- 1Educational and Organizational Leadership Department, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, United States

- 2Corporate and Continuing Education Division, Rowan Cabarrus Community College, Salisbury, NC, United States

- 3Teaching and Learning Department, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, United States

Introduction: Continuous improvement (CI) has transformative potential but far too often that potential is unrealized. Practitioners engaging in CI are frequently guided by mindsets that derail system transformation by shifting the focus from improving systems to fixing people.

Methods: Employing multiple data sources (document analysis of dissertations in practice and interviews) this multi-case study examines nine cases of scholar-practitioners engaging in CI work and how they mitigated the impact of deficit mindsets.

Results: Cross-case analysis revealed four strategies for disrupting deficit ideology in CI work: composing intentional teams, building team capacity, employing critical theory, and involving those impacted.

Discussion: Implications for engaging in CI and teaching CI are discussed.

Introduction

The system of public schooling in the United States was not designed to serve all children. The first schools in the US were intended for wealthy, White, landowning, Christian young men. Over time, policy, legislation, and legal decisions have secured the right to access for women, children of color, multilingual learners, and students with disabilities (Justice, 2023). As different groups of students were integrated into a system not designed for them, hierarchies within the system were established to ensure variable experiences within the schools. Ferri and Connor (2005) explain:

Although special education may be seen as benevolently serving students with disabilities, it also serves the needs of the larger education system, which demands conformity, standardization, and homogenization… Ironically, history illustrates that at the very moment when difference is on the verge of being integrated or included, new forms of containment emerge to maintain the status quo… (p. 97).

The central law of improvement states that every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets (Langley et al., 2009). If the central law of improvement is true, disparities in achievement and outcomes should not be surprising for those being served by a system that was not designed with them in mind.

While some think of improvement as returning a system to its optimal functioning, that cannot be the case for schools because there is no optimal state to return to, as public schools have never served all (i.e., racially and linguistically minoritized, poor, neurodiverse, LGBTQIA+) children well (Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017). While schools are intended to cultivate genius (Muhammad, 2020) and to allow children to achieve their highest potential (Walker, 2000), many of them engage in practices that harm children, stifling their creativity and curtailing their curiosity (Love, 2019). Furthermore, through policy (such as funding based on property taxes), practice (such as over-surveillance and disproportionate discipline), and perceived meritocracy (such as gifted programs and advanced placement), schools allow the privileged to hoard opportunities from the masses (Diamond and Lewis, 2022). For decades, scholars and educators alike have tried to determine methods and means to make schools more just (Ishimaru, 2019), more humanizing (Anderson and Davis, 2024; Benoliel et al., 2019), and more equitable (Ainscow et al., 2013; Green, 2017). As scholars examine the intersection of equity and improvement, they wrestle with the question of whether continuous improvement can remedy a system with an unjust design.

Continuous Improvement (CI) is an umbrella term for a family of methodologies that drive systems improvement and organizational learning, where practitioners engage in iterative inquiries to evaluate their current state, articulate their ideal state, design changes or interventions to move toward the ideal state, and test the efficacy of the changes employed. There is considerable diversity among CI methodologies employed in education, though all are pragmatic in addressing problems of practice; some are agnostic in focus (i.e., participatory action research), some focus on systems change (i.e., improvement science and data wise), some prioritize addressing implementation issues (i.e., design-based implementation research and implementation science), and some concentrate primarily on instruction (i.e., lesson study). CI methodologies that focus on systems change, such as improvement science, which is the focus of this manuscript, are informed by systems theory. According to systems theory, a system, whether it is a school system or a single classroom, is a collection or group of interconnected elements (people, departments, agencies) working toward a common goal (Meadows, 2008). Meadows (2008) explains that the purpose or function of a system is not seen in rhetoric or policy but in the system’s behavior. The disparate outcomes of different groups of students in US schools confirm Shujaa’s (1993) assertion that the purpose of schooling in the United States is to perpetuate the status quo.

Systems can be bound by constraints, or “components of the system that limit the overall performance or capacity of the system” (Langley et al., 2009, p. 78). One such systemic constraint in education is deficit mindsets. Du Bois (1935) suggested that mindset may be a constraint on the fair education of Black children when he posed the question, “Does the Negro need separate schools?” DuBois emphasized the need for “sympathetic touch between teacher and pupil,” which involves the teacher being aware not only of the individual child but also of the sociopolitical and economic realities faced by the child’s community. As he elaborates on this notion of sympathetic touch, he argues that how children and their communities are perceived will directly impact the extent to which they are educated. Although made 90 years ago, his argument reflects his awareness of deficit ideologies common to educator socialization in the early 20th century. Justification for oppression based on pseudoscience (eugenics) was fueling the imaginations of those designing educational assessments and establishing the field of teacher education (Clayton, 2021; Gould, 1996). This historical moment provides the sociological foundation for deficit ideology today. While mindsets can constrain the educational system, they can also thwart efforts to improve it. In WestEd’s report on continuous improvement, Getting Better at Getting More Equitable, Valdez et al. (2020) found that school leaders and CI technical assistants identified mindset as a barrier to continuous improvement aimed at equity. Valdez et al. (2020) explain that the mental models employed by educators

“influence how systems are investigated and how problems are defined… [and] individual biases may lead to improvement projects that address symptoms, rather than root causes, of problems” (p. 13).

Far too often, in their attempts to achieve equitable outcomes, educators focus on fixing individuals instead of examining and transforming the systems that produce these results (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Anderson and Hinnant-Crawford, 2023). Educators’ tendency to locate problems of practice (or opportunities for improvement) within individuals and their communities, instead of in educational systems, stems from deficit ideological frames (Gorski, 2011). Deficit mindsets displace responsibility for inequitable outcomes (such as disparities in achievement and disproportionality in discipline) by blaming students, their families, and their communities for what educators perceive as individual failure, instead of systemic failure. Deficit mindsets limit the likelihood of improvements that serve equitable aims because the focus of these improvements is misdirected; the interventions designed to be “solutions” fail to address the underlying systemic causes (Gorski, 2011; Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson, 2022; Milner, 2020). Because CI work seeks to transform systems rather than individuals, unaddressed deficit mindsets can undermine the process by misidentifying root causes, thereby reinforcing inequities instead of dismantling them. Deficit mindsets derail the potential of continuous improvement.

CI has become a central tool for improving the quality of schools and student outcomes and is argued to have justice potential (Anderson and Davis, 2024; Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Bocala and Boudett, 2015; Stosich, 2024; Yurkofsky et al., 2020). Recent scholarship suggests that CI has potential for equity by ensuring that each student is provided with the necessary resources and support to attain their full academic and social potential (Bush-Mecenas, 2022). CI can enhance equity by amplifying marginalized voices, addressing systemic root causes, and driving systemic change through data-driven and collaborative processes (Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Sandoval and Neri, 2024). CI is necessary for systems improvement because causal links are not always visible in systems; the delay in feedback in a complex system means that when the problem is readily identifiable, it may be difficult to pinpoint the original cause. Utilizing systems theory, CI leads practitioners through root cause analyses, enabling them to identify changes that address the root of the problem. Furthermore, continuous improvers can implement one of two types of changes—first-order changes that restore the system to optimal performance and second-order changes that transform the system to new levels of performance (Langley et al., 2009). When it comes to equity and justice in schools, second-order change within a continuous improvement framework is needed. This is because first-order changes merely reinforce the existing structure of a system that was never designed to equitably serve all students. As history shows, integrating marginalized groups into the education system has often been accompanied by new forms of stratification that preserve the status quo (Ferri and Connor, 2005). To disrupt these deeply embedded inequities, educators and leaders must challenge the underlying mental models, institutional practices, and power dynamics that shape students’ outcomes. Second-order change demands a fundamental reimagining of the system’s purpose, shifting from standardization and control to humanization and liberation.

One of the reasons CI has not met its potential for transformative change in schools is the proliferation of deficit mindsets among educators and CI practitioners. Deficit mindsets often drive interventions that target individuals instead of systems (Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson, 2022; Milner, 2020). This orientation undermines the equity goals of CI initiatives. Therefore, understanding and addressing deficit mindsets is essential for ensuring that improvement work leads to systemic rather than superficial change in educational practice. The purpose of this study is to examine how scholar-practitioners, specifically EdD graduates who led continuous improvement efforts, documented in their dissertations in practice (DiPs), addressed and mitigated the impact of deficit mindsets in the continuous improvement process.

CI’s unrealized transformational potential

There is no shortage of improvement literature discussing the potential of improvement to lead to systems change and more equitable opportunities to learn (Anderson and Davis, 2024; Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Bocala and Boudett, 2015; Stosich, 2024; Yurkofsky et al., 2020). However, potential and possibility are often at odds with the reality of CI in practice, as noted in the many critiques of CI (Capper, 2018; Horsford et al., 2018). The shortcomings of CI’s pursuit of equity are usually described in terms of (a) the processes employed (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Ishimaru and Bang, 2022; Hinnant-Crawford, 2025; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Valdez et al., 2020), (b) the goals established in the work (Anderson and Hinnant-Crawford, 2023; Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson, 2022; Sandoval and Neri, 2024), and (c) the types of change being tested (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Safir and Dugan, 2021).

