- 1Department of Education, Rey Juan Carlos University, Móstoles, Spain

- 2Department of Basic Education, Universidad de Atacama, Copiapó, Chile

The present work presents a conceptual organization scheme based on the latest research in the field of Citizenship Education for Social Studies. In a globalized world, educational systems must equip students with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to engage proactively in societal issues. Political and social disengagement, particularly among youth experiencing family violence and discrimination, can lead to exclusion and radicalization. School segregation limits the learning of democratic values and harms migrant family participation. Youth tend to favor forms of digital and personal participation over traditional politics. In the digital age, it is crucial to review and adapt civic education, promoting media literacy and the conscious consumption of information. Democratic education should connect knowledge with action to foster active, responsible citizenship, despite the challenge of an academically results-focused environment. To achieve this objective, a literature review was conducted to identify didactics orientations, resulting in a five-dimensional framework: the conceptual dimension advocates for deep and relevant civic education; the participatory dimension encourages active involvement; the prosocial dimension promotes democratic values; the critical dimension develops independent thinking to address inequalities; and the identity dimension strengthens the sense of belonging. These dimensions should be integrated into analog, digital, and immersive contexts to prepare active, critical, and responsible global citizens. This matrix integrates dimensions and contexts to offer better guidance to teachers who impart the subject.

Introduction

The way in which youth assume and include democratic participation in their daily activities is closely connected to the reality of a global society, so much so that they come to identify with the characteristics socially attributed to them as subjects (Peña-Muñante, 2023). This reality influences individuals on economic, political, and cultural levels, and as such, they are conditioned by new global risks such as the climate crisis, poverty, exclusion, and humanitarian crises (Aguilar-Forero et al., 2019).

This socially constructed self, which is addressed in various ways by the educational curricula, exists in a context full of contradictions (Sobarzo Morales, 2019), where democratic values of respect for people and the planet are taught but often questioned in many parts of global society (Pedraja-Rejas and Rodríguez, 2023). Research on the form and intensity of youth democratic participation has paid little attention to the reasons behind the growing disengagement from democratic participation, as well as the need to problematize what is understood by “political” both from the perspective of youth and research (Weiss, 2020). In response to this, recent contributions from youth perspectives (Shultz et al., 2017) advocate for curricular reform starting in primary education, teacher training grounded in critical pedagogy, and the promotion of intergenerational dialogue. These approaches support the development of a reflective pedagogy capable of questioning dominant narratives and underlying power structures, thus enabling a more meaningful and inclusive civic education.

One of the risks most studied as a consequence of political and social disengagement are the phenomena of exclusion and radicalization. In Europe, different processes of extremist radicalization have been identified among youth when macro-contexts of polarization converge with micro-contexts of family violence (Campelo et al., 2018) and social and racial discrimination (Frounfelker et al., 2019). Exclusion and segregation are thus identified as social problems that particularly affect the migrant population, as they incite political debate that polarizes society but also occur within schools and require pedagogical and curricular approach (Sandahl et al., 2022). School segregation limits the ability to extrapolate learning about respect and participation, as the practice of school collaboration occur in homogeneous environments that do not offer the opportunity to empathize with those who are different (Traini, 2022). Similarly, it hinders the participation of migrant families, both in academic monitoring and in school management bodies (Quintas-Quintas et al., 2022).

Young people are more likely to take political action when they have a greater belief that their actions can have political influence, a situation in which democratic education is more effective and useful for political engagement (Levy, 2018). However, the fact that democratic structures are in a process of consolidation as entities, independent of the individuals who constitute the states, is problematic for democratic participation. This issue is exacerbated by factors such as the training of future teachers in active and collective democratic participation, and the presence of elitist and neoliberal discourses in democratic education (Seland and Kjøstvedt, 2024). This explains why young people in Western countries are increasingly less involved in traditional formal politics, such as voting, and prefer more personal and digital forms of political participation, such as protests, petitions, and volunteering (Terhorst et al., 2024).

However, in the current media-saturated context, where political awareness processes arise through social media, there is a risk that democratic and human rights values may be diluted and trivialized (Moreno Vega et al., 2023). This reality demands a revision of civic education adapted to the digital age, incorporating elements already proven effective for democratic education, such as discussing controversial topics, and addressing new forms of discourse circulation and expansion in global society (Kahne et al., 2016). Similarly, media literacy programs enable youth to understand the complex relationship between media, citizenship, and democracy, and the importance of conscious and participatory media consumption in public discourse (Nguyen, 2022).

Democratic values are not acquired automatically by merely living in a democratic society; rather, they must be intentionally taught and practiced within formal educational settings (Yus Ramos, 2022). In this regard, it is essential that educational experiences go beyond a purely local perspective and incorporate a global approach that serves as both a historiographical and pedagogical innovation (Pagès, 2019). Likewise, exercising citizenship requires not only having formal knowledge of how institutions function, but also taking informed action through the connection between knowledge and opportunities to act in the contemporary world (Henderson and Tudball, 2016). A socially responsible citizen is considered one who actively engages with the institutions and policies that shape their environment while exercising their rights (Huamán Pérez et al., 2023).

To avoid discrepancies between reality and the academic content of democratic education, it is crucial that civic participation activities benefit both students and communities. However, maintaining long-term school-community relationships is challenging in the current academic environment, which is oriented toward short-term results (Thomas et al., 2019).

The concept of citizenship is influenced by ideological differences regarding this concept. These ideologies are present in socially established institutions and in what is commonly understood as “common sense,” and depending on the dominance and hegemonic relations, they take on a republican, liberal, or critical character (Abowitz and Harnish, 2006). There is a risk of being accused of indoctrination or political bias due to the tension in the political climate (Pollock and Rogers, 2022).

More than two decades have passed since Westheimer and Kahne (2004) proposed their typology of civic engagement—distinguishing the responsible, participatory, and justice-oriented citizen—and since Schattle (2008) examined the ideological tensions surrounding the emergence of the concept of global citizenship, a broad framework that ranged from socially oriented approaches emphasizing care for people and the environment to those aligned with the principles of global free-market capitalism. In this context, it is timely to revisit these categories through the lens of more radical theoretical frameworks (Shultz, 2007). This review focuses on the analysis of studies concerning educational practices related to Global Citizenship Education, from a contemporary critical-postcritical perspective (Pashby et al., 2020), within a global landscape profoundly shaped by technologies that, far from being neutral, tend to reproduce and even deepen structures of oppression and inequality.

