- School of Foreign Languages, China University of Petroleum, Beijing, China

This study examines the implementation of place-based education in rural English teaching in China through a mixed-methods approach, encompassing surveys and interviews with rural middle school students and teachers. The findings reveal significant challenges, including the disconnection between English education and local culture, the limited integration of local knowledge into textbooks, and the absence of localized professional development for educators, etc. Both students and teachers report insufficient incorporation of local cultural elements into English classes, which adversely affects learning engagement and cultural identity formation. To address these issues, the study proposes a “Dual-Core” approach. The first core focuses on establishing an educational team that prioritizes optimizing decision-making processes, integrating resources, and refining evaluation systems. The second core emphasizes enhancing teachers’ and students’ awareness of local culture through targeted beliefs training, preparation training, and curriculum training. These measures aim to enhance teaching effectiveness, strengthen students’ connection to their communities, and contribute to rural revitalization efforts. This research provides actionable recommendations for advancing English education in rural areas, promoting educational equity, and fostering cultural sustainability.

1 Introduction

Place-based education (PBE) emerges as a transformative approach to integrating local cultural, ecological, and social elements into teaching, particularly in rural settings. By connecting education with students’ lived realities, PBE enhances the relevance of teaching and fosters a deeper sense of community engagement and cultural identity (Sobel, 2004; Ding et al., 2023b). In the context of China’s rural education, this disconnect is particularly pronounced in English language classrooms, where abstract, decontextualized curricula often bear little relevance to students’ daily lives or local knowledge systems (Zhang, 2022; Liu, 2023; Guo, 2022). Responsively, the adoption of PBE has the potential to transform how English is taught and learned (Chai and Li, 2024; Wang W. T., 2024).

China’s countryside stands apart from rural areas in many other countries due to its rich cultural heritage, distinctive local traditions, and the deep ties between communities and their environments. However, rural education policies and practices often neglect these unique characteristics, adopting urban-centric models that prioritize standardized content and uniform assessment criteria (Lin et al., 2024). As a result, students often view English as an abstract subject unrelated to their daily lives, and this absence of place-based instruction in rural English classrooms has led to a series of educational problems, including low student engagement and motivation, weak language retention, limited communicative competence, and growing resistance toward English learning (Cao and Lu, 2023; Zhang, 2022; Liu, 2023; Guo, 2022). English teachers also face difficulties in sustaining motivation and designing relevant instructional materials, resulting in pedagogical stagnation and professional burnout (Li, 2017; Xue, 2018; Guo, 2022). This situation not only limits the effectiveness of English education but also undermines its potential to serve as a medium for promoting local culture and fostering pride in community heritage (Cai, 2024).

While theoretical discussions on PBE in rural contexts have gained momentum, practical applications in English teaching remain underexplored. Existing research often highlights the importance of integrating local cultural elements into education but provides limited guidance on actionable strategies for implementation. Addressing this gap is critical, particularly in light of China’s rural revitalization strategy, which emphasizes education as a driver of community development and cultural sustainability (Ding et al., 2023b).

Besides, current research on PBE shows significant global differences in its application. Studies in the U.S. focus on quantitative and measurable outcomes, while research in Australia and New Zealand emphasizes humanistic values, particularly in indigenous communities (Wooltorton et al., 2020). In China, research primarily explores how place-based education can address disparities between urban and rural English education and how digitalization can connect educational resources across these areas. However, empirical studies on the place-based English teaching in China are still limited, with most research remaining at the theoretical level. This study seeks to explore the current state of PBE in rural English education in China, identifying barriers to its implementation, and proposing practical solutions.

Three research questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1: What is the current status of place-based English teaching in China’s rural schools?

RQ2: Whether there are challenges in implementing place-based English teaching? If any, what are the specific challenges and causes?

RQ3: What pathway can be proposed to integrate PBE into English teaching?

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical foundations of PBE

The researchers interpreted PBE as “They aim to break down the barriers of alienation between schools and their surroundings, bringing education back to and relying on the rich and diverse local resources” (Cao and Lu, 2023, p. 1). The core of this approach lied in closely aligning education with the learning and living contexts of rural children, striving to foster students in line with the authentic modernization of rural education. “The place-based reform of rural education aimed to develop local educational resources, bringing schools back to nature and ecology. This approach enabled students to integrate interconnected information, relate their learned knowledge and practical applications to the local environment, and establish a sustainable model for the development of rural schools” (Ding et al., 2023b, p. 22).

Traditional educational theories extensively discussed the close relationship between education and locality. According to Qin (2021) research, as early as 1987, Bowers introduced the academic concept of “place-based education,” advocating that school education should focus on the local economy, social culture, and ecological conditions. Dewey (1899) advocated for the integration of formal education with community life. He believed that if students are unable to draw on their out-of-school experiences in their learning, then the time spent in school was wasted. Moreover, if students cannot apply the knowledge they have acquired to their daily lives, education will become disconnected from the actual contexts of family and society, preventing students from gaining true understanding and interest in learning. Based on this view, place-based education should be closely aligned with students’ living environments, leveraging their experiences and local cultural resources for teaching. This approach transforms education from an isolated transfer of information into an integral part of students’ lives. Particularly in rural areas, this method can help students better understand knowledge and foster their cultural identity and social responsibility.

Finnish scholar Engeström (2015) contributed a new theoretical framework to place-based education, introducing a theory of expansive learning closely tied to local contexts. Through this theory, Engeström emphasized the connection between open learning and community, suggesting that such an educational approach not only enhanced student learning outcomes but also fostered sustainable cultural, social, and economic development within local communities.

Granit-Dgani (2021) identified four distinct dimensions of place-based education. The first dimension, “learning in place,” involved moving teaching and learning activities from the traditional classroom to an open space. For instance, the lesson plan might stay the same, but the location of the lesson changed. The second dimension, “study of the place,” involved examining the environment and the natural processes that occurred there while remaining within that specific setting. The third dimension, “learning from the place,” was based on the idea that the environment and its elements played a unique educational role for both teachers and students. The final dimension, “learning for the sake of the place,” focused on promoting change in the environment, utilizing the insights gained from the other three dimensions.

2.2 The context of PBE in rural English education in China

The development of rural compulsory education showed significant results. In 2017, rural teacher living subsidies were first extended to cover counties in concentrated and severely impoverished areas, with coverage rates for rural schools and teachers reaching 97.3 and 96.4%, respectively. After the implementation of the “Rural Teacher Support Program (2015–2020),” 84.8% of rural teachers expressed satisfaction. Additionally, the standardization of rural primary and secondary schools was notably successful, with all indicators meeting the required standards at rates above 83.0% (Wu and Qin, 2020).

However, from the perspective of balanced educational development, rural education still faced some concerns (Ding et al., 2023a). In terms of educational philosophy, many schools imitated urban schools, neglecting their own uniqueness and importance, which leaded to a convergence of educational goals, curriculum, textbooks, and teaching methods with those of urban schools. Besides, the activation of local educational resources was still “insufficient” (Wu and Zhang, 2020). The exploration and utilization of local educational resources were inadequate or used a single approach, resulting in rural education not aligning with the local production and life. As a result, the students were disconnected from their hometown, lacking recognition, love, and understanding of the land. This led to a situation where curriculum subjects, English teacher professional development, and teaching practices were highly dependent on an urban and off-site (as opposed to on-site) context (Chen, 2022; Li, 2000).

The policies intended to support rural English teachers’ professional development have largely failed to achieve their intended impact, caused by implementation challenges, limited local fiscal capacity, and insufficient inflow of high-quality social resources. Most English training programs overlook the distinctive features of rural education, preventing rural middle school English teachers from acquiring practical methods and models that are truly relevant to their local teaching contexts (Wu, 2019).

