- The Regional Centre of Professions of Education and Training Beni Mellal Khenifra (CRMEF), Khenifrat, Morocco

Purpose: This article describes the current state of self-efficacy among preservice teachers’ in mainstreaming gender equality in primary education using the TEGEP scale.

Design/methodology/approach: A survey was administered with a group of preservice teachers at the Regional Center for Education and Training Professions in Beni Mellal-Khenifra/Khenifra annex, Morocco. Using a convenience sample of primary education teachers, 111 participants were asked to assess their efficacy in knowledge and awareness, teaching methods, and attitudes related to gender equality using a six-point Likert scale.

Findings: The preservice teachers reported positive perceptions in adopting gender-responsive teaching methods and in attitudes that basically consolidate gender equality. However, the results also highlight their lack of necessary knowledge to translate these positive attitudes and good practices into sustainable gender equality practices. The level of self-efficacy was found to be moderate in gender knowledge and awareness, but strong in practices and attitudes.

Originality/value: This study provides particularly useful preliminary results in describing the current state of training in mainstreaming gender in teacher training programs. It serves as a starting point for further studies to advance research on gender equality in educational settings. Given the absence of a sustainable approach to gender equality education, integrating gender equality into training is beneficial in instilling good practices and positive attitudes in preservice teachers’ practices, contributing to the promotion of gender equality values.

Introduction

Teacher educators must demonstrate attentiveness to the concerns expressed by preservice teachers with whom they engage, thereby fostering the reinforcement of their pedagogical disposition in preparation for future instructional endeavors. In leveraging pedagogical opportunities, it is crucial for preservice teachers to identify weaknesses in the lesson, recognize the barriers hindering gradual expression, gather diverse perspectives, and develop emergency response capabilities.

Engaging preservice teachers in serious discussions on sensitive topics like gender equality can be challenging, especially when facing historical and traditional biases against women’s rights. This challenge is amplified in environments resistant to progress or entrenched in narrow religious beliefs. Such contexts may lead to contentious debates lacking balance. In dealing sensitive topics, the teacher trainer is required to adopt a bifurcated strategy in two main parts. Firstly, establishing a contract among participants (preservice teachers) to ensure adherence to a roadmap. Secondly, developing a covert plan to support and guide the discussion’s progression (scenario).

Theoretical framework

The world is witnessing a great awakening in defending women and preserving their rights, accordingly “fairness of treatment for women and men, according to their respective needs, which may include equal treatment or treatment that is different but which is considered equivalent in terms of rights, benefits, obligations and opportunities” (International Labour Office, 2000, p. 48). According to UNESCO (2016), gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but also a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world. So, the United Nations’ (United Nations, 2015), Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the globe has turned toward achieving the international sustainable development goals (SDGs), including SDG 5, achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls; SDG emphasizes that it must end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere, and eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation, and eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation. Thus, studying gender equality in education is of paramount importance. Primary school preservice teachers can transfer gender equality practices to their future students, thereby helping them acquire a sense of gender equality. Efforts to promote gender equality must start early and be sustained. Children begin to understand the concept of gender as early as the age of three, and gender stereotypes influence children’s self-perceptions and interests starting at this age. Adolescence, and early adolescence in particular, presents another window of opportunity for education as this is a moment when strong social pressures for boys and girls, and those who do not fit into binary notions of gender, push them to conform to existing gender norms. Promoting gender equality explicitly in curricula and pedagogies, will support the preservice teacher’s work can offer as defenders of gender equality.

Institutional transitions

Despite all the efforts made at the legal, regulatory, and procedural levels within the framework of the gender approach, progress in this field remains relatively limited. This is due to the persistent gap between the requirements of legal frameworks and the realities of societal constraints in all their manifestations. Calls to activate the principles of equality and equal opportunities encounter numerous cultural or socio-economic obstacles, which constrain the opportunities and capabilities available to women within society. These, include low representation rates of women in significant activities and institutions, as well as their confinement to stereotypical social roles that do not align with their potential contributions as key actors in the development process. The gender approach in education involves questioning visions and concepts related to achieving equality and equal opportunities in the education and training system. Central to this is an inquiry into the Moroccan school’s ability to fulfill its role in socialization and to reinforce values of equality and equal opportunities between genders.

Morocco has undertaken multiple initiatives to activate the gender equality approach in the educational sector, in accordance with national public policy commitments in this regard, which recommend an integrated approach that seeks to advance equality and achieve conditions of equal opportunities between the sexes, while rejecting all forms of discrimination and manifestations of violence against the female element. Adopting a gender approach in the field of education, including correcting the understanding of society’s view of gender in education, will lead to reducing the problem of gender disparities with regard to access to school, high school dropout rates, and the challenges of the negative school climate, in addition to reducing the undermining of equal opportunities. In education, there is a failure to employ external indicators of the performance of the educational system, neglect evaluating gains and the level of achievement, and the lack of external performance of the education system from a gender perspective.

Important measures have been identified to increase schooling rates among girls, while reducing indicators of school dropout in rural areas, in addition to eliminating gender differences in access to education, improving the school environment, and providing psychological and pedagogical support for the benefit of female students, in parallel with social support programs designated for those in need. These initiatives, in addition to the general framework determined by the relevant legislative requirements, are based on the recommendations from Morocco’s Strategic Vision for Educational Reform 2015-2030, which emphasized the spread of the values of justice, fairness, and equal opportunities as basic levers for the advancement of rights and gender equality. These recommendations are based on Framework Law 51/17, which defines the basic principles on which the system of education, training and scientific research is based, and the basic objectives of state policy in this field, which were also adopted in the directions of the 2021-2035 New Development model, with the need to evaluate the development taking place in the educational system from the perspective of the gender approach.

Furthermore, effective integration of the gender approach on the ground and the provision of appropriate conditions for implementing this approach in educational systems and programs is needed. This includes, addressing equality issues in curricula and pedagogical tools and improving behaviors and relationships conducive to equality within educational spaces.

Previous studies

How does this study depend in its content on the achievements of previous studies on gender? There is no doubt that taking a logical distance from the topics surrounding our study is necessary. Therefore, we will try, in a first stage, to examine some studies that dealt with different topics about gender: cultural studies, societal studies, political studies, economic studies, and others. Then we turn, in a second stage, to studies that interest our topic and relate to the field of education in general.

Studies on various gender issues

Ellemers (2018) mentioned that stereotypical expectations not only reflect existing differences, but also influence the way men and women define themselves and how others treat them. Stereotypes about the way men and women think and act are widespread, suggesting a great deal of truth. So, there are many differences between men and women in important life outcomes, as these matters are captured in the stereotypes of these groups. Ellemers (2018) shows how gender stereotypes influence the way people attend, interpret and remember information about themselves and others. Considering the cognitive and motivational functions of gender stereotypes helps educators understand their influence on implicit beliefs and communications about men and women. Knowledge of the literature on this topic can inform individuals’ fair judgment in situations where gender stereotypes are likely to play a role.