Currently, digital citizenship literacy programs are reported to be effective in enhancing students’ research, questioning, and critical thinking abilities (İmer and Kaya, 2020; Witarsa and Muhammad, 2023). Nevertheless, this remains an ongoing challenge, as it is a constantly evolving context, with a developing conceptualization of digital and media literacy, alongside the parallel growth in digital rights, regulatory systems, personal protection procedures, and forms of online participation (Pangrazio and Sefton-Green, 2021).

Ultimately, the political and social disengagement of young people, along with exclusion and radicalization, require an educational response that promotes inclusion and active participation, especially in contexts of violence and discrimination. School segregation and the lack of participation of migrant families are significant barriers. Additionally, digitalization and media consumption demand media literacy to promote critical thinking and civic awareness. Civic education must adapt to new forms of digital and personal participation, avoiding the trivialization of democratic values. There is a need for a pedagogical approach that connects knowledge with action and promotes social responsibility, highlighting the importance of long-term relationships between schools and communities, considering the ideological differences in the concept of citizenship. Digital citizenship literacy programs have proven effective, but they must evolve with technological and social changes.

Methods

The aim of this paper is to establish a combined matrix between types of Global Citizenship Education school work and technological contexts that offers didactic guidelines for the field of Global Citizenship Education. To achieve this, the study conducts a qualitative analysis of how young people engage in prosocial behavior and democratic participation, with special attention to the role of technology in these processes. In this context, prosocial behavior refers to actions that contribute positively to civic life and community well-being, placing human rights above any state, legal or national considerations. The analysis focused on the textual content of studies relevant to civic education and global citizenship. Although a quantitative approach was used only to select a sample of relevant literature, the core methodology for analyzing the studies was qualitative in nature.

Regarding the sample selection, the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021) was used. Inclusion criteria considered studies published in scientific journals between 2020 and 2024 indexed in the Web of Science and Dialnet databases. Exclusion criteria included studies that were not open access, not in English, Spanish, or Portuguese languages, and those that were not directly related to the educational field.

The following equation was used for information search: (“participación democrática” OR “democratic participation” OR “civic engagement”) AND (“educación para la ciudadanía” OR “citizenship education” OR “civic education”).

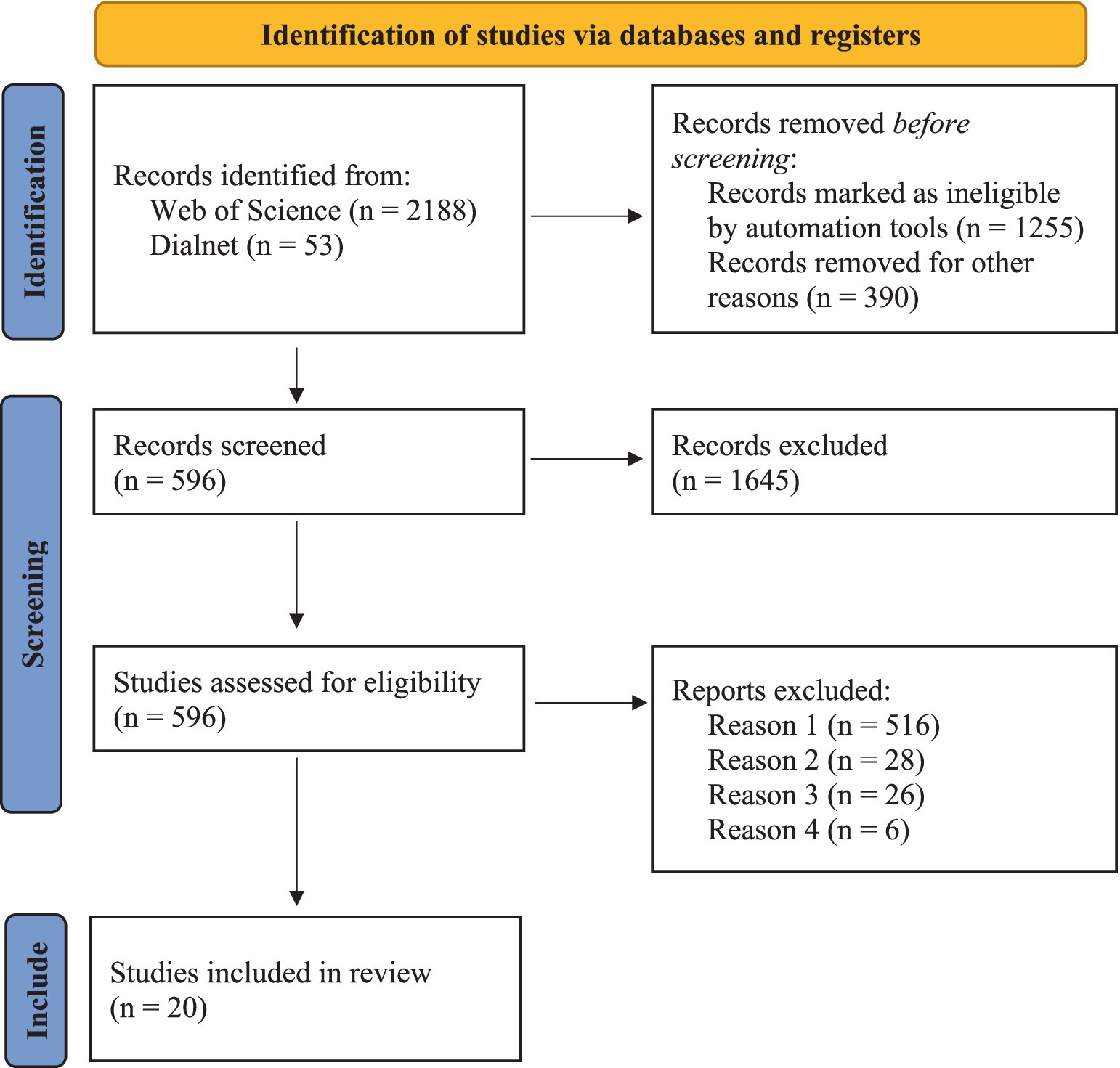

The initial search yielded a total of 2,188 results in the Web of Science database and 53 in Dialnet, for a combined total of 2,241 studies. However, not all of these publications were relevant or suitable for inclusion. To refine the sample, a series of inclusion and exclusion criteria were systematically applied. First, a total of 1,255 studies were excluded because they were published before 2020, as the review was specifically focused on capturing the most recent scholarly contributions to the field of Global Citizenship Education (GCE). Subsequently, 390 publications that were not journal articles were excluded. The category was then refined to choose those that belonged to the Educational Research Category, thereby excluding a total of 516 (reason 1). Another 28 publications were discarded for lacking a direct and substantive connection with the thematic focus of the study, as they either addressed civic education in general or used the term “global citizenship” in a metaphorical or marginal way (reason 2). Finally, 26 studies were excluded due to restricted access, as they were not available in open access format—an essential criterion to ensure transparency, replicability, and equitable access to academic knowledge (reason 3).

