- 1Department of Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gandhinagar, India

- 2Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gandhinagar, India

The shape of classroom and learning in higher education has transformed during the COVID-19 pandemic in a way of increasing learners' socialization and connectedness in the virtual setting. This study examines 4 years' work of design, development, and refinement for a two-semester-long undergraduate first-year writing (FYW) course during and after the pandemic, throughout the transition from online to offline mode in India. Undergraduate FYW courses in India have multiple functions such as learning English as a second language and academic/social integration, and they were placed in an optimal position to compensate the lack of physical interactions and socialization during the pandemic. First, we discuss three designing principles that have been constant from the establishment of the curriculum: authentic learning with digital literacy, maximizing socialization, and empowering students' voice. Second, an online survey was conducted to measure students' perception and perspective on their adapted learning environments—online only, mostly online, mostly offline, and offline only conditions. The results indicate that the offline mode was overall more satisfactory for writing practice and learning, while some functions in the online mode provided meaningful support for an interactive writing experience.

1 Introduction

In Indian higher education institutions, first-year classrooms often function as a place where students get together with diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. For instance, in 2022–24, our institute admitted 1,024 undergraduate students reporting 34 languages as their mother tongues. Their linguistic backgrounds could be further diversified when considering their media of instruction in K-12 education and the language landscape in their neighborhood. One of the most competitive college entrance tests in India, Joint Entrance Examination (JEE), offered its main session in thirteen languages in 2024—English, Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Odia, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu (National Testing Agency India, 2024, 2025). Nationwide, Hindi is the most common medium of instruction for K-12 schools (TNN, 2023), while there has been recent increase in parents' preference for English-medium schools (Kulshrestha, 2024), which sometimes suffer from lack of qualified teachers (TNN, 2023). Since most higher educational institutions currently use English as a dominant working language for lessons and documentation, first-year writing (FYW) courses in India could play multiple roles: (i) teaching English-as-a-second-language (ESL), (ii) introducing academic literacy and providing space for practice, and (iii) expanding learners' cultural horizon through social interactions with individuals and groups.

FYW classrooms can also play a crucial role in incoming students' socialization. This study adopts Christie and Dinham (1991)'s view on socialization in education as “academic and social integration (p. 412)” and Bragg (1976)'s definition: “[a] process by which individuals acquire the values, attitudes, norms, knowledge, and skills needed to perform their roles acceptably in the group or groups in which they are, or seek to be, members (adapted from Merton, 1957, p. 41, and Bloom, 1963, p. 78) (p. 14)”. Students' successful integration to the institution and society has been regarded as the key to academic success and retention (Tinto, 2010). Students' socialization at Indian colleges and universities typically seems to be built upon English literacy development because English has been a dominant working language for academic discourse and, as pointed out by Kobayashi et al. (2017), socialization in general aims to meet the target “linguistic and rhetorical demands (p. 239)”.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe, 94 % of the student population across the world was affected by the closure of schools and colleges (UNESCO, 2020). According to a survey conducted by UNESCO (2022b) with students, teachers, and schools of eleven countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and America between December 2020 and July 2021, majority of the students felt “overwhelmed” by the global pandemic and worried about how the “disruption” would affect their learning (p. 132); many teachers reported that they observed decline in students' learning and engagement (p. 60). The teachers largely devised online teaching methods or a combination of online and offline teaching (p. 58), but two countries had a significant difficulty in offering online teaching (p. 63). In the case of India, schools were closed for 82 weeks (UNESCO, 2022a), and many colleges and universities, even after a 68-day-long highly restrictive lockdown was over in May 2020, continued the emergency remote teaching mode until early 2022. Practice of “social distancing” and remote learning caused dissatisfaction in the case of college freshmen internationally, as exemplified in Brown (2020) and Potts (2021).

Across the globe, governments, international organizations, educational institutions, and research put efforts to mitigate education catastrophe by devising facilitatory methods such as mobile learning (Ebardo and Suarez, 2023, for healthcare education in the Philippines), gamification (Frolova et al., 2021, for higher education in Russia), and TV broadcasting via satellite (Suwathanpornkul et al., 2023, for primary/secondary schools in Thailand). Especially for English language teaching and writing, educators devised and tested various approaches to maximize learners' engagement and hence learning outcomes. For instance, with respect to the mode of lessons, academic writing courses tried a combination of synchronous and asynchronous teaching modes in India and Iran (Desai et al., 2023; Khojasteh et al., 2024) and a blended learning with in-person and online sessions in Indonesia (Setiawan et al., 2023). For another example, with respect to the style of formative assessment, a learning-oriented online assessment was offered in China for feedback literacy practice (Ma et al., 2021) while multiple-choice questions were used in a writing classroom in South Africa, to stimulate critical thinking (Church, 2023). Thus, the pandemic necessitated application of information and communication technologies (ICT) and readjustment of pedagogies.

In addition, as Pretorius et al. (2023) pointed out, the era of social turmoil provided a chance to collectively reflect the role of education and academic identity in our respective areas. For example, in the ESL education, many trials were observed to maintain student autonomy and authenticity of lesson contents (Brooke, 2023; Setyowati et al., 2020). At the same time, ample research on students' social connectedness and their mental health during the pandemic has been conducted. For instance, Gonzalez-Ramirez et al. (2021)'s online survey with students of Manhattan College shows that remote learning was accompanied with reduced social connections, motivation, and healthy habits such as exercise and eating healthy during the pandemic; another online survey by Poole et al. (2023) with three Canadian universities indicates the importance of outreach programs and providing social network for students' feeling connected and reducing their stress level.

This study reflects on our journey from 2020 to 2023 in designing, executing, and further developing the first-year writing curriculum at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar (henceforth IITGN) for overall academic communication skill development with hands-on practice. This program was initially designed and offered online during the first COVID-19 wave and then, in mid-February 2022, was switched entirely to offline mode. In this study, I focus on the course developers' strategies to engage learners to authentic learning and socialization in an empowering manner and measure students' perception and perspective on their adapted learning environments.

After the general overview on the academic writing in Indian context and our curriculum development in Section 2, the reflections in this study are categorized in two: First, in Section 3, we discuss three “unchanged” principles for the course throughout—(i) engaging students in authentic, real-based learning practices, (ii) promoting socialization, and (iii) instructors' frequent feedback. Second, in Section 4, student survey results are presented as conducted for their experience in the offline and online writing classroom because active stakeholders of learning, students' input is necessary to optimize undergraduate writing classrooms for the future.

2 Course overview: HS191 and HS192 at IITGN

2.1 Contexts of academic writing courses in India's higher education

In academia, “we are what we write (Hyland, 2013, p. 53)” in that knowledge creation and transference heavily rely on written communication. Furthermore, as many researchers in teaching English-as-a-second-language (ESL) emphasized, writing is an essential practice for novices to be accustomed to the discipline-specific discourse and social conventions (Bhatia, 1999; Johns, 2008, 2011). In India, although English is a mother tongue of only 0.02 % of the population (Government of India, 2022), it is a prominent working language in Indian higher education (Meganathan, 2022; Graddol, 2010). Thus, it is not surprising that (i) academic writing is taken synonymously with English writing and (ii) mastering English is regarded as necessity for successful learning and performance.

To meet the strong requirement for English academic writing, various government and private sectors of Indian tertiary education have offered English writing courses and workshops with diverse levels and focuses for the last decade—from a general composition course to domain-specific literacy in curricular courses, workshops, certificate programs, and online open courses. A few examples are presented in (1).

(1) a. Compulsory first-year writing courses

• Language and Writing Skills-I and II (IIT Delhi, IIT Delhi, 2023).

• Introduction to Critical Thinking (Ashoka University, Singh, 2020).

• Introduction to Writing—I and II (IITGN, Kim and Lahiri, 2023).

b. Domain-specific writing electives or workshops

• Scientific writing in health research (ICMR School of Public Health, National Institute of Epidemiology, 2024).

• Workshop on Scientific Writing (IIT Delhi, IIT Delhi, 2023).

• Writing for Engineering (IITGN, Writing Studio, IIT Gandhinagar).

• Five Days' Academic Writing Workshop for the SC/ST Research Scholars and Early Academics by Dr. Aisha Hutchinson (Centre for Dalit and Sbaltern Studies, RGNIYD and School for Education, Communication and Society, King's College London UK, 2022).

c. Online open courses powered by Indian government educational portals: SWAYAM and NPTEL

• Academic Writing by Dr. Ajay Semalty (SWAYAM, SWAYAM, 2019).

• Effective Writing by Prof. Binod Mishra (NPTEL, NPTEL, 2022).

This trend of flourishing English writing curricula in tertiary education may have to be considered in conjunction with a relatively short history of satisfactory writing and critical thinking education at the K-12 level, as pointed out by Kim and Lahiri (2023) and Singh (2020). The English language used in the public textbooks was criticized as “outdated” (Mohan, 2014) until recently, and much of K-12 writing practice was viewed as focusing on mechanics in a prescriptive manner (Rai, 2015). Against this backdrop, one of the main learning goals of the first-year writing course, as shown in (1a), should be to facilitate spoken communication skills in the academic context and to help student naturally incorporate their thought process into writing.

In general, writing is learned in the formal setting through overt instruction, and its acquisition may not happen “natural” as learning speaking, even to the native speakers. It is evidenced by the fact that universities in English speaking countries offer freshmen composition courses, whose main target audience is English native speakers. Freshmen often struggle with academic writing or writing required in college as part of process to learn academic and institutional norms and etiquette. In the countries of Kachru (1998)'s “Expanding Circle” such as Russia and Thailand, where “English [is] used primarily as a foreign language (p. 93)”, two academic writing courses could co-exist in native language and English (Blinova, 2019). In that case, as illustrated about the Russian classroom by Korotkina (2014), sometimes we observe discrepancy between different academic writing norms and expectations in two languages. As for India, which has a long history of using English as a second language with its own developed Indian varieties (Kachru, 1965), I have perceived its learning goals and target repertoire of academic writing close to English-as-a-lingual-franca in international academic communication.

