- Faculty of Education Sciences and Psychology, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia

The Latvian education system is facing a severe teacher shortage due to causes such as an ageing teaching workforce, high workloads, inadequate salaries and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. To help address the lack of trained teachers, a specialised professional development programme of 72 academic hours, Fundamentals of Pedagogical Activity, has been implemented. The initiative aims to provide individuals with professional skills the chance to engage in teaching activities across general, vocational, and interest-based education sectors. This study, conducted from 2016 to 2023, sought to evaluate the programme’s effect on participants’ development of professional skills and their motivation to pursue a career in teaching. The research uses a descriptive method approach with questionnaires and focus group discussions explores participants’ motivations for enrolling in the programme and the effect on their professional development. Fundamentals of Pedagogical Activity participants expressed strong interest in improving teaching skills and obtaining a teaching certificate in order to pursue significant career progress and continued professional growth after finishing the programme.

1 Introduction

Teacher shortages are a global problem, with the UNESCO Institute for Statistics estimating that more than 68 million new teachers will be needed worldwide by 2030 (UNESCO, 2022). Latvia is no exception, where the teacher shortage has been an issue for several years. A 2023 survey by Latvia’s Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) showed a total of 1,013 teacher vacancies at the beginning of the 2023/2024 school year (Laganovskis, 2023).

In the 2022/2023 school year, there were 28,277 teachers in general education schools (State Education Information System Latvia, 2024), of whom 8,921 worked part-time, 2,622 were approaching retirement age and would soon leave the profession, 40 had recently graduated, and 181 were currently continuing their studies. The turnover rate for new teachers was 1% of the total workforce in the field (Laganovskis, 2023). According to a survey by the Latvian Education and Science Employees’ Union, 38% of young educators are thinking about leaving the teaching profession in the next 5 years (LIZDA, 2022).

Since 2014, Latvia has seen an increase in the average age of teachers: The International Learning Environment Survey OECD TALIS reveals that the average age of Latvian teachers in 2018 was 48 years, and 51% of Latvian teachers are older than 50 (Geske, 2019). This means that Latvia will need to replace every second teacher within the next decade. In recent years, there has not been a significant generational turnover among teachers. Therefore, considering current trends in workforce dynamics and organisational change management—such as the adaptation to new teaching technologies, shifting educational policies, and the integration of younger professionals into the teaching workforce—such a transition can be anticipated in the near future. It is anticipated that the change of generation of teachers will not be fast. One of the unexpected factors is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which worsened the situation in the country. The current increase in teacher vacancies needs to be addressed to ensure quality education in schools. More than 400 teaching vacancies open up in Latvia’s schools every year and must be filled at the start of the new school year. As of 24 May 2023, 771 vacancies in general education schools have been published on the ‘Be a Teacher’ portal. Of these, 669 are teaching vacancies and the rest are support and managerial staff vacancies (School vacancy map,1 Vacancy list).2

2 Theoretical background

The academic literature identifies various factors that contribute to teacher shortages, such as inadequate professional development support and recognition, challenging school environment, poor student behaviour, lack of administrative support, ‘top-down’ organisational management culture and low pay (Humphrey et al., 2018). Workload is ranked as the most important factor influencing teachers’ decision to leave, followed by stress and illness, school administration policy and approaches, government policy and professional development opportunities (Department for Education, UK Government, 2018, p. 22).

Teacher shortage tends to have a negative impact on pupils, teachers and the education system as a whole. The lack of competent teachers undermines pupils’ ability to learn and acquire essential skills, negatively affecting their academic performance (McKenna, 2018). Teacher shortage also contributes to high teacher turnover and a decline in teacher effectiveness and quality due to the resulting heavy workloads divided among fewer educators (Humphrey et al., 2018).

In response to the global teacher shortage, various approaches are being implemented —such as increasing salaries, developing alternative certification programmes, establishing career transition initiatives, and recruiting teachers from other countries (Casey, 2019). In this article, the authors focus specifically on alternative teacher preparation programmes that enable certification to be achieved in a shorter timeframe than traditional methods.

This study used a combination of descriptive qualitative and quantitative research methods to assess the level of impact of the Fundamentals of Pedagogy Activity, seeking to answer the following research question.

Research Question: Is the Fundamentals of Pedagogical Activity programme an effective solution for addressing the teacher shortage in schools?

3 Background

A basic familiarity with the Latvian education system is necessary to understand the significance of the findings in this research study. Over the last several years, Latvia’s education system has seen several significant changes, more so since 2004 when it joined the European Union (EU). Like most EU countries, its education system is structured into four distinct levels including pre-school, basic/primary, secondary and tertiary (AIC, 2018). The types of education in Latvia are: (1) general education, (2) vocational education, and (3) academic education. Schools are primarily state-funded, although there are a few private and international schools. Students remain in general education for 12 years, with 9 years being dedicated to compulsory basic education, and 3 years to secondary (pre-school is part of general education in Latvia). Students may further pursue tertiary education, including vocational training, undergraduate, and graduate programmes.

Level one (pre-school) education is typically for children between the ages of 1.5 and 7, and focuses on helping learners improve their social and cognitive development. Although attending pre-school is largely optional, especially in the earlier ages of one to four, learners aged five and six must attend pre-school before enrolling for primary school. Depending on the child’s health and psychological readiness—and based on both the parent’s preferences and the family doctor’s assessment—the duration of the preschool programme can be either extended or shortened. The next level, primary school, comprises grades one to six and lasts for 6 years; it is followed by lower secondary, comprising grades seven to nine (AIC, 2018). Students must pass an examination in their final year to move on to upper secondary education or vocational education. Upper secondary education lasts 3 years and can either be general or vocational (i.e., practical, job-related training).

The Latvian education system faces many challenges, as highlighted in the introductory parts of this article. However, issues such as teacher shortages, an ageing workforce and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are not unique to Latvia; these challenges are common in many countries around the world. A recent Eurydice report confirmed that a majority of countries in Europe face teacher shortages; specifically, up to 35 countries were facing shortages with only three countries—Cyprus, the United Kingdom and Turkey—reporting an oversupply/no shortage (European Commission: European Education and Culture Executive Agency et al., 2021).

Data shows that populations around the world are ageing, living longer today than they have ever lived in history (Gu et al., 2021). This trend poses a tremendous challenge to the workforce and the overall economy in that there are simply too few young people to support different sectors of the economy, including education, in many developed countries. Japan, for example, has one of the oldest populations in the world (PRB, 2020). Other countries experiencing this challenge include Germany and Italy, which have huge elderly populations (Gu et al., 2021). In the U.S, although the problem is not as pronounced, it remains a major challenge. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted every nation’s economy, way of life, education, businesses, and workers in many fundamental ways. For example, many countries instituted lockdown measures; this meant that students were reliant on online learning, which exacerbated challenges such as inequalities in education with children from resource-deficient background being unable to learn because they lacked information technology infrastructure such as computers and high-speed internet (Darmody et al., 2021). Thus, although Latvia faces many challenges in education, these are part of a broader trend seen in other countries too.

