- 1Faculty of Education, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

- 2Department of Education and Psychology, Open University of Israel, Ra'anana, Israel

Purpose: The study seeks to provide insights into the specific leadership behaviors employed by school leaders to navigate the complex challenges posed by the pandemic.

Methods: A qualitative research approach was adopted, involving in-depth interviews with a diverse sample of 20 school principals. Thematic analysis was employed to identify recurring patterns in their narratives addressing leadership styles and behaviors.

Findings: The findings vividly portray school principals’ leadership behaviors during the COVID-19 crisis. This study connected these behaviors with the characteristics of transformational and transactional leadership styles. Behaviors identified as transformational leadership emerged as the most prominent during the crisis. The research found that there is an expression for each of these characteristics in practice and demonstrated this through quotes from school principals.

Discussion: Taken together, the findings show that principals viewed integrated leadership as crucial and effective during the COVID-19 crisis. This research contributes to the literature by offering a nuanced understanding of how school principals leveraged both transformational and transactional leadership behaviors during an unprecedented crisis.

Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 brought unprecedented challenges and disruptions to nearly every facet of society, including the field of education (Adams et al., 2021; Brassey and Kruyt, 2020). School leaders, particularly principals, found themselves at the forefront of these challenges, tasked with navigating a rapidly changing educational landscape characterized by uncertainty, remote learning, and heightened emotional stress (Menon, 2023; Schechter et al., 2022). In response, many principals demonstrated remarkable adaptability and resilience, exhibiting various leadership behaviors to guide their institutions through this crisis (Hafiza Hamzah et al., 2021; Masry-Herzallah and Stavissky, 2021; Menon, 2023; Stefan and Nazarov, 2020). Effective leadership became a crucial factor in the ability of schools to adapt to rapidly evolving circumstances, including the shift to remote learning and the need to support staff and students amid ongoing disruption.

Understanding how different leadership styles influenced school management during this crisis is essential for building future resilience in educational leadership. The literature suggests that the COVID crisis brought to the forefront the importance of leadership style in optimizing organizational performance (Du Plessis and Keyter, 2020; Meiryani et al., 2022). Educational studies that dealt with leadership styles during the COVID-19 crisis demonstrated that a principal’s leadership style correlates to teacher performance (Savitri and Sudarsyah, 2021), the success of online teaching (Masry-Herzallah and Stavissky, 2021), the ability of teachers to innovate (Purwanto et al., 2020), the quality of teaching (Buric et al., 2021), the degree of positivity of teachers (Purwanto et al., 2020), and teacher motivation (Rathi et al., 2021), and job satisfaction (Wulandari et al., 2021). However, these studies are mostly quantitative, and there is a great lack of qualitative studies on leadership styles during the COVID-19 crisis in an educational context.

In particular, there is a significant gap in qualitative research that explores how the Full Range Leadership Model (Bass and Avolio, 1994)—including transformational and transactional leadership—was enacted in real-world educational settings during COVID-19. Few studies detail how specific leadership behaviors corresponding to these styles were implemented (notable exceptions include Andersen et al., 2018, and Balyer, 2012). Moreover, the literature lacks in-depth exploration of integrated leadership approaches (e.g., Marks and Printy, 2003), which combine multiple styles to address complex challenges during COVID-19.

This study addresses these research gaps by qualitatively exploring the leadership behaviors that school principals perceived as effective during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it focuses on two prominent leadership styles: transformational leadership (i.e., leaders who inspire and motivate their followers to achieve exceptional outcomes) and transactional leadership (i.e., leaders who use a structured and task-oriented approach, often based on rewards and sanctions) (Bass and Avolio, 1994). It aims to uncover how transformational, transactional, and integrated leadership styles were enacted in practice and to provide a richer, more contextualized understanding of educational leadership during times of crisis. The current research set out to explore the question: What leadership behaviors did school principals perceive as effective during the COVID-19 pandemic? By analyzing the experiences and perspectives of school principals during the crisis, this study aims to contribute a deeper understanding of how leadership is practiced under conditions of crisis, offering insights for the development of future leadership strategies in educational contexts.

Theoretical background

Integrated leadership as a framework

Scholars argue that the fusion of two effective school leadership styles can produce even more significant improvements in school performance. Marks and Printy (2003) introduced integrated leadership, which combines elements of both instructional and transformational leadership to maximize school leadership effectiveness to achieve better educational outcomes. They argued that while transformational leadership creates a shared vision and inspires change, instructional leadership directly influences teaching and learning practices. Studies have supported this argument, showing that principals’ integrated leadership improves student achievement by fostering teacher-professional learning and improving instructional practices (Day et al., 2016; Urick and Bowers, 2014). Bellibaş et al. (2021) further demonstrated that transformational leadership enhances the effects of instructional leadership and advocated for an integrated leadership style during challenging times, such as school reforms. Yet, research on how transformational and transactional leadership styles are integrated to promote effective schooling is missing.

Transformational and transactional leadership styles

Transformational leadership, which refers to the leader moving the follower beyond immediate self-interests, is recognized as the most effective leadership style. Where this leadership style is used, personnel tend to be more professional, hierarchies are flatter, and teamwork is the key to success. This leadership style can be used to achieve positive school outcomes (Berkovich, 2020). This leadership style is based on Bass’ theory (Bass, 1985). Transformational leadership includes four sub-dimensions: (1) Idealized influence means that the leader should have a vision and passion that can make his/her subordinates follow his/her orders sincerely and he/she should display his/her self-confidence, an attitude of ideology, or dramatic and emotional acting to make that happen (Lan et al., 2019). (2) Inspirational motivation means the extent to which the leader displays his/her charm to convey the goal of an organization, resulting in subordinates’ optimism and hope regarding the development and future of the institution; working motivation and coherence are the end purposes (Budur and Poturak, 2021). (3) Intellectual stimulation means the extent to which the leader encourages his/her subordinates to enhance their knowledge, creativity, and deeply ponder problems (Berkovich, 2020). (4) Individualized consideration means the extent to which the leader shows respect and care for his/her subordinates (Gorgulu, 2019). When this style of leadership is used, teachers tend to feel like an important part of the team and therefore tend to work harder, display a higher level of commitment to their school, and exhibit better overall performance (Lan et al., 2019). Transformational leadership refers to a process through which a leader not only echoes members’ needs through leadership charisma but also enhances levels of morale and motivation, which in turn, contribute to continual improvement in motivation throughout the school (Berkovich and Eyal, 2021). Leadership styles for school principals are one of the most important issues that have been studied and investigated, and studies have shown that transformational leadership affects job satisfaction, teacher behaviors, student achievement, teacher trust and working characteristics, teacher job satisfaction, school culture, student achievement, and teacher burnout (Avci, 2015). The transformational school leadership style is particularly popular, considered by many to be the ideal leadership style for meeting the challenges of education in the 21st century (Hallinger, 2003).

Transactional leadership refers to motivating followers by appealing to their interests. The transactional leadership style can involve values, but those values are relevant to exchange processes such as honesty, responsibility, and reciprocity (Purwanto et al., 2020). Transactional leadership includes two main factors: (1) Meeting the followers’ expectations in return for the fulfillment of their wishes and the achievement of the determined targets. Thus, there is mutual dependence between a leader and his/her followers (Demirtas, 2020). (2) Management by exception. Positively, the leader focuses on fixing the rules and standards that are no longer on track. Negatively, the leader might leave negative comments regarding a subordinate’s failure according to the agreement made previously (Lan et al., 2019). Sadeghi and Pihie (2012) suggested that transactional leadership enables followers to pursue their interests, reduce workplace anxiety, and help employees focus on clear organizational goals, such as improving quality and customer service, reducing costs, and increasing production. Transactional leadership leads to growth and improvement through mutually stimulating relationships, by winning the support, cooperation, and obedience of subordinates through work, security, long-term employment, and favorable assessments (Berkovich and Eyal, 2021). Transactional leadership is also correlated to education and implies job satisfaction (Avci, 2015) and good teacher performance (Herminingsih and Supardi, 2017).

