- Quality Management and Mechanical Engineering (KMT), Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden

Introduction: Education has become a complex and unpredictable landscape, creating a need for a paradigm shift in school leadership from deficit-based “firefighting” to designing new, strengths-based approaches that can effectively address emerging challenges in modern educational environments.

Methods: This qualitative exploratory study introduces a Strengths-Based Inquiry System (S-BIS), designed to identify attractive quality indicators through appreciative inquiry questioning. The model aims to help school leaders foster a culture of responsiveness within their schools.

Results: The study examines the application of a strengths-based methodology to understand how Attractive Quality (AQ), Appreciative Inquiry (AI), and the creation of positive customer affect, through appreciative thinking, can support school leaders in developing more responsive approaches to leading schools as living systems.

Discussion: Findings suggest that this integrated strengths-based approach offers school leaders an effective method for shifting from static, deficit-oriented mindsets to more dynamic, appreciative, and regenerative ways of thinking, critical for navigating the complexities inherent in leading schools as adaptive, living systems.

1 Introduction

Change is everywhere; the future is unpredictable, and turbulence rather than stability characterizes the environment in which school leaders lead (Morrison, 2002). So much so that Collins (2022) named the term, permacrisis, its 2022 word of the year which can be defined as an extended period of instability and insecurity, especially one resulting from a series of catastrophic events. With so much instability all around, crisis is a permanent state of being and we need to learn to develop and be responsive to changing conditions to find equilibrium in life. Causon (2022) believes that if we are to weather the economic pressures ahead, and emerge from this feeling of “permacrisis”, we need our leaders to remain focused on driving a long-term vision and not to lose sight of our innovative and entrepreneurial spirit. Over the last decade, product quality is substituted by service quality as one of the most crucial drivers for customer satisfaction throughout industries and societal sectors, suggesting a need for new principles, practices and tools to enhance internal customer centricity and strengthen satisfaction and loyalty (Hallencreutz and Parmler, 2021). This state of being highlights a fundamental challenge educational leaders worldwide must face.

Researchers now suggest the need for new approaches to leading schools as living systems (Snyder and Snyder, 2021) to become responsive to the complex needs of students, community and society. For leaders, this may mean drawing on strengths from responsive leadership, which can be defined as an approach to leadership that encourages leaders, through a relations and strengths orientation, to learn about and engage with stakeholder needs, values, goals, and strengths in order to optimize motivation, stakeholder satisfaction, and overall performance (de Groot, 2015).

To develop responsive leadership for leading schools as living systems, school leaders must change fundamentally from a mechanistic (static) mindset to a more regenerative (dynamic) mindset (Storm and Hutchins, 2019). A regenerative mindset gets to the heart of how we recognize our interdependence with other people, other living beings and ecosystems, and ultimately how we enable all living beings to not simply survive but to thrive together (Payne et al., 2021). This encompasses a shift towards learning from the inherently complex networks of life found in the natural world (Snyder K. M., and Snyder K. J., 2023). This approach contrasts with the current state of leadership in schools in which many leaders are entrenched in a deficit thinking mindset, putting out fires rather than creating the conditions for their teams to thrive (Acker-Hocevar, 2023; Scanga and Sedlack, 2023).

Deficit thinking is a mindset where individuals focus on their limitations, inadequacies, and what they lack, leading to self-doubt, fear of failure and a fixed belief that one’s shortcomings limit growth (Acker-Hocevar, 2023; Anderson, 2023; Scanga and Sedlack, 2023). This mindset can hinder career progression in sales, as individuals tend to shy away from challenges and opportunities that might expose their weaknesses (Anderson, 2023). In this paper the concept of deficit thinking refers to a focus on limitations and problems (Mahone, 2021), and is not to be confused with a common use of the term in education that refers to schools failing low income/minority students. Walker (2020) suggests appreciative thinking, the opposite of depreciative thinking, adds value to a problem or situation and is an approach that individuals can take to grow the value of organizational culture and the collective mindsets within it. Essentially, appreciative thinking represents the mindset that builds on opportunity, strives to learn and grow, and builds on what we want instead of staying focused on what we do not want, thus committing to individual and organizational excellence (ibid).

If we are going to bridge the gap between responsiveness as a key leadership capability and creating schools that thrive as living systems, then new tools, methods, and processes need to be developed for school leaders. This paper explores how the theory of attractive quality (Kano et al., 1984) and a strengths-based approach to organizational development based on appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider and Srivastva, 1987) can be combined to provide school leaders with a new method and process to become more responsive to lead schools as living systems. Some tools exist and are used, but they are not grounded in appreciative thinking which, this study argues, is needed to lead in this age of complexity. Strengths-based tools, such as those promoted by attractive quality and appreciative inquiry may provide new pathways to help leaders shift focus from depreciative thinking to more responsive, appreciative thinking.

The literature on quality management suggests that one of the ways organizational leaders can be more responsive to changing conditions in complex systems is to leverage the theory of attractive quality (AQ) and perceived value as key elements for understanding how to build responsive systems (Johnson, 2021). The original theory of attractive quality says that different attributes of an organization are connected to various patterns of positive and negative customer emotion (Lilja, 2010). Kano et al. (1984) introduced the theory of attractive quality to better explain the roles that different quality attributes play for customers. Perceived quality is the customer’s judgement about a product’s superiority (Zeithaml, 1988). Perceived value is the customer’s benefits (in terms of core solution and additional services) towards sacrifices (in terms of price and relationship costs) (Grönroos, 1997; Samudro et al., 2020).

The concept of perceived value is not commonly used in educational settings in the same way as it is in business. Many schools do not explicitly use the language of “customers” when referring to students, parents, and teachers, as educational leadership often operates within different philosophical frameworks (Snyder et al., 2009). From a quality management perspective, understanding customer perspectives is essential to understand value and attractive quality (Jones, 2018; Kano, 2001; Witell et al., 2013). This suggests that school leaders can benefit from adapting a customer-oriented approaches to enhance stakeholder engagement and responsiveness (Morgan and Murgatroyd, 1994; Snyder et al., 2009). If the language of quality management is used to view these stakeholder groups as the customer, understanding what gives value to them, school leaders might have a better handle on where to divert resources to produce the most value for their customers (Johnson, 2021). This study helps to identify things of value from a stakeholder perspective within a school context thus supporting schools and school leaders to be more responsive. When schools understand this concept of perceived customer value they can open doors to new perspectives, thereby creating the potential for a school to be more responsive to the complex ever-changing conditions it faces daily.

One key feature of the theory of attractive quality is that it includes a methodology that enables organizational leaders to classify and understand the effects of different quality attributes (Witell et al., 2013). The close link between the theory of attractive quality and a method to put the theory into practice – the Kano methodology – makes it essential to understand quality on an attribute level from the customer’s perspective (ibid). When experienced, AQ can be described by customers as exceeding their expectations offering the feelings of surprise and delight (Lilja and Wiklund, 2007). Research has shown that deficit thinking has plagued the decision-making of school leaders (Mahone, 2021). If we look for and examine both the deficits (attributes customers identify as problematic) and the attractors (attributes customers deem high points), leaders have a unique opportunity to see a much fuller picture of their organization’s customer experience to identify and reduce problem areas in schools while simultaneously identifying and amplifying the things that customers actually value.

Similar in nature to AQ, appreciative inquiry (AI) is a method designed to enhance a work environment by focusing on the good, well-functioning parts of an organization and expanding upon them. AI, initially proposed by Cooperrider (1986), is an action-oriented approach to organizational inquiry which is uniquely intended for the study and enhancement of organizational innovation. Appreciative inquiry, combined with methods from attractive quality, may serve school leaders well as an approach to developing a culture of responsiveness within an organization. Combining these theories to produce perspectives on creating value in schools is an original idea yet to be explored and a unique contribution to the literature on school development.

By combining the theory of appreciative inquiry with attractive quality to develop responsiveness, this study examines the S-BIS theoretical-methodological model to assess the effectiveness of this tool to drive innovation and develop new possibilities for building quality within schools. This research tries to understand how attractive quality, appreciative inquiry, and the creation of positive customer affect using divergent thinking can facilitate school’s leaders to develop a more responsiveness approach to leading schools as living systems. The hope is to provide foundational context to a body of research on developing attractive quality and appreciative inquiry in schools by examining a methodological tool that can be used to identify problems and areas of attractiveness by harnessing customer perspectives through their emotions. The tool is designed around three strength-based processes that are integrated in an inquiry system to identify problems and areas of attractiveness by harnessing customer perspectives through their emotions. This study aims to explore how strengths-based leadership approaches, specifically Appreciative Inquiry (AI) and the theory of attractive quality (AQ), can be applied by school leaders. By exploring a Strengths-Based Inquiry System (S-BIS), this research seeks to provide a framework that helps school leaders become more responsive in complex educational environments. The study is guided by two key research questions: (1) What kinds of information emerge from the use of the S-BIS methodology to identify attractive quality indicators? (2) How does engaging in the S-BIS process help school leaders become more responsive in complex systems?

1.1 Background

Diverse needs in schools require diverse solutions, delivered by a diverse cast of community actors far beyond the bounds of our current education system (Lake and Pillow, 2022). This is to say, school leaders need new ideas to meet the growing complexity of educational organizations and the people who stand to benefit from them (Snyder K. M., and Snyder K. J., 2023). In this section of the article, a trifecta of concepts is presented to focus the reader on the core of developing a new mindset for leading schools as living systems in an age of complexity that is based on a strengths-based customer value-oriented approach: (1) responsive leadership in complex adaptive systems, (2) theory of attractive quality, and (3) appreciative inquiry.

1.2 Responsive leadership in complex adaptive systems

Schools are complex systems, not clockworks. Effective school reform and organizational quality are difficult to achieve, and even more challenging to sustain (Ravitch, 2010; Trombly, 2014). Part of that complexity is born out of the reality that schools aim to serve a diverse set of “customers.” For example, they have to meet the needs of their students, teachers, leaders, and families (Center for American Progress, 2010), they are mandated to teach to government defined standards and benchmarks, and they are governed by quality standards (Acker-Hocevar, 2023; Snyder K. M., and Snyder K. J., 2023). Often this complex array of “customers” places conflicting demands on the schools such that leaders are forced to “prioritize.” Moreover, “satisfying” the complex array of customer needs is driven by measurable standards-based indicators, which often ignore the more challenging questions of what adds value to the student and to society.

