- Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, Morgridge College of Education, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

This study is a cross-case comparison of three cohorts of teams of educators implementing a continuous improvement program in partnership between a university and a district. Using interviews, document analysis, and observation, the researchers looked within and across cohorts to determine how the teams applied the continuous improvement process to their work. Using a complex systems change framework, this study explored the relationship between the program structure and content and the implementation of an improvement process at the schools, including the challenges and benefits of applying the process. By providing the components to manage complex change, this program was able to help schools report benefits of (a) deliberate, deep, and intentional change, (b) within school and across school learning and collaboration, (c) shifting mental models and mindsets, and (d) greater collective responsibility for improvement by mitigating the challenges of (a) the tension between the time available and the complexity of the process, (b) the alignment between the process and district priorities resulting in competing priorities, and (c) the capability to spread the learning school-wide.

Introduction

Schools, by many measures, need to better serve students and their families, and educators regularly seek to improve student outcomes. One way to make the necessary improvements is through continuous improvement practices like improvement science (Bryk et al., 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). Researchers and practicing professionals have recognized the benefits of continuous improvement in schools for decades (e.g., Kaufman and Zahn, 1993; Langley et al., 2009; Morris and Hiebert, 2011). Although continuous improvement is a promising practice to ensure schools better serve students, there is still much to learn about the application and implementation of improvement science in schools (Means and Harris, 2013; Valdez et al., 2020). When any improvement effort is done in partnership with outside organizations, it is important to understand if, why, and how the “frontline” educators, such as school teams, respond to and manage the change necessary for improvement (Grunow et al., 2024). This study seeks to understand the application of a continuous improvement process learned from a program implemented in partnership between a district and the outside organization- a university. The research questions guiding this study are:

1. What are the benefits and challenges of applying a continuous improvement process learned in a professional learning program to address complex problems of practice?

2. How does the professional learning program evolve to help school leaders navigate complex change to apply a continuous improvement process learned in a professional learning program?

This study looks across the first three cohorts of school-based teams to understand how leaders and leadership teams enact continuous improvement using a systems change framework to identify and assess the aspects of the program that enable and constrain continuous improvement in schools and to examine how these aspects operate across schools (Knoster, 1993; Lippett, 1987).

This study explores the implementation of a continuous improvement program, based on liberatory design (Anaissie et al., 2021), design thinking (Kelley and Kelley, 2013), and improvement science (Bryk et al., 2015: Hinnant-Crawford, 2020) called design improvement (DI). Anderson et al. (2023a) define continuous improvement by stating:

The “continuous” in continuous improvement relates to a commonality shared among almost all approaches to improvement that fall under the “continuous” label–the introduction of rapid and repeated tests of change that involve those directly affected by the changes. In improvement science, these rapid tests of change are typically called “PDSA cycles” for the succession of steps involved, plan-do-study-act (Langley et al., 2009). These rapid cycles of local change typically follow one of several systematic methods of introducing and monitoring change so that the learning from one cycle to the next is continuous and grounded in the everyday actions of those doing the work (p. 35).

The methodology of continuous improvement used in the program discussed in this paper is improvement science. However, the improvement science process is informed by two other continuous improvement approaches, design thinking and liberatory design. Design thinking informed the stages of the process (discovery to evolution). One of the attributes of design thinking is the human-centeredness. Human centeredness is a part of improvement science but less explicit throughout the process than it is in design thinking (IDEO, 2025; Kelley and Kelley, 2013). The process used in this program emphasized the use of empathy interviews in the discovery phase. The design thinking approach also encourages innovation, based on the learning from the users, in the development of strategies or change ideas over utilizing taken-for-granted solutions. This continuous improvement program encouraged the development of prototypes of original change ideas, built by the design team but based in practical and research knowledge, to reflect the needs within their context.

Liberatory design grew out of the design thinking approach but explicitly focuses on “addressing equity challenges and change efforts in complex systems” by creating “designs that help interrupt inequity and increase opportunity for those most impacted by oppression (Anaissie et al., 2021).” The twelve liberatory design mindsets (complexity, creative courage, relational trust, human values, healing, transform power, self-awareness, liberatory collaboration, recognition of oppression, fear and discomfort, learning through action, and share don’t sell) help ground the work in justice and equity by asking “who’s impacted?” and “who’s involved?” (Hinnant-Crawford, 2022) to “transform power by shifting the relationships” giving agency to the educators. These design principles of human centeredness, innovation, and liberatory mindsets undergirded how we went about the improvement science process.

A continuous improvement process begins with determining a problem of practice that needs to be addressed. Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson (2022) define a problem of practice as, “a gap between the current state and the ideal or aspirational state that requires both further investigation and targeted solutions to close that gap and move toward an ideal state (Bryk et al., 2015).” They go on to share that “problems stem from gaps in efficiency, quality, or (and) justice” (p. 297). These problems of practice tend to “emerge from systems designed to result in varying outcomes (Mintrop, 2015). And therefore, not only require multifaceted solutions but also a problem-identification process that begins with in-depth analysis to frame and define the problem” (Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson, 2022, p. 298).

The continuous improvement process used in this study is a disciplined approach (e.g., improvement science, design thinking, and liberatory design) to educational change that supported teachers, leaders, and researchers in collaborating to solve specific problems of practice through: (a) understanding a problem and the system that produces it through user-centered design (e.g., empathy interviews), causal and systems analysis, and the existing knowledge base (discovery); (b) focusing collective efforts on analysis, defining a theory of improvement with a clear and specific aim and identified drivers (interpretation), and development of solutions or change ideas (ideation); (c) testing and building evidence through measurement of processes and outcomes and short cycles of inquiry know as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (experimentation); and (d) spreading and scaling solutions, or bundles of solutions, that were found to be successful through iterations of PDSA cycles and willingly abandoning ideas that have failed (evolution). The continuous improvement process was intended to result in regularly collected and assessed data, closely linked to the aim of the theory of improvement.

Significance of the study

A potential limitation of current improvement strategies is the reliance on external “experts” to develop professional development programs of varying depth and breadth. Leaders, teachers, teams, or schools often engage in professional learning programs to improve student outcomes using highly developed external resources even though external providers may not know district and school practices, norms, and culture (Bryk, 2014; Coburn and Turner, 2011; Cohen-Vogel et al., 2015; Fishman et al., 2013). At the end of the program, which is usually determined by the amount of grant funding and not evidence of preparation for implementation, districts may expect educators to implement these strategies. In some cases, they may expect schools to implement the learning from the program with fidelity. Oftentimes, school leaders and/or teachers end up deciding whether to embed these practices or place the materials on the shelf as a reference (Bryk, 2014; Honig, 2006; Gutiérrez and Penuel, 2014).

Although these programs often introduce promising practices to the school, the practices are not always integrated into the daily work of the school (Dagenais et al., 2015; Redding and Viano, 2018). Unfortunately, educators often experience professional learning programs as compliance to appease their district supervisors and not a learning opportunity to improve practice sustainably (Finnigan et al., 2013; Valdez et al., 2020; Yurkofsky, 2021). In some cases, these programs are successful when the school are motivated to figure out how to make these practices part of the school’s systems and structures. This study hopes to illuminate how to support schools with managing the change and embedding the learning from a continuous improvement program into the systems within the school and district.

Theoretical framework and review of the literature

School improvement efforts to “turnaround” or “reform” schools, despite years of research, practice, and policy, have failed to make lasting, systemic change in schools (Bryk, 2014; Bryk et al., 2015). Fullan (2007) has long argued that there is a difference between introducing new reforms and creating organizational change. Change requires more profound shifts in the daily work of schools (Fullan, 2007; Kotter, 2007). For change to occur, there must be a focus on (a) developing relationships between stakeholders, (b) creating coherence in systems, (c) upholding a moral purpose, and (d) building knowledge (Fullan, 2007). Because change requires shifts in mindsets (Argyris and Schön, 1996, Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019), practices or habits (Hargreaves and Shirley, 2009), and culture or routines (Fullan, 2007; Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Hargreaves and Fullan, 2015; Grunow et al., 2024), it is hard to achieve and even harder to maintain (Elmore, 2016; Duke, 2006; Fullan, 2007; Hargreaves and Shirley, 2009).

Change theory (e.g., Kania et al., 2018; Lewin, 1947; Kotter, 2007) seeks to describe how and why groups of people engage in transformation. Traditionally, change takes time and can meet resistance, whether overt or covert. School leaders are change managers (Fullan, 2007); educators are regularly asked to learn new things, engage in programs or initiatives, and adopt districtwide practices. At the same time, schools are also often criticized for the slow pace of change. This plethora of attempts at change coupled with difficulty changing is in large part due to how change is introduced and managed.

