- Department of Pedagogical Studies, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

This study examines the perceptions of first-year university student–teachers concerning folk art. The 24 participants completed a 33-question survey assessing various dimensions: prior museum experiences, perceived cultural value, personal relevance, educational applicability, and professional utility. Findings indicate limited early exposure to folk art museums, though participants generally recognized its cultural and educational significance. While many acknowledged folk art’s role in fostering respect for heritage and valued its integration into their studies, interest in personal engagement was more varied, revealing a disconnect between socio-cultural appreciation and individual connection. Folk art was perceived as highly relevant in visual arts, history, and special education but less so in quantitative disciplines, highlighting challenges for interdisciplinary integration. The results underscore the importance of teacher education strategies that cultivate personal engagement with cultural heritage and encourage the incorporation of folk art across curricula, thereby enhancing cultural competence and pedagogical creativity among future educators.

1 Introduction

Traditionally, folk culture is understood as the practices and creations of small, relatively homogeneous, and often rural communities, closely tied to themes of tradition, historical continuity, place, and belonging (Haratyk and Czerwińska-Górz, 2017). It encompasses music, dance, storytelling, mythology, vernacular architecture, crafts, clothing, food, religion, and worldviews, reflecting both material and intangible expressions of life. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scholars and collectors conceptualized “the folk” as communities largely untouched by modernity, viewing their culture as valuable remnants of earlier eras, passed down orally across generations. Since the mid-20th century, however, scholarship has reframed folk culture as a dynamic and evolving phenomenon that exists within the modern world, integrating both traditional and commercial elements across urban and rural contexts (Revill, 2014; Bendix and Hasan-Rokem, 2012). This shift has underscored its contemporary relevance for exploring issues such as identity, habit, diaspora, heritage, authenticity, and cultural hybridity.

In the context of contemporary art education, folk art rooted in everyday life and diverse cultural practices, has been recognized for its potential to bridge tradition and innovation and allow both teachers and students to adopt more inclusive and comprehensive definitions of what constitutes art (Haratyk and Czerwińska-Górz, 2017; Zhao and Gaikwad, 2024). Contemporary educational approaches emphasize its capacity to inspire creativity, foster inclusivity, and encourage critical engagement with cultural diversity (Bronner, 2011; Glăveanu, 2013; Clements, 2025). This educational dimension of folk art extends beyond the classroom into museum contexts, where practices have shifted from focusing primarily on access and preservation to reinterpreting meaning and engaging diverse audiences with exhibits as ongoing processes that values the perspectives of all stakeholders (Dodd and Sandell, 2001; Brody, 2003; Shaffer, 2016). Increasingly, however, the responsibility for sustaining and reinterpreting folk art is also recognized within higher education, where universities are called upon not only to safeguard heritage but also to integrate folk art as a resource for renewing curricula and enriching students’ cultural understanding (Liu, 2023; Zhang, 2023). While students often acknowledge folk art’s cultural and economic value, studies suggest limited personal engagement (Kuščević, 2021), highlighting the challenge of making it relevant in contemporary educational contexts.

Within the framework of the collaborative partnership between the Cyprus Folk Art Museum and the Department of Education at the University of Nicosia in Cyprus, a team of three scholars deemed it essential to investigate university students’ perspectives on folk art as a preliminary step prior to developing further initiatives. The objective of this study was to explore the perspectives on folk art held by a cohort of university students from the Department of Education at the University of Nicosia. This investigation was undertaken in light of the absence of prior research addressing the views of student–teachers on the subject of folk art. Studying the attitudes of student–teachers is significant mainly because it provides valuable insights into how future educators perceive and value cultural heritage, which is essential for fostering cultural awareness and appreciation in diverse educational settings. Understanding these attitudes can also inform the development of teacher education programs by integrating folk art into curricula in ways that resonate with students’ perspectives and professional aspirations. For any context with a rich cultural history, such a study establishes a foundation for attempting to preserving and reinterpreting local traditions, ensuring their relevance in contemporary education while promoting a sense of cultural continuity and inclusivity. We viewed the findings of this study as the cornerstone for highlighting the role of folk art in locally cultivating creativity, critical thinking, and identity formation, essential competencies for contemporary educators.

