- School of Applied and Interdisciplinary Studies, Kansas State University, Olathe, KS, United States

Introduction: Academic leaders and faculty in professional academic programs often gather input from practitioners to test the relevance of academic curricula. Program advisory boards for professional programs are established to provide feedback on curricula and industry needs; however, there is limited research examining the management of these boards. Although there exists research on managing volunteers in non-profit organizations and managing boards of directors, academic advisory boards occupy a position between informal volunteer arrangements and formal boards of directors with oversight responsibilities. The objective of this project was to use existing research on volunteer and board of director management to understand the experience of three academic advisory boards that provide advice and guidance on animal health academic programs.

Methods: Two surveys were administered to existing advisory boards at Kansas State University’s Olathe, Kansas Campus. The survey questions were aimed at determining the strengths and weaknesses of the campus’s academic advisory board recruitment and management practices using evidence-based practices for effective volunteer management.

Results: The study’s findings suggest that the primary motivation for serving on an academic advisory board is a strong desire to contribute to the mission and vision of the institution. Several tactics emerged for engaging board members, including developing strong leadership in setting purpose and objectives, creating space for members to participate in dialogue in strategy, and assigning tasks that align with their knowledge, skill set, and network.

Discussion: Best practices from this study demonstrate meaningful approaches to engage advisory boards so that volunteers feel more valued in how they can positively impact the future of educational programming.

Introduction

Academic leaders and faculty in professional academic programs, such as veterinary medicine, often gather input from practitioners to test the currency and relevance of academic curricula. It is an established practice to create academic program advisory boards for professional programs to provide feedback on curricula and workforce needs.

Despite the popularity of academic advisory boards, research to understand the role of academic advisory boards is limited. Zahra et al. (2011, p. 117) reported that “academic literature on the role and composition of advisory academic boards is sparse and fails to inform us about the factors that influence the contributions of these boards in general and student learning in particular.” More recently, Söderlund et al. (2017) observed that there has been a decline in scholarly interest in academic advisory boards, which may have broader implications for academic and industry relationships.

In contrast to this trend, the Kansas State University Olathe campus (K-State Olathe) has leveraged its location in the Kansas City area to use industry representatives as a sounding board for academic programming. The greater Kansas City region is a national leader in the U.S. animal health and nutrition industries, with companies in the Kansas City area accounting for nearly 56% of animal health, diagnostics, and pet food sales in the global animal health market, and is part of the Kansas City Animal Health Corridor (KCAHC).1 Positioned within the KCAHC, K-State Olathe offers professional academic programs that rely on the industry’s input for student recruitment and curriculum recommendations to guide academic programs, such as the Veterinary Biomedical Science Master of Science program at Olathe and the Master of Science in Applied Biosciences program, as well as graduate level academic certificate programs relevant to the animal health industry. Industry input for the campus and its programs occurs in the form of advisory boards composed of industry leaders specializing in animal health, agriculture, business, government, and academia.

The purpose of this study was to identify the strengths and weaknesses of recruitment, management, and engagement practices in academic advisory boards by applying evidence-based strategies from non-academic volunteers and the board of director management. Uniquely focused on the field of animal health, this research investigates best practices for enhancing advisory board management in academic settings to offer insights into factors that influence contributions to student learning through proven strategies.

Background

Research on managing academic advisory boards is limited in both quantity and scope. Existing research focuses largely on the functions of boards and the perceived benefits and challenges of academic advisory boards. While some studies examine existing practices (Söderlund et al., 2017; Ellingson et al., 2010; Kaupins and Coco, 2002; Nagai and Nehls, 2014), report perceived effectiveness (Ellingson et al., 2010), or provide guidelines for advisory boards (Dorazio, 1996; Olson, 2008), many do not benchmark the current effectiveness of managing academic advisory boards against evidence-based practices. There is also a lack of research specifically addressing volunteer service on academic advisory boards.

