- Instituto IICSE, Universidad de Atacama, Copiapó, Chile

This study addresses the teaching of Social Sciences and History from a critical perspective, proposing the classroom as a laboratory for socio-historical analysis. Traditional education reproduces dominant narratives that reinforce social inequalities, exclude subaltern voices, and limit the development of critical thinking among students. The objective is to analyze how the classroom can become a space for resistance and critical reflection by incorporating historical thinking and critical pedagogy to foster the active construction of knowledge. A documentary methodology with a bibliographic design and critical-reflective approach was used. Through content analysis, relevant texts were selected and coded from various academic databases, prioritizing theoretical coherence with the study’s objective. Four key dimensions were identified: the reproduction of educational inequalities, critical thinking as a form of resistance, the transformation of historical narratives, and the teaching of history as a social practice. Additionally, a differentiated application of the approach by educational level (primary, secondary, and higher) was proposed, emphasizing the benefits of the historical method and interdisciplinarity in developing critical thinking. Theoretical evidence suggests that the classroom can be re-signified as a transformative space if inclusive, collaborative, and historically contextualized methodologies are promoted. Structural and institutional barriers must be overcome through critical educational policies and specific teacher training. Historical education, when critical and interdisciplinary, contributes to forming committed citizens capable of analyzing and transforming social reality from an ethical and emancipatory perspective.

1 Introduction

Pedagogical approaches have undergone significant transformation in the teaching of Social Sciences and History. The notion of conceiving the classroom as a laboratory for historical-social analysis (Santacana, 2005; Salazar-Jiménez et al., 2015) has gained traction among academics and educators who seek to transform the educational space into a dynamic environment for critical reflection and knowledge creation (Apple, 1997; Aisenberg and Alderoqui, 2007). In educational contexts marked by deep structural inequalities, traditional pedagogical dynamics often reinforce dominant narratives that reproduce existing relations of power and social inequality (Apple, 1997; Barton, 2008; Carretero and Van Alphen, 2014). Such educational practices, by legitimizing and validating primarily the cultural and symbolic capital of the elites, systematically relegate vulnerable popular sectors to subordinate positions, thereby deepening social and educational disparities (Bell, 2010).

In light of this scenario, it becomes essential to conceptualize the classroom not merely as a site for the transmission of dominant knowledge, but as an active and strategic space for cultural resistance and social transformation. From a critical sociological perspective, this transformation necessarily entails the integration of critical historical thinking and the critical sociology of education as key tools to question, deconstruct, and reconstruct hegemonic narratives (Wineburg, 2018). A central question thus arises: How can the classroom be transformed into an authentic space of resistance and critical reflection that fosters both the development of historical thinking and social transformation? Arising from this question, the objective of the present work is to analyze the classroom as a space for experimentation and reflection, where students do not merely learn about historical facts or social concepts, but engage in the critical reconstruction of such knowledge (Prats, 2011). The importance of teaching students to undertake research at all educational levels is emphasized, arguing that the development of these skills is essential for the formation of critical and active citizens.

It is contended that the historical method should not be reduced to the mere transmission of knowledge, but rather should serve as an approach that enables students to become active agents in their own learning (Domínguez, 2008; Prats and Santacana, 2011).

2 Theoretical perspectives

This study is grounded in four principal theoretical approaches: the critical sociology of education, critical historical thinking, critical theory, and the debate between competition and cooperation. From the perspective of critical sociology of education, Freire (1970), in his seminal work Pedagogy of the Oppressed, challenges the traditional or banking model of education, which positions students as passive recipients of knowledge. In contrast, Freire proposes a dialogical and problem-posing model that conceives education as a political act, wherein students learn to identify structures of oppression and acquire the tools for their transformation (Weber, [1922]2021). Complementing this, Bourdieu (1991) introduces the concepts of cultural capital and habitus to analyze how the educational system perpetuates structural inequalities. According to Bourdieu, the habitus, understood as a set of internalized dispositions, contributes effectively to the subtle yet persistent reproduction of structures of domination within educational contexts. The articulation between Freire and Bourdieu underscores the importance of a critical praxis capable of challenging such dispositions through reflective thought and transformative actions.

With respect to historical thinking, its role is emphasized as crucial in the formation of engaged and reflective citizens capable of questioning existing power structures (VanSledright, 2002; Gibbs and Coffey, 2004). In the contemporary context—characterized by a constant proliferation of information and ideological reinterpretations of the past (White, 1973; Stearns, 1998; Carretero et al., 2002)—it becomes essential to move beyond a teaching model centered exclusively on memorization and to promote a critical understanding of historical events (Parker and Donnelly, 2014), as well as to interrogate power structures (Foucault, 1975). Studies from Anglo-Saxon (Barton, 2008), Spanish (Santisteban et al., 2010; Prats, 2011; Prats and Santacana, 2011), and Latin American contexts (Muñoz, 2005; Vásquez, 2014; Salazar-Jiménez et al., 2015; Muñoz, 2022) have demonstrated that integrating disciplinary knowledge with socio-critical approaches not only enables a better understanding of the social environment (Cárdenas et al., 1991; Almansa, 2018; Carretero et al., 2002; Carretero and Voss, 2004), but also contributes to the formation of subjects capable of actively intervening in social reality in the face of inequalities and injustices (Aisenberg and Alderoqui, 2007).

Wineburg (2001) stresses that historical thinking is not a natural process, but a skill that must be deliberately cultivated. It entails analyzing historical sources through a critical lens, questioning inherent biases, and reconstructing narratives that incorporate marginalized voices. Peter Seixas (2000) complements this perspective by emphasizing the capacity of historical thinking to connect the past with present-day issues, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of contemporary structures. In this regard, critical reflection on the past becomes a transformative act, allowing for an understanding of the historical roots of the structural inequalities that critical sociology denounces (Santisteban Fernández, 2017).

From the standpoint of critical theory, Adorno and Horkheimer (1944) argue that education must question structures of domination, thereby promoting social emancipation and the development of autonomous and reflective individuals. This implies that the classroom should not only serve as a space for critiquing dominant narratives, but also as a participatory environment of dialogue, where students and teachers co-construct knowledge oriented toward social transformation.

Regarding the competition–cooperation debate, it is noted that competition has historically been promoted by dominant ideologies that justify inequality through theories such as social Darwinism, which inappropriately applies evolutionary principles to social contexts (Carr, 1966; Holmes, 1994; Tort, 1996; Blot, 2007). In contrast to this vision, Durkheim (1897), Kropotkin (1906), and Morin (2017) have shown that cooperation promotes social cohesion, integration, and solidarity, which are essential to avoid social anomie.

As a branch of this philosophical tradition, cooperative pedagogy has a broad and longstanding history. While it cannot be fully covered here, several of its key figures may be highlighted, including Célestin and Élise Freinet (1964a, b), Francisco Ferrer (Morzadec, 2024), Paulo Freire (Dubigeon and Pereira, 2024; Ocampo López, 2008), and from the field of neuroscience, Cyrulnik (2023, 2025). Ongoing theoretical-practical research in this field continues to inform teacher training effectively (Casanova et al., 2024). Despite such evidence, erroneous collective representations persist. The diagnostic test developed by Kreidler (1984) —another key contributor—can be used to identify and deconstruct these representations.

Based on the foregoing, it is justified to transform the classroom into a laboratory of historical and social analysis that enables students and teachers to engage critically with historical narratives and contemporary social dynamics (Carretero et al., 2013). This transformation is structured as a collective pedagogical process comprising four key stages: teacher training in cooperative pedagogy, the development of cooperative skills in students, training in critical investigation of family collective memory, and finally, the elaboration of group-level comparative syntheses (Domínguez, 2008). This project not only fosters intergenerational and social cohesion, but also strengthens students’ socio-historical awareness and democratic capabilities, thereby constituting a pedagogical praxis aligned with critical theory (Chaux et al., 2004; Donovan and Brasford, 2005) and the emancipatory pedagogy proposed by Freire.

