- 1Faculty of Humanities and Teacher Education, Volda University College, Volda, Norway

- 2Faculty of Social and Educational Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

Researchers and scholars of teacher education have sought to explain the conceptions of teachers’ professional development (TPD) through their empirical and seminal works. To contribute to the knowledge base of multiple actors’ conceptions of TPD, this qualitative study investigated lower-secondary school teachers’, principals’ and university-based teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD when teachers participated in professional development interventions. The professional development intervention was a process for the implementation of a decentralized policy in Norway. Data was collected by conducting four focus group interviews with 19 lower-secondary school teachers and 14 individual interviews with seven principals of lower-secondary schools and seven university-based teacher educators from a local university/university college in western Norway. The data was analyzed by using the constant comparative method. The findings show that the participants in the study discerned some shared and some distinct conceptions of TPD. In the shared conceptions of TPD, teachers, principals and university-based teacher educators emphasized the development of knowledge of ongoing education acts, policies and reform among teachers. The development of the knowledge of content and the knowledge of curriculum among teachers were also incorporated in their shared conceptions of TPD. However, in the distinct conceptions of TPD, teachers emphasized the development of their instructional practices and hands-on skills for teaching, and principals and university-based teacher-educators accentuated teachers’ engagement in reflection on practices and continuous learning throughout their teaching careers. The findings have implications for the revision of TPD policies that seek to improve teachers’, principals’ and university-based teacher educators’ professional development practices from their various professional positions. The findings also point to the need for policymakers to acknowledge teachers’, principals’ and university-based teacher educators’ conceptions as the foundation in the selection of TPD contents and processes while designing and implementing new professional development initiatives in the forthcoming educational reforms.

1 Introduction

Teaching is no longer the mere delivery of knowledge by teachers to passive groups of students in their classrooms (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz, 2015; Kennedy, 2016). Rather, teachers’ responsibilities extend to “the development of curriculum and assessment, decision-making about school policies and practices and the development and evaluation of teaching strategies” and demand teachers’ learning and development in the profession (Darling-Hammond, 1995, p. 22). Further, teachers’ learning and professional development are also associated with school improvements (Guskey, 2002) and educational reforms (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz, 2015; Borko, 2004; Desimone, 2009). Thus, teachers need continuous professional development (PD) throughout their teaching careers. This paper investigates the conceptions of teachers’ professional development held by teachers, principals and university-based teacher educators who are also the practitioners of teachers’ professional development.

Teachers’ professional development (TPD) are deliberate learning interventions to improve teachers’ instructional practices and students’ learning (Avalos, 2011; Guskey, 2002). Nevertheless, some scholars attribute significant attention to informal incidents like “meetings after school” (Timperley et al., 2007, p. xxiv) or conversations among fellow teachers in the “hallways” and “counseling a student” (Borko, 2004, p. 4) as the moments for teachers’ learning. In other words, TPD is the improvement of teachers’ content and pedagogic competencies (Guskey, 2003; Munday, 2005) through teachers’ individual and collective participation (Karlberg and Bezzina, 2022; Kvam, 2023).

Hashweh (2013) claims that TPD has undergone extreme changes from traditional top-down teacher training models to research-based professional learning communities since the 1970s. Newer conceptions of TPD emphasize teachers’ collective participation in school-based PD to develop a common vision of development among teachers and enhance reflection on practices during and after PD (Grau et al., 2017; Postholm, 2012; Sprott, 2019) rather than a mere personal and professional growth of an individual teacher (Desimone, 2009; Opfer and Pedder, 2011). Irrespective of the nature of the PD model, whether transmissive like teacher training, or transformative like collaborative professional inquiry, TPD seeks to support teachers in learning and fostering their instruction (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Kennedy, 2014; Kennedy, 2016; Opfer and Pedder, 2011). Nevertheless, what and how teachers learn from PD is highly influenced and determined by teachers’ individual instructional beliefs and practices, prior knowledge and experiences, and their school’s collective beliefs, access and support to professional learning (Opfer and Pedder, 2011).

For PD to have an impact on teachers and students, they ought to be effective or of high quality (Desimone, 2009). High-quality PD includes the features of content focus, active learning opportunities, collaboration, use of models and modeling, coaching and expert support, feedback and reflection and sustained duration (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017, p. 4). Postholm (2012) discloses that school-based PD opportunities following the whole-school approach and supported by the school administration benefit both teachers’ teaching and students’ learning. The structured nature of teachers’ learning acquired by participating in high-quality PD leads to changes in teachers’ beliefs and attitudes toward teaching and learning (Desimone, 2009; Grau et al., 2017; Guskey, 2002), enhancement of teachers’ knowledge and practices, and eventually improvements in students’ learning achievements (Borko, 2004; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Lay et al., 2020). Addition to mastery in teaching, teachers discern good classroom management abilities (Shulman, 1987). Studies also indicate that PD directs students’ learning towards progress (Wang and Wong, 2017; Yang et al., 2019). Desimone (2009) claims teachers’ social and emotional growth after their participation in high-quality PD. Overall, PD allows teachers to develop in the profession (Zhang, 2022).

Apparently, researchers have investigated different aspects of TPD. For example, in a systematic review, Avalos (2011) identified that teachers’ general professional learning, processes for PD, factors influencing PD and the impact of PD on teachers and students were the prominent themes of PD research. Highly cited research papers in TPD and teacher education, for example, Garet et al. (2001), Desimone (2009), and Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) demonstrated the core features of effective PD. There are also studies, for example, Kennedy (2016) and Sims and Fletcher-Wood (2021) that critique the effectiveness of PD in terms of their visible positive impact on students’ learning achievement although the core features of effective PD characterized the PD interventions. There is also a plethora of research literature on teachers’ experiences in TPD (e.g., Baustad and Bjørnestad, 2023; Chalmers, 2017; Guerrero-Hernández and Fernández-Ugalde, 2020; Hamilton et al., 2021; Mattheis et al., 2015; Mukrim, 2017; Polly, 2017; Sang et al., 2020; Wang and Wong, 2017; Yan and Yang, 2019). Studies have reported the development in teachers’ knowledge and their pedagogical practices in the classroom after they participated in PD (Birman et al., 2000; Chong and Pao, 2022; Hamilton et al., 2021; Nasri et al., 2023; Yan and Yang, 2019). Further, studies have also indicated reflection as an effective approach to TPD (Grau et al., 2017; Guerrero-Hernández and Fernández-Ugalde, 2020; Nasri et al., 2023; Postholm, 2016; Mukrim, 2017; Sang et al., 2020; Wang and Wong, 2017).

However, the study of educators’ conception and its application for TPD is less-researched (Varnava Marouchou, 2011). Studies indicate that educators’ conceptions of instruction and their instructional practices are related (Gamlem, 2015; Haynes-Brown, 2024; Maass, 2011; Varnava Marouchou, 2011). Educators’ conceptions are also the outcomes of their practices (Cobb et al., 1990; Guskey, 2002). The insights of the conceptions of TPD help to align PD with improved teaching practices (Kennedy, 2016; Zhang, 2022). Thus, this study aims to investigate lower-secondary school teachers’, principals’ and university-based teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD and attempts to fill the knowledge gap on educators’ conceptions of TPD in the literature. The study also contributes to knowledge on what and how teachers should learn for their contextually relevant PD in the present times. As Lay et al. (2020) argue, by investigating educators’ conceptions of TPD, this study also contributes to policy implications for designing more impactful PD that can transform their conceptions of PD and meet their needs in the forthcoming PD endeavors.

2 Conceptions of teacher knowledge and learning

Shulman (1986, 1987) conceptualizes, introduces, and discusses the fundamental components of knowledge for teachers’ learning. These seminal writings explicitly advocate the significance of knowledge and knowledge development among teachers for meaningful teaching and learning in schools. Shulman (1986, p. 9) posits content knowledge as the “missing paradigm” in teacher learning and discusses content knowledge, pedagogic content knowledge and curricular knowledge as the essential knowledge base for teachers.