The traditional functions of academic advisory boards have been cataloged elsewhere and are generally consistent. Studies have shown that the academic advisory boards provide feedback on curriculum and program development, facilitate student internships and employment opportunities, provide accreditation support, and fundraise or provide financial support (Söderlund et al., 2017; Ellingson et al., 2010; Kaupins and Coco, 2002). Other functions mentioned in the literature include advocating for programs inside and outside the institution (Söderlund et al., 2017), aiding in strategic planning (Ellingson et al., 2010), contributing to mission development (Ellingson et al., 2010; Kaupins and Coco, 2002), assisting with program assessment activities (Ellingson et al., 2010), and identifying trends in the profession or field (Söderlund et al., 2017).

The benefits of academic advisory boards vary depending on the role and perspective. Dorazio (1996) explains that the overall role of advisory boards is to bridge academics and the workplace, which yields several benefits. Students benefit from the current curriculum, advice from practitioners on interview skills or portfolio development, and practicums to help them prepare for jobs (Dorazio, 1996). Academic programs benefit from the advice, resources, collaboration opportunities, and accreditation evidence that advisory boards supply (Dorazio, 1996). Advisory board members can benefit by preparing the next generation of professionals in their field, by networking, or by fulfilling community service expectations of their employer (Dorazio, 1996).

Regarding challenges, Söderlund et al. (2017) noted that both administrators and board members consider meeting logistics, such as scheduling, to be a significant difficulty. Additionally, administrators identify tension between academic and more skills-oriented education as a challenge (Söderlund et al., 2017). Advisory board members also indicated a need for more opportunities to provide authentic input and feedback before decisions are made (Söderlund et al., 2017).

Nagai and Nehls (2014) examined why non-alumni volunteers chose to serve on a hospitality management academic board. The volunteers’ answers included both intangible rewards, such as an interest in education, respect or a connection to the college, and service to the community or industry. Other participants identified professional development or meeting the expectations of their employer as the reason for service (Nagai and Nehls, 2014).

