- 1Direction Provinciale Beni Mellal, CRMEF Beni Mellal Khénifra, MENPS, Beni Mellal, Morocco

- 2Direction Provinciale Fquih Ben Salah, Beni Mellal Khénifra, MENPS, Beni Mellal, Morocco

Introduction: Gender equality in education is crucial for achieving sustainable development and social justice. Despite efforts to promote gender equality in primary education, disparities persist, particularly in regions like Beni Mellal-Khenifra, Morocco. This research assesses the effectiveness of primary school teachers in promoting gender equality practices within this region.

Methods: Drawing on quantitative data collected from 80 primary school teachers, the study assesses teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to gender equality.

Results: Findings reveal strengths in teachers’ commitment to equal opportunities but also highlight areas for improvement, including planning gender-sensitive strategies and addressing gender inequalities effectively.

Discussion: Targeted interventions and professional development programs are recommended to improve teachers’ effectiveness in promoting gender equality. Generally, this research contributes to advancing gender equality in education and underscores the vital role of primary school teachers in fostering inclusive and equitable learning environments. Limitations related to self-report bias and translation issues are acknowledged.

Introduction

Gender equality in education has emerged as a crucial global concern, recognized as a fundamental human right and a cornerstone for achieving sustainable development and social justice (UNESCO, 2015). It involves the pursuit of equal rights, opportunities, and treatment regardless of gender identity, aiming to dismantle rooted norms and systems that perpetuate discrimination and inequality. In particular, education is recognized as a vital avenue for challenging societal inequalities and discrimination. As noted by UNESCO (2016a), achieving gender equality in education is essential not only for individual empowerment but also for promoting social and economic development. In the Moroccan context, the emphasis UNESCO places on individual empowerment aligns with national objectives under the Education and Training Charter, which envisions schools as inclusive spaces that challenge inequality and foster equal participation. However, despite efforts in many areas, gender inequality continues as a significant societal challenge affecting various aspects of life, including primary education. Therefore, evaluating the efficacy of primary school teachers in promoting gender equality practices is vital for advancing this agenda. This paper seeks to evaluate the efficacy of primary school teachers in promoting gender equality within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region through their pedagogical approaches, contributing to broader discussions on educational equity and social justice.

Recent research provides insights into the implementation of gender equality practices in educational settings, both globally and within the Moroccan context. Studies such as those conducted by Larrondo-Ureta and Rivero (2017) highlight the importance of gender mainstreaming in teacher education, and Kitta and Cardona Moltó (2022) emphasize the need for institutional commitment to promoting gender equality. This emphasis on gender awareness in teacher education is particularly relevant in Morocco, where teacher training institutions have not yet fully integrated gender-sensitive content into their programs (UNICEF, 2019a,b). Embedding such frameworks would improve teachers’ readiness to apply equality principles in rural and urban Moroccan schools alike. Similarly, research by Miralles-Cardona et al. (2021) highlights the importance of developing gender competence among educators and emphasizes the significance of assessing teacher self-efficacy in gender-responsive approaches, demonstrating the value of teacher training and awareness in addressing gender disparities in education. The theoretical lens of this study is informed by Bourdieu (1986) concept of habitus, which frames how teachers’ dispositions are shaped by social norms. In addition, gender bias in educational materials remains an underexplored factor contributing to inequality, as highlighted by Blumberg (2008). These sociocultural and institutional dynamics influence how teachers enact gender equality practices in classrooms.

Gender is defined as the social attributes, roles, and expectations associated with being male or female, as opposed to biological differences (UNESCO, 2016b). In educational settings, gender bias—systematic favoritism toward one gender—can significantly influence classroom interactions and student outcomes (Blumberg, 2008). Understanding these constructs is essential for analyzing how teachers promote or hinder gender equality. A gender-responsive pedagogy deliberately addresses these biases by fostering inclusive and equitable learning environments. Research also shows that teachers’ own gender beliefs can significantly impact student outcomes (Ertac and Mumcu, 2018), making their preparation and awareness especially important in shaping equitable classrooms.

A gender-equal and equitable classroom in practice reflects an environment where teachers actively ensure fair treatment, participation, and access to learning opportunities for all students, regardless of gender. This includes using inclusive language, seating arrangements that encourage cooperation between all genders, and instructional materials free from stereotypes. Teachers adopt strategies that allow both girls and boys to contribute equally during classroom discussions and collaborative work. Additionally, a gender-equitable classroom promotes critical awareness by challenging students to question norms and assumptions that support inequality, thereby fostering respect and collaboration. According to UNESCO (2022), such classrooms also incorporate gender-sensitive curricula, teacher-student interactions, and discipline practices that recognize gender-specific needs while promoting equality.

Morocco has made significant efforts in promoting gender equality in education through policy initiatives and legal frameworks (UNICEF, 2019a,b). The National Charter for Education and Training emphasizes gender mainstreaming in educational programs and curricula to create an inclusive learning environment. One concrete policy under this framework is the “Tayssir” program, which provides conditional cash transfers to families to encourage school attendance, particularly for girls. This initiative has significantly increased enrollment rates, especially in rural areas, by addressing financial barriers that often prevent girls from continuing their education. The program has helped reduce dropout rates and improved educational attainment for girls, aligning with Morocco’s commitment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to gender equality and quality education. However, the translation of these policies into effective practices, especially in the public sector, remains a challenge. While Tayssir addresses structural barriers like poverty, its classroom-level translation remains limited as many teachers are not trained on how to adapt their pedagogy to retain and empower newly enrolled students. As a result, gender-responsive teaching is not consistently applied, limiting the program’s long-term impact on gender equality within the classroom. The Global Universities Performance Indicators on Gender Equality (Kolovich and Ndoye, 2023) show disparities in gender equality profiles between Morocco and other countries, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to address localized barriers and challenges. Despite progress in enrollment rates and gender parity indices, disparities persist in educational attainment and quality, particularly in rural areas such as the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region.

In the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region of Morocco, gender disparities in education persist, reflecting broader societal norms and cultural attitudes. While primary education is compulsory and free for all children, gender disparities in enrollment, retention, and educational outcomes persist. Female students, in particular, face barriers such as early marriage, limited access to resources, and societal expectations regarding their roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, the invisibility of gender inequalities in educational settings, as highlighted by Verge et al. (2017), underlines the urgency of assessing teachers’ effectiveness in addressing these issues within the local context.

By synthesizing these insights, this paper seeks to contribute to the existing literature by conducting a comprehensive assessment of primary school teachers’ effectiveness in gender equality practices within the specific context of the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. Through a case study approach, this research aims to identify challenges, gaps, and opportunities for enhancing gender equality in primary education and inform policy and practice interventions to create more inclusive and equitable learning environments.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this research study is to examine the effectiveness of primary school teachers in implementing gender equitable practices within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region of Morocco. The study aims to understand the current state of gender equality in primary education and identify the challenges and opportunities for promoting gender equality within the educational system. By assessing the attitudes, beliefs, and practices of primary school teachers, this research seeks to contribute to the development of strategies and interventions aimed at enhancing gender equality in education.

1. How do primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region demonstrate proficiency in gender-related terminology, awareness of legislation on gender equity, and differentiation between gender equality and equity?

2. To what extent do primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region integrate gender-responsive pedagogy into their teaching practices, including planning strategies, content mainstreaming, and fostering equal opportunities and collaboration among students?

3. How effectively do primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region convey gender-sensitive attitudes, challenge stereotypes, and advocate for gender justice, while engaging with families and collaborating with colleagues to promote gender equality within the educational context?

Methods

This research employs a quantitative research methodology to comprehensively examine the current state of primary school teachers’ effectiveness in implementing gender equality practices within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region of Morocco. The study involves a detailed analysis of teachers’ levels of knowledge, attitudes, and actual implementation of strategies aimed at promoting gender equality in education. By employing a quantitative approach, this research aims to provide empirical evidence and statistical insights into the extent to which gender equality principles are integrated into the teaching practices of primary school educators in this region.

