- King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Purpose: This study examines the process of using analytic rubrics in higher education, focusing on students in a writing course for basic users of English, the resources they employ as they use the rubric, and the benefits they perceive from it.

Method: The study involved 13 students (N = 13) enrolled in a basic English writing course. After completing the course, semi-structured interviews and stimulated recall sessions were conducted with participants. The focus was on understanding their use of the analytic rubric in their writing process and the resources they utilized, such as smartphone apps, the Grammarly website, and both mobile and desktop versions of MS Word.

Findings: The results indicated that the students exhibited a writing model, comprising recursive and tangled five steps. Long-term benefits included improved self-efficacy, writing skills, satisfaction, and task-management skills. In the short-term, the rubric helped clarify the requirements, served as a benchmark for their writing, and highlighted their strengths and weaknesses in the writing process.

Originality: This study contributes to the limited research on the use of analytic rubrics in EFL contexts in higher education, providing insights into the writing process of basic English learners and the benefits of rubric use in language learning.

Introduction

The use of rubrics enhances students’ educational achievement and the feedback process across different disciplines of higher education (Reddy and Andrade, 2010). When a rubric is used as an instructional tool, it can improve the learning process, especially in formative assessments (Jonsson and Svingby, 2007; Reddy, 2007). As, instructional tools, rubrics provide students with informative feedback that includes a detailed evaluation of their in-progress products (Andrade, 2000). The use of rubrics to support students’ formative assessment enhances students’ final products and skill development while also improving their learning engagement and lifelong learning capabilities (English et al., 2022). Rubrics can effectively improve learning processes if properly implemented and designed (Panadero and Jonsson, 2013). These potential benefits have prompted researchers to determine the good and bad practices of students and educators vis-à-vis rubrics use (Chan and Ho, 2019), Saudi English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ perspectives on rubrics for assessing students’ writing in class (Alamri and Adawi, 2021), and the validation of rubrics as tools to assess the argumentative writing of language students in an English for an academic purposes (EAP) program (Uludag and McDonough, 2022). However, educators have not widely embraced this tool in writing assessment due to challenges with the language used in rubrics, as instructors and students may interpret rubric terms differently, viewing them as vague and ambiguous (Li and Lindsey, 2015). Regardless, the claims raised against the effectiveness of the use of rubrics have not been based on scientific data but on personal experiences and anecdotal evidence as well as evidence drawn from studies on the rubrics’ use for summative rather than formative purposes (Panadero and Jonsson, 2020).

The purpose of using rubrics determines the time required to introduce them in the learning process. For summative purposes, such as grading, students are not allowed to view the rubric as they compose their work (Panadero and Jonsson, 2020). However, for formative purposes, rubrics are introduced to students as they compose their work (Panadero and Jonsson, 2013). Thus, the early introduction of rubrics for formative purposes can enhance rubrics’ benefits for student achievement (English et al., 2022; Panadero and Jonsson, 2020). Prior studies have supported this claim, asserting that allowing students to view the rubrics before composing their assignments improves writing performance and achievement (Andrade, 2000; Howell, 2011; Ragupathi and Lee, 2020; Reynolds-Keefer, 2010). Besides introducing rubrics early for formative purposes, delivering rubrics on the same online platform where assignments are posted could also influence students’ learning processes. Embedding a rubric in an online platform or a learning management system (LMS) such as Blackboard, where students can view the rubric before composing the assignment, supports assessment and provides students with time to reflect on the assignment (Atkinson and Lim, 2013). However, little research has been conducted on the students’ perception of how rubrics’ integration into assignments (by being posted on an online platform for formative purposes) affects their writing performance in an EFL context, especially in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, there is limited information on resources students draw on and the perceived benefits of rubrics on virtual platforms in Saudi Arabia.

Literature review

Rubric definition and types

A rubric is a document that articulates and describes a particular assignment’s quality, ranging from poor to excellent (Andrade, 2000). It serves as both a guide containing detailed criteria for scoring assignments or academic papers and a tool to describe an attainment level within a scale (Crusan, 2015; Ragupathi and Lee, 2020). Rubrics may be holistic or analytical. Holistic rubrics are concerned with scoring the overall final product, whereas analytic rubrics are concerned with scoring multiple traits and features of a given assignment (Rezaei and Lovorn, 2010). For instance, a holistic rubric could demand that the instructor to provide an overall score for a particular product to students, thereby serving as a scoring rubric. Conversely, an analytic rubric could demand that the instructor rate the individual features of a student’s performance in a specific product, thereby serving as an instructional rubric (Brookhart, 2013; Brown, 2018; Panadero and Jonsson, 2020; Ragupathi and Lee, 2020). Thus, analytic rubrics provide the scorer with an informative tool to provide students with details about their writing performance, strengths, and weaknesses (Imbler et al., 2023). An analytic rubric in higher education consists of a matrix with two dimensions: one identifying the assessment criteria and the other specifying the attainment level in numerical values, with a detailed description of each value (Bennett, 2016). Analytic rubrics are primarily used for formative assessments (Brookhart, 2013; Brown, 2018; Jonsson and Svingby, 2007). Rubrics can also be general or task-specific. General rubrics assess the general competence of the student’s production in a task, while task-specific rubrics focus on specific content (Brookhart, 2013, 2018).

In language learning, the term ‘rubric’ has been used interchangeably with the term ‘rating scale’ to evaluate students’ written performance and grade different performance features separately (Eckes et al., 2016). Rubrics in the EFL context consist of a matrix stating the quality level, criteria, descriptors, and scores (Alaamer, 2021; Wang, 2017). From these descriptions, analytic rubrics appear to be the most common in language learning. Thus, in this study, an analytic rubric was used and presented to students with an assignment for formative purposes on the Blackboard LMS.