While defining problems and developing solutions may seem like a benign activity, these power-laden processes within improvement can be paternalistic instead of participatory. Ostensible experts (teachers, leaders, etc.) with good intentions can sometimes define problems and prescribe solutions that they believe are best for individuals (students, families, communities) experiencing a problem without their input on how the problem is defined or addressed. Deficit mindsets can influence who is invited to be a part of the improvement process because mindset impacts who is perceived to have a valuable contribution. Often, when processes are ostensibly participatory, so-called experts maintain the decision-making power in the process (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016). Improvement scholars who advocate using CI to advance equity consistently emphasize the importance of including individuals closest to the problem in the process, and some even highlight the necessity of allowing underrepresented and minoritized voices, ideas, and priorities to guide the improvement process (Ishimaru and Bang, 2022; Hinnant-Crawford, 2025; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Valdez et al., 2020).

Another common critique of improvement is questioning the underlying purpose of making improvements. In their 5S framework for defining problems in improvement research, Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson (2022) said that most improvement projects can be characterized as pursuing efficiency, efficacy, or justice. Sandoval and Neri (2024) argue that in CI work, practitioners too often focus on improving dominant outcomes, such as academic achievement and its prerequisites. They distinguish between improvement for equity (reducing disparities in dominant outcomes) and improvement for justice, stating, “an improvement for justice centers on the work of granting agency, comfort, and dignity to students, and to minoritized students in particular” (Sandoval and Neri, 2024, p. 5). Improvement—to what end—is an important question to grapple with, as Vossoughi and Vakil (2018) note that so-called equity purists in STEM represent “a form of racial capitalism that relies on the labor and genius of youth of color to maintain and extend US imperial and military power” (p. 117). Deficit mindsets limit the possibilities for improvement outcomes by failing to envision educational systems that propel students to achieve their individual and communal dreams instead of producing narrow visions of productive citizens who perpetuate the capitalist and imperialistic status quo. In other words, improvement should not simply be a tool to make schools more efficient at reproducing current societal structures. Improvement should be a tool for realizing freedom dreams that view the outcomes of education as more expansive than merely preparing individuals for the workforce in a capitalist economy and as competitors in a global market. Last but not least, critics question the changes advanced through CI.

In Street Data, Safir and Dugan (2021) describe Improvement Science, one approach to CI, and equity as incompatible because of its focus on small, high-leverage changes. Others question the reliance on incremental change instead of large-scale sweeping change. Improvers’ understanding of equity impacts the types of changes adopted in improvement projects. Bang and Vossoughi (2016) highlight that many seemingly equity-driven improvement initiatives focus on assimilating marginalized individuals into unjust systems rather than improving the system itself. Valdez et al. (2020) discuss the promising practice of the “equity pause” in the improvement process. This pause “is a moment in a discussion or process when participants reflect on their team dynamics, question how a team is addressing equity, and critically examine their own assumptions… this practice helped the team ask themselves, ‘How are we working with colleagues to ensure the system is changing, and not trying to mold the kids into the system that already exists?” (p.10). Without intentional reflection to combat deficit mindsets, teams can select changes that focus on improving people instead of systems.

Calls for the use of critical perspectives in CI are frequently seen in literature critiquing continuous improvement for failing to adequately address issues of equality and justice. Jabbar and Childs (2022) argue succinctly that, “education researchers should apply critical lenses and perspectives to improvement research that wrestle with the complexities of equity and inequality” (p. 224). Hinnant-Crawford et al. (2023) argue that oppression, including but not limited to racism, sexism, classism, colonialism, nationalism, and heteronormativity, is a common cause within educational systems. Common causes are defined in improvement scholarship as causes “inherent in the process of the system overtime, affect everyone working in the process, and affect all outcomes of the process” (Langley et al., 2009, p. 79). Recognizing oppression as a common cause, in their advancement of ImproveCrit: a Critical Race Theory (CRT) approach to improvement, they argue that as improvement scholars, “tell improvers to ‘see the system’ they have to see it with a critical eye, examining hegemonic forces that are designed to operate without being seen” (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023, p. 110). Similarly, Irby explains that when one fails to employ critical perspectives, they run the risk of using continuous improvement to reinforce the status quo by “generating problems, plans, action steps, and so forth, suggesting that many things might be problems, but none of them are necessarily rooted” in the true problem of systemic oppression (2022, p. 162). The truth is that continuous improvement does not necessarily lead to equitable outcomes (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Capper, 2018; Horsford et al., 2018; Safir and Dugan, 2021). Improvement scholars and practitioners must continue to convey the potential for transformative improvement, recognize that this potential has yet to be fully realized, and pursue remedies for barriers to improvement’s potential, such as deficit mindsets.

The theory of mindset

Before one can define a deficit mindset or its proliferation in the field of education, one must first understand what a mindset is. While the term “mindset” is commonly used in daily vernacular, its definitions in scholarly literature divergent, depending on the field. Although scholarship on mindset began with the Würzburg School of cognitive psychology, theories of mindset also appear in social psychology, organizational leadership, and positive psychology (French, 2016).

The theory of mindset that guides this study is grounded in social psychology and organizational leadership. Therefore, mindsets are cognitive frames “that attend to and influence the totality of cognitive processes with or without an identifiable task” (French, 2016, p. 678). Cognitive framing is often discussed in the context of decision-making (Kahneman, 2003; Larrick, 2016; Tversky and Kahneman, 1981). Decision-making is essential throughout the improvement process, from deciding on the aim (which problem to address) to determining the course of action (which change will produce the best results). Cognitive frames, or mindsets, can introduce bias into the decision-making process and lead individuals to courses of action that are not seen as rational (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981). Larrick (2016) explains,

People are not aware of their own reasoning processes or of the limitations that may accompany them. As people form a judgment using whatever evidence they can generate from their own memory and experience, they often find it easy to reach a conclusion. This feeling of ease then becomes a signal that “I must be right.” And once an initial search for evidence has produced a judgment, people then tend to stop searching further; this tendency can lead to judgments based on a small, often biased, set of evidence (p. 444).

Cognitive frames are also described in social psychological and leadership literature as heuristics or “mental shortcuts” (Larrick, 2016, p. 443).

Social psychology and organizational leadership have viewed mindsets as driving both individual and collective sensemaking, which has important implications for improvement, since improvement work is often completed in teams. Weick et al. (2005) remind sensemaking scholars that the ways in which organizations (and individuals within them) make sense of phenomena are not rooted in truth; in fact:

Sensemaking is not about truth and getting it right. Instead, it is about continued redrafting of an emerging story so that it becomes more comprehensive, incorporates more of the observed data, and is more resilient in the face of criticism (p. 415).

This is why mindsets can be difficult to shift or disrupt, even when new information is presented.

Mintrop and Zumpe (2019) write specifically about a common improvement mindset with “five heuristics” or interpretive frames that illustrate patterns of thinking exhibited by educational leaders. In their study of leaders engaged in CI work, the evident heuristics were (1) my problem is the absence of my solution, (2) change is about filling an empty vessel with new material, (3) learning is implementing, (4) designing aims at conventions, and (5) rationality is about adopting what works. Some of these five heuristics align with the common decision-making heuristics in the literature: anchoring, availability, and representativeness (Thaler and Sunstein, 2021). Because cognitive frames and mindsets have a bias toward the status quo, it is not surprising that mindsets 1, 4, and 5 are related to what leaders feel they already know. The availability heuristic means individuals often make decisions and judgments based on what is readily available in their minds and recent memories. The representativeness heuristic, also described as the similarity heuristic, suggests that people compare what they are dealing with to something similar and make a decision based on how alike the two things are. Cognitive frames, mindsets, and heuristics are not always negative, but they “can lead to major errors” in judgment (Thaler and Sunstein, 2021, p. 32). It is important to note that Mintrop and Zumpe present these five heuristics not as definitive features of an improvement mindset, but as tensions that scholar-practitioners must grapple with when striving to enact equity-focused continuous improvement. The leaders in their study, despite being in a program that taught them other ways to improve schools and address problems of practice, often reverted to these as their default heuristics that had to be overcome. Bonney et al. (2024) found a similar pattern when examining EdD students’ use of Improvement Science, where despite their coursework and instruction, they “struggled to avoid framing problems in terms of their own beliefs and assumptions and to instead understand the problem from the perspective of those who are impacted” (p. 20). Scholarship on CI illustrates that even in the face of instruction in new approaches to problem-solving, old problem-solving mindsets often guide action.

While mindsets may be difficult to change, the task is not insurmountable. Aguilar explains in the Art of Coaching, “one of the highest leverage ways that a coach can work is by interrupting mental models which if left untouched create impenetrable fortresses around transformation” (Aguilar, 2013, p. 189). The disruption of mindsets is not limited to those in a coaching capacity. Leaders can intervene and influence the very heuristics that influence decision-making. In their bestselling book, Nudge, Thaler and Sunstein (2021) argue that “choice architects” can nudge decision makers in such a way that their cognitive frame or mindset is less likely to bias their decisions. A choice architect “has the responsibility for organizing the context in which people make decisions,” much like the person leading an improvement initiative (Thaler and Sunstein, 2021, p. 3). The purpose of nudging is to “help people make the choices that they would have made if they had paid full attention and possessed complete information, unlimited cognitive ability, and complete self-control” (Thaler and Sunstein, 2021, p. 7). Nudging does not forbid individuals from any particular course of action, but it can help steer them toward making better decisions—about the problems to address and how to address them. Nudging takes advantage of the heuristics that shape mindsets, such as the availability heuristic, by influencing the information that is available. Manipulating heuristics that influence decision-making through nudges means that the disruption of mindsets (including deficit mindsets) is possible.

