- Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, American University of Ras Al Khaimah, Ras al-Khaimah, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: The global COVID-19 pandemic resulted in 87% of students around the world being affected by school closures. This led to countries around the world implementing emergency plans to help mitigate the risks of exposure and spread of the virus. Schools mobilized resources and shifted to a new modality of instruction to assure the continuity of teaching and learning: online learning. There were numerous challenges for all stakeholders involved in this dynamic new learning space. At the forefront of these challenges was the involvement of, and communication with, parents regarding their child’s education at home. The pandemic presented schools with an opportunity to connect with families and strengthen collaboration. As communication is an integral component of collaboration, this study sought to ascertain the degree to which parent-school communication and parental involvement may have changed during and after the pandemic.

Methods: A quantitative approach was employed to ascertain the views of parents of students in grade one through grade four attending private schools in the UAE. The researchers constructed a 30 item, Likert-style instrument which was subsequently validated for use and internal consistency assessed. The total number of responses was 479, which were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). The researchers made use of an exploratory factor analysis and Wilcoxon signed-rank test to both explore parent perceptions during and after the pandemic.

Results: These findings suggest that adjustments in communication strategies had a significant impact on how parents perceived their communication with schools. Our results indicate a significant shift in the accessibility and effectiveness of parent-school communication, suggesting that the pandemic triggered positive change in several aspects of educational communication. Parental involvement throughout and after the pandemic displayed a multifaceted pattern. Although parents became more attentive to their children’s academic success after the pandemic, there was a decrease in their total involvement in other educational activities.

Discussion: These mixed results suggest that while there was an overall trend of decreased parental involvement during and after the pandemic, individual variations exist, highlighting the need for school leaders to consider more nuanced approaches to facilitating and supporting parental involvement. Based on the results, the authors identified six suggestions for future practice to guide school leaders in fostering effective parent-school communication practices in post-Covid learning environments. Research concerning the impact COVID-19 has had on educational leaders’ interactions with parents is limited. Indeed, the degree to which parent-school communication and parental involvement have been successful during and after the pandemic has yet to be investigated. As such, this research aims to contribute to closing this gap in literature and provide school leaders and policymakers with practical suggestions for strengthening relationships between schools and families.

1 Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic affected 87% of students worldwide due to school closures (UNESCO Global Education Coalition, 2020). In response, countries implemented emergency plans to mitigate the risks of exposure to and spread of the virus. Many countries, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), temporarily closed educational institutions, necessitating a shift to a distance-learning environment (Sacks et al., 2020). Schools had to mobilize resources and transition to online learning to ensure the continuity of teaching and learning. This new learning space presented numerous challenges for all stakeholders involved, particularly for parents who were at the forefront of involvement and communication regarding their child’s education at home.1 As primary caregivers in mandated distance learning environments, parents assumed a unique role, often acting as secondary instructors and providing oversight of their child’s academic progress and wellbeing. This was especially true for children in the early years and lower elementary education.

While many schools began to reopen in the following academic year, the interruption to student learning did not go unnoticed. Among the various emerging challenges, this study focuses on home learning in general and highlights the role of parents in their children’s education during the pandemic. In the next academic year, policymakers and school leaders attempted to develop and implement policies and plans tailored to address the fundamental changes to schooling that occurred due to COVID-19. Although multiple studies have investigated the degree to which these attempts have been successful, less attention has been paid to the impact COVID-19 had on continued parent involvement and parent-school communication in the post-pandemic period.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the perspectives of parents with children in grades one through four who attend private schools in the UAE regarding communication practices and parental involvement during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. This age group consists of elementary school students who often require purposeful guidance, scaffolding, and support (Hammond, 2014; Kamrani et al., 2024). Consequently, this learner population was uniquely affected during distance learning due to COVID-19. Likewise, parents of children in this age range faced unique challenges in supporting their young learners. As a result, the pandemic presented schools with an opportunity to foster closer collaboration between families and educational institutions. The effectiveness of parent-school communication and parental involvement during and after the pandemic remains to be explored. Thus, this research aims to address this gap in the literature and provide school leaders and policymakers with practical recommendations for strengthening relationships between schools and families.

2 Theoretical framework

Parental involvement in education is a critical component of student success, and the COVID-19 pandemic has brought this issue into sharp focus. It is essential to examine and acknowledge the relevance of parental involvement while also considering the challenges and barriers faced by parents who were forced to co-teach their children at home without prior preparation or training during the lockdown. This unique circumstance not only highlighted the challenges parents faced but also intensified existing ones. Despite these challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to recognize its potential benefits, such as redefining the role of parental involvement and understanding parents’ perceptions during these challenging times (Lu, 2020). A significant amount of research related to parental communication is grounded in Epstein’s (1987) framework, which identifies communication with parents as one of the six major types of parental involvement. In conclusion, Epstein et al.’s (2018) framework underscores the critical role of robust school-family communication in enhancing student achievement, emphasizing the need for educators and policymakers to prioritize and implement strategies that strengthen these vital partnerships.

2.1 Parental involvement in education

Parental involvement has been investigated for decades, emphasizing its significance for student success (Hill and Tyson, 2009; Yang et al., 2023; Omarkhanova et al., 2024). However, parental involvement is a multifaceted construct that has been defined in several ways. One definition proposed by Antipkina and Ludlow (2020) offers a comprehensive view, describing parental involvement as a “continuum of parenting behaviors ranging from those representing lower levels of involvement to those representing higher levels of involvement” (856). Conclusively, Li et al. (2024) research underscores the critical role parents have adopted as emotional anchors in the online learning landscape, highlighting the need for educational institutions to recognize and support this expanded parental involvement in fostering students’ psychological wellbeing and academic engagement.

The most prominent aspect of parental involvement occurs at home. During COVID-19, parents were unexpectedly required to address the new challenges posed by the pandemic, during which online learning replaced traditional classroom learning. The introduction of new learning modalities added complexity to the role of parental involvement in their children’s education. Consequently, parental involvement emerged as a major influencing factor in online education, with parents now bearing significant responsibility for their children’s education (Haritha, 2021; Budiningsih and Abdulrahman, 2022).

Considering the comprehensive changes that have restructured learning, parental involvement has become crucial not only for their children’s academic success but also for the continuity of learning, which is primarily happening at home. However, parents have identified several challenges and barriers to online learning (Abuhammad, 2020). These challenges include financial, logistical, personal, and technical barriers. Young learners require technical support to access online lessons, resources, and assessments (Dong et al., 2020). Consequently, parents are expected to receive support from the school’s team of experts to overcome these challenges and effectively monitor their children’s progress at home. Garbe et al. (2020) identified a few key challenges to engaging parents during COVID-19: limited resources to facilitate effective learning at home, balancing responsibilities, and additional stress. They highlight the importance of clear communication and collaboration between parents and schools. Fundamentally, the research by Haritha (2021) and Budiningsih and Abdulrahman (2022) underscores the pivotal role parents have assumed in the online learning landscape, highlighting the need for educational institutions to recognize and support this increased parental responsibility to ensure optimal student outcomes in digital education environments.

2.2 School leaders’ approaches to communication

Effective communication strategies employed by school leaders—such as workshops, training sessions, and informational materials—can significantly enhance parental involvement, which, in turn, positively impacts student outcomes (Theodoros et al., 2022; Mehmood, 2024). The literature suggests that leaders should consistently improve and broaden their communication abilities to ensure that parents are actively engaged in their children’s education, particularly during online learning.

Effective school-parent communication is enhanced through distributed leadership, where parents are engaged as important stakeholders in the decision-making processes led by school leaders. This collaboration fosters stronger school-family relationships, ultimately improving parental involvement and support in their children’s educational journeys (Erol and Turhan, 2018). Distributed leadership approaches may be particularly important in distance learning contexts, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents’ involvement in decisions about online learning platforms, schedules, and resources creates a shared responsibility that may help reduce misunderstandings and increase engagement (Dong et al., 2020). This more inclusive approach also helps address challenges related to equity and access, ensuring that diverse parental perspectives contribute to identifying solutions (Harris and Jones, 2020). Engaging these diverse perspectives may help bridge gaps in parent-school communication and parental involvement. In essence, distributed leadership emerges as a powerful framework for fostering academic continuity while simultaneously cultivating trust and reciprocal respect in the school-family partnership, ultimately enhancing the educational experience for all stakeholders involved.

The pandemic has demonstrated that distance learning can be effectively conducted without the physical presence of learners and teachers in the same location. This highlights the significance of implementing effective communication strategies to overcome this distance (Moore, 2013; Levy, 2024). Borup et al. (2013) emphasized that parental participation in online education differs from traditional in-person learning, necessitating a reevaluation of parental roles and responsibilities. According to Gonzalez-DeHass et al. (2022), the shift to online learning requires parents to engage more proactively in communicating with educators. Despite the spontaneous and uncoordinated actions taken by schools and parents during the initial transition to online learning, there is a clear need for more structured approaches to communication and involvement.

