- 1Faculty of Social Sciences, SIMAD University, Mogadishu, Somalia

- 2Faculty of Management Sciences, SIMAD University, Mogadishu, Somalia

In higher education institutions, perceived organizational politics has been linked to adverse organizational outcomes. However, Islamic work ethics that include moral integrity, accountability, and fairness may act as a protective barrier against these detrimental consequences, especially in situations such as Somalia, where Islamic beliefs heavily influence professional behavior. Drawing on the Social Exchange and Conservation of Resources theories, this study explored the influence of perceived organizational politics on academic staff turnover intentions and professional commitment in private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia. Furthermore, this study examines the moderating role of Islamic work ethics in these associations. A quantitative online survey research design was used to collect data from 236 academic staff of private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia. We analyzed the data using SmartPLS version 4 to test the proposed hypotheses using Partial Least Square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The results revealed that perceived organizational politics had a significant positive influence on academic staff’s turnover intention and a significant negative influence on their professional commitment. However, the results showed that the moderating effect of Islamic work ethics was negative but insignificant in the relationship between perceived organizational politics and both academic staff’s turnover intention and professional commitment. This study adds to the existing scholarship on organizational politics within higher education in post-war nations, especially in the Somali setting. This study provides new perspectives on the possible moderating influence of Islamic work ethics in reducing the adverse consequences of perceived organizational politics; however, it is limited.

Introduction

Higher education institutions are crucial in driving socioeconomic development, as globalization increasingly emphasizes the significance of academia in shaping economies (Khan et al., 2018; Mahmoudi and Bagheri Majd, 2021). Attracting and retaining talented academics is essential for graduates and researchers (Lata et al., 2021). However, developing nations face financial and administrative challenges, whereas private universities face increasing competition (Khan et la., 2019; Kathula, 2024). Moreover, globalization has worsened resource scarcity, increased competitiveness, and intensified political dynamics, leading to unclear decision-making processes and increased prioritization of organizational politics, particularly in developing nations because of corruption (Khan and Hussain, 2016; Khan et al., 2018; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019; Asad et al., 2020). Furthermore, higher education institutions (HEIs) worldwide face the persistent challenge of staff turnover, significantly impacting institutional effectiveness and resource allocation (Ahmed et al., 2015), specifically in the Horn of Africa (Kebede and Fikire, 2022). Therefore, examining and understanding the antecedents of turnover intention among academic and administrative staff are crucial for formulating effective retention strategies. An important predictor gaining increasing attention is the perception of organizational politics (POP), which refers to the actions undertaken by individuals to advance their private self-interests, often disregarding the welfare of others inside the institution (Kacmar and Baron, 1999).

Moreover, organizational politics significantly influence corporate decision-making, determining institutional success or stagnation, especially in developing nations, and has expanded significantly in recent decades despite its long-standing dominance in organizational dynamics (Mishra et al., 2016; Khan and Hussain, 2016; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2018; Karim et al., 2021).

Studies have highlighted that organizational politics adversely impact legitimacy, job satisfaction, stress, morale, efficiency, and commitment (Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019; Karim et al., 2021; Lata et al., 2021). In addition, POP foster interpersonal conflict, erode trust, and cause instability (Khan and Hussain, 2016). Self-serving behaviors motivated by limited resources and personal gain hinder employee performance (Malik et al., 2019). Politically driven promotions undermine the quality of education and research, leading to the departure of experienced faculty, knowledge loss, and decreased productivity (Kathula, 2024).

Over the past two decades, high academic staff demand in developing countries has led to high turnover, diverse political perceptions, corruption, and conflicts among faculty members (Khan and Hussein, 2016; Ekawarna, 2019; Lata et al., 2021; Mahmoudi and Bagheri Majd, 2021; Zibenberg, 2021). Researchers are studying how employees perceive organizational politics in politically driven organizations, highlighting that adverse environments can lead to decreased job satisfaction, anxiety, tension, exhaustion, and low commitment (Malik et al., 2019; Ekawarna, 2019; Karim et al., 2021; Zibenberg, 2021).

However, in Somali higher education institutions, perceived organizational politics (POP) are pervasive and characterized by a notable absence of open and equitable mechanisms governing decisions related to employee promotion, compensation, and supplementary benefits. This systemic lack of procedural fairness contributes to elevated rates of turnover among academic staff and diminution of professional commitment within Somalia’s private tertiary education sector.

Given its broader sociopolitical landscape, Somalia’s private higher education institutions provide a compelling context for examining organizational politics and its negative influence on professional commitment and turnover intention. Shaped by post-war challenges, such as weak governance, corruption, and limited policy enforcement, these institutions often operate with minimal oversight, leading to politicized environments characterized by favoritism, inequitable resource allocation, and political interference, negatively impacting faculty morale, turnover intentions, and professional commitment. A deeply rooted Islamic cultural context like Somalia offers a unique lens through which to explore how Islamic work ethics (IWE), which emphasize integrity, fairness, and moral responsibility, might mitigate these adverse effects. This study not only addresses a gap in the literature but also provides practical insights for managing organizational politics in fragile, resource-constrained settings.

Organizational politics research is gaining attention due to its potential to cause stress, job dissatisfaction, productivity decline, and turnover in education, particularly in developing countries, leading to adverse outcomes like financial loss and poor performance (Javeda and Ishakb, 2019; Asad et al., 2020; Zibenberg, 2021). African universities face corruption, political abuse, and tribalism, leading to staff strikes, equipment shortages, and discipline (Ekpenyong and Ojeaga, 2022). Organizational politicization, partisan politics, and poor leadership result in low morale, staff turnover, and reduced educational quality (Kathula, 2024).

Private universities in Mogadishu’s academic performance are negatively impacted by a lack of competent individuals, poor administrative staff, limited learning resources, and the need for more research publications (MoECHE, 2022; Mohamed et al., 2024). Although extensive research has explored the impact of perceived organizational politics on various employee outcomes, few studies have specifically examined its effects on professional commitment and turnover intention within educational institutions, particularly in the context of Somali and the moderating role of Islamic work ethics.

Although extensive research has explored the influence of perceived organizational politics (POP) on diverse employee outcomes, few studies have specifically examined its impact on academic turnover intention (AST) and professional commitment (PCO) within educational institutions, particularly Somalia. Additionally, the moderating role of Islamic work ethics (IWE) in this relationship remains under-explored and under-researched. Earlier research has explored how IWE moderate the association between POP, job involvement, satisfaction, and commitment (Khan et al., 2019). Furthermore, past studies have reported that perceived organizational politics increases employee turnover intention (Mosquera et al., 2024). Additionally, a study conducted by De Clercq et al. (2023) reported that POP has a negative and significant effect on commitment. Rawwas et al. (2018) examined the moderating effect of IWE on the relationship between employees’ perceptions of organizational politics, turnover intention, job satisfaction, and recklessness behavior. However, these studies primarily focus on corporate or non-academic settings, overlooking the unique contextual and cultural dynamics of higher education institutions, particularly in the Horn of Africa. Building on this gap, our study asserts that IWE play a crucial role in mitigating the adverse effects of POP on academic staff. Specifically, employees who adhere to strong Islamic ethical principles, emphasizing integrity, perseverance, and collective well-being, are more likely to resist the negative psychological effects of workplace politics. As a result, IWE weaken the positive association between POP and turnover intention, while buffering its negative impact on professional commitment. By fostering ethical resilience and intrinsic motivation, IWE promote a sense of responsibility and engagement, counteracting the demotivating effects of organizational politics.

