- 1Wisconsin Center for Education Research, School of Education, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, United States

- 2Columbus City Schools, Columbus, OH, United States

- 3Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Introduction: This paper is a case study of equity-centered continuous improvement that informed school leader professional learning. The work is a collaboration between researchers and district leaders in Columbus City Schools, USA. The continuous improvement process took place in the context of a multi-year, grant-funded initiative aimed at expanding school leaders’ capacity to advance equity in their buildings.

Methods: Our findings are based on a thematic analysis of qualitative data that include interviews, field notes, and artifacts.

Results: We highlight three social conditions that made the improvement work possible: a district-wide focus on equity, a culture of learning, and partnerships with external organizations. We explore in detail two examples of continuous improvement in the district, both related to school leader professional learning. We shed light on factors that hindered the district-wide use of continuous improvement in the district, including the absence of guidance on continuous improvement and the emerging nature of the collaboration among principal supervisors and coaches across the district.

Discussion: This work contributes to the field’s understanding of what equity-focused continuous improvement can look like. Our findings suggest that equity-centered continuous improvement encompasses equity-focused goals that aim to address disparities in students’ school experiences, and equity-focused processes that cultivate trust with school leaders and position them as capable learners and agents of change.

1 Introduction

Continuous improvement is a promising approach for understanding and addressing persistent inequities in education systems (e.g., Bevan and Penuel, 2018; Bryk et al., 2015). It enables individuals “to learn about the experiences of those who are directly impacted by systems, and to use that learning to design better systems with and for those directly impacted” (Valdez et al., 2020, p. 2). This paper is a case study of what infusing equity in the process of improving may look like (Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022). It highlights the work of central office leaders in one large urban district in the United States that took place in the context of a multi-year grant-funded initiative focused on leadership for equity. The initiative began in 2021–2022 and will end in 2025–2026. Our investigation addresses one specific issue: supporting school principals in advancing equity in their buildings, and focuses on the first three and a half years of the initiative (September 2021–December 2024).

Our analysis explores how the district leveraged continuous improvement to support leadership for equity in schools. This focus enables us to both do justice to the process as it unfolded and contribute to the field’s emerging understanding of equity-focused continuous improvement. Our insights are based on qualitative analysis of artifacts, interviews, and group discussions. We begin by describing the district’s theory of action related to leadership for equity. We then discuss the social conditions that made the equity-focused work possible. We provide two illustrative examples of improvement processes in the district. Our exploration highlights both practices and outcomes. We also outline factors that hindered the continuous improvement process and prevented the use of continuous improvement by all members of the principal support team. We discuss implications of our findings for practitioners and for the field.

Together with the other contributions to this special issue, we hope that this case study helps define equity-centered continuous improvement by providing a powerful example of its instantiation in practice. We define equity-focused continuous improvement as continuous improvement in an equity focused context, which requires both equity-focused goals and equity-focused processes.

Our inquiry was guided by the following research questions, all of which center on the focus issue of supporting school leaders:

1. What social conditions enabled district efforts to design for equity-centered continuous improvement?

2. What did the equity-centered continuous improvement process in the district look like in terms of process and outcomes?

3. What forces hindered their designs for equity-centered continuous improvement?

This case study is situated in one US school district: Columbus City Schools (CCS). Like any other urban district, CCS is a large and complex education system. Our exploration focuses on the work of the district’s office of leadership development. The case study enables us to explore in detail how principal supervisors and principal coaches put in place relationships and practices that expanded school leaders’ capacity to lead for equity. We use the district’s definition of equity, which foregrounds each students’ “access to the resources, opportunities, and supports they need to develop to their full academic and social–emotional potential” (Columbus City Schools, n.d.). We hope that the rich description in this paper will enable our readers to see themselves in the work we describe, and make judgments about how the contexts they strive to shape may be similar to as well as different from the one we explore.

1.1 Context of the grant initiative and continuous improvement

The work we explore in this paper took place in the context of a five-year initiative funded by The Wallace Foundation, a US philanthropic organization. The name of the initiative is the Equity Centered Pipeline Initiative (ECPI), and it focuses on supporting leadership for equity in schools. The initiative began in the fall of 2021, and included eight large urban districts in different geographic regions of the United States, including CCS. All districts applied to participate in the grant, and were selected by the foundation based on a number of factors, including the stability of senior district leadership. We describe the initiative itself and its theory of change to situate our case study within a broader context and shed light on some of the external forces that supported the district leaders’ continuous improvement efforts.

The foundation approached school-level change with an emphasis on district leadership and cross-organizational partnerships. To participate, each district was asked to partner with two institutes of higher education, a state education agency, and a community organization. Representatives of these organizations and district leaders then formed a district partnership team. Each district had discretion in choosing its partners. The size of the partnership teams varied but tended to include a core of about ten members. The partnership team was led by a district staff member. This staff member’s position was paid for by the grant and in most districts focused almost exclusively on grant-related activities.

The ECPI theory of change emphasized continuous improvement. Our analysis of this theory draws on documents produced by the foundation in relation to the initiative, such as the Research Studies Request for Proposals (RFP) and the Scope of Work for Year 1, as well as an interview with a foundation staff member familiar with the initiative.

The initiative’s theory of change was shaped by research on a related effort that involved six large urban districts and took place from 2011 to 2016 (RFP; interview, May 16, 2023). Some key elements of the theory of change reflected in the data we studied include:

1. Districts’ actions to prepare and support equity-centered leaders need to be aligned into a coherent principal pipeline;

2. Leader standards adopted by the districts are foundational for this alignment;

3. The districts’ work proceeds in sequential steps, which include conducting an assessment, identifying gaps, making a plan of action, and continuously reflecting on the plan; and

4. Collaboration with university, state, and community partners is essential for the success of the work.

The scope template that was shared with grantees in Year 1 reflects this theory of change as well. The main activities in which the district-based teams were expected to engage included:

1. Develop and sustain deep partnerships,

2. Engage in visioning and strategic planning,

3. Define “equity” and “equity-centered leaders,”

4. Design and implement an “equity-centered principal pipeline,” and

5. Engage in continuous improvement (Scope Template, July 2021).

The grant-related documents illustrate the foundation’s theory “that achieving equity requires a systematic, coherent, and systemic approach to improvement” (RFP, p. 4). This emphasis on continuous improvement informed the approach that the district-based teams took to designing and implementing school leader pathways. In CCS, it strengthened equity-focused continuous improvement work that was already underway.

1.2 The grant initiative and Columbus City Schools

The aim of the grant initiative was to support districts in building “a comprehensive, fully aligned principal pipeline and other supports that produces equity-centered leaders” (The Wallace Foundation, Success of the Initiative). The Wallace Foundation defines principal pipelines in terms of seven broad areas of work, or domains: (1) leader standards, (2) high-quality pre-service principal preparation, (3) selective hiring and placement, (4) evaluation and support, (5) principal supervisors, (6) leader tracking system, and (7) systems and sustainability (Turnbull et al., 2021). The expectation of the foundation was that districts would anchor their work across the “pipeline” domains in district-specific definitions of equity and local leader standards that describe equity-centered school leader competencies and practices (ibid.). The foundation expected that work across the domains would proceed simultaneously and would involve a range of key partners (universities, community partners, and state agencies) (interview, May 16, 2023).

The work in CCS reflected this expectation. In the first three and a half years of the initiative, the district made substantive changes to its practices related to all domains. In this paper, we focus on one particular aspect of work: principal professional learning. This area spans two of the domains in the “pipeline” model: support/evaluation and principal supervisors. We focus on this work for two main reasons. First, it provides an opportunity for us to explore equity-focused continuous improvement. Second, considering one key aspect of the district work allows us to tease out how their design efforts both drew upon and changed an already existing, complex system of administrative support.

Our case study focuses on Columbus City Schools. CCS is one of eight districts that participated in the ECPI initiative, and the largest school district in the state of Ohio. The district serves around 45,000 students and has 114 schools. According to data from the Ohio Department of Education for the 2024 school year, more than half (51%) of the students identify as Black, 20% as white, and 18% as Hispanic or Latino. About 20% of students are designated as English Learners, 18% as students with disabilities, and 100% as economically disadvantaged. The average teaching experience of its staff is 15 years, and its teaching staff retention rate is 97%. Its graduation and attendance rate are 78% (Columbus City Schools, 2022a).

The continuous improvement work we highlight here is situated in the Office of Transformation and Leadership in CCS. The office was established in June of 2019, and was designed to provide an intentional focus on leadership development and support. The main responsibilities of the office included working with other CCS teams to develop, align, and deliver the high-quality supports needed to create a rigorous and joyous learning environment for the students that the district serves. The office prioritizes the work of school improvement; principal supervision, selection, and development.

The office houses six principal supervisors and six principal coaches, one for each of the six geographic regions in which CCS is divided. Principal supervisors and coaches work closely together to support school leaders. Principal coaches focus on aspiring and novice principals, who are in the first or second year of the principalship. Principal supervisors mainly support principals with 3–5 years of experience. In the rest of the paper, we refer to principal supervisors and coaches collectively as the principal support team. The team has shared goals and many shared practices, even if the extent of the use of continuous improvement across region-specific supervisor-coach pairs varies (we address this point in greater detail in section 4.4, which focuses on challenges to the use of continuous improvement). The team engages in regular calibration meetings to ensure that principals across the district receive similar types of support from their supervisor and coaches.

One of the reasons that we focus on the practices of the principal support team is that the team sees a direct link between their work and the improvements in student learning. In the past three years, the team focused on supporting students’ reading achievement and students’ scores surpassed the goal set by the district Board of Education. The Board introduced a math goal in 2023–2024, and the principal support team expects to see improvements in the 2024–2025 school year.

2 Literature review

Continuous improvement typically refers to “an interactive, data-based” cycle of collaborative inquiry (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019, p. 297). Continuous improvement is an umbrella term that encompasses a range of methods inspired by work in different fields, including industry, management, and design. Since the early 2010s, continuous improvement methods have become more widely used in education (e.g., Bryk et al., 2010; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020) and in leadership development in particular (Bryk, 2021; Datnow et al., 2017; Zumpe et al., 2024). Educators have used continuous improvement methods to bring about desired organizational change (Anderson and Davis, 2024), including systems change focused on equity (Bocala and Yurkofsky, 2024). The emerging literature on continuous improvement suggests that it has the potential to advance equity in schools, even as its power to transform oppressive systems is context-dependent and cannot be taken for granted (e.g., Anderson et al., 2023; Bush-Mecenas, 2022).

While continuous improvement approaches in education “range in their origin and theory of action,” they share a number of common commitments (Yurkofsky et al., 2020, p. 404). A key characteristic of school-focused continuous improvement is that it involves “learning through doing” (Bryk et al., 2010, p. 7), i.e., cycles of inquiry that are focused on defining a problem, designing and trying out new practices, and then sustaining practices that contribute to positive change (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020, p. 4). An important component of this process is the testing of change in different contexts, which provides insight on how local conditions shape the change and its outcomes (Bryk et al., 2015). Yurkofsky et al. (2020) identify the following four pillars of continuous improvement: “(1) grounding improvement efforts in local problems or needs; (2) empowering practitioners to take an active role in research and improvement; (3) engaging in iteration, which involves a cyclical process of action, assessment, reflection, and adjustment; and (4) striving to spur change across schools and systems, not just individual classrooms” (p. 404).