Due to limited funding in rural education, most rural English teachers receive only basic salaries, with inadequate benefits and financial incentives, which negatively affects their quality of life. In addition, in some rural areas, there is a lack of respect for English teachers and insufficient emphasis on English education, resulting in a weak sense of social recognition. This further undermines rural English teachers’ motivation for professional development (Wu, 2019).

2.3 Challenges to be faced of PBE in rural English education

In China’s rural English classrooms, PBE was critically needed due to a growing mismatch between the official curriculum and students’ local realities. Studies showed that students often perceive English as disconnected from their lives, rendering it abstract, inaccessible, and ultimately irrelevant (Zhang, 2022; Guo, 2022). The failure to contextualize English content resulted in low motivation, superficial learning, and a lack of identity construction through language (Chai and Li, 2024; Liu, 2023). Moreover, the absence of local cultural elements—such as festivals, customs, and rural practices—meant that English became a vehicle of a foreign culture (Chen, 2006) rather than a tool for self-expression and empowerment (Chai and Li, 2024; Li, 2017). On the instructional side, rural teachers were often constrained by inadequate training and limited access to pedagogical innovation (Xue, 2018; Zhao and Yang, 2025), making it difficult for them to adapt lessons to rural contexts. PBE, by rooting language learning in local narratives and lived experiences, offered a meaningful alternative that addresses both student engagement and teacher agency.

It was equally important to examine the practical consequences of its absence. At the student level, researchers documented low emotional engagement, limited participation, and difficulty in finding personal relevance in English learning (Zhang, 2022; Li, 2017). The result was what Liu (2023) described as a “non-ecological” classroom—dominated by rote learning and passive reception. From the English teacher’s perspective, this disconnect led to professional burnout (Guo, 2022), ineffective instructional design (Wang L. N., 2024), and lack of confidence in using innovative methods (Qin, 2024; Zhao and Yang, 2025). Furthermore, the lack of training in integrating local content into English lessons exacerbated the divide between curriculum goals and community needs (Tang, 2016; Chen, 2017). Without PBE, English remained a culturally distant, exam-driven subject, rather than a lived and relevant language experience.

In China, the theory of PBE faced challenges in adapting to local conditions due to issues arising from the development of rural schools and society which hindered the effective implementation of PBE (Cao and Lu, 2023). Currently, the characteristics of Chinese rural community were fading, leading to a lack a strong foundation and effective platform when carrying out PBE (Wu, 2023; Xiao and Xie, 2021). The issues of “de-ruralization” (Tian and Shi, 2024) and “cultural virtualization” in rural society were severe (Cao and Lu, 2023; Tian and Shi, 2024; Qiu et al., 2022). As a result, rural development fell into a passive situation, with the unique development needs of rural areas being neglected. Under the backdrop of urbanization, rural culture experienced “urban convergence,” and under the context of modernization, rural culture underwent “de-traditionalization” (Ding et al., 2022). As English teaching moved toward standardization and normalization, the content of English education increasingly detaches from the experiences of rural children and the local natural ecology, leading to the “displacement” of English teaching within rural community culture (Chen, 2022; Li, 2000).

The integration, interaction, and cooperation between rural schools and communities were essential conditions. However, as a support platform for rural schools, in addition to facing issues within rural areas themselves, there was currently a disconnection between rural schools and communities (Cao and Lu, 2023; Shen et al., 2024) such as the disconnection of rural schools from local educational goals and development methods, and the weakening of rural residents’ sense of belonging and responsibility. By focusing primarily on urban life-related content and lacking local information, the connection between the English classroom and the lived experiences of rural teachers and students was severed (Chen, 2006). As a result, the English classroom, which should have been vibrant and engaging, became dull and monotonous (Li, 2000).

Objectively, rural teachers were the central link in connecting rural schools and communities (Wang, 2018). However, the challenge of the attraction and retention of high-quality, highly skilled teachers hindered the implementation of PBE in rural schools in China (Li and Wu, 2023; Qiu et al., 2022). This was mainly due to the urban orientation of young teachers (Tian and Shi, 2024; Wu, 2019), the lack of awareness of place-based teaching (Shen et al., 2024) and emotional belonging (Tian and Shi, 2024), insufficient orientation training (Tong and Lin, 2025; Shen et al., 2024), lost identity recognition (Feng et al., 2024; Wu, 2019) and their inadequate capabilities or literacy about place-based English teaching method, cultural resource integration, information literacy(Chen, 2022; Feng et al., 2024; Xie, 2017; Wu, 2019). Due to constraints such as administrative structures and teacher supply, small-scale schools in remote rural areas still suffer from a severe shortage of qualified teachers with an English background and these teachers also struggle to find the time and energy to participate in training (Chen, 2022; Wang et al., 2021).

Relying on locally rooted, culturally specific school-based curricula became the preferred and important approach for PBE in rural schools (Ding et al., 2022; Tang and Wu, 2019). Even the development of school-based curricula faced many challenges, such as the minimal influence of local rural resources on the curriculum content, misalignment in the goal-setting of curriculum development, and unreasonable evaluation standards (Tian and Shi, 2024). The attention given to English learning by rural schools and families did not match its rightful status as a core subject. In rural schools, Chinese and mathematics are regarded as the primary subjects, while English is often treated as a secondary subject. For instance, in rural primary schools, the actual number of hours allocated to English classes often fell short of the national standards and was frequently reduced by the demands of core subjects like Chinese and mathematics (Zhai, 2016).

Building on the previous research, it was recognized that teaching was closely connected to students, and the revitalization of rural education was reliant on students. Existing research pointed out firstly, a crisis of identity, as rural youth became indifferent to and rejected rural culture, feeling detached from their land and seeking to escape rural society (Wang and Wu, 2019; Qiu et al., 2022) and secondly, a lack of recognition and care, as rural youth struggled to gain emotional support, rights, and value recognition from rural culture, schools, and society (Cai, 2024), and lacked motivation and interests for learning English and found it difficult to derive a sense of achievement from their English studies (Qin, 2019).

2.4 Mechanisms for enacting PBE in English education

PBE in rural education can be enacted through these mechanisms: evaluation mechanism, cultural and social integration mechanism, collaborative mechanism, interdisciplinary mechanism, and empowerment mechanism.

The evaluation mechanism centered on the use of quantitative metrics to assess the effectiveness of PBE, offering evidence-based insights into student outcomes and program impact especially in STEM subjects (Yemini et al., 2023). Based on questionnaires, along with interviews and observations, the framework of rural teachers’ digital literacy was constructed (Cui and Xu, 2024). Similarly, another study designed a questionnaire and interviewed different grade teachers about rural sentiment (Zhang and Cheng, 2021). Inquiry-based curricula improved science literacy through local animal labs (Ambrosino and Rivera, 2022), and community-driven environmental initiatives fostered energy conservation (Kermish-Allen et al., 2019).

The cultural and social integration mechanism positioned PBE as a tool to strengthen cultural identity, advance social equity, and raise socio-political awareness (Tang and Wu, 2019). In China, some studies highlighted the importance of local knowledge teaching in constructing teachers’ cultural identity, fostering cultural self-awareness, promoting cultural interaction, and driving cultural transformation to support identity building (Xiao and Xie, 2021). In Australia and New Zealand, PBE can strengthen Indigenous Australians’ connection to their land by resisting the “Colonial everyday” and promoting indigenous-led cultural practices (Wooltorton et al., 2020). Similarly, PBE could become a platform to challenge dominant traditional national-building narratives that marginalized diverse perspectives in history curricula (Halbert and Salter, 2019). It may improve academic outcomes and foster identity by contextualizing learning for rural students, bridging the achievement gap between urban and rural areas (Azano et al., 2014; Sobel, 2004; Smith, 2002). PBE raises socio-political awareness as seen in a climate change filmmaking project in Puerto Rico that explored the cultural and political dimensions of environmental issues (Leckey et al., 2021) and through integrating socio-political themes into place-based curricula can inspire critical engagement and agency (Halbert and Salter, 2019).