Teacher shortage poses a serious threat to the quality of education offered to pupils in most schools in Latvia, and many have resorted to recruiting teachers without pedagogical education. Alternative teacher education programmes, such as FPA, are designed to attract people into the teaching profession who already have a bachelor’s degree and/or a professional qualification. By their very length, four-year degree programmes act as a barrier to entering the teaching profession for people who already have one degree (Humphrey et al., 2018). Therefore, the main goal of shorter, alternative certification programmes is to attract strong candidates with a bachelor’s or master’s degree into the teaching profession, thereby reducing the barriers to changing careers that might otherwise prevent them from starting the pedagogical work.

Alternative programmes are less costly, relatively shorter and usually more practice-oriented. These programmes include teaching practice, coursework in pedagogy and the subject to be taught, a professional development course and mentoring support. Alternative certification programmes are beneficial both for educational institutions that need to fill vacancies and for professionals interested in a meaningful career. The FPA programme provides schools with greater flexibility to recruit teachers to address the teacher shortage.

The programme teaches participants different teaching methods and tools, developmental psychology, as well as how to work with diverse learners (e.g., different cultures, languages, special needs) and how to motivate pupils to learn. The emphasis is on developing participants’ competence in planning and conducting lessons. Participants in alternative programmes develop their skills in working within a particular organisational culture, classroom management, how to prevent burnout, learner assessment and time management (Bowling and Ball, 2018).

Alternative teaching certification accelerates the entry into the teaching profession of those who already possess higher education. Such teachers usually have highly developed special skills, and research reveals that graduates of alternative teacher education programmes are able to teach pupils at the same level of quality as teachers who have completed four-year teacher education programmes (Casey, 2019). Furthermore, research has shown that individuals who began their learning through alternative certification programmes remain in school longer than teachers who graduate from traditional programmes (Bowling and Ball, 2018). Alternative certification programmes also increase teacher diversity. Overall, alternative certification programmes provide a potential solution to teacher shortage by maintaining a steady supply of new high-quality teachers.

Despite the advantages of alternative certification programmes, this approach does not always ensure a high-quality supply of teachers, because graduates from such programmes tend to lack pedagogical preparation, thus requiring further studies or professional development courses. Whereas traditional training programmes are based on an in-depth study of methodology and pedagogy in teacher education, most alternative programmes lack common standards that equip teachers with various critical skills, knowledge and competencies (Humphrey et al., 2018).

Such alternative programmes have been criticised for devoting little time to issues such as how to work with parents and families, how to assess effectively pupils’ work and progress, and how to promote literacy development. Critics argue that learning to teach requires more time, education and extensive experience than most alternative certification programmes provide (Bowling and Ball, 2018). Furthermore, graduates of alternative programmes tend to face difficulties in classroom management, learner assessment, time management and planning (Schonfeld and Feinman, 2012). Therefore, there is a perception in society that teachers who have not studied in traditional teacher education programmes lack professionalism. However, recent studies (e.g., Lucksnat et al., 2024) refute this criticism, showing no evidence of differences in teaching quality between alternatively and traditionally certified teachers. Regardless of certification type, novice teachers scored lower on classroom management compared to experienced teachers.

Around the world there are various alternative teacher certification programmes, of various lengths, that a prospective teacher may complete to be eligible to teach. Some programmes require prospective teachers to complete only a few weeks of professional preparation, whereas others require one or 2 years of study. For graduates of alternative teacher certification programmes to competently perform their professional duties, it is necessary to develop standards for effective professional development programmes that specify required coursework and tests, prior experience, mentoring and continuous professional development.

One solution to the teacher shortage in Latvia, as outlined in Cabinet of Ministers Regulations No. 569 (2018), is the introduction of FPA, a 72-academic-hour professional competence development programme. This programme is offered to individuals with relevant qualifications—such as general education teachers, vocational education teachers, internship supervisors, or those with higher education in a corresponding scientific field, a third-level professional qualification, or a craftsman qualification awarded by the Latvian Chamber of Crafts at the master level—who lack formal teaching qualifications. Those who complete the FPA programme become qualified to perform pedagogical activity (i.e., teach subjects related to their previous qualifications in schools, vocational education establishments and interest education). Participants are admitted to the programme based on the compatibility of their prior education. Only higher education institutions in Latvia that implement pedagogy study programmes have the right to develop and administer FPA. In Latvia, this programme is implemented by the University of Latvia, Riga Technical University’s Liepaja Academy, Rezekne Academy of Technologies, and Daugavpils University. Daugavpils University offers an extended 120-h programme.

Responding to discussions at various levels of society about the necessary support for teachers in the context of reducing vacancies, the authors of the study set out to evaluate the experience of the FPA professional development programme (2016–2023). The first groups of participants were recruited in 2007, and the first graduates have been working responsibly as teachers, educational organisers, heads of public and private educational institutions, heads of interest groups, teachers of vocational education schools, and in other capacities related to education. FPA instructors were professionals who taught within their respective fields, although the composition of the teaching staff changed according to the new requirements and lecturers’ abilities to participate in the programme implementation.

Students’ responses indicated that the most successful format for the FPA professional development programme was face-to-face classes held on Saturdays, spanning the entire day from morning to evening (eight academic hours). This format was implemented for a few years until demand grew so dramatically that the introduction of Friday classes also became necessary. The programme typically last up to 4 months, during which students attend nine Saturdays or Fridays, with the final day dedicated to presenting their coursework developed under the guidance of a consultant. The scheduled training programme consists of a cumulative 72 h, which allows participants adequate time for reflection, application of learning, and continuity in their professional development.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic brought significant changes: The programme has been conducted exclusively online since 2020. This shift revealed numerous advantages, including the opportunity for individuals from different parts of Latvia to participate. According to programme participants, online courses are more cost-effective, allow them to remain at home with their families, and provide opportunities to utilise various innovative educational approaches and tools. High-quality course output is possible working online (Kiris, 2023). Similar benefits are also highlighted by Ramirez et al. (2021), such as cost-effectiveness, improved engagement in learning activities, the practical application of innovative methods, and the potential for adapting educational approaches to diverse learner needs. The literature review findings emphasise the importance of flexibility and creativity in educational practices, which align closely with the objectives of this programme.

According to its description, ‘The programme is designed to meet the requirements of the Regulations on the Education and Professional Qualifications Required of Teachers and the Procedure for the Development of Professional Competence of Teachers’ [CM 569 (2018) and CM 706 (2020)], which state, in essence, that all teachers in educational institutions are required to have a pedagogical education. Persons with non-pedagogical higher education or secondary vocational education (from professional qualification level 3 upwards) are offered the opportunity to acquire the basics of pedagogical knowledge and skills during their programme of study, to strengthen a responsible attitude for proactive action in the field of education and to develop pedagogical competences. The aim of FPA is to promote the programme participants’ understanding of the current issues of the educational process and to facilitate the development of their pedagogical competence for work in an educational institution, offering strategies to solve the challenges of the 21st century. The programme provides the opportunity to learn about global and national educational problems, their causes and solutions, as well as to promote understanding of the latest approaches and theoretical knowledge in pedagogy, and, finally, to acquire the skills needed to integrate current issues of pedagogical science into pedagogical practice.

