- Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

This study investigated how undergraduate students define a lie and apply their definition when given more context in the form of scenarios. Sixty-five undergraduate students responded to questionnaires asking them to define a lie and then decide whether a lie was spoken along with a justification for their decision. All students determined that a lie contains a falsehood. However, there was disagreement about whether a speaker needed to intentionally tell a falsehood for a statement to be a lie. In addition, there was no single scenario that prompted unanimous agreement among the students as to what constituted a lie. Inconsistencies were documented between students’ personal definition of lies and the criteria they used to judge lies in the scenarios. Overall, this study contributed to the extant literature by investigating undergraduates’ perceptions of lies, comparing those definitions to their contextualized judgments, and gathering detailed justifications explaining their reasoning. The study also provides avenues for future research.

Introduction

“If a lie is only printed often enough, it becomes a quasi-truth, and if such a truth is repeated often enough, it becomes an article of belief, a dogma, and men will die for it” (Blagden, 1869).

As the quote by novelist and poet Blagden (1869) demonstrates, even in the mid-19th century, thinkers were concerned with the fuzzy distinction between what is truth and what is a lie. The conversation surrounding lying has morphed throughout history but has continued to be an important conversation even today. Deciphering what is a lie is a uniquely human experience that many authors have tried to capture through their creative works (Meltzer, 2003; Vrij et al., 2006). Understanding the veracity of information is crucial, as there could be dire consequences for people who believe a lie as the truth (Rapp and Salovich, 2018). Beyond whether a statement is a lie or not, there is also a conversation about whether it is ever justified to lie (Bok, 1978b; Leite, 2004). While often we teach children about the consequences and immorality of lying, there are cases where adults justify their lies (Bok, 1978a; Evans and Lee, 2013). As with most social and ethical issues, lying is complicated to define and to judge its acceptability.

Despite the common usage of the word lie in colloquial settings, a precise and specific definition of the word eludes philosophers, sparking disagreement (Bacin, 2023). The difficulty of creating one specific definition for scholars in philosophy, psychology, and education suggests that there might be varying understandings of lying within the public sector. Yet, researchers typically make an important assumption that their respondents understand a conceptual term in the same way as they do or effectively apply a definition given to them (Serota et al., 2010). However, this is not always the case.

Understanding how lying is defined and conceptualized by everyday people can help develop a better understanding of whether we are actually measuring lies in our research and the concept more broadly (Andiliou and Murphy, 2010; Arico and Fallis, 2013; Schoute et al., 2024). Thus, asking students explicitly how they define lies and enact their definitions in practice can provide insight into the construct of lying. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore further these definitions in an undergraduate setting in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of how these conceptualizations impact students’ decisions about whether a situation is a lie. In addition, this research combines the participants’ definitions of lies with the acceptability of certain situations to understand the moral implications of such lies.

Definition of lying

Philosophers consider several different characteristics of a situation to theoretically determine whether a statement is a lie or not (Mahon, 2008). Two of the most common characterizations include whether the information that is conveyed is false and whether the individual communicating that information intends for the receiver to be misled (Marsili, 2021). Isenberg (1964) presented a traditional definition of a lie beyond the standard dictionary entry, in which the most important aspect is the intentionality behind a statement. The actual validity of the information does not matter in distinguishing what is a lie and what is not. For example, if individuals tell another the opposite of what they themselves believe to be true, a statement is classified as a lie. This characterization focuses on the belief of what individuals state and their intended purpose of sharing information.

In contrast, others define a lie by adding the condition that a lie includes false or inaccurate information, as well as the intention to mislead another (Krishna, 1961). This means that if the underlying information shared is true, regardless of whether the person believes it or not, the statement cannot be a lie. The information needs to represent a falsehood. Further, there is a way of thinking about lying that does not include the necessity for intentionality (Shibles, 1985). Under this conceptualization, even if individuals have no intention of anyone believing their false information, the statement is still a lie if the information is false. This is also the case even if those individuals are unaware that the shared information is false. These two definitions from Krishna (1961), Shibles (1985) relate to each other because they consider the veracity of the information as a critical component of a lie, not necessarily the individuals’ intention behind sharing that information.

All these differing definitions of lying demonstrate the complex nature of understanding the veracity of information or the intentions of the person communicating that information. In sum, there appear to be two relevant disagreements among philosophers regarding lying. The first is whether the information must be categorically false for a statement to be a lie (Marsili, 2022). The second being whether the speakers want the other person to believe the opposite of what they are saying (Shibles, 1985).

Measuring the definition of lying

These debates also underlie psychological studies of lying in which researchers use scenarios to understand what people deem as necessary conditions for a lie (Rutschmann and Wiegmann, 2017; Turri and Turri, 2015; Weissman and Terkourafi, 2019). For instance, Weissman and Terkourafi (2019) provided students with example dialog in which a person might have lied. The following is an example of a situation and dialog shown to participants that represented a lie:

Rumors have spread about an incident in the art studio yesterday. Alex was in the studio all day and saw Sarah, frustrated with a project, fling a paintbrush across the room, breaking a window. Later that night in the studio, Alex accidentally tripped over a statue, causing it to smash all over the floor. The following day, Alex talks about Sarah’s incident.

Mark: I heard Sarah had a meltdown in the art studio yesterday! What happened?

Alex: You should’ve been there! In a fit of rage, Sarah picked up a hammer and broke a statue (Weissman and Terkourafi, 2019, p. 231).

Students were then asked whether the speaker (Alex in the previous dialog) told a lie. They also rated the extent to which that person lied on a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 represented that a lie definitely took place and seven represented that a lie definitely did not happen.

Using scenarios such as the previous, certain researchers move beyond the dichotomy of lie versus not a lie by considering that lies fall on a spectrum in which some lies are more prototypical than others (Coleman and Kay, 1981). Other psychologists have also used scenarios in their study of lies to introduce contextual factors into the determination of whether a situation constitutes a lie. In the current study, whether individuals were aware they were sharing inaccurate information was systematically varied in scenarios to understand whether undergraduates found this to be a necessary condition of a lie and if such awareness was a prototypical characteristic of a lie.

Acceptability of lies

Beyond just the practical definition of lies, the acceptability or perceived correctness of telling a lie has been heavily debated (Carson, 2010). There are two main sides of the debate that can be illustrated with two prominent philosophers. One side argues against lying in any circumstance, as exemplified by Bok (1978b). Because of her Principle of Veracity, Bok strongly argued against lying (i.e., intentionally trying to make someone believe the opposite of what the speaker does) regardless of the intended outcome of the lie. According to her principle, we can only expect others to tell us the truth if we also do not lie, and therefore, lies should not be told even if they appear to be justified. On the other side of the spectrum are those philosophers, such as Nyberg (1993), who think lying is essential to the maintenance of human society. Nyberg contended that lying is sometimes necessary and beneficial to society, making it sometimes an acceptable action. One such condition is if the truth would cause more harm to others, and it does not harm them to remain ignorant of the correct information.