3 Method

This study adopts a documentary methodology, framed within a bibliographic design and guided by a critical-reflective approach. Its purpose is to analyze the relevance of considering the classroom as a laboratory for historical-social analysis, understood as a pedagogical approach to the study of the past and society. Following Gómez et al. (2014), the bibliographic review allows for the identification and examination of the most significant theoretical contributions related to the subject of study, thereby facilitating an effective engagement with the extensive body of specialized literature. Consequently, the selected methodology required advanced skills in the search, selection, critical review, and analytical synthesis of relevant academic documents.

The corpus was selected through non-probabilistic sampling based on convenience and the expert judgment of the researcher, in accordance with the guidelines proposed by Muñoz (2013) and Gómez et al. (2014). The databases consulted included ERIC, Education Database, EBSCO, Scopus, and Google Scholar. To retrieve pertinent literature, a search equation was constructed using Boolean operators and the following key descriptors: (“classroom as laboratory” OR “aula como laboratorio”) AND (“historical-social analysis” OR “análisis histórico-social”) AND (“critical pedagogy” OR “pedagogía crítica”) AND (“teaching of history and society” OR “enseñanza de la historia y la sociedad”). This search strategy enabled a more accurate retrieval of relevant documents.

Moreover, explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to ensure the methodological rigor and transparency of the process. The inclusion criteria considered were: (a) publications in indexed academic journals from 2005 to 2024; (b) studies focused on critical pedagogical approaches to the teaching of history or social sciences; and (c) texts available in English or Spanish with full access to content. The exclusion criteria were: (a) studies with a strictly quantitative focus and lacking relevant theoretical engagement; (b) opinion pieces without empirical or methodological grounding; and (c) duplicate documents across databases.

The methodological development of this critical review followed the stages proposed by Gómez et al. (2014): (a) definition of the research problem; (b) information retrieval; (c) organization of the collected data; and (d) analysis of the information. To generate specific knowledge regarding the object of study, content analysis was employed as the primary interpretative technique, based on the framework developed by Andréu (2002), which focuses on the systematic examination of written texts.

This analysis was operationalized following the methodological sequence described by Fernández (2002), which includes: (a) identification of analysis topics based on constructs previously defined by the researchers; (b) data collection using the selected descriptors and search equation applied to the chosen databases; (c) development of analytical categories and a coding scheme aligned with the objectives of the study; (d) application of the coding scheme to a preliminary sample of the collected material; (e) complete coding of the corpus using the approved scheme; and (f) evaluation of the consistency of the procedure by verifying the internal coherence of the processed information.

4 Structural inequality and educational resistance

A primary category of analysis is the impact of cultural capital and critical thinking within educational dynamics. According to Bourdieu and Passeron (1977), schools function as mechanisms of social reproduction by endorsing cultural capital that benefits dominant classes. This capital manifests through linguistic codes, cultural practices, and values reflecting the elites’ habitus. Conversely, working-class students, lacking these symbolic resources, face greater challenges integrating successfully into the educational system (Geertz, 1983). This mechanism positions schools as sites where social inequalities are perpetuated under the guise of meritocracy (Gramsci, 1975; McLaren, 1984; Giroux, 1990).

However, the relationship between education and inequality cannot be reduced to a unidirectional logic (Geertz, 1983). Critical sociology reveals that educational structures, while reproductive, can also serve as transformative spaces through educational praxis and inclusive pedagogies (Fernández Palomares, 2003).

From the perspective of Freire (1970) and Giroux (1983), critical thinking is essential to subvert these dynamics. Freire argues that dialogue and praxis are crucial instruments for raising the consciousness of the oppressed, enabling them to identify power structures shaping their realities. Giroux (1983) expands on this by positioning schools as spaces of cultural resistance, where students can cultivate critical awareness, questioning and transforming their environments.

In this context, Giddens (1991) highlights that education not only reproduces inequalities but is also constantly renegotiated, allowing social dynamics to create new meanings and opportunities for change. This dialectical approach emphasizes that educational agents—teachers, students, and communities—can actively confront structural pressures.

4.1 Social inequalities and educational reproduction

The perpetuation of inequalities in education is intrinsically connected to its classifying function (Guerrero-Romera et al., 2022). According to Bernstein (1971), the linguistic structures and communicative codes prevalent in educational institutions favor those who share the habitus of higher social classes, relegating others to marginalized positions. For example, in urban schools, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds encounter linguistic barriers that impede effective classroom participation. Activities and assessments designed according to dominant linguistic codes perpetuate student exclusion. This symbolic exclusion is materialized through the hidden curriculum, legitimizing values and cultural practices inaccessible to all students (Gramsci, 1975; Guha, [1982], 2002).

4.2 Critical thinking as educational resistance

Critical thinking not only denounces inequalities but also facilitates the deconstruction of dominant narratives legitimizing oppressive structures (Hernández Cardona, 2002; Maggioni et al., 2009). This approach involves:

• Questioning established norms: recognizing how power relations shape school practices (Fernández Palomares, 2003).

• Fostering dialogue: creating participatory spaces where students reflect upon equity and human rights (Freire, 1970).

• Transforming pedagogical practices: adopting methods emphasizing collaboration and challenging traditional hierarchies (Giroux, 1983).

An illustrative example would involve a school project where students engage in debates on social justice and human rights. Through critical dialogue, students would identify discriminatory practices in their school environment and propose solutions to promote a more inclusive setting.

Freire (1970) defines the classroom as a space where pedagogical praxis can become a political act. Through authentic dialogue, teachers and students co-construct knowledge, generating transformative pedagogy that challenges authoritarianism and fosters emancipation. This approach, reinforced by Giroux (1983), positions schools as environments for building critical citizenship and promoting democratic values.