The topics covered in the FPA professional development programme are continuously updated—or even wholly revised—in response to current educational challenges, such as reform requirements (School 2030, competence approach), legislative changes (Data Protection Act), innovations in the work of educational institutions (introduction of innovative technologies), and the like. However, some topics are in high demanded and greatly valued by the programme participants, such as: ‘Modern teaching methods and techniques for ensuring an effective learning process,’ ‘Modern technologies for improving the learning process,’ ‘Media psychology: development and education of children and adolescents in the digital age,’ ‘Challenges of pedagogical ethics in postmodern society,’ ‘Diversity management in the educational process,’ ‘Individual and age-specific developmental characteristics and their impact on interpersonal interaction in the learning process,’ ‘The nature of education in today’s transformative society,’ ‘Conflicts and problem situations, their causes, resolution process and methods,’ ‘Managing emotions and stress’ and ‘Children and teachers’ duties, rights and their legal protection.’

The final project is developed under the guidance of a mentor and usually reflects the student’s practical contribution, validation of an innovation, or research into a new topic in their immediate field of pedagogical activity. Learners must complete a final project that demonstrates the knowledge and skills acquired during the programme and applies them in connection with the specifics of the learner’s field of activity. This includes providing a theoretical rationale, selecting appropriate implementation strategies and outlining expected outcomes. As part of the final project, programme participants compile a portfolio—a collection of methodological materials for teaching one topic—and develop detailed plans for two teaching lessons. If possible, these plans are implemented in practice. The programme’s final project allows participants to develop individual interests or projects; past examples have included creating new extracurricular programmes in pottery, testing innovative methods, or teaching the Latvian language to Ukrainians.

4 Evaluation of the fundamentals of pedagogical activity (FPA) programme

The aim of the study was to evaluate the experience of the FPA professional development programme (2016–2023). The study was conducted using both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, namely a survey and focus group discussion (FGD).

4.1 General description of the study

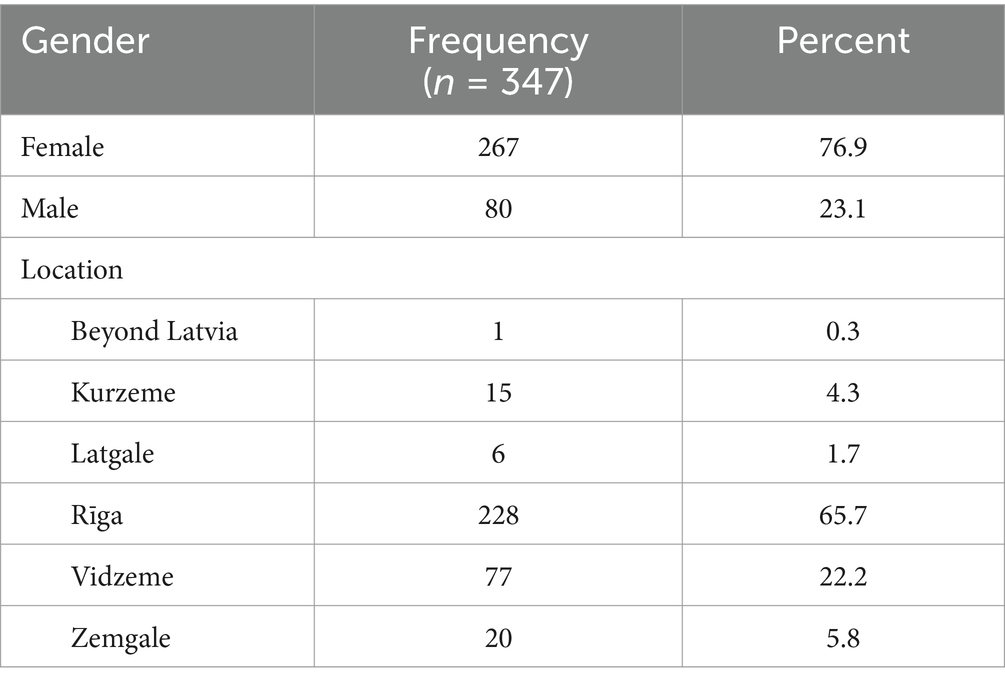

The quantitative part of the study—the survey—was conducted in 2023. It was administered online, with all graduates of the FPA programme being contacted and invited to take part in the survey. Three repeated invitations were sent to the graduates. The size of the master set was N = 1736; the size of the real sample was n = 347 respondents.

4.2 General description of respondents

Table 1 contains gender and location data on participants. In line with the general population (all graduates), the majority of respondents are female (76.9%); three quarters of the graduates are from Riga (65.7%). The data of the regional composition of respondents living outside Riga shows that Vidzeme region is the most represented region, with 22.2% of all respondents, followed by Zemgale (5.8%), Kurzeme (4.3%) and Latgale (1.7%).

Participants come from a wide range of sectors—more than 20 in total. Education is the most represented sector (73%), with less represented sectors including information technology, healthcare and medicine, public administration, library science, law and project management.

4.3 Evaluation of the FPA programme (survey data)

The cumulative programme evaluation consists of three groups of indicators (groups of evaluations) characterising the study programme: (1) the duration of the programme, (2) the evaluation of the knowledge and skills acquired during the programme, and (3) the use of different pedagogical methods in the study process.

The majority of respondents (79%) were satisfied with the programme duration of 72 academic hours (nine study days), some (19%) thought that the programme was too short and some (2%) thought that the programme was too long. No significant correlations were found when analysing the relationship between respondents’ opinion about the length of the programme and respondents’ previous teaching experience, age and gender.