The collaborative mechanism emphasized sustained partnerships between schools, local stakeholders, and community organizations to co-create meaningful learning experiences grounded in place (Shen et al., 2024). Such partnerships ensured that students’ learning extended beyond the classroom to address real-world challenges. For instance, a collaboration between the community and local schools in Hawaii to develop an environmental curriculum fostered a sense of ecological stewardship among students (Ambrosino and Rivera, 2022). In Puerto Rico, a project was facilitated where high school students produced climate change films under the guidance of local mentors (Leckey et al., 2021). Salazar Jaramillo and Espejo Malagon (2019) focused on implementing place-based education to teach English to children in a rural school in Bogota, Colombia. They utilized the local environment and community as a foundation for teaching language arts and also encouraged students to write short poems in English, fostering a deeper connection to their rural surroundings and enhancing their engagement with the English language.

The interdisciplinary mechanism allowed PBE to transcend traditional subject boundaries by integrating science, arts, and language education, thereby fostering holistic and connected learning experiences. Out-of-school learning programs in Hungarian primary schools blended local ecological studies with historical narratives to foster interdisciplinary understanding (Fűz, 2018), while local landscapes and community stories were used to inspire English writing in rural Colombia., linking language learning to their immediate environment and enhancing engagement.

The empowerment mechanism focused on equipping rural teachers and reconnecting students with their local culture through place-based strategies. In response to the rural revitalization agenda, teachers are increasingly expected to serve as “New Able Villagers” (Tong and Lin, 2025; Wang et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2024), bridging educational practices with community development goals. Some paths focused on teaching ability structure and cultivation of the “Country Attribute” (Xiao and Wang, 2020), digital literacy (Cui and Xu, 2024; Jiang, 2025) and training (Lin et al., 2024) for teachers. Specifically, it found that place-based curriculum, place-based teacher development, and place-based teaching practices were necessary to shift English situational teaching from an off-site to an on-site context (Chen, 2022; Li, 2000). In response to the issue of teacher retention, the generating mechanism of educational sentiment and the “three-dimensional structure” approach have been proposed (Liu and Li, 2024), while other scholars provided suggestions from the perspectives of institutional design, educational training, and social support (Zhang and Cheng, 2021). To address rural students’ cultural disconnection, revitalizing cultural life, improving localized materials, and creating dynamic school-based curricula were proposed (Cai, 2024; Ai et al., 2024). Similarly, curriculum development was emphasized through clear objectives, stakeholder empowerment, and resource alignment (Tian and Shi, 2024; Ai et al., 2024), and “Internet + Place-based-Classroom” was an effective strategy to improve incomplete subjects, insufficient class hours and low-quality teaching (Wang et al., 2020).

While PBE has been widely recognized for its potential, empirical research on its implementation remains limited, particularly in the context of rural English teaching. English is chosen as the focal subject in this study not only because of its core status in national curricula, but also due to its cultural and linguistic distance from rural students’ everyday lives. Unlike science or mathematics, which can be more easily contextualized through local observations or practical tasks, English instruction in rural areas often relies on standardized textbooks rooted in urban or Western cultural contexts. Without practical models or context-sensitive evidence, teachers are often uncertain about how to meaningfully integrate local cultural content into English instruction. Second, most domestic studies examined the challenges faced by PBE in rural education as a whole or STEM or social science subjects, lacking a more focused perspective on the specific issues in the PBE of English teaching and leaving language education largely underrepresented. Third, most paths were general, with only a few studies proposing specific paths for particular subjects. This study addressed these gaps by exploring current status, challenges and path of place-based English teaching in China’s rural schools.

3 Methodology

3.1 Participants

Convenience sampling was adopted in the study to recruit the participants. A total of 234 students and 204 English teachers at rural junior high schools in the southern regions of China, including Anhui, Hubei, Fujian, Jiangxi, Jiangsu, participated in this study. The selected schools were public institutions with a 3-year system, and the students came from rural families. The sample of students aged 12–15 comprised approximately 53% male (n = 123) and 47% female (n = 111). There were 61 students in the first grade, 90 students in the second grade, and 83 students in the third grade. In addition, the sample comprised approximately 52% male (n = 107) and 48% female (n = 97) teachers. The average teaching experience was 6.35 years (SD = 4.38).

The 10 students participating in the interviews came from five cities, with four females and 6 males. The average age was 13.6 (SD = 1.02). The 5 English teachers (2 females, 3 males) were from different cities, with the average teaching experience of 5.8 years (SD = 0.75).

3.2 Instruments

3.2.1 Questionnaire

The questionnaire was self-developed and rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (see Supplementary Appendix A). To reduce the participants’ cognitive load in responding to the questionnaire, the questionnaire was translated from English to Chinese. The preliminary Chinese version of the scale was evaluated by three master candidates and one associate professor in English education in terms of the clarity and appropriateness as well as the English-Chinese equivalence.

Students’ questionnaire comprised 25 statements and four subscales that taped into different aspects of place-based English teaching, including current status (item 1–5), challenges (item 6–10), causes (item 11–17), and measures (item 18–25). The scale revealed a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.851 and a value of 0.899 for KMO, with a significance level of 0.001. A sample item was “I believe that both learning local cultural knowledge and learning English are important.”

Teachers’ questionnaire comprised 28 statements that assessed four components: current status (item 1–6), challenges (item 7–17), causes (item 18–23), and measures (item 24–28). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.892, and the KMO value was 0.839, with a significance level of 0.001. One sample item read: “I have adopted various methods and strategies to carry out place-based teaching.”

3.2.2 Interview

This study utilized semi-structure interviews to further explore students’ and teachers’ attitudes and perceptions on the current status, challenges, causes, and measures of PBE in English teaching (see Supplementary Appendix B). The interview protocol was developed and refined by two researchers, culminating in two distinct versions: one for students (comprising 7 questions) and one for teachers (comprising 7 questions). The interview was conducted online and recorded, with each interview lasting approximately 30 min.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The study first obtained consent from the students and teachers, then distributed the questionnaires to them. A total of 234 student questionnaires and 202 teacher questionnaires were collected. The data was analyzed by using SPSS 26.0 to calculate the mean and standard deviation.

The online interviews were conducted with 10 junior high school students and 5 junior high school English teachers from rural schools. With the consent of the interviewees, the interview was recorded and transcribed by using NVivo. In the process of analyzing interview data, the initial step involved importing the transcribed interview texts into the project file. Afterward, nodes were created according to the research questions and interview framework (e.g., Learning Methods, Teaching Issues, Cultural Integration, Cultural Expression, Integration of Culture and English, Hometown Cultural Awareness, Self-Identity, Textbooks, Identity Recognition, Local Responsibility, Teaching Approaches, etc.). Each interview transcript was carefully reviewed to identify text segments that aligned with the established nodes, and these segments were coded under the appropriate nodes.

4 Results

4.1 Limited Integration between PBE and English teaching and learning

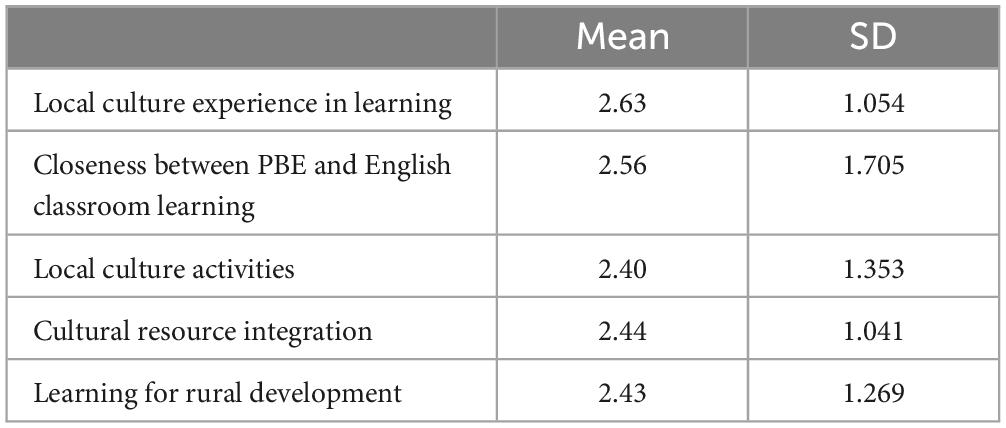

The data presented in Table 1 suggests that the implementation of PBE is not yielding particularly favorable outcomes from the students’ perspective. The mean of “Experiencing local culture in the classroom” is 2.63, indicating that even the most positively perceived aspect of the statement leaves much to be desired. The mean score of 2.56 for “Closeness between PBE and English classroom learning” further emphasizes that students do not view PBE as being strongly integrated into their classroom experiences. The other indicators reflect an even weaker perception of PBE’s implementation. Specifically, the mean score of 2.40 for “Local culture activities” suggests that students perceive a minimal inclusion of local cultural elements in learning activities. Similarly, the integration of local cultural resources (mean = 2.44) and development themes (m = 2.43) is also perceived as insufficient.