In recent years, a convergence of crises has increased the urgency of addressing systemic inequities and injustice in education. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the disproportionate negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the learning and wellbeing of students of color (e.g., Fahle et al., 2023) have made it imperative for school systems to place equity at the center of their improvement efforts. According to the National Equity Project, “educational equity means that each child receives what they need to develop to their full academic and social potential” (National Equity Project, n.d.). Recent research suggests that unless equity is explicitly infused in the improvement process, that process may not contribute to the design of more just education systems (Valdez et al., 2020). When educators leverage the mindsets, tools, and practices of continuous improvement to “interrupt, deconstruct and redesign organizational routines” that perpetuate injustice (Diamond and Gomez, 2023), however, educators can “surface and confront deep underlying issues of inequity” (Yurkofsky et al., 2020, p. 425).

It is this potential of continuous improvement to contribute to more equitable education systems that is at the core of our analysis. The focus on continuous improvement is consistent with the framing of the grant initiative that provided context for the work we document. We explore how changes in district culture and practices enabled district leaders to support principals in improving students’ educational experiences. We describe the continuous improvement process they used, and outline some of the challenges that arose. We conclude with a discussion of how this case study contributes to the field’s understanding of equity-focused continuous improvement.

3 Data collection and analysis

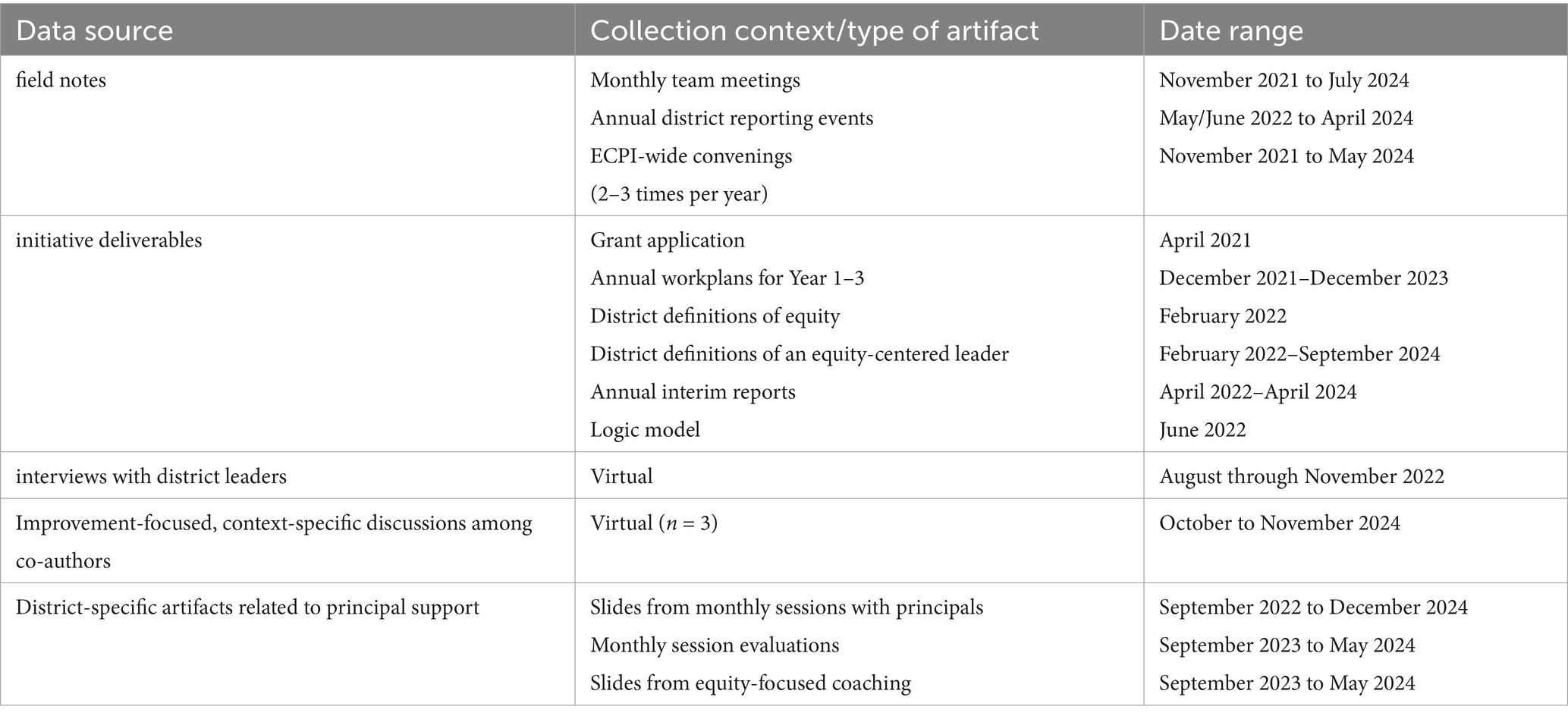

The analysis reported here is part of a larger research project. The data for the analysis are qualitative in nature. Table 1 provides a description of the data sources that informed the analysis. The findings reported here draw primarily on (a) field notes, (b) artifacts submitted to The Wallace Foundation, and (c) discussions among the co-authors (recorded and transcribed) that focused on continuous improvement in CCS. The data collection period spans three and a half years: from September 2021 to December 2024.

The data analysis was conducted in several phases. First, a team of graduate researchers affiliated with the larger project coded field notes, deliverables, and district leader interviews under the guidance of the first author and a lead graduate researcher. These data had been collected over three years. The coding was thematic and deductive in nature. The codebook contained codes that corresponded to the components of principal “pipelines” as described by The Wallace Foundation (e.g., Turnbull et al., 2021), and additional codes for equity, partnerships, and local context (for a list of the components, see the Context of the Grant section). The first author and lead graduate researcher frequently reviewed coded data and provided feedback to coders. The analysis team also engaged in regular calibration discussions that helped build shared understanding around the codes, refine the codes, and increase the consistency of the coding. The coding work was complete September 2024. This initial analysis helped familiarize the first author with the history of CCS’s approach to equity and its work related to leadership development in the first three years of the initiative. It informed the selection of the district as an illustrative case of the use of continuous improvement to advance equity.

Starting in October 2024, the co-authors began having discussions focused on continuous improvement in CCS and collecting relevant artifacts. A total of three one-hour conversations took place, which were recorded and transcribed. The purpose of the discussions was to foster shared understanding among the co-authors of how the principal support team leveraged continuous improvement in the service of equity. The first author analyzed the transcripts and artifacts for social conditions that enabled the continuous improvement process, examples of continuous improvement, and factors that hindered the process. The first author discussed all emerging insights with the other authors and made revisions accordingly. The authors determined together what artifacts to use to illustrate the equity-focused continuous improvement process in CCS.

The authors of this paper include practitioners as well as researchers. The first author is the research director of a research project funded by The Wallace Foundation as part of the ECPI. The second author is the district leader of the ECPI in CCS. The third and fourth authors are a CCS principal coach and principal supervisor, respectively. The fifth author is the lead principal investigator on the research project.

4 Findings

We begin this section by describing the theory of action that grounded the work of the Office of Transformation and Leadership in CCS. We then discuss the social conditions that made it possible for the office to engage in continuous improvement and make equity the center of the process (research question #1). We illustrate what the improvement process looked like with respect to supporting current school principals (research question #2). Finally, we highlight some of the forces that represented hindrances to the continuous improvement process in CCS (research question #3).

4.1 Problem identification, district vision, and theory of action

Most continuous improvement processes begin with problem identification (e.g., Bryk et al., 2010). In CCS, the problem was related to building school-leader capacity to lead for equity. This problem was informed by the district’s commitment to strengthening student achievement in reading and mathematics, and increasing high-school graduation rates. This commitment was codified in the three student outcome goals of the CCS Board of Education. The district’s commitment to improving student learning was also visible in its 5-year strategic plan, adopted in February 2022. The plan’s first objective was to ensure that “students are taught and learn from a guaranteed and viable curriculum delivered by highly-skilled teachers” (Columbus City Schools, 2022b). Importantly, the plan also embraced the process of continuous improvement as a key lever to achieve these objectives: “Strategy #5: Create a continuous improvement process to support the capacity of district departments to improve equitable outcomes, including the equitable allocation of resources to sustain those outcomes”.

While the Board goals related to gains in student achievement grounded the work of the principal support team, they served as a foundational aspiration only. The team’s vision for expanding principals’ capacity to lead for equity extended beyond these goals and towards the CCS equity definition. This definition states:

Educational equity means that each student has access to the resources, opportunities, and supports they need to develop to their full academic and social-emotional potential. Additionally, it involves ensuring that all employees feel valued and can maximize their full potential as professionals. In order to achieve educational equity, we must make the necessary system changes (policies, processes, and practices) to reduce and eliminate outcome predictability for any CCS student or employee based on any social identity factors, including but not limited to race, sex, gender identity/expression, socio-economic status, ability, and any intersections thereof (Columbus City Schools, n.d.).

Reducing and eliminating the predictability of student learning outcomes by race and socioeconomic status is at the core of equity efforts nationwide (e.g., National Equity Project, n.d.). This broader equity-focused goal guided the work of the principal support team, and shaped the long-term impact they hoped to see.

