- Faculty of Medicine, Al-Quds University, Jerusalem, Palestine

This study explores the profound impact of COVID-19 quarantine on social media usage among university students in the West Bank, revealing a dramatic surge in engagement driven by the shift to remote learning and the need for digital socialization. With motivations for entertainment (52%) and social communication (28%) dominating, students reported increased social media use, which coincided with heightened study hours, reflecting its dual role as both a tool for academic adaptation and a potential distraction. Quarantine conditions also fostered stronger family relationships, with students spending more time with their families, yet satisfaction with academic performance and daily achievements remained low, highlighting the challenges of balancing increased digital engagement with productivity. This research underscores the complex interplay between social media, academic performance, and social dynamics during an unprecedented period of global disruption, offering valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and mental health professionals aiming to optimize social media’s role in academic and personal development.

1 Introduction

Social media has become an integral part of daily life for young adults, particularly university students who must balance academic, social, and familial responsibilities. In Palestine, the use of social media has grown rapidly, with rates increasing from 37% in January 2018 to 56% in January 2019, mirroring global trends (Techrasa, 2019). Platforms such as Facebook and Instagram have transformed how students communicate, collaborate, and access information, enabling activities like virtual study groups, peer discussions, and engagement with educational content (Dabbagh and Reo, 2011).

During the COVID-19 quarantine, the limitations imposed by isolation heightened boredom proneness among university students, prompting excessive social media use as a way to compensate for the lack of offline activities. This behavioral adjustment often resulted in over-engagement, leading to three key types of social media overload: information overload, communication overload, and system feature overload (Bowker, 2008). These distinct forms of overload placed significant demands on students’ emotional and cognitive capacities, making it challenging to maintain focus and effectively manage their academic responsibilities.

Excessive social media use, although offering certain benefits, brought about serious negative outcomes, including impaired academic performance and disrupted personal relationships. This issue was magnified during the pandemic as digital engagement surged in response to reduced face-to-face interactions. The over-reliance on social media during this period introduced a unique set of challenges, particularly social media overload. This phenomenon occurs when the volume of information, communication demands, and system features surpass an individual’s ability to process them effectively. Research highlights that this overload, compounded by boredom during prolonged confinement, exacerbated stress and disengagement, further diminishing students’ academic productivity (Bowker, 2008).

Globally, social media adoption has increased significantly, with 12% of Americans using social media in 2005 compared to 90% in 2015 (Pew Research Center, 2015). Common motivations for its use include maintaining social connections, accessing news, sharing content, and networking. While social media can support academic engagement, studies have highlighted its potential to foster social media addiction defined as compulsive online behaviors that interfere with daily responsibilities and emotional well-being (Ryan et al., 2014). This condition can negatively affect mood, productivity, and academic performance, with symptoms often likened to those of substance dependencies (Echeburua and de Corral, 2010).

Emerging literature suggests that the academic and social impacts of social media use vary depending on regional, demographic, and usage patterns. For example, studies indicate that prolonged use of social media is linked to reduced study time and lower academic achievement (Tsitsika et al., 2014). Gender differences further shape usage patterns, with women tending to spend more time on social networking platforms, while men often favor gaming and video platforms (Herring and Kapidzic, 2015). In the Palestinian context, social media serves as a platform for both educational and national discourse, sometimes at the expense of study time (Ezeah et al., 2013). While some research suggests a positive relationship between social media use and academic success (Owusu-Acheaw and Larson, 2015), findings vary significantly across different cultural and educational settings. For instance, Jordanian nursing students have expressed positive attitudes toward social media for academic and professional purposes (Al-Shdayfat, 2018).

Beyond academics, family relationships critical for the emotional support of university students may also be affected by increased online engagement. Strong family bonds contribute to students’ well-being, yet excessive social media use can diminish family interactions, particularly during periods of quarantine when students returned home (Alsanie, 2015). Studies from other regions have highlighted how strict lockdown measures during the pandemic often led to heightened stress, anxiety, and boredom (Reizer et al., 2021; Diotaiuti et al., 2023). These conditions prompted individuals to rely on social media not only for communication but also for entertainment and coping with life stressors, including through humor (Kuipers, 2002; Sebba-Elran, 2021). Such usage demonstrates both adaptive and maladaptive patterns, depending on individual traits like optimism and resourcefulness (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Marrero et al., 2020).

An important way to frame these observations is by drawing on established theoretical perspectives that explain individual and contextual influences on digital engagement. For example, Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) underscores how behavioral patterns (e.g., social media use), personal factors (e.g., motivations, self-efficacy), and environmental elements (e.g., quarantine constraints, family dynamics) interact reciprocally to shape overall outcomes. Meanwhile, the Uses and Gratifications approach posits that individuals use media platforms to fulfill specific needs, such as escapism, social connection, or academic collaboration. Integrating these frameworks into the present study underscores the complex interplay among social media usage, academic performance, and family relationships, particularly during an unprecedented period like the COVID-19 quarantine.

Recent research from Arab countries underscores how regional academic cultures and technological adaptation influenced students’ experiences with social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, a study in Libya found that students who actively used Facebook for academic communication developed stronger social capital and achieved higher GPAs, highlighting how social media, when used constructively, can enhance academic resilience in challenging times (Ahmed et al., 2020). In contrast, a Saudi study among medical students found a negative association between social media addiction and GPA, suggesting that excessive or non-purposeful use may hinder academic achievement (Alshanqiti et al., 2023). These differing outcomes emphasize that the impact of social media on academic performance is not uniform; rather, it is shaped by students’ usage patterns and the educational and cultural context in which they are embedded.

