- 1Department Health and Sport Sciences, TUM School of Medicine and Health, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany

- 2Department of Sports Education/Sports Didactics, Institute of Sports Science, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Background: The ability to (self)-reflect has been described as a key competence in the teaching profession and is particularly relevant for physical education teachers as they are exposed to complex, unpredictable, and dynamic situations. As an Embodied Reflective Practice, Educational Dance can contribute to the promotion of embodied self-awareness and embodied reflexivity by consciously foregrounding its inherent reflective components. The objective of this study is to explore the relationship between embodied experience and reflection within the narratives of physical education teachers. The study addresses the following research questions: (i) How does the (self)-reflective capacity of the participating teachers manifest in the context of creative movement work? What connections between embodied experiences and potential reflections can be found in the teacher's subjective narrative constructions? (ii) What bodily-kinesthetic experiences are encountered? Which (movement-) moments or experiences stimulate reflection processes, and why?

Methods: The exploratory case study analyzes interview data from physical education teachers (N = 18), who participated in a continuing education course in dance teaching, using qualitative content analysis.

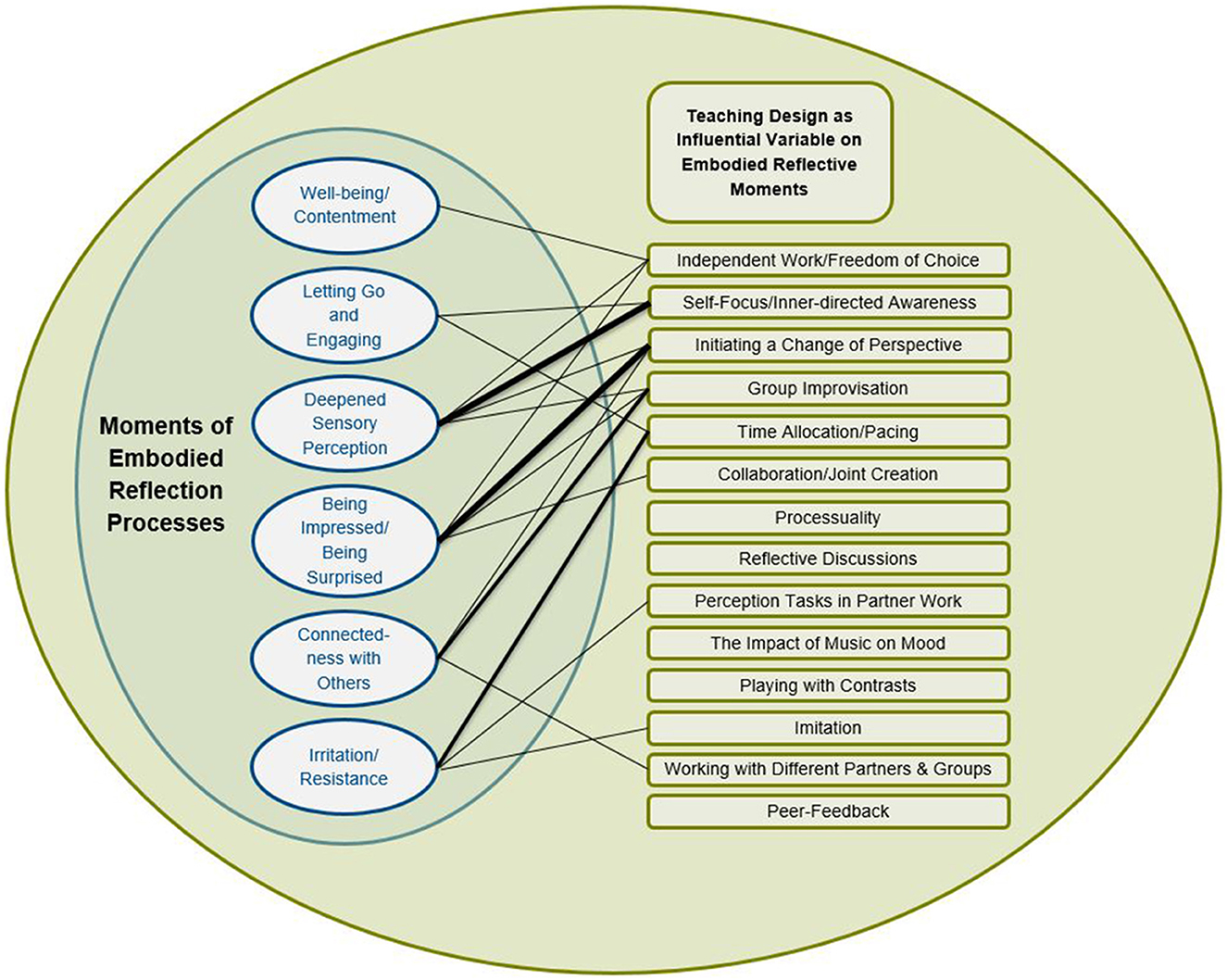

Findings: The analysis reveals two main categories, namely Moments of Embodied Reflection Processes and Teaching Design as Influential Variable on Embodied Reflective Moments. Various moments of embodied reflection processes are identified: Wellbeing/Contentment, Letting Go and Engaging, Deepened Sensory Perception, Being Impressed/Being Surprised, Connectedness with Others as well as Irritation/Resistance. A co-occurrence analysis shows that certain moments occur with specific aspects of the teaching design as influential variables for the respective aesthetic experience.

Discussion: In the exploratory and creative field of Educational Dance examined in this study, reflections are increasingly tied to an aesthetic experience, serving as a stimulus for embodied reflection processes. The study contributes to a deeper understanding of the relationship between embodied experience and reflective processes in the context of Embodied and Aesthetic Education. It offers starting points for the discussion of didactic consequences concerning promoting embodied reflexivity. It points out the meaningfulness of embodied/somatic practices in teacher education, as fostering an embodied self-perception could be a valuable approach to enhancing self-reflection.

1 Introduction

The ability to self-reflect is regarded as a key competence in the teaching profession and is emphasized in both academic and educational policy discourse. As a fundamental interdisciplinary skill that addresses the systematic uncertainty inherent in pedagogical practice, it forms the foundation for both individual teaching development and school development (Combe and Kolbe, 2008; Fat'hi and Behzadpoor, 2011; Hatton and Smith, 1995; Korthagen, 2004; Kultusminister Konferenz, 2019; Postholm, 2008; Tsangaridou and Siedentop, 1995; Wyss, 2013). The teaching profession entails a high degree of responsibility for the developmental and learning processes of children and adolescents (Thißen, 2019), making it essential for teachers to reflect on and justify their actions. Furthermore, encouraging reflection within the teaching profession includes illuminating and questioning personal experiences, assumptions, attitudes, values, goals, and decisions—as well as their impact on one's own teaching practice (Zeichner and Liston, 2013). From a health perspective, the ability to self-reflect also plays a significant role, for instance in recognizing professional boundaries or fostering individual wellbeing (Dauber, 2006; Wyss, 2013). A recent literature review highlights that reflective skills are particularly important for physical education (PE) teachers, as they are exposed to a notably unpredictable and dynamic environment (Azevedo et al., 2022).

In research on self-reflection in the teaching profession, (Schön 1987, 1994) established the concept of the reflective practitioner, linking it to the recognition and resolution of problems with the goal of improving individual teaching practice. Schön's distinction between reflection-in-action (simultaneous with the action), and reflection-on-action (after the action) is particularly prominent. Mohamed et al. (2022) point to the multiple engagements with reflective practice in the educational context and the resulting complexity of the concept. Approaches to reflective practice thus vary among scholars in the field. Leigh and Bailey (2013) propose a more specific interpretation of the concept by introducing Embodied Reflective Practice. They refer to Osterman and Kottkamp's definition of reflective practice, which emphasizes the importance of self-awareness in this process. According to the authors “reflective practice is viewed as a means by which practitioners can develop a greater level of self-awareness about the nature and impact of their performance, an awareness that creates opportunities for professional growth and development” (Osterman and Kottkamp, 1993, p. 19). The concept of an Embodied Reflective Practice is associated with fostering professional development through holistic self-awareness. By placing embodied experience at the center of reflective practice, this approach emphasizes the complex interplays between thoughts, bodily experience, and the environment. Leigh and Bailey argue that by linking embodied self-awareness with reflection, the process becomes purposeful rather than merely self-absorbed. It thus prevents a potential negative cycle of rumination. Reflection requires self-awareness, and these two processes are deeply intertwined: “[S]elf-awareness, mindfulness or sense of embodiment allows the reflective practitioner to be conscious of her own thoughts, the environment, in which she finds herself and the reactions that she has” (Leigh and Bailey, 2013, p. 164). Leigh and Bailey state that promoting embodied self-awareness can enhance reflective practice in teaching, providing educators with valuable tools for professional growth. According to the authors, “[i]t is possible that practices, like somatic education, which educates an individual to become more self-aware, can increase their ability to self-reflect” (Leigh and Bailey, 2013, p. 165). The heightened self-awareness, increased empathy, and awareness of others developed through embodied/somatic practices offer rich sources of data for reflection, fostering deeper insight and understanding. Since reflection is understood as arising from embodied experience and consequently integrates multiple dimensions within the framework of mind-body-environment interactions, it is herein referred to as embodied reflection.

