- 1Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Department of Curriculum and Instruction, The Education University of Hong Kong, Tai Po, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3Department of Curriculum and Instruction, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China

The evolving landscape of educational reform, coupled with the unique nature of the teaching profession, has positioned job crafting as a promising strategy to enhance teachers’ ability to deliver knowledge, foster student development, and support their own professional growth. This study aims to investigate the job crafting behaviors and their influencing factors among primary and secondary school teachers. A total of 1,886 teachers from Yunnan and Gansu provinces in western China were randomly surveyed using a structured self-report questionnaire. The instrument included demographic items and a five-dimensional job crafting Likert-scale. Descriptive statistics, independent sample t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and correlation and regression analyses were conducted using SPSS. To ensure the construct validity of the job crafting scale, confirmatory factor analysis was performed using Mplus. The results yielded four main findings: (1) Gender did not significantly impact overall job crafting behaviors; however, male teachers reported higher scores in increasing social and challenging job resources compared to their female counterparts. (2) Both age and years of teaching experience significantly influenced teachers’ overall job crafting behaviors, with older teachers and those with more experience exhibiting higher job crafting scores. (3) Regarding teaching positions, school administrators reported higher levels of job crafting in increasing social job resources, increasing challenging job demands, and optimizing job demands. (4) Teachers from different types of schools showed significant differences in increasing structural job resources, with teachers from district-level schools scoring lower in this dimension.

1 Problem statement

China’s education system is undergoing significant transformation. National policies—including the Outline of the National Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development Plan (2010–2020), the Opinion on Strengthening the Teaching Workforce [State (2012) No. 41], the Opinion on Intensifying Training for Primary and Secondary School Teachers [Teacher (2011) No. 1], and the 14th Five-Year Plan—identify the development of a high-quality, professional teaching force as a strategic priority (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2010, 2011; State Council of the People's Republic of China, 2012, 2021). Under the New Curriculum Reform, teachers’ roles have shifted from knowledge transmitters to curriculum designers and learning facilitators, increasing job complexity and cognitive and emotional demands. In this context, job crafting (JC)—self-initiated adjustments to job resources and demands—has been advanced as a promising, bottom-up means for teachers to respond to classroom uncertainties, sustain professional growth, and enhance well-being and engagement (Loughran and Hamilton, 2016; Huang et al., 2022, 2025a; Huang et al., 2019; Ma, 2022; Qi and Wu, 2016; Qi et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2023).

Over the past decade, empirical work on teachers’ JC in China has grown steadily, with most studies focusing on primary and secondary school teachers (Ma, 2022). Findings converge on a moderate level of overall JC among Chinese primary and secondary school teachers (Li and Tang, 2022; Zhao et al., 2021), with discernible subgroup differences and dimension-specific patterns. For instance, urban teachers tend to report higher JC than rural teachers, and female report greater JC engagement than male (Zhao and Li, 2019). Studies also indicate comparatively higher scores on structural and task crafting than on other dimensions (Zhao et al., 2021; Li and Tang, 2022).

Nowwithstanding these contributions, two key problems remain salient. First, the field lacks large-sample, multi-region studies that provide a systematic portrait of overall JC and the concrete manifestations of each JC dimension among Chinese primary and secondary teachers. Second, personal determinants of teachers’ job crafting, particularly internal demographic characteristics, are insufficiently explored in prior studies (Wang et al., 2023), and some of them yield inconsistent findings (Lyu and Fan, 2020; Zhao and Li, 2019). Addressing these problems requires robust descriptive evidence that documents the current JC levels across teacher subgroups, delineates dimension-specific profiles, and clarifies how JC varies across demographic subgroups.

To respond, the present study conducts a large-sample descriptive analysis of JC among primary and secondary teachers in central and western China. We examine how demographic factors and school characteristics are associated with JC, thereby establishing a baseline profile of JC in the Chinese context. The findings of this research are expected to contribute to theoretical advancements in the field of teacher behavior and offer practical recommendations for teacher training, educational programs, and school policies aimed at enhancing teacher performance and professional development.

2 Literature review

2.1 Teachers’ job crafting

Job crafting (JC), adopting resource-based perspective, is defined as a proactive, bottom-up process in which employees intentionally modify and customize job resources and/or job demands to fit in with their needs, capabilities, and preferences, and to attain their personal work goals (Tims and Bakker, 2010; Tims et al., 2012). Teachers’ JC thus can be conceptualized as an adaptive process (Ghitulescu, 2006; Peral and Geldenhuys, 2016), wherein educators leverage available job resources to navigate the landscape of job demands and imbue their work with intrinsic significance (Li and Tang, 2022). In the teaching profession, job crafting manifests in various forms, such as collaborating with colleagues to adjust teaching methods, implementing educational reforms to foster a sense of professional identity, and bridging boundaries between different subjects and classroom environments (Huang et al., 2022; Pang et al., 2018). Teachers’ endeavor in JC has been proven positively associated with the enhanced well-being, such as job satisfaction, positive affect, and engagement (Dreer, 2022; Huang et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2022), as well as work performance, such as teaching for creativity (Huang et al., 2022) and innovative teaching (Zheng et al., 2023). Moreover, teachers who actively engage in job crafting are better equipped to adapt to the evolving demands of society, thus playing a critical role in school improvement and educational reform (Day and Sachs, 2004; Ghitulescu, 2006; Loughran and Hamilton, 2016).

The Job Crafting Scale, developed by Tims and Bakker (2010) based on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, is widely utilized in research. It identifies four dimensions of job crafting: increasing structural job resources (e.g., acquiring new professional skills), increasing social job resources (e.g., seeking feedback and support from colleagues), increasing challenging job demands (e.g., taking on additional tasks), and decreasing hindering job demands (e.g., emotional avoidance to reduce stress). Building on Elliot’s (2006) distinction between approach and avoidance motivations, job crafting behaviors can be categorized into two types: approach-oriented and avoidance-oriented. The first three dimensions—structural and social job resources, as well as challenging job demands—are considered approach-oriented job crafting. In contrast, decreasing hindering job demands is classified as avoidance-oriented. Recently, Demerouti and Peeters (2018) introduced a new form of avoidance-oriented job crafting: optimizing job demands. Unlike merely decreasing hindering job demands, optimizing job demands involves defensive strategies to prevent resource loss and maintain person-job fit. Common behaviors in this category include simplifying work processes to enhance efficiency (Hu et al., 2020). However, this aspect of job crafting remains underexplored in teacher education research (Huang et al., 2022). This gap in the literature highlights the need to incorporate the optimizing job demands dimension into the current study’s instrument.