2.2 An overview on Introduction to Writing—I and II at IIT Gandhinagar

The undergraduate-level first-year writing curriculum, Introduction to Writing—I and II, of IIT Gandhinagar (IITGN) has been offered since 2020 as a compulsory part of the B.Tech. program, to “help students make a systematic approach to written materials in basic genres such as descriptive, expository, and persuasive writing (Kim and Lahiri, 2023, p. 211)”. Initial ideation and development were conducted by professors of the institute writing center and the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, including Jooyoung Kim, Arka Chattopadhyay, Leslee Lazar, and Ambika Aiyadurai. In the next year, its pedagogical structure was revamped with additional materials in collaboration with Dr. Stephen E. Kosslyn and his Active Learning Sciences Inc. team, adopting active learning strategies such as “sandwich method (Kosslyn, 2020)”. Since May 2022, the curriculum details and components have been on further structural refinement and content update to cater to our target B.Tech. student groups under optimal instructional contexts.

Since the initial ideation stage of the curriculum, the course developers have envisioned to assist learners to grow as: (i) smart writers who are able to logically express their ideas and opinions with literacy skills in diverse modalities, (ii) strategic communicators who are able to assess the target audience and alienate relevant contents and rhetoric, and (iii) ethical and competent researchers who are able to evaluate data from various sources and integrate them into their own work. These learning goals are on a par with the National Education Policy (MHRD Government of India, 2020) along the line of Sustainable Development Goal 4 United Nations (United Nations, 2015).

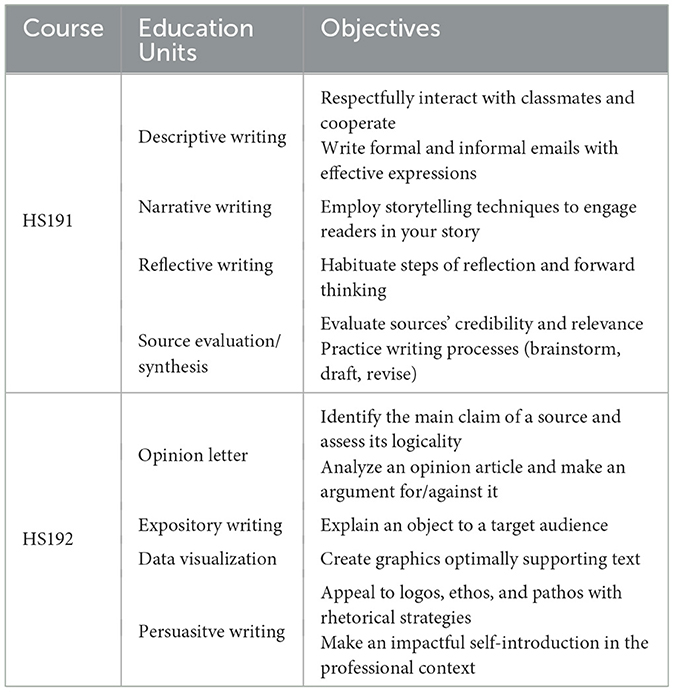

The primary focus of the first course (HS191) is to facilitate students' expressing their own thoughts enough while that of the second course (HS192) is to guide them to reason and analyze using techniques of writing. The two courses, henceforth HS191 and HS192, each has four thematized education units and related key objectives as illustrated in Table 1. Currently, each has two 80-min lessons with an asynchronous reading/writing practice per week as a 2-credit course. A classroom of 16–40 students is managed by a section-wise instructor, and a lesson consists of mini-lectures and related hands-on tasks activities to link students' learning directly to their practice.

Table 1. Learning objectives and education units of Introduction to Writing—I and II (HS191 and HS192).

Regarding the mode of instruction, a fully online learning system with synchronous lectures was maintained using Zoom, Google Workspace, and Microsoft Office Suite from August in 2020 to mid-February in 2022. After February 2022, all IIT Gandhinagar community members returned to campus for offline classes and services, with a sporadic exception to one HS192 section with a few virtual lessons in 2023. Accordingly, HS191/192 have evolved to adapt to the in-person lectures and activities, whereas Google Classroom and G-Suite continued to be used for learning management and course activities. Despite the drastic difference between offline and online environments, we found some underlying principles have continued with new faces, as illustrated in Section 3. Section 4 shows students' perceived strengths and weakness online/offline writing course curricular, Section 5 indicates discussions and implications, and Section ?? concludes the study.

3 Strategies in online/offline mode to meet “unchanged” principles

3.1 Authentic reading and writing experience being digital

Our HS191/192 curriculum aimed to facilitate students' authentic literacy experience. The term “authentic learning” can be defined following Shaffer and Resnick (1999)'s proposed four key aspects—“personal”, “real-world”, “disciplinary”, and “assessment”—as detailed in (2).

(2) Four aspects of authentic learning (Shaffer and Resnick, 1999, p. 195, 204)

a. “Personal”: “learning that is personally meaningful for the learners”

b. “Real-world”: “learning that relates to the real-world outside of the classroom”

c. “Disciplinary”: “learning that provides an opportunity to think in the modes of a particular discipline”

d. “Assessment”: “learning where the means of assessment reflect the learning process”.

These four aspects are interconnected for successful learning, but in this subsection, we will focus on two: real-world and disciplinary.

During the pandemic and even after it, we have tried to create an authentic learning environment following Herrington et al. (2014)'s view that authentic course contents and practices should “reflect the way the knowledge will be used in real life (p. 403)”. First of all, a wide selection of timely and relevant sources were used as reading materials in the lesson, from latest news articles to relatable social media posts, to engage students with current and noteworthy intra- and international topics. For example, up-to-date news articles were picked from a widely celebrated event (e.g., the ICC Men's Cricket World Cup in 2023) and a natural disaster (e.g., Tonga's volcanic eruption in 2022) to facilitate reading and discussions using students' existing background knowledge. In addition, these reading activities have become a good venue to introduce valuable textual and multimodal stories. For examples, narrative analysis lessons presented and analyzed the TIME's 2024 Kid of the Year tribute page of Heman Bekele, who invented a soap preventing skin cancer, and a TED talk video by Kulkarni (2018), a teenage Indian scientist invented a system preventing human stampede. Since our institute subscribes PressReader, a digital media subscription application for computers, smartphones, and tablets, students were encouraged to navigate domestic and international news at widely known newspapers and magazines such as Washington Post, The Hindu, The Indian Express, and India Today.

In the online classroom, selected sources were shared through a hyperlink and a QR code so that students could access them with their electronic devices, mostly mobile phones. The system of QR codes and students' use of electronic device has continued till now in the offline classroom for practicality and applicability. We believed the best reading exercise can be carried by “activities that mimic real world situations (Gilje and Erstad, 2017, p. 60)”, and reading practice on their most comfortable device can help learners build a habit of reading from quality outlets (however, since reading physical books and periodicals is also desirable, our curriculum included a library visit activity as well).

Growing information and communication technology (ICT) have called for the foundational change in reading and writing practice including ESL education. Introduction of computer-mediated communication has impacted the writing process (Alexander and Rhodes, 2018; Bloch and Wilkinson, 2014) and re-defining writing practice and literacy relevant to the 21st century (Elola and Oskoz, 2017; McCallum, 2021). Digital writing, referring to composing process and experience with digital platforms, has “transformed” the writing practice far more than using some advanced typewriter (Alexander and Rhodes, 2018): brainstorming, drafting, revision, data research, co-work, and communication among authors. In ESL classrooms, computer-mediated writing and digital multimodal composing have been tried over two decades and regarded as having potentials in the digital age (Elola and Oskoz, 2017; Li, 2018; Jiang and Hafner, 2024).

As for HS191/192, we have encourage students to draft, revise, and edit their individual end-of-the-unit writing projects in cloud-based digital format, by providing a template in Google Doc or Google Slides, which are compatible to Google Classroom, our current learning management system. Two of the noticeable strengths of the Google Doc/Slides/Sheet are (i) the “version history”, displaying the chronological change of the documents asynchronously, and (ii) the instant cursor, as shown in Figure 1, displaying ongoing activities of permitted users synchronously. The latter function has been powerful for in-class activities on a cloud-based document as a “collective note (Figure 2)”, which will be illustrated further in Section 3.2.

3.2 Learners' socialization: thinking together and understanding each other

While designing and developing HS191/192, the course developers incorporated components that promote socialization in the following three senses: First, novice scholars should acquire basic linguistic conventions and etiquette to take proper part in academic discourse in the sense of “academic and social integration (Christie and Dinham, 1991, p. 412)” and “language socialization in Ochs and Schieffelin (2012)” as discussed in the introduction. Second, we wanted to create an environment where students expand their horizon of cultural understanding by negotiating and cooperating in group, section, and cross-sectional activities. Last but not least, frequent learner–learner and learner–teacher interactions have been facilitated as a consequence of hands-on activities: We tried to incorporate dynamic and “authentic” phases of writing process in the sense of “assessment (2d)”, and at each phase of brainstorming, drafting, and revising/editing for individual writing projects, students had a brief discussion session to share current progress and exchange feedback.

For the definition and aspects of socialization, learners' institutional integration, connectedness, and sociocultural awareness, as illustrated in (3).

(3) Aspect of socialization considered in the first-year writing curriculum

a. Academic and social integration (Christie and Dinham, 1991): Students' acquisition of values, norms and expectations of the academic institution (Bragg, 1976).

b. Connectedness: Students' feeling connected to individuals, groups, communities, and the academic institution (Jorgenson et al., 2018).

c. Social and cultural awareness (World Economic Forum, 2016): Students' development of cultural self-awareness and respect for others (p. 8).

Integration (3a) and connectedness (3b) have been considered as crucial factors of students academic success (Poole et al., 2023), and (3c) aimed to stimulate their metacognition and strategy building, and to provide experience in which writing is not a lone work but a social act, benefitting from communication with others.

The three aspects materialized as designed components for socialization in three settings: (i) intra-section interactions, (ii) inter-section mixers, and (iii) conventional style acquisition. The relevant learning under (iii) materialized as practical themes such as writing formal and informal emails, mastering IEEE citation styles, and making a persuasive campaign. (i) and (ii) are discussed in more detail in Sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2.

3.2.1 Classroom “synchronous” socialization

During the pandemic, HS191/192 lessons were conducted via Zoom with its assistant features such as breakout room, poll, reaction, hand-raising, chat-to-everyone, and chat-to-an-individual. The breakout room function was regularly used, once or twice per lesson, because it created an interactive space for a smaller group (4 to 5) to practice what they learned in the lecture through a mini task. Educators in ESL and science also reported wide use of Zoom's breakout rooms, for language practice or collaborative group tasks in a science course, with facilitatory tactics as nominating a group leader in advance or assigning a collective assignment (Lee, 2021; Read et al., 2022). In our writing courses as well, a few tactics were played to maintain breakout rooms active: Group members were randomly assigned, and section instructors and TAs hopped in and out across the rooms to encourage students' activities. Naturally, physical classrooms after February 2022 took over small group activities in which instructors and TAs could have a better management, moving around the classroom. In both online and offline settings, small group tasks opened a peer-learning environment to maximize group members' overall understanding of lecture components. In addition, most students enjoyed interacting with different group members; to achieve it in the physical classroom, we used playing cards shuffled and randomly drawn by students each day so that new group were created based on the number of cards students drew.