Shulman (1987) proposes an extended list of teacher knowledge base with seven categories of knowledge and their illustrations the following year and asserts that the knowledge is indispensable for teachers to promote their students’ learning. The extended framework of teachers’ knowledge includes content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, curriculum knowledge, general pedagogic knowledge, knowledge of learners and their characteristics, knowledge of educational context and knowledge of educational ends, purposes and values and their philosophical and historical grounds. Hashweh (2013) explains that the seven categories of knowledge are conceptualized as individual knowledge categories for teachers rather than the sub-categories of content knowledge as discussed in Shulman’s (1986) framework. Fellow researchers have argued for the changes and revision of Shulman’s (1987) framework and proposed revised and extended models of the knowledge categories (e.g., Almeida et al., 2019; Seikkula-Leino et al., 2021). In later work, Shulman and Shulman (2004) have commented on the seven categories of the knowledge base that it is skewed to individual teachers and teacher’s cognitive dimension and proposed a comprehensive framework for conceptualizing contextual teacher learning and development as a community.

In the framework, Shulman and Shulman (2004) have proposed vision, motivation, understanding, practice, reflection and community as the essential features of teacher learning and development. They identify individual teachers as a member of a larger teacher community and state that skilled teachers have a vision of students learning and understanding, learning process and classroom. Such teachers are motivated to sustain their teaching to meet the vision. Likewise, teachers understand what to teach and how to teach. Teachers’ understanding includes, but is not limited to, disciplinary and interdisciplinary content knowledge, the knowledge of curriculum, classroom management and organization, assessment, broader understanding of accomplishment in the classroom, school, local community and in the professional and reform efforts and the understanding of the diverse aspects of their students. Further, teachers engage in reflection where they evaluate, review and criticize their practices and learn from their own and others’ experiences. These features define that individual teachers’ learning transforms into the shared vision, the shared knowledge, the community of practice and the shared commitments when teacher learning and development are conceptualized at the institutional level (Shulman and Shulman, 2004). Similarly, in Shulman and Shulman’s (2004) framework, the policy domain is the inseparable aspect of teacher learning. Shulman and Shulman (2004) assert that the resources for teacher learning are provided by policies, hence the implementation and sustainability of teacher learning efforts rely on reform policies. The developmental reforms receive resources in the form of “venture capital, curricular capital, cultural/moral capital and technical capital” (Shulman and Shulman, 2004, p. 267). Shulman and Shulman’s (2004) framework is used to generate a deeper understanding of teachers’, principals’, and university-based teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD in this paper. Nevertheless, the theoretical knowledge from Shulman (1986, 1987) is also used to better understand the elements of teacher knowledge.

The research question of the study is: How did lower-secondary school teachers, principals, and university-based teacher educators conceptualize teachers’ professional development?

3 Materials and methods

A qualitative approach was used by the researcher to generate a deeper understanding of lower-secondary school teachers’ (hereafter: teachers), principals’ and university-based teacher educators’ (hereafter: teacher educators) conceptions of TPD when they participated in university-school collaboration for TPD. A qualitative approach to an inquiry entails the collection of research data from research participants in a natural setting and the analysis of the data inductively and deductively (Creswell and Poth, 2018). This study implemented focus group and individual interviews for the collection of research data and the constant comparative method for the analysis of the data.

3.1 Context of the study

This study was conducted in a county in Norway. The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research (NMER) introduced a decentralized policy called ‘Decentralized competence development in the school’ (DeComp) in 2017 to improve students’ learning in schools by improving the quality of elementary (year 1–7), lower-secondary (year 8–10) and upper-secondary schools (year 11–13) through TPD. The implementation of the decentralized policy in one of the counties in western Norway is the context of the study. The geography of the county mostly includes fjords, islands and mountains. Thus, people live on the islands and coastal lowlands in small cities and villages. There are not many universities/university colleges (UC) in the county; however, there are schools both in the cities and the villages as per the county’s need.

According to the decentralized policy, the central Norwegian government provides state funds to counties and municipalities to conduct PD in the schools. Teachers’ learning and PD should be based on the Education Act and the ongoing curriculum for elementary, lower-secondary and upper-secondary schools and the core curriculum (NMER, 2017a). The municipalities are the owners of the public kindergartens, the public elementary and lower-secondary schools, and the counties are the owners of the upper-secondary schools in Norway (OECD, 2019). Both public and private schools in the counties and the municipalities receive 70% financing from the state government, and the rest of the 30% financing is provided by the respective municipalities that own the schools to implement PD in the schools according to the provisions of the decentralized policy (NMER, 2017b). The counties and the municipalities should collaborate with schools and local UC to select the PD themes that respond to their schools’ local needs (NMER, 2017b; OECD, 2019). The collaboration between schools and UC should be the main mechanism for sustainable TPD in the schools (NMER, 2017b). Further, the decentralized policy follows the collective PD model to respond to the local needs of the schools sustainably. Therefore, all teachers in the schools participate in the same PD interventions that are adapted to meet the needs of their school’s local contexts (OECD, 2019). The UC facilitates research-based TPD in the schools.

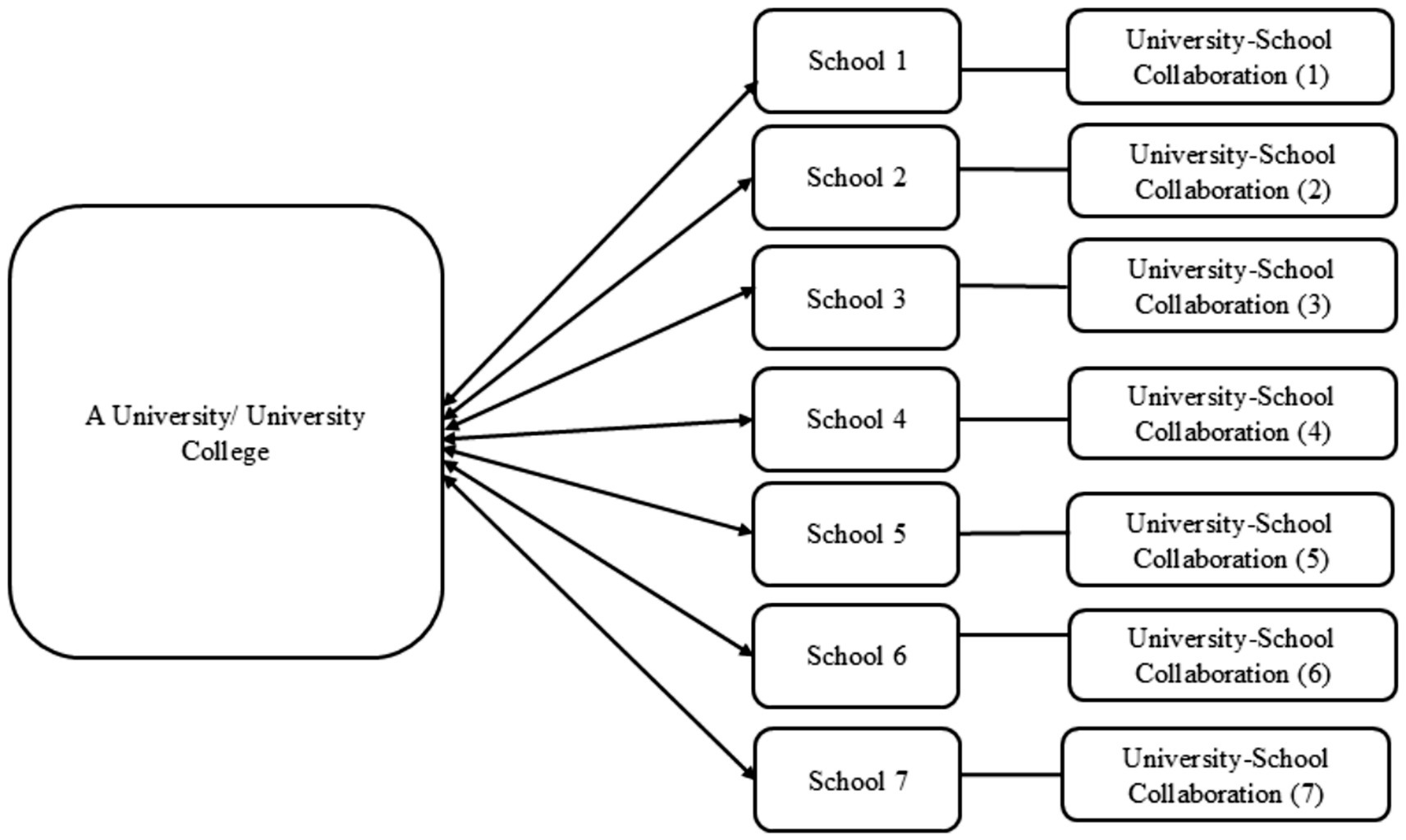

This study involved a local UC and seven lower-secondary schools representing rural, urban and public lower-secondary schools in the province. Each lower-secondary school collaborated with the UC for TPD in their schools forming seven different collaborative constellations (See Figure 1). Different TPD interventions were implemented in these schools. All the teachers in the lower-secondary schools participated in the same PD selected for their schools when the decentralized policy was implemented in the province.