2 Method

At the beginning of the Fall semester, all student–teachers enrolled in a required introductory art education course (N = 24) were asked to voluntarily complete a brief questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and students were informed that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential, in line with institutional ethical guidelines. All 24 agreed to participate, yielding a 100% response rate (24/24). Most respondents were females aged 18–20 years (79.16%; 19/24). This aligns with the broader trend in Cyprus, where more females typically pursue education classes. All participants were first-year students, which explains why the age range was concentrated between 18 and 20 years. The remainder (20.8%; 5/24) represented other genders within the same age group. Areas. Participants’ place of residence was evenly distributed across urban (50%; 12/24), semi-urban (25%; 6/24), and rural (25%; 6/24) areas.

The research team developed an anonymous 33-question survey divided into two parts to examine student–teachers’ perceptions about folk art. The first section comprised five questions focused on the participants’ previous visits to folk art museums (e.g., “How many times did you visit a folk art museum during your elementary school years?”). The second part contained 28 statements aimed to measure attitudinal items on a Likert scale that ranged from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (6). Among these 28 statements, three statements (q17, q20, q21) were referring to the cultural value of folk art, five statements (q6, q10, q15, q23, q30) were referring to personal interest in visiting folk art museums and eight statements (q8, q12, q16, q18, q25, q27, q28, q33) were intended to examine views on the relevance of folk art in personal lives. Also, eight statements (q7, q9, q11, q14, q19, q24, q29, q32) in the relevance of folk art in the education field and its various disciplines, and four statements (q13, q22, q26, q31) in the usefulness of folk art in long-term professional development. Before distributing the questionnaire, two students of the Department of Pedagogical Studies, not enrolled in the art education course, were asked to review the instrument. They were instructed to (a) read each question carefully, (b) note any terms, phrases, or instructions that seemed unclear, and (c) comment on whether the wording might allow for more than one interpretation (Ruel et al., 2016). They also completed the questionnaire under conditions similar to those planned for participants, and afterwards we conducted a short debriefing interview to gather their impressions. Based on their feedback, we made minor wording adjustments for clarity. To avoid inconsistent interpretations, the questionnaire began with a short definition of a folk art museum. This provided participants with a common frame of reference and ensured they responded with a shared understanding of the concept.

