- Department of Pedagogical Studies, School of Education, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Transformation of folk culture is unavoidable when aiming to make traditional elements relevant to children today. An educational event was planned during a semester based on the above assumption, as a collaboration between the Department of Education of the University of Nicosia, Cyprus, and the Cyprus Folk Art Museum. The context of activities of two undergraduate courses was modified to make museum exhibits relevant initially to 11 student–teachers and later to 20 preschool children invited at the end of the semester to participate in activities at the museum. The student–teachers’ instructional design process was based on strategies followed by artists who pursue meaningful artmaking. These strategies—stages—include identifying and personalizing a big idea, building a knowledge base, setting boundaries, and problem-solving. Whether with a small or large deviation from the initial folk cultural experience, all participants were actively involved in activities, which were inspired by tradition and evolved to transition and transformation for an educational event.

1 Introduction

Folk culture bears witness to the cultural identity of each community with the influences it has received over time. Traditions are passed down from generation to generation and are adapted according to the needs, environment, and history of each community. Folk culture is a broad term that includes oral narratives and stories, anecdotes, music, movement and dance, beliefs, customs, and traditions, as well as material culture such as cooking, hairstyles, clothing, and crafts. Folk culture includes fundamental components that shape our society, as different components from tradition seem to endure and shape how individuals perceive the world today (Michalopoulos and Xue, 2021). The wide-ranging and flexible nature of folk culture allows it to be a rich and dynamic tool for preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge across time and space. Traditional stories, songs, customs, myths, and artifacts convey history, moral lessons, cultural identity, and entertainment.

Folk culture can adapt to different contexts and generations. For any form of expression to endure, it must undergo adaptation in alignment with the evolving demands and contextual shifts of its historical and cultural period. This process of transformation ensures that the expression remains relevant and resonant within contemporary societal frameworks, allowing it to persist across generations. Without such modification, the expression risks obsolescence as it may no longer reflect the values, norms, or expectations of its audience. A focused examination of the folk art of Cyprus over time, for example, reveals a clear evolution from the stable forms, characteristic of the past, to contemporary modifications in materials and shapes. For instance, a modern embroiderer is now tasked with the application of traditional patterns onto pink fabric, a trend that reflects current market demands but was uncommon in earlier periods. This shift underscores the dynamic nature of folk art and its responsiveness to changing esthetic preferences and cultural contexts.

Changes in traditional elements are inevitable, affecting materials, themes, and functionality (Alter-Muri and Klein, 2007). For instance, grandmothers traditionally crafted tablecloths using crochet techniques, while mothers began to draw inspiration from patterns found in foreign magazines. With advancements in technology and scientific progress, alongside broader social reforms that redefine the concept of art, institutions such as the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, have incorporated contemporary works, including a crochet-embroidered chair by Dutch designer Wanders (1963), into their collections. This evolution from past practices to present expressions of folk art indicates a trajectory that allows for further development and transformation in the future. Shifts in materials and sources of inspiration reflect broader societal changes. The inclusion of contemporary pieces in established art institutions signifies a redefinition of what constitutes art, showcasing the ongoing dialog between tradition and modernity. This dynamic interplay not only marks a departure from historical practices but also opens avenues for continued innovation and evolution within the folk art tradition.

The utilization in education of the evolutionary trajectory of folk art and all forms of expression is a prerequisite for the teacher’s efforts to develop situated learning. Situated learning is a teaching approach developed in the early 1990s by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger following the philosophy of Dewey, Vygotsky, and others. According to this approach, students actively participate in the learning process when it is situated in real-life activities (Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, 2012). Engaging children in the artistic process requires exploring and understanding artistic heritage while connecting it to the present. Consequently, the objective of educators pursuing situated learning for their students is to curate experiences that are both connected to cultural traditions and relevant to children’s contemporary lives. This approach aims to establish a meaningful connection to the past while simultaneously fostering the development of creative thinking skills. By integrating traditional elements into the learning process, educators can encourage students to draw on historical context as a foundation for innovation and personal expression. The integration of folk art and folklore into educational curricula is applicable across various subject areas and age groups. This approach facilitates a deeper exploration of personal identity among students while emphasizing the significance of cultural diversity. By engaging with forms of folk art, students gain insights into the relationship between local culture and its historical roots, as well as its contemporary relevance and potential for future evolution. This pedagogical strategy not only enriches students’ understanding of their cultural heritage but also encourages critical thinking about its ongoing transformation.

Comparable findings are illustrated in the study of Sanjaya et al. (2021), which explored the implementation of Balinese folklore-based civic education as a means of strengthening character education. Their results highlight how localized cultural narratives can serve as powerful pedagogical tools that connect heritage with contemporary educational goals while fostering values, identity, and critical engagement among learners. Importantly, the study demonstrates that folklore, when situated within an educational framework, does not simply transmit cultural knowledge but also functions as a medium for developing moral reasoning, social responsibility, and intercultural understanding. This aligns with the present study’s focus on Cypriot folk art as both an evolving cultural practice and a pedagogical resource, emphasizing its potential to bridge the gap between tradition and the lived realities of children. By establishing these connections, the study reinforces the argument that folk culture, whether in Southeast Asia or the Mediterranean, possesses a universal capacity to mediate between heritage and modernity. At the same time, it highlights the responsibility of educators and cultural institutions to critically design learning environments, such as museum programs, that not only preserve but also reinterpret traditions in ways that are meaningful for contemporary learners. In this regard, the convergence of tradition, transition, and transformation emerges as a crucial framework for understanding the educational significance of folk art and museum contexts. It underscores how traditional cultural expressions are not static relics of the past but living practices that undergo reinterpretation to remain relevant across generations. This perspective provides the conceptual foundation for the present study, which investigates how the dynamic interplay between heritage and innovation can be operationalized within museum-based educational activities designed for young children.

Taken together, these studies affirm the educational value of folk art and folklore, particularly when mediated through situated learning and museum contexts. However, a critical gap remains. While existing research highlights the significance of integrating cultural narratives into pedagogy, few investigations provide practical case studies that demonstrate how this integration can be systematically enacted through an instructional design model in early childhood settings. Addressing this gap, the present study offers an applied example within a Cypriot folk art museum, aiming to bridge theory and practice by operationalizing heritage-based, situated learning for preschool-aged children. In this regard, the convergence of tradition, transition, and transformation holds significant influence over current educational approaches, particularly in relation to folk art and museum contexts. To enhance students’ comprehension of the cultural diversity, historical development, and social relevance of folk art, educators aim to cultivate genuine engagement and appreciation for these forms of artistic expression. Within the paradigm of critical museology, museums are increasingly reassessing their societal roles, redefining themselves as interactive spaces for knowledge sharing and participatory engagement that link traditional practices with contemporary experiences (Mörsch et al., 2017). This evolution signifies a broader reimagining of the museum—from a static guardian of heritage to an active platform for cultural dialog. Consequently, museum education must undergo continual transformation, emerging as an independent, critically reflective practice that interrogates, reconfigures, and enriches both curatorial content and institutional frameworks to support meaningful, inclusive learning experiences for diverse audiences (Mayer, 2005). Building on this trajectory of transformation, Jeffery (2022) proposed an iterative and practice-oriented approach to museology that challenges conventional norms and opens up new avenues for fostering visitor agency. This reorientation, conceptualized as a situated turn in museum practice, foregrounds the recognition of individuals as complex, socially and ecologically embedded beings. Central to this perspective is the dynamic and reciprocal relationship between intangible cultural heritage embodied in personal narratives and lived experiences, and the museum’s foundational function of collecting. By emphasizing this dialectical interplay, Jeffery (2022) advanced a model of museological engagement that not only disrupts traditional hierarchies of knowledge but also repositions the museum as a participatory space where diverse forms of heritage are actively negotiated and co-constructed.