Educators and educational leaders need support to be responsive and adaptive to the changing landscape that will, in turn, ensure that the youth of today are prepared to lead in a sustainable future (Snyder K. M., and Snyder K. J., 2023). Sir Ken Robinson captures the essence of these challenges:

“We have to go from what is essentially an industrial model of education, a manufacturing model, which is based on linearity and conformity and batching people. We have to move to a model that is based more on principles of agriculture. We have to recognize that human flourishing is not a mechanical process; it’s an organic process. And you cannot predict the outcome of human development. All you can do, like a farmer, is create the conditions under which they will begin to flourish” (Robinson, 2010b).

Leading schools in this day and age is not only about managing operations and meeting the needs of a diverse set of customers, but it also carries the weight of developing value for society. All of this begs the question for school leaders, how do you lead a school today and meet the diverse and complex needs of all stakeholders, while also maintaining accountability and quality? One answer may be to expand quality development beyond standardized measures and provide principals with a pathway to develop a positive school culture (Scanga and Sedlack, 2023) that is responsive to the diverse needs of its customers (including staff, students, parents and society).

Developing responsiveness as the leader and creating a culture of responsiveness within a school is a prerequisite for schools to achieve quality and flourish (Snyder and Snyder, 2021). According to Jenkins-Scott (2020) the concept of responsive leadership focuses on people, the humanity, within the organization to achieve organizational success. Responsive leaders have a deep understanding and appreciation that the people within the organization underpin the organization in both triumph and crisis. There exists four leadership attributes of responsive leaders: (1) curiosity, the desire to continuously learn, (2) empathy, the ability to feel and appreciate other human beings, (3) humility, a sincere regard for the reality that we cannot go it alone, and (4) resilience, the capacity to recover, to keep going forward in the face of adversity (Jenkins-Scott, 2020). Developing the capacity to be more responsive as a leader has its roots deep within the complex systems where schools exist. Painter-Morland (2008) posits that the dynamic environment of a complex adaptive organizational system (such as a school), where it is impossible to anticipate and legislate for every potential circumstantial contingency, creating and sustaining relationships of trust has to be a systemic capacity of the entire organization. It is this nurturing of a culture of trust within a school that becomes the responsive leader’s most valuable asset.

Despite this view, schools and educational leaders remain at cross-roads between two paradigms: one that is based on tradition and one that is called for to support school development. Presently, schools, in general, are guided by a model based on depreciative thinking and we know that impacts decision-making, which can have a long-term negative effect on the quality of schooling.

Many researchers and educational developers are calling for a paradigm shift to embrace complexity and view schools as living systems to truly thrive (Fitzgerald, 2023; Mann, 2023; Snyder K. M., and Snyder K. J., 2023). In complex adaptive system theory, organizations are considered to be constantly changing living organisms where different parts (of very different size and type) are interrelated and change is emergent due to the constant changes of the environments they exist in (Jansson and Virtanen, 2019). The complex adaptive systems approach, introduced by the complexity theory, requires school administrators to develop new skills and strategies to realize their agendas in an ever-changing and complex environment without any expectations of stability and predictability key elements (Fidan and Balcı, 2017). Within a living systems context, organizations are continuously adaptive to changing conditions and the leader’s job is to become responsive to the complex, dynamic nature of change (Allen, 2018; Snyder K. J. and Snyder K. M., 2023). Organizations modeled on living systems is a move away from thinking of the organization as a rigid, reductive, mechanistic hierarchy. Living systems are agile, vibrant, resilient, responsive, innovative, diverse, and regenerative (Storm and Hutchins, 2019).

If we consider the responsiveness of a living system to changes in its environment as its ability to survive and thrive, then we may also consider the responsiveness of a complex school system to changes in its environment as its ability to survive and thrive by reacting quickly and positively. In other words, successful schools need to have the ability to adapt quickly to their ever-changing environments with a certain degree of agility and nimbleness. But how do school leaders embody the concept of being responsive within a complex adaptive system?

Currently, there exists a movement in organizational studies and quality management to explore how to develop organizations from a more positive or convergent perspective (Cooperrider, 1996; Lilja and Eriksson, 2010; Storm and Hutchins, 2019). This approach reflects a shift from depreciative thinking (to focus on problems and solve them based on the way things have always been) to a more appreciative mindset (to focus on possibilities and opportunities by stretching outside of the comfort zone), taking calculated risks, and experimenting (Walker, 2020). Within a school, if we look for and examine both the deficits (attributes customers identify as problematic) and the attractors (attributes customers deem high points), school leaders have a unique opportunity to see a much fuller picture of their organization’s customer experience to identify and reduce problem areas in schools while simultaneously identifying and amplifying the things that customers find highly valuable. Mann (2023) suggests new and experienced school administrators must be prepared properly with this new mindset to find success in the current landscape.

1.3 Leading quality in schools through attractive value

The literature on quality management suggests that one of the ways organizations can be more responsive to changing conditions is to leverage attractive quality and perceived value as key elements for understanding how to build responsive systems (Johnson, 2021). Attractive quality is something customers do not expect. When organizations pre-define unconscious needs, they offer high value to their customers, and the number of loyal customers increases (Kano et al., 1984). Bergman et al. (2022) describes the need for this kind of thinking:

“If we find a product characteristic that fills and unconscious customer need, it may not be that important how well it meets this need—the degree of satisfaction may be quite high anyway. If you succeed in identifying latent customer needs, you might be able to design a product with attractive characteristics that add extra value to the offer and have the potential to create emotions such as surprise, joy, and attraction – emotions that provide energy and value. The difference between failing and succeeding to provide attractive product characteristics might be described as the differences between ‘ok’ and ‘wow!’ This difference is an important factor for competitiveness and success.”

By better understanding the relationships between the concepts of attractive quality (Lilja and Wiklund, 2007) and positive customer affect using divergent thinking, we can begin to explore the application of new methods for leaders to enhance quality in schools and build cultures of responsiveness. Satisfaction is the consumer’s fulfilment response with the degree of pleasant or unpleasant; or rather, satisfaction is the affective output from the cognitive components of evaluation (Oliver, 1996). Perceived quality is a customer’s judgement about a product’s superiority (Zeithaml, 1988), an important latent need in parent school selection for their child. This is different than Perceived value, which can be described as the customer’s benefits (in terms of core solution and additional services) towards sacrifices (in terms of price and relationship costs) (Grönroos, 1997; Samudro et al., 2020). When we use these definitions with school leaders within the complex “product” of education, a mindset shift begins to take place, away from the more traditional methods of leading and evaluating schools towards a more attractive approach to schooling for the stakeholders it serves. Yet, to date, principals are not trained in the notion of customer value in education raising questions about what tools and methods can be developed for school leaders that will allow them to understand and make this proposed mind shift?

According to Kondo (2000) to achieve true customer satisfaction, we must not only achieve must-be quality by eliminating defects and improving processes, but we must also provide our products with attractive qualities. This is to say, school leaders must ensure the more basic “must-be” product features are in place (such as safe environment, good teachers, and ample resources etc.) while also providing attractive features that create the feelings of surprise and delight (such as teachers working towards their PhDs, a state-of-the-art technology lab, or a school’s strategic global partnerships with other schools and organizations worldwide). Takeuchi and Quelch (1983) argue quality should be primarily customer-driven, not technology-driven, production-driven, or competitor-driven. Others believe a company’s ultimate goal is to reduce measures such as customer complaints to zero (Kondo, 2000). The zero complaints approach, while honorable, focuses solely on reducing dissatisfaction, rather than improving satisfaction, two very different strategic methods. Simply eliminating dissatisfaction is not always the same as achieving satisfaction. This perspective is captured in the theory of attractive quality which changes how we think about customer value.

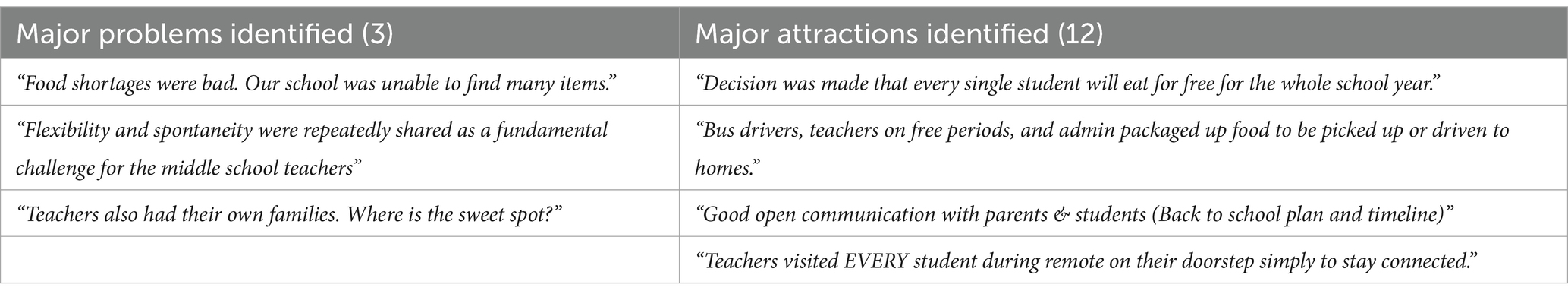

The theory of attractive quality posits five dimensions of perceived quality; attractive quality, one-dimensional quality, must-be quality, indifferent quality, and reverse quality (Ingelsson, 2009; Kano et al., 1984). According to Kano et al. (1984) must-be features, otherwise known as basic features are the basic requirements of a product or service. The absence of these lead to high dissatisfaction. One-dimensional Features often considered as expected features or performance needs lead to a proportional increase in customer satisfaction. Finally, attractive features lead to disproportional increase in customer satisfaction and/or will delight customers. If attractive features within a product or service are not included, it is very possible the customer will not even notice. These attributes are displayed visually with examples in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Common examples of quality features in a school setting & illustration of attractive quality model displaying must-be, one-dimensional, and attractive qualities within fulfilment and satisfaction. Author’s own work inspired by Kano et al. (1984).

This model can be used to understand school customer satisfaction and the overall perceived quality from the customer perspective through its problem detection study methodology. As a method, the theory of attractive quality (Kano et al., 1984) describes the relationship between two aspects; an objective aspect like physical sufficiency and a subjective aspect like customer satisfaction, from a two-dimensional viewpoint based on the philosophers’ ideas such as Aristotle’s and John Locke’s. According to this theory, one can classify the relationship into attractive quality, one-dimensional quality, must-be quality, and indifferent quality (Kano, 2001). Lilja and Wiklund (2007) suggests there are two fundamentally different mechanisms considered essential for the generation of attractive quality. Most attribute the meaning of attractive quality most closely to the concept of exceeding customer expectations and offering the feeling of delight. As central as this idea is to attractive quality, the second mechanism is the satisfaction of high-level needs such as reputation, prestige, and recognition from others (ibid).