3 Results

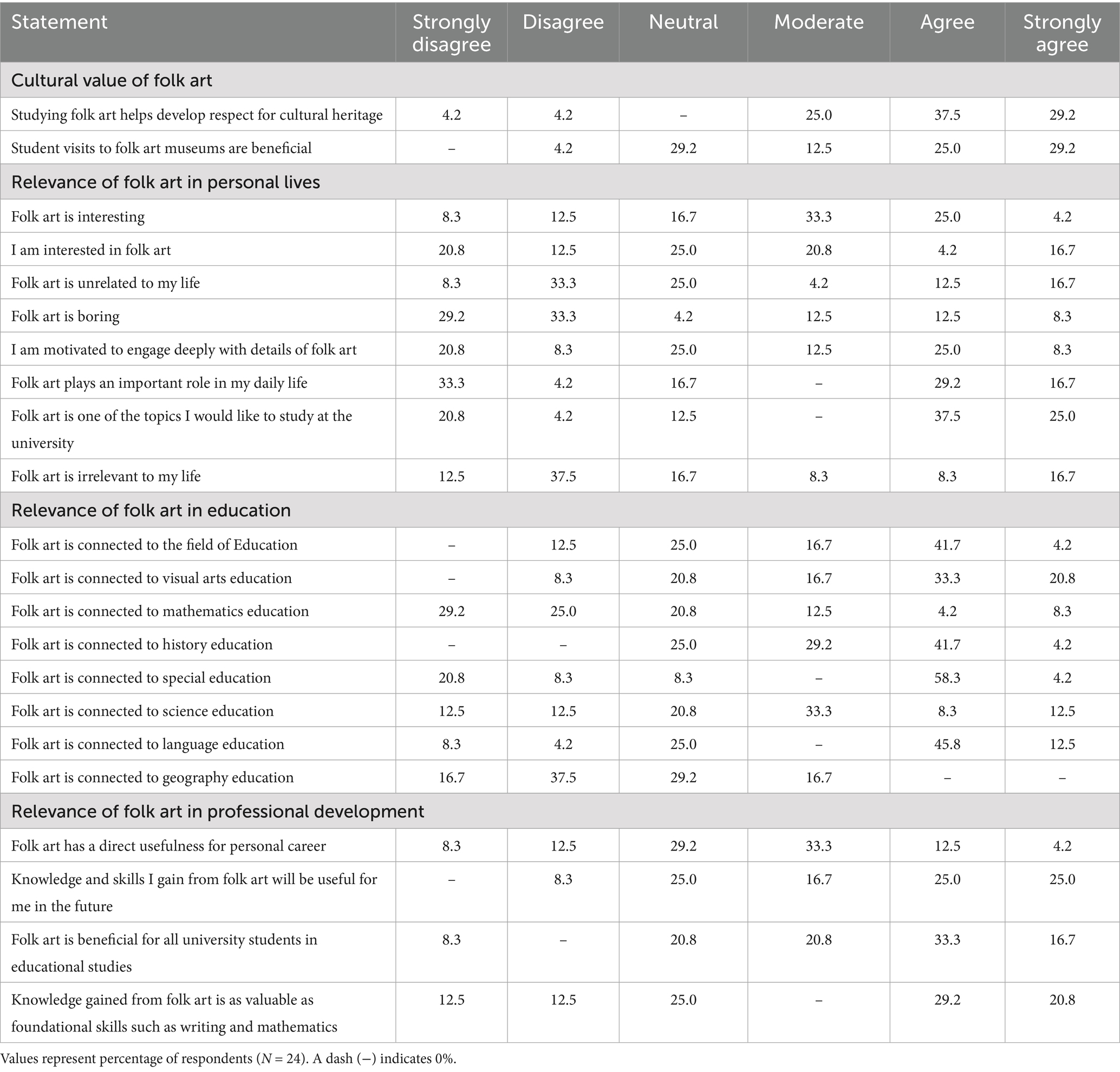

The questionnaire consisted of two parts: the first explored student–teachers’ prior experiences in folk art museums, while the second focused on four thematic categories. The responses of the 24 participants are summarized in Table 1, where values represent percentages and a dash (−) indicates 0%. The following section provides a detailed account of the findings within each category.

3.1 Prior experiences in folk art museums

Among the 24 teacher-students surveyed, 58.3% reported no visits to folk art museums during their preschool years. Approximately one-third reported a minimal number of visits: 16.7% indicated one visit, and another 16.7% indicated two visits. Two student–teachers (8.3%) reported four visits during this period.

In their elementary years, one respondent (4.2%) reported no visits to folk art museums. In contrast, about 83% of participants visited 1–4 times, distributed as follows: 16.7% reported one visit, 25% reported two visits, 20.8% reported three visits, and 20.8% reported four visits. Additionally, 12.5% of respondents reported more than six visits. During the middle school years, around 15% of respondents reported no museum visits. One participant (4.2%) indicated more than 10 visits, whereas the remainder reported 1–4 visits (50% reported one visit, 16.7% reported two visits, 8.3% reported three visits, and 4.2% reported four visits). Lastly, during the high school years, half of the respondents reported no visits to folk art museums, while the other half reported 1–5 visits (20.8% reported one visit, 20.8% reported two visits, 4.2% reported four visits, and 4.2% reported five visits).

3.2 Cultural value assigned to folk art

When participants were asked to evaluate the cultural value of folk art, 87.5% responded positively, with 37.5% indicating they agreed and 50% indicating they strongly agreed. Similarly, a majority of participants agreed that studying folk art helps them develop respect for their cultural heritage, with 37.5% agreeing and 29.2% strongly agreeing. Additionally, participants perceived student visits to folk art museums as beneficial, with 25% agreeing and 29.2% strongly agreeing.