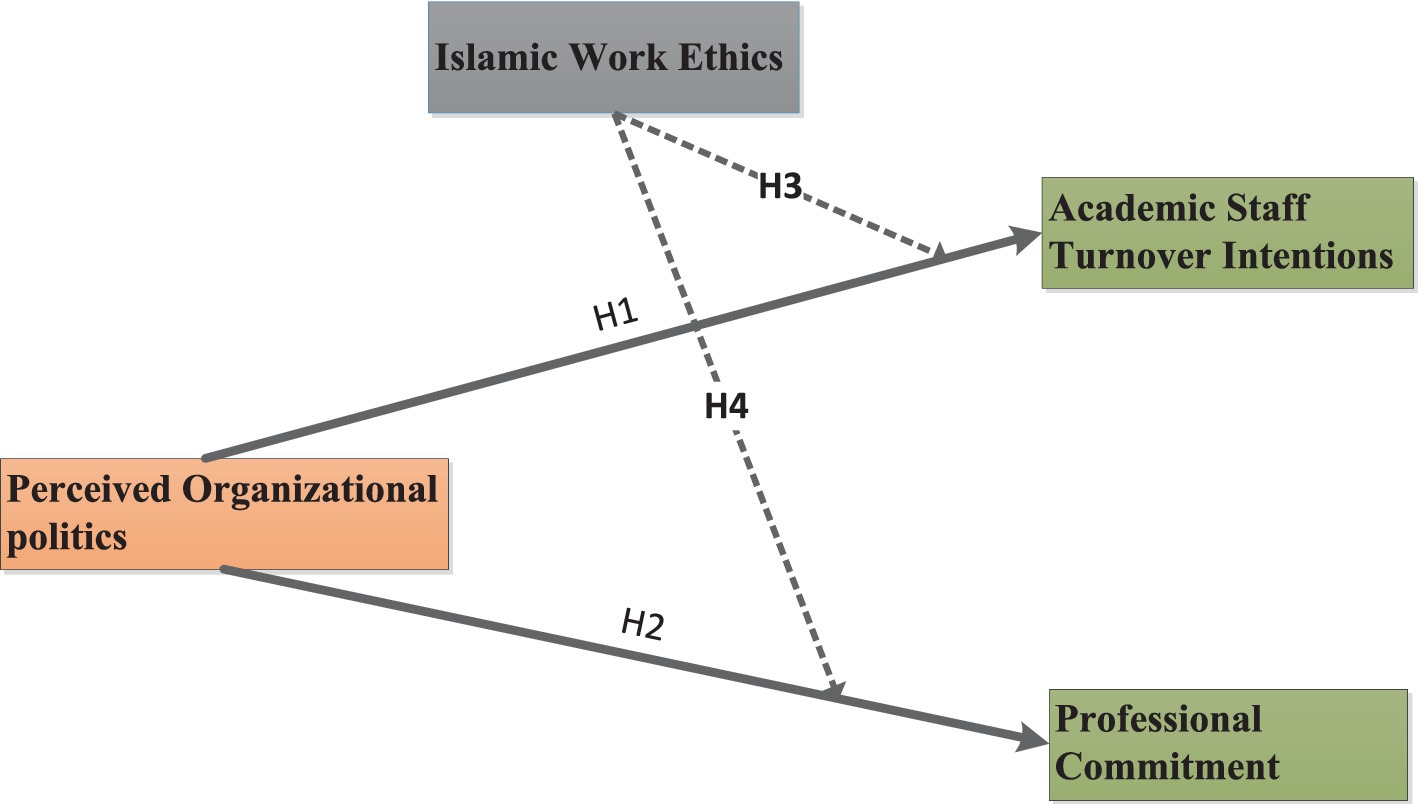

However, all of these studies were conducted in either developing or developed countries, with no focus specifically on the Horn of Africa and particularly on Somalia within an educational context. To the best of our knowledge, no prior research has examined the moderating effect of Islamic work ethics on the relationships between perceived organizational politics (POP), academic staff turnover (AST), and professional commitment (PCO) in private universities in Somalia using a single, comprehensive model (see Figure 1).

This study contributes to scholarly discourse on organizational behavior and ethics in higher education institutions. Theoretically, it extends the application of Social Exchange Theory (SET) by examining how perceived organizational politics (POP) influence academic staff turnover intentions (AST) and professional commitment (PCO) within Somali higher education institutions—an underexplored post-war context. SET suggests that ethical work environments foster reciprocity, enhancing commitment and reducing turnover. Furthermore, this study incorporates the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, which reinforces the model by explaining how Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) help employees preserve psychological resources. By mitigating workplace stressors, IWE reduce turnover intention and enhance professional commitment. By integrating these theoretical lenses, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between organizational politics, ethical work values, and employee outcomes in non-Western educational institutions. Moreover, the study examined the role of Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) as a moderating construct in the relationship between POP and turnover intention and commitment in a single model. This study enriches SET by providing insights into the interaction between ethical principles and organizational dynamics in non-Western settings. Furthermore, this study contributes to the practical application of organizational behavior research in higher education institutions. The results offer administrators and human resource managers in higher education institutions valuable insights into devising targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of POP and improve employee retention. HEIs can establish a work environment that is more supportive and engaging based on the values of their workforce by comprehending the influence of IWE on employee attitudes and behaviors. By using this information, it is possible to create human resource policies and management strategies that foster a more productive work environment. Hence, this study seeks to analyze the influence of POP on academic staff turnover intentions (AST), professional commitment (PCO), and the possible moderating role of IWE in private universities in Mogadishu (see Figure 1). This study seeks to answer four (4) following specific research questions:

1. How does perceived organizational politics influence the turnover intention of academic staff at private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia?

2. How do perceived organizational politics affect the professional commitment of academic staff at private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia?

3. Does Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) moderate the association between perceived organizational politics and turnover intention among academic staff at private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia?

4. Does Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) moderate the association between perceived organizational politics and professional commitment among academic staff at private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia?

Literature review

Perceived organizational politics

Organizational politics refers to self-serving behaviors, power acquisition, covert agendas, and influences on resource allocation, often clashing with organizational interests and disrupting workplace dynamics (Mishra et al., 2016; Malik et al., 2019; Ekawarna, 2019; Lee, 2024). It prioritizes personal gains over collective welfare, resulting in adverse outcomes (Asad et al., 2020; Zibenberg, 2021; Karim et al., 2021; Lata et al., 2021; Khairy et al., 2023). This study conceptualizes organizational politics as self-serving behavior aimed at acquiring power and manipulating resources.

While often perceived negatively, organizational politics also encompasses positive aspects and plays a crucial role in effective leadership (Mahmoudi and Bagheri Majd, 2021). Specifically, it comprises four dimensions: reactive, reluctant, strategic, and integrated decision making (Mishra et al., 2016; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019). Furthermore, perceived organizational politics includes general political behavior, passive support, and perceived inequities in remuneration and rewards, characterized by self-serving actions for goal attainment (Karim et al., 2021). Building on this framework, this study examines the influence of perceived organizational politics from three distinct perspectives: general political behavior, going along to get ahead, and pay and promotion.

Organizational politics significantly impacts organizational decisions, stress levels, career advancement, power, goals, and behavior (Mishra et al., 2016; Ekawarna, 2019; Zibenberg, 2021). Faculty members in the academic sector, particularly in developing nations, frequently navigate partisan politics, facing tension, limited opportunities, intense competition, and ineffective institutional strategies (Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019; Mahmoudi and Bagheri Majd, 2021). Notably, Somalia’s academic landscape shares strong sociocultural connections with these contexts, making it a relevant setting for examining the impact of organizational politics.

Despite these challenges, organizational politics in higher education helps reduce corruption by focusing on budgets, administrative autonomy, structures, and decision-making processes (Mahmoudi and Bagheri Majd, 2021). Promoting professionalism and discouraging harmful political actions can contribute to institutional integrity (Mishra et al., 2016). While research emphasizes micro- and macro-level approaches, a multilevel perspective is essential. A comprehensive analysis is needed to understand its influence on specific outcomes, especially in non-Western contexts, such as Somalia. This study addresses this research gap by analyzing the micro-level impacts of perceived organizational politics on staff turnover intentions and professional commitment within private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Perceived organizational politics and academic staff turnover intention

Turnover intention refers to employees’ deliberate or inadvertent decisions to depart their organization, and is frequently influenced by psychological or physical withdrawal (Ekawarna al., 2016; Ekawarna, 2019; Lee, 2024). Within the context of organizational politics, physical withdrawal is emphasized (Mishra et al., 2016). Employee turnover intention predicts the probability of job change and constitutes a critical indicator of actual resignation decisions (Lata et al., 2020; Mohamed et al., 2024). Accordingly, this study defines employee turnover intention as an employee’s voluntary contemplation of leaving their organization.

As a key measure of organizational effectiveness, turnover intention is shaped by various factors including job satisfaction, workplace stress, demographics, compensation, and social adaptation (Ekawarna, 2019; Mohamed et al., 2024). Notably, heightened perceptions of organizational politics can lead to diminished job satisfaction and increased turnover rates (Asad et al., 2020). In this regard, the present study explores the relationship between perceived organizational politics and turnover intentions of academic staff in private universities in Mogadishu.

Furthermore, organizational politics significantly affects employee attitudes and behaviors, increasing stress, job dissatisfaction, and potential turnover (Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019). This negatively impacts organizations, resulting in high turnover rates, reduced commitment, and poor performance, particularly in the public sector (Mishra et al., 2016; Malik et al., 2019).

Furthermore, organizational politics negatively impact individuals and organizations, resulting in stress, conflicts, and increased turnover intentions (Khairy et al., 2023; Mohamed et al., 2024; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019). Previous research has demonstrated positive associations between organizational politics and employee outcomes, such as turnover intention and job anxiety, while revealing negative associations with commitment and job satisfaction (Mishra et al., 2016; Karim et al., 2021).

In the current study, we utilized Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964) to explain the relationship between perceived organizational politics (POP) and academic staff turnover intention, which posits that workplace relationships are governed by reciprocal exchanges in which employees assess the costs and benefits of their organizational environment. In line with this framework, prior studies (Haleem et al., 2023; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019; Mishra et al., 2016) suggest that perceived organizational politics heightens turnover intention by undermining employee trust and perceived fairness, thereby disrupting reciprocity norms. When employees perceive organizational politics to be pervasive, they may perceive a breach in social exchange relationships, leading to an increased likelihood of turnover intention.

Despite extensive research on organizational politics and its negative impact on worker turnover rates, there remains a need to examine its influence on turnover intention within academic institutions in developing countries (Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019). This study investigates the relationship between organizational politics and turnover intention in Mogadishu’s private universities, providing a unique, context-specific analysis that has been previously underexplored in the literature. Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Perceived organizational politics is significantly and positively associated with academic staff turnover intentions.

Perceived organizational politics and professional commitment

Organizational commitment refers to a person’s allegiance to a social system, whereas professional commitment denotes a psychological attachment to one’s occupation (Utami et al., 2014; Haleem et al., 2023; Lee, 2024). Committed individuals demonstrate belief in their objectives, expend effort, and desire to remain in their profession, although a precise definition remains elusive (Donald et al., 2016; Malik et al., 2019; Haleem et al., 2023). In this study, organizational commitment is conceptualized as an employee’s psychological attachment to the organization in which they are employed.

The conceptualization of commitment has evolved over time, with several theoretical models emerging in the 1980s and the early 1990s. The three-component model, comprising affective, normative, and continuance commitments, remains widely recognized. These dimensions reflect an individual’s emotional attachment to the organization, perceived costs of leaving, and sense of obligation to stay (Utami et al., 2014; Donald et al., 2016; Haleem et al., 2023). Given its theoretical significance, this study examines institutional commitment from the following perspectives: affective, continuance, and normative commitment.