Following this process, and after the removal of all irrelevant or inaccessible studies, the final sample consisted of 26 studies. Duplicate records across both databases were identified and removed, resulting in the elimination of 6 studies (reason 4). These publications provide the foundation for the present analysis, offering a thematically focused, up-to-date overview of educational practices and critical perspectives shaping the field of GCE between 2020 and 2024. The review process was conducted by both authors through peer consensus to ensure rigor and consistency in the selection and analysis of the studies.

Regarding the qualitative analysis, ATLAS.ti software was used to conduct a conceptual and categorical systematization of the sample to establish a matrix of the types and levels of prosocial behavior and democratic participation. The work is inductive in nature, identifying and organizing the most relevant codes found in the selected sample of studies to provide a structured and hierarchical coding framework to the existing literature. This will allow for the identification of the conceptual components of Democratic Education according to recent research, thereby delineating areas of interest and significance for future investigations.

Results

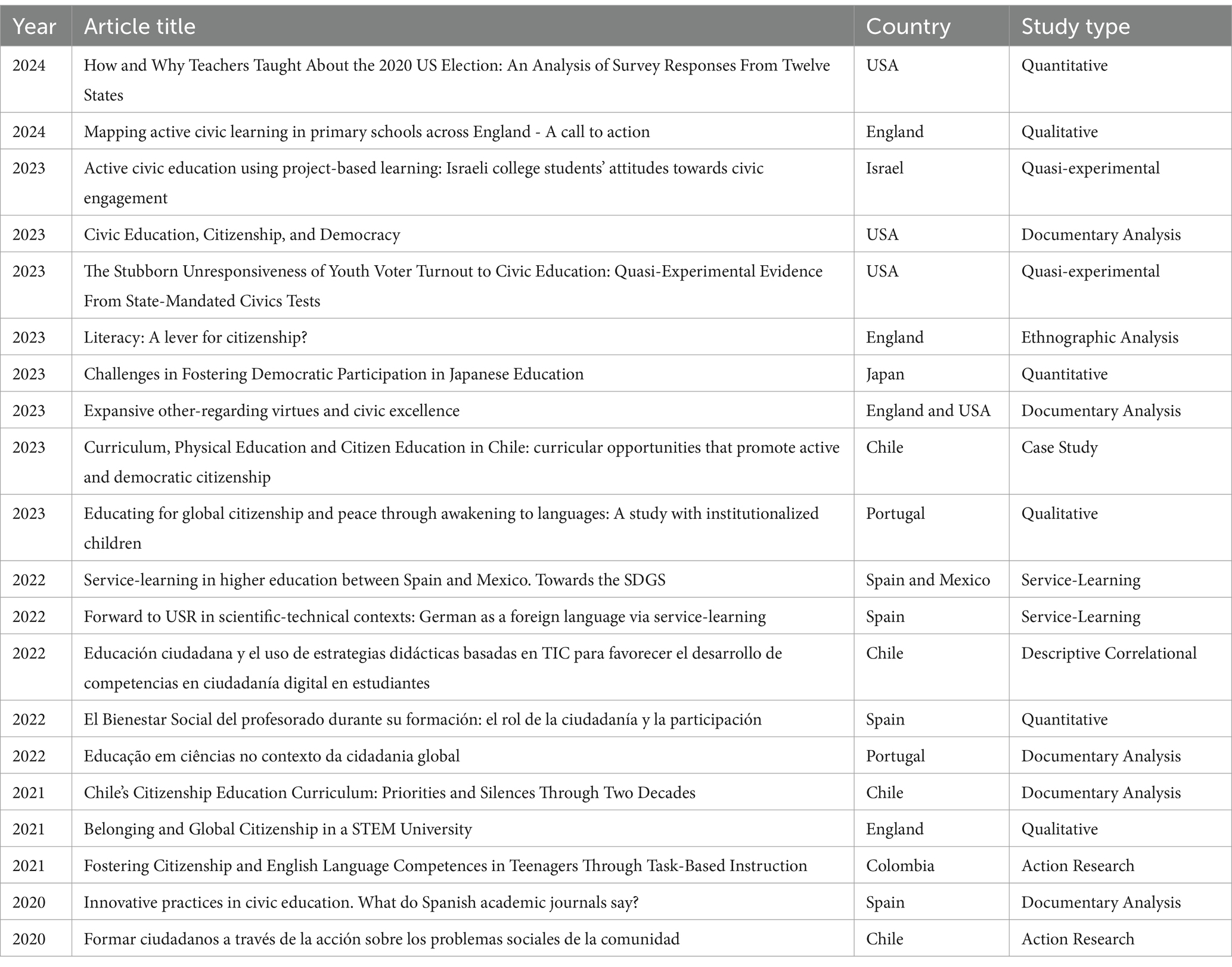

As shown in Table 1, the sample predominantly includes research conducted in the Ibero-American context (45%), followed by studies of Anglo-Saxon origin (35%), and to a lesser extent, from Portugal (10%), Israel (5%), and Japan (5%). Regarding the methodology used in these studies, there is greater variety, with documentary analysis being the most prominent (25%).

