- 1Department of Education and Community, Kinneret Academic College, Tzemach, Israel

- 2Department of Psychology, Kinneret Academic College, Tzemach, Israel

Introduction: Positive education is increasingly applied to foster the wellbeing of students and professional staff in schools, but its application in Non-Formal Education (NFE) remains underexplored. Given its flexible, value-driven and social nature, NFE frameworks could offer a particularly suitable setting for such application.

Methods: The study examined the experiences of 21 NFE teachers who participated in a nine-session positive education training program, aiming to identify whether and how the training contributed to their wellbeing and to the integration of positive education within their respective NFE frameworks. Qualitative data was collected from multiple sources, including interviews, reflection logs, WhatsApp correspondence and future work plans, and analyzed using inductive thematic analysis approach.

Results: The program was found to produce a multidimensional increase in teachers’ wellbeing, enhancing positivity, self-awareness, self-compassion, self-efficacy, and a sense of professional meaning. It further motivated participants to integrate positive education elements into their teaching goals and to flexibly adapt such elements into their own NFE routines. Despite noted challenges, participants viewed NFE as a highly suitable setting for cultivating positive education, and suggested ways of adapting it for better integration.

Discussion: It is concluded that the integration of positive education into NFE teacher training programs could further its application, enhancing wellbeing among teachers and students. It is recommended that future training programs should focus on context-specific NFE practices which can be adapted and applied flexibly.

Introduction

In recent years, and especially since the onset of COVID-19 (Ma et al., 2021), the mental health and wellbeing of students have become top strategic priorities in schools worldwide (Tyton Partners, 2021; Kern and Wehmeyer, 2021). Consequently, there has been a growing interest in integrating positive education into school systems (Ryu et al., 2022; Slemp et al., 2017).

Positive psychology, the theoretical underpinning of positive education, emphasizes the positive aspects of human experience (Seligman, 2002). It focuses on wellbeing and human flourishing, characterized by positive affective states and psychological health (Seligman, 2011), with wellbeing viewed as a multifaceted construct comprising hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions (Kern and Wehmeyer, 2021). Positive psychology emerged in the late 1990s, against the backdrop of mainstream psychology’s focus on pathologies and human weaknesses (Seligman, 2002). The field grew significantly, exploring positive and adaptive factors that enhance wellbeing, such as gratitude, strengths, resilience, creativity, authenticity, self-efficacy, and mindfulness (Compton and Hoffman, 2019; Oades and Mossman, 2017; Rusk and Waters, 2013). In his well-known PERMA model, Seligman (2011) suggested five main elements that promote wellbeing: Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. Several studies have found links between PERMA dimensions and other positive psychology factors, and subjective, physical, psychological, and social wellbeing (e.g., Donaldson and Donaldson, 2020; Feng et al., 2020; Gander et al., 2016). Consequently, positive psychology interventions designed to cultivate positive emotions, behaviors, and cognitions have emerged (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009). Well-designed interventions were shown to improve different wellbeing dimensions and decreased distress and depression in clinical and organizational settings and in the general population (Carr et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Meyers et al., 2013).

Although generally well-received, positive psychology has faced critique over the course of its development as a research field. A primary concern involved its emphasis on positive emotional states, prompting calls for greater recognition of the functional value of both positive and negative emotional experiences in promoting psychological wellbeing (Ryff, 2022; Cabanas and Illouz, 2019; Pauwels, 2015). In response, the emergence of Positive Psychology 2.0 has sought to address this limitation by integrating the complex interplay between positive and negative experiences to support more nuanced and realistic understandings of human flourishing (Lomas and Ivtzan, 2016; Fernández-Ríos and Vilariño, 2016). Further critiques highlight the field’s predominantly individualistic orientation, which tends to overlook relational dimensions of wellbeing and the influence of broader socio-cultural and structural factors (Ryff, 2022; McLellan et al., 2022). Scholars have also raised concerns about the potential for positive psychology to shift focus away from systemic issues—such as the quality and accessibility of social welfare—toward individual emotion regulation and personal responsibility over wellbeing (White, 2017). In light of these critiques, it is essential that comprehensive intervention programs address the full spectrum of emotional experience while also incorporating contextual, relational, and societal dimensions of wellbeing.

As schools strive to foster wellbeing in students as part of their educational goals (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015; Kern and Wehmeyer, 2021), positive education (Seligman et al., 2009) has been gaining traction within formal educational settings (Adler, 2016; White, 2021; Noble and McGrath, 2016). At the same time, various studies have shed light on ways in which positive psychology can be adapted to educational settings so that it contributes to students’ overall wellbeing and academic success (Kern and Wehmeyer, 2021; Seligman et al., 2009). Non-Formal Education (NFE) is being increasingly acknowledged for its contribution to children and youth (Council of Europe, 2024; Gross and Goldratt, 2017) and has been suggested as a suitable setting for the promotion of emotional and social capabilities (Grajcevci and Shala, 2016) and positive education (Noble and McGrath, 2016). However, positive education efforts in NFE settings are rare and under-explored. Research focusing on NFE teachers is particularly scarce, despite the noted impact of teachers’ wellbeing on their students (Paterson and Grantham, 2016), and the recognized role of teachers in cultivating positivity and social and emotional competencies in children (Chodkiewicz and Boyle, 2017; Norrish et al., 2013). The current study aims to fill this gap by studying the experiences of NFE teachers during and following a comprehensive positive education training program aimed at enhancing their own wellbeing and that of their students. This study was conducted in the north of Israel, where NFE takes shape of an all-week afterschool program for children and youth combining enrichment, leisure and social activities with meals and homework.

Positive education

Positive education combines the scholarship of positive psychology with best educational practices (Slemp et al., 2017) to enhance the psychological and emotional wellbeing of students alongside their academic achievements (Kern and Wehmeyer, 2021). As such, it aims to cultivate competencies that encourage positive emotions, behaviors, and relationships, increase resilience and growth, and create a positive self-view (Cefai and Cavioni, 2015; Chodkiewicz and Boyle, 2017; Norrish et al., 2013), which lead to holistic and flourishing educational environments that support these competencies by means of transformative processes (Seligman et al., 2009). These objectives have been deemed especially important in the current turbulent, complex, and ambiguous reality of the 21st century and its technological, occupational, and societal challenges (Dolev and Itzkovich, 2020; Tyton Partners, 2021) as well as the increasing rates of depression, loneliness, mental health concerns, and suicide intentions in children and youth (Shorey et al., 2022; Sachs et al., 2019). Furthermore, recent studies have associated student wellbeing with multiple positive school outcomes, such as better engagement, higher academic achievements, and fewer behavior problems (McNeven et al., 2024). In line with the varied dimensions of positive psychology, positive education encompasses a range of frameworks and approaches that focus on elements such as character strengths (Lavy, 2020), gratitude (Froh et al., 2008), optimism, hope, mindfulness (Campion and Rocco, 2009), meaning, purpose (Wong, 2010), engagement and interpersonal relationships (Norrish et al., 2013). The PERMA model (Seligman, 2011, see above) has been widely employed as a foundational framework for positive psychology interventions. These interventions are frequently integrated with components of social–emotional learning (SEL), such as emotional awareness and regulation (Slemp et al., 2017). SEL encompasses the development of social and emotional knowledge, skills, attitudes, mindsets, and behaviors that support success across diverse domains of life, particularly within educational settings (OECD, 2018; Osher et al., 2016). The capacity to recognize and manage a full range of emotions is increasingly viewed as a critical foundation for fostering wellbeing (Denston et al., 2022; Green et al., 2021), aligning with the principles of Positive Psychology 2.0, which emphasizes the integration of both positive and negative emotional states (Lomas and Ivtzan, 2016). It has emerged as a well-established and widely adopted approach for promoting social–emotional competence, wellbeing, mental health, and resilience—primarily within the context of formal education (Green et al., 2021). Waters and Loton (2019) suggested the SEARCH meta-framework for positive education, which integrates SEL components and includes six pathways to wellbeing: Strengths; Emotional management; Attention and awareness; Relationships; Coping; and Habits and goals.

