- School of Foreign Studies, Nankai University, Tianjin, China

Pre-task cultural knowledge preparation is crucial for ensuring the quality of interpreting. This study investigates the relationship between cultural knowledge preparation and the quality of consecutive interpreting, as well as the common methods used for such preparation. An A-B single group experiment was conducted with 30 postgraduates majoring in English interpreting in China, followed by one-on-one interviews with 8 participants. The experimental recordings were analyzed using SPSS, while the interview transcripts were subjected to content analysis. The findings indicate that overall interpreting quality improved after cultural preparation. Specifically, participants demonstrate significantly higher levels of information accuracy and technique usage, though professionalism shows no significant improvement. Participants report that preparation reduces mental stress, enhances speech comprehension, facilitates content anticipation, and allows for better coordination. The most effective method of cultural knowledge preparation involves obtaining relevant materials about the speaker, topics, and schedules from clients. When self-preparation is required, participants prefer bilingual audiovisual materials from authentic sources.

1 Introduction

Interpreting, by definition, is a communicative act that conveys information from one linguistic form to another through oral expression within a short time (Russell, 2005). It serves as a fundamental tool for intercultural and cross-ethnic communication in modern society (Won, 2019). With the increasing frequency of international trade and the rise of global conferences, interpreting has become increasingly crucial for facilitating cross-border communication (Angelelli, 2004). Consequently, interpreters, as cultural mediators, must not only excel in bilingual proficiency but also possess a deep understanding of diverse cultures (Albl-Mikasa, 2013). This cultural competence largely depends on thorough pre-task preparation (Walker and Shaw, 2011).

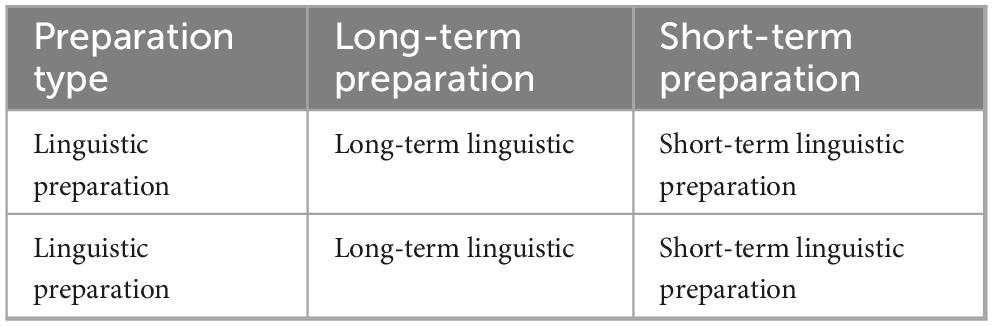

Currently, interpreting preparation is primarily categorized into two major classifications: long-term and short-term preparation (Pöchhacker and Shlesinger, 2002; Zhang, 2003), and linguistic and extra-linguistic preparation (Bühler, 1986; Gile, 1995).

In the field of interpreter training, long-term preparation is often discussed as the continuous development of key skills, bilingual competence, and broad knowledge across multiple disciplines (Seleskovitch and Lederer, 1995). Scholars have extensively examined various aspects of interpreter education, particularly for students majoring in languages. Some researchers take a macro-level approach, focusing on the design of long-term interpreter training programs (Ochberg, 2003). Others delve into specific techniques, such as note-taking in consecutive interpreting (Gillies, 2017) and shadowing exercises for simultaneous interpreting (Christoffels and De Groot, 2004), to enhance practical skills. The breadth of general knowledge required by interpreters across specialized fields has also attracted scholarly attention. Niska (2005) explores the knowledge base needed for different interpreting settings, while González and Auzmendi (2009) emphasize the importance of court interpreters’ familiarity with legal terminology and judicial procedures. These studies highlight the multifaceted nature of interpreter training, which must balance linguistic proficiency with domain-specific expertise.

In contrast, short-term preparation, commonly referred to as pre-task preparation, is a critical phase following the receipt of an interpreting assignment (Ma and Wu, 2008). Given that clients often come from distinct cultural or professional backgrounds, interpreters must undertake targeted preparation to address these specific contexts. This type of preparation is designed to “bridge the linguistic and extra-linguistic gap” (Will, 2007, p. 65) between interpreters and clients while also “reducing the cognitive load during the interpreting task” (Fantinuoli, 2017, p. 25). Studies on pre-task preparation typically focus on two main areas. One line of research includes practice reports that document the preparation strategies used for specific assignments (Ma, 2013; Zhang, 2018). Another examines the impact of preparatory factors on interpreting performance, often through experimental studies exploring the link between preparation and interpreting quality (Hale and Napier, 2013; Zhu, 2016). These investigations collectively underscore the importance of targeted, context-specific preparation in enhancing both accuracy and efficiency during interpreting tasks.

Another approach to categorizing preparation in interpreting distinguishes between linguistic and extra-linguistic elements (Bühler, 1986; Gile, 1995). Linguistic preparation encompasses both the long-term enhancement of bilingual proficiency and pre-task efforts focused on mastering relevant terminology (Liberman, 1970). Continuous improvement in both source and target languages is essential for interpreters to perform effectively. Prior to assignments, interpreters must familiarize themselves with task-specific terminology, as accuracy in terminology is crucial for high-quality interpreting. Lamberger-Felber and Schneider (2008) demonstrated that proper terminology preparation significantly improves interpreting quality across various domains. Scholars widely acknowledge that terminology mastery is especially important in specialized fields such as medical interpreting (Gile, 2009), and it also involves familiarizing oneself with stylistic nuances and in-house jargon (Fantinuoli, 2017).

Extra-linguistic preparation involves non-linguistic factors such as background knowledge, cultural awareness, and subject-specific information. While linguistic proficiency is fundamental, being bilingual alone does not suffice for effective interpreting. A deep understanding of the meaning behind words is equally important (Gillies, 2013; Kuwahata, 2005). For instance, even in one’s native language, comprehension can be hindered by unfamiliarity with a topic rather than the language itself. Gile’s (1995; 2009) comprehension model underscores that successful interpretation relies on a blend of linguistic knowledge, extra-linguistic knowledge, and analytical skills. This highlights the critical role that extra-linguistic knowledge plays in the interpreting process (Kuwahata, 2005).

