- School of Education, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, United States

Succession planning is typically rooted in linear models of transition informed by supply-and-demand rationales about the available pool of leaders to fill positions and the efficient transfer of information to new leaders. Equity-oriented leaders with commitments to community-engagement, however, represent different logics of expertise, which elevate knowledge of context and culture and enact collectivist and collaborative practices of leadership. This paper considers the adequacy of traditional succession planning for the continuity of leaders with non-traditional orientations to leadership. We build on an equity-centered model of succession planning–Dynamic Leadership Succession (DLS)–and connect it to key values of equity-oriented leadership: culture, context, advocacy, and collectivity. We consider practical implications for integrating equity-oriented leadership values with an equity-model of planning, posing new questions for system change and for district leaders interested in continuity of community-engaged leaders in diverse public schools.

Introduction

Public education systems across the United States continue to grapple with chronic leadership turnover, a challenge that is especially acute in under-resourced schools serving historically marginalized communities (Béteille et al., 2012; Henry and Harbatkin, 2019; Levin and Bradley, 2019). In response to this persistent issue, typical approaches to leadership development reflect technocratic frameworks derived from human capital theory and labor market economics. These models emphasize efficiency and organizational stability by advancing individuals through standardized leadership pipelines structured around supply-and-demand logics (Greer and Virick, 2008; Rothwell, 2001; Fusarelli et al., 2018). Within this paradigm, leadership is often treated as a discrete set of competencies held by individuals in formal administrative roles, frequently abstracted from the social, cultural, and political contexts in which leadership actually occurs.

By contrast, the field of community-engaged leadership is anchored in relational, cultural, and sociohistorical logics that elevate the collective wisdom, lived experiences, and assets of communities—particularly those historically excluded from educational decision-making (Yosso, 2005; Green, 2015; Khalifa et al., 2016). This orientation disrupts hierarchical and individualistic leadership logics, instead viewing it as a shared practice embedded in local knowledge, mutual accountability, and a deep commitment to equity (Green, 2017). Distributed leadership frameworks reinforce this view by conceptualizing leadership practice as an interactive and dynamic process that is “stretched over” multiple actors, shaped by context, and responsive to histories of place and power (Diamond, 2013).

However, existing models of succession planning are ill-equipped to support the development, continuity, and thriving of equity-focused, community-engaged leadership. Research shows that schools in under-resourced communities face higher turnover, more difficult working conditions, and intensified policy pressures—factors that likely deplete and deter equity-oriented leaders (Myung et al., 2011; Simon and Johnson, 2015; Horsford et al., 2018). As a result, many school systems’ leadership pipelines may remain misaligned to identify, develop, and support the kind of culturally responsive, equity-oriented leadership needed to advance transformational change, reinforcing cycles of leadership instability and deepening the disconnect between schools and the communities they are meant to serve (Green, 2015; Gooden et al., 2023; Peters et al., 2018).

In this paper, we argue for a reimagining of leadership succession planning—not as a neutral or technical mechanism for talent management, but as a dynamic, context-responsive process that supports the thriving of community-engaged, equity-centered leaders who challenge individualistic and competitive leadership logics. To do so, we expand the Dynamic Leadership Succession (DLS) model presented by Peters et al. (2018) by connecting its core elements—forecasting, sustaining, and planning—to the values, commitments, and practices of equity-oriented leadership frameworks. We begin by outlining traditional accounts of leadership and succession planning which emphasize the importance of ensuring leadership continuity by identifying and preparing individual successors for key roles. We contrast these dominant orientations with perspectives that call for a more holistic approach, where school leaders actively collaborate with local communities, leveraging cultural wealth and addressing equity issues. Distributed leadership frameworks further help us challenge the notion of leadership as an individual trait, emphasizing that leadership practices can be shared among various community members and be deeply informed by local context, history, and power. Through this synthesis, we aim to offer both conceptual clarity and actionable insights for educational leaders, researchers, and policymakers committed to transforming school leadership systems for equity and justice.

Overview of succession planning models

To plan for inevitable leadership turnover and vacancies, scholars argue that districts should engage directly in forms of “succession planning” (e.g., Fusarelli et al., 2018). The idea of succession planning has roots in fields of managerial and business administration, which argue the need for organizations to engage in explicit management and planning for leadership turnover. A definition of succession planning from this field defines it as “a deliberate and systematic effort by an organization to ensure leadership continuity in key positions, retain and develop intellectual and knowledge capital for the future, and encourage individual advancement” (Rothwell, 2001, p. 6). Succession planning, therefore, is a way to ensure organizational stability by keeping leadership positions filled (Ip and Jacobs, 2006). Such views of planning are steeped in traditional ideas of leadership, with a focus on positions, the individuals within those positions, and their cognitive or behavioral traits or characteristics (Diamond and Spillane, 2016).

