- 1College of Arts, Society and Education , The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 2Academic Pathways, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 3College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

Background: The wellbeing of university students is crucial for their success. Yet educators struggle with the lack of frameworks to integrate wellbeing into core curricula, and universities often relegate wellbeing initiatives to extracurricular activities. These initiatives frequently fail to engage students and the potential impact to wellbeing is reduced. In Australia, universities are also encouraged to integrate First Nations Knowledge within mainstream curricula, but some academics may be skeptical about the relevance of these knowledge systems in specific disciplinary settings. This study addresses these challenges by exploring the integration of the First Nations-developed Family Wellbeing (FWB) program—a wellbeing-focused soft skills approach—into core university curricula.

Methods: Using constructivist grounded theory methodology, the authors developed the theoretical model “Getting people to experience it,” drawing on in-depth interviews with eight educators who integrated the FWB program within core university curricula in Australia and internationally.

Findings: The study examined the challenges, opportunities, strategies, and outcomes of this integration, revealing significant improvements in wellbeing and soft skills for both students and educators. Viewed through the lens of cultural interface, the findings offer valuable insights into bridging First Nations and Western knowledge systems in higher education.

Conclusion: The theoretical model provides a practical framework for educators to integrate wellbeing and soft skills as core elements of curricula, rather than treating them as optional add-ons. This work has profound implications for addressing student mental health, enhancing soft skills, and creating a more inclusive and effective educational experience.

Introduction

Wellbeing plays a critical role in enabling students to enjoy a happy and fulfilling educational experience (Fraillon, 2004), which is why wellbeing promotion has become a priority for education providers, policymakers, and educators alike (Partridge et al., 2018; Whatman et al., 2019). As a widespread term in both academic and popular literature, wellbeing can be understood from different perspectives: hedonic (experiencing high positive and low negative emotions), eudaimonic (achieving personal goals through autonomy, growth, relationships, and self-acceptance), and social wellbeing (successfully navigating social challenges and functioning in the social world; Procházka and Bočková, 2024). In this study, to serve as a guiding concept, we utilized Dodge et al. (2012, p. 230) definition of wellbeing as “…the balance point between an individual's resource pool and the challenges faced…” This definition resonates with the capabilities approach of Nussbaum (2001), which includes core human capabilities such as standard of living, health, education, social interaction, emotional agility, coexistence, and participation, as foregrounded by Heyeres et al. (2021). Whiteside et al. (2017) similarly define wellbeing as a subjective self-assessment of satisfaction with key aspects of life, including health, relationships, safety, standard of living, achievement, community connection, and future security—factors that correspond with the dimensions measured in the Australian Unity (2022) Personal Wellbeing Index.

Integrating wellbeing into curricula is increasingly recognized as essential for enhancing student educational outcomes (Hassed et al., 2009; Hoare et al., 2017; Whiteside et al., 2017). According to Whatman et al. (2019), social and emotional learning programs are gaining traction as effective methods for boosting student wellbeing in Australia and internationally. Despite various approaches, there is a noticeable gap in the literature regarding the systematic integration of wellbeing programs into university curricula and a dearth of practical guidelines for educators. This study seeks to address this gap by exploring the challenges, opportunities, strategies, and outcomes associated with integrating the Australian First Nations-developed Family Wellbeing (FWB) program into university curricula. The aim is to develop a theoretical model that seamlessly integrates student wellbeing promotion into academic studies without detracting from subject content or adding to student and educator workload.

Background

Challenges affecting university students' mental ill-health

University students face numerous challenges that significantly impact their wellbeing. The transition from secondary to higher education is often fraught with financial instability and deteriorating mental and physical health (Partridge et al., 2018). Globally, millions of young people are diagnosed with mental illness every day, with three-quarters of cases occurring in individuals under 25 years old (Orygen, 2020). In Australia, nearly four million young people experienced some form of mental illness in 2014–15 (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2020). The 2020-2022 Australian National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing revealed that 42.9% of people aged 16–85 had experienced a mental disorder during their lives, with 21.5% affected in the previous year. Anxiety was most common (17.2%), and young adults (16–24) showed the highest prevalence at 38.8% (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2023). According to the Lancet Psychiatry Commission on Youth Mental Health (McGorry et al., 2024), there is a prevalence of global youth mental health crisis, with a 50% increase in mental illness rates in under two decades. Mental health conditions now typically emerge by age 15, with most onsets before age 25, influenced by social media, climate anxiety, and COVID-19 (McGorry et al., 2024). Despite causing 45% of disease burden in youth, mental health receives only 2% of global health funding (McGorry et al., 2024). The commission led by Orygen and involving 50 experts across five continents, calls for urgent system reform and increased investment to address this primary threat to youth wellbeing and productivity (McGorry et al., 2024).

Mental health decline in young adults can impair their academic performance. A study by the National Union of Students in partnership with the mental health service Headspace, reveals that many Australian tertiary students endure high levels of psychological distress due to financial pressures and the struggles of balancing life, work, and study, all of which adversely affect their academic progress and mental health (Rickwood et al., 2016). These stressors are significant risk factors for poor mental health among university students (Browne et al., 2017). Poor mental health can lead to students failing to complete their studies, resulting in low self-esteem, altered career trajectories, higher debt levels, increased stress, and feelings of disappointment (Andrews and Chong, 2011; Orygen, 2020; Rickwood et al., 2016; Waghorn et al., 2010; Whiteside et al., 2017). Consequently, Australian university students are more likely to experience mental illness than the general population, which affects their health, social connections, living standards, and educational and employment outcomes (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2020; Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021; Orygen, 2017b, 2020; Stallman, 2010; Whiteside et al., 2017). Students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds, low socio-economic backgrounds, rural areas, and international students, appear to face seemingly even greater risks and challenges (Orygen, 2017b).

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted populations worldwide, causing widespread physical, emotional, and mental health consequences for millions of individuals (Tuan et al., 2024). This global crisis has exacerbated many factors contributing to mental ill-health among university students worldwide (Ihm et al., 2021). For instance, in the UK, the Office for National Statistics (2020) reported a significant decline in mental health among students in 2020. In Australia, students experienced a loss of motivation, increased psychological distress, and decreased overall wellbeing (Dingle and Han, 2021; Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021). The growing prevalence of these challenges for student mental illness since the pandemic affirms the urgent need to address these contributing factors (Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021).

Universities' response to mental ill-health among students

Development of a global roadmap for mental health research among young people to address current challenges, fill neglected areas, and maximize the potential impact of initiatives is vital, given the dearth of research data on the nature and frequency of mental ill-health among university students in Australia (Orygen, 2017a,b). Optimizing the wellbeing of all tertiary students, both domestic and international, is crucial for the flourishing of Australian society (Partridge et al., 2018). In response, universities are increasingly focused on improving student wellbeing and enhancing the overall student experience through initiatives such as counseling services, academic support, meditation, social events, physical activities, and mental health awareness programs including “RU OK Days” (Eva, 2019; James Cook University, n.d.; Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021; Whiteside et al., 2017).

Despite these efforts, mental distress among students continues to rise (Eva, 2019; Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021). A significant issue is that many wellbeing programs are treated as optional add-ons rather than integral parts of the curriculum, limiting their reach to those who need them most (Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021; Whiteside et al., 2017). For these programs to have a meaningful impact, they must be integrated into the core curriculum rather than being treated as supplementary activities (Klepac Pogrmilovic et al., 2021; Ritter et al., 2018).

The concept of “integration” extends beyond combining subjects into a foundational pedagogical approach. Although “integration” has multiple meanings (Beane, 1997), this paper defines it as systematically embedding wellbeing as core curriculum rather than as supplements. Powell and Graham (2017) advances this view by maintaining that student wellbeing support has evolved from a disconnected initiative to an integral element of education itself. Interventions integrated into standard curriculum improves implementation quality (Barry et al., 2017). Furthermore, this paper draws on Lister and Allman's (2024) framework of “embeddedness” regarding student mental wellbeing to clarify the concept of “integration” as: (a) modeled in practice, meaning wellbeing is intrinsic to teaching pedagogy and course structure, beyond mere subject matter; (b) customized to student needs; (c) fundamental to institutional values; (d) collaborative; and (e) explicitly planned and resourced. True wellbeing integration involves: systematic embedding throughout academic content (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL], 2021; Rowe et al., 2007; Wyn et al., 2000); synergistic reinforcement of academic goals (Rowe et al., 2007); multi-level implementation across curriculum, teaching, and policies (Barry et al., 2017; Powell and Graham, 2017); holistic development across cognitive, physical, social, and emotional domains (Lewallen et al., 2015); and infusion throughout subjects rather than isolation in dedicated lessons (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL], 2021; Stirling and Emery, 2016). This represents a shift from peripheral to intrinsic positioning of wellbeing in education.

