- 1IPSS Team, Computer Science Laboratory, Faculty of Science, Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco

- 2Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco

- 3Regional Center for Education and Training Professions Souss-Massa, Agadir, Morocco

Introduction: Gender disparities and stereotypes persist in Moroccan schools, influenced by cultural, religious, and political factors. This study examines the integration of Gender Pedagogical Practices (GPPs) to address these issues and foster inclusive, equitable education.

Methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted with 188 teacher trainees at the Teacher Training Center in Souss-Massa (Morocco). The data were collected through a survey on gender knowledge, implementation, and attitudes, classroom observations of 60 trainees, and an interview with a pedagogical actor.

Results: Moderate awareness of gender concepts was observed, with no significant gender differences. Most trainees (68–91%) supported GPPs, such as equal opportunities and gender-collaborative environments, though (27–33%) struggled with mainstreaming gender into content or preventing inequalities. Observations showed effective gender-neutral practices but a focus on binary gender categories. The pedagogical actor highlighted practical adaptations despite low formal knowledge, with cultural resistance and resource limitations as barriers.

Discussion: The findings reveal a disconnect between awareness and practice, challenging the notion that knowledge drives GPP adoption. Cultural norms hinder awareness, yet practical efforts persist. Enhanced, culturally sensitive training and resources are needed to strengthen GPP integration, informing policies for equitable education in Morocco.

Introduction

Many recent studies agree that school, far from being a neutral space, is a place of socialization where differentiated social relations are constructed and reproduced, particularly in terms of gender. Several studies have highlighted the implicit reproduction of gendered stereotypes by teachers. For example, Limboro (2018) showed that in informal schools in Nairobi and Kilifi (Kenya), teachers interact more with boys, marginalizing girls and limiting their educational opportunities. Similarly, Pascoe and Herrera (2018) argued that school rituals reinforce heteronormativity and consolidate gender hierarchies within everyday interactions. In the same vein (Da Silva, 2013), drawing on a study conducted in educational institutions in Novo Hamburgo (Brazil), demonstrated that sex education practices often convey heteronormative conceptions, reducing the recognition of diverse sexual and gendered identities.

Some studies have underlined that the lack of teacher training, combined with institutional resistance, is a major brake on the transformation of educational practices. Xavier et al. (2020) explained that the fear of gender-related accusations and ignorance of related concepts hinder the implementation of equitable and inclusive educational programs. Indeed, some studies have proposed alternative approaches to integrating inclusive education based on equality and recognition of diversity. Brazão and Dias (2020) called for the deconstruction of binary genders and the promotion of identity autonomy. Monteiro and Ribeiro (2019), meanwhile, Rios and Vieira (2020) argued for the integration of discussions on gender and sexuality into school curricula, with a view to creating inclusive educational environments. However, these findings need to be qualified. Pedagogical practice does not necessarily stem from a fully developed awareness of gender issues. We might ask whether awareness is always a prerequisite for change: might not practice itself precede and ultimately encourage an evolution in representations?

Local pedagogical experiences show that innovative practices can help deconstruct gender norms, even in the absence of an explicit theoretical framework. de Oliveira (2016), for example, describes situations in which girls play soccer and boys tell stories, thus overturning traditional gender roles. These concrete practices help establish a school culture based on tolerance, diversity, and equality.

From this perspective, pedagogy can also be expected as a strategy to reduce the gender gap in society. Thus, social justice pedagogies have been promoted, which seek to challenge and address various forms of inequality, including gender disparities, in educational contexts (Gerdin et al., 2021). This has contributed to the emergence of initiatives for justice in education, such as feminist education, the use of technology to achieve equity and equality in education, and values-based education (Lai, 2021; Kreitz-Sandberg, 2016; Alasmari, 2020). In addition, the concept of Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) has been developed and, among other practices, highlighted as useful for closing achievement gaps and reducing existing inequalities in education (Griner and Stewart, 2012). Furthermore, Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a key element in achieving social justice in education; it is a concept that enables a critical examination of social issues related to inequalities and helps to challenge stereotypes that perpetuate inequalities (Campbell, 2013).

Furthermore, values-based educational interventions can effectively reduce the gender gap in academic achievement in science (Miyake et al., 2010). Following these pedagogical practices, other concepts have been developed, including many historically marginalized social groups, such as the concept of queer pedagogy, which has emerged as a framework for recognizing and integrating sexual and gender diversity in educational practices (Ulla, 2023; Ouabou and Idrissi, 2024).

Consequently, our use of the concept of Gender Pedagogical Practices (GPPs) describes a multidimensional approach that includes gender equality education, culturally sensitive teaching, social justice education, values-based educational interventions, and teaching focused on empowering less privileged social groups. This concept also includes the implementation of a set of education or teaching strategies that aim to create inclusive learning environments that advocate for equality, diversity and equity in education (Gerdin et al., 2021).

Gender pedagogical practices (GPPs) in Moroccan society and education

Although some Arab countries have undergone progressive reforms to enhance the status of women, gender equality remains limited in most of these countries, especially in terms of economic empowerment and political participation. In the Gulf countries, despite the expansion of women’s education and participation in the labor market, gaps remain in terms of legal rights and political and economic representation, according to World Bank indicators (World Bank, 2021). In North Africa, Tunisia’s experience stands out for its progress in equality-related legislation, such as the passage of the law against gender-based violence in 2017 and political discussions on inheritance equality, while Algeria recorded a high female representation in parliament in 2012, at 31.6 percent, without a structural shift in economic leadership positions (CAWTAR, 2019). As for Morocco, the 2018 World Economic Forum report ranked it 137th out of 149 countries in the Gender Gap Index, lagging behind its neighbors in the Greater Maghreb (World Economic Forum, 2018, p. 11). It should be noted that Morocco has made significant improvements in the field of education, reducing the gender gap by more than 2% in just 1 year, making it one of eight countries that have made clear progress in this area (World Economic Forum, 2018, p. 9).

Gender inequality in Morocco is a complex issue that is influenced by various factors such as culture, religion, and politics. The sociology of gender provides a framework for understanding the social construction of gender roles and how they intersect with other social structures. Religion, as a significant aspect of culture, plays a crucial role in shaping attitudes toward gender roles and expectations (Saltzman Chafetz, 1999). In Morocco, where Islam is the predominant religion, interpretations of religious teachings can affect gender equality (Mernissi, 1987, p. 36). Therefore, understanding the interplay between religion and gender is essential in addressing gender inequality in Morocco. Moreover, politics also plays a significant role in perpetuating or challenging gender inequality. Thus, political systems and processes, in particular the importance of political structures in shaping social policies affecting gender equality, should also be highlighted (Leicht and Jenkins, 2010). In Morocco, political decisions and policies can reinforce traditional gender norms (Mernissi, 1997, p. 206). The intersection of culture, religion, and politics in Morocco creates a complex landscape for addressing gender inequality. It is important to consider the cultural and religious context of Morocco when advocating for gender equality to ensure that interventions are culturally sensitive and effective.

The influence of this cultural context is evident even in legislation and Morocco’s ratification of international agreements, for example, unilateral statement on articles 2, 9(2), 15(4), 16, and 29 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) after ratification in 1993 (Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme-Maroc, 2013; Letter to the King of Morocco on His Commitment to Withdraw Reservations to CEDAW|Human Rights Watch, n.d.). These unilateral statements deal with legal and constitutional equality between men and women, equality within the family, the right of women to pass on their nationality to their foreign-born spouses and children, and women’s right to freedom of movement (Gerntholtz et al., 2011). All these reservations were withdrawn in 2011, and after that has adopted measures to mainstream gender equity. These were complemented by the 2011 Constitution (Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme-Maroc, 2013).

Thanks to its successful policies and programs, Morocco has achieved relative equality in access to education (Ouabou et al., 2023). Where net attendance rates in primary school were above 90 percent. In addition, there was a significant increase in Morocco’s enrolment rates for girls by 28 percentage points during the 1999–2013 period, the gains were directly attributable to long-term emphasis on school construction in rural areas and gender equity reforms (Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental (CESE) - Maroc, 2014, p. 48). Despite these successful policies, the enrolment was lower for females, in rural areas, and among the poorest people, which indicates a shortcoming in the programs targeting vulnerable populations. Enrolment rates showed gaps and biases between sexes, rural and urban, and the poorest and richest populations, compared with most Arab countries (Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 2019, p. 82).

This gap is not only evident in access to primary education but also in access to secondary education and vocational integration. Where the gross enrolment ratio in lower secondary education is still below 80 percent for girls (Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 2019, p. 88) In the Arab States, including Morocco, early marriage, poverty, and conflict often are barriers to the progress of young girls in education (Bergenfeld et al., 2020). The stigma associated with vocational learning also has a major role in discouraging young adults from pursuing vocational qualifications. Globally, the female share of secondary vocational education stands at 43 percent; 7 percentage points away from gender equality. In the Arab States, the share of females is only 38 percent; whereas in Morocco, this percentage does not exceed 34 percent (Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 2019, p. 94).

Through current educational policies, Morocco has taken multiple initiatives to activate the gender approach in the educational field under national public policy commitments in this regard. These initiatives are based on the recommendations of the Strategic Vision for Educational Reform 2015–2030, which emphasized the spread of the values of justice, fairness, and equal opportunities as basic levers for the advancement of gender rights and equality. These initiatives are also based on Framework Law 51.17, which defines the basic principles on which the system of education, training, and scientific research is based, and the basic objectives of state policy in this field, which were also adopted in the directions of the development model 2021–2035. On this basis, public policy programs in the educational field were keen to adopt an integrated approach that seeks to promote fairness and equality in order to achieve conditions of equal opportunities between the sexes while rejecting all forms of discrimination and manifestations of violence based on gender.