Transformational and transactional leadership styles are part of the Full Range Leadership Model (Bass and Avolio, 1994). Bass (1985) posits that the transactional and transformational leadership paradigms are complementary constructs rather than opposites, and they have a symbiotic interdependency relationship. Both leadership styles have the desired objectives of delivering positive achievements and outcomes for the organization. Therefore, leaders may adopt a multidimensional and paradoxical approach that may utilize both transactional and transformational leadership behaviors (Brown and Nwagbara, 2021). In educational research, Avci (2015) found a high average perception of teachers about their principals’ transformational and transactional leadership. Herminingsih and Supardi (2017) suggested that transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and work ethics have positive and significant impacts on teacher performance both simultaneously and individually. Du Plessis and Keyter (2020) indicated that combining the strengths of various leadership styles can be considered in dealing with converged crises (social, economic, and political) such as the COVID-19 crisis. Accordingly, in the present research, we seek to empirically explore how these widely disparate leadership styles are reflected in specific actions of school principals during the COVID-19 crisis.

Transformational and transactional leadership styles as crisis leadership

According to DuBrin (2013), crisis leadership is the process of guiding a group of people through a sudden, mostly unforeseen, very unpleasant, and emotionally taxing scenario. Leaders must balance opposing stakeholder demands while seizing chances for positive change during a crisis (Wu et al., 2021). The literature has identified the transformational leadership style as relevant to crises (Pillai, 2013), but recent work has indicated that the transactional leadership style might also be relevant to crises (Rathi et al., 2021). Educational studies dealing with leadership styles during the COVID-19 crisis also highlighted the importance of transformational and transactional leadership (Hafiza Hamzah et al., 2021; Masry-Herzallah and Stavissky, 2021; Savitri and Sudarsyah, 2021).

Several quantitative educational studies have demonstrated the relevance and the advantages of transformational leadership during the COVID-19 crisis: Savitri and Sudarsyah (2021) showed a positive relationship between transformational leadership and teachers’ performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Their research evidence clearly shows that transformational leadership can move followers to exceed expected performance. Masry-Herzallah and Stavissky (2021) found a positive correlation between principals’ transformational leadership and the success of online teaching, and the quality of communications in school mediated this correlation. Purwanto et al. (2020) proved that transformational leadership has a positive and significant effect on teacher innovation capability, both directly and through mediating organizational learning. Buric et al. (2021) showed that transformational school leadership was positively related to instructional quality both directly and indirectly via teacher self-efficacy. It was positively related to all three dimensions of instructional quality–classroom management, cognitive activation, and supportive climate. Purwanto et al. (2020) showed that transformational leadership has a positive and significant effect on the innovation capabilities of teachers.

Several quantitative educational studies have also demonstrated the relevance and benefits of transactional leadership during the COVID-19 crisis. Purwanto et al. (2020) found a positive correlation between transactional leadership and the innovation capabilities of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis. Purwanto et al. (2020) claims that transactional leadership has a positive and significant effect on teacher innovation capability only through mediating organizational learning, but it does not have a significant direct effect on teacher innovation capability. They show the positive and significant impact of transactional leadership on the capability to teach creatively and on the ability of teachers to innovate and to be positive. Rathi et al. (2021) proved that the transactional leadership style enhances employees’ motivation and has more influence on employee performance as compared to transformational leadership because transactional leaders motivate followers to perform at higher levels, exert greater effort, and show more work commitment.

Method

Research context

The study was conducted in Israel, where the government closed all educational facilities on 13 March 2020 as part of COVID-19 containment measures (Stein-Zamir et al., 2020). Israel is a Western-oriented society with cultural characteristics that are like those of Western Europe and the United States (Ben-Shem and Avi-Itzhak, 1991). Teachers shifted to distance teaching to minimize disruption, but this required them to suddenly adapt their work patterns under challenging conditions (Zadok Boneh et al., 2022). This shift affected 2.3 million pupils across all levels (Donitsa-Schmidt and Ramot, 2020). The educational system returned to normal by April 2021 (Haklai et al., 2022).

During the pandemic, Israeli principals led schools within a highly centralized, bureaucratic system, managing tensions between policy and practice (Ganon-Shilon and Becher, 2024). They were under pressure to maintain continuity while following Ministry of Education guidelines that emphasized class cohesion, teacher-student relationships, and social–emotional learning (Israeli Ministry of Education, 2021; OECD, 2020). However, early in the pandemic, inconsistent directives created confusion, leaving principals to handle logistical challenges, and conducting epidemiological investigations added further strain, as principals were already overwhelmed by demands from students, parents, municipalities, and the ministry (OECD, 2020; Shaked, 2024).

Participants and procedure

This qualitative study used a phenomenological research design to explore the experiences of school principals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phenomenology enables researchers to investigate the experiences of individuals and expose the meaning they attach to those experiences (Creswell and Poth, 2018). Consequently, 20 school principals from public schools were interviewed using semi-structured interviews (see Appendix). Interviews lasted an average of about 45–60 min. Each principal was questioned about how and what behaviors they used to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. The interviews were audiotaped. The sample size of 20 principals was determined based on the principle of theoretical saturation (Rahimi, 2024), which was reached when no new information emerged from the interviews.

Participants were chosen to take part in the study by a process known as purposive sampling, which involves choosing participants or data sources based on the expected richness and usefulness of the information in connection with the study’s research topics (Gentles et al., 2015). This approach was particularly suited to the study’s aim of capturing a diverse range of leadership experiences during the pandemic. In this case, purposive sampling was employed to ensure variation across several key dimensions: gender, professional seniority, school type (i.e., middle and high school), and socio-economic background of the school community. All participating principals were from public schools, reflecting the structure of the Israeli educational system, where the vast majority of schools are public (over 80%), some are semi-private, and private schools are relatively rare (Berkovich, 2018). The exclusive focus on public schools reflects the context in which most educational leadership in Israel occurs, although it is acknowledged that private and semi-private schools may present different leadership dynamics. Most of the participants worked in schools belonging to the upper-medium class background (68% of the sample). About a fifth worked in schools from a lower-middle-class background (21% of the sample), 10% worked in schools from a middle-class background, and one participant worked in a high-SES school (5%). While the sample is skewed toward upper-middle backgrounds, this distribution is representative of the broader landscape of Jewish secular and religious public schools. In contrast, schools serving the lowest socioeconomic communities in Israel are largely Jewish ultra-Orthodox or Arab public and semi-private schools, which were not the focus of this study (Berkovich, 2018; Ministry of Education, 2024). Gender diversity was also reflected in the sample, with 40% of the participants being women. The majority of the principals are located in Israel’s Tel Aviv and Center regions (50%), and the rest are from the South region and North regions (35%) and Jerusalem region (15%). Principals have been in their positions for at least 5 years (M = 12.75, SD = 5.81). Principals headed largely medium-sized schools (number of enrolled students) (M = 851, SD = 427.88). The schools included 6y (7th-12th grade) high schools (40%), middle (7th-9th grade) schools (15%), and high (10th-12th grade) schools (45%).

Data analysis

We used the directed content analysis method to analyze the qualitative data (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). In this method, insights from literature act as codes that drive the investigation. Based on the literature, we initially operated under the assumption that transformational leadership behaviors would be more prevalent in principals’ narratives. However, we remained open to the possibility of other leadership practices and styles emerging from the data. In the initial phase, we focused on identifying the specific leadership patterns exhibited by principals during the crisis. In the second step, we organized effective leadership narratives into themes of practices and styles, drawing inspiration from a review of additional educational leadership literature. Initial codes were deduced from Bass’s Full Range Leadership Model via a guided content analysis. A subset of transcripts was coded independently by three researchers during the first coding phase. To guarantee uniformity and rigor in the application of the codebook, disagreements were examined and settled by consensus.

We used researcher triangulation as all researchers were involved in analyzing data. The triangulation led to a more accurate matching of the data with theory since each researcher brought their professional experience. The first author’s familiarity with the examined issue stems from their experience as a school coordinator and teacher throughout the pandemic. The second and third authors, who are researchers in educational leadership, contribute to this study. This collaboration allowed us to identify key patterns and themes that may not have been apparent from a single viewpoint, thus enhancing the depth and reliability of our findings. We were conscious of our prejudices throughout the study and tried to present the principals’ experiences as accurately as possible. We engaged in peer debriefing to question our interpretations and reflective talks, wherein each researcher admitted any biases, to ensure neutrality. To maintain decision-making transparency, we also maintained memos. We frequently went back over the data to make sure our conclusions were based on the opinions of the participants rather than our own.