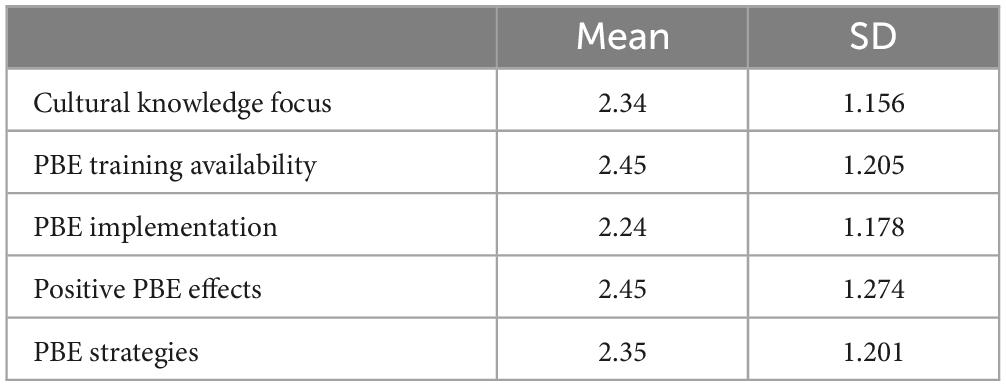

The data in Table 2 highlights teachers’ perceptions of the implementation of place-based education, revealing several concerning trends. The mean scores across indicators are relatively low, suggesting that teachers perceive the integration of PBE into their curriculum as limited. The mean for “The English lessons focus on teaching local cultural knowledge” is only 2.34, indicating that the emphasis on local culture in English teaching is scarce. The mean score for “PBE has already been implemented in schools” is 2.24 and the “positive PBE effects” is 2.45, reflecting a perception that PBE has not been widely or effectively implemented. In terms of the teachers themselves, they are not provided with available opportunities for understanding PBE (mean = 2.45), such as attending training, and are not actively adopting corresponding teaching strategies (mean = 2.35).

4.2 Challenges and causes from students and teachers

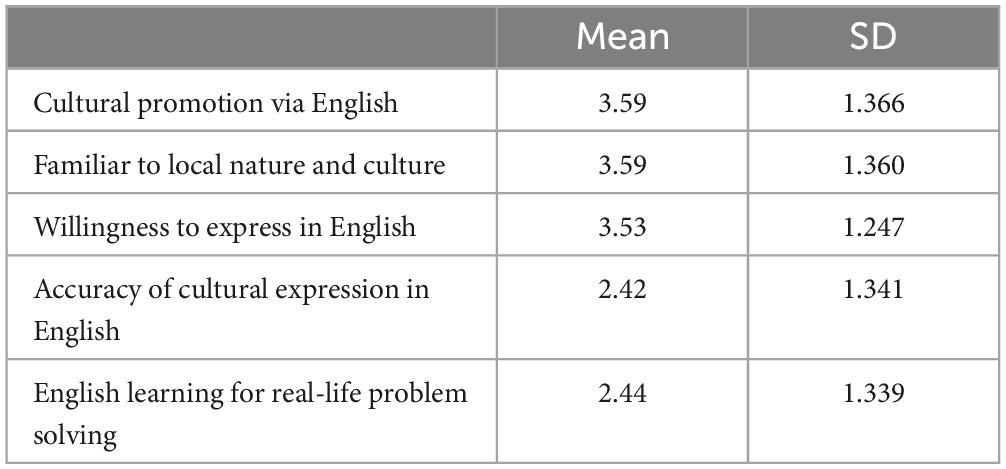

In Table 3 shows the highest mean scores are “Local culture is promoted through English as a medium” (mean = 3.59) and “familiar to the local nature and culture” (mean = 3.59). This suggests that students feel relatively confident in recognizing and promoting local culture and understanding their hometown’s natural and cultural characteristics through English.

However, challenges are evident in other aspects. “Accuracy of cultural expression in English” and “English learning for real-life problems solving” suggest significant difficulties for students.

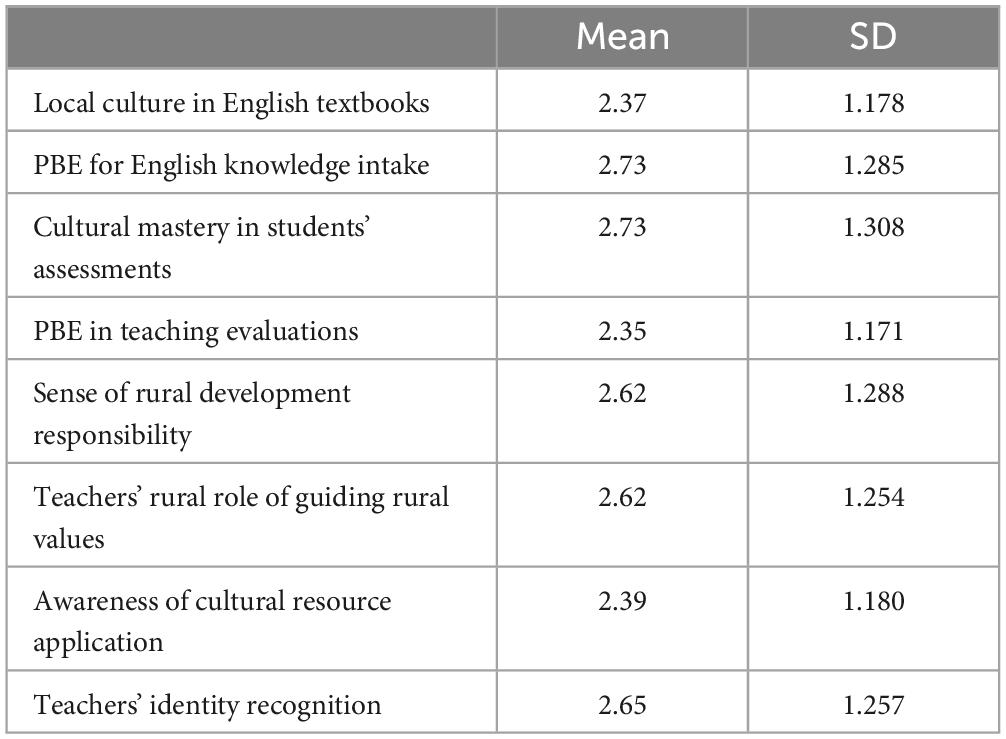

The data in Table 4 highlights significant obstacles in the implementation of place-based education from the perspective of teachers. The incorporation of local culture into English textbooks (mean = 2.37) and evaluation criteria (mean = 2.35) are particularly insufficient whereas it is still worth noticing the issues about “Place-based education facilitates the intake of English knowledge” (mean = 2.73), “Incorporate mastery of local culture into student assessments” (mean = 2.73), teachers’ sense of rural responsibility (mean = 2.62), sense of professional roles (mean = 2.62), awareness of culture-English integration (mean = 2.39), and identity recognition (mean = 2.65).