Ample studies have demonstrated the benefits of school-based positive education programs on students’ wellbeing and mental health (e.g., Froh et al., 2008; Platt et al., 2020; Yeh and Barrington, 2023; Wessels and Wood, 2019), academic outcomes, and school climate (Shankland and Rosset, 2017), including long-term effects (Shoshani et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2011). For example, a positive story-based program enhanced presence-in-the-moment and optimism and decreased depression and anxiety among Turkish high-school students (Arslan et al., 2022). Mindfulness-based programs enhance calmness and emotion management and decrease negative emotions in students (Roeser et al., 2022; Sapthiang et al., 2019). Positive education training programs may introduce positive education implicitly, weaving relevant topics into pre-existing academic materials or daily conversations, or explicitly, using a variety of tools to introduce positive education elements via designated lessons, positive behavioral interventions, or as part of holistic school programs (Slemp et al., 2017; Norrish et al., 2013). However, wellbeing training programs can appear disconnected from the academic demands placed on teachers, potentially leading to a role conflict between providing emotional support and delivering academic content. Therefore, emotional wellbeing should be considered a priority in educational policy (Wilson et al., 2023).

Non-formal education as an opportunity for positive education

The principles of positive education appear to resonate with the ethos of NFE, a term that refers to all organized educational activities taking place outside formal education systems (La Belle, 1982). NFE can be understood as either an alternative to or a complement of formal education, playing a significant role in the lifelong learning processes of children, youth, and adults (Almida and Morais, 2025). As such, it includes extra-curricular activities both in and outside of school and encompasses diverse frameworks such as youth movements, after-school programs, leisure activities, and community organizations (Romi and Schmida, 2009).

International literature highlights NFE as a critical mechanism for supporting populations with limited access to formal schooling—particularly in developing countries, at-risk societies, and among marginalized groups (Almida and Morais, 2025). This includes initiatives targeting street children and youth (Shephard, 2014), efforts to enhance access to and quality of schooling (Hoppers, 2006), and programs aimed at fostering lifelong learning for skill development, career advancement, and personal growth in both developing and developed contexts (Almida and Morais, 2025; Vaculíková et al., 2024).

In the Israeli context, NFE is implemented through a range of frameworks, including youth movements and community center-based activities. A distinctive manifestation of NFE in Israel is the social-educational system for children and youth, particularly prevalent in rural kibbutz and moshav communities. In these settings, the community assumes collective responsibility for the upbringing of its children (Dror, 2002) and schools and kindergartens operate in close partnership with the non-formal social-educational system. The social-educational system functions as a central agent in the socialization of children and in the ongoing development of the community (Shadmi-Wortman, 2017).

Callanan et al. (2011) described five main dimensions of NFE: (a) Non-didactive and not highly academic; (b) Encourages social cooperation; (c) Offers and is embedded in meaningful activities; (d) Initiated by learners’ needs, interests or choices; (e) Removed from external evaluation. As such, NFE learning is organized and guided, yet flexible and varied in its curriculum and methodologies (Grajcevci and Shala, 2016; Johnson and Majewska, 2022), adjusted to students’ needs and interests, often using experiential and game-based learning (Allison and Seaman, 2017). NFE is typically student-focused and inclusive, aimed at creating emotional experiences that can be connected to cognitive contents (Kahane, 1997), and geared toward relationships and community involvement (Allison and Seaman, 2017). In line with 21st-century competencies (González-Pérez and Ramírez-Montoya, 2022), NFE focuses on cultivating personal and social competencies, introspection, self-expression and self-actualization, promoting values and attitudes, and enabling children to better know themselves, others and the world (Grajcevci and Shala, 2016; Romi and Schmida, 2009; Gross and Goldratt, 2017). Indeed, NFE is an important contributor to the constructive use of free time, personal development, and risk prevention (Weissblai, 2012), especially among youth (Bartko and Eccles, 2003). In line with these findings, NFE has been proposed as a conducive setting for the integration of positive education (Noble and McGrath, 2016), offering opportunities to address social dimensions of wellbeing alongside the traditionally individual-focused orientation of positive psychology (White, 2017).

However, despite growing interest in NFE as an important complement to formal schooling (Reichel, 2009), NFE has not received sufficient attention as a framework for positive education.

Positive education training programs for NFE teachers

Teachers play a major role in the social and emotional development and wellbeing of children and youth (McClelland et al., 2017; Schonert-Reichl, 2017). Accordingly, teachers’ wellbeing has intertwined benefits, contributing to their own professional and personal welfare, and students’ wellbeing and outcomes (Wessels and Wood, 2019). Improved wellbeing is associated with teachers’ work commitment and effectiveness (Ainly and Carstens, 2018), interactions with students, positive classroom atmosphere (Palomera et al., 2008), and ability to foster academic achievements (Paterson and Grantham, 2016). Furthermore, wellbeing broadens teachers’ minds (Fredrickson, 2013), allowing them to be more creative and energetic (Mercer and Gregersen, 2020), and helps them cope with stress and burnout, a growing problem in an increasingly demanding, challenging, and complex work reality (Yeh and Barrington, 2023). In doing so, improved wellbeing allows teachers to balance their resources to overcome challenges (Wessels and Wood, 2019) and increases retention (Grant et al., 2019).

In line with the direct link between the wellbeing of teachers and students, integrating positive education into teacher training programs has been deemed important by many scholars (e.g., Chodkiewicz and Boyle, 2017). For example, Norrish et al. (2013) and Lavy (2020) suggested that the development of teachers’ wellbeing could support their efforts to develop the wellbeing of their students by authentically presenting and positively modeling wellbeing-related skills. Furthermore, positive education training for teachers can contribute to the effective and sustainable integration of positive education programs for students in schools (Lavy, 2020; Shankland and Rosset, 2017) by enhancing teachers’ engagement, enthusiasm, and empathy during the integration process (Chodkiewicz and Boyle, 2017; Shoshani and Steinmetz, 2014). Although positive education training programs tend to focus mainly on students, some studies have shown the benefits of teacher training (e.g., Hwang et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2016). Yeh and Barrington (2023), for example, found that positive education training enhanced three aspects of teachers’ wellbeing: emotional (reducing stress and enhancing pleasure); social (improving relationships); and professional (improving teacher-student interactions). In a case study of six teachers, engagement in a positive education process improved their experiences of wellbeing and their ability to sustain these benefits (Wessels and Wood, 2019). Turner and Theilking (2019) found that the conscious employment of PERMA positive psychology strategies by teachers improved both teaching practices and students’ learning. NFE teachers play an especially important role in students’ lives, being able to form flexible, friendly, holistic, and informal interactions with children and youth (Johnson and Majewska, 2022) and gear students’ efforts toward cultivating skills and attitudes (Simac et al., 2021). Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that positive interactions between NFE teachers and their students contribute to the students’ positive development (Jones and Deutsch, 2011). However, these contributions have not been sufficiently recognized (Reichel, 2009). Consequently, efforts to provide NFE teachers with training to enhance their wellbeing and cultivate wellbeing or social–emotional competencies in their students, as well as evidence of such efforts, are scarce.

Thus, this study investigated NFE teachers’ experiences of a positive education program aimed at enhancing their wellbeing and that of their students, as well as their views of NFE as a potential arena for positive education following the training. The main research questions therefore are:

1. What are NFE teachers’ main personal and professional experiences of the positive education training?

2. What is the perceived suitability of positive education related to NFE?

3. Whether and how did NFE teachers intend to apply positive education in their nonformal systems?

Method

The experiences of NFE teachers during a positive education training program were recorded and analyzed using qualitative tools to capture the richness of these experiences and allow for a deep and multifaceted analysis of the findings.

