- 1School of Electrical Engineering and Intellegentization, Dongguan University of Technology, Dongguan, China

- 2Sheffield Institute of Social Science, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom

- 3School of Education, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States

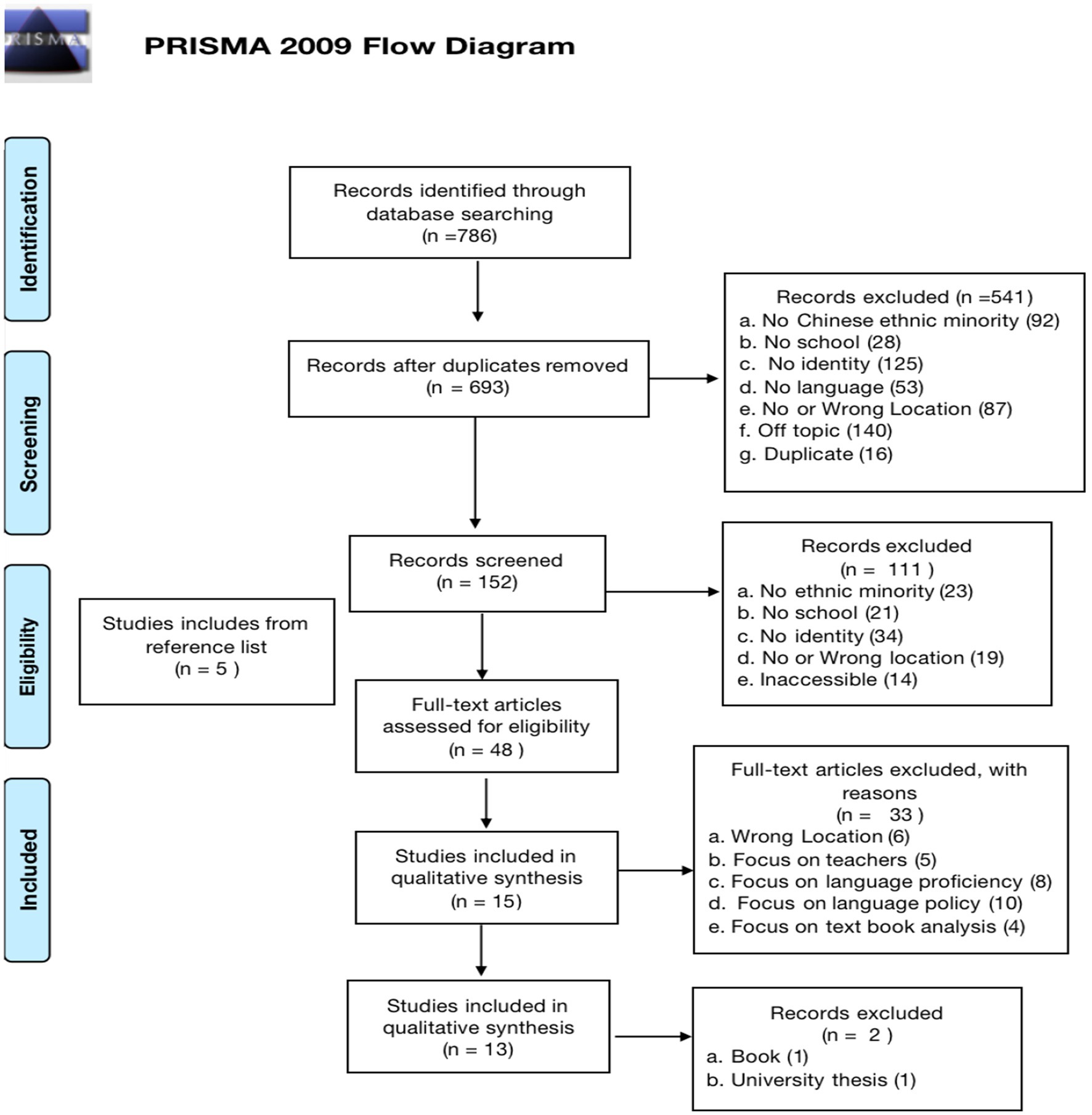

This systematic review investigates existing research on how ethnic minority students in China construct their identities within the “Inland Ban (Inland Class)1” at various educational levels. A structured search was conducted exclusively on English-language journals using the Web of Science (WoS) database from the Sheffield Hallam University Library between July and August 2023. A total of 693 articles were initially identified, and after rigorous screening, 13 studies met the inclusion criteria. Studies were selected based on their focus on Chinese ethnic minorities, identity construction, and educational experiences in the inland class between 2000 and 2023. Exclusion criteria included studies not focused on ethnic minority students, those examining teachers instead of students, research on language policies rather than identity, and inaccessible full texts. Each selected study was analyzed for its focus on ethnic groups and languages, sample size, educational level, location of the host school, and research methodology. While this study primarily examines identity construction, it acknowledges that pedagogical methods, curriculum content, and language policies in Neidi Ban schools may also influence students’ self-perceptions and national identity formation. The review highlights key factors shaping identity construction, including linguistic challenges, cultural disparities, and institutional practices. A post-structuralist lens explores how identities are shaped within hierarchical power structures, particularly in Mandarin-dominant environments. Additionally, Bourdieu’s theories of cultural, social, and symbolic capital provide a framework for understanding how minority students adapt and renegotiate their identities in Han-centric educational settings.

Introduction

An expanding body of research across linguistics, education, and sociology explores how individuals reconstruct and renegotiate their identities while acquiring new languages and engaging with local communities (Norton, 1997; Martin, 2009). Using the United Kingdom as an example of an “inner-circle” nation—where English serves as the dominant and widely accepted language (Kachru, 1985)—post-war migration has been shaped by factors such as economic rebuilding (Martin, 2009), political upheaval, and ecological crises (Edwards, 2008). While much of the existing European-focused scholarship concentrates on refugees and asylum seekers from varied geopolitical regions (Edwards, 2008), migration patterns within China reveal a different trajectory.

In the Chinese context, internal migration involves large-scale movements from rural to urban areas and from the western regions to the economically prosperous eastern coast. The Chinese government has actively promoted internal migration as a strategy for economic development and fostering national cohesion (Postiglione and Li, 2009). While Postiglione and Li (2009) argues that such programs improve educational access and bridge development gaps, this view has been critiqued by Vickers (2014), who contends that minority education in China functions less as inclusion and more as part of a state-led civilizing mission aimed at ideological assimilation. This unique internal migration pattern, within the framework of a multilingual and multicultural nation, underscores the importance of examining the interplay between heritage languages, ethnic identities, and cultural practices (Guo and Gu, 2016).

Ethnic minority populations in China have become a significant component of internal migration, highlighting the complexities and tensions within the country’s multicultural framework (Gao, 2016). “Ethnic minorities” in the Chinese context refers to the 55 officially recognized groups, including Mongolians, Hui, Zhuang, Yi, and Koreans, according to the 2020 Seventh National Census, together account for 125.47 million people, or 8.89% of the national population (National Bureau of Statistics, 2002). These groups are predominantly concentrated in the western regions of the country (Liu and Edwards, 2017). While the Hui and Manchu ethnicities predominantly speak Mandarin, most other groups retain their native languages, with 30 of these languages having written forms (Zuo, 2007). Since the 1980s, rural populations, including ethnic minorities, have increasingly migrated to urban areas in search of better employment opportunities (Pieke and Barabantseva, 2012) and access to quality education (Department of Education, 2000). Notable initiatives include the establishment of specialized Tibetan education programs in major cities like Beijing, Chengdu, and Shanghai beginning in 1984. Educational policies for ethnic minorities in China emphasize cultural diversity while simultaneously promoting national unity, a dual focus that reflects the state’s broader policy objectives (Gao, 2016). However, this unity-oriented approach often leads to significant exposure to Han culture, contributing to a sense of ambivalence and complexity in the identity development of ethnic minority students.

Within the country, there is a multiplicity of ethnic groups and languages (see at Figure 1), and the eastern part of the country (non-ethnic minority concentrated areas) has a relatively developed economy. Due to economic reasons and education policies, there is a movement of ethnic minorities leaving ethnic minority areas to work and receive education in eastern coastal areas, thus forming a special group of internal migrants. Whether it is ethnic minority children who move to the eastern regions with their parents or ethnic minority students who respond to policies and take the initiative to enter high schools and universities in the eastern regions, they are all influenced by Chinese-dominated schools and objectively face the phenomenon of cultural adaptation and identity reconstruction.

