- 1Faculty of Public Administration, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya'an, China

- 2School of Management, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

Employment is the biggest project of people’s livelihood. The high-quality employment of postgraduates is of practical significance to the supply of high-level talents and economic development. There is an urgent need for higher education to explore the critical path to improve the employment quality of postgraduates more effectively. In this study, 778 graduate students and hierarchical regression analysis were used to investigate the impact of human capital and social capital of graduate students on subjective and objective employment quality. The results show that human capital positively influences objective employment quality, and social capital positively influences subjective employment quality. Employability mediates the relationship between human capital and objective employment quality. It mediates between social capital and subjective employment quality. Future career clarity positively moderated the relationship between human capital and graduate student employability. Employment policy support negatively moderated the relationship between graduate student employability and subjective and objective job quality. This study reveals the mediating and boundary effects of graduate student “Capital” on employment quality and provides some references for graduate student training and employment.

Introduction

Employment is the greatest livelihood. Grasping employment is an essential task in safeguarding and improving people’s livelihoods. The employment of young people, such as graduates of higher education, has a bearing on the well-being of families, as well as on the long-term development of the country and the harmony and stability of society. As an integral part of higher education in China, postgraduate education is a meaningful way to cultivate high-level talents and robust support for economic and social progress. According to “Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China 2020–2024” released by the National Bureau of Statistics in 2024, the scale of graduate education continues to expand, the number of graduates from 2020 to 2024 will be 728,600, 773,000, 862,000, 1,015,000, and 1,084,000. As a large number of postgraduates enter the labor market, the employment market has gradually changed from “seller’s market” to “buyer’s market,” and employment problems such as person-job mismatch have become increasingly prominent, Chinese market labor supply and demand relation are further unbalancing. It is essential to analyze the status of graduate student employment quality in this context and to explore the factors that influence it.

Employment quality is a comprehensive concept reflecting the degree of merits and demerits of the working conditions of workers in social work (Ding and Liu, 2022), including wage income, welfare benefits, personal development prospects, and job-matching degrees. International scholars have proposed that employment quality includes the multi-dimensional quality of work and life (Nadler and Lawler, 1983), decent work (ILO, 1999), and quality of work (Schroeder, 2007). In addition, domestic scholars evaluate employment quality mainly from fundamental survival indicators such as salary, work region and level, unit nature, employment stability, and future career development indicators (Chen, 2015; Liu M. et al., 2018; Yang and Wang, 2020). The research on influencing factors of employment quality involves macroeconomic situations, employers, universities, families, and micro individuals (Li et al., 2022). Among them, family and individual “capital” play an essential role in the employment process of graduate students, mainly including human and social capital. According to the resource conservation theory (Hobfoll, 1989), human and social capital can be regarded as resources owned by individuals The human capital theory believes that education and training can improve work efficiency. Education level, major type, competition certificate, work skills, internship experience, etc. all belong to human capital, and the improvement of graduate employment quality mainly depends on human capital accumulation (Li et al., 2022). Social capital, on the other hand, relates to individuals’ resources and support in social networks and organizations (Bourdieu, 1997). Social capital can provide more employment resources and support for graduate students, reduce the cost of information search, and improve job matching and employment quality. Thus, human and social capital significantly impact the competitiveness of individuals in the job market.

Does capital further affect the quality of employment through other pathways? At present, most scholars pay attention to the types and influences of capital in the employment of graduate students but seldom explore the internal mechanism of capital on employment quality. According to the resource conservation theory (Hobfoll, 1989), employability is an individual’s ability to conserve resources in the labor market. People will try to preserve and protect the resources they possess, including human and social capital, to avoid losing resources. Individuals with sufficient precious resources are more capable of acquiring resources, and those acquired resources will generate a more significant increment of resources. Therefore, by enhancing the accumulation of human and social capital, individuals can increase their employability, thus better-retaining job opportunities and improving the quality of employment. Previous studies have shown that human capital and social capital are essential factors affecting employment (Yan and Dan, 2015). It enables graduate students to actively cope with changes in the external working environment and tasks to gain recognition in the labor market. Therefore, human capital and social capital have a positive impact on employability.

Strauss et al. (2012) proposed that future job clarity refers to the degree to which an individual is straightforward and easy to imagine a future job. In the process of job hunting, straightforward and easy-to-imagine future jobs can provide more targeted guidance and behavioral drive for future-oriented behaviors to strengthen the influence of human and social capital on the employability of graduate students (Locke and Latham, 2002). An employment policy is a policy document and measure used by the state and government to increase the demand for the labor force, promote employment, and relieve employment pressure (Rhodes, 2015). Policy support can effectively alleviate the contradiction between the supply and demand of college graduates, affect the behavior and ability of job seekers, improve the employment environment, and provide job opportunities for job seekers (Yang et al., 2022). Employment policy support can also provide resources and support to individuals to help them better preserve and protect their resources and thus improve the quality of their employment (Piasna et al., 2019). Therefore, employment policy support can strengthen the influence of employability on employment quality.

There are some limitations in the previous research samples, most of which focus on the employment status of individual majors or colleges, and there are few national sample surveys. Secondly, there is a debate about the impact of human and social capital on employment; which is more important? Do they have the same impact on the quality of employment? Meanwhile, the specific mechanism of human and social capital on employment quality needs to be addressed, and more attention needs to be paid to the individual initiative of postgraduates. Given this, this paper takes postgraduate students as the survey object. It constructs the path mechanism of “human capital and social capital – employability – subjective and objective employment quality” based on the theory of resource preservation. It tries to analyze the differences in the influence of human and social capital on graduate students’ employment quality and simultaneously explores their specific mechanisms. Then, by demonstrating the moderating role of future career clarity and employment policy support, we search for the influencing factors of employment quality from different perspectives of graduate students and the external environment. This study has the following academic contributions. Firstly, it enriches the research on graduate students’ employment. It analyzes and compares the different influences of human and social capital on employment quality to better understand the complexity and dynamics of graduate students’ employment quality. Second, it opens the “black box” between human capital, social capital, and employment quality and expands the research on employability in employment quality. It strengthens the focus on the individual initiative of graduate students in the job search process and provides new ideas for future research. Finally, it helps researchers better understand the relationship between employment and future career clarity and employment policy support. It also provides relevant policy recommendations to enhance the employment quality of graduate students. In addition, the theory of resource preservation explains the relationship between the various variables involved in this model, emphasizing the importance of individuals’ efforts to preserve and protect their resources in employment and career development. Given this, this paper takes graduate students as the survey object, constructs the path mechanism of “human capital and social capital – employability – subjective and objective employment quality,” and tries to demonstrate the moderating effect of future career clarity and employment policy support. This study is not only beneficial to enrich the employment-related research of postgraduates and strengthen the focus on the individual initiative of postgraduates in the process of job hunting but also provides a new perspective of the research on the employment quality mechanism and boundary of postgraduates and provides theoretical support for the working practice of higher education from different perspectives.