Participants

Participants included 21 NFE teachers who volunteered to participate in the training program.

In the Jordan Valley Regional Council, the site of this study, like in most rural parts of the country, the social-educational system serves students from grades 1 through 12, organized into age-based cohorts. The program is managed by a permanent team of educators, with support provided by older local youth during school vacations for younger children (grades 1–6). Adolescents participate in activities at a dedicated youth club, which operates during regular hours. Programming is offered after school throughout the year daily, combining free and structured activities, with increased activity during holiday periods.

Participant teachers were all female, aged 22–60 years (M = 43.17, SD = 9.90), in line with their representation in NFE in this specific setting and in Israel, and more widely in Israeli education systems, with 1–15 years of teaching experience. Highest education levels were high school (38.1%), BA (34.92%), and MA (11.1%).

Participant recruitment for the program was conducted through an open invitation extended to all non-formal education (NFE) teachers in the northern rural district. The sole incentive offered was the opportunity to participate in the program itself. Interest in the program was notably high, leading to the creation of a waiting list. Participant engagement was equally strong, with all enrolled individuals attending every session in its entirety.

Positive education training program

The program was designed and delivered by three positive psychology experts (the two authors and a mindfulness expert). The course was a novel course developed by the researchers based on the SEARCH pathways to wellbeing meta-framework, noted to foster wellbeing in education systems (see Waters and Loton, 2019 for more details).

The program included nine sessions, each lasting 3.5 h, with two-week intervals between consecutive sessions. Sessions were divided equally among the three mentors (three non-consecutive sessions per mentor).

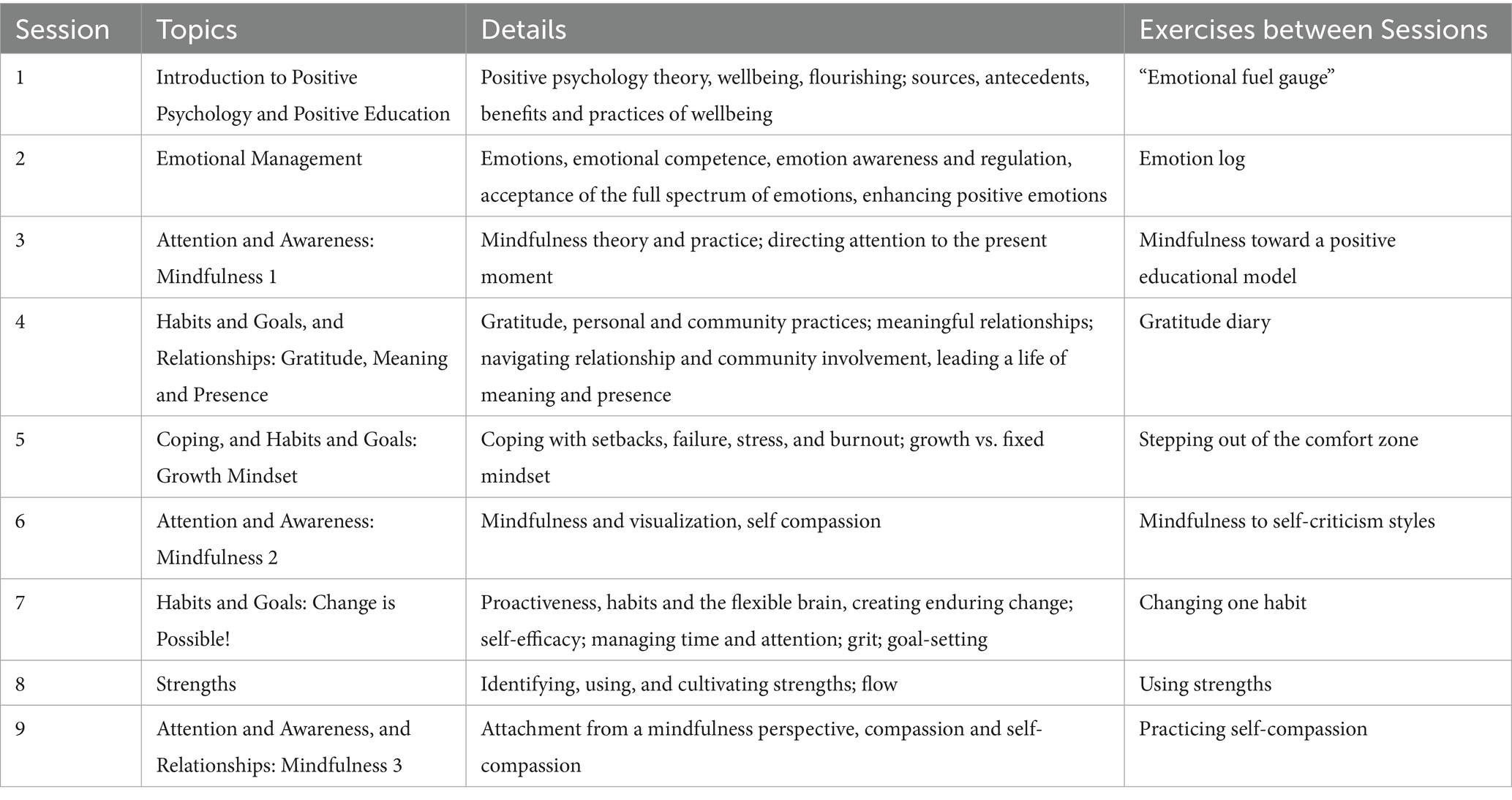

The program aimed to enhance teachers’ wellbeing as well as their motivation and ability to enhance wellbeing in students. Following a discussion of positive psychology, positive emotions and positive education, training sessions and assignments focused on the six SEARCH pathways, namely strengths, emotional management, attention and awareness (with a relatively large segment dedicated to mindfulness), relationships, coping, and habits and goals (including gratitude and growth mindset), and on the links among them (see Table 1).

Participants were provided with basic knowledge of each concept and opportunities to better understand them through related self-exploration and self-development, along with strategies and tools for further development and positive education implementation. Following each training session, participants were given a corresponding personal development assignment which they had to complete before the following session. Online support was available for those who needed it. Sample exercises included keeping an emotion log or a gratitude diary, using strengths, practicing self-compassion, stepping out of one’s comfort zone, and changing a habit. At the end of the training, participants prepared an action plan detailing ways they would integrate principles of positive education into their respective frameworks.

Data collection

Empirical data were gathered from multiple sources to allow for triangulation and enhance the rigor and trustworthiness of the study (Hwang et al., 2017). Each data source provided a unique perspective:

a. In-depth semi-structured interviews held 6 weeks after the end of the training program allowed a deep exploration of participants’ experiences and learning processes during the training program and the sustainability of these processes;

b. Personal reflections submitted at the end of the training captured participants’ fresh and self-directed impressions of the training;

c. WhatsApp group correspondence recorded during and after the training offered a real-time view of themes and experiences that participants chose to share and react to (participants used this group to share information and experiences related to the program and had been notified ahead of time that this correspondence would be used by the researchers for study purposes);

d. Positive education integration plans for respective NFE frameworks (prepared and submitted within 6 weeks after the end of the training) revealed elements of the training that participants viewed as most important and feasible and potential ways to implement them.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis in line with Cronin et al. (2008). Analysis of each data source and their subsequent integration followed four steps: (a) Each dataset was analyzed separately, using an analytic method most appropriate for that data and emergent findings were noted; (b) Findings evident in several datasets were identified, based on relationships with the overarching research questions or resonance between datasets, thus creating a “thread;” (c) Emergent categories, themes and codes concerning the thread were gathered from each dataset to refine the relationships between the thread and the overarching research questions; (d) Findings generated by each thread were synthesized.