Deficit mindset

In this study, a deficit mindset is defined as a cognitive frame, a lens that interprets the location of educational problems within individuals, such as students, families, or communities, rather than with the systemic conditions that produce inequitable outcomes. The phenomenon of deficit mindset in education is rooted in cognition but is often described in terms of the judgments it leads to (interpretations) or the actions that precipitate as a result of those judgments. Therefore, a deficit mindset has consequences for both thought and action.

Valencia’s (2010), work on deficit thinking illustrates the conclusions that a deficit mindset can lead to. He lays out six characteristics of deficit thinking: victim blaming, oppression, pseudoscience, temporal changes, educability, and heterodoxy. In these characteristics, he argues that deficit thinking is a “dynamic and chameleonic concept” (p. 13). The ideology fueling deficit mindsets changes over time; one moment its eugenics and hereditary deficiencies fuel the narrative, the next moment it’s cultural deficiencies. Despite the underlying ideological justifications, the function of the mindset is to articulate what is “wrong” with whoever is underachieving. Bensimon (2005) speaks of deficit cognitive frames and states that a cognitive frame is an “interpretive frameworks through which individuals make sense of phenomena”(p. 101). She goes on to say that cognitive frames “determine what questions may be asked, what information is collected, how problems are defined, and what action should be taken” (p. 101). A deficit cognitive frame has real consequences for individuals engaging in research and improvement work.

Deficit mindsets are also described as catalysts for certain types of action or behavior. Argued to be one of the five contributing factors to the opportunity gap (or a constraint on the educational system), Milner describes deficit mindsets in terms of the behaviors they lead educators to adopt. Milner explains, “deficit mind-sets make it difficult for educators to develop learning opportunities that challenge students. For instance, teachers may believe that some students cannot master a rigorous curriculum and consequently may avoid designing important learning opportunities for those students” (2020, p. 26). In educational improvement, deficit mindsets lead to interventions that try to change people instead of changing systems (Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson, 2022).

Deficit mindsets or deficit cognitive frames are pervasive among practitioners, including teachers, leaders, and education consultants. These mindsets often dictate how problems are framed and addressed by influencing sensemaking and, subsequently, behavior.

Manifestation of deficit mindsets

Deficit mindsets are informed by deficit ideology; narratives or rationales that displace responsibility for inequitable outcomes by shifting the responsibility to students, families, or broader communities. Gorski defines deficit ideology as:

A worldview that explains and justifies outcome inequalities - standardized test scores or levels of educational attainment, for example - by pointing to supposed deficiencies within disenfranchised individuals and communities… Simultaneously, and of equal importance, deficit ideology discounts sociopolitical context, such as the systemic conditions (racism, economic injustice, and so on) that grant some people greater social, political, and economic access, such as that to high-quality schooling, than others(p. 153).

Deficit ideology leads to deficit narratives in popular culture as well as in research. In a study of the pervasive nature of deficit narratives in quantitative educational research, Russell et al. (2022) outline three functions of deficit narratives related to race:

1. Denigrate people of one race and elevate those of another

2. Justify the oppression of the denigrated group

3. Maintain the power of the elevated group (Russell et al., 2022, p. 1–2).

Russell et al. (2022) examined 61 quantitative studies where race was used as a variable (predictor) and how it was interpreted in the findings or discussion section—and whether that interpretation could perpetuate deficit narratives. A derivative of CRT that focuses on quantitative research, QuantCrit’s third principle states that categories are not neutral; when race is included as a variable, it should be viewed as a proxy for racism (Gillborn et al., 2018). Gillborn et al. (2018, p. 172) explain in more detail:

Black groups in the UK and African American and Latinex students in the US, are often viewed through a deficit lens. This means that research which may have been intended to expose and challenge a race inequity becomes yet more fodder for racist practices and beliefs. Imagine, for example, that a project finds that ‘race was significantly correlated with lower achievement’. A critical race theorist will likely interpret the sentence to mean that racism is a significant factor that affects the chances of achieving. But uncritical White observers, practitioners, and policy-makers may take away the message that some races are less able to achieve.

Analyzing studies that used the variable race to interpret outcomes for Black students, Russell et al. (2022) found that 56.5% of studies attributed the outcome to group membership, whereas only 30.3% attributed outcomes to an intervention or larger system. Overall, they found that 59% of the studies’ interpretation of the race variable could “be used to support a deficit narrative” (p.12).

In addition to scholars’ interpretations, Bertrand and Marsh (2015) examine how teachers make sense of data and the mental models that lead to the narratives they tell themselves. The four mental models named (instruction, understanding, nature of the test, student characteristics) are explained by the teacher’s perceived locus of causality: internal or external; stability: stable or unstable; and controllability: controllable or uncontrollable. For instance, if a teacher attributes a student’s outcomes to instruction, that is internal, unstable, and controllable—meaning they can do something to impact and change the outcome. On the other hand, a teacher may attribute a student’s outcome to student characteristics, which are external, stable, and uncontrollable. This mental model completely removes responsibility from the teacher and attributes the problem to the child (or some characteristic of the child). Deficit ideology leads to a mindset that attributes achievement to characteristics.

Due to the universal nature of deficit ideology in education, it is not surprising that this line of thinking often informs practitioner scholarship. Deficit ideology has been identified by a number of improvement scholars as a danger to the improvement process. Biag (2019) calls for scholar-practitioners to engage in critical self-reflection in order to “understand who they are, identify with the contexts in which they serve, and critique the manner in which they engage in the improvement process e.g., ‘in what ways does my identity influence how I see our problem?’ (2019, p. 103). In their 5S framework for problem definition, Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson (2022) discuss the potential for deficit ideology to derail problem definition procedures when determining the source of the problem. Noting that problem definition is a sensitive process that can lead to guilt and/or blame, they recognize that deficit mindsets can lead to blaming individuals instead of seeing the systems that produce the problem. Therefore, we sought to investigate how scholar-practitioners, specifically EdD graduates who led continuous improvement efforts, disrupted deficit mindsets in the continuous improvement process.

Methods

Positionality of the researchers

Who we are drives what we do and the questions we ask. I Brandi am an advocate for Improvement Science as a methodology for scholar-practitioners seeking to improve educational equity and outcomes. The research questions in this study stem from my desire to serve as a “critical secretary” for those doing counterhegemonic work (Apple, 2016). I identify as a critical pragmatist, seeking to not only answer the question of what works, but also what is just—and what alleviates the plight of the marginalized. While the critiques of Improvement Science are loud and warranted, I believe it is the responsibility of improvement scholars to address shortcomings and unearth new ways of engaging in improvement work that are liberatory and revolutionary. I enter this work as a Black woman, EdD faculty member, and as a mother of Black children navigating a school system that has not always been kind to them. When writing a book on Improvement Science, I spoke in depth about avoiding deficit ideology, and I have a vested interest in learning how scholar-practitioners are avoiding that pitfall.

As a Black woman and an educator, I Rebecca feel a particular connection to and concern for the outcomes of historically marginalized students who face deficit ideology that limits their educational opportunities and experiences. While system change is a collaborative effort, I believe that lasting transformation begins at the individual level through critical self-reflection and renewing one’s mind. I have first-hand experience developing and implementing a Dissertation in Practice as a doctoral student in the EdD in Educational Leadership program at Western Carolina University. I firmly believe that scholar-practitioners can leverage the power of Improvement Science to reframe problems of practice as matters of systemic inequity and injustice, which places the responsibility for change squarely on the shoulders of educational institutions and their agents.

I Augustine bring to this work my identity as a Black male PhD student in Teaching and Learning, informed by my own experiences navigating educational systems that have not always prioritized equity. My overriding goal is to contribute to a scholarship that challenges systemic inequities as a means to transform education and improve student outcomes. My epistemological stance is grounded in a critical pragmatic orientation that centers on experiential knowledge and values research as a tool for disrupting inequities and informing action. While I acknowledge the role of traditional research, I believe that research should focus on addressing specific problems and prioritize issues of equity in education in order to bridge the gap between theory and practice. Who we are informed our approach to this work. Who we are led us to ask the following questions:

1. How do EdD scholar-practitioners implementing Improvement Science Dissertations in Practice (ISDiPs) define and identify deficit mindsets in their continuous improvement process?