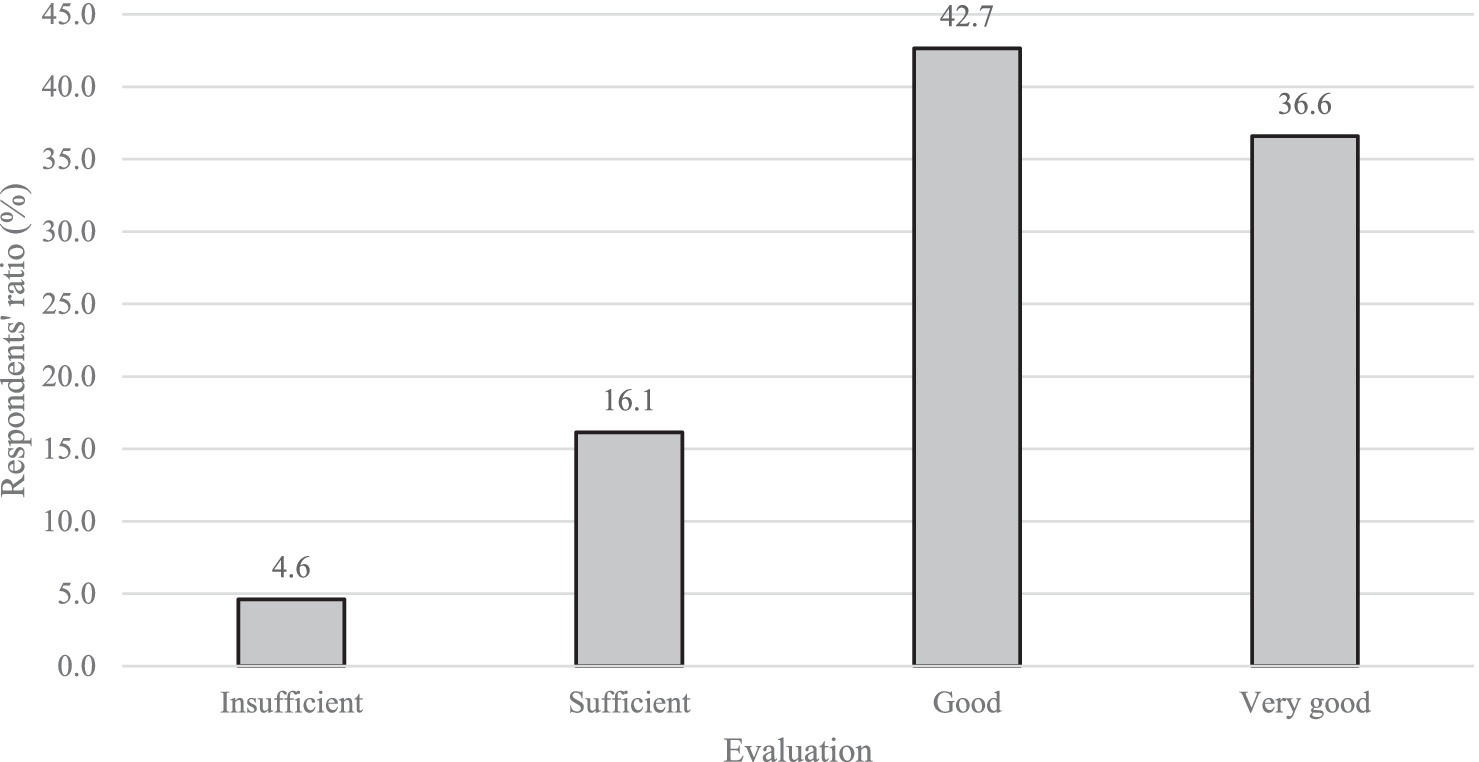

Respondents were asked to rate the usefulness of the knowledge and skills acquired in the programme for their future work. Overall, graduates were very positive about the usefulness of the knowledge they had acquired, with four fifths (80%) rating it as very good or good and a further 16% rating it as adequate. A very small minority (4%) rated the knowledge gained as insufficient.

No significant correlations were found when analysing the data on the reported usefulness of the acquired knowledge and skills by gender, age and previous teaching experience (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participants’ assessment of the usefulness of the knowledge and skills acquired in their future work (n = 347).

Participants were asked to answer questions concerning their motivation to acquire the programme: to obtain a certificate, desire to improve their knowledge and skills, interest in pedagogy, to meet the requirement from the head of the educational institution, or desire to gain knowledge to use in the education of their children (respondents could choose more than one answer). The most frequently mentioned motivations were the desire to obtain a certificate to be able to work as a teacher (70%), the desire to improve knowledge and skills (62%), interest in pedagogy (41%), and the requirement of the head of the educational institution (30.3%). Almost every fifth respondent (19%) noted that it is important to acquire pedagogical knowledge to be able to use it in the education of their children.

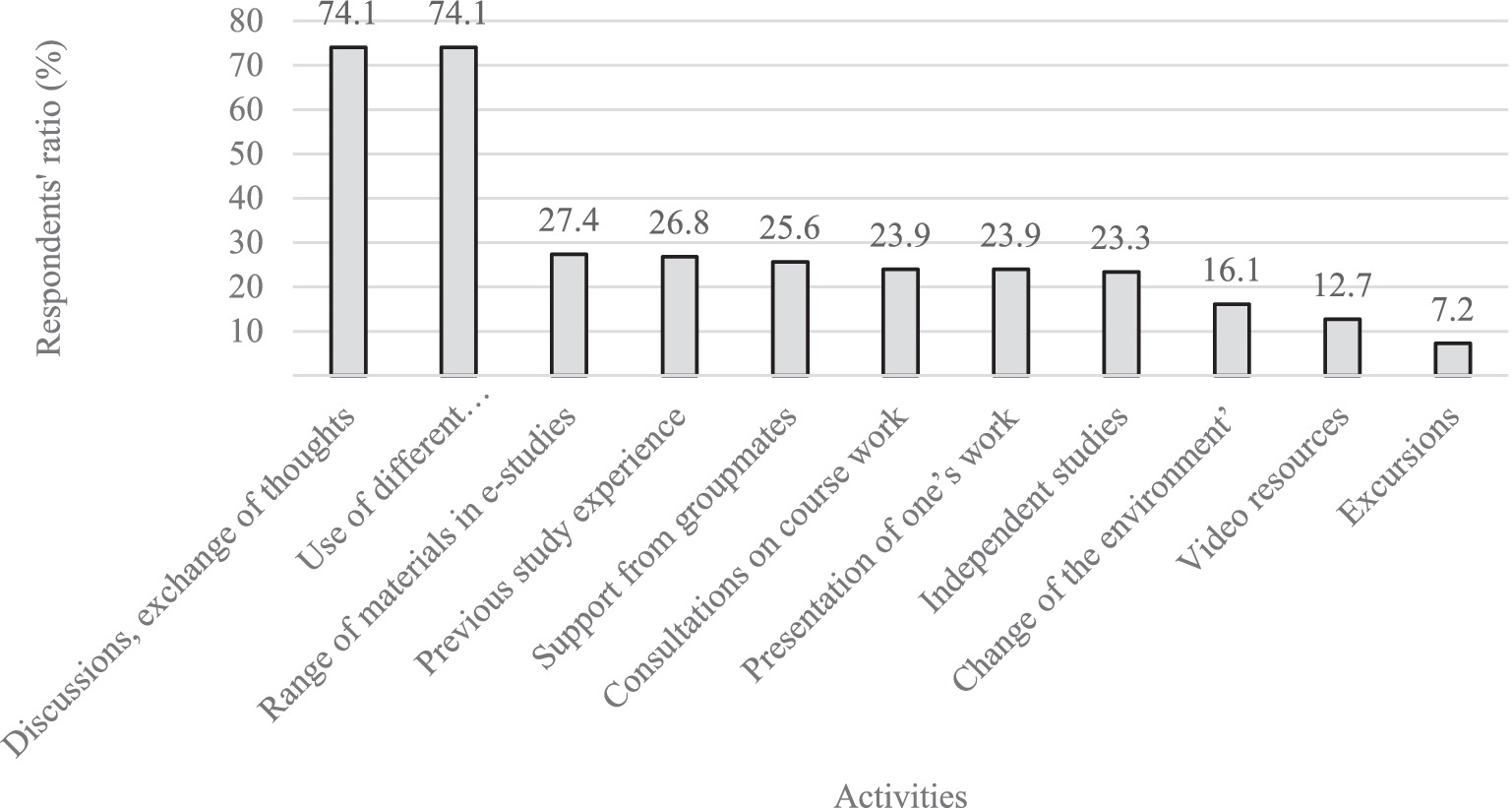

The next aspect of programme evaluation concerns the evaluation of the learning process. This block of questions enables the identification of the most valuable learning activities in the study process. Respondents were presented with a list of 11 activities and were allowed to choose multiple answers. Discussion and exchange of ideas (74.1%) and the use of different teaching/learning methods (74.1%) were the most frequently appreciated. Other activities were mentioned less frequently: 27.4% of students appreciated the range of materials available on E-learning, while one in four students (25.6%) appreciated the support of their group members. 23.9% of students found it important to have guidance during working on the coursework, the possibility to present their work and to be able to review other students’ work (23.9%). Independent study (23.3%) and a change of environment (16.1%) were also rated as fairly important. A small number of students highly valued opportunities for visual experience: the use of video resources (12.7%) and excursions (7.2%). Every fourth student also mentioned previous study experience as a factor that facilitated the learning process (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Programme participants’ rating of the most valuable activities of the study process (n = 347).

