- 1Media-Based Knowledge Construction – Research Methods in Psychology, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany

- 2Learning Sciences Research Institute, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Group awareness tools are used for collecting, transforming, and presenting information about potential learning partners. Their use may be influenced by the credibility a learner assigns to the source of such information. In a 2x2x2 mixed design study (N = 152), we investigate how source type (teacher assessment/self-assessment) interacts with gender of a potential learning partner (male/female) and competence level (high/low) of a potential learning partner. In line with existing research, we found that information from external sources is perceived more credible than information from internal sources with teacher assessments being more credible compared to self-assessments. In addition, the type of source interacts with both the gender and the competence level of learning partners when judging the credibility of a source. As the acceptance of information plays a key role in group awareness, it is worth considering the identified effects in future research, especially when focusing on possible designs of such tools.

Introduction

When focusing on social learning scenarios, group awareness is a central aspect of interest. It can generally be understood as information about a group or its group members that is conscious and aware to the group members (Bodemer et al., 2018). It is known as the perception or awareness of characteristics and attributes of learning partners. In group awareness research, social and cognitive group awareness are often distinguished. Specifically, cognitive group awareness describes the perception of knowledge and content-relevant information of group members. In contrast, social group awareness is defined as the perception of collaborative behavior of group members (Janssen and Bodemer, 2013). Group awareness tools that collect, transform, and present learner-related information (Bodemer and Dehler, 2011; Ghadirian et al., 2016; Schnaubert et al., 2020) can be helpful in many ways: selecting learning partners, forming groups, monitoring or controlling learning progress, and facilitating learners’ understanding (Cai and Gu, 2019). Appropriate group formation was found to be the basic requirement for successful collaborative learning (Revelo Sánchez et al., 2021). In (online) help-seeking scenarios, presented characteristics of possible helpers can be a crucial factor in reducing barriers to help-seeking (Jay et al., 2020). In discussions or learning scenarios, group awareness information can be used to find the ideal learning partner. Research showed that learners very often choose socially similar (e.g., age) partners; especially in traditional environments where social interaction has already happened, and learners know each other (Moreno et al., 2012). In online environments, however, where learners can freely choose their partners, they can apply more opportunistic strategies choosing partners according to their interests and needs (Siqin et al., 2015) which can be aspects like, e.g., knowledge level, problem-solving skills, et cetera.

In general, group awareness information in tools covers social, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions (Tang et al., 2025). While group awareness tools often use interactions between group members (Ghadirian et al., 2016), this is difficult in computer-supported settings where group members often lack direct cues (Kwon, 2019). Researchers of group awareness tools use different sources of group awareness information in their studies: Tang et al. (2025) used social networks that presented discussion activities, engagement, and participation behavior of group members in a discussion, Dehler et al. (2011) asked participants to self-assess their knowledge levels, Jermann and Dillenbourg (2008) analyzed students’ number of words and manipulations to present their collaborative problem-solving processes, and Li et al. (2021) collected group awareness information by analyzing used words, number of postings and interaction diagrams of interaction patterns of participants. These exemplary studies indicate the complexity and variety of possible sources of group awareness information in tools. In a systematic meta-analysis, Zheng et al. (2025) examined the impacts of these tools on learning finding the data source of group awareness information to be a moderator variable for the effect of group awareness tools. It is hence important focusing not only on the tool design itself, but also to consider the source of group awareness information and how it is evaluated by learners. The usage of the information is crucial in this context. If learners use tool information, they must estimate its value by evaluating the message and source. Janssen et al. (2011) emphasize that merely providing group awareness (GA) information is not enough to initiate meaningful change or impact. The effectiveness of GA tools depends not just on the availability of information, but on how individuals use and apply that information in decision-making processes. The authors argue that information alone does not lead to action; instead, the perceived value and relevance of the information, as well as the user’s ability to make sense of it, play crucial roles in determining its impact. Considering information integration theory (Anderson, 1971), individuals do not assess each piece of information in isolation when forming judgments or making decisions. The theory suggests that people rather use a weighted and additive approach, assigning different levels of importance to various pieces of information before combining them to an overall conclusion. According to this theory, not only the pure content of information matters, but also surrounding factors such as the source of an information, the context in which it is presented, and the consistency of such information with existing knowledge and beliefs of an individual. In this context, people seem to be more receptive to use information that is directly applicable to their current needs. Secondly, information from trusted and more credible sources is more likely to be used in this process. Lastly, people are more likely to integrate information that already aligns with what they do know and believe. Information that contradicts their current knowledge might be questioned or excluded (Anderson, 1971). This emphasizes the importance not only of information but also of the source and surrounding factors as these might as well be included in the judgment process (e.g., Gaj, 2016; Noble and Shanteau, 1999).

Following this, observing decisions based on judgments learners make regarding learning partners (e.g., preference to work with a specific partner) based on group awareness information provided delivers insights on how they utilize and weight this information in their decision process.

Freund et al. (2025) studied the perception and usage of information in group awareness tools depending on its particular source. The study aimed to investigate how individuals weight information from different sources (self-assessments, teacher assessments, and knowledge tests) when making decisions about learning partners in a group setting. Participants acted as seminar leaders tasked with selecting a suitable group member for an existing learning group based on anonymized profiles. These profiles included cognitive group awareness information about competence levels and the source of assessment (self-assessment, knowledge test, or teacher assessment). The results show that information from external sources (e.g., teacher assessments or knowledge tests) is perceived as more credible and weighted higher than internal self-assessed information. Assuming that knowledge tests were perceived as more neutral and objective, hence weighted higher than rather subjectively perceived teacher assessments, the study also showed that no significant difference could be identified between the external sources. Both external sources—personal (teacher assessment) and non-personal (knowledge test) were weighted similarly in Freund et al. (2025). Our research extends this experimental approach by adding gender (of the source) and competence levels of potential learning partners as additional factors and focusing on potential interaction effects of those.

Despite the increasing use of group awareness tools in collaborative learning environments, only little is known about how learners evaluate and use information from different sources when selecting learning partners. Previous research has shown that external sources, such as teacher assessments and knowledge tests, seem to be perceived as more credible compared to internal sources like self-assessments (Dunning et al., 2004). While self-assessments are often promoted for their potential to foster metacognitive reflection and learner autonomy (Boud, 1995; Schnaubert and Bodemer, 2019), they are also criticized for their limited accuracy and tendency to be biased (Keplová, 2022; Kruger and Dunning, 1999). Moreover, information integration theory (Anderson, 1971) suggests that individuals combine multiple cues when making decisions. However, empirical evidence which cues learners might combine and how they weight these cues is limited. Hence, characteristics, such as gender and competence level of a potential learning partner as potential cues, may influence how information is perceived and used.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating how the gender and competence level of potential learning partners affect the perceived source credibility and weighting of group awareness information from different sources in a learning context. We enhanced the study from Freund et al. (2025) by including additional characteristics such as gender and competence. The goal is to better understand how learners use such information in learning partner selection and to inform the design of more effective and trustworthy group awareness tools. Learners estimate the value of information in group awareness tools by evaluating the message and source. This may affect how the information provided by the source is perceived, resulting in a certain and measurable degree of information weighting. This makes information weighting, source credibility, and message credibility essential concepts for research on group awareness tools. While there is a large amount of research on source credibility, the evaluation of sources of group awareness information has not been systematically researched to our knowledge. Combining findings for different types of sources, this research examines how various sources, and their credibility are perceived and weighted in an online setting of learning partner selection. When examining information from different sources and its dependence on source-or group-related aspects, it is crucial to explicitly distinguish between the source providing the information and the potential learning partner.

Group awareness and group awareness tools

Source of group awareness information

Source credibility may be an important construct when it comes to understanding how exactly people evaluate information and its value and what aspects and dimensions they might include in their evaluation process. Source credibility is often described to include the two dimensions of trustworthiness and expertise (Hovland and Weiss, 1951). On occasion, this concept gets enhanced by a third dimension: attractiveness (Ohanian, 1990). Especially in online settings, where users might be unaware of details about the source of an information, it is important to understand how this information is perceived. Following the idea of information integration theory, the process of decision and judgment making is a complex combination of pieces of information where the interaction of information is assessed, rather than considering each piece of information individually (Anderson, 1971). As the usage of online tools might highly depend on the acceptance and reliability of the presented information in such tools, it is important to rationally decide which sources to use as input for online presented information.

Research on source credibility inherently involves trustworthiness and expertise (Hovland and Weiss, 1951). Much of the more recent research has focused on online settings, such as examining the use of consumer-generated travel blogs (Ayeh, 2015), the credibility of web pages (Fogg et al., 2001), or the influence of journalists’ credibility as web page authors (Winter and Krämer, 2014). Albright and Levy (1995) found that people prefer feedback from highly credible sources that can lead to positive feelings (Ayeh, 2015) or even increased acceptance of a message (Wolf et al., 2012), while Stone et al. (1984) found that a source with high expertise indeed leads to more accurate feedback. Sternthal et al. (1978) showed that a recipient’s initial opinion is a key determinant when evaluating the credibility of a source. These two variables (source credibility/information weighting), although closely related, are distinct concepts to be considered.