While global studies have extensively examined the impact of COVID-19 on university students, there remains a significant gap in understanding how Palestinian students, particularly those in the West Bank, have navigated these challenges. Existing research has primarily focused on general psychological impacts and risk perceptions among Palestinian adolescents during the pandemic (Aljuboori et al., 2020). However, there is a dearth of studies exploring the specific effects of increased social media usage on academic performance and family dynamics within this group. Addressing this gap is crucial, as cultural, educational, and technological contexts can uniquely influence these dynamics. This research aims to provide critical insights into how Palestinian students balance the demands of online and offline life within their socio-cultural context. The findings will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the role of social media in shaping student life and well-being in Palestine.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

This study targeted Palestinian university students enrolled in various institutions across the West Bank, representing diverse academic specializations. A total of 385 participants were recruited through convenience sampling, with data collected via an online questionnaire will be provided in Supplementary materials. Inclusion criteria were limited to students currently enrolled in West Bank universities, regardless of age or gender. To maintain the study’s geographic specificity, students attending universities outside this region were excluded.

2.2 Research design and data collection

A cross-sectional descriptive research design was utilized, as it effectively addresses questions related to social media usage and its associated impacts. The data collection process was structured into three distinct sections. The first section focused on demographic information, gathering data on participants’ age, gender, university affiliation, college, academic degree, academic year, and GPA. The second section investigated students’ social media usage before and after the COVID-19 quarantine, including daily hours spent online and the most frequently used platforms. The final section explored students’ satisfaction with their academic performance and social interactions, with a particular emphasis on how social media influenced these areas.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Several statistical analyses were performed to examine relationships between key variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to explore the associations between average hours spent on social media and both average study hours and the number of platforms used. An independent sample t-test compared the average time spent on social media by male and female participants, while the McNemar test assessed changes in time allocation between social media use and family interactions before and after quarantine. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS software, with significance levels set at p < 0.05.

2.4 Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were rigorously observed throughout the study. Participants were informed of their rights and provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose. Informed consent was obtained prior to participation, ensuring that respondents were aware of their right to withdraw at any point without repercussions. Measures were taken to protect participants’ anonymity and confidentiality, with no personally identifiable information collected. All responses remained confidential and were used exclusively for research purposes. This strict adherence to ethical standards ensured the integrity and reliability of the study findings.

2.5 AI-assisted writing process

In this study, the writing process involved a structured approach to ensure high-quality, reader-friendly documentation. Initially, the manuscript was drafted based on the research findings, laying the foundation for the content. Subsequently, generative AI tools were employed to enhance the text by identifying and correcting grammatical errors, improving sentence structures for better readability, and suggesting alternative phrasings to enhance clarity. Finally, the AI-enhanced manuscript underwent a thorough review by professional editors to ensure accuracy, contextual relevance, and adherence to publication standards, thereby balancing technological efficiency with expert oversight.

2.6 Research questions and hypotheses

This study aimed to examine how quarantine conditions influenced university students’ social media use, study habits, and family interactions. The following research questions (RQs) and corresponding hypotheses (H) guided our investigation:

RQ1: Does daily social media usage differ before and after the COVID-19 quarantine?

H1: We hypothesize that social media usage will significantly increase during the quarantine period compared to pre-quarantine levels.

RQ2: Does daily study time differ before and after the COVID-19 quarantine?

H2: We hypothesize that average study hours will also increase under quarantine conditions, owing to the shift to remote learning and reduced outside activities.

RQ3: Are there gender differences in daily social media usage after quarantine?

H3: We hypothesize that female students, on average, will report higher daily social media usage than male students, reflecting known gender-related patterns in online engagement (Herring and Kapidzic, 2015).

RQ4: Does time spent with family change from before to after the COVID-19 quarantine?

H4: We hypothesize that enforced time at home will lead to increased family interactions, resulting in a statistically significant rise in the average daily time spent with family members.

RQ5: Is daily social media usage correlated with daily study hours?

H5: We hypothesize that the shift to digital platforms for both academic and social activities may result in a positive association between social media use and study time, as students increasingly rely on online resources and peer collaboration.

RQ6: Is the number of social media platforms used associated with total daily social media usage?

H6: We hypothesize that students who engage on multiple platforms will report more total time spent online, reflecting greater overall reliance on digital networks.

3 Results

3.1 Participant demographics

The study included 385 Palestinian university students from various institutions across the West Bank, comprising 220 females (58.7%) and 155 males (41.3%). Participants’ GPAs ranged from 73.9 to 84.9, with students from the Faculty of Science and Technology reporting the highest average GPA (M = 84.9, SD = 6.5).

3.2 Social media usage and academic habits

Paired samples t-tests revealed significant changes in both social media usage and study habits. The average time spent on social media increased markedly, rising from 4.55 h per day (SD = 1.97) before quarantine to 7.55 h per day (SD = 3.56) after quarantine (p < 0.001). This increase of approximately 3 h per day highlights the profound shift in digital engagement during quarantine, confirming a statistically significant change in usage patterns.

Similarly, a moderate but significant increase was observed in daily study hours. Students reported an average of 3.79 h per day (SD = 1.86) spent studying before quarantine, compared to 4.35 h per day (SD = 2.73) after quarantine (p < 0.001). This increase of 0.56 h per day suggests that quarantine conditions influenced study habits, potentially due to extended time spent at home. These findings underscore the dual impact of quarantine on both academic and digital behaviors (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2 for detailed statistics on mean and standard deviations of social media usage and study hours before and after quarantine).

