- Faculty of Education, Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa

The South African higher education landscape continues to grapple with persistent challenges despite significant policy reforms introduced by the democratic government. Epistemologies and knowledge systems in most universities remain deeply rooted in Western worldviews, limiting the inclusivity and relevance of curricula in addressing the socio-economic needs of a post-colonial workforce. This study employed an interpretive qualitative approach, utilizing narrative analysis to examine data collected from semi-structured interviews with 3 lecturers and 1 curriculum transformation manager at a university in the Eastern Cape region of South Africa. Key findings include the infusion of entrepreneurship education and digital literacy to bridge the skills gap and ensure graduates possess competencies that align with contemporary workforce needs. Incorporating various cultural identities, ideologies, and languages into curricula can create an inclusive learning environment that fosters critical thinking and social justice. This paper recommended that challenging Eurocentric perspectives, promoting multilingualism, and leveraging technology responsibly will decolonise university curricula and prepare graduates for meaningful participation in a dynamic and globalized economy.

1 Introduction

South African universities face a critical challenge in reforming their curricula to align with the demands of a post-colonial workforce while advancing sustainable development. Despite efforts to promote inclusivity and diversity, many institutions continue to perpetuate Eurocentric perspectives, marginalizing Indigenous knowledge systems and reinforcing social inequalities. This disconnect between curricular content and workforce needs limits graduates' preparedness for employment in a rapidly evolving, locally relevant job market. Traditional curricula often overlook African epistemologies, disregarding local socio-economic contexts and prioritizing Western frameworks that fail to equip graduates with the skills and competencies required in South Africa's diverse economic landscape. Universities worldwide are adapting curricula to address historical inequalities and meet the demands of a dynamic workforce. In Africa, curriculum transformation has evolved from colonial missionary education to contemporary digital and knowledge-based economies. However, the dominance of Western epistemologies in South African higher education persists (Blignaut, 2017; Mopeli, 2017), evidenced by the predominance of English in academic discourse, the erasure of African knowledge systems, and the country's ongoing struggle for epistemic independence (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). Decolonizing university curricula and integrating African epistemologies into teaching and learning processes is necessary to foster cognitive justice and equip graduates with skills relevant to local and global labor markets. Since 1994, South Africa's education system has undergone significant reforms (Shava, 2022), yet curriculum transformation remains incomplete. Addressing employability in a post-colonial workforce requires rethinking traditional pedagogies and integrating local and indigenous knowledge systems with modern economic and socio-political concerns. The challenge lies in balancing Africanization with the inclusion of globally competitive skills, ensuring that graduates are both employable and equipped with culturally relevant knowledge. As Ncanywa and Dyantyi (2022) argue, most university courses in South Africa remain rooted in Eurocentric epistemologies, necessitating a thorough analysis of the socio-economic environment before implementing decolonization strategies. Transforming curricula for sustainable employability requires innovative and creative approaches, embedding African ideologies into learning objectives to produce graduates who are adaptable, skilled, and aligned with the needs of the post-colonial workforce (Koopman, 2018; Ncanywa and Dyantyi, 2022).

The selected university, like many others, has observed that literature on educational transformation lacks a comprehensive framework that addresses identity formation and capacity development in relation to employability (Mopeli, 2017; Mendy and Madiope, 2020). Moreover, existing reforms often overlook the importance of aligning curriculum transformation with local labor market demands, leaving graduates ill-prepared for the realities of the post-colonial workforce. The ongoing debate about integrating Western and African epistemologies remains a key issue in shaping employability-focused curriculum reform. Teaching and learning are central to this transformation, as curriculum reform can play a crucial role in equipping students with both global competencies and locally relevant skills. Mendy and Madiope (2020) argue that curriculum reform positively impacts people's lives, making the decolonization and Africanization of university curricula essential for fostering workforce readiness. Msila and Gumbo (2016) further emphasize that incorporating African indigenous epistemologies into the curriculum can enhance student and lecturer confidence by allowing them to engage with knowledge systems rooted in their lived experiences. This is crucial in preparing graduates who are both academically competent and socially and culturally aware, which is a vital asset in the South African job market. However, as Kayira (2015) highlights, curriculum transformation does not necessitate the wholesale rejection of Western and European epistemologies; instead, a practical approach should integrate beneficial aspects from both knowledge systems to strengthen graduate employability. The ability to critically analyze and merge these epistemologies is a key competency that universities must foster to produce well-rounded graduates who can navigate the complexities of the modern workforce. Mendy and Madiope (2020) note that even African philosophies like Ubuntu and humanism have limitations in fully addressing South Africa's socio-economic challenges. Therefore, curriculum reform must not be a superficial inclusion of African values but a strategic fusion of knowledge systems that enhances graduates' adaptability and relevance in diverse work environments.