While often discussed collectively, traditional succession models are not monolithic. Some models focus heavily on strategic workforce planning and risk mitigation—emphasizing pipelines, forecasting retirements, and talent inventories (Achampong, 2010; Rothwell, 2001; Ip and Jacobs, 2006). Others prioritize leadership development, coaching, competency alignment, or socialization processes (Bengtson et al., 2013; Fusarelli et al., 2018). Still others incorporate short-term contingency approaches, such as “emergency succession” pools designed to temporarily stabilize leadership during abrupt transitions (Mooney et al., 2013). These models share a common goal of preserving organizational functionality and continuity, but they can vary in their focus, suggested strategy, and timescale.

These traditional models carry significant limitations. First, they often reproduce ideas of linearity of leadership development, simplifying and misrepresenting the dynamic and multifaceted nature of leadership transitions (Kjellström et al., 2020). Second, the models also tend to focus on individual leaders as the primary actors, backgrounding the importance of collective or democratic approaches to leadership practice or connections to the broader organizational and community contexts (e.g., Garman and Glawe, 2004). Finally, and perhaps most critically, these models are mostly silent about the goals of equity-centered systems change, which may seek to transform existing structures and practices to promote greater equity, and the alternative values and logics new leaders might need to possess (DeMatthews, 2018). These limitations are significant when placed alongside a vision of school systems and school leadership that are deeply connected to, and engaged with, local communities.

In contrast to models that are reactive, individualistic, and role-focused, the DLS model is a more dynamic, human-centered alternative. As outlined in articles by Peters (2011) and Peters et al. (2018), leadership succession is a cyclical process comprising three interdependent sets of actions: forecasting, sustaining, and planning. In this model, succession does not require a one-time response; instead, DLS emphasizes proactive engagement with leadership development across time and context. Forecasting involves identifying future vacancies and preparing internal candidates through talent cultivation. Sustaining focuses on supporting current leaders through mentoring, professional development, and distributed leadership practices that ensure continuity even amidst transitions. Planning requires deliberate strategies to bridge outgoing and incoming leadership—ideally with overlap and collaboration—to avoid disruption and maintain institutional knowledge. Together, these components offer a promising alternative to traditional succession frameworks.

Equity-centered leadership models

To meaningfully reimagine succession planning, we must ask not only how leadership transitions are managed, but what kinds of leadership those systems are designed to sustain. In contexts marked by systemic inequality, succession planning must move beyond logistical management to intentionally cultivate leaders who are deeply committed to equity-oriented practice. Equitable leadership recognizes that mainstream educational policies, practices, and cultures—shaped by dominant ideologies—have historically reproduced or intensified disparities for marginalized students and families (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2017). School leaders play a pivotal role in either reinforcing these normative structures or disrupting them (Gooden et al., 2023). Through intentional preparation, leaders can learn to foster inclusive school environments that affirm the cultural assets, lived experiences, and epistemologies of historically underrepresented communities (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2017; Grooms et al., 2024). Central aspects of equity-oriented leadership include fostering practices that are culturally responsive, community-engaged, socio-politically grounded and advocacy-oriented, and collectively-oriented via distributed leadership.

Culturally responsive leadership

Culturally responsive leaders cultivate asset-based views of the students and families they serve. Culturally responsive education has typically focused on classroom instruction (Gay, 1994; Ladson-Billings, 1995), yet this framework has evolved to include the impact that principals have on the entire school environment, which should also convey responsiveness to the needs of minoritized students (Khalifa et al., 2016). According to Khalifa et al., 2016 culturally responsive school leadership (CRSL) centers inclusion, equity, advocacy and social justice. Specifically, culturally responsive school leaders demonstrate critical self-awareness of his/her values, beliefs, and dispositions when it comes to serving students of color, including articulating anti-racist commitments to educational curriculum and practice (Khalifa et al., 2016). For example, leaders with such commitments are attentive racialized suspension gaps and other forms of exclusionary discipline, as well as racialized access to high-status courses (aka “tracking”). Leaders with such commitments, moreover, are intentional about recruiting, retaining and developing teachers who are also critically self-aware, committed to anti-racist educational practices, and skilled in promoting culturally responsive teaching in their classroom (Khalifa et al., 2016). Generally, this type of leadership involves a deep consideration for non-dominant cultural capital, possessed by students and families of color (Carter, 2005), and what Tara Yosso calls community cultural wealth, defined as an “array of knowledge, skills, abilities, and contacts possessed and utilized by Communities of Color” (2005, p. 77). These assets are particularly important when used by non-dominant groups to survive and resist oppression and inequality.

