- 1Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 2Population, Policy and Practice Department, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 3Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Background: One in five school-aged children and young people (CYP) in England are identified as having a special educational need or disability (SEND) requiring additional support. Despite growing numbers of pupils receiving interventions to support the broad areas of need outlined in government guidelines, little research has asked CYP directly about their experiences of securing and receiving SEND provision or how effective they think the support was for their health and education outcomes. We answered these questions through one-to-one interviews with CYP with SEND.

Methods: We used a semi-structured interview format, structured with a timeline to help participants recount their whole experience. We developed and piloted our approach with a CYP's advisory group. All data collectors were trained by a senior research team. We recruited participants via an online survey about SEND provision in England. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymized before thematic analysis, complemented by narrative portraiture for selected cases.

Results: We interviewed 15 CYP aged 13–25 years (12 online, 3 in-person). Respondents had a range of SEND types, most commonly autism. Thematic analysis identified four themes that acted as enablers and barriers to SEND provision: (1) education-based factors; (2) the extent that provision matched need; (3) timing of provision; and (4) relationships, communication and decision-making. Mental health and attainment were the most common outcomes discussed. Our narrative portraitures illustrate the large number and variety of influences on the quality of SEND provision at critical educational stages, which affected their educational, mental health and life trajectories.

Conclusion: Late identification of SEND, and poor responsiveness of school staff in implementing provision had detrimental consequences for CYP's outcomes. Listening to them about their needs, providing prompt assessments and implementing simple tailored approaches can be hugely beneficial. The ability of CYP and families to advocate for support is a key influence over the quality of provision. Our study has policy implications, including fairer formats for academic assessment and a call for additional SEND training and toolkits for teachers. Further attention must be paid to ensure the needs of all CYP are identified and met, including those who cannot advocate for themselves.

1 Introduction

Nearly one-in-five pupils attending state-funded, independent or hospital schools in England were identified as having special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) in the academic year 2023/24 (UK Government, 2024b). According to the UK government's definition, children and young people (CYP) with SEND experience significantly greater difficulty in learning than their same age peers, and/or have a disability that prevents or hinders their use of standard facilities in mainstream educational settings (Department for Education Department of Health and Social Care, 2015).

The SEND system underwent substantial reform in 2014.1 The then government's intention for CYP with SEND was to “achieve well in their early years, at school and in college, and lead happy and fulfilled lives” (Department for Education Department of Health and Social Care, 2015). Major policy changes included (but were not limited to) directly involving children and families in discussions and decision-making about their support needs and the introduction of legally-binding Education Health and Care Plans (EHCPs). 4.8% of pupils in England have an EHCP, and the remainder of pupils identified with SEND (13.6%) receive school-led “Special Educational Needs (SEN) support” (UK Government, 2024b). EHCPs are a single document specifying a CYP's support plan, based on input from health, social care and education professionals, CYP and families, and outline desired health, education and social outcomes for CYP. Parents/carers and CYP were given the right of appeal against local authorities (LAs) in relation to EHCPs: e.g., if an LA refused to conduct an assessment for an EHCP, if a CYP did not receive the support outlined in their plan or if their plan was not annually reviewed, or if CYP or families disagreed with a plan's contents.

There is wide variation in complexity, severity, and duration of SEND, with differing support requirements and statutory expectations of schools and LAs to ensure CYP's needs are met (see text footnote 1).2 CYP with lower support needs (i.e., requiring less assistance with school tasks and fewer specialist interventions, such as small group learning support) should be offered school-led “SEN support,” which is generally funded from schools' annual budgets (UK Government, 2024a), makes use of a “ordinarily available” provision to meet needs (Department for Education Department of Health and Social Care, 2015), and where “reasonable adjustments” should be made to promote equal benefit from and prevent discrimination in accessing resources (see text footnote 2). If needs cannot be met with SEN support, families and schools may apply for a statutory EHCP assessment subject to approval by LAs, which might cover the costs of a one-to-one teaching assistant (TA) for example (Department for Education Department of Health and Social Care, 2015).

Despite the positive intentions of the 2014 SEND reforms to improve provision, there is growing evidence that legislation is being poorly implemented at multiple levels. For example, the majority of LAs are underperforming and overspending in relation to SEND (National Audit Office, 2019, 2024), and there are low levels of teacher self-efficacy in supporting additional needs in mainstream classrooms (Coates et al., 2020). The system does not provide good value for money (National Audit Office, 2024), and families report the process of securing support as adversarial and overly complex (National Audit Office, 2019), requiring strong advocacy skills with a vast array of professionals, including in judicial settings (Keville et al., 2024; Starkie, 2024).

Further proposed reforms in a 2022 Green Paper (Department for Education DoHaSC, 2022) and 2023 SEND and Alternative Provision Improvement Plan (Department for Education, 2023) were controversial and have yet to be fully implemented. There remains a lack of clarity about how new initiatives will improve the experiences of system users or offer financial sustainability (National Audit Office, 2024). The SEND Improvement Plan (Department for Education, 2023) does not address significant workforce challenges affecting the SEND system or promote timely identification of SEN according to the government's spending watchdog (National Audit Office, 2024). The plan also lacks clarity around measuring progress or declines in provision, costs, or children's outcomes. There is further uncertainty about the future costs of the system, partly due to unknown numbers of children requiring specialist settings, and lack of available specialist settings, which tend to cost much more than mainstream and are working over capacity. Despite the government aim for mainstream schools to be more inclusive, reducing the need for specialist settings, there is currently limited information about how mainstream schools could achieve this, and few incentives for them to make changes (National Audit Office, 2024). The results from piloting the “Change Programme” of 2022/23 reforms are still awaited,3 and the new government appear to be considering further reform, with a new enquiry into the “SEND crisis” (UK Parliament, 2025), an upcoming Children's Wellbeing Bill expected to emphasize inclusive education with mainstream schools as the preferred setting for all CYP (UK Parliament, 2024) and a Curriculum and Assessment Review will examine educational attainment, including for pupils with SEND (Department for Education, 2024).

The extent to which SEND-related support in educational settings improves CYP's health and educational outcomes is currently poorly understood (Zylbersztejn et al., 2023). Whilst some studies have considered CYP's experiences of SEND provision, many originate from the gray literature, such as LA-led surveys about the Local Offer for SEND (i.e., the services that are available locally). These surveys are mandated in the SEND Code of Practice (Department for Education Department of Health and Social Care, 2015), but without corresponding guidance about how to conduct and draw valid conclusions from research. In our view these studies tend to be poor quality because they lack rigor in their design, reporting and interpretation. The Children's Commissioner's Big Ask Survey (Children's Commissioner, 2021) found that respondents with SEND were more likely to report that education was important for their future plans, and those who received the right support “quickly and locally” were happier than the overall survey sample. In a further meeting, four CYP criticized vague non-individualized EHCPs, SEND provision arriving too late in education to improve outcomes, and lack of access to technology and equipment to meet their needs. They also lamented the lack of support to get into further education and employment, as well as the lack of ambition for them by the various professionals involved in their support (Children's Commissioner, 2023).

In the peer-reviewed literature, there have been several studies of general educational experiences of CYP with SEND [such as school belonging (Porter and Ingram, 2021)]. We are aware of two peer-reviewed studies directly exploring experiences of SEND provision in England, but were narrowly focused on how CYPs views were included in EHCPs. Gaona et al. (2020), used qualitative methods to examine EHCPs of 12 CYP with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Gaona et al., 2020). They found pupils aspired for greater autonomy especially in terms of self-care, domestic life, mobility, and enhanced participation at home, school and in their communities; EHCP analysis also identified discrepancies in EHCPs across LAs suggesting a need for more specific guidelines to develop holistic and person-centered plans. Palikara et al. (2018), analyzed how the views of 184 pupils from mainstream and special schools in Greater London were captured in their EHCPs (Palikara et al., 2018). They too found substantial LA-level variability—specifically in the processes and methods used to elicit CYP's views.