In recent years, GPPs has been a subject of interest in Moroccan schools. The Global Education Monitoring Report (2022) noted that teaching and learning practices in Morocco, including gender segregation, may affect GPPs (UNESCO, 2022). The literature suggests that gender pedagogical practices in Moroccan schools are influenced by several factors, including textbook content, teaching methods and societal norms. The presence of gender bias in Moroccan textbooks has been explored, with questions raised about whether these materials are used to promote discriminatory discourses or as a means of pedagogical innovation (Mechouat, 2017b).

Ziv (2006) shows that religious teaching in Moroccan schools addresses sensitive issues such as menstruation, but that these teachings are often contradicted by dominant cultural perceptions, reinforcing the stigmatization of girls (Belhachmi, 1987), for her part, denounces the formal and informal mechanisms through which schools reproduce gender inequalities, limiting girls’ access to educational success and participation in development.

Several studies have proposed adopting critical pedagogy in Moroccan educational settings to challenge existing gender norms and power dynamics. By explaining these educational practices, the studies highlight critical pedagogy as a catalyst for achieving social justice in Moroccan schools, emphasizing the importance of pedagogical techniques that support equitable learning and question cultural norms (Bendraou and Sakale, 2024; Mechouat, 2017b).

More importantly, there is a need for all teacher training centers to prepare the new generation of teachers to use sexist texts constructively. Civic education is a fundamental subject in primary education that can enhance teacher trainees’ and students’ awareness of GPPs (Mechouat, 2017a).

To ensure a rewarding implementation of the civics program and efficient reinforcement of engagement and gender- sensitive values, teacher educators, teacher trainees and all teacher practitioners should be familiar with the available resources and content relevant to civic-oriented education (Mechouat, 2017a). Indeed, without educating the student community—the most vital component of society—on these principles and practices, the process will remain slow, vulnerable, and unsustainable (Mechouat, 2017a). Furthermore, Espinoza examined the role of gender in classroom interactions and the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and pedagogical practices, finding evidence that gender stereotypes influence teaching practices (Espinoza and Taut, 2016).

We conclude that GPPs encompasses various dimensions of the teaching-learning process, whether it is related to practice and relationships within the classroom, the tools and resources used, or approved assessments and lesson planning. Practice can also be influenced by teachers’ stereotypes. As a result, the development of pedagogical practice is linked to the need to review the different elements of the teaching-learning process, and it is also assumed to build awareness among teachers based on gender-inclusive civic education programs.

But to what extent do educational practices perpetuate gender inequalities? Are teachers aware of gender issues? Is there a relationship between awareness and practice? Couldn’t practice be different from awareness? These questions, which we will address in this research through a multidimensional approach, propose a quantitative analysis of trainee teachers’ attitudes and analyze patterns of their practice, then provide a qualitative explanation of the relationship between consciousness and teaching practice.

Significance of study

In the context of the above data, we conclude that there is a gap between the level of ambitious efforts made in general policies and the statistics issued by international institutions, which show the persistence of gender inequality in education. Indeed, the Moroccan legislature has enacted a set of general laws to promote gender equality in education. However, official and unofficial statistics continue to reveal gaps in access to education, career, and professional integration (Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc, 2020).

The aims of this study are framed in the context of the gap between directives, policies, programs, and outcomes. To mention the reality of this problem, we will examine actual and real practice and perhaps, we will discover in it what makes this gap continue and what hinders major projects in achieving gender equality. Are GPPs in Moroccan schools? How then do practitioners and pedagogical actors understand the implications of the gender approach in schools?

GPPs can address gender inequality, enhance educational practices, inform policy and curriculum development, empower educators, and encourage research and dialog. By focusing on gender pedagogy within the Moroccan context, the study contributes to understanding our country’s education system to create a more inclusive, equitable and empowering education system.

This study aims to address the following problematic issues: to what extent are GPPs effectively integrated into Moroccan schools, and how do these practices contribute to the challenge of gender disparities and gender stereotypes in education?

To address this problem, we will study teachers’ awareness, practices, and attitudes (Generally speaking, awareness relates to knowledge and cognition, attitudes relate to motivation, and practices relate to ways of engaging or behavior; National Academies of Sciences, 2016, p. 48) based on the following research questions:

1. What is the level of knowledge of Moroccan teachers regarding key concepts related to gender approach in education?

2. To what extent do Moroccan teachers integrate gender-responsive pedagogical practices (GPPs) into their practices?

3. What are the attitudes of Moroccan teachers towards gender equality and the diversity of gender identities?

Based on the three research questions identified in this study, we propose the following hypotheses:

• Hypothesis 1 (related to the first question): Moroccan teachers have limited knowledge of the concepts and principles associated with the gender approach in the educational field.

• Hypothesis 2 (related to the second question): A significant number of Moroccan teachers incorporate gender-responsive pedagogical practices into their professional performance, even with limited theoretical awareness of gender concepts.

• Hypothesis 3 (related to third question): The majority of Moroccan teachers adopt positive attitudes in support of gender equality in educational practice, with varying degrees of acceptance of diverse gender identities.

Goals and purpose

The objectives and purpose include a multidimensional approach to different issues that concern the integration of the gender perspective into educational practices. This research will be central to teachers’ perceptions of how gender can be seamlessly integrated into their teaching methodology. It also sets out to understand teachers’ perceptions of the development of the Gender Parity Plan-GPPs.

More specifically, this research focused on the contextualization of GPPs implementation in Moroccan schools by first identifying the various barriers to proper GPPs practice adoption while developing strategies for effective implementation at schools.

The analysis also explores the complicated interplay among values, religion, and culture in terms of their influence on GPPs integration. In this case, it attempts to shed light on the higher social influences that shape educational practices by investigating the factors that influence teachers’ GPPs approaches.

The study also states that further development and strengthening of GPPs requires an examination of how. This study contributes by offering key insights to enhance gender equality in educational settings by highlighting innovative strategies that provide an effective way forward in advancing GPP practices.

Method

Participants, setting, and procedures

The study targeted teachers and teacher trainees undergoing training at the Teacher Training Center in Tata (central-eastern Morocco) between 2023 and 2024, who were expected to be appointed to various cities in the Souss-Massa region.

This mixed-methods study employed questionnaires, observations and interviews to collect data on awareness, practices and attitudes regarding the adoption of a gender approach in Moroccan schools.

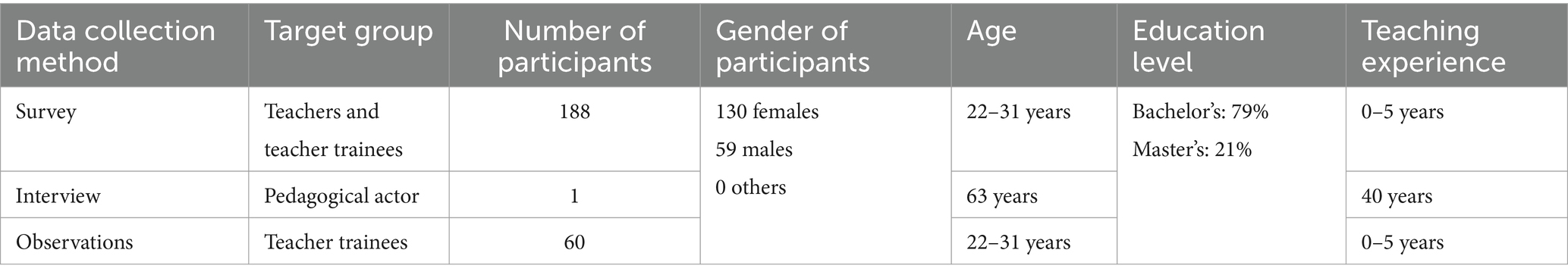

The study sample consisted of 189 participants: (See Table 1).

• 188 participants (130 women and 58 men, aged 22 to 31) who completed the questionnaire. 79% held a bachelor’s degree, and 21% held a master’s degree. All participants (188) had 0–5 years of teaching or training experience.

• 60 trainees were selected for classroom observations.

• A pedagogical actor was interviewed to gain insights into gender-responsive pedagogy (GPP) implementation in Moroccan classrooms. Aged 63 years, with 40 years of combined teaching and administrative experience.

This sample represents 2.68% of the national cohort of 7,000 trainee primary education teachers and 57.66% of the regional cohort.

The survey covered three main topics:

• Gender knowledge and awareness.

• Implementing gender-responsive pedagogy.

• Developing gender-related attitudes.

Interviews with pedagogical actors

To gain deeper insights into the practical implementation of GPP, we interviewed a pedagogical actor responsible for training teacher trainees.

• A 63-year-old male was employed at CRMEF-SM/Tata.

• He had 40 years of combined teaching and administrative pedagogical experience, including 16 years as a primary school teacher and service in the RTT (Responsible for Teacher Trainees) from 2001 to 2024.

The primary objective of this interview was to understand the experiences of an educational actor in managing teacher trainees rather than generalizing findings to all training centers. His role involved:

• Managing and coordinating training programs for teacher trainees.

• Supervising and guiding trainees in their professional development.

• Evaluation of performance and providing recommendations for improvement.

Classroom observations

Observations were conducted with 60 teacher trainees from the sample to assess the integration of gender-responsive principles in classroom practices and their impact on student learning and engagement.

• Teachers’ practices were observed in real classroom settings to determine how well they applied gender-based educational strategies.