2. What mechanisms do they use to address deficit perspectives among stakeholders throughout the CI process?

Case study design

To answer this question, we conducted a qualitative multi-case study, examining the improvement process and the particular phenomenon of deficit mindset within the continuous improvement process. Yazan (2015) discusses in detail the varied approaches to case study research, and our work is informed by Merriam and Yin. A multiple case study design, as a type of qualitative design, involves the in-depth examination of multiple bounded cases to explore a specific phenomenon or context within its real-life setting (Merriam, 1998; Yin, 2018). Guided by Merriam’s (1998) conception of case studies, we argue that the case study approach is appropriate because case studies are particularistic, descriptive, heuristic, and inductive. The phenomenon we sought to understand was deficit ideology within the improvement process. Yin (2018) discusses the benefits of using multiple cases and explains that to identify multiple cases, scholars must use replication logic, not sampling logic. He states that each case is analogous to a separate experiment. After the analysis of each individual case, the theory generated from the case should be revised. The cases selected for this study all used Improvement Science to address educational inequity. Thus, they all used a structured methodology involving root–cause analysis, development of a localized theory of improvement (often depicted with a driver diagram), iterative plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycles, and collaborative data inquiry to drive systemic change (Bryk et al., 2015). We used two primary data sources: documentary evidence from dissertations in practice and interviews. Participants in this study were recent graduates of an equity-focused, Carnegie-inspired EdD program that required a dissertation in practice (DiP) where doctoral candidates use Improvement Science to address a problem of practice (PoP) (Perry et al., 2020). In their text on the dissertation in practice, Perry and colleagues differentiate DiPs from other dissertations, explaining that:

DiPs are different from traditional dissertations in that they focus on addressing PoPs through applied inquiry. [DiPs] focus on designing and implementing changes that improve or solve PoPs. That is, a change idea is implemented, data is collected on the results of the implementation, and decisions are made about how to move forward for continuous improvement (Perry et al., 2020, p. 37).

Unlike traditional dissertations, which address a gap in the literature, dissertations in practice provide documentary evidence of the process employed by a scholar-practitioner. The published, publicly available DiPs served as documentary evidence.

Finding scholar-practitioners engaging in equity centered improvement

While recognizing that there are a variety of approaches to continuous improvement, we narrowed the scope of participants by examining EdD graduates who employed Improvement Science in their dissertations in practice. In part due to the support of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching’s network improvement communities and the Gates Foundation’s networks for school improvement, Improvement Science has established a significant lane as an improvement methodology for practitioners. Another lever for knowledge mobilization around Improvement Science has been the EdD (Doctor of Education) and the dissertation in practice (DiP). The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED), founded in 2007, has become a consortium of over 150 institutions, with the mission of “transform[ing] the advanced preparation of educational professionals to lead through scholarly practice for the improvement of individuals and communities” (CPED, 2022). While not all EdD programs are members of CPED, CPED has changed the discourse on what a professional practice degree in education should do. As CPED advances the idea of a dissertation in practice (DiP) as the culminating experience for the EdD candidate, it names four methodologies that scholar-practitioners may embrace in the DiP: action research, Improvement Science, evaluation, and design-based research. Within Doctor of Education (EdD) programs, particularly those employing Improvement Science Dissertation in Practice (ISDiPs), CI is not merely methodological; it is deeply ideological. Hinnant-Crawford et al. (2023) argue that ISDiPs challenge traditional research accountability structures by placing scholar-practitioners in direct engagement with community-defined problems.

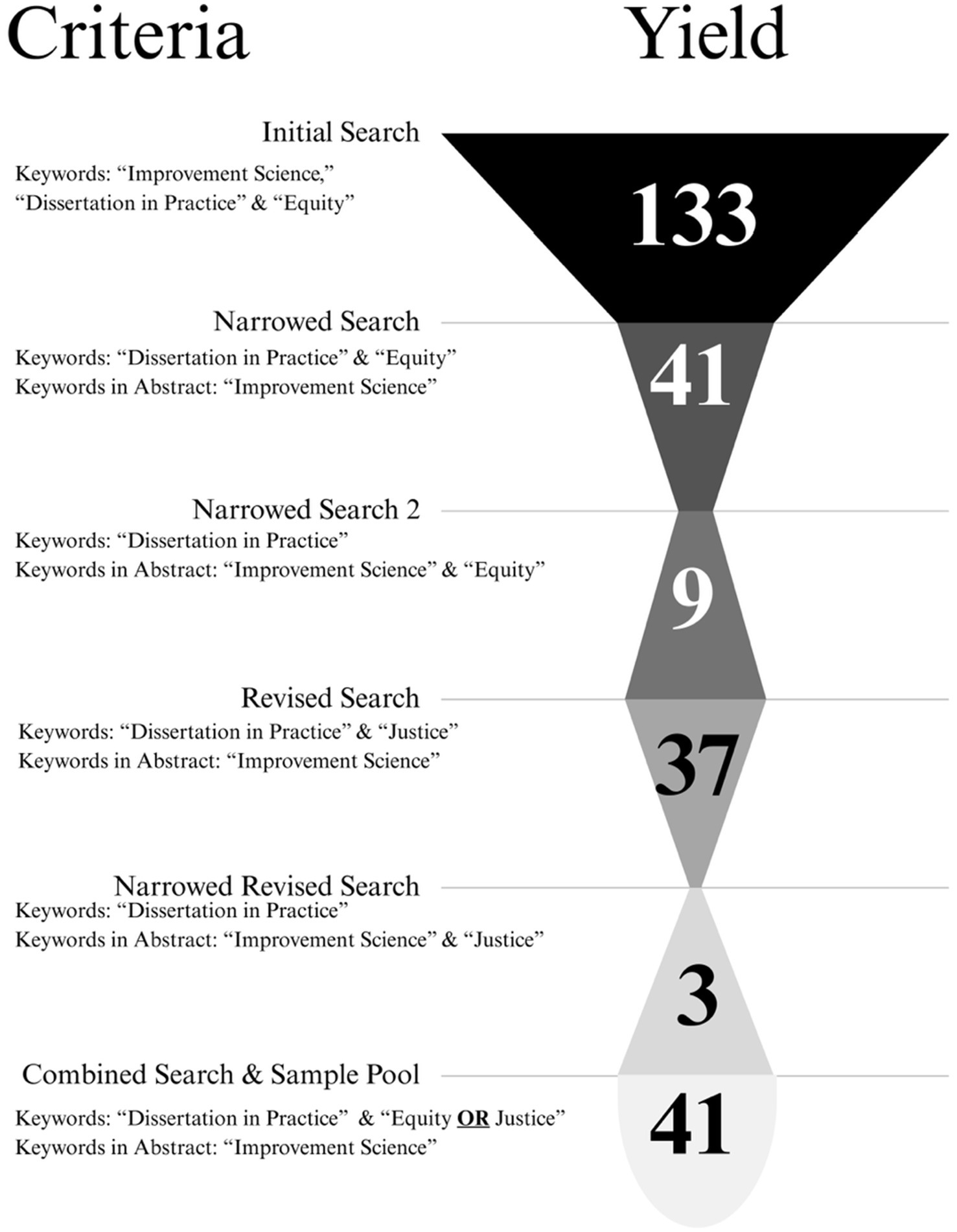

To find EdD graduates, in January 2023, we used ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database to identify dissertations (and authors) with knowledge of leading improvement and navigating deficit ideology in the process. We only searched for dissertations published after 2015, to coincide with the publication of Learning to Improve, a monumental text introducing Improvement Science to education. We used several combinations of search terms. Our funnel chart (Figure 1) illustrates how our pool of potential participants changed based on our search terms.

Our initial search using “Dissertation in practice,” “Improvement Science,” and “equity” yielded 133 dissertations. From the initial pool of 133 dissertations, we narrowed the search by adding the criteria that “Improvement Science” be in the abstract. This reduced the sample to 41. When both “Improvement Science” and “equity” were in the abstract, that narrowed the field to nine. We did a similar search with “justice” in place of “equity.” Searching with “justice” as a keyword and the requirement of “Improvement Science” in the abstract yielded 37. A subsequent search with “justice” and “Improvement Science” in the abstract yielded three. Our final search used “dissertation in practice” with “equity” or “justice” and “Improvement Science” in the abstract, giving us an initial pool of 41. There was considerable overlap between the searches; we found that everyone using the word “justice” also used the word “equity”.

Document analysis

In late January of 2023, we did some preliminary screening of the dissertations in practice before in-depth document analysis. Our process was quite similar to Bowen’s (2009) suggested approach to document analysis: “skimming (superficial examination), reading (thorough examination), and interpretation” (p. 32). Our preliminary screening, or skimming phase, determined if the improvement was led by the author, if it sought to improve outcomes or experiences of traditionally underserved communities, and whether there was evidence of using Improvement Science tools or processes (i.e., driver diagrams, root cause analyses, cycles of inquiry). We eliminated three because the author was not the individual leading the improvement.

We developed a Qualtrics protocol to guide our interrogation of the remaining dissertations, and document analysis commenced in February 2023. Knowing the elements of a dissertation in practice, we began by capturing common elements using direct quotations for entries detailing the purpose statement and problem of practice. We included a multiple-choice item asking if there was a substantive relationship to educational equity, along with a follow-up open-ended item that required direct quotations of evidence of equity if “yes” was selected. As a team, we internally defined equity as initiatives designed to impact (1) the opportunity to learn of minoritized or underserved populations and (2) the experience of minoritized or underserved populations in educational institutions. The form allowed us to take specific notes (and add direct quotations) about problem definition, theory generation, intervention selection, and intervention implementation and testing (common procedures in Improvement Science protocols). In addition, because Improvement Science heavily uses visual tools, the form allowed us to capture screenshots of problem definition tools (i.e., fishbone diagram), theory tools (i.e., driver diagrams), and any images depicting cycles of inquiry or implementation timelines. Our final item was space for reactions and judgments, so we could acknowledge our responses to what we were reading while keeping that response separate from the documentary data to be analyzed. While we used their dissertations as evidence, we did not use any direct quotations from the dissertations to protect the identities of the participants.