Existing evidence suggests that job crafting among Chinese primary and secondary teachers generally sits at a moderate level (Li and Tang, 2022; Sun and Du, 2023; Zhao et al., 2021), with discernible subgroup differences and dimension-specific patterns (Zhao and Li, 2019). For example, Zhao and Li (2019), in a survey of 359 teachers, found higher JC scores among urban than rural teachers and higher frequencies among female than male. Similarly, Zhao et al. (2021) reported that most teachers’ moderate-level of engagement in job crafting and relatively higher scores on structural crafting dimension. Research on compulsory-education teachers has likewise indicated that their overall JC remains at a moderate level, with considerable room for improvement, and comparatively higher scores on task crafting (Li and Tang, 2022). Despite these advances, there is a lack of large-sample, multi-region studies that provide a systematic portrait of overall JC and the concrete manifestations of each JC dimension among Chinese primary and secondary teachers. Addressing this gap requires comprehensive descriptive evidence that delineates the current status and dimensional profile of JC across teacher subgroups, thereby establishing a baseline for subsequent mechanism-oriented research and targeted professional support.

2.2 Factors influencing teachers’ job crafting

Research on the antecedents of job crafting has predominantly focused on two main perspectives: individual attributes and organizational characteristics. At the individual level, personality differences and demographic variables are key factors that have been frequently explored (Bindl and Parker, 2011; Tornau and Frese, 2013). As with other work behaviors, job crafting is closely tied to personal identity and individual traits, which shape how employees adapt their jobs to better suit their needs and preferences.

Rudolph et al. (2017) proposed a comprehensive conceptual model of job crafting, which examined common demographic factors—such as gender, age, and education—and job characteristics—such as tenure and work duration—individually. However, research specifically examining the antecedents of job crafting among teachers, particularly in China, remains limited and yields inconsistent findings. For example, studies on gender differences in job crafting have produced conflicting results. Some studies suggest that female teachers engage in job crafting more frequently than their male counterparts (Rudolph et al., 2017; Zhao and Li, 2019), while others report the opposite trend (Ali et al., 2020; Lyu and Fan, 2020). Similarly, research on the role of tenure in influencing job crafting is also mixed. Tornau and Frese (2013) found no significant relationship between tenure and job crafting, whereas the findings of Rudolph et al. (2017) meta-analysis identified a negative correlation. Given the unique nature of the teaching profession, it is essential to explore whether age and tenure serve as boundary conditions that affect the relationship between job crafting and various job outcomes.

In addition to individual factors, job characteristics also play a crucial role in shaping teachers’ job crafting behaviors. However, studies examining how job crafting differs across teaching positions remain scarce. In mainland China, schools are typically classified based on administrative level (e.g., provincial, municipal, district, or township) or educational stage (e.g., primary school, junior high school, and senior high school). Some studies have explored the influence of school type, particularly comparing urban and rural schools, and found that urban teachers tend to engage in job crafting more frequently than their rural counterparts (Zhao and Li, 2019). However, a more systematic analysis is needed to explore how various job characteristics, including teacher position and school type, influence job crafting behaviors among primary and secondary school teachers.

3 Research methodology

3.1 Procedures and participants

Participants in this study were recruited from primary and secondary schools in two provinces of mainland China—Yunnan and Gansu. A random sampling strategy was employed to select participating schools, which included both urban and rural areas. The survey was administered online through Wenjuanxing (a platform comparable to SurveyMonkey) and distributed via several WeChat groups. Teachers were invited to participate anonymously and voluntarily, with an informed consent form provided at the beginning of the survey. Data collection took place over a three-week period. This dataset forms part of a larger research project led by the corresponding author. Although shared with other studies (Huang et al., 2022), the variable associations analyzed in the present work have not been examined previously.

A total of 2,137 teachers completed the questionnaire. After data cleaning—excluding cases with completion time shorter than one-third of the median response time or with inconsistent responses to oppositely valenced item pairs (Dewitt et al., 2019)—1,886 valid responses remained. No missing data were detected. Of the final sample, 1,343 participants were female and 543 were male. Teachers were predominantly from urban schools (N = 1,444, 76.5%), with 442 from rural schools. The sample comprised 840 primary school teachers and 1,046 were secondary school teachers. Most participants were employed in public schools (N = 1,849, 98.0%). Regarding educational background, 61.2% held a bachelor’s degree, 13.1% held a postgraduate degree, and the remaining 26.7% possessed an associate degree or lower qualification. In terms of professional roles, 1,488 were regular teachers, 387 were teacher leaders, and 11were adminitrative staff. The average age of the teachers was 39.64 years (SD = 9.03), with an average teaching experience of 16.5 years (SD = 10.13).