Ethics

Institutional Review Board (IRB) ethics approval was obtained for the study. The two main issues that needed to be effectively handled to protect the interviewees were consent and confidentiality (Gibton, 2015). An informed consent form that includes a summary of the material above has been signed by the participants. Before the interviews were scheduled and throughout the interviews, we emphasized to the participants that they could refuse to answer any questions, in full or in part. We also omitted identifying information from the final report to safeguard the interview subjects’ schools and surroundings as well as the interview subjects themselves. All participant identities were anonymized in the transcripts to ensure confidentiality and protect their privacy. In addition, to protect the participants’ identity, numbers have been used in place of their real names.

Results

Transformational leadership behaviors were the dominant and frequent accounts in the principals’ narratives. The number of transactional leadership behaviors reported by principals was significantly lower than transformational leadership behaviors. It should be noted that sometimes even principals describing dominant transformational behaviors also reported using transactional leadership behaviors in some cases.

Transformational leadership behaviors during the COVID crisis

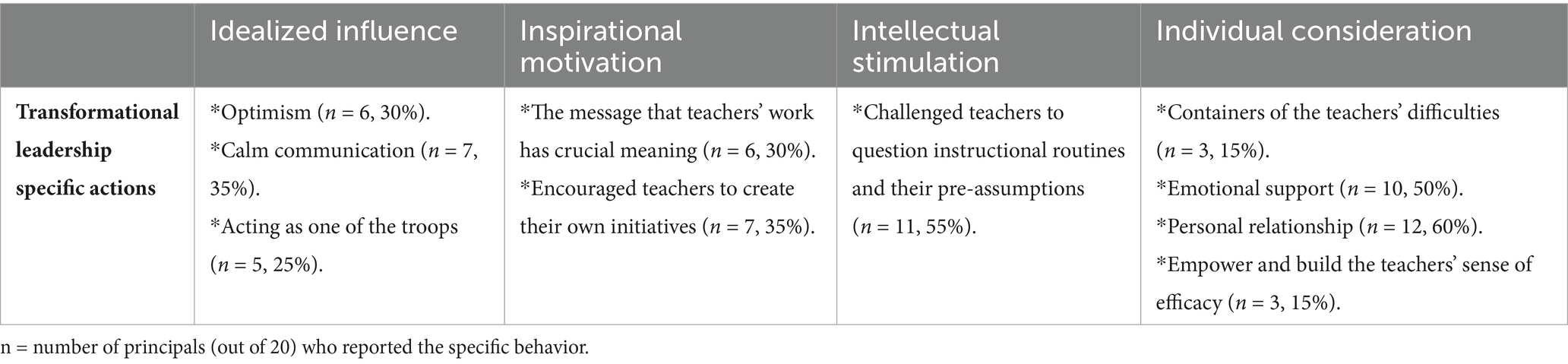

Principals adapted four transformational leadership behaviors taken in response to the crisis: idealized influence (role modeling), inspirational motivation (vision), intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration (Table 1).

Idealized influence behaviors. Many principals stated that because of the situation they tried to embody and project optimism. The explanation for this on their part is that when the leadership radiates optimism, it affects everyone, so it was important to maintain it even in the most confusing times: “In all this, and this is horrible, it is important in my opinion, all the time to be the model of resilience, of optimism, of some kind something stable that is possible turn to the principal, very much available, very much accessible” (Principal 13). Another explanation was that optimism enables one to think more positively about the future and thus influence decisions and make them better. Principals also describe being and using calm communication: “My idea was during the coronavirus–you guys, everything is at ease. Everything is fine” (Principal 4), “to be a calming voice. There is a situation–we will find solutions, and we will not panic. This is something I mostly felt. It’s not just a matter of not broadcasting hysteria, but also not being hysterical” (Principal 15). Some principals also reported acting as one of the troops, such as entering classes to teach instead of other teachers, going to the field, working late hours, coming to school despite the situation, having conversations with teachers, and in other ways, inspiring their teachers to behave in the same way. One of the principals said: “How will it look if the principal of the school is at home? [...] If I’m at home, I broadcast that school is not important.” Principals’ physical presence at the school was perceived as an administrative statement both to the teaching staff and the students – “I am here despite the crisis” (Principal 20). These types of actions by principals demonstrated a strong and mobilizing presence and leadership.

Inspirational motivation behaviors. One key part of the reframed school vision during COVID that principals articulated was the message that teachers’ work has crucial meaning: “[Teachers] continued and functioned because they felt they were important, they felt how valuable they were to the system, they felt that thanks to them we are keeping the children sane and normal” (Principal 13). Many principals also encouraged teachers to create their own initiatives that connect to a shared vision and give teachers a sense of mission, commitment, and energy: “Every teacher leads his own dream, and that’s how he feels part of the game […] even if only 10 out of 100 initiatives take root, it’s worth it” (Principal 4).

Intellectual stimulation behaviors. Participating principals challenged teachers to question instructional routines and their pre-assumptions and to think out of the box. “I ask them - when does the Bible inspector come to check if you are doing what is necessary? You were told to teach Chapter X - Do not study and do not test me. Connect to the places you want to bring the students” (Principal 9). For the most part, these principals watered down the school’s regulations in the crisis and allowed teachers to make decisions on their own in the field in front of their students.” (Principal 4).

Individual consideration behaviors. Numerous principals acted as containers of the teachers’ difficulties and tried to contain the stress, fear, frustration, burnout, and disintegration that affected the team: "I think that today there is much more understanding and inclusion than before. The coronavirus has given me a reservoir of inclusion and understanding” (Principal 7). Principals also emphasized the emotional support required by the staff and the students. The principals tried to identify each person’s personal needs, such as how their families were doing, as well as providing the necessary support such as being a listening ear, arranging meetings with psychologists and counselors, and more.” In front of the team, the concept did not change, but the execution did. Much more strengthens the emotional side. It stayed with me from the Corona. I know that this is my job, and I do it more” (Principal 12). To make containment and emotional support as fully available as possible, some principals emphasized their personal relationships with staff members and encouraged teachers to establish personal relationships with their students. These relationships are reflected in taking care of personal needs, making frequent contact with the teachers, being available to the staff members, and making gestures to the teachers: “My whole interpersonal side was very much sharpened during this period from the desire to calm [teachers and students] fears” (Principal 2). Many principals also tried to empower and build the teachers’ sense of efficacy: “The main part of my work was unequivocally to cultivate among the teachers a sense of efficacy and a constant detection of their needs and to constantly respond to their very good places” (Principal 9).

Transactional leadership behaviors during the COVID crisis

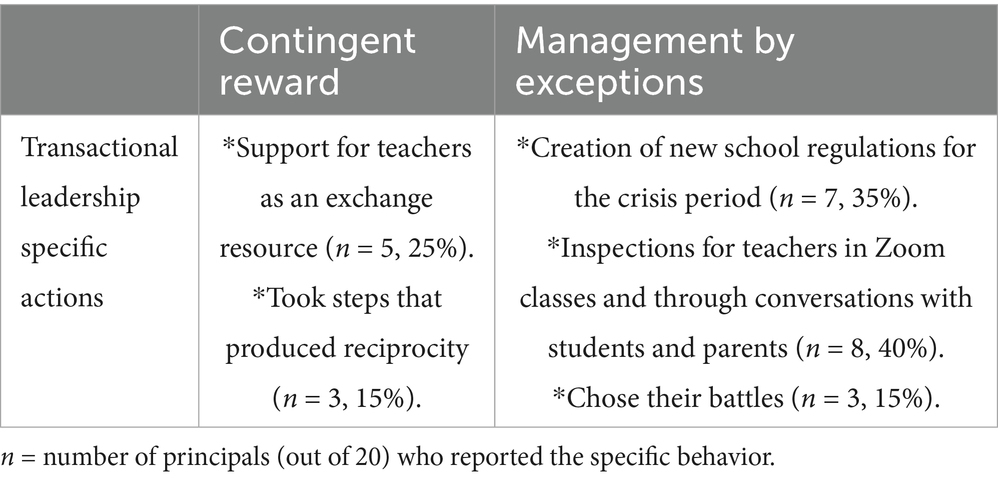

To deal with the COVID crisis, principals adopted two transactional leadership behaviors: contingent reward and management by exceptions (Table 2).