3.2 Participants

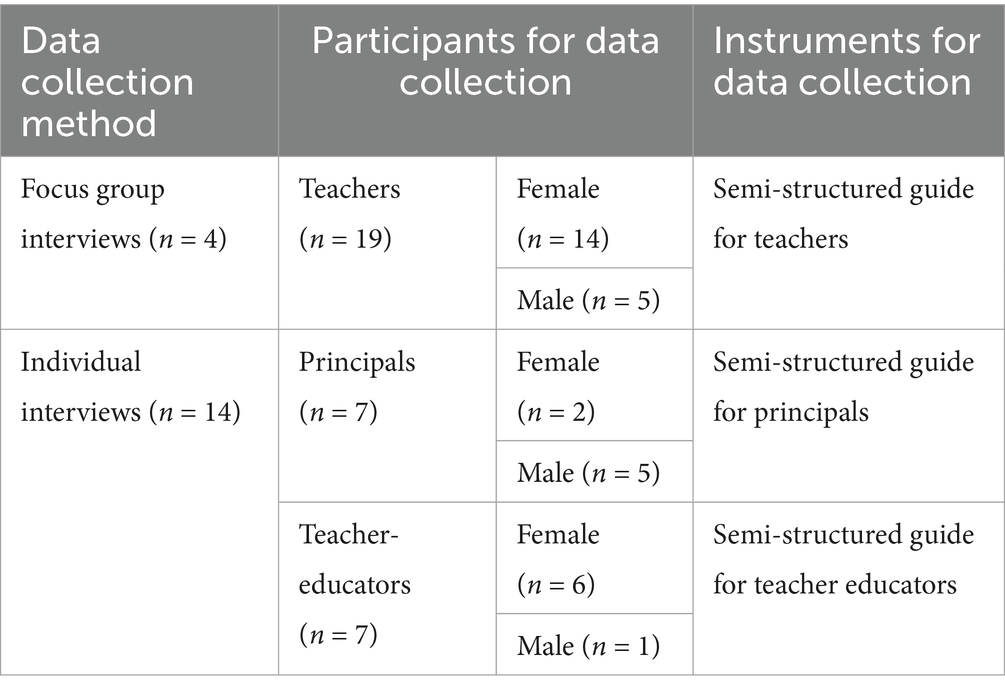

Nineteen teachers, seven principals and seven university-based teacher educators were the participants in the study (See Table 1). All the teachers teach at the lower-secondary level. The teachers belong to four lower-secondary schools, and they participated in the PD interventions when the decentralized policy was implemented. Among the seven principals, four of the principals were from the lower-secondary schools that also participated in the focus group interviews. Three principals from three other lower-secondary schools were recruited to increase principals’ participation in the study and also to better understand principals’ conceptions of TPD. All seven teacher educators belong to a local UC in the county. The teacher educators who facilitated PD to teachers in the lower-secondary schools and/or had administrative responsibilities for TPD when the decentralized policy was implemented were recruited in the study. Information about the participants is presented in Table 1.

The teachers, the principals, and the teacher educators were selected purposefully as the participants in the study. The researcher contacted the principals and teacher educators individually on the telephone, and the teachers were contacted through the principals. All the participants were native Norwegians and spoke Norwegian as their mother tongue. The purposeful selection of participants entails the selection of the “information-rich cases” that can illuminate the research question (Creswell and Poth, 2018; Knott et al., 2022; Patton, 1990, p. 170). The principals and the teachers in this study participated in the PD interventions as the participants and the teacher educators were the PD facilitators when the decentralized policy was implemented. Further, the principals had administrative responsibilities to conduct and implement PD in their schools. Since all the teachers, the principals and the teacher educators have engaged in PD interventions, or are the practitioners of TPD, they provided relevant and rich information to better understand the research issue of this study, that is, conceptions of TPD. All the lower-secondary schools included in the study were in a collaborative relationship with the UC. However, the duration of the university-school collaboration for TPD in the implementation of the decentralized policy varied. While some schools had collaborated with the UC for 6 months, some others had been in the collaborative relationship with the UC for 3 years at the time of data collection.

3.3 Instrument and piloting

Semi-structured interview guides were used by the researcher to collect data from teachers, principals and teacher educators in the study (See Appendix A). Interview guides help to ensure that the relevant issues are covered during interviews and the research participants are asked similar questions while also allowing adaptation of the questions (Patton, 1987). The researcher developed a separate semi-interview guide for teachers, principals and teacher-educators (See Table 1). All the semi-structured interview guides included 11 open-ended questions. The semi-structured interview guides included the questions asking for participants’ understanding and experiences (Patton, 1987). For example, the questions included the themes of participants’ understanding of TPD, experiences of TPD and experiences of university-school collaboration for TPD when the decentralized policy was implemented. Firstly, the researcher developed all the semi-structured interview guides in English, and then translated them into Norwegian to make them suitable for native speakers of Norwegian language.

As Creswell and Poth (2018) suggest, pilot interviews were conducted before the instruments were used for data collection to refine the questions and ensure that relevant questions were included in the semi-structured interview guides. A teacher and a principal participated in individual pilot interviews. Applying Creswell and Poth’s (2018) suggestion, the participants for instrument piloting were selected based on their engagement in the PD interventions when the decentralized policy was implemented, availability for the pilot interviews, and geographical convenience to visit them physically. The principal and the teacher provided feedback on the clarity of the questions for native Norwegian speakers. Then the questions in the semi-structured interview guides were refined according to their feedback to make them understandable and meaningful for teachers, principals and teacher educators with Norwegian mother tongue. For example, refining the interview questions involved using words that are familiar and relevant to native speakers of Norwegian language.

3.4 Data collection

Four focus group interviews and 14 individual interviews were conducted by the researcher for data collection in the study (See Table 1). Focus group interviews are useful qualitative data collection strategies to gather a large amount of data in a limited period of time (Morgan, 1997). Researchers have access to research participants’ insight through group interaction during focus group interviews (Ho, 2006). The focus group interviews were conducted with teachers from four lower-secondary schools. The focus group interviews were conducted in the four lower-secondary schools because the schools were participants in university-school collaboration for TPD when the decentralized policy was implemented. Further, the teachers in the schools participated in the PD interventions and volunteered to participate in focus group interviews. Three focus group interviews involved five teachers, and one focus group interview involved four teachers. Focus group interviews allow researchers to gather a range of information from both individual participants and the group involved in the interview (Morgan, 1996). Thus, the focus group interviews provided the opportunities to listen to and understand teacher’s individual conceptions of TPD and the conceptions held by the group of the teachers as they inquired each other and elaborated on their understanding to each other. Further, teachers had opportunities to articulate their responses of conceptions of TPD by building on each other’s responses when they answered the interview questions. The focus group interviews were conducted with teachers in their respective schools during their school-working-hours.

Fourteen individual interviews were conducted with seven principals and seven teacher educators. Individual interviews are useful strategies to gather in-depth information on the experiences and perspectives of the interviewees (Patton et al., 2015). Thus, as Knott et al. (2022) argue, the individual interviews were conducted to elicit principals’ and teacher educators’ deeper insights of their conceptions of TPD from their professional positions of school leadership and PD facilitators, respectively.

