self-confidence. Today, she is cautious not to do that with her pupils:

I was terrified to read…for fear of being yelled at. This thing taught me that I must provide my pupils with a sense of comfort and confidence to read. I truly believe that the personality of the teacher plays a role. Today, I give my pupils time to pronounce words. I give them room to make mistakes. Today, we don’t have non-readers at school (PS1-PI).

Rana prided herself on having no non-readers of English and attributed this fact to the safe classroom environment she cultivates. To her, this safe zone eliminates fear among pupils and encourages them to take risks and perform in front of others. Nonetheless, and despite their relentless efforts to care for their pupils’ emotional needs, teachers complained about their pupils’ lack of motivation to invest in learning the language.

3.3.2 Learners’ responsibilities – cognitive engagement and internal motivation

Most teachers said that for language learning to take place, pupils need to be motivated to learn English. Despite their linguistic and pedagogical efforts to facilitate their pupils’ linguistic performance, teachers lamented the fact that most pupils do not seem internally engaged in learning English, a situation they said hinders their teaching efforts:

In our school, most of the pupils do not give enough weight to English. They think English is a difficult language, and so they avoid it. Only very few stand out. Now, if pupils come to my class with this type of thinking, I don’t really know how much I can succeed with them. At least they should come without this kind of thinking (Samia, MS3-GI).

In Samia’s mind, the involvement of her pupils is perceived to be a prerequisite to fulfilling her role in teaching English, rather than a consequence of her teaching efforts. She seemed to presuppose that for her to teach English, her pupils need to come with the right kind of thinking; that is, English is important, and it is not a difficult language to learn. Once this mindset is present, Samia can proceed to teach.

Many teachers blamed parents who are not involved in their children’s linguistic and cognitive lives. Amani attributed the success of her good pupils to their family: “Home has a role in terms of exposure to the language and parents’ level of education” (SS3-GI). Sanaa attributed the failure of her pupils to the lack of “family gatherings where parents sit with their children and talk about things” (MS3-GI). Samia lamented the “emptiness in (pupils’) personalities. We open a topic for conversation, but pupils have nothing to say” (MS3-GI). Samia seemed to expect her pupils to have robust personalities and opinions in her English class, a responsibility perceived not to be included in her job description.

3.3.3 The learning process: linguistic competence precedes academic literacy

Teachers were found to believe that for pupils to be academically literate, they need a solid basis of linguistic knowledge. Doing meaningful things with language, such as expressing an opinion, only becomes possible once learners acquire this foundation. To Mariana, her pupils’ solid linguistic basis enables her to teach them how to be academically literate:

The minute there is a strong linguistic basis, I will be able to work on pupils’ ability to speak (by) having discussions and communicative lessons, (which) can work but only with good pupils, (because this is) very difficult with intermediate and weak classes (SS3-GI).

Her pupils will also know “how to write an academic essay,” such that “there is a thesis statement in the essay and there is a supporting argument.” Rana dismissed the teaching goal of social interaction in the Arab sector, given learners’ weak linguistic basis:

Take, for example, the domain of social interaction in the reformed curriculum. In Jewish schools where the level of English is very high and where there are teachers who are native speakers of the language, the interaction domain is great where children can speak the language. They have more exposure (PS1-GI).

To Rana, teachers who are native speakers of English provide high exposure to the language, and hence develop learners’ level of English, which, in turn, enables the implementation of the social interaction domain in the curriculum. However, the other way around is not imaginable—that is, involving pupils in interaction activities at whatever linguistic level to cultivate their linguistic competence.

4 Discussion

Given the scarcity of research on the epistemic beliefs of language teachers, the findings of this study add to the extant body of knowledge on language teachers’ beliefs. Specifically, it unravels some of the implicit epistemic beliefs of EFL teachers related to the social functions of linguistic knowledge, the linguistic features serving those functions, and the fields of responsibility embedded in the language learning process. Given their primary nature (Cross, 2009), teachers’ epistemic beliefs help shed light on the derivative, explicit beliefs held by EFL teachers worldwide, such as their pedagogic and didactic beliefs.