Beyond theoretical constructs, organizational commitment plays a crucial role in enhancing workplace performance, reducing turnover, and improving overall organizational effectiveness, particularly in competitive business environments (Utami et al., 2014).

Moreover, it fosters employee loyalty, facilitates skill development, and promotes knowledge dissemination, even in challenging work environments characterized by mistrust and political tensions (Donald et al., 2016; Malik et al., 2019).

However, research indicates that employees’ perceptions of organizational politics can significantly undermine commitment, erode trust, and diminish overall job satisfaction (Utami et al., 2014; Malik et al., 2019). Specifically, studies highlight an adverse relationship between perceived organizational politics and commitment constructs, including affective, continuance, and normative commitments. Conversely, a positive correlation exists between these commitment dimensions, suggesting that strengthening one aspect of commitment can reinforce the others (Donald et al., 2016; Haleem et al., 2023; Kha et al., 2017).

Furthermore, to explain the relationship between perceived organizational politics (POP) and employee commitment in academia, we used Social Exchange Theory (Blau, 1964), which emphasizes reciprocal exchanges based on trust and fairness. When faculty members perceive high levels of politics (favoritism, self-serving behaviors, and power struggles), they disrupt trust, lower perceived organizational support, and diminish their sense of obligation, leading to reduced commitment (Malik et al., 2019). Empirical evidence confirms that POP negatively affects affective, continuance, and normative commitment, weakening faculty members’ engagement and institutional loyalty (Donald et al., 2016; Haleem et al., 2023; Kha et al., 2017). Consequently, politically charged academic environments undermine professional commitment by eroding the expected reciprocity between faculty members and their institutions.

Despite extensive research, the influence of perceived organizational politics on commitment in higher education institutions remains a critical determinant of institutional success (Donald et al., 2016). However, existing literature largely overlooks the impact of perceived organizational politics on professional commitment within non-Western educational contexts, particularly in Somalia. To address this gap, this study examined the effect of perceived organizational politics on academic staff commitment in Somalia’s private higher education institutions in Mogadishu. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived organizational politics is significantly and negatively associated with professional commitment.

The moderating role of Islamic work ethics in the relationship between perceived organizational politics, professional commitment, and turnover intentions

Islamic Work Ethics are a set of principles and belief systems derived from the Qur’an and hadith related to labor that governs professional behavior (Rawwas et al., 2018). It is a set of values for the workplace influenced by Islam and governed by shariah, which promotes ethical practices in the workplace (Nauman et al., 2023; Usmani, 2024). This study defines Islamic work ethics as a set of beliefs and values derived from the Qur’an and Sunnah regarding hard work.

Islamic Work Ethics emphasizes diligent efforts to cleanse sins and achieve substantial nourishment through hard work (Usmani, 2024). It has five characteristics: (1) righteousness, trustworthiness, honesty, and diligence; (2) devotion; (3) conviction; (4) social duty; and (5) equality and diversity, transcending motivation theory to inspire employees in both life and afterlife (Rawwas et al., 2018; Usmani, 2024). This study investigates the effect of five traits derived from Islamic Work Ethics: Righteousness, Devotion, Conviction, Social Duty, and Equality and Diversity.

It promotes loyalty, honesty, integrity, responsibility, fairness, respect, hard work, dedication, punctuality, and fulfillment of obligations, fostering a culture of fairness, knowledge sharing, and social welfare (Rawwas et al., 2018; Javeda and Ishakb, 2019; Nauman et al., 2023; Usmani, 2024). The global presence of Islam has led to increased research on Islamic work ethics (Nauman et al., 2023). A comprehensive analysis is required to examine its influence on specific outcomes, especially in contexts such as Somalia.

Islamic scholars have studied the effects of Islamic Work Ethics on motivation, commitment, dedication, and job turnover intentions (Javeda and Ishakb, 2019). They find it relevant in Muslim communities, enhancing employee motivation and reducing resignations, while discouraging unethical behavior and wealth accumulation (Nauman et al., 2023; Usmani, 2024). However, it is negatively associated with counterproductive work behavior (Javeda and Ishakb, 2019). Further research must thoroughly examine the correlation between organizational political perceptions, commitment, and turnover intention (Lee, 2024). The research gap persists, as no studies have investigated the moderating role of Islamic work ethics on the relationship between perceived organizational politics, commitment, and turnover intention. Therefore, our current study proposes that Islamic work ethics (IWE) may moderate the relationship between perceived organizational politics, turnover intention, and professional dedication among faculty members in educational institutions. Islamic work ethics emphasizes values such as integrity, trustworthiness, and equity, which can reduce the negative effects of organizational politics by fostering a more ethical and supportive workplace environment (Caniago and Mustoko, 2020). This ethical framework is expected to lower turnover intention and enhance the professional commitment of the university staff.

Grounded in the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), this study explains how Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) moderate the negative impact of perceived organizational politics (POP) on academic staff turnover intention and professional commitment. By fostering resilience, intrinsic motivation, and ethical responsibility, IWE function as a psychological and moral resource that alleviates stress and prevents resource depletion caused by workplace politics. Employees with strong IWE perceive work as a moral obligation, which reduces turnover intentions and sustains commitment despite political adversity (Ali and Al-Owaihan, 2008). By reinforcing ethical perseverance and mitigating the adverse effects of POP, IWE buffer against commitment erosion and discourage withdrawal behaviors, ensuring that academic staff remain engaged and committed. Moreover, Islamic Work Ethics (IWE), rooted in Islamic principles of fairness, accountability, and moral integrity, uniquely moderates organizational politics by fostering intrinsic motivation and a strong ethical compass, discouraging manipulative or self-serving behaviors (Ali and Al-Owaihan, 2008; Yousef, 2001). Unlike ethical leadership, which relies on role modeling, or perceived organizational support (POS), which hinges on socio-emotional fulfillment, IWE emphasizes religious and cultural values, leading employees to prioritize ethical conduct over personal gain (Brown et al., 2005; Eisenberger et al., 1986). This framework shapes perceptions of fairness and justice, often causing resistance to unethical political practices, whereas ethical leadership and POS influence behavior through extrinsic mechanisms like leader actions or organizational rewards (Vigoda-Gadot and Talmud, 2010).

Organizational politics negatively impacts job satisfaction, commitment, performance, and turnover intention (Malik et al., 2019; Javeda and Ishakb, 2019). Islamic work ethics can mitigate stress, boost motivation, and reduce turnover intentions (Ekawarna, 2019; Karim et al., 2021). Moreover, earlier research has reported that IWE can reduce the negative impact of perceived organizational politics on employee commitment. For instance, Khan et al. (2019) found that Islamic Work Ethics mitigate the adverse effects of organizational politics, helping sustain employee commitment.

Therefore, this study examines the potential moderating influence of Islamic work ethics on the relationship between perceived organizational politics, academic turnover intentions, and professional commitment in private universities in Mogadishu. The moderating role of Islamic work ethics is yet to be extensively explored in the existing literature, particularly in the context of developing nations such as Somalia. To fill this gap, this study extends theoretical insights by testing these relationships in a non-Western cultural setting. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H3: Islamic work ethics negatively moderate the relationship between perceived organizational politics and academic staff turnover intentions, such that higher levels of Islamic work ethics reduce turnover intentions.

H4: Islamic work ethics negatively moderate the relationship between perceived organizational politics and professional commitment, with higher levels of Islamic work ethics weakening the negative association.

Methodology

Design, procedure, and participants

This online cross-sectional quantitative design study focused on academic staff at private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia to examine the influence of perceived organizational politics on academic staff turnover intention and professional commitment. Additionally, this study investigates the moderating effect of Islamic workplace ethics on this relationship. To verify the hypothesized model, we used SmartPLS 4.1.0.9, with partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The selection of Mogadishu as our research site stems from its unique position in Somalia’s higher-education landscape. This city houses the nation’s sole public university alongside 67 private institutions, making it the epicenter of tertiary education in the country. Furthermore, organizational politics significantly influence decision-making processes in private universities. To establish an appropriate sample size for this study, we used the web-based statistical quantitative sample size estimator for structural equation Modeling (SEM) developed by Soper (2024). Specific parameters were employed: the desired p-value level of 0.05, a statistical power of 0.8, and an expected effect size of 0.30 (large). This study’s structural model incorporated five unobserved variables and 23 observable indicators. The computed results of this study indicated a minimum sample size of 166 participants. Notably, the sample size exceeded the computed lowest cutoff, thereby satisfying the required sample size criterion.

The principal researcher submitted a formal request to the Ethics Committee of Simad University to obtain ethical approval before commencing data gathering. This committee offered ethical approval at Simad University, Mogadishu, Somalia.

Before disseminating the questionnaire to the intended target population, we conducted a pilot study with a small group of academic staff (N = 20) to evaluate the comprehensibility and suitability of the study instruments. Participants unanimously confirmed the comprehensibility and relevance of the questionnaire items, eliminating the need for modification. Thus, the original English version of the adopted items from previously validated and reliable studies was retained with no modifications. To evaluate the reliability of the individual items within the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was used. The aggregate survey items yielded a value exceeding 0.70, which was deemed acceptable, based on the criteria established by Hair et al. (2022).