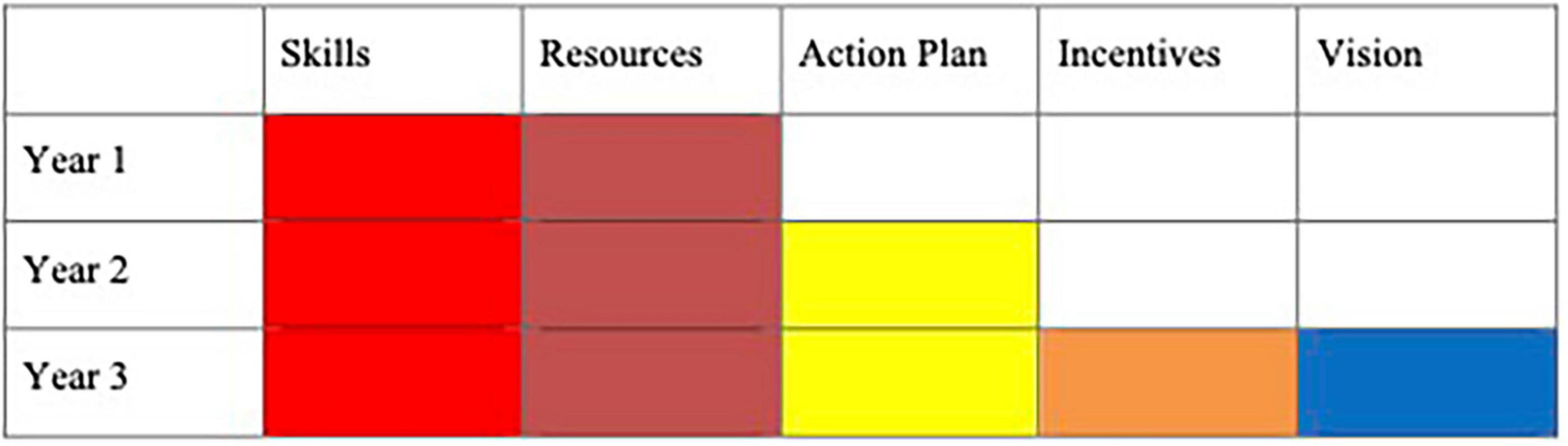

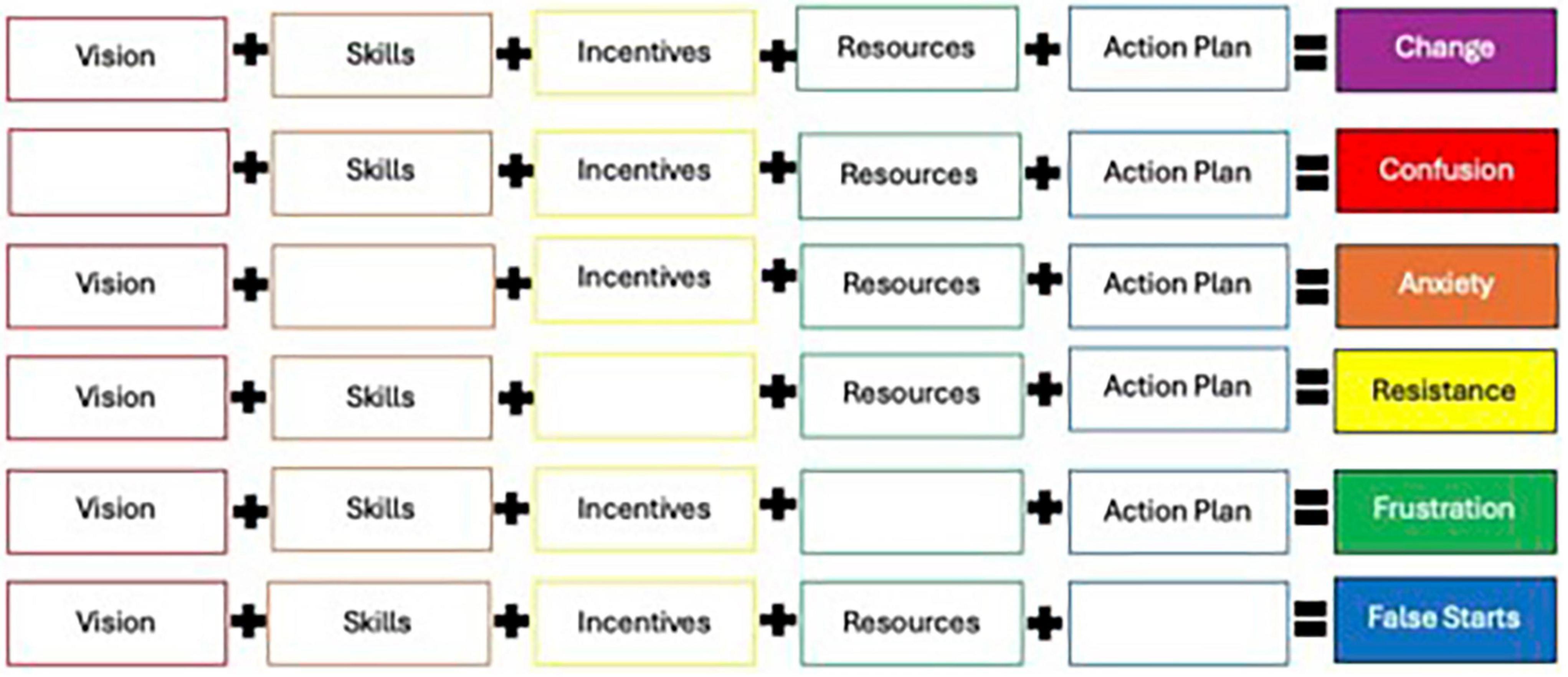

The Knoster-Lippitt model for managing complex change is a framework with five components influencing organizational change (Knoster, 1993; Lippett, 1987). The authors of the model suggest that if you develop all five of these areas, change will be achievable. If you are missing any of these areas, complex change will fail. Figure 1 shows a graphic of the framework first introduced by Lippitt but made popular by Knoster.

Figure 1. Lippitt Knoster model. This figure is from the source: The Managing Complex Change model was copyrighted by Dr. Mary Lippitt, founder and president of Enterprise Management, Ltd., is 1987.

The first component of this framework is a vision or the reason behind the change. Requests for change devoid of clear, strategic goals are less likely to be taken up as practice (e.g., Fullan, 2007; Kotter, 2007). If you are missing a vision or failing to communicate and share the vision, attempts at change will be met with confusion.

The second component is the skills or the knowledge necessary to ensure change. Asking educators to change without ensuring they have the skills to work in new ways will limit the ability to change (Anderson, 2015). If skills are not properly developed, attempts at change will lead to anxiety due to people feeling like they cannot do what is asked of them.

The third component is the incentives or the benefits of the change for both the organization and people in the organization. People need to understand how the change will make their work life better (Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Yurkofsky, 2021). If you are missing incentives, there may be no apparent reason for that effort necessary to learn new ways of working. Resistance will thwart change since change requires the motivation to commit precious time and energy to a new, untested practice.

The fourth component is the resources or the human, fiscal, and structural resources that support the change. A common mistake in change efforts is to not provide the resources necessary to implement that change (Anderson, 2015). If you are missing adequate resources, frustration will grow making change difficult.

The fifth component is the action plan or the way in which the change will be implemented and managed. Asking for change without providing the opportunity to plan for how that change can be integrated into existing work structures will make change unmanageable (Kotter, 2007). If you have no action plan, change will result in false starts that can, in turn, increase confusion, frustration, resistance, and anxiety.

Continuous improvement is an opportunity to introduce change to a school or a district by not only working to solve a problem but also teaching a process to solve future problems. The success or failure of continuous improvement in schools, such as improvement science, is in part dependent on how schools are introduced to the process and the readiness of leaders to manage continuous improvement. These five components of managing change require accompanying actions, structures, and processes to ensure that the vision is enacted; the skills are developed; the incentives are named; the resources are available; and the action plan is capable of being implemented and executed for success. In the program, these actions, structures, and processes must be built into the professional learning to ensure the leaders and design teams have the capability to manage change in their schools.

If schools are managing change in a manner that supports continuous improvement, there are certain routines, habits, and mindsets the educators should reinforce or transform.

Routines

Routines are central to change. Routines are the “repetitive, recognizable patterns of interdependent actions, carried out by multiple actors” (Feldman and Pentland, 2003, p. 95). Routines for problem-solving are necessary to implement and sustain equity-oriented continuous improvement. The relationship between the tools of improvement and the routines lead to the practices or habits that become part of the day-to-day work of improvers (Wilhelm et al., 2023).

These routines should create a learning environment, develop capacity-building conditions, create systems for improvement, and foster enabling conditions throughout the network or group of improvers (Anderson et al., 2023a,b). Schools that have more success with improvement develop common, transparent routines for systematic inquiry (Anderson and Ringer, 2024). Successful schools will also need to redesign predictable, shared routines that are not conducive to equitable learning. The only way to disrupt inequitable practice is to disrupt routines (Diamond and Gomez, 2023). As Diamond and Gomez (2023) state,

reimagining and redesigning organizational routines means seeing where white supremacy and anti-Black racism are embedded and dismantling them. To do his, we argue that organizations need explicit tools to slow down and engage in disciplined, critical reflection and action to transform their most fundamental aspects—shared organizational routines (p. 6).

Continuous improvement, when done with an equity-orientation, can provide the necessary inquiry and reflection and space for action planning necessary for changing routines. Shared organizational routines will need to model and promote a learning culture in which risk taking and experimentation feels safe, enable learning and professional behavior and practice, enable improvement capacity and infrastructure and develop an anti-racist and inclusive environment for all (Anderson et al., 2023b).

Habits

Habits are the things that improvers do and say that support improvement. Improvers must develop habits for problem-solving that include slowing down thinking and centering humans through inclusive social learning (Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Anderson et al., 2023a; Zumpe and Aramburo, 2023). Continuous improvement requires educators to be deliberate and intentional and take the time to consider past, present, and future before problem solving (Biag and Sherer, 2021). Habits must also ensure a human-centered, equity-orientation by gathering multiple perspectives and by addressing the experiences and feelings of users (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Zumpe and Aramburo, 2023).