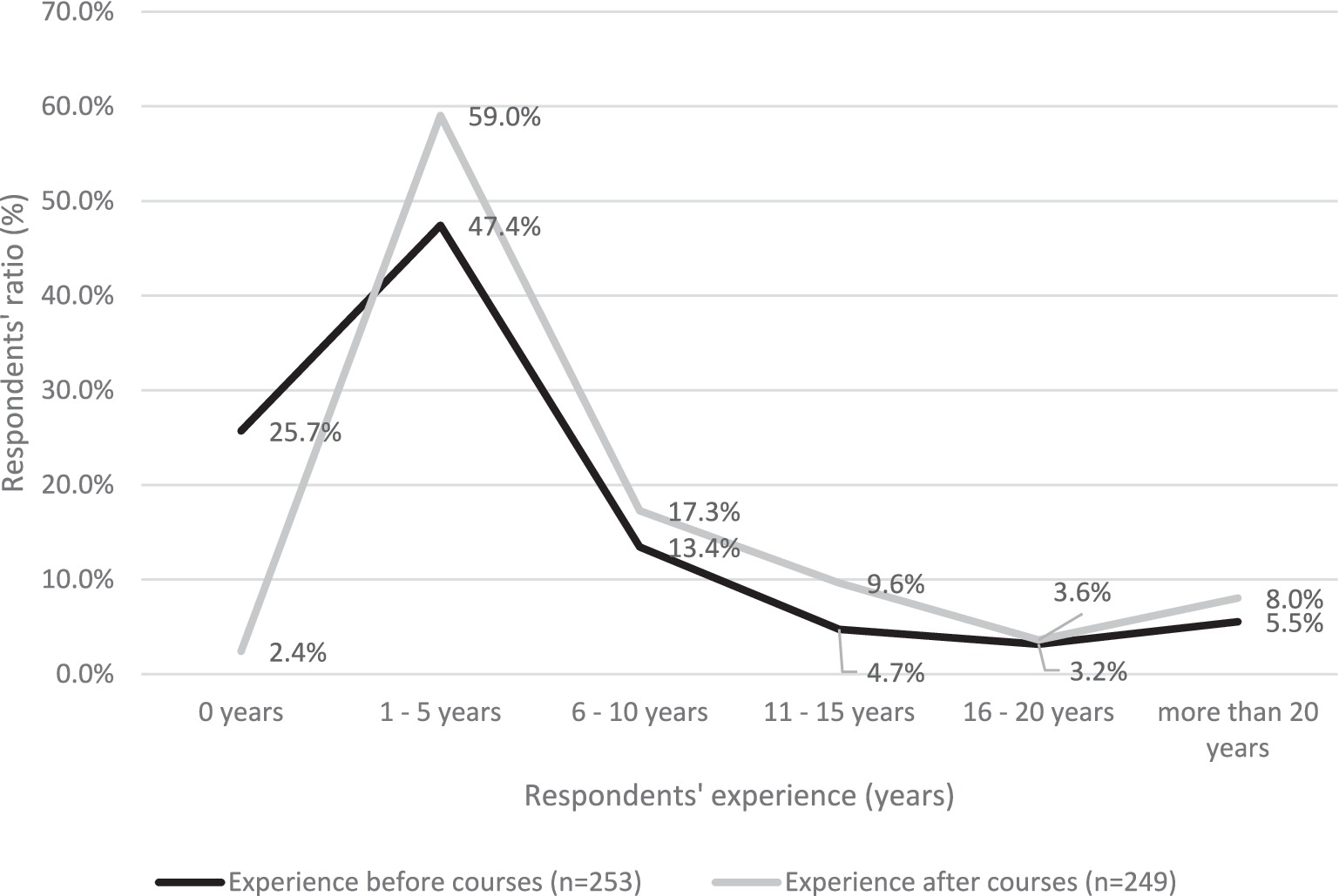

Figure 3 shows difference of respondents’ experience before and after the FPA programme. Data was gained only from participants continuing their career in the field of education (73.6% of all respondents). Data shows that 25.7% of respondents had no experience in education. After the programme, the number of respondents with no experience fell to 2.4%; those with 1–5 years of experience grew from 47.4 to 59.0%; those with 6–10 years grew from 13.4 to 17.3%; and those with 11–15 years grew from 4.7 to 9.6%. This growth of respondents’ experience in education shows the significant impact of the FPA programme.