Literature reviews and hypothesis

The relationship between postgraduate human capital and employment quality

At present, the evaluation of the employment quality of college graduates mainly includes subjective and objective indicators. Subjective employment quality refers to graduates’ satisfaction with future career development space, job matching degree, salary, welfare, workplace and promotion opportunities, etc. (Li et al., 2005). Objective employment quality refers to the quality of the job obtained by the employee (Li et al., 2005), which reflects the current reality of employment quality (Wang, 2020), mainly including salary level, work location, the number of offers received in the employment process, corporate awareness, etc. (Cheng and Xu, 2016; Wang, 2018). The study also divides the employment quality of graduate students into subjective employment quality and objective employment quality.

In the early 1960s, the human capital theory created by Schultz (1961) believed that education is the main form of human capital investment. Human capital is formed by people’s expenditure on health care, education, training, and employment migration. The workers can generate permanent income, mainly manifested in the knowledge, skills, labor proficiency, and health status of the worker over some time (Tronti, 2019). For graduates, demographic variables, grade rankings, scholarships, English language skills, vocational qualifications, work experience, etc., can all be included in the human capital category (Benati and Fischer, 2020).

Scholars have widely discussed the research on human capital and employment quality. Human capital is generally believed to be an essential factor affecting employment quality. Human capital has a strong predictive effect on employment quality (Liu Y. et al., 2018; Yue and Tian, 2016). The primary sources of human capital are the knowledge and skills acquired in higher education, the working experience in the university organization and internships obtained in extracurricular practice, among which education brings a larger share of human capital (Li and Zhang, 2020). First of all, higher education can improve people’s productivity. People with better educational experiences are more likely to get a job that they are satisfied with and envied by others (Szromek and Wolniak, 2020). Workers with higher human capital tend to obtain higher employment quality in the job market, so high human capital can promote the quality of employment. Secondly, employers tend to consider that high human capital equals strong learning ability and training potential, and applicants’ competitiveness can be judged by the reputation and level of the universities they graduated from, which makes it easier for college students with high levels to take advantage in the job market (Wang, 2013). The level of human capital is an essential internal factor that affects the career development of individuals (Baldi and Trigeorgis, 2020). In addition, the experience and skills of graduates through participating in various competitions, social surveys, and internships in enterprises also belong to human capital. The more this kind of human capital is accumulated, the more employers will be inclined to hire, and the individuals are more capable of improving the quality of employment in the labor market. In summary, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 1A: Postgraduate students’ human capital positively affects subjective employment quality.

Hypothesis 1B: Postgraduate students’ human capital positively influences objective employment quality.

The relationship between postgraduates’ social capital and employment quality

Bourdieu (1980) was the first to put forward the concept of social capital, which is regarded as a tool to obtain privileges and maintain an individual’s privileged position in the system. The study combined with Wang’s (2013) and Wang’s (2018) research considers that college students’ social capital is the social relations that can be mastered by individual students and may be helpful to them. It is manifested as social structure resources, which mainly involve school background and personal and family social relationship networks.

Another critical factor affecting the quality of employment is social capital. Lieberman (1956) found that the social and family conditions of adolescents have a decisive influence on their careers (Chen, 2003). The social support generated by the intervention of social capital in the process of job hunting will affect college students’ career choice decisions and actions, and ultimately change the quality of employment (Luo and Wang, 2020). Social capital can help graduate students in their employment mainly from three aspects. First of all, it helps to collect and screen employment information. Individuals with higher social capital identify and obtain more or more explicit job information through different channels, enabling individuals to gain more stable job advantages (Xu, 2002), thus transforming the job market of graduate students into a “buyer’s market.” In worsening labor market information asymmetry, social capital plays an increasingly prominent role in the increasingly asymmetric labor market. If graduate students can get more employment information from social networks such as family, friends, and school, they can have a clear plan for their career development (Healy et al., 2022). It will guide graduate students to have more optimistic behaviors in the job search process and promote the realization of high-quality employment. Secondly, with social capital, interpersonal transaction costs are significantly reduced. At this point, trust between the parties is higher, and the chances of success significantly increase (Wang, 2013). Finally, resource preservation theory points out that people always make active efforts to establish and maintain valuable resources in their eyes, and social capital is a kind of resource (Dong and Geng, 2023). The higher the level of social capital an individual owns, the higher the level of career support it provides, the greater the help it provides for employment, the easier it is to obtain competitive advantages in the labor market, and the higher the quality of employment. In summary, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 2A: Postgraduate students' social capital positively affects subjective employment quality.

Hypothesis 2B: Postgraduate students' social capital positively affects objective employment quality.

The mediating role of employability

Employability is generally considered to be the ability of individuals in organizations to cope with the challenges of a borderless career, externalization of employment relationships, obtaining work, and maintaining work within and across organizations arising from a volatile professional environment, and is a crucial factor in career success (Bagshaw, 1997; Finn, 2000; Fugate et al., 2004). Yorke (2006) argued that employability depends on a synergistic mix of personal qualities, various skills, and disciplinary understanding, and developed the USEM model. Fugate et al. (2004) believe that employability is a kind of active job adaptability from the perspective of psychosocial structure, including three key dimensions: professional identity, personal adaptability, and social and human capital. Some domestic scholars translate employability as “employability” to study the relationship between employability and employment quality.

Employability guarantees employment quality and competitiveness in the current situation, and human capital significantly impacts employability (Hu and Shen, 2020; Zong and Zhou, 2012). Individuals build employability by investing in continuous learning by developing their human capital. First, according to resource conservation theory (Hobfoll, 1989), human capital is a resource that can help individuals obtain other resources, which is a kind of energy resource. When individuals have more resources, they can obtain other resources. Therefore, the higher human capital stock possessed by graduate students means that individuals acquire more knowledge and skills, which will help them improve themselves through continuous accumulation and have advantages in career competition with higher employability. Secondly, the higher the human capital is, the more likely an individual is to improve himself/herself by accepting external information and resources and obtaining more external machines, resulting in a value-added spiral effect and higher employability (Nghia et al., 2020).

Social capital may also have a positive effect on the employability of graduate students. Social capital refers to an individual’s social networks and the strength and size of those networks (McArdle et al., 2007), and some research suggests that social capital can influence employability. First, universities can help graduates build strong networks (e.g., alum associations) by expanding their student base and teaching them to build networks before they enter the labor market. In that case, this can further increase graduate employability. Second, social capital can make individuals more employable by developing their ability to identify and realize opportunities across organizations, industries, and careers (Anand and Poggi, 2018). In addition, according to resource conservation theory (Hobfoll, 1989), social capital is regarded as an individual resource. Individuals with high social capital can obtain career-related networks, information resources, and social support in job-hunting (Fugate et al., 2004). Moreover, social capital provides individuals with social relationships and a network of contacts to improve employability and provides opportunities to achieve career ambitions in job search employment.