The remarks by Leigh and Bailey on Embodied Reflective Practice in pedagogical settings are closely aligned with current discussions on Embodiment Theory. Their concept is, therefore, still relevant and contemporary. Embodiment provides a lens through which the interconnectedness of body, mind, and environment can be understood as a dynamic, reciprocal process (Tschacher and Bergomi, 2011). Since the early 1990s, Embodiment has not only shaped the field of education, but also philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and language learning, among others. According to the theory, the human mind is understood as embedded within the body, which is integrated into the surrounding environment. Cognitive mechanisms are, therefore, fundamentally linked to a person's interactions with the environment. Since we experience the world and interact with our environment with our body and through our senses, bodily experience plays a central role in shaping our minds (Kosmas and Zaphiris, 2018). The mind is thus understood as part of an intelligent dynamic system that emerges from the body's direct and ongoing interaction with the environment Singh and Narayanan, (2021). In this sense, the term mind-body is also used in treatises on Embodiment Theory, which illustrates the symbiotic unity of this interdependent and communicative network.

Even though Embodiment is a well-established theory concerning the relationship between body, mind, and environment, it still plays a subordinate role in the educational context (Laner, 2021), and “it does not seem to be commonly known in learning and teaching cultures” (Clughen, 2024, p. 736). Dualistic and disembodied assumptions dominate in Western society, rooted in outdated ontological views of human nature, which are in turn reflected in contemporary educational systems. In dualism, mind (subject) and matter (object) exist separately and function independently. The mind was regarded as transcendental and endowed with the power of thought, while the body was treated as an object disconnected from the mind (Singh and Narayanan, 2021). This led to an emphasis on the mind over the body. On the premise of dualism, standard cognitive scientists assert that “the brain is the only producer of cognition” (Kosmas and Zaphiris, 2018, p. 971), which ignores the dependence of the mind on corporeality and the role of embodied experience and bodily interaction with the environment in processes of realization. In the opinion of Nguyen and Larson traditional pedagogy fosters the division of mind and body, regarding the body as a “subordinate instrument in service to the mind” (Nguyen and Larson, 2015, p. 331). In the awareness that “we do not possess bodies, but rather we are bodies making connections to the world” (Nguyen and Larson, 2015, p. 334), pedagogical practice must be reoriented toward the fundamental role of corporeality in knowledge generation.

Research on embodied learning approaches now encourages a new understanding of knowledge generation, presenting a holistic and more integrated view of the human nature. In this context, embodied cognition describes a contemporary learning paradigm that emphasizes the fundamental role of body and movement in learning and cognitive processes (Kosmas and Zaphiris, 2018). Nguyen and Larson define embodied pedagogy “as learning that joins body and mind in a physical and mental act of knowledge construction” (Nguyen and Larson, 2015, p. 332). The connection between body, mind, and environment described in Embodiment Theory is, therefore, constitutive of Embodied Education, “because its major claim is that humans start making sense of the world or learn about the world through embodied experience” (Singh and Narayanan, 2021, p. 216). Embodied Education describes cognition as based on a physical dimension and complexly interwoven with emotional-affective aspects (Francesconi and Tarozzi, 2019). Consequently, research in embodied approaches to learning particularly focuses on the importance of bodily, emotional, and social experience in learning processes (Clughen, 2024).

Some fundamental aspects of understanding what it means to be human and how knowledge is generated, which are integrated into the current discussion of embodiment, can be found in earlier works by authors in phenomenology and educational philosophy (Francesconi and Tarozzi, 2019; Laner, 2021; Thorburn and Stolz, 2023). At the core of phenomenology lies the idea of Leiblichkeit, of “the lived body, the inseparable psycho-physical unity, the body I am, the perceiving (or experiencing) body, the agentive body that moves in action” (Francesconi and Tarozzi, 2019). Dewey's pragmatist notion of experience likewise acknowledges the psycho-physical nature of human engagement with the world (Dewey, 1938)1. As Hohr states, “Dewey's concept of experience allows a holistic approach to education, in the sense that it is based on the interaction between the human being and the world” (Hohr, 2013, p. 25). Importantly, Dewey's philosophy laid the foundation for experiential learning by rejecting the notion that learning is a passive acceptance of facts, instead emphasizing active engagement with experience as central to the learning process. In experiential learning settings, in particular, learners can generate their knowledge based on bodily experience (Horst, 2008). In this context, Stolz criticizes theories of learning inspired by empirical psychology, which understand learning as an empirically investigable causal process. In his opinion, they “fail[] to account for the unity and connectedness of our experiences because we have two orders of reality (rational mind and sensorial body) that are distinct from each other” (Stolz, 2015, p. 477). Rather, our existence as embodied beings means that learning is only possible with and through our lived body as “[t]he embodied approach to cognition holds that mental phenomena arise out of bodily experience” (Singh and Narayanan, 2021, p. 211). Furthermore, Horst argues that “it is the body itself that continuously emerges as a multi-faceted force for making meaning of our experience” (Horst, 2008, p. 1). Consequently, experience orientation plays a major role in embodied approaches to learning so that “learners feel themselves taking part in a community of experience” (Nguyen and Larson, 2015, p. 339). These considerations highlight the conceptual potential of embodiment to address the multilayered nature of human experience within learning. Embodiment holds a particular value for understanding embodied experience in the educational context, as it “can capture the complexities between the intersubjective and incorporeal nature of our experiences and the social and cultural contexts within which we live” (Thorburn and Stolz, 2020, p. 98).

Drawing on the work of (Singh and Narayanan 2021), several foundational principles can be articulated that underpin an embodied approach to education, principles that also summarize the previous explanations on Embodied Education and the role of experience. Central to this perspective is the premise that learners must be granted the autonomy to explore and attend to their environment, including the sensory and affective dimensions of their bodily experience, and be supported in engaging in reflective practices. Equally important is the creation of a supportive and emotionally engaging learning environment in which learners can form meaningful emotional connections with their surroundings. An embodied educational setting is inherently interactive and relational, integrating various objects and social agents to enable the active construction of knowledge rather than relying on unidirectional transmission models. Furthermore, education is conceptualized as a collective practice grounded in the dynamic interplay of verbal and non-verbal communication modalities, encompassing gestures, postures, facial expressions, and symbolic as well as environmental cues. Hence, the way we interact with our environment and reflect on these experiences is becoming the focus of pedagogical interest. This shows the relevance of investigating learning settings and teaching concepts that hold potential to enable embodied, holistic, and thus sustainable learning processes. Empirical research on potentially rich learning contexts can also provide the foundation for developing didactic models that translate the integrated mind-body-environment approach into educational practice.

Embodied Education is closely related to Aesthetic Education in dance, which focuses on sensory-reflective self-awareness in the course of performative practices and experiential learning (Rudi, 2021). Costantino defines Aesthetic Education as follows:

Aesthetic education is the cultivation of aesthetic understanding and the imagination through active engagement with the visual and performing arts. By engaging with works of art from diverse genres and cultures, students develop the ability to interpret and make meaning from an increasing variety of modes of expression, and through arts practice are able to communicate through multiple forms of representation. (Costantino, 2015a, p. 230)

Ye et al. (2025) point out that Aesthetic Education plays a key role in fostering autonomy through self-expression, enhancing competence by encouraging creative development, and strengthening social bonds by promoting collaboration in artistic activities. Aesthetic Education is fundamentally based on aesthetic experience. This type of experience is enriched by the interaction of various modes of perception and expression, along with their reflective integration. Its ability to enhance presence and resonance allows meaning to emerge in sensory and emotionally grounded ways. Instead of simply processing information, aesthetic experience involves touching, moving, and meaningfully engaging in situational, relational, and embodied ways. This highlights its educational significance as a unique way of encountering and understanding the world (Brandstätter, 2013/2012). In this regard, aesthetic experiences serve as the foundational starting point and basis for aesthetic educational processes through which individuals can attain self-clarification. This primarily occurs in encounters with the unfamiliar, non-sensical, and different, as these situations compel individuals to adopt an aesthetic stance. Irritation plays a significant role in this process, as it enables individuals to be liberated from conventional perceptual patterns and habitual modes of expression (Obermaier et al., 2024). Klepacki and Zirfas (2021) also describe aesthetic experience as a boundary-crossing, transitional, or interruptive phenomenon. Consequently, aesthetic experiences hold the potential to initiate transformative and educational processes (Obermaier et al., 2024). In this context, (Rudi 2021) emphasizes their capacity to promote perceptual sensitivity, emotional cultivation, and reflective abilities. Accordingly, aesthetic experience can lead to recognition, even if initially free of a primary attachment to a goal to be achieved (Brandstätter, 2013/2012). Fritsch (2013) also highlights the inherently reflective nature of dance education in its explorative and creative orientation. She refers to a reflexive approach to perceptual sensations as a condition of an aesthetic behavior. Thereby, the ability to sense oneself in movement and stillness plays an important role. This self-awareness serves as a starting point for sensing differences or resistance, which in turn can initiate aesthetic processes through dance.