Integrating First Nations Knowledge in mainstream university curricula

In Australia, universities are encouraged to integrate First Nations Knowledge into mainstream curricula (The University of Melbourne, 2024). This initiative is driven by both educational goals and a commitment to inclusivity and reconciliation, which acknowledges the transformative potential of First Nations Knowledge (Australian Government Department of Education, 2023; The University of Melbourne, 2024). The integration serves to increase the visibility of First Nations Knowledge, which can potentially boost self-esteem and academic engagement among both non-First Nations and First Nations students (Nakata, 2002). Moreover, it is considered a crucial step toward national improvement and building a better Australia (The University of Melbourne, 2024). By incorporating First Nations knowledge systems, histories, and cultures into the curriculum through new resources and professional development modules, all Australian students are given the opportunity to engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives (The University of Melbourne, 2024). This heightens the importance of knowledge translation into practice.

Knowledge translation is essential for effectively incorporating evidence into practice (Esmail et al., 2020). Knowledge translation involves developing evidence-based, scientific, and practical methods for implementing research findings, thereby enabling rapid and reliable improvements (Geng et al., 2017; Grimshaw et al., 2004; Reed et al., 2018). This iterative process includes the dissemination, synthesis, and exchange of ethically sound knowledge to drive positive change (Canadian Institutes for Health Research, 2017; Esmail et al., 2020). In the context of this study, knowledge translation provides a valuable framework for integrating wellbeing interventions into existing curricula, evidencing the significance of study findings in informing practice and measuring impact. Our work is consistent with the Australian Research Council's emphasis on research that enhances productivity and wellbeing for long-term economic growth and societal improvement (Australian Research Council, 2022a,b; Jefferson et al., 2024). As Tsey et al. (2016, p. 1) assert, research is “…of limited value unless the evidence created is used to make smarter decisions for the betterment of society.”

Reed et al. (2018) propose three strategic principles, known as SHIFT-Evidence, for knowledge translation: (a) “act scientifically and pragmatically” by combining existing evidence with unique system conditions and adapting to emerging complexities; (b) “embrace complexity” by recognizing that evidence-based interventions depend on related practices and addressing interdependent system issues; and (c) “engage and empower” by leveraging insights from staff and beneficiaries to operationalize translation and navigate system changes. These principles are instrumental in guiding the translation of research into practice and fostering collaboration among policymakers, academics, patients, and practitioners to use interventions for improvement (Reed et al., 2018).

Applying SHIFT-Evidence principles to this study involved: (a) grounding knowledge translation in scientific and pragmatic approaches by integrating existing FWB program evidence with unique conditions and adapting interventions to emerging complexities; (b) embracing complexity by understanding the interdependent aspects of curricula, identifying issues affecting student wellbeing, and addressing underlying factors; and (c) engaging and empowering by drawing on educators' previous FWB insights to enhance wellbeing integration, guiding changes driven by their concerns. This approach led us to pose the following research question: What are the challenges and opportunities involved in integrating an Australian First Nations wellbeing program in university curricula?

As part of this strategy, the aim was to integrate the FWB program into university curricula in a way that complements learning objectives without increasing the workload for students and educators. The challenge lay in the lack of frameworks or tools to support busy educators and researchers in seamlessly incorporating research evidence into existing teaching subjects using continuous quality improvement approaches. This study sought to address this gap by developing a theoretical model that facilitates the seamless integration of the FWB program into university curricula.

The Family Wellbeing (FWB) intervention program

The FWB program is an empowerment intervention developed by Australian First Nations people to help individuals and families gain greater control over their lives (Tsey, 2019; Tsey et al., 2018; Whiteside et al., 2017). The program offers a structured framework, along with tools and resources, to guide participants through a step-by-step empowerment process aimed at enhancing wellbeing, personal development, and overall quality of life (Deloitte Access Economics, 2022; Nolan et al., 2024; Perera et al., 2022; Tsey et al., 2018). The program is designed to cultivate essential social competencies for navigating life's challenges by addressing emotional, physical, spiritual, and mental needs (Tsey et al., 2018, 2005; Whiteside et al., 2014). When these basic needs are unmet, individuals may struggle to cope, leading to personal or relationship difficulties (McCalman, 2009; Tsey et al., 2018).

The FWB program teaches key concepts such as wellbeing, resilience, emotional intelligence, and practical wisdom (phronesis), which are increasingly recognized by universities as vital, yet challenging to integrate into curricula (Tsey, 2019; Tsey et al., 2018, 2005; Yan et al., 2019). Supported by over 23 years of research, the program has demonstrated significant improvements in social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB), enabling participants to engage more fully in life, community, education, and employment (Deloitte Access Economics, 2022; Nolan et al., 2024; Perera et al., 2022). To date, more than 5,000 individuals have participated in the program across more than 80 locations in Australia and abroad (Deloitte Access Economics, 2022; Perera et al., 2022). An evaluation of the program found that for every dollar invested in delivering the FWB program in one Australian First Nations community between 2001 and 2021, $4.80 in benefits was generated for participants and the community (Deloitte Access Economics, 2022).

Commencing in 2021, a five-year program has focused on FWB research translation and impact evaluation. The goals of this initiative are to: (a) bring together FWB user organizations, training providers, and researchers in collaborative partnerships; (b) integrate the FWB program within, or use it to, enhance existing First Nations education, employment, and business development support programs and services; (c) evaluate the outcomes; and (d) use the results to influence First Nations wellbeing, education, and employment policies. This study is part of the larger program to translate research into practice. It is particularly focused on leveraging the experiences of educators who have integrated the FWB program within their curricula across universities in Australia and overseas. In this context, integration denotes how these educators adapted their existing course content by evaluating, aligning, and updating materials with FWB program elements, effectively incorporating aspects of the program despite curriculum constraints.

Methods

Study design

To explore the integration of the FWB program within university curricula, we employed the constructivist grounded theory of Charmaz (2006, 2008, 2014), which emphasizes the subjectivity of the research process and the researcher's active role in constructing and interpreting data (Creswell and Poth, 2016). Grounded theory, as described by Corbin and Strauss (2008), is a qualitative research design in which the researcher develops a comprehensive explanation of a process, action, or interaction by drawing insights from the perspectives of various participants. Charmaz's approach recognizes the importance of examining the relationship between the researcher and participants and acknowledges the role of written expression in shaping a final text grounded in the data (Birks and Mills, 2015). This approach was chosen due to the absence of existing frameworks or tools to guide educators and researchers in seamlessly integrating wellbeing initiatives into teaching subjects. By choosing constructivist grounded theory, we aimed to create a theoretical model that not only facilitates the integration of FWB into curricula but also incorporates the researcher perspective. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee at James Cook University (JCU; H8811). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Participants were each assigned a pseudonym to ensure anonymity in reporting.