The study employs a cross-sectional survey methodology, an effective approach for capturing teachers’ beliefs and practices at a single point in time across a specific region. The cross-sectional design allows for the efficient collection of quantitative data on gender-related competencies and practices, as supported by Creswell (2014), and is particularly useful in educational research aimed at identifying trends and areas for professional development.

Participants and setting (primary school teachers from the Béni Mellal-Khénifra region)

Participants were selected through a purposive convenience sampling strategy. Teachers were invited based on their accessibility and willingness to participate, with a focus on including both rural and urban schools to reflect regional diversity. We sent an invitation to participate via official educational networks and teacher associations within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region to 115 primary school teachers, from whom we obtained 80 responses (69.56%; see Table 1). Respondents were evenly balanced of males (N = 36; 45.0%) and females (N = 43; 53.8%). The average age of respondents was 27.3 years (SD = 10.4). Respondents primarily held Bachelor’s degrees (n = 76; 95.0%). 77 of them were primary school teachers (96.3%), the 3 others were not. Additionally, respondents varied in their professional experience, with teaching tenures ranging from 1 to over 15 years. Most taught core subjects in primary education, including languages and science.

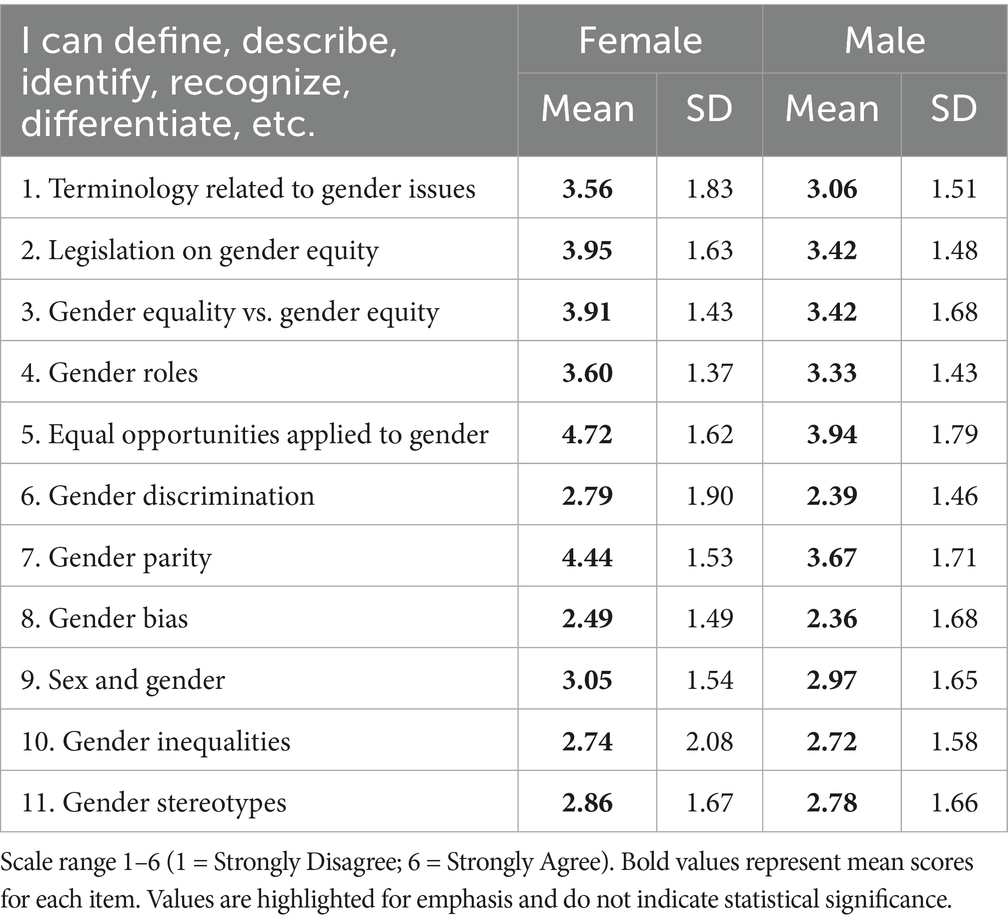

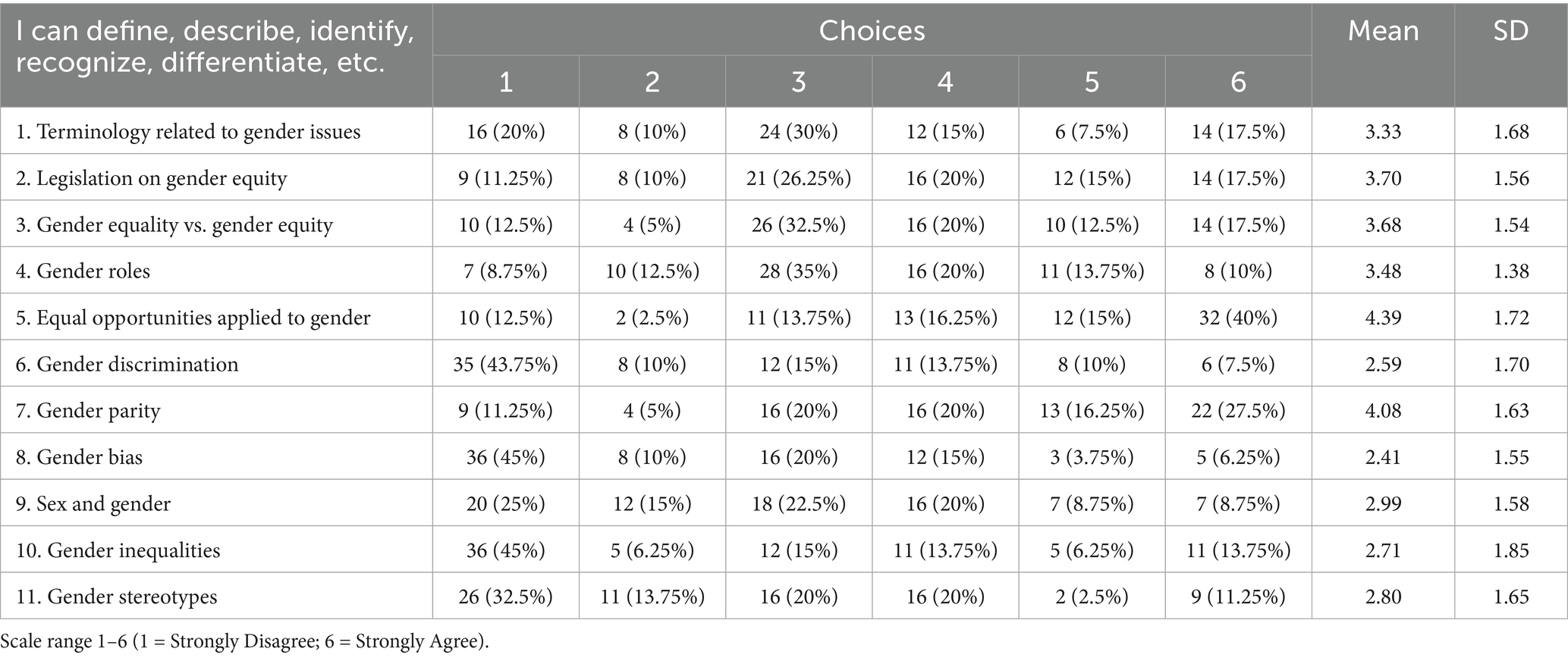

Table 1. Distribution of responses for gender knowledge and awareness among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra Region.

Procedures

Participation was voluntary and confidential. No personal identifiers were collected. The study followed ethical research practices, and according to Moroccan educational research norms.