Dance exists in many different forms, which in turn possibly go hand in hand with different teaching concepts. Rudolf von Laban's work, Modern Educational Dance, focuses on the development of the individual and continues to significantly impact the work of dance teachers today. The aim of dance education in Laban's tradition is not the achievement of artistic or technical perfection, but rather the positive impact of creative activity on a person's personality (von Laban, 1948, 2021). Thereby, an explorative approach encourages an individual and differentiated expression through movement. His work is based on the conviction that motion and emotion, form and content, as well as body and mind, are inextricably linked (Ørbæk, 2021), which builds a bridge to the ideas of an Embodied Education. Educational Dance nowadays is oriented toward the processes of Contemporary Dance. There, somatic practices are fundamental and form an important part of dancers' training (Rimmer-Piekarczyk, 2018). Rimmer-Piekarczyk also points out the emphasis of learning with and through the body and bodily experiences in dance, which goes hand in hand with a self-reflective experience of one's own self:

In the dance learning environment, the body is the primary locus for processing experience and sensory perception is particularly heightened. As such, it seems that the sensing of one's own body, as well as other bodies, is an essential component in facilitating self-reflection in dance, a process that contributes towards one's understanding of self. (Rimmer-Piekarczyk, 2018, p. 98)

In this regard, Klinge (2017) describes dance as a field of experience for individual, cultural, and social reflections. Thereby, the body is the place where experiences are reflected. It provides the sensual basis from which experiences of resistance and difference emanate, thus enabling reflection. The body in Educational Dance is understood as the place where reflection and recognition take place or develop, which is associated with an empathic understanding and consequently incorporates the interpersonal component (Klinge, 2019/2017). In emphasizing the interconnectedness and bidirectional interplays between body, mind, and environment, the term mind-body can also help overcome dualistic terminology in dance education. Accordingly, the immediate dance experience is reflected within the mind-body, which can potentially lead to embodied insights. Educational Dance is, therefore, proposed and investigated as a concrete experiential field enabling Embodied Reflective Practice among PE teachers.

Building upon the principles of Embodied and Aesthetic Education, this study aims to explore the relationship between embodied experience and reflection within the narratives of PE teachers engaged in Educational Dance. The participants' experiences are situated within a professional development program in dance education. Hence, the study seeks to provide a foundation for developing pedagogical frameworks that translate the Embodied Education approach into educational practice. In doing so, it aspires to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how embodied reflective practices can be realized in dance education. The study addresses the following research questions:

(i.) How does the (self)-reflective capacity of the participating teachers manifest in the context of creative movement work? What connections between embodied experiences and potential reflections can be found in the teacher's subjective narrative constructions?

(ii.) What bodily-kinesthetic experiences are encountered? Which (movement-) moments or experiences stimulate reflection processes, and why?

2 Materials and methods

The participants of the study were PE teachers enrolled in the continuing education course in dance teaching from February to June 2023 in Munich/Bavaria2. The course was open for registration to PE teachers online through the official online portal for continuing education for teachers in Bavaria. In the German education system, teachers are required to participate in continuing professional development, which can take place both within schools and through external institutions, such as universities. These external, part-time programs allow teachers to enhance their professional skills while continuing their teaching duties. By offering flexible learning opportunities, this approach ensures that teachers remain updated on current pedagogical trends without interrupting their active roles in the classroom. All teachers (N = 23) participating in the course were informed (verbally and in writing) about the accompanying study (aims, procedures, voluntary data collection, data protection, ethical approval3) and agreed to take part by a written consent. The participants were all female, aged between 25 and 58 (mean age 42 years). Three of the teachers work in primary schools and 20 work in secondary schools. Data were included in the analysis only if participants attended at least three out of four practical workshop days, ensuring that the course's intended process orientation was maintained. Reasons for non-attendance at the second workshop included illness or family commitments. The final meeting was postponed due to illness on the part of the organizers, which led to scheduling problems for some participants. For this reason, only seven participants were able to attend the closing meeting.

2.1 Continuing education course “Creating, Framing, Reflecting”

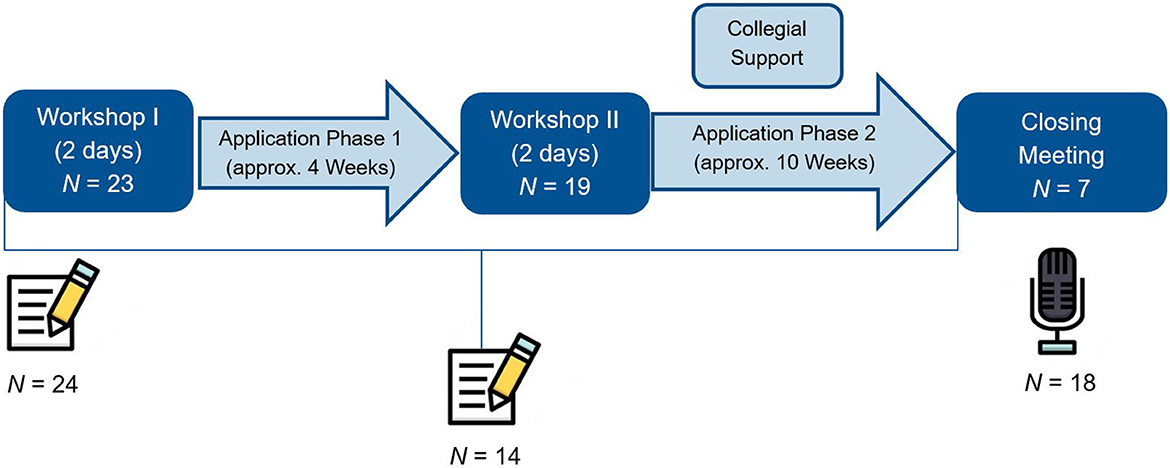

The continuing education course Creating, Framing, Reflecting—Empowerment through individually developing choreographies in dance was developed by two lecturers and researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), Department Health and Sport Sciences. Both are engaged in dance education and personal development in higher education teacher training for PE. The first author (TS) organized the workshop (e.g., participant registration), while the third author (SS) led the practical workshops. The workshop teacher is an experienced university lecturer in the field of dance education based on Rudolf von Laban's work (von Laban, 2021), Contemporary Dance, and somatic practices (Feldenkrais Method, Yoga), as well as personal development. The course approach was practical, process-orientated, comprising different components, which are shown in Figure 1. Key components were the two practical workshops (WS) I and II (duration: 2 days each, 6 h per day), each followed by implementation phases. After WS I, the teachers were asked to integrate experienced tools/methods and tasks as well as new insights into one or more of their dance classes in PE. After WS II, they were invited to implement these in a continuous teaching sequence. Furthermore, the workshop leader offered an additional individual support in the second implementation phase to provide guidance in planning or reflecting on dance lessons in school, which was made use of by two of the participants. The intervention concluded with an exchange meeting to discuss and reflect on experiences gained during the course and the implementation phase.

The training course provided is based on the principles of Embodied and Aesthetic Education. The course was thus oriented toward Contemporary Dance and its methods, which are currently considered especially relevant in the context of Educational Dance. This teaching practice is characterized by the search for new experiential spaces, processes of defamiliarization, and the discovery of the unusual, while also emphasizing the reflective and critical potential of dance (Klinge, 2017). Stressing the self-reliance of the participants in a collective experience formed the base of the course as well as the encouragement to new and/or unfamiliar somatic and aesthetic experiences. Hence, the practical workshop contents and methods are designed to enable exploratory and interactive learning. The intention of this experience-oriented approach was to provide impulses that stimulate a wide range of bodily-kinesthetic, emotional, and social experiences. The focus was on inductive teaching and creative tasks paired with impulses for somatic attentiveness. Improvisation and the engagement in choreography either individually or collaboratively in group settings took precedence over purely imitative tasks. A paper, providing more insight into the contents, methodical fundamentals, and the background concerning dance education can be found in the Supplementary material 1.