3.2 Instrument

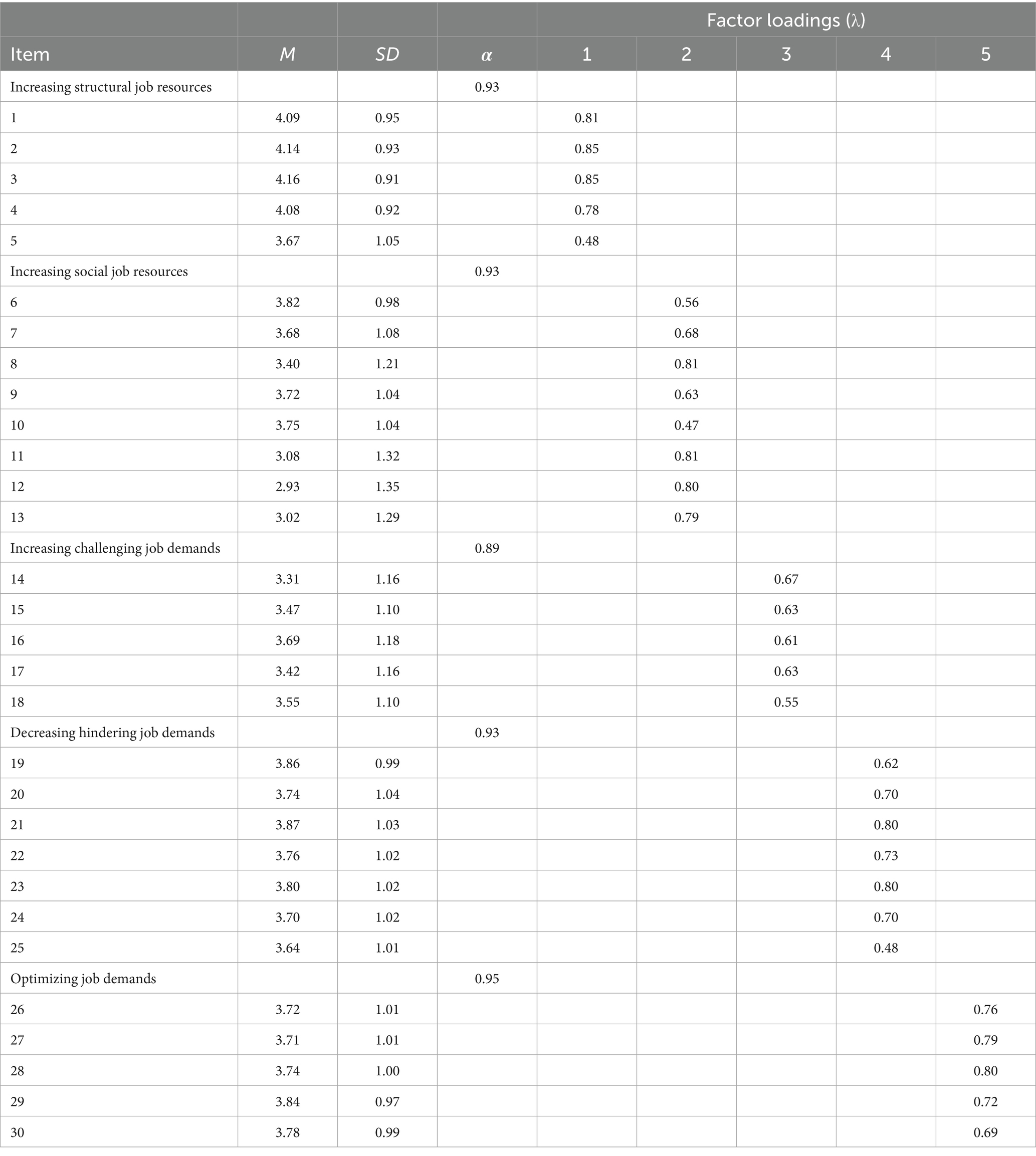

To measure teachers’ job crafting behaviors, this study adapted scales developed by Tims and Bakker (2010) and Demerouti and Peeters (2018) considering the school environment and the work characteristics of the teaching profession. The 30-item scale comprises five subscales: increasing structural job resources (5 items, α = 0.93, e.g., ‘I try to develop me capabilities at work’), increasing social job resources (8 items, α = 0.93, e.g., ‘I ask for feedback on my performance from my mentors/supervisors’), increasing challenging job demands (5 items, α = 0.89, e.g., ‘When there is not much to do at work, I see it as a chance to start new projects’), decreasing hindering job demands (7 items, α = 0.93, e.g., ‘I make sure that my work is mentally less intense’), and optimizing job demands (5 items, α = 0.95, e.g., ‘I look for ways to do my work more efficiently’). Participants rated items using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “never” and 5 representing “always.” Higher scores indicate more frequent proactive job crafting behaviors.

3.3 Analytical strategy

Data processing and analysis were conducted using SPSS (Version 26.0) and Mplus (Version 8.3). To examine the internal construct validity of the job crafting scale for the teacher population, the total dataset was randomly split in half. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on one half to identify the underlying factor structure, followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the other half to validate the factor structure. Consistent with established guidelines, only items with factor loadings of 0.40 or higher were retained (Nunnally, 1994).

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were calculated to summarize teachers’ scores across the different dimensions of job crafting. Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among variables, while stepwise regression analysis was applied to explore the effects of teachers’ age and professional position on job crafting behaviors. Additionally, independent-samples t-tests and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were employed to assess differences in job crafting scores across various demographic and school-related variables.

4 Research results

4.1 Preliminary analysis

The EFA results on teacher job crafting showed five factors. The overall Cronbach’s alpha (α) for the whole scale in this study was 0.97, demonstrating excellent reliability. No scale items were deleted because of the acceptable factor loadings (see Table A1). Furthermore, the CFA results revealed factor loadings ranging from 0.60 to 0.97 (all above 0.5), confirming that each item effectively measured its intended construct. The model fit indices were as follows: RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.919, TLI = 0.910, and SRMR = 0.065, all of which suggest good validity.

4.2 Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

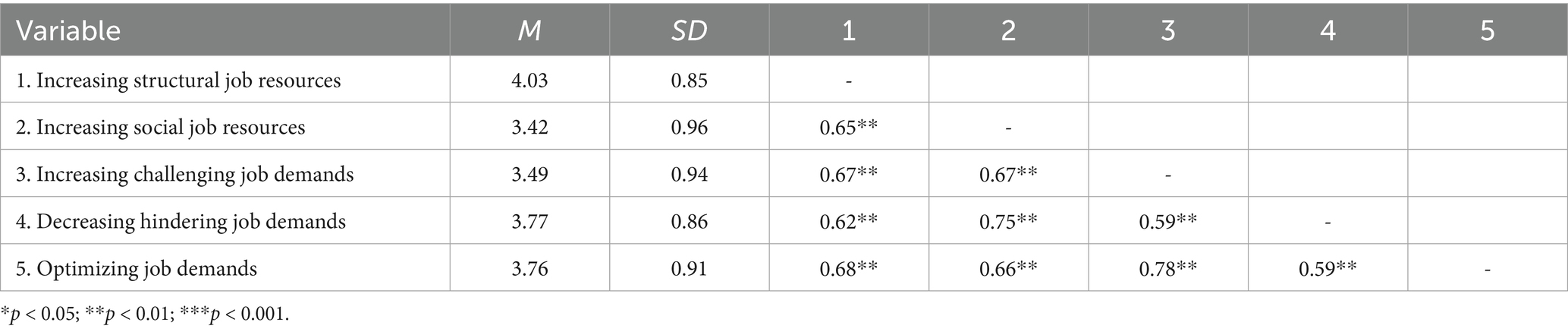

The descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results for teachers’ job crafting behaviors are summarized in Table 1. The overall mean score for job crafting among teachers was 3.69 (SD = 0.77). The scores for the individual dimensions of job crafting, in descending order, were as follows: increasing structural job resources (M = 4.03, SD = 0.85), decreasing hindering job demands (M = 3.77, SD = 0.86), optimizing job demands (M = 3.76, SD = 0.91), increasing challenging job demands (M = 3.49, SD = 0.94), and increasing social job resources (M = 3.42, SD = 0.96). These findings suggest that, overall, job crafting behaviors among primary and secondary school teachers are generally above average.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationships among the five dimensions of job crafting. The results (see Table 1) indicate significant positive correlations between all pairs of variables (p < 0.001), with all correlation coefficients exceeding 0. This suggests that as one dimension of job crafting increases, other dimensions tend to increase as well. Notably, the correlations between increasing challenging job demands and optimizing job demands (r = 0.78), and between increasing social resources and decreasing hindering job demands (r = 0.75), were particularly high, indicating a strong relationship between these dimensions.