Participants were selected through purposive sampling, targeting primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. A total of 80 responses were collected from teachers. The assurance of confidentiality ensured that completed questionnaires would not reveal any names or emails, so no link to any individual could be made. Data collection involved the distribution of a structured questionnaire to the participants through Google Forms in the period between April 11th and April 19th. Therefore, it was completed totally online.

Measure(s)

The questionnaire was designed based on five-point Likert scale items and structured into three sections: Section 1 with 11 items, Section 2 with 10 items, and Section 3 with 5 items.

Section 1: Gender Knowledge and Awareness.

Participants rated their proficiency in terminology related to gender issues, awareness of legislation on gender equity, and understanding of gender-related concepts (Table 1).

Section 2: Implementing a Gender-Responsive Pedagogy.

Participants rated their confidence in providing equal opportunities, planning strategies with a gender perspective, mainstreaming gender into course content, and collaborating with colleagues and families to promote gender equality.

Section 3: Developing Gender Attitudes.

Participants rated their ability to convey gender-sensitive attitudes, challenge stereotypes, advocate against gender injustice, and support school-community links for promoting gender equality.

Theoretical framework for survey design

The survey instrument was developed based on key dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and gender-responsive pedagogy drawn from existing literature. In particular, the design was informed by Bandura (1997) theory of self-efficacy, which emphasizes the role of belief in one’s capacity to execute actions required to manage prospective situations. For gender aspects, the framework was adapted from Miralles-Cardona et al. (2021), who validated a self-efficacy scale for sustainable gender equality practices in teacher education. Their dimensions, including knowledge, pedagogical application, and advocacy, informed the structure and content of the three sections in our questionnaire. This theoretical alignment ensured that the survey measured meaningful constructs related to teachers’ competencies in promoting gender equality.

Design and data analytic plan

This study utilized a cross-sectional design to assess the current effectiveness of primary school teachers in promoting gender equality through their teaching practices. The cross-sectional approach is appropriate for capturing a snapshot of the teachers’ gender-related knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and pedagogical practices at a single point in time (Creswell, 2014). By using this design, we can analyze how these factors are currently influencing gender equality efforts in education.

The Beni Mellal-Khénifra region presents unique educational challenges, including high rurality and gender-based disparities in school participation. With one of the highest illiteracy rates in the country (38.7%), as reported by High Commission for Planning (HCP) (2021), and significant numbers of early school leaving among girls, the regional context makes it particularly important to evaluate gender-responsive practices among teachers. These social and economic characteristics contribute to persistent inequality, thereby reinforcing the need for targeted pedagogical strategies.

Participants

The participants were primary school teachers from Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. This selection ensures a representation of the target population, which may vary in terms of experience, exposure to gender equality programs, and demographic characteristics.

Data collection

A Likert scale survey was administered to gage teachers’ proficiency in gender-related knowledge, their awareness of gender issues in education, and their pedagogical approaches to gender equality. This tool was designed to capture a range of responses to measure various dimensions of gender equality practices in the classroom.

Results

In this section, we will present the results of the questionnaire conducted for this study. Each section from the questionnaire will be addressed individually. For each section, we will provide a statistical table displaying the responses, followed by an interpretation of these statistics. Additionally, we will focus on the differences in perceptions between female and male teachers.

Section 1: Gender Knowledge and Awareness.

The findings from the responses to the first section of the questionnaire indicate varying levels of knowledge and awareness among primary school teachers regarding gender-related concepts.

Terminology related to gender issues has a moderate mean score of 3.33 (SD = 1.68), indicating variability in familiarity. While 20% of teachers feel strongly unfamiliar with gender-related terms, 17.5% feel very familiar. This spread highlights a need for more consistent education in gender terminology to ensure all teachers are equipped with the necessary vocabulary to discuss and implement gender equality practices effectively.

Awareness of legislation on gender equity is somewhat better, with a mean score of 3.70 (SD = 1.56). This suggests that while many teachers (52.5%) are knowledgeable about gender equity laws, this knowledge is not uniform across all respondents as a significant number still require further education to ensure that all teachers are well-informed about legal frameworks supporting gender equality.

The understanding of the distinction between gender equality and gender equity shows a mean score of 3.68 (SD = 1.54). Although there is reasonable comprehension among teachers, variability in responses indicates the necessity for professional development to standardize this understanding. A clear grasp of these concepts is vital for teachers to apply them correctly in their educational practices.

When it comes to gender roles, teachers display a moderate understanding with a mean score of 3.48 (SD = 1.38). The inconsistent knowledge across the group suggests the importance of reinforcing this concept as well through ongoing training and discussions.

The statement on equal opportunities applied to gender received the highest mean score of 4.39 (SD = 1.72). While only 2.5% of teachers feel very unfamiliar, a significant 40% feel very confident in applying equal opportunities. This indicates that teachers are relatively confident in applying equal opportunities in gender contexts. However, the high standard deviation reveals significant differences in confidence levels, which means that while some teachers feel very capable, others may need additional support and resources to provide equal opportunities effectively.

In contrast, understanding of gender discrimination is notably lower, with a mean score of 2.59 (SD = 1.70). A substantial 43.75% of teachers feel very unfamiliar with identifying and addressing gender discrimination. This highlights a critical area for improvement, as recognizing and combating discrimination is essential for fostering an inclusive educational environment.

Teachers’ grasp of gender parity is fairly strong, with a mean score of 4.08 (SD = 1.63). While 11.25% of teachers feel very unfamiliar, 27.5% feel very familiar with this concept. However, the variability in responses suggests that not all teachers are equally familiar with this concept, highlighting the need for further clarification and education.

Awareness of gender bias is concerningly low, reflected by a mean score of 2.41 (SD = 1.55). A significant 45% of teachers feel very unfamiliar with recognizing and dealing with gender bias. Addressing this gap in knowledge is crucial to ensure teachers can effectively challenge biases in their classrooms and promote a fair learning environment.

The understanding of sex and gender shows a below-average mean score of 2.99 (SD = 1.58). While 25% of teachers feel very unfamiliar, only 8.75% feel very familiar with this fundamental concept. This indicates that teachers need better education as a clear comprehension of the distinction between sex and gender is foundational for addressing gender issues accurately.

Confidence in recognizing gender inequalities is also low, with a mean score of 2.71 (SD = 1.85). A substantial 45% of teachers feel very unfamiliar with identifying gender inequalities. The high variability in understanding points to an urgent need for comprehensive training in this area to ensure that teachers can recognize and address inequalities in their educational settings.

Finally, the ability to identify and challenge gender stereotypes is reflected in a mean score of 2.80 (SD = 1.65). This low score suggests that teachers generally lack confidence in this area, which is also crucial for promoting gender equality in education.

The analysis of the first section of the questionnaire reveals a mixed level of knowledge and awareness of gender-related concepts among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. While some areas, such as understanding equal opportunities, show relative strength, others, like recognizing gender discrimination and bias, highlight significant gaps. Addressing these disparities through targeted training and professional development is essential for promoting a more gender-sensitive educational environment. This comprehensive assessment provides valuable insights for developing strategies and interventions aimed at enhancing gender equality in education within the region (Table 2).

Following the initial analysis of gender knowledge and awareness among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region, it is crucial to delve deeper into the differences in perceptions between female and male teachers. This analysis focuses on key areas where significant differences were observed, providing insights into how each group perceives their knowledge and awareness.

The data reveals notable disparities between female and male teachers in their understanding and awareness of gender-related concepts. Generally, female teachers report higher confidence and familiarity across several critical areas compared to their male counterparts. Female teachers consistently show a stronger grasp of gender-related terminology and legislation on gender equity. The mean scores for female teachers are 3.56 and 3.95, respectively, compared to 3.06 and 3.42 for male teachers. This suggests that female teachers are more familiar with the terms and legal frameworks essential for promoting gender equality.