Community-engaged leadership

Equity-oriented leaders also demonstrate strong commitments to community-engagement. Indeed, there are increasing calls for schools and educational leaders to be more deeply engaged with local communities (Childs et al., 2023; Grooms et al., 2024; Green, 2015). In such visions, school leaders navigate leadership in close relationship with communities that have unique histories, organizational cultures, and ecosystems. The goal of such relationships moves beyond traditional norms that position community members as stakeholders to “inform” or “to be consulted with” about educational decisions that impact their community, toward collaborative and empowering relationships built on reciprocity, mutuality, and shared power in decision-making [International Association for Public Participation [IAPP], 1999]. Community-engaged leaders are intentional about establishing relationships with community partners that allow them to draw on multiple assets and knowledge forms that partners possess for school improvement [Green, 2017; International Association for Public Participation [IAPP], 1999]. Scholars of community-engaged leadership have proposed practical tools for how leaders can span school and community boundaries and foster solidarity with partners, such as “community-based equity audits” (Green, 2017, p. 17), which seek to disrupt deficit views of communities, create inquiry and shared learning experiences by organized leadership teams, and result in collection of relevant data for equity-oriented action (see Green, 2017 for more details). Other studies have emphasized the need for principal preparation programs that foster engagement capacities of future leaders (Lac and Diaz, 2023).

Advocacy and justice-oriented leadership

Advocacy leadership is an equity-oriented framework focused on cultivating leaders who are mindful of, and responsive to, the politics and policy conditions of their school community and its implications for educational equity and justice (Anderson, 2009). Shifts toward high stakes testing and accountability, as well as market-based reforms in recent decades, have emphasized student performance on standardized tests, and choice and competition to incentivize greater performance (Horsford et al., 2018). Leaders of schools who facilitate strong academic gains, relentlessly and narrowly (if not exclusively), are often viewed as effective leaders and as good “managers.” Yet managerialist leaders, even when having more autonomy to pursue ambitious academic goals, work within existing budgetary frameworks which do little to rectify inequities in resources between schools or the concentration of students with special needs in some schools (White and Noble, 2020).

Advocacy leaders, however, resist context-blind approaches to leadership, and thus advocate for the needs of their students in light of resource disparities and policy pressures. For example, advocacy leaders acknowledge that educational needs exist alongside other needs, such as in housing, labor, criminal justice, and other social services (Anderson, 2009). As such, advocacy leaders often seek out and engage in partnerships with community organizations to learn with and from these groups, which are often tied to broader social justice movements spear-headed by grassroots community-based, and multiracial organizations. When connected to a network of advocacy groups, leaders with an advocacy orientation are likely to contextualize school challenges and outcomes within broader community struggles (e.g., gentrification, gun violence, police violence, limited after-school/youth centers, etc.). Moreover, advocacy leaders help to expand narrow policy prescriptions in education (e.g., high-stakes testing, school closure, etc.) and instead weigh school success and student achievement in non-traditional ways, including civic engagement and participatory action projects in the local community.

Shared and distributed leadership

Another body of literature that informs equity-oriented leadership is one that views leadership not as a set of traits embodied by an individual leader within a formal role, but as a set of practices that can be spread across members of the school community (Gronn, 2002; Spillane and Diamond, 2007). According to the analytic framework of distributed leadership, a “constellation of people” can be involved in leadership practice (Diamond, 2013, p. 85), including teachers or on-site specialists (e.g., Timperley, 2005). Here, distributed leadership is an interactive, dynamic phenomenon, involving “leaders,” “followers,” and different elements of their situation. Understanding local context – whether in terms of organizational size, particular content area, design of routines or tools, or setting – all shape how leadership practice unfolds, and to what ends (Diamond, 2013). The context of schools or communities is not “the backdrop” of leadership practice, but an essential element. Recently, there have been calls to develop more contextual notions of distributed leadership, with stronger attention to local place, history, culture, and community (Bolden, 2011; Edwards, 2011). There is a need for conceptualizing the ways in which power and politics shape and are shaped by distributed leadership practices (Lumby, 2013), including how race, gender, class, language and other social identities create or close off opportunities for leadership (Diamond and Spillane, 2016).