Research has shown that employability improves employment quality (González-Romá et al., 2018). Many universities have incorporated specific elements of employability into their curricula to improve graduates’ employment prospects and outcomes. Employability is the ability of individuals to clarify “who I am” and “who I want to be” in the workplace (Fugate et al., 2004). It has specific employment motivation to guide, regulate, and maintain individual job-hunting behaviors, prepare for employment goals, and improve the chances of achieving goals. Their job-hunting goals are more focused, they are more likely to achieve “ideal goals” to be hired, and they have higher satisfaction, employment matching degree, and employment quality. Secondly, the job market has increasingly high requirements and expectations for graduates, and they must constantly adapt to the job market flexibly. Employability is the ability of individuals to change their behavior, emotions, and thoughts in response to external changes, which helps individuals identify career opportunities in a changing environment and better deal with problems and uncertainties encountered in the labor market (Römgens et al., 2020). Therefore, compared with individuals with low employability, individuals with high employability are more likely to find jobs and have higher employment quality. Finally, employability considers the extent to which individuals can achieve sustainable employment. When individual employability is higher, it facilitates individual mobility between jobs and organizations and increases the likelihood that individuals will be employed and remain employed, improving the quality of employment. According to resource conservation theory (Hobfoll, 1989), individuals will endeavor to maintain their resources and avoid losing them at work, thus maintaining good working conditions and improving job satisfaction. Therefore, individuals can achieve better subjective and objective employment quality by enhancing human and social capital accumulation and improving employability. In summary, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 3A: Employability mediates between human capital and subjective employment quality.

Hypothesis 3B: Employability mediates between human capital and objective employment quality.

Hypothesis 3C: Employability mediates between social capital and subjective employment quality.

Hypothesis 3D: Employability mediates between social capital and objective employment quality.

The contingent role of future career clarity

Future career clarity means that an individual has a clear understanding of his career goal, the ways to achieve the goal, the ways to advance his career development, the obstacles he may encounter, and the ways to deal with them (Guo et al., 2005). It has an impact on an individual’s job-hunting behavior. Future career clarity can help individuals better plan and preserve their resources. Precise career planning allows individuals to understand better their career goals and directions, which can lead to better accumulation of human and social capital and improved employability and quality of employment for individuals (Zhang, 2023). The goal-setting theory points out that an individual’s way of action is determined by the individual’s psychological and subconscious goals and objectives. Specific and clear goals can motivate individuals more than vague goals, and clear goals will prompt individuals to take action in the direction they are directed (Leondari et al., 1998). When individuals have a high sense of future career clarity, they will compare their current career situation with their future expectations, thus generating motivation to change or achieve self-development. Job seekers who lack a clear job objective may spend more time trying out different ideas and thinking about their future career development and thus may lower their job-hunting behavior. Therefore, future career clarity may play a role in promoting the positive effects of human capital, social capital, and employability of graduate students (Shen et al., 2024). When graduate students have a higher sense of future career clarity, the individual may have a more robust job intention and work toward their goal, thus exhibiting more job-hunting behaviors and enhancing employability. In summary, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 4A: Postgraduate students' future career clarity positively moderates the relationship between graduate students' human capital and employability. The stronger graduate students' future career clarity, the greater the impact of human capital on employability.

Hypothesis 4B: Postgraduate students' future career clarity positively moderates the relationship between graduate students' social capital and employability. The stronger the clarity of graduate students' future careers, the greater the impact of social capital on employability.

The contingent effect of employment policy support

Employment policy is a series of schemes and measures adopted by the state and the government to solve the problem of employment of workers. General active labor employment policies include direct job creation, public employment services or job search assistance agents, training for the unemployed, and employment subsidies for companies that hire unemployed individuals (Vooren et al., 2019). The relevant policies for college students mainly include broadening the employment channels for college students, encouraging enterprises to expand the scale of absorption, expanding the scope of grass-roots employment, extending the length of employment probation, appropriately delaying the acceptance of employment, and giving employment subsidies to poor college students, etc. Among all labor market policy interventions, the policy aimed at increasing labor demand and promoting employment is called Active Labor Market Policy. Research has shown that employment policy support will reduce the difficulty of job hunting and improve the individual employment rate and employment quality (Martin and Grubb, 2001). Employment policy support can provide policy guarantees for graduates, reduce information barriers, and create an excellent job-hunting environment (Mok, 2018). When employment policy support is more robust, various ineffective influences in the social environment can be avoided, and graduates with high employability are more likely to find satisfactory jobs with higher employment quality. In summary, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 5A: Employment policy support positively affects the relationship between employability and subjective employment quality. The stronger the employment policy support, the greater the impact of employability on subjective employment quality.

Hypothesis 5B: Employment policy support positively affects the relationship between employability and objective employment quality, the stronger the employment policy support, the greater the impact of employability on objective employment quality.

The theoretical model are shown in the Figure 1.

Materials and methods

Samples and research procedures

The research mainly adopts the method of the questionnaire survey, which is divided into three main stages: firstly, mature questionnaires at home and abroad are selected, and the accuracy of translation of English questionnaires is guaranteed through Chinese and English translation; after that, 116 pre-survey samples were collected to test the reliability and validity of the sample questionnaires. Finally, through the recruitment office of colleges and universities, counselors in charge of postgraduate employment collected 870 questionnaires in Sichuan, Chongqing, Hunan, and other places by electronic questionnaire, of which 778 were valid, and the effective rate of the samples was 89.4%. In the survey sample, female students accounted for 40.1%, male students accounted for 59.9%, rural students accounted for 69.3%, and urban students accounted for 30.7%. This research uses SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 24.0 software to test the research hypotheses.

Measuring tools

Dependent variables: subjective employment quality and objective employment quality

Subjective employment quality

According to Cheng and Xu (2016) study, subjective employment quality includes four indicators and one dimension to measure subjective employment quality: “professional interest fit,” “professional matching,” “salary expectation fit,” and “personal career development impact.” Examples of question indicators are “My job is in line with my interests,” “the salary offered by the employer is satisfactory” and so on. After setting the number of extracted factors to 1, the component matrix scores of each indicator were 0.614, 0.843, 0.872, 0.785, respectively. After testing, the scale has good reliability and validity, the KMO value is 0.758, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.787 (n = 778), and the cumulative variance interpretation rate is 61.767%.

Objective employment quality

In a synthesis of Cheng and Xu (2016) and Wang’s (2018) study, objective employment quality includes four indicators: “salary level,” “workplace,” “job search time,” and “enterprise visibility.” Which was mainly measured by four question indicators such as the number of offers received and the average monthly salary given in the first year of the unit signed. The code is coded as 1 to 5 from low to high according to the hierarchical level, and then the average level of the four objective employment quality items is calculated using the continuous variable calculation method.