Pedagogically, teachers tend to adopt a form-focused approach in their practice where they put the focus on teaching vocabulary and grammar, sometimes at the expense of communicative language teaching (Ellis, 2001). Researchers attributed this tendency to external factors such as learners’ expectations, accountability pressures, classroom size, etc., (e.g., Borg, 2015). Based on the findings of this study, we offer an additional way that can help explain teachers’ explicit pedagogic beliefs concerning form-focused teaching. In teachers’ minds, linguistic knowledge of grammar and vocabulary serves an empowering function socially, ideologically, and financially. A derivative of this epistemic belief is the pedagogic practice of foregrounding linguistic content that enables the performance of tasks with low cognitive demand over argumentation processes that enable the generation of knowledge (Goldman and Scardamalia, 2013; Weiss et al., 2022). This pedagogical focus on the products of inquiry, rather than on its processes (Norris and Phillips, 2003) can be said to promote an absolutist, rather than an evaluativist, orientation in students (Kuhn and Weinstock, 2002), the latter of which underlies recent reform initiatives.

Didactically, teachers’ predominant methodology of knowledge replication (Lammert et al., 2022) can be said to derive from teachers’ epistemic beliefs concerning the nature of the language learning process. In teachers’ minds, the didactic focus on their practice should be put on linguistically and emotionally scaffolding the language learning process, at the center of which lies the linguistic content. They were found to believe that this kind of scaffolding allows for the acquisition of a linguistic base that can later be used for research in institutions of higher education and the workforce. A derivative of this belief is the didactic practice of foregrounding language practice in an emotionally and linguistically rich environment over the process of scaffolding cognitive engagement and inquiry-based teaching. This didactic focus on knowledge replication rather than knowledge generation can be said to promote performance goals over mastery goals (Braten and Stromso, 2004), the latter of which underlie the reformed language curriculum.

Uncovering the epistemic beliefs of teachers, such as the case of Arab teachers of English, sheds light on the epistemic beliefs of EFL teachers who come from culturally and linguistically different backgrounds and who are responsible for enacting a national reform that is underpinned by a different epistemological orientation. In what follows, we attempt to explain the epistemic beliefs of Arab teachers of English in Israel from at least three different perspectives – historical, political, and educational.

4.1 Form-focused literacy practices in the Arab speech community: a historical perspective

The historical forces that have shaped the social reality of the Arabic-speaking community at large can help explain why teachers approach literacy in terms of knowledge display in tasks with low cognitive demand. Although the Arab world has been transitioning from a collectivist to an individualistic society (Badran et al., 2020), the Arabic-speaking community tends to advocate literacy practices that foreground the linguistic form over the linguistic function (Hatim, 1997). What makes an argument persuasive are the linguistic forms used to describe an idea (Johnstone Koch, 1983), where “the elegant expression of an idea may be taken as evidence of its validity” (Bateson, 1967, p. 80). The form-based literacy practice prevalent in the Arabic-speaking community is similar to other collectivist communities worldwide where value is attached to traditional wisdom passed from one generation to the next (Heath, 2004; Scollon, 1999; Takahashi, 2021).

This form-based literacy practice also prevails in the Arabic-speaking community in Israel, given the collectivist nature of social relations (Abu Rahmoun et al., 2021) and its conservative school system (Orland-Barak et al., 2013) into which teachers have been inducted from an early age and in which they practice teaching. The Arabic-speaking community in Israel enjoys a status of relative educational autonomy (Al-Haj, 2012) in which a few teaching subjects deal with Arab history, language, and culture. For decades, textbooks for these subjects were adopted from neighboring Arab countries with form-based literacy practices (Amara, 2006). A recent study conducted on Arab teachers’ perceptions of religious education in Israel has shown that teachers advocate the transition of knowledge over discussions and reflective thinking (Saada, 2020). Despite recent reforms in Arabic-language education, literacy practices remain less investigated. Research is still narrowly focused on formal versus informal Arabic employed at home and school settings (Hassunah-Arafat et al., 2015), with less attention to argumentation processes.