The overlapping nature of the categorization mentioned above allows for consolidation into four primary research fields (Table 1). Cultural knowledge, which falls under the extra-linguistic category, refers to the “familiarization with various cultural characteristics, including values, beliefs, history, and social mores” (Igi Global., n.d., p.1). Current research has demonstrated a positive correlation between interpreters’ cultural knowledge, intercultural sensitivity, and their performance (see Angelelli, 2004; Gercek, 2007; Pistillo, 2003; Spencer-Oatey and Xing, 2008). For instance, the California Healthcare Interpreters Association identified four key roles for interpreters: message converter, message clarifier, cultural clarifier, and patient advocate. Spencer-Oatey and Xing (2008) analyzed how cultural factors influence interpretation within this framework, illustrating the close interconnection between language and culture, and showing that cultural factors actively “influenced their effectiveness as mediators of meaning” (p. 219). Pistillo (2003), focusing on liaison interpreting in business settings, highlighted the interpreter’s role as a cultural mediator. Similarly, Poyatos (1997) pointed out that unfamiliarity with specific cultures can lead to misunderstandings, violations of cultural taboos, and conflicts.

However, much of the cultural knowledge preparation discussed in these studies pertains to long-term cultural immersion. This raises the question: can cultural knowledge be effectively prepared in the short run? This study focuses on pre-task cultural knowledge preparation. Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, it aims to explore the relationship between pre-task cultural knowledge preparation and the quality of consecutive interpreting, as well as common approaches to pre-task cultural knowledge preparation. Accordingly, the study poses the following three research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Does pre-task cultural knowledge preparation improve the quality of consecutive interpreting?

RQ2: If RQ1 is supported, how does pre-task cultural knowledge preparation enhance interpreters’ interpreting quality?

RQ3: What are the common methods for interpreters to effectively enhance their cultural knowledge before interpreting tasks?

2 Methodology

This study employs a mixed-methods design, using a quantitative approach to address RQ1, and a qualitative approach to explore RQ2 and RQ3. It is worth mentioning that interpreting is generally divided into two modes: consecutive interpreting (CI) and simultaneous interpreting (SI) (Pöchhacker and Shlesinger, 2002). CI involves conveying the information in the target language “after the speaker has completed one or more ideas in the source language” (Russell, 2005, p. 135), while SI occurs almost concurrently with the speaker’s delivery of the source language. As interpreting training generally begins with CI to build foundational skills before progressing to SI, this study focuses on the consecutive mode.

Specifically, I conducted an A-B single-group interpreting experiment involving 30 first-year postgraduates majoring in English interpreting at the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE) in China, a program that has consistently ranked among the top five in the country for decades (Wang and Mu, 2009). Following the experiment, 8 participants voluntarily took part in one-on-one interviews. The experiment recordings were evaluated by two markers to assess whether cultural knowledge preparation improves interpreting quality, addressing RQ1. The interview recordings were transcribed and analyzed to explore both the reasons for the observed improvements in interpreting quality (RQ2) and the common methods of pre-task cultural knowledge preparation (RQ3).

2.1 Method 1—quantitative method

2.1.1 Hypothesis

To address RQ1, an interpreting experiment was conducted with the dependent variables set as overall interpreting performance and three specific criteria: information accuracy (50%), technique use (30%), and professionalism (20%). These criteria were drawn from the standard assessment framework of the Chinese National Interpreting Competition, a well-established platform recognized for evaluating interpreting proficiency among college students. Given its relevance for student interpreters, this framework was adopted for the study. Specifically, information accuracy assesses the completeness and accuracy of conveyed information, ensuring style, logic, and terminology align with the source text. Technique use evaluates the interpreter’s ability to apply interpretation skills, as well as the fluency and grammatical correctness of their target language output. Professionalism focuses on the interpreter’s voice quality and confidence. Based on these criteria, four alternative hypotheses (Hα) are proposed:

H1: Pre-task cultural knowledge preparation will improve participants’ overall interpreting performance.

H2: Pre-task cultural knowledge preparation will improve participants’ information accuracy.

H3: Pre-task cultural knowledge preparation will improve participants’ technique use. H4: Pre-task cultural knowledge preparation will improve participants’ professionalism.

2.1.2 Procedure

This study employed a convenience sample comprising first-year postgraduate students majoring in interpreting at the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE). Following ethical approval, the research project was introduced to the interpreting class, and the first 30 volunteers were selected for participation. All participants received an information sheet and signed a consent form prior to the experiment.

The experiment was conducted 1 week later in UIBE’s interpreting laboratory, using a single-group A–B pre-post design. This design was chosen to maintain internal consistency and minimize the impact of individual differences among participants. Although the absence of a control group limits external validity, the pre-post format facilitates clearer observation of performance changes attributable to the intervention.

Since all participants were Chinese, the experiment focused on English-to-Chinese interpreting to assess preparation for unfamiliar cultures. The procedure began with a demographic questionnaire, followed by distributing a glossary for two speeches. After testing the interpreting software, participants interpreted the first speech, and their responses were automatically recorded. Cultural materials were then provided for review over 30–40 min. Lastly, participants interpreted the second speech, with their responses again recorded by the software.

2.1.3 Materials

The materials used in this experiment included a demographic questionnaire, a glossary, two speeches, and a preparation sheet containing relevant cultural knowledge.

2.1.3.1 Demographic questionnaire

A brief questionnaire gathered participants’ demographic information through single-choice questions. The group comprises 10 males (33.33%) and 20 females (66.67%), all native Mandarin speakers and holders of the TEM-8 certificate, the highest English proficiency credential for English majors in China. Participants’ ages range from 23 to 28, with an average age of 24.07 years. They come from 18 different provinces, mostly from North, East, and Central China, aligning with the country’s overall population distribution. Regarding overseas experience, 24 participants have no study abroad experience. Of the 6 who have studied abroad, 5 are short-term exchange students, and 1 has completed an undergraduate degree in the U.S.