5 Assessment of the FPA programme (FGD descriptive analysis)

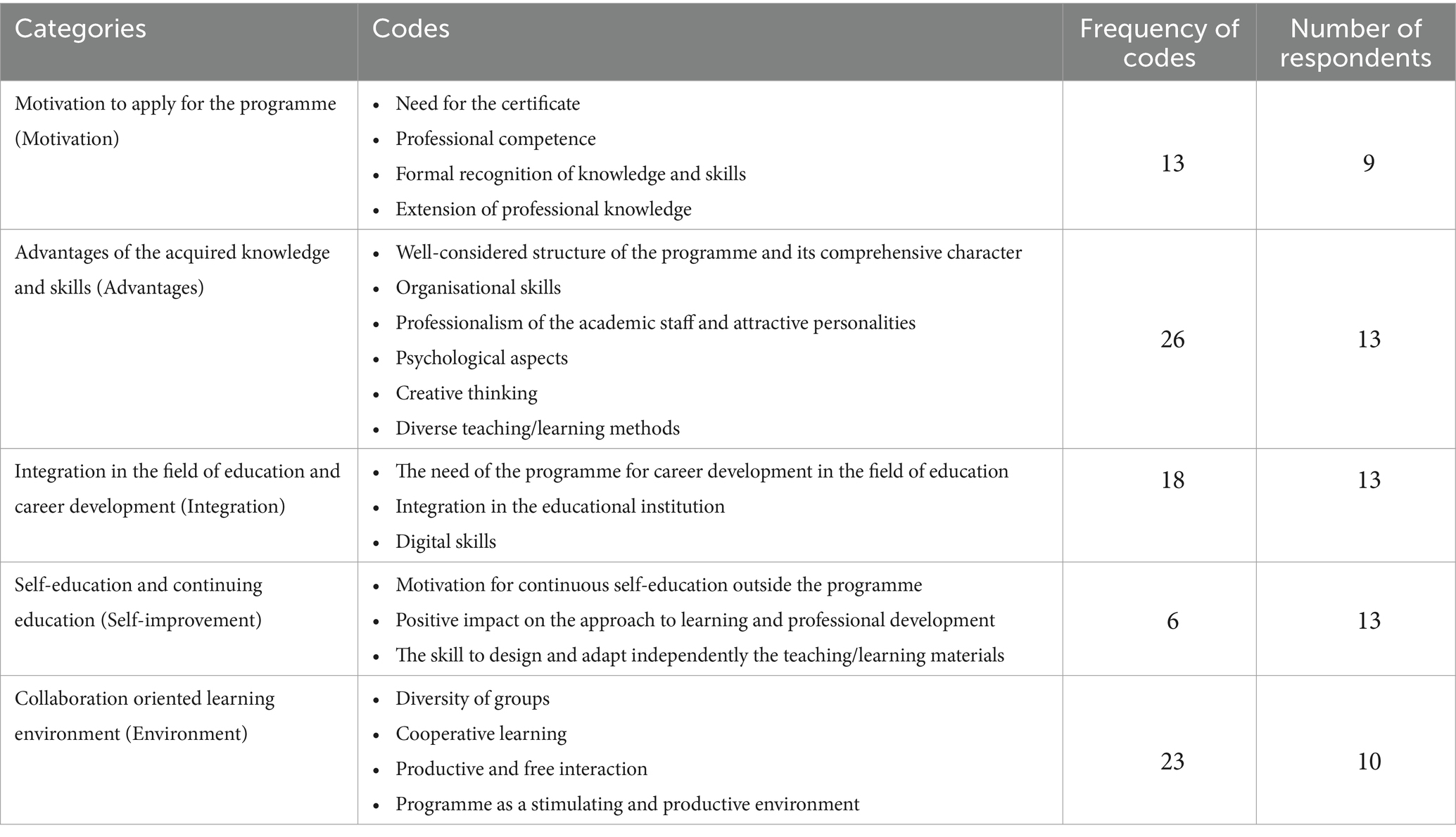

The qualitative part of the research, FGD, took place in January 2023 and was attended by 13 participants—all of them FPA graduates. The FGD participants were aged between 30 and 67 years, comprising nine women and four men who graduated from the FPA programme between 2011 and 2022. The data obtained are considered valid and provide a comprehensive picture of the programme evaluation, helping to identify key causal relationships. The authors used NVivo 14 to conduct a thematic analysis of the FGDs. The FGD analysis complements the data from the survey, helping to answer the research question.

After analysing the 13 FGD statements, the authors of this study initially individually created lists of codes and then jointly discussed these codes and their division in categories. After two rounds of coding, 20 codes were inductively identified and divided into five categories (see Table 2). These codes served as an analytical framework for exploring the experience of acquiring the FPA programme. The number of cumulative codes found for each category to analyse the participants’ experience is presented in Table 2.

The results of the FGD analysis complement the survey data with information on why students chose the FAP programme. Participants cited the need for a teaching certificate in order to work in education. Students had different reasons for needing a certificate: to run an interest group, to licence a private educational institution and legally organised the educational process and to work professionally, to improve their professional knowledge and skills, and to acquire new knowledge. Illustrative responses from the participants themselves are provided below. (‘F’ indicates a female respondent; ‘M’ indicates a male respondent).

Running extra-curricular interest education activities: ‘This programme gives me the opportunity to obtain a teaching qualification in a short time (6 months) in addition to my basic higher education, which allows me to run an interest group activity in the school, both legally and substantively.’

Licencing a private educational institution and working in a self-founded school: ‘Becoming a licensed interest education institution was the only way to differentiate from the unprofessional and even sometimes criminal modelling environment, to professionalise and raise the prestige of showing costumes’ (M); ‘to legalise my activity as a pedagogic and educational institution because of the negative actions of his competitors.’

The administration’s request: ‘The administration asks me as a psychologist to get a teaching qualification’ (F).

Interest in pedagogy, the desire to acquire new knowledge: ‘I like learning so much that I engage in learning once every six months’ (F).

The FGD provided an opportunity to assess the main benefits of the programme, highlighting the skills and competences that participants considered important after their graduation. Each FGD participant mentioned at least two to three of the most important skills and knowledge they had acquired during the programme. All FGD responses can be categorised into several groups:

1. A high all-round evaluation of the programme as a whole, recognising the importance of everything students have gained from their studies. Such responses include a high evaluation of the programme (‘very cleverly put together’) and an explanation of what the graduate has found most important about the programme (‘everything that happens in the learning process, because it does important things to us, trains us for work with different adults, makes us cooperate, speaks about conflicts, speaking skills, ageing’). The programme is described with an emphasis on the ‘systematic, good structure to the whole programme.’

2. Some FGD participants gave high marks to the organisation of the learning process during the programme, appreciating ‘teaching methodology’ and ‘teaching/learning methods, […], prediction of situations.’ This category also encompasses aspects such as analytical work when writing the coursework and giving feedback to others: ‘analytical work in writing the coursework and reviewing others’ work.’

3. Very high assessment of the teaching team and various aspects of the work of the lecturers. Responses in this category include high marks for ‘the teaching team’ to ‘the personality of the lecturers – it was a pleasure to meet many interesting, professional people and to gain new knowledge in my professional field.’ Programme participants have mentioned that the highly professional lecturers changed their perception of pedagogy and educators: ‘the charismatic teachers successfully “smashed” all the bad stereotypes about educators.’ The programme of some outstanding lecturers were mentioned: ‘the lectures of Z. Rubene and I. Margeviča-Grinberga were valuable.’ Several graduates appreciated the knowledge they had gained in legislation and legal matters.

4. Knowledge of psychology: various aspects of psychology, including more general comments on ‘knowledge of psychology’ as well as knowledge of developmental psychology, which is highly valued because it helps learners understand both adolescent psychology as well as ‘how to perceive pupils […], generational differences from Zanda Rubene’s lectures; understanding pupils’ psychology, speaking to pupils in a language they understand, methods of teacher’s work.’ Several graduates emphasised the acquired ‘competences in analysing pupils’ behaviour.’

5. Various aspects of programme are highlighted: ‘I got ideas about creative thinking and interest education’ and ‘I got academic confirmation of my intuitive hunches.’

6. Graduates’ conclusions about the organisation of the learning process in their teaching work: ‘firstly, that lessons always need a plan B, but also a plan C. I feel this perfectly well now in practice.’ This would also include teachers’ professional skills, such as ‘speaking skills.’

7. A stimulating working environment and the role of the group were mentioned as important benefits of the study process, emphasising the ‘diversity of the group,’ assessing their former study group as ‘an environment where I can fit in,’ and the importance of cooperation in the study process, ranging from ‘learning to cooperate’ to a categorical ‘makes you cooperate.’ Graduates appreciated the diverse personalities of the group. In general, the study process is described as an environment where ‘you can fit into a group, learn, and work productively.’

The FGD provided an opportunity to collect and analyse information on whether and how the participants joined the education field during the programme and whether and how the learning promoted students’ career development. All FGD participants confirmed that the programme had helped them to integrate into education and fostered their career development. Their assessment ranges from laconic assessments of ‘needed it’ and ‘it was a prerequisite’ for a job/career in education and pedagogy, to an extended description of integration into an educational setting working with pupils who have good digital skills: ‘integration into the field and learning about digital technologies and cooperation with pupils. […] The challenge was to integrate into a teaching/learning process where pupils are used to using new technology tools in lessons.’