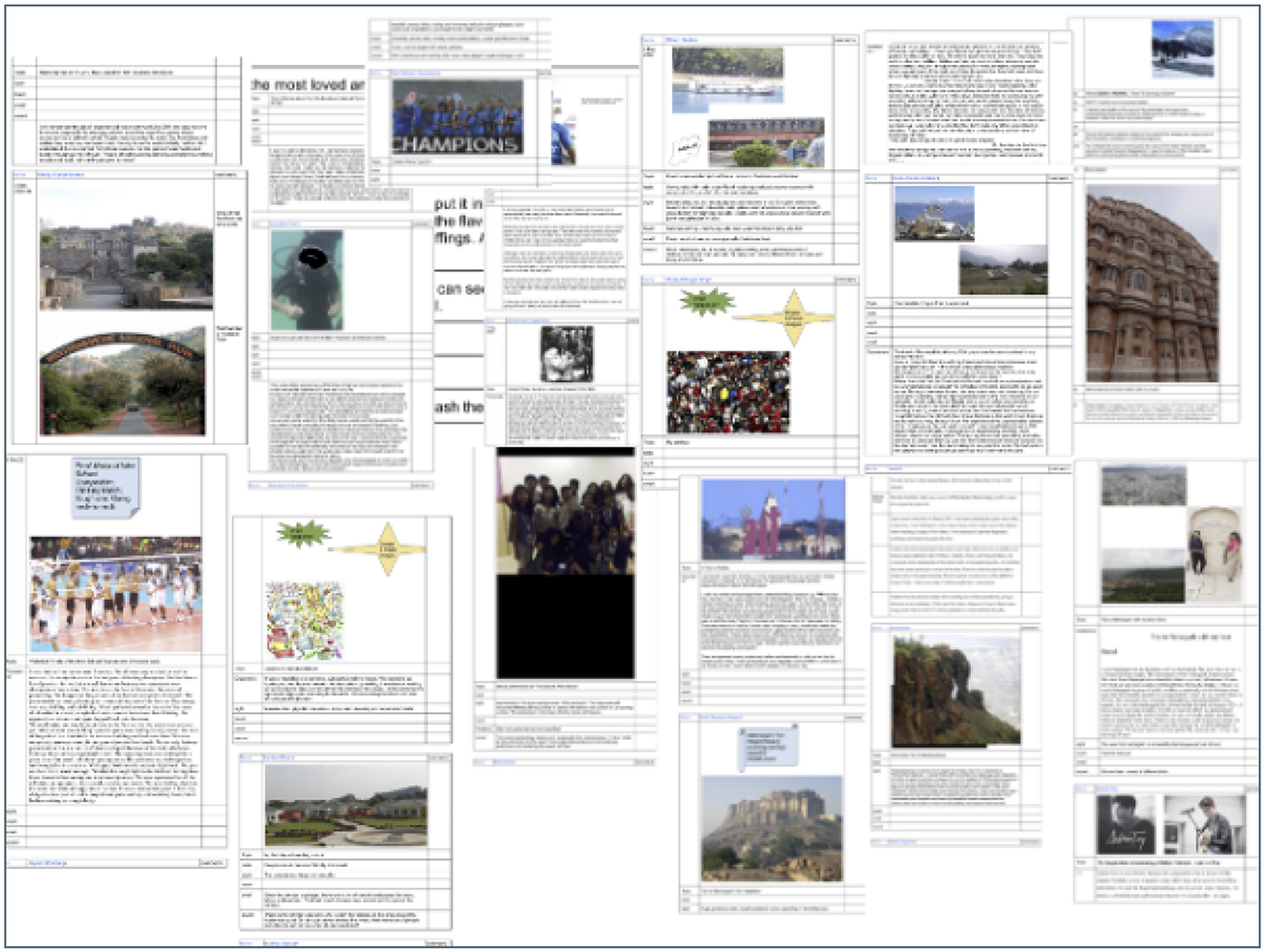

For students' writing practice in class, cloud-based document collaboration, “collective writing”, took place as described in Kim and Lahiri (2023, p. 214): “Students were invited to a shared Google document, which was stored in the instructor's Google account or their Google Classroom. During the virtual meetings, students were asked to find the shared document and begin drafting their essays. This activity was highly useful in the stage of topic selection as well as brainstorming for an initial draft.” Instructors and TAs could identify and trace students' progress by a blinking indicator as shown in Figure 1 and give either verbal feedback or written feedback in the comment box on the shared document as shown in Figure 2. This “collective notepad” also motivated students by showing their classmates' ongoing work and provide a chance to exchange feedback to one another.

3.2.2 Cross-classroom “asynchronous or cultural” socialization

Curricula of HS191/192 for online and offline modes had different goals and approaches about cross-sectional mixing. During the pandemic, first-year students mostly stayed at home, and there was a vital need to create a virtual “academic” space engaging them to maintain constant interactions in the higher education environment, in addition to the online synchronous classroom. Thus, building virtual learning communities (VLCs) was pivotal to make up the absence of physical socialization, as well as to foster students' autonomy and self-regulation (Desai et al., 2023).

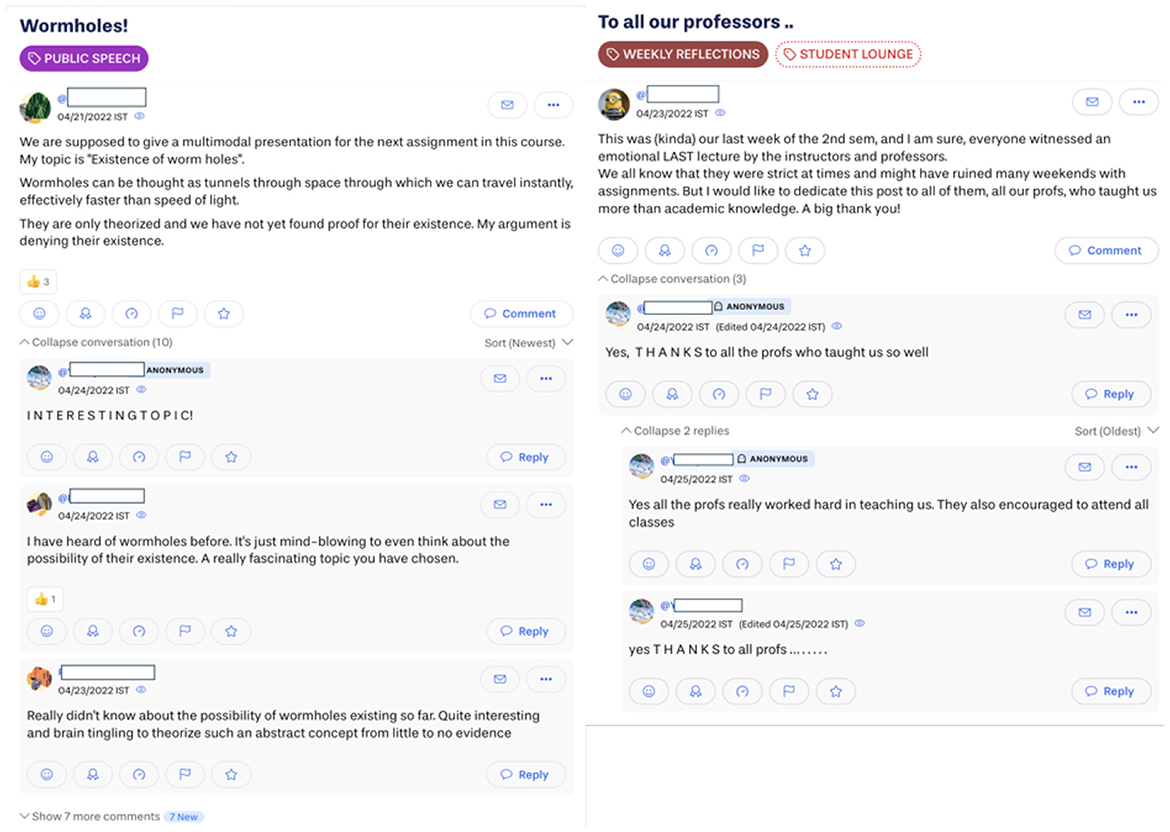

As the platform of our VLCs, Yellowdig (https://www.yellowdig.co) was considered, a gamified academic social networking system, to create a space for students to share reflections and exchange opinions relevant to their learning in an asynchronous mode, bridging between online live lectures and discussion sections. For example, each week, students were given a VLC task at the end of a live lesson, such as “Share the essay topic you are currently working on with your VLC”, promoting creating posts, comments, and interactive emojis on the VLC. Users' weekly performance was graded based on the number posts and comments, and counted towards their course participation score. Figure 3 shows two VLC post examples with enclosed comments and reactive emojis; the colorful tags such as “public speech” and “weekly reflection” indicate the topic of VLC tasks they were currently on.

The grouping of VLCs was distinct from the division of students' sections because an asynchronous VLC requires far more users to be operative compared to that of a section for synchronous lessons. For example, in 2021–22, approximately 250 students in 8 sections were regrouped in 3 VLCs. This regrouping of VLCs further motivated students to socialize with more classmates, and they enjoyed virtual interactions. Students' engagement was remarkable: A few requested to create more tags for purely social and interactive purposes because they enjoyed the virtual communication (so we created). Despite our “point system” that might feel imposing a burden to students, there was little sign that it stifled motivation (c.f. Brock et al., 2005), and more than half of the students (52.7%) received the full mark. The VLC activities naturally diminished in the physical classroom setting and discontinued in April 2022.

The cross-sectional activities after 2022–23 were conducted in the offline mode when students had many means and methods to socialize on campus via various extracurricular activities. Under this backdrop, we received freedom to focus on students' cultural literacy in the way that cross-sectional activities could raise students' cultural and linguistic awareness, such as an “International Mother Language Day celebration event”. Recently in February 2024, the first-year students were regrouped according to the language of their choice, and 16 cross-section groups made presentations on 16 languages spoken in India. The group size drastically varied from 1 to 104, but each group was given the same time to present. In addition, each group used innovative ways to make a multimodal presentation delivering their culture and language optimally.