Eisend (2019) says that future research should address the evaluation of gender roles and their occurrence, the effectiveness of advertising gender roles, and the social effects of gender roles on consumers and society in order to increase public knowledge regarding gender roles through several points including, the point of improving the evaluation of gender roles in advertising. Here, researchers should use a broader concept of gender, explore new ways of characterizing and operationalizing gender roles, develop a useful standard of comparison for deciding upon stereotypes, and explore differences in gender roles across media and advertising formats.

We also add a definition that does not diminish the importance of many of the complexities involved in the relationship between biology and culture, as Jaggar (1983, p. 106-13) sees it. However, the point of view is that determining one’s gender classification is a comprehensive social process. This is not to say that gender is a singular concept, omnipresent in the same form historically or in every situation. Because normative conceptions of appropriate attitudes and activities for gender categories can vary across cultures and historical moments, the management of conduct must be situated in light of those expectations and can take many different forms.

In their article Doing Gender, West and Zimmerman (1987) point out that current views on sex and gender must be critically evaluated and important distinctions made between sex and gender categories. We argue that recognizing the analytical independence of these concepts is essential to understanding the interactional work involved in being a gendered person in society. The purpose of this article is to promote a new understanding of the role of gender as it is integrated into everyday interaction.

Paxton et al. (2007. p. 263–284) argue that women’s political participation and representation varies widely within and between countries. The literature on gender should be reviewed by focusing on women’s formal political participation, discussing traditional explanations for this participation, women’s political representation, such as supply and demand for women, and more recent explanations such as the role of international actors and gender quotas. Paxton et al. (2007) also asked, Does having more women in office make a difference in public policy? A full understanding of women’s political representation requires a deep knowledge of individual cases in a given country and a broad knowledge of comparing women’s participation in different countries.

Deutsch (2007) says that West and Zimmerman (1987) article Doing Gender highlighted the importance of social interaction and thus exposed the weaknesses of socialization and structural approaches. However, despite its revolutionary potential in shedding light on how to dismantle the gender system, gender practice has become a theory of gender persistence and the inevitability of inequality, and argues that we need to reframe the questions to ask how we can undo gender. The research should focus on the following questions.

- When and how do social interactions become less gender-based?

- Whether gender can be irrelevant in an interaction?

- Whether gender interactions always lead to inequality?

- How do institutional and interactional levels work together to produce change?

- How can interaction act as a site of change?

In this chapter, Panel et al. (2015, p. 981–1146) address economic inequality between men and women today, such as; (a) the gender wage gap, (b) lack of equal sharing of household work, (c) gender inequality in access to self-employment, (d) the gender gap in pensions, and € the wealth gap.

Studies on educational gender issues

Smyth (2007, p. 135-153) says that three groups of educational outcomes need to be distinguished on the basis of gender differences:

- Educational participation and attainment, that is, how far young women and men go within the educational system

- educational achievement, that is, how well young men and women perform (for example, in terms of grades) at a given level of the educational system; and

- field of study, that is, the type of course taken within the educational system.

We will only be interested in the first group and the third group because they are related to our field of study on gender.

Gender in education

The role of gender in education is evident at the individual, classroom and institutional levels (Andrews et al., 2020). At the classroom level, gender plays a role in constituent biases and stereotypes. Gender issues at the institutional level are reflected in the roles of adults in schools (i.e., the relative number of staff and constituents versus administrators), structural issues related to the experiences of gender non-conforming trainees, and gender integration versus segregation in the classroom or school. These gender issues will be discussed. Note that gender in education is a very broad topic and covers many areas. The severity of gender biases and issues around the world are complex and important, as are issues of intersectionality (e.g., considering race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, etc. in relation to gender and education).

Kitta and Cardona-Moltó (2022), talk about respondents that rated positively the need for incorporating a gender perspective into curricula, recognizing its importance in reducing sexism, developing gender competencies and practicing a gender-sensitive pedagogy; respondents’ views differed in the emphasis that should be given to gender training. Science students were less demanding than school teaching, physical education and Greek philology students, as well as male than female students. Additionally, the participants rated institutions’ and educators’ commitment to gender equality as neutral and did not recognize existing gender inequalities. This suggests that gender mainstreaming is poorly considered in Greek higher education at institutional, curricular, and relational level.

The world is facing challenges related to the implementation of gender equality policies in Cardona-Moltó’s opinion (2022). She adds that the United Nations (UN) efforts like the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW; United Nations, 1979) and the various declarations and international conferences on women [e.g., UN-Conference in Beijing (United Nations, 1995)] have been successful in highlighting the importance of gender equality as a common goal and gender mainstreaming as a common strategy to achieve this goal. In spite of advancement in certain areas across Europe, gender equality policies in teacher education fail to attain the anticipated targets.

Kitta and Cardona-Moltó (2022) mean comparison by sex revealed that females were more sensitive and critical to gender mainstreaming implementation than male respondents, while no statistically differences were found in awareness of gender inequalities. This indicated that male and female teachers did not perceive stereotypical behavior in teaching based on gender. Results are discussed in terms of identifying needs for equality development in the participant institution as findings are a clear demand for change.

Miralles-Cardona et al. (2021) explained that their study aims to assess future teachers’ beliefs in their capabilities for sustainable gender equality practice after graduation and to analyze differences across degree and sex using a self-efficacy scale specifically designed and validated for this study, and this study provides a reliable and valid instrument specifically helpful for guiding the education for the sustainable development of gender equality in instructional settings. Because there is no systemic approach to teaching sustainability nor valid and reliable instruments to assess gender competence for practicing a gender pedagogy, this tool will hopefully provide teacher education institutions a conceptual and practical framework on how gender equality can successfully be mainstreamed into the curriculum. Infusing sustainable development of gender equality in curricula and assessing interventions as a habitual practice could be useful to monitor sustainability performance over time and assess contributions to SDG5.

Previous studies provide guidance for understanding the state of gender equality in Morocco, especially considering the lack of research using the self-efficacy scale for teachers in practicing gender equality. Given the global progress in this field as reflected in UNESCO documents and scientific research, it is essential to address various gender issues and their dynamics within general context (political, cultural, and social) and specific context of education. Therefore, this manuscript focuses on examining and discussing the state of the self-efficacy scale for preservice teachers in practicing gender equality.

Research question and hypotheses

What is the current state of preservice teachers’ self-efficacy for gender equality practice? This main question will be treated in two hypotheses.

- It is clearly evident in the survey that most of the preservice teachers’ do not have much data on gender. Therefore, the teacher trainer must fill this void or lack of knowledge related to gender equality. So, the first hypothesis will be related to the trainee’s problem of being able to act correctly in the face of the situations he will encounter that establish effective social rules on a solid foundation.

- It seems that the second hypothesis is related to the lack of information about gender for the preservice teachers’, which may prompt them to compensate for it with representations, which makes the desired equality between men and women lose its legitimacy.