Dissertation quality and outcomes

Our inclusion and exclusion criteria did not include a barometer for quality, and there was variation in the quality of the dissertations. While we had two dissertations from the same institution, quality seemed stable within the institution, suggesting some variation might be due to institutional expectations. The quality also varied over time, with earlier dissertations using Improvement Science not being as sophisticated as some of the more recent dissertations.

Variation in quality was more about the presentation of the work than the work itself. Some authors provided extensive background literature, whereas for others, the review of literature was scantier. Some provided copious details on their decisions throughout the improvement process, whereas others gave more of a high-level overview. Some dissertations reflected multiple cycles of inquiry, while others only included a single cycle. This is why the interview process was so essential to allow us to fill in the gaps of the processes that were not clear in the manuscripts.

While the dissertations addressed a problem of practice, we intentionally did not use success as an inclusion criterion. Improvement is designed to increase organizational learning, and even when one does not achieve their aim, learning happens. Most of the cases included here showed some improvement (or evidence that improvement was going to happen). Yet, all of the dissertations employed Improvement Science, all documented work lead by the author, and all sought to remedy institutional harm to minoritized or marginalized individuals.

Interviews

After a preliminary document analysis, we built a database of the dissertations and proceeded to find contact information for the authors. We began with an initial internet search or tried using institutional emails (if they named their institution in the DiP). We also used a premium LinkedIn account that allowed us to send interview requests to individuals who were not our “connections” on LinkedIn. In two cases where we could not locate an author, we contacted the dissertation chair and asked the chair to forward our request to the author. Approximately half of those invited agreed to participate; however, scheduling conflicts led to an initial sample of 7 (with interviews conducted in March of 2023) and a final sample of nine, when scholar-practitioners received an additional invite for an interview in August of 2023 (and two accepted).

Bowen’s (2009) work on document analysis states clearly that documents “can suggest some questions that need to be asked,” and in the sequential fashion we used the initial analysis from the documents to develop the interview protocol (p. 30). The semi-structured interview protocol consisted of five thematic sections: 1. background and rapport, 2. problem identification, 3. theory development and solution ideation, 4. intervention implementation and testing, and 5. reflection on the process overall. In the introductory section, we asked participants directly, What do you know about deficit perspectives or ideologies? and How would you define deficit thinking to a lay audience? Each subsequent section had one main stem item that began with “Tell me;” for instance, in problem definition, the item said, “Tell me about your process for defining your problem of practice.” That stem item had multiple follow-up questions, including

1. Who was involved with defining your problem? How were people recruited to participate?

2. In what ways, if any, were data used in defining the problem?

3. Who would be the primary beneficiary if this problem was addressed?

4. Were there any instances where deficit perspectives were present during the defining of the problem of practice? If so, how were they identified and addressed?

While each stem item had 3–4 follow-up prompts, we used discretion on which ones to use based on what was shared in response to the tour question “Tell me about.” Understanding the impact of mindset on decision-making, our protocol was designed to get specific insights on each phase of the improvement process where different types of decisions are made (i.e., what problem to address, what change to try, what data to collect, what audience to share data with). During recruitment, some participants asked for the protocol in advance of the interview, and it was provided via email. Most interviews lasted between 45 and 75 min; no interviews exceeded 90 min. Interviews took place via Zoom and were recorded using Zoom’s transcription feature. The transcripts were verified and cleaned by the research team.

Data analysis

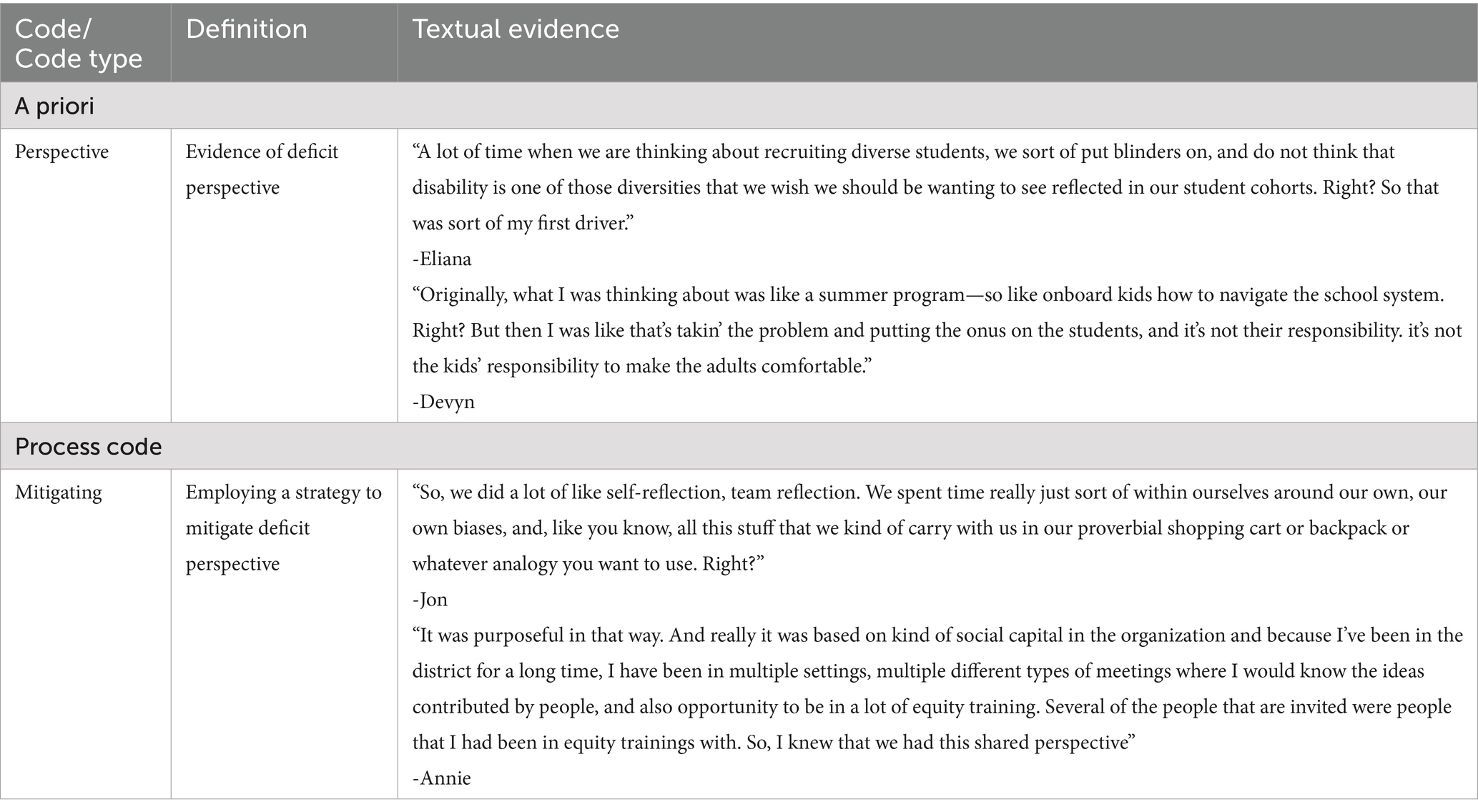

After the interviews were conducted and transcribed, we coded both interviews and document analysis notes using both a priori and inductive coding strategies. Our a priori codes were guided by key Improvement Science processes such as problem definition and theory development, as well as definitions or evidence of deficit perspectives. Because mindsets are often most evident during decision-making, we paid particular attention to decision-making inflection points throughout the improvement process, such as problem definition and change idea selection. We began with a priori codes related to stages so we could identify mitigation strategies at different steps of the improvement cycle. We also used process coding, which is used to “connote observable and conceptual action in the data,” to identify deficit-mitigating actions (Miles et al., 2014, p. 66). Our first round of coding consisted of multiple rounds of independent coding followed by discussions to calibrate and ensure internal reliability among our research team. Table 1 provides an illustrative example of our a priori and process codes.

During second round coding, we began with the patterning process by examining what common actions or processes emerged among our first-round codes. Examining “perspective” as well as the stages of the improvement process (i.e., problem definition) as a condition, we sought to identify responses to the condition. We paid close attention to decision-making points within the improvement process. We wanted to document not only what decisions were made but also how decisions were made and the thought process leading to particular decisions. We identified four actions that appeared repeatedly across the cases: composing intentional teams, building team capacity, employing critical theory, and involving those impacted.

While we did not use dramatological coding as a main approach during cycle one, we did have a keen interest in who the individuals making decisions throughout the improvement process were. We noted patterns in team composition and the formation of teams; particularly, who was on the team and whether team membership was relegated to educators, parents, community members, or included students as well. Because these were dissertations in practice, often the author was the primary decision-maker. However, when the author led a team (as prescribed in guidance on engaging in improvement science), we wanted to capture how input was gathered, information was shared, and how power was distributed. Two themes emerged that were actions related to the people involved. We differentiated composing intentional teams from involving those impacted. Improvement teams, leadership teams, inquiry teams, or implementation teams were groups of individuals convened multiple times to lead or consult on the improvement work. Involving those impacted described actions that included the direct beneficiaries of the improvement or the individuals who bore the burden of implementing the change; these individuals were not necessarily consistent members of an official improvement team.