Habits should lead to action through disciplined inquiry. Disciplined inquiry requires habits to keeping track of the work being done and to capture learning to inform improvement (Anderson et al., 2023a; Zumpe and Aramburo, 2023). The habits of improvers should establish a learner stance and learning culture by engaging in critical self-reflection, considering context and conditions, calling into question norms and practices that lead to inequities, and developing collective and shared norms, beliefs, and mindsets based on this criticality, contextualizing, and questioning (Anderson et al., 2023a,b).

Mindsets

Mindsets for continuous improvement must encompass beliefs about change, power, oppression, justice, cultural responsiveness and equity (Anderson et al., 2023a; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Yurkofsky et al., 2020). Mindsets consist of ways of thinking and shifts in thinking (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019). Zumpe et al., 2024 found that mindsets shifts were possible and that educators could learn to analyze problems through multiple perspectives with a systems lens. They stated, “New learning may lead to sustained changes in mindsets over time if new beliefs and practices are reinforced through ongoing learning experiences” (np). Improver mindsets for problem-solving (Leithwood et al., 1995) should believe that change is possible and that solving a problem can be done by taking a data-informed, systems lens (Anderson et al., 2023a; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Zumpe et al., 2024). Mindsets for an equity-orientation will question the status quo and push against oppression (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2023a; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023). Zumpe et al. (2024) also found that when continuous improvement was taught with an equity-orientation, educators “reflected on more oppressed and privileged aspects of their identity and wrestled with new understandings that acting as equity leaders would entail disrupting power dynamics and empowering others for collective learning and action” (np). The mindsets that improvers have when working to change should both encourage new approaches to improvement and a focus on improvement centers justice and equity.

Materials and methods

This paper, as part of a longitudinal, exploratory study, explored the responses of educators to continuous improvement and how leaders managed change to instill continuous improvement as part of the everyday work of the school. This cross-case comparison study explored data from three cohorts of school design teams engaged in a professional learning program focused on integrating continuous improvement into the habits of practice within a school. Case study research is highly contextual and bounded (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 2013; Yazan, 2015; Yin, 2018). Merriam defines a qualitative case study as “an intensive, holistic description and analysis of a bounded phenomenon such as a program, an institution, a person, a process, or a social unit” (p. xiii). In case study research, you can look within a case or across cases to determine themes and trends.

A cross-case study research methodology looks across cases to see what is similar or different in the various contexts to draw conclusions based on both trends and variation (Yin, 2018). This comparative design made sense to answer the research questions explored in this paper that seek to understand change across cohorts across years. In this longitudinal study, we treated each cohort of schools as in individual case or unit of analysis. We bounded and compared the cohorts of schools for the analysis in this paper. In this cross-case comparison, we prepared individual cases, looked at trends and variation with those cases, and then looked across cases for similarities and differences.

The program: site and sample

The sites and participants in this study participated in a one-year professional learning opportunity provided by the university, an approved provider, through state school improvement funds. After being identified by the district as eligible for turnaround funds, schools opted into the program through a state-led application process. The district is in a major metropolitan area and serves a majority students of color with Latine students making up around 50% and Black students making up about 14% of the student body. The schools in this study reflect these demographics.

The continuous improvement process used in the program was created by university educational leadership program faculty in partnership with leaders from the district school improvement team. University project leaders and faculty coaches co-designed the workshops and coaching sessions based on the shared project goals, scope and sequence, and feedback from the stakeholders. Each year university faculty served as program leaders and had regular meetings with the district employees responsible for supporting school improvement and supervising the tiered supports available to schools. For the first cohort, the planning team developed a schedule of events for school design teams. After the development of a draft agenda and resources for the workshops, these were shared with the other two faculty coaches for additional feedback, and then a final version of the workshop activities would be provided to the district project leads for final approval. This alignment of district goals, each school’s improvement plan, and the theory of improvement to be tested in the partnership was meant to be enriched through an iterative planning process.

The program, although always focused on continuous improvement, began with design thinking and then integrated improvement science. By 2019, the program sought to increase the equity-orientation and integrated liberatory design into the process. The continuous improvement process used in this program was divided into phases that allowed for the progression from problem identification to scaling measurable solutions (Bryk et al., 2015). Each school had a design improvement team, which included the principal and three to six additional school-based staff including assistant principals, deans of instruction, deans of culture, teacher leaders who serve as instructional leaders and coaches, teachers, and socioemotional support staff. From the launch of the program, there was a focus on team learning. The program began with a mix of workshops and coaching but over time moved toward a coaching-centric model.

Program cohort 1

The first year of this professional learning program officially began in September 2017 and concluded in June 2018. Twelve schools in one urban district participated in the first program cohort. The schools included nine elementary schools, one middle/high school, and two high schools with 35 school-based participants. In the first year of the partnership, the program built capacity through a series of six, bi-monthly, professional learning workshops. These workshops provided the opportunity to learn the continuous improvement model. Feedback from all participants was collected at the end of each workshop session and reviewed by both the university and the district. In addition to these workshops, each school team had the support of one of six dedicated faculty coaches who served as the school’s thought partner and facilitator throughout the duration of the program.

Program year 2

The second cohort of the professional learning program, including six schools (two middle schools and four elementary schools) with 24 school-based participants, began in August 2018 and concluded in spring 2019. Like year one, two of the university faculty coaches worked as program managers, working regularly with three district leaders from the large urban district, including the Director of School Improvement and two members of the district improvement team, to plan and iterate the program. Four coaches worked with one or two of the schools in the large urban district. The schools were also supported by instructional superintendents who attended professional learning sessions and sometimes met with coaches and schools. Finally, one university faculty member took the lead on developing the professional learning sessions and worked as a research associate on the project.

In addition to a kick-off event in June, there were six full- and half-day professional development sessions. The first one was a two-day training that took place in June. Then, the schools planned to come together in September, November, January, March, and May for delivery of new content; networked activities, such as consultancy protocols and small group presentations; and design team time to work independently and with coaches on planning for and reviewing data from the improvement science process. Mid-year the program decided to increase the number of coaching sessions and reduced the number of professional learning workshops.

Program year 3

The third cohort began the professional learning program in August 2019 and concluded in spring 2020. This cohort included eight elementary schools located in the one urban district with 29 school-based participants. With the third cohort, the program held one kick-off session in August and three professional learning workshops in the fall, winter, and spring. A new program lead reduced the number of coaches to two to focus on improving the program. The program model changed so that professional learning would take place in the coaching sessions and the workshops would be more of time for schools to receive targeted support on topics like measurement for equity and time for the schools to share their progress and conundrums with each other. Coaching was increased to three hours a month, usually resulting in two to three school-based design improvement meetings facilitated by coaches. Schools were encouraged to have a weekly design team meeting with or without the coach. Additionally, the decision was made to not engage instructional superintendents into the work on an ongoing basis but instead to report progress to them a few times a year.

Data collection

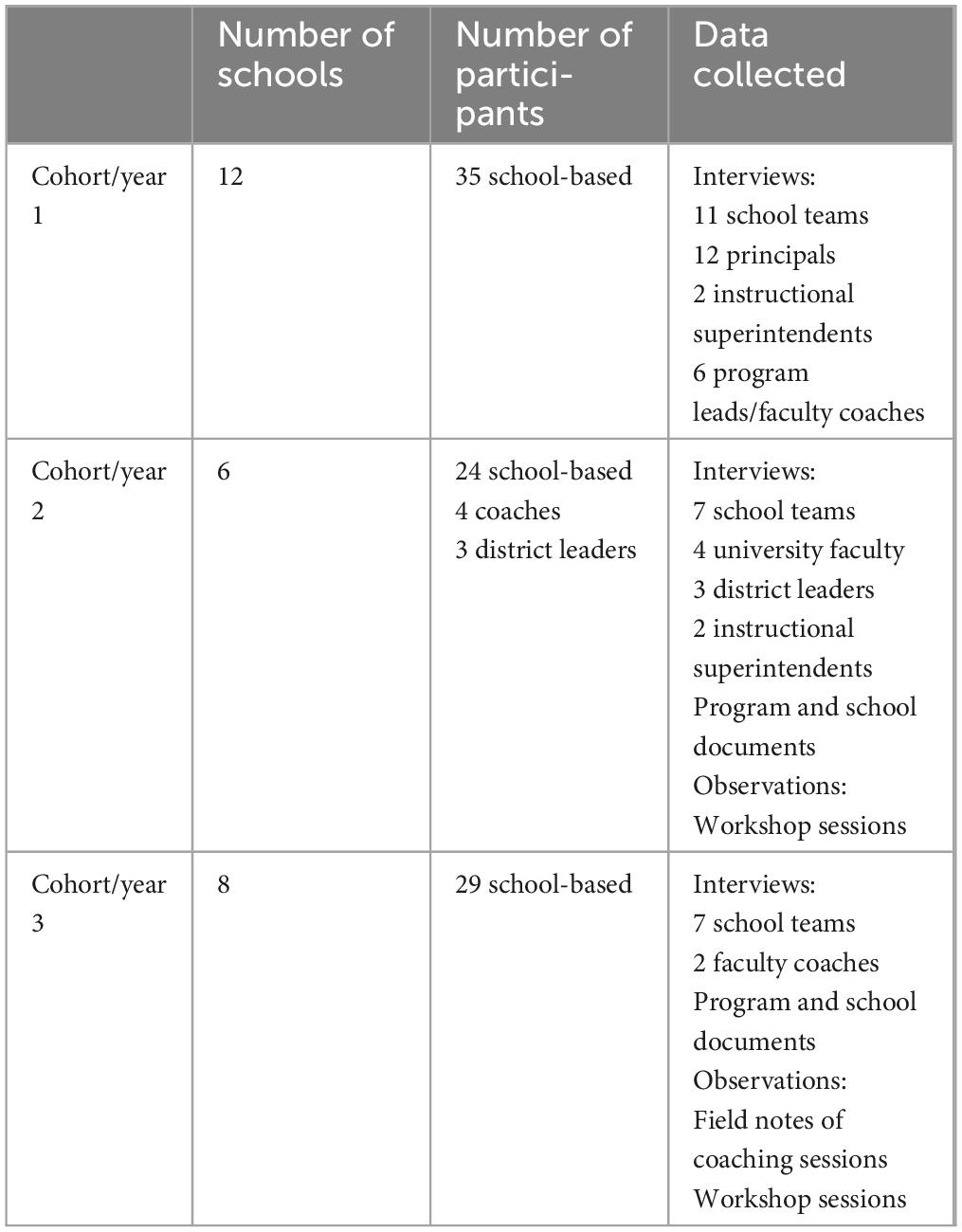

This study draws from data across three years (2017–2020). Table 1 presents a summary of the data collection.