Mayo (2013) contended that museums, much like formal educational curricula, function as authoritative sites of cultural production, conferring legitimacy upon specific forms of knowledge and expression. In doing so, they participate in the construction of official knowledge and are inherently entangled in the politics of representation and power. Grounded in the principles of critical pedagogy, Mayo’s approach emphasizes the political dimensions of education, advocating for a mode of learning that interrogates power relations, challenges dominant narratives, and promotes transformative engagement. Within this framework, museums are not neutral spaces but are understood as active participants in shaping cultural and educational discourse, thereby reinforcing or potentially disrupting hegemonic structures of knowledge and meaning. Building on this view of museums as contested yet potentially transformative spaces, Huhn and Anderson (2021) proposed that museums possess the capacity to foster environments where visitors are invited to transcend conventional boundaries of identity and belonging, engage in intercultural dialog, and participate in difficult yet necessary conversations. These experiences can prompt critical reflection on the ethical dimensions of everyday life, positioning the museum as a site of critical pedagogy where visitors are encouraged to renegotiate meaning and question dominant cultural narratives. This transformative potential is partly grounded in the public’s perception of museums as trustworthy institutions and sources of credible knowledge, which contributes to their ability to provide safe, supportive contexts for reflective and meaningful engagement. However, as Lynch (2020) argued, realizing this potential requires a fundamental shift in practice, from simply involving communities to actively empowering them. This involves recognizing community partners as co-creators rather than passive recipients, sharing intellectual authority, and intentionally building strategies that support mutual capacity-building and sustained, equitable collaboration.

Yates et al. (2022) investigated young children’s engagement, participation, and inclusion in a city museum through the use of observational methods and semi-structured interviews with both children and their families. The findings indicated a shared desire among participants for more interactive exhibits, multisensory experiences, hands-on activities, and opportunities for imaginative role play. The authors contended that museums should conceptualize children primarily as experiential participants rather than solely as learners. They further advocated for enhancing the visibility of children’s identities within museum spaces and creating opportunities for responses that are meaningfully connected to children’s contemporary lives. The study concludes by emphasizing the importance of museums developing initiatives and creative programs that actively link children’s everyday experiences with their cultural identities.

Løvlie et al. (2021) presented a representative case that highlights innovative design strategies and emerging challenges aimed at facilitating content co-creation within museum contexts. The authors stressed the importance of not only promoting interpersonal connection among visitors but also deepening their engagement with the museum environment. By encouraging active participation and providing opportunities for personal interpretation, educational tools can support a more relational and meaning-centered approach to museum experiences. This design paradigm underscores the shift toward participatory cultural practices that prioritize visitor agency, emotional resonance, and collaborative meaning-making.

To enhance students’ comprehension of the diversity, significance, evolution, and social functions of folk art forms, educators aim to cultivate a genuine interest in these artistic expressions. This approach transcends the mere provision of encyclopedic knowledge about traditions; it emphasizes elements that promote a deeper understanding of the discourse surrounding folk art and the processes involved in its creation. Central to this pedagogical strategy is the establishment of conditions that foster and sustain dialog, wherein the educator actively participates. This dialog encompasses not only the intentions of the artist and the formal characteristics of the work but also its contemporary relevance. The process of “updating” folk art involves the teacher curating projects and activities that are authentically pertinent to the students’ lives. Such initiatives serve to activate and expand their perspectives, stimulate inquiry, and connect to their personal experiences, ultimately becoming catalysts for individual expression and collective creativity in educational contexts. In alignment with this pedagogical orientation, a curriculum design study was conceived to support early childhood education student–teachers in the development of meaningful educational activities tailored to preschool-aged children within the context of a folk art museum. The study aimed to operationalize these principles by guiding future educators in creating learning experiences that bridge cultural heritage with contemporary relevance, fostering both personal engagement and creative exploration.

2 Methodology

A collaborative initiative involving the UNESCO Chair at the University of Nicosia, the Department of Pedagogical Studies, and the Cyprus Folk Art Museum was undertaken to explore whether the creative process used by contemporary artists to produce personally meaningful artwork (Walker, 2001) could inform and enhance meaningful instructional design for both educators and learners. Specifically, the instructors of two undergraduate courses (Planning Activities for Early Childhood and Visual Arts Education) structured their curricula around the organization and implementation of an educational event centered on the museum’s exhibits. The 11 students enrolled in the preschool education program and participating in these courses were guided in the development of educational activities that were not only relevant and meaningful to their own experiences but also developmentally appropriate for preschool children. These activities culminated in an event held at the Cyprus Folk Art Museum, where 20 preschool children from a local early childhood center were invited to participate. The Cyprus Folk Art Museum provided a rich and authentic context for this initiative. It was founded by the Society of Cypriot Studies in 1937 and is housed in the premises of the Old Archbishop’s Palace, which was formerly a monastery. In the central section of the ground floor, glass display cases exhibit artifacts crafted by Asia Minor immigrants from the 1920s, including intricately detailed silverware and elaborately embroidered lace. Opposite the central display, smaller, distinct areas showcase a particularly intriguing juxtaposition of household items from various regions, representing diverse aspects of daily life. These include examples of weaving, pottery, embroidery, metalwork, woodcarving, basketry, leatherwork, folk painting, and traditional costumes, as well as agricultural tools, weaving instruments, and everyday objects such as a water well pulley, all coexisting within the exhibition space. This curated arrangement highlights the richness of old traditions, material culture, and the multifunctional nature of folk art in everyday Cypriot life, serving as both a resource and inspiration for the student–teachers’ instructional designs. Engagement of both student–teachers and children was documented and analyzed to support description of the instructional design and reflective evaluation. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Education of the University of Nicosia. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participating student–teachers and by the legal guardians of the preschool children.

The study sought to guide 11 female third-year early childhood student–teachers in designing pedagogical experiences that are developmentally meaningful to 20 preschool children from a local early childhood center, with the broader objective of bridging traditional cultural heritage with contemporary life. The investigation was guided by the following research questions:

1. How can the stages involved in producing personally meaningful artwork be applied to the design of museum education activities for preschool children?

2. What forms of participation and types of interaction can young children develop during experiential activities in a museum context?

A qualitative research methodology was employed to enable an in-depth exploration and practical examination of educational strategies and pedagogical techniques utilized by prospective early childhood educators in introducing young children to the Cyprus Folk Art Museum. The qualitative approach was selected for its capacity to facilitate interpretive understanding of educational phenomena from the perspectives of participants, thus offering insights into the evolving relationship between personal pedagogical practice and the formation of professional identity (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). Furthermore, the complexity and context-specific nature of pedagogical design and experiential learning, rooted in both cultural engagement and personal experience, render quantitative approaches insufficient for capturing the full depth of the phenomena under study (Creswell, 2011). The case study design allowed for a detailed, context-rich, and multidimensional documentation of the planning, implementation, and interactive processes between the student–teachers and between them and preschool children within the museum environment in which the study was conducted.

To design developmentally appropriate and meaningful activities for preschool children and for themselves at the Cyprus Folk Art Museum, participating student–teachers were guided to adopt the Stages of Meaningful Artmaking as articulated by Walker (2001). These stages, derived from the practices of professional artists, provided a structured yet flexible framework for fostering depth and personal relevance in creative work. The stages included (1) Definition and Individualization of a Big Idea/Theme, in which artists identify a clear and personalized theme as a conceptual focus underpinning the creative process; (2) Building a Knowledge Base, emphasizing the acquisition of contextual and thematic information to inform and enrich artistic production; (3) Problem-Solving and Delimitation, wherein artists critically define the parameters of their creative work, navigate constraints, set boundaries and limitations, and address potential challenges that arise during the process of creative production. These stages were explicitly integrated into the Visual Arts Education course, where student–teachers were encouraged to engage with the artistic process as creators, exploring the overarching theme of personal identity within a community context.