Conversely, some student–teachers provided negative or neutral evaluations regarding the cultural value of folk art. Specifically, 12.5% of participants rated its cultural value as moderate. Furthermore, 8.4% disagreed, and 25% gave a neutral response to the notion that studying folk art helps them develop respect for their cultural heritage. Nearly 40% evaluated school visits to folk art museums at a moderate level, corresponding to a selection of 3 or 4 on the Likert scale.

3.3 Relevance of folk art in personal lives

The assessment of the relevance of folk art in students’ personal lives reveals varied degrees of interest. Over one-fourth of the respondents expressed a positive personal interest in folk art. Specifically, 29.2% agreed or strongly agreed that folk art is interesting, while 20.9% expressed having a direct interest in folk art. Furthermore, 45.9% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that folk art plays an important role in their daily lives, and 62.5% indicated that folk art is one of the topics they would like to study at university. Furthermore, a substantial proportion expressed disagreement or strong disagreement with the statements suggesting that folk art is unrelated to their lives (41.6%), folk art is boring (62.5%), and folk art is irrelevant to their lives (50%), indicating their personal interest in folk art.

In contrast, between 20 and 40% of respondents expressed negative interest in folk art. For instance, 20.8% of teacher-students disagreed or strongly disagreed that folk art is interesting, 37.5% denied that it plays an important role in their daily lives, and 25% stated no interest and in studying it at the university. Additionally, similar percentages viewed folk art as boring (20.8%) and unrelated to their lives (29.2%), and they declined to explore its details (29.1%).

The remainder of participants rated their interest in folk art at a moderate level, typically selecting 3 or 4 on the Likert scale.

3.4 Relevance of folk art in education

When respondents were asked to evaluate the relevance of folk art in their studies, a diverse range of perspectives emerged. A significant portion, 45.9%, agreed or strongly agreed that folk art is connected to their field of study. Notably, 54.1% saw a connection between folk art and visual arts education, indicating a strong perceived relevance in artistic education. Similarly, 45.9% linked folk art to history education, suggesting an appreciation for its historical and cultural significance. Folk art’s relation to special education was highlighted by 62.5% of respondents, emphasizing its potential role in inclusive educational practices. The perceived relevance of folk art varied in relation to other subjects, with 58.3% connecting it to language education, 20.8% to science, 16.7% (moderate level) to geography, and 12.5% to mathematics.

A minority, 12.5%, felt that folk art was not generally connected to their academic field. However, a more significant disagreement emerged in specific subjects. Notably, 54.2% did not see a connection between folk art and mathematics education, and an equal percentage felt similarly about geography education. These results suggest a perception that folk art does not naturally integrate into subjects traditionally considered more scientific or quantitative. Disagreements were also present, though less pronounced, in relation to special education (29.1%) and sciences (25%). A small percentage disagreed or strongly disagreed with the relevance of folk art within visual arts (8.3%) and language education (12.5%). The remainder of participants rated the relevance of folk art in various education disciplines at a moderate level. Usefulness of folk art in professional development.

The assessment of folk art’s usefulness in professional development yielded a mix of perspectives among respondents. A modest 16.7% agreed or strongly agreed that folk art is directly useful for their personal career, highlighting some skepticism about its immediate applicability in long-term professional development. However, half of the respondents (50%) recognized the future utility of knowledge and skills related to folk art. Similarly, 50% agreed that folk art is beneficial for all university students in educational studies, underscoring its perceived value in enhancing educational practices and pedagogy. Additionally, 50% viewed the knowledge gained from engaging with folk art as being as useful as foundational skills like writing and mathematics.

The responses indicating disagreement or strong disagreement with the usefulness of folk art in professional development highlight varying perceptions of its practical value. A notable 20.5% of respondents felt that folk art is not beneficial for their career. Additionally, 33.3% reported disagreement or neutrality regarding the statement that the knowledge and skills associated with folk art would aid them in the future, indicating that over a quarter of respondents do not foresee its benefits extending into their career paths. Furthermore, 29.1% expressed skepticism about folk art’s usefulness for every student in educational studies. Lastly, 25% did not agree that the knowledge gained from engaging with folk art is as useful as basic skills like writing and mathematics. The remainder of participants assessed folk art’s usefulness in professional development at a moderate level.