Two further studies from England include incidental CYP reports about their provision, tangential to the studies' main aims. Chatzitheochari and Butler-Rees (2023) explored the intersection of social class, SEND type and stigma amongst final year secondary school students who were autistic, dyslexic or physically disabled. Though not the primary focus of the study, CYP reported mixed experiences about their SEND-related support. Autistic students stressed the importance of having a quiet space to retreat to at school to prevent “meltdowns” and several reported stigmatizing encounters with teachers. Some teachers did not understand pupils' SEND, including one student with epilepsy who was wrongly labeled as disruptive and put into isolation. Satisfaction with provision was linked to social class: disadvantaged pupils were less happy with their in-school support and placements, whereas more affluent children attended more inclusive environments. An in-depth study (Tomlinson et al., 2022) of three academically able autistic girls attending a mainstream school in England known for its good practice around accommodating autistic pupils, and which the participants reported as a successful placement, explored their educational experiences, some of which related to the support they received. Individually tailored accommodations, specialist interventions and lunchtime clubs to help with unstructured time and friendships were appraised positively. Again, access to a quiet space was viewed as important to manage sensory overload—when this was not available some pupils self-harmed. The background in which pupils received SEND-related support was also important, including a positive ethos, supportive staff, and effective information transfer from teacher to teacher via pupil passports so new teachers understood pupils' needs. New teachers and those who did not understand autism meant that interventions were not always consistent, and sometimes adults underestimated pupils' anxiety as they were adept at masking. One pupil reported getting too much support from her TA when she wanted to “fit in,” whilst another remarked that some teachers had unfairly reduced their expectations of her since her autism diagnosis.

Beyond the UK we found four relevant studies. One recent qualitative study of 20 CYP with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) aged 12–14 years in the Czech Republic explored school experiences, finding that functioning (e.g., doing well academically and positive interactions with others) and inclusion were enhanced by close peer relationships, teacher openness and warmth, pupils' ability to manage their own behavior at school, and practical interventions used by teachers and parents that focused on the young person's strengths (Krtkova et al., 2023). As with previous studies, the small sample size, and specificity of age group and diagnosis limit generalizability of the findings. A larger study of 2117 CYP with SEND from a Swiss canton (an administrative subdivision of a country, similar to a state), used sequence analysis to examine their “transfer trajectories” (i.e., type, number and timing of transfers to different educational placements) over an 11-year period of compulsory education (Snozzi et al., 2025). Results indicated that CYP with SEND experienced frequent transfers but there was high variability dependent on SEND type and complexity. However, these findings may not apply beyond the very specific geographical setting, and the researchers did not consult young people about how transfers to new settings affected them. A study from the USA (Danker et al., 2019) used photo-voice methods with 16 autistic high school students to conceptualize and identify barriers and internal assets to wellbeing in education. The school environment was deemed important to help generate calmness and alleviate anxiety, and pupils said they needed somewhere at school where they could seek refuge. Barriers in the school environment were noisiness and echoes, social problems, and boredom. Access to technology (e.g., computers) enhanced pupils' wellbeing by helping them socially, and academically as it was quicker to type than write by hand. Another study of secondary school pupils described as “high functioning” with autism in France and Quebec explored barriers and enablers of a positive educational experience (Aubineau and Blicharska, 2020). They identified sensory issues and social requirements as barriers to learning and which created excessive fatigue. Enablers were accommodations made by staff to help manage sensory overload and during exams, such as access to a quiet space, use of ear plugs and noise canceling headphones. Being allowed to use a computer and being given extra time in exams was also important. Whilst many said the extra support was helpful, they also needed time without any support to allow decompression.

We are not aware of any studies from England directly examining CYP's health, education and social outcomes following their overall experience of SEND provision over time. This study is part of the wider Health Outcomes for Young People Throughout Education (HOPE) Study, which seeks to examine health and education outcomes of CYP with SEND who have differing levels of SEND-related support. This HOPE sub-study used qualitative methods to explore the experiences and outcomes of CYP receiving support for SEND in England. We have followed the COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., 2007) which is known to improve reporting standards (see Supplementary file 1; de Jong et al., 2021).

Our research goes beyond the extent to which CYP are included in EHCP development and is novel in considering CYP's overall experiences of SEND identification, assessment and provision, over time, including their future hopes and concerns. Our research also fills an important evidence gap about the outcomes CYP experience following delivery of SEND provision, including health, education and social outcomes, what helps or hinders access to SEND provision, and how successfully this is managed during age and stage-related transitions over childhood and throughout education. Our research is timely given the recent change of government, with new SEND reform proposals currently on hold which our research could contribute to shaping. Given the general lack of research directly consulting CYP about their experiences of and outcomes following SEND provision, we believe our findings will be useful beyond UK settings. Our study is also novel in that Public Patient and Involvement (PPI) groups of CYP, parents/carers and professionals played a strong role in shaping all stages of the research, making it highly relevant to service users.

We sought to answer the following research questions with the aim of drawing out barriers and enablers of good SEND provision that were important for health, education and other CYP centered outcomes:

1. What enablers and barriers do CYP experience in the course of securing and receiving SEND provision?

2. What health and other outcomes do CYP report from SEND provision?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Information governance and ethical considerations

Ethics were granted for this study by the Cambridge University Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE.2021.058).

2.2 One-to-one interviews using timelines

We chose to conduct semi-structured one-to-one interviews with CYP, ensuring plenty of open-question formats were used, to allow in-depth exploration of their experiences and outcomes. Semi-structured interviews sit in the middle of the continuum from least structured (unstructured) to completely structured, offering flexibility that allows participants to talk about their own experiences but in a way that is anchored to the research questions set by the research team (Brinkmann, 2014). We also chose to use a timeline in conjunction with our interview schedule questions. Timelines are a data collection tool that invites participants to visually depict key events that have happened in their lives (Bremner, 2020). Timelines can be a useful aide-mémoire for participants to recall their whole experience, and to reflect on changes over time, as well as to help participants navigate the interview, promote rapport and reduce any perceived hierarchies between researchers and participants (Hurtubise and Joslin, 2023). In our study, timelines were co-constructed by researcher and participant pairs. Participants were offered the option to draw and annotate the timelines themselves or instruct the researcher to do so on their behalf (on paper or on a screen depending on whether they had an in-person or online interview), and to choose the colors representing key time points (past, present and future).

2.3 Development and piloting of interview schedule

The interview schedule was informed by key findings from our prior online survey in 2022 about CYP's experiences of and outcomes following SEND provision in England (Gains et al., 2025). We then consulted the HOPE Study's Young People's Advisory Group who reviewed the schedule to ensure that all the questions were accessible and met the aims of the study (see Supplementary file 2).

In February 2023, three of the data collection team met with 16 CYP from a SEND youth council in one English borough who completed pilots of the online and paper-based timelines and interview schedule. The aim of this pilot was to check whether it was feasible to use, acceptable to CYP as a method, and allowed them to tell their full story. The schedule was piloted a further three times (two online, one in-person) with CYP with SEND who were a similar age to the planned sample, after data collectors had received interview training. The data collection team conducted several role-play style practices, including the use of online software to construct timelines, with each other in the lead up to data collection.