Contingent reward behaviors. Some principals used support for teachers as an exchange resource. In their view, for the school to continue to function smoothly at any cost even during the crisis, and for learning to continue to take place: “You have to respond not only to your students but also to the children of your teachers if you want them to continue to function in this delusional period” (Principal 13). Principals also assumed that if they considered their teachers’ personal needs and made themselves available, it would pay off; that is, teachers would feel committed to repaying the principal’s gesture, and thus the school would function better during the crisis. “Thanks to the fact that I was available to them all the time, teachers did not say no to me … the same treatment s/he received, s/he gave back … teachers were ‘owed to us’ and continued to function” (Principal 13). In practice, this sense of responsibility and commitment was echoed by teachers themselves, who felt valued and essential: “They felt how important they were to the system […] they knew they had to keep functioning, despite the difficulties at home” (Principal 13). These principals took steps that produced reciprocity. A good example is that of a principal who decided to recruit the school’s administrative staff, who, most of the time, were free from tasks due to the students’ absence and turned them into “babysitters” for the teachers’ children. The teachers brought their children to school, the administration staff looked after them and helped them with distance learning, and thus the teacher was free to teach. A kind of “alliance” was created here - the school helps you so that you can fulfill your role: “We found a lot of creative solutions - we brought teaching aids/ administrative staff to watch over teachers’ children, thus allowing them to teach quietly from home” (Principal 14). In some cases, principals even encouraged mutual assistance among teachers, creating informal support networks during the crisis: “We discovered people who help others […] real mutual assistance” (Principal 14).

Management by expectations behaviors. Some of these school principals initiated the creation of new school regulations for the crisis period, with an emphasis on distance learning. The regulations are designed to maintain the boundaries of “do” and “do not” for students and teachers: “To the teachers, you must place demands and boundaries; if they do not feel that you worry about them, you cannot succeed in motivating them. Combination of order and discipline together with love, the bride, etc.–this is the winning combination” (Principal 6). This viewpoint is a usual equating of setting expectations with emotional aspects. “I was involved in writing regulations for distance teaching for staff and students. I was asked a lot of ethical questions, such as opening and closing cameras” (Principal 3). These regulations also helped reduce confusion in the rapid shift to digital: “There was a lot of focus on remote teaching policies […] we had to write guidelines for staff and students” (Principal 3).

Several principals conducted inspections for teachers in Zoom classes and through conversations with students and parents, to understand whether these teachers were doing their required work and not avoiding their work. These principals were waiting to hear the students’ “whistleblowing” about teachers cancelling classes: “This is how I tested the teachers if they are working according to the scheduled lessons system. When there was no lesson, the students “spilled the beans.” I turned to the teachers who did not come in, at first out of genuine concern, and I asked. Some told me all kinds of stories” (Principal 13). Some principals implemented systematic feedback mechanisms to monitor staff activity and promote accountability. They gathered input not only from students but also from parents and teachers, utilizing this multi-source feedback to identify challenges and foster trust in leadership. One principal clarified that these tools were not designed to control or penalize teachers, but rather to enhance organizational transparency and support professional growth: “I explained to the staff the importance of what I was doing—that it wasn’t about blaming anyone […] Teachers needed to understand that this tool is intended for constructive, not punitive, criticism. It helps improve their work and enables meaningful comparisons.” (Principal 6).

Few principals chose their battles and were reluctant to enter “wars” with staff members in order not to create shocks: “The cost of [fighting with a teacher] is much higher than what we can accept. I prefer to invest in them” (Principal 9). The drive of transactional leaders was not to move forward, but also not to go backwards, that is, to maintain the status quo and stability.

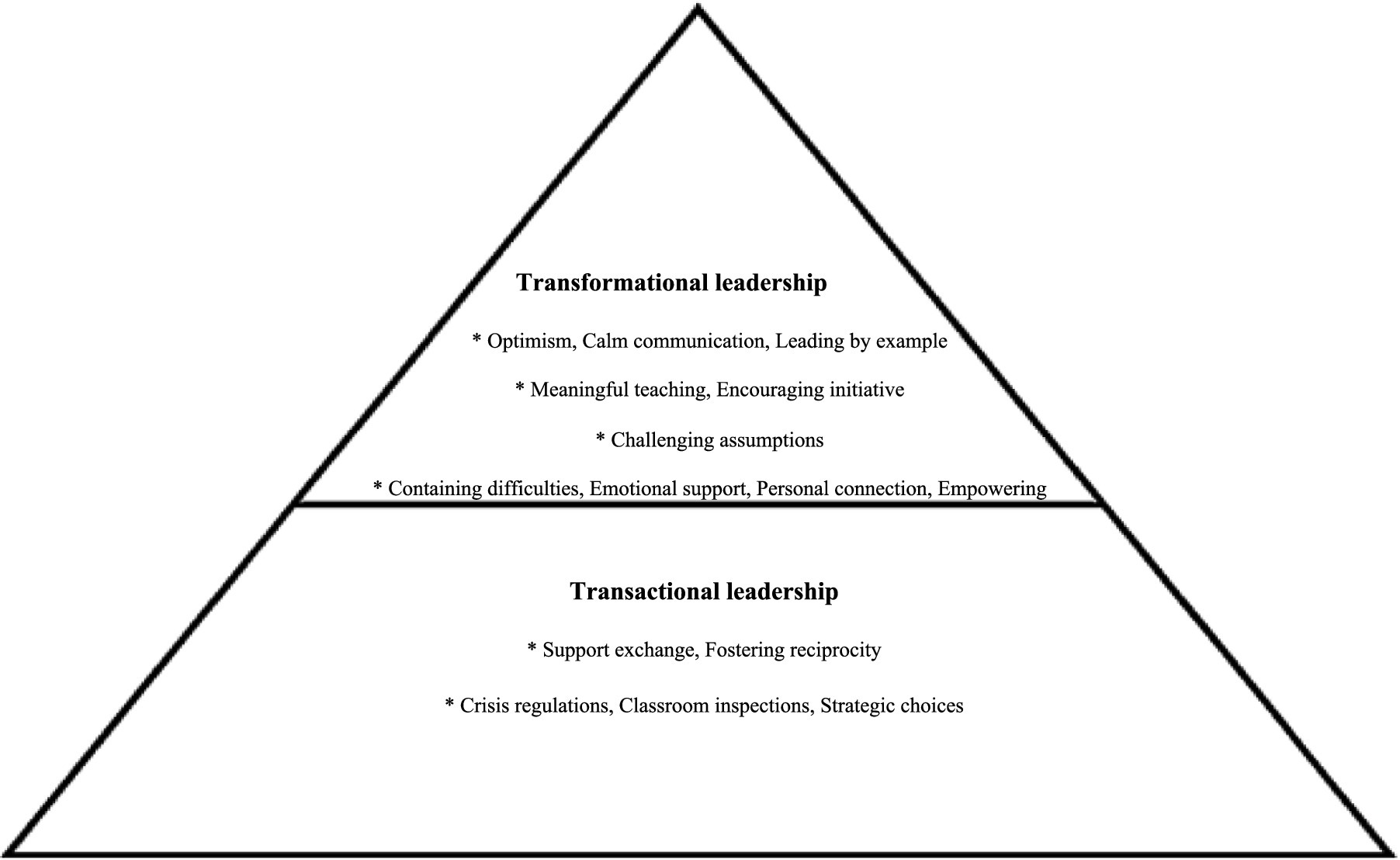

Toward a new integrated crisis leadership model

Considering the findings above, we suggest that the integrated leadership approach, which merges these leadership practices and styles, emerged as crucial for balancing emotional and academic needs during the societal and organizational crisis. Integrated leadership proved crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering the flexibility and adaptability needed to meet the school community’s immediate and long-term needs. Transformational leadership provides the emotional and motivational foundation necessary to inspire and mobilize staff in times of challenge. For example, one principal arranged for administrative staff to supervise teachers’ children during school hours and permitted flexible teaching schedules, such as evening lessons—clear transactional measures aimed at ensuring continuity and effective task management. Simultaneously, he refrained from blaming teachers who faced difficulties with distance learning platforms, prioritized personal support, and fostered a sense of belonging among staff, stating that “a protected team knows how to appreciate and go beyond” (Principal 14). This example demonstrates how practical problem-solving was seamlessly interwoven with emotional empowerment, reflecting the integrated nature of leadership in times of crisis. Transactional leadership supported this process by ensuring the availability of resources and fostering reciprocal motivation. In this framework, integrated leadership can be envisioned as a pyramid, capturing the complementary relationship between different leadership approaches that together respond to the complex needs of school communities, with transformational leadership practices at the top, and supported by foundational transactional practices at the base.