4.3 Practical barriers and strategies for overcoming them

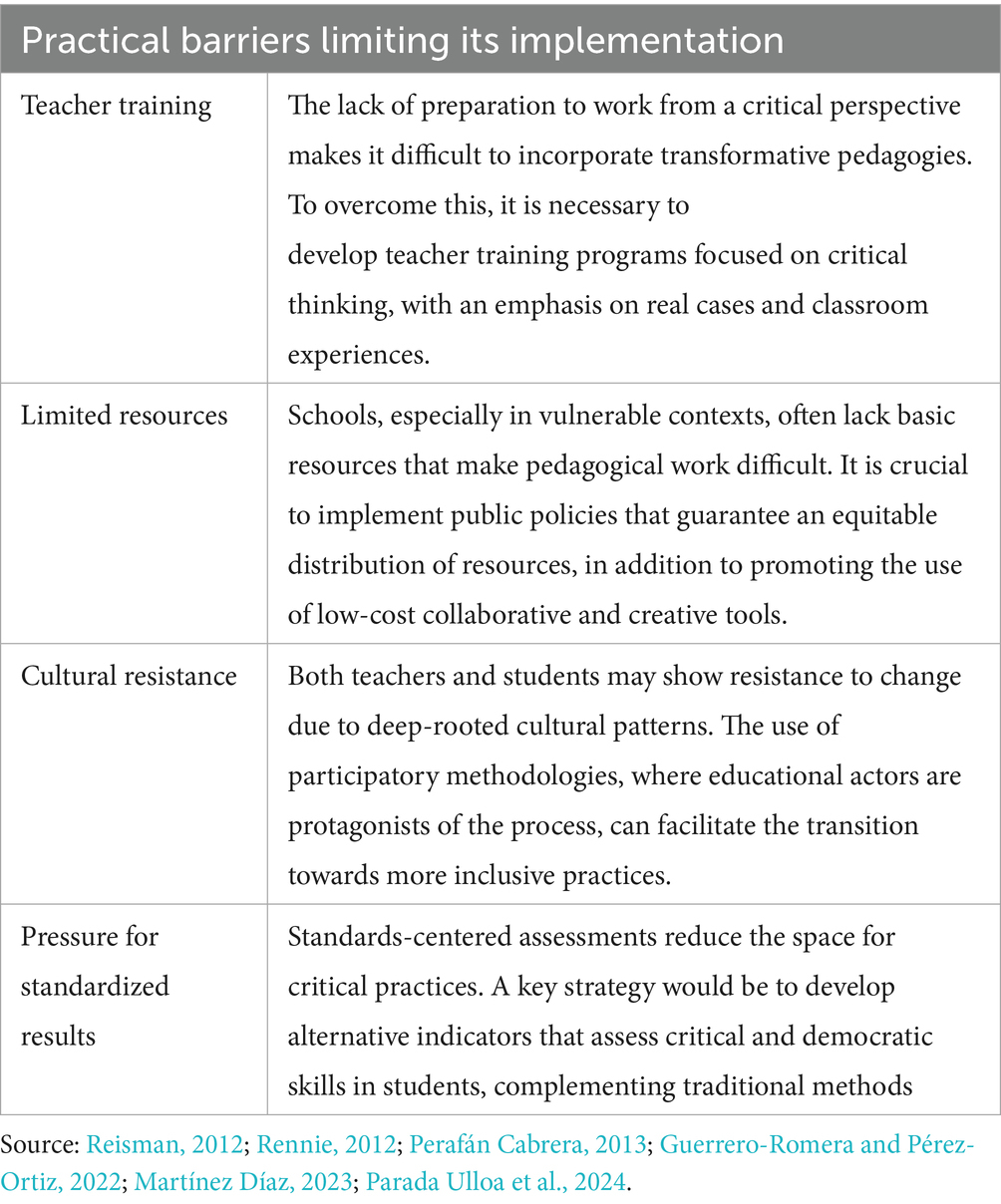

Although the proposals discussed previously possess considerable theoretical value, educators encounter practical barriers limiting their implementation:

5 Historical narratives and their transformation

The transformation of traditional historical narratives towards more inclusive and critical approaches constitutes a fundamental challenge in contemporary teaching. From a sociological perspective, questioning dominant narratives and reconstructing historical perspectives are essential tools for understanding the power structures that shape collective memory (Pereyra, 1995) and, at the same time, for constructing stories that integrate the diversity of social experiences (Santacana, 2005; Parts, 2011).

In this sense, the category of analysis around the questioning of dominant narratives has been constructed from a homogeneous perspective that reflects the interests of the dominant elites (Gramsci, 1975; Smith and Breakstone, 2015). As Wineburg (2001) points out, historical thinking requires hallenging simplistic and linear views that present facts as immutable (White, 1973). Deconstructing dominant narratives allows us to see how the voices of marginalized groups have been excluded and how certain historical interpretations have served to perpetuate social inequalities.

From a critical perspective, Fernández Palomares (2003) highlights that teaching history is not a neutral act, but a social practice deeply rooted in the ideological context of each society (Bloch, 1952; Carr, 1966; Braudel, 1989; Burke, 2003). Educational sociology has the task of questioning how curricular content and teaching methodologies reflect power structures, legitimizing certain discourses and excluding others.

5.1 Reconstruction of historical perspectives

Critical analysis of historical narratives is an essential step in reconstructing alternative perspectives. Seixas (2000) argues that teaching history involves not only transmitting knowledge, but also equipping students with tools to critically interpret predominant narratives (Fallace and Neem, 2005). This historical reconstruction seeks to incorporate the experiences of traditionally silenced groups, such as indigenous communities, women, and the working classes, challenging the hegemonic vision that has privileged the perspectives of the dominant (Duby and Guy, 1996; Le Goff, 2005). For example, the inclusion of primary sources that reflect the experiences of subaltern actors allows for opening up dialogue on the diversity of historical interpretations, promoting a richer understanding and complexity of the past (Wineburg, 2001). Furthermore, as Giddens (1991) indicates, this plurality of voices not only broadens the cultural horizon, but also fosters critical thinking that is essential for the formation of active citizens in democratic societies.

5.2 Inclusive and critical teaching

The reconstruction of historical narratives has a direct impact on inclusive teaching. Wineburg (2001) argues that historical thinking is an unnatural act, as it demands stepping outside one’s own preconceptions to understand how individuals in the past experienced their reality. From this perspective, inclusive teaching must foster historical empathy, understood as the capacity to comprehend the actions and decisions of individuals and groups within their specific historical contexts.

Fernández Palomares (2003) emphasizes that classrooms should serve as spaces where students encounter open-ended questions, critically reflect upon power relations (Foucault, 1975), and develop their own critical understanding of the past (Hernández Cardona, 2002). For instance, in a teaching unit on colonization, students might conduct research from multiple perspectives, incorporating voices of indigenous peoples as well as colonizers. Such inquiry promotes a profound understanding of historical events, while also cultivating students’ critical thinking and historical empathy skills.

This approach not only strengthens students’ cognitive abilities but also equips them to question the unilateral narratives prevalent in public and political discourses.

5.3 Practical limitations and strategies to overcome them

Despite the transformative potential of these proposals, educators face significant practical barriers when attempting their implementation:

• Institutional and Cultural Resistance: Changing pedagogical practices can generate resistance among both teachers and students, due to institutional inertia or deeply rooted cultural patterns. Overcoming this challenge requires cultivating a school culture that values pedagogical innovation and promoting educational leadership that supports these initiatives.

• Limited Interdisciplinary Approaches: History teaching often remains isolated from other disciplines, limiting its ability to address complex contemporary problems. Integrating interdisciplinary approaches, such as connecting history, sociology, geography, literature, and political science, enriches learning and fosters transferable skills (Trigwell et al., 2005). For example, an interdisciplinary project involving departments of history, literature, and political science would allow students to analyze the Industrial Revolution from multiple perspectives. This interdisciplinary approach not only enhances their comprehension of historical events but also provides tools to apply critical thinking to contemporary issues.

To overcome these limitations, it is essential to integrate historical thinking with other fields of knowledge, enabling students to critically address contemporary phenomena. Utilizing digital tools, such as multimedia archives and interactive simulations, facilitates access to diverse historical sources and promotes active learning (Sáez et al., 2016; Palacios, 2020). Furthermore, designing assessments that value critical and analytical skills, such as creating alternative historical narratives, can complement traditional methods and transform history education into an effective instrument for inclusion and social change.

Adorno and Horkheimer (1944) highlight how institutionalized educational systems may reproduce domination by legitimizing values and practices reinforcing the status quo (Plá, 2008). Nevertheless, classrooms can become spaces of resistance to these dynamics, enabling students to critically examine the power structures shaping their realities (Stearns, 1998; Seixas, 2000).

For example, following the insights of Adorno and Horkheimer (1944), Stearns (1998), and Seixas (2000), social science students can critically analyze their community’s history, identifying how political and economic decisions have impacted various social groups. This analysis empowers students to challenge local power structures and propose solutions to promote equity within their environment.

Freire (1970) argues that questioning power structures constitutes a fundamental act of liberation. His Pedagogy of the Oppressed emphasizes the necessity of authentic dialogue between teachers and students, positioning both as active participants in knowledge construction. Giroux (1988) extends this idea, advocating for the classroom as a democratic public sphere, where dominant narratives perpetuating inequalities are critically examined and deconstructed. Giroux asserts that critical education not only interrogates injustice but also equips students with tools to imagine and construct a more equitable society.