Decolonizing the curriculum remains a complex and multifaceted process (Pinar, 2012; Heleta, 2016), mainly as it involves reconciling issues such as de-racialization, Africanization, Eurocentrism, and coloniality. These factors influence how higher education institutions conceptualize and implement curriculum reforms. Jansen (2017) argues that reflecting South Africa's diverse socio-economic contexts in higher education curricula requires careful deliberation and clarity. The process has faced criticism, misinterpretation, and resistance (de Oliveira Andreotti et al., 2015), highlighting the need for a nuanced and context-specific approach to reform. Chilisa (2017) and Le Grange (2020) assert that reclaiming indigenous knowledge systems suppressed during the colonial and apartheid eras is fundamental to meaningful decolonization. This aligns with the broader goal of university curriculum reform ensuring that graduates are equipped with the necessary skills, knowledge, and cultural awareness to thrive in South Africa's evolving post-colonial workforce.

Decolonizing the university curriculum involves integrating African knowledge systems, ideologies, and cultural values alongside existing Eurocentric content (Keet, 2014). This transformation emphasizes the inclusion of Afrocentric perspectives, such as Ubuntu, which is deeply embedded in the cultures of Zimbabwe, Malawi, South Africa, Botswana, Tanzania, and Zambia. Scholars argue that African philosophies should be given equal prominence in higher education curricula (Mawere, 2015; Pandey and Moorad, 2003). From a linguistic standpoint, wa Thiong'o (2000) advocates for decolonizing language instruction, emphasizing the importance of teaching in African languages. Mbembe (2016) echoes this sentiment, arguing that African universities should prioritize multilingualism over colonial monolingual structures. UNESCO (2003) supports this approach, asserting that local languages preserve, transmit, and apply indigenous knowledge effectively, ensuring broader student participation in multilingual education.

A successful curriculum transformation requires diverse skills, including an entrepreneurial mindset, which fosters innovation, teamwork, networking, adaptability, and value creation (Ncanywa and Dyantyi, 2022). Those spearheading curriculum reform must develop accessible and pragmatic strategies relevant to societal needs. Research suggests that teamwork enhances efficiency and collective outcomes more than individual efforts (Burke and Hodgins, 2015; Ncanywa and Dyantyi, 2022). Entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in this process by encouraging initiative, proactive problem-solving, and continuous adaptation to evolving educational and economic landscapes (Jardim et al., 2021). Implementing entrepreneurial principles in curriculum reform ensures that graduates develop the critical skills necessary for success in the contemporary workforce, making them more adaptable and employable. Rediscovering and integrating African knowledge is central to decolonizing higher education (Sayed et al., 2016). South African universities still operate within largely Eurocentric curricula, necessitating urgent reform (Mheta et al., 2018). A decolonized curriculum enables academics and students to conceptualize their realities within global knowledge systems, fostering a deeper connection between education and lived experiences.

The necessity for curriculum reform extends beyond decolonization to addressing employability within the post-colonial workforce. Higher education institutions must align curricula with contemporary labor market demands, ensuring that graduates possess the skills required for a dynamic and uncertain job market. Scholars argue that universities should integrate sustainable development principles to prepare students for evolving economic and social challenges (Maringe and Ojo, 2017). Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has gained prominence as a strategic approach to equipping learners with the competencies necessary to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Leicht et al., 2018). Higher education institutions play a vital role in promoting ESD through research, teaching, and governance (Nhamo and Mjimba, 2019).