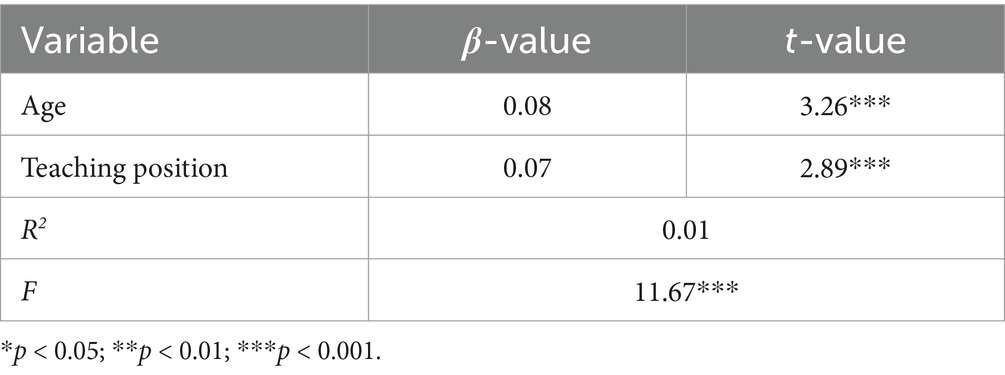

4.3 Regression analysis

To further examine the impact of demographic and school-related characteristics on teachers’ job crafting behaviors, a stepwise regression analysis was performed. Variables such as gender, years of teaching experience, educational background, position, and school type were added progressively to build a regression model. The results, as shown in Table 2, reveal that age and teaching position had a significant positive impact on overall job crafting behaviors, with regression coefficients of 0.08 and 0.07, respectively, both significant at the p < 0.05 level. Among these variables, age had the greater influence on teachers’ job crafting behaviors. Other variables, such as gender, educational background, and school type, did not exhibit significant effects (p > 0.05) and were excluded from the final model due to their minimal impacts.

4.4 Comparative analysis of demographic and school characteristics

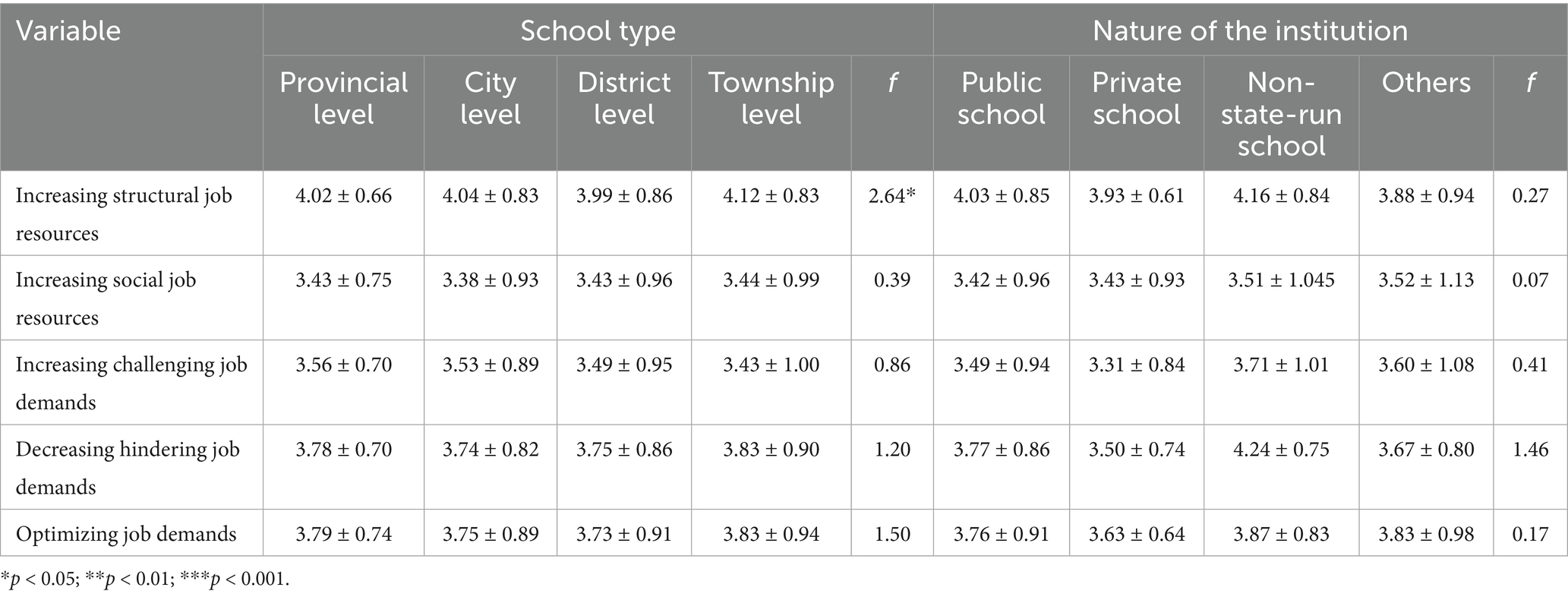

Building on the conceptual model from Rudolph et al. (2017) meta-analysis of job crafting, this study explores the differences in job crafting behaviors across various demographic factors (gender, age, education, teaching position, and teaching experience) and work-related variables (school type and teaching level). The findings are summarized in Tables 3–5.

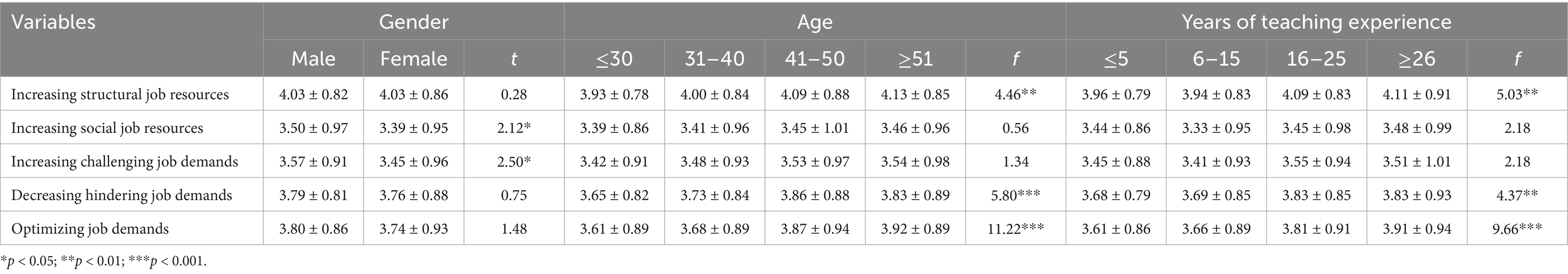

Table 3. Comparison of differences in the five dimensions of job crafting by demographic variables (Gender, age, and years of teaching experience).