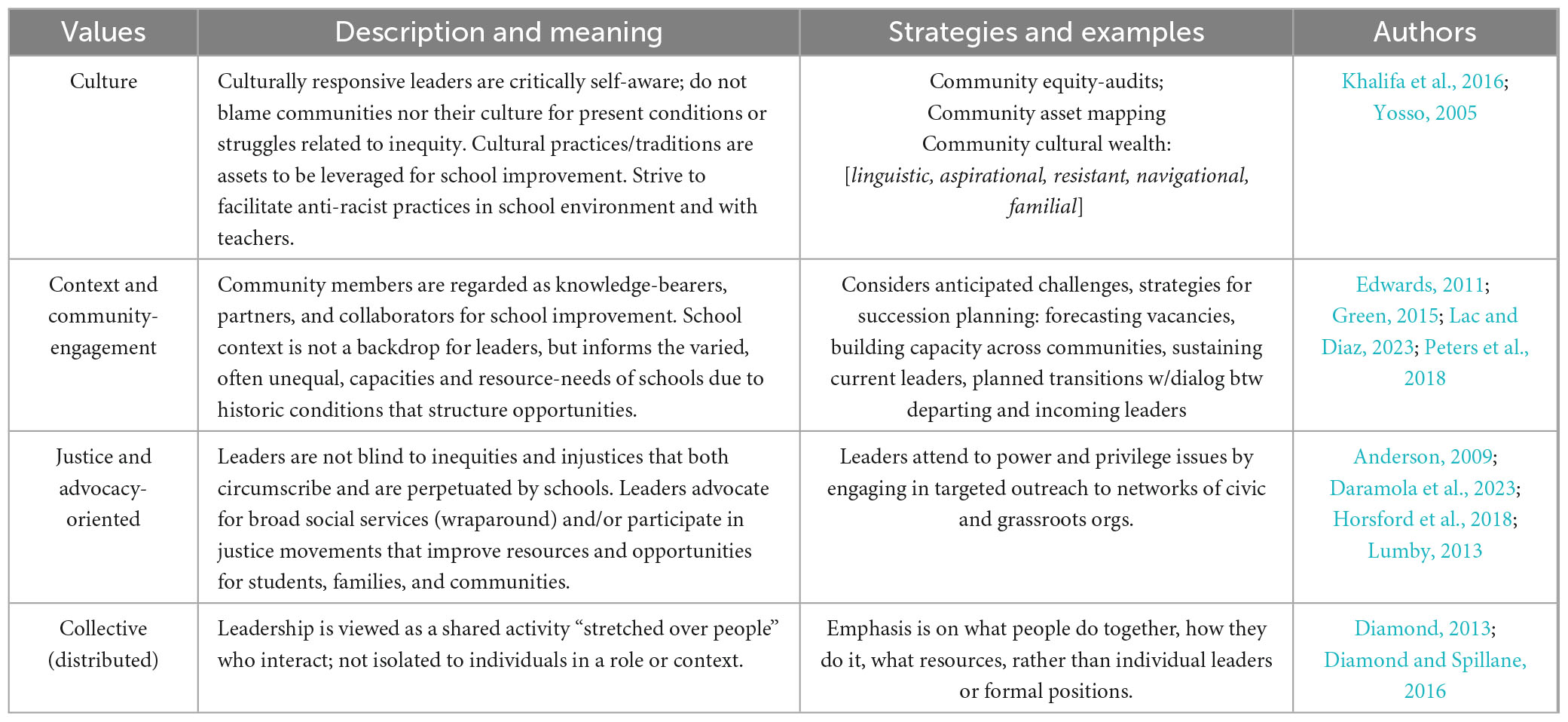

As summarized in Table 1, key takeaways from equity-oriented leadership frameworks include practices that elevate logics of expertise rooted in cultural responsiveness, community-engagement, sociopolitical advocacy, and collective distributed leadership practices. How to plan for the succession and continuity of leaders with these values, amid unequal contexts, requires attention to equity-based planning for equity-oriented leaders.

Expanding dynamic leadership succession to support equity-centered leadership

We return to DLS as a compelling foundation for equity-centered leadership development because of its emphasis on sustained support, internal capacity-building, and intentional, relational transitions. Its cyclical and proactive design allows districts to move beyond reactive, vacancy-based models toward a more transformative approach to leadership succession. This approach is especially critical in urban schools, where leaders in these schools are tasked with providing education circumscribed by enduring inequities in resources, often amid heightened policy pressures related to high-stakes accountability, school choice and competition (Horsford et al., 2018; Myung et al., 2011; Simon and Johnson, 2015). As a result, instability in leadership is not evenly distributed across a school system, and its effects are most acutely felt in schools already facing the greatest challenges (Béteille et al., 2012; Henry and Harbatkin, 2019; Levin and Bradley, 2019). Adapting the DLS model’s three components—forecasting, sustaining, and planning—to advance equity-centered leadership requires retooling each element to reflect the values of equity-centered leadership, including cultural responsiveness, contextual awareness, justice and advocacy, and collective leadership. The adapted model of DLS makes these values of equity-centered leadership central to how leadership can be identified, nurtured, and developed.