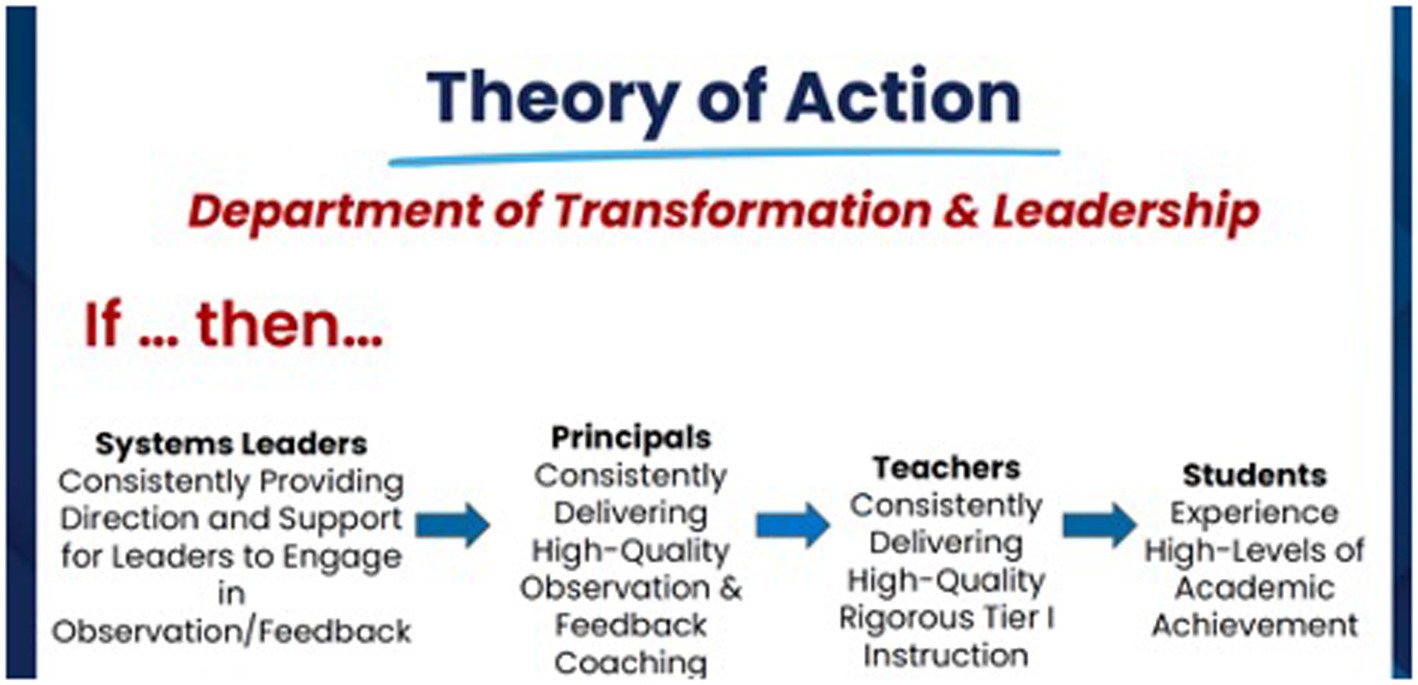

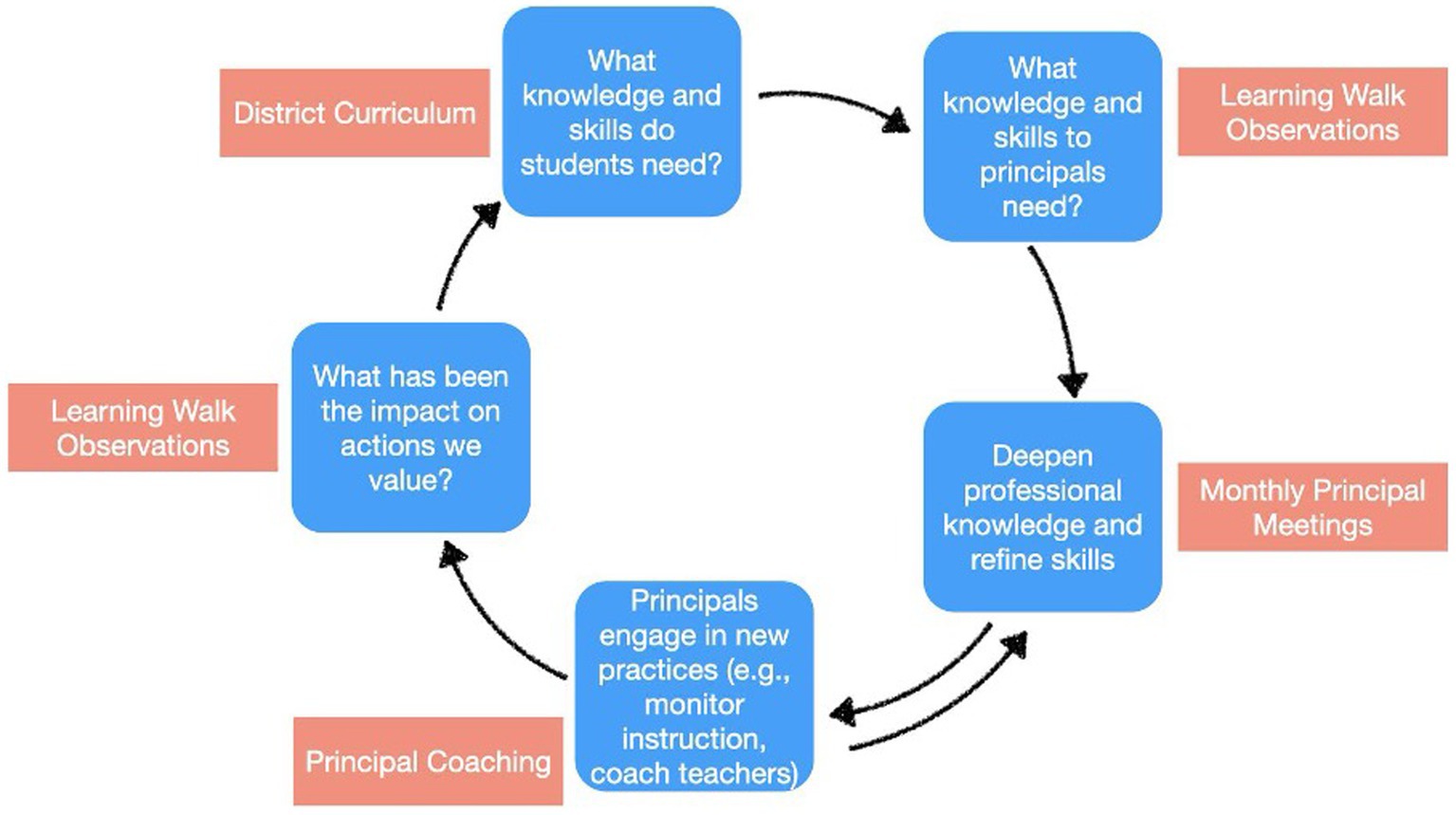

In the Office of Transformation and Leadership, the district’s commitment to improving student learning translated into an emphasis on expanding principals’ capacity to serve as instructional leaders. This focus was championed by senior district staff and supported by emerging research on the role of the principal in increasing student achievement and teacher retention (Gates et al., 2019; Grissom et al., 2021). District leaders drew a direct connection between the principal learning and student learning. This connection is illustrated in the theory of action of the principal support team (Figure 1).

Building a robust infrastructure for fostering the professional growth of principals became a goal of senior district leaders in 2019 and 2020. This priority overlapped considerably with the emphasis of the ECPI. In its application to the ECPI, the district described its goals for principal development in these terms: “CCS will strengthen its system of school visits and elevate its protocols … to further incorporate equity-centered and deeper learning/leading. Principal support will be strategically designed using learning core to all, common to many, and unique to some” (ECPI Application, April 15, 2021).

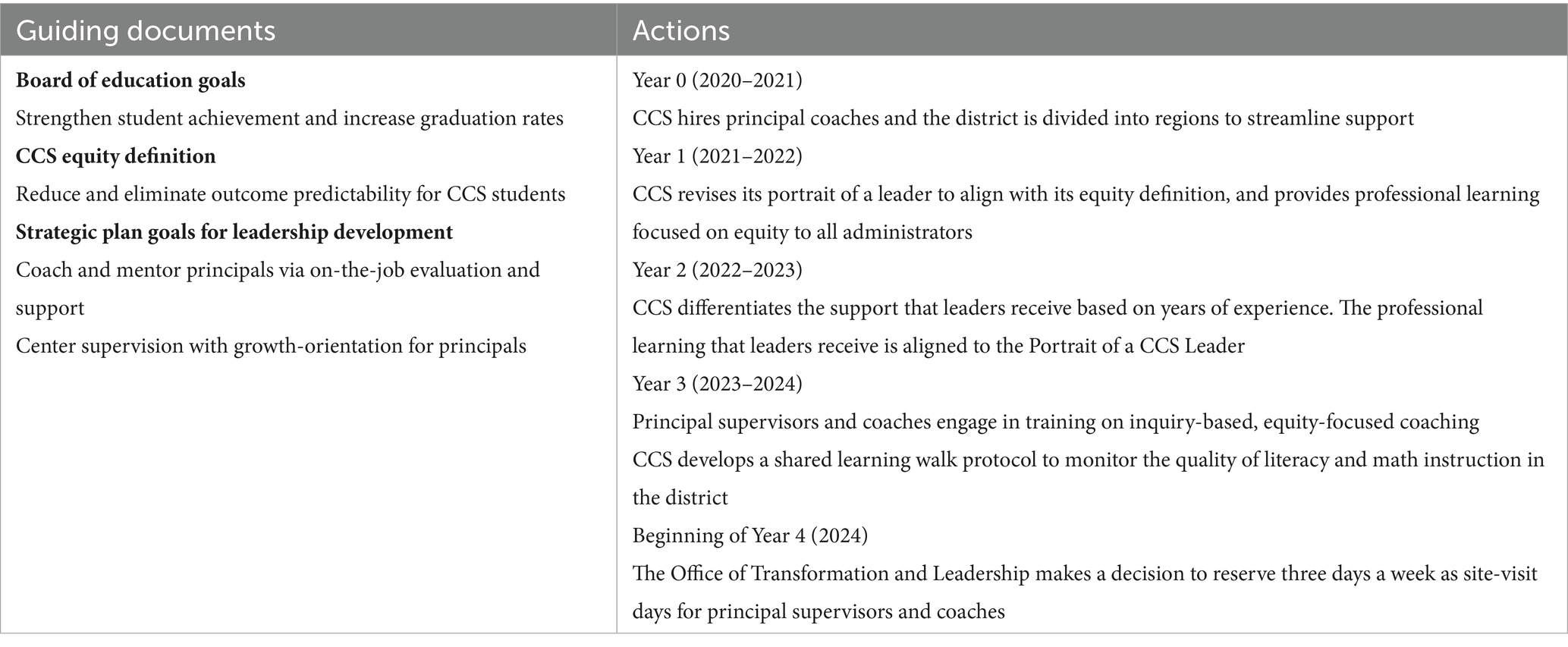

The district took a wide range of actions to address its central problem and move towards its vision of providing high-quality support for school principals (see Table 2). Initially, the district expanded the personnel available to support leaders. Then, the team focused on infusing a focus on equity in leader professional learning and meeting the different needs of principals. In the third year of the grant, the actions included expanding the capacity of principal supervisors and coaches to provide effective support to school leaders. The district strengthened this capacity by increasing the time available to the principal support team to observe and engage with principals, and deepening the team’s coaching skills.

4.2 Establishing social conditions to support equity-focused continuous improvement

In this section, we describe the social conditions that enabled the principal support team to engage in an equity-focused continuous improvement process to support school leaders. We identified three key conditions: (1) support from the top to focus on equity, (2) establishment of a culture of learning; and (3) collaboration with external partners.

4.2.1 Building a shared commitment and language around equity

Even before receiving the ECPI grant, CCS was invested in advancing equity in its schools. Beginning in 2019, senior leaders in the district (including the superintendent) embraced equity explicitly. District leaders introduced a mindset that centered historically underserved students and their school experiences. They also created urgency around improving student learning and wellbeing.

The district culture of equity that began emerging prior to the grant initiative was reinforced through steps that senior leaders took to integrate equity into district priorities and structures. For example, in 2020 the district established a department of equity. The superintendent supported the crafting of an equity policy, which was adopted by the School Board in 2022 (year 1 of the grant initiative). In addition, the district hired principal supervisors that had a track record of advancing equity in schools. Some of these supervisors were hired from within CCS, while others came from other districts. Equity as a priority was thus visible through the district organization, policies that guided its actions, and the personnel hired to work towards these policies.

Educators can espouse different approaches to equity depending on their experiences of the education systems where they work (e.g., Cobb, 2017). These differences are both natural and consequential in that they shape how people think and act (e.g., Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021). As part of their efforts to promote a common commitment and language around equity, senior district leaders in CCS focused on creating opportunities for shared sensemaking across departments.

The principal support team’s “level-setting” around equity-centered leadership had two key components: teamwide professional learning and the development of an artifact that describes equity-centered leadership in the context of CCS. The professional learning lasted a week and was facilitated by an external organization. It took place during the second year of the grant (2022–2023). During the professional learning, the principal support team explored their own mindsets about equity and equitable practices in schools. The team also had the opportunity to formulate equity-focused problems of practice. The professional learning opportunity reinforced the district-wide commitment to equity, and helped principal supervisors and coaches experience what integrating this commitment into their everyday work with school leaders might look like.