2.3 Parent-school communication in distance learning

Communication is fundamental to building the school community; therefore, teachers must continuously develop and expand their skills if they want to engage parents effectively in their children’s education during online learning (Muir et al., 2024). Remote learning does not require the physical presence of learners and teachers in the same location at the same time. It can occur anywhere outside the school premises and encompasses a range of modalities, including synchronous learning, where real-time interaction between teachers and students occurs, and asynchronous learning, which allows students to engage with materials and assignments at their own pace (Moore, 2013). These variations offer flexibility but also demand tailored approaches to instructional design and communication to meet the diverse needs of learners effectively (Borup et al., 2020). However, there is still insufficient research on this phenomenon within the fields of digital technologies, pedagogy, and psychology. The shift to online learning during the pandemic resulted in random and spontaneous actions from both schools and parents, highlighting the need for more structured approaches and further research in these areas (Borup et al., 2020; Lu, 2020). To synthesize, the abrupt transition to online learning during the pandemic exposed the lack of preparedness in both educational institutions and families, underscoring the urgent need for developing systematic strategies and conducting comprehensive research to enhance the effectiveness of remote education in future scenarios.

Many schools implement activities to encourage parental involvement in school life and decision-making processes. Parent communication programs, such as the Parent Teacher Association (PTA), are designed to enhance parental engagement in education. However, few parents are actively involved, as some may feel overwhelmed by the expectations placed upon them, leading to stress and disruption in family life (Lareau, 2019). During the pandemic, it became essential for parents to communicate frequently with school leaders and their child’s teachers. The increased expectations regarding their child’s education forced parents to respond to these new factors. Literature has emphasized a range of factors that shape parental involvement, one of which is the child’s age, as involvement tends to decrease as children transition from elementary to middle and high school (Hurley et al., 2017). This trend was disrupted during the pandemic, as parents were required to engage more actively across all age groups due to the demands of online learning. Another critical variable influencing the type of parental involvement is the actions taken by schools to promote such involvement. Parents are more likely to become actively engaged in supporting their children’s education when they perceive that the school is fostering this involvement (Eccles and Harold, 2013; Kim and Asbury, 2020). Ultimately, the research by Eccles and Harold (2013) and Kim and Asbury (2020) underscores the pivotal role of proactive school initiatives in cultivating meaningful parental engagement, highlighting the need for educational institutions to implement strategic measures that encourage and facilitate parents’ active participation in their children’s learning journey.

Establishing effective communication between parents and schools is crucial, as research shows that improved strategies during the pandemic enhanced accessibility and transparency (Garbe et al., 2020; Kim and Asbury, 2020). Conversely, further research identified challenges, such as inconsistent communication from certain schools, which led to dissatisfaction among parents (Kim and Asbury, 2020; Borup et al., 2020; Roy et al., 2022). These findings emphasize the significance of developing dependable and efficient communication methods to assist parents and increase their involvement in their children’s education during and after the pandemic (Eccles and Harold, 2013; Dong et al., 2020). Communication channels established by school leaders can support parents in managing the additional responsibilities to help maintain consistency in children’s education. More structured communication approaches better address the challenges of remote learning while contributing to long-term improvements in parent-school collaboration (Garbe et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2016; Sibley and Dearing, 2014).

Consequently, effective communication between schools and parents became crucial for meeting the needs of students, especially young learners. In these extraordinary and unprecedented circumstances, establishing strong working relationships between teachers and parents can only be achieved through effective communication. In this context, Mapp and Kuttner (2013) further suggest that frequent communication between guardians and schools promotes trust and a sense of collaboration, both of which are imperative for maintaining meaningful parental involvement. Goodall (2022) also emphasizes that the level of parental involvement can depend on the degree to which schools implement structured communication approaches, as these strategies ensure that guardians are regularly informed about their child’s progress and are better equipped to support their child’s learning at home.

3 Methodology

This study sought to investigate parents’ perceptions of parent-school communication and parental involvement during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. A quantitative approach was employed to gather the views of parents of children in grades one through four who are attending private schools in the UAE.

3.1 Operational definitions

Specific terms were used throughout this study to clarify how we conceptualize the relevant variables.

Parent-School Communication: The interaction between parents and school leaders regarding a student’s academic progress, behavioral issues, and other school-related matters. This communication may involve scheduled meetings, emails, phone calls, and the use of school communication platforms.

Parental Involvement: The actions and behaviors of parents that directly support their child’s learning and development, both at home and in school. This involves helping with homework, encouraging reading and educational activities at home, monitoring the child’s academic progress, and fostering a cheerful outlook toward education.

Accessibility: the ease with which parents can reach and contact school leaders or personnel, including the availability of school staff to resolve problems, promote involvement, and provide support. Clarity: the degree to which information provided by the school is comprehensible, transparent, and detailed enough for parents to act on. Effective communication entails the use of unambiguous language, clear explanations of policies, and accurate updates on students’ academic performance or school events.

Frequency: The regularity with which schools inform parents about changes, academic performance, and other pertinent issues. This includes the consistency of communication via newsletters, meetings, or other platforms to guarantee that parents stay informed and engaged in their child’s education.

3.2 Research questions and hypotheses

We selected a target group of students in grades one through four because research indicates that parental involvement and communication are critical during these formative years (Castro et al., 2015). Children in this age range benefit significantly from active parental involvement and effective communication between their guardians and their schools. A closer examination of how these changes have influenced parents’ perceptions during and after the pandemic is necessary, as the dynamics of parent-school communication have been profoundly disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The following research questions and hypotheses were formulated to guide the study:

1. How did parents’ perceptions of parent-school communication change during and after the COVID-19 pandemic among parents of students in grades one through four?

2. How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence parents’ perceptions of their involvement in their children’s education through school communication?

In response to these research questions, we drafted two speculative hypotheses. Firstly, we hypothesize that parent perceptions of Parent-School communication improved post-pandemic in terms of accessibility, clarity, and frequency, reflecting schools’ adaptation to the challenges of remote learning during the pandemic. Secondly, we hypothesize that the COVID-19 pandemic influenced parents’ perceptions of their involvement in their children’s education through school communication by shaping their experiences with differing school communication strategies and their role in the academic monitoring of their children during the pandemic.

3.3 Sampling

Our focus was on investigating the perspectives of parents with elementary school-aged children. Initially, convenience sampling was employed, followed by snowball sampling for data collection. We identified a minimum sample size of 384 respondents based on the estimates outlined below. According to the UAE’s Ministry of Education (MOE) open data source (Ministry of Education, 2024), there were 406 private schools across the UAE during the 2023–2024 academic year. We estimated that each school may have around 750 students enrolled in grades one through four. Consequently, the total estimated number of students would be 302,250. To account for up to two parents and/or guardians per child, we doubled this figure, resulting in an estimated total population of 604,500. We considered the total population for the study. The sample size was calculated using a 95% confidence level, a 0.5 standard deviation, and a ±5% margin of error, resulting in a minimum sample size of 384 (Conroy, 2016). The number of responses received exceeded this minimum, with 479 respondents completing the questionnaire.