All FGD participants mentioned the desire to continue their own learning, which can be seen as evidence of the positive spin-off effects of the programme—a desire not to stick with what they have learned, but rather to approach the learning process creatively and continue learning through self-directed learning. One of the participants discussed her experience in the workplace: ‘For five years my workplace has been a private school where I know exactly what I have to teach, but how I do it is my responsibility. Having a look into textbooks, I make practically all the material myself. I will say that every lesson is a challenge.’

6 Discussion

In many countries, programmes similar to FPA have attracted significant attention over recent years. These initiatives commonly aim to address teacher shortage. The United States, for example, implements alternative certification programmes (ACPs) to address this challenge. Approximately 18% of public school teachers in the U.S. enter the profession through these programmes (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). Many countries in Europe have also utilised ACPs (European Commission, 2023). These programmes are often adapted to a country’s specific pedagogical needs and usually aim to address teacher shortages.

Research shows that programme similar to the FPA deliver valuable advantages. According to the Dori et al. (2023), ACPs are an effective alternative for sourcing capable teachers within a short period. However, studies have showed that teachers who enter the profession via this route often face a multitude of pedagogical challenges, especially in their first years as educators (Keese et al., 2022; Margeviča-Grinberga and Šūmane, 2024). However, continued skill development has been shown to help address this challenge. The FPA addresses many of the criticisms commonly levelled at alternative certification programmes. Although available research shows that many similar programmes have limited preparation in pedagogy and classroom management (Jung et al., 2022; Redding, 2022), analysis shows that the FPA programme teaches participants different teaching methods and tools, developmental psychology, as well as how to work with diverse learners (different cultures, languages, special needs) and motivate pupils to learn. These are essentially classroom management approaches that help teachers deal with a myriad of class-related challenges.

The findings showed that acquired knowledge and skills (Advantages) and collaboration oriented learning environment (Environment) had the highest frequency of all codes: 26 and 23 appearances, respectively. This suggests that these two aspects were particularly valued by participants due to the tangible benefits they impart, such as gaining new skills, professional growth and a supportive environment. The above results could also indicate that participants found these aspects to be directly impactful on their professional development, which resonates with the programme’s broader educational goals, such as equipping students with skills that enhance employability and career growth, while also fostering a productive and supportive learning environment. On the other hand, the results showed that Self-education and continuing education (Self-improvement) had a low frequency (6). This may suggest that participants either did not perceive self-education and continuing education as being an immediate or central component in their motivations for enrolling in the programme or that the programme did not explicitly emphasise or facilitate self-driven learning initiatives. The above findings could also imply that respondents were already familiar with self-improvement tools and were therefore focused on other areas. These results have a number of broader policy implications.

Firstly, the high valuation of acquired skills and knowledge underscore the criticality of designing programmes that emphasise improving learners’ skill competency and knowledge. Thus, national and regional education policies should prioritise designing programmes that explicitly link education with skill acquisition and employability in pedagogy. Secondly, collaborative environments were ranked highly. Thus, national and regional policies should champion programmes that encourage the development of inclusive and interactive learning environments. Such settings would help fashion national as well as regional programmes that foster deeper engagement and learning outcomes. Lastly, the results indicated low emphasis on self-improvement. Thus, national and regional policies should strive to develop programmes that emphasise on lifelong learning and continuous professional development. Teachers should be encouraged to pursue competency in pedagogy skills not just for immediate career advancement. Education ought to impart sustained long-term professional growth.

Although most respondents found the 72-h programme sufficient for their needs, 19% of participants were of the opinion that the programme duration was too short. This indicates that the programme likely had some gaps, limiting learners’ ability to fully absorb the content and achieve professional competency. The above is a serious weakness and raises questions about the programme’s ability to cater to diverse learning needs. Indeed, studies on professional training programmes have showed that longer or modular formats commonly lead to thorough skill acquisition, especially for complex competencies compared to shorter programmes (Yan et al., 2024; Bowling and Ball, 2018).

Thus, the 72-h timeframe may need to be re-evaluated to ensure its effectiveness across different learner profiles. It may, for example, be beneficial to explore modular or extended formats that allow for greater flexibility in terms of programmes duration. Such an approach would provide additional training options, thereby ensuring that all participants, regardless of their pace or learning style, achieve the desired skill competency. In summary, although our findings showed that programme met the needs of most participants, a significant minority felt that additional time was required for comprehensive skill development. In effect, providing this group with an extended or modular training options may improve the programme’s effectiveness as this would ensure that all participants acquire pertinent skills for their professional roles.

7 Conclusion about the importance of the FPA programme

1. The study identifies the main factors in choosing a study programme. The first factor is related to the acquisition of pedagogical qualification (certificate) for the right to carry out pedagogical activity in accordance with the Cabinet of Ministers Regulation No. 569; the second factor is the desire to improve one’s knowledge, skills and competences in education. The third important factor is that the programme’s 72-h duration was well-received by most learners.

2. Evaluating the learning process is crucial for successfully completing the FPA programme. Interactive methods—such as group work, discussions, idea exchanges, and the use of diverse teaching approaches—received the highest approval, with 74% of participants rating them favourably.

3. Graduates of the FPA programme highly appreciated its excellent structure, comprehensive subject matter, well-organised studies, the lecturers’ professionalism, and their ability to effectively collaborate with other professionals.

4. The acquisition of the FPA programme ‘positively affects teachers’ motivation to work in the field of education and to continue their professional development.

5. Because the FPA programme helps resolve the current problem of teacher shortages, it should continue to be implemented and its content developed further.

6. Having evaluated the experience of the FPA professional competence development programme (2016–2023), it is recommended to continue using innovative pedagogical methods and interactive teaching/learning approaches to promote the acquisition of teacher’s professional competences.

7. The research question of this study is answered in the affirmative: The FPA programme increases the number of teachers with experience in education, and a high percentage of programme graduates either begin or continue working in the education sector.

8 Recommendations

Following the assessment of the FPA programme, numerous recommendations can be proposed to improve its lasting outcomes and guide future research.

1. A topic that warrants further investigation is the programme’s actual effectiveness in addressing teacher shortages.

2. Annual tracking should be conducted to determine the percentage of teaching vacancies filled by programme participants. This information would provide insight into the programme’s direct impact on filling the teacher shortage in Latvia.

3. Key emphasis must be placed on programme graduates’ retention and career longevity. Future research should conduct annual follow-up evaluations to track the duration of graduates’ engagement in teaching positions.

Considering the popularity of the online format, long-term studies could investigate the enduring effects of hybrid or entirely online cycles of the programme on graduate preparedness and instructional efficacy. Furthermore, studies could evaluate the programme’s scalability. The programme’s success in Latvia may inspire and guide the establishment of such programmes in other countries facing teacher shortages.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Kaspars Kiris, University of Latvia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

IM-G: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ĒL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. RĀ: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Skolu vakanču karte. Pieejama: https://esiskolotajs.lu.lv/vakances/ [School vacancy map].

2. ^Vakanču saraksts. Rīgas domes Izglītības, kultūras un sporta departaments. Pieejams: https://izglitiba.riga.lv/lv/izglitiba/vakances/skolu-vakances [Vacancy list. Education, Culture and Sports Department, Riga City Council].