5.4 Promoting social justice

The classroom plays a central role in promoting social justice, understood as actively pursuing equity and redistributing power and resources within society. Education must transcend mere content transmission and become a political act through which students become aware of their oppressive realities and act toward transforming them (Trigueros-Cano et al., 2021). Methodologically, project-based learning on local and global problems fosters an active understanding of social justice. For instance, conducting a research project on local water contamination enables students to investigate underlying causes and propose actions to improve water quality, thereby promoting environmental justice. Freire (1970) describes this process as “conscientization,” whereby students recognize their roles within social dynamics and learn to intervene effectively to promote justice.

5.5 Creating committed citizens

The classroom also significantly contributes to forming committed citizens capable of actively participating in public life and advocating for a democratic and just society. Giroux (1990) argues that critical education should foster a sense of agency among students, encouraging them to assume an active role in constructing a shared future (Gómez and Miralles, 2015).

Within this framework, the critical theory articulated by Adorno and Horkheimer (1944) warns of the dangers inherent in passive citizenship shaped by consumerism and mass culture dynamics. To counteract these tendencies, classrooms should cultivate critical thinking, historical empathy, and ethical commitment, all of which are crucial for effective civic participation. A practical example includes educational projects engaging students in addressing local issues, applying knowledge to tackle matters such as inequality, environmental problems, or human rights (Ariès and Duby, 1987-1989). This approach enhances student learning and positions them as active agents of social change within their communities.

5.6 Practical limitations and strategies to overcome them

Standardized assessments often constrain educators’ ability to prioritize critical pedagogical practices. To address this limitation, advocating for alternative indicators capable of measuring skills such as historical thinking, empathy, and civic engagement is essential (Trigueros-Cano et al., 2022). For example, educational projects engaging students in addressing local problems can be designed. These could include community analysis workshops, interdisciplinary projects addressing economic inequalities, or spaces fostering democratic debate in the classroom (Álvarez et al., 2021). This approach enriches learning and positions students as effective change agents in their communities (Table 1).

6 The classroom as a space for the construction of historical knowledge

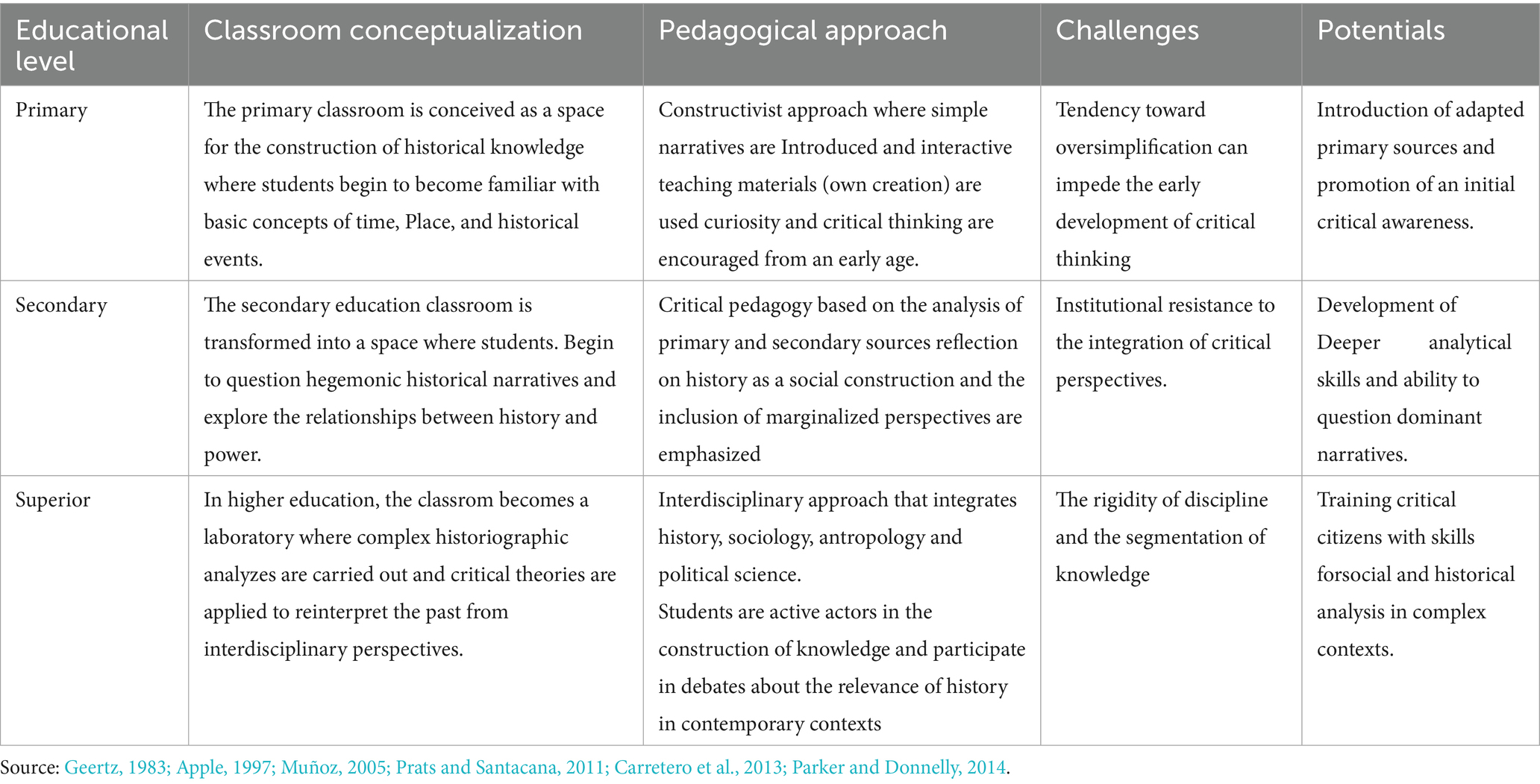

One of the recurring themes in literature is the conception of the classroom as a space where historical knowledge is constructed and reconstructed. According to Wineburg (2001), the classroom offers a unique context in which students can interact with primary and secondary sources, allowing them to develop historical analysis skills that go beyond mere memorization of facts, this approach aligns with critical pedagogy of Paulo Freire (1970), who advocates learning that empowers students to question and reinterpret hegemonic historical narratives. This helps to orient the classroom as a laboratory of historical and social analysis, from the primary, secondary and higher educational level, which considers a pedagogical perspective as presented in Table 2.

Table 2 allows us to analyze from a socio-critical perspective, the classroom in primary education is configured as the space where the bases of historical thinking begin (Parker and Donnelly, 2014). Learning that empowers students even at early stages is important, introducing historical concepts that allow them to begin to question their environment (Lee, 2005). Although Vygotsky (1978) suggests that learning is a socially mediated process, at the primary level the challenge lies in balancing the simplicity necessary for children’s understanding with the critical depth that prepares the ground for later educational stages (Seixas, 2000).

In secondary education, the teaching of history is oriented towards the problematization of dominant historical narratives, which connects with the critical pedagogy of Giroux (1990). Here, students begin to recognize history as a social construction that reflects relationships of power and oppression. The inclusion of alternative historical perspectives (for example, from marginalized groups) challenges traditional knowledge structures (Muñoz, 2022), aligning with Wineburg’s (2001) vision that historical analysis should transcend the mere memorization of facts and promote a critical understanding of the past.

Finally, at the higher level, the classroom becomes a space for advanced research and the application of critical theories (Parada Ulloa et al., 2024). Said’s (1979) work on Orientalism is an example of how students can deconstruct historical narratives through critical analysis of colonial discourses. Becher and Trowler (2001) argue that interdisciplinarity in higher education is key to developing a holistic understanding of historical and social phenomena, which fosters sophisticated analytical capacity in students. Table 3 shows the development of historical thinking and its applicability in the classroom.