3.3 Motivations for social media use

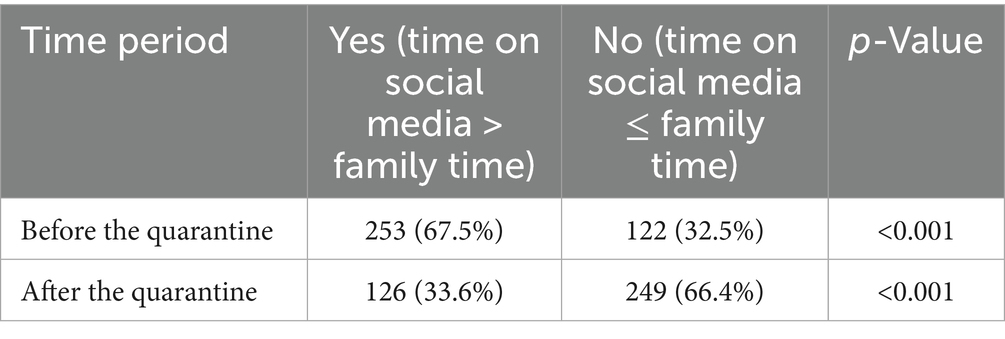

Analysis of students’ motivations for social media use revealed that the majority (52%) engaged with these platforms primarily for fun and relaxation. Social communication was the second most common reason, accounting for 28% of responses. In contrast, only 21% reported using social media for information searching, reflecting a lower focus on academic or informational purposes. Notably, work-related usage was minimal, with just 2% of participants citing this as their primary motivation. These findings indicate that recreational and social factors dominate social media usage among students, with professional purposes being a relatively minor component (see Figure 1 for a detailed breakdown).

Figure 1. Students’ motivations for using social media during the COVID-19 quarantine. The figure displays the distribution of primary motivations for social media use among students. The majority used social media for fun and relaxation (52%) and communication (28%), while fewer reported using it for information-seeking (18%) or business purposes (2%).

3.4 Platform preferences

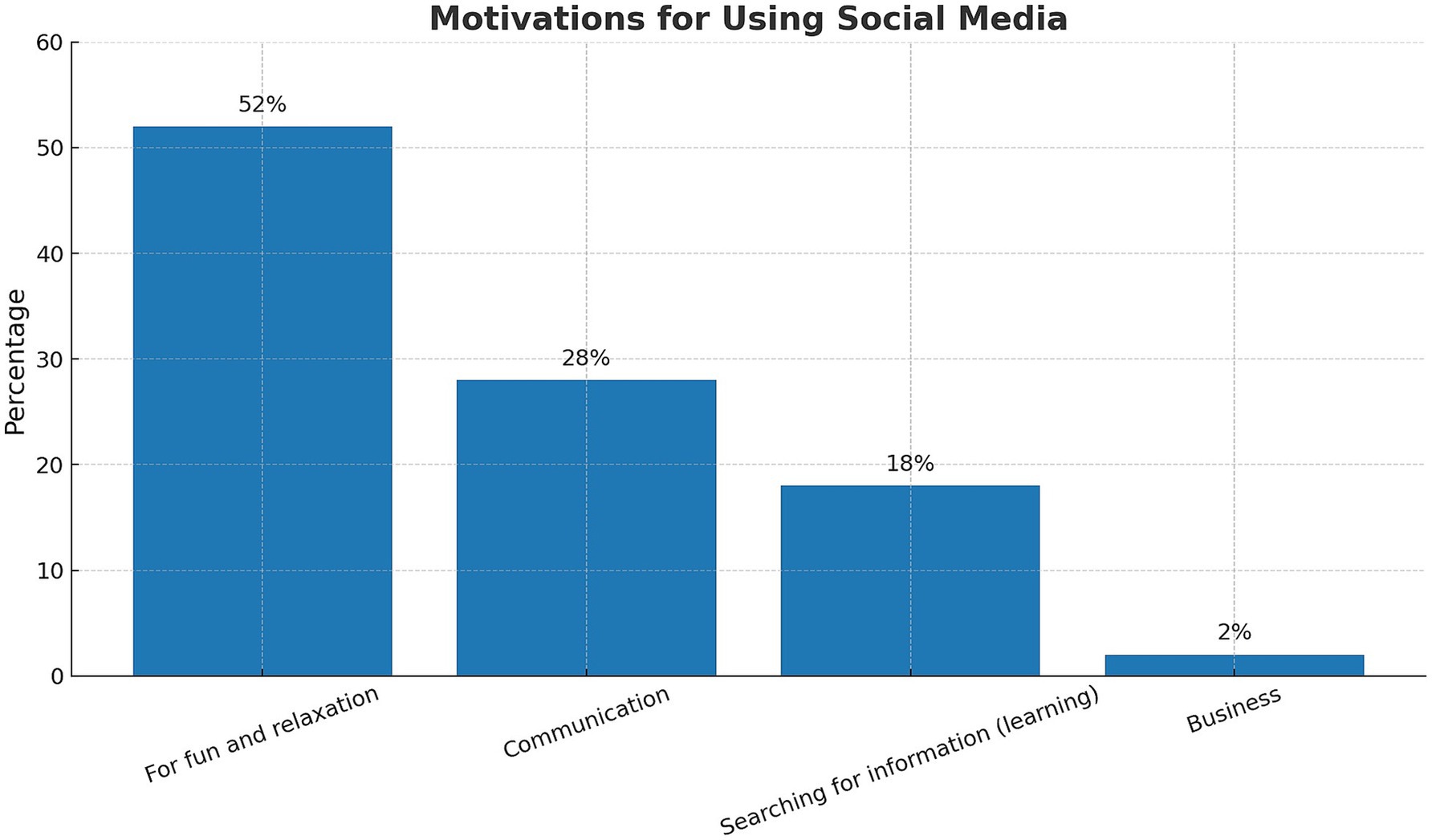

Among social media platforms, Facebook was the most widely used, with 44.8% of participants indicating it as their preferred platform. Instagram ranked second, while X application was the least utilized, with only 0.3% of students reporting its use (see Figure 2 for platform usage frequencies).

Figure 2. Frequency of social media platform usage among university students during COVID-19 quarantine. Bar chart illustrating the number of respondents who reported using each social media platform. Facebook was the most frequently used (n = 168), followed by Instagram (n = 110) and WhatsApp (n = 45), while usage of platforms such as Snapchat and X application was minimal.

