- Hokkaido University of Education Asahikawa, Asahikawa, Japan

Introduction: Bullying is a significant issue that harms children’s health and infringes on their right to education. Understanding the mechanisms of bullying, preventing it, and implementing appropriate interventions are essential for education. Notably, not only the victims and perpetrators but also the bystanders around them play important roles in bullying situations. This study examined the relationship between bullying bystanders’ multidimensional just-world beliefs and their attitudes and behaviors when witnessing bullying.

Methods: A vignette-based online survey was conducted with 400 Japanese middle school students (Mage = 13.2, SD = 0.91). The questionnaire required the students to respond independently.

Results: The analysis showed that intrinsic just-world beliefs were associated with positive attitudes and behaviors toward bullying victims, whereas ultimate just-world beliefs were not. It was found that higher ultimate just-world beliefs were not only related to stronger intentions to mediate bullying but also, to a greater tendency, to blame the victim and a lower likelihood of recognizing bullying in cases where it was witnessed multiple times.

Discussions: Multidimensional just-world beliefs predicted both pro-bullying and anti-bullying attitudes. The findings add substantially to our understanding of the relationship between just-world beliefs and bystanders’ behavior and attitudes, providing novel insights into the understanding of bullying behavior.

1 Introduction

Bullying is defined as intentional and repeated aggressive behavior directed at a relatively weak individual and negative responses from those around them (Olweus, 2013; UNESCO, 2024), with prevalence rates estimated to 20% across OECD countries (OECD, 2023). School bullying is a universal issue that threatens children’s school life and deprives them of opportunities to participate in educational activities safely. Furthermore, it has well-documented short-term (e.g., Reijntjes et al., 2010) and long-term (e.g., Takizawa et al., 2014) effects on children’s health. For example, a meta-analysis of 18 longitudinal studies revealed that victimization predicted further internalizing problems (Reijntjes et al., 2010). A British cohort study by Takizawa et al. (2014) also showed that victimization at childhood affected mental health and suicidal ideation in middle adulthood. Understanding the mechanisms of bullying, implementing preventive measures, and establishing appropriate interventions are crucial in education.

To comprehend bullying, research has extensively focused on the characteristics of both perpetrators and victims. For instance, a meta-analysis summarizing the associations between bullying involvement and individual difference variables indicated that bullying perpetration is associated with higher levels of externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors, as well as lower levels of social competence and self-perception. In contrast, victimization is characterized by opposite patterns (Cook et al., 2010). Another meta-analysis examining the association between bullying roles and the Big Five personality traits found that bullying perpetration was related to higher levels of neuroticism and extraversion and lower levels of agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness. In contrast, victimization was associated only with higher levels of neuroticism (Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias, 2015). As bullying typically occurs in the presence of individuals other than the victim and perpetrator, group dynamics play a significant role in shaping bullying behaviors (e.g., Salmivalli et al., 2021). While bullying can be understood from the perspectives of victims and perpetrators, it can also be analyzed from the perspective of bystanders.

Bystanders are students who witness bullying incidents (Polanin et al., 2012), and they can be categorized into several subtypes. These include outsiders, who passively observe bullying without intervention; defenders, who attempt to stop bullying or console the victim; and reinforcers, who encourage bullying or actively participate in it (Salmivalli, 2010). The behavior of bystanders significantly influences both victims and perpetrators. For example, classrooms with more reinforcers are more likely to experience bullying, whereas classrooms with more defenders tend to have lower rates of bullying incidents (Kärnä et al., 2010; Salmivalli et al., 2011).

Various individual difference traits influence bystander behavior. A study investigating the association between the Big Five personality traits and bullying participant roles found that defenders exhibited the highest levels of agreeableness and lower levels of neuroticism compared to victims and perpetrators. In contrast, outsiders displayed lower levels of extraversion and agreeableness than victims and defenders (Tani et al., 2003). In addition to personality traits, factors such as empathy and moral norms regarding bullying have also been examined. Furthermore, studies have explored individual difference variables specifically related to bullying, such as defender self-efficacy, which is confidence in one’s ability to protect victims from bullying (Thornberg et al., 2017). Defender self-efficacy is positively associated with defender behavior (Thornberg et al., 2017; van der Ploeg et al., 2017) and negatively associated with reinforcement of bullying (Pöyhönen et al., 2012; Thornberg et al., 2017).