There are different ways of assessing the competence or performance of individuals where we differentiate between external and internal sources. For external sources we distinguish between external personal and external non-personal sources. Rather subjectively perceived internal self-assessments (SA) and more objectively perceived external (personal, or non-personal) assessments have been an important part of learning scenarios. Group awareness tools use different sources when collecting data and may base their information on knowledge tests (KT; e.g., Sangin et al., 2011) or self-assessments (e.g., Schnaubert and Bodemer, 2019). Internal self-assessments may promote a positive reflection on one’s own performance and create a conscientiousness for one’s own knowledge (e.g., Dunning et al., 2004), whereas external assessments are generally useful for learners (Falchikov, 1995). In educational settings, there are a lot of different scenarios with potential external feedback as, e.g., in schools, universities, learning groups, or seminars. Performance estimations can hence be externally provided by tutors, instructors or, e.g., teachers. Since self-assessments are often found to be weakly correlated with actual performance (e.g., Dunning et al., 2004), it is unclear how individuals weight information from these types of sources (internal personal vs. external personal). Quite objective cognitive tests (external non-personal) are often used as an assessment method in educational contexts (Feron et al., 2016). Teacher assessments (TA; external personal), on the other hand, are often perceived as more subjective or biased than cognitive tests but are also expected to integrate more information. With the changing role of teachers in some learning environments today (e.g., “FUSE” classrooms; Ramey and Stevens, 2020), teacher assessments are even more important compared to traditional learning environments. The “FUSE” initiative is a good example of changing environments for learners where teachers stop being pure providers of content and knowledge but become more and more facilitators for learning processes—thereby gaining an even better understanding of learner’s knowledge and learning successes. Instead of traditional environments, where teachers are the resource of information and learning, the role of teachers is in a significant change process (Ramey and Stevens, 2020). This development, however, is not only an aspect of specifically created learning environments as “FUSE” but also needs to be considered in regular learning settings where learners get more and more options to choose different resources for learning than their teachers.

In general, teacher assessments are still widely used in higher education (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006), but self-assessments (and peer assessments) are expected to gradually minimize the central role of teacher assessments (De Grez et al., 2012).

Research on source credibility and assessment types has focused on gender effects with very diverse overall findings. It is hence worth considering gender as a possible determinant, which leads us to assume an interaction between source type and gender of the learning partner especially when it comes to self-assessment profiles where the source of the assessment and the to-be-assessed-person are identical. Furthermore, research suggests that performance assessments may be perceived differently depending on the (assessed) level of competence and the accuracy of the assessment. For example, while underestimation in self-assessment is perceived as rather pleasant, overestimation is not. Thus, if high performers tend to underestimate and low performers tend to overestimate their performance (Kruger and Dunning, 1999), findings suggest that competence level might influence both the credibility of sources and the information weighting.

Research question and hypotheses

The current study aims at examining the perception of group awareness information in tools depending on its varying source. We investigate how different internal (self-assessment), or external (teacher assessment or knowledge tests) source types interact with gender of a potential learning partner (male/female) and competence level (high/low) of a potential learning partner. We combine insights on internal and external and on personal and non-personal assessments to gain insights on the various perceptions of these assessment types. Based on this, we focus our research on the comparison of these (external (non-)personal and internal (personal)) three sources of information: knowledge tests (KT), teacher assessment (TA), and self-assessments (SA). Thereby, we expect a certain ranking for the perceived weighting of these types of assessments. Thus, our hypotheses cover two relevant aspects of source evaluation and effect: perceived source credibility and weighting of information from these sources. Assuming that, firstly, external assessments are perceived as more objective, hence being weighted higher and evaluated as more credible than potentially subjective internal sources. When investigating (rather objective) external assessments, we furthermore assume a similar effect between personal and non-personal sources with non-personal sources to be potentially perceived as more credible and weighted higher. We aim at answering the question: How do competence level and gender of potential learning partners influence the information weighting and source credibility when selecting a learning partner? While replicating the main idea and adaptive approach of Freund et al. (2025), we extend existing research by looking more closely at relevant partner characteristics and interactions between information sources and said characteristics.

Information weighting and source credibility

In this study, we want to reproduce and extend research of Freund et al. (2025). Based on their findings, we expect that source credibility differs for varying sources. We assume that the perception of sources, weighting of their provided information, and the assigned credibility of a source is in a sense connected. In accordance with information integration theory, we expect participants to combine different information with different weightings in order to build an opinion. Each piece of information is thereby not treated and assessed independently but complexly interacts with all the other information. The weighting of each piece of information is hence very individually and differs from person to person depending on how credible and relevant they assess the information (and its source) to be (e.g., Anderson, 1971). Following this idea, we assume that there is a connection between source credibility and the weighting of information as information is not expected to be assessed separately. In addition, we expect a ranking order of sources with knowledge tests > teacher assessments > self-assessments for both weighting of information and source credibility. Knowledge tests are a widely and commonly used measurement of performance in educational contexts. They are assumed to be relatively objective when measuring knowledge, skills, or abilities (Feron et al., 2016). The output of a cognitive knowledge test can be expected to be identical when the input is identical, which is the reason we consider the knowledge test results in our study to be the most credible and most highly weighted source of information. Although Feron et al. (2016) even argued that teacher assessments might be even better than knowledge tests. They include more aspects into the performance estimation and typically know the person they assess over a longer period of time (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006), we expect teacher assessments to be weighted less than knowledge tests (and to be perceived less credible) than self-assessments. The least credible source in our expectation that is weighted lower than the other sources is self-assessment as it was shown to be rather biased (Chou and Zou, 2020) and subjectively perceived. Based on these considerations, our first hypothesis is H1: The source of information within group awareness tools affects their source credibility, with self-assessment being perceived as less credible than teacher assessment (internal assessments < external assessments). Consequently, we assume that, compared to knowledge tests, self-assessments will be given lower weight as it is perceived as less credible than teacher assessments resulting in our second hypothesis: H2: Learners give different weight to information from different sources when choosing a learning partner based on group awareness information. More specifically, they give less weight to information from self-assessment (internal personal assessment) than on information based on teacher assessment (external personal assessment) or knowledge tests (external non-personal assessment).

While we assume general effects based on sources of assessments, characteristics of the learning partner may also be relevant influencing factors. In particular, the perception of self-assessments may be strongly based on characteristics of the “self” but may also depend on the outcome of the assessment. It is important to see if a different source, possibly leading to a different source credibility, influences the use of information by that source as well as related decision processes. To enrich the study of Freund et al. (2025), we will take a closer look at the characteristics of the learning partner within the group awareness tools that may interact with source type in affecting credibility and information weighting.