3.5 Family interactions and relationships

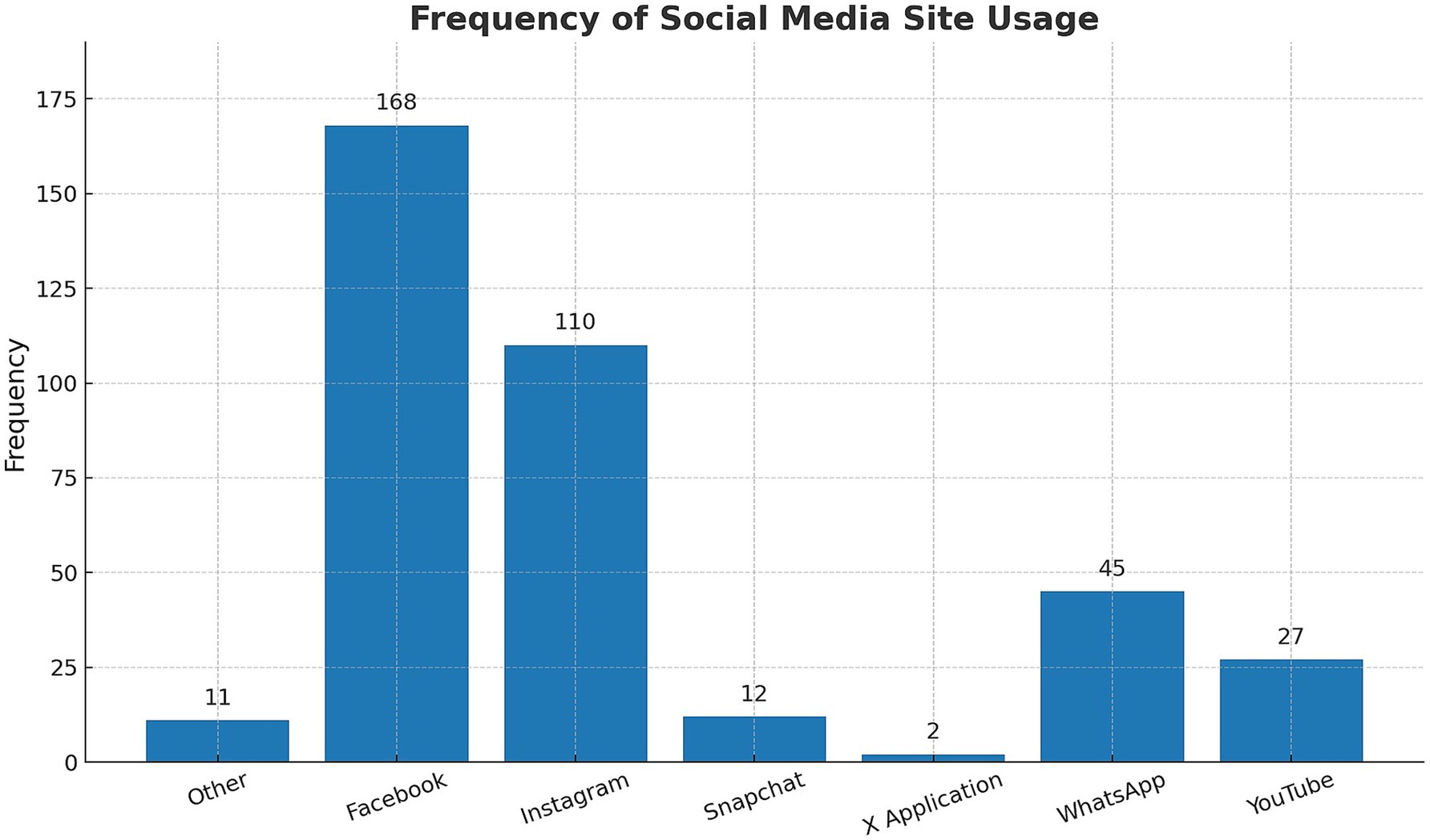

The study also examined the relationship between social media use and family interactions. A significant difference was observed in the time spent with family members before and after quarantine. Time spent with family increased notably after quarantine, suggesting that the enforced time at home fostered stronger family connections (see Table 1 for changes in time allocation).

3.6 Correlation and satisfaction levels

Pearson correlation analyses identified several significant relationships between key variables. A weak but significant positive correlation was found between average daily hours spent on social media and daily study hours (r = 0.133, p = 0.01), suggesting that higher social media use was associated with slightly increased study time. Additionally, a weak positive correlation was observed between the number of social media platforms used and the total time spent on social media (r = 0.261, p < 0.001), indicating that students active on multiple platforms tended to spend more time online overall.

Using the McNemar test, the study confirmed a statistically significant increase in time spent with family post-quarantine (p < 0.001). These findings highlight how the unique circumstances of quarantine positively influenced family relationships, even as social media usage surged. Supplementary Table 3 provides details on correlations between social media usage, study habits, and platform use.