Bystanders sometimes blame victims and display negative attitudes toward them. For instance, research has shown that in cyberbullying contexts, bystanders tend to attribute more blame to victims who engage in negative self-disclosure (Zeng et al., 2023). Moreover, research on bullying found that victim blaming is often explained through the framework of moral disengagement, which refers to justifying immoral and harmful actions despite recognizing their contradiction with moral values (Bandura, 2024). According to a literature review by Bussey et al. (2024), moral disengagement comprises eight mechanisms, one of which is victim blaming. This mechanism involves cognitive restructuring perceptions of the victim, such as by believing that “they deserved being harmed because they behaved badly.” Such reframing enables individuals to morally justify harmful behavior. Individual difference in moral disengagement can be assessed by validated scales. Higher levels of moral disengagement have been positively correlated with bullying reinforcement and outsider behavior but were not significantly associated with defender behavior (Thornberg et al., 2017; Thornberg et al., 2020). These findings highlight the importance of examining bullying from perspectives beyond those of victims and perpetrators, using various individual difference variables to understand bystander behavior.

Although moral disengagement is a widely used framework for explaining bystander behaviors such as victim blaming, alternative perspectives have also been proposed. One such perspective is “belief in a just world” (BJW; Lerner, 1980), which is conceptually distinct from moral disengagement. Individuals sometimes infer that a person’s misfortune results from their past behavior (or that a morally good person receives unexpected rewards), even in the absence of a causal relationship. Specifically, BJW refers to the tendency to believe that the world is a stable place where people receive outcomes that correspond to their actions (e.g., Hafer and Bègue, 2005) and is conceptualized as a “contract” between individuals and society (Lerner, 1977). Higher BJW is associated with stability and security, leading to long-term goal-setting and increased subjective well-being (Dalbert et al., 2001; Hafer and Bègue, 2005; Tian et al., 2022). BJW predicts positive psychological outcomes even in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic period (Kiral Ucar et al., 2022; Strelan et al., 2025). BJW also promotes the preference for delayed rewards over immediate or smaller ones. However, BJW also has a negative aspect, as it is associated with victim blaming. Individuals with strong BJW are more likely to perceive victimization as deserved (Correia et al., 2001), downplay the severity of victimization (Correia and Vala, 2003), psychologically distance themselves from victims (Correia et al., 2012; Murayama and Miura, 2015), and engage in secondary victimization (Mendonça et al., 2016). This tendency arises because witnessing innocent individuals suffer contradicts the belief in a just world. To maintain this belief, individuals may rationalize victimization by assuming that victims must have done something to deserve their misfortune (Callan et al., 2014), leading to perpetrator justification.

BJW can be understood as a unidimensional (Lipkus et al., 1996) or a multidimensional construct (Maes, 1998; Murayama et al., 2022) in a general worldview. Maes (1998) proposed two dimensions of BJW: immanent BJW (BJW-I), which attributes outcomes to past actions (i.e., karmic beliefs), and ultimate BJW (BJW-U), which assumes that present injustices will be compensated in the future. Concerning victim blaming, BJW-I is associated with causal attributions, whereas BJW-U is linked to psychological distancing that does not require cognitive reinterpretation (Hafer and Bègue, 2005; Murayama and Miura, 2015).

Considering the nature of BJW, bystanders with strong BJW may develop negative attitudes toward victims, perceiving bullying as a form of deserved misfortune. However, does BJW predict bullying behavior and bystander attitudes? Several studies have explored the associations between BJW and bullying involvement. Research on children has shown that BJW is associated with lower levels of bullying perpetration (Correia et al., 2009; Dalbert et al., 2001), more positive attitudes toward victims, and increased defender behavior (Chen et al., 2023; Fox et al., 2010). Theoretically, BJW would be expected to lead to negative attitudes toward victims. However, Fox et al. (2010) suggested that bullying is inherently unjust, and thus, individuals with high BJW may oppose it.

Conversely, studies using vignette-based methodologies with university students and adults have yielded conflicting results, showing that stronger BJW is associated with minimizing workplace bullying (Hellemans et al., 2017) and downplaying school bullying while increasing victim blaming (Saito, 2024; Voss and Newman, 2021). These discrepancies may be due to age differences among study participants or the conceptualization of BJW as a single dimension. This study explores the relationships between multidimensional BJW and bystander behaviors in school bullying among middle school students, which previous studies did not.