Study context and participants

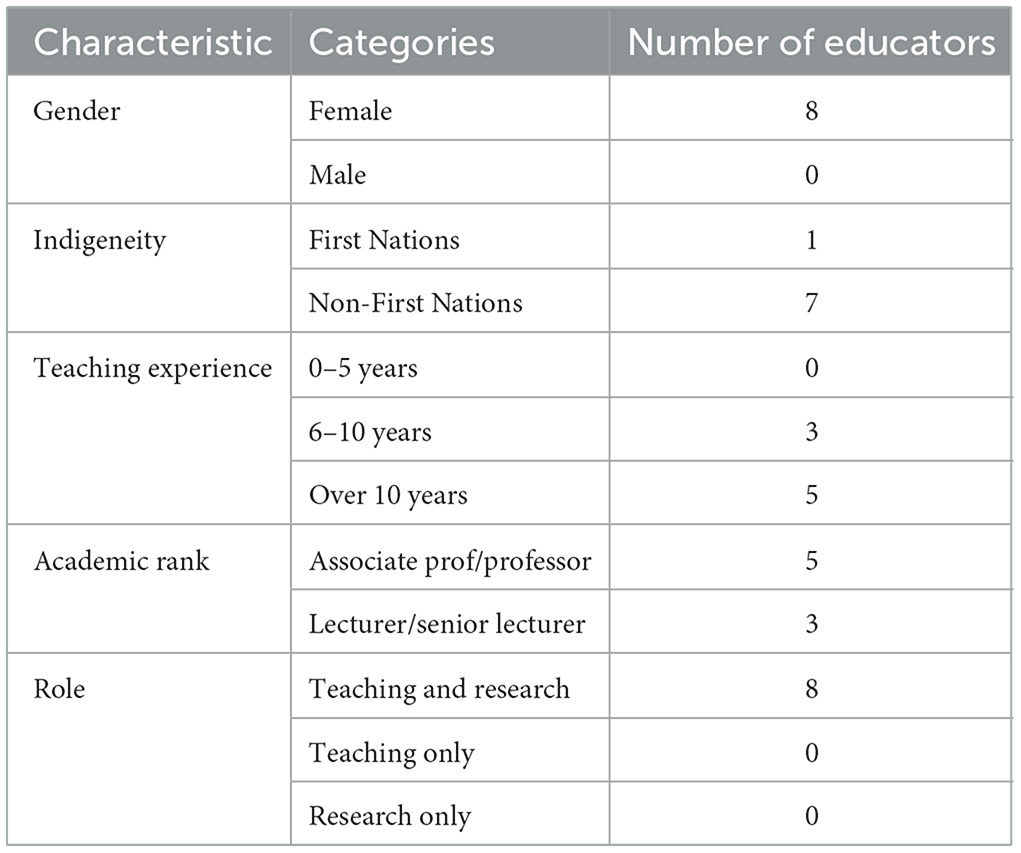

Purposive sampling was used to recruit university educators who had integrated the FWB program in higher education settings, both in Australia and internationally as participants in the study. Of the eight educators recruited from a pool of 11 available educators, all were female. One educator identified as First Nations, while seven were from non-First Nations backgrounds. All participants had substantial teaching experience, with three having taught for 6–10 years and five having over a decade of teaching experience. Their academic ranks were fairly senior, with five holding positions at the Associate Professor or Professor level, and three at the Lecturer or Senior Lecturer level. All eight participants held combined teaching and research roles. The background information of these educators is depicted in Table 1.

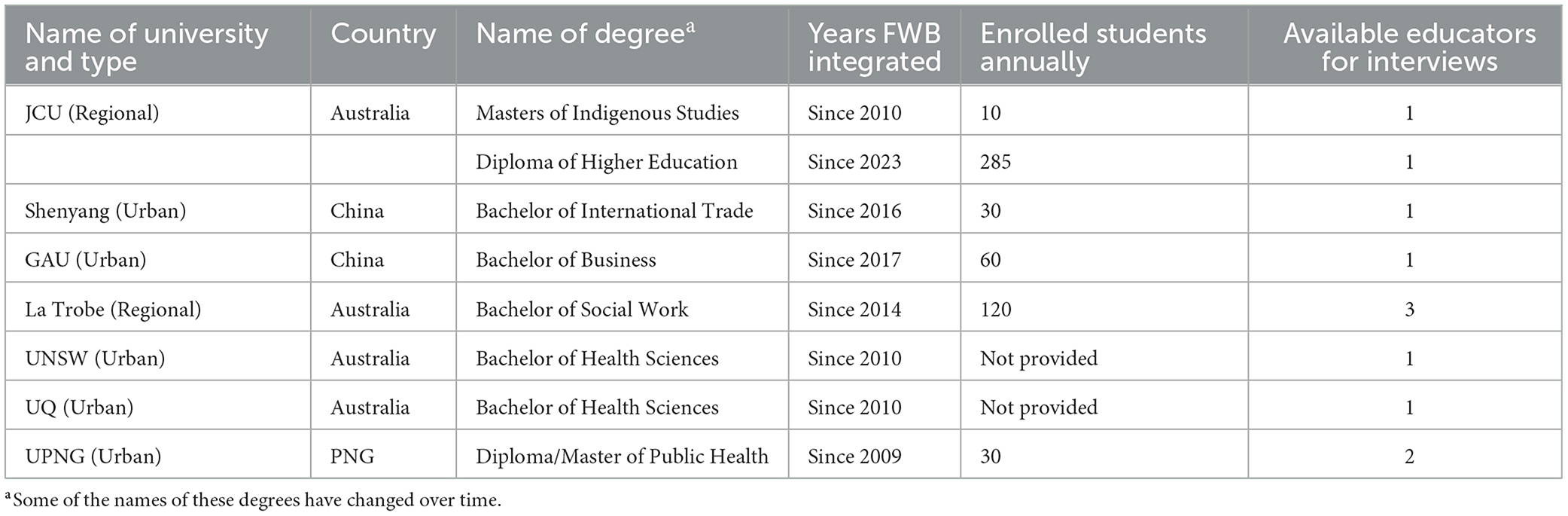

As shown in Table 2, the educators had used the FWB program in diploma courses (n = 2), bachelor degree courses (n = 5) or master's degree courses (n = 2) at four Australian universities: James Cook University (JCU), La Trobe University, the University of New South Wales (UNSW), and the University of Queensland (UQ); and three international universities: the University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG), and Chinese institutions, Shenyang University and Guangzhou Agricultural University (GAU).

The FWB program integration within these courses spanned from 2009 to 2023, reaching between 10 and 285 students annually from diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The widespread student engagement across diverse disciplines demonstrates the program's adaptability within university curricula in both regional and urban settings. While student perceptions of FWB program have been well-documented in previous research (see Sanders et al., 2024; Whiteside et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2019), this study focuses on the educators' experiences of integration, with one to three educators interviewed from each participating university. The educators were trained to deliver the FWB program within their curricula by (a) engaging in a 2-day intensive workshop covering program content and delivery methods; followed by (b) a year-long remote mentoring period focused on teaching preparation, program facilitation, and delivery process debriefing (Yan et al., 2019). Beyond this initial training period, educators continue to receive informal support through ongoing collaboration within the FWB research network. This peer-led network sustains engagement and fidelity to the program and represents a key enabler of continued practice.

Data collection and analysis

Individual interviews were used for data collection. The lead researcher conducted in-depth interviews with eight university educators. Interviews lasted between 30 and 82 min. Interviews were conducted in five phases, including follow-up interviews, adhering to constructivist grounded theory principles for initial coding and analysis (Birks and Mills, 2015; Charmaz, 2006, 2008, 2014). This process of conducting interviews in phases enabled the application of constant comparative analysis inherent in the simultaneous collection and analysis of data in grounded theory. Constant comparative analysis plays a crucial role in grounded theory by allowing researchers compare new findings against existing data to spot patterns and gaps (Birks and Mills, 2015). As grounded theorist researchers identify similarities and differences, they can determine what additional data they need to collect, otherwise known as theoretical sampling (Birks and Mills, 2015). Theoretical sampling strategically selects data sources—typically through interviews with people who have direct experience with the research topic (Birks and Mills, 2015). The approach helps researchers fill gaps in their developing theory by choosing participants who can provide missing pieces of information (Birks and Mills, 2015). Theoretical sampling enables the clarification of variations, properties, dimensions, and relationships among codes and categories (Ligita et al., 2020). Through this back-and-forth process of analysis and data collection, researchers develop rich conceptual categories that help explain the phenomenon in question (Birks and Mills, 2015). In this study, theoretical sampling guided the selection of educators to be interviewed next, to deepen an understanding of the phenomenon being explored. Based on this, the initial set of interviews began with two experienced educators who had extensively integrated FWB within their curricula, chosen for their deep understanding and potential to provide rich data for initial coding.

Data analysis began following the initial set of interviews. The lead researcher transcribed the interviews using the online transcription feature in Microsoft Word, then punctiliously reviewed the audio files to correct any transcription errors, ensuring line-by-line accuracy. A denaturalized transcription method was employed to remove idiosyncratic elements such as stutters and pauses to focus on the meanings and perceptions conveyed in the spoken words (Cameron, 2001; Oliver et al., 2005). This approach is consistent with the principles outlined by Oliver et al. (2005), who stress the importance of extracting meaning from transcripts in grounded theory research. Initially, NVivo qualitative analysis software was used for coding, but as analysis progressed, manual coding and categorization were employed to refine and identify the core category. Constant comparative analysis, memoing, and diagramming allowed for continuous refining of findings until theoretical saturation was reached. Authors met regularly during data collection and analysis to evaluate and discuss processes and emerging findings.