Both focus group and individual interviews were used in the study for data collection based on their strengths to result in rich data for the study. The decentralized policy demanded the participation of all teachers in the same PD in the participating schools for teachers’ collective PD (NMER, 2017b). Hence, as Morgan (1997) argue, focus group interviews were useful for gathering information on teachers’ experiences and perspectives of PD through group interaction since they participated in the same PD and could have a number of perspectives to share. Further, focus group interviews allowed to gather the information of the similarities and differences in teachers’ conceptions when they responded to the questions. Also, understanding how teacher groups conceptualized PD was more important in this study than understanding individual teachers’ conceptions of PD. However, individual interviews were conducted with principals and teacher educators to gather an in-depth understanding of their experiences and perspectives of TPD as the professionals with administrative responsibilities and the facilitators of PD, respectively. Since different schools participated in different PD interventions, principals and teacher educators were believed to have developed different experiences and perspectives of TPD based on their affiliations to different institutions with different professional responsibilities.

The focus group and the individual interviews were conducted in Norwegian. All the focus group and the individual interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed by using a software immediately after the interviews by the researcher. To ensure the accuracy of the software-transcribed transcriptions, the transcriptions were checked verbatim with the audio records by listening again by the researcher. While checking the transcriptions, the researcher inserted the missing texts and corrected the wrong transcriptions.

3.5 Data analysis

The constant comparative method (CCM) (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) was used by the researcher to analyze the data from teachers, principals and teacher educators to generate a deeper understanding of their conceptions of TPD after they participated in PD in university-school collaboration when the decentralized policy was implemented. The analytic procedures of open coding, axial coding and selective coding (Corbin and Strauss, 1990) were followed to analyze the focus group and the individual interview data to better understand teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD.

The data analysis began with the close reading of the interview transcriptions by the researcher (Creswell and Poth, 2018). All the interview transcriptions were read closely multiple times to understand the data. The reading of the interview transcriptions was conducted in an order. First, teachers’ transcriptions were read, then principals’ transcriptions were read, and at last, teacher educators’ transcriptions were read. Coding and categorization of the interview transcriptions during open and axial coding were conducted in the same order by the researcher; first teachers, then principals and lastly, teacher educators. Main categories were named during open coding (Creswell and Poth, 2018) by following an inductive approach where the codes were generated from teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ responses to the interview questions. Open coding was performed on the sentence level (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). However, when the participants’ responses were built on the responses of previous teachers or were the continuation of a teacher’s response during the focus group interviews, the whole answers were also coded during open coding. During axial coding, the categories that were generated in the open coding were studied thoroughly and the connections between the categories were sought to form the new categories (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). Further, in the axial coding stage, particular to this study, the examples and the incidents that the teachers, the principals, and the teacher educators shared and referred to as TPD were used in developing the new categories. Likewise, the examples and the incidents that the teachers, the principals, and the teacher educators acknowledged as non-learning incidents, or insignificant for teacher learning and TPD were also considered while developing the new categories. An example of category development is presented in Table 2 (See Appendix B). Finally, a core category called “multiple conceptions of teachers’ professional development,” was generated which addressed all the sub-categories and answered the research question. Since the transcriptions of the focus group and individual interview data were in Norwegian, the accuracy of the translation from Norwegian to English was ensured by three native Norwegian teacher educators and researchers who reviewed the translations.

3.6 Ethics

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. All the participants were provided with detailed information about the research and the purpose of the research before the focus group and the individual interviews orally and in writing by the researcher. All the participants signed a consent letter before the focus group and the individual interviews. Likewise, the participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that they would not face any negative consequences upon their withdrawal (National Research Ethics Committee, 2021). Similarly, as suggested by Creswell and Poth (2018), to hide the identity of the participants to protect them from harm upon identification, all the participants were given fictitious names (e.g., Teacher 1, Principal 1, Teacher Educator 1) while representing them in the texts. The names of the schools and the UC of their affiliation are not indicated in any form in the text.

4 Findings

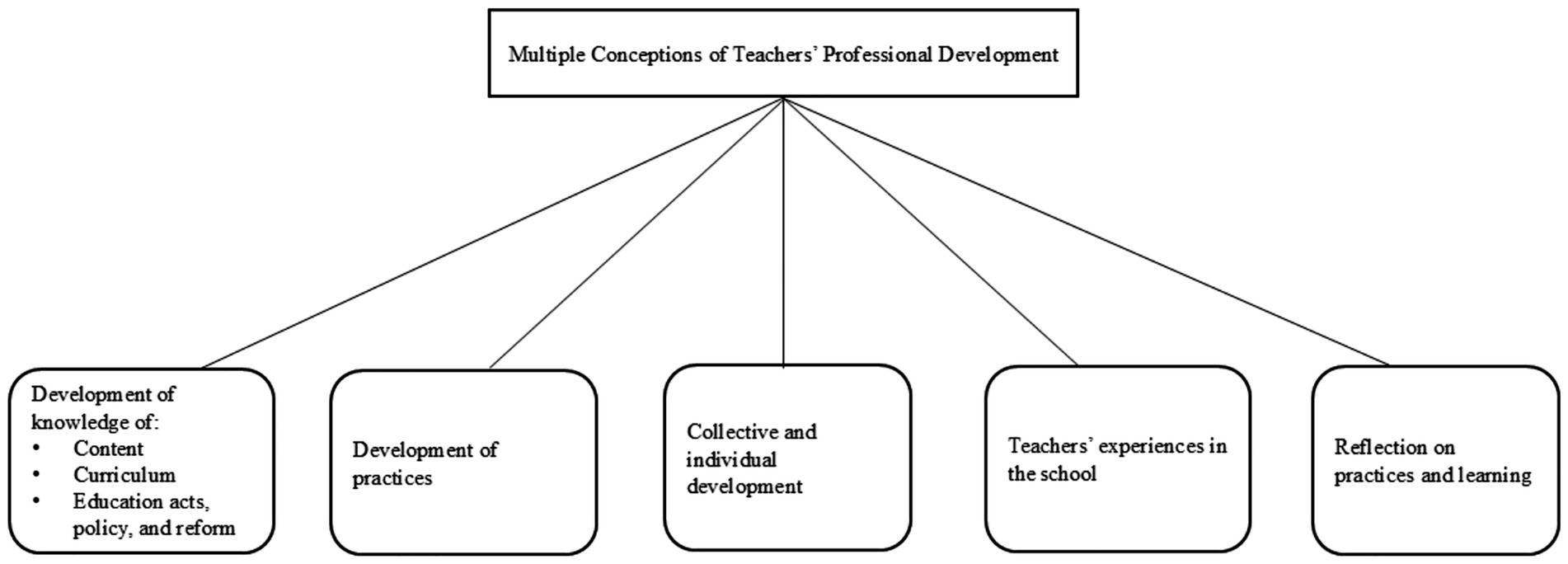

The findings from focus group and individual interviews indicate some similarities and some differences in teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD. In the following, the conceptions that are common among teachers, principals and teacher educators are presented as the “shared conceptions of TPD.” The conceptions held by only one group of the participants, that is, either teachers or principals or teacher educators and the ones shared by two groups of participants, are presented as the “diverse conceptions of TPD.” Teachers, principals and teacher educators shared the conception that TPD is the development of knowledge among teachers. However, they also discerned some unshared or diverse conceptions of TPD. In their diverse conceptions of TPD, teachers highlighted the development of teachers’ teaching practices, and principals and teacher educators emphasized teachers’ engagement in the reflection on practices and continuous learning. The multiple conceptions of TPD held by teachers, principals, and teacher educators are presented in Figure 2.

4.1 Shared conceptions of teachers’ professional development

The findings show that teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ have a shared conception of TPD that TPD is the development of knowledge among teachers. The shared conception of knowledge development further includes the development of knowledge of content, the development of knowledge of curriculum and the development of knowledge of new education acts, policies and reforms.

Teachers, principals and teacher educators conceptualized TPD as the development of teachers’ content knowledge. By content knowledge, they referred to the knowledge of the content that teachers teach, and students learn in the school. Regarding TPD, in focus group 1, Teacher 1 said, “That you develop knowledge of the content” and Teacher 2, in focus group 3 also stated, “Development of knowledge of content.” Likewise, Principal 4 uttered their conception of TPD as, “The development of knowledge of content individually and in collaboration with others.” Similarly, Teacher Educator 7 also conceptualized TPD as “The development of knowledge of content that teachers are offered in their school, or the knowledge they choose to learn themselves when they are in the profession.” Thus, the findings indicate that one of the common conceptions of TPD among the participants in the study is the development of knowledge of content among teachers.