Studies related to rubrics’ use in education

Theoretical and empirical studies have reported on the effect of rubric use on student performance. These studies have explored how rubrics serve formative purposes or function as instructional tools. When teachers use a rubric as an instructional tool, it can promote learning by clarifying the criteria and the teacher’s expectations for students, thereby regulating students’ learning, developing their self-efficacy and self-assessment, lowering their anxiety levels, and providing timely feedback (Jonsson and Svingby, 2007). Higher education students value rubric use for formative purposes, illustrating the goals of their work, guiding their progress, and scoring their work fairly and transparently (Reddy and Andrade, 2010). Ragupathi and Lee (2020) listed several benefits of rubrics for students’ learning processes, including assisting students recognize their own strengths and weaknesses by providing them with detailed, personalized feedback and making them reflect on their product; improving students’ self-efficacy by providing them with the cognitive skills to improve in their work, thus helping them achieve their potential and improving their subsequent assignments; providing them with transparent, comprehensible and clear benchmarks to assess their work; and assisting them in clarifying the assignment expectations.

In a more recent theoretical study, Panadero et al. (2023) conducted a meta-analysis of 23 studies that examined rubric usage’s effects on students’ academic performance, self-regulated learning, and self-efficacy. They found that rubric usage positively impacted students’ academic performance and had a smaller positive effect on their self-efficacy and self-regulated learning.

Empirical studies have examined how rubrics, as instructional tools, affect students’ perceptions during their learning processes. Utilizing rubrics in the classroom to support the learning process can clarify teachers’ expectations for their students, aid the students’ planning process, lower students’ anxiety levels, assist them in revising their assignments, and encourage them to reflect on their progress (Andrade and Du, 2005). Reynolds-Keefer (2010) similarly asserted that rubrics assisted pre-service teachers throughout their writing process and helped them predict their instructors’ expectations.

Other empirical studies have examined the effects of introducing rubrics to students via online platforms. For example, Atkinson and Lim (2013) examined 55 students’ perceptions regarding embedding rubrics in an LMS to provide formative feedback for a particular course. They found that students recommended the continuous use of rubrics and appreciated how the feedback improved their subsequent assignment, specified their achievement levels, and identified areas needing improvement.

More recent empirical studies have examined the effect of rubrics on students’ judgments on online platforms (Gyamfi et al., 2022; Krebs et al., 2022). Rubrics can enhance the accuracy of students’ self-assessment judgments and reduce cognitive subjective judgments when evaluating the quality of their performance in writing scientific abstracts (Krebs et al., 2022). Additionally, rubrics can positively affect undergraduates’ evaluative judgments when they evaluate the quality of the learning resources provided to them and not the quality of their own writing (Gyamfi et al., 2022).

Studies related to rubrics use in language education

Studies on the use of rubrics in language education are rare; further, language learning has scarcely been reported in disciplines where rubrics are used in higher education with undergraduates (Reddy and Andrade, 2010). A few recent empirical studies have investigated the effectiveness of rubrics in the EFL and English as a second language (ESL) context. In one study, using a rubric as an instructional tool improved the quality of written summaries among adults taking an intensive ESL course in the U.S. (Becker, 2016). Similarly, students in an EFL writing course in China viewed a rubric as a formative tool for aiding them in self-regulating their planning and goal-setting, self-monitoring their progress, and encouraging them to reflect on their own learning path (Wang, 2017). Besides writing courses, rubrics have also been used in oral assessments in EFL contexts. For example, He et al. (2022) explored the motivation of language students regarding the intensity of rubric use and the factors affecting such use when assessing oral tasks. Their study identified three levels of rubric use intensity: intense, moderate, and loose. The intensity of the students’ efforts was attributed to their prior knowledge of the detailed rubric, their self-efficacy in their own English-language capabilities, and their goals and aspirations to improve their competence in speaking English in public.

The effect of rubrics on students’ writing competencies has also been explored in the Arab world. In Lebanon, Ghaffar et al. (2020) examined how involving students and teachers in constructing rubrics affects students’ writing competency and perceptions of using rubrics as a tool for learning and assessment. Their experimental study involved 55 Lebanese students aged between 12 and 14 years, divided into an intervention and a comparison group. The pre-and post-test scores showed improvements in students’ competency levels in the intervention group. They also showed that students valued rubrics for assisted them in assessing themselves, setting their goals, improving their metacognition and classroom engagement, and enhancing ownership of their learning. In Saudi Arabia, rubrics are used commonly for summative purposes, and their language has been examined (Aldukhayel, 2017). In Aldukhayel’s (2017) study, rubric use was not encouraged, as the surveyed undergraduates did not value using rubrics to assess their writing competency on the midterm and final exams. These undergraduates viewed the rubric’s language as unclear and confusing, stating that the tool failed to clarify their strengths and weaknesses in EFL writing.

The present study

Situated within the studies mentioned in the previous two sections, the current study attempts to describe how adult EFL students use analytic rubrics for formative purposes in composing their written assignments as well as the resources on which they draw. This research is valuable because no prior studies have directly described the process of EFL students’ rubric usage to compose assignments (Ghaffar et al., 2020; Li and Lindsey, 2015). Additionally, it seeks to identify the benefits of using the analytic rubric as an instructional tool on a virtual platform, as perceived by EFL students in Saudi Arabia. This study aims to enhance the understanding of the perceptions of using an analytic rubric on the engagement of EFL students in writing in higher education.

In summary, the present study addresses these questions:

• R1. How do students use an analytic rubric to write their assignments?

• R2. What resources do students draw on when they use the analytic rubric to write assignments?

• R3. What benefits do students perceive when using the analytic rubric to compose their written assignments?

This study was conducted with students who used an analytic rubric in their assignments during a 17-week beginner EFL writing course, taught by a researcher/instructor at a Saudi university. Data collection was conducted shortly after the completion of the course in January 2022, for ethical reasons. The researcher was the instructor; therefore, all students of the writing course were invited to participate after completing their course and receiving their grades to ensure that their grades will not be affected by enrolling in the study. The writing course was designed to teach students the basic rules of English writing skills and help them reach the A2 English level in the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2020). The instructor demonstrated the essential linguistic writing input required to compose sentences in paragraphs (including punctuation, capitalization, accurate grammar, etc.) and the various stages of writing (such as prewriting, writing, and editing). Students were required to submit 10 assignments using the Blackboard LMS, covering specific topics over the semester. Two analytic rubrics were provided for the assignments; rubric (1) for the first five assignments and rubric (2) to assess assignments 6–10 (see Supplementary Material). The criteria in the analytic rubric were based on the basics of English writing in the course curriculum. The rubric was made available for students via Blackboard, allowing them access early on, when they planned and composed their written assignments. The instructor demonstrated for the students how to view the rubric before beginning the assignment on Blackboard and welcomed questions regarding these rubrics. After assignments were graded, students could access their specific rubric scores on Blackboard. However, students were not instructed on how to use the rubric to write their assignments nor were they provided with illustrative examples of the rubric criteria.