These two differing philosophical viewpoints are also evident in psychological studies where participants are asked about how acceptable different types of lies are (Lindskold and Walters, 1983). Looking beyond philosophers’ ideas about how acceptable it is to lie provides more information about a general consensus of how the average person feels about lying. Several important factors have emerged that affect the acceptability of a lie. For one, the perceived acceptability of lies differs based on the purpose of a lie and the speaker’s relationship to the receiver of the lie. Lies have been described as most acceptable to tell when they are intended to avoid causing harm to those with whom a person is more intimately related (Cantarero and Szarota, 2017). In effect, when people feel like they are avoiding causing unnecessary harm to other people, they use this as a justification for lying. In addition, in order to maintain close relationships, lying is viewed as more acceptable when telling the truth poses harm to that relationship (Levine, 2021). This finding supports Nyberg’s (1993) understanding of lying as individuals’ efforts to maintain relationships with those around them.

The type of lie also greatly affects how people determine whether the action of lying is acceptable. When lies are perceived to be small or of little consequence, a person is more likely to say that it is acceptable to lie in that certain situation (Gozna et al., 2001). However, when the consequence of the lie is perceived to be significant and self-serving, the acceptability of the lie drops (Dunbar et al., 2016). Of course, there is no way to know the actual consequences of lying, even one that appears small on the surface. The gravity of a lie might differ based on the subjective evaluation of a situation. This may differ based on many factors such as general philosophy about lying (Ennis et al., 2008; Vrij and Holland, 1998), lived experience or cultural background (Reins et al., 2021; Seiter et al., 2002). For example, Ning and Crossman (2007) found in their study that people associated with a religious institution, namely the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints rated lies as less acceptable. Beyond religion, there are cultural differences in defining lies. In one study, Canadians were found to describe situations in which they hid that they did something socially positive as a lie, whereas their Chinese counterparts did not (Fu et al., 2001).

Thus, the perceived acceptability of lying may vary based on because of multiple factors, such as the seriousness of the lie or the intention of the lie. Differences in acceptability ratings of lying demonstrate how conceptualizing lies is highly dependent upon the evaluation of a situation. In this study, judgments of definitions and acceptability were connected to ascertain whether people would rate certain situations classified as lies less morally acceptable than situations not classified as lies.

Lingering questions

Despite the studies conducted around the concept of lying, there are still questions that remain about how students define lies and how this relates to how students situate lying in everyday contexts. When students are asked to report instances of lying, they are often not asked about how they personally define lying (DePaulo et al., 1996). Therefore, the researcher’s conceptualization of lying is assumed to be the one that participants hold, which could skew the results if this assumption is incorrect. Asking students explicitly about their definitions is a good way to unearth their conceptualizations of lying. This conceptualization can then be compared to students’ actual application of the definition in situations that provide more context. The context allows students to look at their proffered definitions with more nuance and may reveal more about how their definitions of lying are enacted. Comparing students’ decontextualized definitions with their enactment of those definitions in varied contexts allows us to examine conceptual consistency.

Another question that remains is what specific attributes of a lie seem the most salient when students make their decisions about whether a situation depicts a lie or not. Most previous research has utilized scenario-based methods to provide contextual examples (Rutschmann and Wiegmann, 2017; Seiter et al., 2002; Turri and Turri, 2015; Weissman and Terkourafi, 2019), but few researchers ask students to justify their reasoning as to why a statement would be a lie. In addition, scenarios are typically written in the third person, so students are not as actively placed as the actors of the lie, which may help them engage more with the context (Davis and Brock, 1975). While scenarios provide a rich context in which to examine lying, the important features that are used to judge a scenario might not be fully explored. These characteristics might also provide important information about what is most important to respondents in considering when a statement is a lie or not.

The current study

In this investigation, we sought to extend previous research on the definition and acceptability of lying by unearthing undergraduates’ personal conceptions and judgments using a scenario-based task. Specifically, 10 scenarios depicting relatable events to college students were developed to vary systematically in terms of whether a person was aware they were sharing false information and the relationship between the conveyer and recipient of the information. These students were asked to provide a personal definition of a lie and were then asked to make judgments about whether each scenario contained a lie to address the following research questions. In effect, we wanted to explore whether these students’ personal definitions of a lie corresponded to their awareness of the conditions represented in those ten scenarios. The research questions guiding this study were as follows:

1. Based on their personal definitions, what attributes do undergraduates consider necessary to make a statement a lie?

2. When presented with scenarios that vary in terms of salient factors associated with lying:

a. When do undergraduates determine that lying has occurred or not?

b. Upon what salient factors within the scenarios do students base their decisions?

3. Are students consistent in how they define a lie and whether they judge a scenario to contain a lie?

Materials and methods

Participants

Sixty-five undergraduate students from a major university in the mid-Atlantic region were recruited to participate in this study. College students were recruited because all of the scenarios were designed to be as relatable as possible to this group. In addition, college is a time of moral development, which means that understanding the complexities of lying in this population is quite important (King and Mayhew, 2004). Students were taking courses related to educational psychology. A majority of the participants identified as women (n = 47) and white (n = 44). White women were overrepresented compared to the overall population at the university. Students also indicated their class rank; six students were freshmen, 26 were sophomores, 15 were juniors, and 18 were seniors. Because most of the extant literature on lying has focused on undergraduates, the choice of this population seemed quite appropriate.

Measures

Students completed two surveys that assessed their conceptions and judgments about lying. Students were asked to complete the measure in a quiet space using the Qualtrics® platform.

What is a lie questionnaire?