4 Discussion

This study investigated the perceptions of student–teachers regarding folk art, focusing on their understanding and valuation of cultural heritage. Its significance lies in addressing a notable gap in literature, as limited attention has been given to how future educators engage with and appreciate cultural heritage in their professional preparation. The findings of this study contribute to the existing body of knowledge in at least four keyways.

First, the results of this study indicate that visits to folk art museums were infrequent during the respondents’ early educational years, with significant variation across different stages of their schooling. Among the 24 teacher-students surveyed, more than half (58.3%) reported no visits to folk art museums during their preschool years, which suggests limited early exposure to cultural heritage. This is noteworthy, as early experiences with cultural institutions are often associated with fostering a deeper appreciation for arts and history. The relatively low frequency of visits in the elementary years, with approximately 83% visiting between one and four times, underscores a modest engagement with folk art during formative years. Interestingly, visits to museums appeared to increase slightly during middle school, with 50% of participants reporting between one and four visits. However, the frequency of visits remained limited, and by high school, half of the respondents had not visited folk art museums at all. Similarly, Kuščević (2021) found that while most primary and secondary students visited museums, galleries, and archeological sites once a year (53.7%), only a small percentage (5%) reported more frequent visits. These findings are particularly relevant to education as they suggest that exposure to cultural heritage institutions, such as folk art museums, is not a consistent component of students’ educational experiences, which may limit future educators’ ability to draw on such experiences in their teaching. As Chen and Walsh (2008) argue, museum-based and experiential learning can play a vital role in embedding cultural and artistic education within curriculum. Enhanced early exposure to folk art during formative years could therefore enrich teacher-students’ understanding of culture and foster more holistic approaches to teaching history and the arts in their future classrooms (Clark and Sears, 2020).

Second, the findings underscore a generally positive perception of the cultural value of folk art among student–teachers. A substantial majority (87.5%) of participants recognized the cultural value of folk art, with 50% strongly agreeing, suggesting a broad acknowledgment of its importance as a cultural asset. Furthermore, most respondents (66.7%) believed that studying folk art fosters respect for cultural heritage, emphasizing its potential role in cultivating cultural awareness in educational settings. This has significant implications for teacher education programs, where promoting an appreciation for cultural heritage can enrich future educators’ ability to address diverse student backgrounds (Chen and Walsh, 2008). Congdon (1984) similarly argues that a folkloric approach to the study of folk art can significantly enhance cultural awareness, enabling students to better understand and appreciate the traditions embedded within their communities. The positive evaluation of folk art museum visits (54.2% agreeing or strongly agreeing) further reflects the potential benefits of experiential learning, reinforcing Akhmedova’s (2023) claim that integrating traditional and folk art into teacher training fosters the artistic and esthetic competence of future educators, thereby enriching their ability to transmit cultural knowledge in schools. Yet, some participants (12.5%) rated the cultural value of folk art as only moderate, while 25% expressed neutral views on its educational benefits, suggesting uneven recognition of its pedagogical relevance. Likewise, the 40% who evaluated school visits to folk art museums as only moderately beneficial point to a need for more structured curricular integration. Jiang (2020) asserts that folk art possesses rich educational value beyond its esthetic appeal, encompassing intellectual and moral dimensions. It can enhance students’ esthetic sensibilities, deepen their understanding of national culture, and facilitate a comprehensive grasp of history, customs, and related knowledge. These mixed opinions highlight the need for further exploration into the factors influencing the perceived relevance of folk art within educational contexts, suggesting that not all student–teachers may fully recognize its pedagogical value.