Independent variables: human capital and social capital

Human capital

Using Qiao et al. (2011) and Wang’s (2018) study measurement, the main indicators used for human capital include 10 measurement questions: the level of graduate schools; Graduate English level certificate level; Student cadres and professional skills are measured in 10 aspects, the code is coded as 1 to 5 from low to high according to the level of the hierarchy, and then the continuous variable calculation method is used to calculate the average level of human capital.

Social capital

Synthesis of Wang’s (2013) and Wang’s (2018) study, one dimension containing five question items were used to measure social capital, such as: “I know a lot of people who are helpful for my job search,” “Most of the people who are helpful for my job search have the good educational background and social status,” etc. After setting the number of extracted factors to 1, the component matrix scores of the five indicators were 0.676, 0.734, 0.664, 0.666, and 0.520, respectively. The scale KMO value is 0.631, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.657, and the cumulative variance explanation rate is 65.429%.

Mediating variable: employability

The employability questionnaire compiled by Berntson and Marklund (2007) has been verified to have good reliability and validity, which includes 1 dimension and 5 items, such as “My abilities are highly sought after in the labor market”; “I can use my social network resources to find a new job that is similar or better than my current one.” After setting the number of extracted factors to 1, the component matrix scores of each index were 0.779, 0.750, 0.744, 0.790, and 0.775, respectively. The KMO value of the scale was 0.844, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.823, and the variance interpretation rate was 58.749%.

Moderating variables: future career clarity and employment policy support

Future career clarity

Future career clarity scale developed by Strauss et al. (2012) was adopted, a total of 1 dimension and 5 items. For example: “I can easily imagine what my future job will be like,” “the future work scenario is very clear in my mind” and so on. After setting the number of extracted factors to 1, the component matrix scores of each index were 0.862, 0.896, 0.881, 0.858, and 0.885, respectively. The KMO value of the scale was 0.877, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.924, and the variance interpretation rate was 76.799%.

Employment policy support

Employment policy support adopts a self-compiled questionnaire to measure the degree of government, school, and other support for college students’ employment. It has one dimension, including three questions. Typical questions include: “Many employment support policies issued by the national and local governments are helpful to my employment.” After testing, the scale has good reliability and validity. After setting the number of extracted factors to 1, the component matrix scores of the three indicators were 0.851, 0.858, and 0.831, respectively. The KMO value of the scale is 0.711, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.803, and the variance interpretation rate is 71.84%.

Controlled variables

Gender, native place, and other background variables were used as controled variables. Background variables were coded as 0 for females and 1 for males; The country of origin code is 0 and the town code is 1. The remaining questions were all on a five-point Likert scale, with a scale from 1 to 5 indicating “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Results

Reliability testing

Since human capital and objective employment quality were not measured using latent variables and Likert scales, but were calculated using specific correlates, reliability and validity tests were not required. The remaining variables were measured using latent variables and the reliability of the questionnaire was tested using Cronbach’s α. The social capital, employability, subjective employment quality, future career clarity, and employment policy support Cronbach’s α values were 0.662, 0.824, 0.786, 0.924, 0.802, respectively. The KMO values were used to determine the appropriateness of the scale to for factor analysis. The KOM values for social capital, employability, subjective employment quality, future career clarity, and employment policy support were 0.629, 0.845, 0.757, 0.878, and 0.710, respectively. From the above description, it can be seen that the Cronbach’s alpha values were higher than 0.6 for all the variables, 0.8 for most of the scales, and the KMO values were higher than 0.6 and most of the scales had KMO values above 0.8. Therefore, the questionnaire has good reliability and validity and is suitable for factor analysis.

In this study, AMOS 24.0 was used to test the discriminant validity of the research models of human capital, social capital, employability, subjective employment quality, objective employment quality, future career clarity, and employment policy support, and the results are shown in Table 1. The seven-factor model fits the best, with the /df less than 3, and with the CFI, TLI, IFI, GFI, AGFI, and are all greater than 0.9. RMSEA is less than 0.08, and all the indicators are within the standard, indicating a good discriminatory validity between the variables.

Common method variances test for the questionnaire

In this study, Harman single factor test was used to test the common variance bias, and all items were analyzed by unrotated factor. The results show that the variance in the first principal component variance explanation is 19.676%, which does not exceed the recommended value of 50%. Therefore, it can be determined that the common method bias has no significant influence on the results.

Descriptive statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were conducted on 7 variables, including human capital, social capital, employability, future career clarity, employment policy support, subjective employment quality and objective employment quality (see Table 2). All research hypotheses except Hypothesis 1A were preliminarily verified.

Hypothesis testing

To further understand the relationship between human capital, social capital, subjective employment quality, and objective employment quality, this study explores the relationship among variables through hierarchical regression after controlling the gender and household registration of postgraduates. The regression results of human capital on subjective and objective employment quality are shown in Model 2 and Model 5 in Table 3. The effect of human capital on subjective employment quality is not significant (β = 0.000, p > 0.05), hypothesis 1A is not verified. Human capital positively affects objective employment quality (β = 0.243, p < 0.001), hypothesis H1B is verified. As shown in Model 3 and Model 6 in Table 3, social capital has a significant effect on both subjective employment quality (β = 0.379, p < 0.001), hypothesis 2A is verified. The effect of social capital on objective employment quality is not significant (β = 0.064, p > 0.05), hypothesis 2B is not verified.

Table 3. Hierarchical regression results of human capital and social capital on subjective and objective employment quality (n = 778).

In this paper, the mediation effect judgment procedure proposed by Wen and Ye (2014) was used for testing.