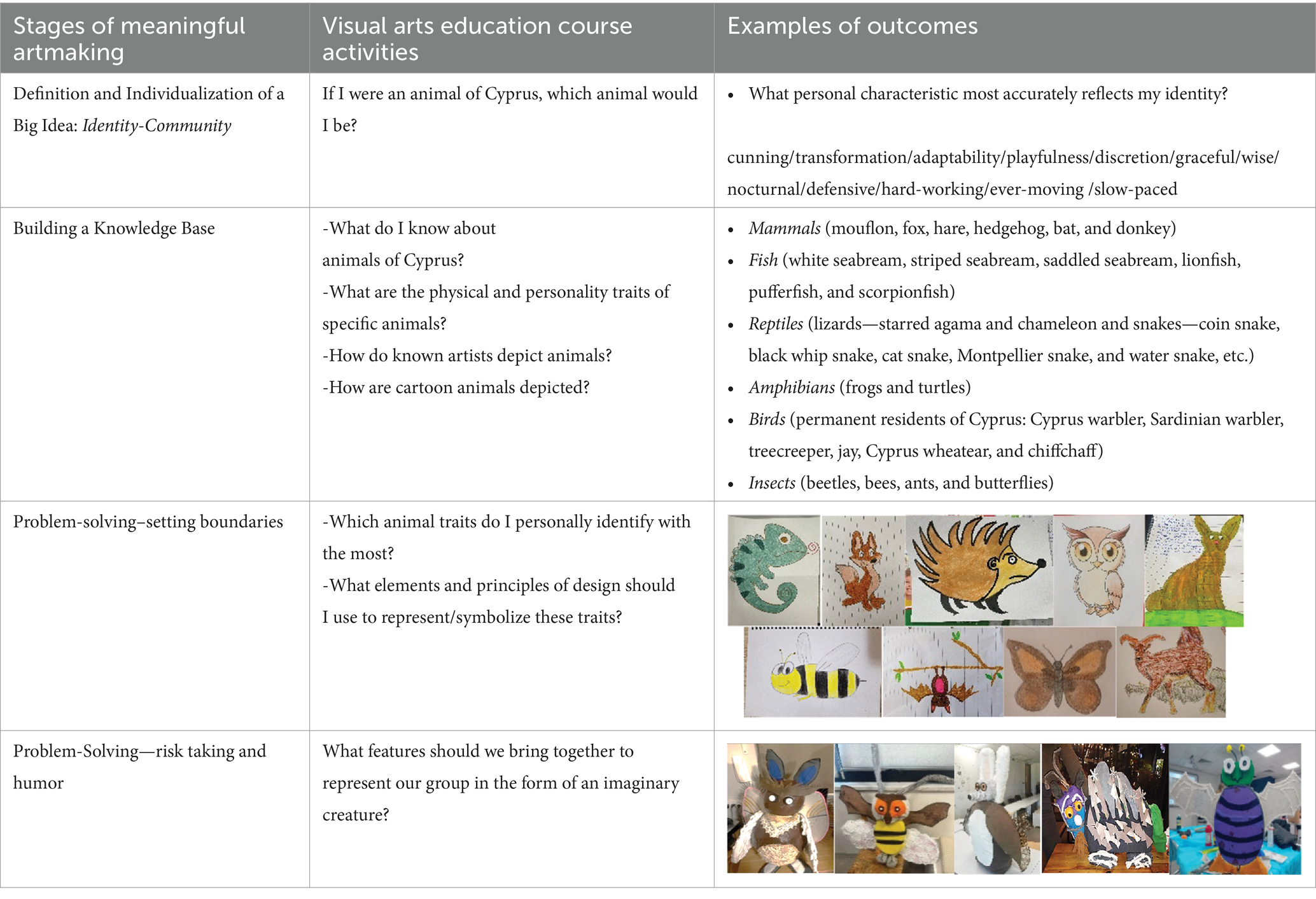

Table 1 outlines how these stages of meaningful creative production guided the modification of the context of the Visual Arts Education course activities. Within the framework of the Visual Arts Education course, the students were guided to function as artists, engaging deeply with the creative process and exploring the big idea of personal identity in a community. During the Visual Arts Education course, the primary objective was to support student–teachers in the creation of artwork in accordance with Walker’s stages of meaningful artmaking. While the overarching themes were predetermined by the instructors and remained consistent with those used in previous semesters, the specific subject matter of the student–teachers’ artwork was, initially, individually defined and, in later activities, negotiated in small groups. The subject matter of an artwork refers to tangible or recognizable elements, such as figures, objects, settings, or events that the viewer can identify, while the general theme or big idea represents the broader conceptual framework or message the artist seeks to convey. In the Visual Arts Education course, instructors established consistent big ideas across the semester to support thematic cohesion related to identity while allowing student–teachers to independently, or in small groups, define their subject matter in response to personal experiences or related coursework. Student–teachers posted their artwork and written descriptions and explanations of the process on the course platform. Artwork was examined based on their visual characteristics and the predefined criteria, according to the focus of each activity, such as visual elements and principles of design (color, line, unity, emphasis, perspective, and pattern), in relation to the symbolism as described by the student–teachers. Student–teachers’ reflections were further analyzed to assess the alignment between the chosen subject matter and the intended thematic framework. The creative exploration based on Walker’s model unfolded progressively from the second to the fifth week of the semester, serving as a foundational phase that informed the subsequent design of education activities for the preschool children in the museum setting for the end of the semester.

Table 1. Modifying Visual Arts Education course activities’ context for supporting planning meaningful folk art activities.

In the Planning of Activities in Early Childhood Education course, instructors developed a parallel pedagogical approach to that used in the Visual Arts Education course, guiding student–teachers toward adapting the mindset of the reflective practitioner and artist-educator to the context of early childhood curriculum design. Their objective was to create lesson plans and experiential learning activities capable of capturing preschool children’s interest and imagination while also encouraging them to move beyond passive or routine modes of museum engagement.