The first measure probed students’ personal definitions of a lie without any contextual references. Then students were presented with five open-ended questions that were informed by the literature on lying. The first question, which was the most general, simply asked the students, “How do you define what a lie is?” They were then asked four more specific questions intended to explore those personal definitions and told to explain their responses:

1. Is awareness of the liar necessary for something to be a lie?

2. Are there circumstances when lying is preferable to not lying?

3. Do people lie every day?

4. Are there different categories of lies?

Judgment of lying scenarios

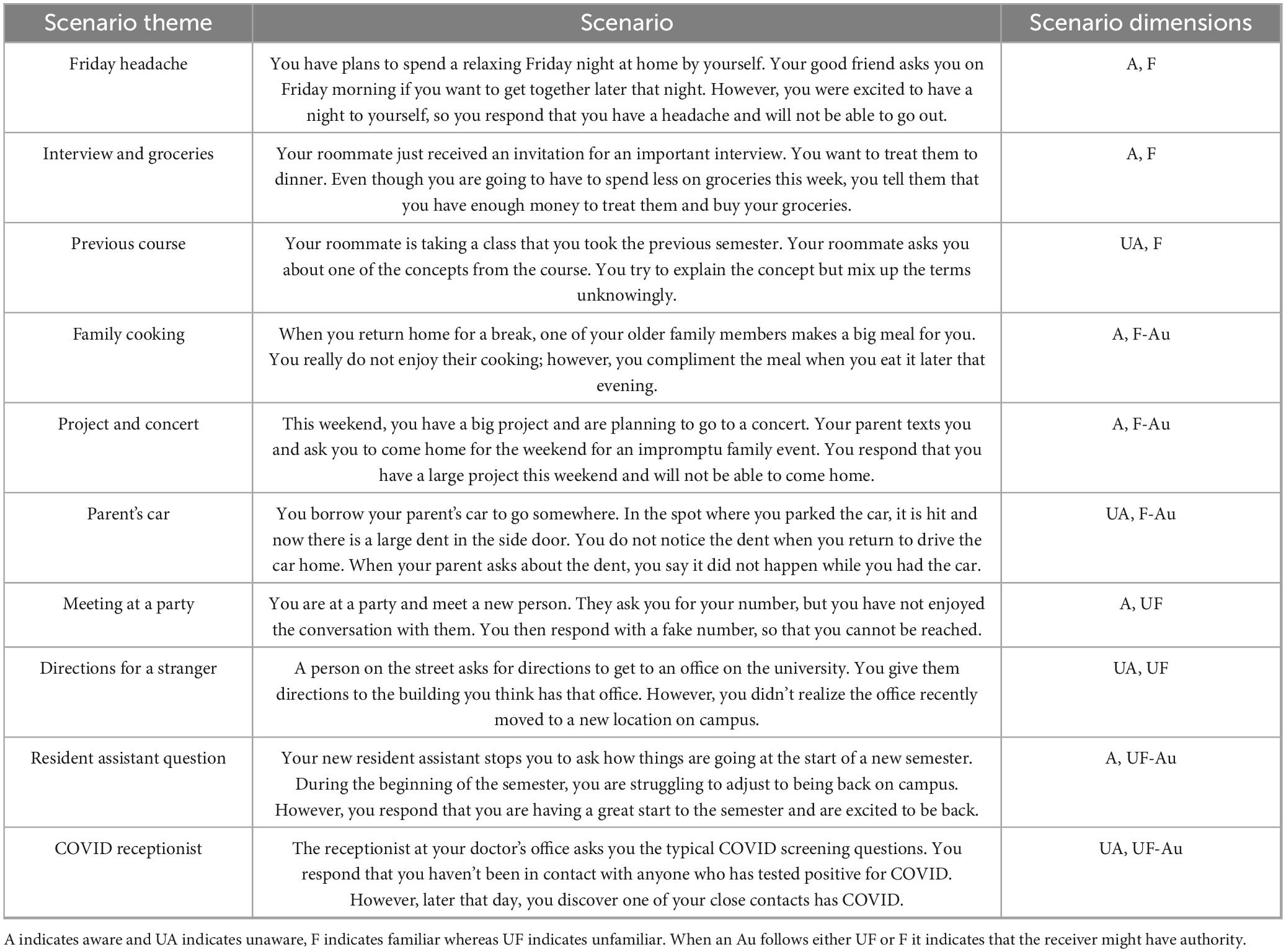

The second measure asked students to respond to 10 scenarios meant to capture instances of lying occurring in everyday situations. These scenarios were developed to differ on three key attributes frequently associated with lying in the literature in order to further parse out what students believed to be essential parts of lies. These attributes included the awareness of the speaker, the closeness of the relationship to the speaker, and the authority position the receiver of the statement holds (see Table 1). In regard to the awareness of the speaker, two conditions were created: one scenario where speakers were aware they were saying false information and another where speakers did not know the information, they were sharing was false in order to assess whether this was a key attribute of lies to undergraduates.

In addition, the familiarity level of the person to whom a person was speaking was systematically altered. There were two main attributes in regard to the relationship of the receiver of the statement. The first was whether the person spoken to has a close relationship with the speaker or not; that is, whether the recipients of the information were familiars or strangers. Then there are some scenarios in which the speakers were presumably peers of receivers of the statement and others where the speakers held some sort of authority over or deference toward the recipients, such as a parent, elder, or medical professional. The difference in relationship was altered to assess whether this mattered in terms of definition and acceptability of the situations (DePaulo and Kashy, 1998).

After reading the scenario, the students had to decide if the speakers lied or not and justify their decision. They were presented with these scenarios in a random order. Students were to respond to these scenarios as if they were the speaker. In addition, they were asked to rate on a 100 mm scale ranging from “completely unacceptable” to “completely acceptable” how morally acceptable the response in each scenario was. They then rated the extent to which they thought most people would respond in a similar fashion on 100 mm scale ranging from “very unlikely” to “very likely.”

Scoring

Each definition was coded based on three characteristics: whether students mentioned false information, intentionality or awareness, or another person. After this coding, these definitional characteristics were compared to judgments that students made about the 10 scenarios as a way to explore the consistency of their conceptions of lying. decisions students made regarding whether each scenario represented a lie. For example, if students did not include any mention of intentionality in their definitions, but then used the intent of the speaker as a main justification influencing their decisions to classify a lie, then their responses were coded as inconsistent.

To establish interrater agreement, the first author and a second trained rater scored 10 percent of the participants’ responses. The interrater reliability was 91.8%.

Results and discussion

Several interesting patterns emerged from the coding of the undergraduates’ definitions and scenario judgments relative to the research questions we posed. Sixty-five students responded, and all students were included in the data analysis. The results will be presented in order of the questions by exploring students’ definitions, analyzing their scenario judgments, and combining their definitions and judgments to gauge the consistency of students’ conceptions.

Personal definitions

Each student’s definition was coded based on three key attributes: whether the student mentioned falseness, intentionality, or another person. All 65 (100%) students mentioned falseness and 42 (65%) mentioned only this attribute in their definitions. Eight (12%) students also mentioned intentionality in their definitions, 7 (11%) mentioned another person, and 8 (12%) mentioned both intentionality and another person.