A total of 500 online surveys were disseminated to academic personnel at the targeted universities via various digital communication platforms including WhatsApp groups, Telegram, Facebook, and email. Previous studies have suggested that utilizing digital media network services for data collection is an effective and suitable method (Tian et al., 2023). To enhance the response rate, a snowball sampling technique was implemented, wherein each academic staff member was requested to propagate the survey through their digital social media networks. The data collection phase was initiated on September 14, 2024, at 13:45 Eastern Africa Time (EAT) and terminated on October 8, 2024, at 16:16 EAT. Online survey data compilation incorporated a survey cover note that elucidated the study’s objectives and emphasized the voluntary nature of participation. This note explicitly states that declining to participate in the study would not result in any adverse consequences. Furthermore, the cover note provided assurances regarding the confidentiality of responses and protected participants’ anonymity. The researchers also secured written informed consent through an online survey cover note, ensuring compliance with ethical standards. After 3 weeks, our research team sent follow-up communication messages to urge and remind the study participants to complete the designated questionnaires.

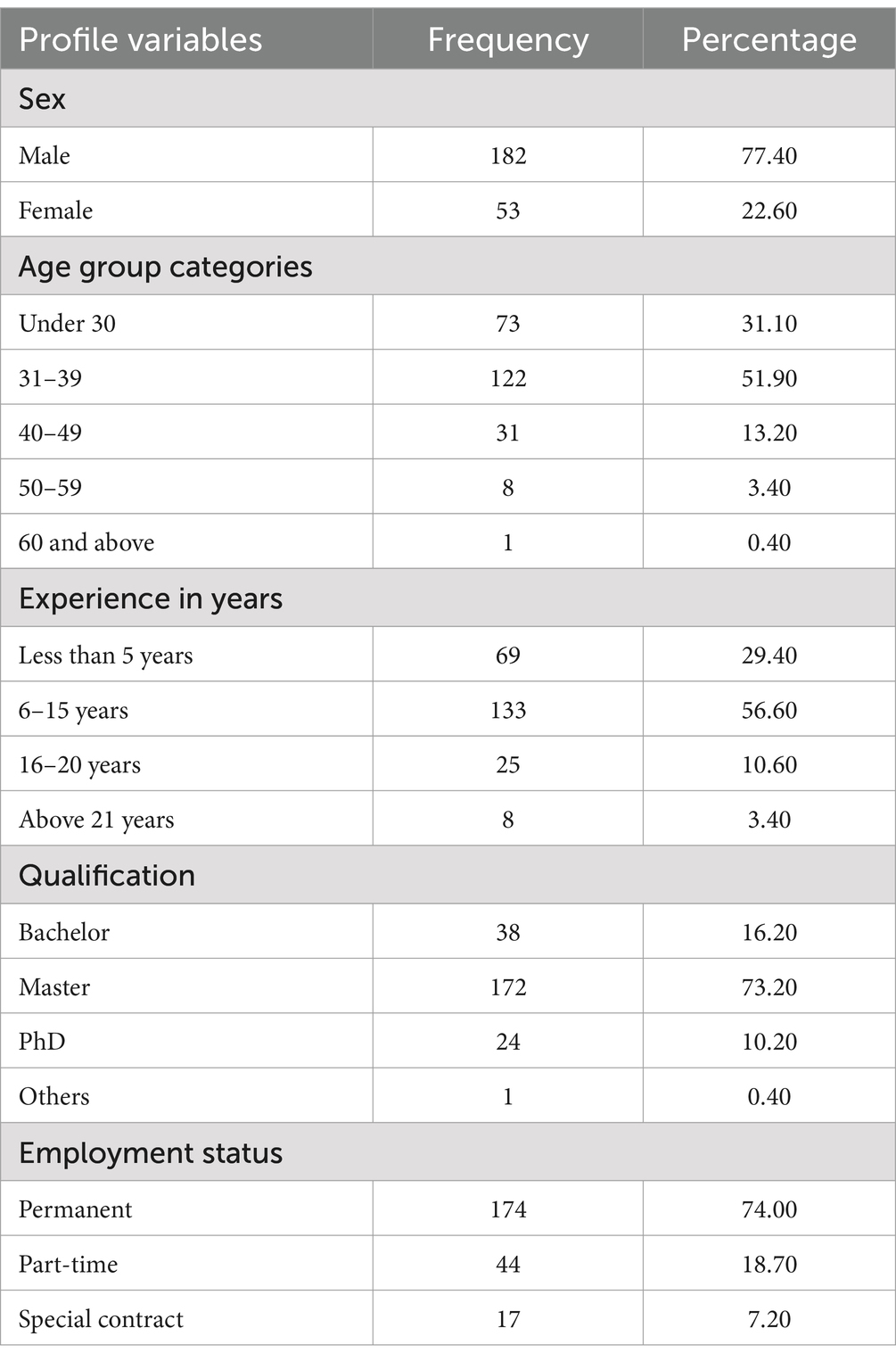

The investigation employed structured questionnaires utilizing a five-point Likert scale to survey 236 academic staff at private universities in Mogadishu. Of the 500 questionnaires disseminated, 235 were returned, with a response rate of 47% among survey participants. The final analysis incorporated data from all 235 respondents as the examination revealed no outliers or missing cases in the dataset. The study included 235 participants, primarily male (77.4%) and female (22.6%). Most study participants were aged 31–39 years (51.9%). The second-largest age group was those under 30 (31.1%) and those over 50 (3.8%). Regarding professional experience, 56.6% had 6–15 years, while 29.4% had less than 5 years. Regarding education, 73.2% of the study participants had master’s degrees, 16.2% had bachelor’s degrees, and 10.2% had PhDs. Regarding employment status, 74.0% were full-time, 18.7% part-time, and 7.2% had specialized contracts.

The background of the respondents

Table 1 presents detailed profiles of the study respondents.

Instruments

This study employed instruments from previous research owing to their established reliability and validity. The perceived organizational politics (POP) construct was measured using six items derived from research conducted by Kacmar and Ferris (1991). These items comprised all dimensions of the POP construct. A sample item includes: “It is sometimes easier to remain quiet than fight the system in this university” and “People in this university attempt to build themselves up by tearing others down.” Academic turnover intentions were gaged using six questions from a study conducted by Rawashdeh et al. (2022). The items included two dimensions: physical and psychological withdrawal. Examples of the items include: “There is a lack of career development opportunities at this university” and “There is an insufficient salary and benefits at this university.” The professional commitment (PCO) construct was measured using six items from previous research (Malhotra et al., 2007). The items included all dimensions of commitment. Examples of statements include: “I would be happy to spend the rest of my career at this university” and “It would be very hard for me to leave my university right now, even if I wanted to.” Islamic work ethic (IWE) was measured using five items derived from research conducted by Omri et al. (2017). Examples of items include: “I spend most of my time carrying out my duties” and “When our university has a problem, I meet with executives to discuss all possible solutions.” Responses to all items were collected using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” This study includes 23 items.

Data analysis and findings

Following the guidelines outlined by Hair et al. (2022), we used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the proposed study hypotheses. Initially, we evaluated common method bias (CMB) before assessing the measurement and structural models. We selected PLS-SEM because it can forecast intricate models, accommodate small sample sizes, and offer flexibility regarding the assumptions of normality (Hair et al., 2022).

Before evaluating the study’s psychometric features, we assessed the potential for CMB using SmartPLS 4.1.0.8 and SPSS. We used two statistical procedures to reduce CMB, adhering to the recommendations proposed by Podsakoff et al. (2003). First, we computed the unrotated exploratory factor analysis using SPSS 27 and a single-factor test. The results showed that CMB was not a threat, with a single factor accounting for only 21.663% of the variance, which is below the 50% threshold. We then checked for full collinearity, which showed that all latent variable variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were below the suggested level of 3.3 (Kock, 2017). The test results indicate that CMB does not significantly impact the model’s validity.