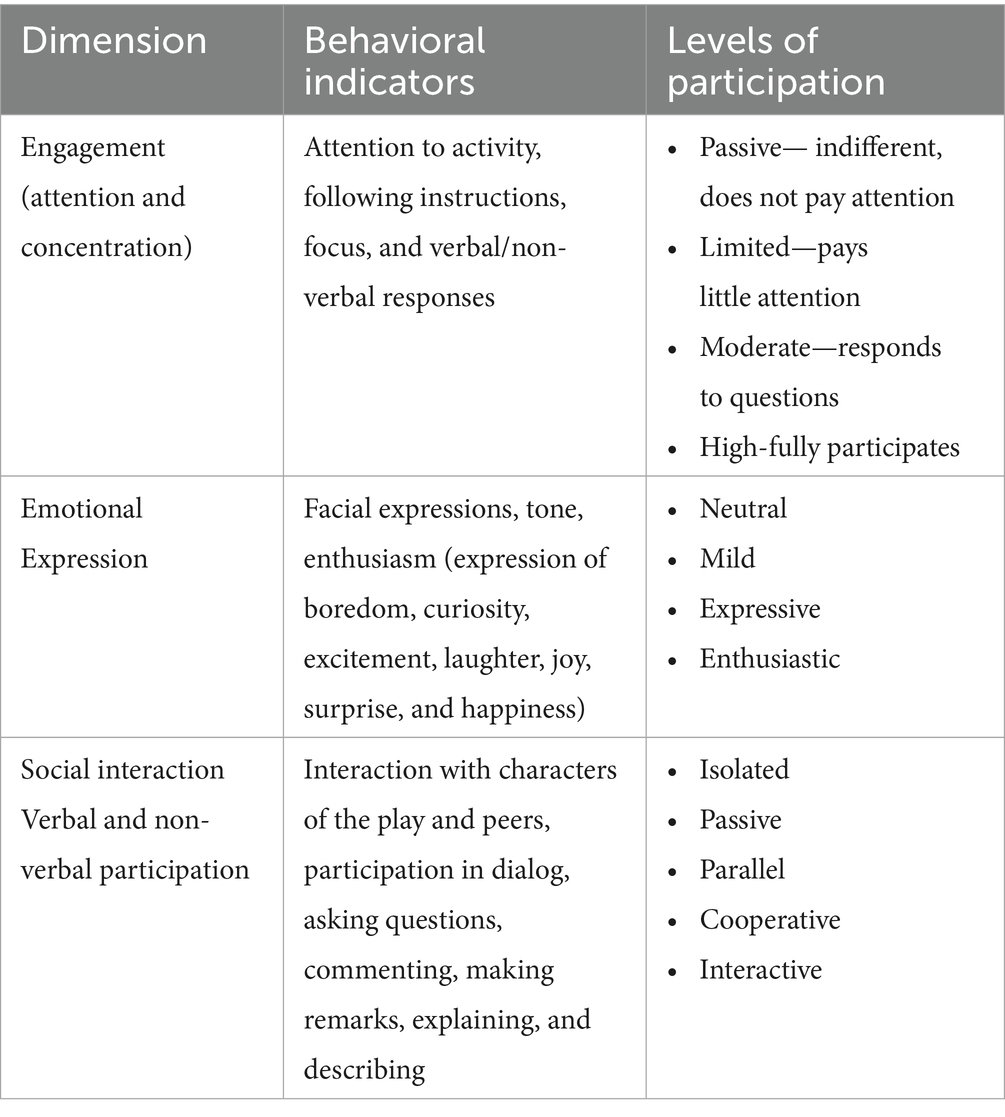

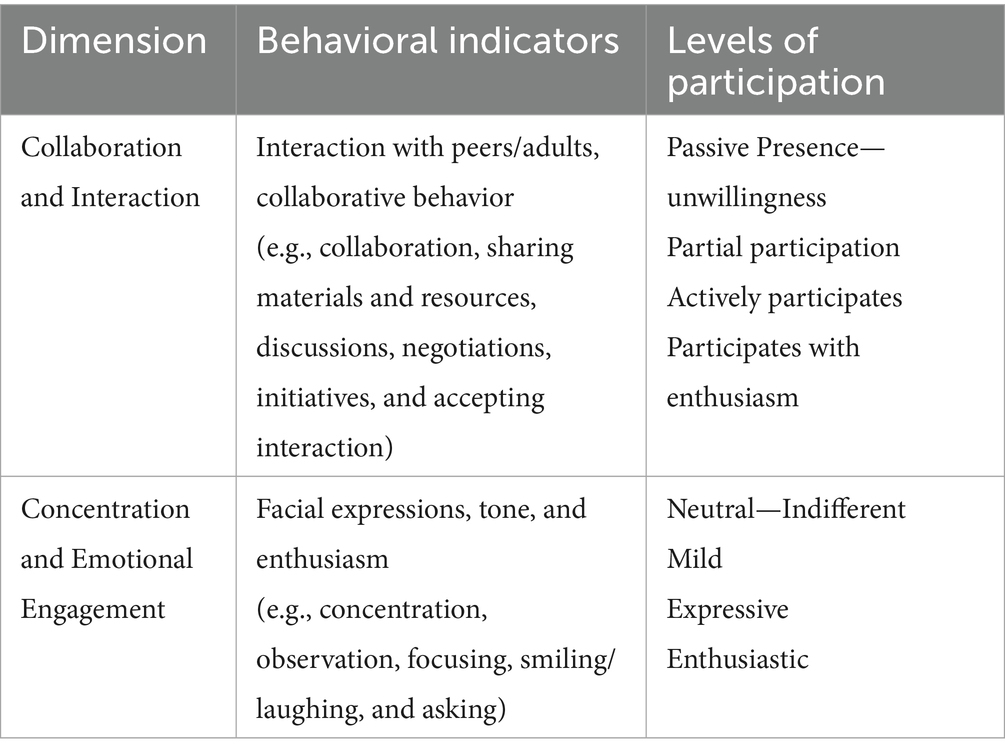

The museum-based activities were specifically designed to stimulate curiosity, agency, and meaningful interaction with selected exhibits in the Cyprus Folk Art Museum, fostering connections between traditional cultural artifacts and children’s contemporary lived experiences. Throughout the course, student–teachers engaged in iterative cycles of planning, implementation, and reflection. Their collaborative interactions, classroom discussions, and design processes were systematically observed and documented by course instructors. Observational data were supplemented by audio recordings and transcripts, enabling a detailed analysis of how student–teachers negotiated pedagogical decisions, incorporated folk cultural content, and responded to perceived developmental needs of preschool learners. Tables 2 and 3 present the observation indicators and criteria utilized by the instructors and the student–teachers to document children’s levels of engagement and responses during the dramatized storytelling session and the subsequent museum-based activities inspired by it, respectively. The rubric for documenting young children’s participation in museum activities was created based on literature exploring how young children perceive and engage in museum experiences (Piscitelli and Anderson, 2001) and discussing observational research approaches for studying young children’s participation, Einarsdottir (2007). Children’s participation during the museum event was systematically documented and analyzed to examine the nature and quality of their interactions with both peers and student–teachers, with the aim of identifying the degree and types of engagement exhibited during the educational activities. Particular attention was paid to verbal and non-verbal forms of interaction, collaborative behavior, and responsiveness to the cultural content presented. On the following day, the instructors conducted an informal interview with the children’s classroom teachers to gather indirect feedback on the museum experience, as conveyed by the children to their parents and subsequently reported to the teachers. This additional data source provided insights into how the museum visit was perceived and internalized by the children beyond the immediate context of the event.