Falseness

The first research question of this project inquired about how students defined a lie when asked to do so. Differences in their personal definitions were expected to align with some of the philosophical debates expressed in the literature. For example, every student (100%) mentioned that the information conveyed had to be false in order for a statement to be a lie. Additionally, there were 42 (65%) students who only referenced the validity of the information. For example, Sammy1 wrote that “A lie is a claim that is fabricated, so it is not the truth.” This rather terse definition was similar to those produced by others who only referenced the veracity of information in their definitions of a lie.

Other undergraduates made their definitions a bit broader to contain both explicitly false information and misleading information. For instance, Jesse stated, “A lie is when you are dishonest or misleading. It is when you do not tell the truth.” The definition incorporates information that might not be completely false but has some information that is also not completely accurate. This pattern aligns well with both the philosophical and psychological literature on lying, specifically Krishna’s (1961) definition where the information needed to be false to be constituted a lie.

Awareness and intentionality

Another emerging pattern in these definitions regarded whether individuals need to be aware when they lie. Students did not distinguish between awareness and intentionality as is sometimes done in philosophical literature, where awareness means that you know the information is untrue while intentionality means that you want the other person to believe something different than you do (Chisholm and Feehan, 1977). Rather, these undergraduates seemingly used them interchangeably when expressing their understanding of a lie, which is why they were combined in the following discussion. Specifically, only 16 students (27%) referenced the necessity of intentionality when spreading false information for something to be a lie. For example, Taylor said “I define a lie as an intentional statement that inaccurately portrays a situation.” More students later referenced intentionality in their justification of scenarios.

Definitions ranged from Shibles “An intentional fabrication of facts or opinions” to Jacob’s “A lie is when a person purposefully conceals the truth with an intent to change the outcome of a situation or reaction of the person to which the lie is being told.” These two both convey intentionality as a necessary condition for a statement to be a lie, but the latter provides more reasoning for why a person may have an intention to hide the truth.

Reference to others

Only 15 (23%) of the students made an explicit reference to the receiver of the lie. Eight of these students included those who wrote about intentionality, meaning they had both those characteristics in their definitions. Kevin mentioned that another person is present during the verbal exchange and the goal of the lie might be to influence the other person directly. An example when the student referenced the recipient of the lie, but not the intentionality of the person, was offered by Emily who said, “a lie is provid[ing] false information to others.” Interestingly, this description did not acknowledge whether the information was objectively false or whether the speaker needed to be aware of the false information in order for this to be classified as a lie.

These three attributes, falseness, awareness, and another person, were all factors mentioned in both the philosophical and the psychological literature, demonstrating that this group of students had similar considerations about lies as those regarded as experts in this domain of inquiry. Specifically, while there were variations in how students responded to the definitional prompt, their definitions of lying reflected philosophical and psychological concerns over the veracity of information and intentionality.

What is a lie questions

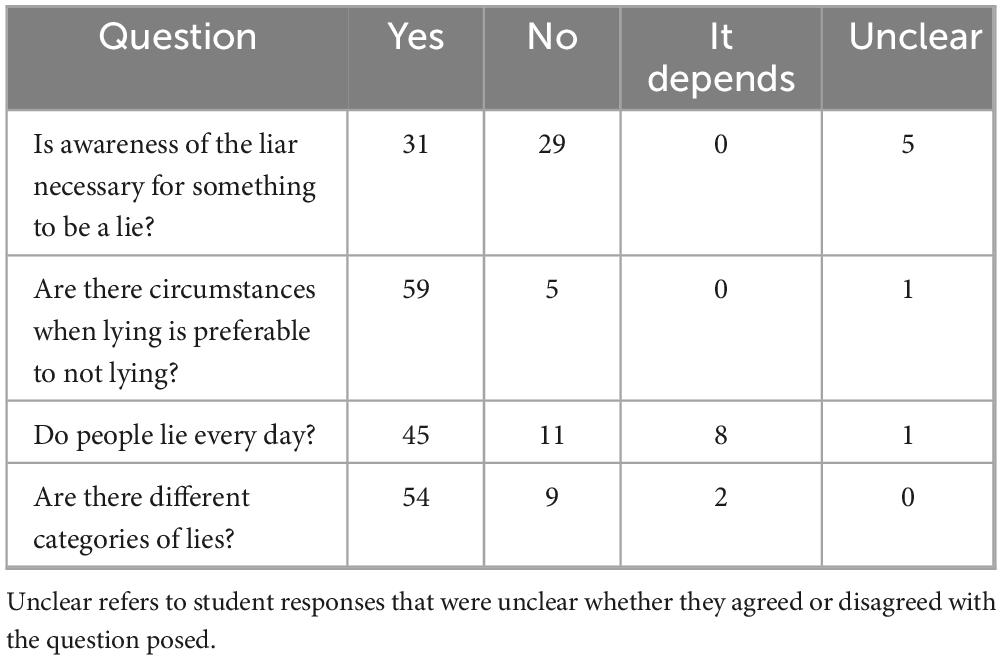

Table 2 outlines the undergraduates’ responses to specific questions about lying that followed their personal definitions that they then explained. For one, 31 (48%) of the 65 students said that awareness of the liar is necessary for a statement to be a lie, and the vast majority (59; 91%) said that there are circumstances in which lying is preferable to telling the truth. Also, 45 undergraduates (69%) said that they believed people lie every day, while 54 (83%) students agreed that there were different categories of lies.