Gender and competence level of learning partner

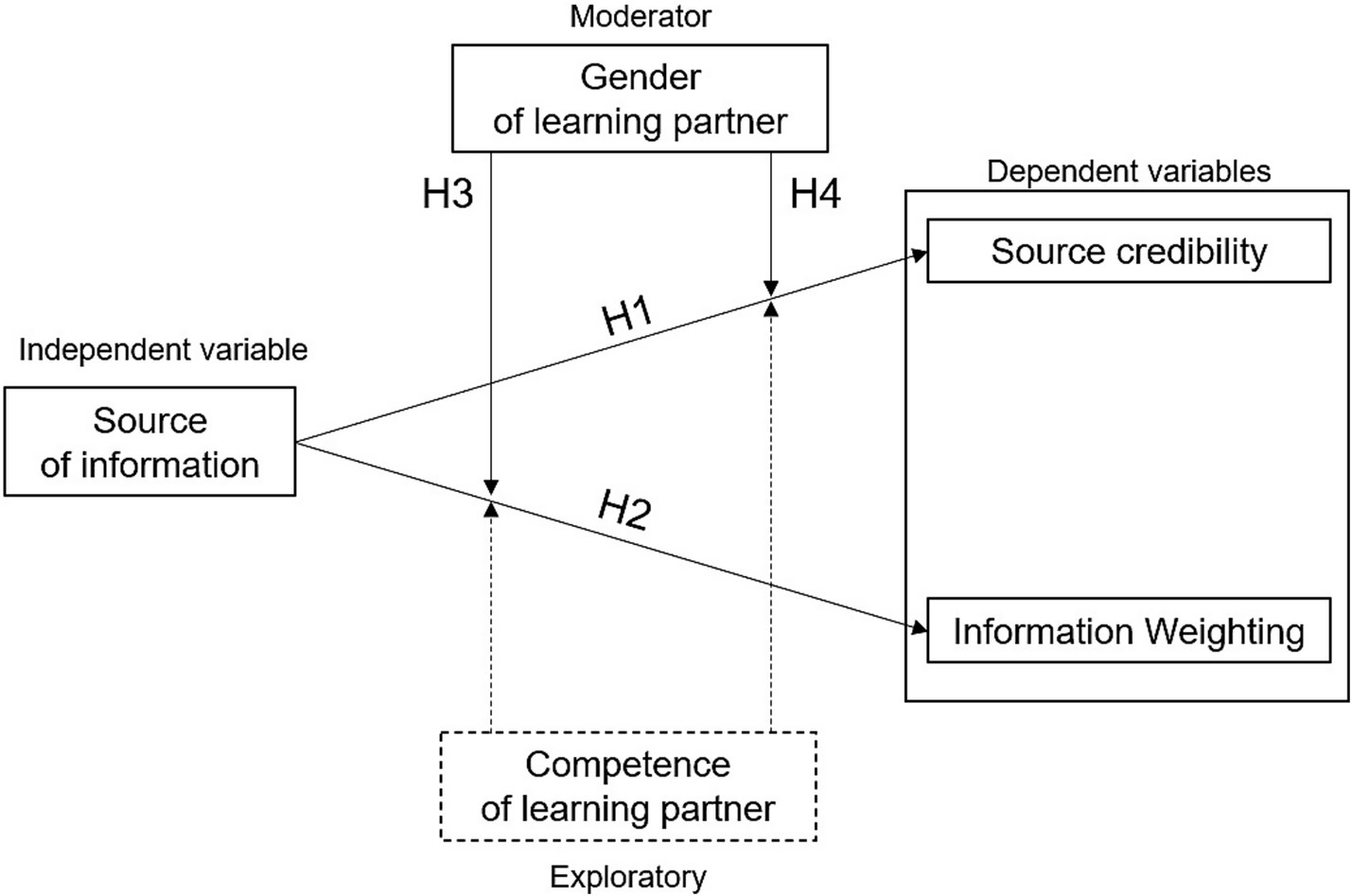

Although there is research, that found men and women to be similarly perceived and assessed when it comes to credibility (e.g., Haim and Maurus, 2023; Feron et al., 2016; Todd and Melancon, 2018), gender research in credibility research is very diverse. There is evidence for men to be perceived as more credible (e.g., Nagle et al., 2014) as well as investigations that demonstrated women to be more credible (e.g., Bigham et al., 2019). In this context, Feron et al. (2016) not only investigated differences of knowledge tests and teacher assessments (in primary school), but they also examined what factors might influence teacher assessments that can be transferred to other contexts than only children’s performances. In their study about performance estimations, they found teacher assessments to be influenced by other aspects as, e.g., gender or socio-economic factors. It is hence evident to assume that the perception of teacher assessments (as well as personal self-assessments) as a source of information in our study might also be impacted by gender or other relevant factors as, e.g., competence levels in our scenario. We hence deduce the following two hypotheses in an undirected form: H3: The source of group awareness information and the gender of the learning partner interact in affecting the information weighting when selecting learning partners. H4: The source of group awareness information and the gender of the learning partner interact in affecting perceived source credibility when selecting learning partners. Thus, we will exploratively examine whether (and how) competence levels affect the information weighting or perceived source credibility and if this interacts with source types. Figure 1 shows the formulated hypotheses as well as the involved variables.

Methods

Sample and design

A 2x2x2 mixed design online study (study ID: 2005PFBM7249) varied competence level (low/high) as a random between-subjects factor, and gender of the learning partner (male/female) and source (teacher/self-assessment) as within-subjects factors, with source credibility and information weighting as dependent variables. An a priori power analysis (performed by using the software G*Power) suggested a minimum of 128 participants for our study. As we wanted to ensure that this minimum number could be reached, we aimed at a slightly higher number of participants so that after clearing the data and removing incomplete datasets, we could still expect to have the required 128 participants. After completion of the study and clearing of the dataset, we had a sample of N = 152 participants that are now (based on a post-hoc power analysis) able to achieve an effect power of even 0.86. Of the N = 152 participants (116 females, 34 males, 2 not assigned), 78% were students and 26% were non-students (employees, retired, unemployed, et cetera). To examine whether the broader sample composition—with N = 152 participants not exclusively being students—influenced the results, the main findings were reanalyzed using only the student subsample (n = 118) and compared to those of the total sample.

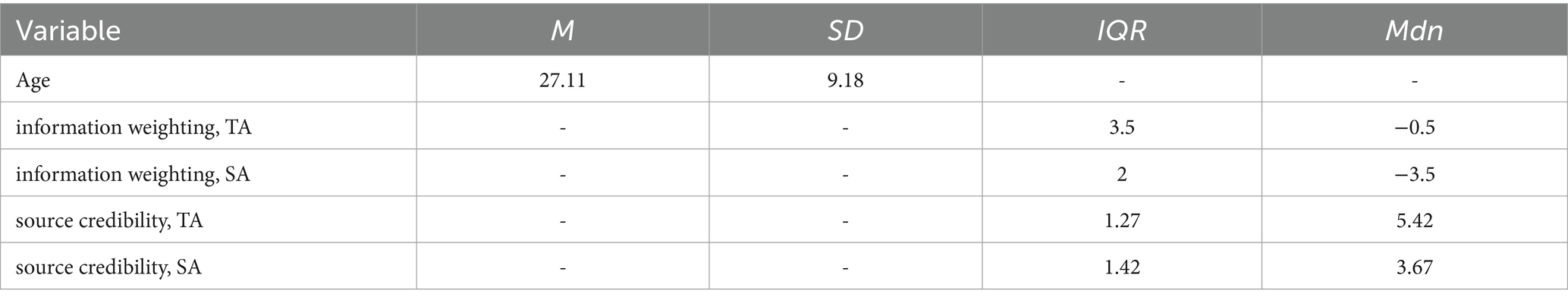

The participants were 19–67 years old (M = 27.11, SD = 9.18). However, 53% of our non-students reported having at least one academical degree (representing 12% of our sample). As 90% of our sample either have an academic degree or are right now students, we assume that they might easily be able to deal with our scenario of finding a learning partner. Details about the basic demographic data of all participants are presented in Table 1. The study was performed by using the software LimeSurvey. Participants were recruited via social media (Facebook) and the online survey platform SurveyCircle. As the study was freely available on these online platforms, no response rate could be determined, but a completion rate of 86.4% (152 out of 176 participants completed the study). The study took place between 16 June 2020 and 1 July 2020 and was completed in 10–15 min, no reward was granted to participants. There were no exclusion criteria except for the age as participants were required to be at minimum 18 years old. The core task for participants was to choose a partner for collaborative online learning at the university assuming that the most competent partner would preferably be chosen. Participants were presented with information about potential learning partners via anonymized profiles that indicated their partners’ estimated competence level (1–15) and gender and indicated the source of this information (external non-personal: knowledge test, external personal: teacher assessment, internal: self-assessment). This used selection of assessment types in our study represents only a selection of mostly common assessment types, even though not reflecting the full range of possible sources that especially learners might come across during their learning processes. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (reference ID: blinded for review).

Decision scenario and procedure

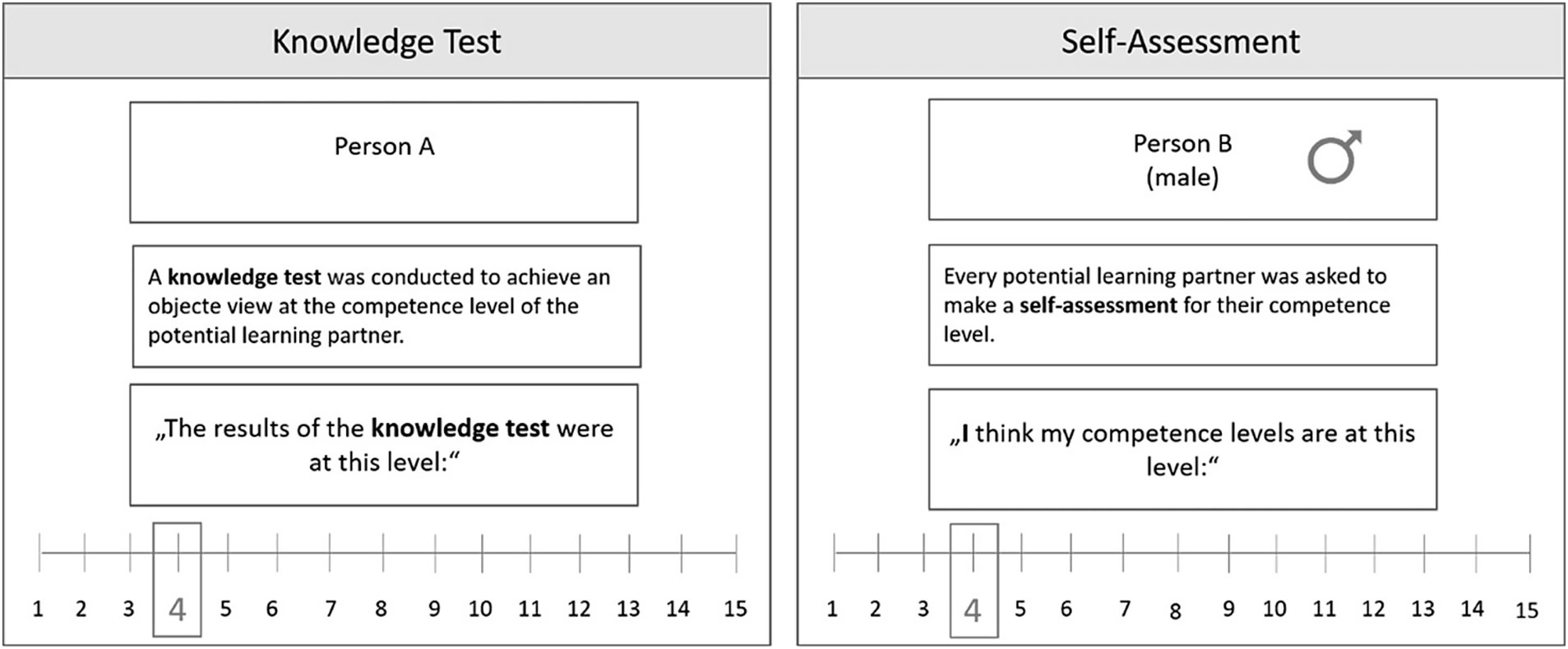

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. After completing a small test scenario where participants had to do a single decision to get used to the setting and design, the first group received profiles of potential partners with low competence levels (1–7) and the second group received profiles with high competence levels (9–15). Based on the performed randomization, 79 participants were assigned to the group with low competence levels, while 73 participants were assigned to the group with high competence levels. Participants had two options for each choice: Person A (left profile, gender of learning partner unspecified, competence level based on an external knowledge test either 4 or 12 depending on experimental condition); Person B (gender of learning partner specified varied within subject, competence level based on either external teacher or internal self-assessment varied within subject; Figure 2). A short information text thereby informed participants about the relevant source of each competence assessment on the profiles as shown in Figure 2 for knowledge tests and self-assessments profiles. In addition to this, teacher assessments were presented with this short description: “The professor estimated the competence of all candidates—The professor assesses the competences of this candidate as follows.”