Cohort one

The research team of one faculty researcher and three graduate students conducted thirty-to-sixty-minute interviews with all the design team participants at all 12 schools in May or June of 2017–18 school year. Three graduate students conducted the interviews- one of whom interviewed all faculty participants, and two of whom conducted all school-based interviews together at the school sites and district interviews over Zoom. Interviews with principals were done separately than the rest of the design team whenever possible, and the team interviewed all design teams as a group. At one school, the principal was the only participant interviewed. Additionally, the team invited all the instructional superintendents who supervised the school and came to all or some of the workshops to interview; however, only two out of nine instructional superintendents participated. Furthermore, the team interviewed all three members of the district leadership team and all six faculty members serving as coaches and/or project managers. There were three, aligned protocols for the university, district, and school-based participants, but all three protocols had interview questions about (a) describing the improvement work, including the selection of the problem of practice, changes in problem solving, benefits and challenges of the work, changes in beliefs about the problem of practice,; (b) the process, including helpful and challenging aspects of the DI process and conditions to enable the work; and (c) the program structure, including the role of coaches and workshops.

Cohort two

The faculty research lead conducted interviews with university faculty, who served as the project manager and coaches; district leaders, who served as project liaisons and instructional superintendents; and school design teams in May and June of 2019 using semi-structured interview protocols that aligned with the year one protocols. Six schools participated in the group interviews with a total of 24 school-based interviewees. We also interviewed all four university faculty, three district leaders, and two out of five instructional superintendents. Several requests were sent to the missing participants. Documents collected included those involved in the preparation and delivery of the professional learning activities. Graduate student researchers observed the whole group professional development sessions. Not all workshop activities were documented through field notes, but small group design team presentations were observed.

Cohort three

During the month of May 2020 after the last online coaching session, the faculty researchers conducted 30–45 min group interviews with the primary school-based participants at all eight schools using interview questions aligned with the year one and two semi-structured protocols. The researchers also interviewed the two faculty coaches for 60–90 min. During this third year, the documents collected also included artifacts from the program, including coaching notes from each session with the school team, documents and notes from university/district planning meetings, and documents from the schools (e.g., root cause analysis templates, empathy interview notes, driver diagrams (all versions), change idea prototypes, PDSA trackers, weekly meeting protocols, and other planning/meeting documents. Coaching notes included questions about what they were learning, how this process was different from how they worked before, how they were engaging users, and the systems and structures that helped or hindered the work. Coaches also reflected on any shifts in thinking or practice observed in that coaching session. In addition to these documents, the lead researcher and graduate student attended coaching sessions and completed a field note template with observations and analytical notes. The graduate student regularly attended coaching sessions at two of the schools and the faculty researcher attended meetings at all schools at least three times throughout the year (fall, winter, and spring or once per action period).

Data analysis

The three years of data were transcribed, uploaded, and coded with NVivo 12.0.

Cohort one

Since this was an exploratory study, the team inductively coded the interviews from cohort one (Saldaña, 2015). Three graduate students, including the two students who conducted the interviews and a third student who joined the project to assist with transcription, recorded and transcribed the interviews. The faculty researcher did an initial line-by-line coding and then categorized into broad categories (Saldaña, 2015). Categories included benefits, challenges, the improvement process, leadership practices and reflection, district support and role, and partnership. After determining the broad categories and codes based on the interviews, all transcribed inter views and documents were coded.

Cohort two

For cohort two, two graduate assistants coded a subset of the data, including university, district, and school team interviews. They used open coding to each establish a set of codes (Saldaña, 2015). Then, they met with the faculty researcher, who had also coded the same subset, and the two lists of codes were discussed, revised, and explored until they created a list of initial codes and definitions. Interrater reliability was calculated using a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.70 or above. The researcher compared these codes and categories to the year one codes and categories to complete the codebook. Based on this process, a codebook was created with parent and child nodes; then trained graduate assistants conducted first order coding using the codebook (Saldaña, 2015). The team divided the remaining interviews, grouped by school between the two graduate researchers, who open coded for additional child codes and added those to the codebook. A third graduate researcher then coded the field notes and aforementioned documents based on that codebook. Lastly, through second order coding, the third graduate student researcher and the lead researcher grouped the thematic data into categories (Saldaña, 2015).

Cohort three

Data was coded using the revised codebook from the 2018–19 study. A graduate researcher coded observational data and artifacts on an ongoing basis throughout the 2019–20 school year. All coaching notes were uploaded at the end of the month along with any additional field notes from the coaching sessions. After each of the three whole group workshops (November, January, and April), the graduate researcher coded the school power points reported of the work completed during each action period as well as transcriptions of the presentations, including follow up questions asked by other participants. Additionally, the team uploaded and transcribed meeting notes from the weekly meetings of the program lead and faculty coaches, as well as the monthly notes from the meetings between the faculty and district leads. At the end of the year after the group interviews, the graduate researcher coded the interview data.

Cross-case data analysis

The coded data from the three years were them turned into case reports, grouped by school and including the available data from the school design team, the district partners, and the university faculty. Then a cross-case comparison was done within each parent code in the codebook. Codes with high frequency across the years were categorized and compared across years. Themes were determined based on categories present in all three cohorts.

Limitations

This study has limitations to consider. First, this study was conducted in one district with a specific demographic composition, so the applicability to other contexts may depend on the similarity or differences from that context. Second, this study was conducted by a member of the program team, who also served as a coach the first two years and the program lead the third year; however, that involvement could also be considered a strength due to the close knowledge of the program and the schools. Third, many interviews were done with design teams, potentially favoring some voices in the group, such as the school leader, or influencing the responses of other team members, due to power differentials between roles. However, the teams had worked closely all year and had been encouraged to communicate openly with each other and with the design improvement coaches to foster their continuous improvement work. The fourth potential limitation is that this qualitative study was happening in real time and so participation and data collection cannot be controlled and standardized across years; however, this type of study allows us to capture the true day-to-day work of school, accounting for the rich context and variability of schools. Finally, this paper does not get into individual schools and how, why, and to what extent they changed or improved. Those data are addressed elsewhere to limit the length of this paper (e.g., Anderson and Ringer, 2024).

Trustworthiness and credibility

This study maintained trustworthiness and credibility through (a) the triangulation of data sources including interviews with coaches and schools; documents, observations, and interviews and (b) member checking by sharing case profiles back with schools, district leadership, and coaches for their review. This study was conducted with institutional review from both the university and the district and the principal for each school consented to be part of the research. Individual participants were given the opportunity to withdraw from the study meaning they would remain on the team, but their data would not be collected. No one opted out of participation. The faculty researcher was also a coach for the first year and a half but then transitioned solely to a research role. The trained team of graduate assistants helped mitigate the potential bias and subjectivity of the researcher.

Results

This findings section begins with a high-level overview of the results of the continuous improvement program. Then, the section will present challenges in professional learning and partnership alignment followed by a description of the changes in program structure to address those challenges. Finally, this section concludes with emerging benefits of the program with an emphasis on the evolution of those benefits from cohort to cohort.

Application and management of the continuous improvement program

For cohort one, the process showed promise, but no school applied all five phases of the process (discovery, interpretation, ideation, experimentation, evolution) or captured measurable improvement. Many of the schools suggested there were tools and ideas, particularly related to causal analysis and understanding the problem, that they would continue to use (e.g., PDSA cycle, root cause analysis, fishbone diagram, empathy interviews). In about half of the schools, the team used program time to plan and implement improvement activities but did not adhere to or complete all the phases of the equity-oriented, continuous improvement process. Each school did define a problem of practice and implemented at least one prototyped solution. None of the schools embedded this process into their daily work. Every school identified promising improvements they had implemented this year, but they did not have the data/evidence to track what worked under what conditions. Their evidence was mainly anecdotal, and most schools did not have incremental measures to identify whether to adapt, adopt, or abandon change ideas.