Previous research has not investigated the relations between BJW and bystander behavior by using multidimensional BJW yet. Against this background, this study aids in understanding the effect of BJW on school bullying to explore the relationship between BJW and bystander behavior among middle school students using a multidimensional BJW framework. Considering that not all students witness bullying firsthand (e.g., Joo et al., 2020), this study employs vignettes to assess bystander responses. Based on previous research utilizing multidimensional BJW (Hafer and Bègue, 2005; Murayama and Miura, 2015), a strong BJW-I is likely to lead to more victim blaming, which may contribute to increased secondary victimization and reduced defensive behaviors. In contrast, a strong BJW-U may help individuals maintain psychological distance from bullying incidents, thereby reducing their likelihood of perceiving such events as personally relevant. We hypothesize that BJW-I will be associated with proactive pro-bullying behaviors (second victimization and less defender behavior), whereas BJW-U will be related to a passive victim blaming attitude [keeping a distance from bully (psychological distancing)]. Additionally, this study evaluates the validity of a multidimensional BJW scale using measures of subjective well-being and future orientation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Procedure

The survey was conducted through an online Japanese research company, Asmark Inc. Initially, invitations for the web-based survey were sent to adults with children in middle school from the online survey pools throughout Japan, and the questionnaire was presented after both the parents and students agreed to a written informed consent. The questionnaire required the students to respond independently. After completing the survey, participants were compensated with points that could be exchanged for cash according to the research company’s guidelines.

2.2 Participants

The participants included 400 Japanese middle school students (Mage = 13.2, SD = 0.91) comprising 200 males, 197 females, and 3 non-respondents. The sample size was determined based on the sample size used in Murayama and Miura (2015), which employed the multidimensional BJW scale for Japanese participants.

2.3 Measurements

To measure just-world beliefs, this study employed the children’s multidimensional BJW scale (Tsurumaki et al., 2023), which consists of 12 items on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 6 = totally agree). This scale is a child-adapted version of the Japanese multidimensional BJW scale (Murayama and Miura, 2015) translated from the original English scale (Maes and Schmitt, 1999). It includes three subscales: immanent BJW (BJW-I; e.g., “Anyone will receive the punishment they deserve for the bad things they have done”), ultimate BJW (BJW-U; e.g., “Even those who bear sad fates will eventually find happiness”), and unjust world beliefs (BUW; e.g., “There is no fairness to be found anywhere in this world”). BUW reflects a view of the world as unfair and self-serving, often indicating the pursuit of personal gain or desires (e.g., Dalbert et al., 2001). Unlike the other subscales, the function of BUW has not been fully elucidated.

To examine the validity of the multidimensional BJW scale, we used subjective well-being and future orientation as correlates. According to Murayama and Miura (2015), BJW-U and BJW-I are positively correlated with these constructs, whereas BUW is negatively correlated with subjective well-being. For subjective well-being, we employed the S-WHO-5-J scale (Inagaki et al., 2013), which consists of 5 items on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never; 4 = always). This scale is a modified version of the 6-point Japanese version of the World Health Organization’s Five Well-Being Index (e.g., “I felt cheerful and in a good mood”). For future orientation, we used the Goal Orientation scale (Shirai, 1994; e.g., “I have a general plan for my future”), which consists of 5 items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree; 5 = agree).

2.4 Vignette

After completing the scales measuring individual difference variables, participants read a vignette describing bullying. The vignettes included three types of bullying: teasing, direct bullying, and cyberbullying. Each story was presented independently, and participants were asked to respond to questions about each scenario (see Supplementary Table S1). The types of bullying depicted were selected based on those most prevalent among Japanese middle school students. The stories were developed based on an anonymous post from an online community (Niftykids, 2016) and research by Saito (2024).1

2.5 Bystander behavior and attitudes

After reading each vignette, participants responded to 10 items about bystander behavior and attitudes using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree; 5 = agree). These items were adapted from previous bullying vignette studies (Wakamoto and Nishino, 2020) and research on the relationship between multidimensional just-world beliefs and victim blaming (Murayama and Miura, 2015). To measure victim-blaming attitudes, participants answered two items on psychological distance (e.g., “This kind of trouble could happen to people around me”) and two items on second victimization (e.g., “I think the victim also had some fault in this situation”). For bystander behaviors, participants answered two direct defending items on defending intention (e.g., “If I were there, I would stop the person bullying”) and two indirect defending items on help-seeking intention (e.g., “If I were there, I would report this to a teacher”). Additionally, participants were asked two items to assess whether they thought the situation depicted in the vignette constituted bullying. In Japan, bullying is defined as “acts exerting a psychological or physical influence on a child by another child, who attends the same school or has a certain personal relationship with the victim, and that causes the victim mental or physical harm (including acts carried out over the internet)” (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, 2013). According to this definition, any incident where a victim reports pain is considered bullying. Therefore, we asked if the incident in the vignette was considered bullying [recognition of bullying (at once); “Do you think this trouble constitutes bullying?”] and if repeated incidents would be considered bullying [recognition of bullying (if repeated); “If this trouble happened multiple times, would it be considered bullying?”].