All data sources were thematically analyzed by two researchers (the two authors) in a multi-stage process (Bryman, 2016; Weber, 1990). First, each researcher read, analyzed, and coded each dataset independently, generating categories and themes. Themes from different data sources were reviewed by the researcher, creating themes and categories across datasets. The two researchers then met to compare identified themes and categories (90% agreement was noted). Lastly, themes were jointly refined to reach full agreement, as presented in the results section. Given the researchers’ role as facilitators in the training program, their position and involvement within the study and its potential impact were reflected upon, and great care was taken to maintain neutrality during data analysis. Steps included the employment of external interviewers (MA psychology students) and the assignment of an external project coordinator during the facilitating exercises and reflections stages. During the interview, participants were asked to address difficulties and challenges experienced during the training, enabling them to critique potential preliminary assumptions held by the researchers. In addition, the research team engaged in regular reflective discussions to critically examine emerging themes and interpretations in light of the researcher’s positionality.

In line with Hill et al. (2005), categories or themes referred to by more than 50% of participants (in our case, 11 or more participants) were denoted “typical” themes and addressed as “most.” Categories referred to by more than 25% and up to 50% of participants (between 6 and 10 participants) were denoted as “some.” Low-frequency topics thought to add meaningful information were denoted as “few.”

Ethics

Participation in the study was voluntary. Consent forms for the use of all data sources were signed by all participants prior to the beginning of the training program. Participants were assured in advance that all data collected during the study would remain confidential. Personal and identifying details were removed from all research documents to preserve anonymity during the analysis and reporting stages. All personal data was stored safely in the researchers ‘computers using coded identifiers with access restricted exclusively to the research team. Files were deleted upon completion of the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee (ETHICS/28/2022) of the researchers’ institution (Kinneret Academic College-) and the head of the NFE training center. Participants who shared psychological difficulties, or challenges with their groups were offered support from the researchers and were also advised to approach their supervisors.

Results

Analysis of the data revealed three main categories: (a) perceived impact of the training program, (b) perceived suitability of NFE to the application of positive education, and (c) ways to integrate positive education into NFE.

Perceived impact of the training program

Participants noted a variety of impacts from the training program. The two intertwined themes were personal impact and professional impact.

Personal impact

The most prominent impact was the enhancement of personal wellbeing and the provision of tools to sustain it. Enhanced wellbeing was experienced as integral to personal development and as a remedy for fatigue, stress, and burnout, all of which had been experienced by some participants and cited as a motivation to join the training:

[I joined the training] for my own benefit…I wanted to improve as a mother and as a person, to feel better about myself, and to find ways to sustain this feeling. The training enabled me to fulfill many of these goals. (RB, interview)

Enhancement of wellbeing was found to be derived from a number of interrelated processes. Most participants described an enhanced ability to experience positive emotions by focusing on the positives in their own lives, becoming more mindful and more appreciative of positive things around them, and proactively engaging in enhancing positive emotions. One example was the enhancement of gratitude using the gratitude log exercise:

The training helped me focus on the good things in me and around me, rather than on what I don’t have or on what I need to improve. I learned to count my blessings, and I keep reminding myself to do so. (RA, interview)

I first started practicing gratitude during the training. I began by paying attention to and being grateful for the “big things,” and then I moved on to reflect on smaller, more specific things. It was hard, but it made me realize that joy can also be found in the little things in life. (MV, reflection)

While acquiring tools to enhance positive emotions, participants described a process developing emotional self-awareness. They increasingly recognized a wide variety of emotions in themselves and in others through a granulated understanding of emotions and of underlying thoughts and behaviors, and increasing acceptance of negative emotions. These competencies were credited with helping participants to better manage their emotions and stress while also impacting others, mainly their students:

[During the training] I realized that in order to feel successful, I had been trying to squeeze too much into each day, and that these efforts put an enormous pressure on me and on my students. I had been working on changing this pattern and on ridding myself of all the negative emotions and thoughts that were associated with it. In turn, these changes reduced my stress levels and positively impacted the students. (SH, interview)

Another prominent impact on personal wellbeing was enhanced self-compassion. Prior to the training, some participants experienced professional and personal self-criticism, which they attributed, at least in part, to low professional regard for NFE. Enhanced self-compassion found expression in increased levels of self-acceptance, including acceptance of perceived personal weaknesses, past mistakes and current circumstances, and by adopting a growth mindset:

I learned that I am my own sanctuary. That I’m allowed to cry, and to be happy, and that I’m worthy. I discovered ways to accept myself and to appreciate the person I have grown to be over the years, and I‘m also better at accepting others. (TO, interview)

Participants began to overcome their tendency to prioritize the needs of others over their own and to engage in self-care activities such as physical exercise, leisure activities, or spending time with spouses or friends. Self-care activities contributed to the availability of participants to others. Participants also noted enhanced self-confidence , allowing them to recognize their strengths, take actions and risks, step out of their comfort zone, and pursue personal goals. Descriptions of such initiatives included tracking on a snowy mountain, crossing a high-hanging bridge, getting a tattoo, going for a long-delayed job interview, and engaging in a difficult conversation that had been previously avoided. Such pursuits had an impact on overall confidence:

Talking about things which I had never done or even imagined doing before the training, I share with you that I trekked Mt Hermon and walked 13 kilometers in the snow, which I have never imagined I would do, demonstrating both courage and stamina. (RBS, WhatsApp)

The intensities and domains of noted impacts varied across participants. This variation reflected differences in respective starting points. Some participants described a process of reinforcing existing personal attributes related to specific domains, such as gratitude, rather than developing new ones. Two participants who felt burnt out and had joined the training program to relax and recharge, did not engage in deep personal development. Although they developed in some ways (e.g., enhancing positive emotions), changes were less significant. Furthermore, most participants, regardless of starting point, noted that positive development is a process and expressed a wish to continue developing.

Professional impact

Most participants joined the training program to integrate positive education into their respective NFE frameworks. Indeed, the program had an impact on participants’ work experiences and on their motivation and ability to introduce positive education to their students. Personal development was seen as a crucial first step to this professional change by experiencing positive education firsthand:

In order to introduce positive education to children and to do so with conviction and authenticity, teachers first have to go through a learning process themselves. They have to learn to look at the good and to talk about difficulties. Only then can they show their students how to overcome difficulties and how to be positive. (YE, reflection)

Participants referred to specific professional impacts of the program. First, they noted enhanced interpersonal relational wellbeing . They reported an improved ability to communicate with students, such as listening to and being patient with children under their care, empowering them, adopting a strengths-based perspective and helping them regulate their emotions. This, in turn, improved teacher-student relationships and contributed to students’ and teachers’ positive feelings. This impact was particularly evident with students considered to be more challenging. Several participants also noted improved communications with team members and/or parents:

When it came to children that previously had been considered challenging, our communications improved immensely, and the connection between us strengthened. I became more patient, I understood their needs better, and they became my favorite students. (NS, interview)

The training also helped me to work better with my coworkers. I was able to recognize my own feelings and the feelings of other team members in different situations. The same was true when it came to parents of students. (MV, interview)

Although most participants were familiar with positive psychology and cited their wish to learn about positive education as a reason for joining the training, they had not previously considered incorporating positive education principles into their NFE frameworks. During training, however, they became aware of the importance of children’s wellbeing, especially in these “current stressful yet privileged times” (ZL, interview), and the important role educators play in raising resilient, confident, and considerate children. Accordingly, many participants noted that they adopted the integration of positive education into their respective NFE frameworks as an educational goal:

I want to teach children that they are responsible for themselves. Teach them to take time to breathe, to be present, to appreciate what they have, so that they are happier and more resilient, and can lead more peaceful and positive lives. It has become my mission. (RH, reflection)

Children today are experiencing emotional overloads and anxiety. I realized we can use positive psychology and mindfulness to help them cope with these challenges and I intend to focus on it. (OL, interview)