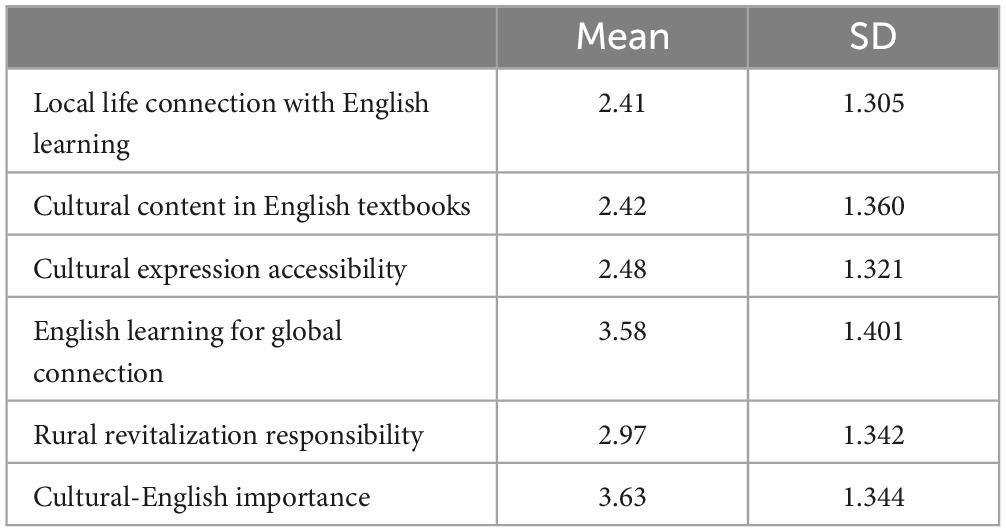

Table 5 presents that there is a clear disconnect between the English curriculum and local life, as students feel that the knowledge they acquire in English class lacks relevance to their local context (mean = 2.41). Additionally, they perceive the integration of local culture into English textbooks (mean = 2.42) and the accessibility of expressing local culture in English as inadequate (mean = 2.48). The sense of responsibility (mean = 2.97) does not appear to be fully ingrained or strongly emphasized within their educational experience.

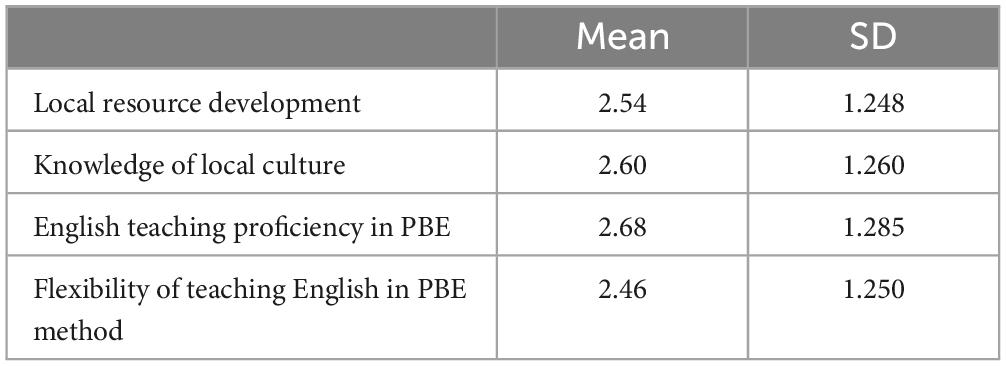

As seen in Table 6, Teachers express only moderate willingness to develop place-based teaching resources (mean = 2.54) and to use various methods and strategies for localized teaching (mean = 2.46), indicating potential reluctance or lack of confidence in fully embracing PBE approaches. Additionally, their self-assessed knowledge of local culture (mean = 2.60) and teaching proficiency (mean = 2.68) suggests that while they possess some level of capability, it may not be sufficient to effectively implement PBE in English teaching.

4.3 Essential measures for advancing place-based English Education in rural areas

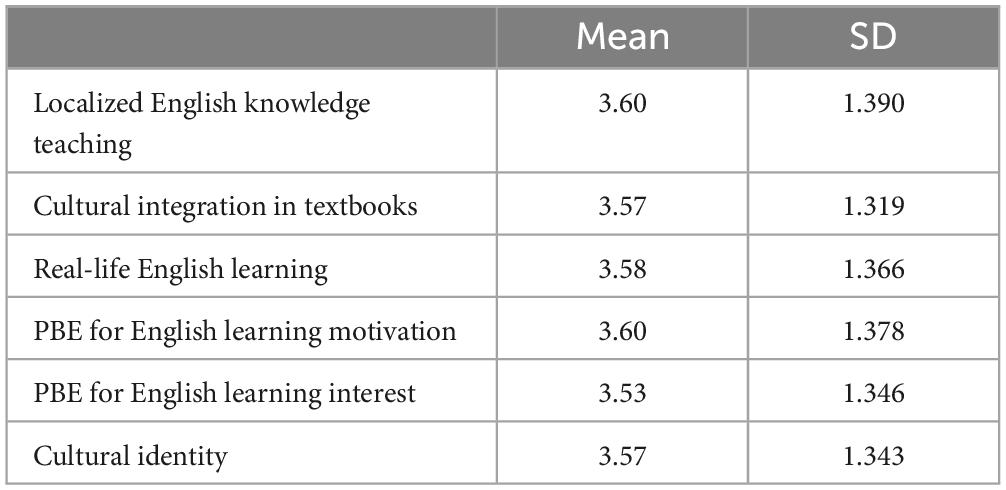

In Table 7, the highest mean score is associated with both “Teaching localized English knowledge” (mean = 3.60) and “Learning local culture enhances motivation to learn” (mean = 3.60), indicating that students strongly believe that connecting English education with local knowledge and culture is essential for improving their motivation. Similarly, “Learning English in a real-life environment” (mean = 3.58) and “Integrate local cultural knowledge into English textbooks” (mean = 3.57) also reveal high mean scores, reflecting students’ recognition of the importance of practical and culturally relevant learning experiences.

Furthermore, the measures “Learning local culture stimulates interest in English learning” and “Learning about local culture fosters a sense of cultural identity” both have mean scores of 3.53 and 3.57, respectively, suggesting that students feel a strong connection between local culture and their overall interest and pride for their community.

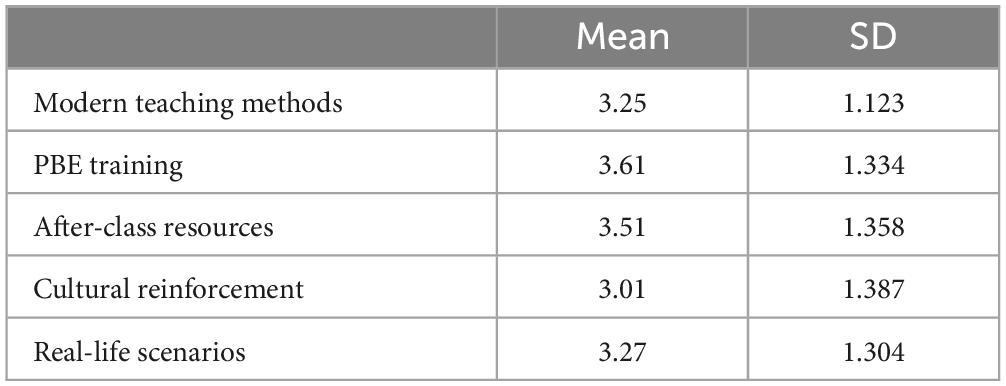

Table 8 presents that the highest mean score is “Place-based education training and professional development” (mean = 3.61), indicating that teachers strongly believe that receiving specialized training and professional development is crucial for effectively implementing PBE. This is closely followed by “Provide students with after-class learning resources” which has a mean score of 3.51, suggesting that teachers see value in extending English learning opportunities beyond the classroom through additional resources related to PBE.