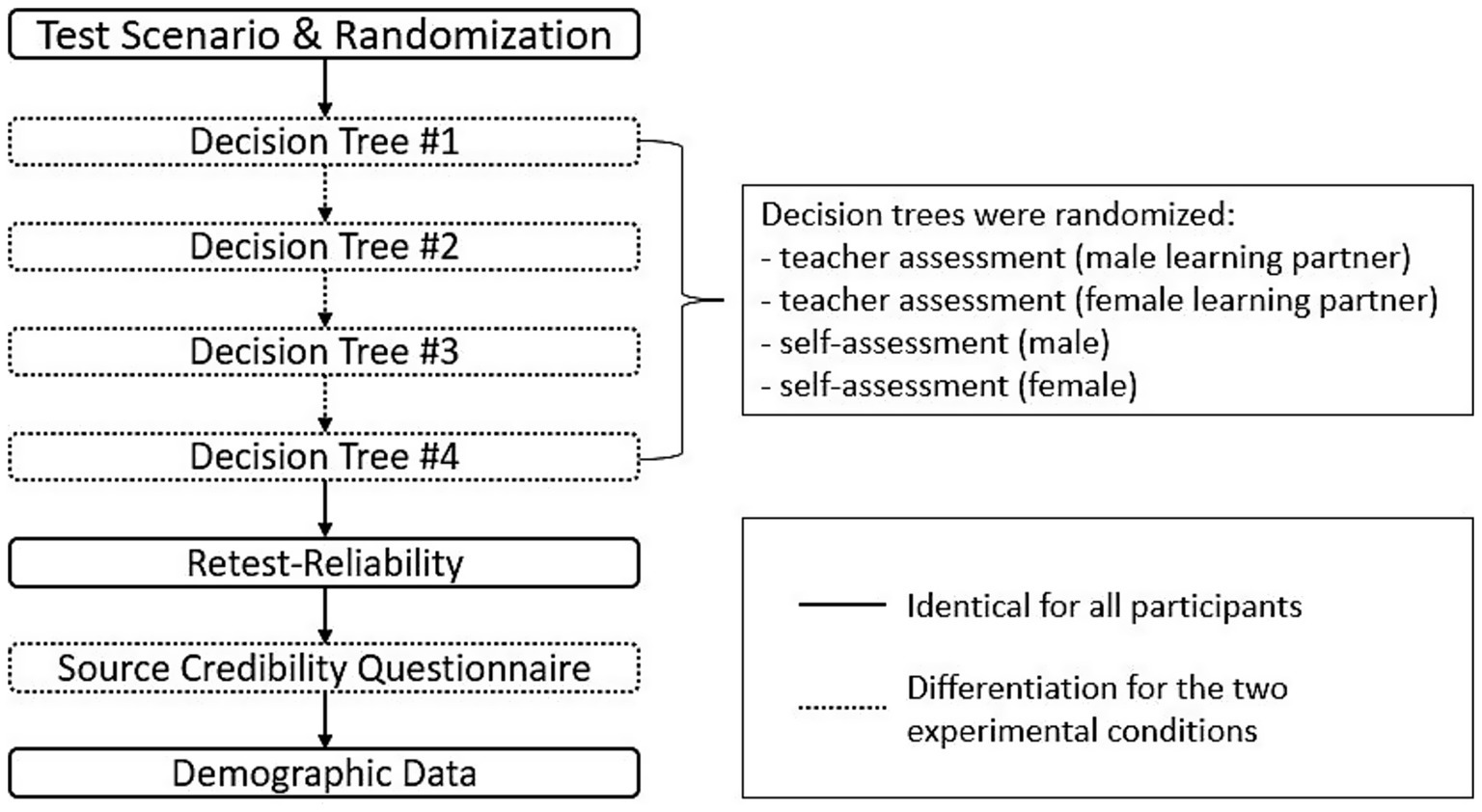

Similar to the procedure used by Freund et al. (2025), we used an adaptive algorithm to measure information weighting: Depending on participants’ individual choices, the profiles on the right changed based on a fixed-branch adaptive algorithm (Frey, 2007) to maximize the information gain with each decision of a participant and thus allowed to obtain information about information weighting based on three decisions. Participants had to make these three decisions for each combination of the two alternative sources (self-assessment and teacher assessment) and the two included gender (male and female), resulting in a total of four decision trees with a total of 12 decisions (3x2x2) per participant. The order of the four decisions trees was randomized per participant. Competence level was varied between conditions, so each participant only received one competence level. The overall procedure of the study is demonstrated in Figure 3.

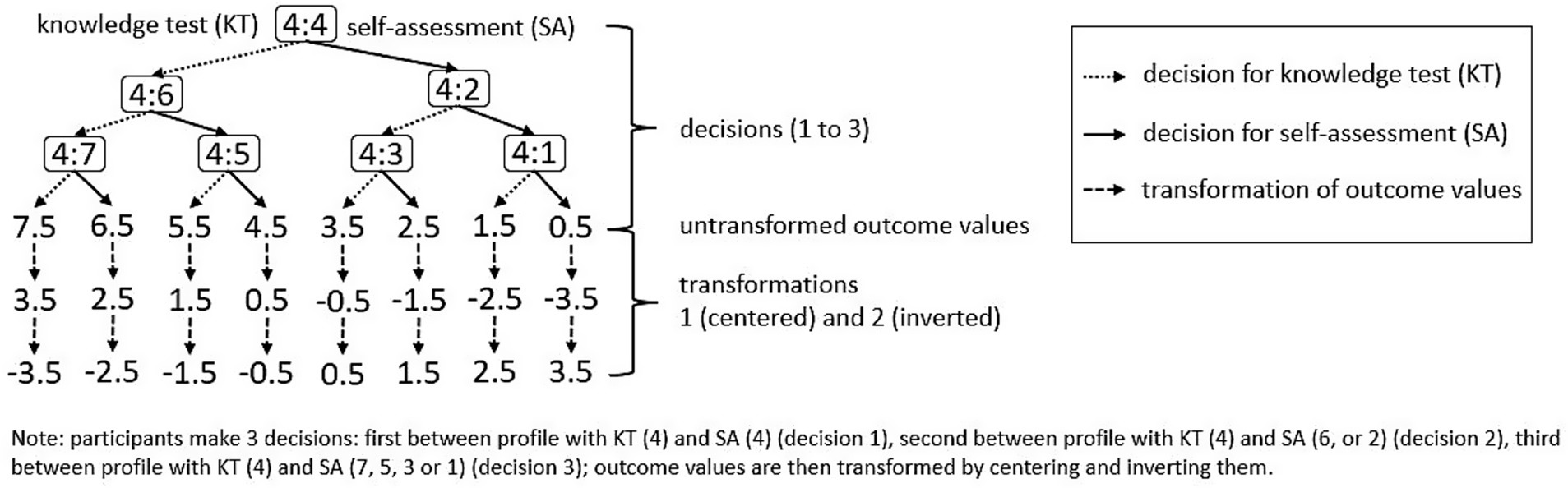

The first decision thereby was the same for all participants: both knowledge test and alternative source were at level 4 for low and 12 for the high competence condition. Participants had to choose between two profiles of potential learning partners that were both indicating a medium competence level (within their competence condition). While the left profile was always based on the results of a knowledge test (with a constant value through all decisions), the right profile changed in its respective value and was either based on a learner’s self-assessment or a teacher assessment for this profile. In all following decisions, the level of competence was then decreased or increased depending on previous choices. We assumed that if a participant chooses the person rated by the knowledge test with the same competence rating in both profiles (4 in the low-competence condition, 12 in the high-competence condition), an even lower alternative rating is unlikely to be more convincing (if people choose more competent partners). Thus, for the next decision, the level of competence in the right profile was increased to 6 (or 14), while the knowledge test remained constant at 4 (or 12). On the other hand, if a subject chooses the alternative source (teacher or self-assessment), we assumed that a higher level of competence would also be preferred compared to a knowledge test and thus reduced the value of the alternative sources to a 2 (or 10) in the next step, while—again—keeping the knowledge test rating constant at 4 (or 12; see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Example of a decision tree (low competence condition, self-assessment as alternative source).

This adaptive approach was designed to maximize the information gain from each decision using a fixed-branched adaptive algorithm (Frey, 2007). By minimizing the number of comparisons required by halving the remaining range of proficiency levels in each subsequent profile comparison, we aimed at reducing testing time which is a relevant factor especially in online settings. However, this approach also allows a more individualistic process for each participant: instead of assessing all existent profiles—which is a rather generic testing approach—participants only needed to do those decisions where we assumed to gain most information from. Having these adaptive comparisons of profiles helps to understand the importance and weighting of each source individually. By asking our participants to assess all existing profiles, we would have increased the number of decisions to seven per decision tree (instead of three). The overall number of decisions for the whole study would thereby be increased from 12 to 28. Using an adaptive approach substantially reduced the amount and time for participants to complete the study, concurrently optimizing the information gain for each decision.