The aims of the research within these dissertations were to benefit individuals in the margins. One common element around theory began to emerge in any analysis of the dissertation documents. In addition to the theory of improvement, many of the authors used other theories or conceptual frameworks to inform their problem definition, their analysis of the system, or their development of an intervention. The bulk of these theories or frameworks were critical in nature, as Muhammad (2020) explains, criticality is the “ability and practice of naming, researching, understanding, interrogating, and ultimately disrupting oppression (hurt, pain, or harm) in the world” (p. 13). Theories and frameworks employed by the scholar-practitioners that were axiologically rooted in the disruption of oppression were coded as employing critical theory. For example, one intervention was guided by culturally relevant pedagogy; this was classified as critical because, as Milner (2017) explains, both critical race theory and culturally relevant pedagogy recognize the systemic and permanent nature of racism in society (and in classrooms), and while CRT is an analytic framework, CRP translates the insights from the theory into pedagogical practice.

Building team capacity was a relatively straightforward category. It included actions that centered on professional learning and group norming.

During the first and second rounds of coding, we also re-examined the full text of the DiPs for the purposes of triangulation and elaboration, in an iterative fashion going from interview data to documentary data. The back and forth between interview data and documentary evidence happened during April of 2023 after the first round of interviews, and again in late August and September of 2023, after the second round of interviews (where we increased our sample by two additional cases). To check the validity of our work, we engaged in member checks to ensure descriptive and interpretive validity. Portions of this manuscript were shared with the participants, where they were asked to comment, critique, challenge, or confirm what was written. The participants are scholar-practitioners; however, we used pseudonyms to protect their identities and no institutional names.

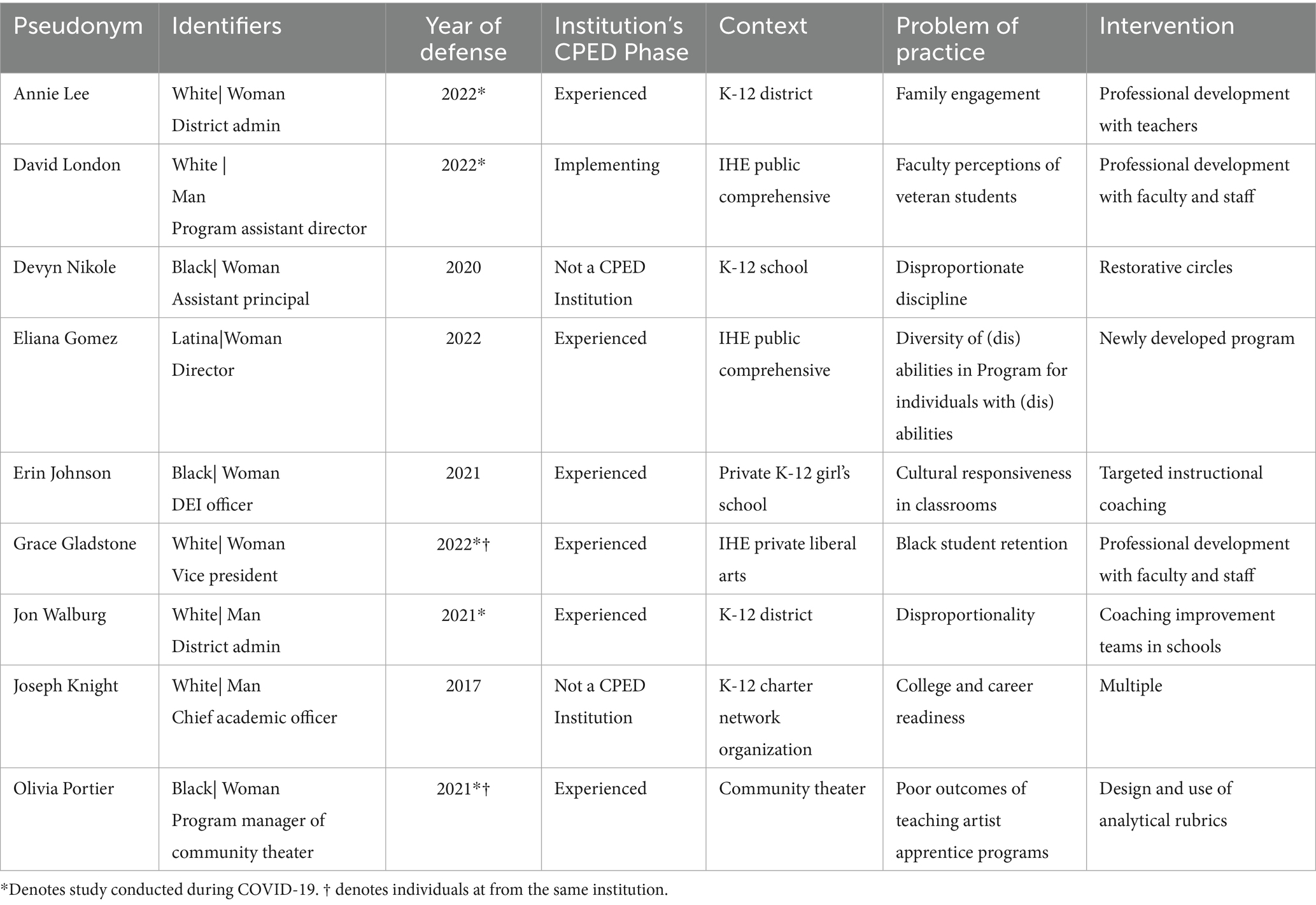

The cases

This analysis presents data from nine individual cases of scholar-practitioners using Improvement Science to address a problem of practice. The cases show scholar-practitioners in K-12, higher education, and community organization settings. These cases represent a diversity of leadership positions at different levels of the organization. Five of the nine scholar-practitioners identified as white; three identified as Black, and one as Latinx. Six of the scholar-practitioners were women, and the remaining three were men. Most (7) of the scholar-practitioners attended CPED institutions. Two respondents were graduates from the same institution: Grace Gladstone and Olivia Portier, but they were in different programs and different cohorts. Table 2 provides an overview of the nuances of each case.

Findings

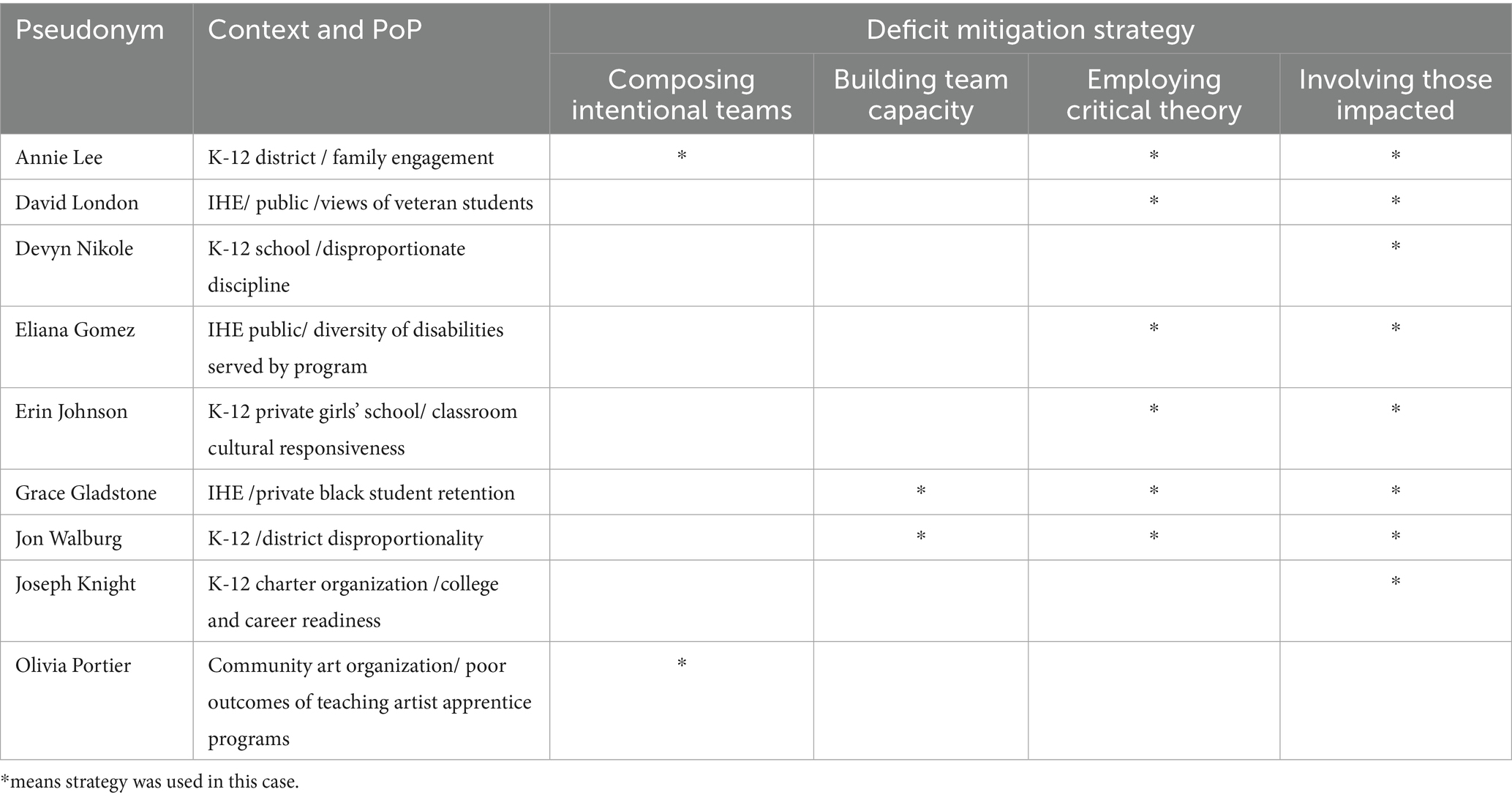

The findings of this study are presented in the order of the research questions. First, we present findings on how scholar-practitioners conceptualize and define deficit mindsets (RQ1), then on the strategies they employed to mitigate those mindsets in CI work (RQ2). The scholar-practitioners conceptualized deficit mindset as a cognitive framework that is used to explain and justify inequality based on group membership, especially group membership related to race and social class. The mitigation strategies identified in the cases are presented in ascending order in which we found them in the cases, from least employed to most frequently employed: composing intentional teams (2), building capacity (2), employing critical theory (6), and involving those impacted (8).