• Each teacher was asked to prepare and implement a gender-mainstreaming assessment that promoted equality and diversity while ensuring objective evaluation criteria free from gender biases or stereotypes.

Observations were conducted with 60 teacher trainees, representing approximately 32% of the primary sample. This selection aimed to ensure accurate and focused monitoring of gender-responsive practices in real classroom settings. The choice of this limited sample size was driven by the need to:

• Achieving accuracy in tracking pedagogical achievement and analyzing classroom interactions;

• Managing the observation process within the available time and logistical possibilities;

• Ensuring a more reliable link between quantitative and qualitative data; and Ensuring a more reliable link between quantitative and qualitative data.

To systematically analyze the observation data, we used a set of indicators to assess the alignment of teachers’ classroom practices with gender mainstreaming principles:

• Equal opportunities for all students.

• Avoidance of gender stereotypes in teaching and assessment.

• Inclusion of diverse needs, such as accommodations for students with special needs.

• Reflection on gender diversity in teaching materials and assessment tools.

• Use of gender-neutral language and various assessment formats to challenge traditional gender roles.

The classroom observations focused on the assessment of primary school students’ geography, history, and citizenship education. These assessments were designed by 12 groups of five trainees each to evaluate how effectively teacher trainees applied gender-sensitive principles in evaluation and assessment activities.

Table 1 presents the distribution of study participants according to professional category and data collection method.

Measures

This study is based on a mixed method with various methodological dimensions in terms of the quantitative and qualitative data collected. In terms of the analysis in which we tried to achieve integration between quantitative and qualitative data since the data we collected through the survey was not sufficient to explain and understand the trends of awareness, practices, and attitudes, it was necessary to return to actual practice by adopting both the interview and observation techniques.

Regarding quantitative analysis, we mainly focused on statistical descriptive analysis to measure the accumulation of answers, which enabled us to measure and classify the trends of answers to the survey questions that were prepared according to the Teacher Efficiency in Gender Equality Practice (TEGEP) scale (Miralles-Cardona et al., 2021). In the qualitative analysis, we focused on presenting the data that directly answers the results of the quantitative analysis and explains the trends we reached in this analysis.

Design and data analysis plan

Research design

Methodological approach

Our study adopts a mixed methodological approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methods for an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon studied. This approach allows us to collect both numerical data (via Google Forms) and textual data (via practical workshops and one interview) to triangulate our results and obtain a more complete view of the topic.

Data collection tools

The questionnaire was used to collect quantitative data on awareness, implementation, and attitudes. The questionnaire was distributed through Google Forms. We focused mainly on analyzing the results to interpret and understand attitudes. The interview also deepened our understanding of the relationship between awareness, attitudes, and practices. To observe practices, 60 trainees were assigned to prepare targeted assessments for primary school students. Through this assignment, which required them to design assessment materials to evaluate students’ achievements in history, geography, and citizenship education. The trainees were tasked with developing diverse evaluation situations in the classroom, including question formulation, visual and textual support and assessment criteria.

Data analysis plan

The data analysis combines quantitative and qualitative approaches to address research questions (RQ1–3) regarding teacher trainees’ awareness, practices, and attitudes toward gender-responsive pedagogical practices (GPP).

Quantitative analysis

We collected quantitative data through Google Forms and exported it into a spreadsheet (Excel) for further analysis. Quantitative data are analyzed using SPSS v.26, employing descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, standard deviations) to evaluate responses to the TEGEP questionnaire and Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to compare response distributions (categorized as Low: 1–2, Medium: 3–4, High: 5–6) by gender (male vs. female) for each survey question, addressing RQ1–3. Cramer’s V was calculated to assess effect sizes. For questions with low expected counts (< 5), categories were collapsed to ensure test validity. Qualitative data are processed through inductive thematic analysis, conducted manually, coding interviews and observations to identify themes such as cultural resistance or practical adaptations, validated by inter-rater reliability. Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative findings explains discrepancies, such as low awareness despite effective GPP implementation, providing robust and contextual conclusions.

Qualitative analysis

Following the full transcription of interview recordings and a description of the products produced by trainee teachers, a thematic classification was performed to analyze the outlined core concepts and emerging categories from the textual data to identify how gender-sensitive approaches were integrated, such as accommodations for students with special needs, the use of legal frameworks to discuss equality and the incorporation of problem-solving tasks that challenge traditional gender roles.

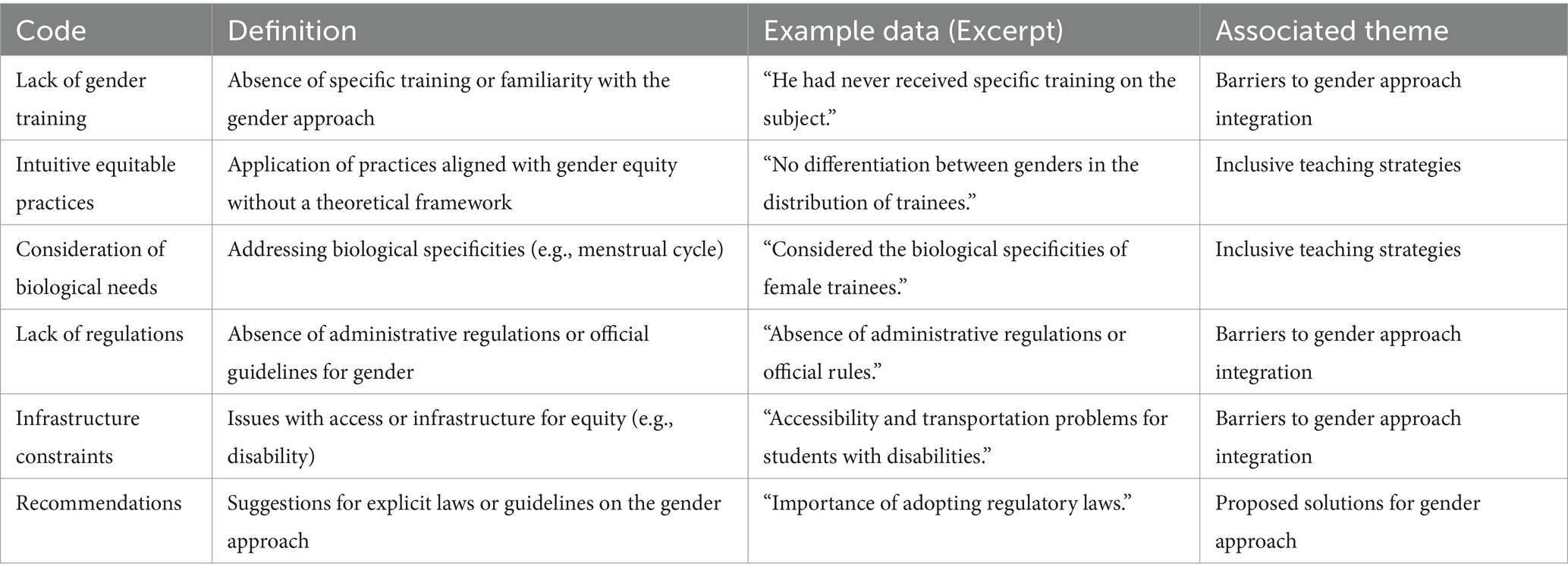

To analyze the content of the pedagogical actor’s interview responses, a systematic coding process was employed, following the thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Transcripts were reviewed line by line to identify meaning units relevant to GPP implementation in Moroccan classrooms. An inductive coding strategy was used, allowing codes such as “cultural resistance,” “practical adaptations,” and “resource constraints” to emerge from the data. Each code was clearly defined and systematically applied using a coding framework (see Table 2). To ensure reliability, 20% of the transcripts were double-coded by two researchers, achieving an inter-rater agreement of 85%. Codes were then grouped into broader themes, such as “barriers to GPP integration” and “inclusive teaching strategies,” validated through iterative data review and team discussions to ensure a robust and coherent analysis.

Table 2. Coding framework for the analysis of the educational actor’s responses on the implementation of the gender approach.

Data integration

The findings from the quantitative and qualitative analyses were integrated to provide an overall interpretation of the data. The results are illustrated using tables, figures, and concrete examples to make them easier to understand.

Results

In order to address the three research questions, the data collected through our research methods (the survey, the interview, and the case study) included three dimensions related to the gender approach in education: “gender knowledge and awareness,” “implementation of gender-responsive education,” and “development of attitudes toward gender.” We statistically analyzed these data according to these three dimensions.