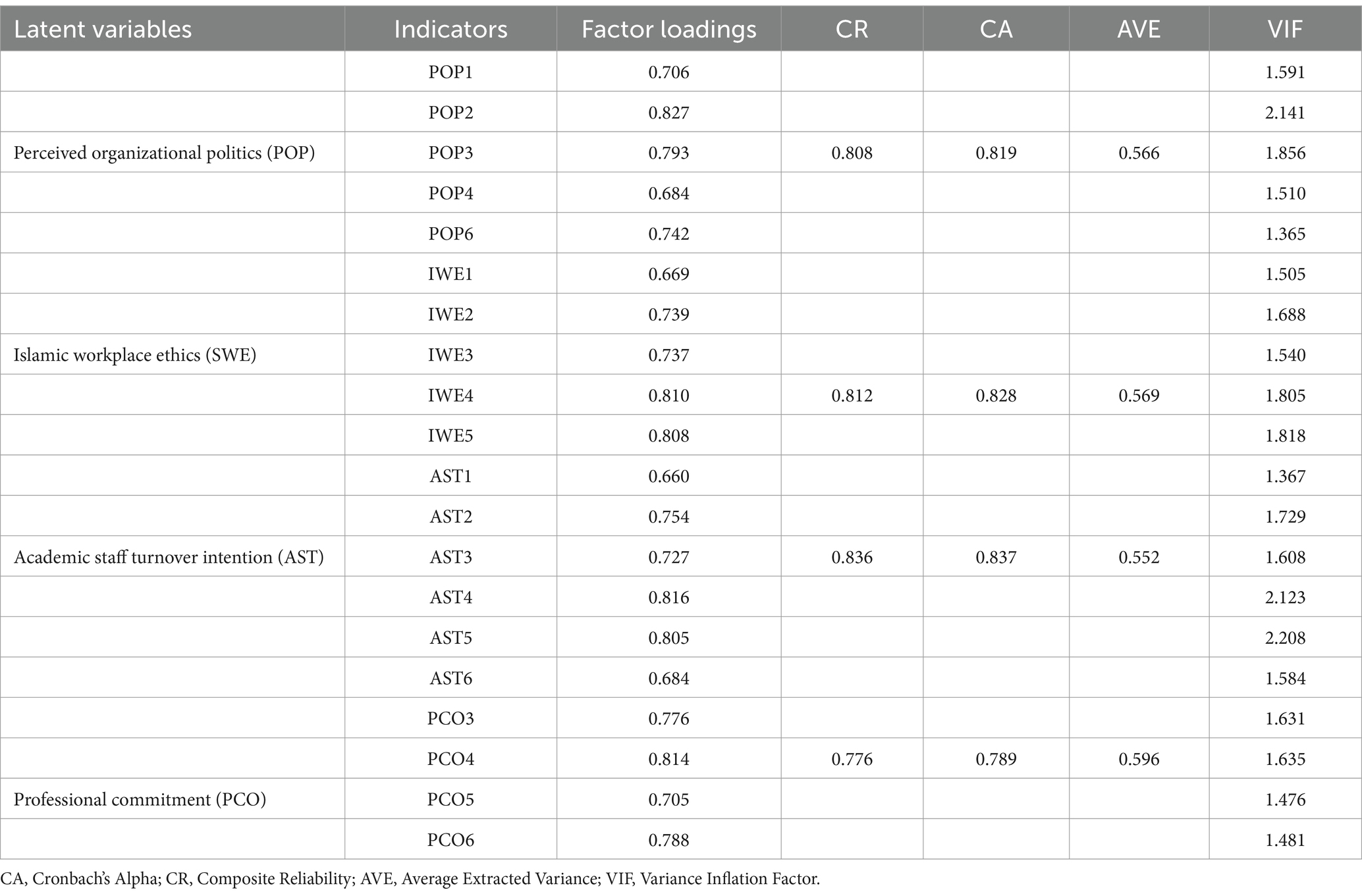

Measurement model

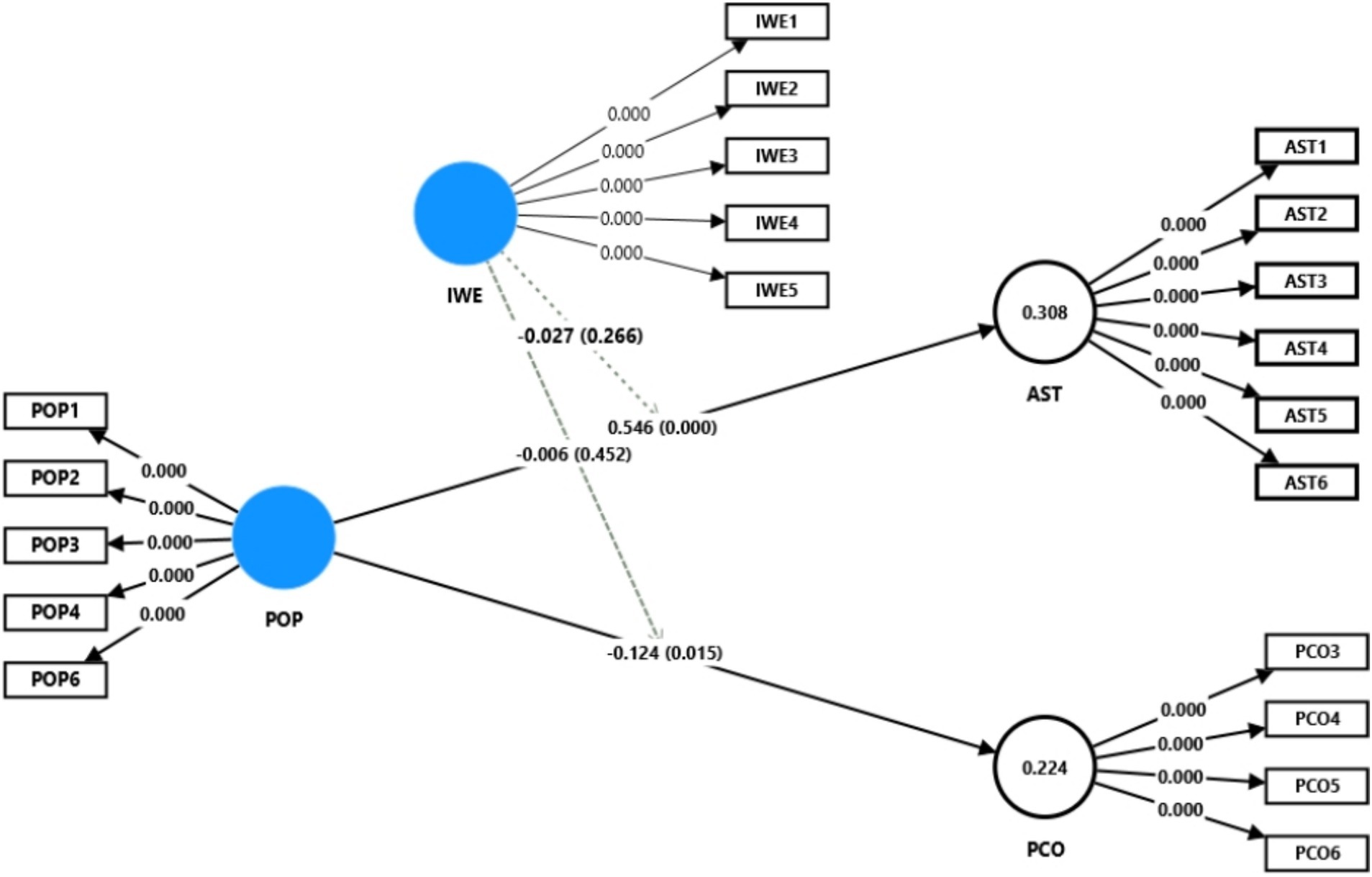

Table 2 and Figure 2 show the psychometric properties of the outer measurement model using the SmartPLSv. 4.1.0.8. First, we evaluated the outer loadings of each question in the survey to ascertain the indicator reliability. A threshold score of 0.60 was used as a cut-off criterion to assess the outer loadings of each item (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988; Chin, 1998). All study items exceeded the threshold, except for POP5, PCO1, and PCO2, which were removed because of low factor loadings (see Table 2; Figure 2). Second, we used composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (α) to assess the construct reliability. Both criteria surpassed the cut-off of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2022), confirming the model’s high internal consistency reliability (Table 2). Third, to assess the construct’s convergent validity, we employed average variance extracted (AVE), which should be higher than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2022). As Table 2 shows, all construct scores surpassed this criterion, thereby supporting the convergent validity of this study’s model.

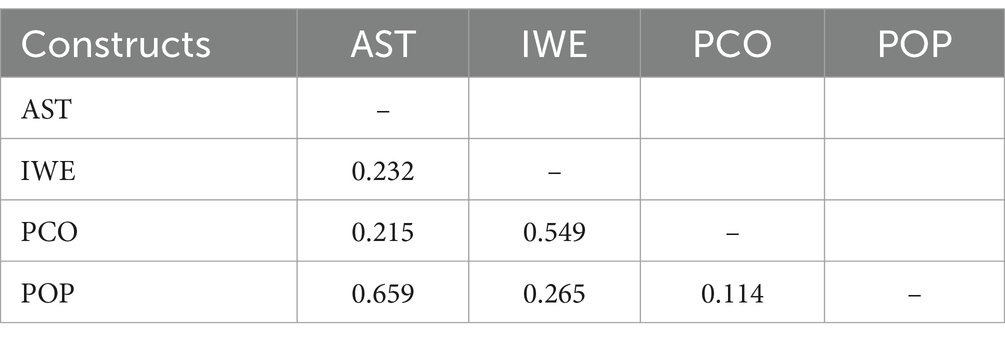

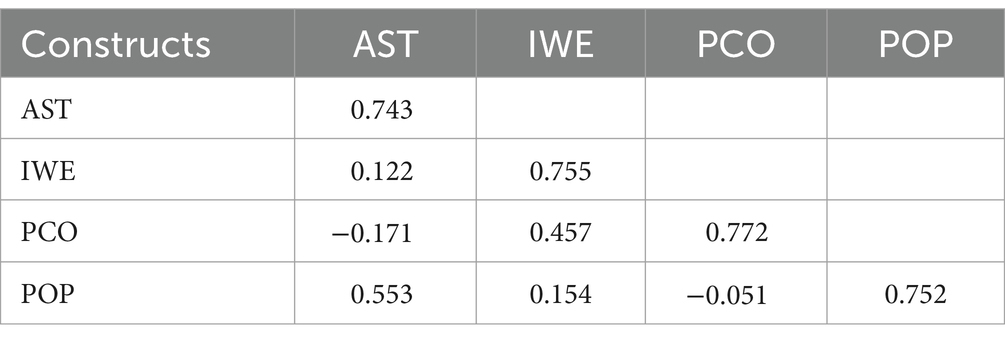

Finally, following the guidelines of Ringle et al. (2023), the study’s outer model’s discriminant validity was confirmed by meeting the minimum threshold value of 0.85 using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) (see Table 3). Table 4 displays the assessment of discriminant validity according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The diagonal elements indicate the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE), surpassing the off-diagonal correlations among constructs and affirming discriminant validity.