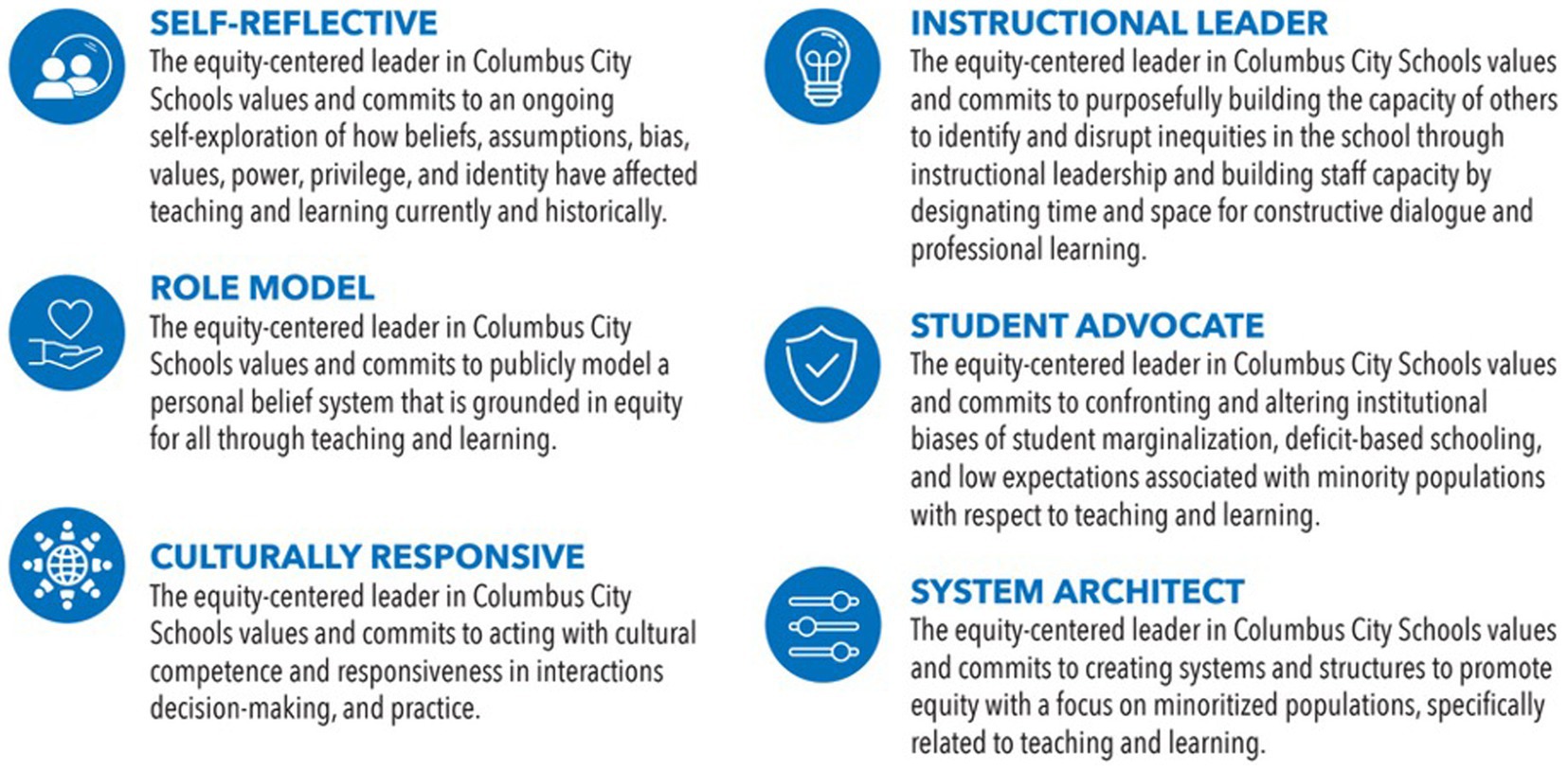

In addition to engaging in equity-focused learning together, the principal support team built shared understanding of what equity-centered leadership means in Columbus City Schools by developing a Portrait of an Equity-Focused Leader. A version of the portrait had been crafted prior to the grant initiative but was then refined to align with the district’s equity definition (Eslinger, 2023). The portrait includes six dispositions (see Figure 2).

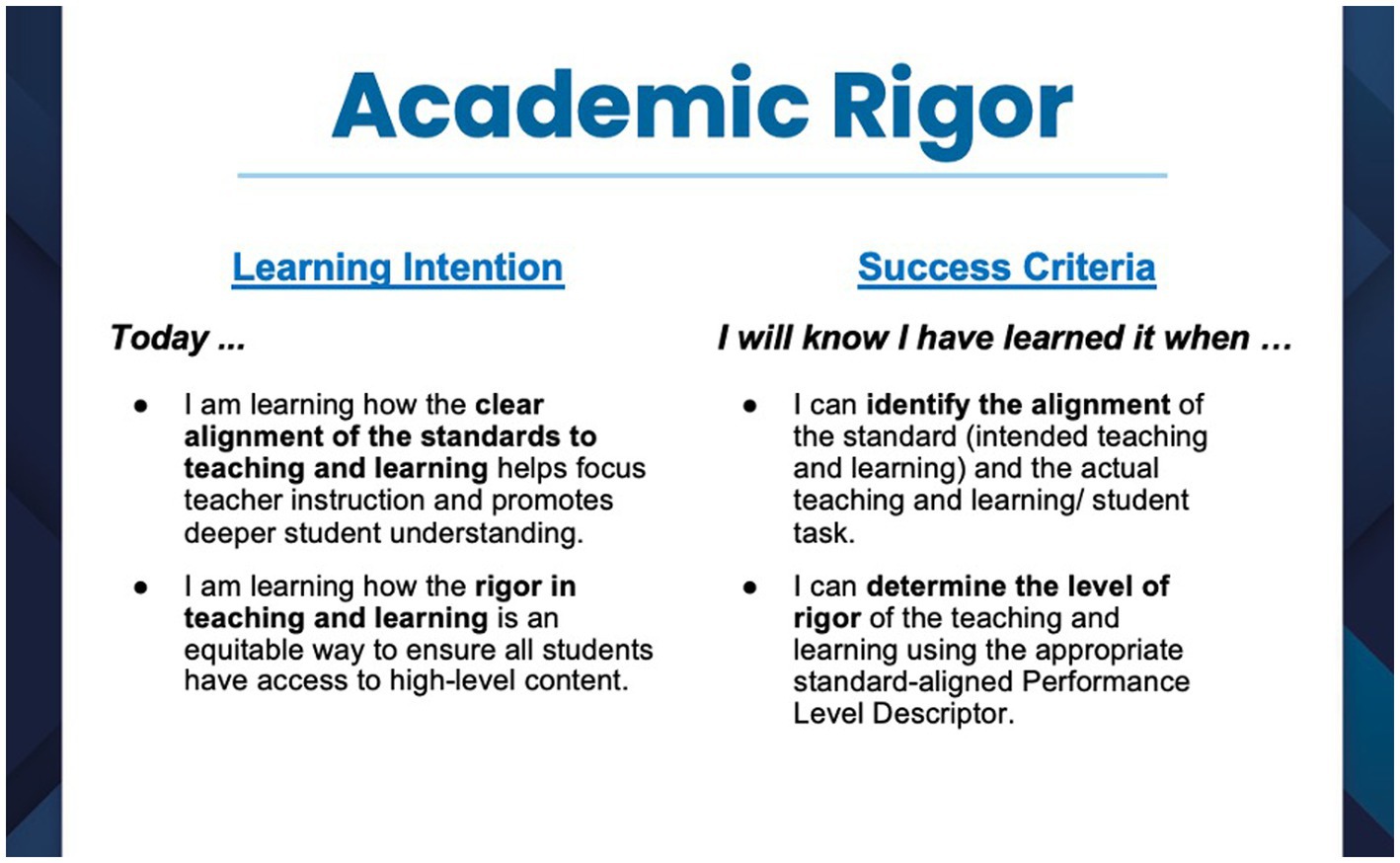

The portrait enabled the principal support team to ground their thinking and work in a shared description of equity-centered school leadership, and use consistent language to describe equity-centered leadership practices. The “instructional leader” disposition was particularly central to the team’s work, since it was seen as directly related to the district’s Board of Education goals. The team began incorporating the portrait in all their meetings. In addition, the professional learning for school leaders that the team designed was also explicitly grounded in the portrait (see Figure 3).

The commitment to equity informed the work of the principal support team, but it was made possible through a district-wide emphasis on advancing equity in schools. The team had support “from the top” to center equity in their work. This emphasis guided the continuous improvement process that they engaged in, and its focus on ensuring that all students have access to rigorous and engaging grade-level learning.

4.2.2 Establishing a culture of learning

A major goal for the CCS team during the first three years of the grant initiative was to gradually establish a culture of learning within the district. This culture became evident and sustained through practices that built the capacity of district and school leaders to lead for equity. As we illustrate in the Continuous Improvement section below, several newly developed practices helped to create the capacity that the principal support team needed to engage in equity-focused continuous improvement related to school leader support.

An example of the culture of learning was the transformation in the district’s approach to principal professional growth. The district’s efforts encompassed changes in personnel as well as practices. In 2020, the district hired principal coaches to increase its capacity to provide job-embedded, individualized support to principals. In addition, the district transformed the professional learning opportunities for school leaders. Prior to the onset of the grant, teachers and school leaders participated in the same professional learning sessions. These sessions were typically focused on new instructional or assessment resources that the district was rolling out. In the first three years of the initiative, however, the principal support team established practices for providing professional learning for principals only. This shift enabled closer alignment between the responsibilities of school leaders and the professional learning they engaged in. The professional learning focused primarily on building leaders’ capacity to do three things: understand what the use of district curricula and other resources should look like, monitor the use of these resources by teachers, and provide coaching and other support to teachers to ensure equitable student access to high-quality instruction (see Figure 4).

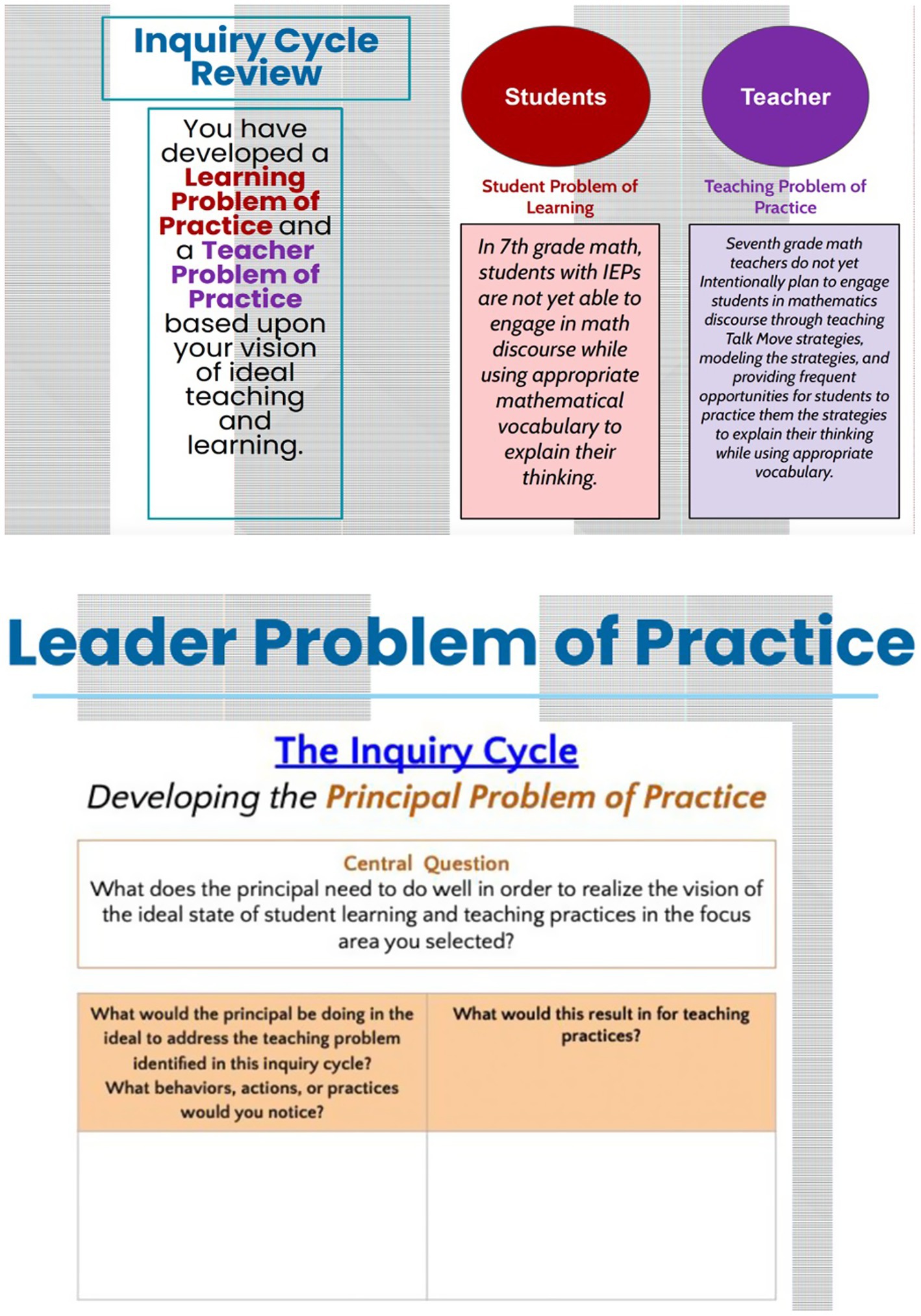

Figure 4. Developing a principal problem of practice based on observation and inquiry into teacher practice and student learning.