2.6 Statistical analysis

First, this study tested the construct validity of the Multidimensional BJW Scale. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted, along with correlation analyses between the BJW subscales and individual difference variables to assess construct validity. Next, the study addressed its primary objective, which was examining the relationship between multidimensional BJW and bystander behavior and attitudes in bullying situations. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to predict bystander behavior and attitudes from the BJW subscales.

3 Results

A CFA assuming a three-factor structure for the 12-item multidimensional BJW scale was conducted [Χ2 (51) = 214, p < 0.001, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.92, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.09, Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 268]. The fit indices were slightly suboptimal. One item (X4) in the BJW-I subscale exhibited a low factor loading (β = 0.44) and was excluded from the analysis. A second CFA was conducted on the revised 11-item, three-factor model [Χ2 (41) = 160, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.09, AIC = 210]. Although RMSEA did not improve, CFI increased, and AIC suggested a better model fit. Thus, the 11-item, three-factor structure was deemed appropriate (see Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S1).

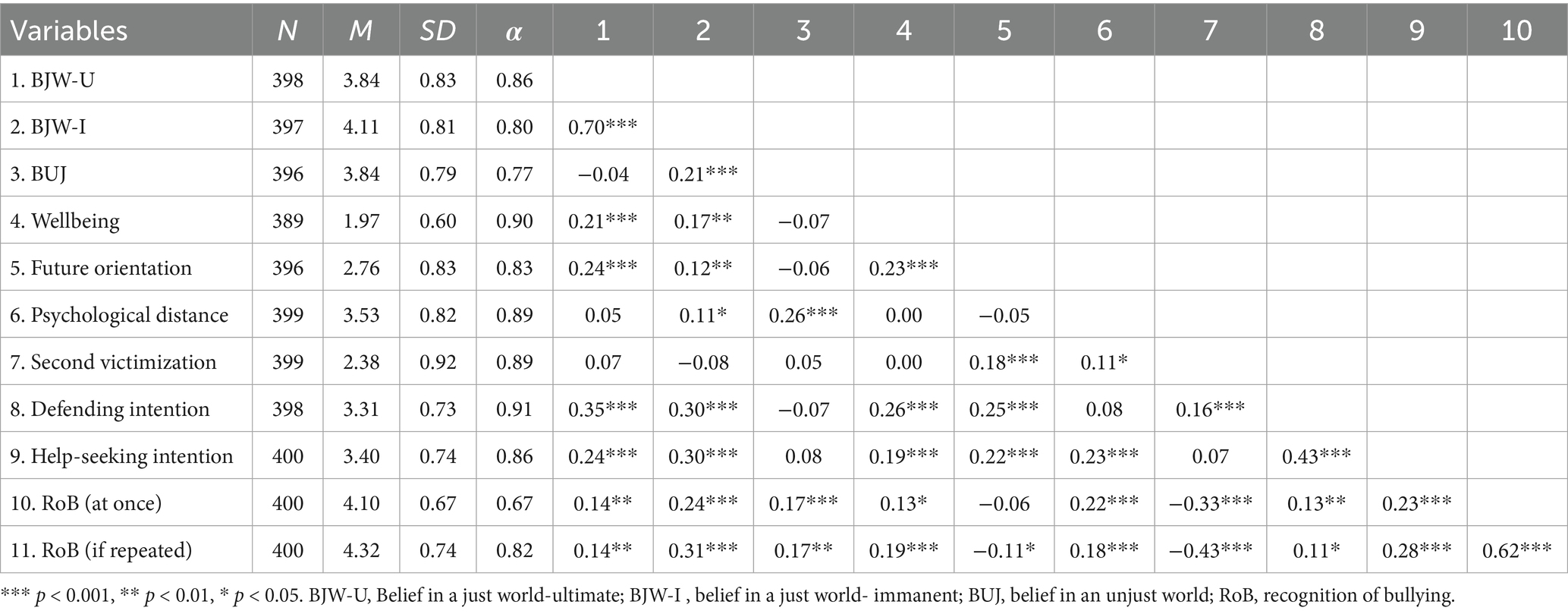

Table 1 presents the mean, standard deviation, reliability coefficients, and correlations for all measures. Scores for bystander behavior across the three vignettes were aggregated. As presented in Table 1, BJW-U and BJW-I were positively correlated with subjective well-being and future orientation, whereas BUW showed no significant correlation. The latter was excluded from further analyses because BJW-U and BJW-I replicated findings from Murayama and Miura (2015), but BUW did not.