For cohort two, progress was made in adhering to the process, but measurement was still a struggle. For the schools in cohort two: (a) All of the teams showed evidence of understanding the process and using the accompanying vocabulary and tools; (b) All of the teams tested one or more change ideas using PDSA cycles, but most of them did not capture the PDSA cycles using the supplied tracker; (c) All of the teams showed evidence of progress within at least one driver; (d) None of the teams were able to effectively track the Aim and were not able to connect the Aim to the change ideas. All of them were able to articulate the necessity of tracking the Aim and to explain how that would benefit improvement, and all but one school discussed plans to do that moving into the next academic year; and (e) None of the teams completed the evolution phase, where they would spread change throughout the school.

The third cohort applied the continuous improvement process to their improvement work in a more integrated and systematized manner than the year one and two cohorts. All schools in the cohort were asked to select a problem related to the school Unified Improvement Plan (UIP) and district goals that would address an aspect of the opportunity gap and disrupt inequitable practices. Every school in the cohort understood the process, could explain the process, and could use the accompanying vocabulary to problem solve, engage in change, and address their problem of practice. All the schools in cohort three revised their driver diagram, tracked progress toward their Aim, used the PDSA tracker, and had conversations about these data on an ongoing basis. The schools all tested more than one change ideas through iterated PDSA cycles. Six of the eight schools achieved their Aim by March 2020; and the remaining two schools were on track, prior to the pandemic.

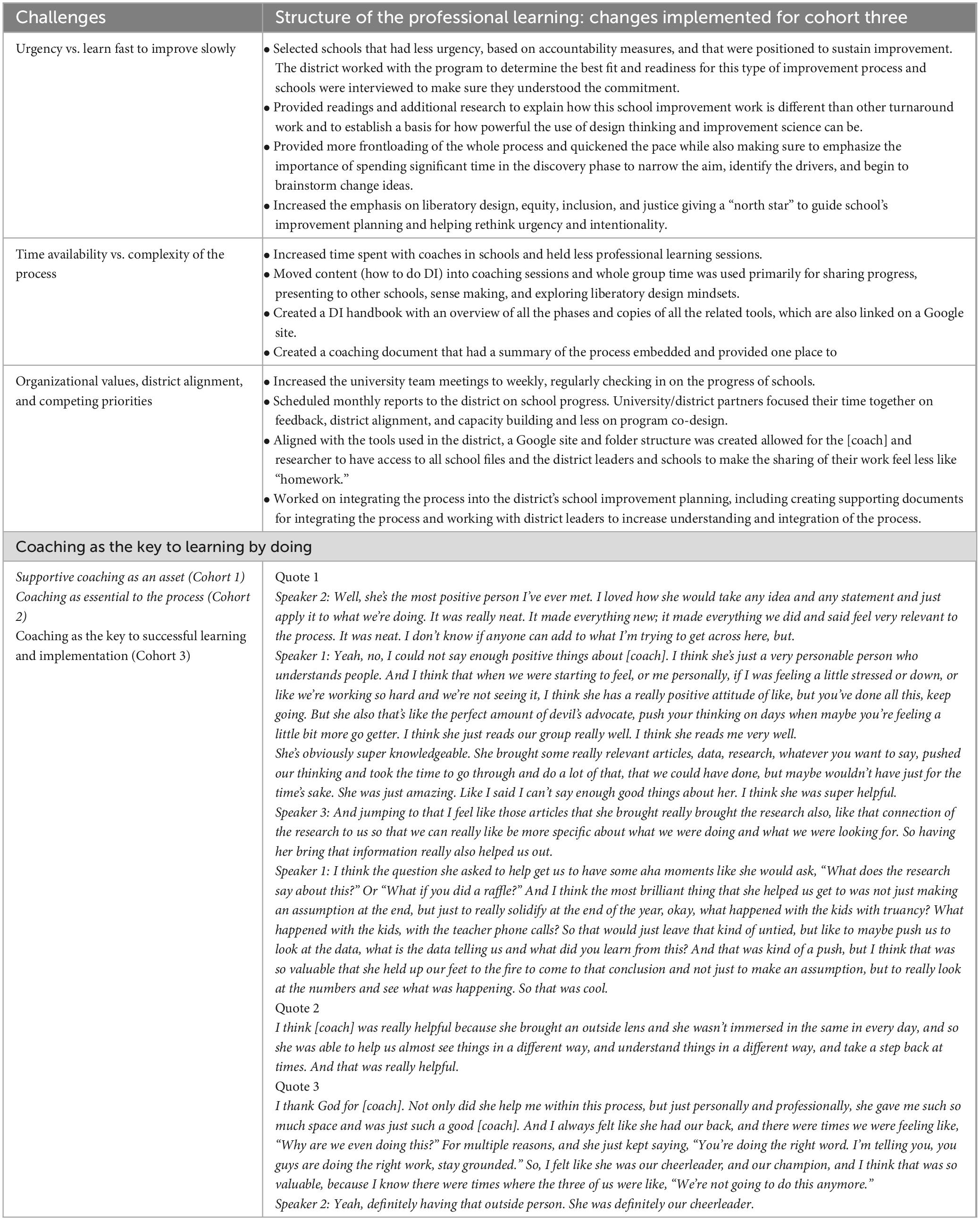

Challenges in professional learning and partnership alignment

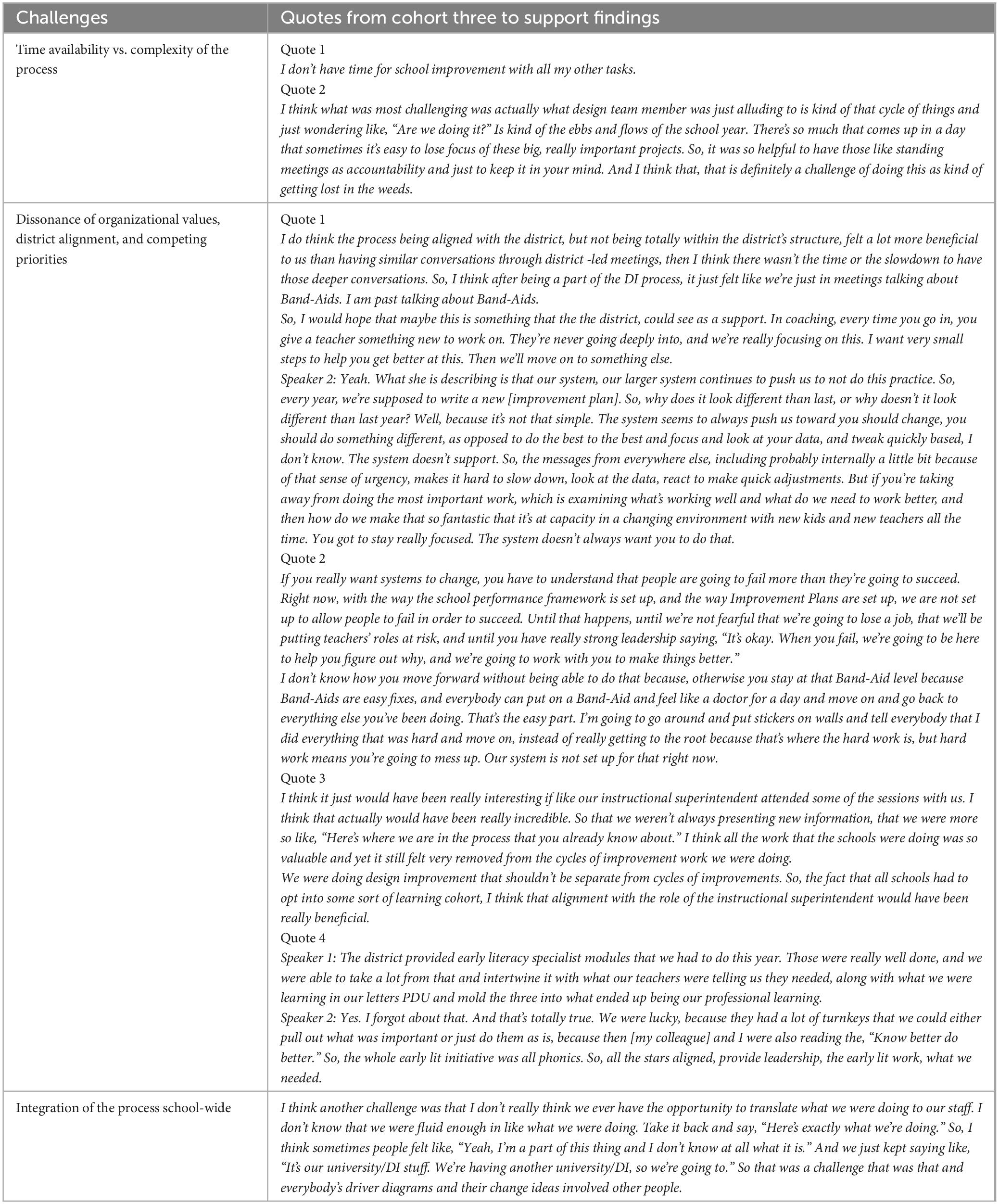

Three main challenges remained concerns across all three cohorts, but to a lesser degree, in cohort three. These challenges were (a) the tension between the time available and the complexity of the process, (b) the alignment between the process and district priorities resulting in competing priorities, and (c) the capability to spread the learning school-wide. Table 2 includes representative quotes from the third cohort to show how these challenges continued to resonate.