To align the DLS model with the core values of equity-centered leadership, one shift lies in how a district might approach forecasting. Traditional forecasting focuses on anticipating leadership vacancies and preparing individuals to step into roles based on managerial readiness. An equity-centered adaptation broadens this view to intentionally identify and cultivate leadership potential from within historically marginalized communities. Such an approach might involve redefining who is seen as “leadership material” by recognizing the cultural wealth, lived experiences, and community-rooted expertise of educators and staff who may not fit dominant leadership norms. Forecasting can also be informed by community voice and equity audits, ensuring leadership pipelines are inclusive and responsive to the cultural and contextual realities of the school’s students and families (Green, 2017).

A second adaptation involves sustaining leaders, particularly those advancing justice-oriented work. In the original DLS model, sustaining focuses on mentoring and professional development to support leadership continuity. To center equity, this component could be expanded to include anti-racist, culturally responsive mentoring that acknowledges the emotional and political labor equity leaders often face, particularly leaders of color (Ishimaru, 2023). Sustaining leadership also means shifting away from an individualistic model to one that is collective and distributed, creating collaborative spaces for shared leadership models or peer accountability. Professional learning communities and leadership networks could be rooted in advocacy, wellness, and support systems that buffer against burnout and institutional resistance. This approach ensures that equity work is not only initiated but protected and sustained across time.

Finally, planning in an equity-centered DLS model can involve participatory and community-responsive transitions. Traditional succession planning tends to be an internal administrative process, often excluding the voices of students, families, and educators most impacted by leadership changes. An equity-minded approach might involve these stakeholders in decision-making, ensuring transparency and alignment with community values. Transitions could include structured overlap between outgoing and incoming leaders, with deliberate efforts to sustain relationships, practices, and initiatives that advance equity. Rather than focusing solely on maintaining operational continuity, equity-centered planning prioritizes cultural and justice continuity—embedding inclusive leadership practices into the school’s collective identity so they endure beyond any single leader.