The proposed pyramid model (Please see Figure 1) can reflect a hierarchy of leadership responses aligned with both emotional and academic needs. At the base, transactional leadership provides the operational foundation: maintaining structures, securing resources, and ensuring stability. These practices are essential for continuity and for creating the conditions in which other forms of leadership can function. At the top of the pyramid, transformational leadership enables school principals to articulate a shared vision, foster trust, and mobilize staff around collective goals, which are important capacities during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Integrated leadership, as conceptualized in this model, reflects a layered and responsive approach with transactional leadership ensuring the “how,” and transformational leadership the “why,” allowing school principals to balance immediate challenges. Thus, transactional leadership secures the groundwork necessary for day-to-day work, while transformational leadership mobilizes the community toward long-term recovery and growth development during a crisis.

Several cases from the present sample data illustrate how principals enacted this integration of leadership styles in real time, revealing the practical duality at the heart of the proposed model. For example, one principal described holding regular one-on-one meetings with teaching coordinators to monitor outcomes—a transactional behavior centered on accountability and performance. However, the principal clarified that the underlying motivation was relational and transformational: “I could have checked it alone, but this was my way to show interest” (Principal 13). Here, a monitoring mechanism served not only managerial ends but also a vehicle for emotional connection, reinforcing the dual nature of leadership during crisis. Another principal reported balancing clear expectations for discipline and commitment with efforts to reduce stress and offer emotional support: “You can pressure them or come toward them […] if they do not feel that you care, they will not function” (Principal 6). This example highlights an intentional blend of leadership styles: demanding performance (transactional) while simultaneously cultivating emotional safety (transformational).

Discussion

This study aims to explore how school principals perceived effective leadership during the COVID-19 crisis. This study addresses a gap in the literature due to the limited number of qualitative investigations into leadership styles both in general (e.g., Andersen et al., 2018; Balyer, 2012 referring to transformational and transactional styles) and in times of crisis. We initiated this study with the assumption that one specific leadership style would emerge as predominant. However, our findings reveal that principals recognize a spectrum of transformational and transactional leadership practices as critical for maximizing effectiveness in meeting the social and organizational challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. This highlights the importance of the integrated nature of leadership in crisis as a working model for turbulent times in which diverse approaches are valued for their roles in navigating complex and evolving demands in educational settings. This aligns with the integrated leadership model discussed by Bellibaş et al. (2021) for school reform periods but extending it to situations of unplanned and undesired external change.

In addition, although the proposed integrated leadership model shares some similarities with Marks and Printy’s (2003) framework, it diverges in context and application. In their research, Marks and Printy (2003) highlighted the integration of instructional and transformational leadership for pedagogical improvement during stable reform periods. In contrast, our model emerged during the COVID-19 crisis, a time marked by urgency, uncertainty, and emotional strain. Our approach frames integrative leadership as a layered, adaptive process, where transactional practices ensure immediate functionality and transformational leadership mobilizes staff around shared goals. Another difference refers to Marks and Printy (2003) emphasizing academic excellence and instructional coherence. However, our findings suggest that in times of crisis, the focus shifts away from academic excellence per se. Instead, academic activities are often perceived as a means for restoring routine and building resilience, not necessarily to promote educational achievement. Thus, emotional well-being and psychological support emerge as central leadership concerns during such times. As Brown and Jones (2025) argue, crisis leadership demands adaptive communication and responsiveness, characteristics less emphasized in traditional models. Recently, research showed the importance of emotional support and decentralized coordination and highlighted the psychological toll on educators (Conte et al., 2024; Hadad et al., 2024). Additional research also reported that some principals addressed basic needs such as meals and internet access (Grooms and Childs, 2021) while navigating rapid digital transitions (Parmigiani et al., 2021; Sy et al., 2022). Thus, integrated leadership during crisis reflects a context-sensitive blend of leadership approaches that enables principals to manage uncertainty, sustain well-being, and support continuity, emphasizing the need to reconceptualize integration for turbulent times (Harris and Jones, 2021; Leithwood and Azah, 2017) and to account for the relational and situational demands unique to crisis contexts.

Our study provides seven insights that may contribute to understanding crisis leadership in the school context. First, several studies have so far discussed leadership styles in a crisis (Buric et al., 2021; Masry-Herzallah and Stavissky, 2021; Purwanto et al., 2020; Rathi et al., 2021; Savitri and Sudarsyah, 2021), but each of them focused on a limited number of leadership behaviors or aspects due to the limitations of the quantitative method. Very few qualitative works focused on transformational leadership focused on description confirming its dimensions (Balyer, 2012) or on the associated outcomes of a specific dimension (Andersen et al., 2018). Thus, the potential of qualitative insights to enrich and expand the portrayal of the practices related to dimensions of leadership styles remains untapped. Moreover, these works focused on routine times (Andersen et al., 2018; Balyer, 2012) and not crisis periods. Our study offers a wide spectrum of leadership behaviors identified with two prominent leadership styles and may contribute to a more diverse and broader understanding of leadership styles in times of crisis.

Second, our study illuminates how principals displayed idealized influence by using specific practices of instilling optimism, practicing calm communication, and positioning themselves as part of the teaching team during a crisis. Classic definitions of idealized influence stress “influence over ideology, influence over ideals, and influence over ‘bigger than life’ issues” (Bass, 1999, p. 19), but in our study, we saw the mundane side of it. Other works have claimed that the mundane focus of leaders on “trivial aspects” is important in ordinary times since it carries an emotional value (Sveningsson and Alvesson, 2003). Yet, research showed that crisis undermines a sense of stability and infuses the daily routine with great uncertainty (Rast and Hogg, 2016). When the path ahead is uncertain, people turn to leaders to help them gain clarity and a grounded hope for a better future, seek community and safety, and want someone with a positive vision who is courageous and confident about tackling the problems we all face (Brassey and Kruyt, 2020). Previous studies have already discussed the importance of these leadership behaviors during a crisis; for instance, Adams et al. (2021) suggested that principals understand that they must build positive relationships between teachers and students during crises. Similarly, Monehin and Diers-Lawson (2022) indicated that optimism is a critical trait in successful crisis leadership and that it is connected to positive outcomes for teams and organizations. Thus, in a sense, transformational leadership role modeling in times of crisis is about modeling emotional stability in mundane aspects. Our research findings illustrated how principals became a stabilizing and positive force for teachers who felt insecure and equipped them with positive emotions, which could explain why they advocated these behaviors.