Methods

Participants

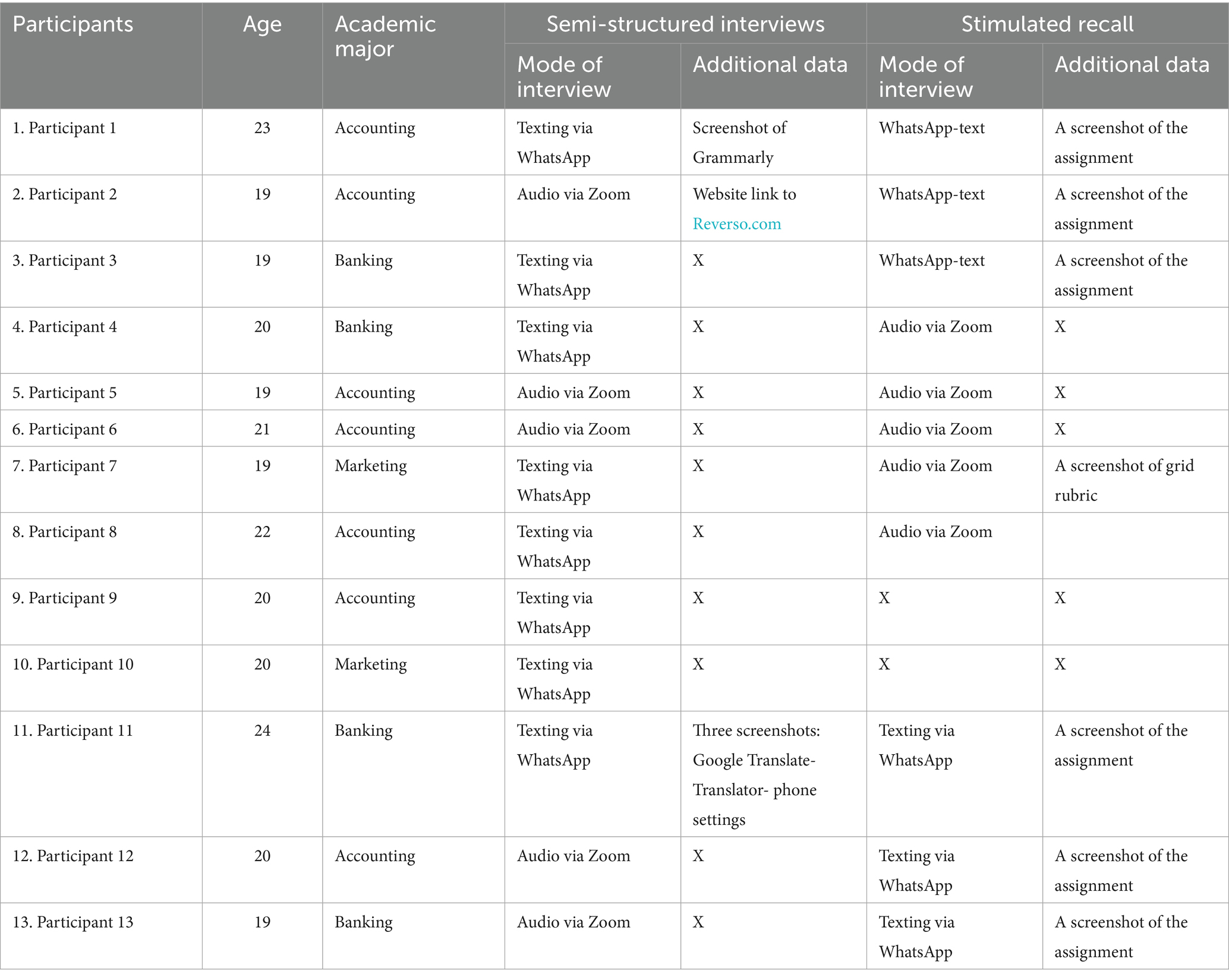

Convenience sampling was adopted to recruit 13 female students (N = 13) for semi-structured interviews. Of these, 11 participated in the stimulated recall session, whereas two withdrew from the study. The students used rubrics to submit assignments in a writing course. Candidates were recruited via email invitations, which included study details and a consent form. These candidates were then invited to participate in the study after completing the course. The participants contacted the researcher and provided their verbal consent to participate. All participants were required to pass an intensive English course designed for the A1 English level, the first level of English in the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2020), before taking the writing course to complete their diploma degree. The students had different majors at a Saudi Arabian university, and their ages ranged from 19 to 24 years. Table 1 illustrates the participants’ profiles, number of participants for each research tool, and the data types provided.

Instruments

The data collection instruments included semi-structured interviews and stimulated recall. Participants could choose to conduct the sessions by text or audio via any application they preferred. All sessions were recorded and documented.

Semi-structured interview

Interviews provide researchers with participants’ nuanced descriptions of a particular situation, their lived experiences, and their own interpretations of a specific phenomenon (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2018). The interviews started with questions about the participants’ general experience using rubrics. Subsequent questions covered their current practices using rubrics to compose their assignments and their interpretations of this process. They were encouraged to describe the resources they drew on as they composed some of their assignments based on the rubrics and how rubric usage affected their linguistic capacity. Thirteen students participated in interviews after completing the course and receiving their grades.