Another significant area of difference is in the application of equal opportunities. Female teachers report a mean score of 4.72, markedly higher than the 3.94 reported by male teachers. This substantial gap highlights that female teachers feel more capable of ensuring equal opportunities for all students. This difference underscores the importance of providing male teachers with additional support and resources to boost their confidence and effectiveness in fostering gender equity in the classroom.

Additionally, the understanding of the distinction between gender equality and gender equity shows a notable difference too, with female teachers scoring 3.91 compared to 3.42 for male teachers. This difference is crucial as it affects how teachers implement strategies aimed at achieving gender balance. Female teachers’ higher scores suggest they are better equipped to differentiate and apply these concepts in practical ways, contributing to a more equitable educational environment.

Furthermore, while both groups show low confidence in recognizing gender discrimination, female teachers (mean score of 2.79) report slightly higher confidence than male teachers (mean score of 2.39). This area is critical for creating an inclusive environment where all students feel safe and respected.

Female teachers also demonstrate a higher understanding of gender parity, with a mean score of 4.44 compared to 3.67 for male teachers. This suggests that female teachers are more aware of the need for balanced representation and participation of all genders in the classroom. Bridging this gap is vital for fostering an inclusive environment where all students have equal opportunities to succeed.

The analysis of differences in perceptions between female and male teachers reveals significant gaps in several key areas of gender knowledge and awareness. Female teachers generally report higher confidence and familiarity with gender-related terminology, legislation, and the application of equal opportunities. They also show a better understanding of the distinction between gender equality and equity and are more ready to ensure gender parity. These differences in perceptions between female and male teachers underscore the necessity for targeted interventions to bridge the knowledge gap (Table 3).

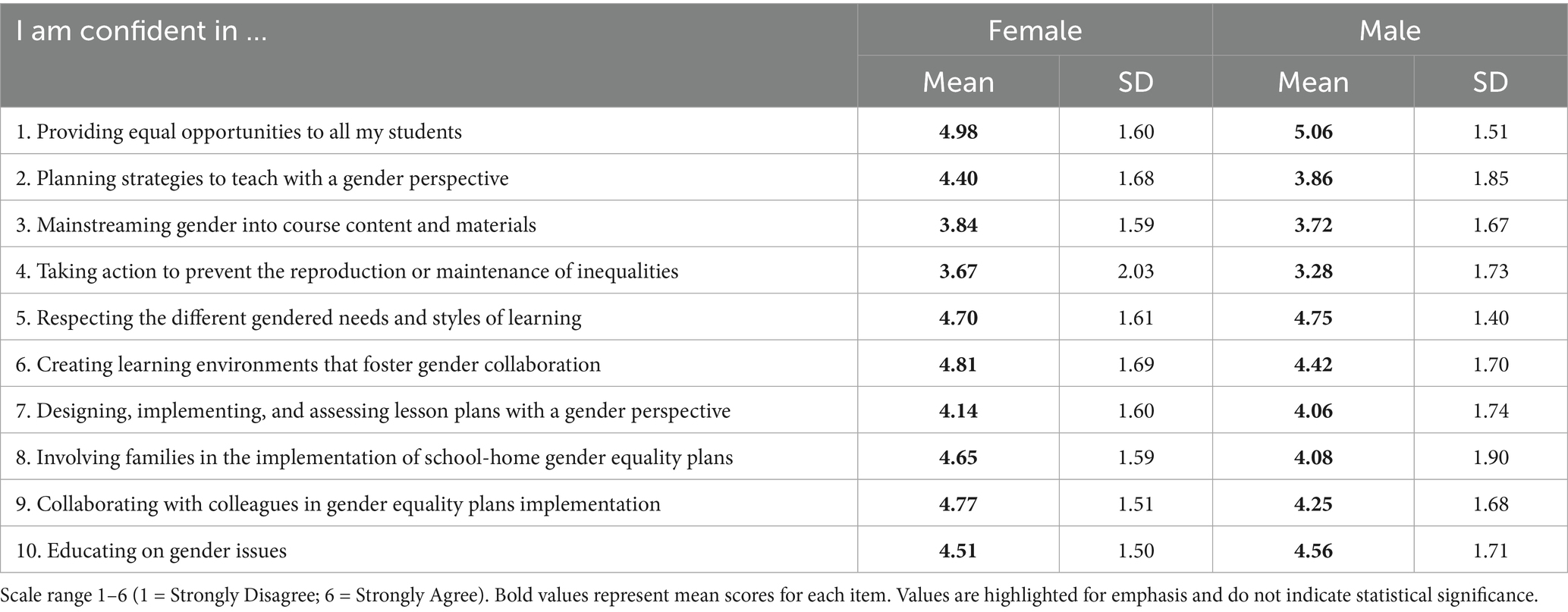

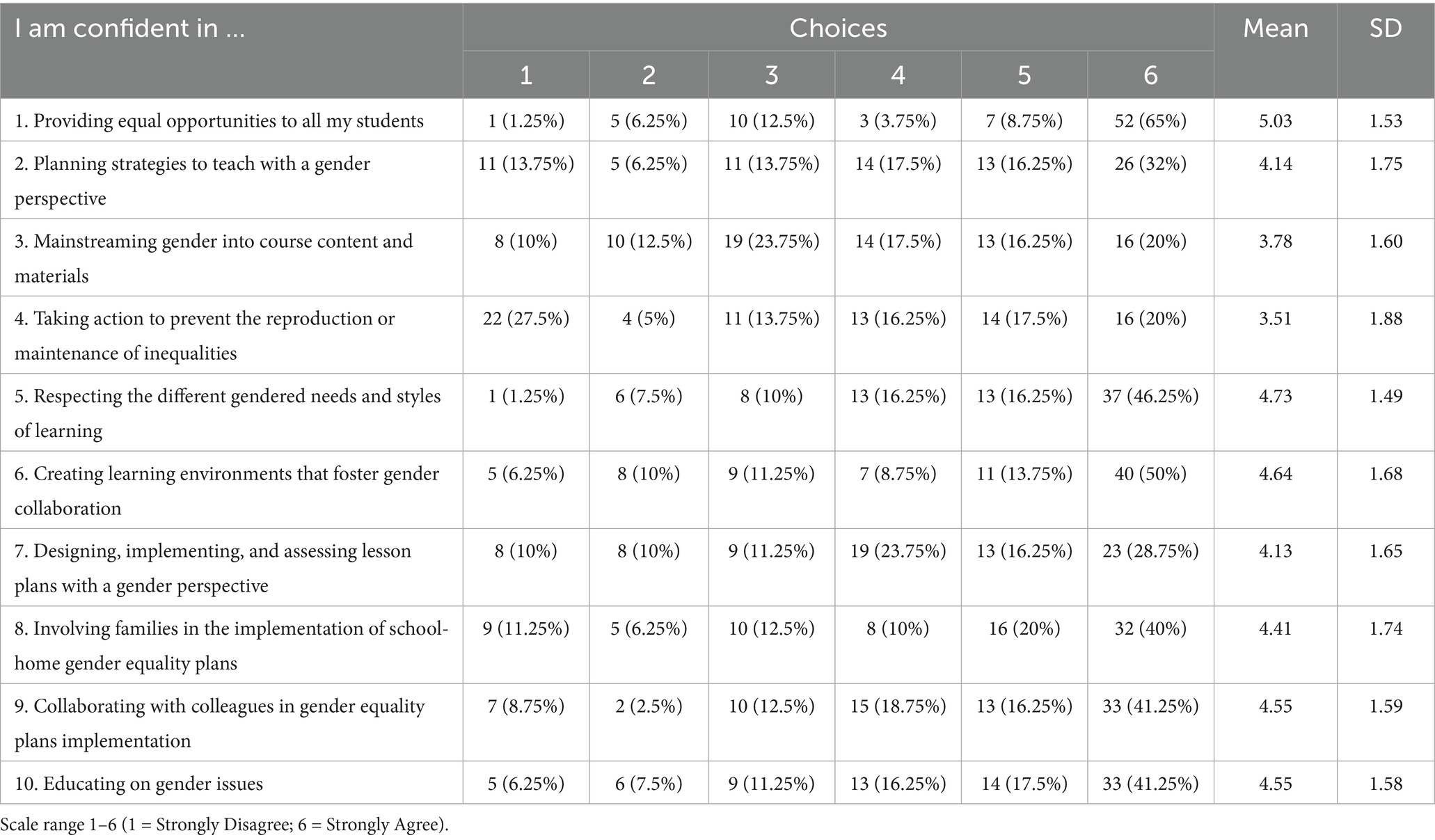

Table 3. Distribution of responses for implementing a gender-responsive pedagogy among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra Region.