Furthermore, gender inclusivity is a key aspect of sustainable curriculum reform. The push for gender equity and the empowerment of women aligns with broader objectives of social transformation and workplace diversity (Morris, 2016; Ajani et al., 2019). Student-led movements such as #RhodesMustFall have intensified calls for curriculum decolonization in South Africa, demanding academic structures that reflect African identities and realities (Jansen, 2017; Sayed et al., 2016). Naicker (2016) asserts that decolonizing university curricula will facilitate necessary social changes within institutions. Shay (2016) warns that curricula failing to consider diverse student realities pose a significant risk to the sustainability of higher education. In response to these demands, the Ministry of Higher Education and Training convened a Transformation Summit in 2015 to address student concerns (Davids, 2016). However, the summit failed to provide adequate solutions, escalating tensions and resulting in protests, institutional damage, and student arrests (Badat, 2016). These events underscore the urgent need for universities to commit to meaningful curriculum transformation. This study explores strategies for curriculum reform in one South African university, focusing on aligning academic programs with employability needs, decolonization principles, and sustainable development. The objective is to create a curriculum that not only reflects African epistemologies but also equips graduates with relevant skills for the evolving global workforce, ensuring long-term economic and social resilience.

1.1 Theoretical literature

The study draws upon the decolonial theory, which is deeply informed by the everyday practices of Indigenous people, who engage in ongoing resistance and cultural continuance for self-determination, sovereignty, and healing from colonial impact (Mukavetz, 2018). The decolonial framework aims to create, sustain, and maintain a habitable space for present and future generations' independence (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). In the context of South Africa, where the legacy of colonialism and apartheid continues to influence societal structures and educational systems, decolonial theory offers critical insights. Like Indigenous peoples globally, South Africa's Indigenous populations, including the Khoisan peoples, have experienced marginalization and erasure under colonial independence rule (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015). The decolonial theory emphasizes recognizing and valuing Indigenous knowledge and practices, often essential for sustainable development strategies rooted in local contexts.

Decolonial theory interrogates the pervasive influence of colonialism on societal structures and educational systems. In South Africa, for instance, the enduring impact of colonialism and apartheid has not only marginalized Indigenous populations such as the Khoisan but has also embedded Western-centric epistemologies into academic curricula (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015). By applying decolonial theory, the study can critically assess which knowledge systems have been privileged and which have been sidelined, thereby creating an opportunity to reframe curricula in a way that privileges local knowledge, diverse epistemologies, and the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples.

The decolonial framework is deeply rooted in the everyday practices of Indigenous communities, such as resistance, cultural continuance, and self-determination (Mukavetz, 2018). In the context of curriculum reform, this perspective encourages the integration of Indigenous knowledge and methodologies into academic programs. Such integration can empower students by connecting theoretical learning with the realities and values of their cultural contexts, ultimately fostering graduates who are technically proficient and critically aware of the socio-cultural dynamics that impact their professional environments.

A core tenet of decolonial theory is the creation and maintenance of a “habitable space” for current and future generations, ensuring their independence and self-determination (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). This focus is particularly relevant to employability in a post-colonial workforce. Curriculum reforms informed by decolonial insights can aim to develop job-specific skills and broader competencies such as critical thinking, cultural sensitivity, and an understanding of local socio-economic contexts. This holistic educational approach better prepares graduates to navigate and transform workplaces still influenced by historical inequities and contribute meaningfully to sustainable development (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015).

The decolonial theory is an appropriate and powerful analytical framework for this study, and it urges a re-examination of traditional curricula through the dual lenses of historical context and cultural relevancy. It provides a pathway to deconstruct and ultimately reconstruct educational practices to reflect and serve the needs of a post-colonial workforce more accurately. In doing so, the study challenges the entrenched colonial paradigms within higher education and paves the way for a more inclusive, just, and sustainable future for all graduates. This alignment underscores the potential for university curriculum reform to act as a catalyst for broader societal transformation, one that is mindful of past injustices and committed to empowering a diverse, culturally informed, and resilient workforce.

1.2 Methodological outline

In this section, the study's implementation methods are discussed. This covers the paradigm and design of the study, the data analysis technique, participant selection, research instruments, and ethical considerations were covered.

1.3 Research approach and paradigm

The study employed a qualitative research methodology rooted in the interpretative paradigm and informed by construct theory (Cherry, 2020). This theory posits that individuals form their own worldviews and utilize them to interpret their observations and experiences. The interpretivist paradigm was employed because it emphasizes how individuals give meaning to their surroundings and how their perspective influences how they understand it (Maree, 2019). According to Merriam (2015), the interpretative paradigm aims to comprehend the participants' perspective of the world where they live and work. The study's goal, which is to comprehend and explain the curriculum transformation strategies in one South African university in the Eastern Cape. Interpretivists seek to comprehend the meaning that motivates human behavior. Henning (2004) declares that a qualitative research approach often does not present the potential to control factors, which permits themes that the researcher intends to identify in the study to emerge freely and organically.