This review centres on the identity construction of minority students, drawing on insights from post-structuralist theory (Block, 2009; Phillips, 2007). Post-structuralism provides a lens to explore how identities are shaped and reshaped within systems of power and dominance (Mason and Clark, 2010), particularly in environments where Mandarin functions as a tool of “knowledge capitalism” (Bourdieu, 2018). Bourdieu’s framework of capital—encompassing cultural, social, and symbolic dimensions—offers a valuable approach for examining how minority students navigate and reconstruct their identities within hierarchical, non-autonomous educational institutions (Bourdieu, 2018). Traditionally, identity has been linked to a specific language or culture, often considered an inherent and fixed characteristic of an individual. However, post-structuralist perspectives challenge this view, arguing that language does not merely reflect reality but actively constructs it. This paradigm shift has led to an understanding of identity as dynamic, multifaceted, and relational, and provides various theoretical frameworks to apply to minority groups whose language and culture differ from the mainstream one. By framing language acquisition as a process of identity negotiation, Cummins (2001) emphasizes the importance of “additive bilingualism” (where the second language is added without replacing the first language) as a powerful counter-narrative to “subtractive bilingualism.” However, this is an ideal state that is difficult to achieve. Rooted in the concept of “subjectivity” (Weedon, 1997), identity is redefined as “the way individuals perceive their relationship with the world, how this relationship evolves over time and across different contexts, and how they envision possibilities for their future” (Norton, 2013, p. 4). Norton also reveals that language learning is a process in which the learner invests in his or her identity, and the learner redefines himself or herself through language learning. Compared with international theories, Chinese scholars primarily focus on bilingual education, cultural identity, and the academic achievement and identity crisis of minority students.

This review focuses on the role of schools across various educational levels in shaping the identities of ethnic minority students. In schools located in eastern coastal cities of China, minority students interact with local peers and educators while engaging with standardized Mandarin-based curricula. This dialogical process of identity construction often hinges on linguistic and cultural differences encountered in school interactions (Dong, 2009). Martin (2009) highlights the potential for schools to serve as “safe” spaces for students from multilingual and multicultural backgrounds. However, his critique of British higher education underscores the insufficient attention given to the linguistic diversity and lived experiences of minority students. Through the narratives of four multilingual graduates, Martin illustrates how British universities often replicate the dominant monolingual culture of broader society, leading to the marginalization of multilingual students within academic communities. This neglect not only challenges their academic engagement but also exacerbates struggles with ethnic identity. His findings raise critical questions that resonate deeply with the issues explored in this review.

“Does widening participation in higher education mean that such education is participatory and inclusive, or is university education within the widening participation agenda a sort of mono-cultural straitjacket, suffering from a myopic monolingual malaise? Is the university a place where students can negotiate languages and identities, or do universities simply fail to recognize the fluidity of linguistic and cultural repertoires?” (Martin, 2009, p.17).

Unsurprisingly, schools play a pivotal role in shaping students’ sociocultural identities. Considering this connection between education and identity construction, a critical question emerges: “How does internal migration impact the identity construction of ethnic minority students in schools?” Previous research has underscored several issues faced by host schools and the challenges encountered by migrant students. These include, but are not limited to, the disregard for minority students’ linguistic abilities, perceptions of minority languages as obstacles, and experiences of social exclusion. Such challenges can have far-reaching consequences, including high dropout rates (Minhui, 2007), poor academic achievement (Sleeter and Carmona, 2017), and ambiguity in the development of a clear and cohesive identity.

The primary objective of this paper is to systematically review recent studies to identify the challenges faced by ethnic minority students concerning language, culture, and schooling, as well as to uncover knowledge gaps in this field. The research question guiding this study is: “What does the existing literature reveal about the relationship between identity construction among Chinese ethnic minority students and schools following migration?” The first section provides an overview of key terms and government policies related to minority education in China. The second section details the methodology and procedures employed in this review, including the processes of searching, screening, and analyzing the relevant literature. This section also presents the results, offering a comprehensive summary of the included studies and examining factors influencing identity construction among minority students. Finally, the third section discusses the findings in depth, highlighting three key themes derived from the reviewed literature and concluding with insights and implications for future research and policy development.

Conceptualizing identity in this study

Identity is a fluid and multifaceted construct that is influenced by language, culture, and social structures (Weedon, 1997; Norton, 2013). Drawing from post-structuralist perspectives, this study understands identity as dynamic and relational, continuously shaped by interactions within educational and societal contexts (Block, 2009; Bourdieu, 1991). Specifically, in the Chinese context, identity construction is often navigated between ethnic heritage and national belonging, which requires a nuanced discussion of ethnic identity, Chinese identity, and Chinese ethnic identity. Ethnic Identity refers to an individual’s identification with their specific ethnic group (e.g., Tibetan, Uyghur, Hui, or Zhuang), often shaped by language, cultural practices, and group membership (Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Phinney, 1990). This identity is frequently reinforced through the preservation of heritage languages and community traditions.

Chinese Identity (Zhonghua Minzu Identity) reflects a broader national identity, which is promoted as a unifying framework within China’s political discourse. The concept of Zhonghua Minzu (中华民族), often translated as a “Chinese national race (Han-centric identity)” encompasses all officially recognized ethnic groups under a national framework (Mackerras, 1994). While this notion intends to foster unity, it may also impose a Han-centric lens that complicates how minority students negotiate their dual allegiances to their ethnic heritage and national belonging (Gao, 2016). Chu (2018) argues that Chinese elementary textbooks have increasingly presented minzu identities within a homogenizing discourse, framing all ethnic groups as harmonious components of the overarching Zhonghua minzu. This representation downplays cultural and political differences among ethnic minorities, and instead promotes a singular national identity rooted in Han cultural norms. Through textbook narratives, ethnic minority identities are symbolically included, but their distinctiveness is subordinated to the unity and supremacy of the Chinese nation. Chu’s work exposes how educational discourse is mobilized to naturalize political unity and cultural integration, contributing to the broader ideological agenda of constructing loyalty to the state through carefully curated representations of diversity.

Chinese Ethnic Identity, as used in this study, represents the interplay between ethnic identity and national identity—how minority students construct their identities within the broader Chinese socio-political context. It examines how ethnic minorities reconcile their heritage identities (e.g., Uyghur, Tibetan) with the overarching narrative of national unity (Guo and Gu, 2016). This process is particularly visible in Mandarin-based schooling environments, where minority students must navigate between linguistic assimilation, cultural preservation, and social inclusion.

This study employs Bourdieu’s concept of cultural, social, and symbolic capital to analyze how minority students adapt, resist, or redefine their identities within Han-dominated educational settings. Additionally, Norton’s (1997) concept of identity as investment is relevant in understanding how ethnic minority students engage with Mandarin and Han-centric curricula while negotiating their cultural positions. By adopting this framework, this study does not treat ethnic identity, Chinese identity, and Chinese ethnic identity as static but rather as intersecting and evolving constructs, shaped by school policies, peer interactions, and broader socio-political discourses.

Terminology and government policies on minority languages and education

Before examining the Chinese government’s strategies concerning minority languages and education, it is important to first clarify key terminology frequently used in policy discussions. Prior to the 1980s, Chinese ethnographic studies predominantly followed a positivist approach, emphasizing material aspects of ethnic culture such as cuisine, clothing, and music. This often resulted in stereotypical portrayals of ethnic minorities as being inherently skilled in singing and dancing, both in textbooks and social media (Kayongo-Male and Lee, 2004; Lin and Jackson, 2022). Yi (2008) Cultural Exclusion in China provides a critical foundation for understanding how cultural and linguistic diversity is subordinated to a state-driven agenda of national unity. This is particularly evident in programs such as Neidi Ban, where minority students are relocated to inland Han-dominant regions under the guise of educational opportunity, yet often experience identity dislocation and marginalization. Recent studies (e.g., Vickers, 2014; Yan and Vickers, 2019, 2024) further reinforce that the current educational model prioritizes political loyalty and linguistic uniformity over multicultural inclusion.

The term “Minzu” refers to the 56 officially recognized nationalities in China, while “Shaoshu Minzu” specifically denotes the 55 ethnic minority groups identified since 1954. A related term, “Ronghe” (meaning “fusion”), frequently appears in political documents to advocate for the harmonious coexistence of diverse ethnic groups. However, critics argue that “Ronghe” may contribute to the erosion of minority languages, cultures, and traditional knowledge (Mackerras, 1994; Yan, 2018). The concept of “Shaoshu Minzu Zizhiqu” (minority autonomous regions) represents geographical and administrative areas where ethnic minorities are granted the power to exercise autonomy (The State Council Information Office of China, 2005). However, in China’s “autonomous regions,” ethnic minority groups face different types of governance. One significant change in recent years has been the sharp retreat of mother-tongue education, with the few courses teaching has been replaced from minority languages to in favor of Mandarin instruction. In Tibet, primary education is rapidly shifting from Tibetan to Mandarin, with Tibetan now taught only as a second-language subject (Vickers, 2014). Similarly, in Xinjiang, policies such as the 2017 “Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Minority Pre-school and Primary and Secondary Bilingual Education Development Plan (2010–2020)” mandate Mandarin instruction from kindergarten through middle school, effectively phasing out instruction in Uyghur by 2020 (Zhang and Adamson, 2023). The term “Han” is multifaceted and contested, encompassing linguistic, cultural, and political dimensions. While it commonly refers to speakers of Mandarin (China’s official language) and the ethnic majority—who make up over 90% of the population—scholars have critiqued the term as overly homogenizing. As highlighted in Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China’s Majority (Mullaney et al., 2012), “Han” identity has been historically constructed and is neither fixed nor monolithic, masking internal regional, class, and cultural differences. In this review, areas predominantly inhabited by Han-identifying communities and characterized by strong economic development are described using terms such as eastern coastal cities (Wang, 2011), inland cities (Guo and Gu, 2018a), interior cities (Wang et al., 2019), or non-autonomous regions—a contrast to officially designated minority autonomous areas.