2.1.3.2 Glossary

To control for linguistic difficulty and focus specifically on the influence of extra-linguistic cultural knowledge, a bilingual glossary was provided for both speeches. Each glossary contained 13 potentially unfamiliar terms, primarily proper nouns such as names of people, places, and historical events, which are generally low in polysemy and unlikely to cause lexical ambiguity. The terms were selected to eliminate potential vocabulary-related barriers and were accompanied by their Chinese and English equivalents to ensure easy and consistent reference. This design aimed to reduce variation stemming from linguistic unfamiliarity, thereby allowing the study to isolate the impact of cultural knowledge preparation on interpreting performance.

2.1.3.3 Speeches

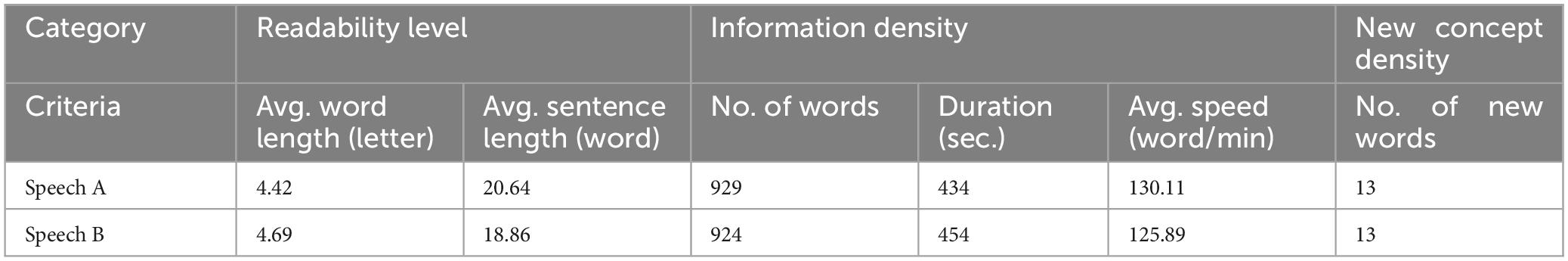

The two speeches selected for the experiment had the following characteristics: (1) Source: Both speeches were retrieved from Speechpool, a website providing interpreting practice materials. Originally part-funded by the UK’s National Network for Interpreting (NNI), Speechpool is now run voluntarily, and features speeches created by students for interpreting practice. The selected speeches summarize British history, delivered by the same British speaker with a suitable accent for consecutive interpreting training. (2) Style: The speeches are practical and narrative, focusing on explaining historical facts without presenting complex ideas or arguments. (3) Content: The speeches chronologically cover British history. The first speech discusses the names referring to the UK, the Union Jack, Britain under the Roman Empire, and the Hundred Years’ War. The second speech explores British colonial history, the Industrial Revolution, its governance model, and its decline as a world power. Participants were informed that the speeches were made in 2014, with references to David Cameron as Prime Minister and the absence of Brexit, but these political details did not affect the focus on cultural elements. (4) Difficulty: The two speeches are similar in comprehension level and information density. According to Gerver (2013), Liu and Chiu (2009), and Pöchhacker (2004), factors such as speaker characteristics, input speed, and material complexity affect speech difficulty. Both speeches were delivered by the same speaker, with consistent intonation and no background noise, minimizing extraneous variables. Using Liu and Chiu’s (2009) model, the speeches were evaluated for readability, information density, and new concept density, showing comparable difficulty levels (Table 2), making them appropriate for the experiment.

2.1.3.4 Preparation sheet

At the end of the first speech, the speaker mentioned, “Later on, in my next speech, I’ll continue on the same topic, but I’ll start with the colonial era and then move on to the centuries following that.” In line with this, the preparation sheet provides a broader overview, aiming to familiarize the participants with fundamental historical facts and the cultural background of British colonialism and the subsequent centuries. Two articles were selected for this purpose—one in English and one in Chinese. The English article, sourced from the website Encyclopedia Britannica, offers a comprehensive introduction to the history of the British Empire. It is divided into five sections: the origins of the British Empire, competition with France, the empire’s dominance and dominions, the rise of nationalism, and the evolution of the Commonwealth. The Chinese article, retrieved from the website History of China, is also an introductory piece. It explores the development of the British Empire across six areas: colonial America and Australia, free trade, global expansion, expansion in Asia, expansion in Africa, and the empire’s zenith. It then discusses the decline of the empire and provides an objective evaluation. Both articles serve as overviews rather than delving into specific historical events or personal viewpoints. The preparation sheet does not directly align with the structure of the second speech, and there is limited overlap in content, which is consistent with general pre-task preparation practices.

2.1.4 Interpreting assessment

After receiving the recordings from all 30 participants, I anonymized and numbered them. The recordings for Speech A were labeled P1–P30, corresponding to the 30 participants, while those for Speech B were labeled P31–P60. These recordings were then given to two markers, who evaluated them based on the standard assessment criteria of the Chinese National Interpretation Competition: information accuracy (50%), technique use (30%), and professionalism (20%). The final score for each participant was calculated as the average of the two markers’ scores. Both markers were experienced professional interpreters. The first, a female, holds the highest level of the National Interpreting Certificate in China and has a deputy senior title, with extensive interpreting experience. The second, a male, has worked as a professional interpreter at over 100 conferences, with clients including the former Prime Minister of Australia, the APEC Summit, and the embassies of Kenya and South Sudan. To ensure objectivity and reliability, the markers were instructed to grade solely according to the specified criteria, without knowledge of the research topics or questions. The final scores were then analyzed quantitatively using SPSS.

2.2 Method 2—qualitative method

2.2.1 Participants

The interview participants were selected from those who took part in the interpreting experiment through convenience sampling. After the experiment, 8 volunteers (4 males and 4 females) expressed their willingness to participate in the interview. All 8 participants completed the consent form and information sheet for the qualitative study. They came from various provinces across China, including Fujian, Hunan, Hebei, Liaoning, Gansu, Heilongjiang, Tianjin, and Guangdong. Among the 8 interviewees, 7 were between the ages of 23 and 24 and had not studied abroad, while one participant, aged 28, had spent 4 years in the United States.