Gender knowledge and awareness

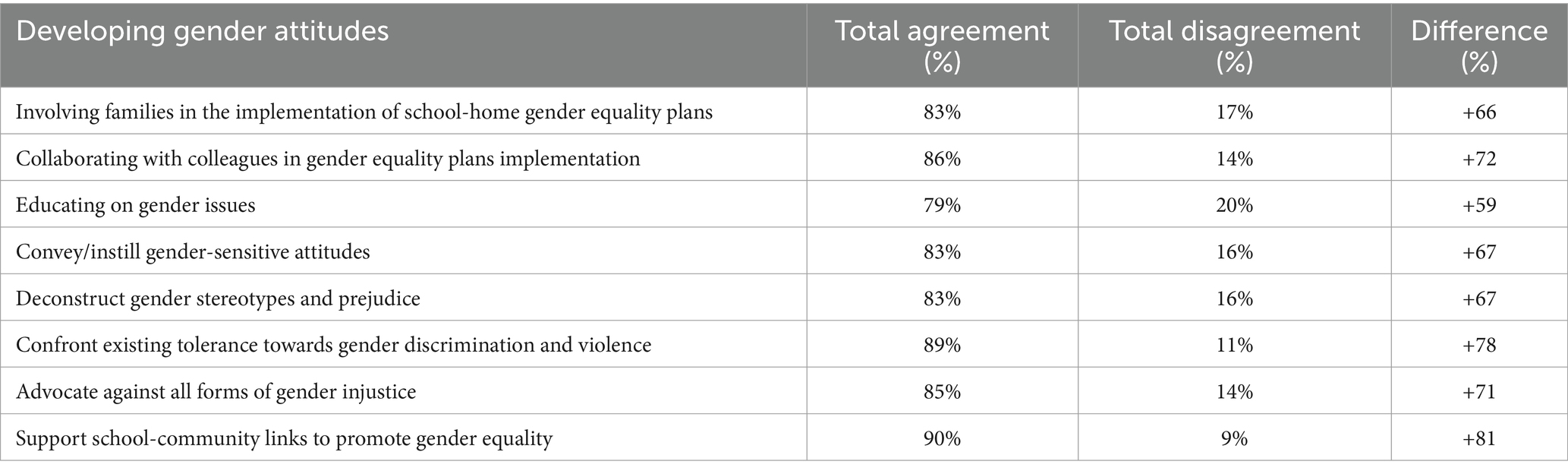

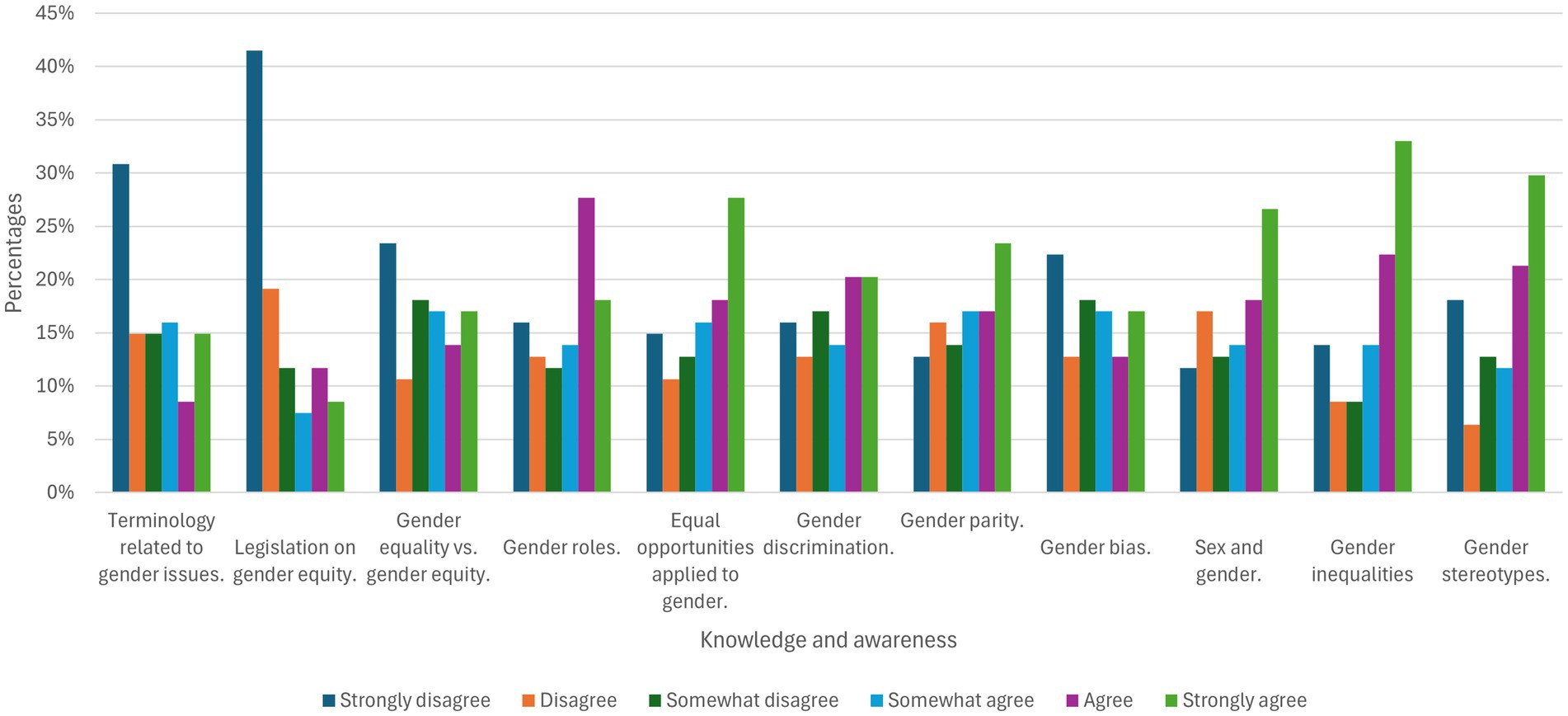

At the level of the participants’ awareness of knowledge and concepts related to gender, three trends appeared related to the classification of awareness, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3. Comparison of the percentages of agreement and disagreement regarding awareness of gender concepts and issues.

Figure 1. Comparing the answers related to the participants’ level of awareness of gender concepts and issues.

The first trend: includes gender concepts that most participants were able to identify and be aware of. The average percentage of those who recognized and were able to comprehend these concepts reached 61.66%, and the positive answers ranged from 57 to 69% (see Figure 1).

The participants in this study answered the question regarding their gender by choosing among the three options provided: “male,” “female,” and “other.” However, the responses were exclusively focused on the two traditional categories, namely “male” and “female.” None of the participants selected the “other” option, which potentially reflects an absence of identification outside these two binary categories within the studied group. See Table 1.

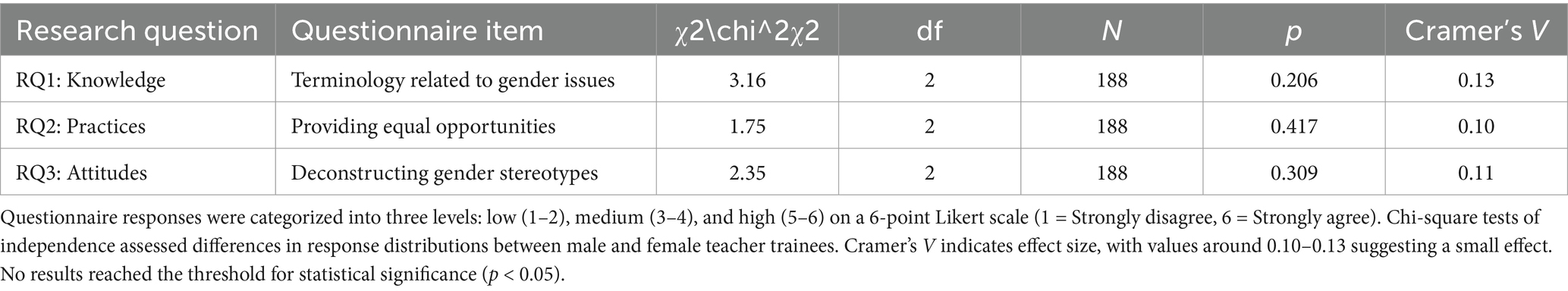

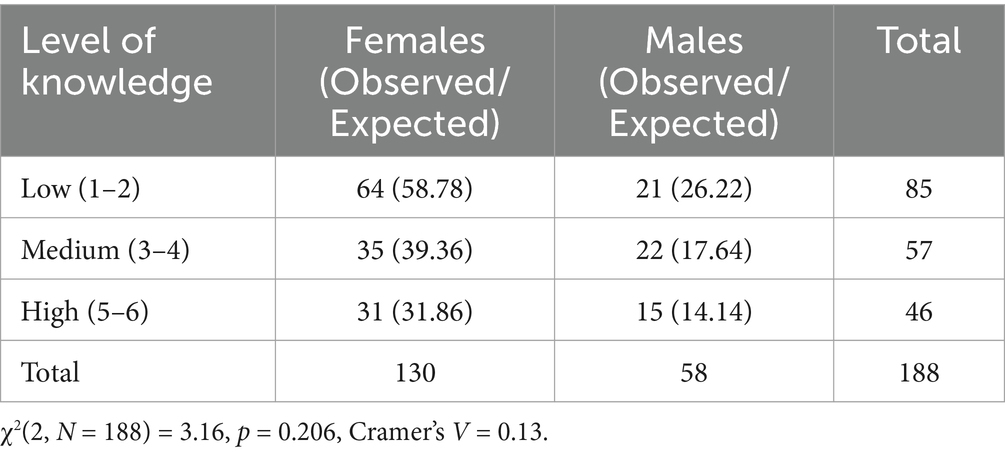

To address Research Question RQ1 regarding knowledge of gender-related terminology, a Chi-square test was conducted to examine the association between gender and the level of knowledge of gender-related terms (low, medium, high). The 188 responses (130 females, 58 males) revealed no significant difference between genders, χ2(2, N = 188) = 3.16, p = 0.206. The effect size, measured by Cramer’s V, was small (V = 0.13). Observed and expected frequencies are presented in Tables 4, 5.

The observations conducted during the case study revealed a restrictive interpretation of the gender approach among some participants. These participants limited the application of gender equity principles to the binary categories of males and females. This narrow conception was concretely manifested in the design of the questions and formulation of the evaluation situations. For example, the proposed situations do not consider gender identity diversity beyond traditional binary thinking. This limitation indicates a lack of a comprehensive understanding of gender approaches that foster inclusion and equality for all, regardless of gender identity.