Neidi ban (inland class)

Neidi Ban follow a standardized national curriculum, which often prioritizes Mandarin instruction and Han-centric historical narratives (Grose, 2015). This program offers primary-level education that aims to serve minorities from Xinjiang, Xizang (Tibet) and Inner Mongolia, which is a similar program to junior-level education domestically named “Neigao Ban.” Teaching methodologies, such as rote memorization and uniform national textbooks, can significantly influence ethnic minority students’ self-perceptions. While these programs aim to provide educational opportunities and social mobility, they may also contribute to an assimilationist model of education by minimizing the visibility of minority languages and cultural traditions (Miaoyan and Dunzhu, 2015; Sun et al., 2024). This study acknowledges that educational structures play a critical role in shaping how students understand their identities, though its primary focus remains on student narratives of self-construction rather than a curriculum-based analysis.

The university-level programs were named “Xinjiang Ban,” “Zangzu Ban (Tibet)” or “Preparatory course for ethnic minorities.” This program has only targeted limited minority regions (Grose, 2010; Liu, 2023). Both Neidi Ban and university-level ethnic minority programs share the core purpose of integrating minority students into Han-majority educational environments under the broader national goal of promoting political unity and social cohesion. Like Neidi Ban, which places high school students from regions like Xinjiang and Tibet into boarding schools in inland Han-majority provinces, programs such as the Xinjiang Ban and Zangzu Ban relocate minority students to Mandarin-speaking, Han-dominant university settings, often requiring them to complete preparatory courses to adjust linguistically and ideologically (Han and Cassels Johnson, 2021).

Historical and horizontal perspectives on minority language policies

From a historical standpoint, Chinese government policies on minority languages have evolved through several phases. In the early 1950s, policies supported minority languages; these shifted to suppression during the 1960s, followed by a gradual move toward inclusive approaches from the 1970s onward (Wang and Phillion, 2009). Since the 1980s, China’s education reforms have shifted from a relatively inclusive and multicultural approach, which highlighted ethnic diversity in curricula, to a more assimilationist model from the 1990s onward (Yan and Vickers, 2019). Since 2000 onwards, the Xinjiang Boarding Classes (Neidi Xinjiang Gaoxuexiao Ban) were established in various eastern Chinese cities to provide high school education for students from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Chen, 2006). Driven by the Patriotic Education Campaign, by the 2020s, educational discourse reflects a tension between promoting ethnic unity and acknowledging cultural diversity (Yan and Vickers, 2019, 2024). Horizontally, educational policies for ethnic minorities are typically divided into those addressing autonomous areas and those targeting minorities migrating outside these regions. This study focuses specifically on minority students living and studying in non-autonomous regions, analyzing policies that significantly impact their educational and identity construction processes. The key policies affecting minority students in non-Autonomous regions have been categorized by:

Promotion of mandarin in public schools

Since 1956, Mandarin has been promoted as the primary language of instruction in public schools outside minority autonomous areas (The State Council of China, 1956). Minority students in non-autonomous schools are typically taught through a monolingual Mandarin curriculum, supplemented by English instruction.

Minzu (ethnic) classes in developed cities

Initiatives such as the Xinjiang (Uyghur) High School Classes in Mainland China Policy (Department of Education, 2000) provide financial support for Uyghur students to attend secondary schools in major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Similarly, Tibetan students are encouraged to pursue education in more developed urban centers (Department of Education, 1985).

Higher education pathways for minority students

Ethnic minority students have the option to enroll in one of 15 Minzu universities/institutes or public universities located in non-autonomous regions, such as Beijing or Wuhan (Zhang and Archer, 2024). Multiple pathways for the college entrance examination exist, including “Min Kao Min” (testing in minority languages) and “Min Kao Han” (testing in Mandarin) (Tsung and Clarke, 2010). Unlike “Min Kao Han,” students continue further education at the university by the pathway “Min Kao Min” in China, where access to science and technology fields through minority-language instruction is highly restricted (Yan and Vickers, 2024). This is due to resource limitations, language policy, and the alignment of these programs with political and cultural objectives. The system, while aimed at inclusion, tends to reinforce segregation and limit minority students’ academic and professional trajectories.

These language policies together create a complex landscape for the identity construction of minority students in non-autonomous regions, shaping the language experience and constructing the identity of minority students in non-autonomous regions. These policies promote Mandarin as the dominant language, encourage ethnic minority students to study in economically developed cities, and provide diverse opportunities to enter higher education (Xue and Li, 2020). The use of education-based preferential policies plays a significant role in advancing and stabilizing relationships among ethnic groups (Chen, 2008). The political nature of minority education in China is a crucial dimension that shapes both policy design and student experience and must be understood within the broader context of state efforts to promote national unity. While framed as an opportunity for educational advancement, such initiatives are deeply political, functioning as instruments of ideological integration (Postiglione and Li, 2009). A more critical view of China’s ethnic policies frames them as part of a civilizing project, where the Han majority is positioned as culturally superior. Harrell (1995) argues that such policies aim not just at integration, but at transforming minority groups to conform to Han norms. Similarly, Gladney (1994) shows how minority identities are constructed as culturally distinct and subordinate, reinforcing Han centrality in national narratives. Scholars have argued that the Chinese government uses education not to celebrate ethnic diversity or foster intercultural understanding, but to cultivate a singular national identity centred around Han cultural norms and Mandarin language use (Lin, 2023; Tsung and Clarke, 2010). Zhiyong and Meng (2015) commented that the assimilationist agenda is a core reason why many minority students report feelings of displacement, cultural alienation, and marginalization within the system, which Zhu and Meng named the approach by Han’s “culturalization” and “politicization” (2016). Acknowledging this context is essential to critically examining how education policies serve as a mechanism of control, rather than empowerment, for ethnic minority communities in China.

Proponents argue that the Chinese proficiency of minority students can change their future (Jiang et al., 2020; Lien, 2022). Some scholars critique and regard mono-language practice in schools as “submersion” education, which can lead to subtractive bilingualism learning (Cummins, 2001) and a sense of cultural dislocation (Ogbu, 2003). The specific manifestations of students’ maladjustment are that they have low literacy in both minority languages and Chinese (Postiglione et al., 2007) and that they restrict graduates’ ability to find work in their community (Badeng Nima, 2001).