“Utilize modern teaching methods” (mean = 3.25) and “Create real-life learning scenarios” (mean = 3.27) also reveal relatively high mean scores. These scores reflect teachers’ recognition of the importance of integrating modern pedagogical techniques and real-world applications to make English education more relevant and engaging for students. However, the lower mean score of 3.01 for “Reinforce local cultural knowledge after English class” suggests that while teachers attach importance to connecting local culture to English learning, they may struggle with or put less emphasis on immediate reinforcement of the knowledge outside of regular class time.

4.4 Results of the interview

Interpreting the interview data provides a strong warrant for the claims in questionnaire results. First, regarding the reasons behind the limited implementation of PBE in English teaching, it attributes to exam-oriented focus, as S1 mentioned: “Teacher probably thinks that since it won’t be on the exam, there’s no need to cover it,” time constraints, as T2 said “Since a class lasts for only forty minutes, it is impossible to cover all the theoretical knowledge within that time. Not to mention the knowledge related to localization.” And inadequate ability of innovation, as T5 said “I’m rather conservative.” and T4 mentioned: “I can’t come up with new ideas. I don’t even know how to combine the local culture and English teaching in an effective way.”

Secondly, interviews reveal that schools focus on exam scores or enrollment rate, leading to a very rigid approach to English teaching which is difficult to make a new change and not all the teachers possess standard pronunciation in both Mandarin and English, making it difficult for students to understand when integrating some terminological cultural expressions. Nevertheless, some respondents attribute the challenges to the English-speaking environment, mismatched English level of students, low interest, brain drain of top students and bias of English. T1 mentioned, “I think it’s more about the lack of an English-speaking environment which results in poor situation of PBE in English teaching.” T2 pointed out that “The level of English teaching in primary schools is relatively low, making it difficult to align with middle school English teaching. On the other hand, students’ interest in learning English is not strong.” T3 said, “One reason is that in recent years, many parents have transferred their children to cities, believing that the quality of education in cities is better than in rural areas.” “I want to learn better English, but there’s no one to practice with,” S4 said. “Additionally, some students have a limited understanding and believe that learning English is useless,” T3 added.

Moreover, for place-based English teaching, the first step is to develop textbooks with local characteristics. As S1 mentioned: “Incorporating local culture would likely make the content more interesting and relatable to our daily lives.” S2 expressed: “The current textbooks are quite basic and somewhat boring. Incorporating local culture could improve this situation, as students are likely more familiar with local cultural elements.” S1 also noted that this approach would allow students to learn more about their hometown in the classroom. This could foster a greater appreciation for their hometown. Second, conduct place-based education training for teachers. Three teachers mentioned that it is essential to promote the concept and methods of PBE in rural schools because the critical step to implementing is ensuring that teachers truly understand what it entails. This training will enable them to consciously integrate localized elements into English teaching. Third, change the perception that English is useless and encourage students to contribute to rural revitalization. Students believe that PBE can make English increasingly indispensable in real life. T3 mentioned, “It’s important to change students’ perceptions by frequently discussing the wide-ranging practical uses of English in real life” Besides, improvement of the quality of rural English teaching is concerned by educators and learners. “If the quality of English teaching in rural areas is not improved promptly, these children will continue to be at a disadvantage in college entrance exams and future employment.” Pointed by a teacher, “Educational equity should not remain just a slogan.”

4.5 “Dual-Core” pathway for place-based education

Given the persistent challenges faced in rural English education, the need for a more context-responsive framework is evident. The “Dual-Core” pathway holds particular significance in the context of rural education. It goes beyond conventional, standardized, one-size-fits-all models by anchoring English teaching in students’ local culture, geography, and lived experiences.

4.5.1 “Dual-Core” pathway (first core)

The first core is building an English place-based education team which emphasizes the optimization of decision-making, the integration of resources, and the improvement of evaluation mechanisms.

Optimizing decision-making processes is the start point that involves electing and inviting multiple stakeholders to establish a clear plan for the development of PBE of English. They should be insightful and familiar with English teaching, local development or PBE practice; therefore, their concerns and feedback can be effectively integrated into the decision-making.

To integrate resources, building a “Place-based English Teaching Resource Bank” is the next critical action that collects Chinese and English versions of local resources such as rural cultural forms and characteristics, issues of rural sustainability, rural geography, and local customs, etc. This Resource Bank would serve as a digital repository of English teaching materials, providing valuable support for curriculum design. The pathway also promotes the “1 + 1” English teaching model that focuses on foundational English knowledge while cultivating the ability of students and teachers to solve local contextual problems based on that knowledge. These are direct responses to the disconnect between textbooks, curriculum content and local culture, and enhances students’ ability to apply English to real-life situations.

Thirdly, improve the evaluation mechanism by incorporating teachers, students and their, parents, and community members into the teacher’s evaluation indicators to solve the problem of identifying the effects of place-based teaching. Synthesizing the multi-stakeholder evaluation allows that necessary adjustments can be made to better meet the needs of PBE.

4.5.2 “Dual-Core” pathway (second core)

Promoting place-based teaching with a focus on enhancing the “place” awareness of both teachers and students in terms of “Three Strengthening.” There are some regular training for teachers in PBE.

Strengthening belief confronts the teacher’s unawareness of PBE in English teaching. It refers to the ideological education project so that rural teachers could recognize that all effective educational philosophies must be “place-based”, with English teaching, in particular, needing to be grounded in the local context; the English teaching syllabus and methods should align with PBE principles; English teachers should deeply root themselves in place-based education by fully understanding the local learning environment, fostering a deep affection for the local context, and wholeheartedly dedicating themselves to the development of local education.

Strengthening preparation confronts issues of teachers’ insufficient knowledge storage, sense of responsibility and mission, and identity, and teaching capacity. First, local knowledge preparation focuses on fully utilizing the educational resources available in place-based education by means of field visits, interviewing with the local reading literature, etc. Second, emotional preparation emphasizes fostering a strong sense of responsibility to the local community through diverse PBE learning activities, participating in rural affairs and PBE-related teaching competition, organizing school-community academic activities and setting up some rewards to encourage students to develop a deep love for their homeland and a sense of responsibility toward it. Finally, teaching method preparation involves carefully adjusting English teaching methods, including pre-class preparation, in-class execution, and post-class exercises, to align with the principles of place-based education.

Strengthening the school-based curriculum prepares the students to be a teenager with a sense of cultural identity and recognition from the rural community. First, the curriculum model should be designed to integrate the school’s natural and ecological surroundings that are quite familiar to the students, with a focus on real-life contexts to create distinctive, locally-rooted English courses. Second, the curriculum content should be closely connected to the students’ own experiences and the unique cultural heritage of their local area, utilizing educationally valuable local resources to actively incorporate history, culture, natural environments, and social development into the English teaching materials, gradually forming a teaching textbook with rural characteristics. Finally, the curriculum philosophy should encourage students to return to their hometowns, contribute to the development of rural areas, and actively participate in rural revitalization, thereby fostering both personal growth and community development.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study reveal significant challenges in implementing PBE in rural English teaching in China, including the insufficient integration of local cultural elements into teaching, the detachment of English learning from rural realities, and the limited professional training for teachers to engage with PBE, etc. These challenges align with existing literature, which emphasizes the gap between theoretical discussions on PBE and its practical application in diverse contexts (Tian and Shi, 2024; Wooltorton et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2024; Feng et al., 2024; Chen, 2022; Li and Wu, 2023; Qiu et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2023a).

One notable issue is the disconnect between English education and local life, as highlighted by both students and teachers. The absence of localized content in textbooks and limits incorporation of real-world rural scenarios into classroom practices result in low engagement and reduced motivation among students. This aligns with observations researchers who pointed out that rural education often fails to connect with students’ lived experiences, thereby limiting their ability to see the relevance of their learning to their communities (Cao and Lu, 2023; Tian and Shi, 2024; Qiu et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2022).