1.4 Research design and participants

The study employed a participatory research design. Researchers and people affected by the problem can collaborate to find solutions with the aid of this strategy (Leavy, 2017). All voices can be heard through the dynamic, adaptable, and non-hierarchical participatory research approach (Macaulay et al., 1999). This study has been successfully applied in many fields, such as community development, health, education, and environmental protection (Israel et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2006; Tapp et al., 2013). Participatory research designs have several advantages, including fostering rapport and trust with participants, gathering accurate and timely data, and generating workable solutions that consider community needs. Consequently, this allowed the study participants to assess the problem and its solutions.

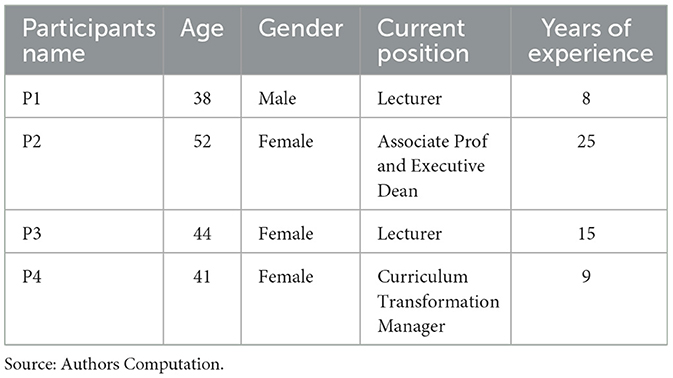

Table 1 presents biographical information about the participants, who range in age from 38 to 52 years. There are three female participants and one male participant. Their professional experience spans from eight to twenty-five years, and their current positions include two lecturers, a curriculum transformation manager, and an executive dean of the faculty. P1, P2, P3 and P4 indicate participant 1 to participant 4.

1.5 Selection of participants

The study used purposive sampling when selecting participants. Purposive sampling provided the author with the flexibility to selectively choose participants who align with the specific criteria and anticipated outcomes of the study, aiming to yield information-rich results (Barkhuizen et al., 2014; Maree and Pietersen, 2007; Merriam, 2015). In terms of inclusion and exclusion criteria, lecturers were included in the study due to their invaluable insights into curriculum transformation, design, and development within the university context. Their direct involvement in teaching and shaping educational content positions them as key stakeholders with firsthand experience and knowledge essential for effective curriculum reform. Stakeholders that are not directly involved in the university curriculum design, development and transformation were excluded in this study. This decision was made based on the focus of the research, which aimed to primarily capture perspectives and expertise related to curriculum design and transformation from those directly involved in teaching and academic content creation.

1.6 Method of data collection

Semi-structured interviews with the participants were used to gather information. It is imperative to apply this methodology because it provides an adaptable and flexible framework that allows participants to express their ideas, opinions, and experiences (Whiting, 2008). The ability of the participants to collaborate with the researcher through this method leads to a deeper understanding of the subject matter from multiple perspectives. One way to guarantee that more complete and accurate data is collected during semi-structured interviews is by using follow-up questions to expand on or clarify the participants' remarks (Adams, 2015). Semi-structured interviews enhance the quality and validity of the data collected, their inclusion in this study is relevant.

1.7 Method of data analysis

A narrative analysis was used to analyse the data. According to Baker (2019), a study technique called narrative analysis is utilized to analyse and comprehend the stories that individuals tell. It is a method of learning about people, civilizations, and society by examining the structures and patterns found in these tales. The author goes on to claiming that a narrative analysis can be used with a wide range of materials, including social media posts, interviews, movies, and written or spoken tales. For this study, the use of a narrative analysis provided a deep understanding of the curriculum transformation strategies for sustainable development in one South African university.

1.8 Ethical considerations

According to McMillan and Schumacher (2014) and Merriam (2015), ethics in research often address morally good or wrong behavior. Ethics in research must be considered when determining the appropriate behaviors of participants. The researcher is prohibited by ethics from failing to maintain study participants' confidentiality and disclosing fraudulent findings (Barkhuizen et al., 2014; Struwig and Stead, 2013). This corresponds to Maree (2016), who contends that the researcher should be aware of ethical responsibilities. These include legal constraints that accompany the gathering and reporting of information in such a way as to protect the rights and welfare of participants involved in the research.