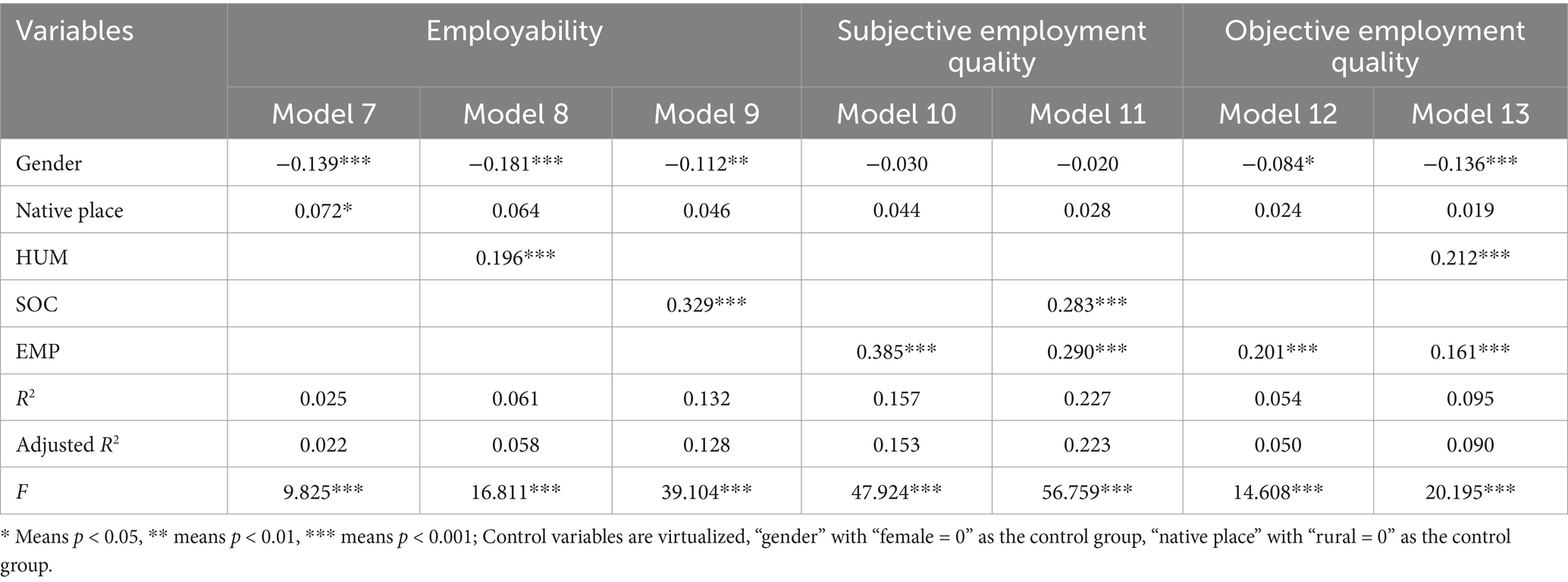

From the above, it can be seen that human capital significantly and positively affects objective employment quality (β = 0.243, p < 0.001). As shown in Model 8 of Table 4, human capital significantly positively affects employability (β = 0.196, p < 0.001). As shown in model 12 in Table 4, it can be seen that employability has a significant positive effect on objective employment quality (β = 0.201, p < 0.001). As shown in model 13 in Table 4, after introducing the mediating variable employability, the influence of human capital on objective employment quality is weakened, but still significant (β = 0.212, p < 0.001), and the effect of employability on objective employment quality is still significant (β = 0.161, p < 0.001). It shows that employability partially mediates the positive effect of human capital on objective employment quality, and hypothesis 3B is preliminarily supported. Similarly, the Bootstrap method was adopted to further test the mediating effect, as shown in Table 5. With the addition of control variables, the direct effect of human capital on objective employment quality was significant (effect value = 0.2499, 95%CI [0.1670, 0.3328]). The positive indirect effect through employability is still significant (effect value = 0.0371, 95%CI [0.0144, 0.0666]). Therefore, employability plays an intermediary role between human capital and objective employment quality, and hypothesis 3B is again supported.

It can be seen from the above that social capital has a significant positive effect on subjective employment quality (β = 0.379, p < 0.001). As shown in model 10 in Table 4, and employability has a significant positive effect on subjective employment quality (β = 0.385, p < 0.001), which has been verified and supported. It can be seen from Model 9 in Table 4 that social capital has a significant positive impact on employability (β = 0.329, p < 0.001); Model 11 in Table 4 shows that, after the introduction of employability as an intermediary variable, the effect of social capital on the subjective employment quality is weakened, but still significant (β = 0.283, p < 0.001), and the effect of employability on the subjective employment quality is still significant (β = 0.290, p < 0.001). It indicates that employability partially mediated social capital has a positive impact on subjective employment quality, and hypothesis 3C is preliminarily supported. Similarly, the Bootstrap method was used to further test the mediating effect, as shown in Table 5. With the addition of control variables, the direct effect of social capital on the subjective employment quality was significant (effect value = 0.3148, 95%CI [0.2412, 0.3885]). The positive indirect effect through employability is still significant (effect value = 0.1064, 95%CI [0.660, 0.1509]). Therefore, employability has a mediating effect between social capital and subjective employment quality. Hypothesis 3C is again supported.

In this study, hierarchical regression and Process plug-in were used to verify the moderating effect. The results are shown in Model 15 in Table 6. The interaction term of human capital and future occupation clarity has a significant effect on employability (β = 0.098, p < 0.01), indicating that future occupation clarity has a positive moderating effect on human capital and employability, and hypothesis 4A is supported.

Table 6. Regression results on the moderating effects of future career clarity and employment policy support (n = 778).

Similarly, according to the above test steps, the results are shown in Model 17 in Table 6. The interaction term between social capital and future career clarity has no significant effect on employability (β = −0.014, p > 0.05), indicating that future career clarity has no moderating effect on the influence of social capital on employability, and4B is not supported.

In Table 6 model 19, the interaction term between employability and employment policy support has a significantly negative effect on subjective employment quality.(β = −0.099, p < 0.01), indicating that employment policy support negatively moderates employability and subjective job quality, hypothesis 5A is not supported.

Similarly, according to the above steps, it is found that the interaction term between employability and employment policy support in Model 21 in Table 6 has a significantly negative effect on objective employment quality (β = −0.079, p < 0.05), indicating that employment policy support has a negative moderating effect on employability and objective employment quality, and hypothesis 5B is not supported.

Based on the above results, to clarify the relationship between graduate students’ future career clarity regulating human capital and employability, a schematic diagram of the adjustment effect was drawn. The average score of future career clarity was divided into two groups of plus or minus one standard deviation, high value, and low value, respectively. And the obtained results are displayed. As can be seen from Figure 2, the influence of human capital on employability is on the rise with the improvement of future job clarity. Therefore, hypothesis H4A is supported.

Figure 2. The moderating effect of future career clarity on the influence of human capital on employability.