Third, the assessment of the relevance of folk art in students’ personal lives reveals a nuanced spectrum of interest, marked by a tension between cultural valuation and personal disconnection. While a significant proportion expressed positive engagement (29.2% found folk art interesting, 20.9% reported a direct personal interest, and 45.9% agreed on its importance in daily life), some held negative views, with 37.5% stating it lacks importance and 25% showing little interest in further study. Notably, over half (52.5%) expressed a desire to study folk art at the university level, and substantial disagreement with perceptions of folk art as irrelevant (41.6%) or boring (62.5%) highlights its appeal. This coexistence of recognition and disinterest suggests that student–teachers may hold a largely sociocultural conception of folk art’s value, acknowledging its role in heritage preservation and collective identity, without perceiving it as meaningful in their own lives. In this respect, their responses may reflect an inherited appreciation for folk art as a marker of national culture rather than a personally internalized practice. The finding that more than half (52.5%) nonetheless expresses a desire to study folk art at the university underscores this contradiction: even students who are personally disengaged may still view folk art as institutionally or socially important. Similar patterns have been observed elsewhere; for instance, Kudinovienė and Simanavičius (2015) found that while 35% of students lacked personal interest in folk art, many nonetheless acknowledged its importance in preserving national identity, including shaping attitudes toward ethnic art (43.1%), bridging the old with the new (34.5%), and maintaining spiritual and cultural heritage (28.8%). These mixed attitudes highlight the diversity in students’ perceptions of folk art, pointing to the need for educational strategies that address varying levels of engagement. Further research is needed to investigate how sociocultural respect and personal detachment coexist in student–teachers’ perceptions of folk art. It is also important to consider whether particular features of teacher education in Cyprus, where curricula often prioritize the safeguarding of cultural traditions while providing limited opportunities for personal engagement with them (Perikleous, 2010), contribute to this disjunction. If so, the challenge for teacher preparation programs may lie in transforming inherited cultural valuations into lived, personal connections with folk art. As Panganiban (2018) and Jiang (2020) emphasize, the educational significance of folk art extends well beyond its esthetic value to encompassing intellectual, moral, and cultural dimensions. Engagement with folk art can cultivate students’ esthetic sensibilities, deepen their understanding of national culture, and facilitate a comprehensive knowledge and appreciation of history, traditions, and customs. These attributes not only foster respect for cultural heritage but also encourage genuine personal engagement, thereby enriching teacher education programs and enhancing the cultural competence of future educators.

Fourth, the results reveal varied perspectives on the relevance of folk art in respondents’ academic studies, highlighting both the potential integration of folk art across various educational fields and the challenges of its perceived relevance in certain areas. While 45.9% identified folk art as pertinent to their field, its connection was strongest in visual arts education (54.1%) and history (45.9%), emphasizing its role in conveying cultural and historical narratives. Notably, 62.5% linked folk art to special education, highlighting its potential for inclusive pedagogical practices. However, its relevance was less pronounced in technical or scientific disciplines, with only 12.5% seeing a connection to mathematics and 16.7% to geography, and a majority perceiving no link in these areas. These findings suggest folk art is viewed as less aligned with quantitative fields but broadly relevant to humanities and inclusive education. Akhmedova (2023) highlights the role of folk art in developing esthetic sensibilities within fine arts education, while Congdon (1984) suggests that a folkloric approach can extend its relevance beyond the arts, fostering cultural literacy across disciplines. Kuščević (2021) similarly found that heritage education can be effectively integrated into subjects, such as history art and music, but less so in technical fields. This distinction is significant for educational practice, as it highlights opportunities to integrate folk art more effectively into curricula, particularly in the visual and historical arts. At the same time, it underscores the need for creative approaches to bridge the gap and demonstrates folk art’s relevance in disciplines where its connection is less immediately apparent. Atta (2024) provides an example of how embedding traditional Akan art into geometry teaching can enhance conceptual understanding. To bridge this gap further, geography lessons could incorporate local folk spatial knowledge and mapping practices. Yoon (2017) argues that indigenous geographical ideas reflect nuanced understandings of place and environment, emphasizing how integrating this knowledge can enrich geography education. Additionally, chemistry or environmental science could investigate natural dyes and traditional craft materials to link cultural heritage with scientific inquiry. Such interdisciplinary strategies not only bridge content gaps but also deepen student engagement and cultural literacy. Addressing the moderate perceptions of folk art’s relevance across various disciplines could foster broader interdisciplinary connections, enriching students’ academic experiences and enhancing cultural literacy within diverse educational contexts.