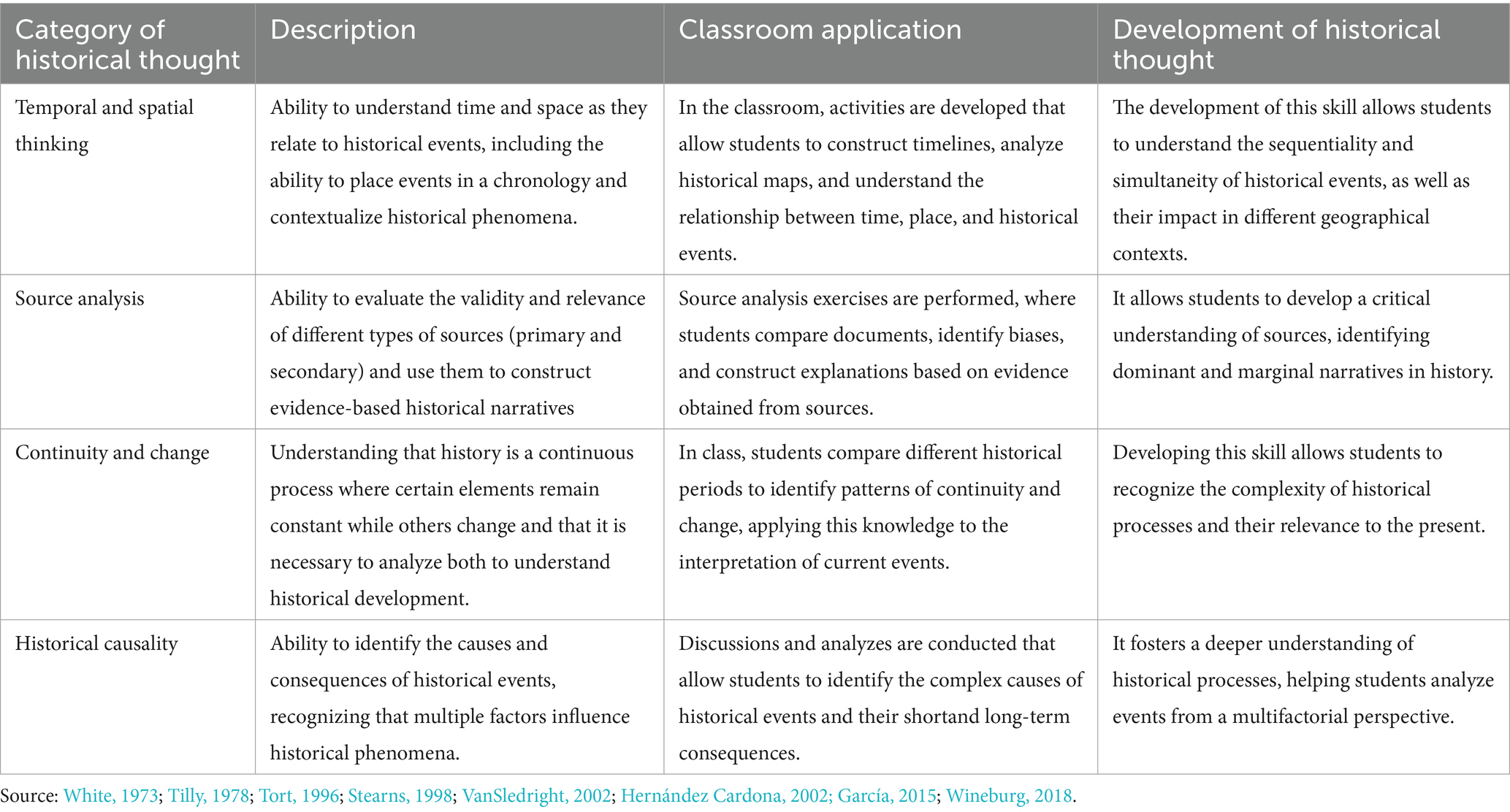

Table 3 summarizes the key categories of historical thinking that are developed in the classroom, focusing on how they are applied in the educational process and how they contribute to the development of critical thinking in students. These categories are essential to help students interpret and analyze history critically, based on the historical method. The historical method is presented as a key tool for students to develop critical and analytical skills (Santisteban et al., 2010). One of the purposes is that students not only memorize facts, but also learn to identify historical problems, analyze sources, understand historical changes and evaluate different perspectives (Prats, 2000, 2017).

6.1 Teaching history as a social practice

Another emerging category is the teaching of history as a social practice that reflects and shapes students’ understanding of their own society. Levstik and Barton (2022) argue that history taught in classrooms is not neutral; It is infused with values and perspectives that influence how students perceive their role in society. This approach underscores the importance of critical analysis of educational materials and curriculum, to ensure that a diversity of historical and social perspectives are included.

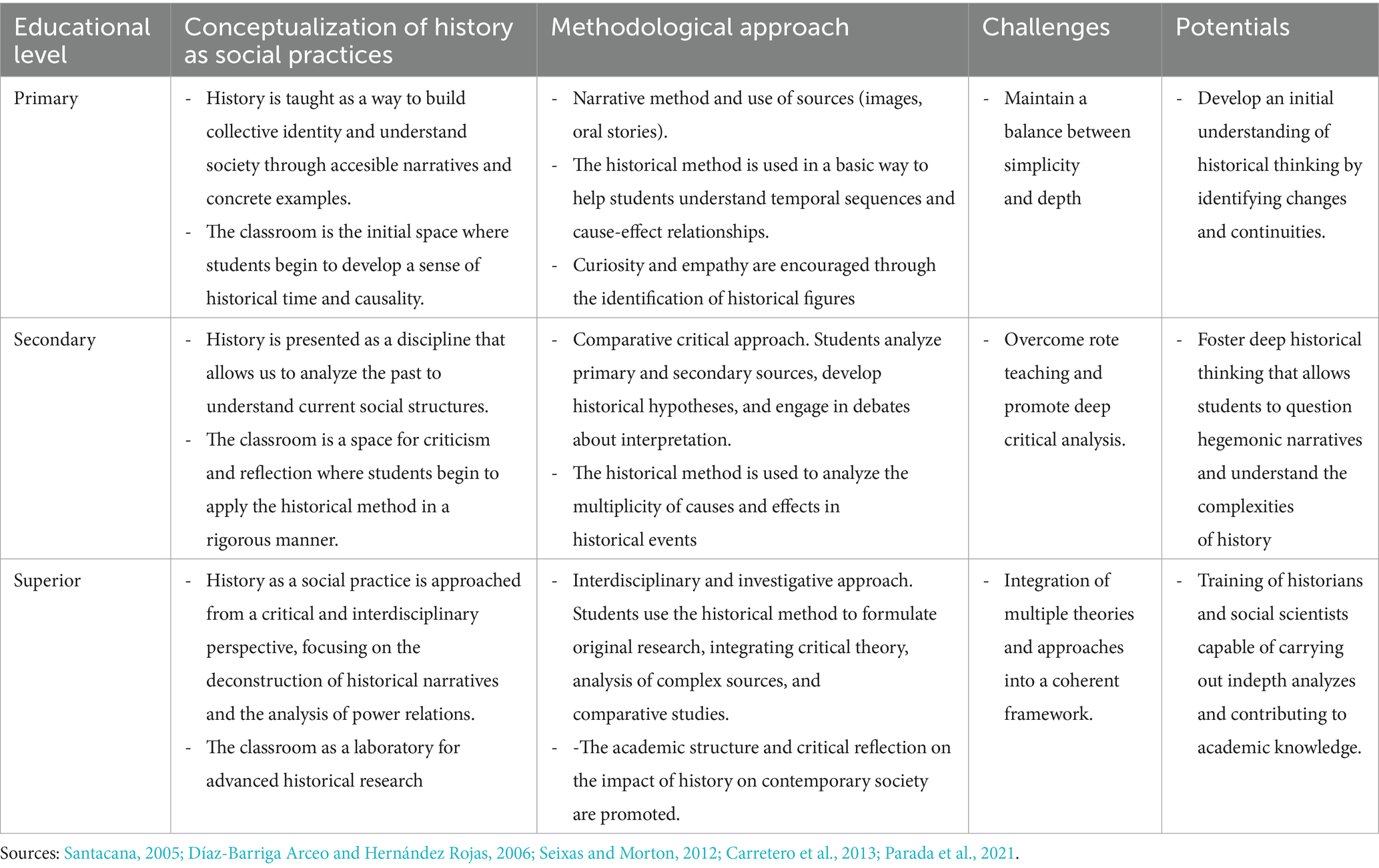

Table 4 helps to understand that in primary education, the teaching of history as a social practice aims to establish the bases for historical awareness in students (Seixas and Morton, 2012). Through hands on activities and accessible stories, students begin to understand how historical events affect their environment. This level is essential for children to acquire a first awareness of their historical and social identity (Santacana, 2005). The classroom in this context functions as a space where students can engage with history through direct experience and playful exploration.