Quality of the research design

To ensure the validity of the study methods, we used triangulation to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings. Trustworthiness refers to the credibility and dependability of research findings, supported by evidence (Guion et al., 2011). For this study, we employed data triangulation, investigator triangulation, and methodological triangulation.

• Data triangulation involved synthesizing participants' ideas to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

• Investigator triangulation involved collaboration among the research team, who engaged deeply with the data to validate the emerging theory and narrative through personal reflexivity and rigorous epistemological scrutiny, which included constant debriefing and feedback.

• Methodological triangulation involved integrating literature reviews with grounded theorizing based on the educators' experiences.

This multifaceted approach helped ensure that our findings were robust, credible, and well-supported by the data.

Findings

The theoretical model identifies the core concern of “Getting people to experience it” as central to integrating the FWB program within university curricula. The model emphasizes that genuine understanding of the program's significance—both personally and professionally—can be achieved through direct experience. This experiential aspect emerged as a recurring theme among university educators who have integrated the FWB program into their courses, making it the linchpin of our theoretical framework:

People don't really know what it is until they do it. And they don't really know what it feels like and what the experience is until they have a taste of it. And then generally, once they've had that experience, they start to think about where they would fit it in the curriculum. And that it really is relevant to every curriculum – as professional development, personal wellbeing, relationship building. It ticks so many boxes, communication skills that often courses are running subjects on, and this often does it better. But people don't know that until they experience it. (Alexandra)

The purpose of this theoretical model is to explore how wellbeing initiatives can become integral to curricula, ensuring everyone has an opportunity to experience the program:

…the perspective changed from the teaching staff through exposure to the program, exposure to the notion that wellbeing should be integrated into their curricula and not an optional on the side. (Ada)

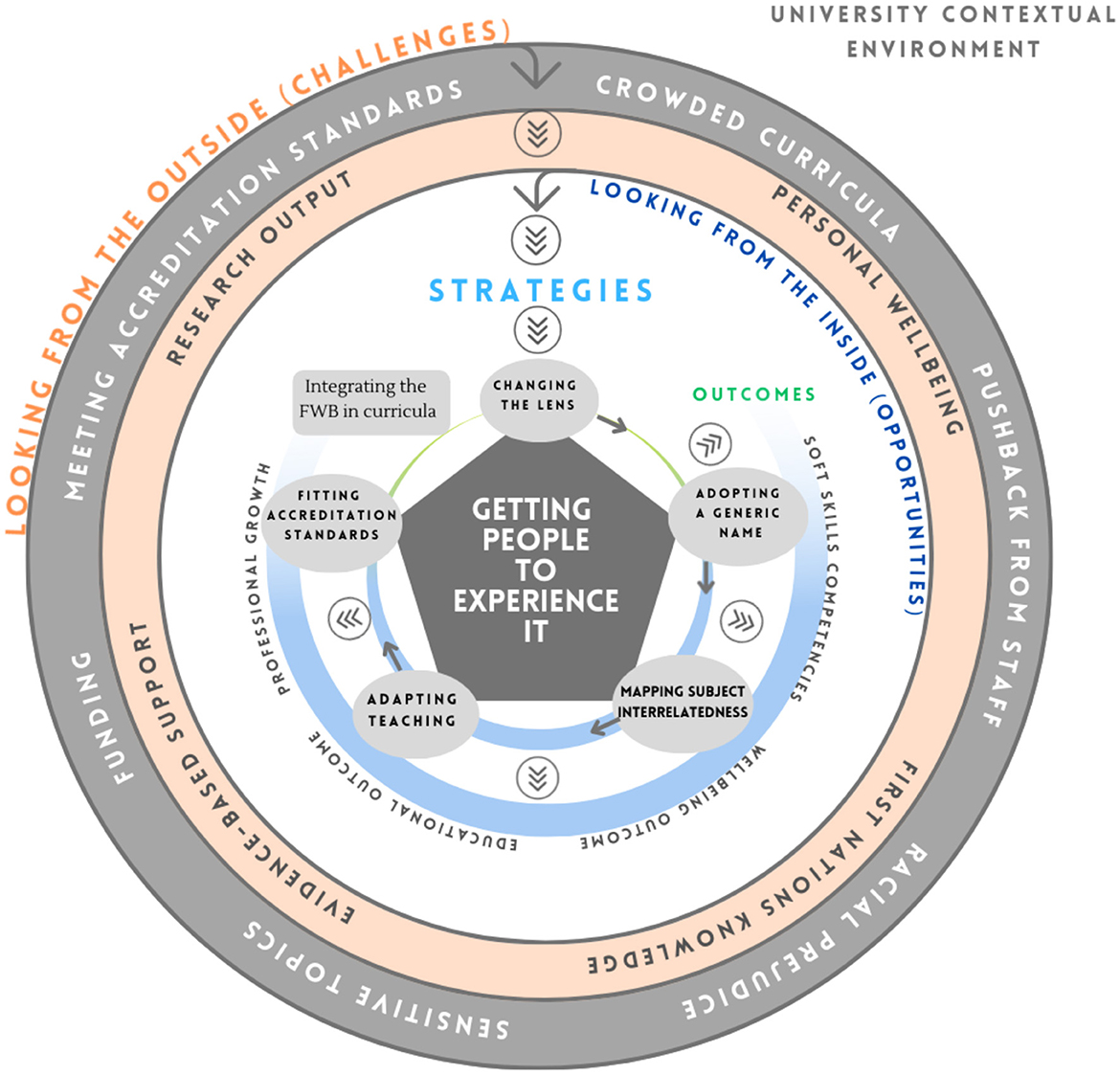

In this theoretical model, the categories of challenges, opportunities, strategies, and outcomes, along with their dimensional attributes as sub-categories, are mapped within the university contextual environment. This model is diagrammatically illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical model: how to integrate the FWB in curricula by “Getting people to experience it”.

University contextual environment

The theory emerged within the university context, where integrating the FWB program into curricula presented both challenges and opportunities. Typically, educators are more focused on the challenges of integrating new programs into established curricula. However, the opportunities, though requiring a more in-depth exploration, are crucial for encouraging adoption. An external perspective (looking from the outside) tends to emphasize the challenges, while an internal perspective (looking from the inside) reveals the opportunities. The vantage point from which educators view the program significantly influences their decision to integrate it into their curricula. Ultimately, both challenges and opportunities play a role in enabling people to experience the program. The primary challenges discussed include (a) crowded curricula, (b) pushback from staff, (c) racial prejudice, (d) sensitive topics, (e) funding, and (f) meeting accreditation standards.

Looking from the outside (challenges)

This category details the issues and barriers educators faced integrating the FWB program into curricula when seen from an external viewpoint. “Looking from the outside” was an in-vivo code gifted from an educator during an interview.

Crowded curricula

Educators identified the issue of overcrowded curricula is a significant barrier to introducing new initiatives. Many educators face difficulty integrating the FWB program within their already packed curricula. The limited time and space in existing programs discourage educators from adopting new additions that might disrupt their established curricula. Overcrowded curricula often give rise to other challenges, such as staff resistance, racial prejudice, sensitivity to topics, funding, and meeting accreditation standards:

The first barrier was just a crowded curriculum, and teachers don't really want to have to think about and learn something new too. I think in every discipline, the common barrier is that they all have a lot of things they have to cover in their curriculum…. There's a lot of things that the accreditation standards say you have to cover in a curriculum so it can be hard to find space for anything new. They're all just keeping up and they don't want to learn anything new or have to develop a new subject. Often sounds enormous too. (Alexandra)

Pushback from staff

Educators described how staff resistance often stems from dismissing the relevance of the FWB program to their curricula, citing its complexity and perceived inefficacy. Negative attitudes hinder the program's acceptance among some staff members. The program's relevance and alignment with curriculum were poorly understood:

The psychologist, who was the course coordinator, said, “Oh, it's not related to the curriculum.” And I said, “You didn't even know. You didn't even ask me how it's related. I could tell you how it's related.” But yes, I did have that problem with the psychologist. They couldn't see how it was related. It was not a good interaction because I'm sitting over public health and social work. They were sitting in psychology, and they needed FWB to understand it. The challenge there was really people looking from the outside, not recognizing how unique and valuable it is, and considering it silly. Across the board, that's our biggest problem. They think there's a wellbeing program, but then there's this wellbeing program, but to me, the FWB is the gold standard by far. (Maya)

Racial prejudice

Educators described how racism was a challenge to integrating the FWB program in university settings. Educators stated the FWB program, which is First Nations-developed and rooted in the Australian cultural context, was dismissed as irrelevant or not evidence-based, leading to condescending or even racist attitudes from certain non-First Nations individuals.