2.2.2 Interview design

The interview was designed to explore participants’ reflections on the experiment and their daily experiences with cultural knowledge preparation, addressing RQ2 and RQ3, respectively. Accordingly, the interview was divided into two main parts.

The first part, aimed at addressing RQ2, focused on participants’ reflections on the interpreting experiment. The questions are as follows: (1) What do you think of your interpreting performance? Why? (2) Which performance do you think was better, the first or the second? Why? (3) How did you use the preparation sheet for the experiment? (4) How helpful do you think the preparation sheet was? If you were to prepare the materials yourself, what would you choose? (5) What cultural factors do you think were involved in the experiment? Did they cause challenges in your interpreting? How did you overcome them?

The second part, aimed at addressing RQ3, extended the discussion from the experiment to participants’ daily interpreting practices, focusing on how they prepared cultural knowledge for interpreting tasks. The questions are as follows: (1) What should be included in pre-task preparation for interpreting? (2) Specifically, what should be included in cultural knowledge preparation before an interpreting task? (3) Could you share your past experiences with pre-task preparation? (4) In your opinion, what aspects of cultural knowledge should be included in interpreting preparation?

The interview was conducted using a semi-structured format, which allowed for flexibility. While the questions are based on the pre-set list, as the interviewer, I also asked follow-up questions based on participants’ responses to gather more in-depth and comprehensive information.

2.2.3 Analysis method

After receiving the recordings from the 8 participants, I anonymized and numbered them from I1 to I8. I then transcribed and translated the interviews into English. Next, I conducted content analysis to “transform large amounts of text into an organized and concise summary of key findings” (Erlingsson and Brysiewicz, 2017, p.94). The interview data were used to explore the reasons behind the experimental results and common methods of cultural knowledge preparation, so I used summative content analysis. I underlined units that explained why participants performed better after cultural knowledge preparation, and shaded those indicating common preparation methods. Then, I summarized keywords from these units, developed a coding scheme based on them (Bengtsson, 2016), and finally categorized the codes for further analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative results

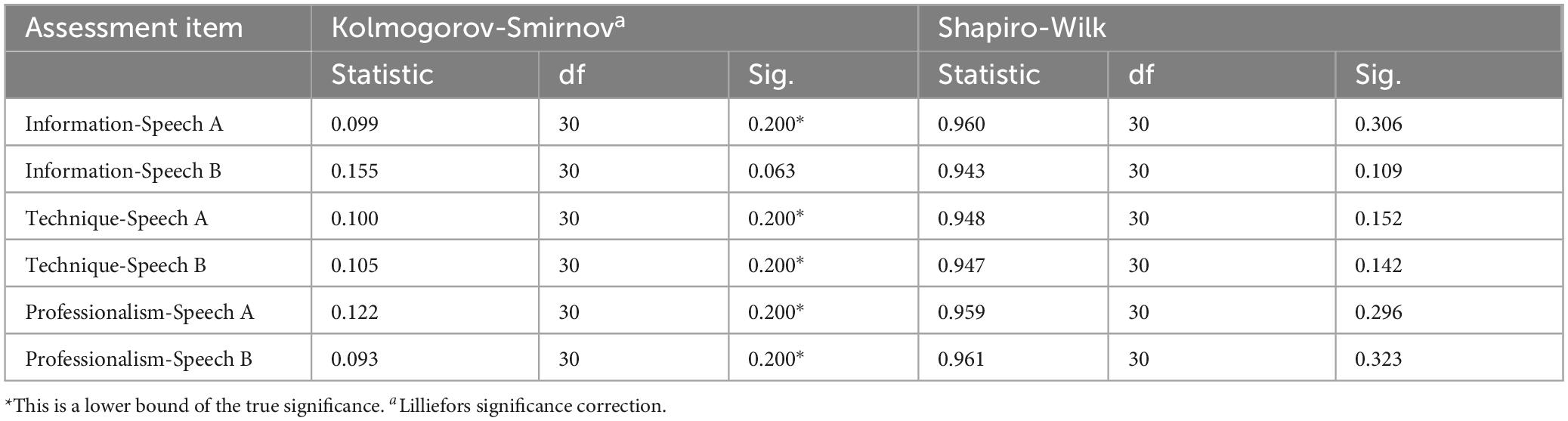

The Shapiro-Wilk test in SPSS shows that the data for both Speech A (p = 0.14) and Speech B (p = 0.08) are normally distributed, as are the scores for the three assessment criteria in both speeches (Table 3). Therefore, “section 3.1.1 Sample demographics” uses an independent samples t-test to report sample demographics, while “section 3.1.2 Paired samples T-test analysis” presents the results of paired samples t-tests to examine the four hypotheses.

3.1.1 Sample demographics

Three demographic variables—gender, age, and overseas study experience—are analyzed using independent samples t-tests for both speeches. Overall, no significant differences are found between participants based on gender, age, or overseas study experience in either Speech A or Speech B.

For gender, participants are divided into two groups: males (10 participants) and females (20 participants). The independent samples t-test shows no significant difference in scores for Speech A between females (M = 81.28, SD = 7.44) and males (M = 80.45, SD = 7.87); t(29) = −0.28, p = 0.779. Similarly, there is no significant difference in scores for Speech B between females (M = 83.00, SD = 6.85) and males (M = 81.99, SD = 7.98); t(29) = −0.36, p = 0.721.

Regarding age, participants range from 23 to 28 years old. They are divided into two groups: group A consists of 22 participants aged 23–24 years (no gap year), and group B includes 8 participants aged 25–28 years [with gap year(s)]. The independent samples t-test indicates no significant difference in Speech A scores between the 23–24 year-olds (M = 80.38, SD = 7.34) and the 25–28 year-olds (M = 82.71, SD = 8.03); t(29) = −0.75, p = 0.458. Similarly, there is no significant difference in Speech B scores between the 23–24 year-olds (M = 82.20, SD = 6.79) and the 25–28 year-olds (M = 83.94, SD = 8.32); t(29) = −0.58, p = 0.562.