The increased awareness and adoption of positive education led to an enhanced sense of professional meaning and purpose among participants and increased their professional wellbeing . Participants noted increased energy levels and work engagement and reduced feelings of burnout and/or meaninglessness. Such feelings had previously been associated with a pre-training focus on daily routines and with misconceptions about NFE (e.g., equating it to babysitting):

Introducing positive education to the students gives me a sense of meaning, because I have come to realize that I can provide them with an important basis to build their identities on, and that’s the best thing I can do for them. (OB, reflection)

Most participants noted that they acquired positive education tools and routines that supported their motivation to promote positive education:

I have been working in the field of education for many years, and I’ve been personally familiar with the language of positive psychology…but the new tools that we had acquired during the training motivated me to introduce positive education to my students and helped me feel confident in doing so. (RBS, reflection)

Several participants referred to specific tools they were familiar with (e.g., meditation or gratitude) but noted the lack of a formal framework for using these tools as well as a wide variety of tools. Most referred to new tools acquired during training, some of which they started using during the program:

As part of the training, I acquired many new tools and ideas, such as turning already familiar games into strengths-based games, going outdoors in order to practice mindfulness, or talking about emotions, and practicing gratitude with children. (NS, reflection)

In an example shared on the WhatsApp group, in which tools were shared regularly, after the beginning of the war in Israel participants used and adjusted tools acquired during training to support their own resilience and that of their students.

There were three ways positive education was integrated into NFE frameworks: (a) employing tools and practices acquired during training without modifying them; (b) adapting tools to match students’ ages and needs; and (c) designing new tools for this integration. Notably, two participants found it difficult to adapt the tools to their daily routines and were reluctant to do so. They cited the cynicism and lack of emotional training of their adolescent students as a reason for these difficulties.

Some participants shared instances of involvement in positive psychology-inspired community projects, highlighting ripple-effects from the training program. Examples include the establishment of weekly mindfulness sessions for seniors, nature-based mindfulness sessions, positive psychology training for early childhood educators, and a resilience-focused training workshop for NFE staff.

Perceived suitability of NFE to the application of positive education

Alongside personal and professional experiences, participants also noted issues related to the suitability of NFE for the application of positive education, discussing both benefits and challenges.

Benefits from the integration of positive education into NFE frameworks

Most participants viewed NFE as a fitting framework for positive education, even more so than formal education. They noted an alignment between positive education and NFE’s values and goals. Because NFE frameworks are social, flexible, focused on play and exploration, and unrestricted by curriculum, they afford the application of positive education:

NFE is very suitable for the application of positive education. After all, these are the principles we believe in and deal with daily, these are the values at the very basis of everything we do – the way we work, the way we talk to children, and the way we play with them. (RBS, interview)

NFE is a more suitable framework [for positive education] than schools are because it is less restrictive and doesn’t have to follow any formal curriculum…Additionally, school vacations, during which children spend many hours in NFE frameworks, offer them an opportunity to learn and to practice positive education. (OB, interview)

The integration of positive education was perceived as an opportunity to advance NFE frameworks, turning them into agents of important and meaningful values and advancing their professional standing.

Challenges in integrating positive education into NFE frameworks

Participants noted specific challenges inherent to the nature of NFE, including the structure of the NFE programs, the students who participate in them, and the NFE teachers themselves. Structural challenges include competing time demands, as the need to allocate time for positive education conflicted with pre-existing time allocations for lunch, rest, homework, and enrichment activities such as art, sports, and computer skills. Participants noted difficulties in implementing the continual processes required for positive education, due to the wide age range of children joining NFE frameworks and inconsistent participation. Attendance challenges are inherent in NFE, which is less regulated and does not convey the same sense of importance as formal education.

Other challenges related to the physical and emotional states of children who often arrive physically and emotionally drained after a long day at school and are, therefore, unable to engage in deep learning. Challenges related to NFE teachers include the limited professional training currently available. More notably, feelings of being overworked, underappreciated, and burnt out interfere with being emotionally available:

…It’s hard to become engaged in meaningful and demanding training programs when we are not appreciated, taken for granted and often seen as a babysitter (AL, interview).

Ways for integrating positive education into NFE frameworks

Despite the above challenges, participants’ commitment to positive education involved exploration of structured and unstructured ways to adapt and integrate what they learned during the training program and in the future as well as to integrate positive education in NFE systems more generally. Most participants note that structured and regular integration would provide a strong foundation for successful implementation. To overcome NFE time restrictions, most participants suggested regular and relatively short weekly sessions (approximately 45 min) focused on a variety of positive education topics. Topics most frequently mentioned were mindfulness, gratitude, strengths, and emotional self-awareness. Some participants suggested an additional focus on growth mindset, empathy, emotion management, and interpersonal communications. To overcome children’s after-school fatigue, sessions would be conducted playfully and enjoyably.

Participants suggested the use of tools they had already practiced and were able to retain and those included in their workplans. Examples include identifying personal strengths in self and others; sharing gratitude, emotions, and stories of coping; discussing social dilemmas that correspond to positive psychology elements; engaging in mindfulness practice and nature walks; using games, art, and music; and linking positive psychology themes to holidays and changing seasons. To adapt positive education learning processes to groups of children of different ages, participants explored ways to create a long-term and continuous positive education process that starts at a young age and continues through higher grades.

Alongside the formal integration, participants argued that positive education should be infused into daily NFE routines holistically and informally and that a shared positive education language should be created. Informal integration was experimented with during and after the training and included holding students’ group discussions of emotional and social dilemmas, praising strengths and efforts during sports activities, and involvement in community projects:

When it came to ball games, we taught children to praise their friends for their efforts, and we encouraged them to talk about their feelings in different situations. We also wrote, together with the children, gratitude letters to community members who do things for the community and the recipients were very moved and shared these letters on the community's WhatsApp group. (TO, interview)

Noting the importance of holistic integration, some participants suggested that future training programs should include teams instead of single representatives, to facilitate the sharing of targeted topics, training materials, and building positive education programs. A few participants suggested involving parents by sharing relevant elements of positive education programs or by focusing on students’ strengths during parent-teacher interactions.

Discussion

This study employed a qualitative multi-method design to explore the experiences of NFE teachers during and following their participation in a novel positive education training program grounded in the SEARCH framework. The findings underscore the relevance and potential benefits of implementing positive education within NFE contexts, with reported positive impacts extending to teachers, their students, and the broader educational frameworks in which they operate. At the same time, the effective integration of positive education practices within NFE settings necessitates careful attention to several structural and contextual challenges—most notably, the distinctive characteristics of NFE environments and the often-precarious professional status of NFE educators.

Positive education has emerged as an important strand of positive psychology (Seligman and Adler, 2018; White and Kern, 2018), owing to increasing challenges to the wellbeing of students worldwide (Shorey et al., 2022). However, positive education has been very limitedly integrated into NFE despite being an important second-tier education system (Gruner, 2017) and the clear potential of NFE frameworks to provide a suitable arena and an opportunity for expanding positive education efforts. Furthermore, despite the key role of teachers in social–emotional development (Schonert-Reichl, 2017), positive education training programs for teachers, especially in NFE, are scarce.

The findings indicate that NFE teachers perceive positive education as both essential for children and youth in contemporary society and as a suitable—even inherently aligned—component of non-formal education. These perspectives were reflected not only in their expressed attitudes, but also in their participation, sustained engagement, and full retention throughout the training program. Furthermore, their proactive efforts to apply positive education practices within their educational settings during the course of the training, as well as their utilization of the training materials to foster resilience during a time of crisis—including their request for an additional session—further underscore the perceived relevance and practical value of the program.

The prominence of personal development as a key theme in the current study supports and extends existing research on positive education training programs within formal education contexts (Yeh and Barrington, 2023). This finding also aligns with results from the large-scale MYRIAD project, which reported that school-based mindfulness training did not yield significantly greater improvements in adolescents’ mental health and wellbeing compared to standard teaching practices (Kuyken et al., 2022a). However, the same intervention was found to reduce teacher burnout and improve overall school climate (Kuyken et al., 2022b), suggesting that investing in teacher-focused training may represent a more effective and sustainable approach to enhancing educational wellbeing.