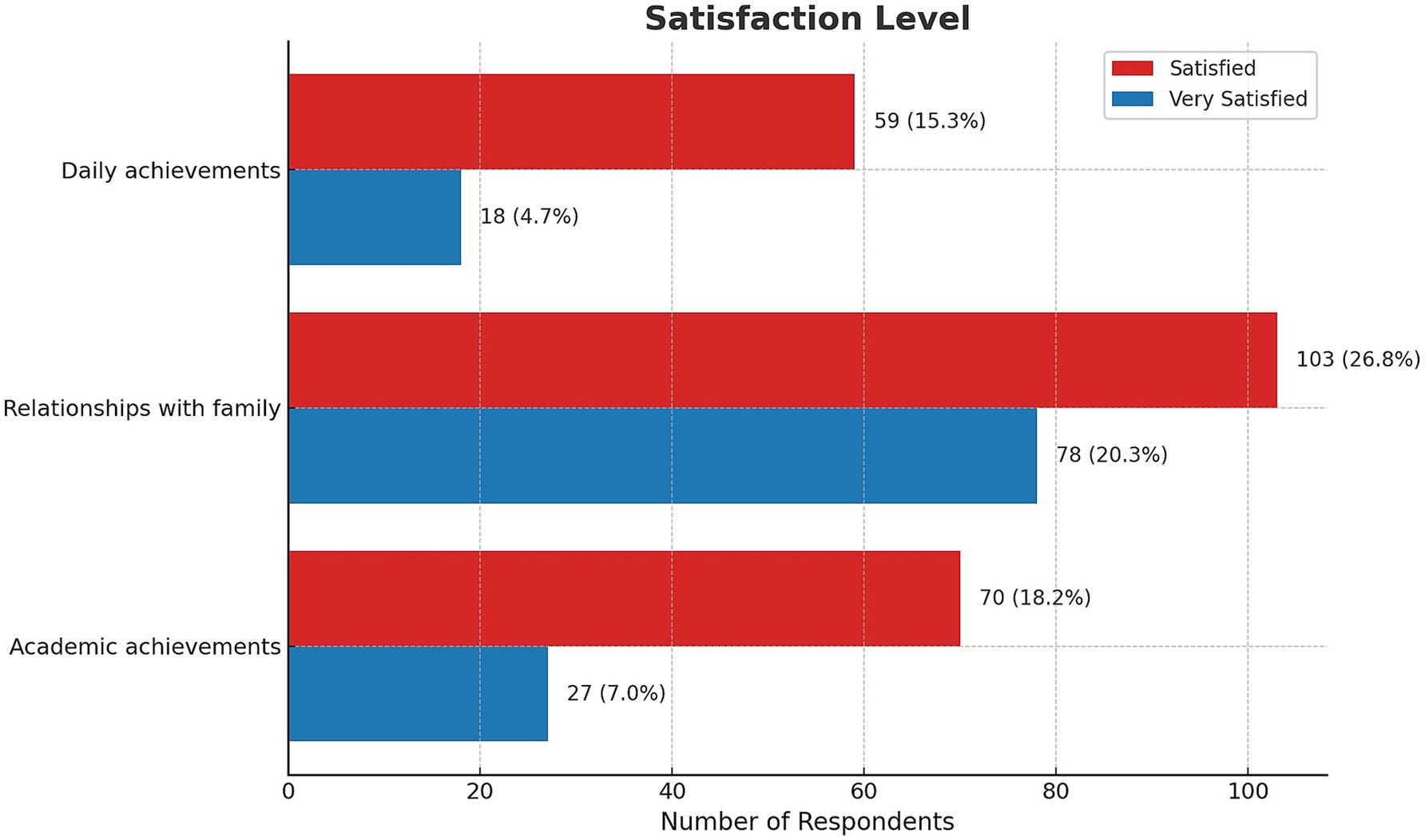

Students were surveyed about their satisfaction with family relationships, daily achievements, and academic performance. While a significant proportion of students expressed satisfaction with their family relationships, satisfaction levels were notably lower in terms of daily achievements and academic performance. This disparity suggests that, despite strengthened family bonds, students faced challenges in meeting personal and academic goals, potentially linked to increased social media use and altered study habits (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Levels of satisfaction with daily achievements, academic performance, and family relationships. Stacked horizontal bar chart showing the number and percentage of students who reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with key life areas. Satisfaction was highest for family relationships, while academic and daily achievements showed comparatively lower satisfaction levels.

4 Discussion

4.1 Increased social media usage during quarantine

This study reveals a significant increase in social media usage among university students after the COVID-19 quarantine, consistent with the observed shifts in academic and social routines. The rise in daily social media usage from 4.55 h to 7.55 h post-quarantine aligns with the increased reliance on digital communication tools for academic purposes, as highlighted in our results. As universities transitioned to remote instruction, students used social media extensively to access course materials, collaborate on projects, and complete assignments. This academic adaptation likely contributed to the observed rise in daily study hours. Furthermore, the prolonged confinement at home, coupled with limited opportunities for outdoor activities, drove students to use social media as a primary outlet for communication and entertainment. This increase in usage reflects the compounding effects of boredom, social isolation, and the need for social interaction under restrictive conditions.

Alternatively, the surge in social media usage during the quarantine period may be attributed not only to boredom and isolation, but also to a combination of psychological stressors and institutional adjustments. Students facing heightened anxiety and uncertainty turned to digital platforms as a coping strategy to seek comfort, distraction, and emotional validation from peers (Prowse et al., 2021). While this behavior may have mitigated psychological strain for some, it also risked reinforcing habits that diverted attention from academic priorities (Michikyan et al., 2023). Additionally, the abrupt shift to online education blurred the lines between recreational and academic screen time, as many institutions began using informal platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook for communication and peer collaboration (Sobaih et al., 2020). These overlapping uses complicated students’ ability to self-regulate their time and focus. Furthermore, recent studies have noted that the academic impact of social media during the pandemic varied depending on how students engaged with these tools—those who used them for emotional support and peer learning often reported positive outcomes (Al Mosharrafa et al., 2024), while others who engaged in passive scrolling or non-academic content experienced declines in performance (Jalal and Tariq, 2023). These insights suggest that increased usage patterns were shaped by a broader context of psychological adaptation, institutional practices, and individual coping styles, offering a more nuanced understanding of their academic consequences.

4.2 Motivations for social media use

The study found that students’ primary motivations for social media use were entertainment and relaxation (52%), followed by social communication (28%). These findings align with prior research, such as Ezeah et al. (2013), who reported similar trends among Nigerian students. The quarantine period appears to have intensified these behaviors, as students sought stress relief and avenues to combat isolation. Our findings reinforce Yang et al. (2022), who observed that social media use during the pandemic provided students with stress relief and a sense of connectedness. Additionally, the use of multiple platforms, a behavior observed in this study, reflects an effort to diversify social interactions and access various forms of entertainment, as each platform offers distinct features.