3.3 Empowering students' voice in writing

Academic English writing can be challenging to native speakers due to “insufficient control of the language, muddy thinking, inexperience with writing in general and with scholarly genres in particular (Casanave, 2008, p. 266)”. In the case of English-as-a-second-language (ESL) speakers, who often need extra thought process, the level of challenges may be even higher (Silva et al., 2003; Forbes, 2018). Furthermore, ESL practice sometimes overlook learners' individual voice and their diverse cultural background (Nero, 2008; Miller, 2004). Keeping this in mind, we tried to invite our students to the practice of generating their own story as a competent writers.

First and foremost, maintaining close learner–instructor relationship and facilitating learner–learner interactions have been a key to successful lesson delivery to lower the affective filter and emotional barriers. Building a report in the classroom was a necessary condition for learners to open up themselves, share their opinions and personal life event stories, and lay them into the writing work. Despite many restrictions, virtual meetings provided a reasonably comfortable environment for learners to speak with instructors using 1-on-1 chatting. Instructors' online feedback on the collective notepad, discussed in Section 3.2.1, also reduced the distance between learner–instructor as well as learner–learner.

Moving to the physical classroom, offline activities significantly boosted students' interaction but with a few unexpected drawbacks. First, initially, the location of students' seats created unequal spatial distances in the classroom, as actually pointed out by some students, who remembered the virtual space where anyone had an equal distance to the teacher and classmates. As time went by, they adapted to the new environment with strategies such as rotating students' seats by playing-card-drawing as mentioned in Section 3.2.1. In addition, we spent longer practice time for small-group activities in the physical classroom, to maximize students' individual interaction with the instructor and TAs.

There were three pedagogical approaches maintained from online to offline learning environments to empower students, with respect to (i) the assigned theme, (ii) freedom of topic choice, and (iii) enough communication about instructors' expectations.

(i) Most of the writing assignments in HS191/192 were closely related to learners' personal reflection and expression. For examples, three projects in (4), under the units of Descriptive writing, Narrative writing, and Reflective writing require incorporating students' individual and personal experience.

(4) HS191 writing projects in the academic year 2022–23

a. Write a formal and an informal email to someone you would like to contact/ close to you.

b. Make a scholarship application on what you are or were passionate about.

c. Choose one of your most memorable events and reflect on it.

(5) HS192 writing projects in the academic year 2022–23

a. Write an opinion letter to the writer/editor of a opinion piece you strongly (dis)agree with.

b. Explain a fact/concept/process/procedure/principle that you learned or know well.

c. Persuade people by a written petition and a presentation.

d. Make an informative multimodal presentation on the topic of your choice.

(ii) These projects only assigned a broad theme, not a specific topic. For instance, in the opinion letter writing (5a), students were not given any particular opinion piece; instead, our lessons began practicing how to identify and evaluate opinion articles and then moved on to the stage of searching and reading opinion articles interesting to individual students. We believe this “pre-writing” stage necessary and valuable in the course because it reflects our authentic, daily reading routine and students can practice curriculum-based learner autonomy (Nguyen and Gu, 2013), in which they can select topics and references independently. As a consequence, lessons contained multiple hands-on individual writing sessions and group feedback sessions. We tried to provide students with joyful conversations that led to gradual development of writing.

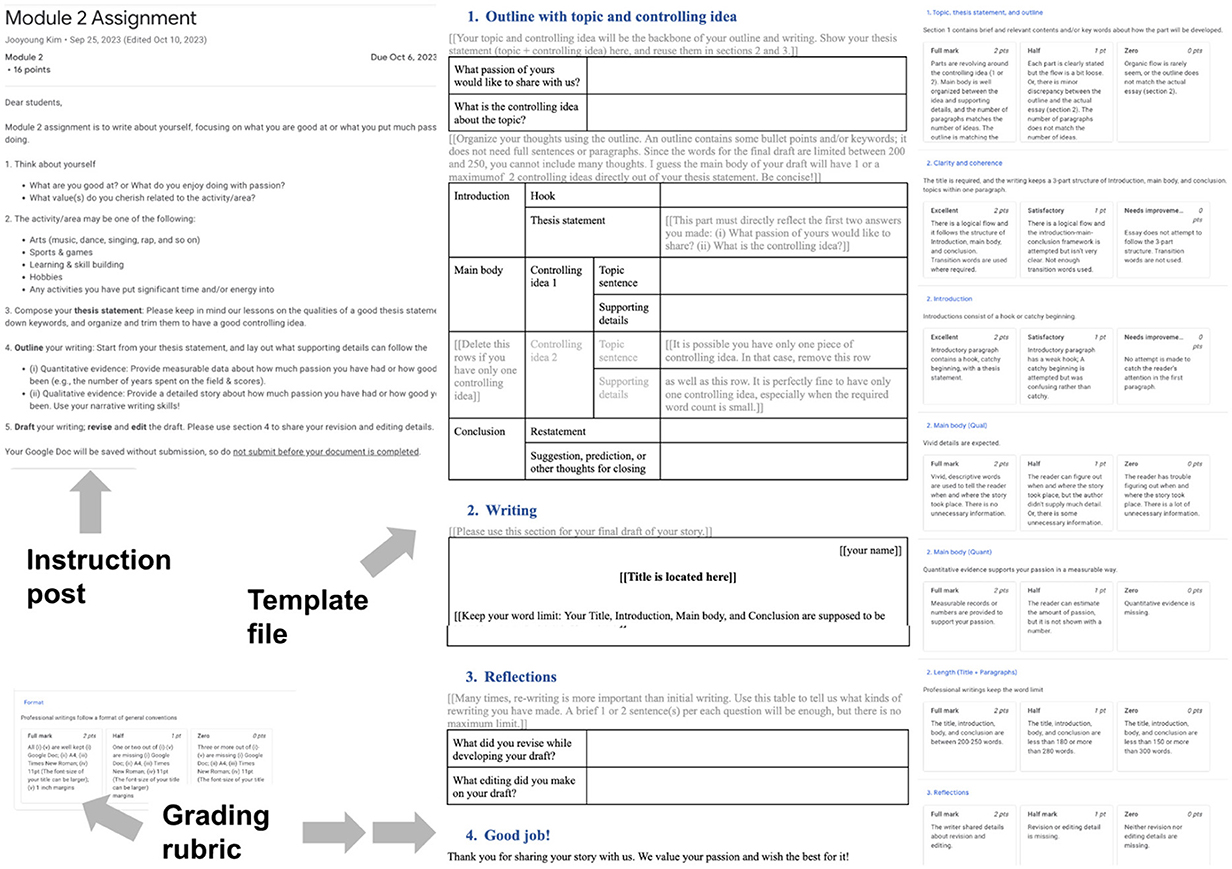

(iii) Multiple endeavors were incorporated to increase students' motivation and performance outcome. For instance, Google Workspace applications (e.g., Doc and Classroom) were interconnectedly used to communicate instructors' expectation of end-of-the-unit writing assignments. Each writing assignment had its instruction page posted on the Google Classroom, as illustrated in Figure 4. The instruction post enclosed a rubric specifying precise grading criteria and a “template” Google Doc file. Templates were used to effectively guide students' writing process: They could work directly on the individually given template file, familiarized with the desired document format for academic writing. More importantly, templates are used to guide a required writing process. In the assignment depicted in Figure 4, the example template is organized with three sections: topic selection/outlining, drafting, and reflection on revision/editing. In the section for topic selection/outlining, students were guided to first clarify the thesis statement and then to plan its expanded structure including a hook, topic sentences, and supporting details. In the next two sections, drafting and reflection on revision/editing, they provided written full paragraphs including the title and share what contents underwent revision and what structural errors were corrected. The first section was covered in a lesson activity, so that students clearly understood the connection between the three sections and, furthermore, began a writing project “together” through discussions with the instructor, TAs, and classmates.

Not only for the assignment but also for the lesson delivery, we incorporated methods to stimulate students' metacognition. Each lecture started with an overt learning objective on the slide to participate students as active stakeholders in learning.

4 A student reflection survey on online/offline writing courses

During the COVID-19 pandemic, most Indian higher education institutions operated virtually, and students' reception was generally positive about using a smartphone with cellular data (Muthuprasad et al., 2021). The courses at IITGN were also on an online learning system from August 2020 to mid-February 2022. Reflecting on the online and offline learning environments in 2020–2023, we could classify advantages and disadvantages of HS191/192 from our own reflections and students' report. For example, the breakout room function in the synchronous online classroom allowed swift switches between a small group activity and a whole class discussion. A number of students in our writing course expressed satisfaction with the efficiency of breakout rooms. Another strength of the virtual writing classroom we found was the 1-on-1 chatting function, which allowed a more open and honest private conversation with learners. At the same time, learners in the online classroom seemed more susceptible to digital distraction–even in physical classrooms, digital distraction, especially with cell phones, had been present and regarded as a major negative influence on students' learning (Flanigan and Babchuk, 2020). In the virtual classroom, students were inevitably exposed to more distractions, which called for effective but non-coercive strategies to attract students' attention and keep track of their writing activities. Under this backdrop, it was crucial to collect students' feedback on the online and offline first-year writing classroom to get insight into the most effective form of the classroom in the post-COVID era.

4.1 Goals and participants

An online survey was designed by the course coordinator to examine students' perception and perspective on their experience with the first-year writing (FYW) classroom in online and/or offline mode. A questionnaire was developed independently of regular course evaluation, based on the various aspects of online and offline lesson components course instructors observed, such as “breakout room activity (online)” and “small group activities (offline)”. This survey and the questionnaire were reviewed and approved by the IITGN ethics committee.