Materials and methods

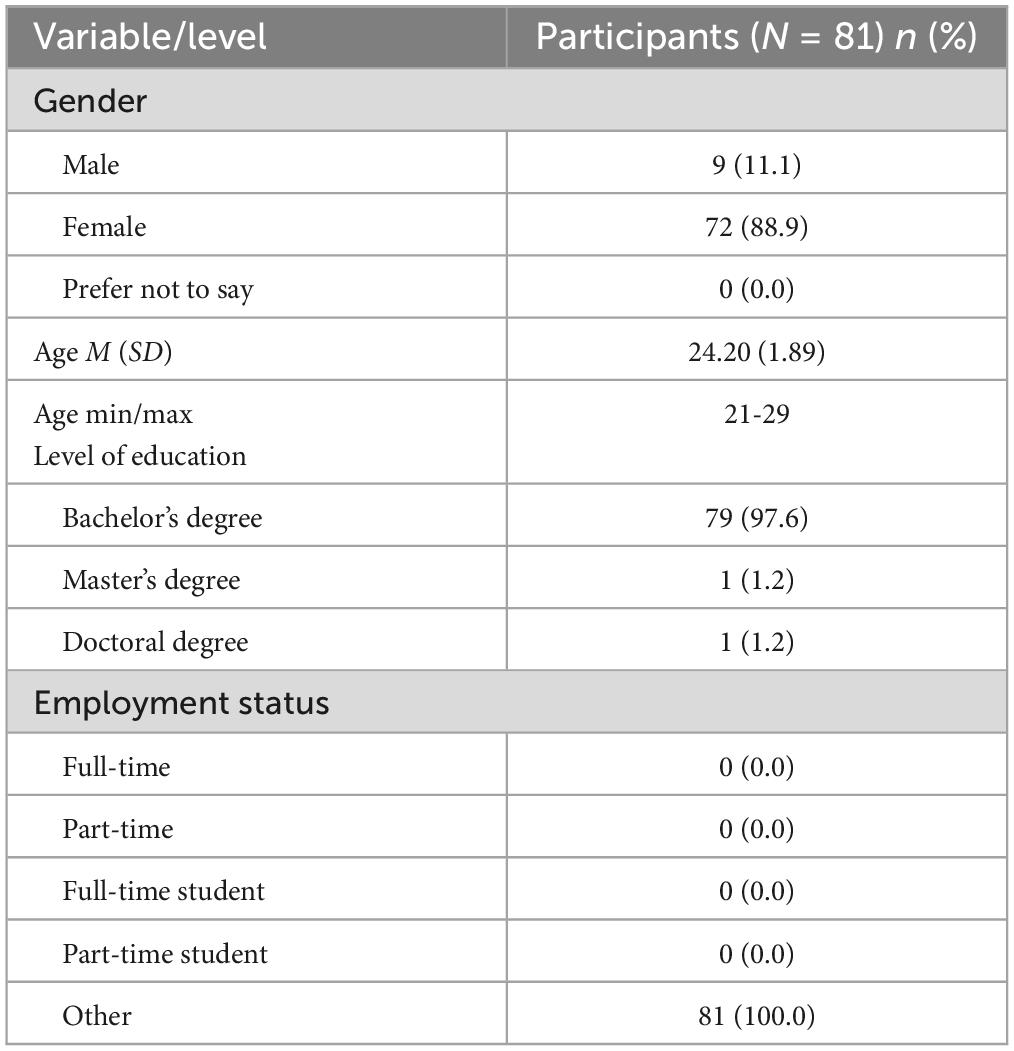

A questionnaire survey design was carried out to understand Moroccan preservice teachers’ (n = 81) perceptions about gender equality in spring/summer 2024. presents the main characteristics of the participants, including age, level of education, employment status, teaching area (Table 1).

The sample for this research is limited to the total number of preservice teachers working in educational institutions for primary education in the Beni Mellal-Khenifra region (annex Khenifra). We started from a sample of 111 student teachers (the majority of preservice primary school teachers enrolled are female). We invited all 111 student teachers, from whom we obtained 81 responses (72.97%; see Table 1). Respondents were representative of the overall make-up of student teacher an included 72 females (88.9%) and nine males (11.1%). The unbalanced gender distribution may bias the results toward female perspectives.

Procedures

Participants (from region of Beni Mellal-Khenifra) were informed about the voluntary nature of the study. Confidentiality was ensured, meaning that no connection to any individual could be made. The data collection process was conducted in accordance with scientific ethical standards. The survey for trainee teachers was distributed during the spring semester of 2024. It was distributed to all preservice teachers’ in the primary education program at the Regional Center for Education and Training Professions in Beni Mellal-Khenifra/Khenifra annex. The survey was completed online using Google Forms after sharing the survey link. Due to the voluntary nature of participation, those who did not wish to participate were not required to fill out the survey. A total of 81 preservice teachers’ out of 111 participated in the final survey.

Measure(s)

This study employed the Teacher Efficacy for Gender Equality Practices (TEGEP) scale. The questionnaire consists 26 items distributed in four parts.

- Part one included sociodemographic data consists five items related to the demographic data of the respondents including, relating to their age, level of education, employment status, and teaching area.

- Part two focused on gender knowledge and awareness. It consists eleven items, including terminology related to gender issues, legislation on gender equity, gender equality vs. gender equity, gender roles, equal opportunities applied to gender, gender discrimination, gender parity, gender bias, sex and gender, gender inequalities, and gender stereotypes.

- Part three collected data on implementing gender-responsive pedagogy. Part three included ten items, including providing equal opportunities to all my students, planning strategies to teach with a gender perspective, mainstreaming gender into course content and materials, taking action to prevent the reproduction or maintenance of inequalities, respecting the different gendered needs and styles of learning, creating learning environments that foster gender collaboration, designing, implementing, and assessing lesson plans with a gender perspective, involving families in the implementation of school-home gender equality plans, and collaborating with colleagues in gender equality plans implementation Educating on gender issues.

- Part four is focused on developing gender attitudes. It consists of five items, including convey/instill gender-sensitive attitudes, deconstruct gender stereotypes and prejudice, confront existing tolerance toward gender discrimination and violence, advocate against all forms of gender injustice, and support school-community links to promote gender equality.

The questionnaire was based on a Likert scale of six points (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Disagree Somewhat, 4 = Agree Somewhat, 5 = Agree, 6 = Strongly Agree). The scale was tested by researchers (Miralles-Cardona et al., 2021) to determine whether the TEGEP structure is equivalent across different subgroups of future teachers. They examined its psychometric properties, including reliability, construct validity, and factor invariance across degree and gender.

Data analysis

The quantitative data from the survey was analyzed for descriptive analysis, reliability, and comparison of means through SPSS version 28 descriptive statistical analyses included calculating frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. To describe and compare preservice teachers’ perceptions in terms of gender perspective, descriptive statistical techniques were used, and all quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 28.