The educational actor who participated in the interview clearly expressed his lack of familiarity with the gender approach, emphasizing that he had never received specific training on the subject. However, in the absence of administrative regulations or official rules, the head of the training center relies on various methods that mainly depend on administrative leniency and tolerance in difficult cases.

The following gender concepts and issues were identified:

• Gender stereotypes

• Gender inequalities

• Equal opportunities for gender

• Gender Roles

• Sex and Gender

• Gender Parity

The second trend: includes the answers in which the participants expressed their ignorance of gender issues and concepts at a rate of up to 66.5% (see Figure 1), and these answers relate to the following concepts and issues:

• Terminology related to gender issues.

• Legislation on gender equity

The third trend: There was a balance between participants who had awareness and knowledge of gender concepts and those who did not, as the percentages approached half in both categories in the following fields, issues, and concepts:

• Gender discrimination.

• Gender parity.

• Gender bias.

Implementing gender pedagogy practices (GPPs)

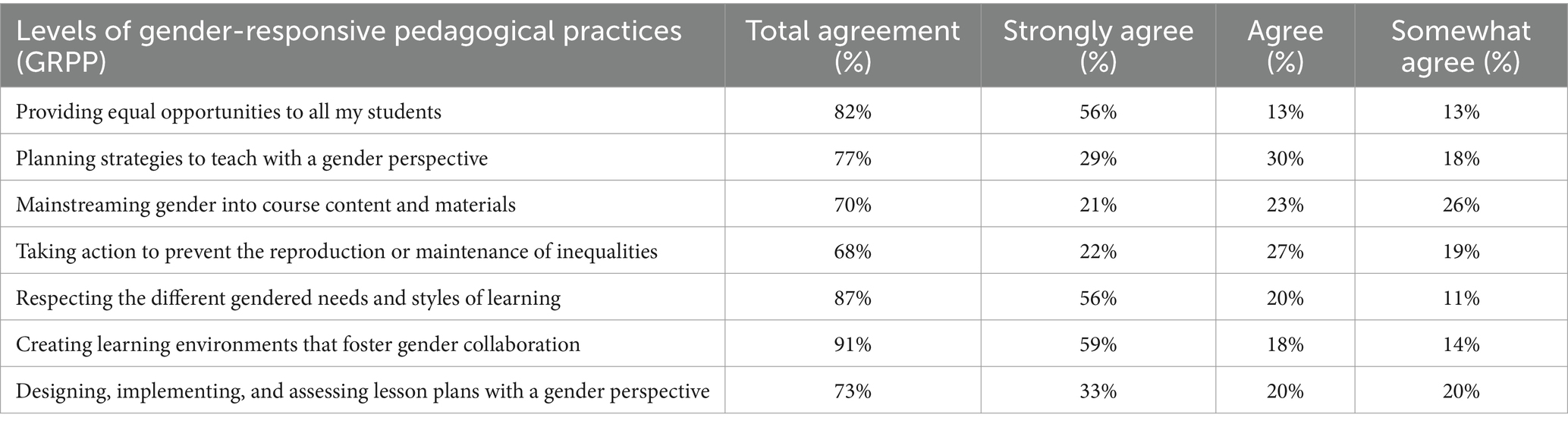

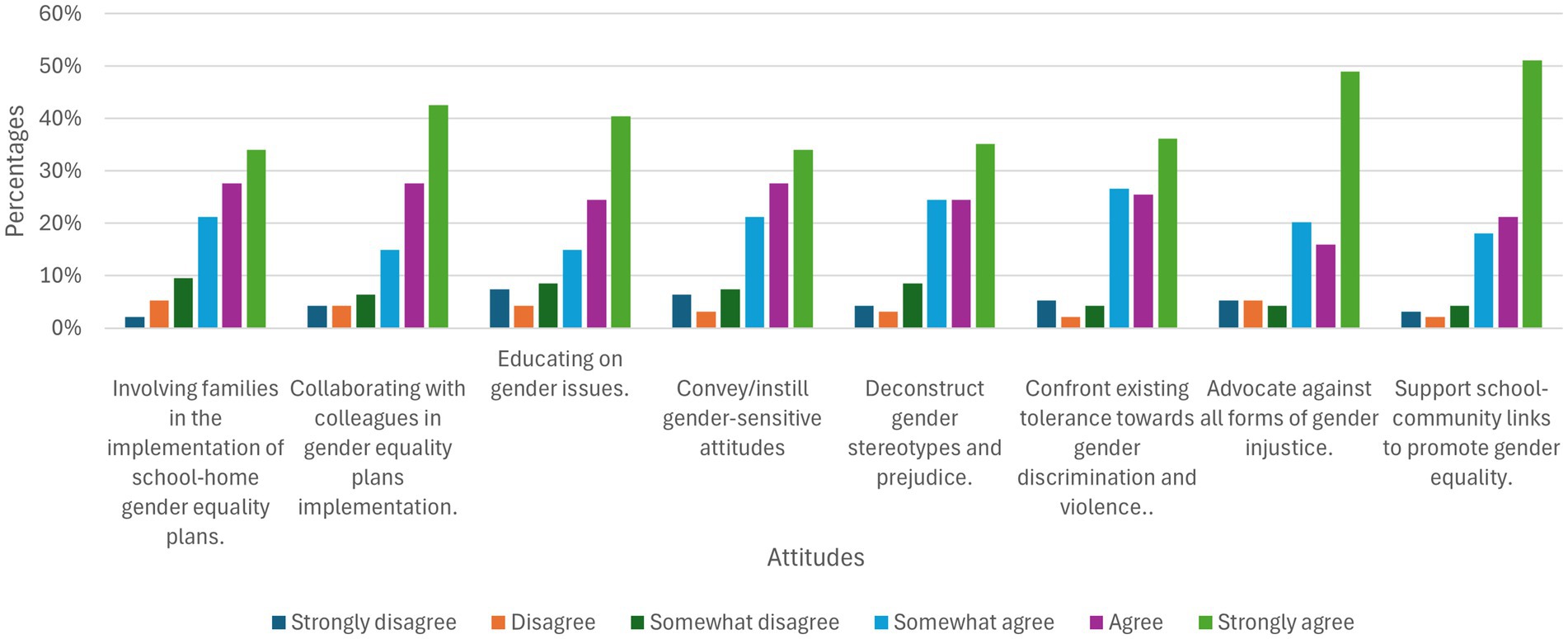

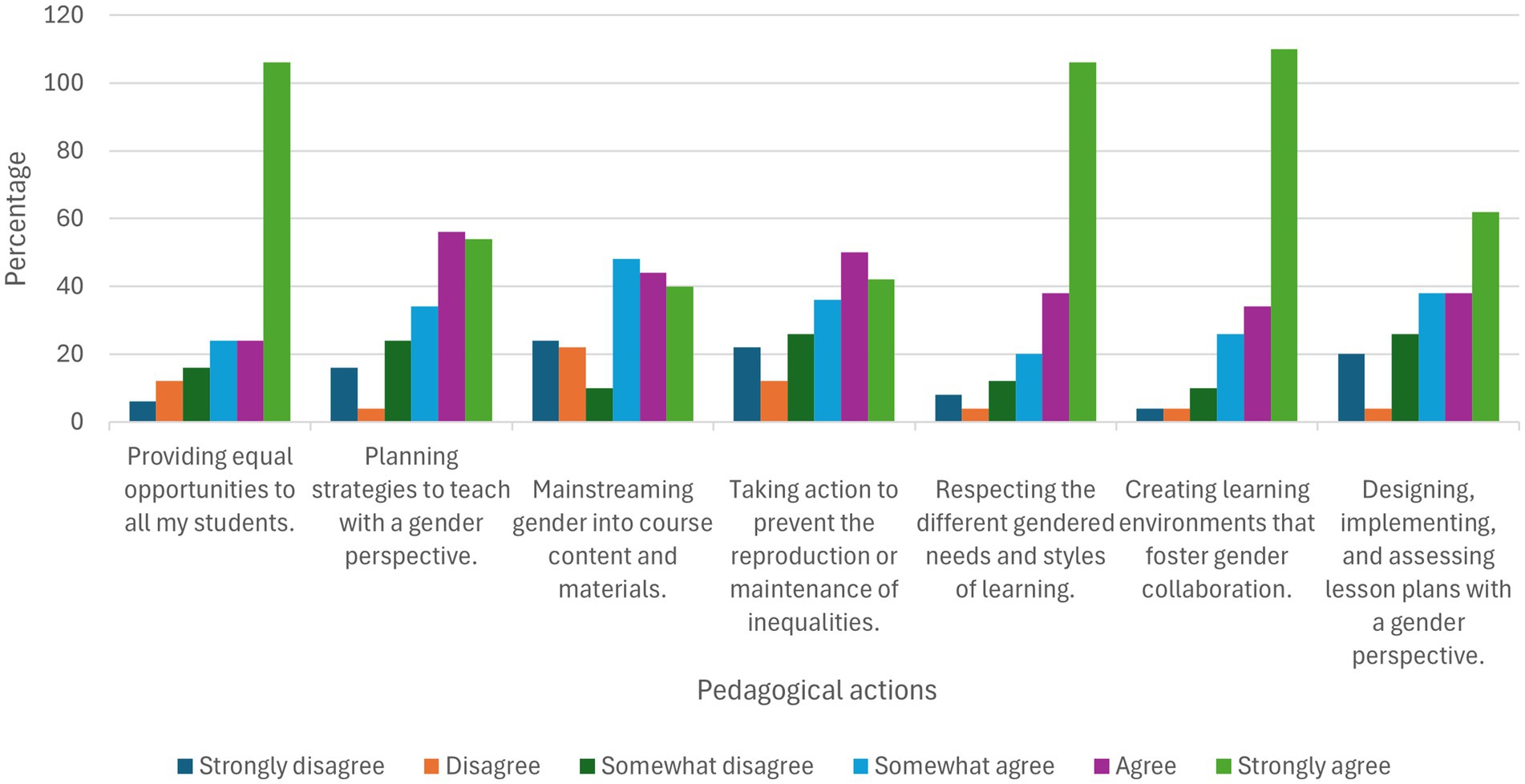

Table 6 and Figure 2 show that the general trend of the data confirms the tendency of all participants to express their agreement with most GPPs, which indicates that the majority agree with adopting these pedagogical practices or those they have previously adopted or are capable of doing so. However, there is a difference in the levels of agreement in some of these pedagogical practices. In addition, there are levels at which disagreement or negative answers appear, which may indicate either refusal or inability to adopt these pedagogies. The trends of the answers can be divided into two types:

The first trend: is answers that show an increase in expressing inability or refusal to adopt certain pedagogical practices, and it is related to these levels of GPPs: at the first level, “taking action to prevent the reproduction or maintenance of inequality,” 32% of participants disagreed. The second level is related to “Mainstreaming gender into course content and materials,” and the number of those who expressed their disagreement or inability reached one-third of the participants. Regarding the third level of GPPs, it is manifested in “Designing, implementing, and assessing lesson plans with a gender perspective,” where the percentage of those who did not agree with the question was 27% of the participants. (The results are presented in Table 6).

The second trend: represents the answers in which there is a strong consensus, which is manifested in: agreement to adopt GPPs or participants expressing their ability to do so, and among the most important of these levels pedagogical practices we mention:

• Creating learning environments that foster gender collaboration.

• Respecting gender needs and learning styles.

• Providing equal opportunities to all my students

Table 6. Comparing the degrees of agreement and disagreement about levels of gender-responsive educational practices.

Figure 2. Comparing the degrees of agreement and disagreement on the levels of gender-responsive educational practices.

To further describe these data, we show the degrees of agreement on the GPP levels related to the second trend in which participants state their agreement. Table 7 shows differences in degrees of agreement.

Most GPP levels have a high percentage of total agreement, ranging from 68 to 91%. See Table 7. However, the degrees of agreement can be divided into three degrees as follows:

The percentage of participants who strongly agreed with the three levels of the GPP ranged from 56 to 59%. See Table 7. These levels are as follows: Providing equal opportunities to all my students, Respecting the different gendered needs and styles of learning, and creating learning environments that foster gender collaboration.

In the second degree, in which the “agree” answer dominated, the percentage of these answers ranged from 27 to 30%, including the following levels: Planning strategies to teach with a gender perspective, taking action to prevent the reproduction or maintenance of inequalities. See Table 7.

In the third degree, participants answered “Somewhat Agree,” with the percentage ranging from 20 to 30%. These answers included the following levels: Mainstreaming gender into course content and materials, Designing, implementing, and assessing lesson plans with a gender perspective.

To address Research Question RQ2 regarding the practice of providing equal opportunities to all participants, a Chi-square test was conducted to examine the association between gender and the level of practice (low, medium, high). The 188 responses (130 females, 58 males) revealed no significant difference between genders, χ2(2, N = 188) = 1.75, p = 0.417. The effect size, measured by Cramer’s V, was small (V = 0.10). Observed and expected frequencies are presented in Tables 4, 8.

Table 8. Observed and expected frequencies for the practice of providing equal opportunities by gender.

However, the educational actor’s lack of formal knowledge did not prevent the application of certain practices that align with gender equity principles. Among the indicators revealing the correct, even partial, application of gender justice, it is noted that the educational actor did not differentiate between genders in the distribution of trainees in training classes, nor in the provision of facilities and specific measures for people with disabilities. He also considered the biological specificity of female trainees, such as issues related to the menstrual cycle and breastfeeding, although he was not familiar with the theoretical framework of the gender approach. This demonstrates that the causal relationship between knowledge of the theoretical framework of gender approach and actual practices aligned with its fundamental principles is not systematic.

Regarding the specific needs of female teachers, the interview reviews the most important cases in which women receive special privileges, which the law sometimes does not allow them to benefit from, the most important of which are cases related to absence or withdrawal from a training session for reasons related to the menstrual cycle or breastfeeding. The head of the training center confirmed that female teachers were often allowed to be absent in the event of physical and psychological disorders related to menstrual cycle. In the case of breastfeeding, timetables are arranged during morning and evening classes, giving women the right to break or reduce their working hours.

The majority of the research sample used evaluation situations that considered the gender aspects of the classroom (timeline, font size and style, writing colors, procedural actions, and clear instructions for different gender categories in the targeted classroom).

Most of the supports considered the general characteristics of the prevailing gender in the classroom (supports for students with special needs, supports that give students the right to choose based on their gender and place of residence).

It was observed that there was diversity in the evaluation situations that aligned with the gender characteristics of the students. Examples include problem-solving situations, objective questions, pictures, and diagrams illustrating areas of discrimination and equality in society based on gender and place of residence. It was also noted that some individuals in the research sample adopted text support accompanied by precise instructions for analysis and generating positions on the value of equality, whether based on gender, place of residence (urban/rural), or equality between regular students and students with special needs.

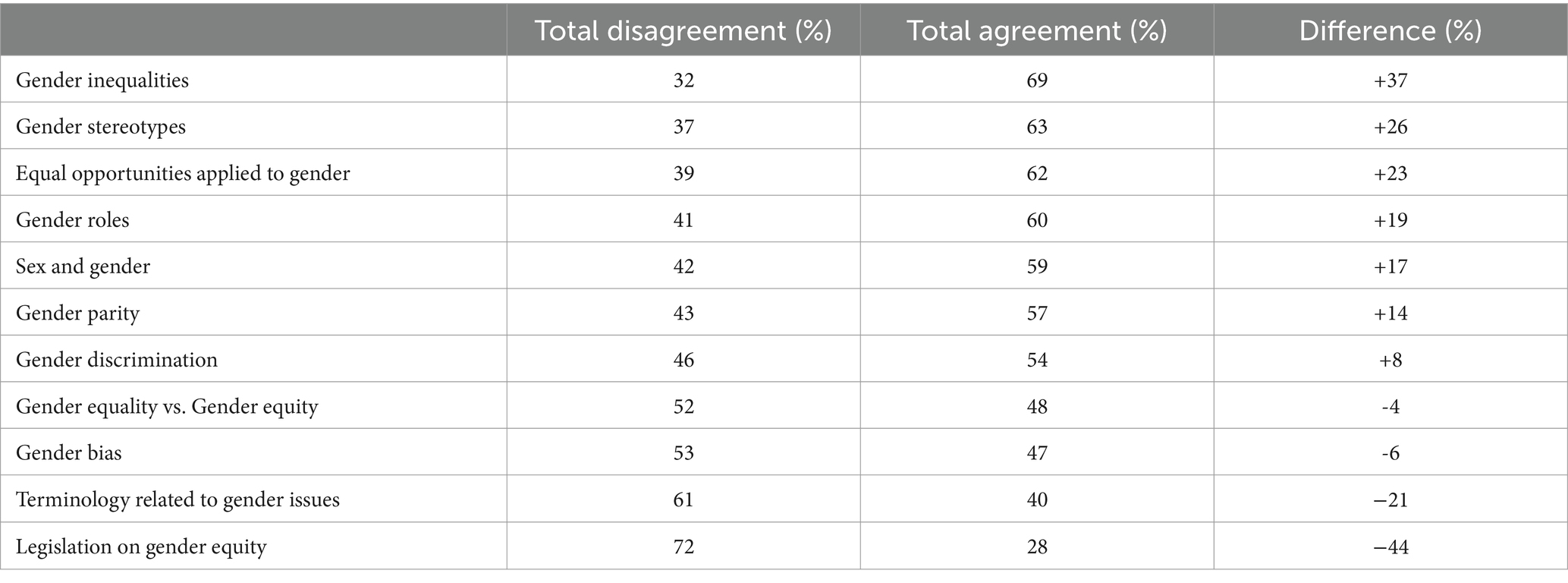

Developing gender attitudes

Table 9 shows that the degree of agreement is high, with percentages ranging from 79 to 90%. The highest total agreement was 90% and was associated with improving attitudes at the level of “Support school-community links to promote gender equality,” followed by the second level related to “Confront existing tolerance toward gender discrimination and violence” where the percentage reached 89%.

Despite this high level of agreement among most participants at the various levels of developing gender attitudes, there was a decline in some levels, where 17 and 20% of participants did not agree with them, which is related to the level of “Involving families in the implementation of school-home gender equality plans” and “Educating on gender issues.”