Regarding platform preferences, Facebook emerged as the most widely used platform among students, consistent with Aljuboori et al. (2020). Facebook’s versatility in facilitating communication and recreational activities likely explains its popularity. However, the findings differ from Alsanie (2015), who identified WhatsApp as the most popular platform in Saudi Arabia, indicating regional and cultural variations in platform preference.

4.3 Impact on academic performance

Our results highlight a nuanced relationship between social media usage and academic performance. While the study observed an increase in both daily social media use and study hours, an inverse relationship between the two was also evident, suggesting that excessive social media use may detract from study time. This finding is consistent with research by Wang et al. (2022), which linked excessive social media use with increased anxiety and depression, potentially undermining academic success. Similarly, Azizi et al. (2022) found that excessive social media use negatively affected academic performance, with sleep quality serving as a mediating factor.

Despite these challenges, social media also played a supportive role in academic activities during quarantine. Students used platforms for educational purposes such as attending online lectures and collaborating on assignments, echoing findings by Hamid et al. (2015), who reported that students perceive social media as a valuable tool for learning. This dual role of social media underscores its potential as both a facilitator and a distraction in academic settings.

4.4 Family relationships and social context

Quarantine conditions appeared to strengthen family relationships among participants, with students reporting increased time spent with family members. This shift is consistent with the socio-cultural norms of Palestinian society, which emphasize family cohesion and interconnectedness (Massad et al., 2016). Shared meals and activities during quarantine likely fostered closer family bonds, providing emotional support amid the challenges of isolation and academic adjustments.

Family dynamics also play a pivotal role in academic resilience, especially in collectivist societies like Palestine, where extended family relationships are central to daily life. Studies from Jordan and Saudi Arabia highlight how students with supportive family environments coped better with the psychological and logistical challenges of distance learning. For example, Jordanian parents widely reported that online learning failed to meet academic expectations due to motivational and infrastructural challenges (Al-Awidi and Al-Mughrabi, 2022), while Saudi students with strong family support reported lower stress and better learning outcomes (Alghamdi et al., 2022). These findings align with the present study’s observation of improved family relationships during quarantine and suggest that familial cohesion in Arab contexts may buffer the negative effects of increased screen time and remote learning pressures.

This phenomenon is not unique to Palestine. In fact, studies across the Middle East have shown that cultural norms around family cohesion, gender roles, and collectivism significantly shape students’ digital engagement and educational experiences during crises. For example, in Saudi Arabia’s highly collectivist society, female students described their families as a crucial support network that helped them cope with the social isolation and anxiety of online learning under lockdown (Winkel et al., 2023). In contrast, a Jordanian study revealed that traditional gender roles left women carrying greater household duties during quarantine limiting their study time and heightening stress while families tended to prioritize and support the online studies of sons, reflecting expectations that males will be future providers (Idris et al., 2023). Tellingly, the same study found that when female students turned to social media for stress relief, they experienced more negative impacts on their grades and mental well-being than did their male peers (Idris et al., 2023), highlighting a gendered difference in digital coping strategies. Similar patterns were observed in neighboring countries.

Approximately 48.3% of participants expressed satisfaction with their family relationships, reflecting the cultural emphasis on family cohesion. These findings align with Elmer et al. (2020), who highlighted the protective role of strong family relationships during lockdowns, mitigating negative mental health outcomes. The increased interaction with family members likely provided a counterbalance to the stress associated with academic and social disruptions, underscoring the resilience fostered by family cohesion in Palestinian culture.

4.5 Global perspectives on social media use

Our findings contribute to the broader understanding of social media use among university students, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Regional comparisons reveal significant variations in social media usage rates and dependency. For instance, Alimoradi et al. (2019) reported social media addiction rates ranging from 0.9 to 37.9% in Asia, 0.3 to 8.1% in the United States, and 2 to 18.3% in Europe. These differences may be attributed to cultural, social, and technological factors, as well as varying attitudes toward digital engagement.

In the context of Palestinian university students, increased social media usage was primarily driven by academic obligations and the need for social interaction under quarantine restrictions. The elevated usage rates observed in this study highlight the potential for social media dependency, particularly when academic and social needs converge in digital spaces.

4.6 Study limitations and future research

While this study offers meaningful insights into the impact of COVID-19 quarantine on university students’ social media use, academic performance, and family dynamics, several limitations should be acknowledged to contextualize the findings. First, the use of a cross-sectional design with convenience sampling restricts the generalizability of the results. Participants were self-selected and recruited online, which may have excluded students with limited internet access or lower digital literacy factors particularly relevant in the West Bank context. As such, the sample may not fully represent the broader population of Palestinian university students in terms of demographic diversity, academic backgrounds, or socioeconomic status.

Moreover, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, including recall inaccuracies, social desirability effects, and subjective interpretation of questions. While the questionnaire was carefully structured to enhance clarity and internal consistency, the absence of validated psychometric instruments may limit the precision of constructs such as academic satisfaction or perceived family closeness. The cross-sectional nature of the study also precludes any determination of causality, as observed associations between social media use and academic or social outcomes may be influenced by unmeasured confounding variables.

Future research should address current methodological constraints by employing more rigorous designs that improve both validity and generalizability. Utilizing random or stratified sampling techniques would help capture a more representative cross-section of the student population, while objective metrics such as screen time logs, academic records, or digital platform usage data could reduce reliance on self-reported behaviors. Additionally, longitudinal studies are essential to better understand how digital engagement evolves over time and how it affects academic trajectories, mental health, and social relationships across different phases of university life.

Building on these findings, future studies should also evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at promoting healthier digital behaviors. In particular, digital wellness programs integrated into university curricula can equip students with self-regulated learning strategies and time management skills to reduce distractions and improve academic focus (Dontre, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Universities in Palestine and the wider region should also consider implementing institutional practices that support digital balance such as encouraging screen breaks, adopting hybrid learning models, and enhancing virtual student support services (Al-Kumaim et al., 2021). These measures not only address the cognitive overload associated with prolonged online engagement but also foster a more sustainable and engaging learning environment.