2.2 Study design and procedure

In this exploratory case study, data collection was performed through process-oriented reflective diaries (N = 14) and retrospective semi-structured one-on-one interviews (N = 18). This allows insights into individual experiences of the participants in timely relation as well as with a time lag (Figure 1). Moreover, this enables the stimulation and analysis of both written and verbal reflection. Before the first meeting, the teachers also completed an initial questionnaire on their previous experience, goals, and methods in dance lessons (N = 24). To gain a broad range of insights into individual experiences, we invited all teachers that fulfilled the attendance rate to an interview in June or July 2023 (N = 19). N = 18 teachers agreed to be interviewed and N = 14 of them made their diary available. Reasons for drop out were the unwillingness to be interviewed or to provide the diary for analysis. The first author (TS) conducted the interviews4. The interview guideline was tested both during a workshop and in three pilot interviews followed by evaluation. The main interviews lasted an average of 34 min and took place face-to-face (N = 5) or—for practical reasons, e.g., travel time—online via Zoom (N = 13). The teachers were asked to review their reflection diaries before the interview to recall experiences they considered particularly noteworthy, both positive and negative, and to identify topics that had concerned or engaged them. The interviews started with an open question as a narrative impulse (“Tell me about your experiences during the course.”) followed by questions from the subsequent categories: Aesthetic experience during the course, body perception, interaction and relation (within the group and with the course leader), transfer, and self-reflective methods of the course. The semi-structured interview-guideline including the single questions is presented in the Supplementary material 2. In the following, this article focuses on the analysis of the interview data.

2.3 Data analysis

The verbal data from the interviews were transcribed by student assistants according to Dresing and Pehl (2011) in Microsoft Word. The first author controlled all transcripts. We applied qualitative content analysis (QCA) as described by Schreier (2012) to analyze the interview data using the software MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2022). In the first step, part of the data material was analyzed using open coding by the first and second author. This served to familiarize themselves with the material and to gain an initial insight into the relationship between embodied experience and reflection. To obtain a comprehensive overview of the stimulated dimensions of embodied reflection, we searched the interview data for moments in which the teachers refer to embodied experiences, such as reported memories of various emotions, moods, atmospheres, sensations, and bodily-kinesthetic aspects. We examined the material based on these selection criteria (selective coding), which corresponds to the first step of inductive subcategory formation according to the principle of subsumption (Mayring, 2015). If a new passage in the text could not be subsumed into an existing category, a new category was generated. After ~40% of the material had been coded, the category system was revised to ensure consistency and analytical clarity. This was followed by a complete pass through the entire data set using the revised categories. The first author established a first version of the main- and subcategories derived from the data. The coding units were defined in terms of idea units in content. With the involvement of the second author, we undertook an inter-coder reliability testing as part of the sample coding of 20% of the codes in each main category. Cohen's Kappa was substantial with 0.68 for the main category Moments of Embodied Reflection Processes and 0.61 for the main category Teaching Design as Influential Variable on Embodied Reflective Moments (Rustemeyer, 1992). Discrepancies discovered were clarified in discussions and incorporated into the further data analysis5. This approach was applied to both main categories. It should be noted that the coding units of the second main category Teaching Design were predominantly integrated within the coding units of the initial main category Moments. This integration subsequently facilitated the co-occurrence analysis (see Section 3.2).

3 Findings

The open coding process reveals that the teachers describe various qualities of embodied experiences, prompting processes of self-reflection and personal insight. This processes of self-reflection relate to a variety of aspects, such as their relationships with fellow participants or their students, specific aspects of teaching and facilitation, or overarching issues that concern them in their teaching practice (e.g., lack of time for creative approaches due to grading pressures or covering the curriculum content). These descriptions primarily refer to the participants' key experiences during the workshop phases, i.e., in the role of learners, not teachers. Nevertheless, these memorable experiences often serve as the starting point for their application in their own teaching practice. This means that various aesthetic experiences initiate processes of transformation, understood as involving self-reflection and self-recognition. Although the teaching design of the course is characterized by the assumption of a fundamental openness and subjectivity of the dimensions of experience, it becomes apparent that similar patterns of embodied experience are reported across different participants. Embodied Education is particularly concerned with the ways in which mind, body, and environment interact. Certain stimuli from the environment proved to be significant in the participants' narratives as encouragement for reflection. For this reason, the aspects reported by the teachers as influencing their embodied experience are analyzed in more detail. From a subject-specific didactic perspective, and in line with Embodied Education, the learning environment is designed intentionally. Therefore, the second main category is devoted to aspects of Teaching Design as Influential Variable on Embodied Reflective Moments. In summary, the analysis reveals two main categories, namely the Moments of Embodied Reflection Processes and the Teaching Design as Influential Variable on Embodied Reflective Moments, which are presented in the following section. Furthermore, the selectivity of the detected moments is addressed by examining the temporal relationships between them.

3.1 Moments of embodied reflection processes

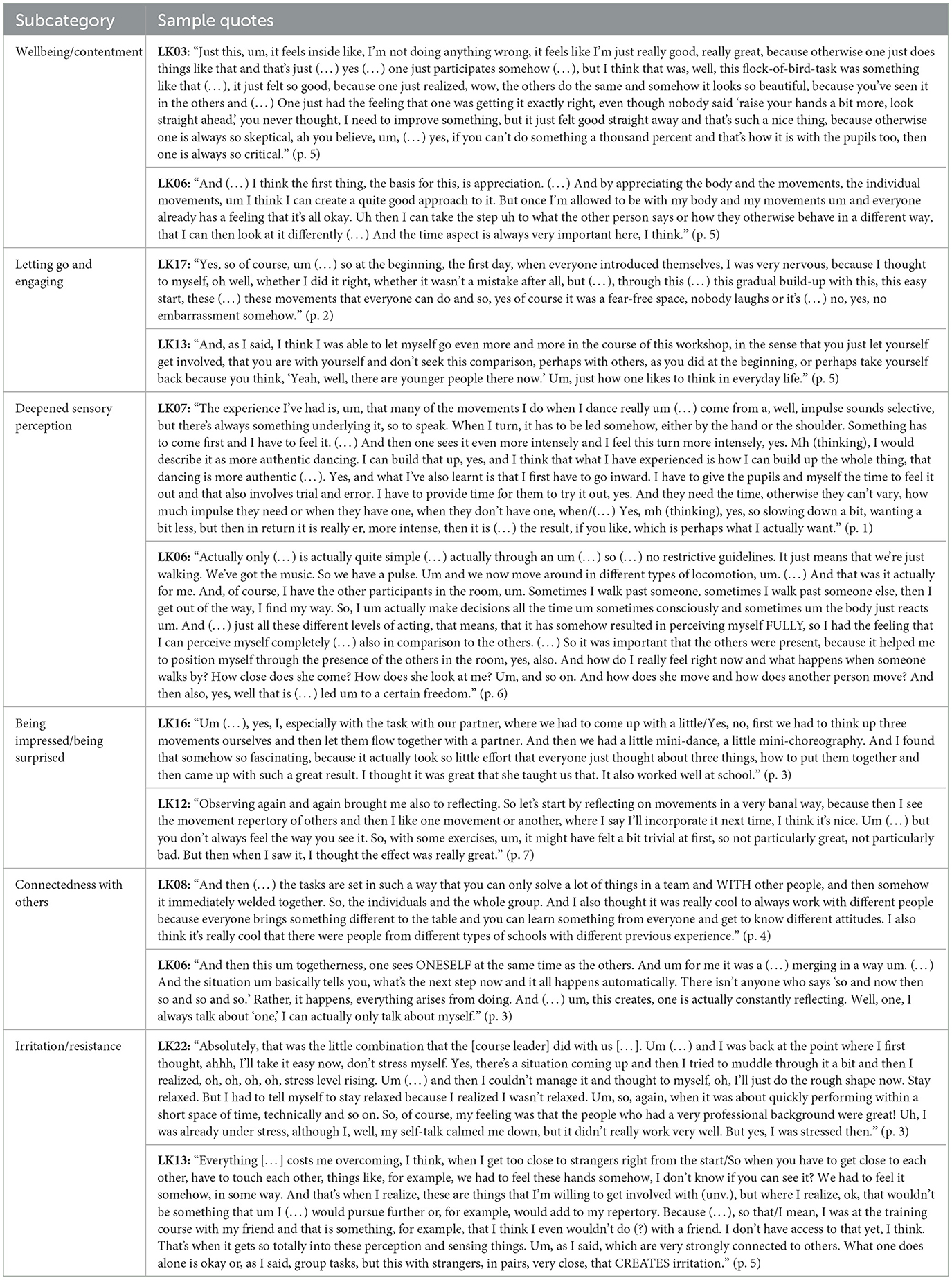

The main category Moments of Embodied Reflection Processes refers to both the situational one-off moments and the recurring moments that have shaped a particular experience as well as their combinations. Six different sub-categories can be identified: Wellbeing/Contentment, Letting Go and Engaging, Deepened Sensory Perception, Being Impressed/Being Surprised, Connectedness with Others, and Irritation/Resistance. The subcategories are explained and illustrated with sample quotes in the following text. In addition, examples of these can be found in Table 1, which presents them in a broader context.