Based on the positive feedback from the pilots, we did not make any major changes to the overall protocol, interview schedule or interview technique. We did clarify as a team the specific role the second data collector would play during in-person interviews, and that they would remain outside of the room where the interview took place. We also decided not to include the possibility of participants selecting emojis to illustrate their contentment with different aspects of their SEND provision because of the risk of misinterpretation (some pilot participants found the intended emotions difficult to decipher), and because there was no equivalent available for the in-person interviews.

The final schedule consisted of a series of open questions starting with any support the CYP was currently receiving (as well as any gaps in support) and the impact they thought it had on their health and other outcomes (such as education). The schedule then included the same questions about the CYP's past (starting from primary school), concluding with questions about future plans and aspirations for the following 5 years.

2.4 Training of data collectors

The data collection team included five researchers (two males, three females, JM, IW, PH, CT and SB. All study authors). One was a post-doctoral researcher, two were research assistants (one who had substantial prior experience working with CYP with SEND), and two second year psychology undergraduate placement students all who either worked directly on the HOPE Study, or who were part of the wider research team and expressed an interest in the topic area and in gaining data collection experience. These researchers were supervised by a senior research team: one had prior experience using timelines to collect qualitative data and the other was a mixed methods researcher with relevant experience of conducting one-to-one interviews with CYP.

The two senior researchers ran a half-day in-person interview training workshop 3 weeks before data collection. The workshop included a presentation on how to conduct one-to-one timeline interviews and ask open questions, role-plays, safeguarding, and feedback from senior team members to the data collection team on the quality of their pilot interviews based on auto-transcribed scripts, with attention paid to what went well and what could be improved. One data collection team member could not attend in-person training so had one-to-one guidance from one of the senior team to talk through the training materials, took part in additional online roleplays with other team members, and received written feedback on pilot transcripts.

2.5 Participant recruitment and sampling

We invited CYP with SEND aged 11–25 years, who had completed our previous online survey (Gains et al., 2025). We recruited survey participants by disseminating the survey's URL via our professional networks, to multiple organizations who worked with CYP with SEND (e.g., CYP forums within LAs and national organizations), and via our project's social media account. We received responses from n = 77 CYP, most of whom had an EHCP (currently or within the last 2 years) or a “SEN statement” of whom n = 36 had given consented to be contacted about taking part in future research.

Though we did not specify any explicit exclusion criteria, participants were required to provide informed consent (written or verbal) before participation in both the survey and the subsequent interviews, which would have excluded some CYP. In a separate parallel study (under peer-review) we interviewed parents/carers of CYP with SEND, which represented a greater range of need types than the present study, including those with learning disabilities that would have prevented their participation in one-to-one interviews.

Our target sample size was 20–25, which we thought would provide a sufficient range of responses to answer our research questions and reach data and thematic saturation (i.e., new data would involve a high degree of repeats of previous data, and no new themes would arise in the data; Saunders et al., 2018).

Our recruitment procedure for the present study involved an initial email to gauge interest in taking part in an interview. We then sent the participant information sheet, consent form, and a pre-interview questionnaire to all participants who expressed an interest in participating. The pre-interview questionnaire sought CYP's most recent level of SEND-related support, and their interview preferences in terms of whether it was online or in-person (at the university office or the participant's home), the best days and times for them, and whether they wanted their parent/carer to be present. We allowed a parent/carer in the room, because we learned through prior discussion with participants that some would not have felt able to take part without their parent/carer there. A maximum of four reminder emails were sent to all CYP who consented to be contacted about taking part in an interview, with up to a week between reminders.

2.6 Consent procedure

Prior to the interview, a parent/carer signed the consent form for participants under the age of 16, who were also asked to assent to their participation. Participants aged 16 and over signed their own consent form. Each participant was offered the opportunity to have a pre-interview discussion over Zoom or by phone call with the research team member who would be completing the interview with them, so they could ask any questions and gain familiarity with the process of joining a Zoom call. Immediately prior to the interview, participants were again told about the study, and their right to withdraw without giving a reason.

2.7 Data collection and setting

We conducted the interviews between May and July 2023. All online interviews were conducted and recorded on Zoom; in-person interviews were audio-recorded on an iPad. In-person timelines were drawn on paper with different colored pens, chosen by participants when depicting different times of their life. Timelines for online interviews were drawn using the Scribble Together Whiteboard app, which involved a shared screen so participants could see their timeline as it was being constructed and choose colors to draw different parts of the timeline.

In-person interviews involved two research team members attending: one to conduct the interview and the other to protect the interview space (in the case of home interviews) from other distractions of busy family homes and to ensure researcher safety. The non-interviewing research member took field notes about the setting, noise and other people who could have interfered with the interview. The interviewer later contributed to these notes to state what they thought went well and what could have been better, as a method of reflexive practice to improve interview quality. Field notes were not used in the analyses. Online interviews involved one team member, and field notes only included individual interviewer reflections post-interview.

All timelines were scanned and emailed to participants after the interviews, along with a participant debrief form, which contained information about the safe storage of their data, their right to remove themselves from the study, and signposting to sources of help and support. We did not return transcripts to participants or ask for their feedback about the findings. They were offered reimbursement for their time with a bank transfer or shopping voucher to the value of £40.

2.8 Transcription and anonymization

All interviews were initially auto-transcribed using Otter.ai software (Otter.ai, 2023). The data collection team then listened to the recordings and corrected the initial transcripts so they were verbatim and consistently formatted to designate speakers and where audio was inaudible. The same team members then created anonymized versions of the transcripts for analysis. We did not analyze any of the data depicted on the timelines because they were intended only as a tool to help structure the interview and elicit participants' experiences over time.

2.9 Data analysis

We applied the framework analysis approach outlined by Gale et al. (2013) which identifies commonalities and differences within participants' accounts of their experiences (in this study to consider changes in SEND provision over time), and between participants' accounts (to consider the range of experiences being described), which generated overall key themes for discussion. The method is flexible, combining inductive and deductive approaches to derive the analytical framework. We considered it a more pragmatic, structured approach for multiple team members to apply compared to approaches that place greater emphasis on researcher reflexivity and organic development of themes in the data (Braun and Clarke, 2021).

Using Gale et al.'s stages of analysis, after transcription (stage 1) and familiarization with the transcripts (stage 2), one senior and two junior research team members developed an initial framework for analysis based on the key questions of the interview schedule and used it to code the first three transcripts (stages 3 and 4) in Excel. The framework was refined using another seven transcripts over four meetings until the team were confident the framework encompassed all the data in the transcripts (stages 4 and 5 continued). The final framework was used to code all 15 transcripts in Nvivo version 14 (stage 5). When all transcripts had been coded, we generated a matrix to allow summaries of our final themes and sub-themes, and to identify commonalties, differences and deviant cases (stage 6).

To complement the thematic analysis we used narrative portraiture methods for selected participants, using the practical guidelines provided by Rodríguez-Dorans and Jacobs (2020) which are ideally suited to the timeline data we collected. This method allows presentation of a participant's whole narrative account including the context around it, to honor their individual story. Narrative portraiture can provide a useful balance to findings from thematic analysis which tends to focus on commonalities between participants' accounts Rodríguez-Dorans and Jacobs, (2020). We drew out summary stories (hereafter called “case examples”) from three participants in our sample who had contrasting experiences and outcomes, using the following steps: (1) marking key “characters” within a transcript (explicitly named or implied); (2) identifying time scales within our existing past, present, future format; (3) identifying sentences that orient the story in relation to macro space (e.g., an LA), micro space (e.g., a classroom) and virtual space (online, emotional/mind-set) to help map the story and processes; (4) identifying “key events and turning points” and the interaction of different factors, and how these relate to our two research questions. Here we focused on how barriers and enablers the participants described had led to particular outcomes, to ensure relevance to our research questions.