Results

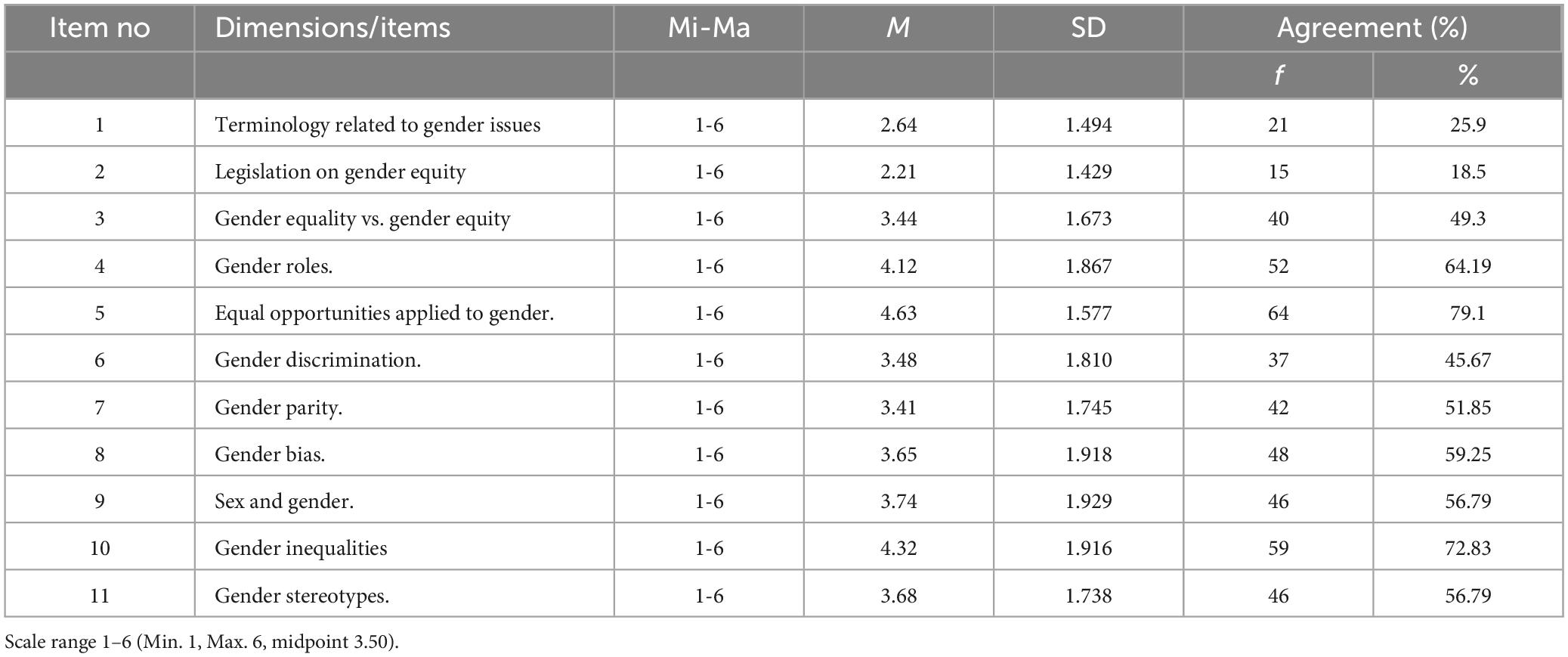

The descriptive statistical data collected through the survey regarding gender knowledge and awareness (Table 2) show that the mean scores on the TEGEP scale range between 2.21 and 4.63, the first is the lowest mean recorded for the item related to gender issues terminology, the second is the highest mean recorded for the item on implementing equal opportunities for both genders. The data obtained from the respondents indicate that the agreement rate on various awareness related to gender knowledge and issues varies from item to item, reaching 25.9% for the item on gender issues terminology, and 18.5% for the item on gender equality legislation, while exceeding 79% for the implementation of equal opportunities for both genders.

Table 2. Preservice teachers self-efficacy for GE practice: descriptives of the knowledge/awareness state.

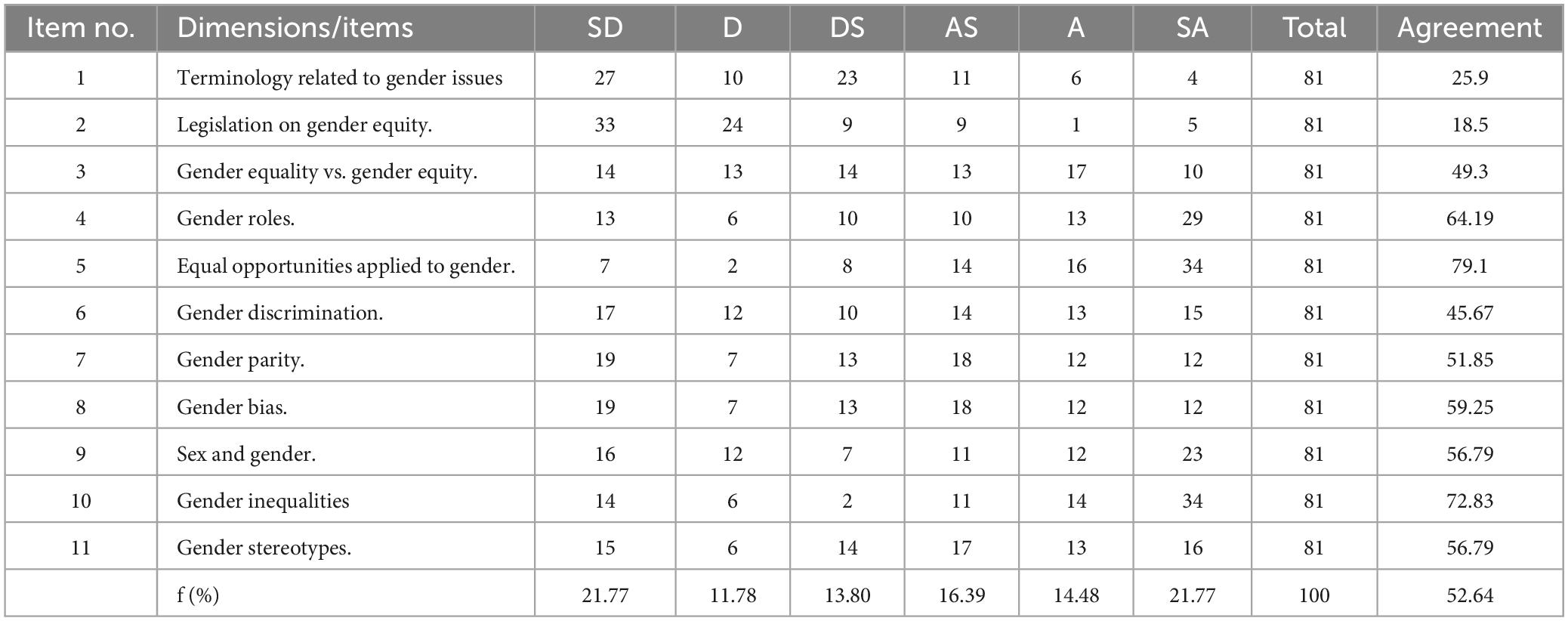

The results confirm that there is no significant variation in respondents’ beliefs regarding gender knowledge and issues. The standard deviation ranges between 1.429 and 1.929 clearly indicating that preservice teachers do not possess the necessary knowledge to identify and distinguish between different gender awareness (see Table 3). This knowledge is insufficient to address all issues related to gender equality, whether in the educational practices of preservice teachers. Therefore, it is noted that the mean of many items is either below or close to the midpoint (3.5).