Third, inspirational motivation was evident as principals emphasized the significant meaning of teachers’ work and encouraged them to take the initiative. These findings are in line with the study of Tao et al. (2022), suggesting that leaders’ motivational language (i.e., direction-giving, emphasis, and meaning-making) can satisfy the needs of employees and promote their ability to cope proactively with a crisis. Classic writing on inspirational motivation argues that a leader should focus on communicating an energizing vision to followers (Bass and Riggio, 2006), but during a crisis, appealing to futuristic visions might be seen as detached from the reality of scarce resources and the heavy workload that accompany the crisis (Menon, 2023). Since innovative realism is part of an effective vision (Larwood et al., 1995), it can explain why school leaders choose to stress work meaning and create motivation by highlighting the students’ needs. Principals helped teachers understand that students may “get lost” when they do not have a learning framework, emphasized the role of the teacher in creating this framework for the lost students, and encouraged teachers to take the initiative. As work meaning is known to be a key factor in conveying leaders’ positive influence on employees’ psychological well-being (Arnold et al., 2007), its significance appears to be particularly pronounced in times of crisis. Additionally, providing clear direction is considered more effective during stressful periods (Tao et al., 2022). Therefore, leaders’ efforts to convey a sense of direction may serve as another important strategy for supporting employees’ wellbeing.

Fourth, intellectual stimulation was observed in our findings as principals challenged teachers to question their instructional routines and pre-assumptions. These findings are consistent with the findings of Adams et al. (2021), which indicated that principals rallied their teachers to find new ways to teach and motivated them to improve their instructional content during the pandemic. The classical definition of intellectual stimulation is stimulating followers’ efforts to be innovative and creative by finding new ideas and creative solutions (Bass and Riggio, 2006). However, during a crisis, problems happen faster, and solutions are born out of the necessity to maintain basic functions rather than through planning. This makes learning focused less on the exploration of new conditions and more on the exploitation of new conditions (Kim et al., 2012). Prior research suggested that teachers tend to be resistant to change (Berkovich, 2021), whether the change is due to reform resulting from policy or due to necessity such as arises during a crisis. Moreover, the existing research suggests that teachers in normal times learn mostly through experimentation and reflection on their teaching practices (Bakkenes et al., 2010). This is a long and gradual process. Therefore, it seems from our findings that a school leader in a time of crisis needs to make a special effort to motivate teachers to accept change. In times of crisis, maintaining traditional methods can jeopardize the system, as incremental change becomes insufficient. Consequently, many principals urged teachers to critically evaluate existing practices and embrace innovation, particularly in the realms of technology and education. This aligns with Kurt Lewin’s concept of “unfreezing,” wherein resistance to change is reduced, while simultaneously fostering a learning environment centered on the exploitation of existing knowledge and resources.

Fifth, principals demonstrated individual consideration by addressing teachers’ unique difficulties, offering emotional support, building personal relationships, and empowering them to enhance their efficacy. The classic definition of individualized consideration is special attention given by the leader to each follower’s needs for achievement and growth by acting as a coach or mentor (Bass and Riggio, 2006). Arnold et al. (2016), who analyzed military leaders’ perceptions of what types of leadership behavior have been effective in extreme contexts, suggest that transformational leadership, epitomized by individual consideration, is a foundation upon which effective functioning in extreme combat situations can rest. Although the COVID-19 crisis is not the same in its characteristics, an extreme combat situation is similarly an experience of emotional turmoil for followers. Thus, leaders’ individual consideration is crucial to assist in overcoming this hardship. This is in line with claims that educational leaders’ individualized consideration promoted organizational commitment during the pandemic (Ingsih et al., 2021). Few leadership studies have delved into the practices of individual consideration (e.g., Timmerman, 2008), but these prior works did not expose as wide a range as the present study.

Sixth, our research showed how transactional leadership enhances teachers’ loyalty toward school principals during a crisis. A defining characteristic of transactional leadership is the ability to leverage available resources to create mutually beneficial transactions (Avci, 2015; Jensen et al., 2019). However, during a crisis, resources for compensation are often limited, requiring leaders to adapt by seeking new sources of support in alternative contexts. Servant leadership emphasizes the importance of supporting the performance of Personal Care Aide (PCA) employees, enabling their best efforts, and maintaining a vision that brings all efforts together for a common purpose (Canavesi and Minelli, 2022). Our research showed that in a complex period of crisis, transactional principals used PCA as an “alternative resource.” In the current study, PCA consisted of principals supporting their teachers in various ways, such as caring for their personal needs. This can be considered a part of an “exchange” between the principal and the teachers. Thus, our findings qualify the indication of James et al. (2021) that it is more beneficial to offer resources that contain universal and concrete resources (e.g., goods, services) than resources that are particularistic and symbolic (e.g., love, status) in the context of the crisis. Studies on organizational support based on psychological support resources in the context of COVID-19 have already been written (e.g., Lee, 2021), but PCA’s identification with transactional leadership has not yet been studied.

Seventh, our research showed how transactional leadership enables principals’ continued control over what is happening at the school even remotely. In the classic active perspective of management by exception, the leader monitors deviations from standards, mistakes, and errors in the follower’s assignments and takes corrective action as necessary. This approach tends to be less effective but is required in certain situations (Bass and Avolio, 1994). We suggest that crises are among these specific situations since unexpected situations are common during crises, particularly in a virtual space where teachers are “hidden” from their principals’ eyes. During a crisis such as COVID-19 and the move to remote education, it was necessary to change school regulations. Also, there was an enhanced need to monitor teachers’ instructional practices (Berkovich, 2024; Benoliel and Schechter, 2023) and students’ discipline (Welsh, 2022). It seems from our findings that transactional leadership practices were part of crisis coping, but not a dominant or single style among principals.

The results must be interpreted in light of the institutional and cultural context of the study. For instance, the lower dominance of transactional leadership might be linked to Israel’s highly centralized educational system, where principals’ ability to make decisions and redistribute resources and rewards is greatly limited and subject to stringent state directives (Nir, 2021). Furthermore, as the participants were drawn from the Israeli Jewish population, they come from a liberal Western context characterized by relatively high individualism (more than China) and higher uncertainty avoidance (a preference for having rules, even if not always following them) compared to the United States (see www.theculturefactor.com by Geert Hofstede). Thus, these institutional conditions and cultural inclinations might have influenced the specific preferences for leadership behaviors such as inspirational motivation and management by exception. In addition, the socioeconomic context may have influenced the leadership practices principals chose to enact. Higher-SES students could have had easier access to digital infrastructure and digital skills as well as more teaching and administrative support for the staff, allowing for more focus on leadership and less on management.

Limitations and future studies

This study has several limitations. First, since data in qualitative research is time-bound and context-bound (Lincoln and Guba, 1985), principals’ experiences may have changed due to post-pandemic policy and practice aimed at making schools more crisis-ready and agile, as well as due to the ongoing digitalization and AI revolution. To evaluate the generalizability of the findings, future research may examine leadership dynamics during crises across different nations, educational settings, and types of crises. Second, our sample does not include principals from private or semi-private schools, whose leadership styles may differ due to varying institutional constraints and resources, although it does reflect the main structure of the Israeli public education system. Third, this study could not fully account for how differences in socioeconomic environments may influence leadership responses. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of school leadership during times of crisis, these characteristics warrant further investigation in future studies. Fourth, all participating principals were from post-primary schools. As a result, the findings may not be fully transferable to the primary education context. Caution is therefore advised when interpreting these results, and future research should aim to include a broader range of educational levels. Fifth, the present study addresses principals’ perceptions regarding their leadership in retrospect, thus, one cannot rule out the possibility of memory bias or self-enhancement bias. Future studies can explore teachers’ perspectives or conduct observations. The challenge during intense crises is that access to organizations and participants is often highly limited, which restricts many crisis leadership studies to small-scale case studies. Sixth, it’s possible that self-enhancement bias led principals to emphasize effective leadership practices, as this is common with self-reported data. To gain a fuller understanding of crisis leadership, future research might benefit from incorporating observational data or teachers’ perspectives.