The FWB looked a bit wishy washy for them, I was just lucky I got that break in social work. And then sometimes wellbeing gets dropped off because it sounds a bit wishy washy, a bit soft. (Alexandra)

…there's a lot of people who are racist and redneck, and this was a required course, so a lot that came through that they don't like the name Indigenous. …They don't think they can learn anything from Aboriginal people. (Josephine)

Sensitive topics

Educators found that the sensitive nature of some topics covered in the FWB program may be considered too emotionally charged for academic settings, leading to concerns about their teachability in such settings. Topics such as basic human needs, beliefs and attitudes, relationships, crisis and emotions, and grief and loss were described by educators as challenging to address within a university curriculum:

A lot of the topics and other topics might challenge people, and they've got to make sense of things. They're just everyday topics like our beliefs and attitudes or our values or our relationships. Whether it was too risky to run this in the curriculum, maybe it is too sensitive. (Alexandra)

These concerns are twofold: the potential impact on students and the educators' perceived inadequacy in addressing these topics:

…a lack of confidence in educators themselves possibly, I think in delivering the content just because they didn't feel that they have a big enough knowledge base to be able to do it properly and effectively or to integrate it into subjects properly and effectively. (Ada)

Funding

Educators acknowledged financial resourcing was a major challenge, particularly in meeting accreditation standards. Funding issues impacted the program's initial integration. Moreover, there was reluctance to allocate funds for a program perceived as less essential than other mainstream academic subjects:

Faculty is always worried about funding, but also, student satisfaction. So, if you put a case to faculty, you might get some interest. But I think generally it'll be about the cost of it and also, they'll be worried about meeting accreditation standards like can you fit it in the curriculum. And it's hard to get the long-term funding to strengthen the evidence. (Alexandra)

…funding has always been a big issue. I guess the way that I used the FWB for our students in our course, funding didn't come into it because they were the students undertaking the subject. But you'd like to think that just having that framework might have taken people on to actually use that in their research, as they suggest that they would, and along with that, provide a basis for funding later, but they weren't at that stage at the time. (Nneka)

Meeting accreditation standards

Educators found that meeting accreditation standards can be challenging, as the curriculum must accord with these standards while maintaining academic quality to ensure the program's legitimacy and effectiveness:

But then you had to meet the accreditation standards, the academic quality standards and have enough readings in it. We were able to, as a discipline, develop our own curriculum as long as we met accreditation standards and quality teaching standards. (Alexandra)

Educators often face the challenge of convincing curriculum bodies of the merit of introducing new subjects like the FWB program. The difficulty lies in justifying the subject's introduction and providing case studies to prove its value. However, once the benefits are recognized, the program's adoption is usually significant:

We had to convince the curriculum body because everything has to be accredited. So, we had to put up a case for introducing the subject and it was fairly well accepted, but we had to actually justify why we wanted this in the program and given it was a bit different to the subjects we were using in the postgraduate studies. I guess the challenge was they were actually coming from that clinical basis, and also the fact that they hadn't actually done any wellbeing program as a participant, they're very much looking at it from a theoretical basis. (Nneka)

Looking from the inside (opportunities)

The challenges associated with the FWB program often arise from viewing it from an external perspective. However, there is a dynamic interplay where opportunities become evident when the program is viewed from the inside. Challenges and opportunities are interconnected, working together to encourage engagement with the program. Sometimes, opportunities are recognized alongside challenges, while at other times, challenges come first, but opportunities emerge upon closer examination. The perspective from which one views the program—whether external or internal—shapes this continuous flow between challenges and opportunities. Shifting from an external to an internal perspective reveals valuable opportunities, such as (a) personal wellbeing, (b) First Nations Knowledge, (c) evidence base support, and (d) research output.

Personal wellbeing

Educators believed integrating the FWB program into university curricula offers a unique opportunity to improve personal wellbeing, especially considering the escalating mental distress among students and the ongoing challenges of pandemic recovery. One educator noted its particular importance for students in health departments, who may otherwise overlook the significance of such a program within their studies:

You see across the profession that when you look at the data from dentists and vets, the mental health statistics is big for those professions – the health professions. Surely, they need this kind of content in their curriculum so that their students can look after themselves while they're studying and navigating life challenges. (Ada)

Previous attempts to enhance student wellbeing have often been seen as add-ons, failing to fully engage students. Educators acknowledged integrating the FWB program as a core part of the curriculum can address universally mental health needs among students more effectively:

Well, obviously the issue it addresses most is mental health in terms of needs, I think, and the beauty of it is that it's a universal mental health thing rather than people thinking they have mental issues. And I think it is partly too because students learn about each other. (Alexandra)

First Nations Knowledge

Integrating the First Nations FWB program into mainstream university curricula presents a significant opportunity to advance First Nations Knowledge within the higher education system. By introducing students to the FWB model developed by First Nations communities, educators saw how a more comprehensive understanding of First Nations people could be promoted within university curricula and the often-negative narratives surrounding their experiences challenged:

I suppose the other kind of motivation for us was to say we wanted our social workforce to be more inclusive of First Nations Bridge. And you know the thing that can happen in a social work course is that discussion about what's happening with First Nations people can become very problem-focused, all very gloomy. I suppose we felt, this is increasingly so clear, that there's so much that people who are not from First Nations can learn from First Nations people. And so, it was a really good way of saying right from the beginning of the course. Here you are. We're using this model. It's been led by groups of First Nations people. It's been refined. We think it's so terrific and so useful that we think everybody should be having this, and that's why it's in the course. (Josephine)

Evidence based support

The extensive evidence base of the FWB program, served as a compelling motivator for educators, challenging the perception that the program lacks empirical support. The FWB was regarded as a leading evidence-based, First Nations social and emotional wellbeing programs, potentially on an international scale:

In fact, in First Nations context, this is the most evidence-based or the most researched of any Australian First Nations social emotional wellbeing programs. I actually think it's probably one of the most internationally because I've done some literature reviews internationally. (Alexandra)

Research output

Educators discussed how integrating the FWB program provides significant research opportunities to enhance student wellbeing and learning while contributing to the implementation of First Nations Knowledge in higher education. Many saw the opportunity as a way of combining teaching with research publications, especially in academia where high teaching loads limit research time. Educators considered research has the potential to generate new funding opportunities and insights into First Nations Knowledge while improving the overall educational experience:

We've been doing some research. We've got two or three papers now that have provided student feedback as well with mental health surveys, qualitatively. (Alexandra)

Getting people to experience it (strategies)

Successfully integrating the FWB program into curricula requires thoughtful strategies to help educators overcome initial resistance by enabling them to experience the program firsthand. Prior exposure through participation, reading literature, and engaging with materials offered valuable insights, helped educators understand the program's relevance, and identify how its components can be integrated into their subjects by replacing redundant materials in their curricula with some of the aspects of the FWB program:

When I was integrating it into the subject myself, I had the advantage of having more insight into the program, having read the literature, been exposed to the project, done the session, and received all the provided materials. I could see where different parts would fit into my subject and recognize the relevance of the content. That helped me to replace what was no longer relevant in my subject with aspects of the FWB program. (Ada)

The strategies for “Getting people to experience it” include (a) changing the lens, (b) adopting a generic subject name, (c) mapping subject interrelatedness, (d) adapting teaching, and (e) fitting accreditation standards. This strategic framework is shaped by the experiences of educators who successfully integrated the FWB, outlining how they framed and utilized the program.