Finally, the assessment of folk art’s usefulness in professional development revealed a range of perspectives among respondents. A modest 16.7% agreed that folk art is directly useful for their personal career, suggesting some skepticism regarding its immediate relevance to long-term professional growth. However, half of the respondents (50%) recognized its potential utility in the future, indicating a broader appreciation for the value of folk art knowledge and skills in professional development. Furthermore, 50% viewed folk art as beneficial for all university students in educational studies, emphasizing its role in enriching teaching practices and pedagogy. Some respondents, however, expressed doubts about its practical value, with 20.5% believing it is not beneficial for their career and 31.3% uncertain about its future utility. In line with Akhmedova’s (2023) findings, the incorporation of folk art into teacher education can support the development of creative pedagogical skills and enhance the overall professional competence of future educators, even if its immediate career utility is not always recognized by students. However, 29.1% questioned its relevance to all students in educational studies, and 25% did not consider it as essential as foundational skills such as writing and mathematics. These mixed perspectives highlight the need to clarify and promote the potential contributions of folk art to professional development, particularly in enhancing pedagogical approaches, critical thinking, and cultural awareness. Recognizing its perceived value in future career paths may encourage broader integration of folk art into teacher preparation programs and educational curricula.

Acknowledging and addressing the limitations of this study through transparent reporting, and contextualized interpretations can enhance the validity and applicability of the research. The study was limited to a specific cohort of students within a single department at a single institution. Another limitation of this study is that participants were asked to recall experiences spanning the past 15 years. Retrospective self-reports of this nature are prone to memory inaccuracies, as it is often difficult for individuals to accurately remember how frequently specific events occurred during childhood. Consequently, the findings lack generalizability and do not accurately reflect the perspectives of students from other departments, universities, or geographic regions. Nonetheless, the questionnaire utilized in the study has the potential to be administered to other populations, thereby enabling the collection of contextually relevant data in diverse settings. Additionally, the study was conducted at a single point in time but allows for a second administration of the questionnaire in order to capture changes in students’ perspectives over time, particularly as they progress through their education or gain more exposure to folk art. The questionnaire could also be distributed to other populations to facilitate comparisons between the perspectives of the cohort under study and those of other groups (e.g., students from different academic disciplines, in-service teachers, or members of the general public). A particular valuable contrastive case study population would be students in the hard sciences, whose disciplinary orientation represents an epistemological and pedagogical extreme relative to education students. Indeed, van Broekhoven et al. (2020) demonstrate that although differences between art and STEM students exist, their underlying creative capacities are more alike than unalike, suggesting that such comparisons could yield nuanced insights into the role of disciplinary culture in shaping perceptions of folk art. Such comparisons would enable an assessment of whether the observed views are distinct to the cohort or reflective of broader societal trends.

Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights into how student–teachers perceive folk art, revealing limited early exposure to cultural institutions, generally positive but uneven views of its cultural and pedagogical value, and mixed attitudes toward its personal and professional relevance. While many participants recognized folk art as a valuable resource for fostering cultural awareness and enriching teaching, ambivalence and disciplinary variation highlight the need for stronger curricular integration and experiential learning opportunities. The findings point to the importance of reimagining teacher education programs so that folk art becomes not only a preserved tradition but also a living pedagogical tool that connects heritage with contemporary classrooms (Todino et al., 2025). Insights from the study could inform the design of educational programs, enabling teacher training curricula to integrate folk art more effectively, fostering cultural awareness and appreciation among future educators. As Akhmedova (2023) emphasizes, embedding folk art within teacher education is essential for cultivating both esthetic competence and cultural awareness, ensuring that future teachers are better prepared to integrate cultural heritage into diverse educational contexts. Additionally, findings could guide the creation of teaching materials and activities that use folk art to engage students in creative, interdisciplinary learning, spanning areas such as art, history, language, mathematics and social studies. A folkloric approach, as Congdon (1984) argues, not only enriches cultural awareness but also broadens the scope of educational practice by embedding local traditions into the wider curriculum, making them relevant across disciplines. Engaging student–teachers with folk art thus encourages reflection on cultural values, histories, and identities, strengthening critical thinking and enabling connections between heritage and contemporary issues.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

EP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akhmedova, N. E. (2023). Developing artistic and aesthetic competence in the education of future teachers of fine arts in traditional and folk art. Sci. Innov. 2, 170–173.