Preservice teachers’ lack of gender equality awareness poses a significant barrier to adopting gender-sensitive teaching practices and integrating gender perspectives into curricular content. Possessing gender knowledge and awareness is the first step in adopting professional practices that integrate a gender approach in education. It appears that attention to gender terminology issues and legislation should be given a prominent place in interventions due to the lack of knowledge and awareness of these two elements. This constitutes a key entry point in addressing this gap by designing a simple and effective plan that contributes to changing some of the prevailing ideas on the topic of gender equality, or at least, influencing their shift from a negative to a positive stance.

The results for the first component (Table 4) show a clear variation in the distribution of respondents’ opinions across the eleven elements that constitute it. The positions “Strongly Disagree” and “Strongly Agree” each account for 21.77%, followed by “Somewhat Agree” at 16.39%, “Agree” at 14.48%, “Somewhat Disagree” at 13.80%, and finally “Disagree” at 11.78%. Overall, it can be concluded that there is no general trend in the respondents’ opinions as they are distributed across different points on the TEGEP scale. The total agreement rate in its various degrees reaches only 52.64%, which is just slightly above half. This result indicates a weak knowledge related to gender and its issues, despite some elements recording high percentages or exceeding the midpoint.

Table 4. Distribution of the opinions of preservice teachers considering the items of the gender knowledge scale.

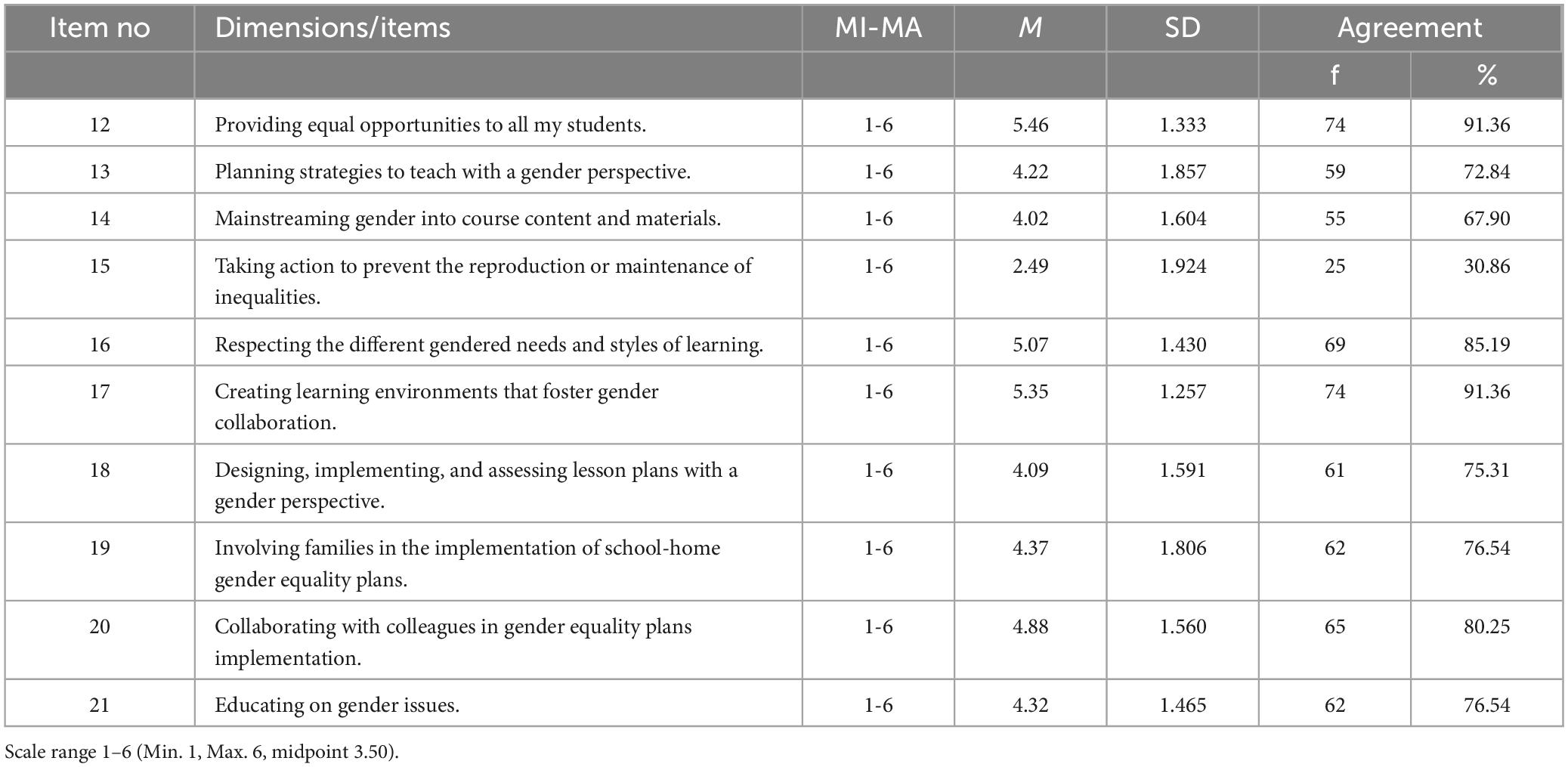

The results of respondents’ self-efficacy in implementing gender-responsive pedagogy methods (Table 5) revealed that they were significantly above the midpoint of the scale (3.5) in most elements except for the element related to taking action to prevent the reproduction or maintenance of inequalities (2.49). But the last result indicating that the trainee teachers are aware of the importance of combating all forms of gender bias. Notably, the element “Providing equal opportunities to all my students” recorded the highest mean (5.46), suggesting that the trainee teachers are fully aware of their ability to establish effective teaching methods in promoting gender equality.

Interestingly, students were more confident in their ability to develop pedagogical practices that respect the different gendered needs and styles of learning (85.19%) and creating learning environments that foster gender collaboration (91.36%) than their ability to involve families in implementing gender equality plans at school and home (76.54%) and collaborate with colleagues in implementing gender equality plans (80.25%).