Evaluation of structural model

We follow the procedure described by Hair et al. (2022) to assess the structural model. First, we assessed the model’s collinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Second, we evaluated the model’s explanatory power using the coefficient of determination (R2). Third, we tested the model’s hypotheses using path coefficients with 10,000 subsamples (standardized coefficient β, t-values, and p-values). Next, to evaluate the predictive capability of the model, we computed Q2 values. Finally, the effect size (F2) was determined.

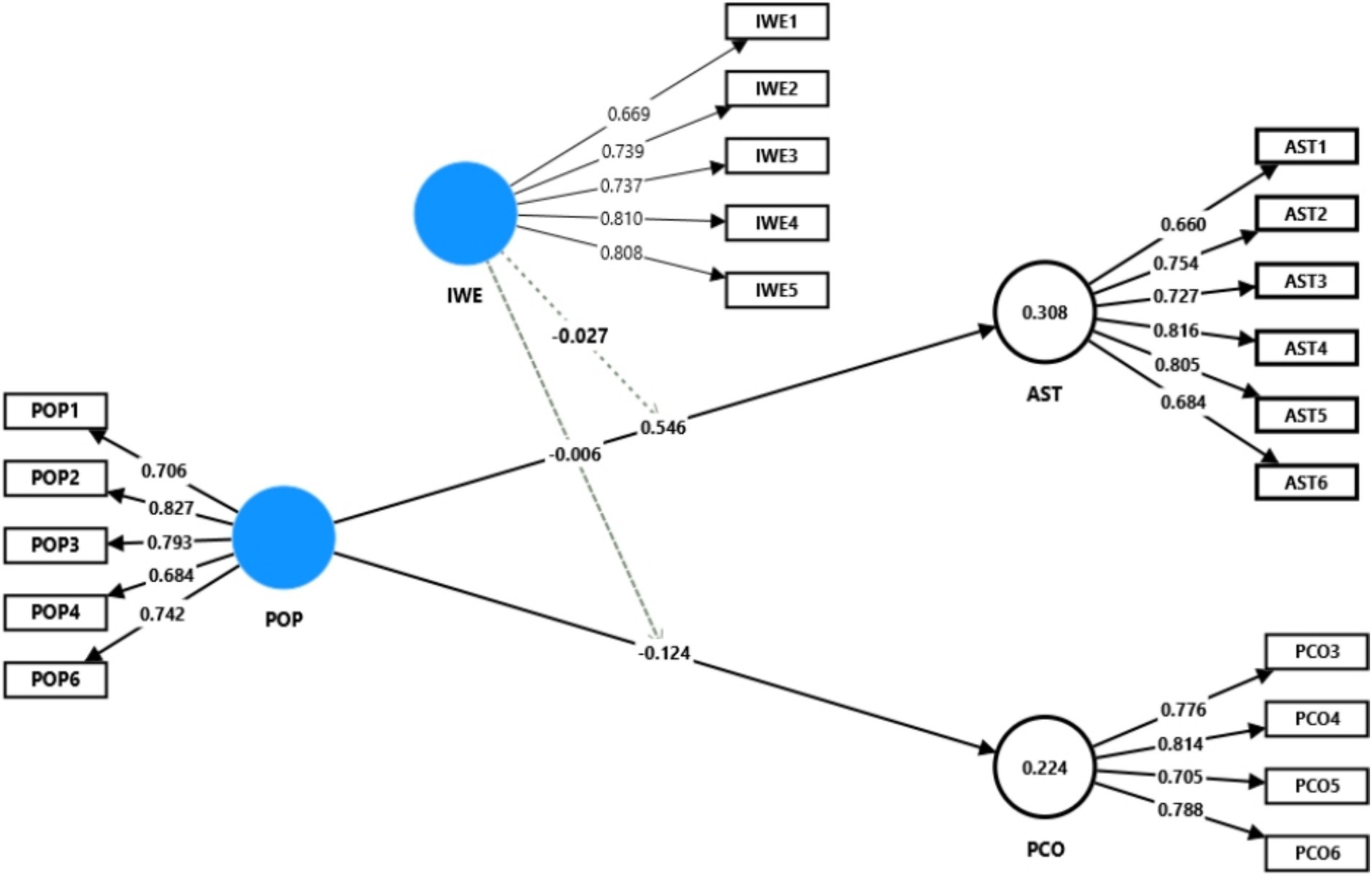

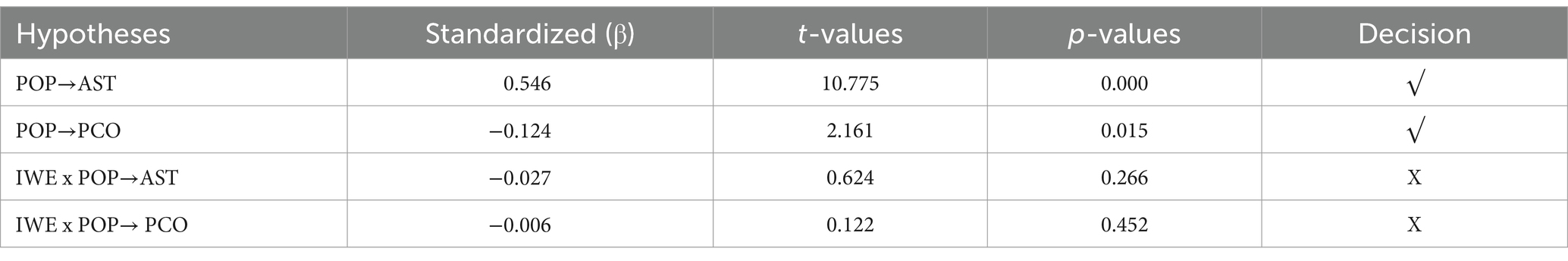

Direct hypotheses testing

The results in Table 5 and Figure 3 reveal that the effect of perceived organizational politics (POP) on academic staff turnover (AST) was significant and positive (β = 0.546, t = 10.775, p < 0.001). Hence, H1 is substantiated empirically. Similarly, the direct effect of POP on professional commitment (PCO) was significant and negative (β = −0.124, t = 2.161, p = 0.015). Thus, H2 is supported empirically.

Testing the moderation effects

The results in Table 5 depict the moderating role of IWE on the association between POP and AST, which was positive but insignificant (β = −0.027, t = 0.624, p = 0.266). Hence, H3 was considered unacceptable. Furthermore, the moderating effect of Islamic workplace ethics on the association between perceived organizational politics (POP) and professional commitment was also negative but insignificant (β = −0.006, t = 0.122, p = 0.452). Thus, H4 was considered unacceptable.

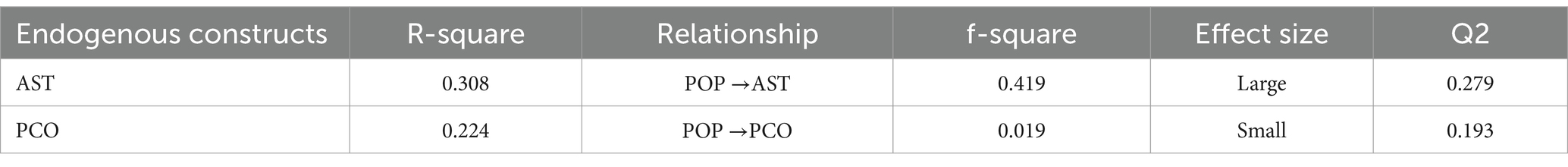

The R2 scores for the dependent variables of the study model showed that perceived organizational politics and Islamic workplace ethics accounted for 30.8% of the variation in academic staff turnover and 22.4% of the change in professional commitment (Table 5). The R2 value was satisfactory in the present study. Moreover, Table 5 indicates that the Q2 scores for the study’s dependent constructs, academic staff turnover (0.279), and professional commitment (0.193), exceed zero (0). Thus, the study model demonstrated a high predictive power. Finally, we computed the effect size of the study model following Cohen’s (1988) guidelines. The results showed that POP had a large effect size on PCO (see Table 6).

Discussion

This study examines the influence of perceived organizational politics (POP) on academic staff turnover intention (AST) and professional commitment (PCO) within private higher education institutions in Mogadishu, Somalia, while exploring the moderating role of Islamic work ethics (IWE). Drawing on social exchange and Conservation of Resources theories, the findings reveal that perceived organizational politics significantly increases academic staff turnover intention, consistent with prior research (Haleem et al., 2023; Asrar-ul-Haq et al., 2019; Mishra et al., 2016). This implies that academic staff exposed to favoritism, discrimination, or unclear benefits are more likely to consider leaving, which disrupts teaching and research activities, ultimately undermining institutional stability. Similarly, perceived organizational politics negatively impacts professional commitment, aligning with studies by Lee (2024) and Khan et al. (2017), as politically charged environments erode staff commitment. These results underscore the need for university leaders to foster inclusive environments, ensure merit-based promotions, and promote transparency in decision-making to mitigate the adverse effects of perceived organizational politics.

Contrary to our expectations, IWE did not significantly moderate the relationship between perceived organizational politics and academic staff turnover intention, diverging from Rawwas et al. (2018), who found that IWE significantly reduced turnover intentions. This suggests that while IWE may help staff endure workplace politics, it alone is insufficient to curb turnover intentions in Somalia’s post-conflict context, where weak governance and institutional uncertainty prevail. Past studies have highlighted the role of governance in mitigating organizational politics, emphasizing that institutional challenges, such as those observed in Somalia, can limit the effectiveness of ethical frameworks like IWE (Suleman et al., 2024). Similarly, IWE did not significantly moderate the perceived organizational politics and professional commitment relationship, contradicting Khan et al. (2019), who highlighted IWE’s role in fostering resilience. These discrepancies may stem from contextual differences, such as the limited institutionalization of ethical frameworks in Somalia or methodological variations in measuring the IWE scale. Future research should employ longitudinal and qualitative approaches to explore how contextual factors influence IWE’s moderating role in politically charged environments.