Atta, S. A. (2024). Integrating Akan traditional art to enhance conceptual understanding in geometry. J. Educ. e-Learn. Res. 11, 123–130. doi: 10.32674/0xy2cm48

Brody, D. E. (2003). The building of a label: the new American folk art museum. Am. Q. 55, 257–276. doi: 10.1353/aq.2003.0011

Bronner, S. J. (2011). Explaining traditions. Folk behavior in modern culture. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Chen, Y. T., and Walsh, D. J. (2008). Understanding, experiencing, and appreciating the arts: folk pedagogy in two elementary schools in Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Arts 9, 1–19.

Congdon, K. G. (1984). A folkloric approach to studying folk art: benefits for cultural awareness. J. Cult. Res. Art Educ. 2:5.

Dodd, J., and Sandell, R. (2001). Including museums: Perspectives on museums, galleries and social inclusion. Leicester: University of Leicester.

Glăveanu, V. P. (2013). Creativity development in community contexts: the case of folk art. Think. Skills Creat. 9, 152–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2012.11.001

Haratyk, A., and Czerwińska-Górz, B. (2017). Folk art and culture in the historical and educational context. Czech-Polish Hist. Pedag. J. 9, 31–45. doi: 10.5817/cphpj-2017-0011

Jiang, L. (2020). Folk art inheritance and its value in art design education. Front. Educ. Res. 3, 34–37. doi: 10.25236/FER.2020.030507

Kudinovienė, J., and Simanavičius, A. (2015). Folk art as the precondition for developing ethnic culture. Pedagogy/Pedagogika 117, 64–71. doi: 10.15823/p.2015.067

Kuščević, D. (2021). Students’ attitudes to and thoughts on natural and cultural heritage. Školski vjesnik: časopis za pedagogijsku teoriju i praksu 70, 177–196. doi: 10.38003/sv.70.2.8

Liu, Y. (2023). On the value and significance of folk art in art education in colleges and universities. Educ. Rev. USA 7, 730–733. doi: 10.26855/er.2023.06.015

Panganiban, T. (2018). Exploring Filipino education freshmen students’ attitudes toward folk dancing. Int. J. Recent Innov. Acad. Res. 2, 178–188.

Perikleous, L. (2010). At a crossroad between memory and thinking: the case of primary history education in the Greek Cypriot educational system. Education 3–13 38, 315–328. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2010.497281

Ruel, E., Wagner, W., and Gillespie, B. (2016). The practice of survey research. New York: SAGE Publications.

Revill, G. (2014). Folk culture and geography. In D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, & R. A. Marston (Eds.), Oxford bibliographies in geography. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780199874002-0092

Todino, M., Pitri, E., Fella, A., Michaelidou, A., Campitiello, L., Placanica, F., et al. (2025). Bridging tradition and innovation: transformative educational practices in museums with AI ad VR. Computers 14:257. doi: 10.3390/computers14070257

van Broekhoven, S., Furnham, A., and Williams, J. (2020). Differences in creativity across art and STEM students: we are more alike than unalike. Think. Skills Creat. 38:100707. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100707

Yoon, H.-K. (2017). Indigenous “folk” geographical ideas and knowledge. Adv. Anthropol. 7, 340–355. doi: 10.4236/aa.2017.74020

Zhang, L. (2023). An effective path to integrating folk art in art education in universities. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th international conference on social science, education and humanities research (SSEHR 2023).

Keywords: folk art, tradition, culture, art education, student–teacher attitudes, student–teacher perspectives, cultural awareness, teacher education

Citation: Pitri E, Fella A and Michaelidou A (2025) Student–teachers’ perceptions about folk art and their implications for teacher education. Front. Educ. 10:1560489. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1560489

Edited by:

Rafael Guerrero Elecalde, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Edris Zamroni, University of Muria Kudus, IndonesiaBrian Sturm, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States

Copyright © 2025 Pitri, Fella and Michaelidou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eliza Pitri, cGl0cmkuZUB1bmljLmFjLmN5

Eliza Pitri

Eliza Pitri Argyro Fella

Argyro Fella Antonia Michaelidou

Antonia Michaelidou