Table 4. Teaching of history as a social practice and the development of historical thinking (Freinet, 1964b).

In secondary education, the teaching of history becomes more critical and reflective. Students begin to apply the historical method to analyze the causes and consequences of historical events, and the classroom becomes a space for deep debates and analysis. Wineburg (2001) highlights that this is the time when students must learn to think like historians, questioning dominant narratives and understanding the impact of history on today’s society. Here the development of historical thinking involves not only memorizing facts, but also understanding the complexity of historical processes.

In higher education, history is studied as a critical and multidisciplinary social practice that allows us to understand the power dynamics in contemporary society (Hobsbawm, 2010). The classroom is a laboratory where students confront different points of view and use the historical method rigorously, integrating critical theories and interdisciplinary approaches. The development of thinking in higher education involves the ability to carry out complex analyses, compare sources and theories, and produce research that contributes to the field of knowledge (Claure, 2019). The challenge lies in integrating multiple theoretical and methodological approaches into a coherent understanding of the past and its impact on the present.

Teaching research allows students to get involved in the process of constructing historical knowledge, which fosters meaningful learning (Ausubel et al., 1983; Pozo, 1997; Díaz-Barriga Arceo and Hernández Rojas, 2006; Díaz-Barriga, 2013). It is necessary for students to experience the research process through the collection of documents and analysis of sources. By doing so, students not only gain knowledge, but also develop the ability to ask questions, analyze evidence, and construct their own interpretations based on concrete data.

Consequently, Prats and Santacana (2011) point out the importance of teaching students at all educational levels, arguing that the development of these skills is fundamental for the formation of critical citizens, capable of analyzing and understand historical and social processes in their complexity. By integrating the historical method into teaching, active and meaningful learning is promoted, which prepares students not only for their academic studies, but also for their lives as informed and engaged citizens.

6.2 Interdisciplinarity in historical-social análisis

The historical-social analysis within the classroom-laboratory is characterized by its interdisciplinary approach. This type of analysis goes beyond the mere accumulation of data; focuses on understanding the underlying structures that shape historical facts and social phenomena.

1. By integrating disciplines such as history, sociology, anthropology, and political science, educators can offer a more holistic view of social and historical phenomena.

2. Interdisciplinarity allows students to analyze events and processes from different perspectives, integrating elements of sociology, politics, economics and culture in the interpretation of historical facts.

According to Becher and Trowler (2001), this interdisciplinarity in teaching encourages a deeper understanding of the topics studied, while promoting complex analytical skills in students. In the historical-social analysis, three fundamental categories emerge as pillars of interpretation: culture, power and social change. These categories allow students to understand how social and political structures are shaped over time, and how cultural ideas and beliefs influence historical processes (Apple, 1997).

Culture is analyzed as a set of practices and representations that not only reflect social reality, but also constitute it. In this sense, cultural analysis in the classroom-laboratory includes the study of texts, images and symbols that have been used to narrate history and legitimize forms of power. Clifford Geertz (1983) have argued that culture must be interpreted in terms of systems of meaning that organize experience and guide human action.

Power, for its part, is a central category in the interpretation of social and historical dynamics. Michel Foucault (1975) argues that power is not simply a structure that is exercised from above, but is distributed throughout social networks and manifests itself in everyday relationships. In the classroom laboratory, students are encouraged to examine how power relations have influenced the shaping of history and societies, and how those relations have been resisted and transformed over time.

Finally, social change is another key category in historical-social analysis. The processes of change and continuity allow students to understand how societies evolve and how social movements, revolutions, and scientific and technological advances have influenced these processes. Charles Tilly (1978) and other social change theorists have argued that social conflicts are a primary source of historical transformation, and these conflicts are analyzed in the classroom-laboratory through case studies and debates.

7 Discussion, relevance, and implications

This study highlights the urgent need to transform the teaching of Social Sciences and History through the development of critical thinking and the reconstruction of historical discourse. Traditionally understood as a mechanism for social reproduction (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977), the school is re-signified here as a space for cultural resistance (Freire, 1970; Giroux, 1983). In this regard, the notion of the classroom as a socio-historical laboratory emerges not only as a pedagogical metaphor but also as a transformative praxis that directly challenges the power structures embedded in curricula and everyday educational practices.

The theoretical evidence analyzed suggests that the teaching of history must go beyond the mere transmission of canonical content and focus on active inquiry processes, wherein students and teachers collectively construct meaningful, contextualized, and politically situated knowledge (Apple, 1997; Wineburg, 2001). This approach strengthens a critical citizenship capable of interpreting historical phenomena from multiple perspectives, including those systematically silenced by dominant narratives (Gramsci, 1975; Foucault, 1975).

However, this transformation is hindered by various structural, cultural, and institutional factors. Curricular rigidity, pressure for standardized results, lack of teacher training in critical approaches, and limited resources in vulnerable contexts pose significant barriers. Overcoming these challenges requires an educational policy committed to social justice and a pedagogical approach that fosters collaboration, historical empathy, and interdisciplinarity (Seixas, 2000; Becher and Trowler, 2001).

Moreover, interdisciplinary analysis—which integrates history, sociology, anthropology, and political science—enhances the interpretation of the past and strengthens students’ analytical capacities. This approach promotes an understanding of history as a social practice oriented toward questioning the relationships between culture, power, and social change (Geertz, 1983; Foucault, 1975; Tilly, 1978), equipping students with tools to critically interpret both the past and the present.

This study concludes that conceiving the classroom as a laboratory for socio-historical analysis constitutes an indispensable pedagogical strategy for the formation of critical, democratic individuals committed to social transformation. By integrating critical historical thinking and the sociology of education, it becomes possible not only to challenge hegemonic narratives but also to revalue the historical experiences of marginalized groups, fostering an inclusive and emancipatory pedagogy.

The incorporation of the historical method as an investigative practice, from early schooling to higher education, enables the development of fundamental skills such as source analysis, understanding of historical change and continuity, and identification of complex causalities. In this way, historical literacy is enhanced, moving beyond mere memorization of facts to stimulate reflection and informed social action.

Therefore, the contemporary challenge of teaching Social Sciences is not merely methodological but deeply political. It requires rethinking the role of teachers as agents of change, promoting educational policies that support critical practices, and ensuring material and formative conditions that allow all students access to an education that does not reproduce inequalities but questions and combats them. Ultimately, educating in and for history involves contributing to the construction of a more just, pluralistic, and socially aware society.

Author’s note

This work is part of the teaching research project transforming the Social Sciences Classroom into a Laboratory for Historical and Social Analysis. Teaching Research Project, ATA Program 21,991, University of Atacama, Chile. This 2-year project focuses on transforming the Social Sciences classroom into a laboratory for historical and social analysis. The main objective is to teach students how to conduct effective research.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MP-U: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CB-V: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was financed with funding of the Teaching Research 449 Project ATA Program 21991. University of Atacama, Chile.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aisenberg, B., and Alderoqui, S. (2007). Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales II. Teorías con prácticas. Buenos Aires: Paidós Educador.