Teachers, principals and teacher educators also conceptualized TPD as the development of knowledge of curriculum. By knowledge of curriculum, they referred to developing a better understanding of the school curriculum they ought to follow for instruction in the school. Concerning the development of knowledge of curriculum, in focus group 1, a teacher articulated,

School develops, and we get a new curriculum that guides that things should be done in different ways. It is important that we, who work in the school, get to learn about the new curriculum, and how we can adapt to develop the school according to the new curriculum. (Teacher 4)

Regarding the development of knowledge of curriculum as TPD, Principal 5 also stated, “Professional development is the knowledge and understanding of curriculum as the regulation for teaching.” Similarly, one of the conceptions of TPD articulated by Teacher Educator 3 was, “It is the development of knowledge of curriculum. Curriculum influences teachers’ professional development and their view towards learning.” The findings indicate that curriculum is the guideline for teaching and learning in schools, and the participants in the study conceptualized the development of knowledge of curriculum as TPD.

The knowledge of education acts, policies and reforms among teachers was highlighted repeatedly by teachers, principals and teacher educators in the study. Thus, the last shared conception of TPD uttered by teachers, principals and teacher educators was the development of knowledge of new education acts, policies and reforms when they referred to knowledge development among teachers. In this regard, one of the principals articulated,

The Norwegian schools, since 2000, have constantly been right-based, in relation to the education acts, either in the form of Article 9A or the others. Surprisingly, teachers know very little about the regulations in the educational laws. Schools are more and more regulated by these laws and policies. So, professional development is to fill up the gaps in teachers’ knowledge of laws and policies of education. (Principal 5)

Concerning the development of knowledge of education acts, reforms and policies as TPD, Teacher Educator 4 also said, “Professional development is to develop the knowledge of educational reforms and policies and develop self as a teacher in line with the educational reforms and policies.” Similarly, some teachers also indicated the importance of familiarity with the changed education reforms in the focus group interviews. For example, Teacher 1, in focus group 1 shared, “Professional development is, in a way, to understand and follow development and changes in the school.” Thus, the participants in the study indicated the need for the understanding of ongoing education acts, policies and reforms among teachers and the awareness of the changes in education acts, policies and reforms. Furthermore, the participants in this study highlighted the necessity of the knowledge of education acts, policies and reforms among teachers in their conceptions of TPD.

4.2 Diverse conceptions of teachers’ professional development

The findings demonstrate that teachers, principals and teacher educators also hold diverse conceptions of TPD in terms of the aspect of teachers’ learning and development they emphasize as TPD. The diverse conceptions include the development of practices by teachers, teachers’ collective and individual development by teachers and principals, teachers’ experiences in the school by principal and teacher educators and reflection on practices and learning by principals and teacher educators.

The findings show that teachers conceptualized TPD as the development of practices. By practices, teachers referred to teaching practices in the school. Teachers articulated concepts like updating practices, skills and competencies in focus group interviews to indicate the development of practices.

Teachers indicate the necessity of changing and updating their teaching practices according to the changing situations when they are in the profession. Highlighting updating practices in their conception of TPD, Teacher 2, in focus group 2, stated, “That we do not stick to a pattern of teaching is professional development.” Likewise, in focus group 1, Teacher 1 narrated, “We had a teacher in school who certainly taught us in the way they did in the 60s. One should not end up being such teacher, but should work to find what works.”

A part of teachers’ conception of TPD is found to be updating hand-on skills to be better at teaching. Teachers also articulated the awareness of the impact of better teaching on students’ learning and well-being. In this regard, in focus group 3, Teacher 1 said, “To develop ourselves in the profession and carry out teaching in good ways, learn new methods or strategies to facilitate students’ learning and well-being.” Likewise, teachers asserted their awareness and skill of the appropriate use of language as their PD. Regarding this, in focus group 4, Teacher 4 said, “It is to be aware of how we use the language and the academic concepts in our profession,” and Teacher 3 continued, “It is to be able to have conversations with our students.”

Teachers imparted a substantial attention to their critical ability to analyze teaching and learning situations, their teaching and learning practices, and the new learning from PD. Thus, they conceptualized PD as being critical to their own practices after they participated in PD interventions. In this regard, a teacher in focus group 2 explained,

I think, it is to be critical to ‘new us’ and look at the things and practices that we already have and that worked well. It does not mean that we do not need to develop us, but we can continue with the ones that we have. All new input or practice may not be useful, or they may not suit all the classes and students. We should be critical to what we choose to use. (Teacher 2)

Likewise, teachers conceptualized PD as updating teachers’ competencies that align with updated and ongoing teacher education at UC. In this regard, Teacher 4 in focus group 1 illustrated, “When a new school curriculum is implemented, teacher education (at the universities) is changed according to the changed curriculum, while teachers in the school do not get that update. Schoolteachers should learn the changes that occur in teacher education.”

It was also found that teachers related the development of their pedagogical and didactical competence to their renewal in the profession which responds to the needs of the changing society. In this regard, in focus group 2, Teacher 2 articulated, “Professional development means we should renew ourselves in relation to the society. We are constantly in development. There are always new challenges in the school, for example, refugees. So, we should develop us both pedagogically and didactically.” Thus, the findings indicate that teachers in the study conceptualized TPD as the development of their practices, and emphasized several aspects of TPD, including the development of hands-on skills for teaching, language, competencies that align with ongoing teacher education, critique of their own classroom practices, and continuous renewal in the profession in their conceptions.

Some teachers and principals conceptualized TPD as teachers’ collective and individual development in the schools. Emphasizing teachers’ collective development during focus group 4, Teacher 1 said, “Collective development in the school provides a common understanding of how we should do things. It is not individual, but it is in a consensus of all teachers in the school and the municipality maybe.” Likewise, among others, Principal 4 pointed out, “When you develop in a profession, you should do it with others. This is what we have done before DeComp, that collaboration is very important. We have allocated time for collaboration so that teachers develop together in the profession.” Teachers exhibit an awareness of the need for teachers’ collective development for the functioning of interdisciplinary collaboration for teaching and learning in the school. In this regard, in focus group 3, Teacher 3 uttered, “We are a part of the teacher community in the school. We should work interdisciplinary here in the school. So, collective development is necessary for professional development.” However, some teachers also conceptualized PD as individual teacher’s development. In this regard, in focus group 2, Teacher 3 articulated, “I think individual development is important” and Teacher 2 continued, “I feel it is on two levels. Teacher’s individual level but it is also important now, it is in collaboration and to be able to collaborate.” Hence, the findings show that teachers’ and principals’ conceptions of TPD include both the development of individual teachers and the development of the teachers’ collective group in the school.

Some teacher educators and a principal conceptualized TPD as the aggregate of teachers’ experiences in the school. In this regard, Teacher Educator 5 stated, “Professional development is the combination of experiences teachers get in the school or from the school culture.” Teacher Educator 3 emphasized dialogue among colleagues in the school for TPD and said, “A lot of professional development happens in dialogue with colleagues where they experiment in groups about what works, they experiment, and have conversations. I think I have learned most in the conversations with colleagues.” Likewise, teacher educators and principals pointed to teachers’ learning and development through their own classroom teaching practices as TPD. In this regard, among other things, Teacher Educator 3 articulated, “The experiences that teachers have in the classroom after formal education (university education)” and Principal 2 mentioned, “That teachers experience and learn through their teaching is professional development” as their conception of TPD. The findings, thus, indicate that teachers’ instructional experiences, which include classroom teaching, and non-instructional experiences, like conversations among teachers in the school, are conceptualized as TPD.

Some teacher educators and a principal conceptualized PD as teachers reflecting on their own practices and continuous learning to be able to teach in a better way when teachers are in the profession. Regarding teachers’ reflections as PD, a teacher educator explained,

I think professional development is the development when one begins to work as a teacher in school through reflection on their practices. One can reflect when one collaborates with others, or one can reflect in relation to research-based articles. To reflect on own practice critically for better practices is professional development. (Teacher Educator 6)

Likewise, Principal 1 also referred to teachers’ reflection in the conception of TPD and stated, “Professional development is how to learn through practices and through reflection, a collective reflection, how we develop together, learn together, how we learn from experiences, practices, and in collaboration with new research.” Similarly, Teacher Educator 7 emphasized teachers’ reflection in relation to theory and practice for TPD and said, “A combination of theories that one reads and practical experiences one gets and the reflection on the theory and practice” in the conception of TPD. Thus, the findings in the study indicate that teachers’ engagement in the reflection of their teaching practices individually and collectively with other teachers is conceptualized as TPD. Furthermore, the findings also denote an emphasis on teachers’ engagement in reflection when they read research-based literature in principal’s and teacher educators’ conception of TPD.