Used around the world for decades by many organizations, the problem detection study capitalizes on the psychological fact that humans are more inclined to identify deficiencies than make creative suggestions (ibid). It establishes the types and frequency of key customer problems, which, in turn, allows leaders to prioritize and find solutions to these problems. Problem detection is the process by which people first become concerned that events may be taking an unexpected and undesirable direction that potentially requires action (Klein et al., 2005). The PDS is based on the fact that people are more inclined to identify deficiencies than to make creative suggestions and on the need to focus on customer problems to improve quality (Lilja and Eriksson, 2010). The PDS offers an appealing ability to establish types and frequency of key customer problems, to determine their impact on customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction and use this information to set priorities (Brandt and Reffett, 1989; Lilja and Eriksson, 2010).

Lilja and Eriksson (2010) introduced a conceptual methodological approach called the attraction detection study (ADS) to systematically create attractive quality within organizations. When the PDS and ADS are implemented as complimenting methodologies, they unite to create a value innovation system to drive the innovation of a school in a systematic way based on what students, teachers, staff, and parents actually value (ibid). Research suggests the commonly utilized problem detection study (PDS) methodology only paints half the picture (Lilja and Eriksson, 2010). Conversely, an attraction detection study (ADS) identifies areas within an organization that are going well, working as intended, or unintended feelings of excitement and delight for customers. The potential application of a PDS combined with an ADS may help leaders become more responsive. However, to truly gain access to the deep insights contained within a well-executed PDS & ADS, another strengths-based practice may be needed.

1.4 Appreciative inquiry as a strength based approach

To help school leaders achieve a mind shift from deficit to strengths-based calls for new tools and methods that open up new opportunities and perspectives. One such approach is found in appreciative inquiry, which is a strengths-based approach to support organizational development. Strengths-based approaches focus on individuals’ strengths rather than their deficits. Most performance feedback in organizations is based on a deficit approach in which person’s weaknesses are seen as their greatest opportunity for development (van Woerkom and Kroon, 2020; van Woerkom et al., 2016). However, developments in the field of positive psychology (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; van Woerkom and Kroon, 2020) have inspired practitioners and scholars to promote the benefits of detecting and using individual strengths as a pathway to performance improvement.

Appreciative inquiry (AI) is an approach to organizational development designed to enhance the work environment by focusing on the good, well working parts of the organization and expanding upon them. AI (not to be confused with artificial intelligence) was initially proposed by Cooperrider (1986) and is an action-oriented approach to organizational inquiry which is uniquely intended for the study and enhancement of organizational innovation. AI is an energizing and inclusive process that fosters creativity through the art of positive inquiry, building new skills in individuals and groups, developing new leaders, encouraging a culture of inquiry, and helps create shared vision by building on an organization’s core values and strengths (The Center for Appreciative Inquiry, 2023). A strength-based approach is an organizational development perspective that assumes that all organizations have strengths, focuses on understanding the organization’s strengths, and capturing their capacity to transform an organization (Cooperrider and Whitney, 2005).

AI’s life centric and strengths-based approach to organizational development is replacing a long-standing tradition in schools that focuses primarily on problems. Cooperrider (2021a) suggests that this is critical to help organizations move out of a tradition of deficit thinking. This is often referred to as “deficit thinking” (Patton Davis and Museus, 2019) and is reflected by a culture of blame (Ingelsson et al., 2018) and problem orientation that has left schools stuck in a cycle of firefighting (Snyder K. M. and Snyder K. J., 2023). A strength’s-based approach, such as appreciative inquiry, reframes the deficits and opens doors for change to occur. AI’s life-centric and strengths-based approach, rather than focusing on deficits and framing change as a problem, is replacing many traditional analytic models in business and society (Cooperrider, 2021a). In his original dissertation (Cooperrider, 1986), Cooperrider describes AI as a mode of action research that meets the criteria of science as spelled out in generative-theoretical terms. Essentially, appreciative inquiry fosters organizational growth by tapping into the core motivations, strengths, and values that inspire and energize individuals and that provide an impetus for change (Ruhe et al., 2011). Furthermore, appreciative inquiry focuses on a pre-determined area of organizational need. The appreciative inquiry process fosters positive relationships and builds on the basic goodness in a person, a situation, or an organization to enhance collaboration and change around common goals (Ruhe et al., 2011). AI can be described as a mode of action research that engenders a reverence for life that draws the researcher to inquire beyond superficial appearances to deeper levels of the life-generating essentials and potentials of social existence (Cooperrider, 1996; Cooperrider and Srivastva, 1987).

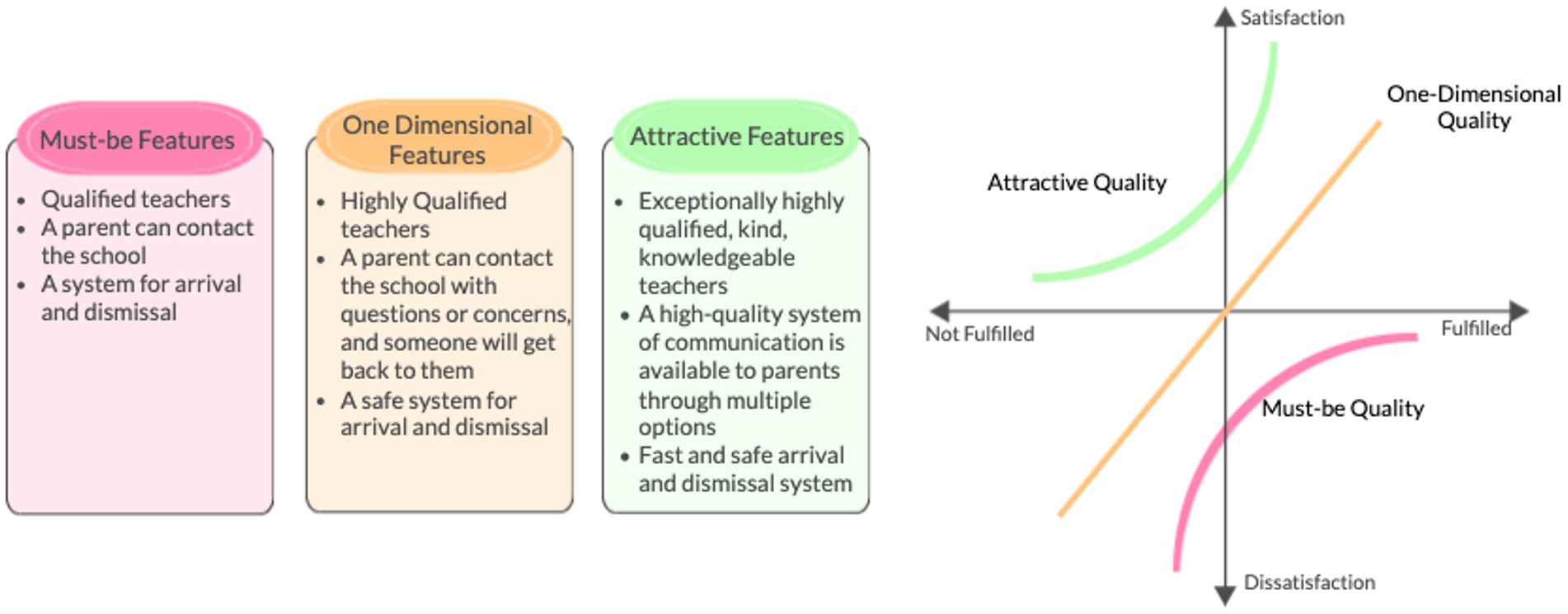

Figure 2 displays a diagram inspired by Cooperrider’s (1985) original 4D cycle that allows an organizations to use a methodology to identify its positive core strengths relative to the affirmative topic. AI has demonstrated that human systems grow in the direction of their persistent inquiries, and this propensity is strongest and most sustainable when the means and ends of inquiry are positively correlated (Cooperrider, 2012).

Figure 2. 5D appreciative inquiry cycle. Author’s own work inspired by Cooperrider (1985).

To understand appreciative inquiry, it is helpful to synthesize the classic 4-D model. Cooperrider (2021b) describes the 4-D cycle as discovery, what gives life, dream, what might be, design, what should be the ideal, and destiny, how to empower, learn, and improvise. This methodology allows an organization to identify its positive core strengths relative to the “affirmative topic” being addressed and initiate concrete organizational steps to achieve its goals (Cooperrider, 2021b). In later years, a fifth element of the model, “define,” was added (also Figure 2) to create the 5-D model (Champlain, 2021). It is important to define the overall focus of the inquiry and what the system wants more of. Definition is used to clarify the area of work to be considered before moving to the discovery stage.

To support exploration and development, appreciative inquiry focuses on asking big questions and using interview techniques to identify high points and strengths in scenarios. This methodology, appreciative inquiry (AI) also offers specific data collection techniques such as AI interview questions. It is about understanding strengths and the positive core of a human system; as such that interview questions are what we ask to discover these strengths (Moore, 2021). It is of interest to note that AI was originally developed as a qualitative research method, therefore, there are no closed questions. Everybody involved in an initiative will be familiarized with AI, as it is largely about co-creation (Moore, 2021).

According to Mann (2022), four types of appreciative inquiry question exist:

1. High point questions.

2. Questions about strength.

3. Questions about future orientation.

4. Questions about values.

High point questions are simply questions about working at our very best. Generally speaking, if you have been able to do it once, then we can do it again (Cooperrider and Whitney, 2005). Strengths based questions revolve around what an organization’s greatest strengths are such as what are the greatest strengths we hold? Future oriented questions, as the name would suggest, encourage participants to look ahead instead of behind. For example, “5 years from now, when we are all working at our very best, and the things we dreamed of are all working successfully…” Questions about values focus on the respondent’s internal core value system and may ask questions like “What do you value the most about….”