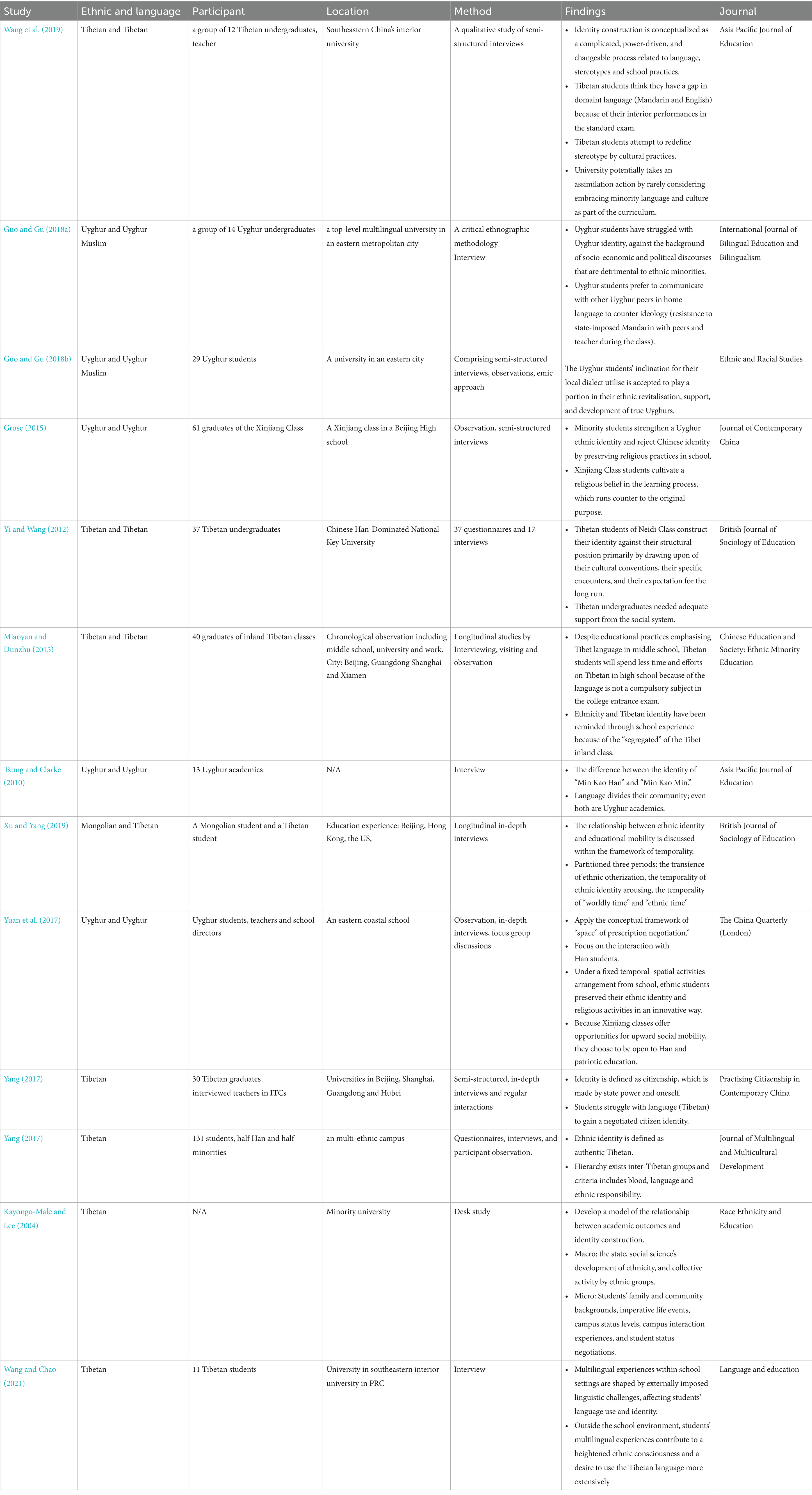

Methodologies

All studies included in this review employed qualitative methodologies, with a primary focus on narrative inquiry and semi-structured interviews, supplemented by focus groups and observations. Semi-structured interviews provided participants with the flexibility to articulate their experiences openly, allowing researchers to gain rich and nuanced insights (Patton et al., 2017). One study was a desk-based review that did not involve direct interaction with participants (Kayongo-Male and Lee, 2004). Five studies utilized small sample sizes (fewer than 29 participants), facilitating detailed and in-depth analyses (Xu and Yang, 2019). Tibetan and Uyghur minorities were prominently featured, with six studies focusing on Tibetans and five on Uyghurs, while other ethnic groups received significantly less attention. Of China’s 55 recognized minorities, only one study focused on Hui and one on Mongolians. Most of the research concentrated on middle school and university students, with 11 studies addressing these groups. Only one study explored younger students, examining Bai elementary school students in southeastern China (Wang, 2011).

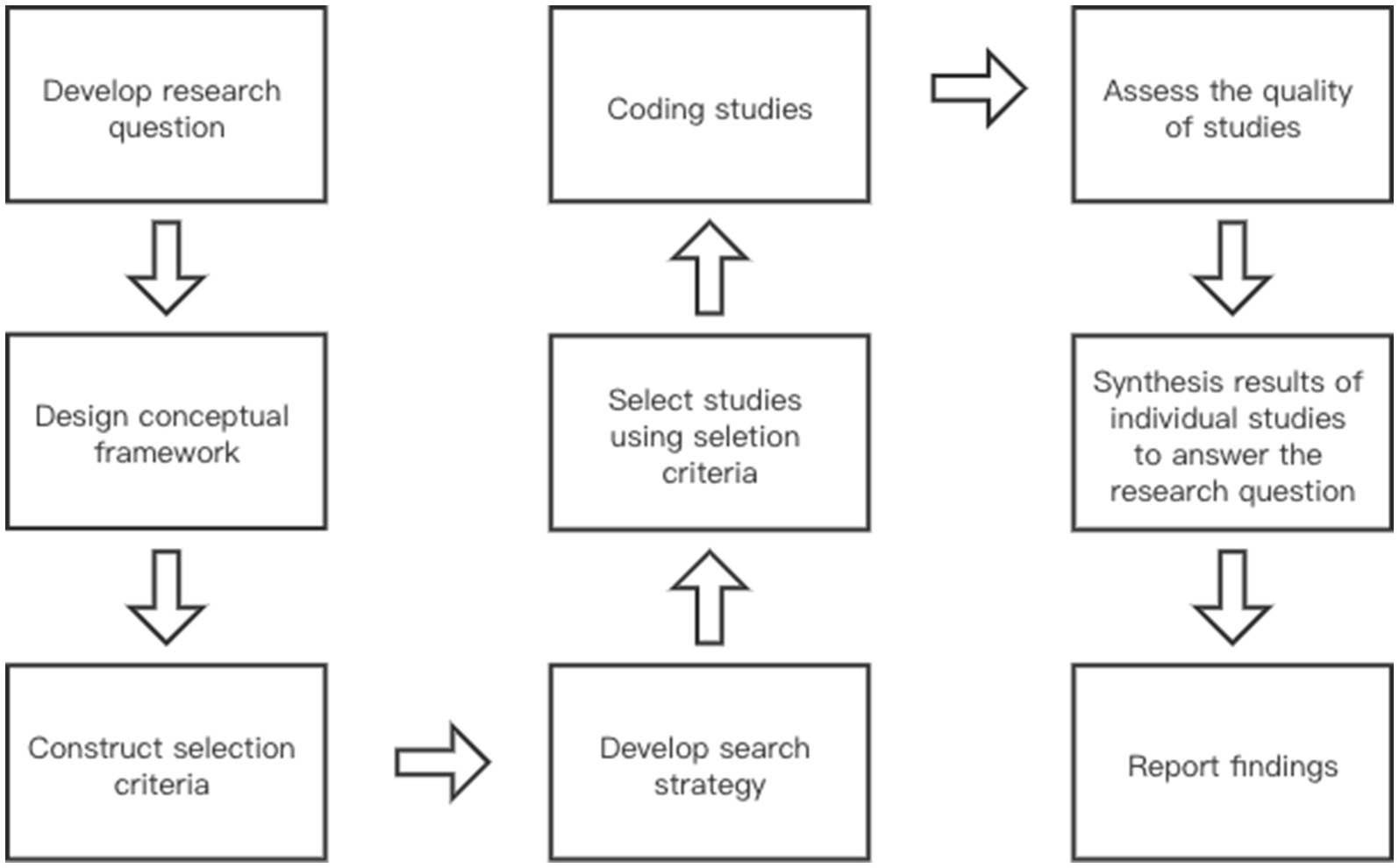

This study employs a systematized review rather than a full systematic review due to resource and methodological constraints. While systematic reviews provide an exhaustive and rigorous analysis involving comprehensive searches across multiple databases and dual-independent reviewing, systematized reviews adapt these principles to fit limited resources, focusing on fewer databases and often involving a single reviewer. Given the time constraints and the scope of this academic project, a systematized review was more feasible, relying on the Web of Science database of Sheffield Hallam University and English-language studies. This approach allowed for a structured and transparent synthesis of literature on the identity construction of Chinese ethnic minority students in Neidi Ban, aligning with the qualitative and exploratory nature of the research while balancing practicality and methodological rigour. This systematized review synthesizes existing literature on the identity construction of Chinese ethnic minority students in host schools, intending to provide evidence to inform policy development (Newman and Gough, 2020). A systematic review, defined as “a review of existing research using explicit, accountable, rigorous research methods” (Gough et al., 2017, p. 4), is commonly applied in educational research. However, due to resource constraints, a systematized review was deemed more appropriate for this study (Grant and Booth, 2009). The review process, following guidelines by Siddaway et al. (2019) and Newman and Gough (2020), involved scoping questions, planning, identifying, and screening studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The systematic review process by Newman and Gough (2020, p. 6).

The review addressed the question, What is known about the relationship between the identity construction of Chinese ethnic minority students and schools after migration? Searches were conducted in the Web of Science (WoS) databases between July and August 2023, targeting studies published in English from 2000 to 2023. The inclusion criteria focused on participants ranging from kindergarten to university, officially recognized as ethnic minorities in China, and studying in eastern coastal cities. Chinese-language studies were excluded, as comprehensive reviews already exist (e.g., Wang, 2018a, 2018b), and the lack of access to authoritative Chinese databases presented additional barriers. This limitation underscores how research in minority languages can be marginalized and overlooked (Tsung and Clarke, 2010). Consequently, the review acknowledges the potential omission of significant findings published in other languages. The following search strings were applied:

• “identity construction” OR “identity establishment” OR “identity development” OR “negotiating identity.”

• AND “Chinese ethnic minority” OR “Chinese minority group.”

• AND “school curriculum” OR “schooling” OR “curriculum setting” OR “education.”

• AND “migration” OR “internal migration” OR “interior school” OR “southeast city” OR “non-autonomous region.”

A total of 693 articles were identified through the searches, and the details of the screening process are illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (Moher et al., 2009) in Figure 3.

This systematic review followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to ensure transparency and replicability. The selection process involved four key stages.

Stage 1—identification: a total of 699 records were retrieved through database searches. After removing duplicates (16 records) and irrelevant topics, 683 titles were screened.

Stage 2—screening, from the title screening, 152 abstracts were selected for further review. A total of 541 records were excluded based on criteria such as no Chinese ethnic minority focus, no school involvement, lack of identity information, incorrect or missing language elements, and off-topic results.

Stage 3—eligibility: 48 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 33 articles were excluded due to factors such as incorrect location, focus on teachers rather than students, emphasis on language proficiency or language policy, and textbook analysis. An additional 4 studies were included from reference lists.

Stage 5—inclusion: a total of 15 studies were included in the systematic review. The PRISMA flowchart (Figure 3) visually represents this selection process, detailing the number of records at each stage and the rationale for exclusions. This rigorous procedure ensures a comprehensive and methodologically sound review of relevant literature.

Stage 6—we re-go through all selected journals, expecting 2 published as books and thesis from WoS, a final total of 13 articles have been analyzed.