Defining and recognizing deficit mindset

Scholars have written about the danger of deficit ideology in problem definition and solution ideation, where improvers seek to fix people rather than systems. The dissertation-in-practice cases analyzed in this study acknowledged deficit mindset as a barrier that had to be overcome in order to accomplish meaningful equity through continuous improvement (Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022).

Joseph, a chief academic officer seeking to improve college and career readiness within a charter network, described deficit mindsets as pervasive. Joseph was one of the six respondents who used the language of “mindset” in his responses. Explaining deficit mindset as common, Joseph expounds:

Especially for the overwhelmingly white teaching force to see kids of color or kids from low-income backgrounds and think, well, the problem is their culture, the problem, the reason why our kids aren’t doing well in my class. Oh, well, it’s because there’s some problem with their parents or some problem with their family. There’s some problem with their community. I think [deficit mindset is] a very unsurprising impulse that people have, that you kind of have to like name, and then think about how to overcome it.

In Joseph’s description of deficit mindset, he nods to the representativeness heuristic, beginning his remarks with the demographic differences between educators and the students they serve. In his analysis, the educators see themselves as different and distinct from the children and their communities, and therefore it must be those differences that lead to differential outcomes and not the practice of schooling.

Jon, whose position was most similar to Joseph’s, and who was also addressing a problem across multiple schools emphasized deficit mindset as a root cause of his problem of practice. In his dissertation, Jon argues deficit mindsets are evident in the interpretation of quantitative data on student achievement and in rationalizations for the phenomenon of disproportionality that stem from stereotypes and low expectations for students of color. Annie, the final district/network administrator, listed deficit-oriented beliefs about families on her fishbone diagram—indicating it was a root cause to her problem of practice around family engagement. In her interview, Annie explained, “there’s research that even explains teachers who would never have deficit beliefs about kids will have them about their families.” Illustrating that part of her knowledge about deficit mindsets derived from scholarly literature from either coursework or her own research.

Others recognized that addressing deficit mindsets began with changing their own frame of reference. Grace, a senior administrator at a private liberal arts college, explained she was unaware of her own deficit perspectives prior to entering her EdD program. Grace recounts, “Deficit perspective is something that I did not know a lot about when I entered my grad program, and I had an advisor who heard a lot of deficit language coming out of my mouth. As I was grappling with what my problem of practice would be.” Grace notes a combination of mentoring (and challenging) from her advisor and coursework helped modify her own mindset and enabled her to recognize it elsewhere.

The scholar-practitioners all described deficit mindset as locating problems in people rather than in systems. Annie said she used a Buddhist parable to explain deficit ideology to people in her organization. Annie said, “There’s this Buddhist parable that I like that says if seed of lettuce does not grow, we do not blame the seed. It’s the environment. It’s the conditions. And so if we are not getting the outcomes that we would want for our students. We cannot blame the students or their families. We have to and blame the environment and the conditions.” Most conceptualizations of deficit mindset from the scholar-practitioners centered on common identity markers that lead to marginalization, such as race and class; however, several respondents operationalized deficit mindset beyond race and class.

Beyond race and class

While Joseph and Jon spoke specifically to race and class fueling deficit mindset, Erin spoke about deficits in terms of dominant and subordinate identity groups (identities privileged or marginalized in societies). Erin explained that, at its core, deficit mindsets are “centered on viewing that there’s only one way to be, and it’s the dominant… like the dominant group’s way, as the only and the best way to be and anything outside of that is viewed as a deficit.” She juxtaposes her definition of deficit mindset with a preferred asset-based approach. Erin expounds:

We have so much cultural capital in this increasingly diverse society. And there’s no one way to be. There’s no one way to live, and instead of trying to put everyone in the box and seeking the white gaze, I think we are better as a society, as a community, whenever we view those differences as assets and ways to make us all better.

Morrison (1993) popularized the concept of “White gaze,” which assumes the default audience for literary work is white; the term has been expanded to mean the standard or the default is White. Sensoy and DiAngelo (2017) discuss dominant and subordinate identity categories across a number of identity markers, including race, economic status, gender, gender identity, religion, ability, country of origin, and sexuality.

David expanded the notion of deficit perspectives even further beyond those traditionally viewed as marginalized to include the perspectives post-secondary faculty hold toward veterans. According to David, faculty assume veterans are less capable than traditional students, failing to realize that the reason many enlist is for the GI educational benefits. As the director of a student success office that supports veterans, David explained:

There’s a stigma that exists that they all have PTSD. They are all sitting in the back of the classroom waiting to snap. They’re gonna be that ticking time bomb, and I’ve had professors call me ‘so I’ve got a veteran in my class. Is there anything special I need to do for that person. So can you explain what we need to do that’s special? How do I need to be prepared? Do you have law enforcement on hand? Well, what happens if they snap?’

David said the deficit perspectives about veterans are often compounded by intersectional identities.

Only one participant, Eliana, was not familiar with the terminology deficit perspective, deficit ideology, or deficit thinking. When asked what she knows and how she would define it, she responded promptly, “I do not; I cannot. I’m not informed enough.” Yet, as we continued to talk about her dissertation work, she described the presence of deficit mindsets during the improvement process, even though she did not use the language of “deficit” to describe it.

The scholar-practitioners in this study conceptualized deficit mindset as perceiving individuals from different socially constructed groups as deficient and attributing those deficiencies to group membership rather than to opportunities afforded to the group. While the majority focused on race and class, some acknowledged that deficits can be applied to additional identities, such as Annie speaking about how educators would sometimes discuss the deficits of families but not apply the same framework to their students. Their knowledge around deficit mindset came from a variety of sources, including coursework, mentoring, equity trainings, and scholarship.

Mitigating deficit ideology in improvement initiatives

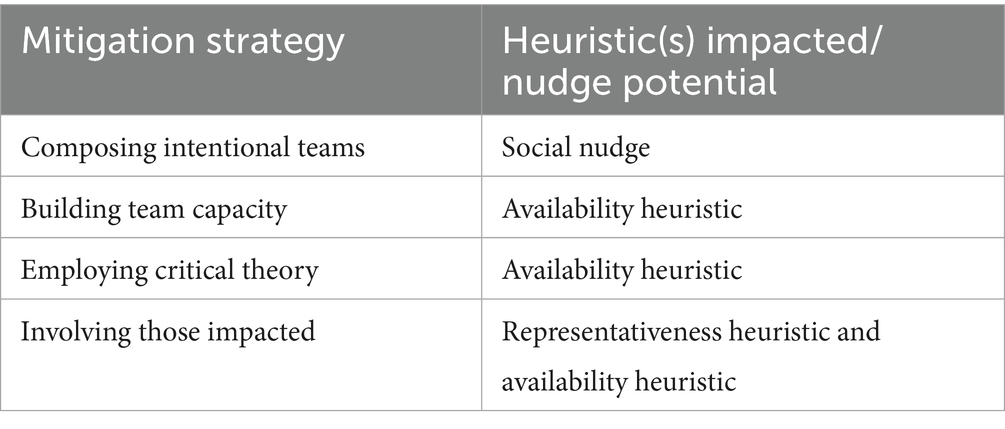

While most scholar-practitioners acknowledged the existence of deficit perspectives and used the language of “deficit mindset” or “deficit perspective” in their responses, their approaches to mitigating the effects of deficit perspectives varied. Collectively, through their manuscripts and interviews, four common strategies emerged: intentional team composition, team capacity building, using critical theory, and involving those impacted (see Table 3). In the matrix below, we illustrate every strategy employed by each scholar-practitioner. Each of the four strategies was employed by at least two of the scholar-practitioners. These strategies emerged from our coding of their manuscripts and interview transcripts. In our detailed findings by strategy, we selected illustrative cases that were examples or non-examples. For instance, while two scholar-practitioners composed intentional teams, one scholar-practitioner explained why that intentionality was not necessary in her context, so we discussed all three cases in that section.

Composing intentional teams

Improvement is not meant to be a solo adventure, though often one finds that in DiPs, improvement initiatives are more individualized because of the nature of the dissertation process. Often, the dissertation does not reflect the work of a team but simply that of the scholar-practitioner. While Langley et al. (2009) suggest both a design team and an implementation team, individuals often do not go into detail about team composition or membership. Two of the nine cases illustrate intentional design of the team as a strategy to mitigate deficit ideology.