Section 2: Implementing a Gender-Responsive Pedagogy.

Implementing gender-responsive pedagogy is crucial for promoting gender equality in education. This section presents the findings from the second section of the questionnaire assessing primary school teachers’ confidence in applying gender-responsive teaching practices in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. The data shows that primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region express varying levels of confidence in implementing gender-responsive pedagogy.

One of the most notable strengths is teachers’ confidence in providing equal opportunities to all students, with a mean score of 5.03 (SD = 1.53). A significant majority (65%) strongly agree with this statement, while teachers may exhibit confidence in their ability to implement inclusive gender practices, this does not necessarily mean they possess the corresponding beliefs or motivation to consistently apply these practices. It is important to differentiate between self-efficacy—the confidence in one’s ability to perform certain tasks—and the willingness or personal conviction to incorporate these practices in the classroom. Research suggests that teachers’ attitudes and value systems play a crucial role in shaping their teaching behaviors, even if they feel capable in a technical sense (Bandura, 1997; Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). This strong confidence reflects positively on the overall dedication of teachers to gender equality.

However, when it comes to planning strategies with a gender perspective, the mean score drops to 4.14 (SD = 1.75). Although a substantial portion of respondents (32%) feels confident, there is a significant percentage of teachers (13.75%) who feel less sure about their ability to plan gender-sensitive strategies. This variability suggests the need for development to augment teachers’ skills in integrating gender perspectives into their teaching plans.

Similarly, the confidence in mainstreaming gender into course content and materials shows a moderate mean score of 3.78 (SD = 1.60). While some teachers are comfortable with this integration, many express uncertainty. Providing practical examples and resources can support teachers in effectively incorporating gender perspectives into their curricula.

Addressing gender inequalities and preventing their reproduction or maintenance presents another area for improvement. With a mean score of 3.51 (SD = 1.88), this aspect shows significant variability, with 27.5% of teachers feeling very unsure. Empowering teachers with the knowledge and tools to actively combat gender inequalities is essential for creating a more equitable educational environment.

Confidence in respecting different gendered needs and learning styles is relatively high, with a mean score of 4.73 (SD = 1.49). Nearly half of the respondents (46.25%) strongly agree with their ability to accommodate diverse learning needs, indicating a strong awareness of gender-specific learning requirements.

When it comes to designing, implementing, and assessing lesson plans with a gender perspective, the mean score is 4.13 (SD = 1.65). Despite many teachers feeling confident, the variability in responses suggests room for improvement. Providing practical tools and resources can help increase their confidence and effectiveness in this area.

Involving families in the implementation of school-home gender equality plans also shows variability, with a mean score of 4.41 (SD = 1.74). While 40% of teachers strongly agree with their ability to engage families, others feel less confident. Strengthening family-school partnerships is essential for reinforcing gender equality practices beyond the classroom.

Collaborating with colleagues in gender equality plans has a mean score of 4.55 (SD = 1.59). While many teachers feel confident, a notable number (12.5%) are less certain. Encouraging collaboration and providing structured opportunities for teachers to work together can enhance the effectiveness of gender equality initiatives.

Finally, the ability to educate on gender issues shows a mean score of 4.55 (SD = 1.58) with a significant number of teachers (41.25%) feeling confident. However, additional training is needed to ensure all teachers can effectively educate their students on gender issues.

The analysis of the second section of the questionnaire reveals a mixed level of confidence among primary school teachers in implementing gender-responsive pedagogy. Teachers generally show strong confidence in providing equal opportunities and respecting diverse learning needs. However, areas such as planning gender-sensitive strategies, mainstreaming gender into course content, and preventing the reproduction of inequalities reveal significant variability in confidence levels. Addressing these gaps and working on teachers’ abilities through targeted professional development and resources is essential for promoting a more gender-responsive education within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region (Table 4).

The analysis of the second section of the questionnaire revealed important insights into the confidence levels of primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region regarding their ability to implement a gender-responsive pedagogy. To further explore these findings, a detailed comparison of perceptions between female and male teachers provides a good understanding of gender-specific attitudes and practices in educational settings.

The overall confidence levels in providing equal opportunities to all students were notably high among both female and male teachers, with mean scores of 4.98 and 5.06, respectively. This reflects a strong, shared commitment to fostering inclusive classroom environments. However, subtle variations in confidence levels across different aspects of gender-responsive pedagogy highlight significant areas for focused interventions.

A critical area of difference emerged in the planning of strategies to teach with a gender perspective. Female teachers reported higher confidence (mean = 4.40) compared to their male counterparts (mean = 3.86). This disparity suggests that female teachers might have greater familiarity or comfort with integrating gender-sensitive strategies into their teaching plans. The variation underscores the need for targeted professional development programs for male teachers to enhance their capabilities in this area, ensuring that all teachers possess the skills necessary to plan effectively with a gender perspective.

Similarly, while both female (mean = 3.84) and male teachers (mean = 3.72) showed moderate confidence in mainstreaming gender into course content and materials, the slightly higher confidence among female teachers suggests they might be more adept at incorporating gender perspectives into their curricula. To bridge this gap, providing practical examples and resources tailored to male teachers could support a more balanced approach in gender mainstreaming across the teaching staff.

The confidence levels in taking action to prevent the reproduction or maintenance of gender inequalities also varied, with female teachers reporting higher confidence (mean = 3.67) than male teachers (mean = 3.28). This difference indicates that female teachers may feel better equipped or more motivated to tackle gender inequalities actively. Empowering all teachers with comprehensive training and practical tools to identify and address gender inequalities can create a more equitable educational environment.

Creating learning environments that foster gender collaboration is another critical aspect where female teachers (mean = 4.81) outperformed their male counterparts (mean = 4.42). The higher confidence among female teachers suggests they may be more effective in encouraging collaborative practices among students. Enhancing male teachers’ confidence through structured opportunities and support in this area can lead to more cohesive and collaborative classroom dynamics, benefiting all students.

Involving families in the implementation of school-home gender equality plans showed notable differences, with female teachers expressing greater confidence (mean = 4.65) compared to male teachers (mean = 4.08). Strengthening family-school partnerships is essential for reinforcing gender equality practices beyond the classroom. Initiatives to improve male teachers’ engagement with families, such as workshops and communication strategies, can foster stronger support networks for promoting gender equality.

Collaboration with colleagues on gender equality plans also showed a gap, with female teachers (mean = 4.77) feeling more confident than male teachers (mean = 4.25). Encouraging collaboration and providing structured opportunities for teachers to work together can enhance the effectiveness of gender equality initiatives. Male teachers may benefit from mentorship programs or collaborative projects that promote shared learning and support in implementing gender-responsive practices.

Interestingly, confidence in educating on gender issues was similar between female (mean = 4.51) and male teachers (mean = 4.56). This parity suggests a general competence among teachers in this area, though the variability in responses indicates room for improvement. Ensuring all teachers have access to continuous professional development and resources can maintain and elevate their confidence and effectiveness in educating students on gender issues.