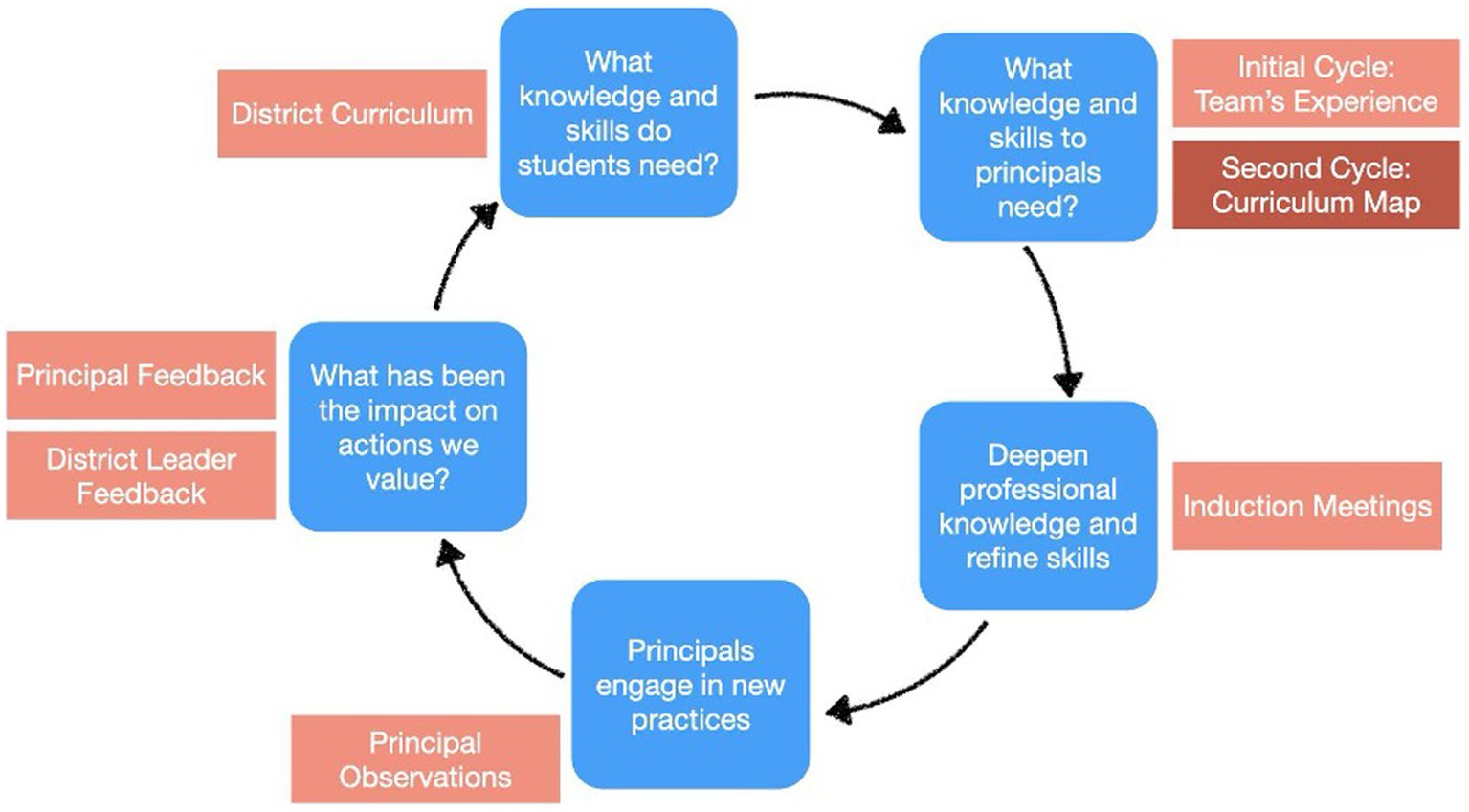

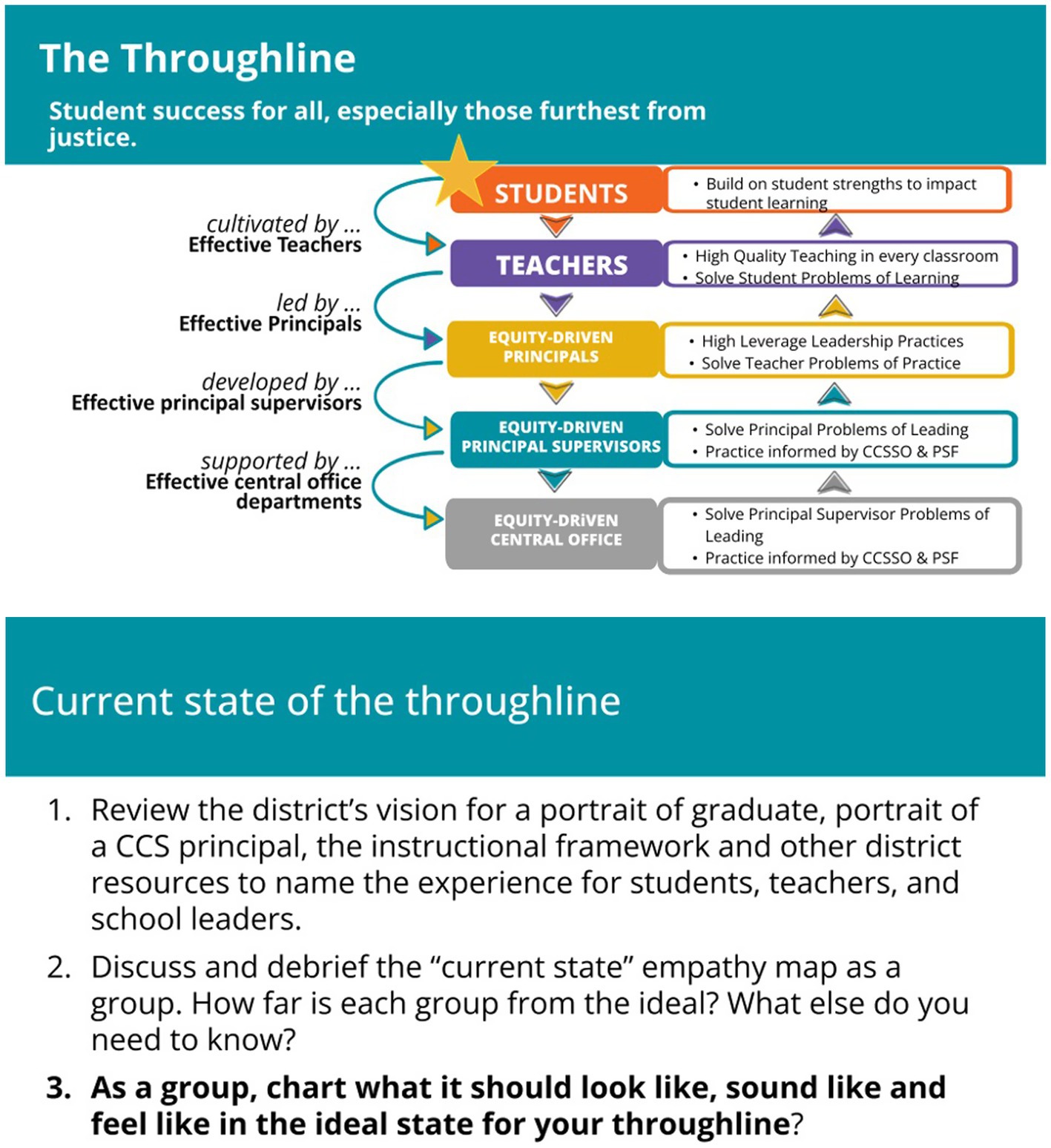

The culture of learning extended to the professional growth of principal supervisors and coaches. Similar to the transformation in school leader professional learning, the changes in professional development opportunities for the principal support team encompassed both additional opportunities for growth and logistical changes. The team engaged in a year-long professional learning on inquiry-based equity-focused coaching. The purpose of the training was to increase the team’s capacity to coach principals with a focus on equity. Even though the learning was provided by a university partner, it was still anchored in the equity priorities of CCS and its vision for an equity-centered leader (see second slide in Figure 5). According to the Year 3 progress report that CCS submitted to the grant foundation, this learning opportunity “dramatically influenced the work of the team… We are embracing the ‘throughline’ and it is changing our accountability mindset positively” (January 12, 2024). This throughline described the relationship between the actions of district staff and student learning and was a key idea from the equity-focused coaching training. As the first slide in Figure 5 illustrates, the district viewed the connection between central office staff practices and student outcomes as indirect and two-way. The actions of district staff impacted student learning through the practices of principals and teachers. In addition, student outcomes informed the work of principal supervisors and other district staff.

Figure 5. Equity-focused coaching slides: reflecting on the throughline from students to central office staff.

CCS also made changes to the work schedule of the principal support team in order to ensure that they had frequent opportunities to provide coaching to school leaders. Senior district leaders supported a move to set aside three days a week in which no district meetings could be scheduled with principal supervisors and coaches. The rationale for this change was that shifts in practice require consistent, job-embedded support that necessitates regular interaction between school and district leaders. This shift took place in the summer of 2024 and had a dramatic effect on how principals supervisors and coaches spent their time.

The continuous improvement process that is the focus of this paper, and which we describe in the Continuous Improvement section, would not have been possible without the learning culture of the district. If the district had not prioritized the learning of principal coaches and supervisors, the team would not have had the capacity in terms of either time or skill to offer job-embedded, individualized support to school leaders. It is this support, however, that the team credits to the success that CCS has experienced in meeting some of its student achievement goals.

4.2.3 Partnerships with external organizations

A third social condition that supported the principal support team’s use of equity-centered continuous improvement was the formation of partnerships. The Wallace ECPI theory of action emphasized the role of building connections with external organizations as a condition of creating responsive, impactful, and sustained leadership development programs (see Context of the Grant Initiative section). At CCS, three organizations in particular were instrumental in guiding the work in CCS and enabling the principal support team to provide equity-focused professional learning to school leaders.

The first organization was a non-profit with headquarters in New York City, USA that specializes in equity-focused professional learning for school leaders. Senior district leaders approached this organization to support the calibration of the principal support team around equity. The weeklong professional learning that the organization facilitated took place in the year before the grant initiative.

The second key partnership was related to building the capacity of the principal support team to coach for equity. This partnership was with a public university in another state. The university provided equity-focused coaching training during the third year of the grant initiative (2023–2024). University staff facilitated professional learning sessions and traveled to Columbus to observe the principal support team in action and offer feedback. This partnership represented a significant financial investment on the part of the district and would not have been possible without grant funding.