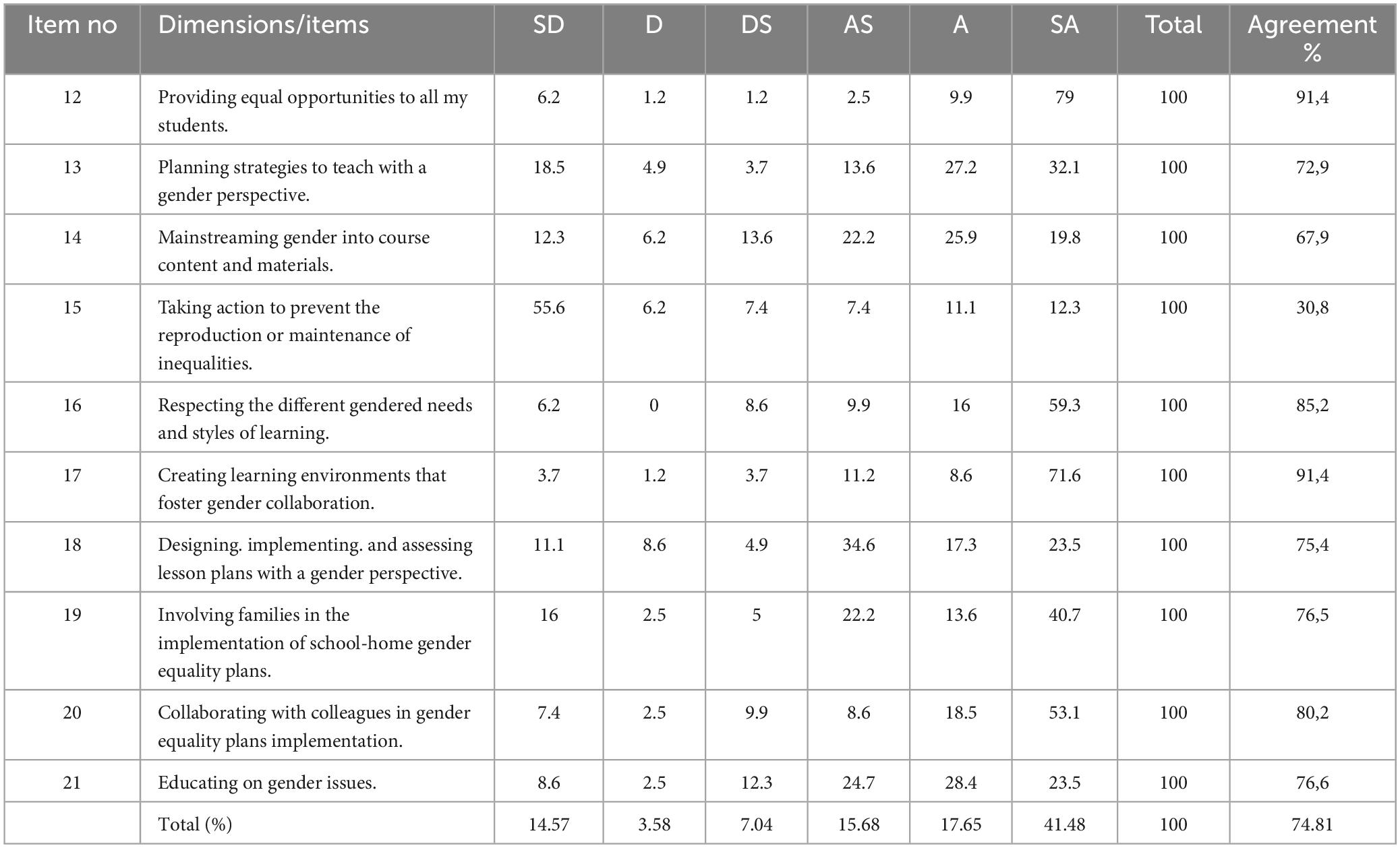

It is also notable that for the component “Implementing a Gender-Responsive Pedagogy,” most respondents expressed “Strongly Agree” at very high rates across various elements of the scale. This includes 79% for the element “Providing equal opportunities to all my students,” 59.3% for “Respecting the different gendered needs and styles of learning,” and 53.1% for “Collaborating with colleagues in gender equality plans implementation.” In comparison, the rate for “Strongly Disagree” remains low in most elements. This result indicates that the trainee teachers are highly committed to pedagogical practices that foster gender equality values. This is a very encouraging outcome for working on the knowledge and gender issues component, thus supporting practice with the necessary knowledge to instill gender equality values.

The results of the “Implementing a Gender-Responsive Pedagogy” component (Table 6) show an agreement rate of 74.81%, which is very high compared to the gender knowledge and issues component. This result emphasizes the importance of focusing on training trainee teachers in the area of gender knowledge. It is also noted that a significant percentage of respondents expressed “Strongly Agree” (41.48%), while the percentage of those who expressed “Strongly Disagree” remains low (14.57%).

These results indicate that trainee teachers are confident in their gender practices related to gender equality. They also highlight the urgent need to train teachers in the cognitive domain of gender and its issues, thereby supporting practices that uphold gender equality values. Strengthening the practices of trainee teachers is further supported by the fact that the majority of them are female (88.9%). This factor is crucial in instilling gender equality values and indicates the transformation in Morocco’s education system. Whereas females used to be a minority in this profession, they now form the majority in primary school teaching roles.

Therefore, the results obtained in the “Implementing a Gender-Responsive Pedagogy” component are very encouraging for promoting gender equality values, regardless of their precise and comprehensive knowledge of gender. They open the door to studying the societal transformation that Moroccan society will experience in the coming years, linked to the significance of educational practices that reinforce gender equality.