3.1.1 Wellbeing/contentment

The participants describe that they felt a sense of wellbeing during the dance course, which was linked to a feeling of contentment: “I always felt that ‘I had fulfilled the task,' so I always felt good” (LK03, p. 3). This is the case, for example, when they say that they felt free while dancing: “[W]here you can simply […] move freely or I had the feeling that I can do whatever I feel comfortable with” (LK13, p. 5). The teachers also describe other pleasant feelings, such as happiness, joy, relaxation, and being in harmony with themselves or a combination of these, for example, when “the [course leader] somehow brought in an ease or a yes, like a relaxation for me too, by saying ‘Yes, somehow everything is dance”' (LK10, p. 2) or when they report feeling “satisfied, happy um (…) yes, so rather. So, just being in harmony with myself” (LK22, p. 2). They also express the feeling of being accepted with their individual movement possibilities, which in turn helps them to feel content with themselves: “Me, when I'm allowed to do the movements that I CAN do, then I can do them beautifully according to my feelings. I put everything into it and then I feel self-confident” (LK05, p. 3).

3.1.2 Letting go and engaging

The participants speak about how they first had to overcome initial resistance in order to make progress in the course. In this context, the teachers describe several moments in a process of gradually letting go of certain self-limiting attitudes, behavioral patterns, or aesthetic preferences. It is also relevant that they have to let go of familiar movement patterns in order to engage more fully with their creativity in dance: “So, you really notice how, yes, I can't say it any other way, how you let yourself go more, perhaps even trying out strange things” (LK13, p. 6). The participants talk about having to overcome their insecurities, preconceived views or beliefs, as well as subjective evaluations in order to engage with something new and create something new: “[W]ell, it feels like that at the beginning, but you just have to get through it and in the end something really good comes out” (LK11, p. 3). This relates to movement patterns as well as self-assessment of their own dance skills and opinions about dance: “I think it's the self-confidence that you've gained now that there really is a lot to it6. But you have to expand the concept or what you understand by dance, well, what I understood by dance, yes” (LK11, p. 3). Letting go and engaging are also relevant when participants talk about often not knowing what was coming, where it should lead, and being able to engage in the process despite initial uncertainties or skepticism: “So, if you somehow start with something and you somehow get involved with it, you don't know where it's going” (LK10, p. 1) and “to clear your head. And then, I think, it always felt like it was only after three quarters of an hour (…) that it was resolved where the whole thing was going” (LK20, p. 9).

3.1.3 Deepened sensory perception

The participants report that they felt themselves or their own body intensely and/or became more aware of themselves during the dance workshops. For example, teachers report that they perceived their body or certain parts of their body with a particular intensity, especially when it was about “this listening to oneself or feeling oneself and simply feeling oneself from head to toe and being CONSCIOUSLY aware of the body” (LK16, p. 3). Some participants speak about a feeling of flow or a flowing connection between body and mind: “And then I closed my eyes and realized: Hey, now I'm somehow fully in the flow” (LK02, p. 1). Moreover, participants report having turned completely to their own body and body impulses and allowing themselves to be guided by them: “Doing it IN THE MOMENT (…) out of MYSELF, um. So basically I search within myself or I observe. What is my body instinctively doing in this situation? And what comes out of that?” (LK06, p. 3).

3.1.4 Being impressed/being surprised

The participants describe moments that they say particularly impressed them. These moments are often depicted as surprising, “when something happens um, that you wouldn't have thought of before. So, when you were surprised by something, positively, in a positive sense, too” (LK06, p. 8). In this context, the teachers experienced certain aha-moments. For example, they were surprised and at the same time impressed by their own potential or the potential of others: “[W]hat comes out of it or something (…) and that made me, like the others demonstrated, that made me SO/Well, I thought it was so crazy that you can create something out of something so small, yes, I haven't done anything big as far as dancing is concerned and yet it looked cool” (LK03, p. 5). There were also moments when the teachers were surprised by their own reactions in certain situations or their own external impact, for example on a spectator. Impressive moments are also described in which the teachers themselves took the observer position. This is also associated with a certain fascination and descriptions of a wow-moment: “I could have watched it for hours. It was just amazing, the effect it had” (LK08, p. 3), “And this, yes, simply this SEEING too, as it was for us too, this WOAH!” (LK13, p. 2).

3.1.5 Connectedness with others

The teachers report that they felt or developed a special sense of connection or “a sense of unity” (LK09, p. 5) with the group or other participants during the course. For example, when they clearly perceived themselves as “being part of the group” (LK20, p. 3). This was often expressed metaphorically: “merging” (LK06, p.3), “weld[ing] together” (LK08, p. 4), being “absorbed in a group” (LK18, p. 3), “felt carried by the group” (LK22, p. 4), etc. Furthermore, boundaries were felt to blur between people when an initial distance develops into interpersonal closeness: “[Y]ou kind of take down a wall. Slowly. And you regain a sense of calm and appreciation for the other person” (LK10, p. 6). At the heart of the statements is the experience of dancing together, also in a sense of equality and acceptance: “That was also a setting where we all, most of us, I think, accepted each other very much” (LK22, p. 4).

3.1.6 Irritation/resistance

Participants describe moments during the dance course in which they “perceived [their] limits in certain things” (LK10, p. 4). These usually occurred in situations of not being able to or not wanting to, for example when a task presented a particular challenge: “[W]here it also went into these intimate contacts, with eye contact and so on, that I ABSOLUTELY did not want that” (LK09, p. 5). The teachers speak of the perception of inner resistance, inner tension, discomfort, stress, irritation, or excessive demands. The comparison with other participants also plays a role here: “Well, some things just didn't feel quite round, but maybe that's just a comparison, because there were a lot of people who were very much into dancing” (LK18, p. 4). In the context of the course, however, participants were also able to accept their own boundaries: “I would like to express it that way, but I can't! But I can do it THIS way!” (LK10, p. 4).

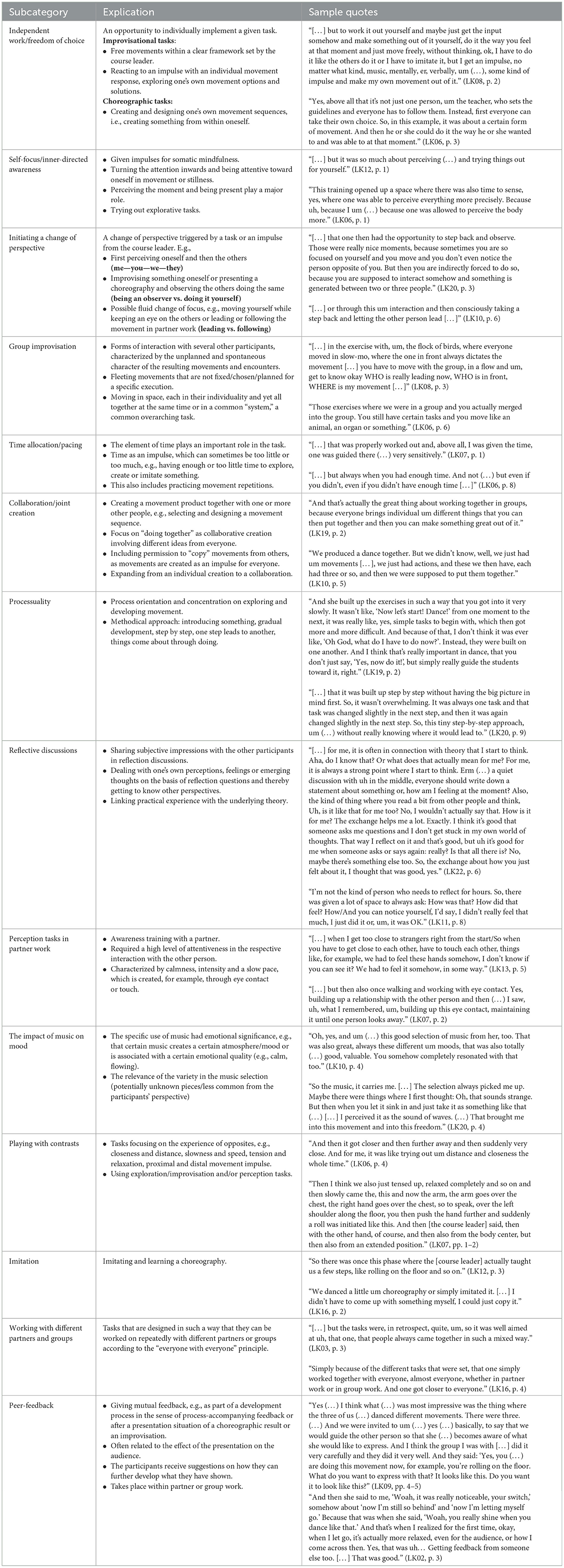

3.2 Teaching design as influential variable on embodied reflective moments

Analyzing the reported moments, it is noticeable that the participants describe aspects of the teaching design that were relevant to the respective aesthetic experience. These aspects are either mentioned directly by the teachers as significant for the aesthetic experience or characterize the moment in question within their descriptions. In the following quote, for example, a teacher explains why the individual creation of movement was a particularly intense experience.