To ensure that the research is trustworthy, the researcher took care to avoid imposing predetermined interpretations on the experiences of the participants. The results were reported and interpreted in accordance with the principles of credulity, transferability, confirmability, and dependability (Kyngäs et al., 2020). The next step in addressing research ethics was to make sure that each participant gave their free and informed consent to participate in the study. They received assurances that their identities would be kept private both before and after the study. Additionally, that once the research is public, nobody will be able to connect their comment to them. Hence the identities were represented as P1, P2 to P4 (Table 1).

2 Discussion of findings

This section presents the discussion of the findings in relation to existing literature:

The study findings revealed that to reform the university curriculum for enhanced employability in a post-colonial workforce, it is crucial to integrate diverse cultural identities and foster an inclusive learning environment. A curriculum that reflects multiple perspectives acknowledges the complexities of the modern labor market, which is shaped by globalization, technological advancements, and socio-economic diversity. By incorporating content that represents various cultural, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds, universities can equip graduates with the critical skills, adaptability, and intercultural competence necessary for thriving in an evolving workforce. This not only enriches the educational experience but also fosters empathy, tolerance, and the ability to navigate diverse professional spaces, ultimately enhancing graduates' employability and contributions to a more equitable and dynamic economy:

L1 “We must ensure that our curriculum reflect diverse perspectives, cultures, and identities. We also need to integrate content that promotes the understanding of empathy and respect for diverse communities, both locally and globally.”

Congruent to the above findings, Keet (2014) declares that African ideas, ideologies, and cultural norms, values, and principles must be taken into consideration in the process of curriculum transition. Incorporating African ideas and ideologies into the curriculum acknowledges African societies' rich cultural heritage and contributions. It allows students to gain experience about diverse cultural perspectives and worldviews, fostering a deeper appreciation for cultural diversity and intercultural understanding. This is later supported by Mheta et al. (2018) by claiming that due to the Eurocentric curricula that South African institutions are using, decolonizing university curriculum is long needed. Addressing the Eurocentric biases inherent in traditional curricula through decolonization efforts is crucial for promoting equity and social justice. Universities challenge colonial legacies and promote cultural empowerment and self-determination by acknowledging and incorporating African ideas, ideologies, and cultural norms into the curriculum. This supports sustainable development by promoting a more equitable and inclusive society where diverse voices are heard and valued. These findings cobborate the standpoint of view rooted in the theory of decoloniality, which focuses on promoting self-determination and sovereignty for Indigenous groups and aims to create educational spaces that affirm their identities, histories, and contemporary contributions to society.

L2 “I see immense potential in this paradigm shift to develop new interdisciplinary programs, like we can infuse entrepreneurship education in our curriculum to foster creativity, collaboration, and partnerships and positive social impact. If we can embrace decoloniality, we an unlock untapped talent and knowledge within our societies driving economic growth and sustainable development.”

The findings suggest a forward-thinking approach that recognizes the transformative potential of integrating entrepreneurship education and decolonial perspectives into the curriculum to address societal challenges and promote sustainable development. The study findings emphasize the importance of incorporating entrepreneurship education in the university curriculum to foster creativity, collaborations, and partnerships. Entrepreneurship education goes beyond teaching business skills, it also encourages critical thinking, problem-solving, and innovation, all of which are essential for addressing societal challenges. These findings are in agreement with the study findings of Ncanywa and Dyantyi (2022) that a curriculum transition requires a variety of talents, including an entrepreneurial approach, which calls for traits and abilities as startup spirit, teamwork, networking, focus, openness to novelty, value creation, and effective communication. Infusing entrepreneurship education in the curriculum, universities can empower future generations to develop innovative solutions that balance economic growth with environmental stewardship and social equity. This aligns with the broader global agenda of achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and creating a more inclusive and resilient society.

CTM “The university should recognize the importance of multilingualism in education, by acknowledging the diverse linguistic landscape in South Africa. It must offer courses and teaching and learning material in local languages to ensure accessibility and inclusivity.”