Similar approaches are used, for example, in marketing contexts in the form of choice-based conjoint analyses which have emerged into a general experimental method. In these analyses in marketing contexts, the importance of certain features of a product is measured not by specifically measuring the importance of the feature itself but by measuring the preference of individuals for the whole product in comparison to 1–3 other products (Eggers et al., 2022). We slightly adjusted this approach by not only focusing on the preference of participants instead of the features itself but also including this adaptive algorithm to increase the insights from each choice. Participants in our experiment had to choose the best learning partner for their group based on profiles that indicated competence and gender of their potential partner. We used participants’ choice or preference between two learning partner profiles to deduce the importance and the weighting of the profile’s sources. The basic assumption thereby is that learners generally prefer highly skilled partners within their group. After completing the decision trees, participants evaluated the source credibility of four different profiles (see Figure 3 for study procedure).

Information weighting values

Participants require 3 decisions to complete a decision tree. This allows us to narrow down the decision point (i.e., the competence level where we assume profiles to be regarded as equally compelling) to an interval between two adjoined competence levels (e.g., 5 and 6). As estimate for the decision point we then use the mean between the two levels (e.g., 5.5). To represent the boundary values (no decision point located within tested range of competence levels) we use an estimate of 7.5 (15.5) or 0.5 (8.5) as theoretical minimum/maximum.

In our study, the knowledge test was assumed to be the most neutral source as the output of such a test should be identical with the same input which is a criterion that is not necessarily valid for teacher assessments or self-assessments. We hence decided to use the knowledge test results as a neutral reference value to have a fixed point of comparison for the evaluation of our different sources. Thus, a linear transformation was performed using the (fixed) knowledge test score as the reference point and setting it to the neutral value of 0 within each experimental condition (low competence: ylow = x–4; high competence: yhigh = x–12); see Figure 4. This also enables comparisons between experimental conditions. To allow for a more intuitive interpretation of our scores, we further recoded the scores so that negative scores indicate a lower information weighting, and positive scores indicate a higher information weighting (compared to the knowledge test; see Figure 4). Taking on values between −3.5 and 3.5, negative values thus represent a lower information weighting, while a positive value indicates a higher weighting.

Example for decision tree and information weighting

An example decision tree is shown in Figure 4 and could include the following decisions by a learner: In the first round, the learner is asked to choose between two performance profiles, both showing a rather low competence level of 4 (maximum competence: 15). While the left profile presumably comes from a knowledge test, the right profile is a self-assessment. Our exemplary participant decides that a knowledge test with a value of 4 is more convincing than a self-assessment with a value of 4. In the next step, we keep the knowledge test (value 4) constant but change the competence value of the alternative source to a 6 (e.g., self-assessment). Again, our participant chooses the knowledge test. In the next and final round, we again keep the knowledge test at a value of 4 but present a self-assessment at a value of 7. If our participant now chooses the self-assessment (value of 7), the learner will end up with an outcome value of 6.5. The outcome value measures the assumed level of competence that would be required for a participant to change his or her decision to switch from one profile source to the other. It reflects a hypothetical value between both final outcomes of each decision tree. As these values are not measurable and only theoretically defined, we decided to take an estimated value that is between both final outcome values of the decision trees. We assume that the true outcome value is somewhere between the first and second value, taking the mean value as our estimate. For example, if a participant prefers the knowledge test results all the time but chooses a self-assessment with a value of 7 in the last decision, we interpret this as follows: A self-assessment with a value of 6 was not enough to convince the participant to choose the self-assessed information. Instead, the knowledge test was chosen. However, with a value of 7, suddenly the self-assessed profile became more convincing than the knowledge test results. The value that is required for a participant to change the decision and switch from one source information to another, hence seems to be between 6 and 7. We hence define an outcome value of 6.5 for this decision scenario.

Source credibility

When examining source credibility as a measure, the source itself is identified as the most critical variable, which suggests that any variation in how information is weighted can be attributed to differences in the source. The underlying assumption here is that participants’ perceptions of the credibility of the source directly influence how they process and weight the information provided by that source. After decision trees were completed and all decisions were made, participants were presented with four distinct profiles for the evaluation of source credibility. In the low competence group, participants evaluated the credibility of one male and one female profile, each having a competence level of 4. These profiles were evaluated in both self-assessment and teacher-assessment conditions, allowing for a comparison between the two types of information sources. In the high competence group, the competence level of the four profiles was kept consistently at 12, representing a higher level of competence. Participants hence evaluated the source credibility of these four profile combinations: teacher assessment (male), teacher assessment (female), self-assessment (male), and self-assessment (female) with either a competence level of 4 or 12. This setup was designed to examine how the learning partner’s competence, as well as gender of learning partners and assessment type, affected participants’ credibility ratings.

To assess the credibility of the sources presented, participants were asked to complete a source credibility questionnaire developed by Gierl et al. (1997). This questionnaire included six items that were used to evaluate the sources: (1) competent, (2) experienced, (3) qualified, (4) trustworthy, (5) honest, and (6) selfish. These items were measured on a 7-point equidistant scale and could hence achieve values between 1 and 7. The responses were analyzed for internal consistency for each of the presented profiles to really understand the consistency under the individual conditions of each setting, with Cronbach’s α ranging from α = 0.75 to α = 0.92, indicating that the scale had good reliability.

Results

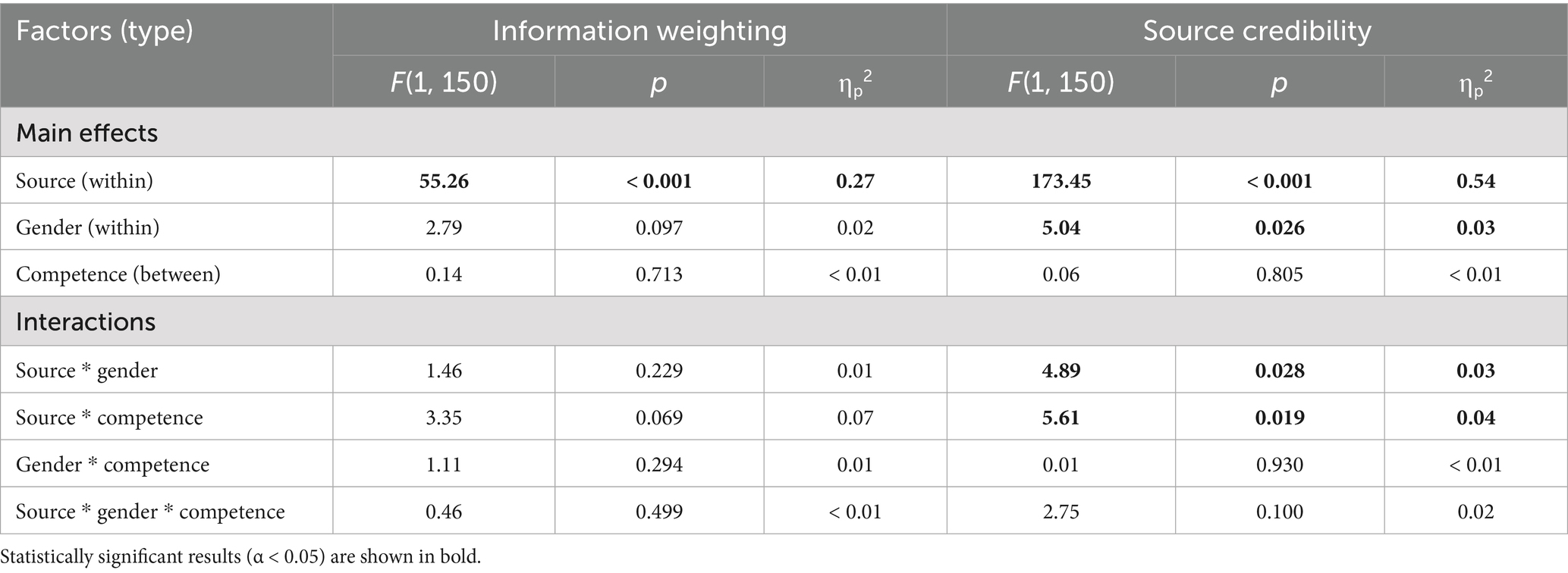

The descriptive statistics can be seen in Table 2. Normal distribution assumptions were not met for either source credibility or information weighting for all conditions and homogeneity of variances cannot be assumed. Because the complexity of the design limited the choice of nonparametric and no-assumption measures, we still decided to run three-way ANOVAs. We measured each independent variable for all factor levels (Table 3). However, we chose to confirm significant and interpretable main effects by using post-hoc nonparametric more robust tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Regarding the information weighting, Table 3 shows a significant main effect for the source, but no other significant main or interaction effects. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed a large effect (r = −0.52) for the assessment type on the information weighting with the teacher assessment being closer to our refence value from knowledge tests (=0; Mdn = −0.50, IQR = 3.5) than the self-assessment with a far lower information weighting (Mdn = −3.50, IQR = 2, z = −6.45, p < 0.001). This means that in comparison, teacher assessment was given more weight than self-assessment. However, as multiple testing was performed for all significantly identified main effects, we corrected our assumed p-value from p = 0.05 to p = 0.017 (Bonferroni-correction). A one sample Wilcoxon-test comparing the values to the knowledge test value (0) showed significant deviation for both teacher assessment (Mdn = −0.5, SD = 2.25), p = 0.001, and self-assessment (Mdn = −3.5, SD = 1.87), p < 0.001, with negative values for both. This indicates that the external sources (knowledge test and teacher assessment) were both given more weight than the internal source (self-assessment) and within the external sources, the non-personal (knowledge test) was given more weight than the personal (teacher assessment). No significant effects of gender or competence of learning partners were found regarding information weighting.