In her dissertation, Annie discussed the collaborative inquiry team that would be at the center of her improvement work addressing family engagement. The team was made up of district leaders, school leaders, teachers, and family members. In her interview, Annie explained, when creating the team:

I brought to the table people who I already knew were familiar with the family engagement practices in our district and had an equity lens. I really knew I brought together people in my organization who I knew were not going to blame the lettuce in order to conduct that [root cause analysis]. And now that fishbone analysis… included some assistant principals, some principals, some central services leaders, including some [working] in family engagement, some in equity, and some in school improvement.

Annie was quite intentional in building her team, as her DiP spoke in detail about how deficit cognitive frames shape the way educators talk about families. Because of her timetable, she said she needed her team to already be on the “same page”.

Olivia was in a community organization, a community theater, that served a predominately Black community. The theater is a member of the League of Resident Theaters (a national network of 81 theaters in 30 states), runs eight shows annually, employs 20 people, and has an operating budget of approximately 4 million dollars. In addition to show business, the education department of the theater runs nine programs that serve over 2,000 students annually (students ranging from preschool age to octogenarians). While the theater employs teaching artists (artists who teach their craft, such as Olivia), it also has an apprenticeship program for cultivating teaching artists. As the education program manager, Olivia worked directly with the education director to narrow her problem of practice. During the improvement work she did for her dissertation, she explains, “I wanted to bridge the gap between all quality arts programs and all the students that did not have the access by myself. I learned that as an improver that would be way too much. I did not have a team of researchers, I did not even have a larger group of co-worker[s] and that is what was in my sphere of influence”. Olivia expounded in her interview that the best conservatories were highly Eurocentric in their curricula, which leads to a level of erasure of artistic contributions from other communities. As her classically trained apprentices faced theater classes full of minoritized children, they would:

Come in there with that Eurocentric training, and with that mindset of like, I know how to be an artist. But you do not look at the people who you are in the classroom with the eyes of a person who’s ready to like to come with it! With them. Like be on the same page and be able to know you know where they are coming from, who they are, and how, or to be able to.

She speaks of the cultural dissonance that would arise between the theater’s clientele and the apprentices. This again is evidence of the representative heuristic that can influence mindsets—in this case, the mindset of the teaching artist apprentice. As she designed her intervention and further defined her problem of practice, she relied on individuals outside of her organization, in other cities, running programs similar to hers—and they became her team and an instrumental feedback loop. Olivia recounts after talking to her director:

Then I talked to like peers, colleagues that were not actually at the organization, but had similar programs, or had worked with a number of teaching artists as well, like I have a colleague of mine… she’s in Pittsburgh, and she’s the executive director of a dance company. I talked to her and she manages teaching artists as well, and it was the same kind of similar kind of conversations being had, so that’s kind of how I how I narrowed it down, just kind of talking within my organization. And then also with colleagues around [the country]…

Olivia said that of those she included to help guide her thinking outside her organization, she made sure they were serving similar demographics to her community theater.

While Annie was intentional about selecting members of the team who had background knowledge in equity and shared values, Eliana did not have to be as selective because her community was generally very supportive of individuals with disabilities. Eliana clarified, “I’m really fortunate [because] of where we are located. That’s what we do. We serve people with disabilities and our in our community. So there is sort of this welcoming of ideas, of anything that we can do that is going to improve outcomes for people with disabilities.” Eliana’s case shows that the intentionality of building your team, like Annie or Olivia, is not necessary in every context. Other scholar-practitioners, such as David, said he approached the task alone, and the improvement initiative was his initiative instead of the brainchild of a team. Jon’s team was formed before he was hired, so he had no say on who was on the team; therefore, his approach differed.

Approaches to team composition varied across the cases. Annie selected individuals within or adjacent to her organization that she felt would minimize the likelihood of a deficit mindset in root cause analysis procedures. Olivia, working in a more skeletal organization, sought to create a team of individuals in her sector but beyond her organization, likely facing similar problems of practice. Both Annie and Olivia sought individuals to inform their improvement work who had shared experiences—either shared background knowledge and professional learning (Annie) or shared practical experiences (Olivia). In contrast, Eliana believed everyone in her university and surrounding community was supportive of the beneficiaries of her improvement work; therefore, team intentionality was less of a priority.

Building team capacity

In addition to team composition, some scholars built the capacity of their teams. Again, two of the nine cases used capacity building to mitigate deficit ideology, and one case suggested that capacity building took place prior to her beginning the initiative. In the case of Annie, her district had already conducted equity capacity building, and experiences with colleagues in those professional learning opportunities helped her decide who was prepared to be on her team. Annie remembers:

Several of the people that I invited were people that I had been in equity trainings with. And so I knew that we had this shared perspective and it was to come combat deficit ideology… blaming students or their families were not going to help in creating an improvement process. But I needed to have the people who would already be there [with an equity mindset] in order to do an effective analysis [of the problem of practice].

Other scholar-practitioners incorporated capacity building as part of their planning phase of the improvement initiative. Such was the case with Grace and Jon.

Grace admitted she had some learning to do when it came to deficit perspectives, and she was not surprised that her colleagues had learning to do as well. She recounts planning to do her capacity building in person, but with COVID still lingering and two winter storms, she held all of her capacity building sessions online. She explained:

We started with language. I knew… we were not all on the same page even in terms of understanding language of, like, equity and race. What did we mean by race? Who were our underrepresented minoritized students at [private liberal arts college]? So we just started with some basic language and then I moved into a presentation on Bensimon’s cognitive frames. The diversity, deficit and equity-mindedness. We used a lot of tools so that people could get into small groups and really wrestle with ideas.

While online, Grace said the capacity development was full of real-world scenarios where her colleagues could think through how the new ideas played out in their university setting. The content of her capacity building directly targeted deficit cognitive frames, using the work of Bensimon.

Since Jon was hired into his team, his dissertation details the significant time he spent building the team’s capacity and cohesion. They took batteries to identify strengths and weaknesses, developed norms and protocols for their interaction, and even talked about their varied love languages. In the manuscript, he admits that this team-building and capacity-building was time-consuming but necessary. In addition to learning about each other and how to function as a team, the capacity building also covered specific content to orient the team to tackling the task of disproportionality.

In his interview, Jon said as a team, “we also talked a lot about the way racism shows up in education, where you know bias shows up, and how we would best work to dismantle those things within schools, interrogate where that stuff landed within ourselves and within the education system.” Jon’s emphasis on interrogating where things “landed within ourselves” shows his capacity building intended to influence mindset. Jon’s team also built in a structure for building capacity, making Fridays what he called “sacred days,” where they shared successes and failures and served as consultants for each other. Jon frequently said his approach to the team was uncomfortable and even received pushback at times because this was not the norm in the district; yet he found the interactions to be effective, and his team was prepared when going out into schools to help facilitate their improvement cycles.

Capacity building in Annie, Grace, and Jon’s context had content explicitly directed at mindset. The capacity building of these teams was not generic. Annie’s team experienced “equity training” prior to the work she described in her dissertation, and Grace’s team explored “deficit vs. equity-mindedness.” While Jon’s capacity building was more comprehensive and used traditional approaches to team building, his description of the work suggested he had his team examine systemic oppression—specifically racism—within the organization and within themselves, suggesting metacognitive consequences for the capacity building.

Employing critical theory

Often, Improvement Science is heralded as a more practical approach to research, especially for scholar-practitioners seeking to address problems of practice instead of filling gaps in the literature. As they have articulated context-specific theories of improvement or theories of action, some may question the extent to which academic theories inform their work. Six of the scholar-practitioners used critical theory within the DiPs. The cases here illustrate how critical theories can provide guardrails against deficit ideology within the improvement process. Our cases showed people using critical theory to frame the study, inform the intervention, build the capacity of the team, and guide analysis of the data.

Early in her dissertation, Annie wrote that she decided to use CRT to frame her research because of its emphasis on the perspectives of the marginalized, and she wanted the perspectives of minoritized families in her district to be at the center of the work. Noting her positionality as a white middle-class woman who was trying to improve the student experience of minoritized youth, she recognized the critical importance of evaluating the effectiveness of her work with the voices of those she sought to impact. As her work was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, she reached a point where she noticed a great deal of her feedback from parents was from white parents. At that point, she also decided to pull in critical whiteness theory as an analytical aid to ensure she interpreted the insights of white parents with a critical lens. She used CRT to frame her study and Critical Whiteness Theory in the analysis of parental focus groups giving feedback on her intervention.

David also framed his research using veteran critical theory—a theory with 11 tenets that speaks to the normality of civilian privilege in institutions of higher education. As he designed his intervention, a professional development series for faculty and staff, veteran critical theory informed the content of the professional development. The purpose of his intervention was to build the capacity of university faculty to be responsive to the needs of military-connected students and to help faculty understand the transition from military to collegiate life. The tenets David used privilege the counternarratives of veterans, acknowledge the deficit perspectives widely held about veterans, and recognize the various forms of oppression and marginalization (including microaggressions) faced by veterans. David explained that one of his veteran students shared how a professor asked him to stand in class and explain why he chose to invade another country. VCT allowed him to illustrate the many ways veterans are marginalized even on veteran “friendly” campuses.