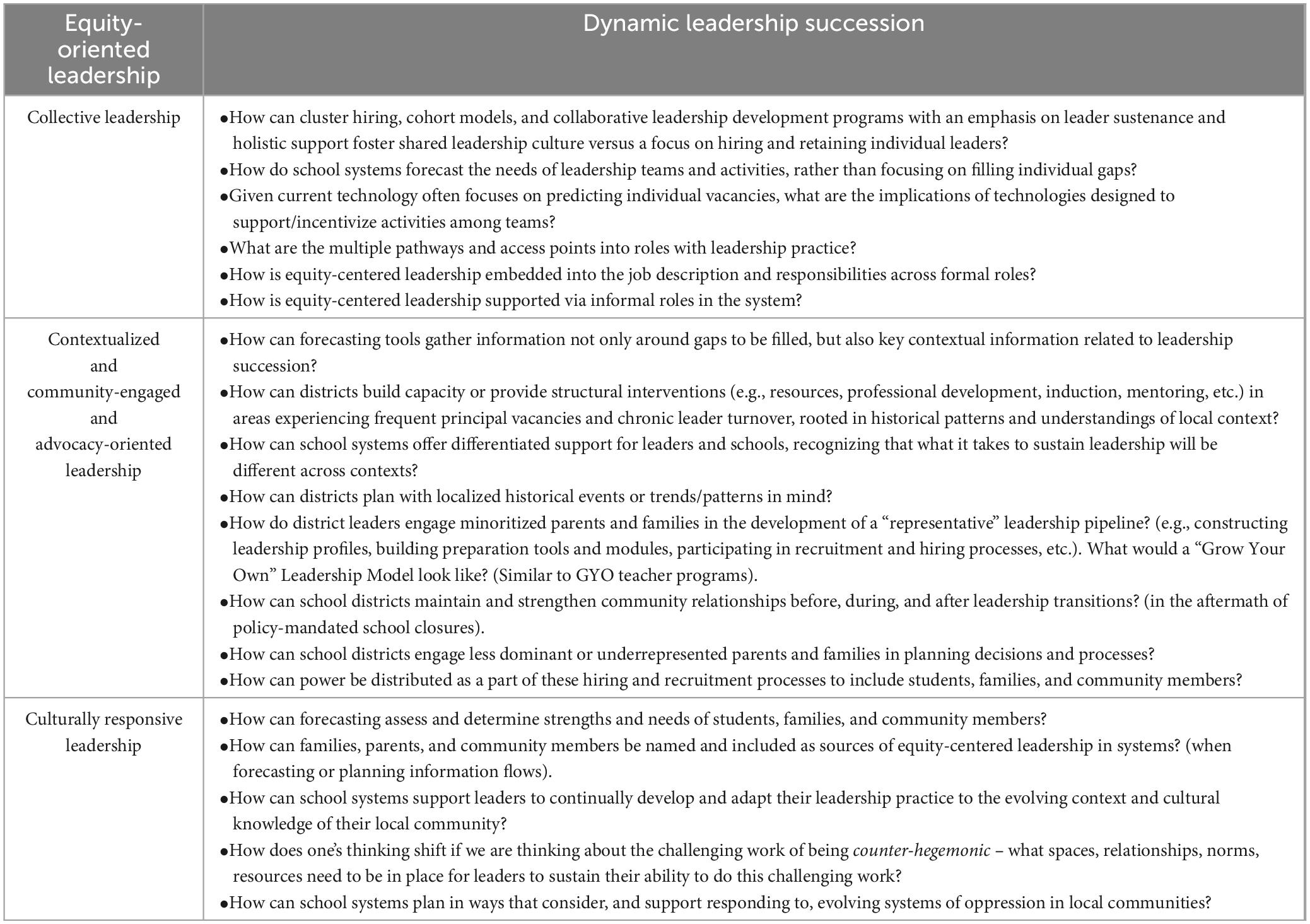

Marrying together the DLS model with ideas from equity-oriented leadership models suggests new questions around what it means to anticipate and respond to inevitable transitions in ways that actively advance equity-centered leadership. In other words, we ask: what might it mean to plan for and support inevitable leadership vacancies in a way that is consistent with visions of equity-centered leadership? To support this reorientation, Table 2 offers generative questions that are intended to prompt robust and expansive designs, structural considerations, and future research.

Reimagining systems to support dynamic and equitable leadership succession

We emphasize that each of the questions that emerged for leaders about equity-oriented planning requires broader changes to systems and structures of support related to leadership. As is evident in the questions proposed in Table 2, supporting DLS for community-engaged leaders will require changes and transformations in the roles, processes, and routines that connect to leadership development and succession in school systems. For instance, take the first question in Table 2, we identify three possible areas of broader organizational infrastructure redesign that would likely be implicated by a shift toward DLS in a large school system to support the leadership development of equity centered leaders as envisioned above, noting there are surely many other routines, policies, events, tools, and roles that would need to be redesigned as well.

First, the shift toward equity-centered DLS will inevitably require not only a new vision for leadership in districts, but new opportunities for learning to help people within systems reconceptualize leadership practice as something that is collective, contextualized, advocacy-oriented and sociopolitical, and cultural (Honig and Honsa, 2020). Learning supports must be ongoing to support what will be a gradual and messy process of “unlearning” past ways of thinking about school leadership in individualized terms, and of developing new, responsive approaches to understanding this work at sites of cultural affirmation, community mobilization, and transformative racial equity (Baxley, 2024). To this end, professional development opportunities may need to offer opportunities for critical self-reflection; opportunities for active learning in connection to day-to-day work at schools and within their communities; coaching, support and mentorship; and fostering peer-to-peer relationships (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2014).

Second, transforming the view of equity-centered leadership at school sites will likely require new ideas for the role of principal supervisors, the individuals who evaluate, mentor, and coach principals in school systems. In most districts, principal supervisors have historically focused on monitoring, evaluating, and providing logistical support for individual principal leaders. Districts may need to think about how much, and in what ways, principal supervisors would work to support individual principals versus facilitate learning for teams who are engaged in equity-centered leadership at school sites to advance a vision of collective leadership. Principal supervisors will also need to make sense of, and differentiate support for, their work with individuals or groups of leaders who have unique needs, strengths, past experiences, and social identities, all contextualized within specific school communities.

Third, pursuing this vision of equity-centered DLS will involve a coherent approach that can leverage the expertise and energy of many people and departments within the district central office. However, a very typical challenge of work in this space is siloing, where departments focus on their own tasks, causing important perspectives, information, and resources to remain isolated in individual departments and working against the effort for equity-centered leadership succession. For instance, human resource departments are typically tasked with advertising positions and filling them with eligible candidates. The shift toward equity-centered DLS will likely require greater communication and coordination around the current leadership assets (i.e., instructional leadership team, community council, etc.) at a site and broader information around specific school-community contexts. It may also involve redesigning processes and routines for cross-departmental work across HR, leadership development, and school supervision, among others.