Regarding effects on source credibility, we found a strong main effect of source, with teacher assessment (Mdn = 5.42, IQR = 1.27) being perceived as significantly more credible than self-assessment (Mdn = 3.67, IQR = 1.42, z = −8.13, p < 0.001, r = −0.66). We also assumed that learners’ perceptions of source credibility might influence their information weighting of these sources. Spearman correlations were hence calculated to see if this assumption could be confirmed. We identified Spearman correlations between information weighting and source credibility ratings (TA: ρ = 0.31, p = 0.001; SA: ρ = 0.40, p = 0.001) that indicate some moderate correlation between these.

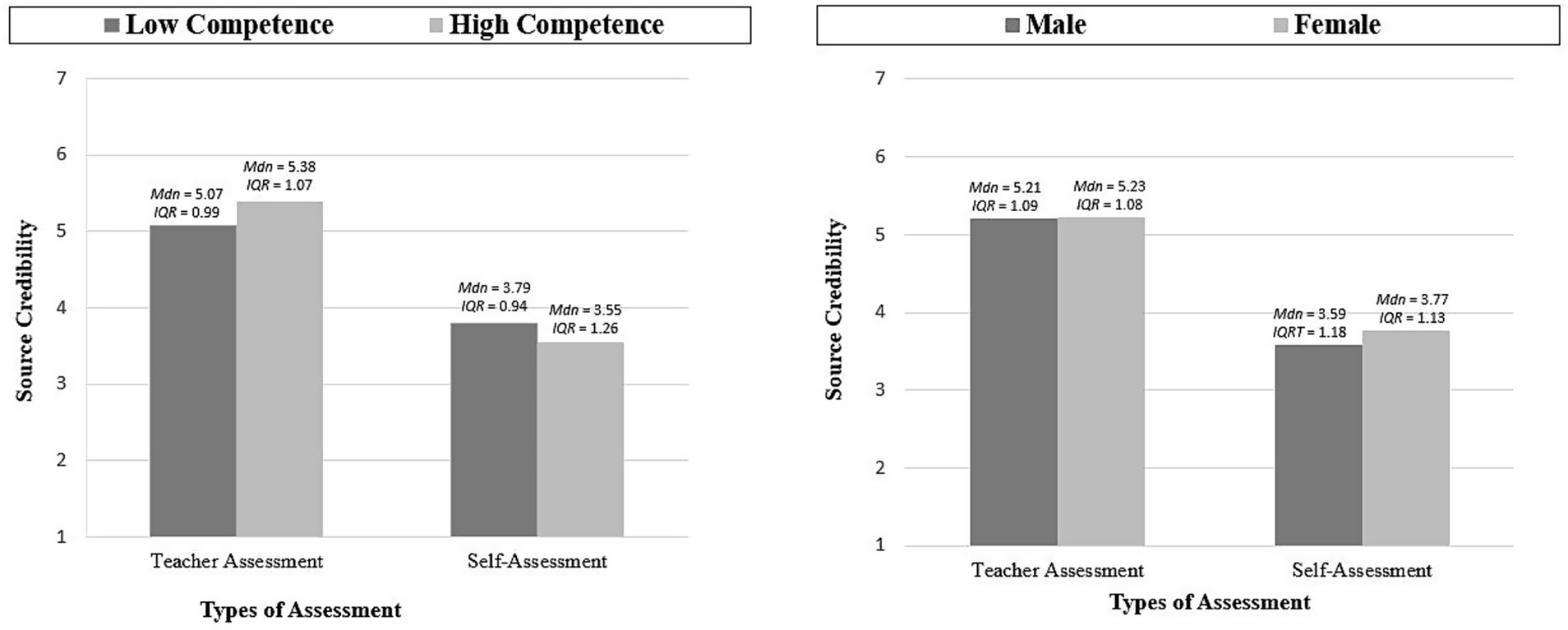

If we look at possible effects based on the gender of learning partners, we can see a significant main effect on source credibility as well as an interaction effect of source type and gender (Table 3; right, Figure 5). A Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni-corrected p-value (0.017), however, could not confirm the main effect of learning partner’s gender.

Regarding the effects of competence level, we found no significant main effects, but an interaction with source type (Table 4; right, Figure 5). The identified interaction showed that the effect of source is stronger for the high competence level than for low competence level (Figure 5, left). While teachers seem to be perceived as more credible when attesting high competence rather than low competence, self-assessments seem to lack credibility for all competence levels but even more for high competence levels.

The analysis of a subsample consisting exclusively of students showed that the main results followed the same pattern as those of the total sample which supports the assumption that the insights gained from the experiment are potentially generalizable, increasing the robustness of the findings.

Exploratory sub-analyses

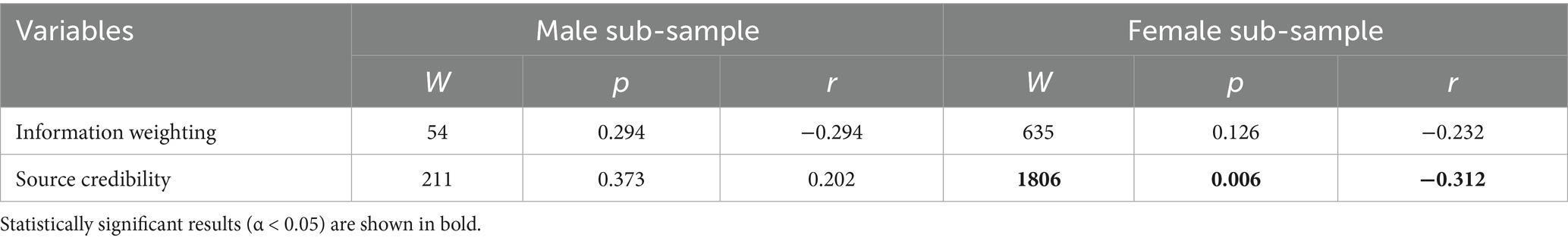

For an additional, but more explorative sub-analysis of our data, we created two sub-samples; male participants (n = 34) and female participants (n = 116). To get a deeper understanding of potential gender effects, seeing if homo-or heterogeneity of gender need to be considered, we checked if there are differences within the male and female sub-sample for the information weighting and source credibility of male and female learning partners—we hence considered participants’ gender and gender of potential learning partners. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed for each sub-sample as follows (see Table 3).

Focusing on these analyses, no significant effects for information weighting in either the male or female sub-samples were found. In contrast, source credibility showed a significant effect for female participants. These findings show that both sub-samples do not differ from each other considerably, but female participants in our study indeed evaluated the source credibility of male learning partners (Mdn = 4.42, IQR = 1.17) differently compared to female learning partners (Mdn = 4.58, IQR = 1.08). This effect could indicate that female learners perceive female learning partners as potentially more credible compared to male learning partners. However, as the main effect for gender could not be confirmed for source credibility after Bonferroni-correction, this medium effect should only be interpreted conservatively and was used only as an explorative addition.

Discussion

This study investigated how different internal, or external source types interacted with gender of a potential learning partner, and competence level of a potential learning partner. In line with Freund et al. (2025), we found that external sources (teacher assessments) are perceived as more credible than internal assessments (self-assessments) across gender and competence levels. Internal self-assessed performance estimates seem to be perceived as lacking credibility. Consistent with our assumptions, but also with the existing literature, this confirms that internal personal self-assessments, which are often unrealistically positive (e.g., Skala, 2008), are perceived as the least credible source in group awareness tools designed for selecting learning partners.

When focusing on the credibility of sources, gender effects seem to be negligible as identified main effects could not be confirmed with corrected p-values for multiple testing. Participants seem to assume that women who self-assessed their competence level for our profiles are more credible than men but as we could not confirm this main effect, these findings need to be treated with some caution and confirmed in further research. Gender effects have been considered relatively rarely in group awareness research. We found only few differences for source credibility of teachers, when teachers assess their students (external teacher assessments), which contrasts findings of Sarani et al. (2020), who found that female teachers have higher credibility compared to their male colleagues. Although external personal teacher assessment was generally found to have higher source credibility than internal personal self-assessment, the identified interaction effect shows that especially for self-assessment, female sources seem to have higher credibility.

Considering the effects of misestimation with respect to self-assessments, it seems to be expected that highly rated profiles may simply result from overconfidence (e.g., Ludwig and Nafziger, 2011), leading to lower credibility. Thus, while a main effect for competence was not found, competence level was found to interact with the source for source credibility, see Figure 5. In general, teacher assessments seem to be perceived as more credible than self-assessments, regardless of the respective competence level. However, when the competence level for teacher assessments is higher, people tend to rate these assessments as more credible, whereas it is the other way around for self-assessments. A possible explanation could be that both sources are expected to be biased, but differently. Teachers may be perceived as being rather too critical resulting in perceiving them as more credible when providing favorable estimates. Conversely, self-assessments may be considered as too favorable and thus perceived as more credible when they are critical. A critically low self-assessment could potentially be perceived as more credible and realistic, since in most meritocratic societies it is undesirable to be judged as less competent. The likelihood that someone would mistakenly (or even intentionally) rate themselves at a low level of competence may have been considered quite low.

Nevertheless, it needs to be noted that external sources were still perceived as more credible and given more weight than internal sources and within these, non-personal sources were given the most weight. Internal assessments (self-assessments) were perceived as less credible than both external assessment types (knowledge tests and teacher assessments), regardless of competence level. When examining the information weighting, learners preferred teacher assessments more than self-assessments. Here, information from teacher assessments and test results are given significantly more weight than information from self-assessments, while the first two seem to differ less.

However, knowledge tests seemed to be chosen even more often than teacher and self-assessments, with only a small difference between teacher and knowledge tests. Self-assessments often tend to be biased, either overestimating or underestimating (Kruger and Dunning, 1999). However, as the source of the assessment is the to-be-assessed person, advantages, and disadvantages of self-assessment as a source within group awareness tools need to be considered.