Conceptual framework

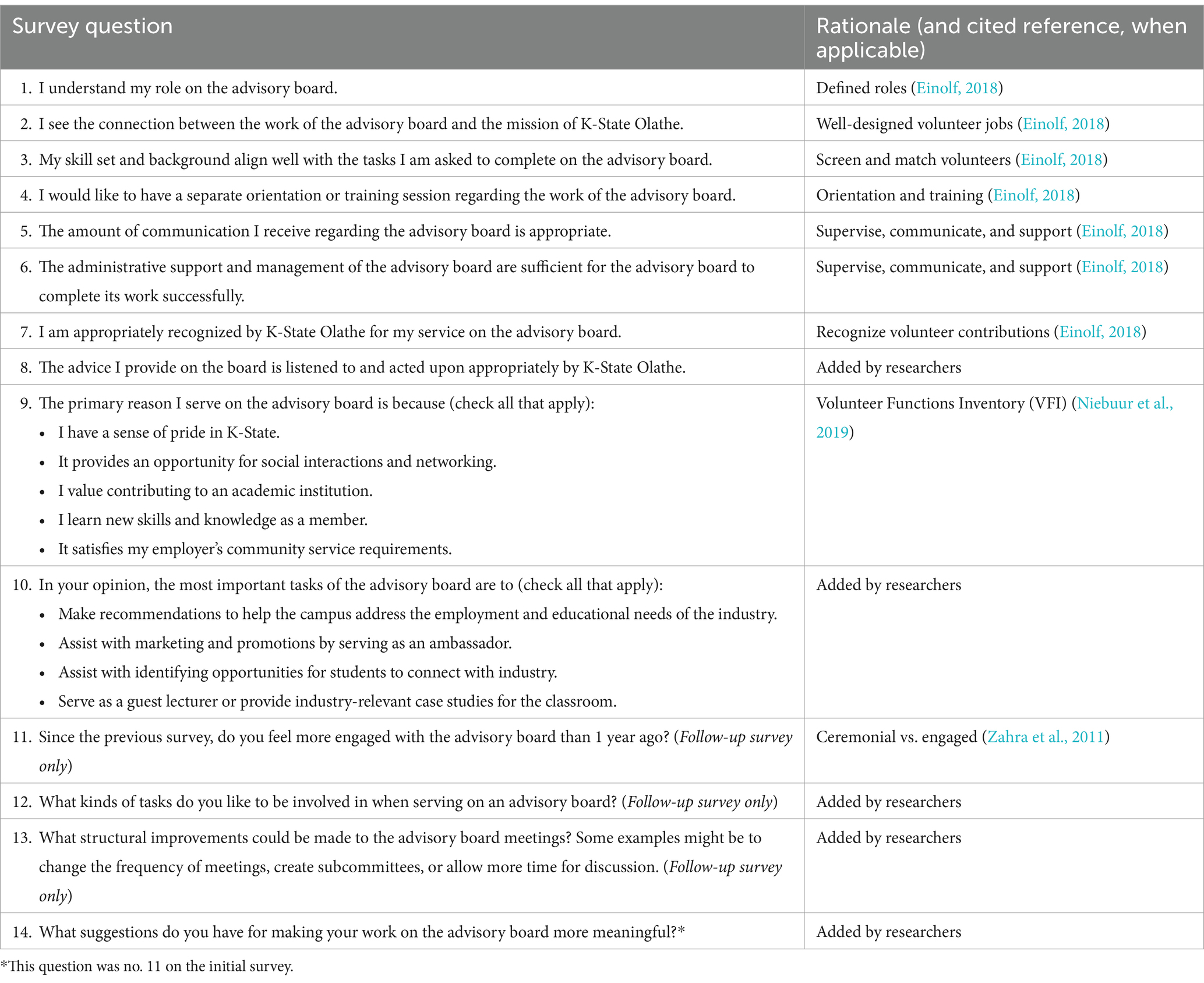

The development of the survey instruments for this study was guided by rigorous theoretical frameworks and evidence-based volunteer management practices to ensure both relevance and validity. Survey data were collected at two different times. The “follow-up survey” occurred 14 months after the “initial survey.” The sources used to develop each question for both surveys are listed in Table 1.

Questions 1–7 were directly aligned with Einolf’s synthesis of 81 studies identifying practices correlated with positive volunteer outcomes, which are adapted from the human resource management model of volunteer management (Einolf, 2018). His research reveals 11 practices that correlate with positive volunteer outcomes, with 8 from the human resource management model of volunteer management (Einolf, 2018). Einolf’s 11 practices include the following: (1) liability insurance; (2) defined roles; (3) well-designed volunteer jobs, including seeing the work as meaningful and contributing to the good of clients; (4) recruitment; (5) screening and matching volunteers; (6) orientation and training; (7) supervision, communication, and support; (8) recognition; (9) satisfying motivations; (10) encouraging reflection; and (11) encouraging a supportive environment (Einolf, 2018). These practices were chosen because they address critical components of effective volunteer engagement, including role clarity, alignment of skills and tasks, communication, recognition, and organizational support.

Question 8 was added to the survey by the research team regarding whether advice was listened to and acted upon. Question 9 in the survey was used to explore motivations for volunteering for academic boards based on a study by Niebuur et al. (2019) using the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI). The VFI was developed to assess volunteer motivations in individuals, where it assumes that the underlying motivations for volunteering can be distinguished into six psychological functions that can be served by volunteering. The six psychological functions include the following: (1) values function, (2) understanding function, (3) social function, (4) career function, (5) protective function, and (6) enhancement function (Niebuur et al., 2019).

Question 10 was designed by the research team to reflect the strategic tasks most expected of academic advisory boards. Additional open-ended questions (Questions 11–14) were included to allow for deeper qualitative insights into engagement, task preferences, and suggestions for meaningful participation, especially considering distinctions between ceremonial and engaged boards that were addressed in Question 11. More specifically, Zahra et al. (2011) distinguished between ceremonial and engaged boards and argued the degree of engagement that a board can influence students’ experiences. They examined academic advisory boards in entrepreneurship centers and found that the type of board (ceremonial or engaged) influences factors such as the priority placed on board related to student learning activities, preferences regarding curriculum content and teaching approaches, preferences regarding the approaches used to gauge student learning, and the emphasis placed on the skills students should learn (Zahra et al., 2011).

Overall, this blended approach ensured that the survey instruments captured both validated measures and context-specific priorities relevant to academic advisory board service in the animal health domain.