At the policy level, leveraging digital platforms to enhance both academic and social support structures is crucial. Initiatives such as virtual peer tutoring, collaborative platforms, and family-inclusive outreach programs can reinforce learning outcomes while maintaining emotional resilience. Strong family cohesion, a hallmark of Arab societies, has been shown to buffer the negative effects of excessive digital use and to support academic persistence (Zhu et al., 2022; Lian et al., 2023). Engaging families through digital orientation workshops or institutional communication portals may therefore amplify the benefits of online learning. Finally, expanding research across various regions in Palestine and the broader Arab world will allow for culturally grounded comparisons and more nuanced insights into how infrastructure, social norms, and educational practices shape digital learning experiences in diverse settings.

5 Conclusion

Social media use increased dramatically during COVID-19, as observed among university students in the West Bank. This study explored their motivations for social media engagement, the effects of the quarantine on usage patterns, and the impact on academic performance and family relationships. The findings revealed a substantial rise in social media activity post-quarantine, driven primarily by motivations for entertainment (52%) and social communication (28%). This increased engagement coincided with an uptick in daily study hours, reflecting the dual role of social media in facilitating academic adaptation while potentially distracting from focused study.

Quarantine conditions also appeared to strengthen family relationships, as students reported spending more time with family due to lockdown measures. Despite this positive social outcome, students expressed lower satisfaction with academic performance and daily achievements, highlighting the challenges of balancing increased digital engagement with academic productivity and personal goals.

While this study offers valuable insights, limitations such as convenience sampling, reliance on self-reported data, and a cross-sectional design limit the generalizability and causal interpretation of the findings. Future research should address these constraints using longitudinal methods and larger, more diverse samples to explore the long-term effects of increased social media use on academic and social outcomes. Understanding these dynamics can guide stakeholders in promoting balanced and constructive social media use that enhances both academic success and personal well-being.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee (REC) Al-Quds University Jerusalem, State of Palestine. For further inquiries or correspondence, you can reach the committee at cmVzZWFyY2hAYWRtaW4uYWxxdWRzLmVkdQ==. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

SD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ND: Validation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AA: Formal analysis, Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. In this study, the writing process involved a structured approach to ensure high-quality, reader-friendly documentation. Initially, the manuscript was drafted based on the research findings, laying the foundation for the content. Subsequently, generative AI tools were employed to enhance the text by identifying and correcting grammatical errors, improving sentence structures for better readability, and suggesting alternative phrasings to enhance clarity. Finally, the AI-enhanced manuscript underwent a thorough review by professional editors to ensure accuracy, contextual relevance, and adherence to publication standards, thereby balancing technological efficiency with expert oversight.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1532416/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmed, M. I., Mustaffa, C. S., and Abdul Rani, N. S. (2020). Responding to COVID-19 via online learning: the relationship between Facebook intensity, community factors with social capital and academic performance. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 17, 779–806.

Al Mosharrafa, R., Hossain, M. S., Rahman, M. H., and Rahman, M. A. (2024). Impact of social media usage on academic performance of university students: mediating role of mental health under a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Health Sci. Rep. 7:e1788. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.1788

Al-Awidi, H. M., and Al-Mughrabi, A. (2022). Returning to schools after COVID-19: identifying factors of distance learning failure in Jordan from parents’ perspectives. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 12:e202232. doi: 10.30935/ojcmt/12451

Alghamdi, A. A., Alotaibi, A. A., Alsulami, A. H., Alrashidi, R. A., and Alshehri, A. A. (2022). Family support and academic motivation among Saudi university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 11, 4563–4569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250026

Alimoradi, Z., Lin, C. Y., Broström, A., Bülow, P. H., Bajalan, Z., Griffiths, M. D., et al. (2019). Internet addiction and sleep problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 47, 51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.06.004

Aljuboori, A. F., Fashakh, A. M., and Bayat, O. (2020). The impacts of social media on university students in Iraq. Egypt. Inform. J. 21, 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.eij.2019.12.003

Al-Kumaim, N. H., Alhazmi, A. K., Mohammed, F., Gazem, N. A., Shabbir, M. S., and Fazea, Y. (2021). Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ learning life: an integrated conceptual motivational model for sustainable and healthy online learning. Sustain. For. 13:2546. doi: 10.3390/su13052546

Alsanie, S. I. (2015). Social media (Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp) usage and its relationship with university students' contact with their families in Saudi Arabia. Univers. J. Psychol. 3, 69–72. doi: 10.13189/ujp.2015.030302

Alshanqiti, A., Alharbi, O. A., Ismaeel, D. M., and Abuanq, L. (2023). Social media usage and academic performance among medical students in Medina, Saudi Arabia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 14, 1401–1412. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S434150

Al-Shdayfat, N. M. (2018). Undergraduate student nurses' attitudes towards using social media websites: a study from Jordan. Nurse Educ. Today 66, 39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.017

Azizi, S. M., Mahmoudi, M., and Nili, M. (2022). The relationship between social media addiction and academic performance among Iranian students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of sleep quality. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 20, 93–102. doi: 10.1007/s41105-021-00358-1

Bowker, G. (2008). Structures of participation in digital culture. New York, NY: Social Science Research Council.

Dabbagh, N., and Reo, R. (2011). “Back to the future: tracing the roots and learning affordances of social software” in Web 2.0-based e-learning: applying social informatics for tertiary teaching. eds. M. J. W. Lee and C. McLoughlin (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 1–20.