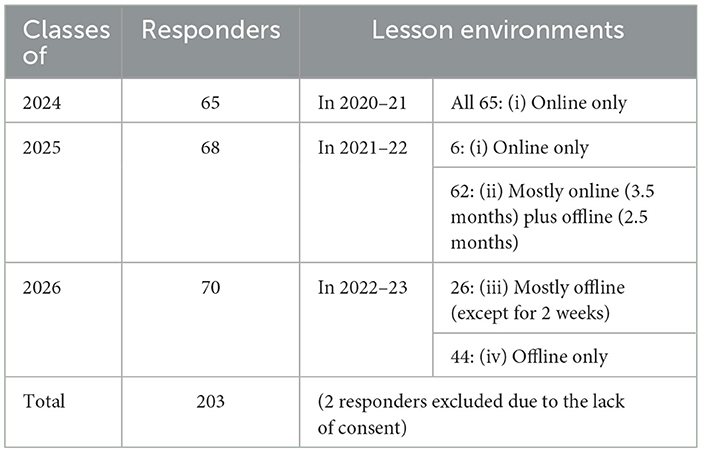

We targeted three student groups of IITGN: (A) the class of 2024, (B) the class of 2025, and (C) the class of 2026. Groups (A)–(C) took the FYW courses in the academic years 2020–21, 2021–22, and 2022–23, and their class populations are approximately 236, 239, and 285, respectively. The comparison of these groups can be meaningful because each group went through a distinctive trajectory of learning FYW: Whereas group (A) only experienced online writing lessons in 2020–21, majority of the group (B) experienced a hybrid—first took online lessons (3.5 months) and then shifted to offline lessons(2.5 months). As for group (C), all except for one section conducted full offline lessons; the exceptional section had online lessons for 2 weeks in the middle of the second semester.

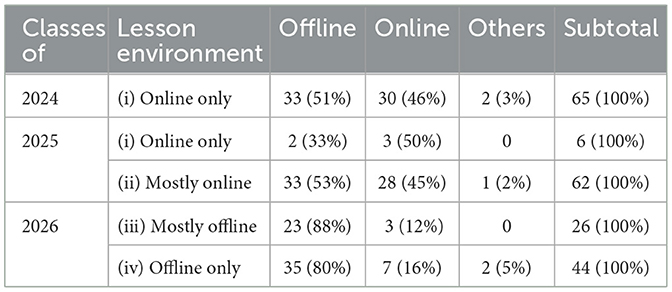

This survey was conducted in two phases: in October 2022 with groups (A–B) and in May 2023 with group (C) by the help of student representative who circulated the online survey form with students. Out of approximately 760, 205 students responded, and 203 responses were used for analyses (65, 68, and 70)as illustrated in Table 2: 88 responders experienced both online and offline FYW classrooms, while 71 and 44 experienced only online and only offline mode, respectively. Accordingly, we re-arranged groups based on their online and offline FYW experiences as in Table 2 and Figure 5: (i) experiencing online FYW classes only, (ii) mostly taking online FYW classes with a little offline FYW classroom experience, (iii) mostly taking offline FYW classes with a little online FYW classroom experience, and (iv) experiencing offline FYW classes only.

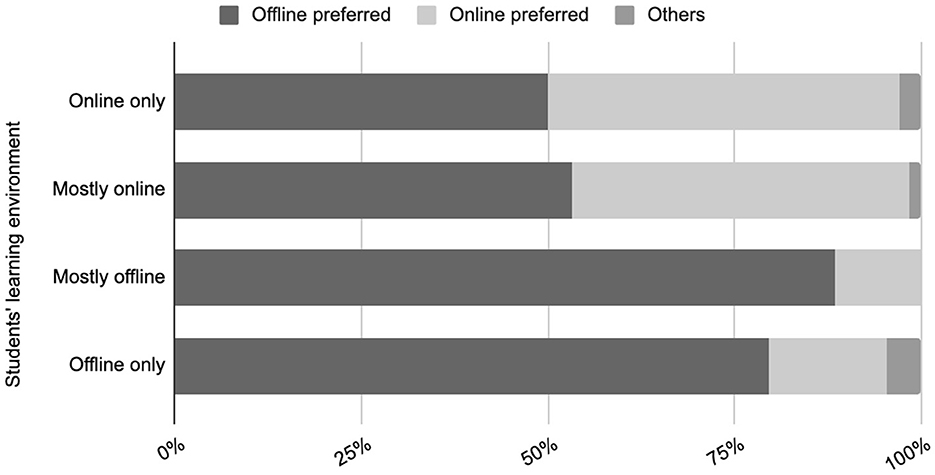

Figure 5. Students' choice percentage of preferred mode of instruction based on their learning environment.

4.2 Questionnaire

We used an online survey via Google Forms and stored in a linked Google Sheet, and students' private information such as the name and the email address was deleted and replaced by a unique code. The questionnaire contained 11–14 questions designed to understand students' perceived advantages and disadvantages of online/offline writing classrooms. The main themes were as shown in (6)–(9):

(6) Experience of online and offline FYW courses

a. Have you experienced an online writing course? (multiple choice)

b. Have you experienced an offline writing course? (multiple choice)

(7) Reflection of offline FYW courses:

a. Advantages (checkbox; including “other”).

b. Disadvantages (checkbox; including “other”).

c. Feasibility of FYW in the online setting (6 point Likert).

d. Free reflection (short answer; optional).

(8) Reflection of online FYW courses:

a. Advantages (checkbox; including “other”).

b. Disadvantages (checkbox; including “other”).

c. Feasibility of FYW in the offline setting (6 point Likert).

d. Free reflection (short answer; optional).

(9) Student preferred mode for FYW

a. Preference between online and offline FYW classrooms (multiple choice; including “other”).

b. Reason for the choice (short answer; optional).

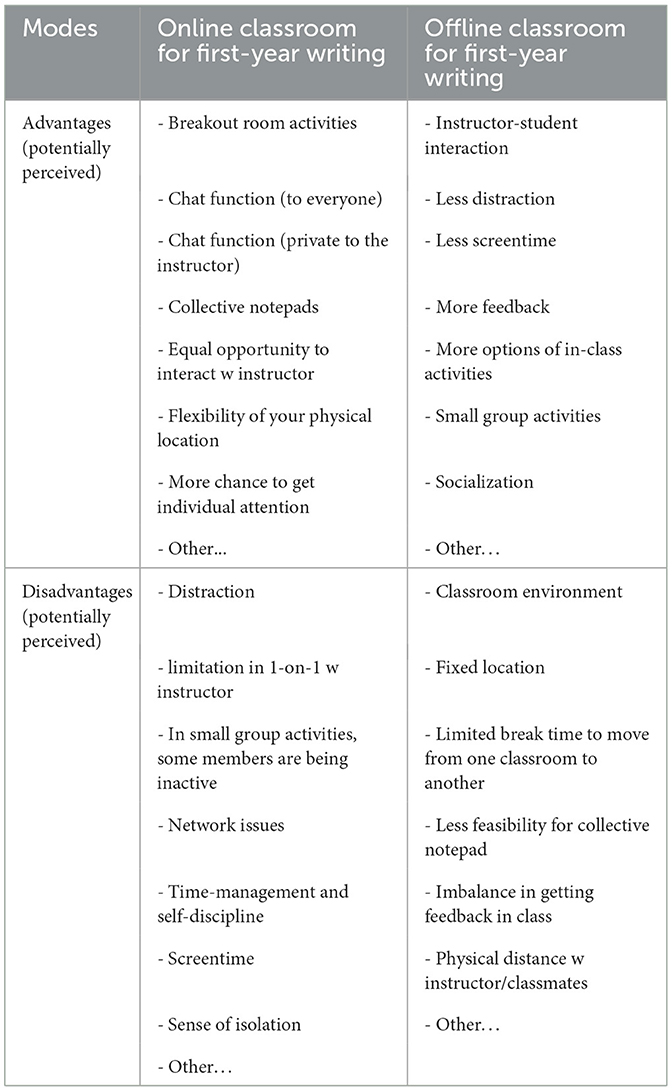

Four checkbox questions (i.e., 7a, 7b, 8a, 8b) asked about their perceived advantages and disadvantages of the online and offline writing classroom, and the given options, in Table 3, were collected based on the points directly communicated by students, in addition to instructors' reflections, including breakout room activities and collective notepads (online advantages), instructor–student interaction and less distraction (offline advantages), distraction and limitation in individual contact with the instructor (online disadvantages), and classroom environment and fixed location (offline disadvantages). The checkbox options in these questions also contained “others”, with which students could share other perceived advantages and disadvantages. In addition, one multiple choice question asked preference between online and offline writing lessons; three short answer questions were optionally given for students to share their thoughts freely about their own experience with online, offline, and overall learning experiences, some of which are shown in (11–14) below.

4.3 Responses and inter-group differences

With respect to the preferred mode of FYW lessons associated with question 4.2, students in groups (i) and (ii) (i.e., Exclusively online and Mostly online FYW conditions) showed an equally distributed preference: 35 versus 33 and 33 versus 28, respectively, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 5. This balanced preference may indicate that those who took the FYW course mostly or entirely online have little aversion against online lessons. In contrast, groups (iii) and (iv) showed dominant preference for the offline FYW classroom: 23 versus 3 and 35 vs. 9. This inter-group differences are regarded statistically significant through chi-square formula in (10) at a significant level (α = 0.05). Both groups (i) and (ii) show a significant difference with both groups (iii) and (iv), but groups (i)-(ii) and groups (iii)–(iv) did not show a difference among themselves, as shown in Table 5.

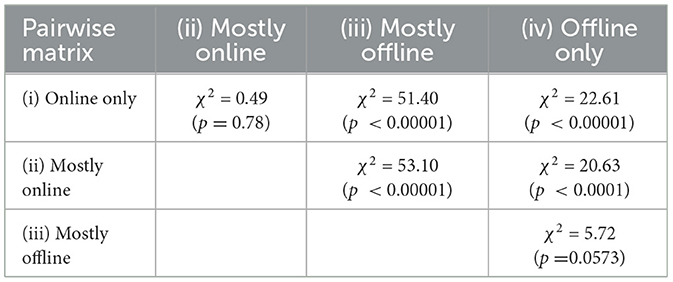

Table 5. Pairwise comparisons of four groups' tendency of preferences between offline and online lessons in Table 4: each pair's chi-square statistic (χ2) and p-value.

(10) , where

a. Oi = observed frequency for each category.

b. Ei = expected frequency for each category.

The group who only experienced online writing classrooms expressed the highest ratio of online preference (46.48%); however, even in this group, the preference for offline learning was marginally higher (49.30%). The group that experienced mostly offline writing learning with a short online learning experience showed the lowest preference for online mode (11.54%) as opposed to offline (88.46%). From a total of 88 students who experienced both offline and online writing classrooms, 57 students (64.8%) preferred the offline classroom, and 31 students (35.2%) chose the online classroom.