Time availability versus process complexity

In cohort one, schools struggled with commitment to the process. In many cases, the school teams saw promise but were not convinced that the time necessary to do improvement work was going to be worth the results, particularly with the large number of expectations and demands on their time. A common challenge across the schools was the allocation of time necessary to successfully learn the process and work toward solving the problem. Figuring out how to get started on the work and how to integrate this work into their already overwhelming schedules proved difficult. Many of the schools mentioned that they had a slow start to implementation because the effort and time required in the discovery, interpretation, and ideation phases was detailed and extensive and hard to add to their workloads.

Participants suggested this lack of commitment was also due, in part, to a failure to fully explain how this process was different from other “turnaround” providers and to fully describe the process in enough detail for them to understand where the process was headed. There were some participants who were overwhelmed by the complexity of the work and were uncomfortable with the lack of clear structure inherent to this type of improvement work. Although some felt it was a welcome change from the other turnaround providers, others suggested that they would have preferred being told by how to solve their problems and being given very structured protocols, similar to the style of existing improvement service providers.

Additionally, several schools mentioned that they didn’t know how or why they were selected for this program. A few mentioned how the perceived stigma attached with the program was difficult to overcome, leading to a slow start to implementation. District leaders noted that schools opted into the program through an application process, but the connection between this process and the program seemed to be unclear to some of the schools.

Another challenge identified at the end of cohort two was that the length of the program was not long enough to be able to learn all the necessary phases, implement them, and systematize the learning all in one year. Many of the school suggested that it took a year to learn the process and felt that it would not be until the following academic year that they began implementing the process. Every school suggested that they needed ongoing support to systematize the process. Cohort three while still grappling with the challenges of time and complexity, started to suggest that the benefits of intentionality, deeper understanding of a problem, and more collaboration and teamwork, which are discussed in greater detail later in this section, outweighed the concerns about making time and space for the work.

Dissonance of organizational values, district alignment, and competing priorities

In cohorts one and two, the teams found there was not time to ensure that this process was embedded into the improvement work of the district, and several schools suggested that the process was not aligned with the district expectations for improvement planning and monitoring. During the first cohort, there was some dissonance between the organizational values of higher education and K-12, including the sense of urgency that goes along with accountability and the deliberateness that goes along with research. Several schools mentioned that the core principles of the continuous improvement process were not always congruent with messages from the district around urgency and accountability. The university and district worked closely together to design the professional learning program and the tension around going slow to get better came up regularly. Relatedly, many schools did not feel like their instructional superintendents, who were their direct supervisors, understood or supported this work. For instance, one school shared that their instructional superintendent saw this as just another program that the school should ignore to focus on their real priorities. They also did not feel like the messaging of learning from failure and slowing down to get better were aligned with the accountability-driven culture of the district.

These same concerns continued to be a challenge with the second cohort. However, by the third cohort, these concerns had largely shifted. Although the challenge of competing priorities remained, the teams were less focused on being overwhelmed by the process and more focused on the enabling conditions in the district. For instance, the schools were concerned with the allocation of time necessary to engage in the process and the competing priorities, particularly as related to district-mandated school improvement planning. The schools, instead of rejecting the continuous improvement process due to a lack of alignment, supported integrating it into district practice. Some schools suggested there were too many improvement processes required of them and reinforced that they wished the district could integrate the process into district improvement planning making the work internal to the district. There was also a desire for a district culture that would allow for failed ideas and slower but more meaningful change.

The third cohort also found it challenging that district support providers were not regularly engaged in the work. Several schools mentioned they lost time explaining the improvement work to district leadership instead of the district leaders being directly engaged in the work. Two schools discussed how the district supported and reinforced their work and helped with data analysis. The main ways district leaders engaged in the process were to observe the PDSA cycles and give feedback and to provide, by chance, resources and training (e.g., phonics professional development, culturally responsive teaching professional development) that helped to inform the school’s theory of improvement.

Integration of the process school-wide

The schools also discussed the challenge of sharing the process with the staff. This concern was not as prominent in cohort one because they were struggling to begin to apply and implement the process. By cohort two, all schools indicated that the role of teachers and staff was limited and that the work was mostly done within the design team. Some schools engaged teachers on a more regular basis and had several teachers involved with the design team. Potential reasons the participants suggested for not engaging more staff included: (a) the need to develop a deeper understanding of the process before leading others in the process, (b) lack of time and structures for integrating the process schoolwide, and (c) a desire to buffer the teachers and staff from additional demands. The schools suggested that the process was not automatic enough after one year, and they needed a deeper knowledge to train others and to explain the work before expecting that people’s time and energy focus on the improvement work.

Changes in program structure

The program structure required constant tinkering in response to feedback to address these challenges to ensure greater ability for the design team to manage change in their building. We needed to address the incongruence with the vision, skills, incentives, resources, and action planning to better equip school leaders and increase the benefits of this continuous improvement process. Table 3 shares some of the changes that were implemented to address the challenges.

Table 3. Implications of the findings from cohort one and two for the structure of the professional learning for cohort three.

Across all three years, the schools identified that improvement coaching was key to their understanding and engagement. The first cohort identified coaching as an asset to the program and the style of coaching indicative of the partnership (e.g., student-centered, asset-based, and equity-centered) as supportive. The coaching was more sporadic at that time, only occurring once between each of the workshop sessions. There was not a clear agenda or a set of expectations for coaching meetings, and they varied in their success, often depending on if the school had applied the process at all between the workshop and the coaching session. The second cohort also found coaching as essential to the process. While working with the second cohort, program leads decided, based on feedback from a school leader, to shift the model to more on site coaching (three times a month) and less whole group convenings. The third cohort began the program with this coaching-focused model and expressed that coaching was the key to successful learning and implementation of the process. This coaching model is explored in detail in another paper.

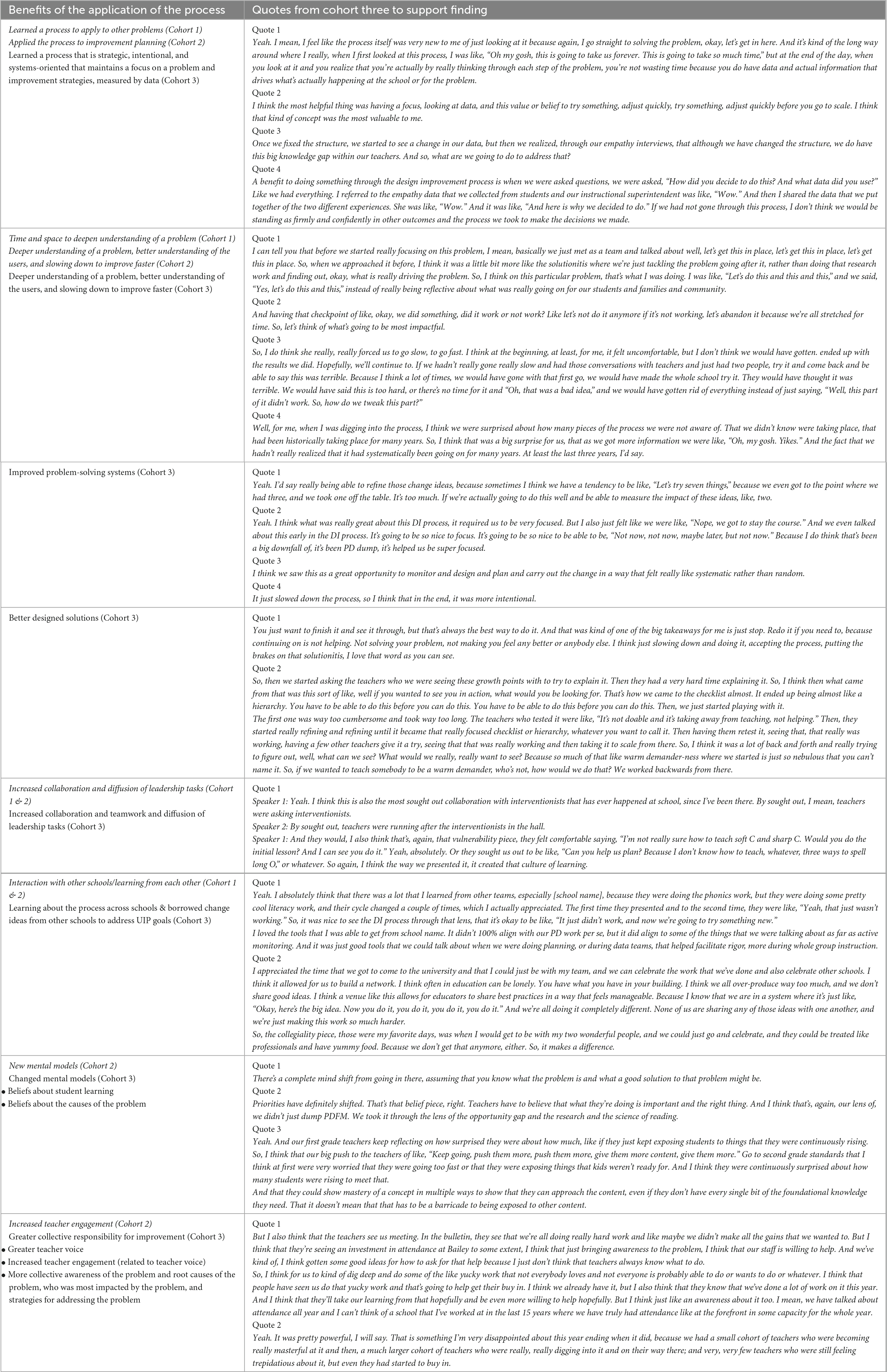

Benefits of the continuous improvement process

Even in cohort one when these dilemmas surfaced, the schools felt there were strengths of this work. The findings from cohort one mentioned the following benefits: (a) the leaders learned a process that they believed that could apply to other problems and the process gave the time and space to deepen their understanding of the problem leading to deliberate, deep, and intentional change; (b) the process led to within school and across school learning and collaboration by increasing collaboration and diffusion of leadership tasks within their school and fostering interaction with other schools was helpful, even when they were not working on the same problem, because it helped them articulate their thinking and gain different, informed perspectives. There were two benefits not identified by the first cohort that began to emerge with the second cohort and became more established with the third cohort: (a) shifting mental models and mindsets and (b) greater collective responsibility for improvement. These benefits continued to develop in subsequent years of the program. Table 4 captures representative quotes for each of the benefits which will be summarized after the table.