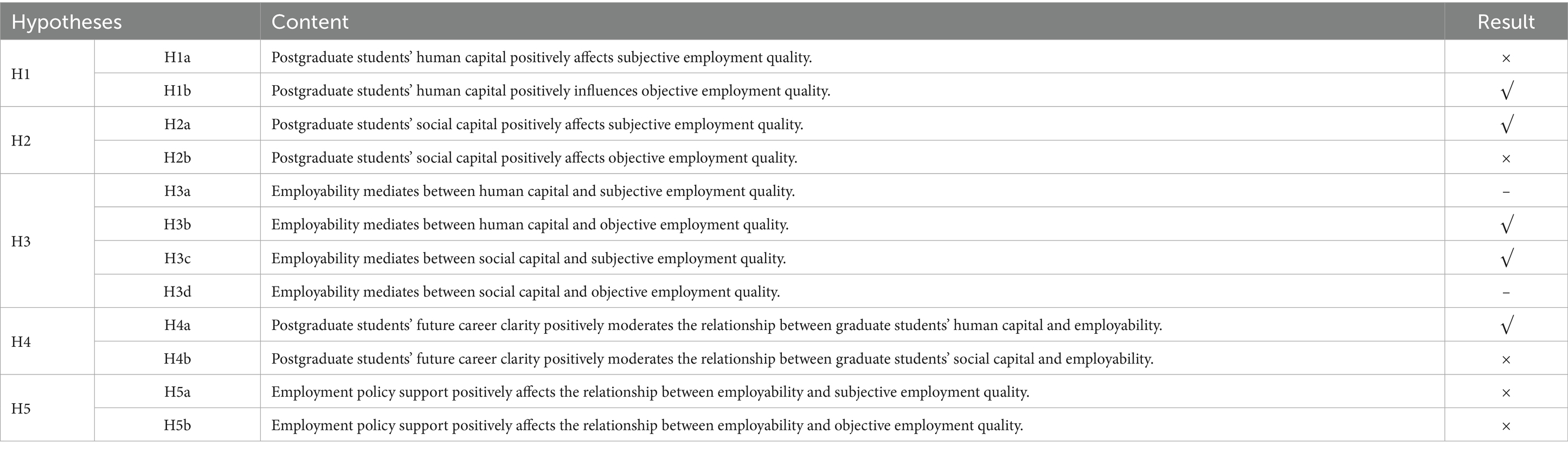

Integrating all test results to obtain the following summary table of hypothesis results (Table 7).

Discussion

Research conclusion

The following conclusions are drawn by establishing the relationship model of human capital, social capital, employability of graduate students, and employment quality and the empirical analysis:

(1) Human capital positively affects objective employment quality. It has no significant effect on subjective employment quality. Social capital positively affects subjective employment quality and has no significant effect on objective employment quality. This study reconfirms differences in the effects of human and social capital on the quality of employment. Human capital has a higher effect on objective employment quality, such as income level and employment stability, than social capital, while social capital has a higher effect on subjective employment quality, such as employment satisfaction, than human capital. Human and social capital impact employment quality, once again disproving the idea that “studying is useless” in society.

(2) Employability mediates the relationship between human capital and objective employment quality. Employability mediates between human capital and objective employment quality. When graduate students have a higher degree of human capital and social capital, their employability is stronger, corresponding to a higher subjective employment quality and objective employment quality.

(3) Future career clarity positively moderates the relationship between human capital and graduate students’ employability. When graduate students possess a higher sense of future career clarity, the greater the positive effect of human capital on graduate students’ employability in the labor market. Sense of future career clarity does not mediate between social capital and employability. This study analyzes the possibility that personal interests, personality, and job market may also impact the relationship between social capital and employability, resulting in the moderating role of a sense of clarity of future career may vary depending on the individual and the environment.

(4) Employment policy support negatively moderates the relationship between graduate student employability and subjective and objective job quality. The positive effect of employability on employment quality was weakened by employment policy support. This is contrary to previous fixed impressions. The possibility that the correct implementation of policies may result in graduate students not fully benefiting is as follows: firstly, graduate students with high employability may weaken their job search efforts due to feeling less work pressure and believing that they can find high-quality jobs with the support of employment policies. Secondly, highly employable graduate students are prone to overconfidence, high job expectations, and neglect of actual market competition under policy support. Thirdly, based on the crowding out effect theory, employment policy support weakens the job seeking advantage of highly employable graduate students, and instead reduces their employment quality. Fourth, the labor job market is unstable due to the new crown epidemic, and the actual jobs found do not match expectations, weakening employability’s positive impact on subjective job quality. Finally, different employment policies play different roles in different aspects of employment.

Theoretical implications

Firstly, it enriches the relevant research on the impact of subjective and objective employment quality of graduate students. The study analyzes several factors, including human capital, social capital, employability, future career clarity, and employment policy support, fully consider the factors that influence the quality of graduate student employment compared to previous research. Previous studies mainly focused on the impact of job seeker capital on the quality of employment, while this study provides a more comprehensive perspective, helping to better understand the complexity and dynamic changes of graduate employment quality. In this study, the resource conservation theory, human capital theory, social capital theory and goal setting theory are integrated into the unified model, and the linkage mechanism of influencing factors of graduate employment quality is explained. At the same time, the research reveals the path of human capital and social capital to the difference of employment quality, echoing the previous point of view. What is more, it differs from previous studies that only studied objective or subjective dimensions or weighted both into one variable of employment quality, this study separated and analyzed the mechanism of subjective and objective employment quality under the same framework, which is more conducive to observing the effects of different influencing factors on the two and then proposing targeted countermeasures.

Secondly, it opens the “black box” between human capital, social capital, and employment quality. In this study, employment ability is introduced as an intermediary variable, and it is verified for the first time that employment ability is the core intermediary of human capital into objective employment quality. Not only focusing on the direct impact of resources on employment quality, it also considers how resources indirectly affect employment quality by influencing employability, and expanded the study of employability in employment quality and provides new ideas for future research.

Thirdly, the future career clarity was included in the model as a regulatory variable to confirm that it can strengthen the transformation of human capital to employability. Previous studies mostly focused on the current employment environment, but this study explored the regulatory role of future career clarity and employment policy support. Meanwhile, this study incorporates employment policy support into the model, which challenges the inherent cognition that “policies inevitably promote employment,” providing a new perspective for understanding the effects of employment policies. It helps researchers understand the relationship between employment, future career clarity, and employment policy support. Possible policy recommendations are also made to improve the quality of graduate students’ employment.

Practical implications

Firstly, develop human capital and improve the employment quality of postgraduates. Human capital is the main factor affecting postgraduates’ employability and employment quality. First, colleges and universities should carefully design the course training program, meet social needs, set up theoretical and practical courses, systematically train students’ professional ability, improve human capital, and lay a good foundation for the appropriate increase of students’ future employment. Second, postgraduates should improve their professional ability through systematic professional course learning, professional certificates, data ability, and professional competitions, to obtain the core competitiveness of the job market and improve the objective employment quality. Third, postgraduate students should actively participate in social practice, club activities, and volunteer services to improve the comprehensive quality. In addition to professional learning, under the premise of meeting their planning, graduate students should try their best through social practice, community activities, voluntary service, innovation and entrepreneurship training plans, and other ways of systematic organization ability, pressure management ability, communication and coordination ability, improve their comprehensive quality, be favored by more high-quality employers.

Secondly, build social capital to improve the employment quality of postgraduates. Social capital also affects the employability and employment quality of postgraduates. First, universities should establish a good reputation and provide alum resources, actively provide students with internships and opportunities to contact employers, actively guide and help students to accumulate social capital, give full play to the role of alum associations, and provide students with more abundant social capital from the university. Second, families should actively help graduate students search for employment information, promote the mutual conversion between graduate human capital and social capital, and create their own new human capital and social capital. Third, students should realize the positive role of social capital. In the context of China, for graduate students, consciously building their social capital through alum resources and social network links is an essential aspect of improving future employment quality.