Stimulated recall

Stimulated recall is useful in studying learning processes and has been used by second language researchers to gain insights into individuals’ experiences during a particular event (Hodgson, 2008). This method involves asking participants to describe the activities they engaged in based on the assumption that ‘the best way to model the writing process is to study a writer in action’ (Flower and Hayes, 1981, p. 368). Participants in the stimulated recall session were invited to choose one of the assignments they had produced and submit it via Blackboard along with the scoring rubric to answer two questions. Their written work is believed to have helped these participants retrieve their thoughts and experiences during the event and verbalize them (Dörnyei, 2007). Eleven participants agreed to participate in the stimulated recall sessions after participating in the semi-structured interviews; two of them withdrew from the stimulated recall.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six phases of thematic analysis. This thematic analysis refers to ‘the searching across data set … to find repeated patterns of meaning’ (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 86). In the first phase, I familiarized myself with the data by conducting interviews and stimulated recall sessions, transcribing the audio data, reading and rereading the data along with the attached screenshots, and creating a list of notes about the codes. In the second phase, data were systematically and inductively coded using ATLAS.ti software, while segments of data were tagged with the initial codes to answer the research questions. In the third phase, I searched for themes by sorting all the codes visually, developed an initial thematic map through the network feature of ATLAS.ti software, and reviewed the codes. The network feature allowed me to observe code relationships and rename, describe, merge, and color-code them (Friese, 2014). In the fourth phase, the themes were reviewed for relevance to the coded data and research questions to validate the thematic map. In the fifth phase, themes were defined and named by writing a detailed definition of each theme and subtheme. In the sixth phase, I reported the study results and selected excerpts for use in this study.

Results

Students’ approaches to using the analytical rubric to write their assignments and the resources they drew on

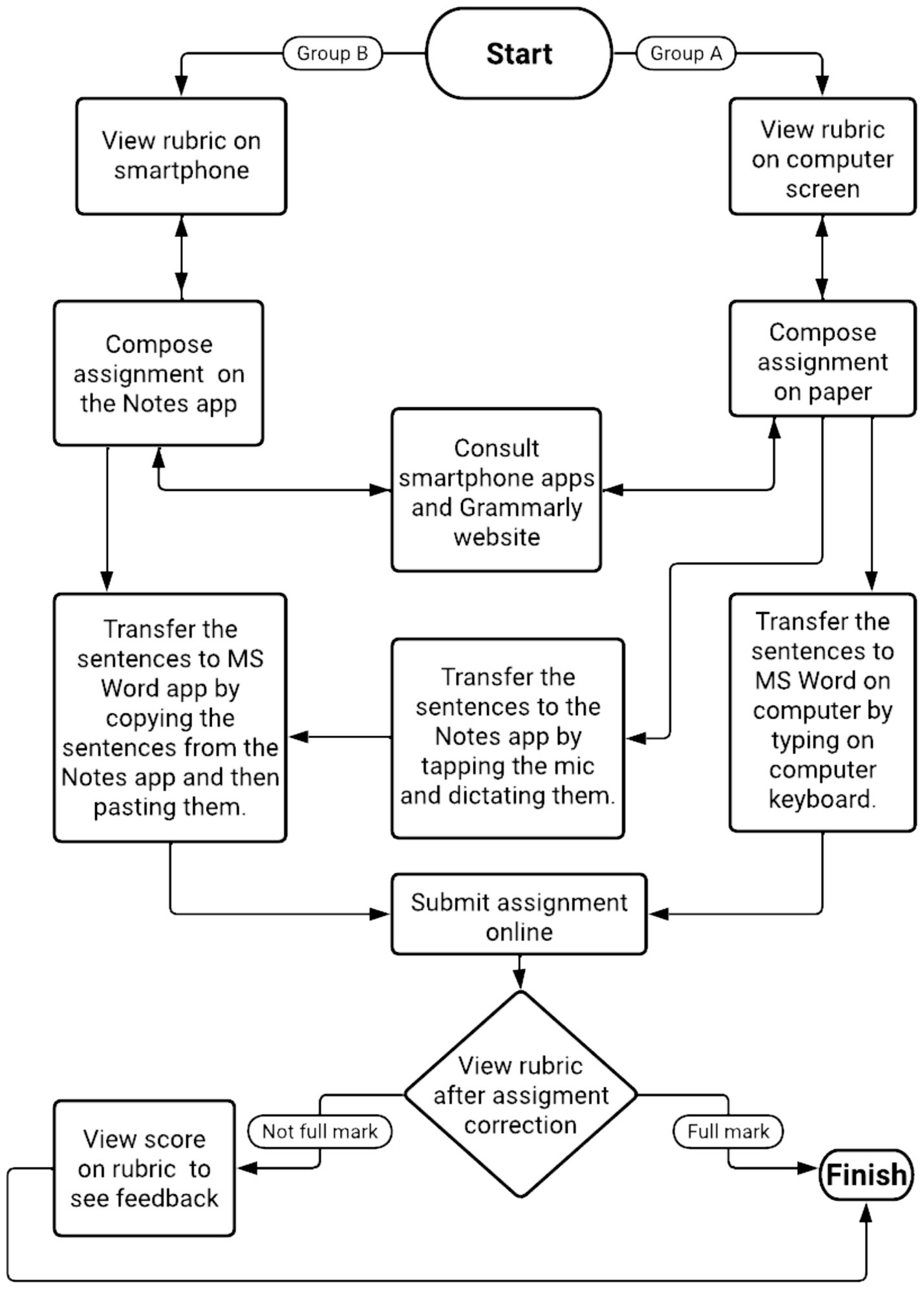

Data analysis revealed a pattern in how students used rubrics while writing assignments. The term ‘model’ will be used to describe their cognitive writing processes, as it refers to ‘a way to describe something, such as composing process, which refuses to sit still for a portrait’ (Flower and Hayes, 1981, p. 368). In this sense, a model represents the process and repeated pattern of students’ engagement in rubric use to compose their assignments. In this model, students drew on resources which depended on the analytic rubric to help produce their written work. These resources are discussed as they were used in the writing model, which consists of the following five steps:

• Step 1: Viewing the rubric.

• Step 2: Composing the assignment.

• Step 3: Transferring the assignment to MS word.

• Step 4: Submitting the assignment online.