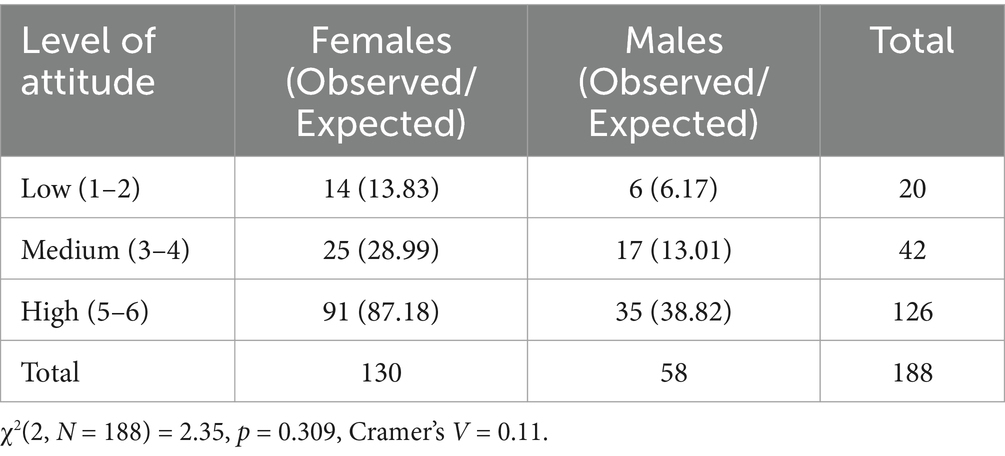

To address Research Question RQ3 regarding attitudes toward deconstructing gender stereotypes and prejudice, a Chi-square test was conducted to examine the association between gender and the level of attitudes (low, medium, high). The 188 responses (130 females, 58 males) revealed no significant difference between genders, χ2(2, N = 188) = 2.35, p = 0.309. The effect size, measured by Cramer’s V, was small (V = 0.11). Observed and expected frequencies are presented in Tables 4, 10.

Table 10. Observed and expected frequencies for attitudes toward deconstructing gender stereotypes by gender.

The educational actor’s recommendations highlight the importance of adopting regulatory laws and improving infrastructure to ensure justice in the gender approach, particularly because this enables both sexes to fully assume their roles and qualify for the acquisition of cognitive and professional skills. The actor also mentions cases of students with disabilities who encountered accessibility and transportation problems; the lack of specific procedures and measures for such cases was a challenge. Several recommendations were made for implementing a gender approach in teacher training centers, including the publication of explicit administrative regulations and formal guidelines that take into account the biological needs and social characteristics of teacher trainees, the development of educational infrastructure and facilities that consider the gender approach, and the involvement of experienced educational stakeholders in proposing policies and measures related to gender education.

In general, we note that there is a strong trend toward agreement on all levels of developing gender attitudes, as it is clear in Table 9 that there are large “positive differences” indicating widespread support for these attitudes (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our study explored the awareness, implementation, and attitudes of Moroccan teachers toward Gender Pedagogical Practices (GPPs). The findings are organized around three research questions: 1- participants’ knowledge of gender concepts, 2- their integration of GPPs in teaching practices, and 3- their attitudes toward promoting gender equality. Drawing on quantitative survey data, qualitative interview responses, and classroom observations, the discussion highlights the complex interplay of cultural, psychological, and practical factors shaping GPP adoption in Moroccan education, challenging theoretical assumptions about the relationship between knowledge, practice, and attitudes.

Knowledge of gender concepts

The first research question investigated participants’ awareness of gender-related concepts, including terminology, legislation, and stereotypes. Chi-square tests revealed limited gender differences in knowledge, except for awareness of gender stereotypes, where females showed significantly higher awareness [χ2(2) = 6.78, p = 0.034, Cramer’s V = 0.19]. However, survey data indicated moderate overall awareness (mean scores ~3–4), with no responses to the “other” gender option, suggesting that non-binary identities may not be recognized or expressed in Morocco’s cultural context. This aligns with Dialmy (2000); Saltzman Chafetz (1999), who notes that traditional gender norms in Moroccan society often restrict engagement with diverse gender concepts.

Qualitative findings from the pedagogical actor’s interview further illuminated this, identifying “cultural resistance” and “psychological rejection” as barriers to gender knowledge uptake, particularly when concepts are perceived to conflict with religious beliefs. The interviewee emphasized that societal norms prioritizing binary gender roles limit teachers’ willingness to embrace gender equity concepts, a phenomenon described as the “second stage of sexual transition” (Dialmy, 2000), where awareness lags practice. These findings contradict behavior modification theory (Ajzen, 1980; Fishbein et al., 2001), which posits that knowledge drives practice. Instead, the study suggests that cultural and religious taboos disrupt knowledge from action, necessitating culturally sensitive training to enhance gender awareness without triggering resistance.

Integration of gender pedagogical practices

The second research question examined how participants integrate GPPs into their teaching, such as ensuring equal opportunities and designing gender-responsive assessments. Chi-square tests showed no significant gender differences for most practices (p > 0.05), except for creating collaborative learning environments, where females reported stronger agreement [χ2(2) = 7.12, p = 0.028, Cramer’s V = 0.20]. Classroom observations confirmed that most trainees successfully designed assessments reflecting gender diversity and student needs, incorporating gender-neutral language and inclusive activities like mixed-gender group projects. This indicates a promising trend toward gender-responsive pedagogy, despite systemic challenges.

However, the pedagogical actor’s interview highlighted “resource constraints” and “inadequate infrastructure” as barriers to GPP integration, noting that practices often rely on teachers’ initiative rather than institutional support. Notably, the interviewee described implementing gender-responsive solutions, such as equal opportunity distribution, even when these violated official regulations perceived as unfair to females. This practical adaptability, despite low awareness, supports the study’s finding of a dissonance between knowledge and practice, challenging National Academies of Sciences et al. (2016), who argues for a strong empirical link between awareness and action. The observation data further revealed limitations, as some trainees focused narrowly on male–female equality, neglecting broader gender dynamics. These findings underscore the need for enhanced training and resources to support comprehensive GPP implementation in Moroccan schools.

Attitudes toward gender equality

The third research question explored participants’ attitudes toward promoting gender equality, including advocating against injustice and deconstructing stereotypes. Chi-square tests indicated no significant gender differences for most attitude items (p > 0.05), except for advocacy against gender injustice, where females showed stronger agreement [χ2(2) = 6.23, p = 0.044, Cramer’s V = 0.18]. This suggests that female trainees may be more motivated to challenge systemic inequities, possibly due to personal experiences or exposure to feminist principles.

The pedagogical actor’s interview provided context, revealing a tension between rejecting gender concepts deemed culturally or religiously incompatible and adopting gender-responsive practices. The interviewee advocated for practical solutions, such as addressing female students’ special needs, over changing deeply held beliefs, indicating that attitudes toward equality are shaped by pragmatic rather than ideological considerations. Observation data supported this, showing that trainees integrated gender equality principles in citizenship education but avoided controversial topics like gender-based violence due to cultural sensitivities. These findings align with UNESCO (2022), which emphasizes the role of teacher attitudes in advancing gender equity in conservative contexts. The lack of a strong correlation between attitudes and awareness further challenges behavior modification theory, suggesting that cultural and social factors mediate the relationship between beliefs and actions.

Implications and limitations

The study’s findings have significant implications for Moroccan teacher training and educational policy. The cultural and psychological resistance to gender knowledge highlights the need for culturally tailored professional development that frames gender equity within local values, reducing opposition rooted in religious or traditional beliefs. The promising GPP integration, despite low awareness, suggests that training should focus on practical strategies, such as designing inclusive assessments, to build on teachers’ existing efforts. The stronger advocacy among female trainees indicates their potential as leaders in gender-responsive education, warranting mentorship and support programs. Systemic barriers, including limited resources and regulatory constraints, must be addressed through curriculum reforms and increased funding for gender-sensitive materials.

Limitations include the small sample size (n = 188) and unequal gender distribution (130 females vs. 58 males), which may have limited statistical power. The absence of “other” gender responses may reflect survey design or cultural constraints, limiting insights into non-binary identities. The single pedagogical actor interview restricts generalizability, and the focus on SOUSS-MASSA may not capture urban or other regional dynamics. Self-reported survey data may be subject to social desirability bias. Future research should employ larger, more diverse samples, multiple interviewees, and longitudinal designs to track GPP adoption over time.

Conclusion

This research emphasizes that there is no strong correlation between awareness, practices, and attitudes regarding gender-sensitive education:

• Low gender knowledge does not necessarily mean GPP implementation.

• Awareness of and development of gender attitudes towards education are not significantly correlated.

These findings challenge the behavioral modification theory assumptions that assert knowledge determines its use in practice. This survey found that one can act on knowledge regardless of whether one personally believes in it or values it, thus refuting past studies and theories on it. Future research could focus on the development and evaluation of effective interventions to bridge this gap. This could include teacher training programs, awareness workshops, and organizational change strategies. It would also be useful to study the impact of these interventions on student outcomes and the school climate.

Cultural and psychological factors are among the reasons that this study showed resistance to understanding and accepting gender as a concept. Despite this resistance, kinder teachers can still engage in gender-responsive teaching, thus creating a disconnection in their hearts and minds between what they know but do not understand how to apply it. A society that refuses to be aware of something yet contradicts this decision through practice is depicted by the second phase of transition theory. In-depth qualitative research could explore these factors in detail, using interviews, focus groups, and case studies. It would also be interesting to examine how specific cultural norms and personal beliefs influence teachers’ attitudes and practices regarding gender equality.

The interview provided further evidence that practice is not necessarily driven by knowledge or understanding gender issues. Teachers often find alternative ways to be more gender-responsive, even when they disagree with official regulations. Their practices prioritize equality and acknowledge the unique needs of girls, even if it requires violating the regulations, breaching statutes and legal directives if necessary.

Dealing with low awareness and resistance is essential for developing a more comprehensive, efficient, and gender-responsive pedagogical setting. Nonetheless, this process must be situated in cultural and social contexts. However, resistance primarily opposes gender concepts and knowledge-based contexts.