1.5 Strengths-based inquiry system—a proposed tool for school leaders

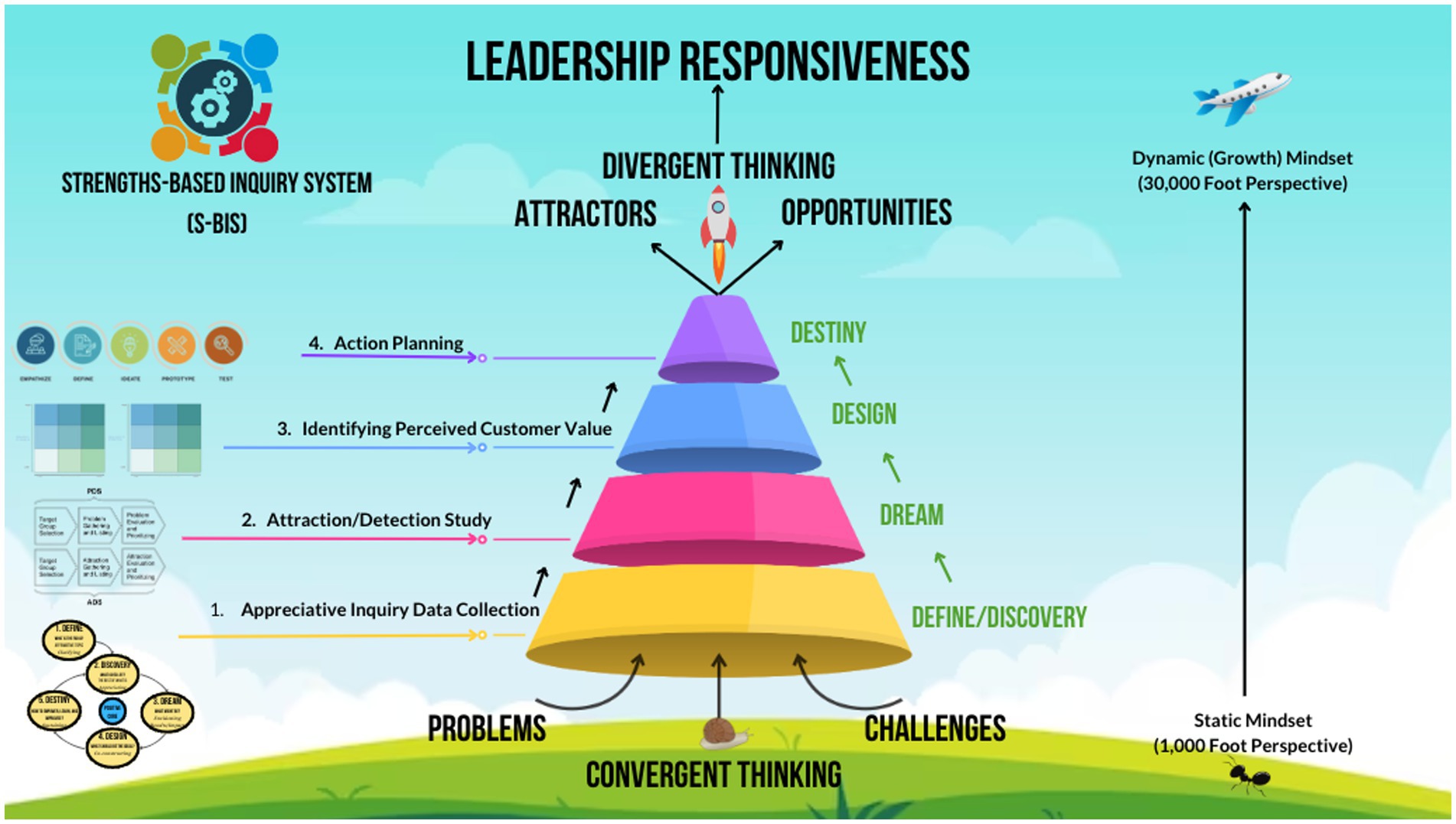

To explore a methodological tool for school leaders to develop responsiveness, methods from AI and AQ are combined into a new model that serves as the focus of this study. Understanding these principles is essential because they form the foundation of the proposed model which this study explores as a practical tool for improving school leadership responsiveness. Combining appreciative inquiry within a problem attraction detection system is a new and original idea which may allow school leaders to unlock new and unexpected value for their schools, helping them become more responsive. To classify attractors requires first asking questions differently (AI) then processing the information gained (problem attraction detection). From here on this process will be referred to as the strengths-based inquiry system (S-BIS) as illustrated in Figure 3. This places the process in a broader context by providing innovative approaches to developing quality in organizations that address the complexity present.

Figure 3. Strengths-based inquiry system (S-BIS) in action. Author’s own work. (1) Appreciative inquiry interview method: employ a strength-based appreciative inquiry interview guide as an interview technique to interview school leaders. (2) Attraction/detection study: use a modified version of the original ADS/PDS methodology to identify problems and attractors then reflect upon what new insights might be identified from the data. (3) Identifying perceived customer value: designate attractors and problems within a structured, weighted matrix framework, identifying high and low value attributes (perceived value). (4) Action planning: design and implement a plan of action using newly acquired perspectives.

The proposed S-BIS tool being examined in this study can be broken down into four separate steps which are summarized below then described in detail in the methods section.

1. Appreciative Inquiry Interview Method: Employ a strength-based appreciative inquiry interview guide as an interview technique to interview school leaders.

2. Attraction/Detection Study: Use a modified version of the original ADS/PDS methodology to identify problems and attractors then reflect upon what new insights might be identified from the data.

3. Identifying Perceived Customer Value: Designate attractors and problems within a structured, weighted matrix framework, identifying high and low value attributes (perceived value).

4. Action Planning: Design and implement a plan of action using newly acquired perspectives.

As discussed, Appreciative Inquiry (AI) and the theory of attractive quality (AQ) offer alternative ways to enhance leadership responsiveness. However, applying these models in schools requires careful adaptation. This study seeks to bridge that gap by exploring this Strengths-Based Inquiry System (S-BIS) to integrate these approaches into a structured methodology for school leaders. By combining the theory of appreciative inquiry with attractive quality to develop responsiveness, this study examines the S-BIS theoretical-methodological model to assess the effectiveness of this tool to drive innovation and develop new possibilities for building quality within schools. This research design also aligns with participatory methodologies, such as design thinking, which emphasizes stakeholder engagement, iterative problem-solving, and co-creation of solutions (Jones, 2018). While not explicitly used as a data collection tool in this study, design thinking principles informed the approach by ensuring that participants were active contributors in identifying challenges and attractors. How this tool might be used practically by school leaders within education will be discussed in the findings section.

2 Methodology

A qualitative exploratory study, using a reflexive lens, was conducted to explore the application of the strengths-based inquiry system (S-BIS) as a new approach to identifying attractors that leaders can use to become more responsive. Reflexivity was present in the study to insure reliability of data. Qualitative researchers engage in reflexivity to account for how subjectivity shapes their inquiry (Olmos-Vega et al., 2023). Reflexivity is tied to the researcher’s ability to make and communicate nuanced and ethical decisions amid the complex work of generating real-world data that reflect the messiness of participants’ experiences and social practices (Finlay, 2002; Olmos-Vega et al., 2023). As a reflexive practitioner and working professional within the education industry with an empathetic relationship with many of the challenges and opportunities shared by other school leaders, it is hoped this level of reflexivity adds to the depth of the data collected in an ethical and meaningful way. This allowed the spirit of the study to have an experimental exploration of the tool as new insights were discovered. It should be noted that this tool is still in early development, such that the data collection techniques used in this version may be significantly different than those employed by school leaders themselves as they use the tool. The basis of the study is to learn as much as possible about how this mindset shift can help school leaders lead more responsively and will guide the development of the final version of the tool in a future study.

2.1 Study design

The study design is a qualitative exploratory experiment to explore the application of the S-BIS model as an effective means to identify attractive quality indicators and generate important insights for school leaders to become more responsive in complex systems. To assess this model, the study followed the three of the four steps in the S-BIS model to explore and examine its usefulness as a tool to support responsiveness among leaders. The final step is intended to be carried out by the school leader and thus was omitted from this portion of the testing. Each of the steps can also be matched with traditional research methods and are provided to make visible the research process that was carried out in this study.

1. Appreciative Inquiry Interview Method (Data collection).

2. Attraction/Detection Study (Data analysis part 1).

3. Identifying perceived customer value (Data analysis part 2).

4. Action planning (Design Thinking & Implementation).

2.2 Sampling

The methodology was tested with four school leaders. To select the participants for this study, the method purposeful sampling was employed. Purposeful sampling is widely used in qualitative research for the identification and selection of information-rich cases related to the phenomenon of interest (Palinkas et al., 2015). The interviewees were selected based on four criteria: (1) More than 5 years’ experience as a school leader; (2) had a master’s degree or higher; (3) Were committed to developing their leadership capacity and responsiveness in schools; and (4) represented both public and private sector. This was a deliberate decision early in the research design to ensure both models were explored, partly due to the different perspectives involved when answering the question, “who do you see as your customers?” Four separate school leaders were chosen from both public and private schools in 2 states in the U.S. Two of the leaders were known to the author, the other two were identified through mutual contacts and were unknown before this study. The interviewees were selected based on their work as school leaders and commitment to explore new ways to lead schools. All interviewees provided their informed consent to be interviewed, recorded, and data utilized for the purposes of research. The identity of each school leader has been protected to ensure the answers to questions were as honest and unbiased as possible. This study utilizes a sample size of four school leaders at four different schools, with different geographical, sociopolitical, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

2.3 Key respondents

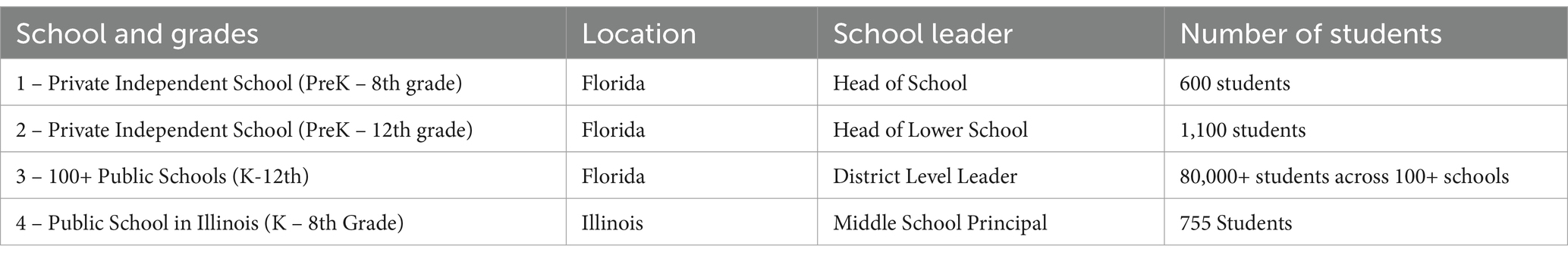

Three out of the four schools selected for data collection in this qualitative exploratory research study are in the State of Florida and the fourth school was in Illinois. School leaders from three schools and one school district were selected for interview. School one is a PreK-3 through 8th grade private, non-sectarian independent school in Florida. The school is known as and dedicated to a hands-on, child-centered philosophy based on best practices in education and knowledge gained from leading-edge brain research to accelerate learning. School two is a PreK – 12th-grade private independent school in Florida well renowned for its modern pedagogical approaches to education. The third school leader interviewed is a high-level district administrator in Florida county who oversees over 100+ schools, 4,500+ teachers, and 80,000+ students. The fourth school leader is a middle school principal at a Kindergarten through 8th-grade public school in Illinois, United States. The schools selected for this study and the school leaders interviewed represent a diverse cross-section of educational institutions, including urban, suburban, and rural settings, as well as public and private models. This diversity was intentional, ensuring that findings were not limited to a single type of school environment to ensure a comprehensive understanding of responsiveness in different schools. Table 1 displays the key differences and demographic information of each school.