4.2 Performance goals in the Arab community in Israel: a political perspective

The political reality of the Arab community in Israel can be said to have directed the community’s collective efforts toward performance goals rather than mastery goals of learning, largely for survival purposes (Lipman, 2009). Constituting a cultural and political minority, the Arab community in Israel is in a constant struggle between governmental control and socioeconomic mobility, trying to consolidate itself academically and economically (Agbaria, 2016). Many governmental positions in Israel are still inaccessible to Arab citizens due to national security reasons, forcing them to aspire to positions in teaching, medicine, law, and civil engineering. This reality has rendered Arab pupils “devoted to individualistic success and survival, under the persistent conditions of scarce governmental resources for improving Arab education and the limited opportunities for socioeconomic mobility” (Agbaria, 2016, p. 304).

Amid this political reality, the Arab community seems to direct its youth toward performance goals of learning from an early age. Based on the belief that success in school and higher education institutions can ensure children’s economic futures, parents and teachers seem to spur their children toward performance goals. These goals have narrowed the focus almost exclusively to achieving high grades on matriculation and university admission exams through the display of their acquired knowledge. The education field in the Arab sector in Israel has arguably redefined education as “job preparation, learning standardized skills and information, educational quality measurable by test scores, and teaching technical delivery which is centrally mandated and tested” (Lipman, 2009, p. 373).

Cultivating performance goals seems to come at the expense of cultivating mastery goals in the field of learning English. Given that in Israel, English is the second language of the academy (Spolsky, 1998) and the gatekeeper of higher education (Inbar-Lourie, 2005), the share of the English component in the matriculation and university admission exams is relatively large. To ensure acceptance to prestigious majors (such as medicine), pupils need to work very hard to score high on these exams. This might direct English teachers’ efforts toward the acquisition of linguistic competence (i.e., vocabulary and grammar). Drawing on the framework of meaning-making (Halliday, 2004), this pedagogical focus can explain teachers’ tendency to foreground the textual stratum of academic literacy over its intertextual and ideational strata. Teachers might feel ethically responsible for helping their pupils achieve the highest grades possible. And what element of academic language use is more apparent and easier to work with than the linguistic resources underlying academic literacy?

The most pronounced finding regarding this performance-oriented and survival-based mindset is how teachers described the empowering function of linguistic performance in their social lives, especially female teachers. They talked extensively about how knowledge of English empowers them economically as employed women in a patriarchal society; ideologically as a national minority in Israel; and individually as competent users of a language that most of their acquaintances view as difficult to learn. This empowering function of linguistic competence seems to shift the focus toward performance goals rather than mastery goals, because the former seems to be of more immediate relevance to their lives. In this regard, it is important to note that the “profitable white-collar jobs” teachers referred to when talking about financial empowerment through English literacy are jobs that require employees to have mastery over skills such as critical and creative thinking, curiosity, resilience, etc., (World Economic Forum, 2023). The question that remains to be answered is whether these skills are within the reach of English teachers who work in contexts where English learners grapple with these skills in their native language. Put differently, is it possible to develop these skills through learning English?

4.3 Idiosyncratic teaching theories among Arab teachers of English: an educational perspective

The culturally homogeneous reality of language teacher education programs in Israel can help explain Arab teachers’ idiosyncratic teaching theories oriented toward form-focused literacy practices and performance goals. Although acquired early in life through their “apprenticeship of observation’ (Lortie, 1975), the idiosyncratic teaching theories of Arab teachers of English in Israel seem to be unattended and hence, preserved in language teacher education programs. These programs have been conceptualized as culturally homogeneous in that they advocate Western-oriented cultural values to the exclusion of other values and orientations, such as those of Arab teachers. As a result, Arab prospective teachers seem to “pass through” these programs while putting their cultural orientations on hold until they begin teaching in their original context (Eilam, 2002). This means that their beliefs that were shaped during their school learning experience run the risk of being unacknowledged for their cultural diversity.