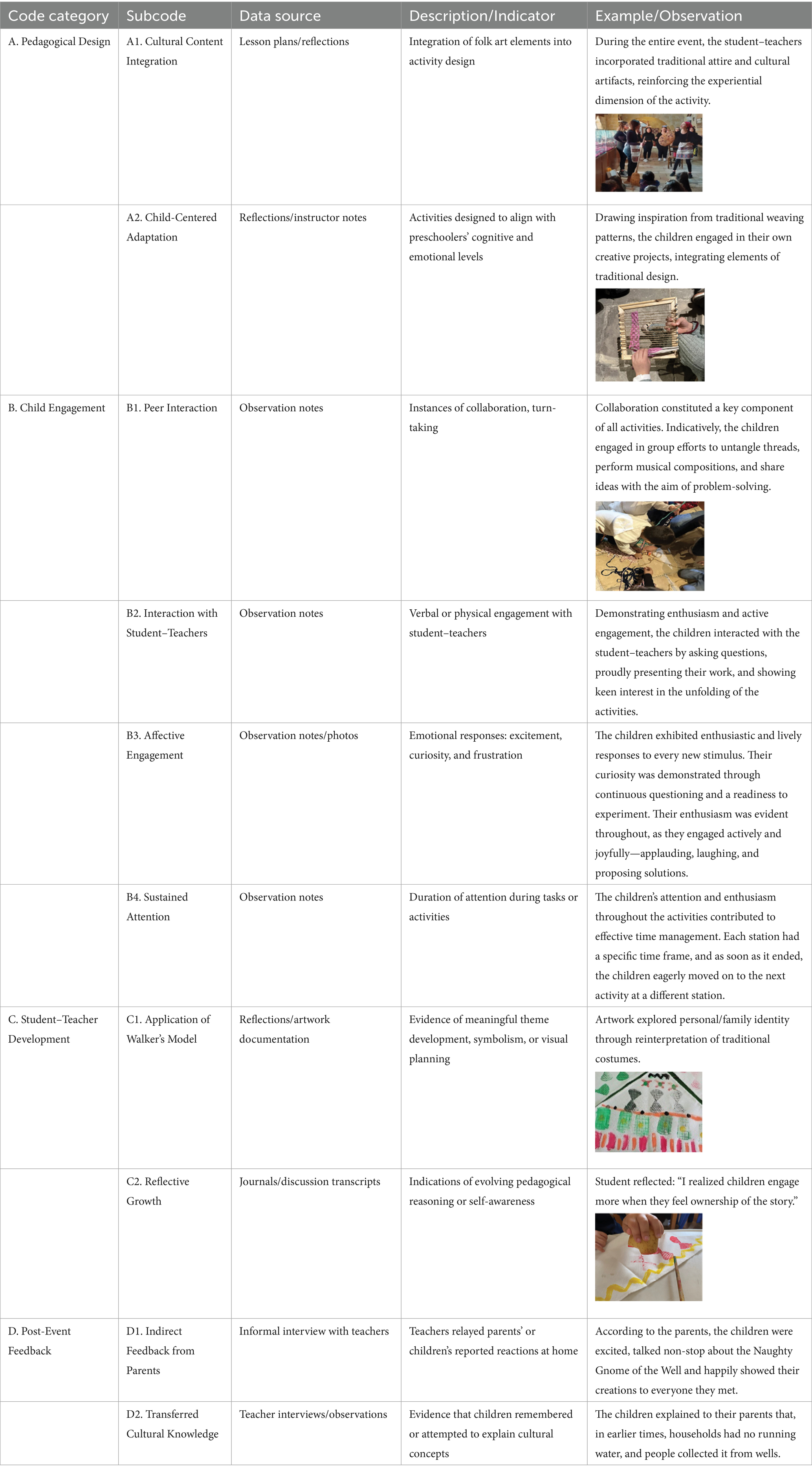

Additionally, student–teachers maintained individual reflective journals throughout the semester, in which they recorded their evolving thoughts on lesson planning, challenges encountered, pedagogical intentions, and perceptions of children’s responses during trial activities. These journals served as a key data source for assessing the depth of pedagogical reasoning and the degree to which student–teachers internalized and personalized the objectives of the course. Table 4 presents the coding matrix developed to organize and analyze both observed behaviors and reported reflections related to the educational intervention. The matrix categorizes data according to emergent themes, linking student–teachers’ documented practices and reflections with the study’s conceptual framework. This structure facilitated a systematic interpretation of the professional and pedagogical outcomes elicited through the museum-based project.

In summary, the methodological framework combined structured observation, reflective documentation, and qualitative coding to generate a multidimensional dataset that captures both the pedagogical design processes of student–teachers and the nature of preschool children’s engagement in the museum setting. This design ensured that the study could directly address its two guiding research questions: first, by examining how the stages of meaningful artmaking informed the instructional designs created by student–teachers and second, by documenting the forms of participation and interaction exhibited by children during the museum-based activities. The integration of multiple data sources—including observations, reflective journals, and teacher feedback—allowed for a triangulated perspective that enhanced the trustworthiness and depth of the analysis. The following section presents the findings derived from this analysis, highlighting how the methodological choices outlined above yielded concrete insights into the educational value of adapting artistic processes for early childhood museum education.

3 Results

The following results present how the stages of meaningful artmaking, as adapted from Walker (2001), were applied by student–teachers in designing museum-based educational activities and how preschool children engaged with these experiences. The analysis was structured around the research questions outlined in the Methodology section: first, exploring how the stages of creating personally meaningful artwork informed the planning, adaptation, and implementation of learning activities and second, examining the forms of participation and types of interaction exhibited by young children during the museum event. By systematically documenting both student–teachers’ creative and pedagogical processes, through reflective journals, lesson plans, collaborative design, and direct observation, and children’s responses, through structured observational criteria, behavioral indicators, and teacher feedback, this study provides empirical insights into how artistic frameworks can guide the development of developmentally meaningful, culturally grounded, and engaging museum experiences for preschool learners. The following sections detail each stage of the design process and the corresponding patterns of child participation, highlighting the intersection of heritage, creativity, and experiential learning.

3.1 Stage 1: tradition—slow looking to define and personalize a big idea/theme

Visual artmaking that is intended to convey a message begins with the selection of a big idea, an issue, which should motivate the creator to learn, reflect, investigate, and discover. Artists begin by identifying a broad concept or overarching theme, typically articulated as a general statement or issue. However, to sustain their creative engagement and ensure that their ideas remain compelling and meaningful, they individualize these concepts by connecting them to their own personal interests and lived experiences. This personalization not only deepens their investment in the creative process but also imbues their work with greater relevance and significance. Similarly, a teacher aiming to design meaningful instruction, and thus adopting a process akin to that of a visual artist, begins with a broad conceptual framework during the initial stage of instructional design. This framework is typically aligned with various developmental domains or thematic units and is shaped by the curriculum, as well as the specific needs of the teaching context, including social, institutional, material, and educational factors. This foundational stage ensures that the instructional design is personally relevant and responsive to the broader educational environment. Within the broader, predetermined framework, meaningful, and creative instructional design approach advocates for the selection of topics derived from the teacher’s personal interests, knowledge, and experiences. Emphasis is placed on the teachers’ ability to personalize the subject matter, ensuring that their actions reflect their unique perspective. This individualization imbues the teaching process with greater significance for the teachers themselves, allowing for a deeper and more authentic engagement with the material.

Initially, in the Planning Activities for Early Childhood course, student–teachers examined the domain of Personal and Social Awareness within the Cyprus Early Childhood Education Curriculum, with a focus on the axis of Identity. Additionally, they explored the Social Studies subject area to support the generation of initial ideas through brainstorming sessions and the development of histograms, drawing on topics from the curriculum related to folk art. Among the various themes identified, the student–teachers demonstrated a particular interest in folk myths.

In instructional design cases, such as the educational event described here, the broader context—the museum—plays a critical role in identifying and refining the topic to be explored with the children. After an initial analysis of the Folk Culture axis from the curriculum, the venue itself was examined to further inform the instructional design process. To facilitate the identification and development of a big idea or central theme, identify, and develop the main idea of our educational event, Slow-Looking techniques (Tishman, 2017) were employed. Slow looking, a method rooted in museum education but applied across various educational contexts, involves sustained, focused observation and engagement with content. This practice fosters active cognitive development, meaning-making, and critical thinking by encouraging a deeper, more immersive interaction with materials, as opposed to the superficial engagement often associated with rapid information consumption. These strategies for slow observation are versatile and can be applied in any educational setting, benefiting both educators during the instructional planning process and students during observational activities. The specific strategies employed are as follows:

1. Establishing categories to guide observation. In museum settings, observation is often directed toward morphological elements and principles of design (such as lines, shapes, colors, and patterns). At the Cyprus Folk Art Museum, observation categories can be framed according to the type of art based on material, the function of the exhibited artifacts, or even the geographical region from which the objects originated. These categories provide a structured approach for observing and analyzing the displays.