And that task with the postures (…) that was so fleeting and yet right. Because you remembered it again anyway. Hey, that posture was cool. Or I felt comfortable in it. It wasn't so cool, I won't take it, it was weird. And you could always refer back to it, because it was developed by you. […] I think that's why I experienced these freer forms of creation more intensely than learning a choreography. (LK20, p. 7)

The main category Teaching Design as Influential Variable on Embodied Reflective Moments comprises a task-oriented course structure. An overview of the respective subcategories, their explanations, and sample quotes are provided in brief in Table 2. Certain values and attitudes of the course leader form the framework in which the respective tasks take place. Accordingly, the teaching design cannot be seen as completely independent of the teacher, and can only be taught in an authentic way if there is a certain coherence. On the one hand, an open understanding of dance forms the foundation of the course in the sense of “All can be dance.” Even everyday movement can become dance (art). This is accompanied by an appreciation and acceptance of individual movement-(ideas). A “right/wrong” categorization is deliberately avoided in terms of one movement being better or worse than another. Teacher LK10 refers to the open understanding of dance as follows: “She gave you the feeling that you can try things out. Everything is allowed, in the respectful, appreciative way she said it. It's all okay, so this ‘It doesn't have to be this and that,' but it's open” (LK10, p. 4). On the other hand, the course leader sees herself as a guiding companion, which is reflected in a more participant-centered instead of a teacher-centered teaching. Accordingly, she offers various impulses with the aim of opening up a space for exploration and experience with and through movement. As the course leader actively participates in movement tasks, she is perceived as a part of the group by the participants, and, at the same time, as a clear leader who shapes, accompanies, and guides the process: “She took part a lot herself, actually everything. So I didn't feel like I was being watched by her, but simply that she was on the same level as me, and just kind of the same (laughs)” (LK02, p. 3), “So she gave impulses, and then took part, but was more of a participant. And somehow just really played in the background with her open guidelines. And because she always said from the beginning that everyone is a dancer, she created a feel-good space so that you didn't have the feeling that you didn't meet any standards” (LK05, p. 3).

In order to gain an insight into which aspects of the teaching design are potentially associated with which moment, co-occurrences in the data were analyzed using the code-relation-browser in MAXQDA. In this case, it means the occurrence of certain aspects of the teaching design in the identified moments. Figure 2 shows the relationships between the moments and the respective aspects. For example, Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception occur together with the subcategory Self-Focus/Inner-directed Awareness, and Moments of Being Impressed/Being Surprised occur together with the subcategory Initiating a Change of Perspective. Further connections can be seen between Moments of Connectedness with Others and the subcategory Group Improvisation, as well as between Moments of Irritation/Resistance and the subcategory Time Allocation/Pacing.

3.3 Temporal relationships between moments

In the course of the discussion of discrepancies regarding the inter-coder testing, temporal relationships between certain moments became apparent. These can be either simultaneous or successive. The clearest patterns in these relationships are to be demonstrated on the basis of data. A simultaneous temporal relationship appears between Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception and Moments of Connectedness with Others. It is interesting to note that several teachers refer to the same exercise, which is a special form of group improvisation, a so-called flock. In this improvisation, “you are fully attuned to the person in front and the whole group does something together without there being a specific guide, as the guide is constantly changing” (LK18, p. 2).

We had this wonderful exercise with the flock of birds. […] Let's stay in the picture, a bird flies in front, and the others fly behind in a formation, and this creates a synchronicity. And this synchronicity basically arises by paying a lot of attention to the person who is in front, and this attention is not just attention to movement, but it is much more than that. It is the perception of everything that goes with this movement. […] Letting oneself fall into this movement and feeling this unity. Yes, and it really goes beyond the physical […]. (LK09, p. 1)

Yes, that was really such a flow, yes. Well, that you sometimes have when you are totally at one with someone or maybe you have that when you're dancing, when you're dancing as a couple, when it's totally flowing, yes. It was such a flow, and you are a particle in something so big, yes, I think a flock of birds fits quite well. […] Such a sense of being at one with the world, maybe SO. With everyone. I think you rarely experience that. Usually, you're an individual in front of others, always following/asking or something like that, but the fact that you're so absorbed in a group like that isn't actually the case in my everyday life. Maybe even as a teacher it's a bit extreme, yes, because you're always at the front, always directing, always setting the example. (LK18, p. 3)

Both teachers experience the flock as a moment in which they sense themselves intensively as part of a larger unity of people. This is associated with a comprehensive perception of the movement of others and an exceptional experience of their own movement, which is clearly connected to others. In contrast to this simultaneously generated overlap, a successive temporal relationship emerges between Moments of Irritation/Resistance and Moments of Letting Go and Engaging. Here, the experience of resistance forms the basis for the experience of letting go and engaging. The following examples show barriers to be overcome in the form of insecurities and concerns associated with a possible assessment by others. Consequently, the fear of being judged must be surmounted, or at least the participants should not allow themselves to be inhibited by it. By overcoming the initially perceived barriers, the participants can, for example, experience and reflect on improvisational tasks in a positive way. Moments of Irritation/Resistance can thus be successively transformed into Moments of Letting Go and Engaging.

I'm always rather insecure at first, that I don't dare to move so freely. (…) I don't know what it looks like (laughs). Someone might laugh or something. But once one has tried it and someone mirrors one or one can copy the others a bit, look around a bit. Yes, then one somehow becomes more self-confident and (…) yes, self-confident in yourself and that you CAN do it (laughs) (…) and try it. (LK17, p. 3)

Yes, so my first thing that is really decisive for me is that this letting go and um (…) yes, that it doesn't matter at all, um, who is watching or simply this DOING. And that it doesn't matter from what/how I do it, just this feeling and letting go. That was my main thing that I actually took away for myself. And um, that somehow makes it more relaxed. […] So, I no longer have the pressure that I have to do it this way and that way so it will be liked. […] I often had the pressure that I had to do it particularly well and yes. And then, what do the others think and that is somehow gone now. Well, I think that might come back again. It's a task for me to keep reminding myself of that, but it was definitely very helpful to be able to work on myself, yes. (LK02, p. 1)

Resistance is experienced in the freedom to choose one's own movement solution. Thus, these examples show that potential assessment on the part of others is one of the experienced barriers to be considered, and this is not linked to whether there is any kind of evaluation at all. At the same time, it offers potential for self-reflection if these resistances can be perceived or even exceeded. Moreover, another temporal relationship is noticeable between Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception and Moments of Wellbeing/Contentment. This is to be understood in such a way that a Moment of Deepened Sensory Perception can flow smoothly into a Moment of Wellbeing/Contentment or can also overlap directly.

So, for example, where we had our letter, our first letter in different uh areas/That was like/There is something/That was good for me, this exercise, because I had the feeling, ah, ah, ah, and one thing leads to another and suddenly and now I'm immersed in that. And there was such a flow in me, which then also flowed out from the inside to the outside. And of course, that feels very pleasant and warm and harmonious and um, yes, that you CAN do something and empowering, yes, exactly. (LK22, p. 2)

And then also through the fact that one always performed it in front of a group and then stood on stage again, such self-confidence. And somehow, um (…), this um (…) yes, this joy somehow arose. Yes, and then you thought, ‘Oh, now you are so in tune with yourself.' So, then you actually did your movements to the music and you felt in tune with it. (…) And then I was able to forget about everything else, often. Yes, it was a (…) yes, a feeling of joy and, um, of being somehow in the here and now and (…) um (…) yes, a sense of gratitude, I think. Gratitude. That was always so right afterwards, ‘Oh nice that I could somehow feel that now,' like this. (LK10, p. 4).

In both situations, the teachers describe a very intense feeling of being present in the moment, which turns into a feeling of wellbeing during the movement situation. In these cases, the feeling of contentment, in turn, creates a sense of self-empowerment, respectively, self-confidence. In the first example, the adjustment of the feeling of wellbeing can be recognized in the course of the task, whereas in the second example, the focused being-in-the-moment, here during a performance, is directly linked to a feeling of wellbeing.