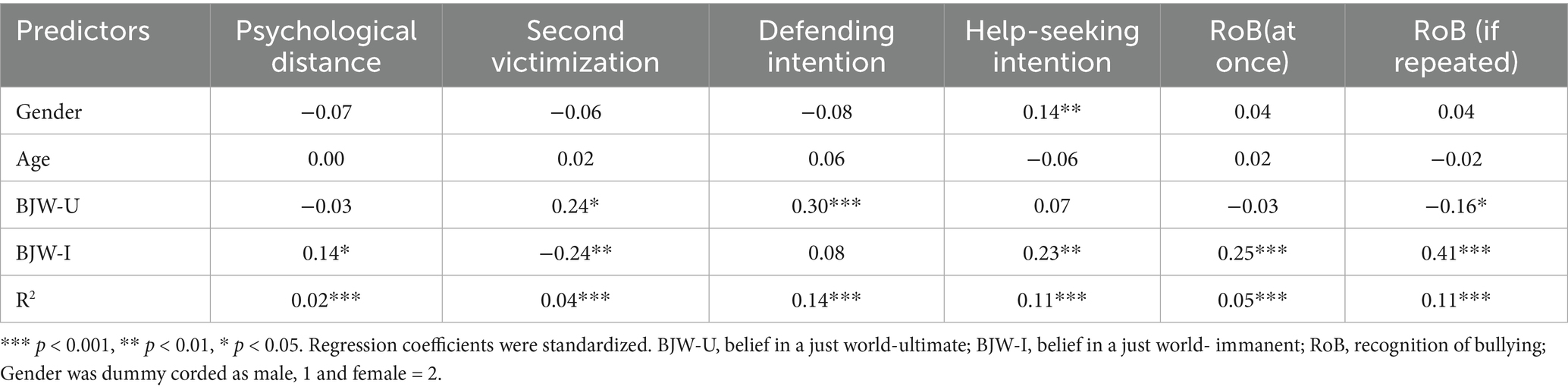

Next, a multiple regression analysis was conducted with gender and age as control variables, BJW-U and BJW-I as independent variables, and bystander behavior and attitudes as the dependent variable (Table 2). Variance inflation factors were below 2, indicating no multicollinearity concerns. The results indicated that higher BJW-I was associated with a greater willingness to seek help, less psychological distancing and second victimization, and higher recognition of bullying incidents. Conversely, higher BJW-U was associated with a greater tendency to intervene in bullying but also with increased second victimizing and lower recognition of repeated bullying incidents.

Table 2. The result of multiple regression predicting bystander’s attitude and behaviors from belief in a just world.

4 Discussion

This study examined the relationship between BJW and the behavior of bystanders in bullying situations among middle school students, using a multidimensional framework of BJW. The analysis revealed that while BJW-I was associated with positive attitudes and behaviors toward victims of bullying, BJW-U did not exhibit the same relationship. These results did not support the hypothesis of this study. Specifically, higher levels of BJW-U were linked to a greater intention to intervene in bullying; however, they were also associated with a tendency to blame victims and a reduced likelihood of perceiving repeated incidents as bullying. BJW-I, believing karmic reasoning was related to victim advocacy. In contrast, BJW-U, believing misfortune will be compensated in the future was associated with secondary victimization and the tendency to downplay bullying.

The relationship between BJW and the outcomes varied across its dimensions. The findings regarding BJW-I were consistent with these of Fox et al. (2010) and Chen et al. (2023), which indicates BJW does not tolerate the injustice of bullying. The results concerning BJW-U, except for prediction of defensive behavior, supported previous findings by Hellemans et al. (2017) and Voss and Newman (2021), which indicate that BJW predicts victim blaming and minimization of harm. This also aligns with the belief that people get what they deserve, and is consistent with the theoretical framework of BJW. However, the fact that BJW-U, rather than BJW-I, was associated with victim blaming contrasted with the expected pattern of multidimensional BJW (Hafer and Bègue, 2005; Murayama and Miura, 2015). This study is the first to demonstrate that different dimensions of BJW are associated with distinct patterns of attitudes toward bullying victims, offering intriguing insights into previous research on BJW and bullying. Research examining the relationship between BJW and bullying remains limited, and the findings across studies are inconsistent. To gain a deeper understanding of how BJW relates to bullying, future research should adopt a multidimensional approach to BJW and consider various forms of bystander behavior.