2.4 Data collection

Data were collected during the first step of the S-BIS method using appreciative inquiry interviews as a guide. Data were collected through one-to-one interviews with the four principals. The focus of the interviews was to identify high points and attractors that were present in the school from the perspective of the principals. These interviews used the appreciative inquiry interview guide methodology (Cooperrider et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2011) which focuses on the sharing of “peak experiences” and “high points of participants. To ensure reliability and validity, the extra step was taken to consult an expert in the field of applying appreciative inquiry with educational leaders to further refine the AI interview guide before deployment.

The interview guide included a series of carefully curated questions that were designed around the appreciated inquiry 5-D model: (1) define, (2) discover, (3) dream, (4) design, (5) destiny. Examples of questions used, include, can you describe to me who your customers are? How do you define your customers? What do your customers value? What were the factors that you considered to maintain the quality of education at your school? How did your school meet customer expectations during the pandemic? How did your school exceed customer expectations during the pandemic? What do you believe was a leadership experience that was most successful and made you feel engaged or alive? Imagine in 5 years that that your school is exactly where you want it to be. In 5 years, you have accomplished all the things you want to, that everything is working the way that it should. What is it that is occurring? What is it that you are seeing and hearing what is happening in your school?

All interviews for this study were conducted digitally via video conference or in-person and recorded (with permission) using an appreciative inquiry interview guide. Each interviewee was assigned a code, and the audio recording was listened to, and a preliminary analysis conducted as soon after the interview as possible. The author opted not to record the video conference in Zoom and instead rely on software called “Otter” which uses artificial intelligence to create real-time transcription of interviewee dialogue that is shareable, searchable, accessible, and secure. This tool, accompanied by the AI interview guide uploaded into its own page within Microsoft OneNote, allowed the author to take notes on an iPad Pro, highlight segments of live transcribed text, and look for patterns and themes within the data.

2.5 Data analysis

Data were analyzed in three steps; 1. Data segmentation into specific statements, 2. Classify problems and attractors, 3. Identify perceived customer value, and 4. Action planning (not conducted as part of this study since it involves action planning by the principal).

2.5.1 Step 1: Appreciative inquiry data collection

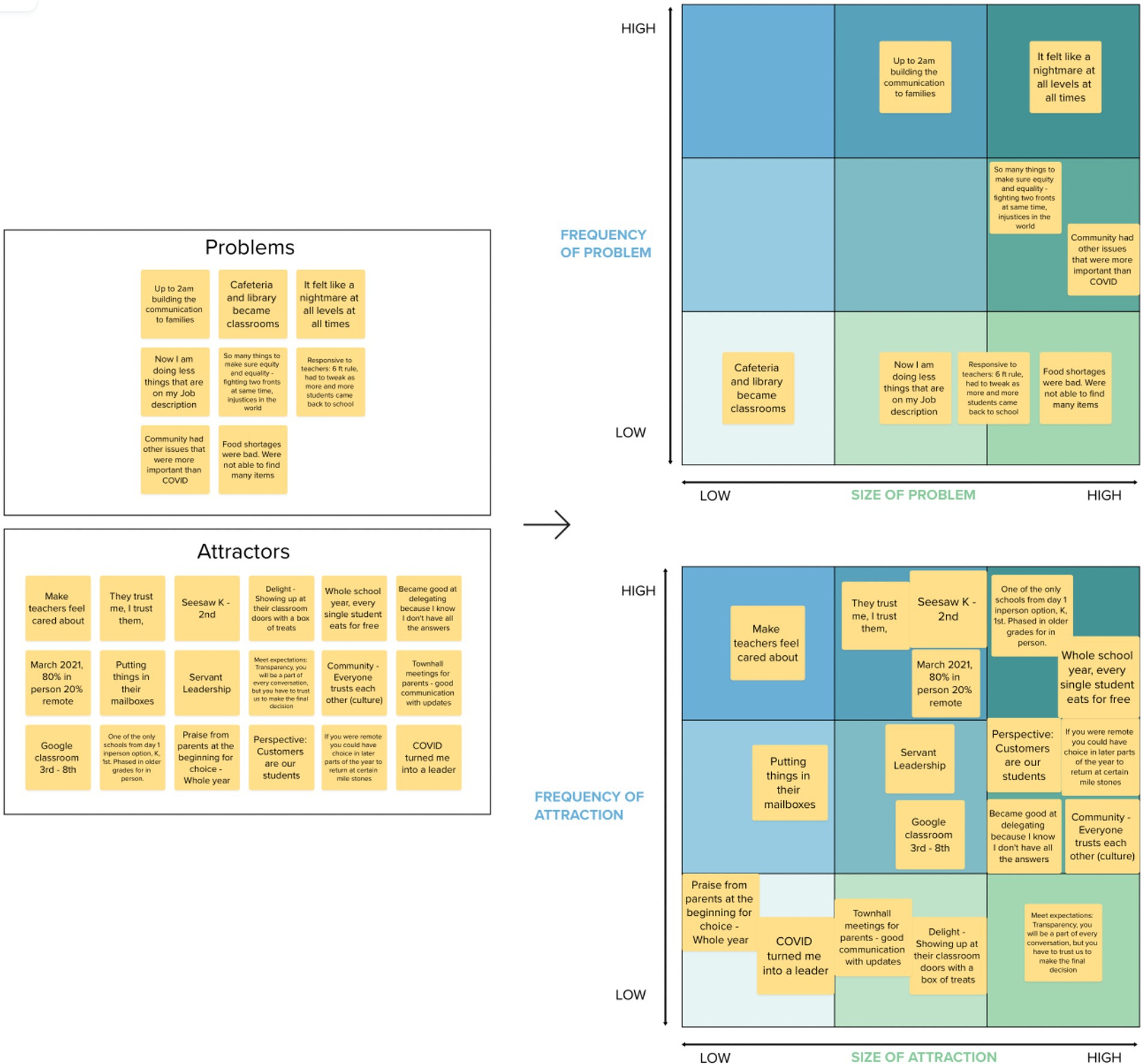

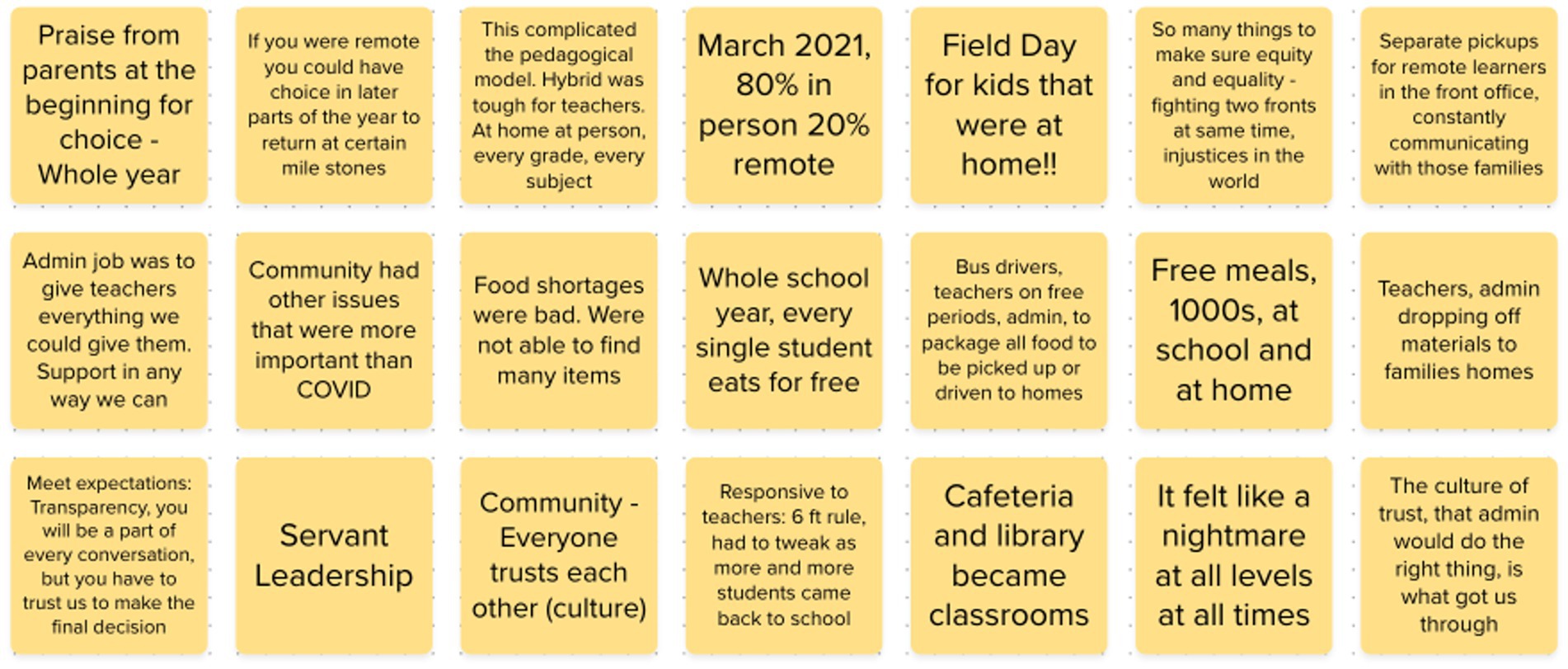

First, transcripts were reviewed and segmented into distinct data points. These segments were then coded inductively, identifying recurring themes related to leadership responsiveness, school challenges, and perceived strengths. To ensure consistency, coding was conducted iteratively, refining themes as new insights emerged. For example, based on the information shared during the interview, one respondent reported that 80% of students we in-person while 20% were remote. This was 1 of 83 statements made over the course of the 45 min interview. Some of the data points are shown as examples in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Some of one respondent’s recorded data points as an example. Transcripts were reviewed and segmented into distinct data points before inductive coding.