References

AIC (2018). Education in Latvia. Sākums - Akadēmiskās informācijas centrs. Available online at: https://aic.lv/en/izglitiba-latvija#:~:text=The%20Latvian%20education%20system%20consists,EHEA%20(2018):%20Latvian%20English

Bowling, A. M., and Ball, A. L. (2018). Alternative certification: a solution or an alternative problem? J. Agric. Educ. 59, 109–122. doi: 10.5032/jae.2018.02109

Casey, T. S. (2019). The effectiveness of alternative routes to teacher certification ’. Ph.D thesis: Northeastern University. doi: 10.17760/D20319840

Darmody, M., Smyth, E., and Russell, H. (2021). Impacts of the COVID-19 control measures on widening educational inequalities. Young 29, 366–380. doi: 10.1177/11033088211027412

Department for Education, UK Government (2018). Cooper Gibson research: factors affecting teacher retention: qualitative investigation research report. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/686947/Factors_affecting_teacher_retention_-_qualitative_investigation.pdf

Dori, Y. J., Goldman, D., Shwartz, G., Lavie-Alon, N., Sarid, A., and Tal, T. (2023). Assessing and comparing alternative certification programs: the teacher-classroom-community model. Front. Educ. 8:1006009. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1006009

European Commission (2023). Alternative pathways to becoming a teacher. European School Education Platform | European School Education Platform. Available online at: https://school-education.ec.europa.eu/en/discover/news/alternative-pathways-becoming-teacher#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Eurydice%20report,%2C%20distance%2C%20or%20blended%20learning.

European Commission: European Education and Culture Executive AgencyBirch, P., Motiejūnaitė-Schulmeister, A., and De Coster, I., Davydovskaia, O., and Vasiliou, N. (2021). Teachers in Europe: careers, development and well-being. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online at: https://op.europa.eu/publication-detail/-/publication/78fbf243-974f-11eb-b85c-01aa75ed71a1

Geske, A. (2019). Starptautiskā Mācību Vides Pētījuma OECD TALIS 2018 Rezultāti: Skolotāji un Skolu Direktori – Kvalifikācija, Nodarbinātība un Slodze, Darbā Ievadīšana un Profesionālā Pilnveide’. [Results of TALIS 2018 International Learning Environment Survey: teachers and school principals – qualifications, employment and workload, induction and professional development]. Available online at: https://www.ipi.lu.lv/fileadmin/user_upload/lu_portal/projekti/ipi/Publikacijas/TALIS2018ZinojumsB.pdf

Gu, D., Andreev, K., and Dupre, M. E. (2021). Major trends in population growth around the world. China CDC Weekly 3, 604–613. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.160

Humphrey, D. C., Wechsler, M. E., and Hough, H. J. (2018). Characteristics of effective alternative teacher certification programs. Teach. Coll. Rec. 110, 1–63. doi: 10.1177/016146810811000103

Jung, J., Case, L., Logan, S. W., and Yun, J. (2022). Physical educators’ qualifications and instructional practices toward students with disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 39, 230–246. doi: 10.1123/apaq.2021-0117

Keese, J., Waxman, H., and Kelly, L. J. (2022). Ready and able? Perceptions of confidence and teaching support for first-year alternatively certified teachers. Teach. Educ. 57, 280–303. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2021.2003496

Kiris, K. (2023). “Distant hands-on approach in ICT teaching for adults” in Human, technologies and quality of education. University of Latvia, 480–489.

Laganovskis, G. (2023). Pedagogu trūkums – steidzami risināma problēma. [The lack of teachers is a problem that needs to be solved urgently]. Available online at: https://lvportals.lv/norises/354492-pedagogu-trukums-steidzami-risinama-problema-2023

LIZDA (2022). LIZDA aptaujas “Atbalsts jaunajiem pedagogiem” rezultāti. [Results of the LIZDA survey ‘support for young educators’.] Available online at: https://www.lizda.lv/current_events/lizda-aptaujas-atbalsts-jaunajiem-pedagogiem-rezultati/

Lucksnat, C., Richter, E., Henschel, S., Hoffmann, L., Schipolowski, S., and Richter, D. (2024). Comparing the teaching quality of alternatively certified teachers and traditionally certified teachers: findings from a large-scale study. Educ. Asse Eval. Acc. 36, 75–106. doi: 10.1007/s11092-023-09426-1

Margeviča-Grinberga, I., and Šūmane, I. (2024). Prospective teachers’ perspectives on pedagogical challenges experienced during work-based learning. Soc. Integ. Educ. Proc. Int. Sci. Conf. 1, 194–207. doi: 10.17770/sie2024vol1.7796

McKenna, B (2018). U.S. teacher shortages—causes and impacts. Learning Policy Institute. Available online at: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/body/Teacher_Shortages_Causes_Impacts_2018_MEMO.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (2022). Characteristics of public school teachers who completed alternative route to certification programs. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/tlc/alternative-route-certification?utm_source=chatgpt.com#suggested-citation

PRB (2020). Countries with the oldest population in the world. Available online at: https://www.prb.org/resources/countries-with-the-oldest-populations-in-the-world/

Ramirez, S. II., Teten, S., Mamo, M., Speth, C., Kettler, T., and Sindelar, M. (2021). Student perceptions and performance in a traditional, flipped classroom, and online introductory soil science course. J. Geosci. Educ. 70, 130–141. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2021.1965419

Redding, C. (2022). Changing the composition of beginning teachers: the role of state alternative certification policies. Educ. Policy 36, 1791–1820. doi: 10.1177/08959048211015612

Schonfeld, I. S., and Feinman, S. J. (2012). Difficulties of alternatively certified teachers. Educ. Urban Soc. 44, 215–246. doi: 10.1177/0013124510392570

State Education Information System Latvia (2024). Number of teachers in general education day schools. Available online at: https://www.viis.gov.lv/dati/pedagogu-skaits-visparizglitojosajas-dienas-skolas

UNESCO (2022). World teachers’ day: UNESCO sounds the alarm on the global teacher shortage crisis. Available online at: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/world-teachers-day-unesco-sounds-alarm-global-teacher-shortage-crisis

Keywords: teacher education, alternative teacher education programmes, foundations of pedagogical activity, further education, teacher shortage

Citation: Margeviča-Grinberga I, Kiris K, Lanka Ē and Ābele R (2025) Evaluation of the fundamentals of pedagogical activity professional development programme for teachers (2016–2023). Front. Educ. 10:1523826. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1523826

Edited by:

Natalia Pasternak Taschner, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Karin Joann Opacich, University of Illinois Chicago, United StatesJoseline Santos, Bulacan State University, Philippines

Camilo Lellis-Santos, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Margeviča-Grinberga, Kiris, Lanka and Ābele. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ieva Margeviča-Grinberga, aWV2YS5tYXJnZXZpY2FAbHUubHY=

†ORCID: Ieva Margeviča-Grinberga, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1809-2439

Kaspars Kiris, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5642-5900

Ērika Lanka, https://orcid.org/0009-0004-4730-8712

Rita Ābele, https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3629-9435

Ieva Margeviča-Grinberga

Ieva Margeviča-Grinberga Kaspars Kiris

Kaspars Kiris Ērika Lanka

Ērika Lanka Rita Ābele†

Rita Ābele†