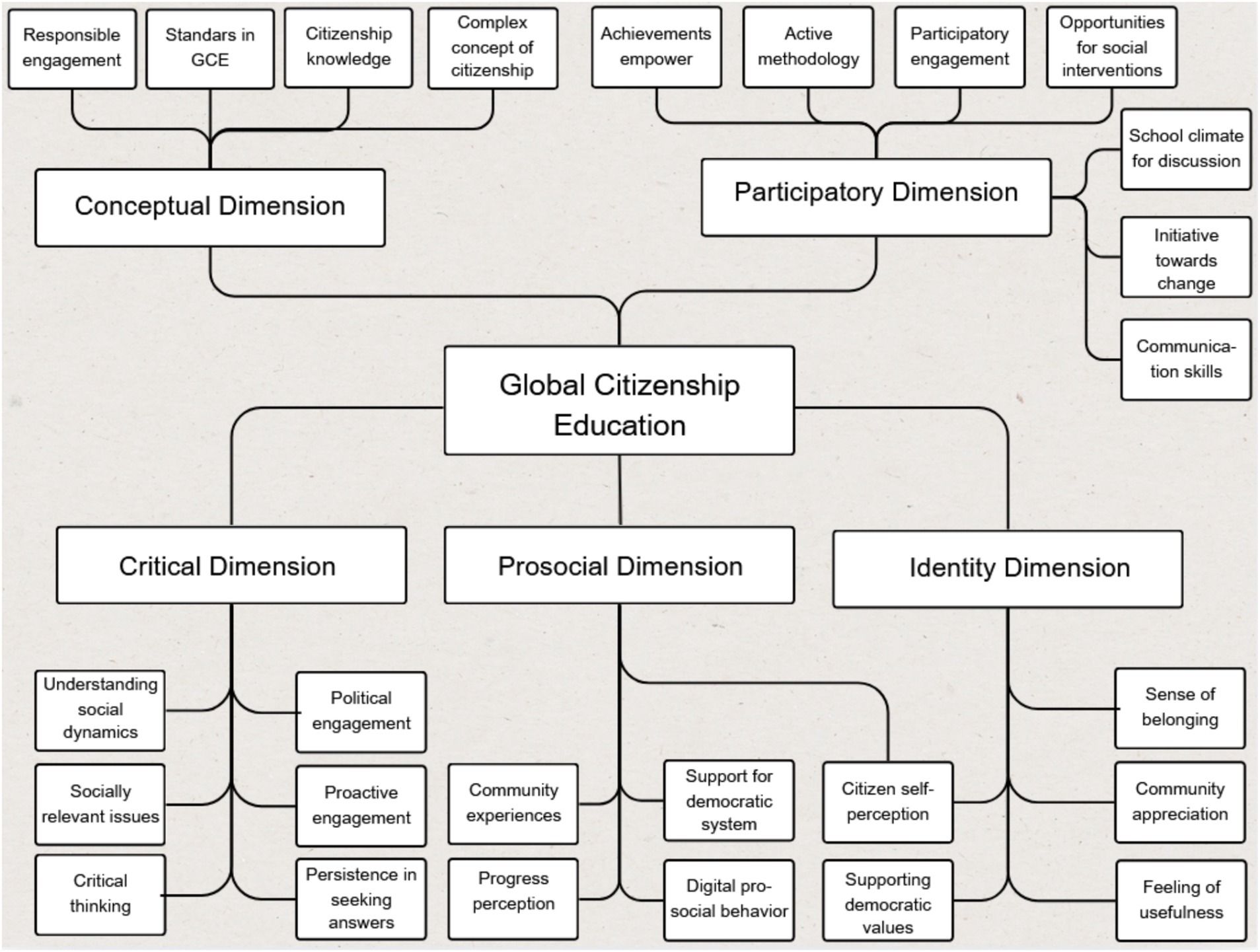

Once the analysis of the documents comprising the sample is completed and the main concepts are identified, categorization is performed. As shown in Figure 1, given the complexity of the approach to the issue and to meet the research objective of establishing a matrix to structure and guide Citizenship Education, up to five different dimensions are proposed to articulate it. Concepts are color-coded based on density and foundation (Figure 2).

Discussion of the results

Next, the categories and dimensions of analysis found in the documents of the sample are developed, ultimately proposing a matrix based on the identified dimensions and the different contexts in which they manifest.

Conceptual dimension

The starting point for the conceptual problematization of citizenship lies in the discrepancy between the orientations of academic research and formal educational practices (Rodrigues, 2022). The concept of citizenship is complex and uniquely influenced by the political and historical context of each country (Anderson, 2023), a historical moment where mere literacy is insufficient to achieve the knowledge, skills, and attitudes expected of an active global citizenship integrated into modern societies (Robinson-Pant, 2023). This complexity is particularly intense in heterogeneous societies where youth are socialized in segregated schools (Akirav, 2023), or in environments with high political polarization and structural discrimination (Jung and Gopalan, 2023).

Additionally, globalization phenomena (Body et al., 2024) and the digitalization of society (Contreras Pardo and Vera Sagredo, 2022) add new layers of complexity to the concept of citizenship. However, what appears to be an obstacle to addressing the concept of citizenship is in fact an opportunity to transfer through the concept of global citizenship a debate that is more difficult to encourage and understand in more homogeneous societies or national contexts (Nonoyama-Tarumi, 2023).

In these increasingly connected and diverse societies, there is a noticeable lack of a clear model of the type of global citizenship being pursued (Arroyo Mora et al., 2020), which leads to offering different levels of opportunity, security, and rights for citizenship (Akirav, 2023). Traditional knowledge in civic education, which is focused on understanding democratic institutions, their structures, and their history, has led to a disconnection between civic education and the relevance of democratic participation (Jung and Gopalan, 2023), remaining distant from the commitments of global citizenship (Robinson-Pant, 2023). This type of citizenship is constituted as personally responsible (Arroyo Mora et al., 2020), capable of effectively accessing necessary information (Contreras Pardo and Vera Sagredo, 2022; Jung and Gopalan, 2023), and empowered to defend its rights and exercise its duties (Anderson, 2023; Rodrigues, 2022) through traditional civic education knowledge (Fitchett et al., 2024), but lacks the necessary skills to be socially responsible. In some cases, this education was limited to mere general literacy, based on evidence indicating a positive correlation between literacy and civic engagement (Robinson-Pant, 2023).

This circumstance coincides with a historical moment in which the most educated generation of young people is distancing itself from political participation (Cox and García, 2021). Voting is commonly identified as the most important element of civic participation; however, the level of knowledge about democratic functioning is insufficient to explain the political engagement of youth, as evidenced by their electoral participation rates (Jung and Gopalan, 2023).

It is also important not to overlook the influence of teachers’ methodological choices when designing the didactic model used to teach civic education. Methodological choices between a knowledge-centered approach and a participation-centered approach have an ideological influence that oscillates on the conservative-progressive axis (Fitchett et al., 2024).

Participatory dimension

Overcoming the conceptual limitation of Global Citizenship Education as merely a conceptual construct leads to an initial differentiation between curricular knowledge, support for democratic values, identification with the democratic political system (Arroyo Mora et al., 2020), and participation in democratic spaces and processes. Specifically, these elements are related to representative democracy, such as voting in school environments, participating in deliberative spaces, or demanding that commitments be fulfilled (Cox and García, 2021), where teachers and students are agents participating in the democratic dialectic (González Alonso et al., 2022). All of this serves as a way to ultimately participate in formal political spaces (Fitchett et al., 2024).