In group awareness tools, data providers and recipients are often identical, although this was different in our study where participants chose partners but were not chosen themselves and thus not asked to provide information about themselves. From the perspective of information provider, self-provided information allows to control the information about oneself. Therefore, it is assumed that self-assessed performance estimates achieve higher acceptance among learners because they understand the origin of the information, which represents their own perspective and tapping into own experiences during self-reflection may even promote metacognitive learning processes (Schnaubert and Bodemer, 2019). This may also provide a sense of understanding and perceived control over one’s own data, compared to externally collected data where the origin of the information is vague. However, in group awareness tools, information is also evaluated by others, and the source of information may be of paramount importance for peers to judge its credibility. Our data show that information from self-assessments is given less weight and perceived as less credible than information from teacher assessments or tests. This indicates a potential conflict in using self-assessed information as a source: While self-assessed information may be perceived as more authentic by learners themselves (Schnaubert and Bodemer, 2019), it is also sometimes assumed to be less reliable (e.g., Erkens et al., 2016), and our study shows that this assumption extends to learners using a group awareness tool to choose learning partners.

It is also interesting to note that information from teacher assessments was given less weight and perceived as less credible than test results. This may seem logical, as non-personal tests may provide more objective information. However, while a test may contain only a few predefined questions or tasks, teachers usually know learners over a longer period and may include different performance parameters in their judgments. Especially in alternative learning environments, such as FUSE classrooms, where teachers act as guides and facilitators (Ramey and Stevens, 2020), it is important to consider that their assessments may be weighted differently than, for example, tests or self-assessments. Nonetheless, learners have weighted test results as more reliable overall, possibly assigning more neutrality to these tests. However, it should be noted that the difference between the information weighting from teacher assessments and the information weighting from knowledge tests appears to be rather small, so a possible effect needs to be investigated further. Interestingly, all values for information weighting were found to be negative, indicating that all information provided from the different sources was weighted less than information from knowledge tests. In the context of group awareness tools, these findings may be crucial, as the source of group awareness information is fundamental. Considering these results, it seems advisable to be aware of the consequences of using self-assessed information in group awareness tools, at least when potential learning partners are unknown and low source credibility may prevent interaction processes in the first place.

The results must be interpreted with some limitations. Although we used robust methods to confirm the identified main effects, especially the interaction effects must be interpreted with caution (violated assumptions). In addition, the rather abstract scenario used in our study (with limited awareness information but forcing participants to use the given information as a guide for their choices) may be a limiting factor. While this minimalist procedure allowed us to control for possible influences, the results cannot simply be generalized to actual peer learning scenarios where learners need to form a group to collaborate. Thus, it is quite possible that learners could compensate for the lack of credibility of a source by referring to other accessible parameters. In addition, learners were only considered as users of the group awareness tool but were not included in the tool as potential learning partners themselves, which might also have a potential influence on their actions. For the design of the study, we also decided to use the competence level as between-factor to avoid a too monotonous approach for our participants that would potentially decrease the quality of the results of the study. Furthermore, although we limited the number of decisions participants had to make by using an adaptive algorithm, they still had to make several consecutive (potentially fatiguing) decisions. In terms of gender effects, Mullola et al. (2011) investigated whether male and female teachers perceive the temperament and competence of male and female students differently. Interestingly, they found only small differences between the assessment of male and female students when assessed by male teachers. Female teachers’ assessments, interestingly, showed a larger overall difference between the assessments of male and female students. Although these effects showed a bias for the assessments made by female teachers (when assessing both male and female students), we found that women tended to be perceived as more credible. However, in our predominantly female sample (ratio of 3.4:1, with n = 116 female, n = 34 male participants, and n = 2 not assigned), participants were asked to indicate the gender they personally identify with. It is important to note that gender is not binary at all and can be perceived in multiple ways which needs to be considered when investigating gender effects in general. However, in order to be able to examine and measure the effects of (perceived) partner gender, we focused on traditional gender roles rather than the individual understanding of gender. Due to the predominantly female sample, effects of gender homo-or heterogeneity must be considered as an alternative explanation for the observed gender effects. Also, the generalizability of our findings could be limited by this gender imbalance with more female than male participants. Future research should investigate more balanced samples to review and possibly confirm findings of this study, A possible explanation for the imbalanced gender ratio in our study could be the distribution channels used (Facebook, SurveyCircle) as these might already have a biased gender ratio in their user statistics. This imbalance, however, was not intended or manipulated.

As the decision-making processes and perceptions of information sources appear to be comparable regardless of the sample composition, results can be considered transferable to real university learning scenarios. This has been demonstrated by the analysis of the student-subsample. Main results for the student-sample were nearly identical to those from the total sample. This suggests that the findings are potentially generalizable, increasing the robustness of the findings.

In the more exploratory sub-analysis, investigated potential gender effects in two sub-samples (male; female). The aim was to explore whether gender homogeneity (i.e., same-gender learning partners) or heterogeneity (i.e., different-gender learning partners) might play a role in how participants weighted information and perceived the credibility of sources. The results (Table 3) indicated that there were no significant differences in information weighting based on the gender of the learning partner for either group. However, female participants rated female learning partners as significantly more credible than male learning partners. Such an effect could not be confirmed for male participants. These findings suggest that female learners may perceive higher source credibility when interacting with same-gender learning partners. It is important to note, however, that this result should be interpreted with caution. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, the unequal group sizes, and the fact that main effects for gender in the total sample could not be confirmed, the observed effect should not be considered robust, but rather as an indication that warrants further investigation in future research.

In addition, the definition of the partner role in our scenario is quite complex. When an external source (e.g., a teacher) provides an assessment, it is clear who the source (the teacher) is and who is being assessed (the to-be-assessed-person; profiles in our scenario). In self-assessment situations, however, the source (the self-assessment) is also the to-be-assessed person. While analyses of, e.g., gender or competence level focus on attributes of the possible learning partner only, investigations of sources might be influenced also by the attributes (as, e.g., gender) of the sources themselves, which must be considered when discussing the results of this study. Lastly, it needs to be considered that the study took place in a pure online setting. Some of the mentioned studies in the theoretical section also used online settings which shows that these scenarios can—with all the known challenges—still provide fruitful insights. However, we still need to keep in mind that the study environment as well as the attention of participants is not easily controllable in such a study design influencing its ecological validity.

Conclusion

Confirming the findings from the reproduced research from Freund et al. (2025), sources were shown to be essential for the weighting of the provided group awareness information (main effect) as well as for the credibility of the source (main effect & interactions with gender and competence of a potential learning partner). People usually base their decisions on personal experiences and perceptions, which may be limited in computer-mediated communication scenarios where available information may be limited. The source of group awareness information might influence if and how information is perceived and possibly used. This also influences how possible learning partners are chosen, as learners need to weight the information provided, reflecting on the reliability and credibility of sources and information. Considering this, the importance of the design of group awareness tools becomes even more important, as the design of a tool can influence the use of the tool and the information presented (e.g., by showing the source of information, by keeping the source of information anonymous, etc.).

Furthermore, if the identified difference between the information weighting from teacher assessments and the information weighting from knowledge tests is small, it is worth investigating which source might be more beneficial (in which scenario). When designing group awareness tools, it might be useful to know whether teacher assessments or knowledge tests are a better choice as a source, or whether they can be treated as equally valuable sources.

We partially confirmed our hypotheses and identify some interesting exploratory findings with respect to competence levels. Finding interactions between source and gender of the learning partner, and source and competence level, showed that both interactions affect source credibility in different ways in our scenario. What still remains unclear is the question of how exactly participants interpreted the individual sources (especially knowledge tests and teacher assessments). The credibility, perception and even usage of such information might strongly depend on which assumptions learners make when interpreting a source. While mainly used as a reference point in our study, future research could include knowledge tests as well as other source types or their combination as factor levels to further differentiate between different sources and their effects of tool use. Our results confirm the previous findings of Freund et al. (2025), suggesting that information from KTs is weighted more heavily than other types of assessment, but how this relates to source credibility and how it compares to other sources is still unclear. In this study, gender was only examined as a characteristic of the to-be-assessed person, respectively the learning partner. Therefore, it might be interesting to systematically investigate other aspects, such as the gender of the participants, to see if gender homogeneity is crucial in this context. It needs to be considered, however, that a generalizability of the identified gender effects cannot clearly be confirmed due to the imbalance of gender of participants of this study. Future research could investigate more balanced samples to confirm. Furthermore, it could be investigated whether the identified effects can be generalized to be relevant not only for competence or gender, but also for other characteristic factors.

Additional parameters of the to-be-assessed people could be transferred to a realistic, less artificially created scenario, gaining insights from possible field studies. The acceptance of information in group awareness tools is the linchpin of the acceptance of the tools themselves. Thus, knowledge about the assessment and impact of information sources can increase the effectiveness of group awareness tools and further social technologies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article is openly available on “figshare” at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29620382.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Local ethics committee at the University of Duisburg-Essen. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

L-JF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. DB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maite Bandurski for her contribution to this study by supporting planning and collecting data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albright, M. D., and Levy, P. (1995). The effects of source credibility and performance rating discrepancy on reactions to multiple raters. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 577–600.