Thirdly, employability should be improved to increase the employment quality of postgraduates. The employability of graduate students plays an important intermediary role between capital and employment quality. First, schools and supervisors should pay attention to the training of graduate students’ practice and employability to improve their employability. Take the initiative to incorporate the development of employability and employability into the training objectives of postgraduates, take into account the demands of students, the government, and the market, clarify the employment direction, and cultivate high-level professional talents who are oriented by the needs of the industry and consistent with the vocational requirements of the industry. Second, postgraduates should establish a clear employment direction, improve learning awareness and learning ability, solve practical problems in subject research, social services, and practical work, gain direct experience to improve employability, strengthen their internal and external competitiveness, improve employment matching degree and satisfaction. Third, in the process of job hunting, dynamic adjustments of job objectives should be made according to the external environment for postgraduates, enhance job hunting confidence, and improve their employability.

Fourthly, create an excellent internal and external environment to improve the employment quality of postgraduates. It is found that the clarity of graduate students’ future careers regulates the relationship between human capital and employability of graduate students, the support of employment policies regulates the relationship between employability and employment quality. Therefore, the government should introduce relevant policies to promote graduate students’ employment at the macro level to explore employment channels. Schools should strengthen the publicity of employment work and provide employment policies and information. Enterprises can sincerely cooperate with colleges and universities to conduct efficient online and offline recruitment and jointly create an excellent external employment environment. Graduate students’ future career clarity is a critical contingency factor in changing their employability. Therefore, schools should guide graduate students to make career plans, clear professional cognition, and understand professional career channels as soon as possible. Supervisors should determine the career development direction with postgraduates in advance and provide personalized guidance and training programs. Postgraduates should make clear the employment direction and goal, complete preparations during the study period.

Research limitations and prospects

Firstly, the data were self-assessed. Although the homoscedasticity covariance test using Harman’s single factor analysis confirmed that the data did not suffer from serious common method bias, various data collection methods could still be used in the future, depending on the nature of the variables. For example, the three-stage method and a combination of self-assessment and other assessments can further enhance the study’s rigor.

Secondly, the stability and reliability of the self-administered scales need to be further tested. Since there is no referable scale for employment policy support, a new scale was developed for this study. The scale passed the reliability and validity tests, but more research is needed to test the stability and reliability of the questionnaire. In addition, employment policy support is a multidimensional concept, and its measurement may require more comprehensive indicators and instruments. Future research can further refine and improve the measurement of employment policy support, including the specific content of the policy, its implementation, and the evaluation of its effects.

Thirdly, the study sample has some limitations. The study only collected 778 surveys and cross-sectional data through team resources. In the future, we can cooperate with large employment research organizations to obtain big data. At the same time, the research subjects only cover graduate students from universities in Sichuan, Chongqing, Hunan and other places, which may not be representative nationwide. Future research should use scientific sampling methods to expand the sampling range, or use tracking data. This will enable the study to have better external validity and verify the model’s applicability and generalizability in different contexts. In addition, in the future, we will characterize the differences in the impact of human capital, social capital, future career clarity, and employment policy support for different groups to make the research conclusions more in-depth. In terms of regulatory factors, the impact of different cultural backgrounds and institutional factors on graduate employment should also be considered in the future to improve the rigor of the research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TZ: Writing – original draft. RG: Writing – original draft. SY: Writing – original draft. CS: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the construction of a human resource management laboratory for first-class professional services in agricultural and forestry colleges (Project No. 202102477055); The Ministry of Education’s Industry-Academia Collaborative Education Project “Construction of a Public Management Experimental Platform in Agricultural and Forestry Colleges in the Digital Age” (Project No. 231101456281106); China Academic Degree and Graduate Education Society (NLZX-YB94); The Ministry of Education of China Industry-Academia Collaborative Education Project, “Construction of the Human Resource Management Laboratory to Support the Digital Transformation of Agricultural and Forestry Universities” (Project No. 231101712151156); and The 2024-2026 Sichuan Provincial Higher Education Talent Cultivation Quality and Teaching Reform Project, “Exploration and Practice of the ‘Four-in-One’ Public Management Digital-Intelligence Talent Cultivation Model in Agricultural and Forestry Universities” (Project No. JG2024-0441).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anand, P., and Poggi, A. (2018). Do social resources matter? Social capital, personality traits, and the ability to plan ahead. Kyklos 71, 343–373. doi: 10.1111/kykl.12173

Bagshaw, M. (1997). Employability-creating a contract of mutual investment. Ind. Commer. Train. 29, 187–189. doi: 10.1108/00197859710177468

Baldi, F., and Trigeorgis, L. (2020). Valuing human capital career development: a real options approach. J. Intellect. Cap. 21, 781–807. doi: 10.1108/JIC-06-2019-0134

Benati, K., and Fischer, J. (2020). Beyond human capital: student preparation for graduate life. Educ. Train. 63, 151–163. doi: 10.1108/ET-10-2019-0244

Berntson, E., and Marklund, S. (2007). The relationship between perceived employability and subsequent health. Work Stress. 21, 279–292. doi: 10.1080/02678370701659215

Bourdieu, P. (1980). Le capital social: notes provisoires. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 31, 2–3.

Bourdieu, P. (1997). “The forms of social capital” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, New York, USA. Ed. John G, Richardson. 241–258.

Chen, T. (2015). A review of the research on the employment quality of college students. J. Chin. Youth Soc. Sci. 34, 133–137. doi: 10.16034/j.cnki.10-1318/c.2015.03.024

Cheng, W., and Xu, J. (2016). Research on the relationship between employability and employment quality of college students. Educ. Vocat. 18, 80–84. doi: 10.13615/j.cnki.1004-3985.2016.18.026

Ding, S., and Liu, C. (2022). Research on the impact of internet use on employment quality in the era of digital economy-- -from the perspective of social network. Res. Econ. Manag. 43, 97–114. doi: 10.13502/j.cnki.issn1000-7636.2022.07.006

Dong, X., and Geng, L. (2023). Nature deficit and mental health among adolescents: a perspectives of conservation of resources theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 87:101995. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101995

Finn, D. (2000). From full employment to employability: a new deal for Britain’s unemployed? Int. J. Manpow. 21, 384–399. doi: 10.1108/01437720010377693

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., and Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: a psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

González-Romá, V., Gamboa, J. P., and Peiró, J. M. (2018). University graduates’ employability, employment status, and job quality. J. Career Dev. 45, 132–149. doi: 10.1177/0894845316671607

Guo, Y., Chen, J., and Wang, L. (2005). Occupational clarity: concepts, survey analysis, and applications. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2, 22–25. doi: 10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2005.02.005

Healy, M., Hammer, S., and McIlveen, P. (2022). Mapping graduate employability and career development in higher education research: a citation network analysis. Stud. High. Educ. 47, 799–811. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1804851

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hu, S., and Shen, C. (2020). Effect of perceived employability on active job-seeking behavior and subjective well-being of university graduates: a moderated mediation model. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 28, 126–131. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.01.027

Leondari, A., Syngollitou, E., and Kiosseoglou, G. (1998). Academic achievement, motivation and future selves. Educ. Stud. 24, 153–163. doi: 10.1080/0305569980240202

Li, Y., Liu, S., and Wong, S. (2005). The influence of college students' employability on employment quality. High. Educ. Explor. 2, 91–93.