Changing the lens

Changing the lens involves encouraging educators to adopt a fresh perspective on the FWB program, moving beyond any preconceived notions about its First Nations origins. Some educators emphasized its history as a First Nations initiative focused on wellbeing and empowerment. One educator described how at her university a holistic lifespan approach was used to structure the sequence of the program delivery. This approach gradually shifted perspectives among students to be more receptive to the program's content:

We started with a three-day workshop, followed by a 13-week curriculum that really cemented the learnings from the workshop. Before diving into the curriculum, we wanted the students to change their perspective. The workshop was about shifting the lens through which they viewed the program, helping them to understand their emotions, strengths, and recognize strengths in others. (Maya)

Adopting a generic name

The strategic approach by educators of adopting a generic program name increased the relevance of the FWB program for students. Giving the program a more inclusive name made it more appealing and easier for students to connect it to their academic pursuits, thus enhancing accessibility:

I was concerned about how people would perceive this new subject called the FWB program. So, we renamed it to change perceptions, and as a result, we had a full complement of students signing up. (Nneka)

Mapping subject interrelatedness

Mapping FWB program connections within existing curriculum content was seen as crucial for successful integration. Educators impressed the relevance of the FWB program by identifying links between subjects, recognizing how these subjects play a role in students' educational journeys, and understanding how the FWB program is situated within broader course objectives. Mapping exercises show how the FWB program can be seamlessly integrated into curricula, meeting subject demands while enhancing students' overall learning experiences:

The benefit of the new curriculum was that it allowed for much more mapping of how subjects were interrelated and how they served as steppingstones for each year. It was carefully articulated to ensure that the subject attributes aligned with the overall course. (Alexandra)

Adapting teaching

For educators, adapting teaching methods involves addressing challenges such as large class sizes, time constraints, diverse age groups among students, group dynamics, inclusivity, and the handling of sensitive topics:

One of the main challenges is that the class size is too large, making it difficult for students to engage in discussions and share their ideas. Due to the large number of students and limited class time, I combine the course content with the textbook, but I can't engage with the students as much as I'd like. (Olivia)

Strategies include dividing large classes into smaller groups, mixing different age groups to foster dynamic knowledge exchange, reinforcing group agreements which are developed at the outset of the program, employing differentiated instruction, and addressing diverse student needs through contextualized teaching methods. Appropriately modifying sensitive FWB topics is crucial, as they can evoke emotional responses related to students' personal experiences:

I did have in a couple of times, where students have asked not to participate in a particular topic because it's been a little bit close to home. For instance, one mum whose daughter had committed suicide, and she didn't want to come to one particular week. (Emily)

Building a safe environment that emphasizes voluntary sharing and support is essential:

And we do have in the group of women, you don't have to share anything, you don't have to tell your deepest secret. And we really try to reinforce that. (Alexandra)

However, managing sensitive topics remains challenging for some educators:

Another thing is when it comes to sensitive topics, the content that was on grief. And that's where one of the lecturers said, I'm not comfortable talking about this. I don't feel like I can talk about this in my classroom, or I don't know how it's going to affect students. (Ada)

Cultural factors can influence perceptions of sensitivity, requiring clarification around concepts like spirituality:

It's not easy to use FWB in my class because of most of the topics are sensitive to people themselves. In Chinese culture, …I dare not to talk about topics related to emotions, relationship, belief and so on, …in public, as in a class. (Olivia)

Spirituality is traditionally very low among students. I think they're far too afraid to admit that they have any. But after in that one unit with the FWB program, it just went way up. And it's not that they all became spiritual. Question is about whether you recognize your spirituality. Whether you see it in yourself. And because they were allowed to redefine what spirituality is, it's not going to church. It's actually your connection. And the way, that just went through the roof in only the FWB containing unit, … It's just so huge. (Maya)

Measures such as group agreements, personal reflections, gradual sharing, and counseling support are essential for maintaining emotional wellbeing:

But you know little things like doing the group agreement. At the start of the class, the start of the whole course. It was a stop and pause moment for all of the students in that classroom to articulate what they wanted from their class as a community. I suppose, that's one of the things that I think happened as a result of taking that starting point. (Ada)

Fitting accreditation standards

Fitting accreditation standards involves three key strategies: fulfilling curriculum requirements, creating practical assessments, and ensuring student satisfaction. Tailoring FWB program activities and assessments with required knowledge and skills helps fulfill curriculum demands. Educators found that the program was well fitted with their subject needs such as encouraging reflective practices, enhancing group dynamics, and promoting core values of their discipline:

It aligns really clearly with social work values, focusing on group work, communication, essential listening skills, and reflection. It fits beautifully. (Emily)

Creating practical assessments allows educators to evaluate the FWB program's approach to developing soft skills while meeting accreditation standards. Common methods include having students run programs themselves and write reflective reports, fostering a sense of ownership and practical application of skills. Reflective journals, personal reflections, and analyzing program components through the lens of social determinants of health and work experiences are also utilized.

We saw that as a way of empowering students to think differently and to bring that different thinking to their practice. We asked them to do our personal reflections on the different subjects, about grief and loss, and how that actually played out in their own lives, but also how they could use that to assists their clients and families that are working to overcome grief and loss. In essence, they had to take components of the FWB and analyse those in terms of the social determinants of health and their own work. And then the final report had a personal reflection in it, plus a learning reflection of the actual subject itself and how they would see applying that in their own situation from a learning perspective. So, it had three components to it. (Nneka)

Ensuring student satisfaction is crucial for integrating the FWB into the curriculum while meeting accreditation standards. This involves gathering student feedback through online journals, assessment tools, and metrics like informal class feedback, the Growth and Empowerment Measure (GEM)1 tool, and formal evaluations. These insights help inform program improvements and establish the significance of feedback in the university's evaluation process. By collecting and analyzing feedback, educators can ensure the program meets accreditation standards and student satisfaction, enhancing its reputation as a valuable curriculum addition:

Through student feedback each year, we're required by the university to look at that and write a report on what we're going to do about it. And then we do informal feedback just within classes too and ask them how they're finding it and what do they like, and what they don't like? What would you change? Those sorts of questions you can have informally with students or with the student group, and then you do get it more formally through the student feedback on teaching processes. (Alexandra)

The GEM was deliberately developed to be part of the process of healing and empowerment. So, it has a dual purpose to measure, but also to help in the sense of, oh well, I'm here, but I could be there or to see a journey. (Maya)

These strategies aim to seamlessly integrate the FWB program into university curricula while meeting rigorous academic requirements and promoting student growth and wellbeing.

Outcomes

The FWB program, seamlessly integrated into university curricula, proved to be a transformative force, yielding remarkable outcomes for both students and educators. The innovative approach of the program enhanced (a) soft skills competencies, (b) wellbeing outcome, (c) educational outcomes, and (d) professional growth.

Soft skills competencies

Educators described how the collaborative nature of the FWB program created a nurturing environment for developing essential soft skills such as communication, teamwork, leadership, resilience, and emotional intelligence. Through group work, reflective journaling, and public speaking opportunities, students honed their problem-solving, self-reflection, and interpersonal abilities. The program also promoted a sense of community and belonging, bridging generational gaps, and empowering students to navigate both personal and professional domains with empathy and insight:

The FWB program helps students learn to work in teams, better understand themselves, become more confident, discover the beauty of life, deeply understand interpersonal relationships, deal with conflicts and emotions, establish correct beliefs, maintain a positive attitude, and better plan for themselves. (Isabella)

Educators similarly benefitted from the FWB program, reporting substantial improvements in teamwork, communication, empowerment, self-awareness, resilience, relationship-building, problem-solving, critical reflection, confidence, and compassion. The program's innovative and evidence-based teaching methods provided techniques for educators to address conflicts and foster equality and independence in both personal and professional relationships:

Before I encountered FWB, I tended to focus on problems in myself and those around me. But after exploring the “Basic Human Qualities” module, I realized that these qualities protect each individual. This realization led me to change my teaching method and attitude, reducing criticism of students, my relatives, and those around me. (Olivia)

Wellbeing outcome

The FWB program had a profound impact on the personal wellbeing of both students and educators. Educators told how students would describe the FWB sessions as the highlight of their week, emphasizing the program's value in addressing holistic needs. Practices including meditation and life-enhancing activities led to personal growth, improved interactions with partners and children, and a heightened sense of empowerment:

It was really good for student wellbeing. Some students said, “This is what I look forward to all week.” Others mentioned in evaluations that they planned to meditate more often or engage in activities that enhance their lives. (Josephine)

Educators acknowledged the program also addressed student mental health through the curriculum, providing an alternative to traditional counseling services, which some students avoid:

By integrating FWB into the curriculum, we were able to address student mental health in a way that didn't require them to seek out counseling services. (Alexandra)