The third partnership was with a university located in Columbus. Each district involved in the grant was required to name two institutes of higher education as partners in its application to the initiative. This university is one of the formal partners for the grant, though the collaboration between the university and the district predates the grant initiative by several years. In the third year of the grant initiative (2023–2024), this partnership helped CCS meet one of its main goals related to leader growth: to offer differentiated learning opportunities to principals. University faculty provided equity-focused professional learning to a group of school leaders that the district had identified as needing additional support: middle school principals and members of their school leadership teams. In addition, university faculty engaged the principals in one of the CCS regions in professional learning related to culturally responsive leadership. This learning opportunity will be expanded to the other regions in the current academic year. The funding from the grant supported these professional development opportunities, and strengthened the partnership that already existed between the university and the district.

The district relied on non-profit as well as university partners to expand its capacity to provide equity-focused professional learning to school leaders. The growth of the principal support team involved building shared understanding of equity and equity-focused leadership in general as well as in the specific context of CCS. The district leveraged both internal funds and funds from the grant initiative to support the culture of learning to which it was committed.

4.3 Continuous improvement for school leader support

The social conditions described in the previous section enabled and empowered the principal support team to engage in continuous improvement in the service of equity. As we highlighted earlier (see the Context of the Grant Initiative and Problem Identification sections), continuous improvement was a key lever of change in the district strategic plan and was promoted by the funding agency for the grant. The partnerships that the district leveraged built the principal support team’s capacity to engage in equity-centered inquiry. The emphasis on growth in the district supported the team in adopting an inquiry stance to the design of equity-centered principal learning as well as the content of that learning (see Figure 4).

In this section, we illustrate how the continuous improvement process informed the equity-center professional learning that the principal support team made available to school leaders. We provide two examples as illustrations. The first is the design of professional learning for principles with three or more years of experience. The second example is the design of an induction program for novice principals (i.e., principals new to the district).

Our analysis is grounded in continuous improvement processes advanced in the research literature. Our description of the continuous improvement process in CCS addresses the six core principles of continuous improvement as defined Herman et al. (2024). They include: (a) developing an understanding of the problem; (b) identifying a specific aim; (c) describing the factors and conditions needed to accomplish the aim (a theory of practice improvement); (d) selecting strategies to achieve the aim; (e) conducting disciplined inquiry cycles; and (f) using data and measurement throughout the process. We address each of these principles in turn.

4.3.1 Developing an understanding of the problem and identifying a specific aim

Both examples we showcase were practices that reflected the principal support team’s theory of action (see Figure 1). As we described earlier, the team’s improvement work was grounded in a research-informed vision about the role of the principal in student learning. This theory of action encompassed both the problem-setting. The aim of the principal support team’s work was to provide high-quality support to school leaders, so that these leaders could ensure that all children in their schools had access to rigorous learning opportunities.

4.3.2 Describing the factors and conditions needed

The factors and conditions that the principal support team needed to engage in continuous improvement include the focus on equity across the district and the culture of learning (see the Social Conditions section). The district assembled a team of qualified individuals committed to equity who would design and provide professional learning to principals. Their work was anchored in a shared vision for equity-centered leadership in CCS. This vision was articulated in the portrait of an equity-centered leader (see Figure 2), which was developed very early on in the initiative. Finally, the team was committed to providing professional learning that was specifically tailored to the practices and responsibilities of school leaders.

4.3.3 Selecting strategies to achieve the aim

The principal support team employed a number of strategies to accomplish its aim of providing high-quality support for principals (see Table 2). These strategies were coherent and aligned both to the district’s equity vision and for its vision for high-quality professional learning for school leaders. First, the team engaged in professional learning to build a shared definition of equity. Second, the team began designing differentiated learning experiences for CCS principals depending on their levels of experience. Third, the team expanded their capacity to support school leaders through inquiry-based, equity-focused coaching. Fourth, the team developed a shared tool to collect data on the quality of classroom instruction in CCS schools. The tool was a learning walk protocol and was developed in the third year of the grant (2023–2024). According to the CCS workplan for Year 3 of the grant, the main purpose of the learning walk protocol was “to monitor instructional strategies and plan professional development based on trends and needs” (October 31, 2023). Fifth, the district set aside three days a week for principal supervisors and coaches to visit schools; no district meetings could be scheduled with the principal support team during that time. This change shifted substantially how the principal support team spent their time on a daily basis.

4.3.4 Conducting inquiry cycles and using data

The principal support team used inquiry cycles in its continuous improvement work for both experienced and novice principals. The inquiry cycles involve the use of data, so we address both the “conduct disciplined inquiry cycles” principle and the “use data and measurement throughout the process” principle of continuous improvement together (Herman et al., 2024, p. 5). Figure 6 illustrates one of the cycles. Our representation of the cycles is based on the inquiry professional learning cycle as described by Timperley (2011). The blue rectangles represent the stages in the inquiry cycle, and the orange rectangles describe the source of the data used (e.g., the principal support team used the district curriculum to determine what knowledge and skills students needed to develop) or the context in which a stage took place (e.g., monthly principal support or induction meetings).

The first inquiry cycle we explore was used to design, facilitate, and refine the professional learning available to principals with three or more years of experience in CCS (see Figure 6).

The inquiry cycle that the principal support team in CCS currently uses to support experienced school leaders begins with data on student learning in CCS schools. The principal support team conducts school visits of all principals, and employs the learning walk protocol to document the instruction they observe. The team then uses this school-based evidence to identify areas in which principals need support. The team designs monthly learning opportunities for principals to deepen their knowledge and refine their skills.

The design process takes into consideration both the team’s observations in schools and the ideas and preferences of school leaders. The team utilizes an established infrastructure to engage school leaders in new learning: monthly meetings for the principals of each region. Principals have an opportunity to put the new learning in practice between monthly sessions, and bring evidence of the practices they used with teachers to the following meeting. The principal support team continues conducting learning walks with principals, and observing both the principals’ work with teachers and the instruction that happens in schools. When they identify individual needs, the team provide additional weekly coaching to school leaders that need more support. The relationship between observation and support is therefore iterative, and for some school leaders may involve multiple cycles (hence the two arrows between these two areas in Figure 6). The principal support team continues conducting monthly learning walks to investigate the impact of the learning that they have provided to school leaders. Once they feel that certain desired shifts have happened in the schools, the team transitions to a new area of focus and the cycle repeats. Sample areas of focus have included increasing the rigor of math instruction in high schools and decreasing the number of chronically absent students.

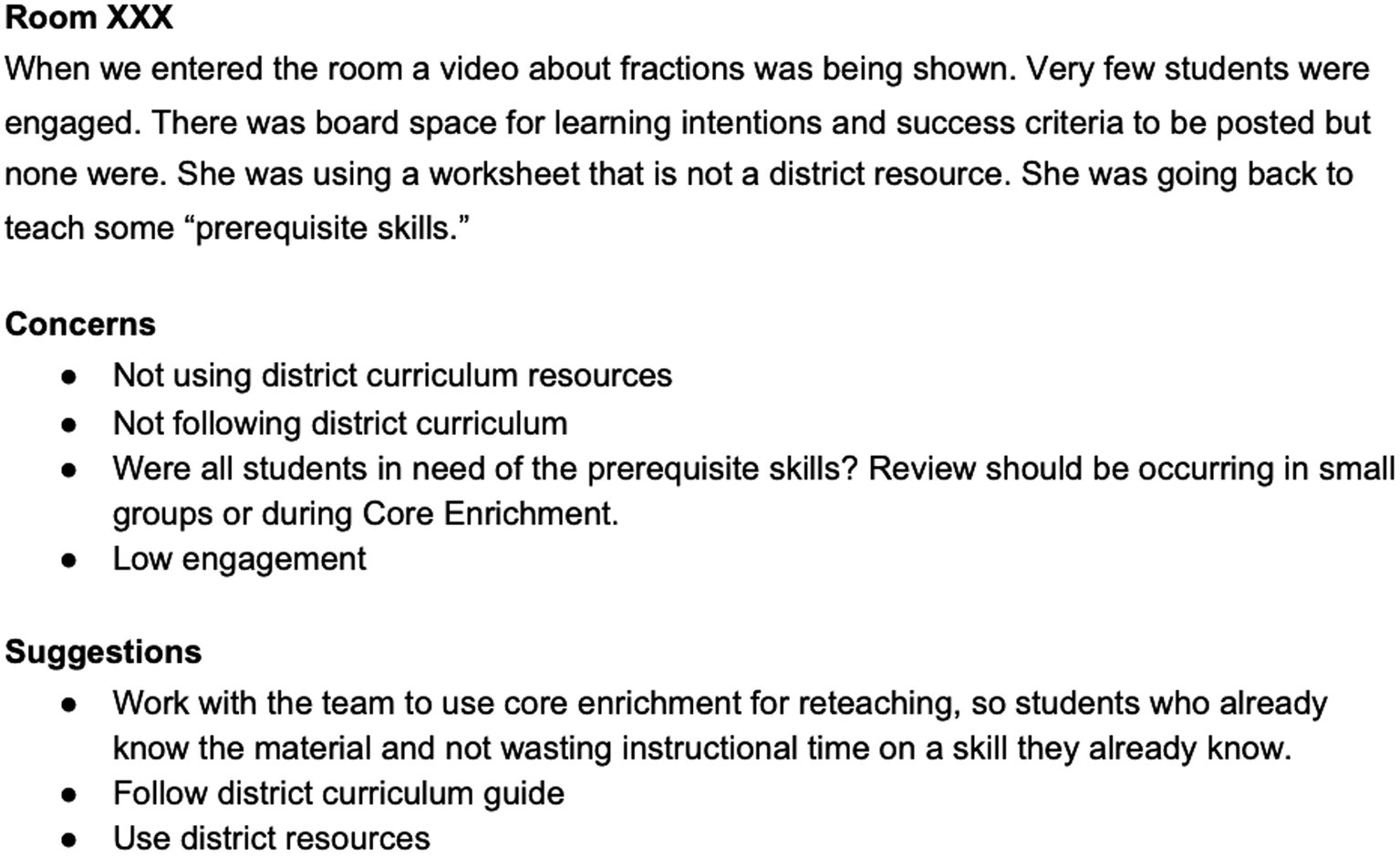

Figures 7–9 provides an illustration of this process. A principal supervisor and coach visited three classrooms in a middle school. As we discussed, these visits have become routine in CCS and are guided by a learning walk protocol used across the district. The team wrote up their observations and shared them with the principal (Figure 7). They were concerned about two things in particular: lack of rigor and lack of high-level questioning during mathematics instruction (Figure 8). As a result of these observations, the team decided to dedicate two monthly professional learning sessions to these topics (Figure 9). After the sessions, principals will be expected to visit classrooms and record higher level questions they hear teachers asking students. At a following monthly meeting, the whole group would discuss the feedback that principals provided to teachers on increasing the rigor of their mathematics instruction.