We only analyzed text from the transcripts (i.e., what was spoken aloud and transcribed), and did not analyze the timelines themselves. As the interview questions were ordered in time and over time it meant the transcripts were amenable to developing the case examples.

2.10 Data exclusions

When there were additional people present at an interview (e.g., a parent) who interjected in conversations we developed criteria about what could be legitimately coded for that segment of speech. In the absence of official guidance on this topic, we decided to code only CYP's speech, and only when the CYP responded first after an interviewer question (which may have been followed by a parent/carer comment), or if the CYP's response came after a parent/carer response, but they used their own words beyond a yes or no response. Where it was unclear, we listened to the audio and discussed with the interviewer to decide whether to code an excerpt as a true CYP response or whether to exclude it. We did not include parent/carer words in the analysis and generation of themes.

3 Results

3.1 Response rate and final sample size

Of 36 CYP who agreed to be contacted about future research in our prior online survey, 33 expressed interest in taking part in the current study, of which we were able to recruit 16 (44% response rate). Whilst we did not require participants to give a reason for declining the invitation, our records indicate that in most cases this was due either to not replying to any of the four invitation emails, or because it was not possible to find an interview date and time that suited the CYP and interview team. All participants had an EHCP or SEN statement, which was not an eligibility criterion for this study, but related to the pre-existing list of CYP we used for recruitment. At the point of analysis, we excluded one interview which we assessed as unduly influenced by the presence and agenda of the parent and did not include much or any of the CYP's own opinions. In another case, a parent was present and at times joined in with the conversation, but we judged that most of the interview represented the CYP's own voice. We included 15 interviews in the final analysis.

3.2 Participant characteristics

Around two-thirds of participants had diagnosed or suspected ASD, often in combination with at least one other need (commonly ADHD, dyspraxia, hypermobility and/or auditory processing disorder). Two participants had visual impairments, two reported they had moderate learning disabilities, and one had epilepsy. Several reported social emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs. The age range of participants was 13–25 (mean = 18.56 years, Standard Deviation/SD = 4.84). We have grouped age in years as follows to preserve participant anonymity: 13–15, 16–18, 19–25. All participants had completed primary education and at least 1 year of secondary school, with most participants completing compulsory education by the time of the interview. Participants' current or most recent education settings included: non-elective home-schooling, online schooling, mainstream secondary school, college and university (the latter two settings are hereafter termed higher education/HE student).

The sample included CYP from 5/9 of England's regions (Office for National Statistics, 2021). Interviews ranged from 55 to 80 min in length (mean = 67 min, SD=6.80); three were in-person, and 12 were held online.

3.3 Key themes arising from the data

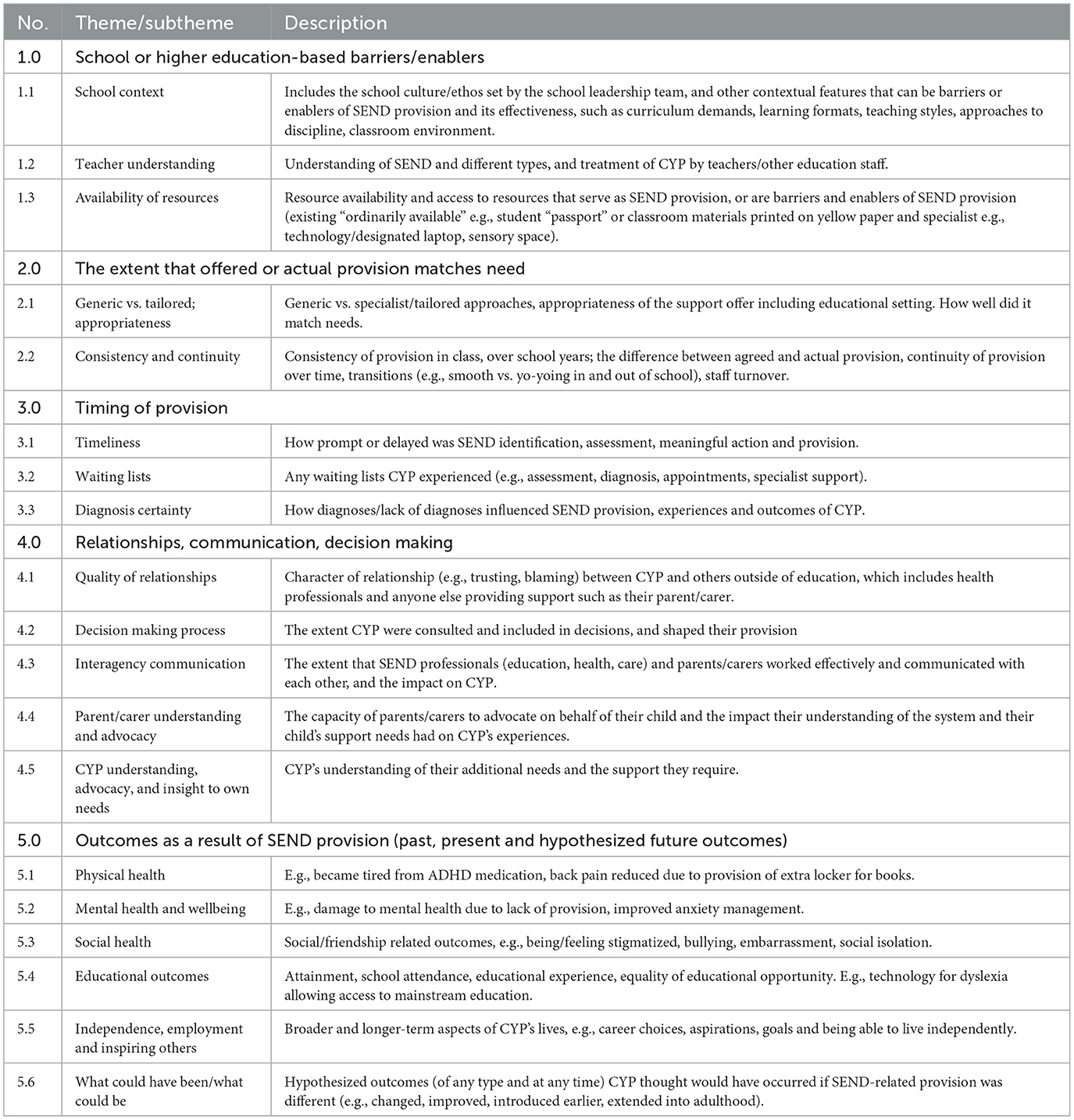

We identified five themes and subthemes (see Table 1). Themes 1–4 capture enablers and barriers to securing and receiving SEND provision (answering research question 1): (1) Education setting-based factors (school context, teacher understanding, availability of resources); (2) The extent that offered or actual provision matches need (generic vs. tailored approaches, appropriateness, consistency, and continuity); (3) Timing of provision (timeliness, waiting lists, diagnostic certainty); (4) Relationships, communication, decision making (quality of relationships, decision-making process, interagency communication, parent and CYP advocacy and understanding of needs). Theme 5 includes outcomes following SEND provision (physical, mental health and wellbeing, social, educational, independence, employment and inspiring others, and what could have been/what could be; answering research question 2).

3.3.1 School or higher-education (HE)-based factors

All CYP discussed their experience of their educational settings in terms of how they helped or hindered the identification and provision for their needs. Within this theme we identified three sub-themes. Firstly, the educational context (1.1), which included the school culture and ethos around SEND set by the school leadership team, which influenced the context for SEND provision, and how it was delivered and received, which in turn affected CYP's educational experiences. Reports were mixed. In less favorable contexts, CYP mentioned a reluctance by schools to offer provision that was not directed by an EHCP or being treated differently by staff after being identified with SEND.