4 Discussion

4.1 Educational dance as a field for an embodied reflective practice

We identified various moments of embodied reflection processes that were experienced by the participants and could also be expressed in a verbal form. Reflections are thereby increasingly linked to aesthetic experiences that lead to embodied insights, in that they arise from embodied experience. The findings indicate the potential of Educational Dance to foster holistic reflective abilities in connection with concrete embodied experiences. The findings show that the original bodily-kinesthetic, emotional, or atmospheric experience is not lost in the narrated recollection. This may have resulted from the fact that in the course of the teacher training, attention was paid to the differentiation of bodily-sensory perception. Moreover, participants were repeatedly invited to draw their attention to their mind-body, for example, regarding their reactions in various tasks and their chosen options for action. Hence, in the process of moving in Educational Dance, there is a constant communication between bodily-kinesthetic experience, the environmental influences acting on it (e.g., moving interactions with others), and the emerging thoughts, which activate body- and self-awareness in a special way (Ørbæk, 2021). Educational Dance has a special interpersonal nature, which is also clearly reflected in the aspects of Teaching Design that encourage embodied reflection, as described by the teachers. In this regard, teachers emphasize aspects such as Initiating a Change of Perspective (e.g., me—you—we—they, being an observer vs. doing it yourself, leading vs. following), Group Improvisation, Collaboration/Joint Creation, and Reflective Discussions. The fact that subjectivity is embodied and grounded in our engagement with the world makes it possible “that changes in embodied experience have the capacity to transform both subjective consciousness and relationships between subjects” (Reynolds, 2012, p. 87). The potential for transformation is also attributed to aesthetic experiences (Bertram, 2014; Freytag and Theurer, 2020), so that the Moments of Embodied Reflection Processes represent, to a certain extent, occasions or origins of transformation. In the context of (continuing) teacher education, this implies that the integration of somatic methods into dance education enables aesthetic experiences that foster reflexivity, serving as a foundation for personal and professional growth.

Various forms of reflection are addressed: reflection-in-action through aesthetic experiences, and reflection-on-action, as an embodied, verbal practice, both as ongoing components of the process and in retrospect (e.g., reflective discussions, reflective diaries). Furthermore, Embodied Reflective Practice aligns closely with the concept of core reflection proposed by Korthagen and Vasalos (2005), due to its emphasis on body- and self-awareness. Core reflection constitutes a deeper and more impactful form of reflection, as it addresses the teacher's core qualities and fosters greater awareness of the inner reflective levels of identity and mission7 (Korthagen, 2004). According to the authors, emphasizing the relevance of feelings, emotions, needs, and values in reflective processes—and their significance for decision-making—supports more sustainable learning and development. Given that rigid, underlying beliefs about the nature of the teaching profession (e.g., conceptions of teacher and student roles and their relationship) represent a barrier to reflective practice (Hatton and Smith, 1995), the importance of core reflection is further underscored.

Although Educational Dance emphasizes non-verbal communication, verbal reflection on embodied experience constitutes an essential part of the pedagogical approach. Horst highlights the sharing of experiences as an integral part of somatic learning, which emerges from an “embodied dialogue resulted from a focus on the body in tandem with dialogue” (Horst, 2008, p. 4). In this context, narrated memories can be regarded as distilled representations of meaningful embodied experiences. These become accessible to conscious awareness through verbal reflection, even though certain qualities of the experience may remain in the unconscious and may resist verbal articulation. In the teaching profession, it is necessary to make one's own perceptions and decision-making processes comprehensible to others via language, which is particularly important during traineeship (Postholm, 2008). This process is also relevant in the context of continuing teacher education, where the goal is not merely to impart knowledge but to facilitate the transfer of learned experiences into professional practice (Wahl, 2002). An initial analysis of the interview data regarding the application phases indicates that the participating teachers integrated into their own school lessons precisely those practical elements in which they themselves were prompted to engage in embodied reflective processes through an aesthetic experience. Thus, somatic/embodied approaches to teaching and learning do not exclude language. Rather, they offer a more holistic perspective on learning processes by fostering participants' awareness and sensitizing them to the diverse points of reference that arise through embodied experience.

Since promoting the ability to reflect and cultivating a reflective practice is seen as a challenge (Wyss, 2013), working on embodied self-perception could offer a valuable approach to fostering self-reflection. This highlights the relevance of embodied/somatic practices not only in teacher education but also in school settings more broadly. Such practices can serve as a complement to other established methods of reflective practice, such as “‘journal writing,' ‘lesson reports,' ‘surveys and questionnaires,' ‘audio and video recordings,' ‘observation,' ‘action research,' ‘teaching portfolios,' ‘group discussions,' ‘analyzing critical incidents”' (Fat'hi and Behzadpoor, 2011, p. 248). A key distinction between somatic and aesthetic approaches and more conventionally goal-oriented workshops—even those focused on reflexivity—lies in the self-referential nature of primarily purpose-free experiences. In this context, Dauber (2006) cautions that the development of further training programs into purely outcome-driven optimization programs can correlate with exhaustion and unproductiveness. In contrast, the underlying character of somatically oriented formats is more closely aligned with personal development rather than self-optimization. As our findings suggest, we regard Educational Dance as offering considerable potential to support holistic, embodied reflexivity and to contribute meaningfully to the development of an Embodied Reflective Practice. In this sense, we align with Craig and colleagues' position that “embodied knowledge should be intentionally integrated into teacher education and development [programs] and coursework” (Craig et al., 2018, p. 338).

4.2 Aesthetic experience as stimuli for reflection

We identified Moments of Letting Go and Engaging, which stimulated embodied reflection. Participants reported having to overcome preconceived beliefs, personal judgments, and preferences in order to open themselves to novel experiences within the dance context. They emphasized that it was important to let go and engage in the process, especially when they were unsure of what to expect and where things would lead, yet managed to commit to the process despite their initial doubts or skepticism. Engaging in a process is highlighted in Dewey's work as one of the prerequisites for reflexivity (Dewey, 1933; Wyss, 2013). Thereby, Dewey describes open-mindedness as a personal prerequisite for entering reflective processes. Open-mindedness is a willingness to approach a situation with an open mind and to be receptive to new ideas and thoughts. The ability to shift perspectives and consider alternative points of view is also emphasized in this context. With regard to this study, Initiating a Change of Perspective as an aspect of the Teaching Design is identified as an influential variable on embodied reflection processes. Thus, these two aspects of open-mindedness are represented in the data as a basic requirement for reflection. Nevertheless, it is important to note that participation in the training course was voluntary. It can therefore be assumed that the teachers shared a certain basic openness toward the topic of creative movement education. This may well have influenced the experience of Moments of Letting Go and Engaging, although these were often preceded by Moments of Irritation/Resistance.

The data shows that Moments of Irritation/Resistance and Moments of Being Impressed/Being Surprised can stimulate embodied reflection. What these situations have in common is that personal views, convictions, and preferences shaped by previous experiences become apparent—for example, by manifesting as internal barriers or by being destabilized, perhaps even overlaid by surprising new experiences. From the perspective of transformational educational processes, not every perception of meaning necessarily leads to an aesthetic experience; it rather requires an irritation in the sense of resistance or surprise (Koller, 2018; Rudi, 2021). In short, something that stands out from everyday experience. The experience of difference plays a decisive role here. In this study, Moments of Irritation/Resistance are separated from Moments of Being Impressed/Being Surprised in order to do justice to the different emotional emphasis. Compared to the moments that were connected with a surprise or an impression (aha-/wow-moments), the former were associated with rather unpleasant emotions. Participants describe situations where they felt either unable or unwilling and in which they perceived inner resistance, inner tension, discomfort, or stress. These themes (e.g., feeling of inadequacy, self-doubt) also appear in the study of Ørbæk (2021), which deals with the experience of PE student teachers in creative processes in dance. In the teachers' narratives of the present study, the experience of difference manifests itself as a transition from a before-perception to an after-perception that is noticeably dissimilar. However, difference can also represent a special intensity of a momentary perception that breaks through everyday patterns of perception but is more fluid and less ad hoc, e.g., when one's own body is perceived more and more consciously or an intense connection with other people arises. A moment of surprise in the sense of an aha-moment was rather ad hoc in this respect. Craig et al. address moments of surprise when they point out that “embodied knowledge narratively surfaces in luminal moments in personal, professional, and social settings, and that the relationship of embodied knowledge to cognitive knowing often astounds those who experience and identify the physical body as both a lived phenomenon and a somatic object” (Craig et al., 2018, p. 336). This was evident, for example, when participants were emotionally moved by a surprising realization (e.g., the coherence of their own feeling when dancing and the effect on the audience; their own capability to create choreographies from just a small impulse, even in a short time space). These experiences can be understood as liminal moments in which participants' perceptions of their own bodies and their professional agency begin to shift, marking a temporary transition between previous self-concepts and new perspectives shaped by aesthetic-somatic experience.