Selection criteria

This search focused on studies addressing three key components: Chinese ethnic minorities, inland schools (Neidi Ban), and identity construction, published between 2000 and 2023 in English-language journals. The review prioritized centralized sorting and analysis of nearly two decades of literature to ensure a timely and relevant synthesis of research findings. To improve the accuracy of school location data, only studies that explicitly identified inland schools (Neidi Ban) as the study setting were included. Articles were excluded if the school locations were anonymous, pseudonyms were used without identifiable context, or if key elements of relevance to this review were absent. Studies entirely unrelated to the research topic were also removed. For instance, excluded articles discussed topics such as the trilingual teaching program for the Naxi ethnic group within their home region, family wellbeing among Nigerian immigrants in Guangzhou, or identity construction among immigrant minority workers. This rigorous screening ensured that the final selection of articles directly addressed the focus of this review.

Procedures

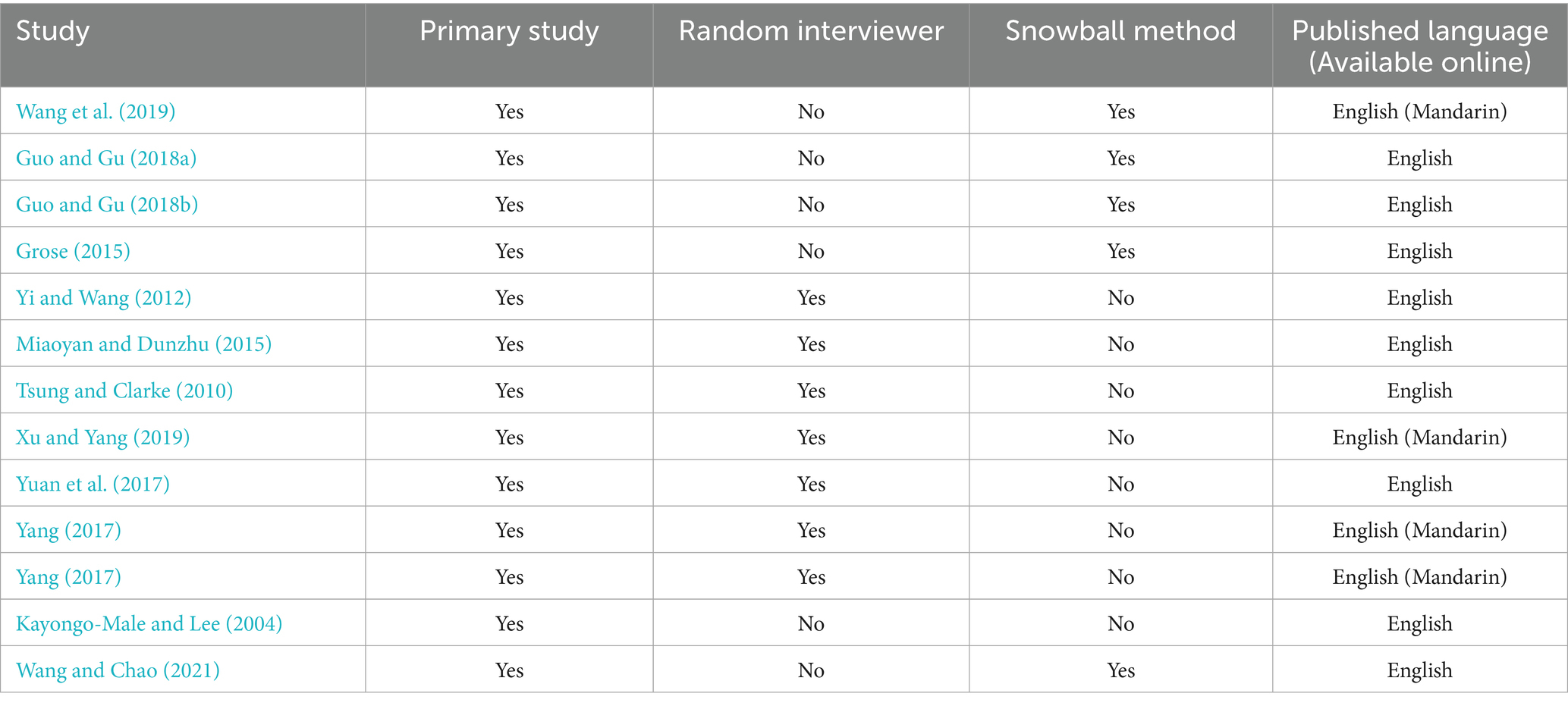

Following Gough’s (2007) framework, the selected studies were critically appraised for their research design, methodological rigor, and relevance to the research question. All articles included in the final review met acceptable quality standards (see Table 1). Key data, including participant demographics, school locations, methodologies, and findings, were extracted and summarized (see Table 2). Using an exploratory and iterative process, the data were regrouped and synthesized through a broadly configurative synthesis approach (Newman and Gough, 2020). The findings highlight that the identity construction of Chinese ethnic minority students in inland schools (Neidi Ban) is shaped by three key factors: language learning, cultural conflict, and school practices. These perspectives are discussed in detail in the next section.

Results

Each study was systematically coded for key research elements, including the applied methodology (qualitative or quantitative approach, data collection techniques such as interviews, surveys, or ethnographic observations) and the study’s findings (major themes, patterns in identity construction, and the impact of linguistic and cultural factors). This coding process facilitated comparative analysis and synthesis of the diverse perspectives presented in the reviewed literature. The selected articles are catalogued in Table 1, covering publications from 2000 to 2023 across various academic journals. Most of these studies are concentrated in the disciplines of sociology and linguistic education, reflecting a strong academic focus on the intersections of social identity, language acquisition, and educational experiences among Chinese ethnic minority students.

Key concepts

The identity analysis within the selected papers can be categorized into academic identity (Wang, 2011; Miaoyan and Dunzhu, 2015; Tsung and Clarke, 2010; Kayongo-Male and Lee, 2004) and ethnic identity (Guo and Gu, 2018a; Guo and Gu, 2018b; Grose, 2015; Xu and Yang, 2019; Yuan et al., 2017; Yang, 2017). Academic identity refers to ethnic minority students’ responses to academic activities, whether positive or negative. It encompasses how these students engage with and perceive academic settings and tasks. Second, ethnic identity represents the cultural and social identity inherited from the ethnic group to which the student belongs.

Yang (2017) applied Weber’s (2008) concept of the “safe citizen” to explore the tensions between minority ethnicity and the Chinese state. Yi and Wang (2012) introduced the notion of “self-worth” as a critical dimension of identity, arguing that a sense of self-worth among ethnic minority students is intrinsically tied to their perceived prospects. This underscores the importance of inland schools (Neidi Ban) not only in delivering quality education but also in fostering a sense of self-worth among minority students. The selected articles conceptualize internal migration to non-autonomous regions through various lenses. Most studies focused on academic mobility facilitated by educational policies, such as the Xinjiang Class program (a type of the inland boarding school/class). Furthermore, it should be noted that many Hui communities have long-standing historical roots in inland cities and regions. Wang (2011) specifically examines contemporary Hui migration flows from rural Ningxia to urban centers such as Lanzhou during the economic reform era. Unlike most ethnic minorities in China, the Hui do not have a distinct language, which has enabled them to disperse and integrate more widely across inland regions. Therefore, in this study, the term “immigrants” refers specifically to Hui individuals who are not originally from these inland areas (Xinjiang region). Xu and Yang (2019) extended this perspective by describing such movements as educational mobility, which refers to the geographic relocation of students from their hometowns to other regions for educational purposes. This broader conceptualization highlights the interplay between physical migration and the trans-formative effects of education on identity construction.

Overall, of the 13 selected articles, nine described the impact of language tension on identity construction, five mentioned the impact of school practices and experiences on minority identity construction, and 3 analyzed the conflict between minority culture and dominant Chinese culture in education, which suggests that language tension, cultural differences, and school factors are key factors that profoundly affect the identity construction of minority students. These factors emerged as important themes in the studies we analyzed, highlighting their central role in shaping how minority students navigate their identities in educational settings.

Discussion on ethnic minority students’ language and identity construction

Beyond language acquisition, Neidi Ban schooling plays a significant role in shaping students’ perceptions of their ethnicity, family, and national identity (Disi, 2023). The structured curriculum, which prioritizes Mandarin proficiency and standardized national knowledge, influences how students see their relationship with their home communities and cultural heritage (Yi and Wang, 2012). While some students view Mandarin education as a tool for upward mobility, others experience cultural displacement as minority languages and traditions become secondary in school settings. Further research should explore how specific pedagogical practices contribute to students’ negotiation of ethnic and national identities.

Several studies in this review highlight a strong correlation between ethnic minority languages and identity construction, focusing on two primary strands. The first examines how language learning by ethnic minority groups influences their academic identity, while the second explores how ethnic identity is shaped by the interplay of mother tongues, Mandarin, and English (Wang and Chao, 2021). Academic identity in this context refers to the negotiation, struggle, and adaptation to dominant educational practices within classrooms and campus environments. For Tibetan high school students, the pressures of the college entrance examination often shift their focus away from their mother tongue to other mandatory subjects, leading to a decline in their proficiency in Tibetan (Miaoyan and Dunzhu, 2015). Leibold and Dorjee (2023) similarly highlight the colonial-style structures of Tibetan boarding schools on the plateau, arguing that these institutions enforce assimilation and reproduce cultural erasure under the guise of educational uplift. Yang (2017) describes this phenomenon as the “aphasia” of the home language, reflecting a loss of linguistic connection to their ethnic roots. The second strand delves into the relationship between ethnic identity and language. Guo and Gu (2016) explored how Uyghur students navigate their ethnic identity within the broader socio-political and neoliberal landscape that marginalizes minorities. While these students acknowledge the economic advantages of Mandarin proficiency, they actively use their native language in daily interactions to preserve, revitalize, and affirm their Uyghur identity. In another study, Guo and Gu (2016) examined the role of English learning for Uyghur students. They argue that acquiring English provides these students with opportunities to engage with Western cultural values, fostering a broader perspective on language and identity. This exposure enables Uyghur students to reassess their ethnic identity through the lens of individualism, open-mindedness, and global cultural understanding.