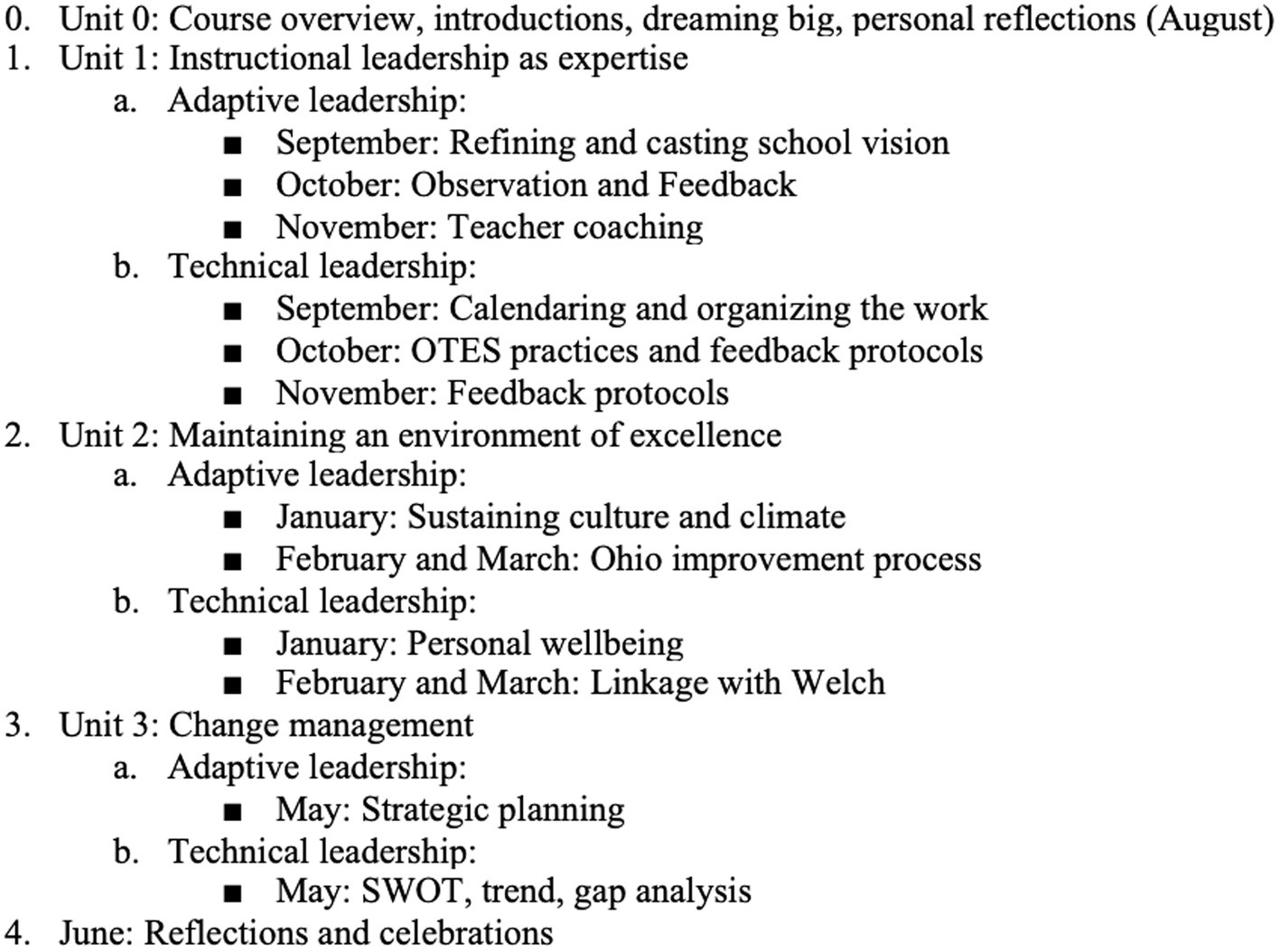

The second illustrative example of the use of continuous improvement by the principal support team is the team’s approach to designing learning for novice principals. The team refers to this support as induction. Induction is a two-year process that consists of monthly group meetings with the principal coach as well as weekly individual meetings with the coach for additional support. First- and second-year principals form separate cohorts (Eslinger, 2023) (assistant principals also receive induction support in their own cohorts). The induction support focuses on how to be an effective principal, how to be a principal in CCS in particular, and how to lead for equity in a school. The program launched in August 2020.

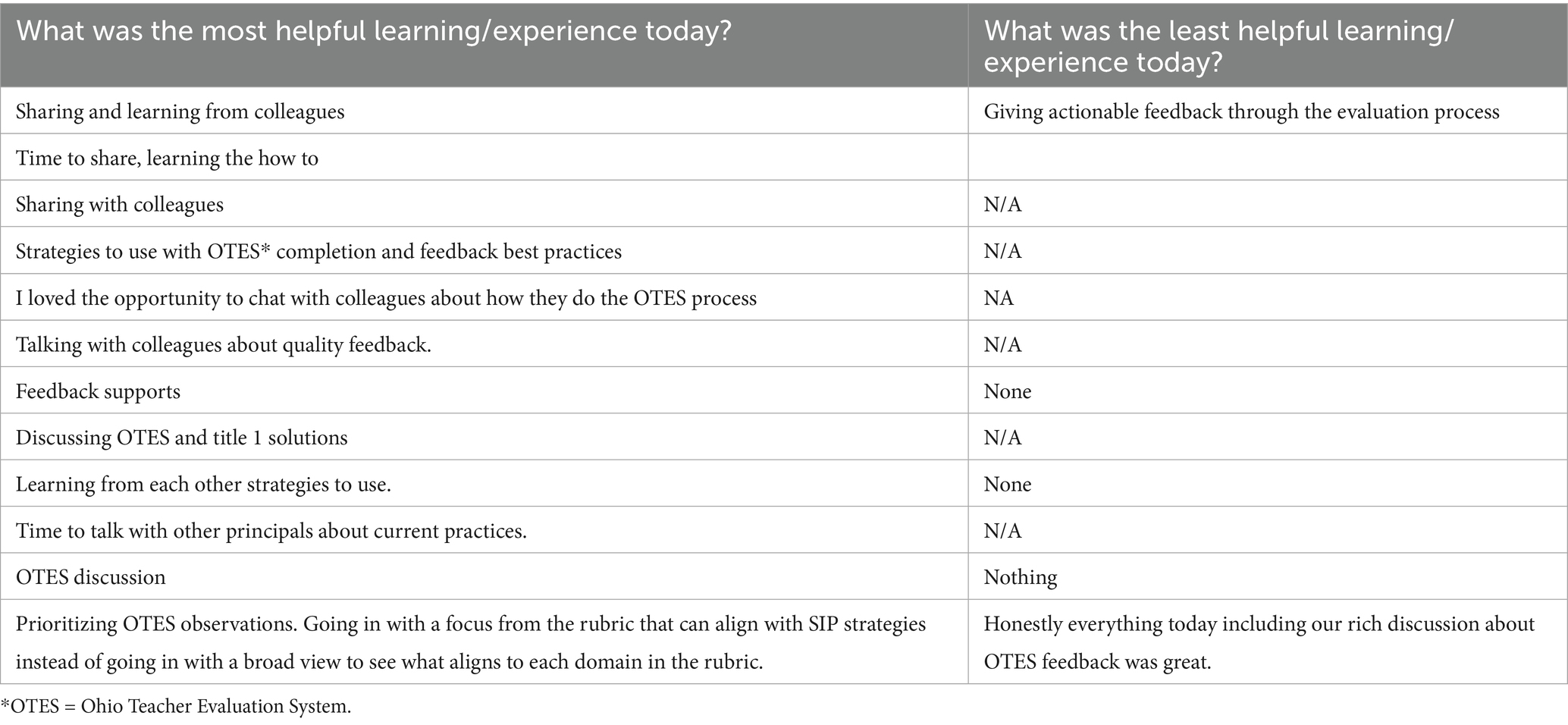

The inquiry cycle in which the team engaged is illustrated in Figure 10. The goal of the program was to provide novice principals with the support they needed to not just survive but to thrive. Initially, the program addressed a wide range of topics, many of which were technical in nature and focused on “administrative effectiveness, including operations, personnel and human resources, regulations and compliance, time management, and district deadlines” (Eslinger, 2023, p. 4). At the end of the first year, the team collected three types of relevant evidence: observations of principals, feedback from principals, and input from other district leaders.

The team collected school leader feedback through surveys after each monthly session. This feedback indicated that leading for change was difficult. The school leaders greatly valued the time spent together discussing leadership practices with colleagues, and wanted more time to process as a group challenges they were encountering (see Table 3).

Observations of novice leaders by the principal support team indicated that principals struggled with practicing adaptive leadership and strategically planning for improvement. The team decided that the principals would benefit from more intentional support in putting together leadership teams, exploring school data, formulating problems of practice, and shifting existing practices. Finally, feedback from other district leaders pushed the principal design team to align the induction program more closely with the district’s equity vision and its portrait of an equity-centered leader. The team developed a map for principal growth over the two years of the program and a curriculum that followed that map (see Figure 11). The map and curriculum brought more intentionality and greater alignment to the professional learning that the novice leaders experience. This scope and sequence has become the foundation for the induction program going forward.

In this section, we have illustrated how the principal support team used continuous improvement to provide high-quality professional learning opportunities to school principals. The two examples we highlight are by no means the only ones. We use them as illustrations of the central role of continuous improvement in the team’s approach to school leader support. In both cases, the team incorporated principal voice and observations of principal and teacher practice in its design of professional learning.

4.4 Factors that hindered equity-focused continuous improvement

In our analysis of continuous improvement in the Office of Transformation and Learning in CCS, two factors emerged as obstacles to equity-focused continuous improvement in CCS: the absence of specific guidance on continuous improvement and the emerging nature of the collaboration among principal supervisors, coaches, and school leaders across the six regions of the district.

Despite the commitment to continuous improvement in the district strategic plan and the grant initiative, the principal support team did not receive specific guidance on how to engage in a continuous improvement process. This meant that the engagement in continuous improvement practices was organic and depended on the experience and habits of mind of specific principal supervisors and coaches. The examples we provide come from the work of the principal support team in one of the district’s regions. Not all of these practices were used by the principal support teams in the other regions. The use of the practices of continuous improvement across the district would be strengthened if the district adopted continuous improvement as a model for its work. Formal continuous improvement infrastructure would ensure that the practices we describe continue even if there is turnover among the current principal supervisor and coaches in the region we highlight. Such infrastructure would also help continuous improvement practices become shared across regions. Continuous improvement infrastructure would strengthen the culture of learning within the district’s principal support team and promote the continued building of shared understanding around what equity-caused leadership entails in Columbus, and how it can be measured and strengthened.

The second hindrance to the continuous improvement process is the sheer size of the district. Columbus is a large district that serves racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse communities. The size and diversity of the district add complexity to its work of supporting schools. In 2019, the district was divided into six regions to increase its capacity to meet schools’ specific needs: “Each region was provided a robust team of individuals from various academic and operations departments. This strategy required the realignment of central office supports in a way that each region had access to support from across the district. Network supports extended the district’s ability to provide intense and differentiated support to all schools” (ECPI Application, April 15, 2021). Though this strategy was informed by a needs analysis and is viewed in the district as successful, it gave rise to internal divisions that need to be continuously breached. Such divisions create an environment in which excellence can exist in pockets. The two professional learning opportunities that senior district leadership created for the principal support team (building a shared understanding of equity and expanding the team’s capacity to coach for equity) were intended specifically to counteract this process. Such efforts continue.

The challenges described here are not unique to CCS but exemplify hurdles to continuous improvement that have been identified in the literature. Valdez et al. (2020), for instance, highlight that “limited access to professional learning opportunities” related to continuous improvement and “systems [that] may not be designed or organized to support improvement efforts” (p. 16) represent obstacles to continuous improvement. In the case of CCS, these hindrances did not prevent the principal support team from engaging in equity-focused continuous improvement. Instead, they served as obstacles to ensuring that every member of the team engaged in such practices.

5 Discussion and implications

Our exploration of equity-focused continuous improvement in Columbus City Schools offers important insights for other districts that are or may want to become engaged in such efforts. It also helps broaden the field’s understanding of what an equity-centered continuous improvement process may look like in the context of a school district, what factors could facilitate it, and what outcomes it might contribute to.