Diotaiuti, P., Valente, G., Mancone, S., Corrado, S., Bellizzi, F., Falese, L., et al. (2023). Effects of cognitive appraisals on perceived self-efficacy and distress during the COVID-19 lockdown: an empirical analysis based on structural equation modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:5294. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20075294

Dontre, A. J. (2021). The influence of technology on academic distraction: a review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 3, 379–390. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.229

Echeburua, E., and de Corral, P. (2010). Addiction to new technologies and to online social networking in young people: a new challenge. Adicciones 22, 91–95.

Ezeah, G. H., Asogwa, C. E., and Obiorah, E. I. (2013). Social media use among students of Universities in South-East Nigeria. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 16, 23–32. doi: 10.9790/0837-1632332

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., and Stadtfeld, C. (2020). ‘Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15, e0236337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Hamid, S., Waycott, J., Kurnia, S., and Chang, S. (2015). Understanding students’ perceptions of the benefits of online social networking use for teaching and learning. Internet High. Educ. 26, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.02.004

Herring, S. C., and Kapidzic, S. (2015). “Teens, gender, and self-presentation in social media” in International encyclopedia of social and behavioral sciences, vol. 2, 1–16.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., and Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Idris, M., Alkhawaja, L., and Ibrahim, H. (2023). Gender disparities among students at Jordanian universities during COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 99:102776. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102776

Jalal, M. T., and Tariq, S. (2023). Academic social media usage, psycho-behavioral responses and academic performance in university students during COVID-19. HNJSS 2, 45–56.

Kuipers, G. (2002). Media culture and internet disaster jokes: bin laden and the attack on the world trade center. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 5, 450–470. doi: 10.1177/1364942002005004296

Lian, S.-L., Cao, X., Xiao, J., Zhu, X.-W., Yang, Y., and Liu, Q.-Q. (2023). Family cohesion and adaptability reduces mobile phone addiction: the mediating and moderating roles of automatic thoughts and peer attachment. Front. Psychol. 14:1122943. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1122943

Marrero, R. J., Carballeira, M., and Hernández-Cabrera, J. A. (2020). Does humor mediate the relationship between positive personality and well-being? The moderating role of gender and health. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 1117–1144. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00121-x

Massad, S., Nieto, F. J., Palta, M., Smith, M., Clark, R., and Thabet, A. A. (2016). Mental health of children in Palestinian kindergartens: resilience and vulnerability. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 21, 174–181. doi: 10.1111/camh.12158

Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., and Dennis, J. (2023). Social connectedness and negative emotion modulation: social media use for coping among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg. Adulthood 11, 1039–1054. doi: 10.1177/21676968231176109

Owusu-Acheaw, M., and Larson, A. G. (2015). Use of social media and its impact on academic performance of tertiary institution students: a study of students of Koforidua polytechnic, Ghana. J. Educ. Pract. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1086371.pdf

Pew Research Center. (2015). Social media usage: 2005–2015. Available online at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/8/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/ (accessed June 24, 2024).

Prowse, R., Sherratt, F., Adams, N., Hearn, J., Woolley, A., and Bradley, L. (2021). Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Front. Psych. 12:650759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650759

Reizer, A., Geffen, L., and Koslowsky, M. (2021). Life under the COVID-19 lockdown: on the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and psychological distress. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 13, 432–437. doi: 10.1037/tra0001012

Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., and Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 3, 133–148. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016

Sebba-Elran, T. (2021). A pandemic of jokes? The Israeli COVID-19 meme and the construction of a collective response to risk. Humor 34, 229–257. doi: 10.1515/humor-2021-0012

Sobaih, A. E. E., Hasanein, A. M., and Abu Elnasr, A. E. (2020). Responses to COVID-19 in higher education: social media usage for sustaining formal academic communication in developing countries. Sustain. For. 12:6520. doi: 10.3390/su12166520

Techrasa. Population: United Nations; U.S. Census Bureau. Mobile: GSMA intelligence (2019). Internet: Internetworldstats; ITU; World Bank; CIA world Factbook; Eurostat; local government bodies and regulatory authorities; Mideastmedia.org; reports in reputable media. Social media: platforms’ self-serve advertising tools; press releases and investor earnings announcements; Arab social media report; Techrasa; Niki Aghaei; rose.Ru.

Tsitsika, A. K., Tzavela, E. C., Janikian, M., Ólafsson, K., Iordache, A., Schoenmakers, T. M., et al. (2014). Online social networking in adolescence: patterns of use in six European countries and links with psychosocial functioning. J. Adolesc. Health 55, 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.010

Wang, C.-H., Salisbury-Glennon, J. D., Dai, Y., Lee, S., and Dong, J. (2022). Empowering college students to decrease digital distraction through the use of self-regulated learning strategies. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 14:ep388. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/12456

Winkel, C., McNally, B., and Aamir, S. (2023). Narratives of crisis: female Saudi students and the COVID-19 pandemic. Illn. Crisis Loss 31, 4–22. doi: 10.1177/10541373211029079

Yang, S., Liu, Y., and Wei, Z. (2022). Social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic: effects on academic performance and wellbeing among college students. Front. Psychol. 13:839378. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.890317

Keywords: social media use, university students, academic performance, family dynamics, COVID-19

Citation: Deeb S, Alfrookh MH, Zurayqi AK, Dweik YF, Dabash MR, Deeb N and Amro AM (2025) Navigating the digital shift: a cross-sectional study on social media usage, academic performance, and family dynamics among university students in Palestine during COVID-19 quarantine. Front. Educ. 10:1532416. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1532416

Edited by:

Wahyu Rahardjo, Gunadarma University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Maura Pilotti, Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University, Saudi ArabiaMuh Barid Nizarudin Wajdi, STAI Miftahul Ula, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Deeb, Alfrookh, Zurayqi, Dweik, Dabash, Deeb and Amro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Salahaldeen Deeb, c2FsYWhkZWViMjAwMUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Salahaldeen Deeb

Salahaldeen Deeb Mohammad Harbi Alfrookh

Mohammad Harbi Alfrookh Anas Khaled Zurayqi

Anas Khaled Zurayqi