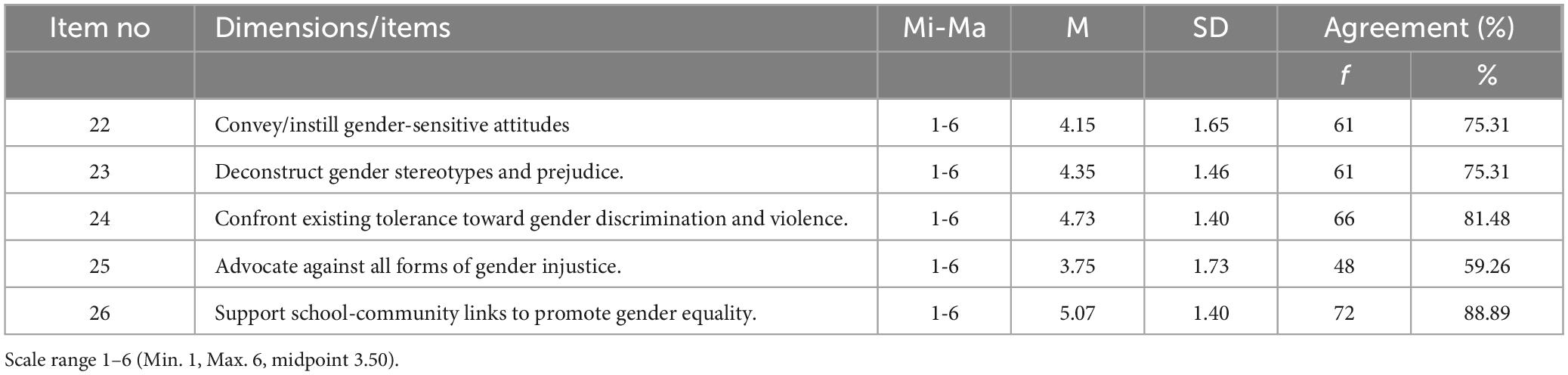

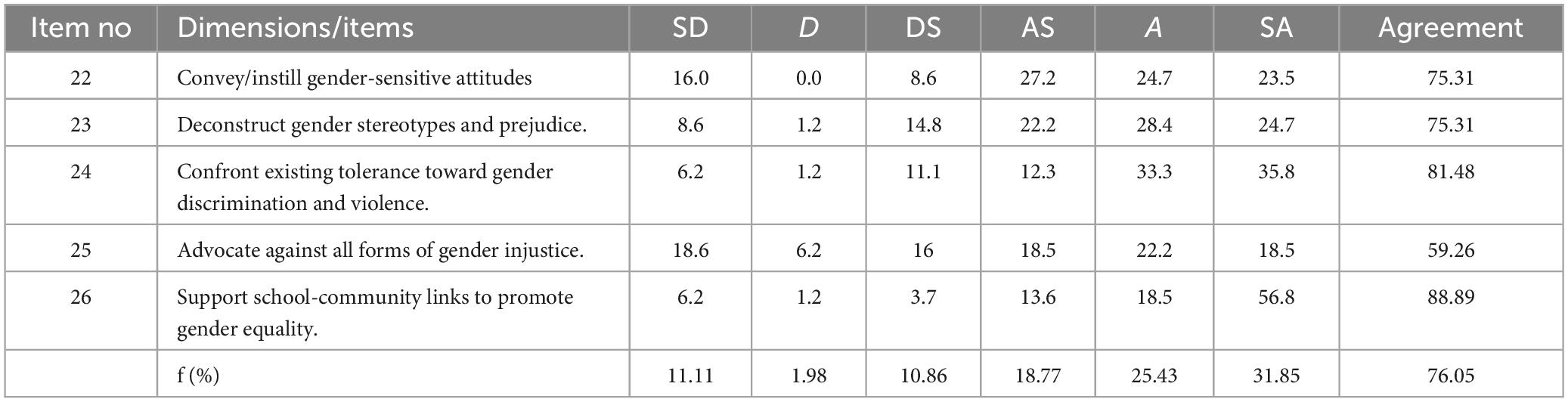

The comparison of various elements of the TEGEP scale within the “Developing Gender Attitudes” (Table 7) component reveals that all averages are above the midpoint (3.5). The element “Support school-community links to promote gender equality” records the highest mean and the lowest standard deviation (M = 5.07; SD = 1.40) with a high agreement rate (88.89%). Similarly, the element “Advocate against all forms of gender injustice” registers the lowest mean and the highest standard deviation (M = 3.75; SD = 1.73) with an agreement rate exceeding half (59.25%). The remaining elements receive approval from respondents at rates exceeding 75%.

Taking into account the midpoint (3.50), the data indicate that respondents attributed significant importance to “Developing Gender Attitudes” in fostering attitudes aimed at achieving gender equality and dismantling gender stereotypes and biases. Additionally, they emphasized supporting school-community links to promote gender equality. The importance of this latter element lies in the fact that gender mainstreaming is closely related to the community and family. Therefore, achieving gender equality extends beyond adopting attitudes and behaviors within the school environment to include the family and community. It is worth noting that respondents’ opinions did not show significant variation, as the standard deviation remains within acceptable limits.

As shown in Table 8, the agreement rate is very high in the first part questionnaire (76.05%), with all items pass 50%, The responses were “strongly agree” (31.85%), “agree” (25.43%), and “somewhat agree” (18.77%), this result validate the previous findings related to the gender knowledge/awareness subscale and the Implementing a Gender-Responsive Pedagogy subscale. In light of these findings, the attitudes and practices of the trainee teachers are based on gender equality, but they require an accurate gender knowledge to adopt appropriate practices and attitudes in this regard.

Discussion and future directions

Education is considered worldwide an essential vehicle for promoting gender equality and confronting gender bias and discrimination. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to integrate gender-responsive approach in teachers training and conduct studies on this awareness to explore the current situation and use it as a starting point for incorporating gender equality in training primary school teachers. Therefore, this research studied the efficacy of primary preservice teachers for Gender Equality using the TEGEP scale. The results revealed a positive response to integrating gender into the practices and attitudes of trainee teachers, confirming that awareness of gender equality increases with higher educational levels. Additionally, female show a more positive response to the survey used in this research compared to males, who expressed less willingness to participate. These findings are consistent with the existing literature (e.g., Larrondo and Rivero, 2019; Serra et al., 2018; Valdivieso et al., 2016), which suggests that the higher the educational attainment, the less sensitivity a gender-responsive education.

The results related to the gender knowledge scale and its awareness indicate a weakness in training on gender equality and a lack of clear programs in training institutions for educating preservice teachers on gender equality. Although they have the ability and commitment to implement gender-responsive methods and adopt positive attitudes and behaviors toward it, they don’t possess the necessary knowledge to mainstreaming gender equality. The previous result confirms the weak and inadequate role of training institutions in incorporating gender equality into their teacher training programs. These findings are consistent with those of researchers (Cardona-Moltó and Miralles-Cardona, 2022) and other researchers in fields outside of education (e.g., Atchison, 2013; Verdonk et al., 2009).

This study provides insights into the perceptions of trainee teachers at the Regional Center for Education and Training Professions in Beni Mellal-Khenifra regarding three key aspects of gender-responsive teaching: (a) gender knowledge and awareness, (b) implementing a gender-responsive pedagogy, and (c) developing gender attitudes. The results generally show consistency and lack of variation among the respondents across the different elements of the sample. The findings indicate that students are prepared for and committed to gender-responsive teaching, but they lack the necessary knowledge and skills to do so effectively. This result presents a somewhat unclear picture of gender consideration in teaching, as it is influenced by the students’ representations rather than being based on solid knowledge foundations. However, it also offers useful insights for developing training programs for teachers that can be used to support the implementation of gender-responsive teaching methods and promote attitudes that enhance gender equality.

For this reason, it has become increasingly necessary to adopt an effective teaching methodology that helps achieve gender equality and provides continuous support in developing the ability to effectively implement gender-responsive pedagogy before actually taking full responsibility for teaching.