Contributions and conclusion

This literature review that combined frameworks of equity-based planning and equity-oriented leadership informs, challenges, and improves traditional approaches to succession planning which are often myopic and culturally inadequate for retaining and sustaining a thriving cadre of diverse leaders for the country’s public schools. It also represents a potential way to reimagine succession planning rooted in the rich literature and legacies of historic and contemporary BIPOC leaders and their leadership practices that often work in solidarity with their community’s struggles for critical education, justice, and equity. This reimagined framework for principal succession planning bridges traditional human capital approaches with community-engaged, equity-oriented perspectives on school leadership. By integrating ideas of continuity with the cultural wealth and collective expertise found within communities of color, school systems can disrupt conventional succession models that often prioritize individual advancement and efficiency. Building on Peters et al. (2018) dynamic succession planning model, this lens emphasizes distributed leadership and collective responsibility, fostering a leadership approach that is deeply connected to the realities facing school leaders, as well as the unique histories, relationships, and cultural logics within the diverse communities they serve. By prioritizing local knowledge, cultural assets, and collaborative leadership practice, the framework offers a path toward a more humane, culturally responsive, and equitable plan for sustained school leadership. Ultimately, this approach envisions succession planning as a means of continuously cultivating leaders who are not only effective administrators but also stewards of the communities they serve, reinforcing the school’s role as a hub of cultural, social, and relational capital.

Author contributions

TW: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MO: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AR: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. CF: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This publication is based on research commissioned and funded by the Wallace Foundation as part of its mission to support and share effective ideas and practices.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Achampong, F. K. (2010). Integrating risk management and strategic planning. Plann. High. Educ. 38, 22–27.

Anderson, G. (2009). Advocacy leadership: Toward a post-reform agenda in education. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

Baxley, G. (2024). Neoliberalism and the complexities of conceptualizing community school policy for racial equity. Educ. Pol. 39, 1044–1074. doi: 10.1177/08959048241278294

Bengtson, E., Zepeda, S. J., and Parylo, O. (2013). School systems’ practices of controlling socialization during principal succession: Looking through the lens of an organizational socialization theory. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 41, 143–164. doi: 10.1177/1741143212468344

Béteille, T., Kalogrides, D., and Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Soc. Sci. Res. 41, 904–919. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.03.003

Bolden, R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: A review of theory and research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 13, 251–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x

Carter, P. L. (2005). Keepin’ it real: School success beyond Black and White. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Childs, J., Farrell, C., Grooms, A., Peters-Hawkins, A., Martinez, E., White, T., et al. (2023). Educational equity and the logics of COVID-19: Informing school leadership practices in a new period of democratic education. Peabody J. Educ. 98, 577–589. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2023.2265774

Daramola, E. J., Marsh, J. A., and Allbright, T. N. (2023). Advancing or inhibiting equity: The role of racism in the implementation of a community engagement policy. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 22, 787–810. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2022.2066546

DeMatthews, D. (2018). Community-Engaged leadership for social justice: A critical approach in urban schools. New York, NY: Routledge.

Diamond, J. B. (2013). “Distributed leadership: Examining issues of race, power, and inequality,” in Handbook of research on educational leadership for equity and diversity, eds L. C. Tillman and J. J. Scheurich (New York, NY: Routledge).

Diamond, J. B., and Spillane, J. P. (2016). School leadership and management from a distributed perspective: A 2016 retrospective and prospective. Manage. Educ. 30, 147–154. doi: 10.1177/0892020616665938

Edwards, G. (2011). Concepts of community: A framework for contextualizing distributed leadership. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 13, 301–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00309.x

Fusarelli, B. C., Fusarelli, L. D., and Riddick, F. (2018). Planning for the future: Leadership development and succession planning in education. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 13, 326–350. doi: 10.1177/1942775118771671

Galloway, M. K., and Ishimaru, A. M. (2017). Equitable leadership on the ground: Converging on high-leverage practices. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 25:2. doi: 10.14507/epaa.25.2205

Garman, A. N., and Glawe, J. (2004). Succession planning. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 56, 119–128. doi: 10.1037/1061-4087.56.2.119

Gooden, M. A., Khalifa, M., Arnold, N. W., Brown, K. D., Meyers, C. V., and Welsh, R. O. (2023). A culturally responsive school leadership approach to developing equity-centered principals: considerations for principal pipelines. Available online at: https://wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/Culturally-responsive-school-leadership-approach_06.29.FINALforposting.pdf

Green, T. (2017). Community-based equity audits: A practical approach for educational leaders to support equitable community-school improvements. Educ. Admin. Quar. 53, 3–39. doi: 10.1177/0013161X16672513

Green, T. L. (2015). Leading for urban school reform and community development. Educ. Admin. Quar. 51, 679–711. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15577694

Greer, C. R., and Virick, M. (2008). Diverse succession planning: Lessons from the industry leaders. Hum. Resource Manag. 47, 351–367. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20216

Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. Leadersh. Quar. 13, 423–451. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00120-0

Grooms, A., White, T., Peters-Hawkins, A., Childs, J., Farrell, C., Martinez, E., et al. (2024). Equity as a crucial component of leadership preparation and practice, Vol. 97. The Clearing House, 8–15. doi: 10.1080/00098655.2023.2286373

Henry, G. T., and Harbatkin, E. (2019). Turnover at the Top: Estimating the effects of principal turnover on student, teacher, and school outcomes. Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Honig, M. I., and Honsa, A. (2020). Systems-focused equity leadership learning: Shifting practice through practice. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 15, 192–209. doi: 10.1177/1942775120936303

Horsford, S. D., Scott, J. T., and Anderson, G. L. (2018). “The “new professional”: Teaching and leading under new public management,” in The politics of education policy in an era of inequality: Possibilities for democratic schooling, eds S. Horsford, J. Scott, and G. Anderson (New York, NY: Routledge).