Almansa, R. (2018). La empatía como método humanístico de docencia de la historia: sugerencias didácticas en un panorama de desvalorización de los estudios históricos. Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales: Revista de investigación 17, 87–98. doi: 10.1344/ECCSS2018.17.8

Álvarez, J. M., Molina, J., Miralles, P., and Trigueros, F. J. (2021). Competencias clave y transferencia de conocimiento social: percepciones del alumnado de secundaria. Sostenibilidad 13:2299. doi: 10.3390/su13042299

Andréu, J. (2002). Las técnicas de análisis de contenido: una revisión actualizada. Fundación Centro de Estudios Andaluces. España-Andalucía: Centro de estudios Andaluces.

Ausubel, D., Novak, J., and Hanesian, H. (1983). Psicología educativa: un punto de vista cognoscitivo. México: Trillas.

Barton, K. (2008). Research on students. Ideas about history. Levstik, L. & C. Tyson (Eds.), Handbook of research in social studies education (pp. 137–153). New York: Routledge.

Becher, T., and Trowler, P. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the cultures of disciplines. 2nd Edn. Buckingham: Open University Press/SRHE.

Bernstein, B. (1971). Clase, códigos y control: Estudios teóricos hacia una sociología del lenguaje. Londres: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J.-C. (1977). La reproducción: Elementos para una teoría del sistema de enseñanza. Barcelona: Editorial Laia.

Cárdenas, I. (1991). Las ciencias sociales en la nueva enseñanza obligatoria. España: Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia.

Carretero, M., Castorina, J. A., Sarti, M., Van Alphen, F., and Barreiro, A. (2013). La Construcción del conocimiento histórico. Propuesta Educativa 39, 13–23. Available: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=403041710003

Carretero, M., Jaccott, L., Limón, M., and y López-Monjón, A. (2002). Construir y enseñar las Ciencias Sociales y la Historia. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Carretero, M., and Van Alphen, F. (2014). ¿Cambian las narrativas maestras entre los estudiantes de secundaria? Una caracterización de cómo se representa la historia nacional. Cogn. Instr. 32, 290–312. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2014.919298

Casanova, R., Connac, S., and Roelens, C. (2024). À la rencontre de figures inspirantes (d'hier et d'aujourd'hui) pour la socialisation démocratique dans et par l'éducation. Éduc. Social. 74. doi: 10.4000/12YXB

Chaux, E., Lleras, J., and Velázquez, A. M. (2004). Competencias ciudadanas. De los estándares al aula. Bogotá: Ministerio de Educación de Colombia.

Claure, J. L. (2019). Modelo didáctico para la enseñanza de la metodología de la investigación científica. GMB 42, 199–201. doi: 10.47993/gmb.v42i2.117

Cyrulnik, B. (2023). L'enfant a besoin de récits. Les Grands Dossiers des Sci. Hum. 72:8. doi: 10.3917/gdsh.072.0008

Cyrulnik, B. (2025). Bibliographie de Boris Cyrulnik [Sciences Humaines et Sociales]. SHS Cairn.info. Available online at: https://shs.cairn.info/publications-de-Boris-Cyrulnik--5318 (Accessed April 15, 2025).

Díaz-Barriga, Á. (2013). Secuencias de aprendizaje ¿un problema del enfoque de competencias o un reencuentro con perspectivas didácticas? Curriculum y formación de profesorado fecha de Consulta 7 de Julio de 2025]. 17, 11–33. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56729527002

Díaz-Barriga Arceo, F., and Hernández Rojas, G. (2006). Estrategias docentes para un aprendizaje significativo. México: McGraw-Hill.

Donovan, S., and Brasford, J. (2005). How students learn: History in the classroom. Washington: The National Academies Press.

Dubigeon, Y., and Pereira, I. (2024). Paulo Freire: Une fenêtre ouverte vers les penseurs de la démocratie radicale. Éducation et socialisation 74:74. doi: 10.4000/12yxj

Durkheim, É. (1897). Division du travail social (2.aed., p. I-XXIII). Félix Alcan. Available online at: http://classiques.uqac.ca/classiques/Durkheim_emile/division_du_travail/division_travail_preface2.html (Accessed January 08, 2024).

Fallace, T., and Neem, J. N. (2005). Pensamiento historiográfico: hacia un nuevo enfoque en la preparación de profesores de historia. Teoría e Investigación en Educación Social 33, 329–346. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2005.10473285

Fernández, F. (2002). El análisis de contenido como ayuda metodológica para la investigación. Revista de Ciencias Sociales. Available online at: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/153/15309604.pdf

Freinet, C. (1964b). Les techniques Freinet de l’École moderne. Armand Colin. Available at: https://www.neoprofs.org/t70154-les-techniques-freinet-de-l-ecole-moderne-1964#bottom (Accessed February 19, 2024).

Freinet, C. (1964a). Les invariants pédagogiques. Code pratique d’école moderne. Bibliothèque de l’École Moderne, 25.

Freinet, C. (1964b). Les techniques Freinet del’École moderne. Armand Colin. Available online at: https://www.neoprofs.org/t70154-les-techniques-freinet-de-l-ecole-moderne-1964#bottom (Accessed February 19, 2024).

García, G. (2015). La investigación en la formación docente inicial. Una Mirada desde la perspectiva sociotransformadora. Saber, Universidad de Oriente, Venezuela. 27, 143–151.

Gibbs, G., and Coffey, M. (2004). El impacto de la formación del profesorado universitario en sus habilidades docentes, su enfoque de la enseñanza y el enfoque del aprendizaje de sus estudiantes. Activ. Aprender. Alto. Edu. 5, 87–100. doi: 10.1177/1469787404040463

Giroux, H. A. (1988). Los docentes como intelectuales: hacia una pedagogía crítica del aprendizaje. Londres: Bloomsbury Academic.

Giroux, H. A. (1990). Los Profesores como intelectuales: hacia una pedagogía crítica del aprendizaje. Barcelona [etc.]: Madrid: Paidós Centro de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

Gómez, C., and Miralles, P. (2015). ¿Pensar históricamente o memorizar el pasado? La evaluación de los contenidos históricos de la educación obligatoria en España. Revista de Estudios Sociales 52, 52–69. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81538634004

Gómez, E., Fernando, D., Aponte, G., and Betancourt, L. Y. (2014). Metodología para la revisión bibliográfica y la gestión de información de temas científicos a través de la estructuración y sistematización. Universidad Nacional de Colombia DYNA 81, 158–163. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49630405022

Guerrero-Romera, C., and y Pérez-Ortiz, A. L. (2022). Las necesidades formativas del profesorado en servicio para la enseñanza de habilidades de pensamiento histórico en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y el Bachillerato. Frente. Educ. 7:934646. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.934646

Guerrero-Romera, C., Sánchez-Ibáñez, R., and y Miralles-Martínez, P. (2022). Aproximaciones a la enseñanza de la historia según un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales. Frente. Educ. 7:842977. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.842977

Hernández Cardona, X. (2002). Didáctica de las ciencias sociales, geografía e historia. Barcelona: Ed. Grao.

Holmes, B. (1994). Herbert Spencer (1820-1903). Perspectivas: revista trimestral de educación comparada XXIV, 543–565.

Kreidler, W. J. (1984). La resolución creativa de conflictos (manual de actividades) (G. Gutiérrez Gómez & A. Restrepo Gutiérrez, Trads.). Centro Persona y Familia – Fundación para el Bienestar Humano - SURGIR.

Lee, P. (2005). Alfabetización histórica: teoría e investigación. Int. J. Hist. Aprender. Enseñar. Res. 5, 29–40. doi: 10.18546/herj.05.1.05

Levstik, L. S., and Barton, K. C. (2022). Doing history: investigating with children in elementary and middle schools. 6th Edn: Routledge.