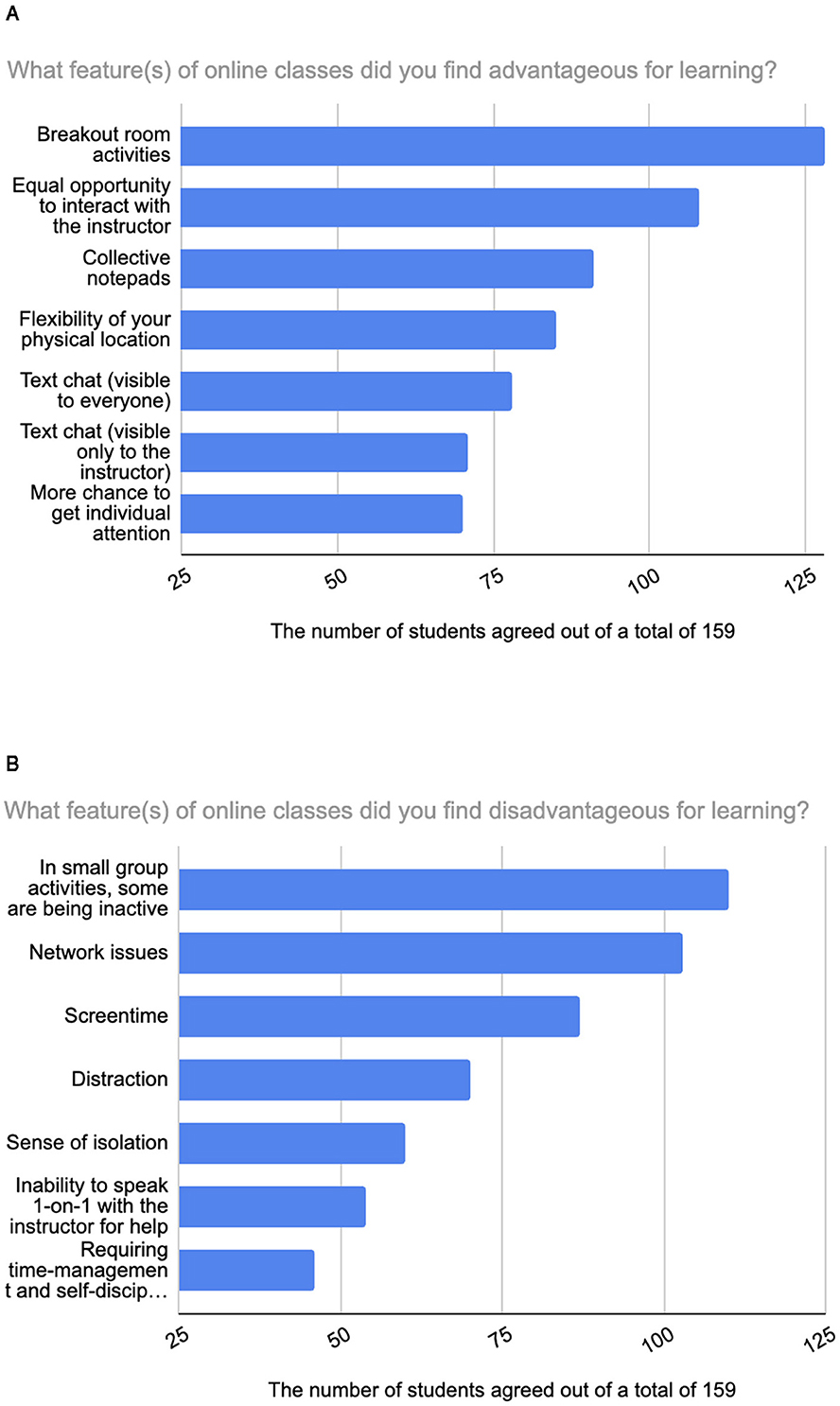

Regarding the advantages of the online classroom, 128 out of 159 students picked breakout room activities, and the next widely perceived advantage was the equal opportunity to interact with the instructor (108 out of 159) and collective notepads (91 out of 159) (Figure 6A). The breakout room function was the most mentioned in students' optional comment as in (11); at the same time, a few students were aware of the downside of breakout rooms when it was not properly monitored, as mentioned in item (12a) as well as Figure 6B. In the figure, students found inactive participants as the most negative factor, more inhibitory than the network issue. Students' free comments on the negative side of online writing classrooms were mostly in comparison with physical classrooms: They reported fatigue and lack of human feel in the online classroom during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6. Student responders' perceived (A) advantages and (B) disadvantages of the online classroom.

(11) Positive feedback about online learning in writing

a. “Interaction was good and everyone is able to talk to the instructor 1 on 1.”

b. “Breakout room activity and collective notepad are the best advantages.”

c. “Breakout room were, great way of interaction because we can talk freely.”

d. “Online learning can be very effective in case of Writing courses due to the breakout rooms feature, collective notepads, chats features. It would not be much screentime and would also not give much sense of isolation since the sessions in Writing courses are only of an hour.”

(12) Negative and neutral feedback about online learning in writing

a. “The breakout rooms (if not monitored) were the worst part of online learning. Participants tend to be passive.”

b. “In online mode, we really miss out on creating a long lasting connection between prof and student. There was a huge benefit was to learn in position we liked until video is to be made on.”

c. “Physical learning is always more effective than online learning, this is what i have experienced in my last 5 semesters at IITGN.”

d. “As we have already been a part of this online classes thing due to COVID, by default everyone is tired of this online classes and we are already used to how to not concentrate in these online classes.”

e. “I want to specify that the timing of the class and particularly the instructor are very important factors in online classes. I found HS191 very informative and interesting though it was online. Although HS192 was offline for me the engagement could not be as good as it was expected. I certainly believe that this was due to the instructor.”

f. “I believe that the success of online mode depends mainly on factor like discipline and drive of the individual.”

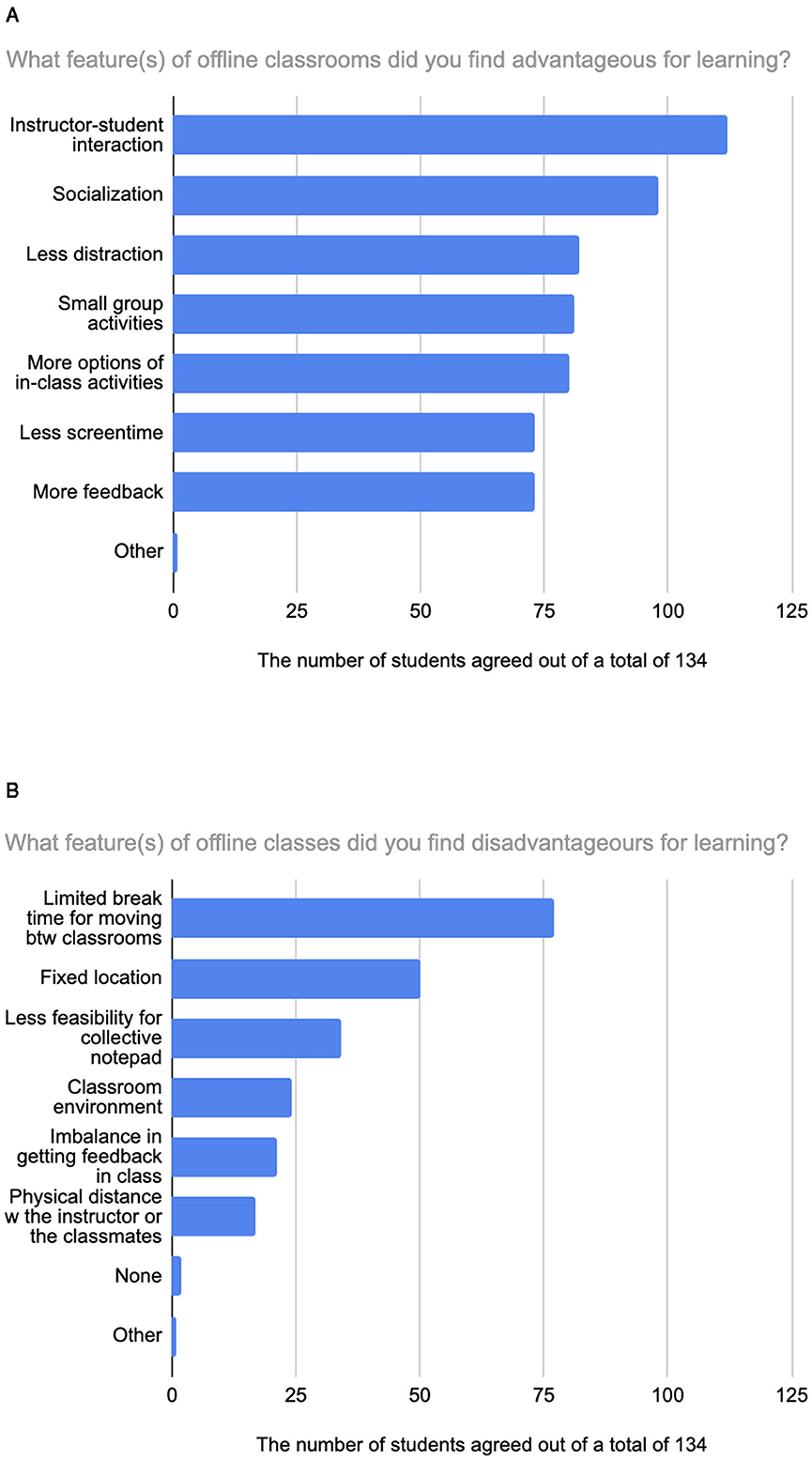

In regard to the offline writing lessons, a closer learner–teacher relationship was selected as the most positive factor, chosen by 112 out of 134 students who experienced an offline learning system, followed by socialization (98 students), less distraction (82 students), small group activities (81 students), and more options of in-class activities (80 students) as shown in Figure 7A. As for the drawbacks of the offline mode, respondents considered the constraints of lesson time and space as the biggest disadvantages, which are followed by less applicability of digital tools, as in Figure 7B.

Figure 7. Student responders' perceived (A) advantages and (B) disadvantages of the offline classroom.

(13) Positive feedback about offline learning in writing

a. “The offline learning is way more fun as it induces new ideas from others more easily, more opportunity to interact and we also had our class on terrace so it was so fun learning in open air (smiling-emoji).”

b. “Offline classes allowed greater interaction with the instructor. It also allowed the instructor to give feedback not only on the verbal aspect but also on the non-verbal aspects of communication.”

c. “The physical presence of the instructor helps in getting the message across clearly.”

d. “According to me writing class must be in offline mode so that the instructor can interact with every student on a personal level because writing requires a lot of motivation.”