Wang et al. (2019) analyzed Tibetan students’ identity construction through Norton’s identity theory and positioning theory, linking their positioning to language, stereotypes from Han peers, and school practices. Tibetan students often perceive a gap in their Mandarin and English proficiency due to standard examinations, resulting in feelings of academic inferiority (Wang and Chao, 2021). Despite their efforts to counter stereotypes rooted in economic and geographical biases, they remain marginalized in Han-dominated schools. The divide between “Min Kao Min” (minority students taking college entrance exams in their native languages) and “Min Kao Han” (students tested in Mandarin) further complicates identity dynamics. According to Tsung and Clarke (2010), “Min Kao Han” students generally exhibit superior Mandarin proficiency compared to “Min Kao Min” students, creating two distinct communities even within the same ethnic group. Yang (2018b) extends this discussion to ethnic authenticity, revealing that some Tibetan students assess authenticity based on criteria such as linguistic fluency, ethnic responsibility, and lineage purity. Those who fail to meet these standards often find themselves excluded from Tibetan social circles. However, Yang’s findings remain unconfirmed in broader contexts, and this notion of authenticity warrants further investigation.

The school experiences of ethnic minority students demonstrate that both academic and ethnic identities are actively constructed and renegotiated through the processes of learning Mandarin and English (Disi, 2023). The use of their mother tongue outside of class is often perceived as resistance to the dominance of Mandarin in schools. Additionally, disparities in mother tongue usage and proficiency, influenced by academic background, create divisions among students within the same ethnic group. These dynamics underscore the multifaceted and evolving nature of identity construction among ethnic minority students in educational settings.

Ethnic minority students’ culture and identity construction

In addition to language, cultural differences significantly contribute to the identity struggles faced by ethnic minority students in Han-dominated schools. For Uyghur students, the cultural divergence from Han society is rooted in religious beliefs. While Han culture is heavily influenced by Confucianism, Uyghurs are predominantly Muslim, adhering to Islamic teachings and practices. Grose (2015) highlights how graduates of the Xinjiang Class are portrayed as educated and socially aware but are subjected to strict prohibitions on religious activities within schools, such as prayer, wearing headscarves, and celebrating Muslim holidays. Despite these restrictions, Uyghur students often find covert ways to maintain their religious practices, including secretly praying, reading the Qur’an, and performing du’a. Grose argues that this duality—rejecting government control while embracing Islam—reflects a simultaneous rejection of Chinese interference and the assertion of a non-Chinese ethnonational identity (2015). Xu and Yang (2019), taking a longitudinal perspective, analyzed the cultural and identity construction of ethnic minority students who experienced educational mobility. Their research identifies three stages of ethnic identity development. Initially, prolonged exposure to Han culture and Mandarin led to segregation, as ethnic peers questioned the “authenticity” of mobile students. This was followed by an awakening of ethnic identity, often triggered by pivotal experiences such as mentorship or educational opportunities. However, upon recognizing the systemic inequalities faced by their ethnic group, many students shifted their focus toward achieving financial stability over advocating for ethnic equality.

Yuan et al. (2017) also adopted a dynamic perspective by examining identity transformation through the lens of space. Their study synthesized Uyghur students’ daily timetables to analyze interactions with Han peers and ethnic peers across classrooms, dormitories, and school cafeterias. Unlike the intense cultural conflicts reported in other studies (e.g., Grose, 2015; Xu and Yang, 2019), the students in Yuan, Qian, and Zhu’s research appeared to adopt a gentler, more innovative approach to preserving their ethnic identity and religious practices. Their adaptability to the temporal and spatial arrangements of school life seemed driven by a desire for upward social mobility. Similarly, Yi and Wang (2012) explored identity construction through the concept of “self-worth,” examining how ethnic minority students navigate their experiences in Han-dominated campuses. Students employed symbolic resources such as cultural traditions, unique lived experiences, and aspirations for the future to resist the dominance of Han culture (Disi, 2023). They also developed a consciousness of “biographical continuity” (p. 78), paralleling the temporality of ethnic awakening described by Yi and Wang. However, the authors criticized the policy of encouraging Tibetan students to study in interior schools, arguing that it fails to provide sufficient academic choices or support cultural diversity. Consequently, Tibetan students often underperform academically and struggle to develop a sense of self-worth or belonging within the broader Chinese community.

These studies collectively highlight how ethnic minority students grapple with cultural differences in Han-dominated schools. By this point, Postiglione and Li (2009) also criticized that whilst inland schools have raised academic standards, forced separation from families, the supremacy of Mandarin language teaching and living in a Han Chinese cultural environment often leads to loss of language, cultural alienation and identity challenges for Tibetan students. While some students find ways to resist cultural hegemony and maintain their ethnic identity, others adapt to achieve upward mobility, often at the expense of cultural and academic fulfilment. These findings underscore the need for policies that support both cultural diversity and academic equity for ethnic minority students.

School practices and students’ identity construction

Ethnic identity plays a pivotal role in shaping the experiences of minority students in inner-city schools, where school practices are often perceived as oppressive to their cultural heritage and linguistic diversity (Kayongo-Male and Lee, 2004). These practices, as evidenced in several studies, encompass teachers’ attitudes toward minority students, teaching methods, curriculum design, and overall school culture. Wang (2011) critiques the reliance on rote memorization in elementary schools, arguing that this method stifles students’ ability to think critically and independently. Similarly, Wang and Miaoyan and Dunzhu (2015) highlight the lack of representation of ethnic cultures and knowledge in textbooks. Drawing from Apple’s (1992) view that textbooks are not neutral carriers of knowledge but reflect political, social, and cultural agendas, these studies suggest that schools seldom incorporate minority languages and cultures into their curricula. Chu (2015, 2017) demonstrates that minority groups are often portrayed through a celebratory yet superficial lens, emphasizing costumes, festivals, and loyalty to the state while omitting structural inequalities or genuine cultural complexity. This visual and textual framing reinforces a Han-centric national identity under the guise of diversity. Similarly, Yan and Vickers (2019, 2024) show that textbook content has increasingly shifted toward assimilationist discourses since the 1990s, aligning with broader ideological trends that prioritize national unity over ethnocultural inclusion. Incorporating this body of research strengthens the argument that Chinese educational materials serve as tools for ideological reproduction, not only excluding minority languages and perspectives but actively shaping students’ perceptions of ethnic hierarchy and national identity.

As a result, minority students are taught content that diverges significantly from the language and culture they experience at home. Wang et al. (2019) further conclude that such practices in interior schools serve as a mechanism for assimilation, gradually eroding the distinct cultural identities of ethnic minority students. These school practices are closely linked to state policies, particularly the promotion of Mandarin as the sole language of instruction in classrooms. The Mandarin-only policy reinforces linguistic hegemony, effectively marginalizing minority languages and cultures. As He (2017) argues, this language policy is not a neutral or purely practical choice, but a strategic assertion of state power that challenges the principles of multicultural education (Banks, 2008; Banks, 2019) and limits the space for linguistic diversity in minority regions. This systemic prioritization of Mandarin creates an environment where minority languages are devalued and excluded, leaving little room for teachers or schools to address the cultural and linguistic needs of minority students. Consequently, the bilingual abilities and cultural heritage of ethnic minority students are overlooked, deepening their sense of marginalization and further alienating them from their ethnic identities.

Limitations and implications of the study

Research to date

Current research on ethnic minority languages and identities is constrained by the limited use of quantitative methodologies. Among the articles included in this review, the predominant approach is qualitative research, often relying on individual reflections and theoretical discussions. Reflective experiences and philosophical speculation constitute a significant portion of the studies in this field, as highlighted by Wang (2018a, 2018b) in a critical review of minority education. However, integrating quantitative methods, such as measurements of language proficiency and identity markers, could provide a more comprehensive model of the interaction between these elements. While some studies employ diverse methodologies to achieve detailed insights, others rely heavily on interviews with small sample sizes. For instance, Xu and Yang (2019) identified three critical temporalities of ethnic identity based on just two interviewees. Similarly, Wang et al. (2019) acknowledged that their limited sample size restricted their understanding of Tibetan students’ identity positioning and emphasized the need for more robust research supported by sufficient empirical evidence.