2. Conducting an open inventory. While it may be impractical to catalogue every item in a particular space, this strategy involves attempting to compile a detailed list of objects from a specific genre or section. At the Nicosia Folk Art Museum, this technique was initially applied by creating a photographic inventory of all exhibits. For practical purposes, however, the focus was later narrowed to an inventory of only the objects on the ground floor.

3. Modifying the scale and scope of observation. This technique complements the first two strategies by offering methods to adjust and extend the duration of observation. Changing the scale and range of observation can be achieved through the use of tools such as cameras, microscopes, or telescopes, but even a simple shift in body position—moving closer to or further from an object—can alter perspective. It is recommended that student–teachers adjust their viewpoint to a lower angle to better align with the visual perspective of young children.

4. Juxtaposing objects. The deliberate placement of certain objects next to others in an exhibition space encourages the viewer to compare and contrast their characteristics. This technique often highlights distinctions between objects, such as works by the same artist or by different artists from the same period or geographic region, allowing for a deeper understanding of each object through direct comparison.

The detailed morphological analysis of the Cyprus Folk Art Museum exhibits through slow looking and the emphasis on finding visual and conceptual connections between artifacts informed the student–teachers’ approach to planning educational activities. Among the various visual features, pattern emerged as a central element across different exhibits. Conceptually, the connection between the objects was rooted in their historical significance and the roles they played in people’s daily lives in the past. Key questions arose during the planning process: How do we transition from the past to the present? How can we reinterpret or “update” these exhibits? What types of activities can help young children engage with artifacts that held meaning in the past? Following reflection and discussion, the student–teachers concluded that presenting a folk story through a free adaptation could serve as an effective strategy to bridge the gap between past and present, enabling children to relate to historical significance in a contemporary context.

3.2 Stage 2: building a knowledge base—transition

One of the reasons professional artists are able to explore big ideas over extended periods is the substantial time they invest in developing a robust epistemological foundation for their work. This foundation is a critical component of the artistic creation process, as it not only ensures a profound visual outcome but also sustains the artist’s long-term engagement with the subject matter. Artists construct an epistemological framework aligned with their big idea, which may encompass philosophical, historical, geographical, socio-political, or literary dimensions. Similarly, in educational contexts, an in-depth understanding of the subject matter by the teacher is essential for effective instructional design. Before determining the type and content of activities, the teacher must dedicate time to establishing a solid cognitive foundation, ensuring that the instructional approach is grounded in a well-developed body of knowledge.

Within the context of the art education course, student–teachers initially explored the concept of personal identity within the community at the beginning of the semester. They engaged with the theme, “If I were an animal of Cyprus, what animal would I be?” focusing specifically on the island’s native fauna while deliberately excluding domesticated species. This inquiry facilitated the creation of individual glove puppets, as each student–teacher selected an animal that resonated with their own characteristics, habits, needs, and preferences in natural habitats. This approach was designed to deepen their knowledge base and foster a meaningful connection between their personal identity and the ecological context of Cyprus.

In the context of the course of planning early childhood education activities, the student–teachers selected the topic “Myths of Our Land,” which resonated most strongly with their interests. Subsequently, they began to gather information and deepen their understanding of this subject. Various sources concerning Cypriot myths, folk legends, songs, and poems were presented to the class. As the student–teachers engaged in this exploration of their cultural roots, discussions emerged around folk mythical creatures, particularly focusing on a folk poem that mentions the Gnome of the Well. Utilizing this poem as a foundational text and approaching instructional design with a sense of humor, the student–teachers opted to concentrate on gnomes. They identified relevant information pertaining to popular beliefs about haunting creatures, specifically the characteristics and narratives associated with the gnome. However, the student–teachers recognized that the traditional attributes of the gnome, as derived from folk tradition, required modification to be suitable for preschool education. This realization prompted them to progress to the next stage of the process: problem-solving.

3.3 Stage 3: problem-solving—transformation

Artistic creation involves solving both technical and conceptual problems. Technical challenges focus on manipulating media and materials (e.g., how to paint), while conceptual issues address the underlying ideas and meanings (e.g., what to paint). The creative process itself is a form of problem-solving, as artists make choices about media, design elements, subject matter, and style. Guided by a central idea, each stage is shaped by boundaries—both practical and conceptual. These boundaries, rather than restricting, enhance focus and depth, fostering a meaningful and intentional creative process (Walker, 2001).

Conceptual problems in artistic creation involve further investigation of the big idea, even when it has been initially defined. These problems may include withholding information, altering conventional perceptions, or combining objects, people, and situations in unexpected ways. Transformation, a key concept, involves using visual strategies to alter typical representations. Guided by the core idea, artists resolve these challenges through cognitive processes such as risk-taking, intentional play, exploration, and humor, allowing them to transcend conventional boundaries and infuse their work with deeper meaning and innovation (Walker, 2001).

Teachers encounter numerous challenges during instructional design, requiring problem-solving once a big idea is established. Decisions regarding methods of presentation, activities, and the selection of media and materials must align with the theme, objectives, physical context, and children’s needs. Humor is emphasized as a key strategy for guiding this process. While humor is typically intended to provoke laughter, the two concepts should not be conflated; laughter can arise without humor, and not all humor is appropriate. In educational contexts, humor that is manipulative, belittling, or discriminatory is unacceptable. For young children, laughter is often triggered by the unexpected or incongruous, which challenges norms and subverts expectations (Deiter, 2003).

In the art education course, as part of the exploration of the big idea of Identity-Community, student–teachers were tasked with addressing the conceptual challenge of envisioning what a gnome would look like within the context of their own community. To resolve this, a conceptual framework was established, requiring the integration of features from individual glove puppets, previously created in another assignment, to produce collaborative artworks. The distinct characteristics of the various animals, with modifications primarily in color, were humorously combined to form the group’s papier-mâché gnome figures.

In Designing Early Childhood Education Activities course, student–teachers reflected on several key questions:

a. How to introduce the topic of the gnome, typically associated with negativity, to young children?

b. What are the physical constraints and requirements of the learning environment?

c. What activities can be conducted within the museum space to engage children and relate directly to the topic?

d. What media and materials will be necessary?

Through discussion, it was decided to present the gnome in a humorous manner, leveraging humor’s educational benefits. The student–teachers envisioned a mischievous gnome character with a playful personality that would resonate with children. Ideas for the gnome’s naughty antics—such as spoiling hide-and-seek, drawing on walls, hiding to surprise passers-by, and stealing the baker’s pretzels—were enthusiastically developed. This led to the creation of a scenario centered on the Naughty Gnome of the Well, transforming a Cypriot folk myth. The Naughty Gnome, while evading the baker whose pretzels it had stolen, falls into the well—transforming the traditional tale about haunting gnomes into a playful narrative.

In conjunction with the Naughty Gnome of the Well narrative, efforts were made to design original and humorous activities connected to the museum exhibits. During the initial slow-looking process, repetition was identified as a key feature in various exhibits, such as repeating lines in woodcarving and woven looms, repetitive shapes in traditional costumes and embroidery, and patterns in silversmithing. Based on this observation, activities were structured around the concept of pattern. Children, working in small groups, engaged in tasks such as weaving on improvised looms (visual and kinetic pattern), performing musical scores using traditional gourds (sound pattern), playing a floor game with cards (visual and kinetic pattern), untangling threads, and dancing traditional dances (sound and kinetic pattern) alongside the student–teachers.

The activities were not only designed to engage children with patterns but were also analyzed for their broader educational value. Each activity’s potential for experiential learning was carefully considered. For example, the loom activity introduced children to the weaving process, requiring an understanding of both the tool and technique. A well-designed floor game with cards incorporated humor while encouraging observation of objects. Untangling and winding threads fostered patience, while performing a musical score in a group promoted cooperation. Overall, these activities encouraged knowledge-seeking, collaboration, humor, and patience—key life skills that support creative problem-solving.