For educators, the FWB program was a powerful catalyst for enhancing personal wellbeing. The structured reflection process provided a valuable framework for learning from experiences, while teachings on handling emotions and resolving conflicts reduced anxiety and fostered peace and inclusivity. Educators reported increased happiness, improved confidence, and more harmonious family dynamics:

It has improved my friendships and helped me to communicate from the heart, rather than from a place of exchange. It has encouraged me to follow my beliefs, do things that make the world more beautiful, and be satisfied with my basic human needs. Overall, it has encouraged me to be happy and pursue a healthy lifestyle. (Olivia)

I consider myself a confident, well-educated person. But going through the FWB experience, really thinking about my life and how I deal with challenges, has made me a better person. (Nneka)

Educational outcome

Educators recognized the integration of the FWB program into curricula enhanced educational outcomes for students, including boosting their academic achievements, preparing them for future careers, and elevating their understanding of First Nations Knowledge. Educators reported qualitative feedback indicated a positive correlation between the wellbeing fostered by the program and academic success. Students reported increased self-awareness, confidence, and improved stress management skills, enabling them to handle the demands of quotidian life more effectively and engage more fully with their university studies:

Qualitatively, students felt they gained more self-awareness and confidence, managed daily stresses better, and appreciated the strengthened relationships with other students. They also recognized that they were gaining knowledge relevant to their future professional lives, which helped them engage more fully with their university studies. (Alexandra)

Educators stated the FWB program also prepared students for their future careers, particularly in fields like social work. Through practical components such as counseling and group work, students gained hands-on experience that effectively equips them for the challenges and demands of their professional degrees. The program's emphasis on self-awareness and its relevance to career preparation enhanced student engagement and interest in their educational experiences:

I think it really resonates with students, both personally and professionally. We get feedback from social work students who see the program as their first real taste of what social work entails, helping them decide if it's the career they want to pursue. (Emily)

Moreover, the FWB program was seen to advanced student understanding of First Nations Knowledge, allowing them to engage with content in a respectful and enriching manner. The positive framing of First Nations Knowledge contributed to a more inclusive and empowering learning environment, enabling First Nations students to participate with pride and prompting shifts in perspectives among non-First Nations students:

In an evaluation, a couple of First Nation students said, ‘What a relief to come to a class where there were no negative perceptions of First Nations people. Everything was framed positively, and I could just participate.' That was a really positive outcome. (Josephine)

Professional growth

The FWB program also facilitated professional advancement for educators by providing opportunities to contribute significantly to research in First Nations Knowledge. Their experiences with the program enriched the knowledge base through publications and evidence-based studies, raising awareness and promoting the adoption of the FWB program across educational institutions, public health domains, and various organizations:

The publications have helped. The more people write about it and publish, the more awareness spreads, leading to greater adoption. Personal communication and direct experience with the program also played a crucial role in its uptake. (Alexandra)

In addition, the integration of the FWB program catalyzed a pedagogical shift, with educators emphasizing the recognition of complexity and the interconnectedness of all aspects of life:

The FWB program encourages thinking in complexity. I try to teach my students that the parts don't add up to the whole, and you need to consider all aspects to see the complete picture. This approach aligns with my background as an analytical scientist, where understanding the interconnectedness of everything is crucial. (Maya)

The program's intersubjective nature and emphasis on personal stories influenced educator's teaching methods, fostering a collaborative atmosphere where students are viewed as experts in their own right:

My teaching style always involves learning from students, but with the FWB program, you really embrace the idea that students are the experts in the room. They're sharing personal experiences, and we're all experts of ourselves. (Emily)

The participatory social learning method inherent in the FWB approach has been adopted by some educators in teaching other courses, encouraging students to express themselves freely and generate new ideas.

The teaching method of FWB, namely “participatory social learning method,” has opened my eyes. This method… let people recall their previous cognition and experience through brainstorming, …to explore creative solutions to problems. Through the experience of using FWB program, I use the method of “brainstorming” in teaching other courses. I feel that people will speak freely, think actively, and fully express their opinions, often generating new ideas or stimulating innovative ideas. (Isabella)

Discussion

“Getting people to experience it” emerged as the central theme in this grounded theory study, encapsulating the core process of integrating the FWB program into university curricula. The theory, developed from the experiences of educators who integrated the FWB program across Australian and international universities, details the challenges, opportunities, strategies, and outcomes associated with this integration.

Initially, educators approached the FWB program with trepidation but later recognized its relevance after experiencing the sessions. The integration process revealed several challenges for educators, including overcrowded curricula, staff resistance, instances of racial prejudice, the need to address sensitive topics, securing funding, and meeting accreditation requirements. Overcrowded curricula emerged as the root cause of many subsequent challenges. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2020, p. 11), highlighted critical questions that curriculum designers often face regarding overcrowded curricula, such as: “Is it real or perceived?”; “How can we accommodate new demands from society in an already crowded curriculum?”; and “How can we ensure breadth and depth of learning that are both achievable within the time allocated in a curriculum?”.

The challenges originating from overcrowded curricula reflect a perspective of “looking from the outside.” They are particularly pronounced for wellbeing initiatives designed as soft skills approaches, which often receive lower priority in educational settings that emphasize hard skill acquisition. Furthermore, these challenges are exacerbated by the influence of neoliberalism in educational institutions. George Monbiot, in an Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Late Night Podcast hosted by Adams (2024), discusses how neoliberalism has led academic institutions to follow neoliberal trends. Consequently, curricula are being shaped by neoliberal ideologies (Maistry, 2020). To this end, Giroux (2002, p. 435) describes universities as “training grounds for corporate berths,” while Savage (2017, p. 150) notes that educational institutions have become “a site for building human capital and contributing to economic productivity, from the early childhood years, right through to the tertiary level.”

Despite these challenges, opportunities exist for educators to substantiate the academic value of the FWB program through evidence-based outcome reports. Hickey (2021) argues that hard skills alone are insufficient to prepare students for today's complex world. When students perceive their learning as purposeful and relevant to real-life scenarios, they are more motivated to develop the intended competencies (Eccles and Midgley, 1989). The OECD (2020) proposal that affiliating curricula with real-world demands can increase students' sense of relevance is supported by research reporting that integrating futures education, soft skills, and wellbeing initiatives into curricula, while demonstrating their real-world relevance, is crucial for enhancing student wellbeing (Paynter, 2018; Sanders et al., 2024; Whiteside et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2019).

The transition of educators and students from initial apprehension to appreciation of the FWB program is emblematic of Ricoeur's (1967) concept of moving from first to second epistemic naiveté. This experiential transition begins with an uncritical, pre-critical acceptance (first naiveté), progresses through a critical deconstruction phase (potentially leading to a “desert of criticism”), and culminates in a post-critical reconstruction stage (second naiveté). This final stage, the second epistemic naiveté, brings a more nuanced, reflective, and symbolic understanding, revealing newfound depth and complexity in familiar concepts that once seemed black and white, now showing different hues of colors (Ricoeur, 1967).

The process of transition conceived by Ricoeur aligns with Martin Nakata (2002, 2007) concept of the “cultural interface” where First Nations and Western knowledge systems intersect. The second naiveté approach views the cultural interface as a space of tension and negotiation, yet one that offers opportunities for open, exploratory, and creative inquiry. The approach challenges the pre-critical oversimplification of First Nations and Western knowledge as separate entities, emerging through critical deconstruction as a post-critical understanding that welcomes the creative possibilities of this intercultural space, allowing for deeper analysis and novel solutions. This process enables educators to develop curricula that fosters new teaching approaches and supports First Nations self-determination through education and research (Hart et al., 2012; Horsthemke, 2021).

From the perspective of “looking from the inside” afforded by the second naiveté within the cultural interface, various opportunities emerge. These include improving personal wellbeing, enhancing First Nations Knowledge thresholds, leveraging the program's evidence-based support, and facilitating research output. As a First Nations-developed wellbeing program with a strong evidence base and numerous publications, the FWB not only increases the visibility of First Nations Knowledge within mainstream curricula, as Nakata (2002) argues, but also represents a critical step toward national improvement in Australia by fostering a more nuanced understanding of First Nations people (The University of Melbourne, 2024). This approach challenges prevailing negative narratives about First Nations Knowledge and aligns with literature emphasizing the importance of inclusivity and recognizing the transformative potential of First Nations Knowledge in education (Battiste, 1998, 2018; Carey and Prince, 2015; Jones et al., 2024; Nakata, 2001, 2002, 2007; Nakata et al., 2012).