“They don't really like putting stuff in place when they don't have to, even if it does benefit the kid.” (#103, age group 13-15, online school)

“I think that once you have your name as a SENCO kid people judge you differently. Or especially that's the culture within my school. But yeah, I think if it doesn't come from it, it doesn't even come from the pupils, it comes from the staff.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Others talked about perfunctory awareness raising about SEND. For instance in an assembly “supposed to be about like autism and ADHD,” where there was “two and a half minutes on that,” and “twenty-two and a half minutes was discussing the new library.” (#123). By contrast some CYP talked about inclusive, positive attitudes of staff positively affecting their educational experience and SEND-related support.

“The teachers really understood me like, not at my first three schools, but when I was at the special school, they really liked, it's the first time I felt understood.” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

“The support I'm getting at college, and just the general attitudes towards disability, there are a lot more positive than it was a high school.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

Sub-theme 1.1 also included characteristics of the standard learning environment and the extent it inhibited or enabled SEND provision and influenced CYP's subsequent outcomes, such as national curriculum demands, learning formats, teaching styles, approaches to discipline, and classroom environment features, such as the numbers of CYP, understanding of peers about SEND, and noise levels.

Generally, exam-heavy assessments, busy timetables and particular teaching styles undermined the effectiveness of SEND provision, exacerbating SEND-related problems, and reducing CYP's learning and attainment potential.

“My fatigue was already massively increasing during GCSEs… I'd come home every day, and I'd have to sleep for at least an hour, because I found the school environment so draining.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

“I did struggle with the move to online, definitely, I really find it much harder to learn online because I just I don't know why I can't pay attention for long enough…it feels a bit more scary.” (#105, age group 19-25, HE student)

“…in substitute lessons, they always want you to, like, track the teacher or whatever, like, look at the teacher all the time. But I just don't look at people when I talk to them. I don't know. It's just like a thing that I've just, like I see their face once and I just kind of know it. It just feels weird.” (#123, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

The majority of participants with autism also discussed the significant ordeals they faced due to sensory overload in the classroom. Some CYP were removed from classes by teachers because they were unable to cope with classroom noise and actions of other students.

“They took me out the lesson because there was just loads of messing around… and I didn't cope very well.” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

“I found it really hard to cope in lessons, I used to have these meltdowns …because it was loud. And it was sad because I actually really like, I liked school like I like learning. But I found it really hard to stay in the class.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

With contrasting experiences, some CYP described the benefits of additional time being scheduled between lessons, permission to leave their classroom, and support for exams. These enablers more often occurred in further education, which tended to involve smaller class sizes, increased flexibility, and autonomy to learn independently in a way that suited them.

“…with sixth form. It's more independent…much less rigid.” (#126, age group 13-15, online school)

“I was doing like a BTech course…the environment was much nicer, like the campus was much bigger, but it meant that there were like, it was less crowded, like less crowded, I had a lot more like freedom so that really helped with me being able to manage my own workload.” (#133, age group 19-25, HE student)

More neutral or supportive peers meant participants were not afraid to “speak up” about adjustments they needed in class, whereas others said their peers rejected them “for being like weird or neurodivergent, or just just like not neurotypical,” (#128, age group 16–18, HE student), which was said to act as a barrier to asking for help.

“…no one's made fun of the fact I need blue paper you know, like, I've been fine to say, oh, yeah, that blue papers for me as you're handing out the worksheets.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Teacher understanding of SEND (1.2) strongly influenced the extent and consistency with which provision was implemented, and its effectiveness in meeting CYP's needs. Many teachers lacked SEND training, particularly about neurodiversity, or had negative attitudes about SEND which changed how CYP were treated.

“Some of the teachers are just not educated in how to fix some problems. And I think, even though they have teacher training every week…they don't teach them anything about it.” (#123, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

“It does make you think like are the university tutors actually educated enough when it comes to the sorts of things.” (#127 age group 19-25, HE student)

“My current relationship with SENCO is quite, we avoid each other, cos they're not too great with seeing me as a person, and there are times where they patronise me and that really gets to me.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Several participants talked about the importance of “good teachers,” and positive working relationships with staff who were a point of contact who listened and advocated for them. Teachers with a good understanding of how to meet SEND-related needs helped CYP access classroom learning and remain in lessons.

“Maths was the easiest to stay in because I liked it and my teacher was quite good at, handling me.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

“She [the SENCo] was really flexible to anything I felt that helped me.” (#131 age group 19-25, HE student)

“Sometimes I'd just have these like panic attacks and I'd just go and sit in the head teacher's office because she was absolutely fantastic. She was really caring and understanding.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

Availability of and access to resources (1.3) served as SEND provision for some CYP. This included what should be ordinarily available in mainstream settings, as well as more specialist provision not available as standard. Non-specialist resources included low cost adaptations to computer screens to change the color of the overlay, noise canceling headphones, and strategies to help management of sensory overload. These transformed some CYP's access to learning and was often cited as helping improve exam performance, though it was not consistently implemented.

“They tried me on a computer for one time I did fantastic. Then they never did it again. I couldn't write. It was painful to do.” (#103, age group 13-15, online school)

“I have headphones in, because, they're kind of, it's weird because I can get sensory overload from too much going on but also complete silence.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

“This was around exams about being really overstimulated within the exam hall because we did SATs in the big canteen with all the tables and chairs. And they put me in a different room for, they offered me to put me in a different room.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

“…at the moment, obviously, we've been doing lots of work on revision and exam technique and things like that. Which is pretty good, to be fair I do think probably this year, it might be the best I've done in my exams.” (#118, age group 19–25, HE student)

Other aspects of the physical space and relevant adaptations within educational settings were important aspects of provision for many CYP. Experiences were mixed.

“I was still having fits, so I was struggling to walk sometimes … we used to have a lot of stairs, so I'd be afraid of like falling down the stairs and stuff.” (#127, age group 19-25, HE student)

With reference to having an additional locker designated for them at school: “…it's to ease the load on my back because I have hypermobility…So I don't usually carry my books to school. They're usually in school, which also helps, because that basically means it's impossible for me to forget my book.” (#110, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Many CYP talked positively about the availability of more specialist and/or costly provision within settings, such as specialist services/clinics, sensory spaces, or entire buildings. Again, CYP emphasized that quiet designated spaces helped with self-regulation when they were experiencing sensory overload. One CYP described that in a previous setting without a quiet place to retreat to had meant they inflicted accidental injuries on themselves during meltdowns.

“So that dark place [the current sensory room]…compared to the corridors [of the previous setting without the sensory room] probably would have helped. Also, a lack of soft things to smash on. Because, the only way for seven year old [CYP Name] to get rid of his stress at that point in time was to exert physical force on something. And a hard table is very painful…once you finish having the sensory overload you suddenly realise, oh, no, my head is hurting quite a bit.” (#110 age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Others talked about the benefits of being able to access specialist staff onsite.

“There was a mental health clinic on campus. Oh, I guess there was like a nursing clinic on campus, but they had like specially trained mental health practitioners there.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

“…the sensory space is just a large, it's a large area where were made up of school rooms, one of them is an office for the SENCo and all the support workers. Another one of them is a very, very quite apparently noise insulated room, very small, but very quiet as well. For people who are having serious sensory overload. Another one is a fairly quiet room. Quiet talking.” (#110, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Another CYP emphasized how crucial their transport was for being able to attend HE settings.