The first implication of our analysis has to do with the nature of the continuous improvement process itself. In the case of CCS, the process did not begin with the identification of a shared problem. Instead, it was anchored in a clear equity vision and goals related to student learning. It is important to note that this vision was informed by the literature on the impact of school leadership on students and staff (e.g., Gates et al., 2019; Grissom et al., 2021). The goal of the continuous improvement process in CCS was to provide principals with effective support that would expand their capacity to lead for equity. The shared equity vision, reflected in artifacts such as the district’s portrait of an equity-centered leader, was sufficient to bring coherence and a shared language to the work of the principal support team. This work might have unfolded differently had it begun with a collective and disciplined effort to identify a shared problem. The difference between a problem and a goal can also be a difference in framing: the CCS goal of expanding school leaders’ capacity to lead for equity could also be stated as a problem of inadequate leadership for equity. The efforts of the principal support team in CCS illustrate that continuous improvement can be impactful and take many forms. With respect to equity-focused continuous improvement, having a clearly articulated and shared vision for equity-centered practice seems paramount.

Another distinctive feature of the continuous improvement process in CCS was that the principal support team prioritized equity not only in terms of outcomes but also in terms of process. The culture of learning promoted relationships of trust between supervisors, coaches, and school leaders. The team focused on fostering growth rather than apportioning blame. School leaders whose practices did not meet the team’s expectations received additional coaching support rather than being dismissed. Such a cultural shift is essential when it comes to leadership for equity. Equity work is notoriously difficult (Irby, 2022; Diamond and Lewis, 2019), and it takes trust: “establishing trust increases the likelihood that individuals will take risks, and it increases the likelihood that reform initiatives will diffuse broadly” (Valdez et al., 2020, p. 14). The inquiry cycle that the team embedded in its coaching support contributed to this trust. As Timperley (2011) points out, inquiry requires relationships of “respect and challenge.” She identifies three practices related to building such relationships: (a) demonstrating that everyone has the capacity to learn and grow; (b) challenging each other’s assumptions, and (c) refraining from playing “blame games” and at the same time accepting responsibility for what is within our sphere of control (p. 42). A defining feature of the culture of learning in CCS was the belief that all leaders can learn and grow. In addition, the focus on equity required challenging conversations with school leaders. These conversations were not only inevitable but also welcome and expected in the district. The principal support team had received explicit training in facilitating such discussions. The team’s coaching also consistently encouraged leaders to focus on the factors that were within their control. Through the coaching process, principals formulated equity-focused problems of practice and theories of action that helped guide the actions they took to improve the conditions of teaching and learning in their schools.

The equity-focused continuous improvement work in CCS suggests that it requires both support from the top and the grassroots. Senior district leadership, including the superintendent, was unapologetic about the urgency of having equity guide the work of the district. This focus continued even when the superintendent changed and was replaced by the former Chief of Schools in the district. The clear message that equity was a district priority gave all district staff permission to foreground it in their own work. This emphasis led to opportunities for building shared understanding as well as capacity around equity-centered leadership. It also guided hiring decisions that ensured that the district equity officer, principal supervisors, and principal coaches had the necessary experience as well as mindsets. The superintendent was able to build a team of competent and committed individuals that were ready and able to use equity as a foundation for their work.

Our analysis suggests that one possible definition of equity-centered continuous improvement is a process that aims to move an organization towards its equity priorities through equity-focused practices. In the case of CCS, the organization was the district and the priorities were articulated in its equity definition: “reduce and eliminate outcome predictability of any CCS student or employee based on any social identity factors” (Columbus City Schools, n.d.). The district had a clear theory of action that was informed by current research and connected the work of the principal support team to student learning (e.g., Gates et al., 2019; Grissom et al., 2021). Importantly, the district leveraged a continuous improvement process that had equity at the center and promoted relations of trust and respect. It was not sufficient for the continuous improvement process itself to be focused on equity. It was also important that the practices used to spur change – such as inquiry-focused coaching – promote growth, agency, and individual responsibility for improving the things we can control (Anderson et al., 2023; Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022). Equity, in other words, should guide both the what (the desired outcomes) and the how (the means we use to move towards these outcomes).

6 Conclusion and limitations

In this case study, we highlight the engagement of principal supervisors and coaches in continuous improvement for the purpose of advancing equity in schools. As all case studies, our work is deeply rooted in the specific context of Columbus City Schools: a large urban school district in the midwestern region of the United States. This paper offers a strong argument for districts to leverage continuous improvement in the development of the leaders responsible for principals’ learning. These district leaders need a shared understanding of equity and the capacity to provide job-embedded, growth-oriented, and equity-focused professional learning in order to design and facilitate learning experiences that expand principals’ use of equity-centered practices in schools. In addition, these district leaders’ engagement in continuous improvement can help ensure that the support they provide is responsive, relevant, and effective.

The paper also has limitations that we would like to highlight. Within the timeframe of the study, we were unable to collect data from the principals who were being supported by the district team. Such data would shed light on the strengths and growth edges of the learning opportunities that the team was providing and the use of continuous improvement to design these opportunities. Second, the data we highlight reflects the work of the principal supervisors and coaches in one of the regions in Columbus City Schools. In future research, we would like to have the opportunity to explore in greater depth how continuous improvement practices are being used by supervisors and coaches in the other regions. Such data would have enabled us to offer a more encompassing analysis of the use of equity-centered continuous improvement across the district.

Data availability statement

The datasets used in this article are not readily available. Per the study’s protocol, approved by University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, raw data can only be accessed by the research team.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JE: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. DA: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. RH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted with financial support by The Wallace Foundation (Grant ID#: 20210283).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank The Wallace Foundation for its financial support of the Equity Centered Pipeline Initiative and this research. We want to express our gratitude to Louis Gomez, a member of our project’s larger research team, for his invaluable guidance on continuous improvement. We greatly appreciate the generosity of the reviewers who helped us strengthen this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, E., Cunningham, K., and Eddy-Spicer, D. (2023). “Enacting leadership through continuous improvement” in Leading continuous improvement in schools: Enacting leadership standards to advance educational quality and equity. eds. E. Anderson, K. Cunningham, and D. Eddy-Spicer (New York: Routledge).

Anderson, E., and Davis, S. (2024). Coaching for equity-oriented continuous improvement: facilitating change. J. Educ. Chang. 25, 341–368. doi: 10.1007/s10833-023-09494-6

Bevan, B., and Penuel, W. R. (2018). Connecting research and practice for educational improvement: Ethical and equitable approaches. London: Routledge.

Bocala, C., and Yurkofsky, M. (2024). Continuous improvement and the “wicked” problems of racial inequity. J. Educ. Change. 1–28. doi: 10.1007/s10833-024-09520-1

Bryk, A. S. (2021). Improvement in action: Advancing quality in America’s schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., and Grunow, A. (2010). Getting ideas into action: Building networked improvement communities in education. Stanford, CA: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Available online at: http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/spotlight/webinar-bryk-gomez-building-networked-improvement-communities-in-education [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., and LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bush-Mecenas, S. (2022). “The business of teaching and learning”: institutionalizing equity in educational organizations through continuous improvement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 59, 461–499. doi: 10.3102/00028312221074404

Cobb, J. S. (2017). Inequality frames: how teachers inhabit color-blind ideology. Sociol. Educ. 90, 315–332. doi: 10.1177/0038040717739612

Columbus City Schools. (2022a). CCS at a glance. Available online at: https://www.ccsoh.us/cms/lib/OH01913306/Centricity/Domain/4/CCS%20At%20A%20Glance%20Web.pdf [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Columbus City Schools. (2022b). CCS strategic plan: the power of one. Available online at: https://www.ccsoh.us/page/11181 [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Columbus City Schools. (n.d.) Department of Equity. Available online at: https://www.ccsoh.us/equity [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Datnow, A., Greene, J. C., and Gannon-Slater, N. (2017). Data use for equity: implications for teaching, leadership, and policy. J. Educ. Adm. 55, 354–360. doi: 10.1108/JEA-04-2017-0040

Diamond, J. B., and Gomez, L. M. (2023). Disrupting white supremacy and anti-black racism in educational organizations. Educ. Res. 1–9. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231161054

Diamond, J. B., and Lewis, A. E. (2019). Race and discipline at a racially mixed high school: Status, capital, and the practice of organizational routines. Urban Educ. 54, 831–859. doi: 10.1177/0042085918814581

Eddy-Spicer, D., and Gomez, L. (2022). “Accomplishing meaningful equity” in The foundational handbook on improvement research in education. eds. D. Peurach, J. Russell, L. Cohen-Vogel, and W. Penuel (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield), 81–110.

Eslinger, J. (2023). Equity-centered school leaders. Phi Delta Kappan. 105, 20–25. doi: 10.1177/00317217231219400

Fahle, E., Kane, T., Patterson, T., Reardon, S., Staiger, D., and Stuart, E. (2023). School district and community factors associated with learning loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Recovery Scorecard Project. Available online at: https://cepr.harvard.edu/education-recovery-scorecard. [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Gates, S., Baird, M., Master, B., and Chavez-Herrerias, E. (2019). Principal pipelines: A feasible, affordable, and effective way for districts to improve schools. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Grissom, J., Egalite, A., and Lindsay, C. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. Available online at: http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Herman, R., et al. (2024). Evaluation of the networks for school improvement initiative—Networks and intermediaries: Interim report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA242-1.html [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Hinnant-Crawford, B. N. (2020). Improvement science in education: A primer. Gorham, ME: Myers Education Press.

Irby, D. J. (2022). Stuck improving: Racial equity and school leadership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Ishimaru, A. M., and Galloway, M. K. (2021). Hearts and minds first: institutional logics in pursuit of educational equity. Educ. Adm. Q. 57, 470–502. doi: 10.1177/0013161X20947459

Mintrop, R., and Zumpe, E. (2019). Solving real-life problems of practice and education leaders’ school improvement mind-set. Am. J. Educ. 125, 295–344. doi: 10.1086/702733

National Equity Project. (n.d.). Educational equity definition. Available online at: https://www.nationalequityproject.org/education-equity-definition [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Timperley, H. S. (2011). Realizing the power of professional learning. New York: Open University Press.

Turnbull, B., Worley, S., and Palmer, S.. (2021). Strong pipelines, strong principals: A guide for leveraging federal sources to fund principal pipelines. Washington, DC: Policy studies associates, education counsel. Available online at: https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/strong-pipelines-strong-principals-a-guide-for-leveraging-federal-sources-to-fund-principal-pipelines.aspx [Accessed December 12, 2024].

Valdez, A., Takahashi, S., Krausen, K., Bowman, A., and Gurrola, E.. (2020). Getting better at getting more equitable: Opportunities and barriers for using continuous improvement to advance educational equity. San Francisco, CA: WestEd. Available online at: https://www.wested.org/resource/getting-better-getting-more-equitable/ [Accessed: 4 November 2024].

Yurkofsky, M. M., Peterson, A. J., Mehta, J. D., Horwitz-Willis, R., and Frumin, K. M. (2020). Research on continuous improvement: exploring the complexities of managing educational change. Rev. Res. Educ. 44, 403–433. doi: 10.3102/0091732X20907363

Keywords: leadership, continuous improvement, district, case study, equity

Citation: Molle D, Sebenoler M, Eslinger JC, Agnes D and Halverson R (2025) Infusing equity in continuous improvement: supporting equity-focused leadership development in Columbus City Schools. Front. Educ. 10:1545785. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1545785

Edited by:

Erin Anderson, University of Denver, United StatesReviewed by:

Kathleen M. W. Cunningham, University of South Carolina, United StatesAnna E. Premo, ETH Zürich, Switzerland

Copyright © 2025 Molle, Sebenoler, Eslinger, Agnes and Halverson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniella Molle, ZGFuaWVsbGEubW9sbGVAd2lzYy5lZHU=

Daniella Molle

Daniella Molle Mickie Sebenoler2

Mickie Sebenoler2 James C. Eslinger

James C. Eslinger