The study findings revealed that recognizing and embracing multilingualism in education is essential for promoting accessibility, inclusivity, and cultural diversity within South African universities. Offering courses and materials in local languages represents a commitment to equity and social justice, as it ensures that education is accessible to all members of society, regardless of their linguistic background. These findings are in line with the findings of wa Thiong'o (2000), who made a case from a Kenyan viewpoint that decolonizing universities curriculum is necessary to decolonize language instruction. Mbembe (2016) agrees with the above sentiments by stating that a decolonized university in Africa should put African languages at the center of its teaching and learning project. The author further avers that the notion that colonialism is synonymous with monolingualism, while multilingualism characterizes African universities of today and tomorrow, is the source of the cry for African languages to be at the center of instruction. Local languages are the means for preserving, transmitting, and applying traditional knowledge in schools (UNESCO, 2003). All students can participate fully in a bilingual or multilingual education, which provides them with the chance to positively confront local knowledge with knowledge from other sources. This contributes to the sustainability of local cultures and ecosystems by ensuring that traditional knowledge remains accessible and relevant to future generations. Moreover, integrating Indigenous knowledge into education fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation of local environmental management practices, and community resilience strategies. The curriculum should be designed to allow students to share their own narratives and experiences, thereby promoting a more inclusive and culturally diverse educational environment. Embracing multilingualism in education is not only a matter of social justice but also a means of preserving and celebrating diverse linguistic and cultural identities within South Africa.

L4 “It is also important that we infuse technology in our curriculum for sustainable development so that we prepare students for the complex challenges of the 21st century. I want to believe that this will enhance the learning experience, foster innovation, and empower students to become effective agents of positive change in their communities and beyond. We should be careful in doing so, not to erase our local identities and contents in the process.”

The findings suggest a recognition of the potential benefits of integrating technology into education for sustainable development and empowerment, balanced with a commitment to preserving local identities and contexts. This highlights the importance of adopting a culturally responsive approach to educational technology integration that celebrates diversity, promotes inclusivity, and empowers students to engage critically with both global and local issues. This is in line with the university vision and mission that is values-driven, technology-infused African university and providing a gateway for local talent to be globally competitive and to make a sustainable impact and aims to have an influence on South African society in a way that will significantly increase the nation's capacity to pursue faster sustainable development (Songca et al., 2021). Incorporating technology into the university curriculum will equip students with the skills needed to address the complex challenges of the 21st century. This reflects an awareness of the role that technology can play in promoting sustainability and preparing students for the demands of the digital world, future workforce, where digital literacy and technological proficiency are increasingly essential.

3 Conclusion and recommendations

This study highlights the urgent need for university curriculum reform to align higher education with the demands of a post-colonial workforce. To ensure that graduates are adequately prepared for employment in a rapidly evolving and diverse job market, universities must embrace curriculum transformation that integrates Indigenous perspectives, histories, languages, and epistemologies across disciplines. This approach fosters cultural competency, critical thinking, and social responsibility skills essential for a dynamic workforce. A key recommendation is collaborating with local communities and industry stakeholders to ensure the curriculum remains authentic, relevant, and responsive to societal needs. The curriculum should also incorporate diverse voices, perspectives, and sources, reflecting South Africa's rich cultural and intellectual heritage. This includes integrating African scholarship and knowledge systems to challenge Eurocentric paradigms that may not fully address the realities of the local labor market. Furthermore, curriculum reform must prioritize employability by equipping students with practical skills, entrepreneurial competencies, and digital literacy. Universities should leverage technology to enhance accessibility, promote collaboration, and support knowledge-sharing among students and educators. Digital transformation in education should align with principles of data sovereignty, privacy, and equitable access to resources to ensure inclusive learning environments. Multilingualism should also be embraced as a strategic tool for employability, enabling graduates to communicate effectively in diverse workplaces. Encouraging students to share their narratives and experiences can further enrich learning by fostering an inclusive and culturally diverse academic space. By implementing these curriculum transformation strategies, South African universities can bridge the gap between higher education and workforce needs. This will not only contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2063 priorities but also position graduates as adaptable, innovative, and socially responsible professionals. A holistic approach to education, rooted in inclusivity and responsiveness to local and global challenges, is key to preparing students for the complexities of the 21st-century workforce and ensuring sustainable development in South Africa and beyond.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by WSU- Faculty of Education Research Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ND: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, W. C. (2015). “Conducting semi-structured interviews,” in Handbook of practical program evaluation, 4th Edn. Eds. J. Wholey, H. Hatry, and K. Newcomer (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 492–505. doi: 10.1002/9781119171386.ch19

Ajani, J. A., D'Amico, T. A., Bentrem, D. J., Chao, J., Corvera, C., Das, P., et al. (2019). Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 17, 855–883. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0033