Strategies to enhance and maintain wellbeing support teachers’ ability to cope with challenges, demands, and pressures (Zinsser et al., 2016) and lead to improved retention (Grant et al., 2019). For example, self-efficacy and self-confidence help teachers accomplish goals and tasks, welcome challenging activities, develop a high sense of commitment, overcome failures quickly, and promote positive attitudes in students (Day et al., 2007; Hussain et al., 2022). The current study demonstrates that putting the wellbeing of NFE teachers at the center of a positive education training program provided a major incentive for teachers to participate, had a positive and intertwined impact on personal and professional wellbeing, allowed teachers to ‘walk the talk’ and provided strategies to integrate positive education into their respective NFE frameworks.

Enhancement of teachers’ wellbeing during the training took place through several mechanisms, including the ability to explore and manage a wide range of emotions, including negative emotions and proactively promote positive emotions, self-compassion, vulnerability, self-care, and self-confidence. Emotional self-awareness, which integrates the negative and positive aspects of human experiences and their complex interactions to optimize positive outcomes in line with positive psychology 2.0 (Ivtzan et al., 2015; Wong, 2010) enhanced teachers’ ability to identify and understand their own and others’ emotions and regulate negative emotions, and advance positive emotions in themselves and others. Various studies had demonstrated that emotional self-awareness is crucial to teachers (Yeh and Barrington, 2023), allowing them to regulate their emotions in the classroom (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009), motivate themselves when facing challenges (Stein and Book, 2000), understand others, express empathy, and form positive interactions (Brackett et al., 2009). Additionally, while resilience, a key goal of positive education, has not been explicitly targeted by the current program, several elements which had been previously identified as resilience factors were addressed, such as locus of control and self-efficacy) Ali et al., 2023; Etherton et al., 2022), strengths (Goodman et al., 2017) and positive emotions) Cohn et al., 2009). Indeed, some participants testified that they had employed such mechanisms during and following the training, particularly in times of crisis.

Most participants referred to engagement with work and positive interactions with students as being associated with enhanced personal and professional wellbeing. This finding extends research in formal education, where positive psychology interventions improved teacher-student interactions, teacher-parent communications, overall job satisfaction, work engagement, and teaching performance (Chodkiewicz and Boyle, 2017; Dreer, 2020; Hwang et al., 2017).

The interpersonal relational wellbeing outcome of the study supports the importance of expanding the positive education framework beyond the individual to encompass the social domain (White, 2017; Jones and Deutsch, 2011). This is particularly pertinent in the context of NFE, which is inherently grounded in social aims and community involvement (Callanan et al., 2011). The initiation of both community-based projects and the provision of positive education trainings to the community following the training found in the current study, highlight the potential for broader social impact resulting from the current training intervention.

More generally, the findings align with the five dimensions of Seligman’s (2011) conceptualization of teachers’ wellbeing: feeling good about their work and experiencing positive emotions within it, being engaged in their work, having meaningful relationships with students and colleagues, finding meaning in their work and experiencing a sense of achievement and success.

Although most participants had not implemented aspects of positive education prior to the study, the majority made efforts to integrate positive education into their corresponding NFE frameworks and viewed NFE as suitable for such integration. These efforts demonstrate that positive education training can be highly motivating for NFE teachers and equip them with needed resources to bring positive education into NFE frameworks. Participants’ active and voluntary involvement in positive education could be attributed to their newly gained ability to ‘walk the talk’ and explore positive education personally before introducing it to their students. Participants’ use of newly gained knowledge to design activities demonstrates confidence and flexibility in implementation. Evidence of teachers’ ability to experiment with strategies, even during training, and to flexibly adjust positive education practices to their needs, indicated that transfer of learning (Kotnour, 2011) had taken place.

A holistic approach focused on a variety of positive psychology elements allowed the program to meet teachers’ needs and provided them with tools to address a wide range of students’ needs. As noted, these elements were largely in line with the SEARCH pathways of wellbeing (Waters and Loton, 2019) and interactions between these pathways, in alignment with the Synergistic Change Model (Rusk et al., 2018), which suggests that interventions are most effective when designed to create inter-connections along pathways. For example, the development of a habit of gratitude toward others supported both the habits and goals pathway and the relationships pathway. Finally, flexibility in the training program, and providing a variety of strategies and activities (Jones et al., 2017) resonated with the unstructured and flexible nature of NFE and was noted to contribute to the program’s success.

At the same time, the role of burnout in shaping teachers’ receptiveness to positive education training warrants careful consideration. It was exemplified by two participants who, having experienced severe fatigue, stress, and burnout prior to commencing the program, reported difficulty in deriving professional meaning from the training. Their experiences suggest that positive education initiatives should be introduced relatively early in teachers’ careers, accompanied by ongoing support for their wellbeing. This is particularly critical in the context of non-formal education (NFE), where educators often contend with high workloads, chronic stress, limited professional recognition, and scarce resources—all of which can undermine both wellbeing and engagement with professional development.

Prior research has highlighted the impact of the low professional status associated with feminized educational occupations on teachers’ professional identity (Moloney, 2010), the detrimental effects of sustained stress on burnout, and the protective role of social–emotional resources in mitigating these outcomes (Gavín Chocano et al., 2022). This is particularly significant, as chronic stress and negative emotional experiences can lead to teacher demotivation, decreased job satisfaction, and reduced self-efficacy, which in turn negatively impact attitudes toward students (Sandilos et al., 2018). Consequently, it is imperative to provide sustained support for NFE teachers’ wellbeing and social–emotional competence, alongside organizational and societal solutions aimed at addressing the structural challenges they face.

Implementation difficulties experienced by some participants further suggest that future training programs should consider ways to adjust programs for different teacher groups, and that such adjustments should be an integral element of the training. Noted implementation challenges inherent to NFE systems suggest several implications for future training programs. First, the future design of positive education tools and training programs for NFE should consider its specific characteristics (e.g., less structured but more flexible learning practices and irregular attendance) and should include ways to overcome corresponding challenges. Second, as suggested by White and Kern (2018), NFE teachers need to be aware of these inherent challenges and understand them fully. Lastly, current efforts to enhance wellbeing are often provided within a whole-school framework (e.g., Coulombe et al., 2020; Shoshani and Steinmetz, 2014). NFE frameworks involve groups and systems that work in relative isolation. Accordingly, creating systemic processes and communities of practice to implement positive education in NFE systems should be considered. Such a long- term view of positive education may also help overcome the noted difficulty in introducing positive education to adolescents for the first time.

Limitations

The current study was qualitative in nature and thus limited to a small sample of teachers, all employed in similar NFE frameworks in a peripheral and rural area in northern Israel. As participation in the study was voluntary, participant teachers might have joined it due to a prior inclination toward positive education. The participant population was all female, in line with their representation in the profession, As this might not be the case in all other countries, mixed gender groups can be examined. Furthermore, although multiple tools were used to capture participants’ perceptions, all data were gathered from a single cohort and were thus limited to a single source.

Future studies could use pre-post quantitative measures to capture changes in participants’ wellbeing, views, and practices, which could include teachers from different areas in the country or other countries. Non-voluntary participation (e.g., via continuing professional development) could eliminate potential biases. Finally, the study of training programs of different lengths or with a focus on other aspects of positive education could provide important information about how to best design positive education training programs for NFE teachers.

Conclusion

The current study examined a unique positive education training program for NFE teachers, combining theory and practice to address teachers’ and students’ wellbeing. The program produced a change in the wellbeing of participant NFE teachers and provided them with tools to cultivate wellbeing in their students. The findings further suggest that integrating positive education into NFE systems in enjoyable and playful ways and as part of existing daily routines could significantly widen the current penetration of positive education programs. In doing so, positive education training programs could contribute to the wellbeing of students and teachers, creating a positive continuum with formal education. Advancing the standing of and participation in NFE could contribute to the wellbeing of our children and youth. It is therefore recommended that policymakers should prioritize the inclusion of positive education as part of NFE teacher training and incorporate the enhancement of wellbeing as a professional standard.