Acknowledging teaching as a contextual and complex activity that demands continuous learning throughout a teacher’s career, a teacher educator also conceptualized TPD as teachers’ continuous learning. In this regard, the teacher educator explained,

Teaching is very complex and contextual. For me, teachers’ professional development is to acknowledge that you, as a teacher, are never finished with learning. You always have the potential for improvements in your teaching, in guiding and facilitating, and context always changes and the content for learning always changes. So, for me, professional development is to be aware of these things and have a desire to learn all the time as a teacher. (Teacher Educator 2)

Hence, the finding indicates that TPD is also conceptualized as teachers’ engagement in continuous learning throughout their teaching careers.

5 Discussion

The findings in the previous section indicate that teachers, principals and teacher educators have various conceptions of TPD, and their conceptions are characterized by similarities and differences. The shared conception of TPD indicated in the finding is the development of teachers’ knowledge. This conception aligns with findings in the prior review of TPD literature (e.g., Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Desimone, 2009). Since all three groups of participants, that is, teachers, principals and teacher educators, are involved in teachers’ learning for TPD, the similarities in their conceptions might not be surprising. Likewise, concurrent with Guerrero-Hernández and Fernández-Ugalde’s (2020) finding of the influence of professional roles on conceptualizations, the differences in the participants’ conceptions could also be anticipated as they have dissimilar professional roles which might have influenced their conceptions of TPD. However, the noteworthy in the finding that adds to the literature on TPD, are the differences in their conceptions where teachers emphasize the development of hands-on skills and practices and competencies for their classroom teaching, whereas principals and teacher educators accentuate teachers’ engagement in reflection of practices for continuous learning throughout their teaching careers.

5.1 Development of knowledge

The findings indicate that teachers, principals and teacher educators conceptualized the development of teachers’ knowledge as TPD. Development of knowledge relates to enhancing teachers’ understanding that enables them to teach effectively (Shulman and Shulman, 2004). The findings also demonstrate that teachers’ knowledge development is conceptualized as the development of knowledge of the content they teach, knowledge of the school curriculum and knowledge of education acts, policies and reforms. These are the foundational knowledge that teachers should acquire (Shulman and Shulman, 2004). The lack of such fundamental knowledge in teachers may not result in learning in their students (Darling-Hammond, 2017). This finding concurs with the result in the teacher-reported empirical studies that teachers’ knowledge of content improved their teaching skills and classroom practices (Birman et al., 2000; Garet et al., 2001). Likewise, conceptions prevail and recur in the theoretical discussions of, for example, Shulman (1986, 1987) and Shulman and Shulman (2004), that the knowledge of the content that teachers teach in schools and of the curriculum that teachers’ teaching practices are based on are obligatory for teachers. However, the conception of the development of knowledge as effective PD is also problematic. Kennedy (2016) argues that a mere reliance on the development of teachers’ knowledge of content does not warrant improvements in students’ learning, rather the development of teachers’ content knowledge should be combined with other rationales like students’ thinking for impactful teaching. Thus, the development of teachers’ content knowledge addresses only one aspect of TPD.

Teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conception of TPD as the development of knowledge of curriculum in this study aligns with Yang et al. (2019) where they found improvements in students’ learning with moderate knowledge of the changed curriculum among teachers. Further, the change in teachers’ practices of curriculum use in teaching is also found to have improved students’ learning (Moore et al., 2021). Shulman (1986) argued that teachers’ understanding of curriculum prepares them for alternative instruction, hence, the knowledge of curriculum of a grade level and across the grade levels is highly recommended. In the Norwegian context, the knowledge of curriculum is an obligatory knowledge requirement for teachers (NMER, 2017a). The Norwegian teachers should practice differentiated instruction as a crucial part of their instructional responsibilities which demands a thorough understanding of the school curriculum (NMER, 2017a). Teachers should learn to use curriculum or change their practice of curriculum use while teaching (Moore et al., 2021). Thus, it is obligatory for teachers to develop the knowledge of curriculum to use the curriculum in teaching that improves students’ learning.

Another shared conception of TPD among teachers, principals, and teacher educators is the development of the knowledge of education acts, policies, and reforms. This finding is scarce in prior empirical research on conceptions of TPD, nevertheless, Sang et al. (2020) found an increase in the knowledge of policies and innovations after teachers participated in PD. However, this finding aligns with the theoretical discussion of the factors influencing TPD, that is, policies influence TPD (e.g., Desimone, 2009; Shulman and Shulman, 2004). As indicated by the participants in this study, there is a high relevance of the knowledge of education acts, policies and reforms in the Norwegian teacher education and TPD in the present times because the core curriculum demands an explicit coherence between teaching and learning practices in the schools and the Education Act (NMER, 2017a). It indicates that knowledge of education acts, policies and reforms is obligatory for the Norwegian teachers. Further, the awareness of such acts, policies and reforms among teachers is one way to develop a shared vision, shared knowledge, commitments and community of practices in schools which Shulman and Shulman (2004) also define as teachers’ learning for TPD. The participants in the study discern the awareness of the significance of collective development of the teachers in the school in their conceptions of TPD.

5.2 Development of practices

The findings indicate that teachers conceptualized TPD as the development of teachers’ practices. Teachers emphasize updating competencies and hands-on skills when they are in the profession as their PD and their efforts for the development of practices for their renewal in the profession. This finding concurs with several prior studies that reported on the development of teachers’ instructional practices after they participated in PD (e.g., Chong and Pao, 2022; Hamilton et al., 2021; Nasri et al., 2023; Yan and Yang, 2019). On the one hand, the development of practices enables teachers to teach effectively (Shulman and Shulman, 2004). On the other hand, the development of teachers’ practices also engages teachers in the learning process (Avalos, 2011). Likewise, Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) argue that the development of practices is teachers’ effort to remain contextually relevant throughout their careers irrespective of what formal teacher education they had acquired. Aligned with the argument of Darling-Hammond et al. (2017), there are indications in the study that PD is the opportunity for teachers to update their competencies and skills that are parallel to the ongoing formal teacher education at UC. The conception that teachers’ awareness of their language use and conversation with their students aligns partly with Baustad and Bjørnestad (2023) who found that these skills were the consequences of teachers’ participation in PD. Notably, the finding indicates that teachers have increased awareness of meaningful language use and communication with students and that they conceptualize the development of these skills as their PD.

5.3 School experiences, and collective and individual development

The findings also indicate that teachers’ experiences in the school were conceptualized as their PD. This finding aligns with prior studies that reported teachers’ enhanced learning when they engaged in instructional activities in the school individually or in collaboration with other teachers (Grau et al., 2017; Nasri et al., 2023; Wang and Wong, 2017). Similarly, the finding also concurs with Kvam (2023) and Postholm (2016). While Kvam (2023) points to teachers’ enhanced pedagogical experiences through their engagement in dialogues, Postholm (2016) finds teachers’ engagement in reflective and observational activities in the school supporting teachers’ individual and collective learning and further strengthening schools’ collective learning environment for teachers. Borko (2004) and Desimone (2009) acknowledge school experiences as continuous learning opportunities for teachers and assert that all the experiences related to teachers’ instructional and professional practices in the school may result in TPD. By emphasizing everyday school experiences as TPD, principals and teacher educators in this study stipulate continuous learning on the part of teachers.