The next step for the student–teachers was to ensure a coherent connection between the script and the designed activities, addressing both practical and conceptual considerations to create a seamless and meaningful experience for the children. They reflected on how to guide the children, using the storytelling performance, through four activity stations and how to conclude the process effectively. The script was revised so that, despite the Naughty Gnome’s mischief, the community missed its presence. The community leader in the story then challenged the characters and children to complete four tasks to bring the gnome back. Each group received numbered ribbon keys to follow a different sequence of activities. To facilitate the children’s navigation, student–teachers placed numbered signs at each station and transformed storytelling characters into chaperones to guide the children and ensure smooth transitions between activities. Upon completing each station, groups received a handkerchief with a word symbolizing a value from the activity—knowledge, cooperation, humor, and patience. At the conclusion, the handkerchiefs were joined together, and the children celebrated the gnome’s return with a group dance.

4 Discussion

This study highlights the multifaceted benefits of museum-based educational activities in developing both professional and transversal competences in student–teachers. Engaging with folk culture through structured frameworks such as Walker’s Stages of Meaningful Artmaking enabled student–teachers to design developmentally appropriate, culturally grounded curricula while enhancing their skills in instructional planning, heritage pedagogy, and reflective practice. The integration of artistic strategies, such as storytelling, slow looking, and humor, not only fostered creativity and critical thinking but also enriched their capacity for problem-solving and culturally responsive teaching. Moreover, the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of the project cultivated teamwork, communication, and adaptability, while discussions around digital storytelling and inclusive access introduced emerging competencies in technological integration. Through personalizing thematic content and addressing real-world constraints, student–teachers developed empathy, resilience, and a deeper understanding of how to transform abstract cultural knowledge into engaging, meaningful experiences for young learners. Thus, the study demonstrates that museum education offers a rich, experiential context for cultivating reflective, imaginative, and socially responsive early childhood educators.

Most of the student–teachers involved in the planning and execution of the event described in this paper had prior experience visiting museums during middle or primary school. However, none could recall specific details of what they observed, the purpose of the visit, or how it was conducted. Their preparation for these visits had often been insufficient, leading the children to perceive the excursions as merely a break from routine. In contrast, reflections from the student–teachers and feedback from the teachers of the children who participated in the event, Folk Tradition, Transition, and Transformation in Pre-School Education, indicated that the purposefulness of this visit to the Cyprus Folk Art Museum was clearly defined and understood and the event was considered meaningful for all participants.

A central recommendation arising from this case is the structured integration of art-based conceptual frameworks, particularly Walker’s (2001) stages of meaningful artmaking, into early childhood teacher education programs. This scaffolded approach, encompassing definition and personalization of a big idea, building a knowledge base, and engaging in problem-solving, enabled student–teachers to personalize the content while developing a coherent teaching plan. Though typically associated with a linear process, these stages served as iterative points of reflection and action, guiding student–teachers as they transformed abstract ideas into tangible, developmentally appropriate experiences. In doing so, they refined their artistic expression and instructional strategies, gaining confidence and competence as educators. Embedding such frameworks in teacher education encourages the development of professional identities grounded in creativity, cultural awareness, and holistic instructional design. The project’s interdisciplinary foundation, combining coursework in Visual Arts Education and Planning Activities in Early Childhood, provided student–teachers with conceptual and practical coherence across domains. By approaching a shared theme from multiple disciplinary perspectives, they were able to develop transferable skills, reinforce learning outcomes, and model integrated curriculum design. Such interdisciplinary collaboration mirrors the multifaceted nature of real-world teaching and should be embedded in teacher education programs through coordinated assignments and team-based learning.

Equally vital was the incorporation of slow-looking techniques drawn from museum education, which cultivated the student–teachers’ capacity to observe, interpret, and analyze material culture. Structured observation strategies, such as detailed inventories, changes in scale, and juxtaposition of artifacts, enabled them to identify morphological and thematic elements within the museum collection, which later informed the content and structure of their activities. This method promoted deeper inquiry, transforming the museum space into a dynamic learning environment rather than a passive backdrop. Training future educators in these methods cultivates inquiry-based thinking and equips them to facilitate meaningful engagement with cultural objects in both formal and informal learning environments.

Personalization of the thematic focus proved essential in sustaining student–teacher motivation. When student–teachers were given agency to select and adapt broad concepts, such as identity, folk art, or mythology, they developed lessons that were more relevant, culturally resonant, and pedagogically clear. This practice mirrored the artistic process itself, where the interpretation of a big idea becomes personally meaningful. Encouraging this kind of personalization in teacher education can lead to more empathetic, responsive, and authentic teaching, especially in multicultural or heritage-based contexts.

Setting boundaries during any type of production, including instructional design, effectively leads to creative pathways. This aligns with research showing that creativity is often enhanced by constraints rather than their absence (Finke et al., 1996). The planning of the educational event at the Cyprus Folk Art Museum began with the broad theme of tradition and was gradually narrowed to focus on folk myths and visual patterns. The shift to the Naughty Gnome of the Well also relied on setting conceptual boundaries. Defining constraints during problem-solving and adapting the haunting gnome to forms and behaviors appropriate for preschool children ensured their active engagement in the museum setting, with humor serving as the key strategy.

Humor played a key role throughout the instructional design and implementation phases. Its strategic use helped reframe complex or potentially frightening cultural content into playful, developmentally appropriate narratives. Far from being a peripheral element, humor was integral to the problem-solving phase, fostering cognitive flexibility and emotional connection. In general, humor fosters positive interactions and helps people connect. In educational settings, its effective use can enhance classroom climate and improve communication between teachers and students. It also serves as a classroom management tool, fostering a harmonious teacher–student relationship and increasing the likelihood of effective learning. Humor reduces criticism, alleviates stress, and helps students focus by maintaining interest in the lesson when it is relevant to the content. Moreover, humor fosters community, communication, critical thinking, imagination, and creativity among students (Kim and Park, 2017). Teachers do not need to be comedians to incorporate humor into their lessons. Simple strategies such as starting with a daily joke, posing humorous questions in assessments, or relating content to playful scenarios—like the Naughty Gnome of the Well—can engage students. Teachers might also use song lyrics to teach math or introduce surprises that capture students’ attention in an unexpected yet respectful way.

A key element of the event at the Cyprus Folk Art Museum was experiential, multisensory learning, particularly in the design of the museum-based activities. Each station—dedicated to sound, movement, pattern recognition, tactile experience, or storytelling—allowed children to interact with cultural content through multiple modalities. This approach addressed diverse learning styles and helped foster social–emotional competencies such as cooperation, patience, and empathy. Training educators to design embodied, sensory-rich experiences is essential in heritage education, where abstract cultural concepts benefit from tangible, interactive engagement.