Thus, knowledge, awareness, and capacity for discussion emerge as general descriptors of the achievement level that students can reach in the field of Global Citizenship Education (Akirav, 2023). This is further complemented by the development of favorable attitudes toward democracy (Albalá Genol and Maldonado Rico, 2022) and critical thinking (Anderson, 2023) in the analysis of the information received.

Democratic participation is a factor of social well-being among young people (Albalá Genol and Maldonado Rico, 2022) who at early stages are predisposed to adopting prosocial behaviors (Body et al., 2024). This involves the incorporation of active methodologies such as cooperative games that establish a dialogical-democratic relationship (Garrido, 2023). It also involves efforts to create school environments conducive to debate (Akirav, 2023), although this can be a challenge for teachers in contexts with wide ideological differences among students in the classroom (Fitchett et al., 2024). Ultimately, it is about creating a school climate that allows explaining what democracy is in spaces where students can express themselves freely (Nonoyama-Tarumi, 2023) and debate issues that relevant to their context or global citizenship (Viola, 2021).

Intervention and democratic participation in the social life of the local community (González Alonso et al., 2022) represent the most suitable context for action due to their proximity and ease of identification with real-life problems (Salinas Valdés and Oller Freixa, 2020). However, opportunities provided to students for social intervention through formal education are very limited (Akirav, 2023; Anderson, 2023; Arroyo Mora et al., 2020). In this sense, Service-Learning experiences emerge as activities that mutually benefit students and their community, illustrating how such intervention can be fostered (Body et al., 2024).

Empowering students to become agents of change involves not only providing them with the necessary knowledge and skills to participate in democratic life but also creating opportunities for them to apply what they have learned.

Community service projects and student participation initiatives can be effective tools for empowering young people and make them feel capable of influencing their environment. Successfully engaging in social intervention activities has great potential to empower citizenship (Akirav, 2023), establishing a connection between knowledge, values, and democratic participation. This allows students to develop communicative skills (Body et al., 2024; Romero and Pérez, 2021) through discussions and debates (Salinas Valdés and Oller Freixa, 2020), as well as greater confidence in their ability to influence democratic processes and increased motivation to continue participating in civic life.

The same principles can be applied to digital contexts, which have had a significant impact on civic engagement and political participation (Cox and García, 2021). These are newly formed spaces where students can participate in civic movements which are characteristic of a digital community (Contreras Pardo and Vera Sagredo, 2022).

Prosocial dimension

The main element of this dimension rests on the support for democratic values (Anderson, 2023). Global Citizenship Education is linked to democratic values (Silva and Lourenço, 2023), such as respect for human rights (Byerly and Haggard, 2023), environmental responsibility (Gil Salom, 2022), the adoption of a culture of peace (Silva and Lourenço, 2023), as well as freedom, equity, social justice, and the common good (Cox and García, 2021). The ultimate goal of acquiring these values is to have a citizenry committed to promoting and defending democracy (Rodrigues, 2022).

The promotion of prosocial behavior begins with recognizing the value of life in a global society. Acquiring such behavior, in addition to being beneficial to society, allows the individual to develop a sense of belonging that stimulates an understanding of the dynamics occurring in their environment, and reinforces the idea that societies progress towards achieving common goals (Albalá Genol and Maldonado Rico, 2022). In this sense, immersive methodologies such as role-playing or political simulation games (Body et al., 2024) foster a dialectical understanding of social dynamics.

These type of positive interactions with the context fosters a prosocial attitude and identification with humanity (Byerly and Haggard, 2023), which also extends to global prosocial behavior in digital environments (Contreras Pardo and Vera Sagredo, 2022). Promoting prosocial behavior in digital environments is crucial for building more responsible and respectful online communities (Romero and Pérez, 2021). Such communities support participation in digital awareness spaces, collaboration in online social projects, and addressing challenges such as misinformation or cyberbullying.

Critical dimension

From the perspective of active student engagement within the classroom, it is also important to identify problematic situations related to school or community issues (Salinas Valdés and Oller Freixa, 2020) in order to find solutions through dialogue and collective effort (Romero and Pérez, 2021). This requires a deeper look to identify the structural elements that lead to the reproduction and perpetuation of violence, inequality, and poverty (Silva and Lourenço, 2023), and a positive attitude towards politics (Akirav, 2023).

Therefore, it represents a concept of global citizenship persistently oriented towards social justice (Arroyo Mora et al., 2020). The critical dimension demands persistent responses to social problems (Akirav, 2023), where perseverance turns political motivations into real social participation (Jung and Gopalan, 2023).

Likewise, there is an intention to consciously promote critical thinking (Body et al., 2024) capable of critically assessing all the information received in both analog and digital environments (Contreras Pardo and Vera Sagredo, 2022). In this way, the development of independent thinking by students (Anderson, 2023) is understood as one of the elements necessary for global citizenship (Body et al., 2024).

Working with controversial elements of adult life (Body et al., 2024) enables students to critically analyze public policies, their impact, and how they can participate and influence aspects of daily life that are of public interest. Understanding the characteristics of these socially relevant issues leads to an understanding of the implications of decisions that shape societal structures (Byerly and Haggard, 2023), beyond the democratic functioning of institutions, aiming actions towards an attitude of social transformation (Silva and Lourenço, 2023).

This dimension prepares students for a political attitude (Anderson, 2023), developing their capacity for political participation (Cox and García, 2021), and understanding the importance of seeking collective action (Body et al., 2024) aimed at social transformation (Silva and Lourenço, 2023) and any other topics of interest to them (Fitchett et al., 2024). As with other dimensions, the digital context has driven much of citizen political activism, seeking such collective action online (Byerly and Haggard, 2023) and requiring specific training on how to channel the political will of youth through digital means (Contreras Pardo and Vera Sagredo, 2022).

However, there is a tendency detected to avoid these issues in the classroom, partly due to self-imposed caution in polarized societies where educators may be accused of teaching in a biased or manipulated manner (Fitchett et al., 2024).

Identity dimension

Finally, literature points to an identity dimension as a relevant element, starting from local contexts and moving towards broader levels (Viola, 2021). This is primarily done through the idea of a sense of belonging (Rodrigues, 2022) to avoid the exclusion associated with alienation. This serves as a way to socialize within a common civic culture (Body et al., 2024).