The broader implications of these findings suggest that while IWE is a valuable ethical framework, its effectiveness in mitigating the negative effects of POP may depend on institutional and cultural contexts. Prior research underscores the importance of ethical frameworks in shaping decision-making and fostering institutional stability (Sohail et al., 2024a). In settings like Somalia, where governance structures are weak and organizational uncertainty is high, structural reforms—such as transparent governance and equitable policies—are critical to complement ethical frameworks like IWE. Universities must prioritize these reforms to create stable, supportive academic environments that enhance staff retention and commitment. In conclusion, this study highlights the significant impact of perceived organizational politics on academic staff turnover intention and professional commitment in Somali universities, emphasizing the need for institutional interventions to reduce workplace politics. While IWE’s moderating role was insignificant, its potential to foster ethical resilience warrants further investigation. These findings contribute to the literature by contextualizing the role of IWE in post-conflict settings and underscore the importance of combining ethical frameworks with structural reforms to address organizational challenges effectively.

Theoretical and practical implication

Theoretical implications

This study explores the relationship between POP, AST, and PCO in a private higher education institution in Mogadishu, Somalia, and the moderating effect of Islamic work ethics on these relationships, drawing on social exchange theory (SET). Previous studies suggest that IWE can minimize the negative impact of POP on both professional commitment and turnover intention among employees by promoting ethical behavior and principles (Khan et al., 2019; Rawwas et al., 2018). The study findings reveal that varying organizational contexts and cultural variables could affect the effectiveness of IWE in moderating this relationship. The results also show that academic staff members are more likely to experience a decrease in institutional commitment and foster employee turnover intention if they believe that their university is politically charged and characterized by bias and self-serving actions. Furthermore, the results of the current study emphasize the value of the moderating role of IWE, such as justice and accountability, which can moderate the harmful influences of POP on employee outcomes. The results of this study imply that, even when political activity affects employee commitment and retention, universities can boost their commitment by promoting an ethical work environment.

Practical implications

The findings of this study provide valuable insights for tertiary education institutions to address the reduced commitment and increased turnover intentions of academic staff resulting from perceived organizational politics. To mitigate these challenges, leaders of private universities must ensure that academic staff receive objective, merit-based evaluations and rewards that remain unaffected by political influence, favoritism, and nepotism. Research suggests that fair rewards and justice are critical determinants of employees’ commitment to their institutions (Dunger, 2023). However, employees’ efforts and achievements may be inequitably assessed in politically charged environments, leading to inappropriate rewards influenced by political motives. This, in turn, can erode morale and diminish commitment to the institution (Lee, 2024).

A key strategy for addressing these issues is the integration of Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) into institutional policies and decision-making processes. Leaders in higher education can adopt Islamic Work Ethics (IWE) as a guiding framework for promotion, professional development, and equitable opportunities for academic staff, particularly in politically influenced institutional environments. Prior research has highlighted the role of IWE in minimizing the negative effects of organizational politics on employees (Khan et al., 2019; Rawwas et al., 2018). Given that organizational politics often disrupt workplace cohesion and trust, unethical decision-making by leadership can further exacerbate these challenges. To counteract this, university leaders can integrate IWE into selection criteria for hiring and provide structured training programs to foster ethical workplace behaviors. Earlier research supports the critical role of ethical leadership in mitigating the adverse effects of organizational politics and enhancing institutional performance (Abdi et al., 2024). By embedding IWE into institutional practices, universities can promote fairness, transparency, and trust, ultimately creating a more cohesive and productive academic environment. Furthermore, Social Exchange Theory (SET) suggests that employees reciprocate perceived organizational support with increased commitment and reduced turnover intentions. However, this commitment weakens when employees experience political interference, favoritism, or unjust treatment. To address this issue, university leaders and administrators must foster a fair, transparent, and trust-based environment in which all staff members feel respected and valued. By embedding ethical principles such as fairness, integrity, and respect for others, leaders can enhance organizational justice, reduce political deception, and increase employee engagement. An integrated system that aligns ethical norms with institutional policies can help mitigate the effects of organizational politics, promote staff commitment, and reduce turnover.

Administrators of private universities in Somalia should prioritize governance reforms that enhance transparency and accountability to mitigate the adverse effects of organizational politics. This can be achieved through well-defined policies, independent oversight bodies, and participatory decision-making processes. Earlier studies have emphasized the importance of long-term governance reforms in promoting transparency and institutional stability (Nosheen et al., 2024). Furthermore, leadership development programs should incorporate training in ethical decision-making, conflict resolution, and political acumen to cultivate a meritocratic institutional culture. Earlier studies have highlighted the effectiveness of leadership training in reducing favoritism and improving governance (Sohail et al., 2024b). Moreover, human resource policies must emphasize fair recruitment practices, standardized performance evaluations, and impartial promotion criteria to reduce favoritism and ensure procedural justice. Establishing structured grievance redressal mechanisms, such as anonymous reporting systems and regular HR audits, can further reinforce institutional integrity. Past studies support merit-based recruitment, performance evaluations, and grievance mechanisms as effective strategies to reduce organizational politics and improve faculty retention (Yasmin et al., 2024). These strategic measures will foster a transparent and equitable academic environment, ultimately enhancing faculty commitment and reducing turnover intentions.

Limitations and future research suggestions

While this study offers valuable insights into the impact of perceived organizational politics on turnover intention and professional commitment as well as the moderating role of Islamic work ethics, it is not without limitations that present opportunities for future research. The use of an online cross-sectional design that relies on self-reported data restricts the ability to establish causal inferences and limits the capacity to examine the long-term effects of perceived organizational politics and Islamic work ethics on academic staff outcomes. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to better capture the temporal evolution of these dynamics and their sustained impacts over time.

Moreover, this study focused exclusively on private universities in Mogadishu, Somalia, which may limit the generalizability of its findings to other regions of the country or public universities within the same context. Future research should expand the scope to include diverse organizational settings, such as public versus private institutions or universities in different geographical areas, to evaluate the broader applicability of these findings beyond the specific context examined in this study.

Furthermore, exploring additional moderating constructs such as ethical leadership, perceived organizational support, and cultural values could offer more nuanced insights into how organizations, particularly universities, might mitigate the adverse effects of perceived organizational politics. Investigating these factors could help identify mechanisms to foster a more supportive and equitable work environment, ultimately enhancing employee commitment and reducing turnover intention.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Committee of Simad University, Mogadishu, Somalia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

A-NA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Investigation. MF: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Software, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors gratefully acknowledge SIMAD University for providing financial support for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdi, A. N. M., Hashi, M. B., and Latif, K. F. (2024). Ethical leadership and public sector performance: mediating role of corporate social responsibility and organizational politics and moderator of social capital. Cogent Bus. Manag. 11. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2024.2386722

Ahmed, M., Hidayat, I., and Ur Rehman, F. (2015). Determinants of employee’s turnover intention: a case study of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 9, 615–623. doi: 10.5897/AJBM2015.7731

Ali, A. J., and Al-Owaihan, A. (2008). Islamic work ethic: a critical review. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 15, 5–19. doi: 10.1108/13527600810848791

Asad, M., Muhammad, R., Rasheed, N., Chethiyar, S. D., and Ali, A. (2020). Unveiling antecedents of organizational politics: an exploratory study on science and technology universities of Pakistan. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 29, 2057–2066.

Asrar-ul-Haq, M., Ali, H. Y., Anwar, S., Iqbal, A., Iqbal, M. B., Suleman, N., et al. (2019). Impact of organizational politics on employee work outcomes in higher education institutions of Pakistan. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 8, 185–200. doi: 10.1108/sajbs-07-2018-0086

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/bf02723327

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., and Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 97, 117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Caniago, S. A., and Mustoko, D. (2020). The effect of Islamic work ethics on organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions of Islamic microfinance in Pekalongan. Int. J. Islamic Bus. Econ. 4, 30–39. doi: 10.28918/ijibec.v4i1.1571

Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: issues and opinions on structural equation modeling. MIS Q., 22, vii–xvi. Available online at: http://www.jstor.com/stable/249674.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

De Clercq, D., Shu, C., and Gu, M. (2023). Overcoming organizational politics with tenacity and passion for work: benefits for helping behaviors. Pers. Rev. 52, 1–25. doi: 10.1108/pr-09-2020-0699

Donald, M. F., Bertha, L., and Lucia, M. E. (2016). Perceived organizational politics influences on organizational commitment among supporting staff members at a selected higher education institution. In: 2016 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings, Vienna, Austria. WEI International Academic Conference, pp. 29–37.