3.4 Instrumentation

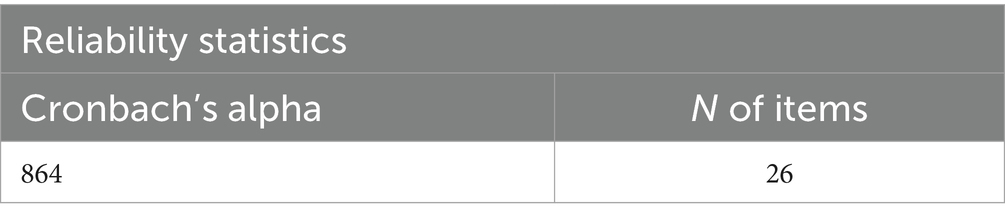

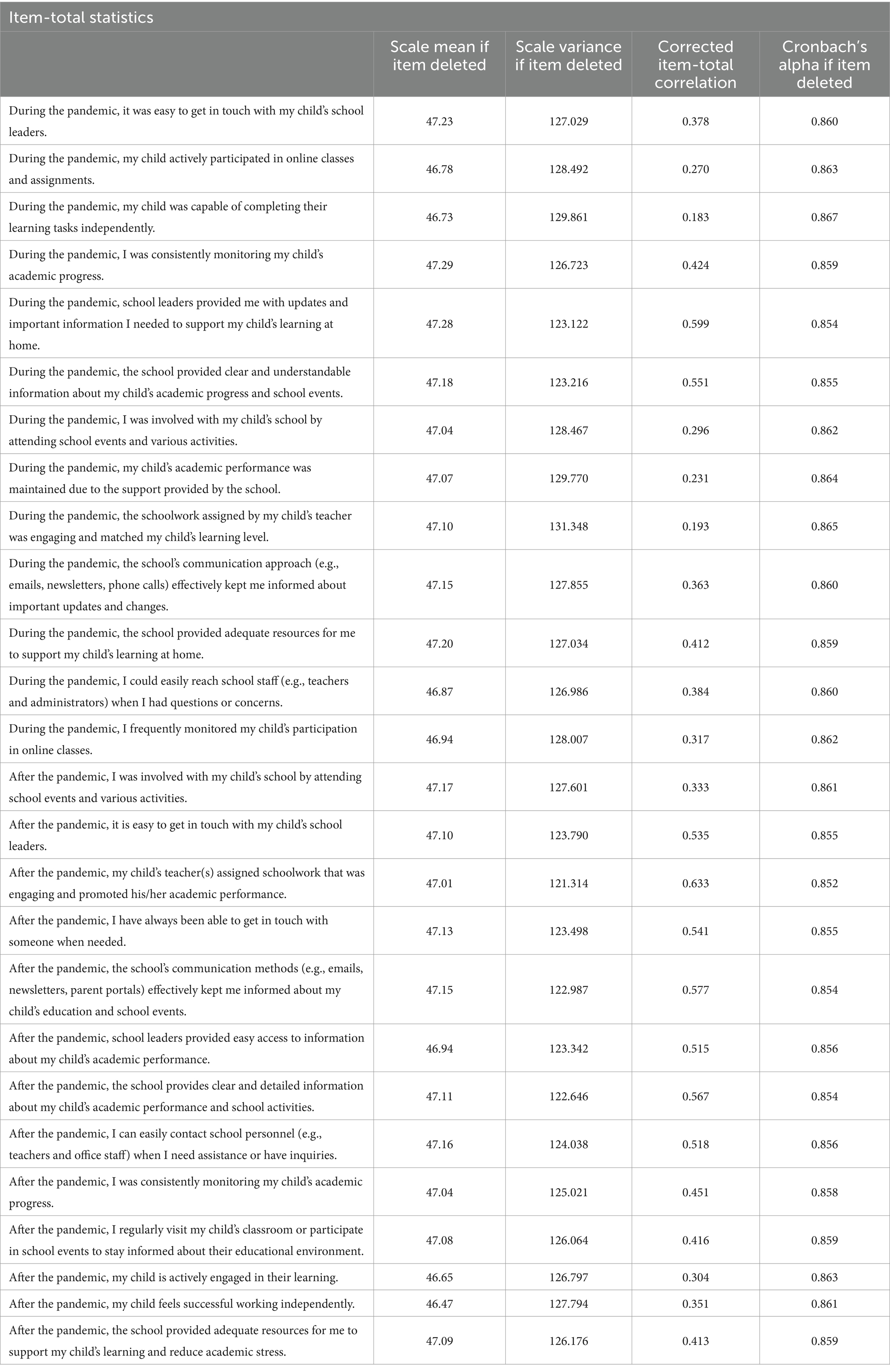

We constructed a questionnaire to elicit participants’ perceptions about parent-school communication and parental involvement during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. We developed a structured, 4-point Likert-style questionnaire comprised of (30) items. The questionnaire included demographic items (4 items), questions about parental perceptions of communication during the COVID-19 pandemic when students were learning remotely (13 items), and questions about parental perceptions of communication after the COVID-19 pandemic, when students returned to face-to-face learning (13 items). Upon receiving and cleaning survey data from our sample, we examined its underlying structure using exploratory factor analysis and measures of internal consistency. Specifically, we used Cronbach’s alpha to calculate the reliability coefficient of the questionnaire (Cronbach, 1951). The reliability of the questionnaire must meet specific criteria: Cronbach’s alpha > 0.7; CR > 0.7; AVE > 0.5 (Cheung et al., 2024; Youssef et al., 2023; Cronbach, 1951). Cronbach’s alpha served as the index for reliability analysis. Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.00 to 1.00, with a value of >0.9, considered excellent. For the purposes of this study, the overall Cronbach’s alpha for questions using a 4-point Likert scale was 0.864.

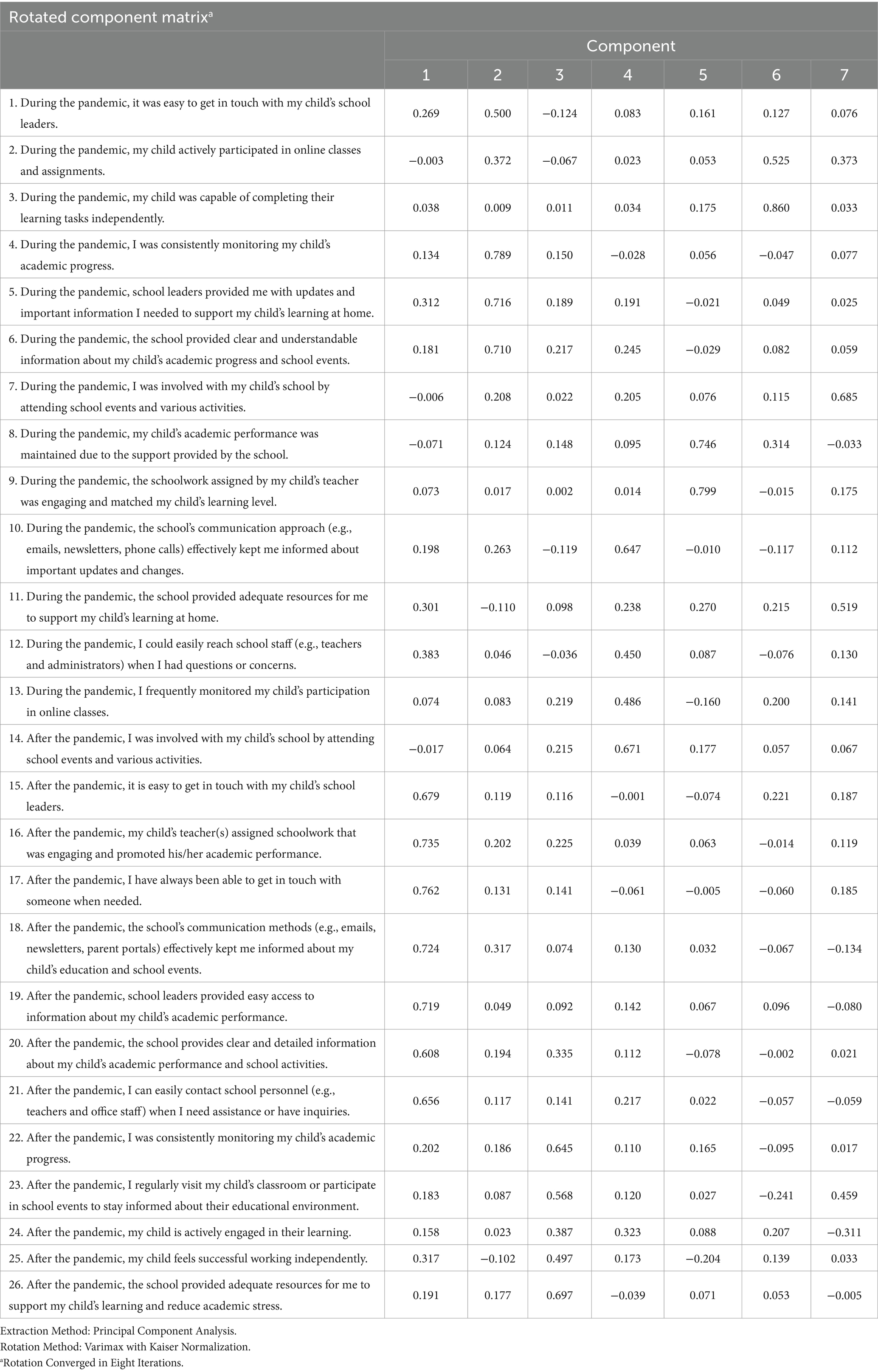

Factor-specific Cronbach’s alpha values were also calculated based on the exploratory factor analysis results. These values are as follows: Accessibility of school communication (post-pandemic) (α = 0.951), Frequency and quality of communication (during the pandemic) (α = 0.935), Parental involvement and school resources (post-pandemic) (α = 0.955), Effectiveness of communication methods (during the pandemic) (α = 0.936), Academic performance and school support (during the pandemic) (α = 0.935), Child participation and independent learning (during the pandemic) (α = 0.938), and Parental involvement and school resources (during the pandemic) (α = 0.938). Taken collectively, these results indicate excellent internal consistency for all identified factors, further supporting the reliability of the instrument.