This dimension aims to generate a sense of belonging that acts as a catalyst for civic participation (Akirav, 2023; Albalá Genol and Maldonado Rico, 2022), as a means of socialization (Body et al., 2024), and as a means of integration into culture (Arroyo Mora et al., 2020). Participation enables citizens to feel useful to society (Albalá Genol and Maldonado Rico, 2022), to have the capacity to influence political decisions (Fitchett et al., 2024), and to perceive their role in the collective as purposeful (Nonoyama-Tarumi, 2023).

When individuals perceive and identify themselves as part of a group (Byerly and Haggard, 2023), they are more motivated to contribute to the common good and engage with their community’s issues. In the case of promoting global citizenship, the key lies in self-identification with a collective that encompasses all humanity from a historical perspective (Viola, 2021).

Educational experiences that promote democratic values such as freedom, diversity, equity, or the common good (Cox and García, 2021) make individuals feel as an integral part of a community to which they belong, respect, and for which they take responsibility.

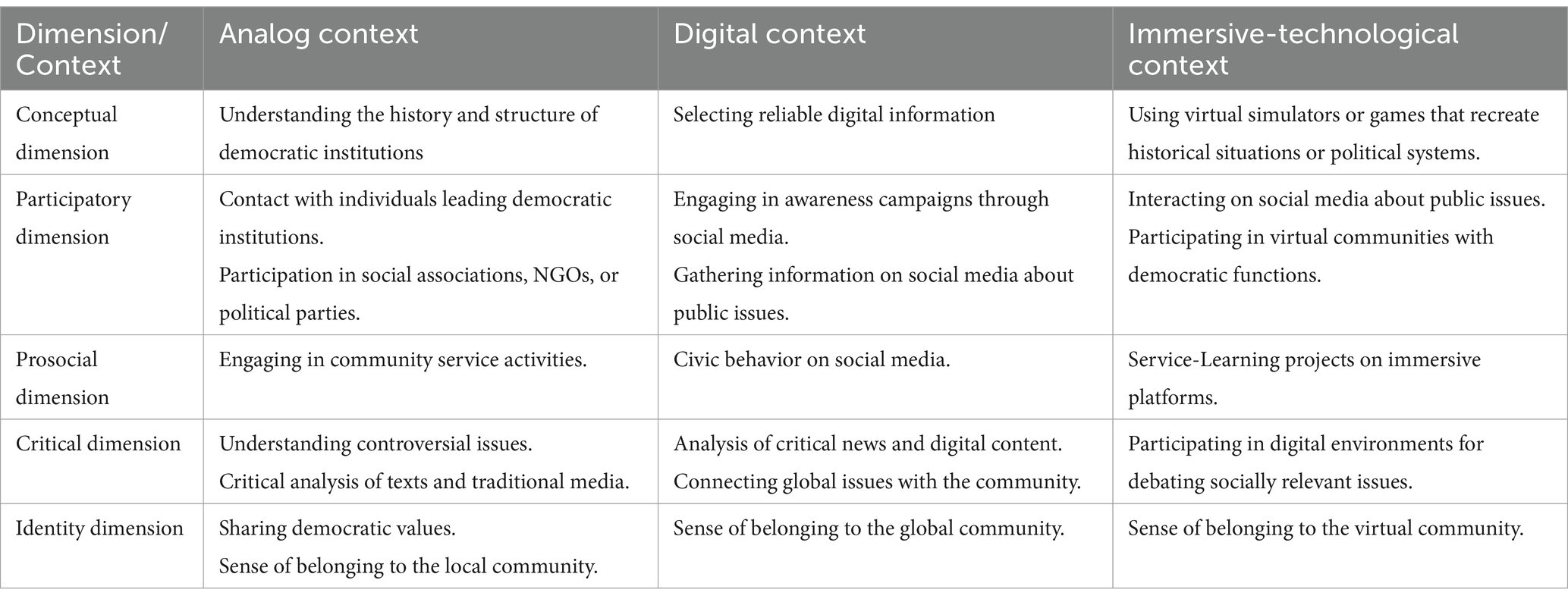

Matrix proposal

Based on the results of this review and the analysis of the dimensions of Citizenship Education, as well as the global multi-contextual reality in which today’s youth operates, as established within the theoretical framework, the following matrix (Table 2) is proposed as a guide to Citizenship Education.

Conclusion

In establishing an analysis of dimensions and contexts for Global Citizenship Education, it is necessary to update the model proposed by Westheimer and Kahne (2004). Although foundational, this model has been revised from a critical perspective (Shultz, 2007) that has given way to current currents on GCED that attempt to place the theoretical and practical framework outside the modern and colonial imaginary to address current civic challenges without the tutelage of the mainstream vision of the Global North (Pashby et al., 2020). In this sense, the limitations of this study’s analysis lie in the contradictions of establishing decontextualized didactic orientations for a world that is diverse and tends to minimize the perspectives of the Global South (Andreotti, 2021). Another limitation is that only open access texts were reviewed, which may lead to selection bias by excluding relevant studies behind paywalls.

Under these considerations, several key dimensions emerge from the reviewed studies that should be taken into account: conceptual, participatory, prosocial, critical and identity. These dimensions reflect the complexity and diversity of citizenship, influenced by specific political and historical contexts and exacerbated by globalization and digitalization. The conceptual dimension emphasizes the need to redefine civic education beyond basic literacy, encompassing a deep understanding of democratic institutions and their relevance in democratic participation. In heterogeneous societies with segregated schools and high political polarization, it is vital to provide education that promotes globally conscious and socially responsible citizenship.

Regarding the participatory dimension, it is crucial to go beyond the mere transmission of knowledge. Citizenship education should foster active participation in democratic spaces and provide active methodologies that promote democratic awareness and critical skills. Direct contact with individuals leading democratic institutions and participation in associations or political parties, both in analog and digital contexts, are essential to empower students and connect academic knowledge with democratic practice.

The prosocial dimension focuses on fostering democratic values such as peace, human rights, and social justice. These values should be instilled through immersive methodologies and the responsible use of digital environments, facilitating the adoption of prosocial behaviors in both local and global contexts. Community service activities and Service-Learning projects on immersive platforms are effective examples of how active and engaged citizenship can be promoted.

In the critical dimension, it is fundamental to develop students’ ability to identify and critically analyze problematic and structural situations that perpetuate inequality and poverty. This involves promoting education oriented towards social justice and fostering independent and critical thinking. Participation in debates on public policies and socially relevant issues should be encouraged in both analog and digital environments, preparing students for a political attitude and social transformation.