Methods

The initial Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved survey (approval date: 12 December 2022), aimed at determining the strengths and weaknesses of the academic advisory board regarding recruitment and management practices, was administered to 39 existing advisory board members at K-State Olathe in January 2023. Most questions used a 5-point Likert scale with the response options of agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, or disagree.

The results from the initial survey were reviewed, and strategies to increase board management effectiveness were implemented. These strategies included matching board members with board missions and tasks, providing board members with pre-read materials and agendas with questions for in-person discussion, balancing presentations with open discussion, and facilitating breakout sessions during the meetings. A follow-up survey was then conducted to assess if these strategic actions had an impact.

The follow-up survey was also an IRB-approved survey (approval date: 20 February 2024). It included the original questions plus three new questions (Table 1). The survey was administered to 49 existing advisory board members in March 2024, and it also included additional opportunities for respondents to further explain their responses.

Quantitative results for Questions 1–8 of the survey were analyzed as described by Carnegie Mellon University’s guidance for converting Likert-scale data into numeric values (see Table 1 for survey questions) (Carnegie Mellon University, n.d.). Questions 9 and 10 of the survey allowed for multiple answers, and the results were analyzed by examining the top three responses based on the frequency of response.

The researchers did not report individual comments from respondents to the initial survey. Narrative responses to four questions (Questions 11–14 in Table 1) from the follow-up survey were analyzed, as described below, by two of the researchers who evaluated the comments for emerging themes.

To further address the research question, the follow-up survey was used to qualitatively investigate factors that influence volunteer motivation and engagement among academic advisory board members. To that end, an ex post facto research design was employed using open-ended responses from individuals who completed the survey instrument. Ex post facto studies “investigate possible cause-and-effect relationships by observing an existing condition or state of affairs and searching back in time for plausible causal factors.”11(p303) This type of research is useful in studying groups that have undergone the same experiences and allows the researcher to examine retrospectively independent variables for their possible relationship to the dependent variable (Cohen et al., 2011). As a result, the researcher is allowed to focus on a specific group and examine the factors that impacted their overall experience (Jackson and Laanan, 2015). In this case, this study focused on board members participating in the three academic advisory boards.

The researchers examined volunteer motivations by the board members, specifically examining participant responses to open-ended prompts focused on their feelings of engagement, involvement preferences, and what would make their work on the advisory board more enjoyable. In evaluating the responses, two authors (RS, BAW) independently analyzed the sample of the responses, examined the phrase level of analysis, and established a set of themes tied to the literature (Miles and Huberman, 1994). The authors reviewed all responses and came to an agreement on each response.

Results

For the initial survey, the response rate was 25 out of 39 or 64%, whereas the response rate for the follow-up survey was 26 out of 49 or 53%.