Maggioni, L., VanSledright, B., and y Alexander, P. A. (2009). Caminando sobre las fronteras: una medida de la cognición epistémica en la historia. Rev. Educ. Exp. 77, 187–214. doi: 10.3200/jexe.77.3.187-214

Martínez Díaz, J. (2023). Investigación formativa en programas de pedagogía de la Universidad de Atacama. Disponible en línea en. Available at: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/198426

McLaren, P. (1984). La vida en las escuelas: una introducción a la pedagogía crítica en los fundamentos de la educación. México D.F: Siglo XXI.

Morin, E. (2017). Science avec conscience. Le Seuil. https://www.seuil.com/ouvrage/science-avec-conscience-edgar-morin/9782757869796

Morzadec, C. (2024). Francisco Ferrer, une figure inspirante pour les mouvements de rénovation pédagogique de la transition démocratique espagnole? (1975-1978). Éducation et socialisation. Les Cahiers du CERFEE 74:74. doi: 10.4000/12yxh

Muñoz, C. (2005). Ideas previas en el proceso de aprendizaje de la historia. Caso: estudiantes de primer año de secundaria, Chile. Geoenseñanza 10, 209–218. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36010207

Muñoz, I. (2022). Hayden White y los historiadores: la historia como literatura. Santiago: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Ocampo López, J. (2008). Paulo Freire y la pedagogía del oprimido. Revista Historia de la Educación Latinoamericana 10, 57–72. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86901005

Palacios, R. J. (2020). “Experimentación y análisis del uso de los videojuegos para la Educación Patrimonial” in Estudio de caso en 1. o de ESO (Huelva: Universidad de Huelva).

Parada, M., Lárez, J., and Sobarzo, R. (2021). “La Sistematización de Experiencias como Forma de Producción de Conocimiento en Educación” in Una visión desde el Surgimiento de las Epistemologías desde el Sur, pp. 378–386. En John Cobo Beltrán, Pablo Torres Cañizalez (Fondo Editorial Municipalidad de Lima: Una mirada a la investigación y a la responsabilidad social. Lima).

Parada Ulloa, M., Lárez Hernández, J. H., and Vega-Gutiérrez, Ó. (2024). Building knowledge from the epistemology of the south: the importance of training researchers in initial teacher training. Front. Educ. 8:1231602. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1231602

Parker, R. J., and Donnelly, D. (2014). Changing conceptions of historical thinking in history education: an Australian case study. Revista Tempo e Argumento, Florianópolis 6, 113–136. doi: 10.5965/2175180306112014113

Perafán Cabrera, A. (2013). Reflexiones en torno a la didáctica de la historia. Revista Guillermo de Ockham 11, 149–160. doi: 10.21500/22563202.2343

Plá, S. (2008). “El discurso histórico escolar. Hacia una categoría analítica intermedia” in Investigación social. En Investigación Social. Herramientas teóricas y Análisis Político del Discurso (México: Casa Juan Pablos), 41–56.

Prats, J. (2000). Dificultades para la enseñanza de la historia en educación secundaria. Teoría y Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, núm. 5, 78–91.

Prats, J., and Santacana, J. (2011). “Los contenidos en la enseñanza de la historia” in En Didáctica de la Geografía y la Historia (Barcelona: Graó), 31–50.

Prats, J. (2017). Retos y dificultades para la enseñanza de la historia. En S. Camañanes and J. Molero y D. Rodríguez. La historia en el aula: innovación docente y enseñanza de la historia en educación secundaria (pp. 15–32). España: Milenio

Reisman, A. (2012). Leyendo como un historiador: Una intervención curricular de historia basada en documentos en escuelas secundarias urbanas. Cogn. Instr. 30, 86–112. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2011.634081

Rennie, D. L. (2012). Investigación cualitativa como hermenéutica metódica. Psico. Métodos 17, 385–398. doi: 10.1037/a0029250

Sáez, J. M., Cózar, R., and Domínguez, J. (2016). Realidad aumentada en Educación Primaria: comprensión de elementos artísticos y aplicación didáctica en ciencias sociales. Cavar. Edu. Apocalipsis 34, 59–75. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6765342

Salazar-Jiménez, R., Barriga-Ubed, E., and Ametller-López, Á. (2015). El aula como laboratorio de análisis histórico en 4o de ESO: El nacimiento del Fascismo en Europa. Rev d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació 8, 94–115. doi: 10.6018/reifop.22.2.370371

Santacana, J. (2005). Reflexiones en torno al laboratorio escolar en ciencias sociales. Iber: Didáctica de las ciencias sociales, geografía e historia 43, 7–14. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?author=J.+Santacana&publication_year=2005&title=Reflexiones+en+torno+al+laboratorio+escolar+en+ciencias+sociales&journal=Iber:+Didáctica+de+las+ciencias+sociales+geografía+e+historia&volume=43&pages=7-14

Santisteban, A., González, N., and Pagés, J. (2010). Una investigación sobre la formación del pensamiento histórico. Ponencia presentada en el XXI Simposio Internacional de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales Metodología de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Zaragoza, España. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/27571877/Una_investigaci%C3%B3n_sobre_la_formaci%C3%B3n_del_pensamiento_hist%C3%B3rico (Accessed April 15, 2024).

Santisteban Fernández, A. (2017). Del tiempo histórico a la conciencia histórica: cambios en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de la historia en los últimos 25 años. Diálogo Andino N°53, 89–99. doi: 10.4067/S0719-26812017000200087

Seixas, P. C. (2000). “Schweigen! Die kinder! Or, does postmodern history have a place in the schools?” in En knowing, teaching, and learning history: National and international perspectives (EEUU: New York University Press), 19–37.

Seixas, P., and Morton, T. (2012). Los Seis Grandes Conceptos de Pensamiento Histórico. Toronto, ON: Nelson.

Smith, M., and y Breakstone, J. (2015). Evaluaciones históricas del pensamiento: una investigación en la validez cognitiva. Nuevas direcciones para evaluar el pensamiento histórico. Nueva York, EE. UU.: Routledge 233–245.

Trigueros-Cano, F. J., Molina-Saorín, J., López-García, A., and Álvarez-Martínez-Iglesias, J. M. (2022). Percepción del profesorado de primaria y secundaria sobre la evaluación de conocimientos y habilidades históricas a partir de actividades y ejercicios en el aula. Frente. Educ. 7:866912. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.866912

Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., and Ginns, P. (2005). Pedagogía fenomenográfica y un inventario revisado de enfoques para la enseñanza. Educ Superior Res. Dev. 24, 349–360. doi: 10.1080/07294360500284730

VanSledright, B. (2002). In search of America’s past: Learning to read history in elementary school : Teachers College Press.

Vásquez, G. (2014). Concepciones de los estudiantes chilenos de educación media sobre el proceso de transición de la dictadura a la democracia (tesis doctoral inédita). Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid. Available online at: https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/10324/4849/1/TESIS519-140519.pdf (Accessed April 10, 2024).

White, H. (1973). Metahistory: The historical imagination in nineteenth century Europe : Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia. EEUU: Temple University Press.

Keywords: history, critical pedagogy, education, didactics of history, classroom laboratory

Citation: Parada-Ulloa M and Burgos-Videla C (2025) The classroom as a laboratory for historical thinking: a pedagogical approach to analyzing past and society. Front. Educ. 10:1485404. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1485404

Edited by:

Raúl Ruiz Cecilia, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Dolana Mogadime, Brock University, CanadaTeresa Benito Aguado, Public University of Navarre, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Parada-Ulloa and Burgos-Videla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcos Parada-Ulloa, bWFyY29zLnBhcmFkYUB1ZGEuY2w=

Marcos Parada-Ulloa

Marcos Parada-Ulloa Carmen Burgos-Videla

Carmen Burgos-Videla