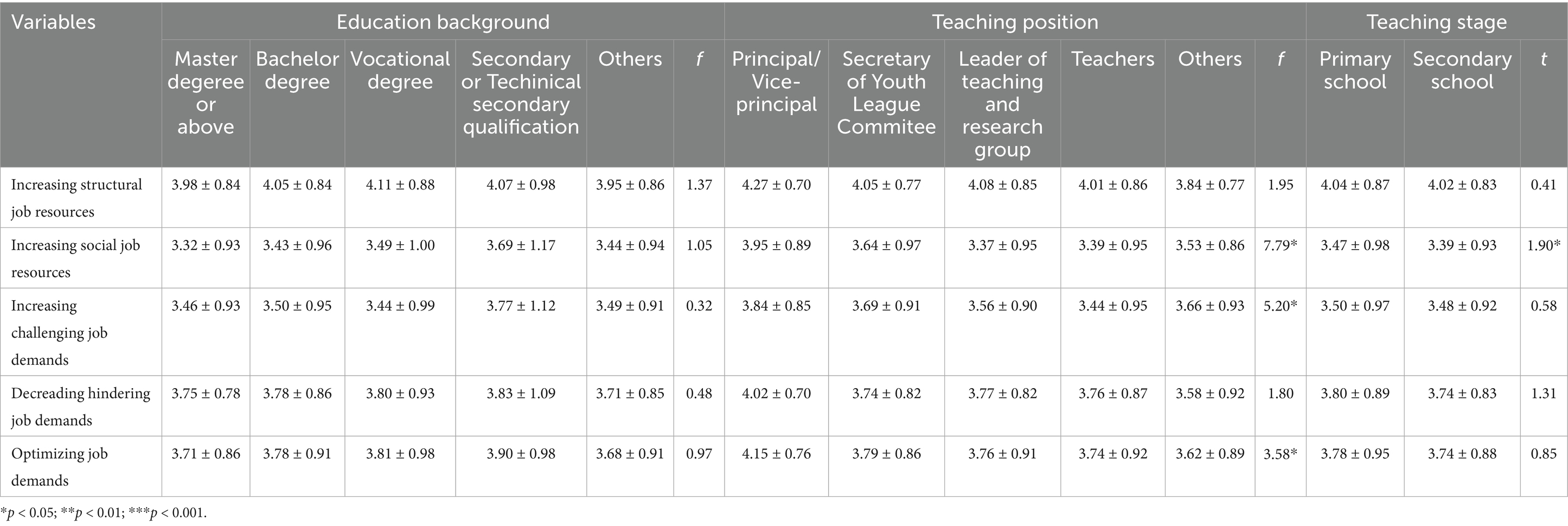

Table 4. Comparison of differences in the five dimensions of job crafting based on demographic variables (education background, teaching position, and teaching stage).

Firstly, no significant differences were found in overall job crafting behaviors between male and female teachers (p = 0.78 > 0.05). However, gender differences emerged in specific dimensions. Male teachers scored significantly higher than female teachers in both increasing social job resources (M_male = 3.50, SD = 0.97 vs. M_female = 3.39, SD = 0.95) and increasing challenging job demands (M_male = 3.57, SD = 0.91 vs. M_female = 3.45, SD = 0.96) (p < 0.05). No significant gender differences were found in the remaining dimensions.

Significant differences were observed in job crafting behaviors based on teachers’ age and teaching experience. Younger and less experienced teachers scored lower in dimensions such as increasing structural job resources, decreasing hindering job demands, and optimizing job demands (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found between age groups or teaching experience levels in increasing social job resources and increasing challenging job demands (p > 0.05).

Regarding educational background, no significant differences were found in overall job crafting behaviors or any of the five dimensions (p > 0.05).

Differences based on teaching position were significant in increasing social job resources, increasing challenging job demands, and optimizing job demands (p < 0.05). School leaders (e.g., school principals and grade leaders) scored higher in these dimensions compared to regular teachers. No significant differences were found in the other two dimensions (p > 0.05).

Teachers from different school types also showed significant differences in increasing structural job resources (p < 0.05), with teachers from district-level schools scoring lower. However, no significant differences were found across the other four dimensions. Lastly, no significant differences were found between middle school and primary school teachers in any aspect of job crafting (p > 0.05), suggesting no variance between these teaching levels.

5 Discussion

5.1 Analysis of descriptive statistics results for teachers’ job crafting

The mean score for teachers’ overall job crafting in the present study (M = 3.69) demonstrated an above-average level of job crafting behavior. Similar findings have been reported among rural primary teachers in China (M = 3.87), suggesting that Chinese teachers are increasingly proactive in reshaping their work to meet personal and professional needs (Sun and Du, 2023). This job crafting tendency can be explained through Chinese cultural context. Confucianism and Zhong Yong (The Doctrine of the Mean) emphasize harmony between individuals and the collective, as well as values of responsibility and ethical conduct, all of which positively influence job crafting in China (Hu et al., 2017). Specifically, Confucianism is found to enhance both job crafting through the mechanism of psychological contract fulfillment; that is, when teachers feel their moral expectations and reciprocal obligations are met, they are more likely to engage in job crafting behaviors (Liu and Zhang, 2022). Thus, Chinese teachers’ job crafting often prioritizes group congruence and meaningful engagement rather than radical change.

Across dimensions, the highest scores were observed in increasing structural job resources, echoing prior research (Zhao et al., 2021). This likely reflects the strong emphasis on self-improvement and mastery in Chinese educational culture (Li, 2009). By contrast, lower scores were found in increasing challenging job demands and increasing social job resources. Several cultural and organizational factors may account for this pattern. Norms of modesty and risk-avoidance can discourage teachers from seeking out extra challenges or social interactions that might be perceived as overstepping boundaries or “showing off” (Liu and Zhang, 2022), while traditional respect for hierarchy and seniority may also limit junior teachers’ willingness to request support or propose challenging new initiatives (Truong et al., 2017). Furthermore, especially in rural settings, limited collaborative structures and heavy workloads constrain teachers’ opportunities to cultivate social resources or pursue initiating new tasks (Li et al., 2023).