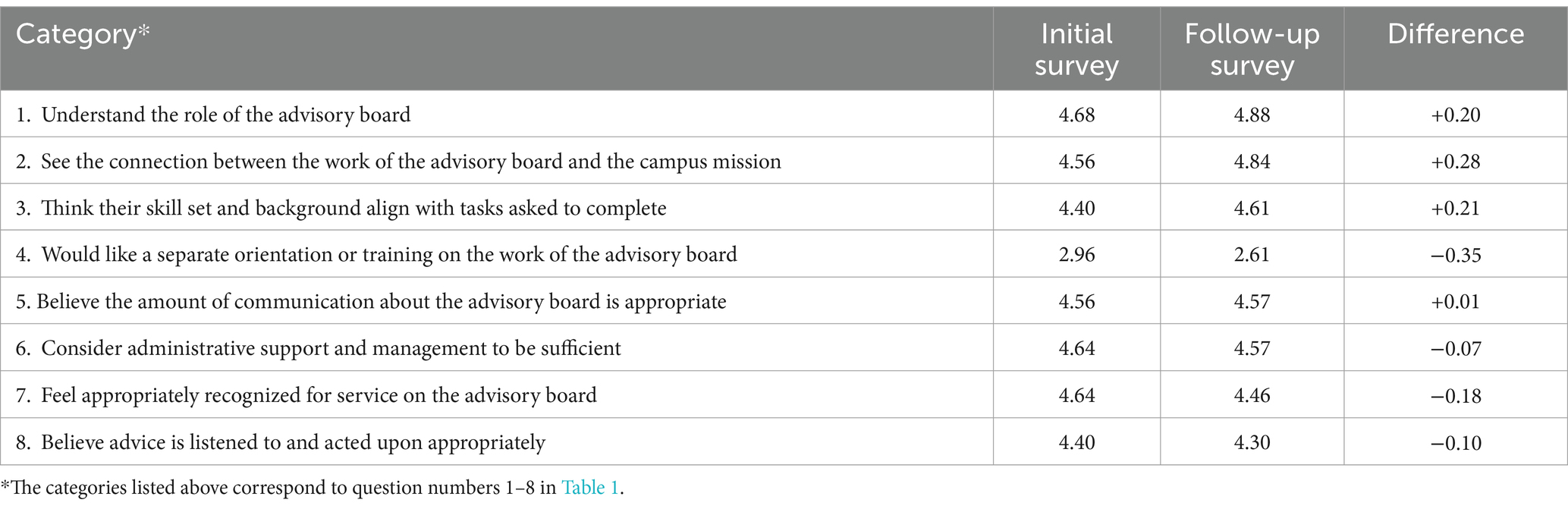

For Questions 1–8 (see Table 1), a 5-point Likert scale was used, and the average scores and differences in scores between the initial and follow-up surveys are shown in Table 2. For the initial and follow-up surveys, advisory board members reported a high agreement score regarding their understanding of their role on the advisory board (average scores of 4.68 and 4.88, respectively) and their recognition of the connection between the work of the advisory board and the mission of the university campus (average scores of 4.56 and 4.84, respectively). They agreed that their skill sets and professional backgrounds aligned well with the board tasks (average scores of 4.40 and 4.61, respectively). As described above, there were notable positive increases in all three categories between the two surveys, with a range of +0.20 to +0.28. However, there was less consensus among advisory group members regarding whether a separate orientation or training session regarding the work of the advisory board would be appropriate (average scores of 2.96 and 2.61, respectively). For the initial and follow-up surveys, the advisory groups agreed that the amount of communication they received regarding the advisory board was appropriate (average scores of 4.56 and 4.57, respectively). They agreed that administrative support and management were sufficient to complete the board’s work successfully (average scores of 4.64 and 4.57, respectively), and they felt appropriately recognized by the university campus for their service on the advisory board (average scores of 4.64 and 4.46, respectively). Most members believed that their advice was listened to and acted upon appropriately by the university campus (average scores of 4.40 and 4.30, respectively).

For Question 9, respondents were asked to rank in order why they serve on the board (Table 1; Figure 1A). For the initial and follow-up surveys, the highest-ranked response was that the board members value contributing to an academic institution (raw scores of 20 and 21, respectively), and the second-highest ranked answer was a sense of pride in the university (raw scores of 12 and 13, respectively). Respondents to the initial survey ranked learning new skills and knowledge as third highest rank (raw score of 9), while respondents to the follow-up survey ranked opportunities for social interactions and networking (raw score of 11).

Figure 1. Number of responses to survey questions 9 and 10. Questions 9 (A) and 10 (B) asked advisory board members why they serve on the board and what the most important tasks are of the advisory board, respectively.

Question 10 asked board members to identify the most important rank-order tasks of the advisory board (Table 1; Figure 1B). The responses were consistent across both surveys. The highest-ranked task was making recommendations to help the campus address the employment and educational needs of industry (raw scores of 22 and 22, respectively), whereas the second highest-ranked task was helping students connect with industry (raw scores of 15 and 17, respectively). The third highest-ranked response was serving as an ambassador (raw scores of 10 and 11, respectively).