The identity dimension underscores the importance of building a sense of belonging to foster civic participation. This sense of belonging to local and global communities motivates individuals to contribute to the common good and actively participate in democratic life. Educational experiences that promote democratic values and a sense of belonging to broader communities, including virtual ones, are essential for integrated and responsible citizenship.

Considering the educational model of democratic participation and Digital Citizenship Education, it is possible to enrich the existing knowledge by providing new empirical data, identifying best practices, improving theoretical understanding, and fostering innovation in education. It is necessary to explore the elements that motivate youth to participate in democratic spaces, especially in digital and immersive technological environments. It is crucial to question whether it is more effective to enhance formal knowledge of democratic functioning or to establish digital and immersive participation experiences that connect democratic values with issues in both physical and virtual communities. To determine which approach is more motivating can help foster prosocial citizenship and responsibility towards the common good.

The proposed matrix integrates these dimensions into different educational contexts: analog, digital, and immersive-technological. In the analog context, elements such as knowledge of the history and structure of democratic institutions, contact with individuals leading these institutions, and community service activities are addressed. In the digital context, the importance of selecting reliable information, participating in awareness campaigns, and behaving civically on social media platforms is highlighted. In the immersive-technological context, the use of virtual simulators, participation in democratic virtual communities, and Service-Learning projects on immersive platforms are promoted.

This matrix provides a framework to guide civic and citizenship education in an era of increasing interconnection and diversity, equipping students with the necessary tools to become active, critical, and socially responsible citizens. By updating the Westheimer and Kahne model and considering new realities and challenges, education that adequately responds to the needs and aspirations of today’s youth can be fostered.

Author contributions

PM-M: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. CB: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abowitz, K. K., and Harnish, J. (2006). Contemporary discourses of citizenship. Rev. Educ. Res. 76, 653–690. doi: 10.3102/00346543076004653

Aguilar-Forero, N., Mendoza Torres, D. F., Velásquez, A. M., Espitia, D. F., Ducón Pardey, J., and De Poorter, J. (2019). Educación para la Ciudadanía Mundial: Una Innovación Curricular en Ciencias Sociales. Revista Int. Educ. Justic. Soc. 8:89. doi: 10.15366/riejs2019.8.2.005

Akirav, O. (2023). Active civic education using project-based learning and attitudes towards civic engagement. Int. J. Problem Based Learn. 17, 1–14. doi: 10.14434/ijpbl.v17i1.32354

Albalá Genol, M. Á., and Maldonado Rico, A. F. (2022). The social well-being of teachers during their training: the role of citizenship and participation. Int. J. Sociol. Educ. 11, 128–150. doi: 10.17583/rise.8975

Anderson, L. W. (2023). Civic education, citizenship, and democracy. Educ. Policy Analysis Archives 31, 1–16. doi: 10.14507/epaa.31.7991

Andreotti, V. D. O. (2021). Depth education and the possibility of GCE otherwise. Glob. Soc. Educ. 19, 496–509. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2021.1904214

Arroyo Mora, E., Crespo Torres, B., Mancha Castro, J. C., and Schugurensky, D. (2020). Prácticas innovadoras en educación ciudadana. ¿Qué dicen las revistas académicas españolas? Revista Fuentes 2, 212–223. doi: 10.12795/revistafuentes.2020.v22.i2.09

Body, A., Lau, E., Cunliffe, J., and Cameron, L. (2024). Mapping active civic learning in primary schools across England—a call to action. Br. Educ. Res. J. 50, 1308–1326. doi: 10.1002/berj.3975

Byerly, T. R., and Haggard, M. (2023). Expansive other-regarding virtues and civic excellence. J. Moral Educ. 52, 95–107. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2022.2117143

Campelo, N., Oppetit, A., Neau, F., Cohen, D., and Bronsard, G. (2018). Who are the European youths willing to engage in radicalisation? A multidisciplinary review of their psychological and social profiles. Eur. Psychiatry 52, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.03.001

Contreras Pardo, C. M. J., and Vera Sagredo, A. (2022). Educación ciudadana y el uso de estrategias didácticas basadas en TIC para favorecer el desarrollo de competencias en ciudadanía digital en estudiantes. Cuadernos Investig. Educ. 13, 1–24. doi: 10.18861/cied.2022.13.2.3195

Cox, C., and García, C. (2021). Chile’s citizenship education curriculum. Encounters Theory History Educ. 22, 206–226. doi: 10.24908/encounters.v22i0.14991

Fitchett, P. G., Levy, B. L. M., and Stoddard, J. D. (2024). How and why teachers taught about the 2020 U.S. election: an analysis of survey responses from twelve states. AERA Open 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/23328584241234884

Frounfelker, R. L., Frissen, T., Vanorio, I., Rousseau, C., and d’Haenens, L. (2019). Exploring the discrimination–radicalization nexus: empirical evidence from youth and young adults in Belgium. Int. J. Public Health 64, 897–908. doi: 10.1007/s00038-019-01226-z

Garrido, J. P. R. (2023). Currículum, Educación Física y Formación Ciudadana en Chile: Oportunidades curriculares que promueven una ciudadanía activa y democrática. Educ. Física Ciencia 25:e275. doi: 10.24215/23142561e275

Gil Salom, D. (2022). Forward to USR in scientific-technical contexts: German as a foreign language via service-learning. Revista Docencia Universitaria 20, 187–204. doi: 10.4995/redu.2022.16053

González Alonso, F., Ochoa Cervantes, A., and Guzón Nestar, J. L. (2022). Aprendizaje servicio en educación superior entre España y México. Hacia ODS Alteridad 17, 76–88. doi: 10.17163/alt.v17n1.2022.06

Henderson, D. J., and Tudball, E. J. (2016). Democratic and participatory citizenship: youth action for sustainability in Australia. Asian Educ. Develop. Stud. 5, 5–19. doi: 10.1108/AEDS-06-2015-0028

Huamán Pérez, F., Churampi Cangalaya, R. L., and Poma Castellanos, G. (2023). Ciudadanía socialmente responsable: Caso Red Interquorum Junín-Perú. Estudios Desarrollo Social 10, 289–299.