The comparative analysis of female and male teachers’ perceptions in implementing a gender-responsive pedagogy reveals that while both groups show strong commitment to providing equal opportunities, differences in confidence levels across various aspects of gender-responsive teaching highlight the need for tailored professional development. By addressing these differences in teachers’ abilities, the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region can promote a more inclusive and equitable educational environment for all students, and ensure that both female and male teachers are equally equipped to advance gender equality in education (Table 5).

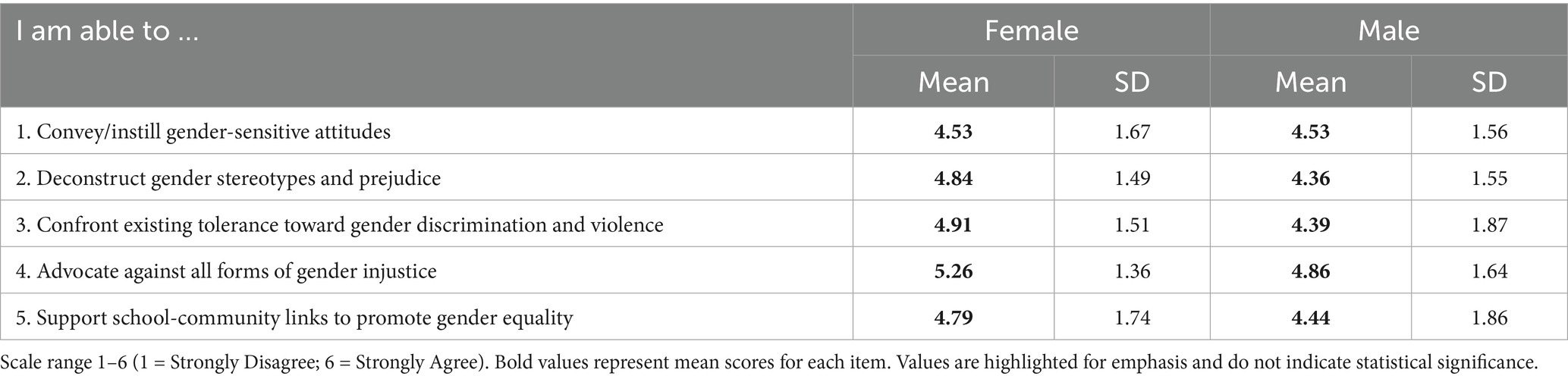

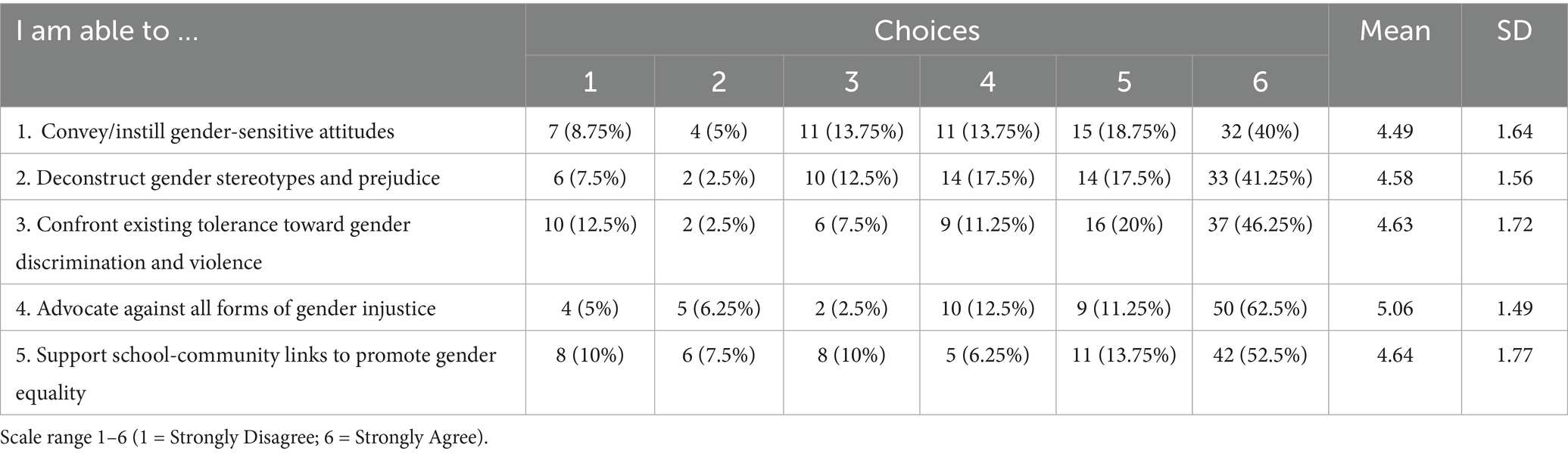

Table 5. Distribution of responses for developing gender attitudes among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra Region.

Section 3: Developing Gender Attitudes.

This section presents the findings from the questionnaire assessing primary school teachers’ confidence in developing gender-sensitive attitudes. As in the previous section, the data in this section also reveals that primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region exhibit varying levels of confidence in developing gender attitudes, with notable strengths in certain areas and considerable room for improvement in others.

Teachers reported a moderate level of confidence in their ability to convey and instill gender-sensitive attitudes, with a mean score of 4.49 (SD = 1.64). While a significant portion of teachers (40%) strongly agree with their capability, a notable percentage (13.75%) remains unsure. This suggests that while many teachers are confident, there is a need for further professional development to ensure all educators can effectively promote gender sensitivity.

Confidence in deconstructing gender stereotypes and prejudice is slightly higher, with a mean score of 4.58 (SD = 1.56). A majority (41.25%) of teachers strongly agree with their ability in this area, indicating a robust understanding among many teachers. However, the presence of some uncertainty (12.5% somewhat disagree) highlights the necessity for ongoing support and resources to help all teachers address and dismantle stereotypes effectively.

Teachers’ confidence in confronting existing tolerance toward gender discrimination and violence shows a mean score of 4.63 (SD = 1.72). With nearly half (46.25%) of the respondents strongly agreeing with their ability, there is a strong commitment to addressing these critical issues. However, with some teachers (12.5%) feeling less confident, there is a need for targeted training programs focused on strategies to combat discrimination and violence.

One of the strongest areas of confidence among teachers is advocating against all forms of gender injustice, with a mean score of 5.06 (SD = 1.49). An overwhelming majority (62.5%) strongly agree with their ability to advocate effectively, reflecting a high level of commitment to gender justice. This strong confidence is a positive indicator of teachers’ dedication to fostering an equitable educational environment.

Finally, teachers’ confidence in supporting school-community links to promote gender equality is moderate, with a mean score of 4.64 (SD = 1.77). While a substantial number of teachers (52.5%) strongly agree with their capability, there is notable uncertainty (10%) among some teachers. Strengthening partnerships between schools and communities can enhance this aspect.

The analysis of the third section of the questionnaire reveals a mixed level of confidence among primary school teachers in developing gender attitudes. While there are notable strengths in advocating against gender injustice and confronting discrimination, areas such as conveying gender-sensitive attitudes and supporting school-community links require further development. Addressing these disparities through targeted professional development and resources is essential for promoting a more gender-responsive educational environment within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. Improving teachers’ skills in these areas will help the educational system and benefit all students (Table 6).

Building on the previous analysis of the third section, this part delves into the differences in perceptions between female and male teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region regarding their confidence in developing gender-sensitive attitudes. The comparative analysis reveals significant variations in confidence levels, which provide insights into the distinct needs and strengths of female and male teachers.

The mean score for both female and male teachers in conveying and instilling gender-sensitive attitudes is identical at 4.53. This parity indicates a shared level of confidence in this area across genders. Despite the overall moderate confidence, there remains room for improvement to ensure that all teachers can effectively promote gender sensitivity in their classrooms.