The results of this study, which employed a multidimensional BJW scale, suggest that the relationship between BJW and bystanders’ attitudes toward bullying is complex. Inconsistencies among previous studies may be better understood by considering the multidimensional nature of BJW. Given that different types of BJW influence strategies for victim blaming differently (Murayama and Miura, 2015), it is reasonable that BJW-U predicted judgments of repeated bullying incidents. Unlike cognitive reinterpretation, the recognition of bullying in this study involved distancing the event itself, which can be understood as a form of psychological distancing, rather than reinterpreting it. Furthermore, the findings reveal that BJW-U was associated with intentions to intervene in bullying. Concurrently, BJW-I was linked to prosocial behavior toward victims, which supports the interpretation proposed by Fox et al. (2010). Middle school students with high BJW-I were less likely to tolerate injustice, recognize interpersonal conflicts as bullying, refrain from blaming victims, and were more likely to seek help. The finding that BJW predicted secondary victimization was partially consistent with previous findings (Saito, 2024; Voss and Newman, 2021). However, this was inconsistent with the theoretical concept of BJW that BJW-I predicts secondary victimization, rather than BJW-U (Maes, 1998). As presented in Table 1, secondary victimization had a weak positive correlation with psychological distancing and a moderate negative correlation with bullying recognition. This suggests that rather than actively engaging in secondary victimization, students with high BJW-U may have distanced themselves from the event, perceiving bullying as an issue unrelated to themselves. In sum, the current study which is the first study exploring the relationships between multidimensional BJW and bystander behaviors demonstrated that BJW predicted pro-bullying and anti-bullying attitudes concurrently. These results emphasized the advantage of BJW as a multidimensional construct when researchers predict bystander attitudes from BJW.

The findings of this study offer several important educational implications. While BJW-I—which attributes outcomes to one’s past behavior—was associated with more positive attitudes when witnessing bullying, BJW-U, which reflects a future-oriented belief that injustice will eventually be compensated, was not associated with similarly positive attitudes. Therefore, educational efforts aimed at fostering BJW-I may be effective for bullying prevention. Given that individuals with strong BJW-U are more likely to psychologically distance themselves from unjust events (Hafer and Bègue, 2005), they may be less inclined to witness bullying as personal and more likely to develop negative attitudes toward the victim. Nevertheless, bullying is a group process, and bystanders’ reactions play an important role (Salmivalli, 2010). Therefore, it is essential that teachers or schools communicate that bullying is not merely an individual issue but a classwide problem. They should encourage each student to reflect on how they, as bystanders, can contribute to creating a more supportive and just classroom environment.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, as this study was a cross-sectional study utilizing individual difference measures, causal relationships could not be thoroughly examined. Future study needs to explore the relations between BJW and bystander behaviors in a longitudinal design. Second, this study was an experimental study using vignettes. Field studies will be needed to examine actual bystander behavior in bullying to provide a deeper understanding of the role of BJW. Third, a notable strength of this study was the use of an online panel to recruit participants from across Japan, enabling a broad geographical coverage. However, the extent of bullying prevention education may vary considerably between schools and regions, which could lead to inconsistencies in the results. Furthermore, it unclears whether students completed questionnaire without parental assistance. Future research should consider regional and school-level characteristics when interpreting findings from a school-based survey. Additionally, cultural factors should not be overlooked. For example, Murakami et al. (2023) study found that Japanese individuals tend to exhibit stronger immanent justice reasoning toward COVID-19 patients compared to people in other countries. Exploring the influence of such cultural tendencies may provide deeper insights into how BJW functions in different sociocultural contexts.

This study contributes to understanding bullying from a bystander’s perspective by demonstrating that different dimensions of BJW influence bystander behavior and attitudes toward bullying. This study revealed that BJW has both pro-bullying and anti-bullying attitudes. By providing evidence-based findings, this study enhances our understanding of bullying and offers potential implications for bullying prevention. Teachers and schools need to prevent bullying by paying attention to the complex relationship between BJW and bullying attitudes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by Hokkaido University of Education Ethics review committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent was obtained via an online form from all participants and their parents.

Author contributions

KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was financial supported by The Uehiro Foundation on Ethics and Education and Kyo-shin Ltd., (Chiba-city). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1586967/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^In this survey, participants were allowed not to answer questions if they wished. This resulted in missing data. In our study, all participants were considered to have read all the vignettes as they completed the entire survey.

References

Bandura, A. (2024). Manual for constructing moral disengagement scales. Available online at: https://albertbandura.com/pdfs/MANUAL%20FOR%20CONSTRUCTING%20MORAL%20DISENGAGEMENT%20SCALES.pdf (Accessed February 21, 2025).