This situation is also relevant to language education programs due to the still predominant psycholinguistic approach to language learning and teaching in Israel. Pluricultural competence was acknowledged for the first time in the Ministry’s 2020 revised English curriculum as part and parcel of language education. This cognitive-based approach to language acquisition has created a reality in which the academic epistemic orientation has been assumed and hence, backgrounded in education programs. English language teaching has long been considered a “cultural island” in culturally diverse contexts, given the universality of the language acquisition process (Orland-Barak and Yinon, 2005). Backgrounding the epistemic orientation of academic literacy (i.e., the ideational stratum of language use) while foregrounding its linguistic features (i.e., the textual stratum) blurs epistemic differences between teachers and the curriculum. Unacknowledged, these differences often go unnoticed and unattended, resulting in teachers implementing the curriculum based on their early formed beliefs, which are largely idiosyncratic and not necessarily aligned with the epistemic underpinnings of the reform initiative.

The role of teachers’ idiosyncratic theories in shaping curriculum enactment is best reflected in research conducted on how teachers approach the teaching of reading. Despite recent reforms, teachers conceive the act of reading in terms of “learning to read” rather than “reading to learn” (Oliveira and Barnes, 2019). When teachers approach reading as a generic act, their pedagogical focus is naturally on the linguistic features of reading (e.g., morphology). However, when teachers approach reading as a specific act geared toward learning and generating new knowledge, their pedagogical focus shifts to the argumentation processes underlying reading (e.g., establishing a claim). Research has shown that whereas the former approach to reading aligns with performance goals, the latter approach aligns with mastery goals that preserve the complexity of the discipline (Braten and Stromso, 2004). It is also associated with students’ motivation for science reading comprehension and science achievement (Bråten et al., 2014).

Returning to Hani’s excerpt at the beginning of this paper, it can be argued that teachers in our study draw on the derived, rather than the fundamental, sense of literacy when they talk about their enactment of the curriculum. Although Hani used the curriculum’s terminology (e.g., higher-order-thinking skills) and goals (e.g., “become scientists”), he seemed to foreground a product-based sense of literacy whereas the curriculum advocates a process-based sense of literacy. Like other teachers, his understanding of the curriculum’s teaching goals and learning principles seemed to focus on the textual stratum of academic literacy and less on the interactional and ideational strata. In his daily practice, he described a focus on curriculum content (vocabulary and grammar) but not its underlying argumentation processes. As the findings revealed, he did not perceive these processes to be part of his job description. In his mind, he was solely responsible for the linguistic aspect of language learning, not its cognitive side. Drawing on his presuppositions about the language learning process, he expressed a belief that once learners’ linguistic competence is solid, the argumentation processes underlying academic language use can be feasibly acquired during higher education.

The practical implications of this study are many. First, at the stage of planning and writing a reformed curriculum, it is important to make the epistemic orientation of the language curriculum explicit. Specifically, the rationale of the reform should clearly define the notion of academic literacy in terms of its functions in the lives of learners, its features, and the fields of responsibility of teachers. Second, when designing teacher education programs, it is important to foreground the epistemic beliefs of teachers. This act can help uncover where misalignments between the epistemic orientation of the curriculum and that of teachers can occur. Third, when conducting continued professional development courses, it is recommended to do action research to see how teachers enact the curriculum and where the epistemological orientation of the curriculum clashes with the personal epistemology of learners. Insights from these localized studies can help delineate where misalignments occur and suggest ways that best cater to the educational needs of learners.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, we did not observe teachers enacting the curriculum in their classes. Although this aspect of curriculum enactment is important and called for (Borg, 2015), we narrowed the study to in-depth interviews with the teachers and observations of their staff meetings. In our attempt to look into the nature of teachers’ epistemic beliefs, we decided to focus on teachers’ talk about the enactment of the curriculum. Through their talk, we were able to detect and conceptualize (mis)alignments between their personal epistemology and that underlying the curriculum. We gave less attention to possible (mis)alignments between teachers’ talk and practice. Future research can fill this gap. Second, the study group was limited to Arab teachers teaching at Arab schools. This research focus allowed us to delve deeply into the nature of epistemic beliefs in one specific context. That said, it would be interesting to expand the study group to include Arab teachers teaching in Jewish schools as well as Jewish teachers teaching in both Jewish and Arab schools. Bearing in mind that the Jewish sector comprises a multitude of communities with different epistemic orientations, more insights would be available regarding the nature of the epistemic beliefs of language teachers enacting a national curriculum in their local contexts. These insights will help expand our knowledge base regarding the under-researched construct of language teachers’ epistemic beliefs in a multitude of contexts.