Lastly, for overseas study experience, 24 participants who have not studied abroad form group A, while 6 participants with overseas study experience form group B. The independent samples t-test reveals no significant difference in Speech A scores between group A (M = 80.88, SD = 7.47) and group B (M = 81.50, SD = 8.12); t(29) = 0.18, p = 0.858. Likewise, there is no significant difference in Speech B scores between group A (M = 82.60, SD = 7.12) and group B (M = 82.93, SD = 7.80); t(29) = 0.09, p = 0.928.

3.1.2 Paired samples T-test analysis

Overall, among the four hypotheses, H1, H2, and H3 are supported, while H4 is rejected based on the results of the paired samples t-test. Specifically, participants show a significantly higher level of interpreting performance after cultural knowledge preparation (M = 82.66, SD = 7.12) compared to before the intervention (M = 81.00, SD = 7.46), t(29) = −6.11, p < 0.001, with a small effect size, d = 0.23.

For the three specific assessment criteria, participants demonstrate a significantly higher level of information accuracy after cultural knowledge preparation (M = 83.57, SD = 7.34) compared to before (M = 81.15, SD = 7.83), t(29) = −6.68, p < 0.001, with a small effect size, d = 0.32.

Participants also show a significantly higher level of technique use after cultural knowledge preparation (M = 79.80, SD = 8.65) compared to before (M = 78.25, SD = 9.04), t(29) = −4.47, p < 0.001.

However, participants do not show a statistically significant improvement in professionalism after cultural knowledge preparation (M = 84.70, SD = 6.66) compared to before (M = 84.75, SD = 6.87), t(29) = 0.192, p = 0.849.

3.2 Qualitative results

The interview data reveal that the interviewees generally felt their interpreting performance improved after cultural knowledge preparation. Addressing RQ2 and RQ3, “section 3.2.1 Self-reflection on interpreting performance” presents the interviewees’ reflections on the reasons behind the improvement in interpretation quality, while “section 3.2.2 Daily experience of cultural knowledge preparation” highlights their experiences with cultural knowledge preparation before interpreting tasks.

3.2.1 Self-reflection on interpreting performance

All interviewees indicated that their interpreting quality improved to some extent after cultural knowledge preparation. The reasons for this improvement can be categorized into three areas: effort coordination and comprehension, psychological relief, and anticipation.

First, the primary factor contributing to the performance differences between the two interpretations is effort coordination and comprehension. Interpreters are required to manage listening, comprehension, note-taking, and note-reading simultaneously (Gile, 2009). Most interviewees note that familiarity with cultural materials directly affects the time they spend understanding and memorizing the speech. Some also mention encountering difficulties in retrieving information and reading notes prior to preparation, which results in lower-quality interpreting.

Second, nearly all interviewees reported feeling less stressed during the second interpreting. Without cultural knowledge preparation, many felt nervous or anxious, and worried about their ability to understand or interpret the speech accurately. However, after reviewing the cultural materials, they experienced an enhanced sense of psychological readiness, which contributed to their improved performance during the second interpretation.

Finally, interviewees expressed that preparation increases their familiarity with UK culture and history, aiding their ability to anticipate content during the second speech. When the speaker references historical events, interpreters can draw on their prepared knowledge to predict what will follow. This alleviates the burden of listening and note-taking, making the process of reading notes smoother.

3.2.2 Daily experience of cultural knowledge preparation

In reflecting on their daily interpreting practice and experimental experiences, interviewees discussed the process of preparing cultural knowledge before interpreting. Most interviewees admitted to frequently overlooking this aspect of preparation. Based on the extracted keywords and coding scheme, their reflections on cultural knowledge preparation can be categorized into three areas: preparation sources, preparation content, and preparation methods.

First, regarding preparation sources, all interviewees agreed that obtaining first-hand materials from clients is the most efficient and accurate way to prepare. However, in most cases, the information provided by clients is limited, requiring interpreters to conduct self-preparation as well (Fantinuoli, 2017). For self-preparation, most interviewees preferred using materials from authentic sources. For example, when searching for English materials, they favored Google over Baidu (a Chinese search engine), believing that Google provides more accurate English content. They also preferred official or certified websites for reliability.

Second, in terms of preparation content, interviewees noted that clients typically provide information about guest introductions, speech topics, and schedules. Interpreters then need to further explore relevant cultural factors, such as the guests’ cultural background, table manners, cultural jokes, and potential cultural misunderstandings in the speech drafts. Many interviewees acknowledged that they often overlooked key cultural elements, such as guests’ religious beliefs or cultural taboos, which led to challenges during interpreting and, at times, cultural conflicts.

Third, when it came to preparation methods, interviewees tended to seek out audio-visual materials closely related to the interpreting task. In terms of language choice, they agreed that bilingual materials were essential, but they usually began with resources in their native language. During the interpreting task itself, they organized pre-collected materials into bullet points or summaries to quickly reference during interpreting.

4 Discussion

4.1 Insights from the interpreting experiment: comprehension, effort, and professionalism

Addressing RQ1, the experiment results show that pre-task cultural knowledge preparation improves overall performance, information accuracy, and technique use in consecutive interpreting. However, the dimension of professionalism—particularly in terms of vocal delivery and rhetorical presence—exhibits no statistically significant enhancement.

In addressing RQ2, which investigates the underlying causes of the observed improvement in interpreting quality, this study draws on Gile’s comprehension and effort models for theoretical grounding. Additionally, psychological factors and prediction play a crucial role in applying the effort model.

According to Gile’s comprehension model (2009), comprehension (C) is facilitated by language knowledge (KL), extra-linguistic knowledge (ELK), and analysis (A), expressed as “C = KL + ELK + A.”

In the first speech, many interviewees report difficulties in fully understanding the content. The absence of cultural knowledge preparation has a profound impact on their comprehension. Comprehension is undeniably crucial in consecutive interpreting (Ilg and Lambert, 1996), yet shallow comprehension is insufficient. Interpreting without genuine understanding and analysis results in a superficial interpretation, akin to word substitution (Jones, 2014). One respondent illustrated this by mentioning that although the terms “St. George/圣乔治” and “St. Andrew/圣安德鲁” are provided in both English and Chinese on the glossary sheet, when she hears “the flag of St. George” and “the cross of St. Andrew” during the first speech, she took notes but still cannot grasp their meaning upon reviewing them.