Scenario judgments

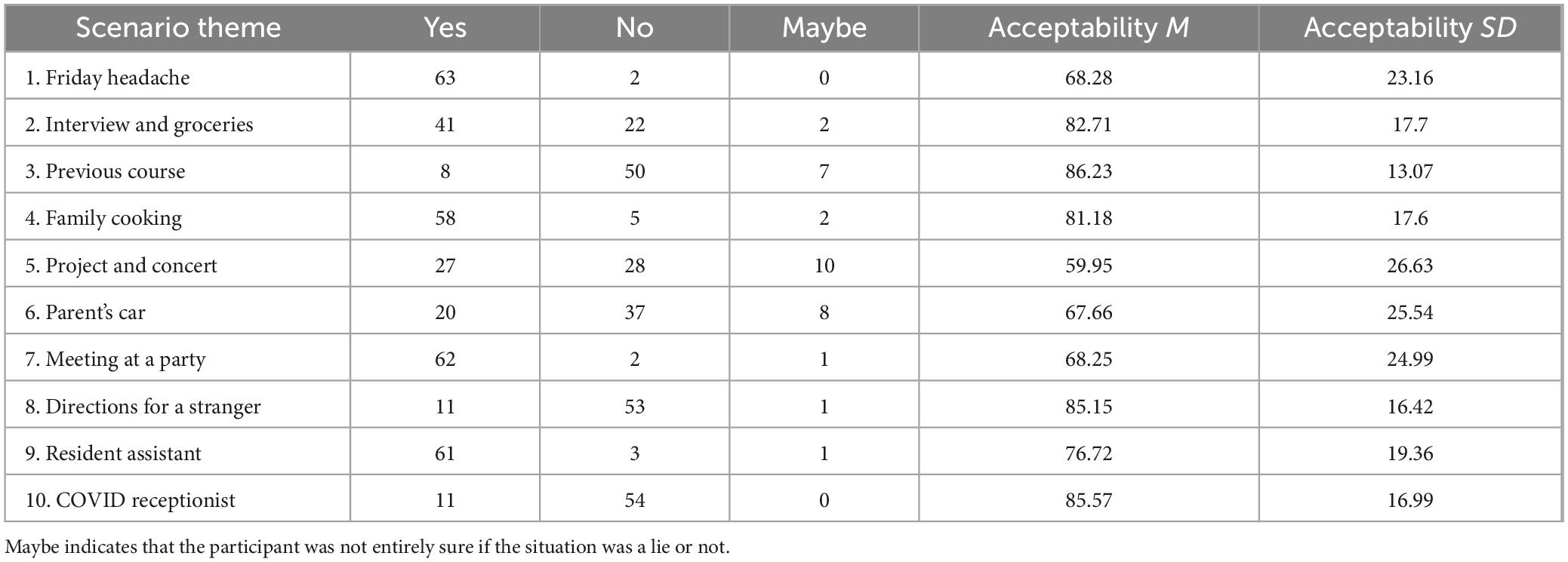

Table 3 provides the descriptive data on the undergraduates’ judgments as to whether each of the scenarios described in Table 1 depicted a lie or not. After each judgment, the students rated the acceptability of the speaker’s actions on a scale ranging from 0 (completely unacceptable) to 100 (completely acceptable). It should be noted that some students indicated that they were unsure whether the scenario depicted a lie or not.

The second research question addressed whether there was a pattern in how these undergraduates classified the 10 scenarios that were generated to differ in systematic ways as a lie or not. For one, as shown in Table 2, none of the scenarios prompted unanimous agreement among the students, as might be expected given the complex nature of lying. Despite this fact, there were characteristics about which these students manifested high levels of agreement. For one, as seen in scenarios 1, 4, 7, and 9, students were likely to rate situations in which there was an awareness that the speaker was sharing false information as a lie. This pattern held regardless of the significance of the lie or the speaker’s familiarity with the recipient. For another, most students readily said that the action in these scenarios was a lie and referenced the intentionality of the speaker as the reason.

Interestingly, even when students viewed the speaker’s actions as a case of lying, many explained why telling a lie in this instance was acceptable. One example comes from scenario 4, when individuals state that they like the food even when they do not. Jennifer stated, “Yes, this is a lie. The intention of the lie was to compliment my family member and not make them feel bad about their cooking. I think that me lying in this scenario outweighs them getting hurt over their food.” Jennifer agreed that the speaker’s response was a lie, but explained why, in this context, it was preferable to the truth. Those who said this scenario was not a lie explained that it was being nice instead of lying, showing how the positive intent outweighed calling the situation a lie. Drew took this position, “Based on the knowledge that is being presented, I do not view this form of compliment as a lie, as it would comfort the individual and not hurt their feelings severely which can lower the level of their self-esteem.” The positive acceptability ratings for this particular scenario align with previous researchers findings that people view prosocial lies to be more acceptable because the purpose of them is to try to maintain relationships (Levine and Lupoli, 2022).

When students classified scenarios as not depicting a lie, the scenarios typically included examples where people were not aware they were sharing false information. Students often justified these situations as “mistakes.” One example of this is in scenario 3, where the speaker gives incorrect information to a roommate without knowing it. A common justification for why this did not qualify as a lie was the speaker’s lack of intent to share false information. For instance, in her explanation as to why this was not a lie, Lisa wrote, “No because I just made an unknown mistake–not intentional.” On the other hand, those who did judge this situation as a lie often referenced only the veracity of the information being shared as the criteria for that determination. Since the information was false, the statement should be regarded as a lie to these students, regardless of the intent. This was exemplified by Andy, who said, “Yes, you told something that was not the truth. But you told the lie unknowingly, and without the intent to harm the other person. In fact, you are trying to help, but you told a lie unintentionally. But you still did not say the truth.”

Finally, students were more likely to indicate they were unsure if a situation contained a lie when the speaker left out certain information. In their justifications, students often discussed the conditionality of lying; that is, why a scenario might depict a lie under some contexts but not others. For that reason, those students then did not distinctly say whether lying occurred or not. An example of this phenomenon is shown by Peyton, who explained the uncertainty about situation 5 by saying “I’m not sure if it’s an entire lie? There’s truth in it since there’s a project happening on the weekend aside from the concert. However, it would be a lie if I said I have a project for the entire weekend just to avoid the family event.”

Students also provided average acceptability ratings for each scenario. Specifically, all the scenarios were rated as more acceptable than not acceptable because they had ratings over 50%. In general, situations that were viewed as more acceptable were when the intention of the lie was to not harm the other person in the situation, or the information shared was mistakenly false. These findings parallel other studies in the literature in which students reported that telling pro-social lies was more acceptable than lying for one’s own benefit (Levine, 2021). All of the situations rated above 80% on the acceptability scale either involved a situation where students did not think a lie occurred or situations when a lie was said to mask negative feelings such as lying when you did not like someone’s cooking.

Certain situations were shown to have more variability than others. This was the case when students showed disagreement about whether the situation was a lie, such as 5 and 6. However, there were certain situations that also sparked disagreement when the majority of students said that a lie occurred, specifically in scenario 1 and 7. When someone gave an incorrect phone number and knew they were doing so, acceptability varied, with some viewing this as extremely acceptable because it offered protection to the individual, while others did not think this was acceptable because it was clearly not their phone number. The difference here may be due to individual differences in the analysis of the intention or consequence of the lie.