For solutions, the research suggests that efforts can be made to develop English textbooks with local characteristics, create “place-based” teaching contexts, integrate local knowledge into English classrooms, stimulate students’ interest and motivation in learning, enhance teachers’ and students’ sense of local responsibility and sense of identity, conduct “place-based” teacher training, strengthen cultural recognition for local culture, adjust teaching methods, and enrich localized teaching resources. Based on the problem-solution results, this paper offer the “Dual-Core” pathway for place-based English education including two main cores. The first core, focused on decision-making, resource integration and evaluation mechanisms, including involving stakeholders to align educational strategies with local needs, creating a comprehensive resource system that incorporates rural cultural elements, and establishing the “Resource Bank” and “1 + 1” model to strengthen collaboration between schools and communities. It aligns with the findings which advocate for stakeholder collaboration, stakeholder empowerment, and resource alignment, evaluation criteria (Halbert and Salter, 2019; Tian and Shi, 2024; Ai et al., 2024).

The second core, centered on enhancing teachers’ and students’ “place” awareness (Lin et al., 2024; Xiao and Wang, 2020; Cui and Xu, 2024; Lin et al., 2024; Chen, 2022), resonates with the insights of Sobel (2004), emphasizing the importance of connecting classroom learning with the community. Similar gaps in teacher preparedness have been noted by Lin et al. (2024), who advocate for localized and diverse professional development programs.

Strengthening beliefs is similar to the findings of Wu and Zhang (2020), which suggest that place-based education requires the cultivation of a belief in the philosophy of place-based education, the enhancement of teachers’ and community members’ identification with the concept, the innovation of pathways and methods for implementing place-based education in rural schools, and the achievement of rural students’ core competency development and emotional and attitudinal alignment. In terms of strengthening preparation, Lin et al. (2024) also recommended incorporating localized and varied training content, including local cultural resources and the development of research skills. It aligns research on rural education emphasizing empowering teachers which demanded rural teachers to take on the role of “New Able Villagers” (Shen et al., 2024; Tong and Lin, 2025; Wang et al., 2022; Xiao and Wang, 2020). In terms of strengthening the curriculum, Halbert and Salter (2019) and Leckey et al. (2021) show how connecting students with their communities can raise awareness and inspire action on socio-cultural and environmental concerns. Fűz (2018) highlights the incorporation of local, real-world experiences into the curriculum to enhance student learning through place-based education. It is similar to the findings that propose several practical strategies, including the development of curriculum objectives, the empowerment of those involved in curriculum creation, the provision of curriculum resources, and the execution of curriculum evaluation (Tian and Shi, 2024).

A distinction of this study is the formulation of a theoretically grounded yet practically oriented “Dual-Core” framework, which advances the discourse on rural English education by addressing dimensions largely neglected in existing literature. Prior studies that predominantly focus on pedagogical methods or policy design in isolation, but this framework systematically incorporates the concrete and actionable method of Chinese and English culture resource integration as a central component, a perspective rarely explored in current research. Furthermore, it adopts a multi-agent perspective by simultaneously attending to the interrelated needs of place-based education teams, teachers, and students. This approach not only enhances internal coherence within educational practices but also reinforces contextual adaptability, thereby offering a more sustainable and scalable model for implementing place-based English education in rural settings.

6 Conclusion

The implementation of PBE in rural English teaching presents both significant challenges and promising opportunities. This study highlights obstacles, such as the insufficient integration of local knowledge into English teaching, a disconnect between English education and rural contexts, and the lack of localized evaluation standards. Teachers and students often face barriers in utilizing local resources and fostering a strong sense of cultural identity and responsibility.

Despite these challenges, the study identifies pathways to address these gaps. The proposed “Dual-Core” approach emphasizes building localized educational teams to align teaching strategies with community needs and enhancing awareness of local culture among teachers and students. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research is confined to a specific geographic and cultural setting and its scope includes rural junior high schools in the southern regions of China which may limit the generalizability of its findings. Additionally, the relatively small sample size restricts the statistical power and representativeness of the results. These factors highlight the need for broader, multi-regional studies to validate and expand upon the findings presented.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the China University of Petroleum Beijing. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LM: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the China’s Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Science Foundation (under Research on Second Language Learning Emotion Regulation and Intervention under the Influence of Generative Artificial Intelligence) funding (grant number 24YJC740060) and Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing (grant numbers 2462023YXZZ002, ZX20230108, and 2462025Q2DX002).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1580324/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

S, Student; T, Teacher.

References

Ai, L., Luo, Q. J., and Wang, X. H. (2024). Exploring the practice model on place-based education of small-scale rural schools: Analysis of F elementary school by grounded theory. Educ. Teach. Res. 38, 40–55. doi: 10.13627/j.cnki.cdjy.20241028.001

Ambrosino, C. M., and Rivera, M. A. J. (2022). Using ethological techniques and place-based pedagogy to develop science literacy in Hawai‘i’s high school students. J. Biol. Educ. 56, 3–13. doi: 10.1080/00219266.2020.1739118

Azano, A. P., Callahan, C. M., Missett, T. C., and Brunner, M. (2014). Understanding the experiences of gifted education teachers and fidelity of implementation in rural schools. J. Adv. Acad. 25, 88–100. doi: 10.1177/1932202X14524405

Cai, W. Y. (2024). The “Detachment from the land” dilemma in the growth of rural youth and its resolution: Reflections on rural localized education from escape to inheritance. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 45, 71–76.

Cao, R. P., and Lu, S. Y. (2023). Value, challenges and countermeasures of localized education in rural schools in China. Teach. Admin. 40, 1–7.

Chai, H., and Li, Z. T. (2024). The Practical problems and countermeasures of integrating Chinese excellent traditional culture into middle school English teaching. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 45, 86–87.

Chen, B. (2006). The content and implementation paths of cultural background education in middle school English teaching. Teach. Admin. 23, 47–49.

Chen, D. M. (2017). A survey on the current status of English teachers’ pronunciation skills in rural primary schools in Guizhou province and training strategies. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 38, 187–189.

Chen, Y. Y. (2022). Spatial shift from off-site to on-site reflections: On practice crisis of English situational teaching in rural primary schools in the new era. Res. Teach. 45, 86–92.

Cui, Y. J., and Xu, L. (2024). The actual state of rural teachers’ digital literacy in localized educational space and breakthrough strategies. e-Educ. Res. 45, 105–111. doi: 10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2024.08.014

Dewey, J. (1899). The school and society: Being three lectures. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ding, X. S., Wu, Z. H., and Xiao, B. S. (2022). The problems, values and practical choices of localized curriculum construction in rural schools. China Educ. Technol. 43, 59–65+74.

Ding, X. S., Wu, Z. H., and Xiao, B. S. (2023b). The implications and paths of the transformation of rural education in localization. Theory Pract. Educ. 43, 22–27.

Ding, X. S., Wu, Z. H., Fan, J. Y., and Yang, J. T. (2023a). The lack and construction of rural principals’ leadership in localized education. Educ. Sci. Res. 34, 5–12.

Feng, L., Niu, J. Z., and Yu, H. B. (2024). The transformation of rural teachers’ identity and the reconstruction of their literacy structure from the perspective of localization. Theory Pract. Educ. 44, 44–49.