(14) Negative and neutral feedback about offline learning in writing

a. “Offline learning is helpful many times when some practical example is to be shown. But writing courses do not have such things so they can be conducted in online mode and even more efficiently.”

b. “Offline was something I would not prefer for writing class as the environment in class was not that great as compared to online.”

c. “There were not enough group activities/discussions as compared to online mode.”

d. “Offline learning has its pros and cons, for example it would become very difficult to learn if there are no ACs in summer, but personal feedback is helpful.”

To summarize, students largely preferred offline writing classrooms regardless of their experienced learning mode. Among those who experienced both offline and online writing classrooms, 64.8% preferred the offline classroom, and 35.2% chose the online classroom. In addition, the selected disadvantages of the offline mode were significantly fewer than those of the online mode (i.e., 503 and 223). Meanwhile, many students acknowledged the positive part of online classrooms, such as breakout room activities, in which 3–4 students were put into a smaller virtual space for a group task, collective notetaking powered by a shared cloud document, and favorable environments for introverted students to participate in the classroom.

5 Discussion and limitations

The present study showed endeavors of adapting first-year writing lessons to the changing environments. Even when the COVID-19 pandemic was over, a considerable number of teaching principles and strategies for online classes have been used continuously due to their ongoing benefit for the physical classroom setting. The active application of digital tools such as QR codes and collective notepads was regarded beneficial in this time of reconceptualizing and clarifying “academic language” (Snow and Uccelli, 2009) for English-as-a-second-language (ESL) learners in academia, bringing unanticipated benefits of using technology (c.f. Miller, 2020).

In traditional ESL teaching, students' primary learning focused on prose and critics on intellectually challenging topics; this general practice required redefinition and reevaluation, considering digital literacies (Elola and Oskoz, 2017; McCallum, 2021) and writing across the curriculum (WAC) (McLeod and Soven, 1992; Flynn et al., 1997; Hyland, 2008; Kinloch, 2011). Writing courses need to incorporate general literacy skills into suitable communication contexts close to authentic environments, catering to improving learners' language level, domain-specific knowledge, and genre-specific styles critical to their academic socialization.

Students' mixing in HS191/192 during the pandemic took place in online breakout rooms and cloud-based collective notepads synchronously within a section; a virtual learning community was also tried asynchronously for cross-sectional communication. After the pandemic, offline extracurricular activities and in-course cultural events were conducted for mixing and cultural literacy building. Online and offline modes showed their own strengths: Despite many restrictions, virtual meetings provided a comfortable environment for learners to speak with the instructor using 1-on-1 chatting modes. Instructor's online feedback on the collective notepad also reduced the distance between pupil–instructor as well as pupil–pupil. Moving to the offline classroom, learners felt their experience more authentic and interactive, and longer practice times were assigned to guarantee students' individual interaction with the instructor team.

In both modes, class assignments aimed to involve students' individual and personal experience, and they were invited to direct their topic and references independently instead of being assigned by the instructor in many tasks including the end-of-the-unit assignment. In addition, activities took place using students' electronic devices as an essential component for in-class reading. However, in-person instructions and activities had considerable benefits with respect to the varieties of activity types and the intensity in ushering learners' steps for critical thinking, writing, and rewriting.

In addition, responders' two most perceived advantages about each mode—online breakout room activities, equal opportunities for instructor interaction online, offline instructor–student interaction, and offline socialization in Figures 6A, 7A—may indicate students' appreciation of socialization in FYW classrooms, resonating with the HS191/HS192 course developers' view on the FYW classrooms' role for social and cultural integration and connectedness.

This study is limited to one institute within a 3-year window, and, because the research and reflection were conducted by its own curriculum developer as well as the instructor, it may contain biases and idiosyncrasies that cannot be generalized. Furthermore, IITGN offers only Engineering programs for undergraduates; thus, the pedagogical approach and contents might be difficult to generalize.

6 Conclusion

Designing and offering a first-year writing (FYW) curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic required accommodation of information and communication technology on the one hand and maximizing students' social integration and connectedness though strategies for active learning and total engagement. The online mode opened up an opportunity to use electronic devices and cloud systems, while the offline mode provided more intensive care and socialization. Before, throughout, and after the pandemic, three main aspects of FYW lessons have been maintained stable—enhancing authentic learning, facilitation learners' socialization in various aspects, and empowering students' voices. They have been kept unchanged with various strategies optimal to the given situation.

The student survey on perception and perspective on offline and online FYW courses showed that the online mode may be feasible when supported by technologies facilitating person-to-person interactions and group activities, which might be still highly restricted compared to the offline mode. Our ongoing direction is to connect these reflections further toward more effective ESL academic writing and thinking skill building lessons in coupled with the WAC in the digital era.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because our survey data included private information of responders. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Jooyoung Kim, am9veW91bmcua2ltQGlpdGduLmFjLmlu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human/animal participants were reviewed and approved by the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar Institutional Ethics Committee (ID: IEC/2022-2023/F/JK/005). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The partial financial support was received from the Department of Cognitive Sciences, IITGN, for publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I thank Professors Sudhir K. Jain and Rajat Moona, former and current Directors of IIT Gandhinagar, for their vision and support in promoting academic communication and also thank the HS191/192 instructors, co-developers, and TAs for their dedication and excellence. The collaborations with Active Learning Sciences, INC. and Yellowdig were not possible without the financial and spiritual support by Maker Bhavan Foundation (https://makerbhavanfoundation.org/) and President, Ruyintan “Ron” E. Mehta, mediated by Professor Pratik Mutha.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alexander, J., and Rhodes, J (2018). “Introduction: What do we talk about when we talk about digital writing and rhetoric?,” in The Routledge Handbook of Digital Writing and Rhetoric, eds. J. Alexander, and J. Rhodes (London: Routledge), 1–6.

Bhatia, V. (1999). “Integrating products, processes, purposes and participants in professional writing,” in Writing: Texts, Processes and Practices, eds. C. Candlin, and K. Hyland (Longman), 21–39.

Blinova, O. (2019). “Teaching academic writing at university level in Russia through massive open online courses: National traditions and global challenges,” in Proceedings of INTED 2019 Conference 11th-13th March 2019, Valencia, Spain, 6085–6090.

Bloch J. and Wilkinson, M. (2014). Teaching Digital Literacies. English Language Teacher Development Series. Virginia: TESOL International Association.

Bloom, S. (1963). The process of becoming a physician. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 346, 77–87. doi: 10.1177/000271626334600108

Bragg, A. (1976). “The socialization process in higher education,” in ERIC/Higher Education Research Report No. 7. Grandview, MO: American Association for Higher Education.

Brock, D., Ballweg, R., Wick, K., and Byorth, K. (2005). Online collaborative exercises: The implications of anonymous participation. Persp. Physi. Assist. Educ. 16, 13–17. doi: 10.1097/01367895-200516010-00004

Brooke, S. (2023). Moving into the post-pandemic realm: Authentic digital tasks for integrated language skills. Int. J. Adv. Res. Educ. Soc. 5, 250–255. doi: 10.55057/ijares.2023.5.4.23

Brown, S. (2020). Meet Covid-19's freshman class. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/meet-covid-19s-freshman-class (Accessed April 10, 2025).

Casanave, C. (2008). “The stigmatizing effect of Goffman's stigma label: a response to John Flowerdew”. J. English Acad. Purposes 7, 264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2008.10.013

Centre for Dalit and Sbaltern Studies RGNIYD and School for Education, Communication and Society, King's College London UK. (2022). Report of the Writing Workshop: Publishing for Social Change: Supporting Emerging Writing on Social Work and Youth Work in India, 5th to 7th January, 2022. Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development (RGNIYD).

Christie N. and Dinham, S. (1991). Institutional and external influences on social integration in the freshman year. J Higher Educ. 62, 412–436. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1991.11774140

Church, A. (2023). Optimising academic writing assessment during Covid-19: The development multiple choice tests to develop writing without writing. Persp. Educ. 41, 23–38. doi: 10.38140/pie.v41i3.6804

Desai, M., Lazar, L., and Kim, J. (2023). “Virtual learning community for an online undergraduate writing course to promote learners' interactions and self-learning,” in Proceedings of International Conference on Technology 4 Education (T4E) 2023, 233-236.

Ebardo R. and Suarez, M. (2023). Do cognitive, affective and social needs influence mobile learning adoption in emergency remote teaching? Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 18:14. doi: 10.58459/rptel.2023.18014

Elola I. and Oskoz, A. (2017). Writing with 21st century social tools in the L2 classroom: New literacies, genres, and writing practices. J. Second Lang. Writ. 36, 52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2017.04.002

Flanigan, A., and Babchuk, W. (2020). Digital distraction in the classroom: exploring instructor perceptions and reactions. Teaching in Higher Education 27, 352–370. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1724937

Flynn, E., Remlinger, K., and Bulleit, W. (1997). Interaction across the curriculum. JAC. 17, 343–364.

Forbes, K. (2018). ““German I have to think about it more than i do in English”: The foreign language classroom as a key context for developing transferable metacognitive writing strategies,” in Metacognition in Language Learning and Teaching, eds. Haukås, C. Bjørke, and M. Dypedahl (London: Routledge), 139–156.

Frolova, E., Rogach, O., Tyurikov, A., and Razov, P. (2021). Online student education in a pandemic: new challenges and risks. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 10, 43–52. doi: 10.13187/ejced.2021.1.43

Gilje Ø. and Erstad, O. (2017). Authenticity, agency and enterprise education studying learning in and out of school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 84, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2016.05.012

Gonzalez-Ramirez, J., Mulqueen, K., Zealand, R., Silverstein, S., Reina, C., BuShell, S., et al. (2021). Emergency online learning: college students' perceptions during the COVID-19 crisis. College Stud. J. 55, 29–46. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3831526

Government of India (2022). “Language atlas of India 2011,” in Census of India. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, India.

Herrington, J., Reeves, T., and Oliver, R. (2014). “Authentic learning environments,” in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, eds. J. Spector, M. Merrill, J. Elen, and M. Bishop (Cham: Springer), 401–412.

Hyland, K. (2008). Genre and academic writing in the disciplines. Lang. Teach. 41, 543–562. doi: 10.1017/S0261444808005235

Hyland, K. (2013). Writing in the university: education, knowledge and reputation. Lang. Teach. 46, 53–70. doi: 10.1017/S0261444811000036

IIT Delhi (2023). Courses of study 2023-24. Available online at: https://home.iitd.ac.in/curriculum.php (Accessed April 10, 2025).