To conclude, investigating the epistemic beliefs of teachers served two functions. First, it helped to uncover what teachers mean when using the terminology of the curriculum they are responsible for enacting. Drawing on Craig and Ross’ (2008) notion of concept clarification in curriculum enactment, this study uncovered several misalignments between teachers’ conceptions of the reform and what curriculum designers originally intended. Second, investigating teachers’ epistemic beliefs helped to explain the explicit derivative beliefs of teachers, such as pedagogical and didactic beliefs, and the type of epistemologies (e.g., absolutist not evaluativist epistemology) and goals (e.g., performance not mastery goals) these beliefs serve. Curriculum designers and reform initiators, as well as teacher educators, need to be aware of teachers’ epistemic beliefs and the way these beliefs can shape the enactment of the curriculum in practice.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the IRB of the Education Faculty at Haifa University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RK-F: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. LO-B: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abu Rahmoun, N., Goldberg, T., and Orland-Barak, L. (2021). Teacher evaluation policy in Arab-Israeli schools through the lens of micropolitics: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 348-364. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2021.1947238

Agbaria, A. (2016). The new face of control: Arab education under neoliberal policy. In N. Rouhana (Ed.), Palestinian citizens: Practicalities of ethnic privilege (pp. 299-335). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Al-Haj, M. (2012). Education, empowerment, and control: The case of the Arabs in Israel. Albany, NY: Suny Press.

Amara, M. H. (2006). Teaching Arabic in Israel. In K. M. Wahba, Z. A. Taha, and L. England (Eds.), Proceedings of the Handbook for Arabic language teaching professionals in the 21st century (pp. 81-96). Routledge: England.

Badran, A., Baydoun, E., and Hillman, J. R. (Eds.). (2020). Higher education in the Arab world: Government and governance. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Barzilai, S., and Chinn, C. A. (2018). On the goals of epistemic education: Promoting apt epistemic performance. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 27(3), 353-389. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2017.1392968

Borg, S. (2015). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. Bloomsburry Academic: London.

Braten, I., and Stromso, H. I. (2004). Epistemological beliefs and implicit theories of intelligence as predictors of achievement goals. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29(4), 371–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2003.10.001

Bråten, I, Ferguson, LE, Strømsø, HI, Anmarkrud, Ø. (2014). Students working with multiple conflicting documents on a scientific issue: relations between epistemic cognition while reading and sourcing and argumentation in essays. Br J Educ Psychol. 84(Pt 1):58–85. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12005

Bryan, L. (2012). Research on science teachers’ beliefs. In B. J. Fraser, K. Tobin, and C. J. McRobbie (Eds.), Second international handbook of science education (Vol. 1, pp. 477–495). Berlin: Springer.

Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J., Kalantzis, M., Kress, G., Luke, A., Luke, C., Michaels, S., and Nakata, M. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. doi: 10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

Celce-Mercia, M., and Olshtain, E. (2014). Teaching language through discourse. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, and M. A. Snow (Eds.), Teaching English as a second language (pp. 424–437). Cengage Learning: Boston, MA.

Council of Europe (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg.

Craig, C., and Ross, V. (2008). Cultivating the image of teachers as curriculum makers. In F. M. Connelly, M. F. He, and J. Phillion (Eds.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 282-305). Sage: England.

Cross, D. (2009). Alignment, cohesion and change: Examining mathematics teachers’ belief structure and its influence on instructional practice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 12(5), 325-346. doi: 10.1007/s10857-009-9120-5

Eatough, V., and Smith, J. (2017). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In C. Willig and W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 193-211). Sage: England.

Eilam, B. (2002). “Passing through” a Western-democratic teacher education: The case of Israeli Arab teachers. Teachers College Records, 104(8), 1656-1701. doi: 10.1111/1467-9620.00216

Ellis, R. (2001). Introduction: Investigating form-focused instruction. Language Learning, 51, 1-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.2001.tb00013.x

Fives, H., and Buehl, M. M. (2012). Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us? In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, and T. Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook: Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors (Vol. 2, pp. 471-499). American Psychological Association: Washington, D.C.