2.5.2 Step 2: Attraction/detection study

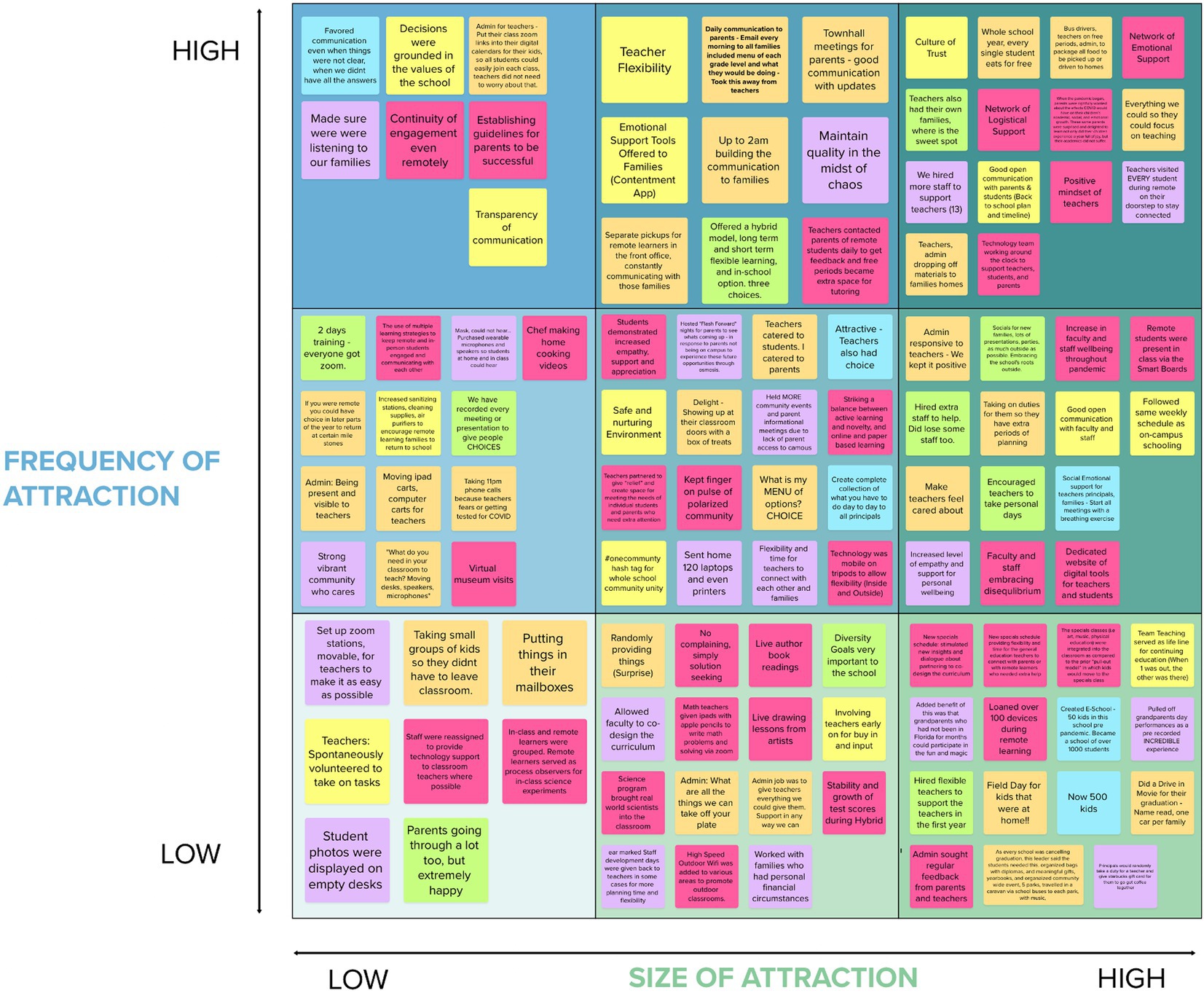

To explore how the process helps school leaders, a second meeting allowed one respondent the opportunity to elaborate on the process. The respondent was asked to take the data points that they deemed problems and move them to the problem detection box leaving behind anything they deemed just as a statement or attractor. Similarly, when they came across something they deemed an attractor, they placed it in the attraction detection box leaving behind everything else. This process ensured only problems and attractors are being evaluated. An example of this can be seen in Figure 5.

2.5.3 Step 3: Identifying perceived customer value

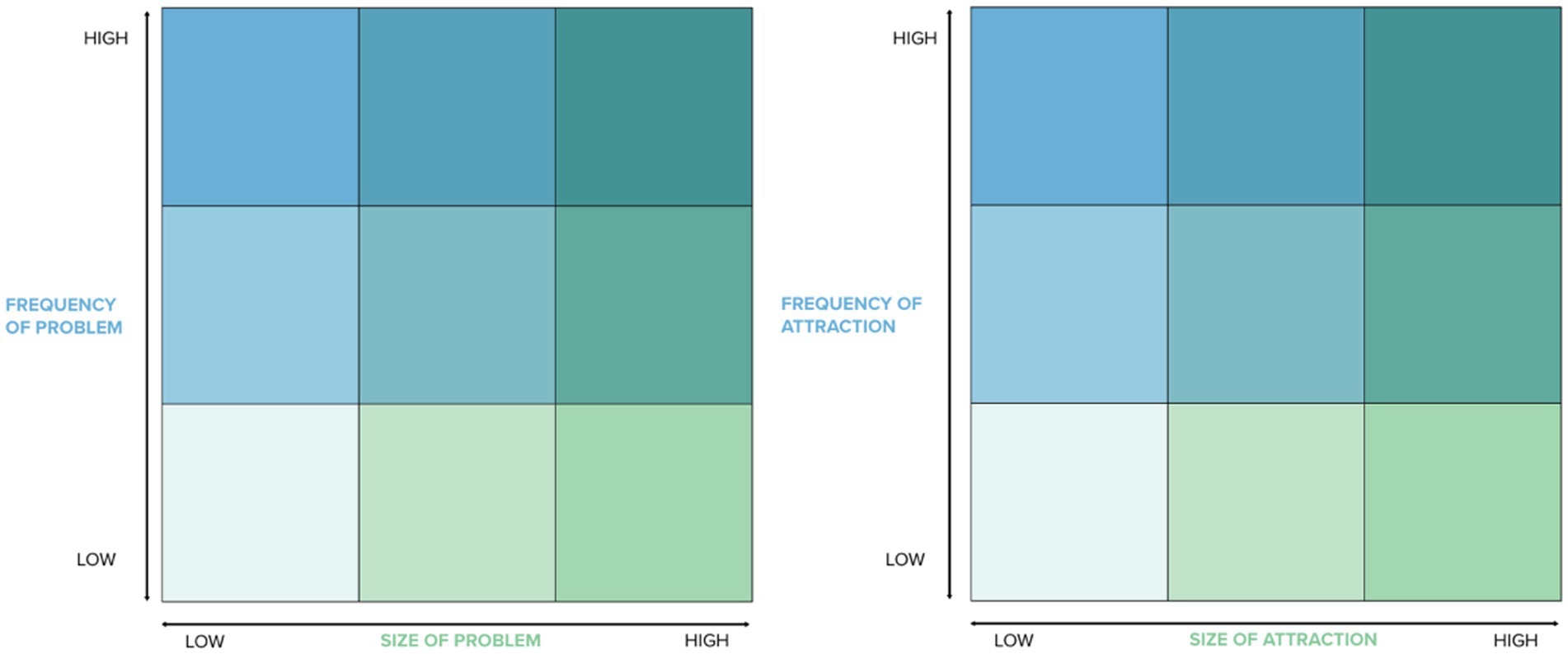

As a first round of data analysis, the author of this study experimented with where respondent data might be placed. In the third step, data transcribed from each data source was mapped out using an online visual digital collaboration tool called Mural.com. The PDS/ADS/VIS framework called for the detected problems and detected attractors to be reduced as much as possible into specific data points. Problems and attractors were classified using a structured matrix based on two key criteria: (1) frequency of mention and (2) perceived significance. Statements were rated on a scale from 0 to 3 based on how often they appeared across interviews and how strongly they impacted stakeholders (students, teachers, parents, administrators). Problems were categorized as “high-priority issues” if they were frequently reported and had a major impact on school operations. Conversely, attractors were classified based on their ability to generate positive stakeholder experiences, with high-scoring attractors representing elements that created unexpected delight or strong engagement.

The matrix for both problem and attraction identification are shown in Figure 6. Each statement was analyzed, and matrix location calculated by asking these same five questions for each identified statement:

1. Who is the customer in this statement (Teachers, students, parents, staff members)?

2. What is the size of the problem or attraction?

3. What is the frequency of the problem or attraction?

4. For problems, was reverse quality experienced?

5. For attractions, was “surprise and delight” experienced?

An example of how a respondent answered these questions is shown in Figure 7. Detected attractors and problems where the moved from the boxes into the matrix based on the criteria listed above.

2.5.4 Step #4: Action planning

This final step is to be experimented with regarding using the gathered data to design using an iterative methodology such as design thinking to fulfil the “destiny” component of appreciative inquiry. What is lacking in substantive design from output is made up for in the rich reflections and take away from respondents in terms of their mind shift from convergent to divergent thinking. This will be designed and tested in a future study.

2.6 Ethical considerations

The methodology reflects the role and position of the author in the schools studied. The author is a school leader (at one of the four schools mentioned in this paper) and a doctoral student examining the phenomenon of attractive quality using a phenomenological methodology. Confidentiality and anonymity were present throughout the study to protect the research subjects as well to encourage less risk in sharing deep insights within their professional positions. The respondents were also informed of the process and scope of the research study and consented for their data to be used. From the beginning of the study there existed the possibility of some subjective bias during the evaluative task of analyzing the statements made by teachers and school leaders. However, the author (a school leader familiar with most of the problems and attractors shared) used the best judgement based on how the interviewees shared the information to place each problem or attractor within the PDS or ADS matrix. Also, the creation of a criteria question set improved any perceived bias.

In order to understand how this tool might work in practice, it should be noted the author used his own role as an experienced school principal and as a reflexive practitioner to reflect upon what new insights might be identified from the data while diligently ensuring reliability and validity of the research study. This was a deliberate methodological choice and was the first example of using the new S-BIS tool to see if new insights and perspectives could be found. These findings are presented in “Findings in relation to RQ1”. As an extra step in this qualitative exploratory process to produce the most accurate findings, it was decided to ask one of the interviewed school leaders to use his own data in the S-BIS tool and to reflect upon “what happened” to him as a principal. This is described in “Findings in relation to RQ2”. In order to ensure the appreciative inquiry interview method would produce valuable data from the four school leaders from different schools, an extra step was taken to consult an expert in the field of applying appreciative inquiry. This process further refined the AI interview guide before deployment to ensure reliability and validity.