Jiang L. and Hafner, C. (2024). Digital multimodal composing in L2 classrooms: a research agenda. Lang. Teach. 2024, 1–19. doi: 10.1017/S0261444824000107

Johns, A. (2008). Genre awareness for the novice academic student: an ongoing quest. Lang. Teach. 41, 237–252. doi: 10.1017/S0261444807004892

Johns, A. (2011). The future of genre in L2 writing: fundamental, but contested, instructional decisions. J. Second Lang. Writ. 20, 56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2010.12.003

Jorgenson, D., Farrell, L., Fudge, J., and Pritchard, A. (2018). College connectedness: The student perspective. J. Scholars. Teach. Learn. 18, 75–95. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v18i1.22371

Kachru, B. (1965). The indianness in Indian English. Word 21, 391–410. doi: 10.1080/00437956.1965.11435436

Khojasteh, L., Zarifsanaiey, N., and Karimian, Z. (2024). Bichronous scientific writing course for medical faculty during Covid-19: a SWOT analysis experience. Front. Educ. 9:1327087. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1327087

Kim J. and Lahiri, S. (2023). Maximum engagement, minimum distraction, and knowledge transference. Int. J. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 35, 208–218.

Kinloch, V. (2011). Innovative writing instruction: when it happens “across”: Writing as transformative and expansive. Adv. Teach. English 100, 95–99. doi: 10.58680/ej201114922

Kobayashi, M., Zappa-Hollman, S., and Duff, P. (2017). “Academic discourse socialization,” in Language Socialization, eds. P. Duff, and S. May (Cham: Springer), 239–255.

Korotkina, I. (2014). Academic Writing in Russia: Evolution or Revolution. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm?abstractid=2435130 (Accessed April 10, 2025).

Kosslyn, S. (2020). Active Learning Online: Five Principles that Make Online Courses Come Alive. Chicago, IL: Alinea Learning.

Kulkarni, N. (2018). A Life-Saving Invention that Prevents Human Stampedes. Available online at: https://www.ted.com/talks/nilay_kulkarni_a_life_saving_invention_that_prevents_human_stampedes

Kulshrestha, P. (2024). As English-Medium Schools Gain Popularity, their Hindi countErparts see Sharp Drop in Rajasthan. Noida: The Indian Express. Available online at: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/rajasthan-private-hindi-medium-schools-drop-in-admissions-9567553/ (Accessed September 14, 2024).

Lee, A. (2021). Breaking through digital barriers: Exploring EFL students' views of Zoom breakout room experiences. Korean J. English Lang. Linguist. 21, 510–524. doi: 10.15738/kjell.21.202106.510

Li, M. (2018). Computer-mediated collaborative writing in L2 contexts: an analysis of empirical research. Comp. Assist. Lang. Learn. 31, 882–904. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1465981

Ma, M., Wang, C., and Teng, M. (2021). Using learning-oriented online assessment to foster students' feedback literacy in l2 writing during covid-19 pandemic: a case of misalignment between micro- and macro- contexts. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 30, 597–609. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00600-x

McCallum, L. (2021). The development of foundational and new literacies with digital tools across the European higher education area. Aula Abierta 50, 615–624. doi: 10.17811/rifie.50.2.2021.615-624

McLeod S. and Soven, M. (1992). “Writing across the curriculum in a time of change,” in Writing Across the Curriculum: A Guide to Developing Programs (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications), 1–27.

Meganathan, R. (2022). “Language conundrum: English language and exclusivity in India's higher education,” in Critical Sites of Inclusion in India's Higher Education, ed. P. Sengupta (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan), 81–96.

Merton, R. (1957). “Some preliminaries to a sociology of medical education,” in The Student-Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education, eds. R. Merton, G. Reader, and P. Kendall (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

MHRD Government of India (2020). National Education Policy of India 2020 (NEP 2020). New Delhi: The Ministry of Human Resources Development, Government of India.

Miller, J. (2004). “Identity and language use: The politics of speaking ESL in schools,” in Negotiation of Identities in Multilingual Contexts, eds. A. Pavlenko, and A. Blackledge (Multilingual Matters), 290–315.

Miller, R. (2020). Long Live The Zoom Class Chat: The Chat Solves Education Problems we Didn't Even Know We Had. SLATE. Available online at: https://slate.com/technology/2020/10/long-live-zoom-class-chat-remote-learning.html (Accessed October 8, 2020).

Mohan, P. (2014). The road to English: slow migration of the economically weak child to elite India. Economic & Political Weekly 49, 19–24.

Muthuprasad, T., Aiswarya, S., Aditya, K., and Girish, KJ. (2021). Students' perception and preference for online education in india during covid-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 3:100101. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100101

National Institute of Epidemiology (2024). “NIeCer 103: Scientific writing in health research for health and allied sciences,” in ICMR School of Public Health. Available online at: https://nie.gov.in/icmr_sph/Scientific-writing.html (Accessed September 14, 2024).

National Testing Agency India (2024). FAQs for Joint Entrance Examination (Main)-2024. New Delhi: National Testing Agency, India.

National Testing Agency India (2025). FAQs for Joint Entrance Examination (Main)-2025. New Delhi: National Testing Agency, India.

Nero, S. (2008). Language, identities, and ESL pedagogy. Lang. Educ. 19, 194–211. doi: 10.1080/09500780508668674

Nguyen L. and Gu, Y. (2013). Strategy-based instruction: a learner-focused approach to developing learner autonomy. Lang. Teach. Res. 17, 9–30. doi: 10.1177/1362168812457528

NPTEL (2022). Effective Writing by Prof. Binod Mishra. Ministry of Education, Government of India. Available online at: https://onlinecourses.nptel.ac.in/noc22_hs05/preview

Ochs E. and Schieffelin, B. (2012). “The theory of language socialization,” in The Handbook of Language Socialization, eds. A. Duranti, E. Ochs, and B. Schieffelin (Oxford: Blackwell), 1–22.

Poole, H., Khan, A., Smith, A., and Stypulkowski, A. (2023). The importance of others: The link between stress and social connectedness in university students. Canad. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 14:13. doi: 10.5206/cjsotlrcacea.2023.1.10885

Potts, C. (2021). Seen and unseen: first-year college students' sense of belonging during the COVID-19 pandemic. College Stud. Affairs J. 39, 214–224. doi: 10.1353/csj.2021.0018

Pretorius, L., de Caux, B., and Macaulay, L. (2023). “Preface: Research and teaching in a pandemic world,” in Research and Teaching in a Pandemic World, eds. de Caux, B., Pretorius, L., and Macaulay (Cham: Springer), 3–14.

Read, D., Barnes, S., Hughes, O., Ivanova, I., Sessions, A., and Wilson, P. (2022). Supporting student collaboration in online breakout rooms through interactive group activities. New Direct. Teach. Phys. Sci. 17:3946. doi: 10.29311/ndtps.v0i17.3946

Setiawan, M., Prawati, M., and Karjo, C. (2023). “Blend academic writing: The use of technology to teach amid covid-19 pandemic,” in 2023 11th International Conference on Information and Education Technology (ICIET) (Fujisawa: ICIET), 237–240.

Setyowati, L., Sukmawan, S., and El-Sulukiyaah, A. (2020). Learning from the pandemic: Using authentic materials for writing cause-effect essay in indonesian context. Int. J. Lang. Educ. Teach. 8, 158–167. doi: 10.29228/ijlet.45405

Shaffer D. and Resnick, M. (1999). “Thick” authenticity: new media and authentic learning. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 10, 195–216.

Silva, T., Reichelt, M., Chikuma, Y., Duval-Couetil, N., Mo, R., Vélez-Rendón, G., et al. (2003). “Second language writing up close and personal: Some success stories,” in Exploring the Dynamics of Second Language Writing, ed. B. Kroll (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 93–114.

Singh, K. (2020). “Building a center for writing and communication: inclusion, diversity and writing in the Indian context,” in Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education: Lessons from Across Asia, eds. C. Sanger, and N. Gleason (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 209–230.

Snow C. and Uccelli, P. (2009). “The challenge of academic language,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy, eds. D. Olson, and N. Torrance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 112–133.

Suwathanpornkul, I., Sarnkhaowkhom, C., Tulmethakaan, M., Sakuntanak, P., and Charoensuk, O.-u. (2023). Learning loss and psychosocial issues among Thai students amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: the perspectives of teachers in the online classroom. BMC Psychology, 11:232. doi: 10.1186/s40359-023-01269-1

SWAYAM (2019). Academic Writing by Dr. Ajay Semalty. Ministry of Education, Government of India. Available online at: https://onlinecourses.swayam2.ac.in/ugc19_ge03/preview

Tinto, V. (2010). “From theory to action: Exploring the institutional conditions for student retention,” in Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Cham: Springer), 51–89.

TNN (2023). Teachers Hard to Find But Schools Upgraded to English Medium in Rajasthan. Mumbai: The Times of India. Available online at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/teachers-hard-to-find-but-schools-upgraded-to-english-medium/articleshow/99802003.cms (Accessed April 27, 2023).

UNESCO (2020). COVID-19 Policy Brief: UN Secretary-General Warns of Education catastrophe. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Education Planning, News. Available online at: https://www.iiep.unesco.org/en/articles/covid-19-policy-brief-un-secretary-general-warns-education-catastrophe (Accessed August 4, 2020).

UNESCO (2022a). The COVID-19 Impact on Education. Paris: UNESCO. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (Accessed September 14, 2024).

UNESCO (2022b). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Education: International Evidence from the Responses to Educational Disruption Survey (REDS). Paris: UNESCO/International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

United Nations (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). New York City: United Nations.

World Economic Forum (2016). New Vision for Education: Fostering Social and Emotional Learning Through Technology. Amsterdam: Digital Industry Agenda.

Keywords: academic writing, first-year writing (FYW), writing across the curriculum (WAC), English for academic purposes (EAP), online classroom, online vs. in-classroom, Indian higher education

Citation: Kim J (2025) Things unchanged: online and offline practice of an Indian first-year composition curriculum. Front. Educ. 10:1514652. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1514652

Received: 21 October 2024; Accepted: 28 April 2025;

Published: 23 July 2025.

Edited by:

Andreas Lingnau, German University of Applied Sciences, GermanyReviewed by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaFrankie Har, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China

Shubham Pathak, Walailak University, Thailand

Copyright © 2025 Kim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jooyoung Kim, am9veW91bmcua2ltQGlpdGduLmFjLmlu

Jooyoung Kim

Jooyoung Kim