5.2 Analysis of differences in job crafting among demographic variables for teachers

The study revealed that there were no significant differences in overall job crafting behaviors between male and female teachers, which aligns with findings from both domestic and international studies (Miraglia et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2021). Social feminism theory suggests that when men and women possess similar attributes, they tend to achieve comparable job performance levels (Black, 2019). Kanter (2008) further argued that observed gender differences are often more reflective of organizational structures than individual characteristics. Gender differences in job crafting strategies are primarily shaped by variations in organizational culture, societal factors, and environmental influences such as organizational type and corporate culture (Ali et al., 2020).

A deeper analysis of specific job crafting behaviors revealed that male teachers were more inclined to engage in strategies that increase social and challenging job resources. Ali et al. (2020) similarly found that male managers were more proactive in interacting with peers and engaging in exploratory activities, which enhanced job performance. This tendency could be explained by the fact that, in career development, men generally find it easier to handle challenging work experiences and are more driven by career success (Xue et al., 2021). Gender role theory supports this by suggesting that men use their work roles to construct their self-concept, seeking opportunities that allow them to expand their competencies. By engaging in job crafting strategies that enhance social resources, men aim to build professional networks that increase work efficiency and contribute to a greater sense of job meaning and achievement (Tims and Bakker, 2010). Additionally, statistics from the Ministry of Education in 2020 indicate that while male teachers constitute less than 30% of the teaching workforce, they hold a disproportionately high percentage of senior administrative positions (Zuraik et al., 2020). This may provide male teachers with greater job autonomy and access to resources, enabling them to explore more challenging opportunities and collaborate with peers.

The study also found that age and teaching experience were positively correlated with overall job crafting behaviors. Teachers who were slightly older and had more teaching experience tended to score higher on job crafting. This finding contrasts with the results of Rudolph et al. (2017), who reported a negative or no correlation between age and job crafting. However, Tornau and Frese (2013) found a positive link between personal growth initiative and age. Our findings suggest that older teachers with more experience are better positioned to engage in job crafting due to their established professional identity, passion for education, and high achievement motivation. With accumulated teaching experience, these teachers have a greater sense of work meaning and value, which drives their motivation to align their roles with personal strengths (Griep et al., 2022; Li and Tang, 2022; Ingusci et al., 2016). Additionally, older and more experienced teachers possess greater autonomy and flexibility in adjusting their tasks, which allows them to engage more in job crafting, such as reducing and optimizing demands (Li et al., 2022).

5.3 Analysis of job crafting differences among school characteristics for teachers

Regarding job crafting based on school characteristics, the study found that school administrators (principals and vice-principals) scored higher in increasing social job resources, increasing challenging job demands, and optimizing job demands. This may be due to several factors. First, according to self-determination theory, principals and vice-principals typically have more job autonomy and control over their tasks, which enables them to engage in job crafting behaviors that increase challenging job demands (Ghitulescu, 2006; Ryan and Deci, 2020). Previous research by Harju et al. (2016) has shown that increasing challenging job demands enhances work engagement and promotes additional job crafting behaviors. Furthermore, job autonomy, as both a flexible work resource and external environmental resource, allows school administrators to feel supported by senior administrators and stakeholders, fostering positive work experiences and collaborative efforts (Chang et al., 2015).

Additionally, teachers in positions of leadership, such as school administrators, are likely to have greater career planning awareness and work adaptability, which enable them to manage complex job demands effectively. They are better equipped to prioritize tasks, embrace challenges, and continuously acquire new skills, thereby enhancing their job crafting behaviors and their adaptability in the workplace.

The study also identified significant differences in job crafting behaviors based on school type, specifically in increasing structural resources. Teachers in township schools scored higher, while those in district-level schools scored lower. These findings contradict some earlier research, which suggested that rural teachers generally engage more in job crafting than their urban counterparts (Zhao and Li, 2019). The discrepancy may be explained by sample size variations and differences in school classifications. Taking China’s educational context into consideration, several factors might contribute to these results. Township schools often face more infrastructure and resource limitations than urban schools, but these challenges can create unique career growth opportunities for teachers. This may encourage township teachers to adopt proactive strategies, such as adapting course content to meet the needs of their students, incorporating flexible curriculum adjustments, and localizing teaching methods (Wang, 2018; Zeng and Gao, 2018). Additionally, recent policies have bolstered township schools by providing additional resources, including equipment, funding, and personnel, which enhances the capacity for structural job crafting (Xue et al., 2021).

In contrast, district-level schools, despite being positioned as educational research institutions, often struggle with policy constraints and resource limitations. These schools may not receive the same level of support as provincial or municipal schools, making it more difficult for teachers to engage in meaningful job crafting (Li, 2018; Li, 2003). This lack of distinctive advantages may limit the extent to which teachers in district-level schools can engage in job crafting, especially in the areas of structural resources and challenging job demands.

6 Limitations and future directions

While this study provides valuable insights into the demographic and job characteristic differences in job crafting among primary and secondary school teachers, it is important to acknowledge the limitations inherent in its design. This research utilized a cross-sectional design, which captures a snapshot of teachers’ job crafting behaviors at a single point in time. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study restricts our ability to draw causal inferences or observe changes over time. To gain deeper and more nuanced insights, future research should consider employing longitudinal designs or other robust methodologies that can track changes in job crafting behaviors and better establish causal relationships.

Moreover, while this study identified gender differences in job crafting approaches, it did not delve into the underlying mechanisms driving these differences. Future research could further explore the role of gender within various social contexts to better understand how social, cultural, and organizational factors may shape male and female teachers’ job crafting behaviors. This would help to clarify the complexities surrounding gender differences in job crafting and contribute to more inclusive models of teacher professional development.

Additionally, this study focused on the influence of demographic and school characteristic variables on job crafting behaviors, but previous research suggests that other situational factors also play a significant role. Factors such as school climate, school culture, leadership styles, career growth opportunities, and teacher autonomy may all contribute to shaping teachers’ job crafting behaviors. Future studies that explore these additional antecedents could provide a more holistic view of the factors that influence job crafting and offer practical recommendations for fostering supportive environments that encourage teachers to engage in job crafting.

7 Conclusions and implications

This study highlighted significant variations in job crafting behaviors among teachers, influenced by factors such as gender, age, years of teaching experience, teaching position, and school type. These findings provide valuable practical insights that can inform strategies to enhance teacher job crafting and professional development.