Regarding Question 11 in the follow-up survey, the qualitative results from the survey instrument highlighted two major themes related to engagement: (1) a strong board purpose driven by the organization’s leader and (2) a sense of greater connection to the campus (see Question 11 in Table 1). Respondents emphasized that effective and visible leadership plays a crucial role in fostering a sense of purpose and engagement among community members. Participants noted that leaders who provide a strong vision, emphasize a growth mindset and improvement, and clearly articulate the board’s purpose, create an environment where members feel valued and motivated to participate, and their advice is seen as meaningful and impactful. For example, one respondent noted that the campus leader “brings more structure to the board,” while another identified the campus leader “has done a great job with making the [institution] a performing board, and he has raised the bar to ensure our advice is impactful to the [campus].” Additionally, the theme of stronger connection to the campus emerged, with many respondents having a clearer understanding of programs and activities offered at the campus and, thus, a stronger connection to the mission and vision of the campus. Together, these themes suggest that engagement can be significantly boosted by leaders articulating a strong board purpose and cultivating meaningful connections within the campus environment.

The qualitative results from the survey on board member involvement (see Question 12 in Table 1) revealed three broad themes regarding the types of tasks they prefer when serving on a board: (1) strategy, (2) program and curriculum development, and (3) fostering industry and community connections. Identifying tasks related to strategy, respondents expressed a strong interest in engaging with strategic initiatives and providing feedback and advice on processes that shape the future direction of the organization. Several responses focused on “advising on campus direction, helping with finance topics,” and “problem identification and solution generation.” One respondent identified a key task of “being an ambassador for the relevant programs to the rest of my community, keeping an eye out for opportunities to collaborate.” One respondent identified the need for give-and-take between information shared between members and leadership “so as not to be a ‘sit & soak’ board.”

Another key theme associated with involvement was program and curriculum development, where members appreciated contributing to the creation and refinement of programs, sharing their expertise to ensure relevance and quality, and aligning offerings with industry standards and needs. Respondents enjoyed “advising faculty and development/revising of programs,” and “identifying additional course needs.” Others identified ideation-related tasks as meaningful contributions, including “discussions on new ideas to attract students and new course offerings.”

Finally, fostering industry and community connections was highlighted as a valued area of involvement, with respondents eager to leverage their networks to build partnerships, help make connections for students and industry, and create opportunities for collaboration. These themes underscore the board members’ desire to take on roles that are impactful, forward-thinking, and closely tied to their skills and professional networks.

The qualitative results from the survey on structural improvements to advisory board meetings (see Question 13 in Table 1) identified three key themes: (1) clear objectives and focus, (2) the creation of workgroups and subcommittees, and (3) meeting delivery and time commitments. Respondents emphasized the need for meetings to have clear, well-defined objectives and a focused agenda to ensure that discussions are purposeful and aligned with the board’s strategic goals. Some respondents expressed a clear need to focus on board tasks, perhaps with a “focus on one major area or topic per meeting” and outcomes that include “a better understanding of what success looks like either for the committee or for the program.” Others noted that any material provided ahead of time would allow for clearer feedback and “more time for discussion.”

Many respondents suggested the formation of workgroups and subcommittees dedicated to specific tasks or areas, allowing for deeper engagement and more efficient progress on complex issues. This approach was viewed as an approach to harness board members’ expertise more effectively and to keep them actively involved in meetings. This also would allow “more time for board members to engage with each other” and might “allow for more interaction with faculty.” Additionally, respondents called for improvements in meeting delivery, including the use of diverse formats, such as virtual or hybrid meetings, to accommodate busy schedules.

Narrative comments were further collected and analyzed in the follow-up survey to assess engagement, tasks, and structural improvements. In the follow-up survey, 65% of the respondents indicated that they feel more engaged with the advisory board than they did a year ago. Committee members also indicated that they want to be involved in tasks related to strategy, programs, and curriculum development. The structural improvements of advisory group meetings between the initial and follow-up surveys were implemented, and they included the creation of subcommittees and dedicated time for engagement.

In both surveys, participants were asked for suggestions for making the time on the advisory board more meaningful. In the initial survey, participants expressed a desire for shorter, more frequent meetings and more actionable tasks rather than general discussions and program reviews. The qualitative survey results on the follow-up survey identified two key themes (see Question 14 in Table 1): (1) service and giving back and (2) closing the feedback loop. Survey respondents expressed a strong desire for their work to have a tangible impact, emphasizing a strong desire for service and giving back to the organization and community. They identified a desire to contribute to meaningful causes or initiatives that resonate with their values and expertise, which includes volunteering and serving as a “guest lecturer.”