There is a clear need to further develop and systematically design training programs and tools tailored to the specific characteristics and diverse contexts of NFE, which spans a wide range of age groups and settings. Such efforts would facilitate broader and more sustained exposure to positive education—across educational spheres (formal schooling and NFE environments), temporal dimensions (morning and afternoon programming), and modalities (formal and informal instruction, individual and social).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by ETHICS/28/2022- Kinneret Academic College Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ND: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, A. (2016). Teaching life skills increases well-being and academic performance : evidence from Bhutan, Mexico, and Peru. (Doctoral dissertation). Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania. Available online at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1572 (Accessed July 20, 2025).

Ainly, J., and Carstens, R. (2018). Teaching and learning international survey (TALIS) 2018 conceptual framework. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Ali, S. A. O., Alenezi, A., Kamel, F., and Mostafa, M. H. (2023). Health locus of control, resilience and self-efficacy among elderly patients with psychiatric disorders. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 33, 616–623. doi: 10.1111/inm.13263

Allison, P., and Seaman, J. (2017). Experiential education. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encycl. Educ. Philos. Theory, Singapore: Springer. 1–6. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-588-4_108

Almida, F., and Morais, J. (2025). Non-formal education as a response to social problems in developing countries. E-Learn. Digital Media 22, 122–138. doi: 10.1177/20427530241231843

Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., Zangeneh, M., and Ak, İ. (2022). Benefits of positive psychology-based story reading on adolescent mental health and well-being. Child Indic. Res. 15, 781–793. doi: 10.1007/s12187-021-09891-4

Bartko, W. T., and Eccles, J. S. (2003). Adolescent participation in structured and unstructured activities: a person-oriented analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 32, 233–241. doi: 10.1023/A:1023056425648

Brackett, M. A., Patti, J., Stern, R., Rivers, S. E., Elbertson, N. A., Chisholm, C., et al. (2009). A sustainable, skill-based approach to building emotionally literate schools. In M. Hughes, H.L. Thompson and J.B. Terrell (eds.), Handbook for developing emotional and social intelligence: Best practices, case studies, and strategies, San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer. 329–358.

Cabanas, E., and Illouz, E. (2019). “Hijacking the language of functionality? In praise of ‘negative’ emotions against happiness” in Critical happiness studies. eds. N. Hill, S. Brinkmann, and A. Petersen (London, England: Routledge).

Callanan, M., Cervantes, C., and Loomis, M. (2011). Informal learning. WIRE’s. Cogn. Sci. 2, 646–655. doi: 10.1002/wcs.143

Campion, J., and Rocco, S. (2009). Minding the mind: the effects and potential of a school-based meditation programme for mental health promotion. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2, 47–55. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2009.9715697

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., et al. (2021). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 16, 749–769. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

Cefai, C., and Cavioni, V. (2015). Mental health promotion in school: An integrated, school-based, whole school. In: B. Kirkcaldy (ed). Promoting Psychological Well-Being in Children and Families, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 52–67. doi: 10.1057/9781137479969

Chodkiewicz, A. R., and Boyle, C. (2017). Positive psychology school-based interventions: a reflection on current success and future directions. Rev. Educ. 5, 60–86. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3080

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., and Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion 9, 361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0015952

Compton, W. C., and Hoffman, E. (2019). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and flourishing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Coulombe, S., Hardy, K., and Goldfarb, R. (2020). Promoting wellbeing through positive education: a critical review and proposed social ecological approach. Theory Res. Educ. 18, 295–321. doi: 10.1177/1477878520988432

Council of Europe. (2024) Non-formal learning/education. Available online at: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/non-formal-learning (Accessed May 2, 2025).

Cronin, A., Alexander, V. D., Fielding, J., Moran-Ellis, J., and Thomas, H. (2008). The analytic integration of qualitative data sources. In: P. Alasuutari, L. Bickman & J. Brannen (eds). The SAGE handbook of social research methods. (Los Angeles: Sage.) 572–584. doi: 10.4135/9781446212165

Day, C., Sammons, P., and Stobart, G. (2007). Teachers matter: Connecting Lives, Work and Effectiveness. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Denston, A., Martin, R., Fickel, L., and O'Toole, V. (2022). Teachers’ perspectives of social-emotional learning: informing the development of a linguistically and culturally responsive framework for social-emotional wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Teach. Teach. Educ. 117:103813. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103813

Dolev, N, and Itzkovich, Y. (2020). In the ai era soft skills are the new hard skills. In: W. Amann and A. Stachowicz-Stanusch (Eds). Artificial intelligence and its impact on business, Phoenix, AZ, InTechOpen. 55.

Donaldson, S. I., and Donaldson, S. I. (2020). The positive functioning at work scale: psychometric assessment, validation, and measurement invariance. J. Well-Being Assess. 4, 181–215. doi: 10.1007/s41543-020-00033-1

Dreer, B. (2020). Positive psychological interventions for teachers: a randomised placebo-controlled field experiment investigating the effects of workplace-related positive activities. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 5, 77–97. doi: 10.1007/s41042-020-00027-7

Dror, Y. (2002). The history of kibbutz education: From practice to theory. Bnei Brak, Israel: Kibbutz HaMeuchad Publishing (in Hebrew).

Etherton, K., Steele-Johnson, D., Salvano, K., and Kovacs, N. (2022). Resilience effects on student performance and well-being: the role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. J. Gen. Psychol. 149, 279–298. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2020.1835800

Feng, X., Lu, X., Li, Z., Zhang, M., Li, J., and Zhang, D. (2020). Investigating the physiological correlates of daily well-being: a PERMA model-based study. Open Psychol. J. 13, 169–180. doi: 10.2174/1874350102013010169

Fernández-Ríos, L., and Vilariño, M. (2016). Myths of positive psychology: deceptive manoeuvres and pseudoscience. Psychology Papers 37, 134–142.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In: Advances in experimental social psychology, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press. vol. 47, 1–53. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., and Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: an experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. J. Sch. Psychol. 46, 213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., and Ruch, W. (2016). Positive psychology interventions addressing pleasure, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment increase well-being and ameliorate depressive symptoms: a randomized, placebo-controlled online study. Front. Psychol. 7:686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00686

Gavín Chocano, Ó., Rodríguez Fernández, S., and García Martínez, I. (2022). Relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout in non-formal teachers of people with disabilities. Rev. Complut. Educ. 33, 623–634. doi: 10.5209/rced.76370

González-Pérez, L. I., and Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2022). Components of education 4.0 in 21st century skills frameworks: systematic review. Sustain. For. 14:1493. doi: 10.3390/su14031493

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., and Machell, K. A. (2017). Personality strengths as resilience: a one-year multiwave study. J. Pers. 85, 423–434. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12250

Grajcevci, A., and Shala, A. (2016). Formal and non-formal education in the new era. Act. Res. Educ. 7, 119–130.

Grant, A. A., Jeon, L., and Buettner, C. K. (2019). Relating early childhood teachers’ working conditions and well-being to their turnover intentions. Educ. Psychol. 39, 294–312. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1543856

Green, S., Leach, C., and Falecki, D. (2021). “Approaches to positive education” in The Palgrave handbook of positive education. In M. L. Kern and M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds). (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 21–48.

Gross, Z., and Goldratt, M. (2017) The impact of nonformal education on its participants. A literature review submitted to the Israeli chief scientist of the Ministry of Education. Available online at: https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/noar/informal_education1.pdf (Accessed July 20, 2025).