Students’ internal consistency

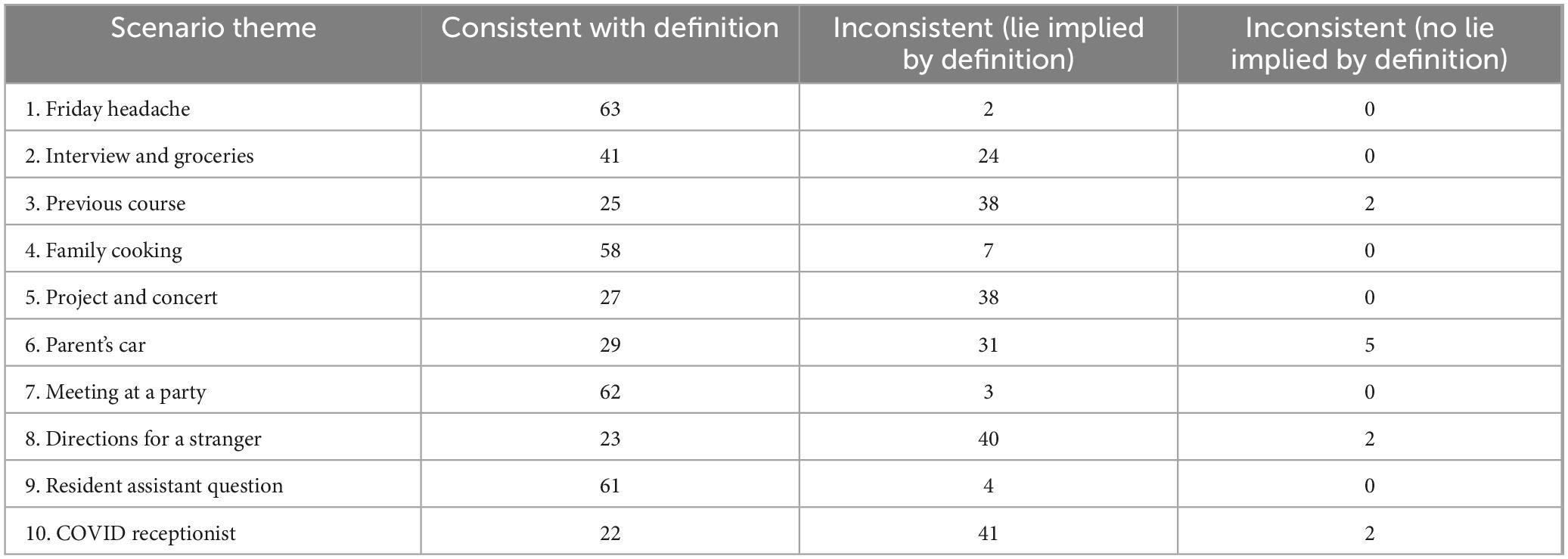

The final research question focused on whether there was consistency in how students defined lying and their judgments about scenarios that captured different dimensions associated with lying. In Table 4, we display results for whether students’ personal definitions are consistent with their responses about the scenarios. For example, if students stated that a lie is when a statement is untrue, then they should have indicated that a scenario, like 3, depicted a lie because the information shared was factually untrue. In those instances where there was a discrepancy between students’ personal definitions and their scenario judgments, we considered the source of the inconsistency. Specifically, did the inconsistency arise because the students’ definitions implied that they should have or, conversely, should not have judged the action in a scenario as representing a lie?

As can be seen in Table 4, two main patterns emerged from this analysis. First, for those scenarios in which speakers were aware they were spreading false information (i.e., 1, 4, 7, and 9), students were fairly consistent in their judgments. In fact, for scenario 1, only two people said that this was not a lie, although their personal definition implied that a lie was communicated. Second, when students displayed inconsistencies, the scenarios conveyed that the speaker was unaware that the information being shared was false (i.e., 3, 6, 8, and 10). The inconsistency happened typically because students did not mention intentionality in their personal definitions. However, they used that characteristic as the criteria for judging whether the action depicted was a lie or not. This pattern was exemplified by Sam, who originally defined a lie by saying “A lie is an assertion that does not contain complete truth.” Yet, when explaining why he did not think scenario 8 depicted a lie, he said, “No. I (the speaker) was unaware that it has changed and therefore was not lying.” Sam clearly used the awareness of the situation as a critical component of defining a lie, but based only on their definition, the assertion does not contain complete truth, even if you do not realize it. Thus, this response pattern suggests that when prompted to give a basic definition of lying, students may omit certain aspects they hold as salient. However, when given more contextual information, students reveal a more nuanced conceptualization of a lie or the act of lying. Finally, some of the students who left out awareness in their definition and judged scenarios by this metric, did in fact answer that awareness was a component of a lie when prompted with the next question of awareness, which would suggest that only when prompted to think more deeply about their definitions, did they consider this factor, but then would use it consistently in their definitions. This might suggest that the prompting in the follow-up questions induced deeper thinking about what a lie was and then helped students in applying these definitions.

Further, most of those students who included intentionality then used this as a justification when explaining why a scenario was a lie or not. When the students originally created this rich definition, they then applied the definition more consistently across the scenarios, potentially suggesting that they had a more developed sense of what they themselves considered a lie and then applied it more consistently. Very few students had a definition that would suggest that there was not a lie that had taken place, but judged the situation to be a lie, further adding evidence to the fact that the majority of students under defined the construct at the outset.

Finally, there were a few aberrant students who showed a pattern of complete inconsistency in their responses. A few students did not include awareness in their answer and said awareness was not necessary when telling a lie, which would indicate that if the information was untrue the situation would be a lie. The student then proceeded to define scenarios, such as 3, as not a lie because the speaker was not aware the information that they were sharing was false. All indications of their responses suggested that the mere fact that the information was untrue should constitute a lie. Therefore, once these students moved onto the scenarios, the definition they provided was not used in their judgments of the situations. These students would be interesting to follow up with interviews to gain a deeper understanding of what they were thinking or considering when answering these questions.

In sum, students had dimensions that they typically considered when determining whether something was a lie or not. The falseness of the information was one characteristic that all respondents considered when writing their definitions. Some students also took into account whether the person intended to lie or not. In contrast, when judging scenarios that differed along key characteristics of lying, there was no unanimous agreement on any situation. Even so, students’ judgments were quite similar when the speakers were aware that they were spreading untrue information. Finally, the scenarios in which speakers were unaware that they told a lie were the least consistent with students’ personal definitions. That inconsistency arose primarily because the students did not mention intentionality in their definition, but then used it to justify why the scenario depicted a case of lying.

Conclusion and implications

The goal of this research was to answer three main questions: how students naturally defined a lie when asked, how they judge different scenarios, and whether their original definitions were consistent with how they judged scenarios. All students considered the veracity of information when defining a lie, but not all considered intentionality or awareness. However, many of those who did not consider intentionality in their original definitions then used it as a justification for why they judged a scenario to be a lie. Therefore, there were many students who demonstrated an inconsistency between their definition and their judgments. Students tended to provide more detailed justifications about why they decided something was a lie compared to their written definitions.