Finally, the use of storytelling proved to be an effective strategy for structuring activities and guiding children toward purposeful engagement. The narrative framework guided children through the museum experience, connecting spaces, artifacts, and activities in a cohesive journey. Traditionally, Greek folk stories begin with the phrase “Red thread tied up on the wheel, turn in, kick it, give it a spin for a tale to begin.” Storytelling in the museum began when the children followed a red thread that guided them from the yard to the indoor space of the museum. At the other end of the line, a poster outlined a conclusion: “A red thread woven, tradition tight. One pulls left, another right, yet it binds us, one and all, in its grasp., we rise, never fall! Knowledge, patience, humor too, and cooperation sees us through. With imagination’s spark in sight, inspiration takes its flight!” The red thread became a metaphor for cultural continuity and collective memory, culminating in a poetic closure that reinforced shared values. Looking ahead, digital storytelling and interactive media could further enhance accessibility and inclusivity in cultural education. Developing such tools, anchored in traditional content yet adaptable to contemporary digital formats, ensures that all children, regardless of ability, can engage in the living tapestry of heritage. Could patterns from a woven bedcover be animated and transformed into entirely unexpected forms? How might contemporary technologies such as virtual and augmented reality facilitate the reinterpretation of tradition for young audiences? Furthermore, how can these tools deepen children’s understanding of cultural heritage and the past? Could we, for example, take children on a digital journey tracing the life of a thread—from the wind to the loom, culminating in the woven artifact housed at the museum? Could a weaving pattern be “brought to life” to inspire children’s imaginations and foster a conceptual journey from the past, through the present, and into the future? Considering that digital accessibility ensures inclusion by removing barriers and providing equal opportunities for all (Chiscano and Jiménez-Zarco, 2021), we propose developing accessible digital materials related to popular culture and enhancing inclusion. Digital accessibility to popular art enables equal access and engagement for people with disabilities. Anyone could digitally follow the red thread tied up, spun on the wind, give it a spinning wheel to spin, a fairy tale to begin, and a thousand wonders to live!

5 Conceptual and methodological constraints in folk culture transformation for education

The transformation of folk culture into developmentally appropriate educational experiences for young children entails several conceptual and methodological challenges, which were systematically addressed during the planning and implementation of the event discussed in this article. These challenges were thoughtfully navigated; however, their recurrence in similar future initiatives necessitates the consideration of strategies to mitigate their impact.

One of the central conceptual constraints is balancing the preservation of cultural authenticity with the need to make traditional elements relevant to young children. Adapting folk narratives or symbols risks oversimplifying or distorting their original meanings, potentially reducing the depth of cultural heritage. To address this, future projects could incorporate collaborative consultations with folklorists, cultural historians, or community elders to ensure interpretive fidelity while still enabling age-appropriate adaptation. Additionally, positioning children as co-creators, through open-ended storytelling or artistic reinterpretation, can allow for imaginative engagement without compromising cultural integrity, as the narrative retains its symbolic core while inviting multiple perspectives.

Methodologically, the instructional design framework, anchored in artistic strategies such as identifying a big idea, setting boundaries, and problem-solving, provides a structured approach that can inadvertently constrain spontaneous creativity if overly reliant on predefined processes. To mitigate this, future implementations might adopt a hybrid model that balances structure with iterative flexibility. For example, instructors could integrate reflective checkpoints that allow student–teachers to revise plans in response to emerging ideas or feedback, thereby preserving creative responsiveness throughout the process.

Time limitations also influenced the depth of cultural engagement. The semester-long timeframe, while sufficient for basic planning and implementation, restricted opportunities for extended exploration or more nuanced transformations of folk content. Addressing this requires either a redesign of curricular timelines to allow for longitudinal projects or the integration of folk culture themes across multiple courses or semesters. Such continuity would support deeper research, sustained collaboration, and more meaningful connections with traditional knowledge systems.

The museum setting, while enriching, imposed its own constraints, particularly in terms of limited physical interaction with artifacts and environmental restrictions on movement and sound. To expand pedagogical possibilities within these parameters, future projects could leverage digital tools to create complementary experiences, such as augmented reality applications or virtual replicas that allow for hands-on engagement without compromising artifact preservation. Furthermore, early coordination with museum staff can enable the co-design of activities that align both with conservation policies and pedagogical goals.

Resource limitation, whether in materials, time, or access, shaped the feasibility of certain proposed activities. To address this, it is recommended that future projects build in a resource audit during early planning stages and explore partnerships with cultural institutions, local artists, or educational technology providers. These collaborations could expand material access and provide alternative means of engaging with cultural heritage.

In summary, while the transformation of folk culture into early childhood education presents inherent tensions between preservation and adaptation, these can be effectively addressed through interdisciplinary collaboration, flexible design frameworks, extended timelines, and strategic use of technology. By anticipating and systematically addressing these constraints, future projects can enhance both the integrity and impact of cultural education in early learning contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Education of the University of Nicosia. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participating student–teachers and preschool children’s legal guardians. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alter-Muri, S., and Klein, L. (2007). Dissolving the boundaries: postmodern art and art therapy. Art Ther. 24, 82–86. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2007.10129584

Chiscano, C. M., and Jiménez-Zarco, A. (2021). Towards an inclusive museum management strategy. An exploratory study of consumption experience in visitors with disabilities. The case of the cosmocaixa science museum. Sustainability 13:660. doi: 10.3390/su13020660

Deiter, R. (2003). The use of humor as a teaching tool in the college classroom. NACTA J., 44:20–28.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Einarsdottir, J. (2007). Research with children: methodological and ethical challenges. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 15, 197–211. doi: 10.1080/13502930701321477

Huhn, A., and Anderson, A. (2021). Promoting social justice through storytelling in museums. Mus. Soc. 19, 351–368. doi: 10.29311/mas.v19i3.3775

Jeffery, T. (2022). Towards an eco-decolonial museum practice through critical realism and cultural historical activity theory. J. Crit. Realism 21, 170–195. doi: 10.1080/14767430.2022.2031788

Kim, S., and Park, S. H. (2017). Humor in the language classroom: a review of the literature. Korea Assoc. Primary English Educ. 23, 241–262. doi: 10.25231/pee.2017.23.4.241

Løvlie, A. S., Eklund, L., Waern, A., Ryding, K., and Rajkowska, P. (2021). “Designing for interpersonal museum experiences” in Museums and the challenge of change. ed. G. Black (London, UK: Routledge), 224–239.

Mayer, M. M. (2005). Bridging the theory-practice divide in contemporary art museum education. Art Educ. 58, 13–17. doi: 10.1080/00043125.2005.11651530

Mayo, P. (2013). Museums as sites of critical pedagogical practice. Rev. Education Pedagogy Cultural Studies 35, 144–153. doi: 10.1080/10714413.2013.778661

Michalopoulos, S., and Xue, M. M. (2021). Folklore. Q. J. Econ. 136, 1993–2046. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjab003

Mörsch, C., Sachs, A., and Sieber, T.. (Contemporary curating and museum education (1st ed.). (2017). Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv371ck10

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, (2012). Situated learning, in instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Available online at:https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide

Piscitelli, B., and Anderson, D. (2001). Young children's perspectives of museum settings and experiences. Mus. Manag. Curat. 19, 269–282. doi: 10.1080/09647770100401903

Sanjaya, D. B., Suartama, I. K., Suastika, I. N., Sukadi, S., and Dewantara, I. P. M. (2021). The implementation of Balinese folflore-based civic education for strengthening character education. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 16, 303–316. doi: 10.18844/cjes.v16i1.5529

Tishman, S. (2017). Slow looking: The art and practice of learning through observation. New York, NY: Routledge.

High Museum of Art. Crochet chair (prototype). Wanders, Marcel (1963). Available online at: https://high.org/collection/crochet-chair-prototype/

Keywords: folk art, early childhood education, situated learning, museum education, meaningful artmaking, slow looking

Citation: Pitri E and Michaelidou A (2025) Folk tradition, transition, and transformation for early childhood education. Front. Educ. 10:1501558. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1501558

Edited by:

María Del Mar Bernabé Villodre, University of Valencia, SpainReviewed by:

I. Kadek Suartama, Ganesha University of Education, IndonesiaDaiana Yamila Rigo, CONICEI ISTE UNRC, Argentina

Copyright © 2025 Pitri and Michaelidou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eliza Pitri, cGl0cmkuZUB1bmljLmFjLmN5

Eliza Pitri

Eliza Pitri Antonia Michaelidou

Antonia Michaelidou