Gruner, H. (2017) Non-formal code: Updating its characteristics and building a research tool to evaluate the strength of each characteristic. PhD thesis, Bar-Ilan University.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., and Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: an update. J. Couns. Psychol. 52:196. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

Hoppers, W. (2006). Non-formal education and basic education reform: A conceptual review. Paris, France: International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP), UNESCO.

Hussain, M. S., Khan, S. A., and Bidar, M. C. (2022). Self-efficacy of teachers: a review of the literature. Multi-Disciplinary Research Journal 10, 110–116.

Hwang, Y. S., Bartlett, B., Greben, M., and Hand, K. (2017). A systematic review of mindfulness interventions for in-service teachers: a tool to enhance teacher wellbeing and performance. Teach. Teach. Educ. 64, 26–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.015

Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., and Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Johnson, M., and Majewska, D.. (2022). Formal, non-formal, and informal learning: what are they, and how can we research them?. Research Report. Cambridge University Press & Assessment.

Jones, J. N., and Deutsch, N. L. (2011). Relational strategies in after-school settings: how staff–youth relationships support positive development. Youth Soc. 43, 1381–1406. doi: 10.1177/0044118X10386077

Jones, S., Bailey, R., Brush, K., and Kahn, J.. (2017). Kernels of practice for SEL: Low-cost, low-burden strategies. The Wallace Foundation.

Kahane, R. (1997). The origins of postmodern youth: Informal youth movements in a comparative perspective, vol. 4. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter.

Kern, M. L., and Wehmeyer, M. L. (2021). The Palgrave handbook of positive education. The Hague: Springer Nature, –777. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3

Kotnour, T. (2011). An emerging theory of enterprise transformations. J. Enterp. Transform. 1, 48–70. doi: 10.1080/19488289.2010.550669

Kuyken, W., Ball, S., Crane, C., Ganguli, P., Jones, B., Montero-Marin, J., et al. (2022a). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: the MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Mental Health 25, 99–109. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300396

Kuyken, W., Ball, S., Crane, C., Ganguli, P., Jones, B., Montero-Marin, J., et al. (2022b). Effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision on teacher mental health and school climate: results of the MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Mental Health 25, 125–134. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2022-300424

La Belle, T. J. (1982). Formal, nonformal and informal education: a holistic perspective on lifelong learning. Int. Rev. Educ. 28, 159–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00598444

Lavy, S. (2020). A review of character strengths interventions in twenty-first-century schools: their importance and how they can be fostered. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 15, 573–596. doi: 10.1007/s11482-018-9700-6

Liu, B., Guan, Y., Jing, H., Hofmann, S. G., and Liu, X. (2022). Mindfulness and PERMA well-being: intervention effects and mechanism of change. Psychology 13, 675–704. doi: 10.4236/psych.2022.135046

Lomas, T., and Ivtzan, I. (2016). Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive–negative dialectics of wellbeing. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 1753–1768.

Ma, L., Mazidi, M., Li, K., Li, Y., Chen, S., Kirwan, R., et al. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 293, 78–89.

Marques, S. C., Lopez, S. J., and Pais-Ribeiro, J. L. (2011). “Building hope for the future”: a program to foster strengths in middle-school students. J. Happiness Stud. 12, 139–152. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9180-3

McClelland, M. M., Tominey, S. L., Schmitt, S. A., and Duncan, R. (2017). SEL interventions in early childhood. Futur. Child. 27, 33–47. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0002

McLellan, R., Faucher, C., and Simovska, V. (2022). Wellbeing and schooling: Cross cultural and cross disciplinary perspectives. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

McNeven, S., Main, K., and McKay, L. (2024). Wellbeing and school improvement: a scoping review. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 23, 588–606. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2023.2183512

Meyers, M. C., van Woerkom, M., and Bakker, A. B. (2013). The added value of the positive: a literature review of positive psychology interventions in organizations. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 22, 618–632. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.694689

Moloney, M. (2010). Professional identity in early childhood care and education: perspectives of pre-school and infant teachers. Ir. Educ. Stud. 29, 167–187. doi: 10.1080/03323311003779068

Noble, T., and McGrath, H. (2016). “The Prosper framework for student wellbeing” in The PROSPER school pathways for student wellbeing: Policy and practices. H. Noble and McGrath (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 25–95.

Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O'Connor, M., and Robinson, J. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. Int. J. Wellbeing 3, 147–161. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v3i2.2

Oades, L., and Mossman, L. (2017). “The science of wellbeing and positive psychology” in Wellbeing, recovery and mental health. M. Slade, L. Oades, and A. Jarden eds. (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press), 7–23.

OECD (2018) Education 2030: The future of education and skills- the future we want. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2018/06/the-future-of-education-and-skills_5424dd26/54ac7020-en.pdf (Accessed July 20, 2025).

Osher, D., Kidron, Y., Brackett, M., Dymnicki, A., Jones, S., and Weissberg, R. P. (2016). Advancing the science and practice of social and emotional learning: looking back and moving forward. Rev. Res. Educ. 40, 644–681. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16673595

Palomera, R., Fernández-Berrocal, P., and Brackett, M. A. (2008) Emotional intelligence as a basic competency in pre-service teacher training: Some evidence. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 6, 437–454.

Paterson, A., and Grantham, R. (2016). How to make teachers happy: an exploration of teacher wellbeing in the primary school context. Educ. Child Psychol. 33, 90–104. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2016.33.2.90

Pauwels, B. G. (2015). “The uneasy—and necessary—role of the negative in positive psychology” in Positive psychology in practice. ed. S. Joseph (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley), 807–822. doi: 10.1002/9781118996874.ch46

Platt, I. A., Kannangara, C., Tytherleigh, M., and Carson, J. (2020). The hummingbird project: a positive psychology intervention for secondary school students. Front. Psychol. 11:2012. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02012

Reichel, N. (2009). Nonformal education- what does it mean? Mofet 37, 5–8. (in Hebrew). Available at: https://education.biu.ac.il/sites/education/files/shared/%D7%94%D7%97%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%9A%20%D7%94%D7%91%D7%9C%D7%AA%D7%99%20%D7%A4%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%9E%D7%9C%D7%99%20%D7%91%D7%99%D7%9F%20%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%95%D7%93%20%D7%9C%D7%90%D7%A8%D7%A2%D7%99%D7%95%D7%AA%20%D7%9E%D7%95%D7%91%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%AA%20%D7%A2%D7%9E’%2018-21.pdf

Roeser, R. W., Galla, B., and Baelen, R. N. (2022) Mindfulness in schools: Evidence on the impacts of school-based mindfulness programs on student outcomes in P–12 educational settings. Edna Bennet Pierce Prevention Research Center, the Pennsylvania State University. Available at: https://prevention.psu.edu/sel/issue-briefs/mindfulness-in-schools-evidence-on-the-impacts-of-school-based-mindfulness-programs-on-student-outcomes-in-p-12-educational-settings/ (Accessed 30 April, 2025).

Romi, S., and Schmida, M. (2009). Non-formal education: a major educational force in the postmodern era. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 257–273. doi: 10.1080/03057640902904472

Rusk, R. D., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., and Waters, L. (2018). A complex dynamic systems approach to lasting positive change: the synergistic change model. J. Posit. Psychol. 13, 406–418. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2017.1291853

Rusk, R. D., and Waters, L. E. (2013). Tracing the size, reach, impact, and breadth of positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 8, 207–221. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.777766

Ryff, C. (2022). Positive psychology: looking back and looking forward. Front. Psychol. 13:840062. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.840062

Ryu, J., Walls, J., and Seashore Louis, K. (2022). Caring leadership: the role of principals in producing caring school cultures. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 21, 585–602. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2020.1811877

Sachs, J., Adler, A., Bin Bishr, A., de Neve, J-E., Durand, M., Diener, E., et al. (2019) Global Happiness and Wellbeing Policy Report 2019. Available online at: http://www.happinesscouncil.org (Accessed May 5, 2025).