The second theme, closing the feedback loop, highlighted the need for clear communication regarding how their input and decisions influence the board’s outcomes and actions. Respondents suggested that regular updates on progress, outcomes of their recommendations, and recognition of their contributions, particularly the impacts on students, would enhance their sense of purpose and motivation. Together, these themes suggest that making board work more meaningful involves connecting members’ efforts directly to the broader mission of service and ensuring their voices are heard and valued through continuous feedback and communication.

Discussion

This study aimed to understand and improve the management of academic advisory boards at K-State Olathe, focusing on the recruitment, engagement, and motivation of board members. Two surveys of the campus’s advisory boards provided valuable insights into member satisfaction and how the campus can better support their roles in advancing educational programs. While most advisory board members have a general understanding of their responsibilities, this study found that clarity can be further strengthened by deliberately aligning members’ professional backgrounds with the tasks they are expected to perform. Strategic selection of board members ensures that their roles align with institutional expectations. Our findings reinforce that individuals in middle management or technical positions are well-suited for program-specific tasks, whereas more senior leadership may be more motivated to contribute to direction and advice on campus-wide initiatives. Additionally, the deepened understanding of how the boards contribute to a university’s mission provides a link to the institution’s strategic planning efforts.

The findings from the survey regarding why members serve and the tasks they value are consistent with the findings of the literature. The board members serve primarily because they value contributing to an academic institution, a finding that is consistent with the research of Nagai and Nehls (2014). The board members see their most important task as helping address the needs of the industry. In other words, they see the benefit of being able to prepare new professionals for their fields, as identified by Dorazio (1996).

Furthermore, the study highlighted the importance of regular assessment through surveys to identify the strengths and weaknesses in advisory board management. Continuous evaluation allows institutions to implement targeted strategies, such as creating subcommittees or assigning specific roles that maximize the use of board members’ professional networks and skills. By fostering a stronger connection between advisory boards and the institution’s mission, leaders can ensure that members feel valued and that their contributions have a meaningful impact on the university’s educational programming.

One of the most noteworthy changes between the two surveys was related to the board members’ feelings of engagement. As detailed in the results, the sense of increased engagement was attributed to leadership providing clear direction and purpose. Additionally, feedback from the initial survey encouraged the campus to develop more meaningful ways to move from ceremonial boards to performing boards that engage individuals in positively impacting the future of educational programming. Board members suggested that work groups or subcommittees would be useful for accomplishing the board’s work. Additionally, they indicated that they would like more time for discussion and follow-up from the university’s organizers when changes are made as a result of the board’s input.

Based on feedback from the initial survey, several engagement strategies were implemented before the follow-up survey, including aligning board tasks with members’ professional expertise, distributing discussion questions in advance, and transitioning from passive information-sharing to more structured, dialogue-driven meetings. In some cases, subcommittees were created to allow board members to dive deeper into specific strategic topics such as curriculum review or student-industry engagement initiatives. Additionally, meetings were restructured to dedicate time to breakout discussions and feedback loops, allowing board members to observe how their input was being implemented. These efforts not only fostered stronger connections between board members and campus initiatives but also appeared to have contributed to the reported 65% increase in members feeling more engaged after 1 year. Although several suggestions by the board members were implemented following the initial survey, it was difficult to identify which new practices in advisory board management were most impactful since the study examined a limited number of advisory boards at one institution. However, the clarity of board purpose, reinforced by visible and responsive leadership, emerged as a key factor in the perceived effectiveness of these engagement strategies.

This study underscores the need for academic institutions to adopt evidence-based management practices for advisory boards. By drawing upon research in volunteer management and board governance, universities can create a more engaged, motivated, and effective advisory board structure. This, in turn, can lead to more relevant academic programs, stronger industry connections, and a well-prepared workforce.