• Step 5: Viewing their assignment score.

Figure 1 elucidates the non-linear writing model of students’ use of rubrics in composing their assignments. The arrows indicate the flow of the process. Some components have double-sided arrows while others have one direction.

In Step 1, all students viewed the rubric before they composed their sentence, but the format in which they did so varied. In analyzing the data, the students who viewed the rubric on a computer screen were categorized as Group A, and those who viewed it on their smartphone were Group B. In Step 2, Group A composed their assignments using pen and paper, while Group B composed theirs digitally. It appears that the format in which students draft their assignments determines how they view the rubric before beginning their assignments. Group B students revealed that they tapped the Notes app on their smartphones and composed sentences by touching the keyboard. They enabled features such as spell check, predictive text, and auto-correct to help them write correctly spelled words. Students in both groups used smartphone apps and Grammarly to edit and improve their sentences as they reviewed their writing compositions. They used translation apps such as Reverso, Google Translate, and Microsoft Translator to assist them in finding the equivalents of their desired words in English. Regardless of the format used to draft assignments, students used smartphone apps to help craft and polish their assignments. For instance, one student described the following steps:

• [30/01/2022, 2:24:37 pm] P11: I saw the rubric on my computer and read it. I started writing sentences first, thinking only about choosing the right vocabulary for popular sports.

• [30/01/2022, 2:25:59 pm] R: How did you do this?

• [30/01/2022, 2:28:09 pm] P 11: As per usual. I used a pencil and copybook to erase incorrect vocabulary or grammar. I had my smartphone in my hand too.

• [30/01/2022, 2:28:52 pm] R: Why did you have your smartphone?

• [30/01/2022, 2:32:59 pm] P 11: Oh, you know, I used things to help me translate Arabic into English. I did not have many words in English, but words came to my mind in Arabic. I used Google Translate, although my friends told me about Reverso, which is an accurate app—better for translation.

• [30/01/2022, 2:33:57 pm] P 11: I look at the rubric while I was writing to confirm that I had not missed any points. To remind myself. It is like you are telling me not to forget a certain thing to obtain a high mark (Participant 11, stimulated recall).

A student who viewed the rubric on her smartphone described her process as follows:

When I wrote this assignment, I saw the rubric on the Blackboard app on my smartphone. I then accessed the Notes app and began writing sentences. Google Translate helped me. I used it to learn the meaning of some words in Arabic and copied the words in English and pasted them into the Notes app. I did this to ensure that I did not have any spelling errors. Sometimes, I use Grammarly to check my grammar. In fact, most people use Grammarly. I reviewed the rubric three to four times when I wrote my assignments (Participant 4, stimulated recall).

In Step 3, students transferred their sentences to MS Word in three ways. Group A used two methods: the first involved opening MS Word on a computer to type the sentences, while the second involved opening the Notes app on their smartphones. Students then tapped the mic on the Notes app and dictated their sentences slowly and clearly to ensure correct spelling. However, they had to add punctuation later, as dictation alone does not add punctuation by default. After they finished the dictation, they copied and pasted their sentences into MS Word. Most students reported using MS Word’s features, in both the mobile and desktop versions, to check their spelling, grammar, and punctuation. They noted that MS Word underlines and detects grammatical, spelling, and punctuation errors, providing suggestions. Therefore, they revised their written compositions after they were transferred into MS Word. For example, one student said:

I moved my sentences to the Notes app after I wrote them on paper and later used a microphone to dictate the notes. I held the mic and read sentences correctly and slowly. I made sure that what I said was being written by the software, as opposed to words I did not want. This was faster, but the dictation feature did not include full stops or commas. It was really helpful. I copied and pasted this with MS Word on my smartphone. Super quick. No fuss. MS Word corrected issues such as full stops, commas, and the things the rubric reminded me about (Participant 2, semi-structured interview).

Group B used one method to copy sentences from the Notes app and paste them into MS Word. All students in both groups went back and forth from Steps 1 to 3 to view the rubric; these steps were recursive. A student mentioned the following:

I copied and pasted the sentences from the Notes app into MS Word. I checked if MS Word spotted grammatical mistakes and I corrected them as necessary. The rubric was checked during the last minute. I submitted my assignment if everything looked correct (Participant 7, semi-structured interview).

Students submitted their assignments by attaching the MS Word file to the Blackboard website in Step 4 and viewed their scores in Step 5. If they did not receive full credit, they checked their assignments using the rubric in order to extract feedback. If the students received full credit, they completed the process.

Benefits perceived by students using rubrics when composing their written assignments