Scenarios and definitions

This study provides some evidence of the utility of asking students how they define words before making judgments in context. Asking students what they think a certain word means can provide researchers with more context about how participants are responding to questions. However, students are not always extensive in their definitions, which demonstrates the importance of giving more context to apply definitions. Without more context, students might not recognize all elements critical to their own definitions. Therefore, definitions and definition applications can also be used to examine students’ consistency. In this study, it allowed us to examine what elements of lies students were less likely to use in definitions but apt to use in actual decision making.

Further, as in the literature (Arico and Fallis, 2013; Backbier et al., 1997; Dunbar et al., 2016), scenarios were found to be a useful methodology to examine more nuanced parts of students’ definitions because they could use specific aspects of scenarios to decide if something is a lie or not. However, there could be room for expanding current understandings of lying when using scenarios through participant input and focus groups and their judgments of the relatability of scenarios. This would allow participants to indicate aspects of lying that they find more complex and, in turn, would help researchers develop scenarios that might have varied responses due to their complexity. In addition, involving people from the target population in developing scenarios can help to make the scenarios most relevant as well as comprehensible. In this study, there were instances when the wording of certain scenarios seemed to leave students confused as to whether the speaker was aware they were saying false information. Researchers could prevent such confusion by piloting the wording of the scenarios with a similar age group to ensure their comprehensibility.

Finally, asking students for written justifications for their decisions in this study, rather than using yes/no or Likert-type items, allowed us to gain insight into what specific aspects of situations students considered salient judgments of lying. For instance, this methodological feature highlighted the importance of intentionality when deciding whether something was or was not a lie. However, because students were allowed free space to write as they wished, there were some ambiguous statements they made a, making it challenging to follow their logic. Therefore, it was difficult to make determinations for some students about the attributes present in their definitions. Following up with students in an interview-based format would have helped to alleviate some of these ambiguities and could have provided more insight into the student’s decision about whether a scenario contained a lie.

Understanding of lies

This study corroborates findings from previous literature about the components of lying that are salient when determining a precise definition of lying. First, students seem to overwhelmingly include false information as a requisite for a statement to be a lie, similar to Turri and Turri’s (2015) findings. In addition, intentionality is a component not always required for a statement to be a lie (Rutschmann and Wiegmann, 2017). More insight from more studies allows for a more complex and thorough understanding of what people understand a lie to be.

Where this study expands on prior research on lying is in the juxtaposition of definitions and application. Some students appear to omit certain salient aspects of their definition of lies that is then used in application, in this case intentionality. Prompting students to explain their reasoning allows us to see that the students are often using intentionality when making decisions about lies, but this is often omitted from their definition. This omission might point to the complexity of intentionality as it requires more prompting, such as context, for some students to fully address this aspect of lying. More interview data could help elucidate whether students do find this aspect of lying more complicated or harder to recognize.

The scenarios in the current study differ from those typical in the lying literature in several ways. For one, they were written in first person. This required the students to assume that they were the speakers in the scenario and not simply a disassociated evaluator. This decision was made to enhance the personal relevance of the task for participants (Schoute et al., 2024), and to increase the value of making thoughtful determinations about lies. However, because there are not many other studies that use this approach, replication is required. For example, would students be more likely to decide a situation is a lie when people are not aware they are sharing false information based on the speaker in the scenario?

A final future direction was prompted by students’ discussion about potentially positive motives for protecting others as a justification for making untrue statements. Other researchers have also suggested that the intent behind the lie affects how acceptable people find a lie to be (Levine, 2021). This study also suggests that this rationale can be important to some students’ determination as to whether a statement was actually a lie or not. These two ideas raise the question of whether students find intended or actual consequences more important in the determination of what constitutes a lie. Does the time between the speaking of the lie and the discovery of a lie impact a person’s interpretation? For example, does it matter if someone finds out about a lie immediately versus a day later? These questions could also be further studied to gain an even deeper understanding of how people understand what it means to lie.

Implications for education

This work on lying has potential implications for the educational setting, especially given that these students were in college. First, it stands to reason that there may be disagreements about what constitutes academic dishonesty, as there was a lack of agreement on whether someone was unaware that the information they were sharing was false. Teachers and administrators should make sure to reinforce their conception of academic dishonesty to students so that those students are not confused about what academic dishonesty means.

In addition, the idea of prompting could be further investigated in the academic sphere. There were some students who omitted certain key components of the definition they applied to the scenarios. However, they were able to answer questions about those specific attributes of their definitions when prompted to think about whether awareness was necessary for a lie. The same could be done for academic dishonesty or for students to think about other important definitions. Educators can help students identify when they are being incomplete using this type of strategy, which has shown promise in science learning (Law and Chen, 2016), but could be applied to more philosophical contexts as well.

In conclusion, this study set out to investigate how undergraduate students define lies and whether they retain their definitional attributes when provided with contexts differing on several dimensions. The study attempted to expand on prior research in which students decided whether there was a lie in a specific situation by allowing students to provide justifications about their decision making. In this study, students all included a falsehood in their definition, but there were differences in regard to whether the speaker’s intentionality was needed for a statement to be a lie. In addition, the issue of intentionality was the main reason for inconsistencies between students’ definitions and their judgments of scenarios. Overall, this study demonstrated the complex nature of lying.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Maryland – College Park, Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. PA: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^All student names are pseudonyms.

References

Andiliou, A., and Murphy, P. K. (2010). Examining variations among researchers’ and teachers’ conceptualizations of creativity: A review and synthesis of contemporary research. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 201–219. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2010.07.003

Arico, A. J., and Fallis, D. (2013). Lies, damned lies, and statistics: An empirical investigation of the concept of lying. Philos. Psychol. 26, 790–816. doi: 10.1080/09515089.2012.725977

Bacin, S. (2023). “Lying, deception, and dishonesty: Kant and the contemporary debate on the definition of lying,” in Kant and the problem of morality: Rethinking the contemporary world, 1st Edn, eds L. Caranti and A. Pinzani (New York, NY: Routledge), 73–91. doi: 10.4324/9781003043126

Backbier, E., Hoogstraten, J., and Terwogt-Kouwenhoven, K. M. (1997). Situational determinants of the acceptability of telling lies. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 27, 1048–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb00286.x

Cantarero, K., and Szarota, P. (2017). When is a lie more of a lie? Moral judgment mediates the relationship between perceived benefits of others and lie-labeling. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 48, 315–325. doi: 10.1515/ppb-2017-0036