Ayeh, J. K. (2015). Travellers’ acceptance of consumer-generated media: an integrated model of technology acceptance and source credibility theories. Comput. Hum. Behav. 48, 173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.049

Bigham, A., Meyers, C., Li, N., and Irlbeck, E. G. (2019). The effect of emphasizing credibility elements and the role of source gender on perceptions of source credibility. J. Appl. Commun. 103:2. doi: 10.4148/1051-0834.2270

Bodemer, D., and Dehler, J. (2011). Group awareness in CSCL environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 1043–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.014

Bodemer, D., Janssen, J., and Schnaubert, L. (2018). “Group awareness tools for computer-supported collaborative learning” in International handbook of the learning sciences. (eds.) F. Fischer, C. E. Hmelo-Silver, S. R. Goldman, and P. Reimann. (New York: Routledge), 351–358.

Cai, H., and Gu, X. (2019). Supporting collaborative learning using a diagram-based visible thinking tool based on cognitive load theory. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 2329–2345. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12818

Chou, C. Y., and Zou, N. B. (2020). An analysis of internal and external feedback in self-regulated learning activities mediated by self-regulated learning tools and open learner models. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 17, 1–27. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00233-y

De Grez, L., Valcke, M., and Roozen, I. (2012). How effective are self-and peer assessments of oral presentation skills compared with teachers’ assessments? Act. Learn. High. Educ. 12, 129–142. doi: 10.1177/1269787a412441284

Dehler, J., Bodemer, D., Buder, J., and Hesse, F. W. (2011). Guiding knowledge communication in CSCL via group knowledge awareness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 1068–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.018

Dunning, D., Heath, C., and Suls, J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 5, 69–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x

Eggers, F., Sattler, H., Teichert, T., and Völckner, F. (2022). “Choice-based conjoint analysis” in Handbook of market research. eds. C. Homburg, M. Klarmann, and A. Vomberg (Springer), 781–819.

Erkens, M., Bodemer, D., and Hoppe, H. U. (2016). Improving collaborative learning in the classroom: textmining based grouping and representing. Int. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn. 11, 387–415. doi: 10.1007/s11412-016-9243-5

Falchikov, N. (1995). Peer feedback marking: developing peer assessment. Innov. Educ. Train. Int. 32, 175–187.

Feron, E., Schils, T., and Weel, B. (2016). Does the teacher beat the test? The value of the teacher’s assessment in predicting student ability. De Economist 164, 391–418. doi: 10.1007/s10645-016-9278-z

Fogg, B. J., Marshall, J., Laraki, O., and Osipovich, A. (2001). What makes web sites credible? A report on a large quantitative study. CHI '01: Proceed. SIGCHI Confer. Human Factors Comput. Syst. 3, 61–68. doi: 10.1145/365024.365037

Freund, L.-J., Bodemer, D., and Schnaubert, L. (2025). External and internal sources of cognitive group awareness information: effects on perception and usage. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 20:11. doi: 10.58459/rptel.2025.20011

Frey, A. (2007). “Adaptives Testen” in Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion. eds. H. Moosbrugger and A. Kelava (Berlin: Springer), 261–278.

Gaj, N. (2016). Unity and Fragmentation in psychology: The philosophical and methodological roots of the discipline. 1st Edn. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routlege.

Ghadirian, H., Ayub, A. F. M., Silong, A. D., Bakar, K. A., and Hosseinzadeh, M. (2016). Group awareness in computer-supported collaborative learning environments. Int. Educ. Stud. 9, 120–131. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n2p120

Gierl, H., Stich, A., and Strohmayr, M. (1997). Einfluß der Glaubwürdigkeit einer Informationsquelle auf die Glaubwürdigkeit der Information. Mark. ZFP J. Res. Manag. 1, 27–31.

Haim, M., and Maurus, K. (2023). Stereotypes and sexism? Effects of gender, topic, and user comments on journalists’ credibility. Journalism 24, 1442–1461. doi: 10.1177/14648849211063994

Hovland, C. I., and Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 15, 635–650.

Janssen, J., and Bodemer, D. (2013). Coordinated computer-supported collaborative learning: awareness and awareness tools. Educ. Psychol. 48, 40–55. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2012.749153

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., and Kirschner, P. (2011). Group awareness tools: it’s what you do with it that matters. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 1046–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.002

Jay, V., Henricks, G., Anderson, L., and Bosch, N. (2020). “Online Discussion Forum Help-Seeking Behaviors of Students Underrepresented in STEM.” ICLS 2020 Proceedings, 809–810.

Jermann, P., and Dillenbourg, P. (2008). Group mirrors to support interaction regulation in collaborative problem solving. Comput. Educ. 51, 279–296. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.012

Keplová, K. (2022). Self-assessment, self-evaluation, or self-grading: what’s in a name? Pedagog. Orient. 32, 368–386. doi: 10.5817/PedOr2022-4-368

Kruger, J., and Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 1121–1134.

Kwon, K. (2019). Student-generated awareness information in a group awareness tool: what does it reveal? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 1301–1327. doi: 10.1007/s11423-019-09727-7

Li, Y., Li, X., Zhang, Y., and Li, X. (2021). The effects of a group awareness tool on knowledge construction in computer-supported collaborative learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52, 1178–1196. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13066

Ludwig, S., and Nafziger, J. (2011). Beliefs about overconfidence. Theor. Decis. 70, 475–500. doi: 10.1007/s11238-010-9199-2

Moreno, J., Ovalle, D. A., and Vicatir, R. M. (2012). A genetic algorithm approach for group formation in collaborative learning considering multiple student characteristics. Comput. Educ. 58, 560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.011

Mullola, S., Ravaja, N., Lipsanen, J., Alatupa, S., Hintsanen, M., Jokela, M., et al. (2011). Gender differences in teachers’ perceptions of students’ temperament, educational competence, and teachability. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 185–206. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2010.02017.x

Nagle, J. E., Brodsky, S. L., and Weeter, K. (2014). Gender, smiling, and witness credibility in actual trials. Behav. Sci. Law 32, 195–206. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2112

Nicol, D. J., and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessments and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High. Educ. 31, 199–218. doi: 10.1080/03075070600572090

Noble, S., and Shanteau, J. (1999). Information integration theory: a unified cognitive theory. J. Math. Psychol. 43, 449–454.

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 19, 39–52.

Ramey, K., and Stevens, R. (2020). “Best Practices for Facilitation in a Choice-based, Peer Learning Environment: Lessons From the Field.” ISLS 2020 Proceedings, 1982–1989.

Revelo Sánchez, O., Collazos, C. A., and Redondo, M. A. (2021). Automatic group organization or collaborative learning applying genetic algorithm techniques and the big five model. Mathematics 9, 1–23. doi: 10.3390/math9131578

Sangin, M., Molinari, G., Nüssli, M., and Dillenbourg, P. (2011). Facilitating peer knowledge modeling: effects of a knowledge awareness tool on collaborative learning outcomes and processes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.032

Sarani, A., Negari, G. M., and Sabeki, F. (2020). Educational degree, gender and accent as determinants of EFL teacher credibility. Iran. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 8, 153–164.

Schnaubert, L., and Bodemer, D. (2019). Providing different types of group awareness information to guide collaborative learning. Int. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn. 14, 7–51. doi: 10.1007/s11412-018-9293-y

Schnaubert, L., Harbarth, L., and Bodemer, D. (2020). “A psychological perspective on data processing in cognitive Group Awareness Tools” in The Interdisciplinarity of the Learning Sciences. eds. M. Gresalfi and I. S. Horn, 951–958.

Siqin, T., van Aalst, J., and Wah Chu, S. K. (2015). Fixed group and opportunistic collaboration in a CSCL environment. Int. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn. 10, 161–181. doi: 10.1007/s11412-014-9206-7

Skala, D. (2008). Overconfidence in psychology and finance – an interdisciplinary literature review. Bank i Kredyt 4, 33–50.

Sternthal, B., Phillips, L. W., and Dholakia, R. (1978). The persuasive effect of source credibility: a situational analysis. Public Opin. Q. 42, 285–314.

Stone, D. L., Gueutal, H. G., and McIntosh, B. (1984). The effects of feedback sequence and expertise of the rater on perceived feedback accuracy. Pers. Psychol. 37, 487–506.

Tang, X., Wang, Q., Li, Y., and Yu, S. (2025). Design group awareness tool for online community: could the aggregated social knowledge network facilitate social interaction? Interact. Learn. Environ., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2025.2478442

Todd, P. R., and Melancon, J. P. (2018). Gender and live-streaming: source credibility and motivation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 12, 79–93. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-05-2017-0035

Winter, S., and Krämer, N. C. (2014). A question of credibility – effects of source cues and recommendations on information selection on news sites and blogs. Communications 39, 435–456. doi: 10.1515/commun-2014-0020

Wolf, A. G., Rieger, S., and Knauff, M. (2012). The effects of source trustworthiness and inference type on human belief revision. Think. Reason. 18, 417–440. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2012.677757

Keywords: group awareness, information weighting, source credibility, competence level, gender effects, learning partner selection

Citation: Freund L-J, Schnaubert L and Bodemer D (2025) Acceptance of group awareness information from varying sources: on competence and gender. Front. Educ. 10:1545766. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1545766

Edited by:

Octavian Dospinescu, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, RomaniaReviewed by:

Keiichi Kobayashi, Shizuoka University, JapanFlorian Schmidt-Borcherding, University of Bremen, Germany

Wang Yijie, Yunnan University of Finance and Economics, China

Copyright © 2025 Freund, Schnaubert and Bodemer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura-Jane Freund, bGF1cmEtamFuZS5mcmV1bmRAc3R1ZC51bmktZHVlLmRl

Laura-Jane Freund

Laura-Jane Freund Lenka Schnaubert

Lenka Schnaubert Daniel Bodemer

Daniel Bodemer