Further, the findings also indicate that teachers’ and principals’ emphasis was more skewed toward teachers’ collective development to meet their school’s and student’s instructional needs. This concurs with Karlberg and Bezzina (2022) who found that teachers preferred collaborative learning for their PD. The finding also indicates that teachers and principals in the schools are also aware of the newer conceptions of TPD that, as Shulman and Shulman (2004) and Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) postulated, is the collective development of teachers in a wider context like school or community. When teachers, as a community, have a positive attitude and willingness to learn, they participate collectively in knowledge development and reflection of learning, practices and experiences in the school, they develop a shared vision, knowledge base, commitment and community of practice (Shulman and Shulman, 2004), thus they may accomplish the goal of impactful teaching and learning in the school. However, Kennedy (2016) and Opfer and Pedder (2011) warn that teachers’ collective participation does not guarantee development unless their collective engagement and efforts are closely followed up. Thus, teachers should be aware of the kinds of activities they are engaged in, and if they are helping to enhance their learning and teaching practices to improve their students’ learning.

5.4 Reflection on practices and learning

The findings show that principals and teacher educators conceptualized TPD as teachers’ reflection on their practices. Teachers’ reflections on their instructional practices as effective learning practices are reported in several previous studies (e.g., Grau et al., 2017; Kvam, 2023; Mukrim, 2017; Nasri et al., 2023; Sang et al., 2020; Wang and Wong, 2017). Teachers’ reflection is crucial for effective PD (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017) since it makes teachers aware of their practices (Mukrim, 2017) and assists them in changing their pedagogical practices (Baustad and Bjørnestad, 2023; Guerrero-Hernández and Fernández-Ugalde, 2020; Nasri et al., 2023). As mentioned by principals and teacher educators in this study and by Shulman and Shulman (2004) in the framework, teachers’ engagement in a structured and critical reflection, individually or in collaboration with others, escalates their learning from their own and others’ experiences, hence, is essential for teachers’ learning and TPD. Principals and teacher educators in the study emphasized teachers’ reflection in the light of research-based knowledge and while collaborating with colleagues in the school in their conception of TPD. This conception indicates that principals’ and teacher educators’ awareness of the policy demands that aim at research-informed collective development of teachers in the schools (NMER, 2017b). Shulman (1987) argues that such reflections encourage teachers to experiment in their classrooms that further, as Seikkula-Leino et al. (2021) indicate, promote learning among teachers through metacognition.

The findings in the study indicate that teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ shared conception included the obligatory knowledge of content and curriculum required for TPD. In addition, their shared conception of TPD is tailored to Norwegian TPD and teacher education as they also emphasized the development of knowledge of education acts, policies and reform which is not often indicated in TPD research literature. Although infrequent, the participants also endorsed the community of practice for TPD in their conceptions as argued by Shulman and Shulman (2004). However, teachers’ diverse conceptualization of PD is restricted and, thus, requires a broader understanding. Teachers’ conception of PD as the development of practices signifies only one aspect of their PD while TPD encompasses a wider scope and is an ongoing process (Darling-Hammond, 1995; Darling-Hammond, 2017; Desimone, 2009; Shulman and Shulman, 2004). As indicated by principals and teacher educators in this study and in the findings in prior studies (e.g., Postholm, 2016; Sang et al., 2020) teachers’ engagement in reflection of their practices individually and in collaboration with other teachers, could be a sustainable approach to TPD.

The findings demonstrate a clear difference between teachers’, and principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD, however, they do not indicate the rationale for the differences. Prior literature stipulates that educators’ conceptions are the results of their practices or the activities they have been engaged in Cobb et al. (1990) and Guskey (2002). This argument may provide insights into the existing differences in the conceptions of TPD where teachers emphasize the development of practices, but principals and teacher educators emphasize reflection on practices and continuous learning. It may be inferred from the findings that, in the past, teachers have mostly participated in PD that focused on improving their teaching practices and or particular skills rather than engaging them in reflection on their practices and continuous learning. Thus, the findings accentuate the necessity for providing PD opportunities to teachers that engage them in reflective practices and continuous learning while also scaffolding the broadening of the scope of their conceptions of PD. Moreover, careful considerations of teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD also have implications in the forthcoming PD policies and practices. Policymakers should consider these conceptions of TPD and the differences in the conceptions while making new TPD policies, selecting relevant PD and processes for engaging teachers in the PD. It is because practices are based on educators’ conceptions, and the policies grounded on their conceptions might facilitate the change and development of teachers’ conceptions (Varnava Marouchou, 2011).

6 Limitations

The study has several limitations. The study involves a small number of teachers, principals and teacher educators from a region in Norway to investigate their conceptions of TPD. Thus, although the study highlights valuable conceptions of TPD, they may not represent the conceptions held by larger teacher, principal and teacher educator groups. Hence, these TPD conceptions may not be generalized. The study shows teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD but lacks to reveal why they hold the conception. Further, as Morgan (1997, p. 10) notes, a “less depth and detail” of teachers’ conception of PD, was expressed in the focus group interviews. Thus, a broader investigation of conceptions of TPD by conducting teachers’ individual interviews may result in a bigger picture of TPD conceptions. Moreover, the conceptions of TPD articulated in the study might have been based on teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ recent experiences of PD after they participated in the TPD within the decentralized policy. Therefore, teachers, principals and teacher educators who participate in TPD through other mechanisms in other contexts may have other conceptions of TPD.

7 Conclusion and further research

This study investigated teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD when they participated in university-school collaboration for TPD within a decentralized policy in Norway. The policy-informed, formal university-school collaboration for TPD was a new initiative in Norway, therefore, it was relevant to understand how teachers, principals and teacher educators conceptualized TPD in the new context within the new policy arrangements. Moreover, conceptions change with changing experiences. The study foregrounds that the development of teachers’ knowledge and practices, teachers’ engagement in reflection on their practices and learning and teachers’ individual and collective development are the key conceptions of TPD. However, the study also highlights that teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of knowledge have expanded to the knowledge of curriculum and education acts, policies and reforms from the development of the content knowledge. Nevertheless, teachers’ conceptions of PD should be expanded.

Future research investigating conceptions of TPD should recruit a larger number of informants so that the findings from the investigation can be generalized. The study indicates that teachers’ conceptions of PD emphasize practices, while principals and teacher educators focus on reflection and continuous learning. Thus, future research needs to investigate different aspects of this discrepancy in the conceptions, for example, why they hold these conceptions. Further, in-depth investigations of teachers’, principals’ and teacher educators’ conceptions of TPD separately may contribute to understanding how these TPD practitioners, in different professional positions, conceptualize TPD. The findings from this study also necessitate more knowledge on engaging teachers in career-long learning processes as their PD rather than mere the development of teaching practices.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dGFyYS5zYXBrb3RhQGhpdm9sZGEubm8=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Norwegian Centre for Research Data or Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Open Access Publication was funded by Volda University College.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to Professor Anne Berit Emstad, Professor Siv M. Gamlem, and Associate Professor Kim-Daniel Vattøy for their feedback. I am also grateful to the lower-secondary school teachers, the principals, and the university-based teacher educators who participated in the study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1554740/full#supplementary-material

References

Almeida, P. C. A. D., Davis, C. L. F., Calil, A. M. G. C., and Vilalva, A. M. (2019). Shulman’s theoretical categories: an integrative review in the field of teacher education. Cad. Pesqui. 491, 130–149. doi: 10.1590/198053146654

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

Baustad, A. G., and Bjørnestad, E. (2023). In-service professional development to enhance interaction – staffs’ reflections, experiences and skills. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 31, 1001–1015. doi: 10.1080/1350293x.2023.2217694

Bautista, A., and Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2015). Teacher professional development: international perspectives and approaches. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 7, 240–251. doi: 10.25115/psye.v7i3.1020

Birman, B. F., Desimone, L., Porter, A. C., and Garet, M. S. (2000). Designing professional development that works. Educ. Leadersh. 57, 28–33.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: mapping the terrain. Educ. Res. 33, 3–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033008003

Chalmers, C. (2017). Preparing teachers to teach STEM through robotics. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 25, 17–31.