Female teachers reported higher confidence (mean = 4.84, SD = 1.49) in deconstructing gender stereotypes and prejudice compared to male teachers (mean = 4.36, SD = 1.55). This difference suggests that female teachers might have a better grasp or more practice in addressing stereotypes, potentially due to their own experiences with gender biases. Enhancing male teachers’ skills in this area can help bridge this confidence gap and ensure a more consistent approach to dismantling stereotypes.

Confidence in confronting tolerance toward gender discrimination and violence shows a notable difference, with female teachers reporting a higher mean score (4.91, SD = 1.51) compared to male teachers (4.39, SD = 1.87). This difference highlights a significant area where male teachers may require additional support and training to feel equally capable of addressing and challenging discrimination and violence.

Female teachers also reported higher confidence in advocating against all forms of gender injustice, with a mean score of 5.26 (SD = 1.36), compared to male teachers (mean = 4.86, SD = 1.64). The higher confidence among female teachers underscores their strong commitment to gender justice.

The confidence in supporting school-community links to promote gender equality also showed a difference, with female teachers reporting a higher mean score (4.79, SD = 1.74) compared to male teachers (mean = 4.44, SD = 1.86). This suggests that female teachers may be more proactive or comfortable in engaging with the community to promote gender equality.

This comparative analysis reveals that while there are areas of shared confidence, significant differences exist between female and male teachers in their perceptions of developing gender attitudes. Addressing these disparities through targeted interventions and support is essential for fostering a more gender-responsive educational environment. By enhancing the skills and confidence of all teachers, the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region can ensure a consistent and effective approach to promoting gender equality in education.

Discussion

The findings from the questionnaire reveal a diverse range of knowledge and confidence levels among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region regarding gender-related concepts and the implementation of gender-responsive pedagogy. This diversity highlights the need for targeted professional development to bridge gaps and enhance overall understanding and application of gender equality principles in education.

These findings echo concerns raised in the introduction regarding the limited integration of gender-sensitive content in Moroccan teacher training programs (UNICEF, 2019a,b) and the importance of fostering teacher self-efficacy (Miralles-Cardona et al., 2021). As highlighted by Larrondo-Ureta and Rivero (2017), gender mainstreaming must be embedded in both teacher education and professional development. The low confidence scores in identifying gender discrimination and bias reflect the same gaps identified in the literature, especially in contexts where training on gender issues is inconsistent or superficial (Abid et al., 2025). The findings also align with Bourdieu (1986) concept of habitus, where teachers’ attitudes and confidence are shaped by embedded social norms. The persistence of low confidence in recognizing bias suggests that many teachers operate within a habitus that normalizes gender inequalities. Blumberg (2008) theory of textbook bias further contextualizes the limited teacher awareness of gendered messaging in classroom materials. For example, Ertac and Mumcu (2018) found that Turkish teachers’ traditional gender role beliefs significantly impacted female students’ academic outcomes, underscoring the urgent need to improve teacher awareness. Similarly, Abid et al. (2025) found that many Moroccan trainee teachers hold uncertain or superficial understandings of gender equity and lack practical preparation to implement gender-sensitive practices. These frameworks highlight the importance of not only fostering self-efficacy but also actively reshaping the sociocultural norms that inform teacher practice.

The results indicate variability in teachers’ familiarity with gender-related terminology and concepts. While some areas, such as the understanding of equal opportunities applied to gender, show relative strength, others, such as awareness of gender discrimination and bias, highlight significant gaps. For example, the high mean score for equal opportunities (4.39) suggests that a substantial number of teachers feel confident in this area. However, the low mean scores for gender discrimination (2.59) and gender bias (2.41) indicate a lack of confidence in identifying and addressing these issues.

A notable finding is the divergence between female and male teachers in their confidence and familiarity with gender-related concepts. Female teachers consistently report higher mean scores across various areas, including terminology related to gender issues, legislation on gender equity, and the distinction between gender equality and equity. This disparity suggests that female teachers are generally more prepared to engage with and implement gender-sensitive practices. For instance, female teachers’ mean score for understanding gender parity (4.44) is significantly higher than that of male teachers (3.67), indicating a stronger grasp of balanced gender representation. This supports prior evidence from Kitta and Cardona Moltó (2022), who emphasized institutional responsibility in equipping teachers with practical gender-sensitive tools, a gap still present in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. These differences highlight the need for targeted interventions to improve male teachers’ knowledge and confidence in these areas.

The confidence levels in implementing gender-responsive pedagogy also vary among teachers. Teachers exhibit high confidence in providing equal opportunities to all students (mean score of 5.03), reflecting a strong commitment to inclusivity. However, lower scores in areas such as mainstreaming gender into course content (3.78) and preventing the reproduction of inequalities (3.51) indicate areas needing improvement. The findings also reveal that while many teachers feel confident in respecting different gendered learning needs (mean score of 4.73), a significant portion still requires support in creating collaborative learning environments and involving families in gender equality plans. For example, the mean score for involving families (4.41) suggests variability in confidence levels, highlighting the need for stronger school-family partnerships. These patterns reinforce the need for structured and context-specific implementation of national frameworks like Morocco’s Education and Training Charter, which calls for inclusive practices but lacks clarity on classroom-level execution (UNICEF, 2019a,b; Ministry of National Education, Vocational Training, Higher Education, and Scientific Research, 2000).

The results suggest several key areas for targeted professional development. First, enhancing teachers’ knowledge of gender discrimination and bias is crucial. Many teachers, particularly male educators, reported low confidence in identifying these issues. Professional development should include concrete examples of gender bias in teaching materials, classroom dynamics, and assessment methods, as recommended by Blumberg (2008) and Miralles-Cardona et al. (2021). These sessions can help teachers recognize both overt and subtle forms of bias, fostering more equitable classrooms. Second, addressing gender disparities in teacher perceptions requires tailored training for male teachers. Studies have shown that male teachers may not perceive gender inequalities as urgently as female teachers do (Verge et al., 2017), necessitating differentiated support. Third, mainstreaming gender into teaching practice must go beyond theoretical knowledge. As Moltó and Miralles-Cardona (2022) argue, effective integration of gender-responsive pedagogy requires modeling, mentoring, and sustained reflection, not one-off workshops. Professional development should therefore focus on hands-on strategies such as gender-neutral classroom management, inclusive language use, and collaborative lesson planning with a gender lens. Lastly, involving families and communities in gender equality initiatives is key. Research by UNICEF (2019a,b) underscores the role of community engagement in reinforcing school-based efforts. Teachers need tools and strategies to involve parents and local leaders in creating supportive environments for all students.

To conclude, the analysis of the questionnaire results highlights both strengths and areas for improvement in teachers’ knowledge and implementation of gender-responsive pedagogy in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. Addressing the identified gaps can develop teachers’ ability to support and promote gender equality in education, creating a more inclusive and equitable learning environment for all students.

Implications and recommendations

The variability in teachers’ familiarity with gender-related concepts highlights the need for comprehensive gender training programs. Policymakers should enforce regular professional development sessions focused on gender equality, gender discrimination, and bias to ensure that all teachers have a good understanding of these critical issues. Additionally, integrating gender-responsive pedagogy into the standard curriculum is crucial. Educational authorities should develop and distribute teaching materials that include gender perspectives, ensuring that these principles are embedded in everyday teaching practices. Schools should also adopt clear policies that promote gender equality, including guidelines for non-discriminatory practices, support systems for addressing gender bias, and strategies for creating an inclusive learning environment. Policymakers can provide a framework and resources for schools to implement these policies effectively. In addition to in-service training, the Ministry should consider integrating UNESCO’s Gender Equality Toolkit into preservice programs, particularly within CRMEF teacher training institutes. This toolkit provides concrete strategies for promoting equity through curriculum design, classroom management, and assessment.