Fűz, N. (2018). Out-of-school learning in Hungarian primary education: Practice and barriers. J. Exp. Educ. 41, 277–294. doi: 10.1177/1053825918758342

Guo, X. H. (2022). A narrative study on the job burnout of an English teacher in a rural primary school. Educ. Res. Monthly 39, 63–69. doi: 10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2022.08.009

Halbert, K., and Salter, P. (2019). Decentring the ‘places’ of citizens in national curriculum: The Australian history curriculum. Curriculum J. 30, 8–23. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2019.1587711

Jiang, C. (2025). Research on the path of improving the digital competence of middle school English teachers. Foreign Lang. Res. 2, 72–76. doi: 10.16263/j.cnki.23-1071/h.2025.02.009

Kermish-Allen, R., Peterman, K., and Bevc, C. (2019). The utility of citizen science projects in K-5 schools: Measures of community engagement and student impacts. Cultural Stud. Sci. Educ. 14, 627–641. doi: 10.1007/s11422-017-9830-4

Leckey, E. H., Littrell, M. K., Okochi, C., González-Bascó, I., Gold, A., and Rosales-Collins, S. (2021). Exploring local environmental change through filmmaking: The lentes en cambio climático program. J. Environ. Educ. 52, 207–222. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2021.1949570

Li, G. (2017). A study on the design of student activities in rural primary English classes. Teach. Admin. 34, 51–53.

Li, W., and Wu, Z. H. (2023). The place-based transformation of rural teacher education in part of foreign countries. Int. Comp. Educ. 45, 22–31. doi: 10.20013/j.cnki.ICE.2023.03.03

Li, Z. H. (2000). A discussion on the curriculum design of the new high school English textbooks. Teach. Admin. 17, 47–49.

Lin, H. F., Chu, H., and Xu, F. (2024). How “Localize” shaping the learning ability of outstanding rural teachers. Teacher Educ. Res. 36, 100–106. doi: 10.13445/j.cnki.t.e.r.2024.03.008

Liu, W. H., and Li, Q. (2024). The generating mechanism and realistic path of rural teacher’s education sentiment from a localization perspective. Educ. Sci. 40, 75–81.

Liu, Y. P. (2023). The dilemma and breakthrough of rural primary English teaching from the perspective of educational ecology. Educ. Sci. Forum 37, 5–11.

Qin, L. Y. (2019). Exploration of English classroom teaching reform in rural middle schools. Theory Pract. Innov. Entrepreneurship 2, 33–34.

Qin, M. (2024). Research on strategies for cultivating the abilities of English teachers in rural primary schools. Theory Pract. Innov. Entrepreneurship 7, 85–87.

Qin, Y. Y. (2021). The modernization of rural education from the perspective of rural revitalization: The crisis and the reconstruction of self-confidence. Educ. Res. 43, 138–148.

Qiu, D. F., Wang, Z. Y., and Yu, Z. Y. (2022). The development challenges and breakthroughs of rural education in China from the perspective of place-based education. Educ. Sci. Forum 36, 70–76.

Salazar Jaramillo, P., and Espejo Malagon, Y. (2019). Teaching EFL in a rural context through place-based education: Expressing our place experiences through short poems. Eur. J. f Sustainable Dev. 8, 73–84. doi: 10.14207/ejsd.2019.v8n3p73

Shen, X. Y., Wang, G. M., and Bi, Y. (2024). A research on the concept and practice of “Place-based” rural teacher training. J. Comp. Educ. 5, 127–139.

Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi Delta Kappan 83, 584–594. doi: 10.1177/003172170208300806

Sobel, D. (2004). Place-based education: Connecting classrooms and communities. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society.

Tang, D. D. (2016). Analysis of the construction of English teaching staff in rural middle schools: Taking rural middle schools in county X as an example. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 37, 161–164.

Tang, Y., and Wu, Z. H. (2019). An analysis of the indigenized path of rural education reform. Theory Pract. Educ. 39, 16–19.

Tian, Y. Y., and Shi, L. (2024). The realistic dilemma and path alternatives of the rural school curriculum construction under the perspective of place-based theory. Modern Educ. Manag. 44, 51–60. doi: 10.16697/j.1674-5485.2024.06.006

Tong, R. G., and Lin, L. S. (2025). Exploration on the construction of high-quality education system of rural teachers from the perspective of localization. Educ. Exp. 45, 14–21.

Wang, H., and Wu, Z. H. (2019). Place-based education transforms the rural educational ecology in part of foreign countries. Int. Comp. Educ. 41, 98–105. doi: 10.20013/j.cnki.ice.2019.09.013

Wang, J. X., Tian, J., Wang, X., and Wei, Y. T. (2020). Research on optimization countermeasures of “Internet + Localized-Classroom” based on the analysis of teaching behavior data. e-Educ. Res. 41, 93–101. doi: 10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2020.04.013

Wang, L. N. (2024). Exploring the path of excellent development for rural backbone teachers: A case study of a rural English teacher. Teacher Educ. Forum 38, 17–19.

Wang, M. J. (2018). Place-based teaching: A powerful lever to transform education for ecological civilization. J. World Educ. 31, 13–16+24.

Wang, S., Liu, S. H., and Fang, T. T. (2021). Demand structure prediction and construction planning of rural teachers for 2035. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 41, 1–7.

Wang, W. T. (2024). Practical research of problem-based learning model in middle school English teaching. Curriculum Teach. Mater. Method 44, 128–133. doi: 10.19877/j.cnki.kcjcjf.2024.11.019

Wang, Z. Y., Zhu, N. B., and Li, S. F. (2022). “New Able Villagers”: The restoration and shaping of rural teachers’ public identity. Theory Pract. Educ. 42, 36–40.

Wooltorton, S., Collard, L., Horwitz, P., Poelina, A., and Palmer, D. (2020). Sharing a place-based indigenous methodology and learnings. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 917–934. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2020.1773407

Wu, F. (2019). The actual and ideal situation of professional development of English teachers in rural middle schools. Teach. Admin. 38, 64–67.

Wu, Z. H. (2023). Three key points for promoting the revitalization of rural education. Manag. Prim. Sec. Sch. 37:1.

Wu, Z. H., and Qin, Y. Y. (2020). The report of rural education development in China 2019. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Publishing Group.

Wu, Z. H., and Zhang, P. (2020). The place-based education leadership of rural principals: Why and How. Educ. Res. 42, 126–134.

Xiao, D. Z., and Xie, J. (2021). Cultural identity construction of rural “Insiders” of the new generation of rural teachers: Based on the perspective of local knowledge teaching. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 42, 87–92.

Xiao, Z. D., and Wang, Z. Y. (2020). Teaching ability structure and cultivation path of the “Country Attribute” of general teachers in rural primary schools. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 41, 64–69.

Xie, H. Q. (2017). Improvement of information literacy among English teachers in rural secondary schools. Teach. Admin. 34, 65–67.

Xue, Y. Y. (2018). Survey and analysis of rural English teachers’ professional development in the “Internet Plus” era. J. Higher Educ. 3, 63–65. doi: 10.19980/j.cn23-1593/g4.2018.03.022

Yemini, M., Engel, L., and Ben Simon, A. (2023). Place-based education - A systematic review of literature. Educ. Rev. 77, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2023.2177260

Zhai, H. Y. (2016). An analysis of the current situation of rural primary English course offering in remote mountainous areas. Basic Foreign Lang. Educ. 18, 50–55+108.

Zhang, L. P., and Cheng, J. J. (2021). Study on the implication and cultivation path of rural teachers’ local affections. Educ. Res. Monthly 38, 71–77. doi: 10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2021.01.010

Zhang, S. (2022). A comparative study of English learning emotions of primary School students in cities, counties and rural areas. Teach. Admin. 39, 27–32.

Keywords: place-based education, rural school, local culture, English teaching and learning, mixed-methods approach

Citation: Shi H and Ma L (2025) Embedding local cultural richness in English language education: a place-based dual-core approach for rural schools in China. Front. Educ. 10:1580324. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1580324

Received: 20 February 2025; Accepted: 20 May 2025;

Published: 25 June 2025.

Edited by:

Min Fan, Communication University of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Wenchen Guo, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaJiazhou Wu, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2025 Shi and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Shi, c2hpaG9uZzIwMDVzZEAxNjMuY29t

Hong Shi

Hong Shi Lirui Ma

Lirui Ma