Deliberate, deep, and intentional change

A benefit present even in cohort one that strengthened over time was that the schools learned a process that is strategic, intentional, and systems-oriented that maintained a focus on a problem and measured improvement strategies. The first cohort identified that a benefit of this process was the time and space to deepen understanding of a problem, although making that time and space was in many ways an insurmountable challenge for that cohort. Across all three years, the school recognized the benefit of slowing down. The idea of solutionitis and of the need to identify root causes resonated with the leadership teams. The second cohort found the process led to a deeper understanding of a problem, better understanding of the users, and slowing down to improve faster. They were able to more explicit about the process and to use common language. The third cohort also identified this complexity and found that empathy interviews were one of the most valuable tools of process. The third cohort also started to discuss how the program focused on (a) learning a process versus being given a solution, (b) improving systems for problem solving, and (c) designing better solutions.

Another benefit identified by the leaders was that they were learning a process to be applied in their work outside of this professional learning. The first cohort mentioned that they learned a process to apply to other problems. The second cohort also made this point; however, the second cohort had only begun to see how this process could be applied to their district improvement planning. The third cohort suggested that they learned a process that is strategic, intentional, and systems-oriented that maintained a focus on a problem and improvement strategies measured by data. The benefit of problem-solving and improvement was consistent, even during early programming stumbles, but the depth of their understanding of how to use the process for improvement deepened over time. The third cohort leaders also perceived that this process was helping them be more focused and targeted. They felt that by staying focused on the problem and on root causes, they were able to be more systematic instead of arbitrary in their responses to long-standing problems of equity and inclusion. They also felt that their solutions showed improvement, and that they designed more adaptive instead of technical solutions, aligned to the problem, and improved through iteration.

Within school and across school learning and collaboration

The process increased collaboration, diffusion of leadership tasks, and teamwork. The first and second cohorts surfaced that the process improved their collaboration and shared leadership. The third cohort also added that it increased teamwork. By the third year, the teams suggested that they were (a) communicating more clearly with staff, (b) making more time for joint problem-solving, (c) focusing on team building, (d) increasing collaborative decision making, and (e) giving structure to leadership team.

The first and second cohorts found the opportunity to interact with other schools and to learning from each other as benefits of the program. At this point, they were largely connecting over team building activities or as participants in consultancy protocols, and some schools did not feel that was as meaningful as it could have been. By the third cohort, the emphasis was on cross-school learning and schools began mentioning borrowing change ideas from other schools to address improvement goals and connecting with other schools as a collective force of improvement.

Shifting mental models and mindset

There were examples of shifts in thinking about the beliefs about the causes of the problems and the beliefs about student learning. By cohort three, half of the schools explicitly mentioned that they had a mindset shift or that they uncovered underlying assumptions behind the problem. The schools began with a problem of practice, but, through the process, that problem was redefined. The process required them to rethink how they had framed the problem or to rethink the drivers to identify mindsets as important to the improvement work.

Greater collective responsibility for improvement

Lastly, there was a greater collective responsibility for improvement. Examples of this were (a) greater teacher voice, (b) increased teacher engagement (related to teacher voice), and (c) more collective awareness of the problem and root causes of the problem, who was most impacted by the problem, and strategies for addressing the problem. All but one school found that teachers were more engaged in the improvement work when they were asked to be on the design team, asked to provide data to help inform the DI process during the empathy interviews, or when they were asked to test out the change ideas. Teachers’ engagement in the PDSA cycles increased because of their input into the change idea.

Discussion

This paper does not get into the specifics of the professional learning or explore each school’s improvement process in depth. Those topics are discussed in other companion papers from this seven-year, longitudinal study (e.g., Anderson and Davis, 2023; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Anderson and Ringer, 2024). This cross-case comparison of the first three cohorts engaged in a continuous improvement professional learning program that facilitated a process to solve a complex problem of practice and to learn a process to apply to future problems surfaced the challenges and benefits as well as some programmatic structures that evolved to help ensure the teams could manage the complex change process. The purpose of this paper was to explore, at a high level, the progression of the development of the program across each cohort to ensure that leaders could engage in change by overcoming challenges and maximizing benefits. In this discussion, I will first explore each research question, exploring question one through the literature on mindsets, routines, and habits and question two through Fullan’s (2007) change tenets. Then, I will examine the relationship between the two questions using the theoretical framework for managing complex change before sharing overall implications for practice and research.

RQ1: what are the benefits and challenges of applying and managing a continuous improvement process learned in a professional learning program to address complex problems of practice?

There were three primary challenges found in this study: (a) the tension between the time available and the complexity of the process, (b) the alignment between the process and district priorities resulting in competing priorities, and (c) the capability to spread the learning school-wide. These three challenges all had to do with the teams’ commitment to the process as a lever for change. The capacity of each school to make time for new learning and to navigate the competing priorities was heavily dependent on the mindsets of the educators (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Leithwood et al., 1995); Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Yurkofsky et al., 2020; Zumpe et al., 2024). The educators needed to believe in the value of analyzing problems through multiple perspectives with a systems lens (e.g., Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Zumpe et al., 2024). Their mindset needed to change to dedicate the time and energy to the development of new routines or to rethink how existing routines could be used in new ways to reach their improvement goals and to spread learning schoolwide. Spreading schoolwide learning was ultimately about developing habits of social learning and modeling and promoting a learning culture to engage the educators in the school (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Zumpe and Aramburo, 2023).

Over time, the program helped the teams develop the habits of improvement leading to the four primary benefits found in this study: (a) deliberate, deep, and intentional change, (b) within school and across school learning and collaboration, (c) shifting mental models and mindsets, and (d) greater collective responsibility for improvement. Creating the time and space to deepen their understanding of the problem was dependent on the development of new habits and routines in order to slow down and be systematic (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Feldman and Pentland, 2003; Grunow et al., 2024; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Wilhelm et al., 2023; Zumpe and Aramburo, 2023). The school leadership teams needed to shape their learning environment and became more of a learning culture. When they made these shifts that lead to a better application of the process and improved program outcomes. This deliberate, deep, and intentional change also required a mindset shift, that while at first uncomfortable, was later welcomed as they learned to analyze problems through multiple perspectives with a systems lens and to slow down thinking and avoid solutionitis (Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Yurkofsky et al., 2020; Zumpe et al., 2024). This intentional change was linked to an increase in collaboration and more diffusion of leadership tasks. These shifts in who was responsible for the problem and how they thought about collective responsibility required developing new habits and routines.

Shifting mindsets was both a benefit of the continuous learning process and necessary to realize the other benefits of the program. As they learned to systematically analyze problems centered on people’s experiences and to question and problematize oppression and power, the teams increased their equity-orientation (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Zumpe et al., 2024). Over time, the challenges became less formidable in part because the benefits helped to mitigate the impacts of the challenges. This shift was also due in large part to the programmatic changes addressed in research question two.

RQ2: how does the professional learning program evolve to help school leaders apply and manage complex change?

The main way in which the program evolved was increased time spent with coaches in schools and held less professional learning sessions. This coaching model helped to developing relationships between stakeholders (Fullan, 2007). As the school teams strengthened their relationship with the coach, they also strengthened their relationships with each other, making it easier to manage the complex change. There was also a change in whole group time that led to an emphasis on presenting to other schools, sharing progress with each, and sensemaking together, which lead to relationship-building across schools.

As knowledge increased, the schools became more open to change (Fullan, 2007. To increase knowledge, the program provided readings and additional research to explain how this approach to school improvement was different than other turnaround work and to establish a basis for the power of design thinking and improvement science. We also created a handbook with an overview of all the phases and copies of all the related tools, which were linked on a Google site. We also learned to help the teams understand the big picture of the work by proving more frontloading of the whole process and moved content (how to do improvement) into coaching sessions. Lastly, we quickened the pace of learning while also making sure to emphasize the importance of spending significant time in the discovery phase to narrow the aim, identify the drivers, and begin to brainstorm change ideas.

As we changed the programming to meet their needs and to address previous challenges, the program created more coherence in systems (Fullan, 2007). One major way we helped with coherence was by creating a coaching document that had a summary of the process embedded and provided one place to access program materials. We also focused on the partnership and increased the university team meetings, scheduled monthly reports to the district, and focused our time together, across university and district, on feedback, district alignment, and capacity building and less on program co-design. We also aligned with the tools used in the district, a Google site and folder structure was created allowed for the coach and researcher to have access to all school files and the district leaders and schools to make the sharing of their work feel more natural. We also worked on integrating the process into the district’s school improvement planning, including creating supporting documents for integrating the process and working with district leaders to increase understanding and integration of the process.