Practical implications

First, the present study provides practical and successful examples, from the point of view of the study’s participants, of each of the leadership styles during the COVID-19 crisis. These examples may inspire school principals’ relevant leadership practices during a crisis. Second, the study highlights the advantages of integrated leadership and provides evidence that can justify the use of this leadership style. The current study does not underestimate the importance of each leadership style during a crisis separately, but it claims that it should not come alone. Third, this research can have implications for policies involving the design and implementation of leadership skills and practices during a crisis.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to PB, cGFzY2FsZS5iZW5vbGllbEBiaXUuYWMuaWw=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) ethics of Bar Ilan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PB: Writing – review & editing. IB: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, D., Cheah, K. S. L., Thien, L. M., and Md Yusoff, N. N. (2021). Leading schools through the COVID-19 crisis in a south-east Asian country. Manag. Educ. :089202062110377. doi: 10.1177/08920206211037738

Avci, A. (2015). Investigation of transformational and transactional leadership styles of school principals, and evaluation of them in terms of educational administration. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 2758–2767. doi: 10.5897/ERR2015.2427

Andersen, L. B., Bjørnholt, B., Bro, L. L., and Holm-Petersen, C. (2018). Leadership and motivation: a qualitative study of transformational leadership and public service motivation. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 84, 675–691. doi: 10.1177/0020852316654747

Arnold, K. A., Loughlin, C., and Walsh, M. M. (2016). Transformational leadership in an extreme context: examining gender, individual consideration and self-sacrifice. Leadersh. Organ. Develop. J. 37, 774–788. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-10-2014-0202

Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., and McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: the mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 12, 193–203. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.193

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., and Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learn. Instr. 20, 533–548. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.09.001

Balyer, A. (2012). Transformational leadership behaviors of school prwincipals: a qualitative research based on teachers’ perceptions. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 4, 581–591.

Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 8, 9–32. doi: 10.1080/135943299398410

Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Berkovich, I. (2020). No we won’t! Teachers’ resistance to educational reform. Journal of Educational Administration, 49, 563–578.

Berkovich, I (2018). Educational policy, processes and trends in the 21st century. Raanana: The Open University of Israel. [Hebrew].

Berkovich, I. (2024). OCB saints and OCB sinners in schools: effects of principals’ leadership styles on teachers’ motivation by OCB levels. ECNU Review of Education. doi: 10.1177/2096531124125635

Berkovich, I., and Eyal, O. (2021). Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and moral reasoning. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 20, 131–148. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2020.1728703

Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S., Liu, Y., and Hallinger, P. (2021). The moderation role of transformational leadership in the effect of instructional leadership on teacher professional learning and instructional practice: an integrated leadership perspective. Educ. Adm. Q. 57, 776–814. doi: 10.1177/0013161X211035079

Ben-Shem, I., and Avi-Itzhak, T. E. (1991). On work values and career choice in freshmen students: the case of helping vs. other professions. J. Vocat. Behav. 39, 369–379. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(91)90045-N

Benoliel, P., and Schechter, C. (2023). Smart Collaborative ecosystem: Leading complex school systems. Journal of Educational Administration, 61.

Brassey, J., and Kruyt, M. (2020). How to demonstrate calm and optimism in a crisis. New York: McKinsey and Company, 11:112–131.

Brown, B., and Jones, C. (2025). Adaptive leadership of schools in Australia during the Covid-19 pandemic: lessons for future crises. School Leadersh. Manag. 45, 153–173. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2025.2473890

Brown, C., and Nwagbara, U. (2021). Leading change with the heart: Exploring the relationship between emotional intelligence and transformational leadership in the era of COVID-19 pandemic challenges. Econ. Insights-Trends Challenges 73, 9–21.

Budur, T., and Poturak, M. (2021). Transformational leadership and its impact on customer satisfaction. Measuring mediating effects of organisational citizenship behaviours. Middle East J. Manag. 8:67. doi: 10.1504/MEJM.2021.111997

Buric, I., Parmač Kovačić, M., and Huić, A. (2021). Transformational leadership and instructional quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: a moderated mediation analysis. Društv. Istraž. 30, 181–202. doi: 10.5559/di.30.2.01

Canavesi, A., and Minelli, E. (2022). Servant leadership: A systematic literature review and network analysis. Employee Responsib. Rights J. 34, 267–289. doi: 10.1007/s10672-022-09412-0

Conte, E., Cavioni, V., and Ornaghi, V. (2024). Exploring stress factors and coping strategies in Italian teachers after COVID-19: evidence from qualitative data. Educ. Sci. 14, 152–173. doi: 10.3390/educsci14020152

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. California: Sage.

Day, C., Gu, Q., and Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: how successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educ. Adm. Q. 52, 221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15616863

Donitsa-Schmidt, S., and Ramot, R. (2020). Opportunities and challenges: teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Teach. 46, 586–595. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1799708

Du Plessis, D., and Keyter, C. (2020). Suitable leadership styles for the Covid-19 converged crisis. Afr. J. Public Sect. Dev. Governance 3, 61–73. doi: 10.55390/ajpsdg.2020.3.1.3

DuBrin, A. J. (Ed.) (2013). Handbook of research on crisis leadership in organizations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ganon-Shilon, S., and Becher, A. (2024). Principals’ sense-making and sense-giving of their professional role tensions: school leaders’ professionalism and creative mediation strategies during COVID-19 crisis. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. doi: 10.1177/17411432241264693

Gentles, S., Charles, C., Ploeg, J., and McKibbon, K. A. (2015). Sampling in qualitative research: insights from an overview of the methods literature. Qual. Rep., 20, 1772–1789. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2373

Gibton, D. (2015). Researching education policy, public policy, and policymakers. London: Routledge.

Gorgulu, R. (2019). Transformational leadership inspired extra effort: the mediating role of individual consideration of the coach-athlete relationship in college basketball players. Univer. J. Educ. Res. 7, 157–163. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2019.070120

Grooms, A., and Childs, J. (2021). We need to do better by kids: changing routines in U.S. schools in response to COVID-19 school closures. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 26, 135–156. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2021.1906251

Hadad, S., Shamir-Inbal, T., and Blau, I. (2024). Pedagogical strategies employed in the emergency remote learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: the tale of teachers and school ICT coordinators. Learn. Environ. Res. 27, 513–536. doi: 10.1007/s10984-023-09487-5

Hafiza Hamzah, N., Khalid, M., Nasir, M., and Abdul Wahab, J. (2021). The effects of principals’ digital leadership on teachers’ digital teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic in Malaysia. J. Educ. E-Learn. Res. 8, 216–221. doi: 10.20448/journal.509.2021.82.216.221

Haklai, Z., Goldberger, N. F., and Gordon, E.-S. (2022). Mortality during the first four waves of COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: march 2020–October 2021. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 11:24. doi: 10.1186/s13584-022-00533-w

Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Camb. J. Educ. 33, 329–352. doi: 10.1080/0305764032000122005

Harris, A., and Jones, M. (2021). Leading in disruptive times: a spotlight on assessment. School Leadersh. Manag. 41, 171–174. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2021.1887643

Herminingsih, A., and Supardi, W. (2017). The effects of work ethics, transformational and transactional leadership on work performance of teachers. Manag. Stud. 5:250–261. doi: 10.17265/2328-2185/2017.03.009

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Ingsih, K., Suhana, S., and Ali, S. (2021). Transformational leadership style and organizational commitment in pandemic Covid-19. Contad. Adm. 66:300. doi: 10.22201/fca.24488410e.2021.3285

Israeli Ministry of Education (2021) Connecting to education: the national program towards the beginning of the 2021 school year during COVID-19. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3G2qWt6 (accessed August 31, 2021).