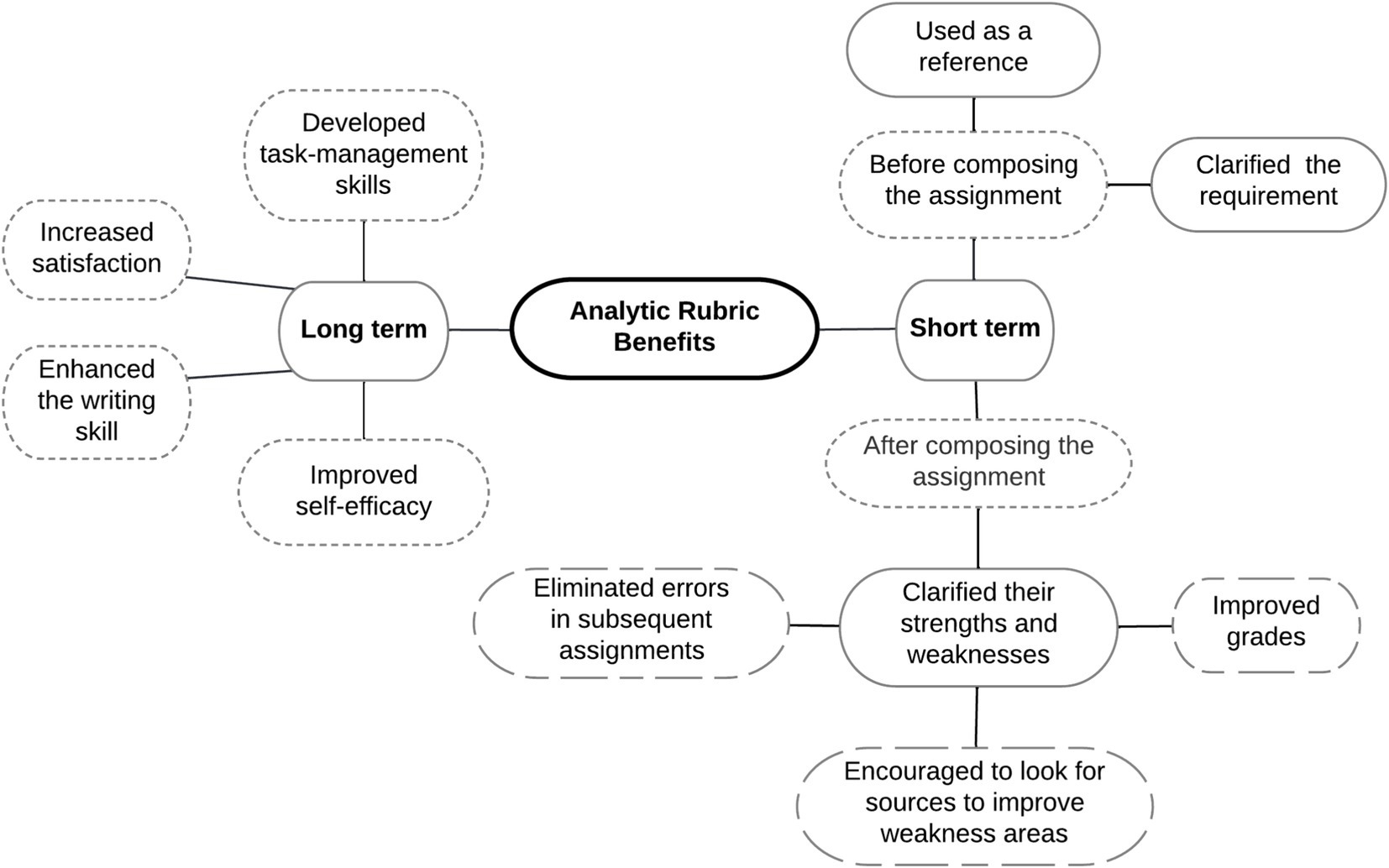

An analysis of the semi-structured interviews revealed that students found rubrics beneficial when composing their written assignments. Some benefits emerged shortly after using the rubrics, while others occurred after a longer period. These are referred to as short-term and long-term benefits, respectively (see Figure 2).

Short-term benefits

Students generally believed that using rubrics when composing assignments provided short-term benefits. They felt that using rubrics before composing the assignment helped them clarify the requirements of tasks and served as a benchmark for their own writing. Additionally, using the rubric after the assignment was scored helped clarify their strengths and weaknesses in writing.

Students valued reading the rubric before drafting each assignment to clarify its requirements in a nutshell, thus making the evaluation transparent. Therefore, rubrics provided students with guidelines on what was expected of them. For instance, one student stated, ‘Reading the rubric made me understand what I needed to write instead of feeling lost. I learned what the teacher wanted and how the assignment would be graded’ (Participant 13, semi-structured interview). Another said, ‘The rubric made beginning writing easy. I learned about what I need to cover. It essentially told me what I had to do to get a full mark’ (Participant 11, semi-structured interview).

Students regarded the rubric as a benchmark while writing and before submitting their assignments. This helped students shape their assignments into high-quality pieces of writing. The following quote explains how a student used the rubric as a reference to guide her as she composed her assignment:

When I felt confused, I looked at the rubric and it reminded me of the standards I had to meet. I also looked at the rubric when I transferred the assignment into MS Word and before I finally submitted it (Participant 10, semi-structured interview).

Students regarded the rubrics detailing the assignment scores as a tool to clarify the strengths and weaknesses of their own writing. This helped eliminate errors in subsequent assignments. For instance, one student stated, ‘I look at the rubric to identify my mistakes and work on them. This way, I avoid making the same mistake in future assignments’ (Participant 5, semi-structured interview).

Students’ recognition of their weaknesses via scored rubrics encouraged them to look for other sources to improve their linguistic competence. Students searched Google and YouTube for basic writing rules. Some explanations were as follows:

I did not receive full marks for punctuation; therefore, I used Google to search for punctuation rules in English. I learned that I had to use full stops after completing each sentence. In class, I learned what a complete sentence is, but I did not connect grammar to punctuation. I used YouTube to watch teachers explain punctuation (Participant 5, semi-structured interview).

The rubric told me that I needed to know that each sentence must have a verb and a subject. I did not know that I needed to be better at this. I searched YouTube and learned about this; since then, I have written complete sentences (Participant 12, semi-structured interview).

In addition to encouraging students to search for other sources, the rubrics helped them improve their grades. For instance:

I took ¼ of the first assignment. I was worried that I would fail the course. I looked at the rubric and knew where I needed to improve. I studied my notes using Google and YouTube. My grades in the subsequent assignments improved—I obtained good grades on the exam (Participant 6, semi-structured interview).

Long-term benefits

Students believed that using rubrics in composing assignments provided them with benefits that were cultivated several weeks after use—that is, long-term benefits. These benefits include students’ improved self-efficacy, enhanced writing skills, increased satisfaction, and better task-management skills.

The students noted that the rubrics improved their self-efficacy. They believed in their ability to produce well-written assignments. They depended on themselves to lead their own learning paths and take responsibility for improving their writing skills. They focused on what was required of them and became attentive to applying the rubric criteria as they composed their assignments. They corrected their errors before submitting their assignments and were able to assess their writing. For instance, one student commented as follows:

Now, I depend on myself and do not ask the teacher why I received this grade. I have become responsible for writing and studying independently. I read the rubric while composing my assignments and estimate my grades before the teacher’s correction (Participant 1, semi-structured interview).