3.5 Data analysis

Data collection involved recruiting 479 participants, all of whom were parents and/or guardians of students in grades one through four, with an equitable distribution across the grade levels. Guardians of grade one students included 123 respondents, representing 26% of the sample. Grade two guardians included 122 respondents, accounting for 25% of the sample. There were 117 respondents for grade three and grade four guardians, representing 24% for each grade. Of the total participants, 36% were Arab expatriates living in the UAE, while 64% were Emirati.

Given the quantitative approach employed in this study, a rigorous analysis was conducted using SPSS, a robust platform for analyzing quantitative data. First, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to test parents’ perceptions of parent-school communication and parental involvement in their children’s education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic based on the underlying factors identified by the EFA. This analysis aimed to discern patterns and relationships within the survey data. After identifying the relevant factors, those with high loadings were paired and subsequently tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

3.6 Exploratory factor analysis

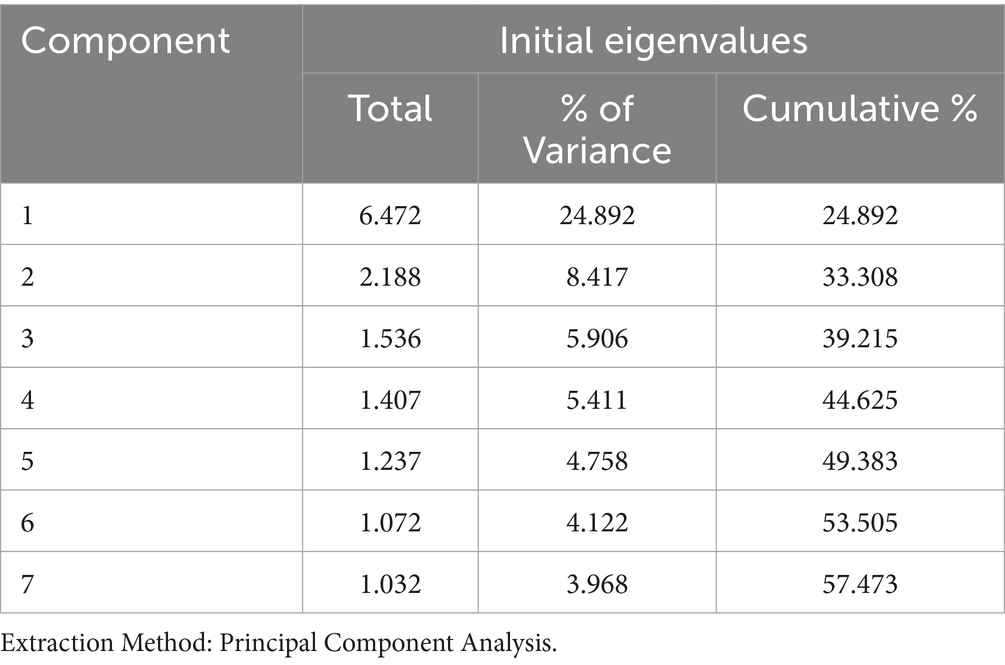

An EFA is a statistical tool used to identify patterns within a set of observed variables. It is often employed by researchers to explore relationships among a large number of variables (Watkins, 2021). The analysis employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) as the extraction method, with a Varimax rotation applied to simplify and clarify the factor structure. We chose a PCA for its efficiency in summarizing the variance across multiple items and Varimax rotation for its ability to produce orthogonal (uncorrelated) factors, aiding interpretability. Factors were retained based on eigenvalues greater than 1.0, a standard criterion in factor analysis for identifying components that explain meaningful variance. Additional consideration was given to the scree plot, which indicated a natural cut-off in the number of retained factors. Parallel analysis was not conducted in this study, as the eigenvalue and scree plot methods provided sufficient support for factor retention based on the observed data patterns.

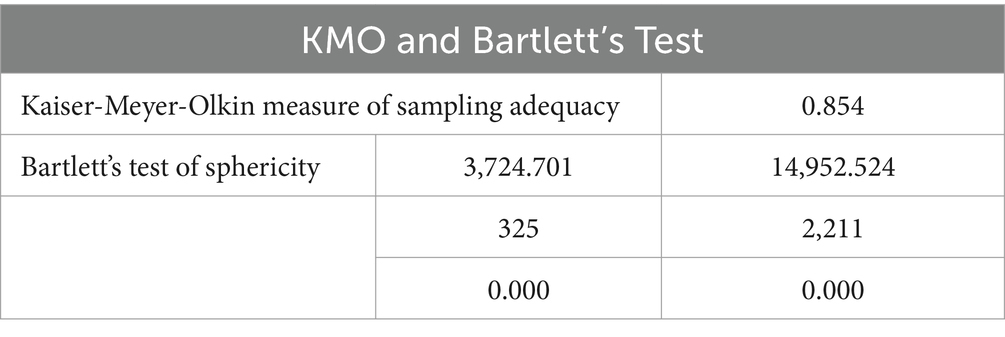

The suitability of the dataset for factor analysis was confirmed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, which yielded a value of 0.854, indicating strong adequacy. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy should ideally exceed 0.60 to ensure the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity assesses the strength of relationships among variables. A significant result from Bartlett’s test of sphericity should yield a p-value less than 0.05 to demonstrate significance. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), confirming that the correlations between variables were sufficiently large for EFA.

3.7 Validity of the questionnaire

The investigators adopted a comprehensive approach to substantiate the validity of the research tool. To ensure the validity of the survey instrument, construct validity was considered during its development. The items were designed to align with theoretical frameworks of parental involvement and school communication and were reviewed for face validity by three experts in the field. Each expert had an extensive background in parental engagement, educational communication, and survey methodology, with no less than 8 years of experience. The selection of three experts is consistent with Lynn’s (1986) recommendation for using a small panel of qualified professionals to evaluate the relevance and adequacy of survey items for content validation. Their feedback was used to ensure that the survey items adequately represented the constructs being measured and were appropriate for the target population, reinforcing the overall validity of the instrument (Lynn, 1986; Anastasi, 1988).

Construct validity was assessed using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). The EFA revealed a well-defined factor structure, with items loading significantly onto distinct factors representing various dimensions of parental engagement and school communication. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test yielded a value of 0.89, indicating sampling adequacy, while Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), supporting the use of factor analysis. Factors were retained based on eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and the scree plot analysis, aligning with best practices in construct validation (Field, 2024). By combining expert review for face and content validity with statistical validation techniques, the study ensured both content and construct validity, enhancing the reliability and credibility of the questionnaire for measuring parental involvement and communication practices.

3.8 Item analysis

The table in provides valuable insights into the internal consistency of the survey instrument by delineating item-total statistics and showing Cronbach’s alpha coefficient based on the exclusion of each item. Elevated corrected item-total correlations imply a robust association between the items and the aggregate score, thereby enhancing the reliability of the scale. The tabulation explains the item-total statistics of the survey, illustrating the impact of omitting each item on the scale’s overall reliability.

The analysis of item-total correlations and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients shows how individual items contribute to the overall reliability of the scale. The items demonstrate strong correlations, indicating their alignment with the overall scale. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients suggest that removing any single item would not significantly improve the scale’s reliability, confirming its internal consistency.

3.9 Limitations

This study provides valuable insights into parental perceptions of school communication and involvement during and after the COVID-19 pandemic; however, several limitations should be noted. First, the use of a closed-ended survey instrument, while effective for capturing quantitative data, limited the ability to capture nuanced, qualitative perspectives from parents. This approach precludes gaining deeper insights into what specific aspects of communication or involvement parents value most or seek to improve. Future research could complement such surveys with open-ended questions.

Secondly, due to the reliance on self-reported data from parents, response bias and recall accuracy are limitations of this study. Response bias refers to the potential tendency of respondents to provide answers they perceive as socially acceptable rather than their true perspectives (Teh et al., 2023; Kock, 2017). Further, because we asked participants to recall past events, they may not remember all events with equal accuracy.

We adopted a snowball approach, which may create a more homogeneous sample that reflects the characteristics of the initial participants rather than the broader population (Pasikowski, 2023). The survey instrument was designed to align with theoretical frameworks and demonstrated strong reliability and validity. The sample does reflect a specific population and context; this may limit the generalizability of the findings to other schools or regions with different demographic or educational characteristics.