3 Results

3.1 Findings in relation to RQ1: What kinds of information emerge from the use of a strengths-based inquiry system to identify attractive quality indicators?

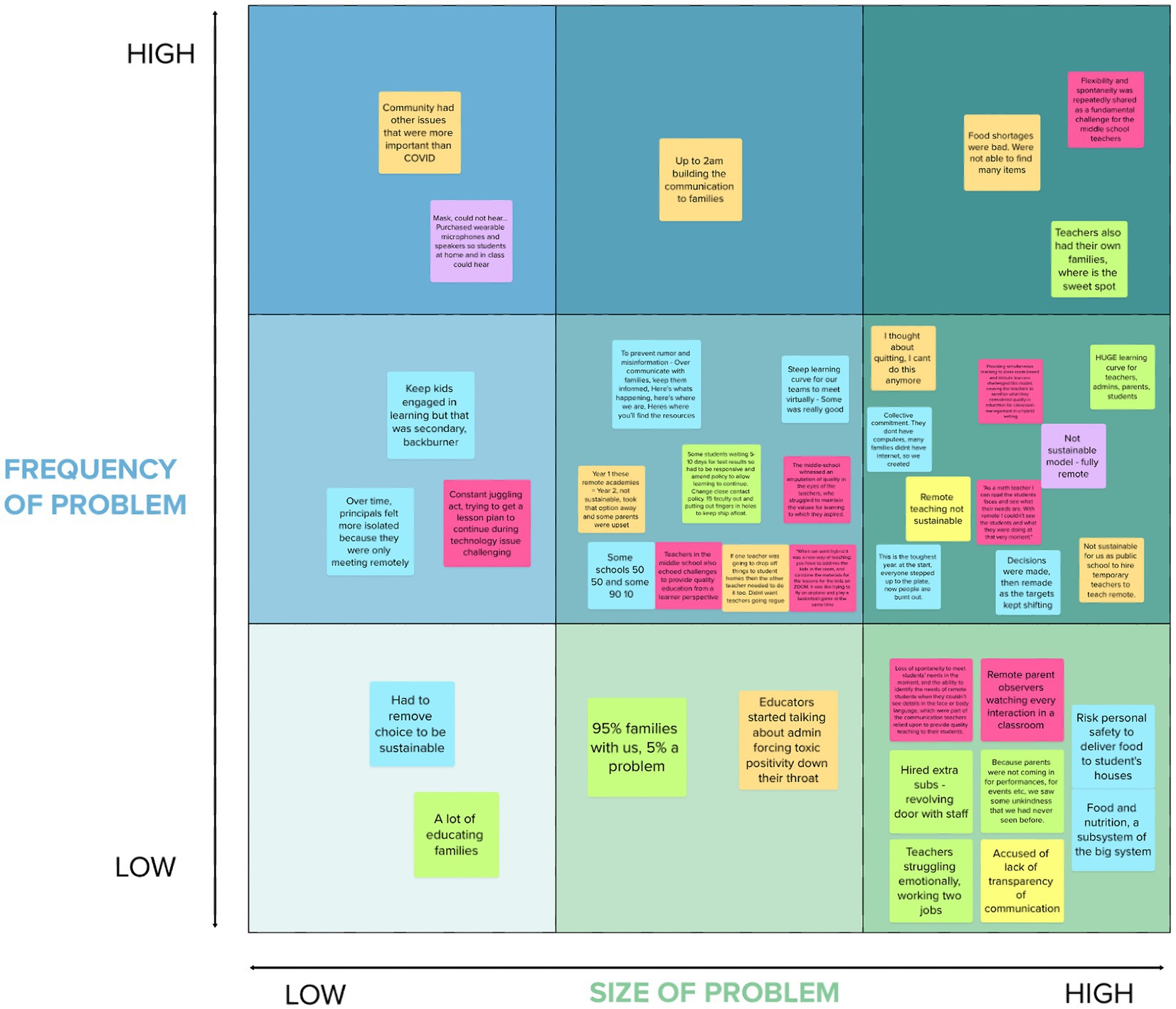

Data from each of the four appreciative inquiry interviews was processed by initially identifying specific problems then placing within the matrix based upon how each respondent talked about them. Figure 8 displays the frequency and size of problems identified by school leaders (Note: The color of each individual data point signifies to the author from which data source it originated from).

Some significant problems were acknowledged and explained during the appreciative interview process. However, in many cases, school leaders described a particular problem, then quickly explained how they jumped into “solution seeking” mode, who they included in those decisions, and how they created customer value by solving these problems. Overall, it was evident that these particular schools were very responsive to issues and challenges, keeping a close ear to the ground and pouncing on each opportunity to solve a problem or improve a situation that needed to be better. For example, one school prides itself on employing positive phrasing in all communications, both internally and externally, on paper, by email, in person, and within all student lessons. This is perceived by the school leader to be very attractive to families within this unique community.

Figure 9 displays the reported attraction points from school leaders. Calculations show that 382 individual statements were collected from interviews and focus groups. 152, or approximately 40% of these statements, were identified as a problem or an attraction point. 40 of these statements identified problems, whereas 112 were identified as attractors, approximately 35 and 65%, respectively. What was immediately noticeable was the frequency of positive attractive quality statements compared to the problems reported. Of particular interest are the high-value problems and attractions, namely, the statements identified as both high frequency and of a large size comparatively.

Table 2 lists the problems and attractions which appeared in the +3 frequency and + 3 size box on both the PDS and ADS (darkest blue/green box in the upper right corner of the matrix).

All four school leaders interviewed had to think deeply before answering the question, “Who are your customers.” The term “customer” was used more often by the two private school leaders who, by definition, have a more traditional pay for service style arrangement. A parent pays tuition in return for a high-quality education for their child. Perhaps understanding perceived value is a language that may be more foreign to some schools simply because they typically do not talk about the customer because they do not necessarily see students, parents, and teachers as customers. However, there was evidence to suggest that engaging in the process of this strength based methodological approach allowed respondents to identify perspectives that they typically were unable to see.

3.2 Findings RQ2: In what ways does engaging with a strengths-based inquiry system help school leaders become more responsive in complex systems?

As a reflexive exercise, one of the previously interviewed school leaders was asked to use his own data in the S-BIS tool and to reflect upon “what happened” to him as a principal. The data gathered from asking this question and allowing the respondent to reflect as they used the S-BIS tool, and the experience provided many meaningful insights.

The respondent reported making significant changes in public schools is challenging due to systemic barriers and pressure to conform to standardized teaching methods. He estimated that approximately 70% of his time is spent problem-solving and 30% being creative. In reference to prioritizing tasks as a school leader, respondent enjoys doing curriculum work as a principal, finding it an attractive and unique experience. He struggles with finding time to focus on what he wants to do, rather than what he has to do and often prioritizes evaluating teachers and managing school operations over spending time in classrooms with students.

The respondent was surprised and excited to be able to see and prioritize identifying both attractors and major problems simultaneously while also discussing how to amplify attractors to improve student and staff experiences. He discussed a shift in focus from solving problems to identifying attractors that brings people together, that would allow his admin team meetings to be more productive and solution oriented. He also highlighted the importance of focusing on things that are pleasing and attractive to others, such as a school’s reputation and community engagement. The process allowed him to remember his “why” for doing what he does, which is to make a positive impact on the lives of teenagers and young adults. He also stated he is passionate about being a trusted adult in the lives of their students and wants to help them become the best versions of themselves.

A lack of progress in areas such as test scores and academics may be due to a reliance on traditional deficit methods and a failure to adapt to changing times which included discussing the importance of student voice in school improvement, with a focus on creating a culture where students feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and concerns. He suggested using surveys and other methods to gather data on student attitudes and experiences but also recognizes the challenges of interpreting and acting on that data.

Overall, he believes a third-party consultant applying this methodological approach could provide valuable insights to a school district by gathering data and giving an unbiased perspective on the school’s culture and climate. He also believes a leader who is willing to change and adapt their style is likely a good leader at the core, as they are able to evolve and improve over time. While reflecting on this process of using the S-BIS tool, the respondent highlighted the importance of asking different questions to uncover new insights and discusses making changes to his leadership approach and decision-making by having the tools to identify and amplify attractors that drive success.

He reported the high-value problems and attractions (+3, +3 in the matrix) should be the most critical areas for his leadership team to focus their attention on. “The most significant problems need to be prioritized for solutions, and the most significant attractors need to be prioritized for perhaps increasing these positive experiences,” the respondent stated. When asked how this might be useful for schools, the respondent answered this approach may give a much more accurate representation of what a school’s students, parents, faculty, and staff actually value instead of assuming what they value. He continued, “these high-value reminders are the post-it notes I need to have stuck next to my computer screen,” meaning it was important for this leader to be reminded of the major challenges and attractors this school’s stakeholders value.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study is to explore the application of a strengths-based methodology to explore and understand how attractive quality, appreciative inquiry, and the creation of positive customer affect using divergent (appreciative) thinking can enable a school leader to develop more responsive approaches to leading schools as living systems. This work contributes to the research on developing attractive quality and appreciative inquiry in schools by examining the development of this methodological tool that can be used to identify problems and areas of attractiveness by harnessing customer perspectives through their positive and negative emotions. The findings suggest that the S-BIS model may help school leaders recognize both challenges and strengths in their schools. This supports the goal of exploring how strengths-based methods can make school leaders more adaptable in complex situations. The findings suggest that using AI and AQ in leadership can offer a fresh approach to improving schools.

By exploring this methodological tool, this study highlighted many examples of where connecting appreciative inquiry and attractive quality can be found to stimulate a mind shift towards becoming more responsive. Experimentally, from a leadership perspective, engaging in S-BIS to see what happens provided an interesting initial set of new insights and perspectives to help school leaders to identify not only the problems but also the strains, determining where gaps may exist while simultaneously identifying possibilities to build on attractive quality. This approach is supported by Lilja and Eriksson (2010) who suggest the need for a more strengths-based approach. This was an important first step in the development of the tool to understand how the data could be coded and classified before asking respondents to do the same.

The literature demonstrates that many school leaders are entrenched in a deficit mindset, putting out fires rather than creating the conditions to thrive (Acker-Hocevar, 2023; Scanga and Sedlack, 2023). The most significant finding in relation to research question 1 was the sheer number of positive attractors reported and coded when compared to identified problems. When questions are asked differently regarding understanding strengths and the positive core of a human system (Moore, 2021), it became evident early on that these leaders reported far more positive experiences, high points, and examples of attractors than problems, indicating the strength of the tool to help shift from deficit thinking to appreciative thinking (Mahone, 2021). The data shows out of all the identified attributes, within the experimental findings, the four school leaders reported 65% attractors compared to 35% problems. As discussed, both play a role and have a purpose, and problems still need solutions. The power in this approach as demonstrated by the data is that when given the opportunity, when questions are asked differently, leaders are energized to provide extraordinary positive insights that naturally push themselves to be responsive (Mann, 2022). In many cases, school leaders described a particular problem, then quickly explained how they jumped into “solution seeking” mode, who they included in those decisions, and how they created customer value by solving these problems. In general, this reflects a phenomenon in schools that happens when good responsive leaders are at the helm. However, it may be a methodological limitation with the appreciative inquiry interview guides that encourages an elevated sense of false positivity.