In this regard, it would be beneficial to conduct a research study with a sample of teachers after they have started their in-service teaching. This would provide more accurate data on the topic, support the results of this study, and explore the efficacy of teachers in practicing gender equality and their commitment to it. Finally, this study needs to incorporate qualitative research to form a comprehensive view of gender equality in teacher training overall, thus deepening and enriching the research using qualitative techniques such as interviews. Additionally, it is essential to link the scale to the specific social and cultural contexts of Morocco. So, that teaching with a gender perspective is a reality and not a mere proposal disconnected from the institution’s ideology and action plans (Cardona-Moltó and Miralles-Cardona, 2022, p. 83)

One limitation of this study is that most respondents are female. This could potentially impact the study’s results, as the underrepresentation of male perspectives may skew the findings toward female viewpoints, which could affect the overall outcomes. While the current research cannot rule out these interpretations, it seems useful to highlight the issues that might conflict with these results (the imbalance of sex in the sample composition or participants’ previous experience on gender). Another limitation is the sample only included preservice teachers in school year 2024 of a single institution, which does not guarantee that the results can be generalized to other programs and institutions.

Despite these limitations, this study provides insights into the level of self-efficacy among trainees in practicing gender equality upon their graduation. This knowledge helps in utilizing the results to adopt training programs that support positive perceptions among trainees in practicing gender equality. The TEGEP scale offers significant assistance in guiding educational curricula to sustain the practice of gender equality, which calls for further in-depth research in this field. Based on the findings of this study, we propose the following: implement training on gender equality, monitor and evaluate gender equality training, and integrate course content with sustainable development in gender equality.

Furthermore, this research could integrate qualitative approaches to gain a deeper and more holistic understanding of preservice teachers’ motivations and challenges. While this study, through its cross-sectional design, offers valuable baseline insights into participants’ self-efficacy at a specific moment in time, it does not allow for tracking changes in perception over time, assessing the long-term impact of specific interventions, or examining cultural, socioeconomic, and institutional influences.

Conclusion

Achieving preservice teachers’ self-efficacy in practicing gender equality requires integrating a gender-sensitive approach into their training. This necessitates, first and foremost, the dissemination of gender knowledge, followed by the support of attitudes, behaviors, and teaching methods that respond to gender issues. The data from this study indicates that pre-service teachers’ responses in evaluating their self-efficacy in practicing gender equality did not receive the same level of attention across genders. Consequently, female participation in this study was noteworthy in contrast to males. This finding suggests a higher awareness of gender equality among females; however, the lack of necessary training in this field hinders significant progress in gender education.

Moreover, the results of this study indicate that participants report relatively high levels of self-efficacy in practicing gender-sensitive pedagogy. Considering their lack of gender knowledge on one hand and professional experience on the other, this points to an unrealistic assessment of their own gender self-efficacy. Therefore, addressing this gap between perception and practice through training programs that work to bridge the potential discrepancy between perception and actual skills in supporting gender equality practices is essential.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Centre régional des métiers de l’education et la formation Béni Mellal khénifra. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the topic does not raise any sensitivities or infringe on the rights of the participants, and participation was voluntary.

Author contributions

SK: Writing – original draft. SA: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andrews, N., Cook, R. E., Nielson, M. G., Xiao, S. X., and Martin, C. L. (2020). “Gender in education,” in Social and emotional learning section; D. Fisher, Routledge encyclopedia of education, eds T. L. Spinrad and J. Liew (New York, NY: Taylor & Francis).

Atchison, A. (2013). The practical process of gender mainstreaming in the political science curriculum. Polit. Gender 9, 228–235. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X13000081

Cardona-Moltó, M. C., and Miralles-Cardona, C. (2022). “Education for gender equality in teacher preparation: Gender mainstreaming policy and practice in Spanish higher education,” in Education as the driving force of equity for the marginalized, eds J. Boivin and H. Pacheco-Guffrey (IGI Global).

Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69, 275–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

International Labour Office (2000). ABC of women worker’s rights and gender equality. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Jaggar, A. (1983). Feminist politics and human nature, (Philosophy and Society). Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Allanheld, 13–106.

Kitta, I., and Cardona-Moltó, M. C. (2022). Students’ perceptions of gender mainstreaming implementation in university teaching in Greece. J. Gender Stud. 31, 457–477. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2021.2023006

Larrondo, A., and Rivero, D. (2019). A case study on the incorporation of gender-awareness into the university journalism curriculum in Spain. Gender Educ. 31, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1270420

Miralles-Cardona, C., Chiner, E., and Cardona-Moltó, M. C. (2021). Educating prospective teachers for a sustainable gender equality practice: Survey design and validation of a self-efficacy scale. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 23, 379–403. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-06-2020-0204

Panel, O., Ponthieux, S., and Meurs, D. (2015). Gender inequality. Handb. Income Distribut. 2, 981–1146. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59428-0.00013-8

Paxton, P., Kunovich, S., and Hughes, M. M. (2007). Gender in politics. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 200, 263–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131651

Serra, P., Soler, S., Prat, M., Vizcarra, M. T., Garay, B., and Flintoff, A. (2018). The (in)visibility of gender knowledge in the physical activity and sport science degree in Spain. Sport Educ. Soc. 23, 324–338. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2016.1199016

Smyth, E. (2007). “Gender and education,” in International studies in educational inequality, theory and policy, eds R. Teese, S. Lamb, M. Duru-Bellat, and S. Helme (Dordrecht: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5916-2_6

UNESCO (2016). Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all (Global Education Monitoring Report). Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations (1979). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW). Available online at: http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cedaw.aspx

United Nations (1995). Beijing platform for action. Available online at: http://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/Beijing_Declaration_and_Platform_for_Action.pdf

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

Valdivieso, S., Ayuste, A., Rodríguez-Menéndez, M. C., and Vila-Merino, E. (2016), “Educaci_on y género en la formaci_on docente en un enfoque de equidad y democracia,” in Democracia y Educaci_on en la Formaci_on Docente, I. Coord Carrillo-Flores (Barcelona: Universidad de Vic-Universidad Central de Cataluña), 117–140.

Verdonk, P., Benschop, Y., de Haes, H., Mans, L., and Lagro-Janssen, T. (2009). “Should you turn this into a complete gender matter? Gender mainstreaming in medical education. Gender Educ. 21, 703–719. doi: 10.1080/09540250902785905

Keywords: preservice teachers, gender, TEGEP scale, practices, attitudes, gender equality, mainstreaming, Morocco

Citation: Kmiti S and Azeroual SH (2025) Efficacy of primary preservice teachers for gender equality: the state of knowledge and practice and attitudes for gender in Morocco. Front. Educ. 10:1581005. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1581005

Received: 21 February 2025; Accepted: 13 May 2025;

Published: 06 June 2025.

Edited by:

Tanya Pinkerton, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Heather Villarruel, Arizona State University, United StatesJordan Margaret Olson Causadias, Arizona State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Kmiti and Azeroual. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Said Kmiti, a21pdGlzYWlkQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Said Kmiti, orcid.org/0009-0000-6807-4047; Sidi Hassane Azeroual, orcid.org/0000-0002-8265-2699

Said Kmiti

Said Kmiti Sidi Hassane Azeroual†

Sidi Hassane Azeroual†