Forehand, M. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology (pp. 41-47). CreateSpace: Scotts Valley, CA

Goldman, S. R. (2015). Reading and the web: Broadening the need for complex comprehension. In R. J. Spirom, M. DeSchryver, M. S. Hagerman, P. Morsink, and P. Thompson (Eds.), Reading at a crossroads? Disjunctures and continuities in current conceptions and practices (pp. 89-103). Routledge: England.

Goldman, S. R., Britt, M. A., Brown, W., Cribb, G., George, M., Greenleaf, C., Lee, C. D., Shanahan, C., and Project READI. (2016). Disciplinary literacies and learning to read for understanding: A conceptual framework for disciplinary literacy. Educational Psychologist, 51(2), 219-246. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1168741

Goldman, S. R., and Scardamalia, M. (2013). Managing, understanding, applying, and creating knowledge in the information age: Next-generation challenges and opportunities. Cognition and Instruction, 31(2), 255-269. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2013.773217

Hassunah-Arafat, S., Korat, O., and Aram, S. D. (2015). Mother-child interaction in the Arab family while reading a book and its contribution to children’s literacy in kindergarten and first grade. In G. Russo-Zimet, M. Ziv, and A. Masarwah-Srour (Eds.), Childhood in Arab society in Israel: Issues in education and research (pp. 1999-2034). Mofet Institute and Alkasimi College: Israel.

Hatim, B. (1997). Communication across cultures: Translation theory and contrastive text linguistics. University of Exeter Press: Exeter.?

Heath, S. B. (2004). What do bedtime story means: Narrative skills and home and school. In P. Smith and A. Pellegrini (Eds.), Psychology of education: Major themes (pp. 32-60). London: Routledge-Falmer.

Hofer, B. (2010). Epistemology, metacognition, and self-regulation: Musings on an emerging field. Metacognition and Learning, 5, 113-120. doi: 10.1007/s11409-009-9051-7

Hudson, B. (2019). Epistemic quality for equitable access to quality education in school mathematics. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(4), 437-456. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2019.1618917

Hymes, D. (1971). On communicative competence. In C. J. Brumfit and K. Johnson (Eds.), The communicative approach to language teaching (pp. 5-26). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inbar-Lourie, O. (2005). English language teaching in Israel: Challenging diversity. In G. Braine (Ed.), Teaching English to the world: History, curriculum and practice (pp. 81-92). Routledge: England.

Johnstone Koch, B. (1983). Presentation as proof: The language of Arabic rhetoric. Anthropological Linguistics, 25(1), 47-60.

Kuhn, D., and Weinstock, M. (2002). What is epistemological thinking and why does it matter? In B. Hofer and P. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: The psychological beliefs about knowledge and knowing (pp. 103-177). Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ.

Lammert, C, Hand, B, Suh, JK, and Fulmer, G. (2022). “It’s all in the moment”: a mixed-methods study of elementary science teacher adaptiveness following professional development on knowledge generation approaches. Discip Interdscip Sci Educ Res. 4(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s43031-022-00052-3

Lipman, P. (2009). Beyond accountability: Toward schools that create new people for a new way of life. In A. Darder, M. P. Baltodano, and R. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy (pp. 364-383). Routledge: England.

Maggioni, L., Fox, E., and Alexander, P. A. (2015). Beliefs about reading, text, and learning from text. In H. Fives and M. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 353-369). Routledge: England.

Mangubhai, F., Marland, P., Dashwood, A., and Son, J. B. (2004). Teaching a foreign language: One teacher’s practical theory. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(3), 291-311. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.02.001

Marsh, C. J., and Willis, M. (2007). Curriculum: Alternative approaches, ongoing issues. Pearson: London.

McPhail, G. (2021). The search for deep learning: A curriculum coherence model. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(4), 420-434. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2020.1748231

Ministry of Education. (2018). Revised English curriculum: Principles and standards for learning English as an international language for all grades. Jerusalem: Language Department.