The students observed that the rubrics enhanced their writing skills. They acknowledged that the rubrics helped them learn the basics of writing, reinforce what they had learned, and remain focused on the writing task; they also assisted them in applying writing rules in practice. A student mentioned the following:

I knew English grammar but I did not know how to write connected sentences or paragraphs in English. After becoming accustomed to writing using the rubric, I was surprised to see a considerable improvement in my level. Although I passed this course, I am willing to take it again if allowed, as the rubric has enhanced my abilities (Participant 9, semi-structured interview).

Students reported that using the rubrics in their assignments increased their satisfaction levels. They were pleased with the prompt feedback they received from their assignments based on the rubric. They understood the rubric grading system, as each criterion was described in detail, which made them feel that the grading was fair. For instance, one student commented the following: ‘When I received lower marks, I did not feel like I was treated badly. The teacher used the same rubric to grade us all’ (Participant 3, semi-structured interview). Another student shared the following:

I am happy with my progress. I cannot say whether I deserved better grades based on the feedback I received after submission. I wish I had used rubrics in my prior English courses (Participant 2, semi-structured interviews)

Students also reported that the rubrics assisted them in developing their task management skills. They mentioned that the rubrics helped them save their time and effort by assisting them in staying focused on requirements. The rubrics also encouraged them to plan their notes and organize their thoughts, thus making the writing process more manageable.

Discussion

Students looked at their writing approach as if it were simple and straightforward; however, it was tangled, recursive and multi-layered, which is consistent with Flower and Hayes’ (1981), who argued that writing approaches ‘have a hierarchical, highly embedded organization in which any given process can be embedded within any other’ (p. 366). Students merged traditional writing methods (pen and paper) with innovative methods such as using the microphone function on the Notes app. Their approaches evolved as they adapted their writing process to achieve the desired writing products within the scope of their English competency. They drew on numerous resources, including two technological devices (computers and smartphones), different apps, and MS Word, leveraging their features as needed. Some students used two devices simultaneously. Others used different applications on the same device and navigated from one to another. They engaged in translation processes using smartphone apps to assist them in choosing the appropriate vocabulary. They enabled smartphone features to improve their writing while also making use of the features of MS Word. They drew on smartphone apps and Grammarly to ensure writing sentences that were spelt, punctuated, and structured correctly. Moreover, they used Grammarly to correct their errors and accepted its suggestions without questioning, which is consistent with Koltovskaia’s (2020) finding that L2 students blindly accepted the feedback provided by Grammarly.

This study’s findings align with those by Chan and Ho (2019), who reported that students preferred rubrics for standardizing the evaluation of their work and making it transparent. Moreover, the rubric in this study enhanced students’ understanding of the assignments’ requirements. This is similar to the findings of Reynolds-Keefer (2010), Ragupathi and Lee (2020), Chan and Ho (2019), Andrade and Du (2005), and Panadero and Jonsson (2013), indicating that rubrics assisted students in adjusting their expectations.

Thus, rubric usage assisted students in recognizing their errors and provided them with the opportunity to review the results of their assignments. Similar findings have been documented in the literature, although prior studies have not reported how students benefit from learning about specifics aspects of their performance (Atkinson and Lim, 2013; Imbler et al., 2023; Panadero and Jonsson, 2013; Ragupathi and Lee, 2020). Accordingly, the rubrics improved students’ self-efficacy by assisting them in recognizing the skills they required to improve. This finding is in line with prior studies (Panadero and Jonsson, 2013; Ragupathi and Lee, 2020).

This study’s evidence that rubric-assisted students stay focused on the writing task, thus improving their writing skills, supports Radwan’s (2005) claim that explicit attention to learning a particular linguistic form and constructs enhances learners’ language competency of L2 learners.

Additionally, the rubrics not only helped students stay focused on tasks’ requirements but also encouraged them to organize their thoughts. This finding is in line with prior studies (Wang, 2017), showing that rubrics in EFL writing courses are seen by students as aiding in self-regulating their learning progress. Self-regulated learning refers to students’ activities when they specify goals to be achieved in a specific timeframe and monitor or guide their activities and feelings to fulfill these goals (Andrade, 2019). Along this line, students viewed rubrics as benchmarks for their work, which is consistent with the work of Andrade (2007), who suggested that rubrics are used as a tool by students to self-assess their progress.

Conclusion

The current study described adult EFL students’ usage of rubrics for formative purposes in composing written assignments, as advocated by prior studies (Ghaffar et al., 2020; Li and Lindsey, 2015), while also analyzing the resources they draw on and the benefits they perceive when using analytic rubrics. The findings indicate that the students developed a writing model consisting of five steps that were recursive, tangled, and multilayered. They drew on resources such as smartphone apps, the Grammarly website, and two versions of MS Word. These findings confirmed the need to use analytic rubrics for formative assessments in EFL courses at the A2 English level for both short-term and long-term benefits such as improving students’ self-efficacy, enhancing their writing skills, increasing their satisfaction and developing their task-management skills. It is hoped that the findings of this study will advance our understanding of rubric use in an EFL context and its influence on the actual writing process.

This empirical study had some limitations. First, the students’ experience of using rubrics was relatively scarce, as rubrics had not been previously applied in any course. The students had no experience with rubrics in paper or digital format. Second, the students were at the A2 English level and basic English users. A future study could expand this to include students who have had previous experience with the use of rubrics in assessment and independent users of English. A Third limitation is related to the tools used for data collection, which were based on semi-structured interviews and stimulated recall sessions. Further studies could include eye-tracking to measure students’ own perceptions using rubrics, as advocated by Panadero et al. (2023). Further research could also use screen recordings of participants’ computer or smartphone to trace their process in composing sentences as they view the rubric.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of King Saud University (reference number: KSU-HE-21-820 and 09/12/2021). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

NB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1588046/full#supplementary-material

References

Alaamer, R. A. (2021). A theoretical review on the need to use standardized oral assessment rubrics for ESL learners in Saudi Arabia. Engl. Lang. Teach. 14, 144–150. doi: 10.5539/elt.v14n11p144

Alamri, H. R., and Adawi, R. D. (2021). The importance of writing scoring rubrics for Saudi EFL teachers. Int. Ling. Res. 4, p16–p29. doi: 10.30560/ilr.v4n4p16