Chong, E. K.-M., and Pao, S. S. (2022). Promoting digital citizenship education in junior secondary schools in Hong Kong: supporting schools in professional development and action research. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 11, 677–690. doi: 10.1108/aeds-09-2020-0219

Cobb, P., Wood, T., and Yackel, E. (1990). Classrooms as learning environments for teachers and researchers. J. Res. Math. Educ. 4, 125–146 + 195–210. doi: 10.2307/749917

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Z. Soziol. 19, 418–427. doi: 10.1515/zfsoz-1990-0602

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 4th Edn. London: Sage.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1995). Changing conceptions of teaching and teacher development. Teach. Educ. Q. 22, 9–26.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from international practice? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 291–309. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., and Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educ. Res. 38, 181–199. doi: 10.3102/0013189x08331140

Gamlem, S. (2015). Feedback to support learning: changes in teachers’ practices and beliefs. Teach. Dev. 19, 461–481. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2015.1060254

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., and Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 915–945. doi: 10.3102/00028312038004915

Grau, V., Calcagni, E., Preiss, D. D., and Ortiz, D. (2017). Teachers’ professional development through university-school partnership: theoretical standpoints and evidence from two pilot studies in Chile. Camb. J. Educ. 47, 19–36. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2015.1102867

Guerrero-Hernández, G. R., and Fernández-Ugalde, R. A. (2020). Teachers as researchers: reflecting on the challenges of research–practice partnerships between school and university in Chile. London Rev. Educ. 18:423–438. doi: 10.14324/lre.18.3.07

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 8, 381–391. doi: 10.1080/13540600210000051

Guskey, T. (2003). What makes professional development effective? Phi Delta Kappan 84, 748–750. doi: 10.1177/003172170308401007

Hamilton, M., O’ Dwyer, A., Leavy, A., Hourigan, M., Carroll, C., and Corry, E. (2021). A case study exploring primary teachers’ experiences of a STEM education school-university partnership. Teach. Teach. 27, 17–31. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2021.1920906

Hashweh, M. (2013). “Pedagogical content knowledge: twenty-five years later” in From teacher thinking to teachers and teaching: the evolution of a research community advances in research on teaching. eds. C. J. Craig, P. C. Meijer, and J. Broeckmans, vol. 19 (Leeds: Emerald Group of Publishing), 115–140.

Haynes-Brown, T. K. (2024). Beyond changing teachers’ beliefs: extending the impact of professional development to result in effective use of information and communication technology in teaching. Prof. Dev. Educ. 51, 23–38. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2024.2431697

Ho, D. (2006). The focus group interview: rising to the challenge in qualitative research methodology. Aust. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 29, 5.1–5.19. doi: 10.2104/aral0605

Karlberg, M., and Bezzina, C. (2022). The professional development needs of beginning and experienced teachers in four municipalities in Sweden. Prof. Dev. Educ. 48, 624–641. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1712451

Kennedy, A. (2014). Understanding continuing professional development: the need for theory to impact on policy and practice. Prof. Dev. Educ. 40, 688–697. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.955122

Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How does professional development improve teaching? Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 945–980. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626800

Knott, E., Rao, A. H., Summers, K., and Teeger, C. (2022). Interviews in the social sciences. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 73, 1–13. doi: 10.1038/s43586-022-00150-6

Kvam, E. K. (2023). Knowledge development in the teaching profession: an interview study of collective knowledge processes in primary schools in Norway. Prof. Dev. Educ. 49, 429–441. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2021.1876146

Lay, C. D., Allman, B., Cutri, R. M., and Kimmons, R. (2020). Examining a decade of research in online teacher professional development. Front. Educ. 5, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.573129

Maass, K. (2011). How can teachers’ beliefs affect their professional development? ZDM 43, 573–586. doi: 10.1007/s11858-011-0319-4

Mattheis, A., Ingram, D., Jensen, M. S., and Jackson, J. (2015). Examining high school anatomy and physiology teacher experience in a cadaver dissection laboratory and impacts on practice. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 13, 535–559. doi: 10.1007/s10763-013-9507-8

Moore, N., Coldwell, M., and Perry, E. (2021). Exploring the roles of curriculum materials in teachers professional development. Professional Development in Education, 47, 331–347. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2021.1879230

Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 22, 129–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research: qualitative research methods series, vol. 16. London: Sage.

Mukrim, M. (2017). English teachers doing collaborative action research (CAR): a case study of Indonesian EFL teachers. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 25, 199–216.

Nasri, N. M., Nasri, N., and Abd Talib, M. A. (2023). An extended model of school-university partnership for professional development: bridging universities’ theoretical knowledge and teachers’ practical knowledge. J. Educ. Teach. 49, 266–279. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2022.2061338

National Research Ethics Committee (2021) Guidelines for research ethics in the social sciences and the humanities, 5th ed. Available online at: https://www.forskningsetikk.no/en/guidelines/social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/guidelines-for-research-ethics-in-the-social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/

NMER (2017a). Overordnet del- Verdier og prinsipper for grunnoplæring [Core curriculum- values and principles for primary and secondary education]. Oslo, NMER.

NMER (2017b). Lærelyst-tidlig innsats og kvalitet i skolen (Meld. St. 21 (2016–2017)). [Desire to learn- early intervention and quality in the school (White paper 21 (2016–2017))]. Oslo: NMER.

OECD (2019). Improving school quality in Norway: The new competence development model, implementing education policies. Paris: OECD.

Opfer, V. D., and Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 376–407. doi: 10.3102/0034654311413609

Patton, K., Parker, M., and Tannehill, D. (2015). Helping teachers help themselves. NASSP Bull. 99, 26–42. doi: 10.1177/0192636515576040

Polly, D. (2017). Providing school-based learning in elementary school mathematics: the case of a professional development school partnership. Teach. Dev. 21, 668–686. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2017.1308427

Postholm, M. B. (2012). Teachers’ professional development: a theoretical review. Educ. Res. 54, 405–429. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2012.734725

Postholm, M. B. (2016). Collaboration between teacher educators and schools to enhance development. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 452–470. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2016.1225717

Sang, G., Zhou, J., and Muthanna, A. (2020). Enhancing teachers' and administrators learning experiences through school–university partnerships: a qualitative case study in China. J. Prof. Cap. Community. 6, 221–236. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-01-2020-0003

Seikkula-Leino, J., Salomaa, M., Jónsdóttir, S. R., McCallum, E., and Isreal, H. (2021). EU policies driving entrepreneurial competences- reflections from the case of EntreComp. Sustainability 13:8178. doi: 10.3390/su13158178

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 15, 4–14. doi: 10.2307/1175860

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 57, 1–21.

Shulman, L. S., and Shulman, J. H. (2004). How and what teachers learn: a shifting perspective. J. Curric. Stud. 36, 257–271. doi: 10.1080/0022027032000148298

Sims, S., and Fletcher-Wood, H. (2021). Identifying the characteristics of effective teacher professional development: a critical review. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 32, 47–63. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2020.1772841

Sprott, R. A. (2019). Factors that foster and deter advanced teachers’ professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 77, 321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.001

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development: best evidence synthesis iteration [BES]. New Zealand: New Zealand Ministry of Education.

Varnava Marouchou, D. (2011). Faculty conceptions of teaching: implications for teacher professional development. McGill J. Educ. 46, 123–132. doi: 10.7202/1005673ar

Wang, X., and Wong, J. L. N. (2017). How do primary school teachers develop knowledge by crossing boundaries in the school-university partnership? A case study in China. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 45, 487–504. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2016.1261392

Yan, Y., and Yang, L. (2019). Exploring contradictions in an EFL teacher professional learning community. J. Teach. Educ. 70, 498–511. doi: 10.1177/0022487118801343

Yang, R., Porter, A. C., Massey, C. M., Merlino, J. F., and Desimone, L. M. (2019). Curriculum-based teacher professional development in middle school science: a comparison of training focused on cognitive science principles versus content knowledge. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 57, 536–566. doi: 10.1002/tea.21605

Keywords: beliefs, collective development, development of practices, knowledge development, reflection, teachers’ learning, teachers’ professional development

Citation: Sapkota T (2025) Teachers’, principals’ and university-based teacher educators’ multiple conceptions of teachers’ professional development. Front. Educ. 10:1554740. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1554740

Edited by:

Linda Saraiva, Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo, PortugalReviewed by:

Ali Hamed Barghi, Texas A and M University, United StatesCésar Sá, Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo, Portugal

Valentina Ga, Singidunum University, Serbia

Copyright © 2025 Sapkota. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tara Sapkota, dGFyYS5zYXBrb3RhQGhpdm9sZGEubm8=

†ORCID: Tara Sapkota, orcid.org/0000-0002-8037-236X

Tara Sapkota

Tara Sapkota