Bussey, K., Luo, A., and Jackson, E. (2024). The role of moral disengagement in youth bullying behaviour. Int. J. Psychol. 59, 1254–1262. doi: 10.1002/ijop.13254

Callan, M. J., Harvey, A. J., and Sutton, R. M. (2014). Rejecting victims of misfortune reduces delay discounting. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol., 51, 41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.11.002

Chen, Y., Wang, S., Liu, S., Hong, X., Zheng, J., Jiao, L., et al. (2023). Belief in a just world and bullying defending behavior among adolescents: roles of self-efficacy and responsibility. Curr. Psychol. 42, 21532–21540. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03198-5

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., and Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic investigation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 25, 65–83. doi: 10.1037/a0020149

Correia, I., Kamble, S. V., and Dalbert, C. (2009). Belief in a just world and well-being of bullies, victims, and defenders: a study with Portuguese and Indian students. Anxiety Stress Coping 22, 497–508. doi: 10.1080/10615800902729242

Correia, I., and Vala, J. (2003). When will a victim be secondarily victimized? The effect of observer’s belief in a just world, victim’s innocence, and persistence of suffering. Soc. Justice Res 16, 379–400. doi: 10.1023/A:1026313716185

Correia, I., Alves, H., Sutton, R., Ramos, M., Gouveia-Pereira, M., and Vala, J. (2012). When do people derogate or psychologically distance themselves from victims? Belief in a just world and ingroup identification. Pers. Individ. Differ. 53, 747–752. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.05.032

Correia, I., Vala, J., and Aguiar, P. (2001). The effects of belief in a just world and victim’s innocence on secondary victimization, judgements of justice, and deservingness. Soc. Justice. Res. 14, 327–342. doi: 10.1023/A:1014324125095

Dalbert, C., Lipkus, I. M., Sallay, H., and Goch, I. (2001). A just and an unjust world: structure and validity of different world beliefs. Pers. Individ. Differ. 30, 561–577. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00055-6

Fox, C. L., Elder, T., Gater, J., and Johnson, E. (2010). The association between adolescents’ beliefs in a just world and their attitudes to victims of bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 183–198. doi: 10.1348/000709909x479105

Hafer, C. L., and Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychol. Bull. 131, 128–167. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.128

Hellemans, C., Dal Cason, D., and Casini, A. (2017). Bystander helping behavior in response to workplace bullying. Swiss J. Psychol. 76, 135–144. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185/a000200

Inagaki, H., Ito, K., Sakuma, N., Sugiyama, M., Okamura, T., and Awata, S. (2013). Reliability and validity of the simplified Japanese version of the WHO-five well-being index (S-WHO-5-J). Jpn. J. Public Health 60, 294–301. doi: 10.11236/jph.60.5_294

Joo, H., Kim, I., Kim, S. R., Carney, J. V., and Chatters, S. J. (2020). Why witnesses of bullying tell: individual and interpersonal factors. Child. Youth. Serv. Rev. 116:105198. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105198

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E., and Salmivalli, C. (2010). Vulnerable children in varying classroom contexts: bystanders’ behaviors moderate the effects of risk factors on victimization. Merrill Palmer. Q., 261–282. doi: 10.1353/mpq.0.0052

Kiral Ucar, G., Donat, M., Bartholomaeus, J., Thomas, K., and Nartova-Bochaver, S. (2022). Belief in a just world, perceived control, perceived risk, and hopelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a globally diverse sample. Curr. Psychol. 41, 8400–8409. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03172-1

Lerner, M. J. (1977). The justice motive: some hypotheses as to its origins and forms. J. Pers. 45, 1–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1977.tb00591.x

Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., and Siegler, I. C. (1996). The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: implications for psychological well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 22, 666–677. doi: 10.1177/0146167296227002

Maes, J. (1998). “Immanent justice and ultimate justice: two ways of believing in justice” in Responses to victimizations and belief in a just world. eds. L. Montada and M. J. Lerner (New York: Plenum Press), 9–40.

Maes, J., and Schmitt, M. (1999). More on ultimate and immanent justice: Results form the research project Justice as a Problem within Reunified Germany. Soc. Just. Res., 12, 65–78. doi: 10.1023/A:1022039624976

Mendonça, R. D., Gouveia-Pereira, M., and Miranda, M. (2016). Belief in a just world and secondary victimization: the role of adolescent deviant behavior. Pers. Individ. Differ. 97, 82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.021

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (2013). Act for the promotion of measures to prevent bullying. Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/seitoshidou/1337278.htm (Accessed February 21, 2025).