Carson, T. L. (2010). “Honesty as a virtue,” in Lying and deception: Theory and practice, ed. T. L. Carson (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 257–266. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199577415.003.0015

Chisholm, R. M., and Feehan, T. D. (1977). The intent to deceive. J. Philos. 74, 143–159. doi: 10.2307/2025605

Coleman, L., and Kay, P. (1981). Prototype semantics: The english word lie. Language 57, 26–44. doi: 10.1353/lan.1981.0002

Davis, D., and Brock, T. C. (1975). Use of first person pronouns as a function of increased objective self-awareness and performance feedback. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 11, 381–388. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(75)90017-7

DePaulo, B. M., and Kashy, D. A. (1998). Everyday lies in close and casual relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 74, 63–79. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.63

DePaulo, B. M., Kashy, D. A., Kirkendol, S. E., Wyer, M. M., and Epstein, J. A. (1996). Lying in everyday life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 70, 979–995. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.979

Dunbar, N. E., Gangi, K., Coveleski, S., Adams, A., Bernhold, Q., and Giles, H. (2016). When is it acceptable to lie? interpersonal and intergroup perspectives on deception. Commun. Stud. 67, 129–146. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2016.1146911

Ennis, E., Vrij, A., and Chance, C. (2008). Individual differences and lying in everyday life. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 25, 105–118. doi: 10.1177/0265407507086808

Evans, A. D., and Lee, K. (2013). “Lying, morality, and development,” in Handbook of moral development, 3rd Edn, eds M. Killen and J. G. Smetana (England: Routledge), 361–384.

Fu, G., Lee, K., Cameron, C. A., and Xu, F. (2001). Chinese and Canadian adults’ categorization and evaluation of lie- and truth-telling about prosocial and antisocial behaviors. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 32, 720–727. doi: 10.1177/0022022101032006005

Gozna, L. F., Vrij, A., and Bull, R. (2001). The impact of individual differences on perceptions of lying in everyday life and in a high-stake situation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 31, 1203–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00219-1

Isenberg, A. (1964). Deontology and the ethics of lying. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 24, 463–480. doi: 10.2307/2104756

King, P. A., and Mayhew, M. J. (2004). “Theory and research on the development of moral reasoning among college students,” in Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, Vol. 19, ed. J. C. Smart (Dordrecht: Springer), 375–440. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-2456-8_9

Krishna, D. (1961). ‘Lying’ and the compleat robot. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 12, 146–149. doi: 10.1093/bjps/XII.46.146

Law, V., and Chen, C.-H. (2016). Prompting science learning in game-based learning with question prompts and feedback. Comp. Educ. 103, 134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.10.005

Leite, A. (2004). On justifying and being justified. Philos. Issues 14, 219–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-6077.2004.00029.x

Levine, E. E. (2021). Community standards of deception: Deception is perceived to be ethical when it prevents unnecessary harm. J. Exp. Psychol. General 151, 410–436. doi: 10.1037/xge0001081

Levine, E. E., and Lupoli, M. J. (2022). Prosocial lies: Causes and consequences. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 43, 335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.006

Lindskold, S., and Walters, P. S. (1983). Categories for acceptability of lies. J. Soc. Psychol. 120, 129–136. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1983.9712018

Mahon, J. E. (2008). Two definitions of lying. Int. J. Appl. Philos. 22, 211–230. doi: 10.5840/ijap200822216

Marsili, N. (2021). Lying, speech acts, and commitment. Synthese 199, 3245–3269. doi: 10.1007/s11229-020-02933-4

Marsili, N. (2022). Lying: Knowledge or belief? Philos. Stud. 179, 1445–1460. doi: 10.1007/s11098-021-01713-1

Meltzer, B. M. (2003). Lying: Deception in human affairs. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 23, 61–79. doi: 10.1108/01443330310790598

Ning, S. R., and Crossman, A. M. (2007). We believe in being honest: Examining subcultural differences in the acceptability of deception. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2130–2155. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00254.x

Nyberg, D. (1993). The varnished truth: Truth telling and deceiving in ordinary life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rapp, D. N., and Salovich, N. A. (2018). Can’t we just disregard fake news? The consequences of exposure to inaccurate information. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 5, 232–239. doi: 10.1177/237273221878519

Reins, L. M., Wiegmann, A., Marchenko, O. P., and Schumski, I. (2021). Lying without saying something false? A cross-cultural investigation of the folk concept of lying in Russian and English speakers. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 14, 735–762. doi: 10.1007/s13164-021-00587-w

Rutschmann, R., and Wiegmann, A. (2017). No need for an intention to deceive? Challenging the traditional definition of lying. Philos. Psychol. 30, 438–457. doi: 10.1080/09515089.2016.1277382

Schoute, E. C., Alexander, P. A., Loyens, S. M., Lombardi, D., and Paas, F. (2024). College students’ perceptions of relevance, personal interest, and task value. J. Exp. Educ. 92, 76–100. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2022.2133075

Seiter, J. S., Bruschke, J., and Bai, C. (2002). The acceptability of deception as a function of perceivers’ culture, deceiver’s intention, and deceiver-deceived relationship. Western J. Commun. 66, 158–180. doi: 10.1080/10570310209374731

Serota, K. B., Levine, T. R., and Boster, F. J. (2010). The prevalence of lying in america: Three studies of self-reported lies. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 2–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01366.x

Turri, A., and Turri, J. (2015). The truth about lying. Cognition 138, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.01.007

Vrij, A., Akehurst, L., Brown, L., and Mann, S. (2006). Detecting lies in young children, adolescents and adults. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 20, 1225–1237. doi: 10.1002/acp.1278

Vrij, A., and Holland, M. (1998). Individual differences in persistence in lying and experiences while deceiving. Commun. Res. Rep. 15, 299–308. doi: 10.1080/08824099809362126

Keywords: lying, lying definition, deception, intentionality, scenario-based methods

Citation: Maki AJK and Alexander P (2025) Undergraduates’ understanding of what it means to lie. Front. Educ. 10:1579940. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1579940

Received: 24 March 2025; Accepted: 26 May 2025;

Published: 24 June 2025.

Edited by:

Antonio Sarasa-Cabezuelo, Complutense University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Tilman Fries, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, GermanySaleem Abdelhady, American University of the Middle East, Kuwait

Copyright © 2025 Maki and Alexander. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alina J. K. Maki, YW1ha2kxM0B1bWQuZWR1

†ORCID: Alina J. K. Maki, orcid.org/0000-0002-1277-3540; Patricia Alexander, orcid.org/0000-0001-7060-2582

Alina J. K. Maki

Alina J. K. Maki Patricia Alexander

Patricia Alexander