Badat, S. (2016). Black student politics: Higher education and apartheid from SASO to SANSCO, 1968-1990. Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315829357

Baker, J. H. (2019). An introduction to English legal history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198812609.001.0001

Barkhuizen, N., Mogwere, P., and Schutte, N. (2014). Talent management, work engagement and service quality orientation of support staff in a higher education institution. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 5, 69–77. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n4p69

Blignaut, S. E. (2017). Teachers' perceptions of the factors affecting the implementation of the national curriculum statement. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 18, 191–199. doi: 10.1080/09751122.2017.1305740

Burke, M., and Hodgins, M. (2015). Is “Dear colleague” enough? Improving response rates in surveys of healthcare professionals. Nurse Res. 23, 8–15. doi: 10.7748/nr.23.1.8.e1339

Chilisa, B. (2017). Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: an African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 12, 813–827. doi: 10.1007/s11625-017-0461-1

Davids, N. (2016). On extending the truncated parameters of transformation in higher education in South Africa into a language of democratic engagement and justice. Transform. High. Educ. 1, 1–7. doi: 10.4102/the.v1i1.7

de Oliveira Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., and Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolon. Indigen. Educ. Soc. 4.

Heleta, S. (2016). Decolonisation of higher education: dismantling epistemic violence and Eurocentrism in South Africa. Transform. High. Educ. 1, 1–8. doi: 10.4102/the.v1i1.9

Henning, H. M. (2004). Solar-assisted air-conditioning in buildings. Appl. Ther. Eng. 27, 1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2006.07.021

Israel, M. H., Binns, W. R., Cummings, A. C., Leske, R. A., Mewaldt, R. A., Stone, E. C., et al. (2005). Isotopic composition of cosmic rays: results from the cosmic ray isotope spectrometer on the ACE spacecraft. Nucl. Phys. A 758, 201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.05.038

Jansen, J. D. (2017). Educate Yourself Widely. The Herald. Available online at: https://www.theherald.co.za/amp/opinion/2017-01-05-jonathan-jansen-educate-yourself-widely

Jardim, M. G. L., Castro, T. S., and Ferreira-Rodrigues, C. F. (2021). Sintomatologia depressiva, estresse e ansiedade em universitários. Psicousf 25, 645–657. doi: 10.1590/1413/82712020250405

Kayira, J. (2015). (Re) creating spaces for uMunthu: postcolonial theory and environmental education in southern Africa. Environ. Educ. Res. 21, 106–128. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2013.860428

Kyngäs, H., Kääriäinen, M., and Elo, S. (2020). “The trustworthiness of content analysis,” In The application of content analysis in nursing science research (New York: Springer) pp. 41–48. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6_5

Le Grange, L. (2020). Decolonising the university curriculum: The what, why and how. In Transnational education and curriculum studies. Milton Park: Routledge (pp. 216–233). doi: 10.4324/9781351061629-14

Leicht, A., Heiss, J., and Byun, W. J. (2018). Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development. Springer.

Lewis, P., Abbeduto, L., Murphy, M., Richmond, E., Giles, N., Bruno, L., Schroeder, S., Anderson, J., and Orsmond, G. (2006). Psychological wellbeing of mothers of youth with fragile X syndrome: syndrome specificity and within-syndrome variability. J. Intel. Disabil. Res. 50, 894–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00907.x

Macaulay, A. C., Commanda, L. E., Freeman, W. L., Gibson, N., McCabe, M. L., Robbins, C. M., and Twohig, P. L. (1999). Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. BMJ 319, 774–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774

Maree, J. G. (2016). Career construction counseling with a mid-career Black man. Career Dev. Quart. 64, 20–34. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12038

Maree, K., and Pietersen, J. (2007). The Quantitative Research Process. In First Steps in Research. Botswana: Van Schaik. (pp. 145–153).

Maree, K. G. (2019). Group Career Construction Counselling With Students From Disadvantaged Communities. In XVI European Congress of Psychology (pp. 230–230a).

Maringe, F., and Ojo, E. (2017). Sustainable Transformation in a Rapidly Globalizing and Decolonising World: African Higher Education on the Brink. In Sustainable Transformation in African Higher Education. Leiden: Brill, (pp. 25–39). doi: 10.1007/978-94-6300-902-7_2

Mawere, M. (2015). Indigenous knowledge and public education in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. Spectr. 50, 57–71. doi: 10.1177/000203971505000203

Mbembe, A. J. (2016). Decolonizing the university: new directions. Arts Human. High. Educ.15, 29–45. doi: 10.1177/1474022215618513

McMillan, J., and Schumacher, S. (2014). Research in education (7th Edn.). London: Pearson Education Limited.