International Association for Public Participation [IAPP] (1999). IAP2 spectrum of public participation. Portsmouth, NH: IAPP.

Ip, B., and Jacobs, G. (2006). Business succession planning: A review of the evidence. J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 13, 326–350. doi: 10.1108/14626000610680235

Ishimaru, A. (2023). Female equity leaders of color are undervalued and undercut: 3 ways to set Black women and other women of color up for success in district equity leadership. Education Week.

Ishimaru, A. M., and Galloway, M. K. (2014). Beyond individual effectiveness: Conceptualizing organizational leadership for equity. Leadersh. Pol. Sch. 13, 93–146. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2014.890733

Khalifa, M. A., Gooden, M. A., and Davis, J. E. (2016). Culturally responsive school leadership: A synthesis of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 1272–1311. doi: 10.3102/0034654316630383

Kjellström, S., Stålne, K., and Törnblom, O. (2020). Six ways of understanding leadership development: An exploration of increasing complexity. Leadership 16, 434–460. doi: 10.1177/1742715020926731

Lac, V. T., and Diaz, C. (2023). Community-based educational leadership in principal preparation: A comparative case study of aspiring Latina leaders. Educ. Urban Soc. 55, 643–673. doi: 10.1177/00131245221092743

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32, 465–491. doi: 10.3102/00028312032003465

Levin, S., and Bradley, K. (2019). Understanding and addressing principal turnover: A review of the research. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Lumby, J. (2013). Distributed leadership: The uses and abuses of power. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 41, 581–597. doi: 10.1177/1741143213489288

Mooney, C. H., Semandi, M., and Kesner, I. (2013). Interim succession: Temporary leadership in the midst of the perfect storm. Bus. Horizons 56, 621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2013.05.005

Myung, J., Loeb, S., and Horng, E. (2011). Tapping the principal pipeline: Identifying talent for future school leadership in the absence of formal succession management programs. Educ. Admin. Quar. 47, 695–727. doi: 10.1177/0013161X11406112

Peters, A. L. (2011). (Un)Planned failure: Unsuccessful succession planning in an urban district. J. Sch. Leadersh. 21, 64–86. doi: 10.1177/105268461102100104

Peters, A. L., Reed, L. C., and Kingsberry, F. (2018). Dynamic leadership succession: Strengthening urban principal succession planning. Urban Educ. 53, 26–54. doi: 10.1177/0042085916682575

Rothwell, W. (2001). Effective succession planning: Ensuring leadership continuity and building talent from within, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: AMACOM.

Simon, N., and Johnson, S. M. (2015). Teacher turnover in high-poverty schools: What we know and can do. Teach. Coll. Record 117, 1–36. doi: 10.1177/016146811511700305

Spillane, J. P., and Diamond, J. B. (2007). Distributed leadership in practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Timperley, H. (2005). Distributed leadership: Developing theory from practice. J. Curriculum Stud. 37, 395–420. doi: 10.1080/00220270500038545

White, T., and Noble, A. (2020). Rethinking school autonomy: strengths and limitations of autonomy-based school improvement plans in contexts of widening racial inequality. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Available online at: https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/autonomy

Keywords: succession planning, community-engaged leadership, culturally responsive leadership, advocacy leadership, equity-oriented leadership

Citation: White T, Obregon M, Resnick AF and Farrell C (2025) Succession planning for community-engaged leaders: culture, context and continuity in equity-oriented leadership. Front. Educ. 10:1527211. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1527211

Received: 13 November 2024; Accepted: 17 June 2025;

Published: 07 August 2025.

Edited by:

Ain Grooms, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesReviewed by:

Colin Evers, University of New South Wales, AustraliaElisabeth Kim, California State University, Monterey Bay, United States

Copyright © 2025 White, Obregon, Resnick and Farrell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Terrenda White, dGVycmVuZGEud2hpdGVAY29sb3JhZG8uZWR1

Terrenda White

Terrenda White Monica Obregon

Monica Obregon Alison Fox Resnick

Alison Fox Resnick Caitlin Farrell

Caitlin Farrell