“…when I lived off campus, they paid for taxis to the [HE institution] so I didn't have to take the bus because I find the bus quite hard.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

There was often high demand for certain resources, particularly specialist staff and within alternative provision, which diminished the effectiveness of SEND provision in helping CYP access learning.

“…one TA to like 10 people, which was quite a lot you know when you think about it…you've got to like, wait for them to come around again, like, and you could be waiting for like 10, 15 minutes do you know what I mean because they've got to go see everyone.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

“I think it was much harder to receive support in alternative provision, because there's less funding and you're sort of off the map, so you have to fight really hard for everything. That's an experience I've definitely had.” (#125, age group 13-15 mainstream secondary school).

3.3.2 The extent that offered or actual provision matches need

The extent to which SEND provision was generic vs. specialist/tailored and appropriate to meet CYP's needs was a strong sub-theme (2.1). Often generic provision was evaluated as ineffective for CYP related to mental health interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which many autistic participants could not engage with as they were not sufficiently adapted, as well as strategies developed for dyslexia that were offered to a CYP with dyspraxia.

“…they kind of suggested, like, lots of things that I might want but I haven't really like, pursued any of them because there wasn't anything I thought was like, super relevant for me.… it was much more relevant to dyslexia…just really like generic suggestions. And I was like, well that's not that relevant to my life.” (#105, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

“I've had CBT and all of that for it multiple times, but like most people, I've said it yeah, that doesn't work really for autistic people, it doesn't work for me…they were trying to treat the anxiety, but they weren't focusing on the autism…I didn't want to engage with like the support they were giving me…it wasn't the right support.” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

Another way in which SEND provision offers to CYP were not sufficiently tailored to meet needs concerned their educational setting. As illustrated in 1.1 several CYP said the academic and social demands and environment of mainstream settings led to sensory overload, that was not possible to overcome in some cases. This meant some CYP were stuck between mainstream and specialist provision, as the latter was not academically challenging enough. In some cases there were disputes with schools and LAs about which settings could meet a CYP's needs, which led to periods when the CYP was out of formal education.

“There are really no other places that would suit me. I mean it's not perfect, online school, but it's definitely the best option I have. I thought about them for a while but there is no perfect place for me, we've looked at almost every school and there doesn't really seem to be an option…I don't think there is any perfect provision at the moment for me.” (#126, age group 13-15, online school)

“I stopped going to school is the most simple way of saying it…I would, every night I everything would just break down after coming home, everything would…I'd, I just wasn't me.” (#113, age group 13-15, non-elective home schooling)

In contrast to CYP receiving generic or unsuitable support to meet needs, those receiving tailored provision often described it positively, and that it was able to meet their needs, irrespective of a diagnosis or an EHCP.

“…whatever support I was getting, or whatever support I would request, I could make sure that it was tailored to my exact needs.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

“My primary school was never like, yeah, it was fabulous, honestly…It was very well organized. Like every teacher knew [about the CYP's required adjustments for dyslexia]…And yeah, I wonder what training they had on it honestly, cos they were just, impeccable.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Even with tailored support, CYP talked about the importance of further iterations to improve it, for example to optimize the intensity of support provided.

“I actually don't want too much support. I'm, I actually, my school would have given me one-to-one support in lessons if I hadn't specifically said, no, I don't want one to one support.” (#110, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Consistency and continuity of SEND provision (2.2) was a common determinant of how effective it was and often linked back to the class teacher or school senior leadership team, and to a lesser extent, LA staff. Though there were positive examples of teachers who “never forgot anything,” negative examples included interventions being implemented for a short time before being removed or scaled back without discussion. Others mentioned lack of continuity between school years, or when transitioning from primary to secondary school as adversely affecting the quality of their provision and educational experiences.

“…some teachers look at it [the CYP's student passport, listing their needs and interventions] and do it really well, like with my [student] passport from last year, some teachers just don't look and don't bother.” (#125, age group 13-15 mainstream secondary school)

“It depends on the, what teachers I have and what current mood they're in, it's, it's pretty random. Like I'll have a lesson that's going amazing at the start, right? And, like the teacher like misun…, or I misunderstand or something, or they catch me just not looking at them. And then they shout at me.” (#123, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

“…the person who's supposed to do it in the [LA name], she's just buggered off… disappeared, haven't heard back from them, it's been about a month now.” (#103, age group 13-15, online school)

3.3.3 Timing of provision

The timeliness of SEND identification, assessment and provision (3.1)—i.e., how promptly or delayed the process was—was a prominent theme, discussed by nearly all as important for their educational experience and outcomes, and their mental health trajectories. Most said they would have preferred their support to have been put in place “much earlier,” with some saying it would have eased their transitions through school and into independent adulthood. Many CYP said that delayed identification worsened their mental health and other problems became entrenched. Outcomes related to timeliness of provision are explored further in theme 5.

“They could have like maybe like, you know, maybe got us to do like stuff like that sooner, you know like the bus pass like because it's okay doing at 16 but like, if you're going leave school at 16 you know what I mean then you need to be able to do it beforehand surely like you know what I mean, you know when you get to 13 14.” (#127, age group 19-25, HE student)

“…it [autism] was never picked up on as like a disability or condition, so I was just completely unsupported in that way and then it just meant that I ended up like, I'd have like, a lot of friendship problems, and, like, yeah, it was, it was quite difficult, especially when I moved to year 6.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

Delayed identification sometimes occurred due to poor teacher understanding about different SEND types, for example that autism can present differently in girls compared to boys.

“…academically I was miles behind, but, some of the, but like yeah, I felt that teachers didn't understand autism. And I feel because I was a girl like compared to some girls I would say I'm more, but because I'd say like, yeah, they never really like, they just thought my mum was making a fuss really.” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

Negative experiences were not universal though. Some CYP said appropriate support was implemented when they felt it was needed, and it was very beneficial.

“Definitely yeah, like I don't think I would have been able to do as well as I did on my GCSEs or even that well at all if I didn't have the support.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

Linked to concerns around prompt identification and provision, several CYP reported issues with waiting lists (3.2), mostly linked to extensive delays when seeking assessments from health services and LAs, during which time they received limited or no SEND-related support.

“I spent a lot of time on waiting lists for things, but nothing ever came of it. I, like because eventually when I spoke to my parents in year 11, we went to the GP to go get an official diagnosis, but then I sat on the waiting list until I was in Year 13.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

“…because there's such a long waiting list for like, EHCPs and things, I didn't get that until end of year 6, but, but that's quite frankly, because the NHS waiting list is way too long.” (#123, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

SEND diagnosis certainty (3.3) was also described as an important influence over the timing of SEND provision. For example, schools could be reluctant to offer any support without an official diagnosis.

“…I was just waiting again. Yeah, definitely. They definitely didn't like, provide any support on the chance that I was autistic you know it was kind of like, business as usual until it was confirmed as one way or the other.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

Many CYP believed that their needs were overlooked by the professionals around them because the effects were not severe or disruptive enough; some said they were not “listened to” leading to late diagnosis and support.

“…I think they sort of noticed, but because I was happily enough doing my own thing, I think it was kind of, you know, with hindsight, having spoken to them since they were like, yeah, we noticed [Laughs]. But I think because it wasn't presenting as a problem.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

Other CYP told us their other complex conditions overshadowed their SEND which in turn acted as a barrier to SEND-related support being offered.