Overall, the simple act of identifying the +3, +3 problems and attractors, the things of major significance to these school leaders, demonstrated that this methodological approach has definite possibility. The data shows this information and process can be useful to school leaders in a bid to become more responsive by thinking more divergently and opening doors to previously unseen opportunity. However, the actual procedure for deploying this tool in schools including how to identify key internal structures will need further development due to the exploratory nature of this first examination. The findings suggest that a school’s internal structures such as the leadership models present, teacher collaboration frameworks, and level of student engagement plays a crucial role in shaping responsive leadership. The schools with more collaborative cultures and more shared decision making appeared more agile in addressing challenges and amplifying strengths. This aligns with previous research on complex adaptive systems which emphasizes the importance of flexible and interconnected organizational structures in navigating uncertainty (Turner et al., 2018). To cultivate responsiveness leaders for leading schools as living systems, this approach shows promise to help school leaders change fundamentally from a mechanistic (static) mindset to a more regenerative (dynamic) mindset.

There are of course some potential limitations when strategies in the business world are transferred into education. Strengths-based approaches like appreciative inquiry (AI) and the theory of attractive quality (AQ) have worked well in business and service industries but applying them to education can come with challenges. Most schools (especially public) follow strict policies that focus on standardized results which makes it harder for leaders to try new methods. Also, some educators may push back against the idea of seeing students, parents, and teachers as “customers” since they view education as a shared public responsibility, not a business. Because of these factors, while the S-BIS model provides useful ideas, it needs to be adjusted to fit the unique demands of each school and the school leadership within it.

5 Conclusions and future research

What do we now know from this exploratory experiment? This qualitative exploratory research study set out to discover the nexus between attractive quality and appreciative inquiry in an attempt to help school leaders move closer to the kind of responsive mindset shift needed to lead complex organizations. Despite the popularity of appreciative inquiry as a tool for fostering organizational growth by tapping into the core motivations, strengths, and values, this study is—to the best of the authors knowledge—the first to conceptually propose and test its association with attractive quality to promote responsiveness, especially within education. To become a more responsive leader within a school, one must shift from thinking depreciatively to thinking appreciatively which may open doors to new opportunities for creating value for customers.

One important question raised from this study is how school leaders understand the concept of perceived value. When teachers, school admin teams, and staff can think appreciatively about its customer’s benefits (in terms of core solution and additional services) towards sacrifices (in terms of price and relationship costs), a clearer relationship between the daily “work” within a school and perceived customer value is realized. By engaging with the S-BIS (2010) methodology school leaders are guided to consider customer value from the customers perspective, a viewpoint very often missing within school buildings. If the language of quality management is used to view these stakeholder groups as the customer, understanding what gives value to them, school leaders and those they lead may have a better handle on where to divert resources to produce the most value for their faculty, staff, students, and parents. S-BIS helps to identify areas of value within a school context thus supporting schools and school leaders to be more responsive to the needs of its stakeholders. The addition of appreciative inquiry into the S-BIS model puts focus on what leaders want to happen in their schools, or what they want more of. The framing of the AI interview questions was a crucial and much needed formulation for the discovery of attractive quality within the complex systems of the schools included in this study. When schools understand the concept of perceived customer value they may begin to open doors to new perspectives, thereby creating the potential for a school to be more responsive to the complex ever-changing conditions it faces daily.

In summary, this study makes a theoretical argument for the need for another way of thinking in schools, beginning by introducing core concepts in quality management such as perceived quality, what customers find attractive, and their ability to become more agile and responsive within the natural complexity found in schools. It is of particular interest to the author as to what came from the richness of dialogue between the participants and the interviewer. As the literature on quality management suggests, dialogue is an integral part of the process and journey of identifying areas of challenge and attractiveness. In the future, involving more stakeholders such as teachers, parents, and even students in this practice can create unrealized value alongside the data contained in the final action planning step of the S-BIS method. The use of an appreciative inquiry interview guide sought positive dialogue about each leader’s high points and peak experiences. Choosing this methodology contributed to the richness of dialogue between researcher and participant, offering additional opportunities for the attraction points to be identified, celebrated, and the possibility of being amplified.

A future study might examine how to involve key stakeholders in the process through the strategic use of the design thinking methodology, step 4 of the S-BIS model and not tested in this particular paper. What might happen when teachers, staff members, parents, and even students elevate the empathy stage of design thinking as part of a strategic planning or action planning process? This subsequent study aims to apply this concept in a prototype format, designed around leveraging attractive quality for customer value creation and greater long-term sustainability of schools worldwide. Another extension of this study might examine methods of not only identifying attractors but then amplifying those attractors elsewhere in a school. For example, if an attractor is effective in one context, could it be equally effective elsewhere? What methodological process might help schools elevate perceived customer value by proactively amplifying attraction, thus becoming more responsive?

What could schools become by leaning into strength-based approaches to leading and thinking? The literature has shown again and again that deficit (depreciative) thinking has plagued the decision making of school leaders. This new and unique approach offers something innovative and is needed if leaders are to lead schools as complex living systems. Creating more positive customer affect using divergent (appreciative) thinking is possible using this tool since more opportunities for feelings of unexpected surprise and delight exist for customers when school leaders prioritize identifying attractive quality within schools rather than simply putting our fires all day, every day. At a higher level, this research contribution raises fundamental questions about how we can use attractive quality as a concept to develop more sustainable systems in education which may reduce leadership and faculty burnout. School leaders make decisions for their schools’ long-term prosperity and sustainability based on the data streams they have available to them, and this study has demonstrated there are untapped data resources within schools to help them not only survive but thrive.

If we are to weather the feeling of “permacrisis” school leaders need to remain steadfastly focused on driving a long-term vision and not lose sight of their innovative and entrepreneurial spirit. As stated by one of the respondents, simply having those identified high value attractors posted on his desk to be inspired by daily is a good step in the right direction. To develop more responsive leaders for leading schools as living systems, school leaders must shift fundamentally from the more conventional mechanistic (static) mindset to a more regenerative (dynamic) mindset. The best schools are continuously adaptive to changing conditions and their leader’s job is to stay responsive to the complex, dynamic nature of change. As Sir Ken Robinson (2010a), human flourishing is an organic process, not mechanical, and the school leader, like a farmer, needs to create the conditions necessary for everyone within their school community to flourish.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Mid Sweden University and conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their involvement in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acker-Hocevar, M. (2023). “Leadership preparation for sustainable schooling” in Regenerating education as a living system: Success stories of systems thinking in action. eds. K. M. Snyder and K. J. Snyder (London, UK: Rowman and Littlefield).

Allen, K. E. (2018). Leading from the roots: nature-inspired leadership lessons for Today's world. New York, NY: Morgan James Publishing.

Anderson, C. (2023). Deficit thinking vs. appreciative thinking. Open Immersive Reader. Available online at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/deficit-thinking-vs-appreciative-charles-anderson-tqgre/ (Accessed November 22, 2023).

Bergman, B., Backstrom, I., Garvare, R., and Klefsjo, B. (2022). Quality: from customer needs to customer satisfaction. 4th Edn. Lund, Sweden: Studebtlitteratur.

Brandt, R. D., and Reffett, K. L. (1989). Focusing on customer problems to improve service quality. J. Serv. Mark. 3, 5–14. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000002495

Causon, J. (2022). Maintaining focus on the long-term is the only way out of the “permacrisis”. The Institute of Customer Service. Available online at: https://www.instituteofcustomerservice.com/maintaing-focus-on-the-long-term-is-the-only-way-out-of-the-permacrisis/ (Accessed March 4, 2023).

Center for American Progress. (2010). Transforming schools to meet the needs of students. Available online at: https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2010/02/pdf/elt_policy_brief.pdf?_ga=2.105769603.1408125379.1696008901-196745257.1696008901 (Accessed February 8, 2023).

Champlain. (2021). 5-D cycle of appreciative inquiry. Champlain College: Center for Appreciative Inquiry. Available online at: https://appreciativeinquiry.champlain.edu/learn/appreciative-inquiry-introduction/5-d-cycle-appreciative-inquiry/ (Accessed June 25, 2023).

Collins. (2022). Definition of “permacrisis”. Available online at: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/permacrisis (Accessed January 4, 2023).

Cooperrider, D. (1985). Appreciative inquiry: toward a methodology for understanding and enhancing organizational innovation. [Doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University]. PQDT Open. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/b3ea224c6add08e0400088f67d8f9f40/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pqorigsite=gscholar

Cooperrider, D. (1986). Appreciative inquiry: toward a methodology for understanding and enhancing organizational innovation. [Doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University]. PQDT Open. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/b3ea224c6add08e0400088f67d8f9f40/1?cbl=18750&diss=y&pqorigsite=gscholar

Cooperrider, D. (1996). Appreciative inquiry: releasing the power of the positive question. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University.

Cooperrider, D. (2012). What is appreciative inquiry? Available online at: https://www.davidcooperrider.com/ai-process/ (Accessed April 18, 2023).

Cooperrider, D. (2021a). Appreciative inquiry: toward a methodology for understanding and enhancing organizational innovation. AI Commons. Available online at: https://appreciativeinquiry.champlain.edu/educational-material/appreciative-inquiry-toward-methodology-understanding-enhancing-organizational-innovation/ (Accessed April 18, 2023).

Cooperrider, D. (2021b). What is appreciative inquiry? Available online at: https://www.davidcooperrider.com/ai-process/ (Accessed May 6, 2023).

Cooperrider, D., and Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Cooperrider, D. L., Stavros, J. M., and Whitney, D. (2008). The appreciative inquiry handbook: for leaders of change. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cooperrider, D., and Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change. Ed. S. Pink. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. 87.

de Groot, S. (2015). Responsive leadership in social services: A practical approach for optimizing engagement and performance. SAGE Publications, Inc. Available online at: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/responsive-leadership-in-social-services/book241222 (Accessed March 21, 2023).

Fidan, T., and Balcı, A. (2017). Managing schools as complex adaptive systems: a strategic perspective. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 10, 11–26. doi: 10.26822/iejee.2017131883