“The flag is of course in the union flag or the Union Jack as it is sometimes referred to. It is made up of three different flags laid one on top of the other. There is the English flag which is the flag of St. George, red cross on the white background. There is the former flag of Ireland, and then there is the Scottish flag which is a blue background with the cross of St. Andrew. (Speech 1, para. 4)”

Although both phrases can be literally translated into Chinese, she reported unfamiliarity with the term ‘圣乔治旗’ (St. George flag) in Chinese discourse, perceiving it as semantically opaque due to its limited exposure in domestic educational or media contexts. When she heard “St. Andrew cross”, she associated the word “cross” with “the shape of an X”, without realizing that it is one of the most important Christian symbols. This lack of cultural knowledge creates barriers to comprehension. When I showed her the four flags mentioned in the speech (Figure 1), she immediately understood them and remarked that had she seen the images before interpreting, she would not misinterpret them. Therefore, the key reason for the poor interpreting quality stems from insufficient comprehension of the original speech.

Gile’s effort model (2009) for consecutive interpreting consists of two phases: the listening and reformulation phase, followed by the reconstruction phase. In the first phase, CI = L + M + N + C, which means interpreters must listen and analyze the speech (L), memorize it (M), take notes (N), and coordinate these efforts (C). In the second phase, CI = Rem + Read + P, where interpreters retrieve information from short-term memory (Rem), read their notes (Read), and produce the target language speech (P).

As respondents devote considerable time to listening for comprehension and analysis, problems often arise in the subsequent stages due to the need to simultaneously manage multiple tasks.

In the first phase, short-term memory (M) relies heavily on accumulated knowledge and comprehension of the original text. Interpreters lacking knowledge of English history and culture struggle to retain all the information and take logical notes. In the second phase, without sufficient knowledge reserves, respondents find it difficult to extract information solely from their notes and memory, leading to omissions and misinterpretations—particularly regarding historical facts. For example, many participants are unable to correctly interpret “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland”(大不列颠及北爱尔兰联合王国), frequently using the abbreviation “UK” (英国) instead and being unfamiliar with the full name. However, such errors can be avoided with prior preparation.

After cultural knowledge preparation, interpreters’ understanding of the content improves significantly, which is reflected in greater accuracy regarding basic historical facts. This improvement is also the main reason for the enhanced overall information accuracy. Cultural knowledge preparation additionally lightens the listening burden, allowing more time for logical note-taking. During the second phase, retrieving information and reading notes are not solely dependent on the listening process but are supplemented by pre-task preparation materials, greatly improving efficiency.

In addition to the factors outlined in the model, psychological factors also play a crucial role. Xue (2014) notes that psychological stress negatively affects interpreters’ performance, leading to tension, anxiety, lack of confidence, panic, and other detrimental emotions. Such stress can significantly disrupt attention stability (Pöchhacker, 2016). Novice interpreters, in particular, are more prone to stress without adequate pre-task preparation (Gillies, 2013). Comprehensive preparation is an effective way for interpreters to manage on-the-spot stress, allowing them to focus more on interpreting skills and language use (Wang, 2009). In this experiment, participants report feeling less stressed during the second interpreting, which is reflected in improved interpreting techniques. With preparation, interpreters have more mental bandwidth to refine their target language expression, and some even begin using more idiomatic Chinese expressions, such as four-character phrases, in the second round of interpretation.

Prediction also plays a key role in interpreting. Although the prepared materials are not identical to the actual speech, the themes are aligned. This allows interpreters to become familiar with the topic, facilitating predictions during the speech and reducing the cognitive load associated with listening and analysis (Demers, 2005). In the first phase, prediction primarily helps with listening. For instance, after hearing “one group left England in 1620 as a result of religious persecution,” an interpreter predicted that the speaker was referring to the Mayflower, as they have reviewed relevant materials beforehand. This helps ease the burden of listening.

“For example, one group left England in 1620 as a result of religious persecution. These people were, of course, the Puritans who traveled across the Atlantic on their ship which was the Mayflower. (Speech 2, para.2)”

In the second phase, the effort focuses primarily on note-reading. For unclear sections in listening or notes, interpreters can use their prepared knowledge to aid in analysis (Demers, 2005). In this study, there are fewer errors related to basic historical facts in the second interpreting.

However, the level of professionalism does not improve significantly. Previous studies suggest that an interpreter’s voice quality is closely linked to their mental state (Grbić, 2008; Wang, 2009). Yet, many interviewees mention that their psychological tension eases significantly after preparation. So, what might be the causes of this discrepancy? Several factors could explain it. Firstly, the experiment takes place in a relatively relaxed environment rather than in high-stakes professional settings like exams or competitions. As a result, students may not take it seriously enough, leading to less professional-sounding voice delivery. Secondly, participants are not informed of the three assessment criteria. If they know that voice quality is one of the scoring elements, they might pay more attention to it. Lastly, the evaluators only assess interpreters based on their voice recordings. Unlike on-the-spot judgment, evaluating recordings alone may not fully capture subtle differences in professionalism.

4.2 Patterns and preferences in cultural knowledge preparation

In addressing RQ3, this study examines the sources, formats, and key considerations for cultural knowledge preparation based on interview data.

From the perspective of sources, scholars widely agree (Bao, 2011; Gercek, 2007; Walker and Shaw, 2011; Zhang, 2003) that interpreters should first seek materials directly from clients, a view supported by interview findings. Zhang (2013) categorizes client-provided materials into three types: (1) Explicit materials, where interpreters receive detailed information, including speeches, schedules, and background materials. (2) Ambiguous materials, where interpreters are provided only partial details, such as the general theme, target audience, and schedule, but not complete background information. (3) Unknown materials, where the interpreter is informed only of the basic logistical details (e.g., guest, time, location) due to confidentiality concerns.