“…when I was a teenager, I was really struggling with an eating disorder, which may also be part of the reason why I wasn't picked up earlier because, you know, maybe people thought of, you know, that explains why she's just got stuff going on. That's why she's a bit forgetful or whatever…” (#105, age group 19-25, HE student)

3.3.4 Relationships, communication, decision making

The quality of relationships (4.1) CYP had with key professionals and their parents/carers were an important influence on their SEND identification, provision and outcomes, interwoven through many discussions. Experiences were mixed, with poor quality interactions leading to disrupted or prematurely stopped interventions, sometimes leaving CYP without any alternative support.

“She [therapist] was- she's was bit manipulative when I was gonna leave [therapy before the sessions had been completed] because she was like me and she's like, Oh, “you'll never see all these [therapy-based] toys again”. I remember that. And also, by saying someone plays wrong, this is very ableist because it suggests there's a correct way to play and, you know, if I like lining things up, you know, that's that's perfectly fine.” (#126, age group 13-15, online school)

“…they basically diagnosed me with a life changing disability, then we're like, ‘Okay, bye.' And I thought well, I only reached out to the health, like, obviously, I only reached out to you in the first place because there was a problem so if you're not doing anything to solve the problem, you've just given the problem a name, that's not helped in any way.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

In contrast, others told us about positive relationships with family members and professionals playing an important role in designing appropriate SEND provision and helping to advocate for CYP.

“…I had a lot of discussion with my mum about it at home, like we had a lot of talks about what support would be right for me and kind of what's best going forward.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

“…even like when I came to [HE institution], I wasn't diagnosed with ADHD yet, that only happened through like the like suggestion and encouragement of like, the mental health [professional] I was seeing.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

Linked to relationship quality was how reciprocal the relationships were (4.2), including CYP being listened to about their needs, having their support plans explained, and being able to influence their support.

“They [The Disabled Student Allowance Service] listened to what I said, they offered me support, they didn't feel like they were making me prove things. Like I felt that they took my word for it not making that I didn't need to prove, like what I was saying they believed me.” (#133, age group 19-25, HE student)

“…the old head of SEN, she's still part of it, but like, she was the head, we like have a pretty good like, knowing of each other. And then she'll, she'll always like keep me updated on what's going to happen next. So that's good.” (#123, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Most CYP discussed the impact of inter-agency communication (between education, health, and care sectors) on their experiences of SEND provision (4.3). Unsurprisingly, poor communication, guidance and signposting negatively influenced CYP's educational experiences and quality of provision received.

“So I guess I can speak to them but I guess it's confusing. We don't know if it's meant to come from social care, or education…And then we have some stuff and then we were asking about work. And social care was like, oh, no, that's education. They just seem to pass it around each other.” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

“Yeah, it's just like, not knowing who the people are to talk to you as well. I mean, it's just an issue being at a massive [HE institution], which is really poorly, like, linked up.” (#105, age group 19-25, HE student)

In contrast, one CYP described a positive experience when transitioning from secondary school to higher education.

“…it was in the summer holidays before I started…I spoke on the phone for like, two hours with someone and then they came up with all the things that might help um, and then they contacted the [institution] and said, here's, here's the money, do the things.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

The importance of parent/carer understanding and advocacy (4.4) was discussed by almost all participants as playing a key role in securing SEND provision throughout their education. Some CYP discussed how it was down to their parents/carers to “fight” for diagnoses and support.

“…Year 8 I got, I had a very external meltdown. And then they were like, let's get you a timeout pass, which my parents had to push for very hard on my behalf.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

“That was my, my mum pushing for it. Just to make sure that support was in place when I started Sixth Form, because it was always change that was the hardest. So she just wanted to make sure that happened.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

CYP's understanding, advocacy, and insight into their own needs (4.5) was also a prominent sub-theme influencing SEND provision—such as understanding the services that were available to them, or lack of awareness about who to ask or where to enquire about further support. Some CYP talked using terms such as “fight” when negotiating provision with SEND professionals and needing to be proactive in communicating about their needs.

“I didn't really know what CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) was or that charities provided support. I think so I wasn't really sure and I didn't really know what to ask for, like what my rights were…I wish and I did tell them at the time, but they said that they had to follow the like NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines or that yes, or some like health guidelines, which is difficult because I felt like reasonable adjustments could have been made for me.” (#133, age group 19-25, HE student)

“I set clear boundaries at the start of the year with my teachers saying, this is what I'm able to do, this is what I struggle with, and this is how you can help me so I think that's really cleared it up with how my teachers, were able to support me.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

3.3.5 Outcomes from SEND provision

Several different outcomes were discussed by CYP as resulting from SEND provision, including physical, mental health and wellbeing, social, and long-term employment and independence. Given that we asked CYP to look into the future, and back into their past, many participants speculated on what their outcomes could have been or could still be.

Physical health outcomes from SEND provision (5.1) were discussed by around half of CYP, who usually described meaningful benefits.

“I have like one of those like spinneys desk chairs because like, I stim quite a lot with it and it like kind of helps calm me down but also for like my dyspraxia I find sitting in like a normal chair for an extended period of time in like a high pressure setting, quite uncomfortable.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

As described earlier, one participant said the sensory space reduced their risk of accidental physical harm when they experienced sensory overload because it promoted de-escalation of meltdowns and contained fewer hard surfaces on which CYP could become injured.

“The most I got was a lump in my head, which went away after a couple of days. So think I'm pretty lucky that I didn't hurt myself when I was exerting that force.” (#110, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

In contrast, when agreed provision for physical health problems was not put in place, it could adversely impact health and education outcomes.

“…more migraines. I have had like a difficulty seeing when things haven't been provided properly.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

Mental health (5.2), both positive and negative, was one of the most commonly discussed outcomes from SEND-related support, often related to how much the CYP was listened to, the appropriateness of the support they received, the age and stage at which support was provided (and the impact of delayed provision), the quality of transitions, and the complexity of their SEND.

“I did speak to them [the school] about it [getting extra time in exams], and they sort of said that they felt that I'd be alright without it. But from my point of view, I wasn't really doing all right and I thought sort of wasn't really going out or I wasn't really like yeah, looking after myself very much, so it made it quite difficult then to do schoolwork and things…so it definitely impacted my mental health.” (#133, age group 19-25, HE student).

“…I was struggling so much with that [friendships, relationships and understanding other people], and I felt like no one could help me and I didn't know why I was struggling, it just made things worse, you know it's like a self like perpetuating cycle where it's like, the more I struggled socially, the more anxious I got, and then the more like, kind of yeah, like mental health problems…it just had a massive impact, on, yeah my performance, my attendance, and just like yeah, my whole health and wellbeing for all those years.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

Despite some CYP experiencing negative outcomes from delayed provision, once support was implemented it tended to make a positive difference to mental health and academic achievement.

“It [broad set of school-organised interventions over time including a mentor] definitely made a difference to my mental health, um. Yeah, I think I think the help helps a lot. Because I think I would have really struggled if I hadn't had it, which obviously would have had an impact.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

“I've got depression and anxiety, and I think, I, ever since I got the support put in place, I found school, like the academic side of school easier to cope with.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

Social health outcomes (5.3) were discussed by several participants. A minority enjoyed spending time with others who had similar needs within sensory spaces, but most reported negative impacts, and in one case, social isolation due to a planned move to online school:

“…it's helped me like stop getting told off by my teachers. But I'm not seeing my friends.” (#103, age group 13-15, online school)

“…being sat by myself with all my mates having fun at the back, is, is a bit deflating but apart from that, it's fine.” (#125, age group 13-15, mainstream school)

Along with mental health, educational outcomes (5.4) were one of the most talked about, including the impact of support for SEND on attainment, school attendance, educational experience, and equality of educational opportunity. Several participants talked positively about the effect of provision on their attainment, which for some was almost immediately felt.