Mendy, J., and Madiope, M. (2020). Curriculum transformation: a case in South Africa. Pers. Educ. 38, 1–9. doi: 10.18820/2519593X/pie.v38.i2.01

Merriam, S. B. (2015). Qualitative research: Designing, implementing, and publishing a study. In Handbook of research on scholarly publishing and research methods (pp. 125–140). New York: IGI Global. doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-7409-7.ch007

Mheta, G., Lungu, B. N., and Govender, T. (2018). Decolonisation of the curriculum: A case study of the Durban University of Technology in South Africa. South Afr. J. Educ. 38. doi: 10.15700/saje.v38n4a1635

Mopeli, N. A. (2017). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Challenges and dilemmas facing senior phase social science teachers in Lejweleputswa district (Doctoral dissertation, Central University of Technology, Free State).

Msila, V., and Gumbo, M. T. (Eds.). (2016). Africanising the curriculum: Indigenous perspectives and theories. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media. doi: 10.18820/9780992236083

Naicker, C. (2016). From Marikana to #feesmustfall: the praxis of popular politics in South Africa. Urbanisation 1, 53–61. doi: 10.1177/2455747116640434

Ncanywa, T., and Dyantyi, N. (2022). The role of entrepreneurship education in higher education institutions. J. Art. Hum. Soc. Sci. 3, 75–89. doi: 10.38159/ehass.2022SP3117

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2018). Epistemic freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and decolonization. Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429492204

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015). Decoloniality as the future of Africa. Hist. Compass 13, 485–496. doi: 10.1111/hic3.12264

Nhamo, G., and Mjimba, V. (2019). Scaling Up SDG Implementation: Emerging Cases From State, Development, and Private Sectors. Springer.

Pandey, S. N., and Moorad, F. R. (2003). The decolonization of curriculum in Botswana. International Handbook of Curriculum Research. Milton Park: Routledge, p.143–170.

Pinar, W. (2012). Curriculum studies in the United States: Present circumstances, intellectual histories. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1057/9780230118065

Sayed, Y., Badroodien, A., Salmon, T., and McDonald, Z. (2016). Social cohesion and initial teacher education in South Africa. Educ. Res. Soc. Change 5, 54–69. doi: 10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i1a4

Shava, H. (2022). Linear predictors of perceived graduate employability among South Africa's rural universities' learners during the Covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 21, 106–126. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.21.3.7

Shay, S. (2016). Curricula at the boundaries. High. Educ. 71, 767–779. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9917-3

Songca, R. N., Ndebele, C., and Mbodila, M. (2021). Mitigating the implications of covid-19 on the academic project at Walter Sisulu University in South Africa: a proposed framework for emergency remote teaching and learning. J. Student Affairs Afr. 9, 41–60. doi: 10.24085/jsaa.v9i1.1427

Struwig, F. W., and Stead, G. B. (2013). Research: Planning, Designing and Reporting, 2nd Edn. Cape Town: Pearson.

Tapp, H., White, L., Steuerwald, M., and Dulin, M. (2013). Use of community-based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. J. Comp. Effect. Res. 2, 405–419. doi: 10.2217/cer.13.45

wa Thiong'o, N. (2000). “The language of African literature (1986),” in The Routledge Language and Cultural Theory Reader, Eds. L. Burke, T. Crowley, and A. Girvin (Milton Park: Routledge), p. 434–455.

Keywords: curriculum, employability, colonial, workforce, education, university

Citation: Dyantyi N (2025) University curriculum reform and employability: addressing the needs of the post-colonial workforce. Front. Educ. 10:1591654. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1591654

Received: 11 March 2025; Accepted: 20 May 2025;

Published: 03 November 2025.

Edited by:

Matthew Barr, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Milena Dragicevic Sesic, University of Arts in Belgrade, SerbiaMiloš Krstić, University of Nis, Serbia

Copyright © 2025 Dyantyi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ntsika Dyantyi, bnRkeWFudHlpQHdzdS5hYy56YQ==

Ntsika Dyantyi

Ntsika Dyantyi