Firstly, the study revealed that age and years of teaching experience are key factors that influence job crafting behaviors. Older and more experienced teachers were found to engage more actively in job crafting, suggesting that these teachers have a deeper understanding of their roles and greater autonomy in adapting their tasks. Based on these findings, school administrators could consider establishing professional learning communities (PLCs) to facilitate the exchange of job crafting strategies between experienced and newer teachers. Such platforms would allow for mentoring relationships, knowledge sharing, and collaborative problem-solving, thereby fostering a culture of continuous professional growth.

Secondly, the study found that teachers’ teaching positions within the school, such as administrative roles, significantly impact their job crafting behaviors. School administrators who hold leadership positions tend to engage in more proactive job crafting, likely due to their increased job autonomy and control over task decisions. To further enhance job crafting behaviors among teachers, school leaders should focus on empowering teachers by promoting autonomy and providing both formal and informal leadership opportunities. Offering teachers greater control over their work and leadership roles could inspire them to engage more deeply in job crafting, ultimately contributing to enhanced job satisfaction and professional development.

Furthermore, this nuanced pattern of the present study underscores that job crafting among Chinese teachers is an adaptive, culturally embedded process through which they navigate demographic and contextual challenges to sustain meaningful professional lives. The relatively strong tendency to increase structural job resources reflects teachers’ emphasis on self-improvement and mastery. Professional development programs can therefore build on this strength by offering workshops, mentorship, and leadership training that enhance autonomy, skill variety, and reflective practice. In parallel, reducing administrative burdens and providing flexible scheduling will create the time and capacity necessary for teachers to actively pursue professional growth.

By contrast, the comparatively lower engagement in increasing social job resources and increasing challenging job demands highlights areas where targeted support is needed. Previous research has demonstrated that engaging in challenging tasks serves as a key mechanism linking teachers’ formal professional development with informal, practice-based learning (Huang et al., 2025b). Strengthening collegial networks through professional learning communities, structured peer-mentoring, and cross-school exchanges can help normalize collaboration and make help-seeking less risky in hierarchical settings. At the same time, embedding opportunities for experimentation—such as small-scale innovation projects, curriculum design initiatives, or interdisciplinary collaborations—can encourage teachers to assume challenging responsibilities within a safe and supportive environment. Aligning recognition and evaluation systems to value collaborative contribution and responsible risk-taking further reinforces such behaviors.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Hong Kong Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XH: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, F. H., Ali, M., Malik, S. Z., Hamza, M. A., and Ali, H. F. (2020). Managers’ open innovation and business performance in SMEs: a moderated mediation model of job crafting and gender. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 6:89. doi: 10.3390/joitmc6030089

Bindl, U. K., and Parker, S. K. (2011). “Proactive work behavior: forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations” in APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol 2: Selecting and developing members for the organization. ed. S. Zedeck (Washington: American Psychological Association), 567–598.

Black, N. (2019). Social feminism. New York, USA: Cornell University Press. doi: 10.7591/j.ctvr7f5fc

Chang, Y., Leach, N., and Anderman, E. M. (2015). The role of perceived autonomy support in principals’ affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 18, 315–336. doi: 10.1007/s11218-015-9303-7

Day, C., and Sachs, J. (2004). “Professionalism, performativity and empowerment: Discourses in the politics, policies and purposes of continuing professional development”, In International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers, eds C. Day and J. Sachs (Maidenhead: Open University Press), 3–32.

Demerouti, E., and Peeters, M. C. W. (2018). Transmission of reduction-oriented crafting among colleagues: a diary study on the moderating role of working conditions. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 91, 209–234. doi: 10.1111/joop.12196

Dewitt, B., Fischhoff, B., Davis, A. L., Broomell, S. B., Roberts, M. S., Hanmer, J., et al. (2019). Exclusion criteria as measurements II: Effects on utility functions. Med Decis Making, 39, 704–716. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19862542

Dreer, B. (2022). Teacher well-being: investigating the contributions of school climate and job crafting. Cogent Educ. 9:2044583. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2044583

Elliot, A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motiv. Emot. 30, 111–116. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7

Ghitulescu, B. E. (2006). Shaping tasks and relationships at work: Examining the antecedents and consequences of employee job crafting ’ (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. ProQuest. Web. (Pennsylvania: United States).

Griep, Y., Vanbelle, E., Van den Broeck, A., and De Witte, H. (2022). Active emotions and personal growth initiative fuel employees’ daily job crafting: a multilevel study. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 25, 62–81. doi: 10.1177/23409444211033306

Harju, L. K., Hakanen, J. J., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. J. Vocat. Behav. 95, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.002

Hu, Q., Jiao, C. Y., Zhou, M. Q., and Yu, J. Z. (2017). Zhong – Yong job crafting research. Psychol. Explor. 37, 459–464.

Hu, Q., Taris, T. W., Dollard, M. F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2020). An exploration of the component validity of job crafting. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 29, 776–793. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2020.1756262

Huang, X., Sun, M., and Wang, D. (2022). Work harder and smarter: the critical role of teachers’ job crafting in promoting teaching for creativity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 116:103758. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103758

Huang, X., Wang, C., Lam, S. M., and Xu, P. (2025a). Teachers’ job crafting: the complicated relationship with teacher self-efficacy and teacher engagement. Prof. Dev. Educ., 51, 625–642. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2022.2162103

Huang, S., Yin, H., and Lv, L. (2019). Job characteristics and teacher well-being: the mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 39, 313–331. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1543855

Huang, X., Zhang, S., Sun, M., Kouhsari, M., and Wang, D. (2025b). Uncovering relationships between formal and informal learning: unveiling the mediating role of basic need satisfaction and challenge-seeking behavior. J. Workplace Learn. 37, 1–18. doi: 10.1108/JWL-01-2024-0018

Ingusci, E., Callea, A., Chirumbolo, A., and Urbini, F. (2016). Job crafting and job satisfaction in a sample of Italian teachers: the mediating role of perceived organizational support. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 9, 675–687. doi: 10.1285/i20705948v9n4p675

Li, J. (2003). Teaching research: how to adapt to the needs of curriculum reform. Youth Teachers 2003, 53–56.

Li, J. (2009). “Learning to self-perfect: Chinese beliefs about learning” in Revisiting the Chinese learner: Changing contexts, changing education. eds. C. K. K. Chan & N. Rao. (Netherlands: Springer), 35–69.

Li, M. (2018). A case study on the functions of county (district)-level teaching research institutions under the background of curriculum reform (master’s thesis) : East China Normal University. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201901&filename=1018820914.nh

Li, J., Flores, L. Y., Yang, H., Weng, Q., and Zhu, L. (2022). The role of autonomy support and job crafting in interest incongruence: a mediated moderation model. J. Career Dev. 49, 1181–1195. doi: 10.1177/08948453211033903

Li, Q., Lin, Y., Wang, Q., and Wang, S. (2023). ‘‘Thriving’ or ‘retreating’: a qualitative study on chinese rural teachers’ workload and job crafting mechanism’. Journal of East China Normal University (Educational Sciences) 41:38.