Implications for practice

Regular surveys informed by prior research on voluntarism are essential for maintaining high levels of engagement and performance among academic advisory board members. Continuous assessment provides valuable feedback that can guide the development of tailored strategies to address gaps in motivation, engagement, and board management. The key best practices include establishing a clear purpose and specific objectives for advisory board members, ensuring that tasks align with their professional expertise, and providing regular feedback on the impact of their contributions.

Leaders should foster a strong sense of connection between the advisory board’s work and the institution’s mission by implementing strategic actions such as structured meetings, providing well-defined roles, offering board members meaningful opportunities to apply their skills, and leveraging their professional networks to create opportunities for students. Additionally, providing a mechanism for advisory board members to regularly reflect on their experiences and see how their input influences university outcomes foster a deeper commitment and a sense of purpose.

While this study focused on animal health academic advisory boards, the findings are broadly applicable to a range of educational settings. For example, technical colleges offering workforce-aligned programs could use these strategies when organizing program-specific advisory boards with clearly defined roles and subcommittees dedicated to curriculum development and employer outreach. Community colleges could implement pre-meeting materials and breakout discussions to deepen industry engagement in certificate or associate degree programs. Graduate programs in professional fields—such as engineering, education, or public health—can benefit by identifying mid-level industry professionals whose skill sets align with course and program objectives and who can serve as guest speakers or provide real-time feedback on course relevance. Institutions can also adapt the feedback loop strategy by sending follow-up communications to advisory board members outlining how their contributions have been implemented—helping foster a sustained sense of purpose and ongoing engagement. These examples illustrate the transferability of the study’s findings to diverse institutional contexts seeking to improve industry-academic collaboration.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Kansas State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the time and thoughtful feedback provided by the advisory board members in completing both surveys associated with this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Carnegie Mellon University. (n.d.). Student academic success center tips for presenting data effectively. Available online at: https://www.cmu.edu/student-success/other-resources/handouts/comm-supp-pdfs/presenting-likert-data.pdf (Accessed March 7, 2024).

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. 7th Edn. New York: Routledge.

Dorazio, P. (1996). Professional advisory boards: fostering communication and collaboration between academe and industry. Bus. Commun. Q. 59, 98–104. doi: 10.1177/108056999605900315

Einolf, C. (2018). Evidence-based volunteer management: a review of the literature. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 9, 153–176. doi: 10.1332/204080518X15299334470348

Ellingson, D. A., Elbert, D. J., and Moser, S. (2010). Advisory councils for business colleges: composition and utilization. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 3, 1–8. doi: 10.19030/ajbe.v3i1.361

Jackson, D. L., and Laanan, F. S. (2015). Desiring to fit: fostering the success of community college transfer students in STEM. Commun. Coll. J. Res. Pract. 39, 132–149. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2012.762565

Kaupins, G., and Coco, M. (2002). Administrator perceptions of business school advisory boards. Education 123, 351–357.

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd Edn. Sage Publications, Inc.

Nagai, J., and Nehls, K. (2014). Non-alumni advisory board volunteers. Innov. High. Educ. 39, 3–16. doi: 10.1007/s10755-013-9257-0

Niebuur, J., Liefbroer, A. C., Steverink, N., and Smidt, N. (2019). The Dutch comparative scale for assessing volunteer motivations among volunteers and non-volunteers: an adaptation of the volunteer functions inventory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:5047. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16245047

Söderlund, L., Spartz, J., and Weber, R. (2017). Taken under advisement: perspectives on advisory boards from across technical communication. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 60, 76–96. doi: 10.1109/TPC.2016.2635693

Keywords: advisory board management, animal health, best practice, academic advisory board, industry-academic collaboration

Citation: Adams AP, Stuteville R and Wolfe BA (2025) Managing and motivating academic advisory boards in animal health for high performance. Front. Educ. 10:1508824. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1508824

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

James Howard Murphy, Anderson University, United StatesCharles F. Harrington, University of South Carolina Upstate, United States

Copyright © 2025 Adams, Stuteville and Wolfe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: A. Paige Adams, YXBhZGFtc0Brc3UuZWR1

†ORCID: A. Paige Adams, http://orcid.org/0009-0006-4524-2654

A. Paige Adams

A. Paige Adams Rebekkah Stuteville

Rebekkah Stuteville