Finally, because the data reflects only parental perspectives, it may not fully account for the broader dynamics of school-parent communication or involvement. Incorporating viewpoints from school personnel or triangulating data with other sources (e.g., records of actual communication frequency) could provide a more nuanced and holistic understanding (Tables 1, 2).

4 Results and discussion

The purpose of this analysis was to examine changes in parental involvement and school communication practices during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The results provide insights into key aspects of parental engagement, including the accessibility and clarity of communication channels, parental monitoring of academic progress, and collaborative decision-making between parents and schools.

4.1 Exploratory factor analysis

A total of seven factors with eigenvalues equal to or greater than 1.0 were identified and Table 3 presents a detailed analysis of the seven factors. In total, the seven factors derived from participant responses explained 56.620% of the variance in the data set. These seven factors validate the survey’s effectiveness in measuring seven unique dimensions of parental involvement and school communication practices (Table 4).

To further explore these underlying factors, an examination of the factor loadings was conducted resulting in a rotated component matrix, in Table 5, which displays the loadings for all seven factors. Factors 3 and 7 both measured aspects of parental involvement and school resources but were retained separately due to their focus on different contexts. Factor 3 addressed parental involvement and school resources specifically in the post-pandemic context, while Factor 7 focused on the same aspects during the pandemic period. The differentiation reflects temporal patterns rather than overlapping constructs, as the factor loadings demonstrated sufficient distinction to justify separate retention.

4.2 During vs. post pandemic differences in parent perceptions

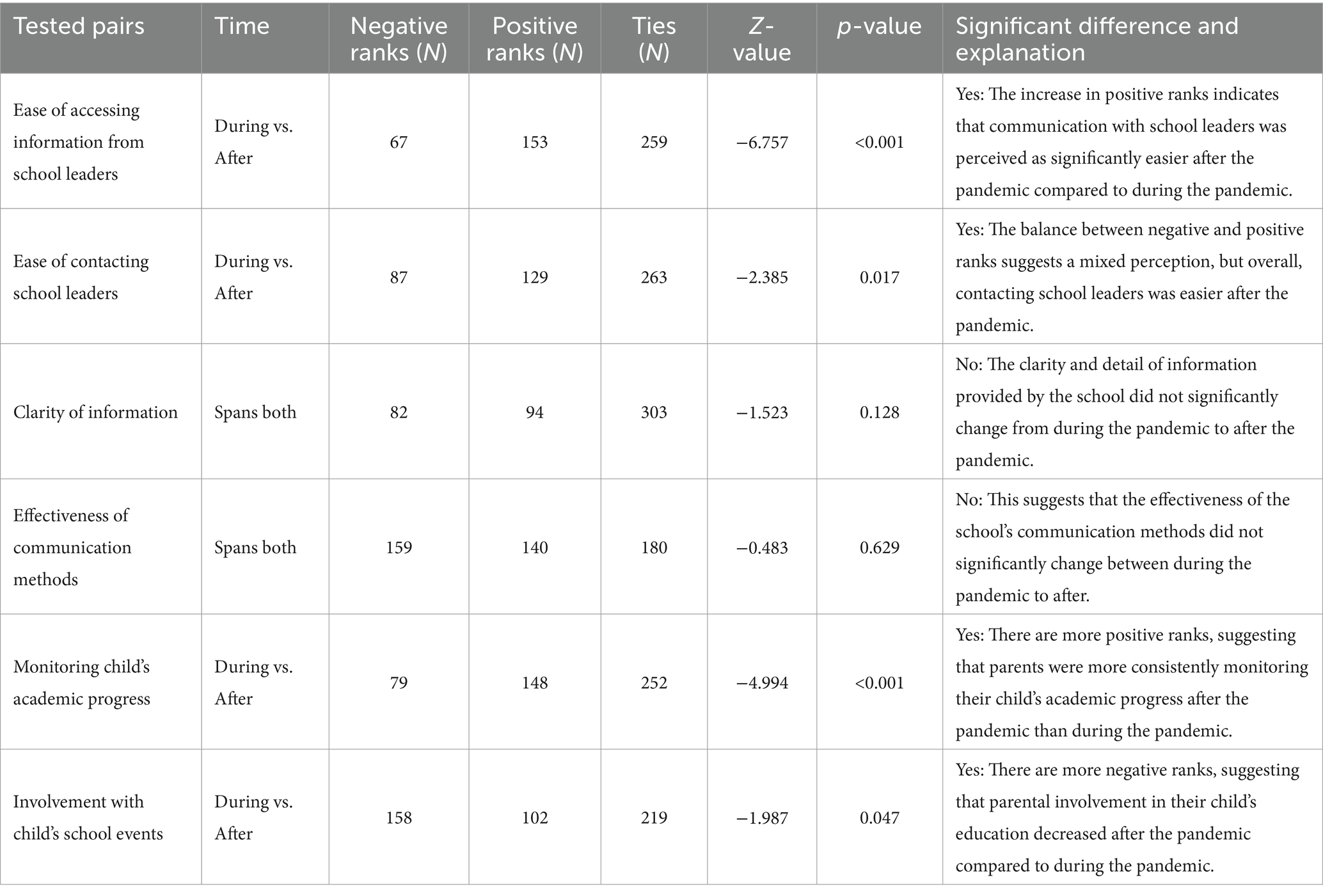

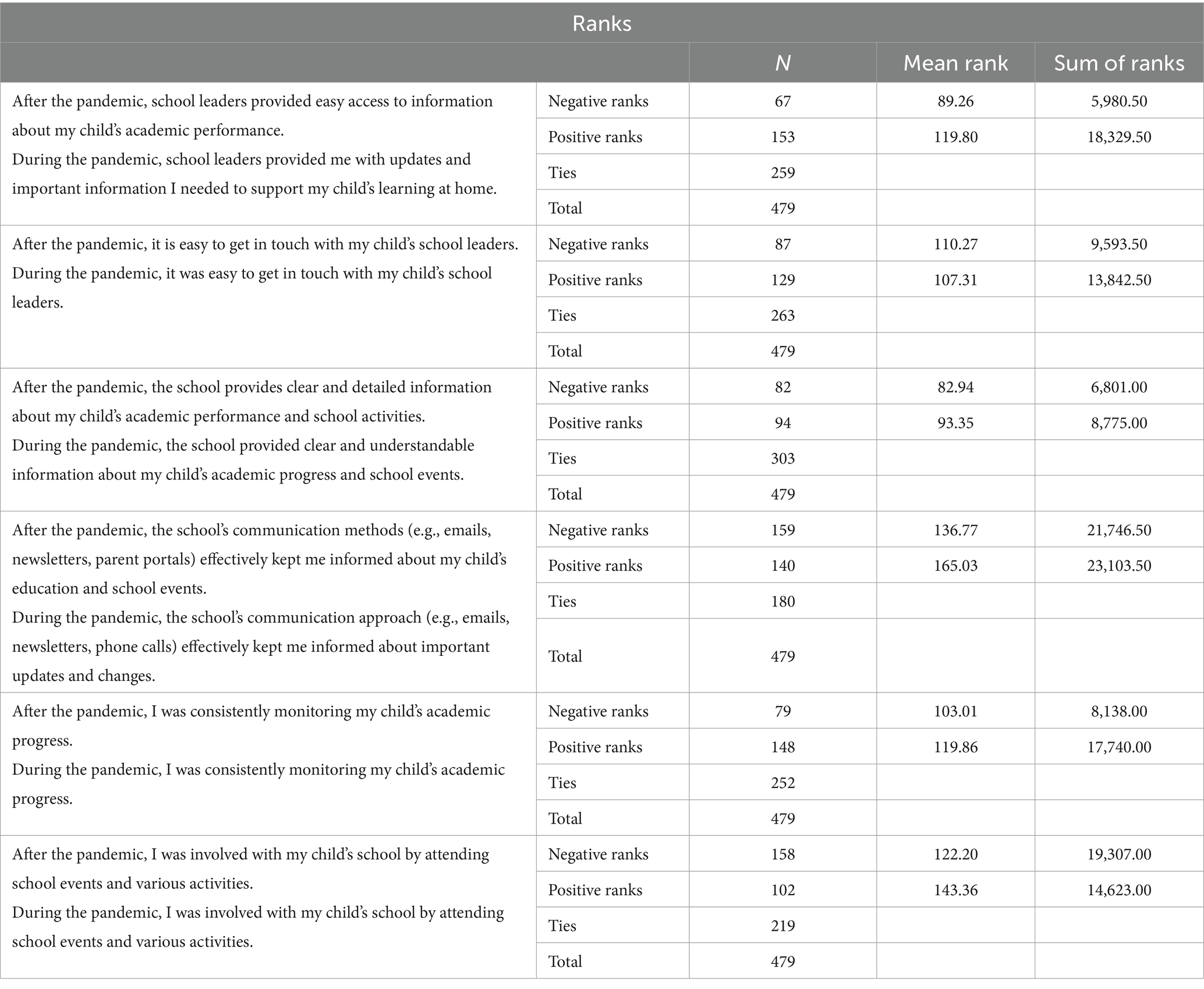

To identify whether there were significant changes in parental perceptions across the seven factors identified through the EFA, we used Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to compare paired observations for factors measured during and after the pandemic. Paired observations were drawn from the survey. Since the survey items were measured on a 4-point Likert scale, producing ordinal data, and given the paired nature of the observations (respondents provided perceptions at two different points in time), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was deemed appropriate for the analysis. This non-parametric test does not assume a normal distribution of the data and is suitable for detecting differences in the medians of paired samples (Laerd Statistics, 2020). This provides a meaningful method for us to compare the identified factors during and after the pandemic, ensuring that the findings are both statistically valid and pragmatically useful. A summary of tests is provided in the table below, which identifies the tested pairs, time frame (during vs. after the pandemic or continuous), ranks, Z-value, p-value, and significant differences (Tables 6, 7).