Mitsopoulou, E., and Giovazolias, T. (2015). Personality traits, empathy, and bullying behavior: a meta-analytic approach. Aggress. Violent. Behav. 21, 61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.007

Murakami, M., Hiraishi, K., Yamagata, M., Nakanishi, D., Ortolani, A., Mifune, N., et al. (2023). Differences in and associations between belief in just deserts and human rights restrictions over a 3-year period in five countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. PeerJ 11:e16147. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16147

Murayama, A., and Miura, A. (2015). Derogating victims and dehumanizing perpetrators: functions of two types of beliefs in a just world. Jpn. J. Psychol. 86, 1–9. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.86.13069

Murayama, A., Miura, A., and Furutani, K. (2022). Cross-cultural comparison of engagement in ultimate and immanent justice reasoning. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 25, 476–488. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12510

Niftykids, (2016). Test results on LINE... Help... Avaiable online at: https://kids.nifty.com/cs/kuchikomi/kids_soudan/list/aid:160403729127/1.html (Accessed October 7, 2025).

OECD (2023). PISA 2022 results (volume II): learning during—and from—disruption. Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., and Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 41, 47–65. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., and Salmivalli, C. (2012). Standing up for the victim, siding with the bully, or standing by? Bystander responses in bullying situations. Soc. Dev. 21, 722–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00662.x

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., and Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child. Abuse. Negl. 34, 244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009

Saito, R. (2024). Examination of the impact of illustrative elements on bullying recognition: The effects of belief in a just world and depictions of bullying scenes [unpublished bachelor’s thesis]. Asahikawa: Hokkaido University of Education.

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 15, 112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Salmivalli, C., Laninga-Wijnen, L., Malamut, S. T., and Garandeau, C. F. (2021). Bullying prevention in adolescence: solutions and new challenges from the past decade. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 1023–1046. doi: 10.1111/jora.12688

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., and Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 40, 668–676. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.597090

Shirai, T. (1994). A study on the construction of experiential time perspective scale. Jpn. J. Psychol. 65, 54–60. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.65.54

Strelan, P., Manning, M., Lucas, T., Agostini, M., Belanger, J. J., Gützkow, B., et al. (2025). Just world beliefs in a time of crisis: Cross-lagged panel and moderating cross-national effects on mental health and well-being outcomes. Soc. Justice Res., 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11211-025-00451-7

Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., and Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 777–784. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401

Tani, F., Greenman, P. S., Schneider, B. H., and Fregoso, M. (2003). Bullying and the big five. Sch. Psychol. Int. 24, 131–146. doi: 10.1177/0143034303024002001

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Elmelid, R., Johansson, A., and Mellander, E. (2020). Standing up for the victim or supporting the bully? Bystander responses and their associations with moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy, and collective efficacy. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 563–581. doi: 10.1007/s11218-020-09549-z

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Hong, J. S., and Espelage, D. L. (2017). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in Sweden: a multilevel study. J. Sch. Psychol. 63, 49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002

Tian, S., Chen, S., and Cui, Y. (2022). Belief in a just world and mental toughness in adolescent athletes: the mediating mechanism of meaning in life. Front. Psychol. 13:901497. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.901497

Tsurumaki, A., Tanaka, T., Asami, Y., and Murayama, A. (2023). Development of multidimensional belief in a just world scale for children. The 87th annual convention of the Japanese psychological association Japan

UNESCO (2024). School bullying, an inclusive definition. Available online at: https://antibullyingcentre.ie/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/UNESCO_Fin_Def_August_24.pdf

van der Ploeg, R., Kretschmer, T., Salmivalli, C., and Veenstra, R. (2017). Defending victims: what does it take to intervene in bullying and how is it rewarded by peers? J. Sch. Psychol. 65, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.002

Voss, D., and Newman, L. S. (2021). Confronted with bullying when you believe in a just world. Front. Educ. 6:634517. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.634517

Wakamoto, J., and Nishino, Y. (2020). The recognition of bullying among elementary and secondary school students in hypothetical situations: indeed, are children seeing the situation as a bullying? The Japanese journal of the study of guidance and counseling. 19, 44–54.

Keywords: bullying, adolescence, belief in a just world, bystanders, aggression

Citation: Mizuno K (2025) Bystander behavior in school bullying and multidimensional belief in a just world. Front. Educ. 10:1586967. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1586967

Edited by:

Hero Gefthi Firnando, Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi GICI Business School, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Raquel António, University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE), PortugalXu Wang, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Mizuno. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kumpei Mizuno, bWl6dW5vLmt1bXBlaUBhLmhva2t5b2RhaS5hYy5qcA==

Kumpei Mizuno

Kumpei Mizuno