In conclusion, the study underscores the importance of closing the gap between knowing and dying as essential for creating an effective teaching ground where gender equity can thrive. In this regard, addressing resistance and ignorance must consider cultural and social contexts (Hamid and Mohamed, 2021, p. 581). As a result, we may have a more inclusive education system that addresses gender-related issues.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the Regional Center for Education and Training Professions Souss-Massa. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AO: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This document has been made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

References

Alasmari, T. (2020). Can mobile learning technology close the gap caused by gender segregation in the Saudi educational institutions? J. Inform. Technol. Educ. Res. 19, 655–670. doi: 10.28945/4634

Belhachmi, Z. (1987). The unfinished assignment: educating Moroccan women for development. Int. Rev. Educ. 33, 485–494. doi: 10.1007/BF00615161

Bendraou, R., and Sakale, S. (2024). Critical pedagogy and gender norms: insights from Moroccan educational settings. Soc. Register 8, 51–66. doi: 10.14746/sr.2024.8.4.03

Bergenfeld, I., Jackson, E., and Yount, K. (2020). Creation of the gender-equitable school index for secondary schools using principal components analysis. Int. Health 13, 205–207. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa032

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brazão, J. P. G., and Dias, A. F. (2020). Relações de género e do corpo na escola: diretivas promotoras de culturas inclusivas para as práticas pedagógicas. Available online at: https://periodicos.uepa.br/index.php/cocar/article/view/3347

Campbell, E. (2013). Ethical teaching and the social justice distraction. Teach. College Record 115, 216–237. doi: 10.1177/016146811311501313

CAWTAR. (2019). Rapport sur la participation des femmes en politique en Algérie et en Tunisie. Centre de la Femme Arabe pour la Formation et la Recherche.

Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental (CESE) - Maroc. (2014). Richesse Globale du Maroc entre 1999 et 2013. Available online at: https://www.cese.ma/docs/richesse-globale-du-maroc-entre-1999-et-2013/ (Accessed May 26, 2025).

Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme-Maroc. (2013). Convention sur l’élimination de toutes les formes de discrimination à l’égard des femmes: État de ratification | Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme. Available online at: https://ccdh.org.ma/fr/comite-pour-lelimination-de-toutes-formes-de-discrimination-legard-des-femmes/convention-sur (Accessed November 11, 2024)

Da Silva, D. Q.. (2013). Educación (des)encantada: pedagogías de género en las prácticas de educación sexual de instituciones escolares de Brasil. Available online at: http://dspace.uces.edu.ar:8180/xmlui/handle/123456789/3435 (Accessed November 11, 2024).

de Oliveira, M. S.. (2016). Reflexões sobre a menina que joga bola e o menino que conta história numa escola estadual de Itajaí.

Dialmy, A. (2000). L’islamisme marocain: de la révolution à l’intégration. Archives Sci. Soc. Religion 110, 5–27. doi: 10.4000/assr.20198

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. (2019). The Arab gender gap report 2020: Gender equality and the Sustainable Development Goals. Availabe online at: https://www.unescwa.org/publications/arab-gender-gap-report

Espinoza, A. M., and Taut, S. (2016). El rol del género en las interacciones pedagógicas de aulas de matemática chilenas. Psykhe (Santiago) 25:1–18. doi: 10.7764/psykhe.25.2.858

Fishbein, M., Hennessy, M., Kamb, M., Bolan, G. A., Hoxworth, T., Iatesta, M., et al. (2001). Using intervention theory to model factors influencing behavior change, Project RESPECT. Eval. Health Professions 24, 363–384. doi: 10.1177/01632780122034966

Gerdin, G., Philpot, R., Smith, W., Schenker, K., Moen, K., Larsson, L., et al. (2021). Teaching for student and societal wellbeing in HPE: nine pedagogies for social justice. Front. Sports Active Living 3:702922. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.702922

Gerntholtz, L., Gibbs, A., and Willan, S. (2011). The African Women’s Protocol: Bringing Attention to Reproductive Rights and the MDGs. PLoS Medicine, 8:e1000429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000429

Griner, A., and Stewart, M. (2012). Addressing the achievement gap and disproportionality through the use of culturally responsive teaching practices. Urban Educ. 48, 585–621. doi: 10.1177/0042085912456847

Hamid, M., and Mohamed, N. I. A. (2021). Empirical investigation into teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a study of future faculty of Qatari schools. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 16, 580–593. doi: 10.18844/cjes.v16i2.5636

Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc. (2020). Taux de féminisation des inscrits par cycle de scolarisation. Site institutionnel du Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc. Available online at: https://www.hcp.ma/Taux-de-feminisation-des-inscrits-par-cycle-de-scolarisation_a3372.html (Accessed November 11, 2024).

Kreitz-Sandberg, S. (2016). Improving pedagogical practices through gender inclusion: examples from university programmes for teachers in preschools and extended education. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 4, 71–91. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v4i2.25782

Leicht, K. T., and Jenkins, J. C. (2010). “Introduction: the study of politics enters the twenty-first century” in Handbook of politics. Handbooks of sociology and social research. eds. K. T. Leicht and J. C. Jenkins (New York, NY: Springer).

Letter to the King of Morocco on His Commitment to Withdraw Reservations to CEDAW|Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2010/04/14/letter-king-morocco-his-commitment-withdraw-reservations-cedaw (Accessed June 17, 2024)

Limboro, C. M. (2018). Influence of teacher pedagogical practices on gender in Nairobi informal settlements and Kilifi County schools, Kenya. J. Educ. Pract.

Mechouat, K. (2017a). Approaching and implementing civic education pedagogies and engagement values in the Moroccan classrooms: gender-based perspectives. Eur. Sci. J. 13:259. doi: 10.19044/esj.2017.v13n7p259

Mechouat, K. (2017b). Towards a zero tolerance on gender Bias in the Moroccan EFL textbooks: innovation or deterioration? Arab World English J. 8, 338–355. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol8no3.22

Miralles-Cardona, C., Chiner, E., and Cardona-Moltó, M. C. (2021). Educating prospective teachers for a sustainable gender equality practice: survey design and validation of a self-efficacy scale. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 23, 379–403. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-06-2020-0204

Miyake, A., Kost-Smith, L., Finkelstein, N., Pollock, S., Cohen, G., and Ito, T. (2010). Reducing the gender achievement gap in college science: a classroom study of values affirmation. Science 330, 1234–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.1195996

Monteiro, S. A., and Ribeiro, P. R. M. (2019). Atuação do pedagogo e as questões de gênero e identidade na educação infantil 15, 93–112. doi: 10.26673/TES.V15I1.12771

National Academies of Sciences (2016). Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8) in Engineering, and medicine, division of Behavioral and social sciences and education, board on children, youth, and families, committee on supporting the parents of young children. eds. H. Breiner, M. Ford, and V. L. Gadsden (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press (US)).

Ouabou, S., and Idrissi, A. (2024). Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence in education: a comprehensive review and future directions. Stud. Comput. Intelligence 1166, 307–317. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-65038-3_24

Ouabou, S., Idrissi, A., Daoudi, A., and Bekri, M. A. (2023). “School dropout prediction using machine learning algorithms” in Modern artificial intelligence and data science: tools, techniques and systems. ed. A. Idrissi (Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland), 147–157.

Pascoe, C. J., and Herrera, A. P. (2018). “Gender and sexuality in high school” in Youth sexualities: Public feelings and contemporary cultural politics. ed. S. Talburt, vol. 2 (Cham: Springer), 301–313.

Rios, P. P. S., and Vieira, A. R. L. (2020). The emerging of a gender discourse in education: the differences in the school space. Revista Tempos Espaços Educação 13, 1–18. doi: 10.20952/revtee.v13i32.13061

Saltzman Chafetz, J. (1999). Handbook of the sociology of gender : Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publisher. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Ulla, M. (2023). Queer pedagogy in TESOL: teachers’ perspectives and practices in Thai ELT classrooms. RELC J.. 1–14. doi: 10.1177/00336882231212720

UNESCO (2022). Global education monitoring report – Gender report: Deepening the debate on those still left behind. Paris: UNESCO.

Xavier, A. K., Andrade, A. S.de, Lima, L. T. S.de, Santos, R. M.dos, and Ferreira, B. C. (2020). O debate de gênero como prática pedagógica: uma análise das produções acadêmicas sobre igualdade de gênero nas escolas entre 2003 a 2014. REVES - Revista Relações Sociais. 3, 14001–14017. doi: 10.18540/REVESVL3ISS4PP14001-14017

Ziv, N (2006). “Interpreting their blood: the contradictions of approaches to menstruation through religious education, ritual and culture in Rabat, Morocco”. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. Available online at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/331 (Accessed November 18, 2024).

Keywords: gender approach, gender pedagogical practices, Moroccan schools, gender disparities, gender stereotypes, inclusive education, equitable environment

Citation: Ouabou S, Achraouaou H, Akhsay R and Outalb M’hand A (2025) Gender pedagogical practices in Moroccan schools: awareness, implementing, and attitudes. Front. Educ. 10:1538827. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1538827

Edited by:

Ying-Chih Chen, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Heesoo Ha, Seoul National University, Republic of KoreaShiyu Liu, Ocean University of China, China

Copyright © 2025 Ouabou, Achraouaou, Akhsay and Outalb M’hand. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Said Ouabou, c2Eub3VhYm91QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Said Ouabou, http://orcid.org/0009-0000-5319-1304

Hassan Achraouaou, http://orcid.org/0009-0003-0170-0789

Rachid Akhsay, https://orcid.org/0009-0009-4970-5662

Ahmed Outalb M’hand, https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0862-2620

Said Ouabou

Said Ouabou Hassan Achraouaou

Hassan Achraouaou Rachid Akhsay3†

Rachid Akhsay3†