When engaging in self-preparation, respondents generally favored authentic sources, often choosing Google over Baidu to access unrestricted content. They prioritized using authoritative websites and, when time allowed, cross-checked information from multiple channels (Gillies, 2013). If uncertainties remained, interpreters could clarify by consulting the speaker or subject matter experts before the assignment.

Regarding preparation formats, while traditionally interpreters have relied on reading topic-related texts (Fantinuoli, 2017), interviewees expressed a clear preference for audio-visual materials. These materials allow interpreters to simulate real-time listening and note-taking, thereby reducing cognitive load during actual interpretation (Zhu, 2016). Respondents also stressed the importance of preparing bilingual materials to expedite the process of language conversion. Pre-translation or preliminary interpretation of materials, where feasible, was seen as an effective strategy for enhancing performance. During the interpretation task itself, interpreters favored organizing their prepared materials in bullet-point form or concise summaries for ease of reference (Gillies, 2013).

When preparing for specific speakers, it is critical to understand the speaker’s background, including their accent, religion, and cultural practices (Gillies, 2013). Interviewees noted particular challenges with interpreting non-native English accents, such as Indian or Japanese accents, which are often influenced by the speaker’s native language (Wells, 2005). Familiarity with a speaker’s religious beliefs and cultural norms is equally important to prevent cultural misunderstandings (Poyatos, 1997). For example, one participant recounted a case of misinterpreting the Jewish term “Kipa” as “Kappa,” a sports brand, due to a lack of knowledge of Jewish customs.

In terms of the itinerary, interpreters must be cognizant of potential cultural taboos, particularly those related to meals, to avoid offending guests with specific dietary restrictions tied to religious or cultural practices (Dillon, 2013; Fischer, 2016). For instance, arranging a meal at a non-Muslim restaurant could be perceived as disrespectful to Muslim guests. As cultural intermediaries, interpreters are responsible for ensuring cross-cultural sensitivity and mitigating misunderstandings between parties (Angelelli, 2004).

Cultural preparation also entails addressing cultural gaps and cross-cultural humor. Cultural gaps are the differences between two cultures that hinder mutual understanding (Valdes, 1986), as exemplified by the divergent symbolism of the “dragon” in Chinese and Western cultures (Xie, 2007). Cross-cultural humor presents additional challenges, as humor styles vary widely across cultures. Interviewees frequently mentioned the difficulty of interpreting humor, particularly when it relies on linguistic features such as homophones or visual puns, which often do not translate effectively (Wang, 2014).

To manage these challenges, interpreters must engage in long-term knowledge accumulation and comprehensive pre-task preparation. Whenever possible, interpreters should pre-interpret speeches or, at the very least, anticipate potential cultural issues based on the speaker’s background and the topic at hand. This proactive approach is essential for addressing cultural obstacles and ensuring more effective interpretation.

5 Conclusion

This study quantitatively investigates whether cultural knowledge preparation enhances consecutive interpreting performance, and qualitatively explores the underlying reasons for such improvement as well as common preparation strategies. The findings indicate that cultural knowledge preparation significantly improves interpreting performance, particularly in terms of information accuracy and technique use. However, it has limited impact on the dimension of professionalism. These results can be interpreted through Gile’s Comprehension and Effort Models (2009): a lack of cultural knowledge hampers comprehension and increases the cognitive burden of coordinating tasks such as listening, memory, and note-taking. Psychological factors, such as anxiety and cognitive overload, also contribute—novice interpreters without prior preparation are more susceptible to performance issues due to heightened stress. In contrast, preparation facilitates content prediction and reduces processing effort.

The limited improvement in professionalism may be attributed to participants’ lack of awareness regarding voice quality as an evaluation criterion, the informal nature of the experimental setting, and the fact that performance was assessed solely through audio recordings, which may not fully capture nuances in delivery.

This study also identifies common methods for cultural preparation, including reviewing relevant materials, researching the speaker’s cultural background, and familiarizing oneself with culturally embedded content. Practical techniques include using authentic audiovisual materials in both working languages and pre-translating or summarizing the speech.

Nevertheless, the study is limited to student and novice interpreters. Future research should explore cultural knowledge preparation in the context of professional interpreters. Furthermore, while this study focuses on cultural elements in speech content, other factors—such as the speaker’s cultural background, the use of idiomatic expressions, and cross-cultural humor—also deserve systematic investigation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of International Business and Economics. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albl-Mikasa, M. (2013). Developing and cultivating expert interpreter competence. Int. Newslett. 18, 17–34.

Angelelli, C. V. (2004). Revisiting the interpreter’s role: a study of conference, court, and medical interpreters in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2, 8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Bühler, H. (1986). Linguistic (semantic) and extra-linguistic (pragmatic) criteria for the evaluation of conference interpretation and interpreters. Multilingua 5, 231–235. doi: 10.1515/mult.1986.5.4.231

Christoffels, I. K., and De Groot, A. M. (2004). Components of simultaneous interpreting: Comparing interpreting with shadowing and paraphrasing. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 7, 227–240. doi: 10.1017/S1366728904001609

Demers, H. (2005). The working interpreter. Benjamins Trans. Lib. 63, 203–230. doi: 10.1075/btl.63.13dem

Dillon, M. (2013). China’s Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. London: Routledge.

Erlingsson, C., and Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 7, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

Fantinuoli, C. (2017). Computer-assisted preparation in conference interpreting. Trans. Interpret. 9, 24–37. doi: 10.12807/ti.109202.2017.a02

Fischer, J. (2016). Markets, religion, regulation: Kosher, halal and Hindu vegetarianism in global perspective. Geoforum 69, 67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.12.011

Gercek, S. E. (2007). “Cultural mediator” or “scrupulous translator”? Revisiting role, context and culture in consecutive conference interpreting,” in Translation and its others. selected papers of the CETRA research seminar in translation studies. Available online at: https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cetra/old-website/papers/files/eraslan-gercek.pdf

Gerver, D. ed. (2013). Language interpretation and communication. London, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

Gile, D. (1995). Fidelity assessment in consecutive interpretation: An experiment. Target. Int. J. Trans. Stud. 7, 151–164. doi: 10.1075/target.7.1.12gil

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training: Revised edition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

González, E., and Auzmendi, L. (2009). Court interpreting in basque. mainstreaming and quality: the challenges of court interpreting in basque. Crit. Link 5: Qual. Interpret. Shared Responsibil. 87, 135–148. doi: 10.1075/btl.87.11gon

Grbić, N. (2008). Constructing interpreting quality. Interpret. Int. J. Res. Practice Interpret. 10, 232–257. doi: 10.1075/intp.10.2.04grb

Hale, S., and Napier, J. (2013). Research methods in interpreting: A practical resource. London: A&C Black.