“…without the support in the actual exams, all of the stuff that built up at home and in school of like the revision stress and the fatigue and all sorts of that, if I had no support, I was just put into that exam room with everyone else, I just would have absolutely flopped I think, like everything would have, I just would have been really really overwhelmed.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student).

“In my grades went like so for because you do the SATs, you do one in September at [school], they weren't, they was a bit low, a bit meh, but after I got it [acetates and worksheets] on yellow they went straight up.” (#125, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary)

“I was able to come in, I didn't come in to school for ages before that.” (#126, age group 13-15, online school)

For CYP who experienced delays in SEND provision (e.g., due to ongoing LA-level processes), whose provision was not implemented as agreed, or for whom reasonable adjustments were not made, the impact was detrimental to their learning and equality of educational opportunity.

“I have to have it [coloured overlay on computer screen] so thick that people can't read what's on there. So when we went back into school with that on because I was doing one lesson a week, the teacher told me to turn it off, because she couldn't see it, but without it I could barely read it.” (#103, age group 13-15, online school)

“…so teachers, so PowerPoints for me are an absolute nightmare and to be honest, no one in my class enjoyed PowerPoints, we had one teacher who is very knowledgeable, but he teaches too high like degree level and he would just speak, I'd always feel stupid in his lessons and he would just speak on and on and even my LSA [learning support assistant] she'd be confused.” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

For some CYP, educational outcomes were improved through understanding teachers being able to provide support tailored to their needs and learning styles. Several participants praised their education settings and teachers who helped to manage SEND-related challenges at school which helped with their educational experiences and outcomes.

“…thanks to several brilliant teachers, I was just able to gain an understanding of the world, and stuff, which, helped to, I guess helped to make myself integrate to the point where the capabilities that I have actually started to show a bit…once it got to a certain point, the school just decided to, remove the training wheels a little bit and I actually survived in school I, I was getting really high on every test.” (#110, age group 13-15, mainstream grammar school)

“I think my school did really well, like considering they even know didn't really know what was going on with me and I think that kind of support at that stage did like, you know, it allowed me to still like, enjoy education and like discover the things that I really enjoyed and now like pursuing that further.” (#105, age group 19-25, HE student)

Most CYP talked about positive independence and employment outcomes resulting from their SEND-related support (5.5).

“…So he helped me with things like that, like learning how to take the bus, and, finding my way around, and things like that.” (#118, age group 19-25, HE student)

“Travel training definitely helped yeah, I mean I've been to you know we've been to London three times this year.” (#127, age group 19-25, HE student)

“I was able to kind of get out and about more, I was able to, like, take control of my own, like health and things, like, I started being able to like book appointments for myself and like, manage, like, all that kind of thing myself but also, yeah, like, getting out and like walking and feeling happier too.” (#133, age group 19-25, HE student)

In contrast, several participants were uncertain about the effectiveness of employment schemes and post-16 funding for CYP with SEND, and how this could impact on their future job prospects. For example, they depended on employers' willingness to engage with relevant schemes to accommodate SEND and fund particular adjustments:

“…my support at [HE institution] was tied to my Disabled Student Allowance [DSA] and my tuition. You know, access to work for example, is tied to maintaining like a job, so, I think that would be the barrier is just like if I don't manage to find like a, a stable job right away, or if like, it's just a very like hard process to get them to work with access to work, because I've had that before where it's like, they have to be dragged kicking and screaming for it because they didn't really understand it.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

What could have been/what could be (5.6) in relation to outcomes of SEND provision was discussed by all CYP, naturally as part of the timeline-based conversation. Many CYP hypothesized that their outcomes would have been worse if no support had been provided centered on academic performance, attendance, organization, and enjoyment.

“I just would have struggled, probably had like lots of, not panic attacks but I would have panicked probably a lot, I guess, yeah.” (#124, age group 19-25, HE graduate)

“My grades just would have gotten worse, I would have found stuff like I already found GCSEs quite mentally and physically draining and overwhelming.” (#128, age group 16-18, HE student)

Several CYP believed there would have been a positive impact of being placed in more suitable educational settings for social relationships and academic outcomes.

“I think if I went to a special school, I would have been able to have friends at my level, communicate and learn at my level because when I went it, it all came apparent to me when I moved schools at 13 and I thought I was, this was a learning difficulty school and it was ridiculous I was in all the middle sets...” (#131, age group 19-25, HE student)

“There's a lot of things that I probably got in the SEN setting, which I wouldn't have got if I went to mainstream like…things like the one-to-one support like you know what I mean.” (#127, age group 19-25, HE student)

CYP also discussed their beliefs around earlier support and identification and how this may have improved their educational attainment and minimized negative mental health outcomes.

“…if I'd have had, the tutors I have in place now back then I think we'd be where I want to be there.” [Gestures towards into the future of the timeline] (#113, age group 13-15, non-elective home schooling)

“…a lot of damage had already been done by my experiences before that, so even though like I desperately needed and benefited from the support that was then given, it wasn't really enough to make it like smooth sailing from there.” (#130, age group 19-25, HE student)

One of the key influences on what could have been better for CYP was an improved understanding from professionals involved in delivering SEND from both education and health services.

“…a wider knowledge of neurodiversity from the staff would have been great to see if I was on the verge of you know, a meltdown or sensory overwhelm. That would have been very helpful for them to know how to spot it and know that what was happening and why it was happening…being more accommodating for when I felt very overwhelmed at the edge of a sensory overload.” (#126, age group 13-15, online school)

“I had to join a group like I did like group therapy for anxiety and I didn't want to do a group I wanted to do one to one because I felt like I felt really like I'd struggle in a group and like, due to being autistic as well, it makes it a lot harder to be like a like talking about things in a group and like managing that interaction.” (#133, age group 19-25, HE student)

Several participants speculated about the positive impacts of consistently implemented support to improve their educational and mental health outcomes.

“I'd actually be able to read what people give me I'd be, I'd be able to participate freely. And in terms of my learning, I'd come home, with energy being able to be spent on, I'd come home with energy, being able to spend on revision and making sure my life is as prepared for the test, rather than making sure school is accessible for me.” (#121, age group 13-15, mainstream secondary school)

3.4 Contrasting participant experiences through the system

We have presented three case examples to illustrate contrasting experiences within the system, and key turning points and “characters” that positively or negatively influenced their subsequent health and educational outcomes over time (see Case example boxes 1–3). Case example 1 was an HE student but had long-term mental health problems, which they attributed to late identification of SEND, and waiting several years for a diagnosis before any support was implemented. In contrast, Case example 2, also an HE student had a generally positive experience through school but felt abandoned by health services. They thought their school could have supported them earlier, but staff did not wait for a diagnosis, and put in place effective individually tailored, needs-based approaches to help the CYP manage their emotions day-to-day and during exams. Their transition to HE had been smooth, and their provision timely and appropriate to support their needs. Case example 3, is a CYP of secondary school age who was being non-electively home-schooled by his mother. He loves learning and maths but struggles with friendships and the school setting. He stopped attending primary school due to school-based trauma. After 2 years he attempted to attend a secondary specialist setting, but the placement broke down within weeks. After 5-years of being out of full-time education the LA has begun providing 6-h of home tuition a week, though he wished it could be more.

Box 1. Case example 1. Female, age group 19–25, autism and ADHD.

Primary school: The “consistency” of being “in the same place” suited her, but it was “hard” “being constantly in trouble” and “upsetting” teachers because she “would not pay attention.” She “wasn't very well understood” and her behavior was not identified as reflecting SEND. She was “completely unsupported,” with “a lot of friendship problems.” Her difficulties intensified when she moved schools in Key Stage 2.