National Research Council. (1996). National science education standards. National Academy Press: Washington, DC.

Norris, S. P., and Phillips, L. M. (2003). How literacy in its fundamental sense is central to scientific literacy. Science Education, 87(2), 224-240. doi: 10.1002/sce.10066

Oliveira, A. W., and Barnes, E. M. (2019). Elementary students’ socialization into science reading. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 25-37. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.02.007

Orland-Barak, L., Kheir-Farraj, R., and Becher, A. (2013). Mentoring in contexts of cultural and political friction: Moral dilemmas of mentors and their management in practice. Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 21(1), 76-95. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2013.784060

Orland-Barak, L., and Yinon, H. (2005). Sometimes a novice and sometimes an expert: Mentors’ professional expertise as revealed through their stories of critical incidents. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 31, 557–578. doi: 10.1080/03054980500355468

Saada, N. (2020). Understanding the religious controversy around democracy in Muslim-majority societies: An educational perspective. Citizenship Teaching and Learning, 15(1), 63-78. doi: 10.1386/ctl_00020_1

Schwab, J. (1964). Structure of the disciplines: Meanings and significances. In A. W. Ford and L. Pugno (Eds.), The structure of knowledge and the curriculum (pp. 1-30). Rand McNally: Chicago, IL.

Schwab, J. (1970). The practical: A language for curriculum. National Education Association, Center for the Study of Instruction: Washington, D.C.

Schwab, J. (1973). The practical 3: Translation into curriculum. The School Review, 81(4), 501-522. doi: 10.1086/443100

Scollon, S. (1999). Not to waste words or students: Confucian and Socratic discourse in the tertiary classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Culture in second language teaching and learning (pp. 13-27). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shkedi, A. (2005). Multiple case narratives: A qualitative approach to studying multiple populations. John Benjamin: Amsterdam.

Smith, J., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage: England.

Spolsky, B. (1998). The role of English as a language of maximum access in Israeli language practices and policies. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 33, 377-397.

Strauss, A. L., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage: England.

Street, B., and Leung, C. (2010). Sociolinguistics, language teaching and new literacy studies. In N. Hornberger and S. McKay (Eds.), Sociolinguistic and language education (pp. 290-316). Multilingual Matters: Bristol.

Stromso, H. I., and Braten, I. (2011). Personal epistemology in higher education: Teachers’ beliefs and the role of faculty training programs. In J. Brownlee, G. Schraw, and D. Berthelsen (Eds.), Personal epistemology and teacher education (pp. 54-67). Routledge: England.

Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 471-483). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ.

Takahashi, J. (2021). Answering vs. exploring: Contrastive responding styles of East-Asian students and native-English-speaking students in the American graduate classroom. Linguistics and Education, 64, 100958. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2021.100958

Troen, S. I. (1992). Higher education in Israel: An historical perspective. Higher Education, 23(1), 45-63. doi: 10.1007/BF00141144

Weiss, K. A., McDermott, M. A., and Hand, B. (2022). Characterizing immersive argument-based inquiry learning environments in school-based education: A systematic literature review. Studies in Science Education, 58(1), 15-47. doi: 10.1080/03057267.2021.1897931

Keywords: academic literacy, linguistic competence, epistemic beliefs, curriculum enactment, thinking skill levels

Citation: Kheir-Farraj R and Orland-Barak L (2025) Same words, different meanings: examining curriculum making from the perspective of language teachers’ epistemic beliefs. Front. Educ. 10:1478691. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1478691

Received: 10 August 2024; Accepted: 24 April 2025;

Published: 13 May 2025.

Edited by:

Brianna L. Kennedy, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaNélia Maria Pontes Amado, University of Algarve, Portugal

Brian Jon Birdsell, Hirosaki University, Japan

Copyright © 2025 Kheir-Farraj and Orland-Barak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roseanne Kheir-Farraj, cm9zZWFubmVrQHl2Yy5hYy5pbA==

Roseanne Kheir-Farraj

Roseanne Kheir-Farraj Lily Orland-Barak

Lily Orland-Barak