Dunger, S. (2023). Culture meets commitment: how organizational culture influences affective commitment. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 26, 41–60. doi: 10.1108/ijotb-09-2022-0173

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., and Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 500–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Ekawarna, F. (2019). The effect of perception of organizational politics and work-family conflict on job stress and intention to quit: the case of adjunct faculty members in one state university. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 8, 322–333. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Effect-Of-Perception-Of-Organizational-Politics-Ekawarna-Kohar/7629b9efe9ba5587d36eeec0f9cb2be7f828d01f

Ekpenyong, L. E., and Ojeaga, I. J. (2022). Influence of organizational politics on resource allocation in Nigerian universities. Int. J. Educ. Res. 10, 12–23. Available at: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijer/article/view/220673

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Haleem, M. S., Akhtar, S., Hamid, M. T., and Iqbal, M. N. (2023). The role of perceived organizational politics in organizational commitment and turnover intentions among private sector teachers. J. Policy Res. 9, 241–247. doi: 10.61506/02.00146

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Javeda, T., and Ishakb, S. (2019). Impact of perception of organizational politics (POP) on counterproductive work behaviour (CWB) and moderating role of Islamic work ethics among higher education sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Innovat. Creat. Change 8, 120–137. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Impact-of-Perception-of-Organizational-Politics-on-Javeda-Ishakb/6cc4b33c60d5857d3b8d51be3ef5b13f21c1c344

Kacmar, K. M., and Baron, R. A. (1999). “Organizational politics: the state of the field, links to related processes, and an agenda for future research” in Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, vol. 17 (Greenwich), 1–39.

Karim, D. N., Majid, A. H. A., Omar, K., and Aburumman, O. J. (2021). The mediating effect of interpersonal distrust on the relationship between perceived organizational politics and workplace ostracism in higher education institutions. Heliyon 7:e07280. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07280

Kathula, D. N. (2024). Political staff promotions, vice Chancellor's leadership style and performance of private universities in Kenya. J. Educ. 7, 88–113. doi: 10.53819/81018102t4257

Kebede, A. G., and Fikire, A. H. (2022). Demographic and job satisfaction variables influencing academic staffs’ turnover intention in Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 9:2105038. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2022.2105038

Khairy, H. A., Mahmoud, R. H., Saeed, A. A. A., and Hussien, I. M. (2023). The moderating role of ethical leadership in the relationship between organizational politics and workplace envy in hotels. J. Fac. Tourism Hotels Univ. Sadat City 7, 1–20. doi: 10.21608/mfth.2023.318055

Khan, H. S. u. d., Zhiqiang, M., Abubakari Sadick, M., and Ibn Musah, A.-A. (2018). Investigating the Role of Psychological Contract Breach, Political Skill and Work Ethic on Perceived Politics and Job Attitudes Relationships: A Case of Higher Education in Pakistan. Sustainability, 10:4737. doi: 10.3390/su10124737

Khan, N. A., Khan, A. N., and Gul, S. (2019). Relationship between perception of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior: Testing a moderated mediation model. Asian Bus. Manag. 18, 122–141. doi: 10.1057/s41291-018-00057-9

Khan, A., and Hussain, N. (2016). The analysis of the perception of organizational politics among university faculty. Pakistan Business Review, 18, 451–467. doi: 10.22555/pbr.v18i2.826

Khan, H. S. U. D., Zhiqiang, M., Sarpong, P. B., and Naz, S. (2017). Perceived organisational politics and job attitudes: a structural equation analysis of higher education faculty of Pakistani universities. Can. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 5, 1–12. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Perceived-Organisational-Politics-and-Job-A-of-of-Khan-Ma/e1a24fd119060ddb41d37b141aad2ecda94edea9

Kacmar, K. M., and Ferris, G. R. (1991). Perceptions of organizational politics scale (POPS): Development and construct validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51, 193–205. doi: 10.1177/0013164491511019

Kock, N. (2017). “Common method bias: a full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM” in Partial least squares path modeling. eds. H. Latan and R. Noonan (Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland: Springer), 245–257.

Lata, L., Mohamed Zainal, S. R., Jan, G., and Memon, U. (2021). The nexus of physical, cognitive, and emotional engagement with academic staff turnover intention: the moderating role of organizational politics. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 40, 36–49. doi: 10.1002/joe.22077

Lee, J. (2024). Perceptions of organizational politics and organizational commitment: role of personal motive and ability. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 27, 139–160. doi: 10.1108/ijotb-05-2023-0107

Mahmoudi, F., and Bagheri Majd, R. (2021). The effect of lean culture on the reduction of academic corruption by the mediating role of positive organizational politics in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 80:102319. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102319

Malhotra, N., Budhwar, P., and Prowse, P. (2007). Linking rewards to commitment: an empirical investigation of four UK call centers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 18, 2095–2128. doi: 10.1080/09585190701695267

Malik, O. F., Shahzad, A., Raziq, M. M., Khan, M. M., Yusaf, S., and Khan, A. (2019). Perceptions of organizational politics, knowledge hiding, and employee creativity: the moderating role of professional commitment. Personal. Individ. Differ. 142, 232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.005

Mishra, P., Sharma, S. K., and Swami, S. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of organizational politics: a select study of a central university. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 13, 334–351. doi: 10.1108/jamr-05-2015-0033

MoECHE. (2022). Education sector analysis: Federal government of Somalia: Assessing opportunities for rebuilding the country through education. IIEP-UNESCO. Available online at: https://www.iiep.unesco.org/en/publication/education-sector-analysisfederal-government-somalia-assessing-opportunities-rebuilding (Accessed November, 2024).

Mohamed, M. A., Tutar, H., Eidle, F. A., Mohamud, I. H., and Farah, M. A. (2024). The influence of nepotistic education leaders on employee turnover intentions: academic performance plays a mediator variable at private universities in Mogadishu. doi: 10.33844/ijol.2024.60432

Mosquera, P., Tigre, F. B., and Alegre, M. (2024). Overcoming organizational politics and unlocking meaningful work through ethical leadership. Int. J. Ethics Syst. doi: 10.1108/ijoes-04-2024-0108

Nauman, S., Basit, A. A., and Imam, H. (2023). Examining the influence of Islamic work ethics, organizational politics, and supervisor-initiated workplace incivility on employee deviant behaviors. Ethics Behav. 35, 55–72. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2023.2275200

Nosheen, M., Akbar, A., Sohail, M., Iqbal, J., Hedvicakova, M., Ahmad, S., et al. (2024). From fossil to future: the transformative role of renewable energy in shaping economic landscapes. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 14, 606–615. doi: 10.32479/ijeep.16006

Omri, W., Becuwe, A., and Randerson, K. (2017). Unravelling the link between creativity and individual entrepreneurial behaviour: the moderating role of Islamic work ethics. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 30:567. doi: 10.1504/ijesb.2017.082916

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical literature review and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rawashdeh, A. M., Elayan, M. B., Shamout, M. D., and Hamouche, S. (2022). Human resource development and turnover intention: organizational commitment's role as a mediating variable. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 31, 469–484. doi: 10.1108/ejmbe-12-2021-0343

Rawwas, M. Y., Javed, B., and Iqbal, M. N. (2018). Perception of politics and job outcomes: moderating role of Islamic work ethic. Pers. Rev. 47, 74–94. doi: 10.1108/PR-03-2016-0068

Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Sinkovics, N., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2023). A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modeling in data articles. Data Brief 48:109074. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2023.109074

Sohail, M., Khan, S., Akbar, A., Hedvicakova, M., and Haider, S. A. (2024a). Sustainable development through green finance—an exploratory investigation in the financial industry of France. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 8:4668. doi: 10.24294/jipd.v8i7.4668

Sohail, M., Khan, S., Akbar, A., and Svobodova, L. (2024b). Empowering sustainable development: the crucial nexus of green fintech and green finance in Luxembourg’s banking sector. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 8:4979. doi: 10.24294/jipd.v8i7.4979

Soper, D. S. (2024). A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models [software]. Available online at: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc.

Suleman, S., Nawaz, F., Sohail, M., Kayani, U., Thas Thaker, H. M., and Wing Hoh, C. C. (2024). An empirical analysis of trade market dynamics on CO2 emissions: a study of GCC economies. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 14, 114–126. doi: 10.32479/ijeep.16704

Tian, Y., Chan, T. J., Suki, N. M., and Kasim, M. A. (2023). Moderating role of perceived trust and perceived service quality on consumers’ use behavior of Alipay E-wallEt system: the perspectives of technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2023/5276406

Usmani, S. (2024). Perceptions of politics and knowledge sharing: Moderating role of Islamic work ethic in the Islamic banking industry of Pakistan. Heliyon 10:e37032. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37032

Utami, A. F., Bangun, Y. R., and Lantu, D. C. (2014). Understanding the role of emotional intelligence and trust to the relationship between organizational politics and organizational commitment. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 115, 378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.444

Vigoda-Gadot, E., and Talmud, I. (2010). Organizational politics and job outcomes: the moderating effect of trust and social support. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 40, 2829–2861. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00683.x

Yasmin, F., Haider, S. A., Sohail, M., Tehseen, S., Poulova, P., and Akbar, A. (2024). How does knowledge based human resource management practices enhance organizational performance? The mediating role of knowledge workers productivity. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 8:9383. doi: 10.24294/jipd9383

Yousef, D. A. (2001). Islamic work ethic: a moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Pers. Rev. 30, 152–169. doi: 10.1108/00483480110380325

Keywords: organizational politics, turnover intention, commitment, Islamic work ethics, higher education institutions, Somalia

Citation: Abdi AM, Mohamed MA and Farah MA (2025) Perceived organizational politics, turnover intention, and commitment in higher education institutions: the contingent role of Islamic work ethics. Front. Educ. 10:1544269. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1544269

Edited by:

Hira Salah ud din Khan, Jiangsu University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nicoleta Dospinescu, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, RomaniaMuhmmmad Salman Chughtai, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Mariam Sohail, De Montfort University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Abdi, Mohamed and Farah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmed-Nor Mohamed Abdi, YWhtZWRub3IyMDEyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Ahmed-Nor Mohamed Abdi

Ahmed-Nor Mohamed Abdi Mohamud Ahmed Mohamed

Mohamud Ahmed Mohamed Mohamed Ali Farah

Mohamed Ali Farah