A distinction between ease of accessing information from school leaders and ease of contacting school leaders was made to capture several aspects of parental interaction. Ease of accessing information refers to how readily parents could obtain general information or updates from school leadership, while ease of contacting school leaders refers to the ability to engage directly with school personnel for specific questions or concerns. Both measures were included to distinguish between the availability of general information dissemination and the personal accessibility of school leaders for individual concerns.

Table 8 includes the resulting ranks for each set of tested pairs. Ranks denote the magnitude of differences in order, which assists researchers in evaluating the degree of variation between identified pairs. Signed ranks provide additional insight into those differences, categorizing them as either positive or negative. Using ranks is crucial, as it circumvents the assumption of normally distributed differences, which makes it a strong alternative to the paired t-test for non-normally distributed data. The tests compared responses on several items measured during and after the pandemic, as demonstrated in Table 9, which includes the Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistics.

4.3 Overview of tested pairs

The six tested pairs in the Wilcoxon signed-rank test align with the two overarching themes identified in the research questions: (1) Parent-School Communication and (2) Parental Involvement in Distance Learning. This alignment demonstrates how specific aspects of parent perceptions contribute to understanding the broader dynamics of communication and involvement during and after the pandemic.

Within the theme of Parent-School Communication, four tested pairs were identified. The first tested-pair reference ease of accessing information from school leaders. This reflects parents’ ability to receive general updates and information from school leadership during and after the pandemic. The significant increase post-pandemic indicates that schools successfully implemented accessible communication channels (like digital tools) that parents found effective. The second tested-pair considered the ease of contacting school leaders, which highlights parents’ ability to engage directly with school leadership to address specific concerns. The improvement post-pandemic demonstrates enhanced responsiveness, possibly due to streamlined communication methods or increased openness of school leaders to parental inquiries. Thirdly, we tested the clarity of information, which examines whether the information provided by schools was clear, concise, and easy to understand. The lack of significant change suggests that schools maintained consistent clarity during and after the pandemic. This stability may reflect effective pre-existing communication systems, but it also signals an opportunity for further enhancement to meet evolving parental expectations. The final tested-pair in this theme is the effectiveness of communication methods. This pair evaluates how communication tools (like emails, portals, messaging apps) meet parental needs. The absence of significant change implies that these tools remained effective throughout the pandemic but did not evolve substantially to address new challenges or opportunities.

Within the parental involvement in distance learning theme, there are two sets of tested pairs. The first set concerns monitoring a child’s academic progress, which reflects parents’ role in tracking their child’s learning outcomes. The increase post-pandemic highlights the sustained responsibility parents felt for academic oversight. This shift underscores the importance of schools providing parents with accessible performance metrics and guidance. The next pair we tested refers to involvement in their child’s school events, which measures parents’ participation in school activities. The observed decrease post-pandemic suggests that the return to in-person schooling posed logistical challenges for parents, reducing their ability to engage. This finding emphasizes the need for schools to offer flexible participation options, such as hybrid or asynchronous formats, to accommodate diverse parental schedules.

In summary, the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test reveal significant changes in various facets of school communication and parental involvement when comparing experiences during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Collectively, these results underscore improvements in specific areas of school communication but also indicate a decline in certain aspects of parental involvement. This suggests that schools should focus on these areas to maintain effective communication and support parental engagement.

4.4 Perceptions of parent-school communication

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered the educational landscape, driving schools to innovate and modify their communication tactics (Schleicher, 2020). This study found that these adjustments, on average, had a significant impact on how parents regarded their communication with schools. The findings indicate a notable shift in the accessibility and effectiveness of parent-school communication, implying that the pandemic triggered positive changes in several aspects of educational communication. These results align with the research conducted by Garbe et al. (2020), which, based on a sample of 122 parents, found that the pandemic necessitated responsive measures in schools’ communication strategies to better meet the needs of parents and families in distance learning environments. Parents and guardians require up-to-date communication from school leaders to make informed decisions regarding their child’s learning and, in the context of COVID-19, their child’s safety. In this regard, Kim and Asbury (2020), who interviewed 24 teachers from English state schools, found that effective communication between schools and parents was imperative in navigating the transition from on-ground to online learning. Similarly, Bocoş and Marin (2022) and De Muynck (2022) discovered that the pandemic fostered improved communication between parents and schools, with modern communication tools being perceived as effective in maintaining and even strengthening these relationships. The results of this study indicate that this trend was evident during the pandemic and has continued into the post-pandemic learning environment. Parents report that school leaders across the UAE became more accessible during COVID-19 and have maintained this accessibility and effectiveness in their communication approaches (Chatzipanagiotou and Katsarou, 2023; Harris and Jones, 2020; Netolicky, 2020). These findings align with those of other studies, although the number of studies in this area remains limited.

Parents experienced a substantial improvement in accessing information from school leaders and in contacting school leaders following the pandemic. These findings support the hypothesis which states that schools improved their communication practices, resulting in increased accessibility and transparency. Dong et al. (2020) surveyed 3,275 Chinese parents and found that they valued effective communication channels that alleviated the challenges prompted by distance learning. To better address communication challenges related to inconsistency and ambiguity, schools should articulate clear procedures for frequent and timely communication. It is essential to provide accurate information to all parents and guardians to promote confidence and engagement (Dong et al., 2020; Kim and Asbury, 2020). Houri et al. (2019) further highlight the importance of clear and consistent communication in establishing trust and engagement between parents and schools. Likewise, Hertel and Jude (2016) found that prompt and accurate information is critical for facilitating parental involvement and confidence within the school. Collectively, these findings reveal that parents and guardians valued the guidance and support they received from schools, emphasizing the importance of strong two-way communication between schools and parents/guardians (Bates et al., 2023).

However, several investigations dispute these conclusions. For example, Kim and Asbury (2020) describe how some parents did not experience improved communication, citing uncertainty and a lack of timely updates from schools. Furthermore, Borup et al. (2020) highlighted that certain schools struggled to maintain consistent communication, which led to parental frustration. Additionally, there was no significant change in the clarity and detail of the information presented nor in the effectiveness of communication strategies. Epstein et al. (2018) support this consistency, stating that established communication strategies can remain effective if they are well-structured and unambiguous. The EFA corroborated these findings by identifying specific characteristics associated with enhanced communication and sustained parental participation following the pandemic.

4.5 Perceptions of parental involvement

Parental participation and involvement in their children’s education are critical for student success; however, the COVID-19 pandemic posed unexpected challenges that altered these dynamics (Rehman et al., 2021). This study considered how perceptions of parental involvement and parent-school communication evolved during and after the pandemic, indicating shifts that mirror broader societal effects.

In terms of parental involvement, we found an increase in parental monitoring of their children’s academic progress post-pandemic, alongside a decrease in total parental involvement with schools. This confirms our hypothesis indicating a significant difference in parents’ perceptions of their involvement in their child’s education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The data demonstrate that as parents became increasingly concerned about their children’s academic progress post-pandemic, their overall involvement with their child’s school decreased. Distance learning may have facilitated greater parental involvement during the pandemic due to its accessibility; parents could attend events and activities online, which helped to alleviate scheduling conflicts. However, after the pandemic, as students returned to in-person schooling, many school events and activities resumed as well. This shift may have introduced additional challenges for parents in maintaining their involvement in school activities.