Li, H., and Tang, K. (2022). The impact of work resources on teachers’ competence in compulsory education: the mediating role of job crafting. Teach. Educ. Res. 34, 64–70. doi: 10.13445/j.cnki.t.e.r.2022.01.010

Liu, L., and Zhang, C. (2022). The effect of confucianism on job crafting using psychological contract fulfilment as the mediating variable and distributive justice as the moderating variable. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 15, 353–365. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S343927

Loughran, J., and Hamilton, M. L. (2016). Developing an understanding of teacher education. International Handbook Teacher Education 1, 3–22. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-0366-0_1

Lyu, X., and Fan, Y. (2020). Research on the relationship of work-family conflict, work engagement, and job crafting: a gender perspective. Curr. Psychol. 41, 1767–1777. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00705-4

Ma, L. N. (2022). The double-edge sword effects of workload to preschool education teachers—multiple mediation models based on withdrawal and job crafting, Teach. Educ. Res, 34, 69–76. doi: 10.13445/j.cnki.t.e.r.2022.04.016

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2010). ‘The national medium- and long-term education reform and development plan outline (2010–2020). Available online at: https://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A01/s7048/201007/t20100729_171904.html (Accessed July 4, 2025).

Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. (2011). Opinions on strengthening teacher training in primary and secondary schools (teacher [2011] no. 1) Ministry of Education. Available online at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7034/201101/t20110104_146073.html (Accessed January 4, 2025).

Miraglia, M., Cenciotti, R., Alessandri, G., and Borgogni, L. (2017). Translating self-efficacy into job performance over time: the role of job crafting. Hum. Perform. 30, 254–271. doi: 10.1080/08959285.2017.1373115

Pang, N. S. K., Wang, T., and Leung, Z. L. M. (2018). “Educational reforms and the practices of professional learning community in Hong Kong primary schools” in Global perspectives on developing professional learning communities eds. N. S. K. Pang and T. Wang. (New York: Routledge), 39–55.

Peral, S., and Geldenhuys, M. (2016). The effects of job crafting on subjective well-being amongst south African high school teachers. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 42, 1–13. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v42i1.1378

Qi, Y. J., and Wu, X. C. (2016). The development of job crafting questionnaire of primary and secondary school teachers. Studies Psychology Behavior 14, 501–506.

Qi, Y. J., Wu, X. C., and Wang, X. L. (2016). Job crafting and work engagement in primary and secondary school teachers: a cross-lagged analysis. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 24, 935–938. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.05.037

Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., and Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: a meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 102, 112–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.06.004

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101860. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). ‘The 14th five-year plan for National Economic and social development of the People's Republic of China and the long-range objectives for 2035. Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm (Accessed July 7, 2025).

State Council of the People's Republic of China. (2012). ‘The state council's opinions on strengthening the construction of the teacher workforce (Guo fa [2012] no. 41) ’. Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2012-09/07/content_5390.htm (Accessed July 7, 2025)

Sun, R., and Du, P. (2023). How does job crafting impact on career commitment of rural teachers? Best Evidence Chinese Educ. 14, 1751–1755. doi: 10.15354/bece.23.ar055

Tims, M., and Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: towards a new model of individual job redesign. S. Afr. J. Ind. Psychol. 36, 1–9. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., and Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

Tornau, K., and Frese, M. (2013). Construct clean-up in proactivity research: a meta-analysis on the nomological net of work-related proactivity concepts and their incremental validities. Appl. Psychol. 62, 44–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00552.x

Truong, T. D., Hallinger, P., and Sanga, K. (2017). Confucian values and school leadership in Vietnam: exploring the influence of culture on principal decision making. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 45, 77–100. doi: 10.1177/1741143215607877

Wang, G. (2018). A study on the support path of rural teachers’ professional development [master’s thesis], Southwest University. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFDLAST2019&filename=1018859749.nh

Wang, Y. B., Jiang, J., and Mei, T. (2023). On the influence of challenging-obstructive pressure on the reshaping of rural teachers’ work—multiple mediating effects of self-efficacy and emotional commitement. Educ. Res. Mon. 1, 89–97. doi: 10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2023.01.003

Xue, G., Zhao, X., and Li, L. (2021). The impact of career growth opportunities on work well-being among primary and secondary school teachers: the mediating role of job crafting. Journal of Guizhou Normal University (Natural Science Edition) 39, 115–122.

Zeng, X., and Gao, Z. (2018). Empowerment and enablement: the path of teacher team development in rural small-scale schools under the background of rural revitalization: a survey based on the implementation of the ‘rural teacher support program’ in 12 counties across 6 provinces in central and western China. Journal of Central China Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition) 57, 174–187.

Zhao, X. Y., Cui, B., and Xue, G. Y. (2021). Relationship among perception of salary system, job crafting and career satisfaction of primary and secondary school teachers. Journal of Guizhou Normal University (Natural Sciences) 39, 113–118. doi: 10.16614/j.gznuj.zrb.2021.05.019

Zhao, X., and Li, F. (2019). The relationship between perceived organizational support, job crafting, and subjective career success of primary and secondary school teachers. Teach. Educ. Res. 31, 15–21. doi: 10.13445/j.cnki.t.e.r.2019.02.003

Zheng, C., Jiang, Y., Zhang, B., Li, F., Sha, T., Zhu, X., et al. (2023). Chinese kindergarten teachers’ proactive agency in job crafting: a multiple case study in Shanghai. Early Child. Educ. J. 52, 639–654. doi: 10.1007/s10643-023-01455-1

Zuraik, A., Kelly, L., and Perkins, V. (2020). Gender differences in innovation: the role of ambidextrous leadership of the team leads. Manag. Decis 58, 1475–1495. doi: 10.1108/MD-10-2019-1418

Appendix

Keywords: primary and secondary school teachers, job crafting, descriptive analysis, demographic factors, quantitative research

Citation: Zhang S, Huang X and Wang C (2025) Exploring job crafting behaviors among primary and secondary school teachers in China: a descriptive analysis. Front. Educ. 10:1588036. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1588036

Edited by:

Anh-Duc Hoang, RMIT University Vietnam, VietnamCopyright © 2025 Zhang, Huang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xianhan Huang, eGhodWFuZ0BlZHVoay5oaw==

Shiyu Zhang

Shiyu Zhang Xianhan Huang

Xianhan Huang Chan Wang

Chan Wang