James, T. L., Shen, W., Townsend, D. M., Junkunc, M., and Wallace, L. (2021). Love cannot buy you money: resource exchange on reward-based crowdfunding platforms. Inf. Syst. J. 31, 579–609. doi: 10.1111/isj.12321

Jensen, U. T., Andersen, L. B., Bro, L. L., Bøllingtoft, A., Eriksen, T. L. M., Holten, A.-L., et al. (2019). Conceptualizing and measuring transformational and transactional leadership. Admin. Soc. 51, 3–33. doi: 10.1177/0095399716667157

Kim, C., Song, J., and Nerkar, A. (2012). Learning and innovation: exploitation and exploration trade-offs. J. Bus. Res. 65, 1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.006

Lan, T. S., Chang, I. H., Ma, T. C., Zhang, L. P., and Chuang, K. C. (2019). Influences of transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and patriarchal leadership on job satisfaction of cram school faculty members. Sustain. For. 11:3465. doi: 10.3390/su11123465

Larwood, L., Falbe, C. M., Kriger, M. P., and Miesing, P. (1995). Structure and meaning of organizational vision. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 740–769. doi: 10.2307/256744

Lee, H. (2021). Changes in workplace practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: the roles of emotion, psychological safety and organisation support. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 8, 97–128. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-06-2020-0104

Leithwood, K., and Azah, V. N. (2017). Characteristics of high-performing school districts. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 16, 27–53. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2016.1197282

Marks, H. M., and Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: an integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 39, 370–397. doi: 10.1177/0013161X03253412

Masry-Herzallah, A., and Stavissky, Y. (2021). Investigation of the relationship between transformational leadership style and teachers' successful online teaching during COVID-19. Int. J. Instr. 14, 891–912. doi: 10.29333/iji.2021.14451a

Meiryani, N., Koh, Y., Soepriyanto, G., Aljuaid, M., and Hasan, F. (2022). The effect of transformational leadership and remote working on employee performance during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 13:919631. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.919631

Menon, M. E. (2023). Transformational school leadership and the COVID-19 pandemic: perceptions of teachers in Cyprus. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 53:174114322311665. doi: 10.1177/17411432231166515

Ministry of Education (2024) Key findings of the education budget review system – 2022-2023. Ministry of Education. Available online at: https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/MinhalCalcala/shkifut2023.pdf (accessed May 31, 2024).

Monehin, D., and Diers-Lawson, A. (2022). Pragmatic optimism, crisis leadership, and contingency theory: a view from the C-suite. Public Relat. Rev. 48:102224. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102224

Nir, A. E. (2021). Educational centralization as a catalyst for coordination: myth or practice? J. Educ. Adm. 59, 116–131. doi: 10.1108/JEA-01-2020-0016

OECD (2020). TALIS 2018 results (volume II): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals. Paris: OECD.

Parmigiani, D., Benigno, V., Giusto, M., Silvaggio, C., and Sperandio, S. (2021). E-inclusion: online special education in Italy during the Covid-19 pandemic. Technol. Pedagogy Educ. 30, 111–124. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2020.1856714

Pillai, R. (2013), “Transformational leadership for crisis management”, in A.J. DuBrin (Ed.), Handbook of research on crisis leadership in organizations, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing

Purwanto, A., Wijayanti, L. M., Hyun, C. C., and Asbari, M. (2020). The effect of transformational, transactional, authentic and authoritarian leadership style toward lecture performance of private university in Tangerang. Dinasti Int. J. Digital Business Manag. 1, 29–42. doi: 10.31933/dijdbm.v1i1.88

Rahimi, S. (2024). Saturation in qualitative research: an evolutionary concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 6:100174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2024.100174

Rast, D., and Hogg, M. (2016). Leadership in the face of crisis and uncertainty. In: J. Storey, J. Hartley, J. L. Denis, P. Hart, and D. Ulrich (eds) The Routledge Companion to Leadership. London: Routledge, 74–86.

Rathi, N., Soomro, K. A., and Rehman, F. U. (2021). Transformational or transactional: leadership style preferences during Covid-19 outbreak. J. Entrepreneur. Manage. Innov. 3, 451–473. doi: 10.52633/jemi.v3i2.87

Sadeghi, A., and Pihie, Z. A. L. (2012). Transformational leadership and its predictive effects on leadership effectiveness. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 3, 186–197.

Savitri, E., and Sudarsyah, A.. (2021). Transformational leadership for improving teacher’s performance during the Covid-19 pandemic:, presented at the 4th International Conference on Research of Educational Administration and Management (ICREAM 2020), Bandung, Indonesia

Schechter, C., Da’as, R., and Qadach, M. (2022). Crisis leadership: leading schools in a global pandemic. Manag. Educ. 38:089202062210840. doi: 10.1177/08920206221084050

Shaked, H. (2024). Instructional leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: the case of Israel. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 52, 576–592. doi: 10.1177/17411432221102521

Stefan, T., and Nazarov, A.D.. (2020). Challenges and competencies of leadership in COVID-19 pandemic: Proceedings of the Research Technologies of Pandemic Coronavirus Impact (RTCOV 2020), presented at the Research Technologies of Pandemic Coronavirus Impact (RTCOV 2020), Atlantis Press, Yekaterinburg, Russia

Stein-Zamir, C., Abramson, N., Shoob, H., Libal, E., Bitan, M., Cardash, T., et al. (2020). A large COVID-19 outbreak in a high school 10 days after schools’ reopening, Israel, may 2020. Eur. Secur. 25. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.29.2001352

Sveningsson, S., and Alvesson, M. (2003). Managing managerial identities: organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle. Hum. Relat. 56, 1163–1193. doi: 10.1177/00187267035610001

Sy, M. P., Park, V., Nagraj, S., Power, A., and Herath, C. (2022). Emergency remote teaching for interprofessional education during COVID-19: student experiences. Br. J. Midwifery 30, 47–55. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2022.30.1.47

Tao, W., Lee, Y., Sun, R., Li, J. Y., and He, M. (2022). Enhancing employee engagement via leaders’ motivational language in times of crisis: perspectives from the COVID-19 outbreak. Public Relat. Rev. 48:102133. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102133

Timmerman, A. (2008). Examining the relationship between teachers’ perception of the importance of the transformational individual consideration behaviors of school leadership and teachers’ perception of the importance of the peer cohesion of school staff. (Doctoral dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. (AAT 3306649).

Urick, A., and Bowers, A. J. (2014). What are the different types of principals across the United States? A latent class analysis of principal perception of leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 50, 96–134. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13489019

Welsh, R. O. (2022). School discipline in the age of COVID-19: exploring patterns, policy, and practice considerations. Peabody J. Educ. 97, 291–308. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2022.2079885

Wu, Y. L., Shao, B., Newman, A., and Schwarz, G. (2021). Crisis leadership: a review and future research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 32:101518. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101518

Wulandari, V., Hertati, L., Antasari, R., and Nazarudin, N. (2021). The influence of the Covid-19 crisis transformative leadership style on job satisfaction implications on company performance. Ilomata Int. J. Tax Account. 2, 17–36. doi: 10.52728/ijtc.v2i1.185

Zadok Boneh, M., Feniger-Schaal, R., Aviram Bivas, T., and Danial-Saad, A. (2022). Teachers under stress during the COVID-19: cultural differences. Teachers and Teaching 28, 164–187. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2021.2017275

Appendix– Interview Questions

1. Tell me about yourself, your professional background, and your school.

2. What did a school principal focus on in the routine (pre-COVID-19), with the staff and with the students? What major tasks and responsibilities did you have?

3. What are the main tasks, responsibilities, and authorities that have been added to you or sharpened for you as a principal since the COVID-19 crisis started (schooling from home, hybrid school, etc.)?

4. Were there any tasks that fell out of your responsibility? Can you demonstrate, please?

5. Which actions of you as a principal worked and which actions as a principal did you change or highlight during the COVID-19 crisis to motivate your staff?

6. What motivated you to these actions?

7. How did your employees respond to these actions? Can you give examples of successes and difficulties in motivating employees?

8. What were the short-term effects of these actions? Were there any achievements?

9. What are the long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis on the role of the principal and the roles of the school, as you perceive them?

10. How has your “creed” as a principal been seen after the COVID-19 crisis? Has it changed?

Keywords: COVID-19, crisis, integrated leadership, principals, transformational leadership, transactional leadership

Citation: Sheena D, Benoliel P and Berkovich I (2025) A qualitative exploration of principals’ transformational leadership and transactional leadership behaviors during the COVID-19 crisis: the rise of integrated crisis leadership. Front. Educ. 10:1576165. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1576165

Edited by:

Juhji, Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Maulana Hasanuddin Banten, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Hasan Baharun, Nurul Jadid University (UNUJA), IndonesiaMuhammad Adnan, Birmingham City University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Sheena, Benoliel and Berkovich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pascale Benoliel, cGFzY2FsZS5iZW5vbGllbEBiaXUuYWMuaWw=

Dan Sheena

Dan Sheena Pascale Benoliel

Pascale Benoliel Izhak Berkovich

Izhak Berkovich