A second limitation of the existing literature is the lack of integrated perspectives on identity construction. Most studies are influenced by acculturation and linguistic frameworks, focusing narrowly on identity transformation because of intercultural interactions or language conflicts between native and host languages. This emphasis has overlooked other dimensions of ethnic identity construction within the Chinese context. While previous studies have explored various aspects of ethnic identity construction, they have often paid insufficient attention to the political role of minority education within the Chinese context. A growing body of critical scholarship argues that educational policies targeting ethnic minorities are not merely developmental but are strategically designed to assimilate minorities into Han cultural norms, a process often described as Sinicization (Vickers, 2014; He, 2017). These policies frequently operate under the rhetoric of national unity and integration, but in practice, they marginalize minority languages, histories, and worldviews, reinforcing a hierarchical model of cultural legitimacy. As such, minority education functions as a state mechanism for consolidating over non-Han populations, particularly through the promotion of patriotic curricula and ideological conformity. Addressing this dimension is essential to understanding how ethnic identity is shaped not only by cultural narratives but also by the institutionalized politics of education in China. In contrast, more diverse perspectives on minority identity development and psychological identity are emerging in Western contexts. For example, research in the United States has explored developmental identity outcomes among minority groups (Schotte et al., 2018), while ongoing studies in the European Union examine identity from a developmental perspective (Erentaite et al., 2018). Incorporating varied frameworks to study identity construction among ethnically diverse students could provide a richer and more holistic understanding of these processes in China. Such an integrative approach represents a promising direction for future research in this field.

The concept of multicultural education (Banks, 2008; Banks, 2019), as articulated by scholars like James Banks, emphasizes cultural recognition, inclusion, and democratic participation. However, these principles may not fully align with the state-centred and “Minzu” integration orientation of China’s minority education policies. As Huang (2021) argues, educational inclusion in China tends to operate within a framework of selective representation where minority cultures are symbolically recognized but structurally marginalized. This reflects broader nation-building projects in which education is a tool for state-centred integration and assimilation of minority groups (Yan and Jackson, 2024). In contrast to James Banks’ research in the United States, which emphasizes structural inequalities and power struggles between ethnic groups, the Chinese model focuses more on the promotion of a unified national identity - the Chinese nation - through ideological, linguistic and curricular standardization. Thus, while the Western model can serve as a useful comparative lens, it must be critically adapted to the ideological, linguistic and institutional specificities of the Chinese education system. This approach is both theoretically flexible and contextually sensitive when examining how national identity is constructed and constrained in Chinese schooling.

Limitations of this review

This study has several notable limitations, primarily the reliance on a single database and the exclusive selection of published English-language journals. Using a single resource and screening process inherently introduces bias and compromise’s reliability, a common critique of systematized reviews. As Grant (2009, p. 103) observes, “Systematized reviews are typically conducted as a limited approach, in recognition that they are not able to draw upon the resources required for a full systematic review (such as over two reviewers).” The scope of this research was further constrained by utilizing only one English online search engine for the literature search. This approach likely excluded valuable contributions to the field published in books, edited volumes, or non-digital formats. Additionally, Chinese-language literature published in China was deliberately omitted to position the study within a global framework and stimulate broader international discussions on ethnicity education. While this decision enhances the global relevance of the findings, it risks overlooking significant domestic scholarship. Despite these limitations, this systematized review represents a meaningful effort to synthesize and consolidate existing literature in the field. By integrating findings from diverse studies, it offers a foundational step toward understanding the relationship between ethnic identity construction, language, and education among Chinese ethnic minorities. Future research would benefit from a more comprehensive approach, incorporating multiple databases, enlarging the year of the updated database, diverse publication formats, and multilingual sources to provide a more balanced and inclusive perspective.

Practical implications

A key gap exists in bridging the theoretical understanding of ethnic minority identity with actual school-level practices. To enhance minority students’ learning experiences in inland schools (Neidi Ban), several actionable steps can be undertaken. Incorporating multicultural and multilingual education into teaching practices can address core issues surrounding ethnic equality and the status of minority languages. Multicultural education emphasizes “ethnic equality, freedom, and social justice” (Wang et al., 2019, p. 179; Banks, 2008; Banks, 2019), while multilingual teaching challenges the marginalization of minority languages by promoting their recognition and use in educational contexts. Together, these approaches raise a critical question for education in the inland class: What is the ultimate purpose of education for ethnic minorities? Drawing from culturally responsive teaching (Gay, 2018) and culturally relevant teaching (Ladson-Billings, 2014), schools can implement strategies to preserve the cultural heritage of minority students while fostering academic achievement. These methods aim to make schools inclusive linguistic and cultural communities (Wang et al., 2019), reducing the division between Han and minority students. For example, instead of relying solely on teachers to deliver lessons about ethnic minorities and their geographic distribution, classrooms could encourage minority students to present their culture in bilingual or trilingual formats. Further, promoting “minority language learning” within the group of the “Han” as optional courses in the inland universities, this approach not only preserves linguistic diversity but also promotes critical thinking and multicultural awareness among all students. Such activities could stimulate dialogue on multi-ethnicity and mutual understanding, creating a more inclusive and dynamic classroom environment. By integrating these strategies, Inland Class can better support the cultural and academic needs of ethnic minority students, fostering a more equitable and inclusive educational landscape.

Future direction

This systematized review highlights several key areas that warrant further research. By addressing these gaps, future studies could significantly enhance the depth and breadth of research on the identity construction of ethnic minority students in China, offering more holistic and inclusive perspectives.

Age perspective

A notable gap exists in studies involving younger participants, particularly those in kindergarten and primary school. This scarcity may stem from challenges in conducting research and collecting data from younger age groups. Additionally, policy interventions tend to focus more on high school and university-age students, leading to a greater volume of studies on older groups. Addressing this gap by including younger participants in future research would provide a more comprehensive understanding of identity construction across all educational stages.

Representation of smaller ethnic minorities

The current body of literature disproportionately focuses on ethnic minorities with larger populations, such as Uyghurs and Tibetans. The experiences of the other 53 officially recognized minority groups in inland schools (Neidi Ban) are largely overlooked. While this emphasis aligns with policy-driven educational migration patterns, the economic motivations driving smaller ethnic minorities to study and live in southeast China also deserve attention. Expanding research to include these underrepresented groups could enrich our understanding of the diverse experiences and challenges faced by minority students.

Temporal and spatial dynamics of identity construction

Identity construction is inherently dynamic and evolves over time and across different contexts. However, most studies included in this review focus on a single period or location, neglecting the broader temporal and spatial dimensions of identity development. Yi and Wang (2012) inadvertently highlight the importance of examining these dimensions, particularly in understanding the complex strategies Tibetan students use to navigate identity challenges. Future research could explore the long-term factors influencing identity construction, providing insights into how national and self-identity continuity can be supported over time.

Conclusion

This study aimed to identify the factors influencing identity construction among ethnic minority students in the context of intra-migration within Chinese public schools. By examining and reviewing relevant literature, the research explored how Chinese ethnic minority students construct their identities in inland schools (Neidi Ban). While the study was constrained to a single database due to resource limitations, efforts to mitigate bias included reference tracking and an iterative refinement of search terms to enhance sensitivity and specificity. Articles were systematically screened and selected based on clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure consistency and minimize error.

The findings highlight that these students’ identities are deeply intertwined with linguistic integration in the interior academic environment, encompassing home languages, Mandarin, and English. Additionally, cultural and religious differences from the Han majority, as well as broader institutional practices, significantly shape their identity construction processes. While ethnicity is often regarded as a stable characteristic among ethnic minority students, this study emphasizes the importance of recognizing temporal changes in identity as a dynamic and evolving process.

We acknowledge that the implementation of multicultural and multilingual education in China, particularly for groups such as Tibetans and Uyghurs, is severely constrained by current political realities. Minority education initiatives, including Neidi class, are structured primarily around ideological integration and national unity, leaving little space for pedagogical approaches that genuinely centre minority languages, perspectives, or critical thinking. As Yan (2020) and others have noted, official narratives tightly govern how minority groups are represented and discussed in education. While our recommendations for fostering multicultural awareness and critical reflection may not be immediately feasible in this context, they should be understood as aspirational and value-driven goals. These proposals aim to encourage dialogue about long-term systemic change and serve as a counterpoint to dominant integration discourses. Even incremental shifts, such as more balanced textbook representations or localized cultural content, could represent important steps toward more inclusive education over time. Therefore, our findings underscore the need not only for pedagogical reforms but also for broader institutional reconsiderations of how ethnic diversity is approached in Chinese schooling.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Neidi Ban (内地班), refers to a state-run education program in China designed to provide ethnic minority students from remote, autonomous regions—particularly Tibet, Xinjiang, and other western provinces—the opportunity to study in economically developed inland cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou from primary and junior education level. This policy was initiated to enhance educational access, foster national unity, and integrate ethnic minorities into mainstream Chinese society (Department of Education, 2000; Wang and Phillion, 2009).

References

Apple, M. W. (1992). The text and cultural politics. Educ. Res. 21, 4–19. doi: 10.3102/0013189X021007004

Bourdieu, P. (2018). “The forms of capital” in The sociology of economic life. ed. M. Granovetter (London: Routledge), 78–92.