This finding aligns with the research conducted by Dong et al. (2020), which indicated that although parents were more focused on monitoring academic efforts, the stressors associated with the pandemic may have led to decreased overall involvement in their children’s education. Additionally, Ma et al. (2016) found that increased academic monitoring could occur at the expense of greater educational participation, particularly during times of crisis. This observation is supported by a meta-analysis of 46 studies that emphasized the importance of parental involvement in early childhood and elementary education. Sibley and Dearing (2014) reported that while parental participation is critical for children’s academic achievement, external stressors can impact the extent and nature of parental involvement. Garbe et al. (2020) also argue that increased parental stress and anxiety during the pandemic contributed to reduced involvement in their children’s schooling.

The mixed results of this study suggest that, while there was an overall trend of decreased parental involvement, these perceptions were not universally applicable. The data indicates that parental involvement during and after the pandemic varied significantly. These mixed perceptions are consistent with the findings of Knopik et al. (2021), who conducted a survey of 421 parents of primary school students. They observed that while some parents reported feeling stressed, others seized the pandemic as an opportunity to become more involved in their children’s education. Similarly, Bhamani et al. (2020), who interviewed 19 parents, found that the increased time spent at home allowed parents to engage more deeply in their children’s educational experiences, which contrasts with the overall trend of reduced involvement.

Collectively, the findings of this study highlight the necessity for schools to maintain improved communication strategies while establishing measures to involve parents more fully in their children’s education. This study lays the groundwork for schools to foster strong parent-school relationships that support student performance, addressing both the benefits and challenges observed during this transformative period (Garbe et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2016; Sibley and Dearing, 2014). Although parents increased their monitoring of their child’s academic progress after the pandemic, they simultaneously became less involved with their child’s school. These mixed results indicate that school leaders would benefit from a more nuanced approach to understanding and supporting parental involvement in educational settings.

5 Suggestions for future practice

The findings from this study provide meaningful insights into parent-school communication and parental involvement during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. While our analysis reveals positive trends in accessibility and engagement with digital tools, the results also identify areas requiring further exploration and clarification. The following suggestions aim to guide school leaders in enhancing both communication strategies and parental involvement practices based on emerging patterns observed in this research.

5.1 Continue use of diverse digital communication channels

The data revealed that digital communication tools, including school-parent portals, learning management systems (such as Google Classroom and Seesaw), and messaging platforms (such as WhatsApp and SMS notifications), were perceived positively by parents during the pandemic (Z = −6.757, p < 0.001). This suggests that employing multiple, varied channels of communication improved accessibility and streamlined information sharing. Diversifying communication pathways with a diverse set of tools can help ensure information reaches parents through multiple means. This may further help meet the varying needs and technological literacy levels of parents. As such, schools should also evaluate the effectiveness of their communication channels and be willing to adjust these based on the evolving needs and feedback from families.

5.2 Build clear procedures for timely communication

Additionally, our study finds no significant change in the clarity of communication during and after the pandemic. This stability suggests that even though systems were effective, such systems may remain unchanged. While this could be interpreted from either a positive or negative perspective, it is relevant to note that unchanged systems may not continue to meet the evolving needs of parents’ needs. As such, schools should consider establishing flexible procedures for message clarity, frequency, and content to enhance consistency across all phases of learning. It is essential to provide accurate information to all parents to retain their confidence and engagement. A study conducted by Borup et al. (2020) emphasizes the importance of timely updates in minimizing misunderstandings and promoting a healthy school environment. These practices should include shared expectations for response times, message formats, and multilingual support where necessary. Implementing clear communication policies and practices could further strengthen clarity and accessibility.

5.3 Strengthen parental support programs

The results of this study indicated a significant increase in parental monitoring of academic progress post-pandemic, with parents assuming greater responsibility for supporting their children’s education. However, the data also suggested that parents faced challenges in fully understanding progress metrics and using school-provided tools effectively. Toward this end, schools could deliver workshops and face-to-face information sessions. Developing additional resources, such as instructional videos and toolkits, to help parents interpret grading systems, access performance data, and provide academic support at home are additional valid suggested approaches. Where parental involvement remains a priority, additional resources could be an excellent way to empower parents to engage more effectively in their child’s learning journey at home.

5.4 Provide flexible engagement opportunities

Further, our analysis indicates a decrease in parental participation in school activities post-pandemic. This decline may reflect a return to pre-pandemic norms rather than a drop in engagement quality. While parents, and other education stakeholders, have returned to these norms, it remains prudent for schools to explore flexible involvement options for parents. Consistent with the research of Goodall (2022) and Epstein et al. (2018), schools could consider additional in-person, online, and hybrid engagement opportunities. Virtual check-ins with parents, with either synchronous or asynchronous opportunities for engagement, could further accommodate diverse parental schedules and sustain positive relationships. Parent feedback forums, coupled with flexible volunteer roles could further support meaningful engagement while respecting parents’ time constraints.

5.5 Evaluate and customize digital tools for effectiveness

While the findings highlighted increased accessibility through digital platforms, parents reported variations in their effectiveness. These mixed results demonstrate a need for schools to sustain greater consistency and long-term effectiveness. As such, schools could regularly evaluate these tools through parental feedback surveys and adapt strategies based on identified preferences and challenges. Such tools may require customization to promote access for diverse groups of parents. This may include including language accessibility features and differentiated content delivery to cater to various learning environments and technological proficiencies. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of adjusting approaches to strengthen parent-school communication, as successful digital platforms have been shown to have a substantial impact (Garbe et al., 2020).

5.6 Encourage collaborative decision-making

Our analysis showed that parental collaboration in decision-making was positively associated with stronger communication and trust. Parents who were engaged in decision-making regarding learning platforms and scheduling during the pandemic reported higher levels of trust and communication with school leaders. That is, collaborative approaches can promote long-term engagement and trust between schools and parents. As such, schools may benefit from implementing structured feedback mechanisms, which could include collaborations like parent advisory groups, parent town halls, and other open forums, to encourage ongoing parental input in school policies and communication strategies. Providing opportunities for shared decision-making fosters a sense of partnership and aligns with distributed leadership models (Erol and Turhan, 2018), which emphasize the significance of diverse stakeholder voices.

6 Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally transformed parent-school communication and parental involvement, resulting in both substantial progress and new challenges. This study highlights significant improvements in the accessibility and efficiency of interactions between parents and school leaders. In the post-pandemic landscape, enhanced digital communication strategies have facilitated parents’ ability to acquire communication and connect with school leaders, resulting in positive outcomes. Parental involvement, when compared to the periods during and after the pandemic, displayed a multifaceted pattern. Although parents became more attentive to their children’s academic success after the pandemic, there was a decrease in their total involvement in other educational activities. Ultimately, the pandemic has catalyzed positive transformation while also presenting significant challenges in educational communication and family involvement. To progress, schools should leverage the advancements made by further improving communication tactics and ensuring their consistent application. Additionally, schools could implement programs designed to fully support and involve parents in their children’s education. By engaging in these practices, educational institutions can establish robust parent-school collaborations, thereby bolstering student achievement in an increasingly complex and dynamic educational environment.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by AURAK Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We acknowledge that the term parents may also include guardians and caregivers; for simplicity, we have chosen to use the term parents inclusive of these roles.

References

Abuhammad, S. (2020). Barriers to distance learning during the COVID-19 outbreak: a qualitative review from parents’ perspective. Heliyon 6:e05482. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05482

Antipkina, I., and Ludlow, L. H. (2020). Parental involvement as a holistic concept using Rasch/Guttman scenario scales. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 38, 846–865. doi: 10.1177/0734282920903164

Bates, J., Finlay, J., and Bones, U. O. (2023). Education cannot cease: the experiences of parents of primary age children (age 4–11) in Northern Ireland during school closures due to COVID-19. Educ. Rev. 75, 657–679. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.1974821

Bhamani, S., Makhdoom, A. Z., Bharuchi, V., Ali, N., Kaleem, S., and Ahmed, D. (2020). Home learning in times of COVID: experiences of parents. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 7, 9–26. doi: 10.22555/joeed.v7i1.3260

Bocoş, M.-D., and Marin, D.-C. (2022). “Characteristics of parent-teacher communication in Romanian primary education during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of the parent and teacher opinions” in Basic communication and assessment prerequisites for the new Normal of education (IGI Global). Hershey, Pennsylvania; New York; Beijing, Chin.