Self-awareness forms the basis of self-reflection (Fendler, 2003). The findings of this study support theoretical assumptions that Educational Dance opens up a space for self- and body-awareness, as we found Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception as stimuli for embodied reflection. In the descriptions of the participants, there are statements that they turned completely to their own body and their body impulses and that they felt themselves intensely during the dance workshops. These moments occur together with the subcategory Self-Focus/Inner-directed Awareness as an aspect of the Teaching Design. Since aesthetic perception is also about the observation of the process of perception and about ourselves as perceivers, this self-referentiality can be a starting point for self-reflection (Brandstätter, 2013/2012). The importance of moment perception and being present as aspects of the subcategory Self-Focus/Inner-directed Awareness is also emphasized by Gyllensten et al. (2010) and is highlighted as a key point in bodily experiences. In their grounded theory study, the authors also identified a link between body-awareness and wellbeing. They emphasize that being attuned to one's body, sensing balance and physical stability, can foster a greater sense of wellbeing. This shows strong similarity to the temporal relationship found in this study between Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception and Moments of Wellbeing/Contentment. The teachers describe a strong sense of being fully present in the moment, which is connected with a feeling of wellbeing during the movement activity. Moreover, Aesthetic Education fosters the differentiation of sensory perception, which involves dealing (more or less consciously) with one's own patterns of perception and their interpretations (Fritsch, 2013). Focusing on self- and body-awareness can therefore not only stimulate self-reflection but also contribute to wellbeing. As Duberg et al. (2016) explain, embodied experiences facilitate a shift in focus from an outward orientation to an inward perspective, which has the potential to enhance positive self-perception. Moreover, the authors describe the creative approach to movement as the origin of how the perception of oneself can change: In their dance intervention study with female adolescents with internalization problems, they were able to identify Finding Embodied Self-trust that Opens New Doors as the main category of the qualitative content analysis. In the present case study, it also becomes evident that a creative and somatic approach to dance teaching has the potential to enhance positive self-perception, for example, when Moments of Wellbeing/Contentment are accompanied by increased self-confidence and a sense of self-empowerment among the participants (see Section 3.3).

Freytag and Theurer (2020) refer to various structural characteristics of aesthetic experience, although there is no general consensus on them. Some of the characteristics outlined in that work can also be found in the identified moments—such as a distinct emotional involvement, a heightened intensity of the experience, and the element of irritation within the art experience. However, Brandstätter (2013/2012) points out that a one-sided orientation toward the experience of difference runs the risk of excluding other dimensions of aesthetic experience, which are more oriented toward confirmation and affirmation (e.g., listening to familiar music). This study, however, reveals that an intensified awareness of the present moment is perceived as a difference from everyday patterns of perception. This intensification is closely linked to a sense of wellbeing and contentment, thereby aligning with experiences of affirmation, as the relationship between Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception and Moments of Wellbeing/Contentment shows. Both moments are associated with the subcategory Independent Work/Freedom of Choice concerning the Teaching Design. This closely aligns with Deci and Ryan (2000), who emphasize that certain basic psychological needs must be met in order to enhance wellbeing. For instance, individuals need to be able to make autonomous decisions about their actions (autonomy) and to experience their own competence by successfully mastering tasks (competence)—both of which contribute to a sense of self-efficacy. In this context, confirmation and affirmation can also arise through experiences of difference, provided that the didactic design takes the participants' needs into account.

In this sense, the present case study describes how an experience of difference can be represented in the context of creative movement work through various moments of embodied reflection processes. The selectivity involved in distinguishing between potentially overlapping experiential dimensions presented an analytical challenge and was addressed through close collaboration between the researchers. However, the partial lack of selectivity is closely linked to the holistic approach of creative movement education. In this context, Klinge (2019/2017) describes various forms of bodily reflection in the didactic context, which correspond to various exercises for stimulating aesthetic experiences (e.g., repetition, imitation, play, alienation). These do not always promote clearly defined or isolated approaches to learning and understanding with the body, but are instead multisensory and holistic in nature. Accordingly, it is not surprising that we found certain temporal relationships in the sense of overlaps in the data (e.g., Moments of Deepened Sensory Perception and Moments of Connectedness with Others). From a didactic perspective and based on the data, the study findings allow for a more detailed differentiation of embodied opportunities for learning and understanding. Various aspects concerning the Teaching Design as an Influential Variable are identified as relevant for one specific aesthetic experience based on the participants' descriptions. These aspects can be taken into account in dance teaching as well as in teacher training because they can potentially trigger embodied reflection processes. For future research, it would be interesting to investigate what specifically stimulates reflection and personal development in other educational contexts, as the findings of this study underscore the importance of thoughtful didactic planning in creating opportunities for self-development. Nevertheless, the methodological aspects identified here may also be relevant in other educational settings with the intention to foster self-reflection, for instance, in experiential learning environments. One concrete example could be the question of whether experiential learning in nature also plays with contrasts, such as the varying haptic qualities of water, wood, or grass, and what impact such bodily-sensory experiences have on learners. Through the symbolic-aesthetic value of nature, the experience of nature can, in certain ways, become meaningful experience of the self (Gebhard, 2024). Hence, interdisciplinary exchange in the sense of new project and learning formats should be considered.

4.3 Methodological reflection and outlook

Qualitative individual interviews were chosen as the methodological approach in this study. In these, the teachers were asked about their experiences during the course. This led to a conversation about moments that they specifically remember. According to Kroath's (2004) recommendations, narratives potentially open up a more differentiated and deeper reflection based on key experiences. In this study, reflections were frequently associated with specific moments of aesthetic experience. These moments were imbued with meaning by the participants and thus became—at least in part—accessible to verbal expression. Nevertheless, the relationship between aesthetic experience and verbal expression is a central theme of aesthetic discourse, as unique, individual perceptions and generalized concepts confront each other (Brandstätter, 2013/2012). Brandstätter describes the characteristic of aesthetic experiences as an in-between of, for instance, sensuality and reflection, between emotionality and reason, and between the conscious and the unconscious. This means, firstly, that the choice of language as a means of expression already presupposes a transition to consciousness and a certain degree of conceptualization. Secondly, the actual experience must undergo a process of translation in order to be expressed verbally (Brandstätter, 2011). Consequently, the verbal narrative cannot be equated with the wholeness of the actual aesthetic experience. Johnson justifies this process as follows:

The important thing about the meaning of a pervasive unifying quality of any life situation, person, or work of art is that it is felt before it is known. The qualitative unity is what gives rise to any later abstractive distinctions we can note within our experience. Moreover, any attempt to conceptualize that unity will necessarily select out some particular quality and thereby miss the unity of the whole qualitative unity of the situation. (Johnson, 2015, p. 29)

In contrast, researchers in the field of narrative inquiry describe narrative as the closest one can come to lived experience (Craig et al., 2018). However, Embodied Reflective Practice should deliberately include verbal reflection on embodied/somatic experiences (Horst, 2008), even though the act of translating aesthetic experience into language—and thereby narrowing it—must be viewed critically from a more phenomenological perspective.

The question, therefore, arises as to what other methodological approaches might be used to explore embodied reflection and embodied reflective practice in ways that acknowledge the qualitative unity of embodied experience. In this regard, Johnson highlights the value of the arts: “One of the things we value in the arts is their heightened capacity to present the qualitative aspects of experience—qualitative dimensions that we find it extremely difficult to capture in words and concepts” (Johnson, 2015, p. 29). Brandstätter (2011) proposes an expansion of the understanding of verbal language toward a mimetic language that makes itself similar to the art object. She refers to an open language that stimulates the imagination and emphasizes the special role of metaphors. It is interesting to note in this context that mimetic language also plays an important role in dance teaching practice, for instance, when differentiating movement qualities, such as the dynamic aspects of movement (von Laban, 2021). The relationship between metaphorical language and embodied knowledge is also emphasized by Craig et al. (2018). In the context of the present study, the use of metaphors was found in the participants' descriptions, particularly with regard to the Moments of Connectedness with Others (see Section 3). In future interview studies aiming to come closer to the phenomenon of embodied reflection, questions could be more deliberately directed toward the metaphorical description of specific situations. However, Brandstätter (2011) points out that both are justified in aesthetic experience: the sensual, non-conceptual experience, which the mimetic language attempts to approach, as well as conceptual reflection, which requires discursive language.

In this context, Costantino proposes the concept of aesthetic reflection “as a vehicle for the expression of meaning generated in aesthetic experience as well as a manifestation of the actual interpretive process” (Costantino, 2015b, p. 206). The concept incorporates symbolic expressions such as photographs and drawings alongside language, engaging them in a reflective process centered on embodied experience. In the context of research on creative dance, the study by Jounghwa and colleagues includes reflective drawings by students in the data collection and analysis. The participating 10th-grade high school students were asked “to express freely what/how they felt about the creative dance sessions with lines, shading, colors, shapes, objects, and people throughout the program” (Jounghwa et al., 2013, p. 71). They compared the drawings before and after the 8-week dance program based on the analysis by art therapists. With reference to teacher training, Kroath (2004) also emphasizes that different forms of presentation should be encouraged in learning journals, particularly to support the development of reflexivity. He recommends the integration of the following aspects to better understand the (key) situations experienced: observations, reactions, thoughts, feelings, interpretations, hypotheses, explanations, images, and drawings. While the demands for linguistic expression were high in the present case study, they were appropriate for the target group of teachers. In studies with other participant groups, such as children, a different approach would be necessary. In such cases, greater emphasis could be placed on alternative (symbolic) forms of expression, such as drawings or sketches, which could be analyzed alongside (metaphorical) language. Additionally, it should be noted that most of the teachers in this study have several years of professional experience. It has been shown that experts tend to reflect more extensively and in greater detail than novices (Krull et al., 2007). It therefore remains questionable whether the verbal expression of embodied memories would have been equally differentiated if, for example, the participants had been students.