Li, H., Liu, K., Yang, Y., and Zhang, J. (2022). Research on the employment quality Evaluation, Influencing factors and promotion ways of college masters in first-tier cities. Northwest Popul. J. 43, 114–126. doi: 10.15884/j.cnki.issn.1007-0672.2022.02.010

Li, Y., and Zhang, S. (2020). What kind of youth's social capital is more useful? -- a reexamination of the income effect of human capital and social capital. China Youth Stud. 6, 13–19+51. doi: 10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2020.0080

Lieberman, S. (1956). The effects of changes in roles on the attitudes of role occupants. Hum. Relat. 9, 385–402. doi: 10.1177/001872675600900401

Liu, Y., Liang, X., and Zhang, Y. (2018). The influence of human Capital of new Generation Migrant Workers on employment quality. World Surv. Res. 303, 30–35. doi: 10.13778/j.cnki.11-3705/c.2018.12.006

Liu, M., Lu, G., Pan, B., and Li, Z. (2018). Evaluation on the employment quality index of college graduates: an empirical analysis of Shaanxi Province. Fudan Educ. Forum 16, 70–75. doi: 10.13397/j.cnki.fef.2018.05.010

Locke, E. A., and Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57, 705–717. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Luo, H., and Wang, B. (2020). Effect of social capital on graduate employment and optimizing strategies. J. Southwest China Normal Univ. 45, 80–86. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xsxb.2020.05.013

Martin, J. P., and Grubb, D. (2001). What works and for whom: a review of OECD countries' experiences with active labour market policies. Swedish Econ. Policy Rev. 8, 9–56. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.348621

McArdle, S., Waters, L., Briscoe, J. P., and Hall, D. T. T. (2007). Employability during unemployment: adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. J. Vocat. Behav. 71, 247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.003

Mok, K. H. (2018). Promoting national identity through higher education and graduate employment: reality in the responses and implementation of government policy in China. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 40, 583–597. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2018.1529127

Nadler, D. A., and Lawler, E. E. (1983). Quality of work life: perspectives and directions. Organ. Dyn. 11, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/0090-2616(83)90003-7

Nghia, T. L. H., Singh, J. K. N., Pham, T., and Medica, K. (2020). “Employability, employability capital, and career development: a literature review” in Developing and utilizing employability capitals, London, UK. Eds. Nghia, T. L. H., Pham, T., Tomlinson, M., Medica, K., and Thompson, C.. 41–65.

Piasna, A., Burchell, B., and Sehnbruch, K. (2019). Job quality in European employment policy: one step forward, two steps back? Transfer Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 25, 165–180. doi: 10.1177/1024258919832213

Qiao, Z., Song, H., Feng, M., and Shao, Y. (2011). Human capital, social capital and employment of Chinese college students. China Youth Stud. 4, 24–28. doi: 10.19633/j.cnki.11-2579/d.2011.04.007

Römgens, I., Scoupe, R., and Beausaert, S. (2020). Unraveling the concept of employability, bringing together research on employability in higher education and the workplace. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 2588–2603. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1623770

Schroeder, F. K. (2007). Workplace issues and placement: what is high quality employment? Work 29, 357–358. doi: 10.3233/wor-2007-00673

Shen, P., Wu, Y., Liu, Y., and Lian, R. (2024). Linking undergraduates' future orientation and their employability confidence: the role of vocational identity clarity and internship effectiveness. Acta Psychol. 248:104360. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104360

Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., and Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: how salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 97, 580–598. doi: 10.1037/a0026423

Szromek, A. R., and Wolniak, R. (2020). Job satisfaction and problems among academic staff in higher education. Sustainability 12:4865. doi: 10.3390/su12124865

Vooren, M., Haelermans, C., Groot, W., and Maassen van den Brink, H. (2019). The effectiveness of active labor market policies: a meta-analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 33, 125–149. doi: 10.1111/joes.12269

Wang, L. (2013). A study on improving college students' employability based on social capital theory. Cult. Educ. Mater. 6, 134–135.

Wang, F. (2018). The structural optimization of college students' employability based on the coupling of supply and demand and its empirical study. (Doctor). Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province, China: China University of Mining and Technology.

Wang, T. (2020). The influence mechanism of the graduates' high quality employment: from the perspective of human capital and social capital. High. Educ. Explor. 2, 108–114.

Wen, Z., and Ye, B. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 22, 731–745. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00731

Xu, X. (2002). The dual mechanism of college students' employment: human capital and social capital. Youth Stud. 6, 9–14.

Yan, F., and Dan, M. (2015). The impact of social capital on the employment of college graduates. Chin. Educ. Soc. 48, 59–75. doi: 10.1080/10611932.2015.1014708

Yang, Y., and Wang, Y. (2020). A study on future career development and the trend thereof of postgraduates in China: based on analysis of data from 2014 to 2018 at universities directly under the Ministry of Education. J. Grad. Educ. 5, 58–65+73. doi: 10.19834/j.cnki.yjsjy2011.2020.05.09

Yang, S., Yang, J., Yue, L., Xu, J., Liu, X., Li, W., et al. (2022). Impact of perception reduction of employment opportunities on employment pressure of college students under COVID-19 epidemic–joint moderating effects of employment policy support and job-searching self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 13:986070. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.986070

Yorke, M. (2006). Employability in higher education: What it is-what it is not, vol. 1. Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK: Higher Education Academy York.

Yue, D., and Tian, Y. (2016). Human capital and employment quality of college students: the mediating role of professional identity. Jiangsu High. Educ. 1, 101–104. doi: 10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2016.01.028

Zhang, L. (2023). The pathway to precise employment of college students in the context of the new era. Front. Soc. Sci. Technol. 5, 24–28. doi: 10.25236/FSST.2023.051104

Keywords: human capital, social capital, employment quality, future career clarity, employment policy support

Citation: Zhang T, Gao R, Yang S and Shi C (2025) Research on the influence of human capital and social capital on subjective and objective employment quality paths of graduate students in China. Front. Educ. 10:1525049. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1525049

Edited by:

Daisheng Tang, Beijing Jiaotong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nuryake Fajaryati, Yogyakarta State University, IndonesiaAlvin Permana Emur, University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Gaukhar Niyetalina, Turan University, Kazakhstan

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Gao, Yang and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiyuan Yang, bG92ZXlzeTA2MDRAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Tao Zhang1

Tao Zhang1 Shiyuan Yang

Shiyuan Yang