The FWB program, with its strong evidence base and dual focus on technical and soft skills, exemplifies both an evidence-based approach and an educationally desirable program as advocated by Biesta (2007). The holistic approach of FWB program bridges the unhealthy methodological debates within disciplines, particularly those pitting quantitative against qualitative research (Tsey, 2015). Emerging from the need of First Nations Australians to regain control over their lives in the face of ongoing colonial impacts (McCalman et al., 2012; Nolan et al., 2024), the program necessitates continuous democratic deliberation in education, evident in the strategies of its operationalization.

Strategies for operationalizing FWB in curricula include educators changing the lens through which the program is viewed, using generic subject names to broaden appeal, mapping connections across subjects, adapting teaching methods to integrate FWB principles, and ensuring the program fits accreditation standards. By changing the lens, educators confront and dispel prejudices, allowing individuals to view the program from a strength-based approach. This is consistent with the notion that strengths-based approaches to research rather than deficits, foster a sense of empowerment (McEwan et al., 2010; Tsey, 2010, 2019; Whiteside et al., 2006).

Adopting a more generalized name helps educators associate the program with academic goals and enhance its accessibility. This is supported by literature on adaptive strategies regarding culturally responsive education and the integration of First Nations content into mainstream curricula, making it more approachable for non-First Nations students while preserving its core values (Castagno and Brayboy, 2008; Gay, 2018; Sleeter, 2011). Mapping subject interrelatedness promotes how the FWB program seamlessly integrates into the curriculum, contributing to students' holistic development. These outcomes are consistent with those of Oliver and Jorre de St Jorre (2018), who argue all education providers should make graduate attributes/soft skills more visible within the academic framework.

Adapting teaching pedagogy involves educators addressing challenges such as managing diverse class sizes, time constraints, and student age ranges; navigating complex group dynamics; ensuring inclusive lesson differentiation; and modifying sensitive topics. These approaches are supported by a broad spectrum of educational literature, from foundational works on differentiated instruction (Tomlinson, 2014; Tomlinson and Imbeau, 2023), effective teaching strategies (Biggs et al., 2022; Hattie, 2008), and multicultural education (Banks, 2015; Banks and Banks, 2019), to research on evidence-based teaching practices (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020), higher education curriculum development (Bovill and Woolmer, 2019), and inclusive pedagogy (Arday et al., 2021).

The integration strategies of the FWB program are further supported by research on classroom group work (Blatchford et al., 2003), facilitating discussions on sensitive topics and establishing ground rules (Brookfield and Preskill, 2012)—exemplified through the “group agreement” of the FWB program, enhancing adult learning motivation (Wlodkowski and Ginsberg, 2017), and adaptive teaching strategies (Rapanta et al., 2020). These adaptive teaching practices are to ensure that students engage with the FWB program meaningfully. According to Kahu and Nelson (2018), student engagement significantly improves when teaching methods match individual learning preferences and course content reflects personal interests. This is crucial in preparing students for successful entry into their professional careers (Brennan and Dempsey, 2018).

Furthermore, the ability to adapt teaching approaches highlights the importance of pedagogy, which Sankey (2021) defines as the art of teaching or the science of how students learn. Biesta (2020, p. 91) emphasizes that, “…the point of education is never that students simply learn—they can do that anywhere, including, nowadays, on the Internet—but that they learn something, that they learn it for a reason, and that they learn it from someone.” This underscores the critical role of adept educators in shaping students' educational journeys through differentiated pedagogy. Tomlinson (2014), describes educators in differentiated classrooms as flexible time managers who employ various instructional strategies, partnering with students to shape content and learning environments. These educators function as diagnosticians, prescribing optimal instruction based on their content knowledge and understanding of student progress. Tomlinson (2014) likens these educators to artists who skillfully address individual student needs, eschewing standardized lessons in favor of personalized approaches that prioritize student learning and satisfaction over merely covering curriculum content. This approach to differentiation subscribes closely to the FWB program principles that emphasize personalized learning experiences and individual strength development based on a participatory social learning approach (Tsey et al., 2005), anchored in the “Socratic Way” (see Assiter, 2013; Orih, 2022), or “Both Ways” learning approach in First Nations parlance (see Hall and Wilkes, 2015).

Ensuring the FWB program meets accreditation standards is crucial, given that the process significantly influences what is taught, how it is taught, and the quality of assessment (Eaton, 2015; Gupta et al., 2021; Kafaji, 2020; Medland, 2019; Reddy et al., 2023). Wood et al. (2019) discuss the pivotal role of accreditation in shaping curricula, noting that it often dictates educational priorities and outcomes. The accreditation process requires educators provide evidence of how programs meet institutional goals and learning outcomes, impacting students' learning experiences (Kafaji, 2020; Reddy et al., 2022, 2024; Wood et al., 2019). This is particularly relevant for FWB program, which needs to assert how its soft skills contribute to the overall educational objectives and professional readiness of graduates (Brennan and Dempsey, 2018; Oliver and Jorre de St Jorre, 2018; Orih et al., 2024).

The FWB program demonstrated transformative outcomes for both students and educators, a finding adding to the current literature on the importance of soft skills and wellbeing in education (Brennan and Dempsey, 2018; Cinque, 2016, 2021; Oliver and Jorre de St Jorre, 2018; Orih et al., 2024; Succi and Canovi, 2020; Whiteside et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2019). The program has also significantly boosted personal wellbeing for students, resonating with research on integrating wellbeing programs within curricula (Sanders et al., 2024; Travia et al., 2022; Whiteside et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2019; Zhu and Shek, 2021). For educators, this finding resonates with those of Jennings et al. (2019) who reported sustained enhancements in social and emotional competence and wellbeing of educators, as well as Almaguer-Botero et al. (2023), who noted improved job satisfaction of educators following participation in wellbeing programs.

The study's findings have significant practical implications for education, advocating for a continued holistic approach that equips students with both hard and soft skills to navigate life's complexities (Orih et al., 2024). The findings challenge the current neoliberal trend of commercializing education and reducing it to a mere “production” process that prioritizes technical skills for job acquisition at the expense of crucial soft skills, as decried by Biesta (2015) and the contemporary philosopher, Alain de Botton (SBS D FORUM, 2013). By integrating programs like FWB into core curricula, educational institutions can foster a balanced development of hard and soft skills, answering the call for a return to the fundamental purpose of education and countering the neoliberal emphasis on hard skills acquisition alone (Biesta, 2015, 2020, 2021).

Implementing the study's theoretical model, even in subjects traditionally focused on hard skills, can bridge the gap between technical proficiency and the soft skills necessary for long-term career success. As a model for integrating wellbeing into curricula, it addresses universal wellbeing for students with mental health issues who may not seek formal assistance or disclose their conditions (McKendrick-Calder and Choate, 2024). This approach not only optimizes students' overall experience and mental health but also provides a strategy for educators to incorporate wellbeing support without overextending themselves or feeling strained by added workload and self-doubt. It further advances the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals, especially Goal 3, which aims to improve health and wellbeing for people of all ages worldwide (Halkos and Gkampoura, 2021).

In sum, the process of integrating the FWB program into university curricula involves navigating challenges while leveraging opportunities to accentuate the program's academic value. Through thoughtful use of strategies enabling program experience, educators can effectively operationalize the FWB program. This process, informed by grounded theory and the perspectives of experienced educators, testified to the importance of fostering a nuanced understanding of First Nations Knowledge and wellbeing in higher education, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive and holistic educational experience for all students.

Strengths, limitations, and direction for future research

The major strength of this study lies in developing a practical theoretical model to help busy educators integrate First Nations wellbeing programs into their curricula, based on input from experienced university educators. The study's participant profile supports this argument because of the participants' extensive academic experience, with all educators having taught for over 6 years and five, having more than a decade of teaching experience, with no early career researcher or educator involved. The high proportion of senior academics (five Associate Professors/Professors) suggests participants had substantial expertise and decision-making authority in curriculum development. All participants holding combined teaching and research roles indicates they could provide insights from both pedagogical and scholarly perspectives. The number of non-First Nations participants (7 out of 8) is a testament to how the program has gained recognition, support, and appreciated beyond First Nations communities, which helps promote its broader adoption in university curricula.