Targeted professional development programs should be designed to address specific areas such as identifying gender bias, integrating gender perspectives into the curriculum, and fostering inclusive classroom environments. Given the gaps identified in teachers’ knowledge and confidence levels, it is particularly important to offer tailored training for male teachers to bridge the knowledge gap compared to female teachers. Additionally, schools should implement strategies to engage families in gender equality initiatives, ensuring that gender-responsive pedagogy is supported both at school and at home. Furthermore, providing practical examples and case studies can help teachers better understand and implement gender-responsive practices.

Future research should expand its scope to include a more comprehensive exploration of cultural contexts, specific classroom practices, and the impact of school policies on gender equality. Moreover, conducting longitudinal studies would also be valuable to assess changes over time in teachers’ knowledge and practices. Longitudinal data can help evaluate the long-term impact of professional development programs and policy changes on gender equality in education. Finally, future research should carefully address translation issues and the ambiguity of abstract questions. Clear and accurately translated survey questions can improve the.

The implications of this study highlight the importance of comprehensive training, clear policies, and ongoing research to support the implementation of gender-responsive pedagogy. By addressing the identified gaps and challenges, educators and policymakers can work toward creating a more inclusive and equitable educational environment for all students in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region.

Limitations

While the research provides valuable insights into the knowledge and implementation of gender-responsive pedagogy among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region, several limitations must be acknowledged.

Sample size and representativeness. The study’s sample size may not fully represent the entire population of primary school teachers in the region. In addition to the limited sample size, the use of purposive convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, as participants who were more motivated or available may differ in important ways from those who did not participate. This can limit the generalizability of the findings to all primary school teachers in the region, especially those in remote rural areas or under-resourced schools who may have different experiences with gender equality practices.

Self-reported data. The data collected through the questionnaire is based on self-reporting, which can introduce biases such as social desirability bias, where respondents may provide answers they believe are expected rather than their true beliefs or practices. Moreover, teachers may wish to present themselves as compliant with national gender equity goals. This limitation can affect the accuracy of the reported knowledge and confidence levels in gender-responsive pedagogy.

Translation issues. One significant limitation involves problems with translation and ambiguity of meaning in the translation. The questionnaire was administered in both Arabic and English to accommodate participants’ language preferences. However, nuances in language and potential mistranslations can lead to misunderstandings or misinterpretations of questions. Ambiguity in translated terms may result in inconsistent responses, affecting the reliability of the data.

Abstract nature of questions. Participants faced difficulties in understanding some of the questionnaire questions because they were abstract. Abstract questions can lead to varied interpretations and responses that do not accurately reflect the participants’ knowledge or attitudes. This limitation suggests a need for clearer, more concrete questions in future research to ensure participants fully comprehend and accurately respond to the survey items.

Despite these limitations, the research highlights crucial areas for improvement and professional development among primary school teachers in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. Addressing the issues of translation, ensuring more representative sampling, and clarifying abstract questions can help provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities in implementing gender-responsive pedagogy in the region.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of primary school teachers in promoting gender equality practices within the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region of Morocco. Through a comprehensive assessment of teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices, this research identifies both strengths and areas for improvement in addressing gender disparities in education.

The findings highlight the commitment of primary school teachers to fostering inclusivity and equal opportunities in the classroom. Despite varying levels of confidence in implementing gender-responsive pedagogy, teachers demonstrate a willingness to engage with gender-related concepts and practices. However, significant gaps exist, particularly in areas such as planning gender-sensitive strategies, mainstreaming gender into course content, and addressing gender inequalities effectively.

These findings underscore the importance of targeted interventions and professional development programs aimed at improving teachers’ understanding and effectiveness in promoting gender equality. By equipping teachers with the knowledge, skills, and resources necessary to address gender disparities, educational institutions can create more inclusive and equitable learning environments. Moving forward, policymakers, educational leaders, and stakeholders must prioritize the implementation of gender equality initiatives and support structures within the educational system. Collaborative efforts between government agencies, schools, communities, and international partners are essential for advancing gender equality in education and achieving sustainable development goals.

To sum up, this research contributes to broader discussions on educational equity and social justice, and emphasizes the critical role of primary school teachers in promoting gender equality. By addressing the identified challenges and building on existing strengths, we can work toward creating a future where all children have equal opportunities to learn, grow, and thrive, regardless of their gender.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

OD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This document has been made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abid, M., Bouali, M., El Andaloussi, B., and Messaoud, S. (2025). The perceptions of Moroccan trainee teachers regarding the gender approach and its implementation in the classroom. Front. Educ. 10:1550413. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1550413

Blumberg, R. L. (2008). The invisible obstacle to educational equality: gender bias in textbooks. Prospects 38, 345–361. doi: 10.1007/s11125-009-9086-1

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital” in Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. ed. J. G. Richardson (New York, NY: Greenwood), 241–258.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ertac, S., and Mumcu, A. (2018). Gender stereotypes in the classroom and effects on achievement. The Review of Economics and Statistics 100, 876–890. doi: 10.1162/rest_a_00756

High Commission for Planning (HCP) (2021). Enquête nationale sur la population et la santé familiale. Rabat, Morocco: Haut-Commissariat au Plan.

Kitta, I., and Cardona Moltó, M. C. (2022). Students’ perception of gender mainstreaming implementation in university teaching in Greece. J. Gend. Stud. 31, 457–477. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2021.2023006

Kolovich, L. L., and Ndoye, A. (2023). “Implications of gender inequality for growth in Morocco” in Morocco’s quest for stronger and inclusive growth. eds. R. Cardarelli and Koranchelian. (Washington DC: International Monetary Fund).

Larrondo-Ureta, A., and Rivero, D. (2017). A case study on the incorporation of gender-awareness into the university journalism curriculum in Spain. Gend. Educ. 31, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1270420

Ministry of National Education, Vocational Training, Higher Education, and Scientific Research (2000). The National Charter for Education and Training. Rabat, Morocco: Kingdom of Morocco.

Miralles-Cardona, C., Chiner, E., and Cardona-Moltó, M. C. (2021). Educating prospective teachers for a sustainable gender equality practice: survey design and validation of a self-efficacy scale. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 23, 379–403. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-06-2020-0204

Moltó, M. C. C., and Miralles-Cardona, C. (2022). “Education for gender equality in teacher preparation” In J. A. Boivin & H. Pacheco‑Guffrey (Eds.), Education as the Driving Force of Equity for the Marginalized (Advances in Educational Marketing, Administration, and Leadership book series). Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 65–89.

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

UNESCO (2015). A guide for gender equality in teacher education policy and practices. UNESCO. https://doi.org/10.54675/QKHR5367

UNESCO (2016a). UNESCO’s contribution to the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000244834 (Accessed November 16, 2024).

UNESCO (2016b). UNESCO’S contribution to the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing.

UNESCO (2022). UNESCO’s efforts to achieve gender equality in and through education: 2020 highlights. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380763 (Accessed May 1, 2025).

Keywords: effectiveness, gender equality, primary school teachers, pedagogy, education, gender Bias, gender-responsive pedagogy, Morocco

Citation: Droussi O, Hilali A, Saghraoui Z and Belkacem A (2025) Evaluating primary school teachers’ effectiveness in gender equality practices: a case study of the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region. Front. Educ. 10:1560816. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1560816

Edited by:

Ying-Chih Chen, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Fernando Barragán-Medero, University of La Laguna, SpainAklilu Alemu Ambo, Madda Walabu University, Ethiopia

Claudia Aguirre-Mendez, Emporia State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Droussi, Hilali, Saghraoui and Belkacem. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ottmane Droussi, ZHJvdXNzaW90dG1hbmVAZ21haWwuY29t

Ottmane Droussi

Ottmane Droussi Abdelkrim Hilali

Abdelkrim Hilali Zineb Saghraoui

Zineb Saghraoui Abdelhakim Belkacem

Abdelhakim Belkacem