Igi Global. (n.d.). What is cultural knowledge. Available online at: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/cultural-knowledge/57507

Ilg, G., and Lambert, S. (1996). Teaching consecutive interpreting. Interpreting. 1, 69–99. doi: 10.1075/intp.1.1.05ilg

Kuwahata, M. (2005). Sink or swim: Five basic strokes to EJ consecutive interpreting. Interpret. Stud. 5, 173–181. doi: 10.50837/istk.0508

Lamberger-Felber, H., and Schneider, J. (2008). “Linguistic interference in simultaneous interpreting with text: A case study,” in Efforts and models in interpreting and translation research: A tribute to Daniel Gile, eds G. Hansen, A. Chesterman, and H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 215–236.

Liberman, A. M. (1970). The grammars of speech and language. Cogn. Psychol. 1, 301–323. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(70)90018-6

Liu, M., and Chiu, Y. H. (2009). Assessing source material difficulty for consecutive interpreting: Quantifiable measures and holistic judgment. Interpreting 11, 244–266. doi: 10.1075/intp.11.2.07liu

Ma, L. (2013). The Importance of pre-interpreting preparation in consecutive interpreting—A practice report on interpreting for participants of APEC Seminar on Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation. Master’s thesis, Ningxia University: China.

Ma, Z. G., and Wu, X. D. (2008). Interpreting performance under different task-planning conditions. Babel 54, 201–233. doi: 10.1075/babel.54.3.01ma

Niska, H. (2005). Training interpreters. Train. New Millennium: Pedagog. Trans. Interpret. 60:35. doi: 10.1075/btl.60.07nis

Ochberg, R. (2003). “Teaching interpretation,” in The narrative study of lives. Up close and personal: The teaching and learning of narrative research, eds R. Josselson, A. Lieblich, and D. P. McAdams (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 113–133.

Pistillo, G. (2003). The interpreter as cultural mediator. J. Intercult. Commun. 3:1011. doi: 10.36923/jicc.v3i2.389

Pöchhacker, F. (2004). “I in TS: On partnership in translation studies,” in Gaps and synergies, ed. C. Schäffner (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.).

Pöchhacker, F., and Shlesinger, M. (eds) (2002). The interpreting studies reader. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Poyatos, F. (1997). The reality of multichannel verbal-nonverbal communication in simultaneous and consecutive interpretation. Benjamins Trans. Lib. 17, 249–282. doi: 10.1075/btl.17.21poy

Russell, D. (2005). Consecutive and simultaneous interpreting. Benjamins Trans. Lib. 63, 135–164. doi: 10.1075/btl.63.10rus

Seleskovitch, D., and Lederer, M. (1995). A systematic approach to teaching interpretation. Alexandria, VA: Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf.

Spencer-Oatey, H., and Xing, J. (2008). 11. The impact of culture on interpreter behaviour. Handb. Int. Commun. 7:219. doi: 10.1515/9783110198584.2.219

Valdes, J. M. (ed.) (1986). Culture bound: Bridging the cultural gap in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walker, J., and Shaw, S. (2011). Interpreter preparedness for specialized settings. J. Interpret. 21:8.

Wang, B., and Mu, L. (2009). Interpreter training and research in mainland China: Recent developments. Interpreting 11, 267–283. doi: 10.1075/intp.11.2.08wan

Wang, S. (2009). On pre-conference preparations in conference interpreting. J. Hebei North Univ. (Social Science Edition) 3, 15–17.

Wang, Y. (2014). Humour in British academic lectures and Chinese students’ perceptions of it. J. Pragmat. 68, 80–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.05.003

Wells, J. C. (2005). Goals in teaching english pronunciation. Eng. Pronunciat. Models: Chang. Scene 101–110.

Will, M. (2007). “Terminology work for simultaneous interpreters in LSP conferences: Model and method,” in Proceedings of the EU-High-Level Scientific Conference Series MuTra, 65–99. Available online at: https://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2007_Proceedings/2007_Will_Martin.pdf

Won, J. H. (2019). “The past, present, and future of interpreting studies in Korea,” in Translating and Interpreting in Korean Contexts: Engaging with Asian and Western Others. London: Routledge, 219–237.

Xue, M. (2014). Factor affecting interpretation quality and solutions. Doctoral dissertation, Shanghai International Studies University: China.

Zhang, J. (2003). Research on interpreter’s preparation work. Chin. Sci. Technol. Trans. J. 3, 13–17.

Zhang, X. (2018). Pre-interpretation preparation in consecutive interpreting—A practice report on interpreting for the China-ASEAN Science and Technology Industry & Enterprises Cooperation Conference. Master’s thesis, China Foreign Affairs University: China.

Zhang, Y. (2013). Predication, association and task frame-The keys to the preparation of interpreting tasks. J. Baotou Vocat. Tech. College 14, 50–52.

Keywords: consecutive interpreting, pre-task preparation, cultural knowledge, Chinese graduates, empirical study

Citation: Sun J (2025) Pre-task cultural knowledge preparation and its effects on consecutive interpreting quality: an empirical study among Chinese postgraduates. Front. Educ. 10:1517411. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1517411

Received: 26 October 2024; Accepted: 19 May 2025;

Published: 06 June 2025.

Edited by:

Alberto Nolasco Hernandez, University of Zaragoza, SpainReviewed by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaHassan Ahdi, Global Institute for Research, Education & Scholarship, Netherlands

Copyright © 2025 Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Sun, c3VuamluQG1haWwubmFua2FpLmVkdS5jbg==

Jin Sun

Jin Sun