Borup, J., Graham, C. R., and Davies, R. S. (2013). The nature of parental interactions in an online charter school. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 27, 40–55. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2013.754271

Borup, J., Graham, C. R., West, R. E., Archambault, L., and Spring, K. J. (2020). Academic communities of engagement: an expansive lens for examining support structures in blended and online learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 807–832. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x

Budiningsih, I., and Abdulrahman, T. (2022). Optimizing primary school students' parental involvement in online learning. Akademika 11, 173–189. doi: 10.34005/akademika.v11i01.1841

Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., and Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

Chatzipanagiotou, P., and Katsarou, E. (2023). Crisis management, school leadership in disruptive times and the recovery of schools in the post COVID-19 era: a systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 13:118. doi: 10.3390/educsci13020118

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., and Wang, L. C. (2024). Correction to: reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: a review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 41, 745–783. doi: 10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

De Muynck, B. (2022). The impact of the pandemic on the school-family relationship. Int. J. Christ. Educ. 26, 3–5. doi: 10.1177/20569971211069295

Dong, C., Cao, S., and Li, H. (2020). Young Children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 118:105440. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440

Eccles, J. S., and Harold, R. D. (2013). “Family involvement in children’s and adolescents’ schooling” in Family-school links (New York: Routledge).3–34.

Epstein, J. L. (1987). Toward a theory of family-school connections: teacher practices and parent involvement. Soc. Intervent. Potent. Constr. 121:136. doi: 10.1515/9783110850963.121

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. S., and Jansorn, N. B. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Erol, Y. C., and Turhan, M. (2018). The relationship between distributed leadership and family involvement from parents’ perspective. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 18, 525–540. doi: 10.12738/estp.2018.3.0088

Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., and Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. Am. J. Qual. Res. 4, 45–65. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/8471

Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R., Willems, P. P., Powers, J. R., and Musgrove, A. T. (2022). Parental involvement in supporting students’ digital learning. Educ. Psychol. 57, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2022.2129647

Goodall, J. (2022). A framework for family engagement: going beyond the Epstein framework. Wales J. Educ. 24, 75–96. doi: 10.16922/wje.24.2.5

Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Haritha, B., and Praseeda, C. (2021). Online learning in pandemic—an analysis of parental perspective. Ymer 20, 733–747. doi: 10.37896/ymer20.12/67

Harris, A., and Jones, M. (2020). COVID 19–school leadership in disruptive times. School Leadersh. Manag. 40, 243–247. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1811479

Hertel, S., and Jude, N. (2016). “Parental support and involvement in school” in Assessing contexts of learning: an international perspective, Springer, Cham. 209–225.

Hill, N. E., and Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: a Meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Dev. Psychol. 45, 740–763. doi: 10.1037/a0015362

Houri, A. K., Thayer, A. J., and Cook, C. R. (2019). Targeting parent trust to enhance engagement in a school–home communication system: a double-blind experiment of a parental wise feedback intervention. School Psychol. 34, 421–432. doi: 10.1037/spq0000318

Hurley, K. D., Lambert, M. C., January, S.-A. A., and D’Angelo, J. H. (2017). Confirmatory factor analyses comparing parental involvement frameworks with secondary students. Psychol. Sch. Springer, Cham. 54, 947–964. doi: 10.1002/pits.22039

Kamrani, Z., Tajeddin, Z., and Alemi, M. (2024). Scaffolding principles of content-based science instruction in an international elementary school. Pedag. Int. J. 19, 257–281. doi: 10.1080/1554480X.2023.2222716

Kim, L. E., and Asbury, K. (2020). Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: the impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12381

Knopik, T., Błaszczak, A., Maksymiuk, R., and Oszwa, U. (2021). Parental involvement in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic—dominant approaches and their diverse implications. Eur. J. Educ. 56, 623–640. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12474

Kock, N. (2017). “Common method bias: a full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM” in Partial least squares path modeling: basic concepts, methodological issues and applications, Springer, Cham. 245–257.

Laerd Statistics. (2020). Wilcoxon signed rank test in SPSS statistics. Available at: https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/wilcoxon-signed-rank-test-using-spss-statistics.php (Accessed April 20,2024).

Lareau, A. (2019). “Parent involvement in schooling: a dissenting view” in School, family, and community interaction. (New York: Routledge).

Levy, R. (2024). Home–school communication: what we have learned from the pandemic. Education 3–13 52, 21–32. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2023.2186972

Li, L., Liu, X., and Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2024). Parental involvement in online education during COVID-19 lockdown: a netnographic case study of Chinese language teaching in the UK. Multilingua 43, 241–266. doi: 10.1515/multi-2023-0007

Lu, S. (2020). School+ family community learning model of PE course under COVID-19 epidemic situation. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 15, 218–233. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i18.16439

Lynn, M. R. (1986). “Determination and quantification of content validity.” Nursing research, 35, 382–386. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198611000-00017

Ma, X., Shen, J., Krenn, H. Y., Shanshan, H., and Yuan, J. (2016). A meta-analysis of the relationship between learning outcomes and parental involvement during early childhood education and early elementary education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 771–801. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9351-1

Mapp, K. L., and Kuttner, P. J. (2013). Partners in education: a dual capacity-building framework for family-school partnerships. Sedl, 3–27.

Mehmood, T. (2024). Investigating effective communication strategies employed by school principals to convey the significance of climate change education to students, staff, and parents. EdArXiv. doi: 10.35542/osf.io/qzagb

Ministry of Education. (2024). Open Data, Ministry of Education, United Arab Emirates. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.ae/En/OpenData/Pages/home.aspx (Accessed June 20, 2024).

Moore, M. G. (2013). “The theory of transactional distance” in Handbook of distance education: Second edition (New York: Routledge).

Muir, T., Muir, B., Hicks, D., Beasy, K., and Murphy, C. (2024). Learning from home during COVID-19: primary school parents’ perceptions of their school’s management of the home-learning situation. Cogent Educ. 11:2308414. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2308414

Netolicky, D. M. (2020). School leadership during a pandemic: navigating tensions. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 5, 391–395. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-05-2020-0017

Omarkhanova, A., Sugiralina, A., and Yesbergen, N. (2024). Investigating the impact of parental involvement on student academic achievement. Sci. Pedag. J. 109, 43–52. doi: 10.59941/2960-0642-2024-2-43-52

Pasikowski, S. (2023). Snowball sampling and its non-trivial nature. Przegląd Badań Edukacyjnych (Educ. Stud. Rev.) 2, 105–120. doi: 10.12775/PBE.2023.030

Rehman, S., Smith, K. G., and Poobalan, A. (2021). Parental experiences of education at home during a pandemic. Educ. North 28, 3–16. doi: 10.26203/frrg-xz45

Roy, A. K., Breaux, R., Sciberras, E., Patel, P., Ferrara, E., Shroff, D. M., et al. (2022). A preliminary examination of key strategies, challenges, and benefits of remote learning expressed by parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. School Psychol. 37, 147–159. doi: 10.1037/spq0000465

Sacks, D., Bayles, K., Taggart, A., and Noble, S. (2020). COVID-19 and education: how Australian schools are responding and what happens next. PwC Australia.

Schleicher, A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on education: insights from “education at a glance 2020”. OECD Publishing, 3–26.

Sibley, E., and Dearing, E. (2014). Family educational involvement and child achievement in early elementary School for American-Born and Immigrant Families. Psychol. Sch. 51, 814–831. doi: 10.1002/pits.21784

Teh, W. L., Abdin, E., Asharani, P. V., Kumar, F. D. S., Roystonn, K., Wang, P., et al. (2023). Measuring social desirability bias in a multi-ethnic cohort sample: its relationship with self-reported physical activity, dietary habits, and factor structure. BMC Public Health 23:415. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15309-3

Theodoros, E., Christini, B., Evaggelia, K., Andromachi, K., and Calliope, T. (2022). Communicative relations in the educational environment: exploration of parents’ views on communicative relations with the school principal. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 29, 61–76. doi: 10.9734/ajess/2022/v29i330702

UNESCO Global Education Coalition. (2020). “Education: From Disruption to Recovery.” United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization: UNESCO.

Watkins, M. W. A. (2021). Step-by-step guide to exploratory factor analysis with SPSS. New York: Routledge.

Yang, D., Chen, P., Wang, K., Li, Z., Zhang, C., and Huang, R. (2023). Parental involvement and student engagement: a review of the literature. Sustain. For. 15:5859. doi: 10.3390/su15075859

Keywords: parent-school communication, educational leadership, parental involvement, COVID-19, online learning environments

Citation: Proff A, Musalam R and Matar F (2025) Lessons learned for leaders: implications for parent-school communication in post-pandemic learning environments. Front. Educ. 10:1496319. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1496319

Edited by:

Casey Cobb, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Ana Isabel González Herrera, University of La Laguna, SpainWilliam Ruff, Montana State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Proff, Musalam and Matar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandria Proff, YWxleGFuZHJpYS5wcm9mZkBhdXJhay5hYy5hZQ==

Alexandria Proff

Alexandria Proff Rasha Musalam

Rasha Musalam Faten Matar

Faten Matar