Lastly as we increased our emphasis on equity and liberatory design, the moral purpose became clearer strengthening the selection of problems of practice and creating more critical self-reflection as seen in their shifting mindsets (Fullan, 2007). The emphasis on liberatory design, equity, inclusion, and justice gave us all a “north star” to guide each teams’ improvement planning by helping rethink urgency and intentionality. By purposely embedding equity checkpoints, based in the work of Hinnant-Crawford (2020) and liberatory mindsets (Anaissie et al., 2021), the school teams became not only committed to improvement but also to disrupting systems of oppression.

RQ 1 and 2: evolution of the program to navigate complex change by overcoming challenges and leveraging benefits

The managing complex change framework (Knoster, 1993; Lippett, 1987) was both applied to understanding what structures that the program needed to provide to schools (RQ2) as well as the capacity the schools and district needed to develop so that the benefits outweighed the challenges (R1). Changes in program structure over time, or RQ2, needed to address the challenges identified in response to RQ1: (a) time availability versus process complexity, (b) dissonance in organizational values, district alignment, and competing priorities, and (c) integration of the process school wide.

Coaching was a key lever to delivering professional learning that addressed the components of managing complex change. Successful implementation is about change management at the level of the professional learning program and the unit of change to be impacted by that program, which in this case, was the design teams at the schools. For people to take up continuous improvement, we must attend to how we are addressing the habits, mindsets, and routines that the schools will engage in within the professional learning program habits, mindsets, and routines. See Figure 2 for a discussion of how the program addressed complex change over the three years.

The first cohort was given some skills and resources, but the learning was not tied to a vision, resulting in confusion (Knoster, 1993; Lippett, 1987). Along with a lack of a clear vision, the incentives were not made clear, so schools resisted by not making time and space for the continuous improvement work. The action plan was not clear either, so there were false starts that needed to be redirected by the coach. The participants were curious about the potential of the process; however, the lack of an action plan and underdeveloped resources and skills did leave the participants frustrated. Schools took up parts of the process and resonated with some of the learning, but no one made it a part of their day-to-day work. The second cohort had skills, resources, and an action plan but incentives were missing, so there was still some resistance. Additionally, the vision, especially the shared vision between the university/district partners and the district leadership, was still unclear, so confusion continued.

The third cohort had the vision, skills, resources, action plan, and incentives to engage more readily with the process (Knoster, 1993; Lippett, 1987). Their confidence in the process increased, and they started talking about continuous improvement as the primary work of schools and school leaders. This cohort did span the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted human and fiscal resources, so there was some frustration that emerged. This study focused on comparisons at the cohort level, but additionally, while the program provided consistent resources, the schools within each cohort varied by human and time resources, so they faced different levels of frustration and potential resistance to change. Four of the schools in the third cohort opted to stay for a second year in the program during remote learning.

By providing the components to manage complex change, this program was able to help schools maximize the benefits (a) deliberate, deep, and intentional change, (b) within school and across school learning and collaboration (routines), (c) mental models and mindset shifts (mindsets), and (d) greater collective responsibility for improvement (habits). We know the importance of mindsets (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Leithwood et al., 1995); Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Yurkofsky et al., 2020; Zumpe et al., 2024), habits (Anaissie et al., 2021; Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Zumpe and Aramburo, 2023), and routines (Anderson and Ringer, 2024; Anderson et al., 2023a,2023b; Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Feldman and Pentland, 2003; Grunow et al., 2024; Wilhelm et al., 2023) in the success or failure of the implementation of equity-oriented, continuous improvement processes. The program needed to create those habits, mindsets, and routines to ensure that school could manage the complex change of continuous improvement.

Implications for practice

This study provides a detailed description of challenges and benefits of the practical application of professional learning that has direct implications on mindsets, habits, and routines. There are several practical implications of this study. The first suggestion is to make sure that there is a clear vision for the process and program and that the incentives of this process are shared and emphasized with participants. The competing demands for school leaders are abundant and to avoid being just another initiative that is emphasized briefly and then replaced by another new initiative, the program leaders need to make sure to attend to the capacity building necessary for the leaders to embed this work into their day-to-day work and to support leaders by ensuring they have the means to means to manage change (e.g., resources, action plans, skills) (Valdez et al., 2020). Collecting and responding to participant feedback, which is something the program leads did both ongoing and at the end of the year, is necessary to create a professional learning experience that meets the needs of the educators. Without these data, they would not have been able to make adaptions and adjustments that shored up the gaps in programming and mitigated the challenges. All these implications support the idea that implementation of new ideas and processes must be well thought out and monitored to ensure that complex new learning and new initiatives are integrated into the system, through routines, mindsets, and habits. Even in a district/university partnership, the alignment with other district proved difficult due to the size of the central office. Program leads need to plan for significant time to work with district partners to embed the work in the district.

Implications for future research

This study is exploratory and was designed to capture the implementation of continuous improvement in real time. This program was an early adopter of the improvement science (Bryk et al., 2015) and design thinking (Kelley and Kelley, 2013) and additional studies should look at how specific features of a variety of continuous improvement (e.g., Yurkofsky et al., 2020) influence implementation. Further, this study calls for additional research on whether the benefits increase over time, which benefits are most relevant to change, and whether benefits can be institutionalized into the system without coaching as an outside support.

Conclusion

For improvement teams to apply, implement, and integrate continuous improvement, the programs and initiatives that help to introduce the process to schools must be mindful of the development of the capacity to manage complex change. Program leads must be sure to gain understanding of the participants, their prior experience, and their experience with the process. The goal should be to ensure that the program learning is part of the quotidian work of the educators to maximize systems change. By attending to managing change, that goal has the potential to be met.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Denver IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anaissie, T., Cary, V., Clifford, D., Malarkey, T., and Wise, S. (2021). Liberatory Design. Available online at: http://www.liberatorydesign.com (accessed January 25, 2025).

Anderson, E. (2015). Leadership Practices and Essential Supports: A Comparative Case Study of a School Improvement Effort Before and After the Implementation of a School Improvement Grant (SIG). [Doctoral dissertation]. Virginia: University of Virginia.

Anderson, E., and Davis, S. (2023). Coaching for equity-focused continuous improvement: Facilitating lasting change. J. Educ. Change 25, 341–368. doi: 10.1007/s10833-023-09494-6

Anderson, E., and Ringer, J. (2024). Improvement science as sustaining practice: A cross-case comparison of thriving during the pandemic. Front. Educ. 9:1310754. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1310754

Anderson, E., Cunningham, K. M. W., and Eddy-Spicer, D. H. (2023a). Leading Continuous Improvement in Schools: Enacting Leadership Standards to Advance Educational Quality and Equity. Milton Park: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9781003389279

Anderson, E., Cunningham, K. M. W., and Richardson, J. W. (2023b). “Designing a multi-level learning trajectory for sustaining continuous school improvement: Lessons for transformative organizations,” in Continuous Improvement: A Leadership Process for School Improvement, eds E. Anderson and S. Hayes (Charlotte: Information Age Publishing).

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. (1996). Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice. Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Biag, M., and Sherer, D. (2021). Getting better at getting better: Improvement dispositions in education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123:2598. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300402

Bryk, A. S. (2014). 2014 AERA distinguished lecture: Accelerating how we learn to improve. Educ. Res. 44, 467–477. doi: 10.3102/0013189X15621543

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., and LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Coburn, C. E., and Turner, E. O. (2011). Research on data use: A framework and analysis. Meas. Interdiscipl. Res. Perspect. 9, 173–206. doi: 10.1080/15366367.2011.626729

Cohen-Vogel, L., Tichnor-Wagner, A., Allen, D., Harrison, C., Kainz, K., Socol, A. R., et al. (2015). Implementing educational innovations at scale: Transforming researchers into continuous improvement scientists. Educ. Policy 29, 257–277. doi: 10.1177/0895904814560886

Dagenais, C., Somé, T. D., Boileau-Falardeau, M., McSween-Cadieux, E., and Ridde, V. (2015). Collaborative development and implementation of a knowledge brokering program to promote research use in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Global Health Action 8:26004. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.26004

Diamond, J. B., and Gomez, L. M. (2023). Disrupting white supremacy and anti-Black racism in educational organizations. Educ. Res. doi: 10.13189X231161054

Elmore, R. F. (2016). “Getting to scale” it seemed like a good idea at the time. J. Educ. Change 17, 529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10833-016-9290-8

Feldman, M. S., and Pentland, B. T. (2003). Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Adm. Sci. Quart. 48, 94–118. doi: 10.2307/3556620

Finnigan, K. S., Daly, A. J., and Che, J. (2013). Systemwide reform in districts under pressure: The role of social networks in defining, acquiring, using, and diffusing research evidence. J. Educ. Adm. 51, 476–497. doi: 10.1108/09578231311325668

Fishman, B. J., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A.-R., Cheng, B. H., and Sabelli, N. (2013). “Design-based implementation research: An emerging model for transforming the relationship of research and practice,” in National Society for the Study of Education: Vol 112. Design Based Implementation Research, eds B. J. Fishman and W. R. Penuel (Colorado: University of Colorado Boulder), 136–156.

Grunow, A., Park, S., and Bennett, B. (2024). Journey to Improvement: A Team Guide to Systems Change in Education, Health Care, and Social Welfare. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gutiérrez, K. D., and Penuel, W. R. (2014). Relevance to practice as a criterion for rigor. Educ. Res. 43, 19–23. doi: 10.3102/0013189X13520289