Chen, Y. (2008). Muslim Uyghur students in a Chinese boarding school: Social recapitalization as a response to ethnic integration. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Chu, Y. (2015). The power of knowledge: a critical analysis of the depiction of ethnic minorities in China’s elementary textbooks. Race Ethn. Educ. 18, 469–487. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2015.1013460

Chu, Y. (2017). Visualizing minority: images of ethnic minority groups in Chinese elementary social studies textbooks. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 42, 135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jssr.2017.05.005

Chu, Y. (2018). Constructing minzu: the representation of minzu and Zhonghua Minzu in Chinese elementary textbooks. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. 39, 941–953. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2017.1310715

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating intercultural identities in the multilingual classroom. CATESOL J. 12, 163–178. doi: 10.5070/B5.36467

Department of Education (1985). On the implementation of Xizang(Tibetan) high school classes in mainland (NeiDi). Beijing: Department of Education.

Department of Education (2000). On the implementation of Xinjiang (Uygur) high school classes in mainland (NeiDi) China. Beijing: Department of Education.

Disi, A. (2023). Multilingual Lived Experience and Identity Construction in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China. The University of Manchester, PhD thesis. Available at: https://pure.manchester.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/280558281/FULL_TEXT.PDF

Dong, J. (2009). ‘Isn’t it enough to be a Chinese speaker’: language ideology and migrant identity construction in a public primary school in Beijing. Lang. Commun. 29, 115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2009.01.002

Edwards, V. (2008). Multilingualism in the English-speaking world: Pedigree of nations. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Erentaite, R., Lannegrand-Willems, L., Negru-Subtirica, O., Vosylis, R., Sondaite, J., and Raižiene, S. (2018). Identity development among ethnic minority youth: integrating findings from studies in Europe. Eur. Psychol. 23, 324–335. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.21346.79040

Gao, F. (2016). Paradox of multiculturalism: invisibility of ‘Koreanness’ in Chinese language curriculum. Asian Ethn. 17, 467–479. doi: 10.1080/14631369.2015.1090373

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Multicultural Education Series. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gladney, D. C. (1994). Representing nationality in China: Refiguring majority/minority identities. J. Asian Stud. 53, 92–123. doi: 10.2307/2059528

Gough, D. (2007). Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res. Pap. Educ. 22, 213–228. doi: 10.1080/02671520701296189

Gough, D., Oliver, S., and Thomas, J. (Eds.) (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage.

Grant, M., and Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 26, 91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Grose, T. (2015). (re)embracing Islam in Neidi: the 'Xinjiang class' and the dynamics of Uyghur ethno-national identity. J. Contemp. China 24, 101–118. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2014.918408

Grose, T. A. (2010). The Xinjiang class: education, integration, and the Uyghurs. J. Muslim Minor. Aff. 30, 97–109. doi: 10.1080/13602001003650648

Guo, X. G., and Gu, M. M. (2016). Identity construction through English language learning in intra-national migration: a study on Uyghur students in China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 42, 2430–2447. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1205942

Guo, X., and Gu, M. (2018a). Exploring Uyghur university students' identities constructed through multilingual practices in China. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Bilingual. 21, 480–495. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2016.1184613

Guo, X., and Gu, M. (2018b). Reconfiguring Uyghurness in multilingualism: an internal migration perspective. Ethnic Racial Stud. 41, 2028–2047. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1343485

Han, Y., and Cassels Johnson, D. (2021). Chinese language policy and Uyghur youth: examining language policies and language ideologies. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 20, 183–196. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2020.1753193

Harrell, S. (ed.). (1995). Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers. University of Washington Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbtzm9s

He, S. (2017). An overview of China’s ethnic groups and their interactions. Sociology Mind. 7, 1–10. doi: 10.4236/sm.2017.71001

Huang, Y. (2021). The reflection on inclusive education in urban China–a case study in Beijing. Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield. Available at: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/28643/1/PhD%20Thesis.pdf

Jiang, L., Yang, M., and Yu, S. (2020). Chinese ethnic minority students’ investment in English learning empowered by digital multimodal composing. Tesol Q. 54, 954–979.

Kachru, B. (1985). “Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: English language in the outer circle” in English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures. eds. R. Quirk and H. Widowson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 11–36.

Kayongo-Male, D., and Lee, M. B. (2004). Macro and micro factors in ethnic identity construction and educational outcomes: minority university students in the People's Republic of China. Race Ethn. Educ. 7, 277–305. doi: 10.1080/1361332042000257074

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the remix. Harv. Educ. Rev. 84, 74–84. doi: 10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

Leibold, J., and Dorjee, T. (2023). Learning to be Chinese: colonial-style boarding schools on the Tibetan plateau. Comp. Educ. 60, 118–137. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2023.2250969

Lien, P. T. (2022). Tracing roots of attitudes toward race and affirmative action among immigrant Chinese Americans: learning from undergraduate international students. J. Divers. High. Educ. 15:731. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000319

Lin, J. C. (2023). Rethinking nationalistic history in China: Towards a multicultural Chinese identity. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 23, 178–194. doi: 10.1111/sena.12395

Lin, J. C., and Jackson, L. (2022). Just singing and dancing: official representations of ethnic minority cultures in China. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 24, 94–117. doi: 10.18251/ijme.v24i3.3007

Liu, J., and Edwards, V. (2017). Trilingual education in China: perspectives from a university programme for minority students. Int. J. Multiling. 14, 38–52. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1258983

Liu, X. (2023). Ethnic minority students’ access, participation and outcomes in preparatory classes in China: a case study of a School of Minzu Education. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 43, 173–188. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2021.1926918

Mackerras, C. (1994). China's minorities: Integration and modernisation in the twentieth century. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 139–166.

Martin, P. (2009). ‘They have lost their identity but not gained a British one’: non-traditional multilingual students in higher education in the United Kingdom. Lang. Educ. 24, 9–20. doi: 10.1080/09500780903194028

Mason, M., and Clarke, M. (2010). “Post-structuralism and education,” in International encyclopedia of education. eds. P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw (Elsevier), 6, 175–182.

Miaoyan, Y., and Dunzhu, N. (2015). Assimilation or ethnicisation: an exploration of inland Tibet class education policy and practice. Chinese Educ. Soc. Ethnic Minority Educ. 48, 341–352. doi: 10.1080/10611932.2015.1159828

Minhui, Q. (2007). Discontinuity and reconstruction: the hidden curriculum in schoolroom instruction in minority-nationality areas. Chin. Educ. Soc. 40, 60–76. doi: 10.2753/CED1061-1932400204

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

Mullaney, T. S., Leibold, J., Gros, S., and Vanden Bussche, E. A. (2012). Critical Han studies: The history, representation, and identity of China's majority. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

National Bureau of Statistics (2002). Zhongguo 2000 nian renkou pucha ziliao (China's 2000 Population Census). Available at: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2001/content_60740.htm

Newman, M., and Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: methodology, perspectives and application. Syst. Rev. Educ. Res. 64, 3–22. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1

Nima, B. (2001). Problems related to bilingual education in Tibet. Chin. Educ. Soc. 34, 91–102. doi: 10.2753/CED1061-1932340291

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Q. 31, 409–429. doi: 10.2307/3587831

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Bristol: Multilingual matters.

Ogbu, J. U. (2003). Black American students in an affluent suburb: A study of academic disengagement. London: Routledge.

Patton, D. U., Hong, J. S., Patel, S., and Kral, M. J. (2017). A systematic review of research strategies used in qualitative studies on school bullying and victimisation. Trauma Violence Abuse 18, 3–16. doi: 10.1177/1524838015588502

Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychol. Bull. 108, 499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499

Pieke, F. N., and Barabantseva, E. (2012). New and old diversities in contemporary China: editors' introduction. Mod. China 38, 3–9. doi: 10.1177/0097700411424403

Postiglione, G. A., Jiao, B., and Manlaji, (2007). “Language in Tibetan education the case of the Neidiban” in Bilingual education in China: Practices, policies and concepts. ed. A. W. Feng (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 49–71.

Postiglione, G. A., and Li, X. (2009). “Exceptions to the rule: rural and nomadic Tibetans gaining access to dislocated elite inland boarding schools” in Rural education in China’s social transition. eds. P. A. Kong and E. Hannum (London: Routledge), 88–107.

Schotte, K., Stanat, P., and Edele, A. (2018). Is integration always most adaptive? The role of cultural identity in academic achievement and in psychological adaptation of immigrant students in Germany. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 16–37. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0737-x

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., and Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 747–770. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Sleeter, C., and Carmona, J. F. (2017). Un-standardizing curriculum: Multicultural teaching in the standards-based classroom. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sun, N. Z. L., Loh, E. K. Y., and Liao, X. (2024). Comparing the effects of inhibitory control on Chinese Reading comprehension between learners of Chinese as a first and second language supporting the learning of Chinese as a second language implications for language education policy. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 77–97.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior” in Psychology of intergroup relations. eds. S. Worchel and W. G. Austin (Binfield: Nelson-Hall), 7–24.

The State Council Information Office of China (2005). The policy and practice of ethnic minorities in China. Beijing: The State Council Information Office of China.

The State Council of China. (1956). Instructions of the state council on the promotion of Putonghua. Available at: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/1956/02/06/state-council-instruction-concerning-spreading-putonghua/

Tsung, L., and Clarke, M. (2010). Dilemmas of identity, language and culture in higher education in China. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 30, 57–69. doi: 10.1080/02188790903503593

Vickers, E. (2014). “A civilising mission with Chinese characteristics? Education, colonialism and Chinese state formation in comparative perspective” in Constructing modern Asian citizenship. eds. E. Vickers and K. Kumar (New York, NY: Taylor and Francis), 50–79.