İmer, G., and Kaya, M. (2020). Literature review on digital citizenship in Turkey. Int. Educ. Stud. 13:6. doi: 10.5539/ies.v13n8p6

Jung, J., and Gopalan, M. (2023). The stubborn unresponsiveness of youth voter turnout to civic education: quasi-experimental evidence from state-mandated civics tests. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1–49. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/fzjhu

Kahne, J., Hodgin, E., and Eidman-Aadahl, E. (2016). Redesigning civic education for the digital age: participatory politics and the pursuit of democratic engagement. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 44, 1–35. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2015.1132646

Levy, B. L. M. (2018). Youth developing political efficacy through social learning experiences: becoming active participants in a supportive model United Nations Club. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 46, 410–448. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2017.1377654

Moreno Vega, B., Arias Medina, L., and Benavides Vásquez, W. (2023). Política y redes sociales: El sentido del sinsentido. Uru: Revista de Comunicación y. Des. Cult. 8, 6–23. doi: 10.32719/26312514.2023.8.1

Nguyen, V. T. (2022). Citizenship education: a media literacy course taught in Japanese university. Citizenship Soc. Econ. Educ. 21, 43–60. doi: 10.1177/20471734211061487

Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y. (2023). Challenges in fostering democratic participation in Japanese education. Education Policy Analysis Archives 31, 1–19. doi: 10.14507/epaa.31.7996

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 74, 790–799. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Pagès, J. (2019). Ciudadanía global y enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales: Retos y posibilidades para el futuro. Revista Investig. Didáctica Ciencias Soc. 5, 5–22. doi: 10.17398/2531-0968.05.5

Pangrazio, L., and Sefton-Green, J. (2021). Digital rights, digital citizenship and digital literacy: What’s the difference? J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 10, 15–27. doi: 10.7821/naer.2021.1.616

Pashby, K., Da Costa, M., Stein, S., and Andreotti, V. (2020). A meta-review of typologies of global citizenship education. Comp. Educ. 56, 144–164. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2020.1723352

Peña-Muñante, G. S. (2023). La construcción social del yo. Razón Crítica, 15, 1–3. doi: 10.21789/25007807.1965

Pedraja-Rejas, L., and Rodríguez, C. (2023). Desarrollo de habilidades del pensamiento crítico en educación universitaria: Una revisión sistemática. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 29, 494–516.

Pollock, M., and Rogers, J. (2022). “The conflict campaign: exploring local experiences of the campaign to ban “critical race theory”” in Public K–12 Education in the U.S. UCLA, University of California Publications.

Quintas-Quintas, M., Arratibel Insausti, N., and Barquín, A. (2022). Participación Familiar en Escuelas con Alta Presencia de Alumnado Inmigrante y en Desventaja Socioeconómica. REICE 20, 89–105. doi: 10.15366/reice2022.20.4.005

Robinson-Pant, A. (2023). Literacy: a lever for citizenship? Int. Rev. Educ. 69, 15–30. doi: 10.1007/s11159-023-09998-6

Rodrigues, M. J. (2022). Educação em ciências no contexto da cidadania global La educación científica en el contexto de la ciudadanía global. RELAdEI 11, 12–23.

Romero, Y., and Pérez, A. (2021). Fostering citizenship and English language competences in teenagers through task-based instruction. Profile 23, 103–120. doi: 10.15446/profile.v23n2.90519

Salinas Valdés, J. J., and Oller Freixa, M. (2020). Educate citizens through take action on community problems. Praxis Educ. 24, 1–14. doi: 10.19137/praxiseducativa-2020-240110

Sandahl, J., Tväråna, M., and Jakobsson, M. (2022). Samhällskunskap (social science education) in Sweden. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 21, 85–106. doi: 10.11576/JSSE-5339

Schattle, H. (2008). Education for global citizenship: illustrations of ideological pluralism and adaptation. J. Polit. Ideol. 13, 73–94. doi: 10.1080/13569310701822263

Seland, I., and Kjøstvedt, A. G. (2024). How do teacher educators from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden teach for active democratic participation? Scand. J. Educ. Res. 69, 607–622. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2024.2322967

Shultz, L. (2007). Educating for global citizenship: conflicting agendas and understandings. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 53, 248–258. doi: 10.55016/ojs/ajer.v53i3.55291

Shultz, L., Pashby, K., and Godwaldt, T. (2017). Youth voices on global citizenship: deliberating across Canada in an online invited space. Int. J. Develop. Educ. Global Learn. 8, 5–17. doi: 10.18546/IJDEGL.8.2.02

Silva, V., and Lourenço, M. (2023). Educating for global citizenship and peace through awakening to languages: a study with institutionalised children. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria Didáctica Lenguas Extranjeras 40, 181–197. doi: 10.30827/portalin.vi40.26655

Sobarzo Morales, M. (2019). Filosofía, escuela y democracia ¿Cómo pensamos el aprendizaje de la ciudadanía hoy? Revista Enfoques Educacionales 16, 1–14. doi: 10.5354/2735-7279.2019.66519

Terhorst, C., Rommes, E., Van Den Bogert, K., and Verharen, L. (2024). The everyday civic engagement of social work students. Soc. Work. Educ. 43, 2975–2991. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2024.2308681

Thomas, A., Stupples, P., Kiddle, R., Hall, M., and Palomino-Schalscha, M. (2019). Tensions in the ‘tent’: Civic engagement in Aotearoa New Zealand universities. Power and Education, 11, 96–110. doi: 10.1177/1757743819828398

Traini, C. (2022). The stratification of education systems and social background inequality of educational opportunity. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 63, 10–29. doi: 10.1177/00207152211033015

Viola, J. K. (2021). Belonging and global citizenship in a STEM university. Educ. Sci. 11:803. doi: 10.3390/educsci11120803

Weiss, J. (2020). What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:1. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.00001

Westheimer, J., and Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 41, 237–269. doi: 10.3102/00028312041002237

Witarsa,, and Muhammad, S. (2023). Critical thinking as a necessity for social science students capacity development: How it can be strengthened through project based learning at university. Front. Educ. 7 doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.983292

Keywords: social studies, democratic participation, civic engagement, citizenship education, global citizenship

Citation: Mellado-Moreno PC and Burgos C (2025) Didactics in social studies for global citizenship education: dimensions and technological contexts. Front. Educ. 10:1514027. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1514027

Edited by:

Isabel Menezes, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Almerindo Janela Afonso, University of Minho, PortugalAnatoli Rapoport, Purdue University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Mellado-Moreno and Burgos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pedro C. Mellado-Moreno, cGVkcm8ubWVsbGFkb0B1cmpjLmVz

Pedro C. Mellado-Moreno

Pedro C. Mellado-Moreno Carmen Burgos

Carmen Burgos