Aldukhayel, D. M. (2017). Exploring students’ perspectives toward clarity and familiarity of writing scoring rubrics: the case of Saudi EFL students. Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 1–9. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n10p1

Andrade, H. L. (2019). A critical review of research on student self-assessment. Front. Educ. 4:87. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00087

Andrade, H., and Du, Y. (2005). Student perspectives on rubric-referenced assessment. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 10, 1–11. doi: 10.7275/g367-ye94

Atkinson, D., and Lim, S. L. (2013). Improving assessment processes in higher education: student and teacher perceptions of the effectiveness of a rubric embedded in a LMS. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 29, 651–666. doi: 10.14742/ajet.526

Becker, A. (2016). Student-generated scoring rubrics: examining their formative value for improving ESL students’ writing performance. Assess. Writing 29, 15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2016.05.002

Bennett, C. (2016). Assessment rubrics: thinking inside the boxes. Learn. Teach. 9, 50–72. doi: 10.3167/latiss.2016.090104

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brookhart, S. M. (2013). How to create and use rubrics for formative assessment and grading. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Brookhart, S. M. (2018). Appropriate criteria: key to effective rubrics. Front. Educ. 3:22. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00022

Chan, Z., and Ho, S. (2019). Good and bad practices in rubrics: the perspectives of students and educators. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 533–545. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1522528

Council of Europe (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Crusan, D. (2015). Dance, ten; looks, three: why rubrics matter. Assess. Writing 26, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2015.08.002

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eckes, T., Müller-Karabil, A., and Zimmermann, S. (2016). “Assessing writing” in Handbook of second language assessment. eds. D. Tsagari and J. Banerjee (Boston: De Gruyter Mouton), 147–164.

English, N., Robertson, P., Gillis, S., and Graham, L. (2022). Rubrics and formative assessment in K-12 education: a scoping review of literature. Int. J. Educ. Res. 113:101964. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2022.101964

Flower, L., and Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. Coll. Compos. Commun. 32, 365–387. doi: 10.58680/ccc198115885

Ghaffar, M. A., Khairallah, M., and Salloum, S. (2020). Co-constructed rubrics and assessment for learning: the impact on middle school students’ attitudes and writing skills. Assess. Writing 45:100468. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2020.100468

Gyamfi, G., Hanna, B. E., and Khosravi, H. (2022). The effects of rubrics on evaluative judgement: a randomised controlled experiment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 126–143. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1887081

He, C., Zeng, J., and Chen, J. (2022). Students’ motivation for rubric use in the EFL classroom assessment environment. Front. Psychol. 13:895952. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.895952

Hodgson, V. (2008). “Stimulated recall” in The sage dictionary of qualitative management research. eds. R. Thorpe and R. Holt (London: SAGE).

Howell, R. J. (2011). Exploring the impact of grading rubrics on academic performance: findings from a quasi-experimental, pre–post evaluation. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 22, 31–49.

Imbler, A. C., Clark, S. K., Young, T. A., and Feinauer, E. (2023). Teaching second-grade students to write science expository text: does a holistic or analytic rubric provide more meaningful results? Assess. Writing 55:100676. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2022.100676

Jonsson, A., and Svingby, G. (2007). The use of scoring rubrics: reliability, validity and educational consequences. Educ. Res. Rev. 2, 130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2007.05.002

Koltovskaia, S. (2020). Student engagement with automated written corrective feedback (AWCF) provided by Grammarly: a multiple case study. Assess. Writ. 44, 100450–100412. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2020.100450

Krebs, R., Rothstein, B. R., and Roelle, J. (2022). Rubrics enhance accuracy and reduce cognitive load in self-assessment. Metacogn. Learn. 17, 627–650. doi: 10.1007/s11409-022-09302-1

Li, J., and Lindsey, P. (2015). Understanding variations between student and teacher application of rubrics. Assess. Writing 26, 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2015.07.003

Panadero, E., and Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: a review. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Panadero, E., and Jonsson, A. (2020). A critical review of the arguments against the use of rubrics. Educ. Res. Rev. 30:100329. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100329

Panadero, E., Jonsson, A., Pinedo, L., and Fernández-Castilla, B. (2023). Effects of rubrics on academic performance, self-regulated learning, and self-efficacy: a meta-analytic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 35:113. doi: 10.1007/s10648-023-09823-4

Radwan, A. A. (2005). The effectiveness of explicit attention to form in language learning. System 33, 69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2004.06.007

Ragupathi, K., and Lee, A. (2020). Beyond fairness and consistency in grading: the role of rubrics in higher education. C. S. Sanger and N. W. Gleason (C. S. Sanger and N. W. Gleason Eds.), Diversity and inclusion in global higher education: lessons from across Asia (73–96). Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan.

Reddy, Y. M., and Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 435–448. doi: 10.1080/02602930902862859

Reynolds-Keefer, L. (2010). Rubric-referenced assessment in teacher preparation: an opportunity to learn by using. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 15:8. doi: 10.7275/psk5-mf68

Rezaei, A. R., and Lovorn, M. (2010). Reliability and validity of rubrics for assessment through writing. Assess. Writing 15, 18–39. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2010.01.003

Uludag, P., and McDonough, K. (2022). Validating a rubric for assessing integrated writing in an EAP context. Assess. Writ. 52:100609. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2022.100609

Keywords: analytic rubric, benefits, EFL context, language students, writing model, higher education

Citation: Bin Dahmash NF (2025) The analytic use of rubrics in writing classes by language students in an EFL context: students’ writing model and benefits. Front. Educ. 10:1588046. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1588046

Edited by:

Hamid Ashraf, Islamic Azad University Torbat-e Heydarieh, IranReviewed by:

Frank Quansah, University of Education, Winneba, GhanaNeda Fatehi Rad, Islamic Azad University Kerman, Iran

Copyright © 2025 Bin Dahmash. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nada Fahad Bin Dahmash, bmFsZGFobWFzaEBrc3UuZWR1LnNh

Nada Fahad Bin Dahmash

Nada Fahad Bin Dahmash